Abstract

Seedling-stage weeds are one of the key factors affecting the crop growth and yield formation of soybean. Accurate detection and density mapping of these weeds are crucial for achieving precise weed management in agricultural fields. To overcome the limitations of traditional large-scale uniform herbicide application, this study proposes an improved YOLOv11n-based method for weed detection and spatial distribution mapping by integrating low-altitude UAV imagery with field elevation data. The second convolution in the C3K2 module was replaced with Wavelet Convolution (WTConv) to reduce complexity. A SENetv2-based C2PSA module was introduced to enhance feature representation and context fusion with minimal parameter increase. Soft-NMS-SIoU replaced traditional NMS, improving detection accuracy and robustness for dense overlaps. The improved YOLOv11n algorithm achieved a 3.4% increase in mAP@50% on the test set, outperforming the original YOLOv11n in FPS, while FLOPs and parameter count increased by only 1.2% and 0.2%, respectively. More importantly, the model reliably detected small grass weeds with morphology highly similar to soybean seedlings, which were undetectable by the original model, thus meeting agricultural production monitoring requirements. In addition, the pixel-level weed detection results from the model were converted into coordinates and interpolated using Kriging in ArcGIS (10.8.1) Pro to generate continuous weed density maps, resulting in high-resolution spatial distribution maps directly applicable to variable-rate spraying equipment. The proposed approach greatly improves both the precision and operational efficiency of weed detection and management across large agricultural fields, providing scientific support for intelligent variable-rate spraying using plant protection UAVs and ground-based sprayers, thereby promoting sustainable agriculture.

1. Introduction

Soybean serves as one of the most essential crops worldwide, providing both food and oil resources, and its yield and quality are strongly influenced by field weeds. During the seedling stage, weeds strongly compete with cultivated plants for sunlight, water, and nutrients, often impeding plant growth, causing developmental disorders, and significantly reducing yield [1]. Traditional manual weeding is labor-intensive, inefficient, and costly, whereas uniform large-scale herbicide application not only increases chemical usage but also accelerates the development of weed resistance and poses potential risks to soil and ecological systems [2,3]. In this context, precision variable-rate spraying has emerged as a promising approach, enabling targeted herbicide application based on spatial weed distribution, optimizing chemical use, and promoting both crop productivity and environmental sustainability [4].

The core of precision variable-rate spraying lies in the rapid and accurate identification and spatial localization of seedling-stage weeds [5,6]. Soybean seedling weeds are small and morphologically similar to crops, making early large-scale identification particularly challenging. Recent advances in low-altitude unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) remote sensing offer an effective solution for large-field monitoring, providing high-resolution imaging, flexible maneuverability, broad coverage, and real-time data acquisition [7,8]. When integrated with machine learning and deep learning algorithms, UAV-based approaches enable automatic weed recognition and precise localization, significantly reducing labor and time costs and laying the technical foundation for early-stage monitoring and variable-rate pesticide application.

Traditional machine learning methods, which rely on handcrafted features such as color, shape, and texture, often struggle under varying lighting conditions and complex backgrounds, especially when distinguishing morphologically similar crop seedlings from weeds [9,10]. In contrast, deep learning methods automatically extract features end-to-end and have shown outstanding capability in detecting small targets, complex background scenarios, as well as real-time processing. Existing object detection frameworks include two-stage detectors (e.g., the R-CNN series) [11,12,13] and single-stage detectors (e.g., SSD and YOLO series) [14,15,16]. Among these, the YOLO series, owing to its compact architecture, has been extensively utilized for detecting agricultural targets due to its high speed and relatively high accuracy. However, detecting soybean seedling weeds remains challenging for YOLO models [17,18], due to small target size, background interference, and the trade-off between accuracy and inference speed [19]. Consequently, model enhancement and feature optimization have become key research priorities for UAV-based weed detection [20,21].

Previous studies have achieved promising results in small-scale image recognition. Luo et al. [22] utilized UAV-based remote sensing technology to achieve real-time detection and spatial distribution mapping of three different weed species, providing theoretical and practical support for variable-rate spraying strategies and long-term agricultural sustainability. Sheng et al. [23] combined low-altitude UAV imagery of rice fields with three machine learning algorithms to generate weed distribution maps, while Wang et al. [24] applied K-means clustering to identify Poaceae and broadleaf weeds in soybean seedling UAV images, achieving an average recognition accuracy of 99.5%. Huang and Zhang [25] utilized fully convolutional networks (FCNs) for pixel-level classification and prescription map generation. Although these methods improved automation in weed detection, their capacity for modeling and visualizing weed spatial distribution across large fields remains limited. Integrating UAV remote sensing, enhanced deep learning models, and GIS spatial analysis provides a promising solution, enabling high-precision weed identification and the generation of continuous, high-resolution spatial distribution maps to support precision variable-rate spraying [26,27].

In this study, we propose an integrated approach that combines low-altitude UAV imagery, an improved YOLOv11n model, and GIS spatial analysis in order to attain highly accurate identification, localization, and spatial distribution modeling of soybean seedling weeds. This work offers the following key contributions:

- (1)

- Construction of a soybean seedling weed dataset under real field conditions.

- (2)

- Development of an improved YOLOv11n model (WTConv + SENetV2 + Soft-NMS-SIoU), striking a balance between the accuracy of detection and computational efficiency. With superior performance for small Poaceae weeds.

- (3)

- Using UAV positioning information and GIS spatial modeling technology to create a continuous weed density distribution map, which will provide high-resolution prescription maps and decision-making support for variable spraying.

The proposed approach lays a technical foundation for intelligent, effective large-area weed control and support for sustainable agricultural development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Indicators

2.1.1. Test Site and Dataset Construction

The experiment was conducted at Jianshan Farm, Jiŭsān Administration Bureau, Nenjiang City, Heihe, Heilongjiang Province, China, with geographic coordinates ranging from 125°19′53″ E to 125°47′15″ E longitude and 48°46′55″ N to 49°1′18″ N latitude. This area is characterized by a cold-temperate continental monsoon climate. Located in the third accumulated temperature zone of Heilongjiang, and represents a typical dryland crop production area in China. The experimental field employed a “ridge-three-row” planting pattern, in which three rows of soybean were evenly planted on each 1.1 m-wide ridge to increase planting density and seedling survival. Key agronomic practices, including deep soil loosening, precision sowing, and side-deep fertilization, were applied to enhance yield.

The experimental field, located on the west side of the airfield at Jianshan Farm, covered a total area of 81.82 mu (approximately 5.45 ha) with a plot size of 425 m × 145 m. The experimental period spanned from 30 May to 7 June 2025. The remote sensing imagery data in this study were collected using the DII MAVIC™ 3M drone, manufactured by SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd. in Shenzhen, China. The drone is equipped with an RTK module and, by connecting to a RTK network service, achieves real-time positioning accuracy at the centimeter level during flight, providing precise geographic reference for the imagery data. During the flight mission, the drone was equipped with a high-resolution RGB camera and maintained a vertical orientation relative to the ground throughout the flight. At a relative flight altitude of 12 m, the ground sampling distance of the obtained imagery was approximately 1.2 cm. The key flight parameters are as follows: flight altitude of 12 m, with the system defining a speed range for each altitude. The speed for all altitudes should be set to the maximum value within the adjustable flight speed range (flight speed does not affect image quality in the experiment). The heading overlap is 80%, and the side overlap is 70%. The imaging mode involved vertical photography at equal time intervals to obtain orthophotos that cover the entire test area and maintain high spatial consistency.

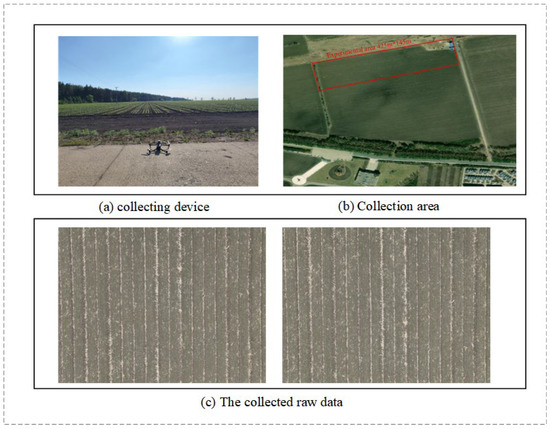

By following pre-planned autonomous flight paths, the UAV was capable of acquiring large-scale field images while recording GPS coordinates for each image to provide geographic references for subsequent weed spatial localization. Using a UAV fitted with a high-resolution RGB camera, a total of 4250 images were captured in JPG format at a resolution of 5280 × 3956 pixels. Figure 1 illustrates the UAV image acquisition process and several sample images from the dataset. Image collection was conducted under natural lighting conditions, with a preference for front lighting to ensure weed visibility.

Figure 1.

Dataset collection.

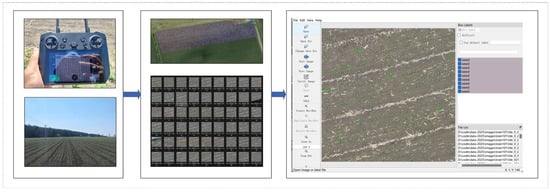

The collected UAV images were first uploaded to the DJI Agriculture Smart Platform for image stitching, generating orthophotos of the entire experimental field. Subsequently, the synthesized images were partitioned using a GDAL-based image tiling algorithm, with tile dimensions set to 1024 × 1024 pixels and an overlap of 10%. During the tiling process, fully black tiles were automatically filtered and pixel values were normalized. A CSV file containing georeferenced metadata for each tile was also generated. The digital images acquired by the UAV are susceptible to illumination variations and changes in flight attitude, resulting in inconsistent image quality. Therefore, images obtained through the sliding-window approach were screened to remove blurry frames and those without weed targets. A total of 2000 representative images were selected for this study. These images were used to construct a weed image dataset for the soybean seedling stage.

The tiled images were annotated using the LabelImg software (version 1.8.1), and annotation data were saved in XML format. To ensure that each rectangular annotation contained only a single target object, a field-based, real-world seedling-stage weed image dataset was constructed with minimal background interference. To guarantee temporal coverage and diversity, the dataset includes soybean seedling stages VE, VC, V1, and V2, addressing the identification needs of weeds at different growth stages. Finally, to construct the dataset, an 8:1:1 split was applied for the training, validation, and test sets, as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Image Tiling and Annotation.

2.1.2. Experimental Setup

The experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 5060-Ti GPU (16 GB VRAM). The detailed software environment and model training hyperparameters are summarized in Table 1. Our hyperparameter selection was guided by the following considerations: the input image size (imgsz) was set to 1024 × 1024 to preserve sufficient detail for accurate target recognition. Given the GPU’s VRAM capacity, a batch size of 8 was chosen to balance training efficiency and stability. Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) was employed as the optimizer, and the model was trained for 300 epochs to ensure adequate convergence of the loss function. The number of data loading workers was set to 6 to optimize data throughput between the CPU and GPU during training.

Table 1.

Experimental Hardware Configuration.

2.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

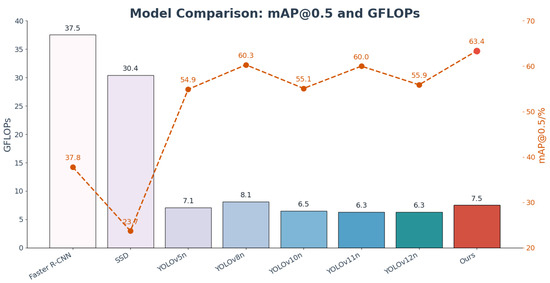

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed method in soybean seedling-stage weed detection, we conducted comparative experiments with a range of classical and state-of-the-art object detection algorithms, including the classical methods Faster R-CNN and SSD, as well as representative models from the YOLO series: YOLOv5, YOLOv8, YOLOv10, YOLOv11, and YOLOv12. To objectively compare and select the optimal model, a comprehensive set of evaluation metrics was employed, covering detection accuracy, model complexity, and inference efficiency. The primary metrics include mean Average Precision (mAP), encompassing mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95, as well as Precision (P) and Recall (R). Additionally, model parameters (Params), floating-point operations (GFLOPs), and frames per second (FPS) were used to assess the model’s lightweight characteristics, computational complexity, and inference speed.

Specifically, mAP@50 indicates the average precision calculated at an IoU threshold of 0.5, whereas mAP@50:95 reflects the mean precision computed over multiple IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step size of 0.05. A higher mAP indicates superior overall detection accuracy of the model. The number of parameters (Params) reflects the compactness of the model, while GFLOPs indicate computational complexity; a lower GFLOPs value implies reduced computational demand during inference. FPS measures the number of frames the model can process per second, where a higher value signifies faster inference speed.

Equations (1)–(3) formally define these evaluation metrics. The mAP is the mean AP across all categories and serves as a measure of overall detection performance. Precision is defined as the ratio of correctly classified positive instances to all predicted positive instances, reflecting the model’s accuracy. Recall quantifies the proportion of actual positive instances correctly identified, thereby measuring the model’s effectiveness in capturing all positive samples within the dataset.

Equation (1) presents the mathematical expression of mean average precision (mAP), which represents the average precision across all categories. Here, N denotes the total number of categories involved in the object detection task, APi represents the average precision of the i-th category, and mAP@0.5 refers to the mean average precision when the IoU threshold is set to 0.5.

Equation (2) defines the mathematical expression of precision, which quantifies the ratio of correctly identified positive samples to the total number of samples predicted as positive. In this context, TP (true positive) indicates the count of accurately detected positive instances, while FP (false positive) corresponds to the number of negative instances mistakenly classified as positive.

Equation (3) defines the mathematical expression of recall, where TP represents the proportion of actual positive samples correctly predicted as positive by the model. FN (false negative) represents the count of positive samples erroneously classified as negative.

2.1.4. Spatial Interpolation of Weeds Based on the Kriging Method

This study employs ordinary kriging to interpolate discrete weed point data, generating a continuous surface of weed density distribution [28]. Kriging is a geostatistical method grounded in the theory of regionalized variables and spatial autocorrelation, providing the best linear unbiased estimation for unsampled locations. The workflow begins with the construction of an experimental semivariogram based on the coordinates and counts of observed weed centers, which quantifies how spatial dependence changes with distance [29]. Theoretical models, such as the spherical, exponential, or Gaussian models, are then selected to fit the experimental semivariogram. This fitting process determines three key parameters that characterize the spatial structure: the nugget (representing random variation), the sill (representing total spatial variation), and the range (representing the spatial extent of autocorrelation). Finally, using the fitted semivariogram model, the weed density in each grid cell is estimated via weighted averaging by solving the kriging system of equations [30]. A key advantage of this approach lies in its consideration of not only the distance between sample points and prediction locations but also the spatial structural characteristics to optimize weight allocation. As a result, the generated continuous surface exhibits greater reliability and smoother spatial transitions compared to methods such as inverse distance weighting (IDW) [31].

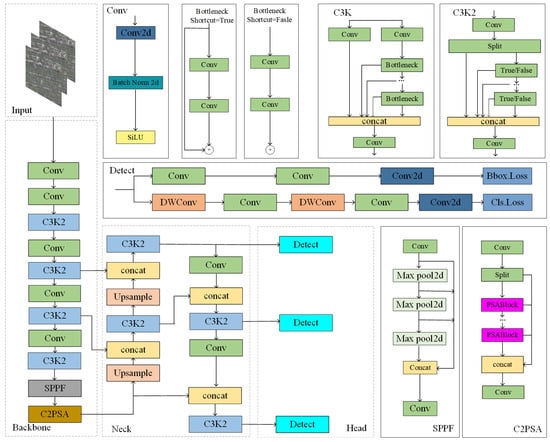

2.2. YOLOv11 Model

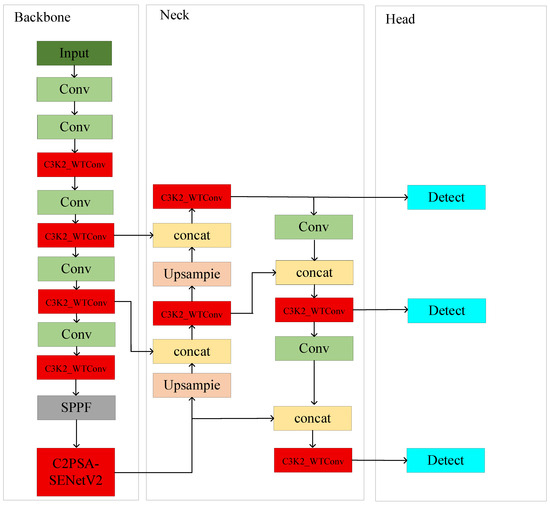

YOLOv11, released by the Ultralytics team in 2024, features the network architecture illustrated in Figure 3. The model incorporates several architectural optimizations to enhance feature extraction capabilities and computational efficiency. Specifically, the model’s C2f component was replaced with the C3k2 module to enhance performance. This significantly improves adaptability and expressive power. Following the SPPF module, A novel C2PSA module is introduced, which integrates an upgraded C2f architecture with the PSA attention mechanism. Thereby strengthening the extraction of key features.

Figure 3.

Structure Diagram of YOLOv11.

The C2PSA module is designed with two essential components. The first is a multi-head attention mechanism, which simultaneously processes multi-dimensional input features. The second component is a feedforward neural network (FFN) designed to project features into a higher-dimensional space, enabling the capture of more complex nonlinear relationships. This architecture enhances feature representation while also facilitating gradient propagation through the use of optional residual connections. Thereby accelerating network convergence.

In addition, YOLOv11 incorporates depthwise separable convolutions in the detection head, thereby greatly reducing computational demands without compromising detection performance. Overall, these improvements allow YOLOv11 to achieve superior performance in small-object detection and complex scenarios, while preserving high inference efficiency.

2.3. Improved YOLOv11 Model

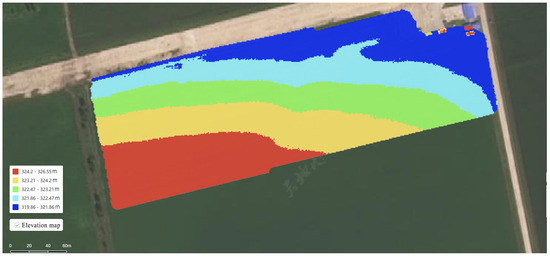

2.3.1. Analysis of Elevation Map of Research Area

As shown in Figure 4, the elevation map of the study area indicates a terrain variation ranging from 319.86 to 326.55 m. Although the overall topographic relief is minor, the map clearly reveals localized micro-topographic undulations within the field. Such subtle terrain variations may still influence target texture features, illumination conditions, and spatial positioning in high-resolution remote sensing images, thereby affecting the detection accuracy of the YOLO model. In particular, when targets are small or the background is complex, even slight terrain fluctuations may result in boundary shifts or missed detections. Therefore, during model improvement, it is essential to incorporate terrain variation features revealed by elevation data. Elevation maps can assist in distinguishing between terrain-induced shadows and weed targets, thereby reducing false detections and enhancing the network’s ability to generalize across heterogeneous environmental conditions. Moreover, elevation data can also serve as indicators of environmental conditions, such as soil moisture content and drainage efficiency. This helps capture weed growth patterns and spatial distribution. This provides critical spatial references for precision spraying and intelligent field management, ultimately improving the accuracy and robustness of weed recognition.

Figure 4.

Elevation map of the research area.

For UAV-acquired images, the challenges of dispersed target distribution, large variations in object size, indistinct feature representation, and terrain fluctuations often lead to missed detections and false positives, making YOLOv11n less effective under these conditions. However, the adoption of larger architectures would considerably increase both computational load and parameter overhead. Therefore, to balance detection performance with computational efficiency, several improvements were introduced to the YOLOv11n model. To address the constraints of the original YOLOv11n model when applied to large-scale weed monitoring—such as excessive parameter counts, high architectural complexity), sensitivity to terrain undulations, and suboptimal accuracy for multi-scale object recognition—the high-resolution study proposes an innovative lightweight weed detection model. The structure of the enhanced model is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Improved YOLOv11 structure diagram.

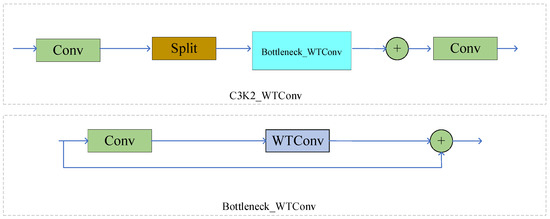

2.3.2. C3K2_WTConv Module

In the YOLOv11 model, the C3K2 module serves as a critical feature extraction unit. Its core idea is to divide the input features into two parts: one part is directly propagated through conventional convolution, while the other is processed by multiple C3K or Bottleneck structures for deep feature extraction. The two outputs are then concatenated to achieve feature fusion [32]. The C3K module leverages variable convolution kernels (e.g., 3 × 3, 5 × 5) and channel separation strategies to enlarge the receptive field and enhance the representation of multi-scale objects. However, while this design improves detection accuracy, it also substantially increases computational complexity and the number of hyperparameters, thereby limiting lightweight deployment and real-time performance [33].

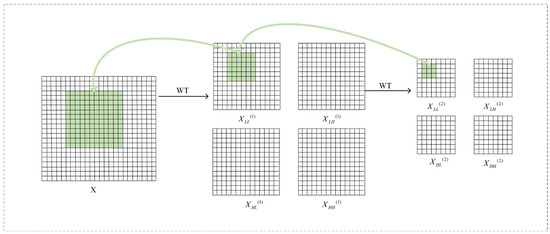

To overcome these limitations, this study incorporates wavelet convolution (WTConv) into the C3K2 module, as illustrated in Figure 6, and proposes the C3K2_WTConv module. As shown in Figure 7, WTConv operates by applying a wavelet transform to decompose the input features into distinct low- and high-frequency sub-bands: global structural information is maintained in the low-frequency component, whereas the high-frequency component accentuates fine local details. Subsequently, small-kernel depthwise convolutions are applied to each frequency sub-band to capture multi-scale contextual information. The architecture increases the receptive field of the model efficiently without introducing a significant rise in parameter count from larger kernels. With relatively low computational cost, by incorporating the C3K2_WTConv module, the model’s ability to extract features is substantially strengthened, with notable improvements in detecting small weeds in challenging field scenarios [34,35,36,37].

Figure 6.

Wavelet Convolution Principle Diagram. Notes: Performing convolution in the wavelet domain results in a larger receptive field. In this example, a 3 × 3 convolution is performed on the low-frequency band of the second-level wavelet domain XLL(2), resulting in a 9-parameter convolution that responds to lower frequencies of a 12 × 12 receptive field in the input X.

Figure 7.

Network structure diagram of C3K2_WTConv.

For a given image X, when applying a first-level Haar wavelet transform along a single spatial axis, either width or height, the following steps are required: first, use the kernel functions [1, 1]/√2 and [1, −1]/√2 for depth convolution operations. Subsequently, the standard down-sampling is executed, halving the data resolution. To achieve a two-dimensional Haar wavelet transform, these operations need to be performed separately in the two spatial dimensions, specifically by using the four sets of filters in Equation (1) for the depthwise convolution, a stride of two is employed:

In this set of filters, serves as the low-pass filter, while , and together form the high-pass filter group. For each input channel, the outputs obtained after convolution are as follows:

The resulting output comprises four distinct channels, with each channel exhibiting spatial dimensions that are half those of the input image . Specifically, the channel corresponds to the low-frequency content of the image , while , , and are associated with the high-frequency elements in the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal directions.

Because the filter kernels in Equation (4) constitute an orthogonal set, it becomes feasible to perform the inverse wavelet transform (IWT) by employing transposed convolution operations, which effectively reconstruct the original signal from its wavelet coefficients.

The cascade wavelet decomposition process is carried out by recursively decomposing the low-frequency component layer by layer. The decomposition result at each level can be expressed as:

Here, = , where denotes the current decomposition level and represents the wavelet transform operation. In this manner, the low-frequency component exhibits an enhanced ability to distinguish finer frequency details, while its spatial resolution is correspondingly reduced.

The C3K2_WTConv framework, enhanced with wavelet convolution, significantly improves multi-scale feature extraction compared to the conventional C3K2 module [38]. It more accurately captures object details across scales, reducing the loss of small-object features and enhancing their detectability in complex field backgrounds. Experimental results confirm that integrating WTConv increased recall from 83.0% to 84.0% and mAP@0.5 from 60.0% to 60.4%. The module also better captures low-frequency information, compensating for standard convolution’s limitations in global feature extraction. While FLOPs rose from 6.3 GB to 7.5 GB and parameters from 2.6 M to 2.8 M, the inference speed remains practical at 56.7 FPS, ensuring real-time processing of UAV imagery [39,40,41]. This provides a stronger foundation for high-precision weed identification and spatial distribution modeling, supporting intelligent spraying and precision agriculture [42].

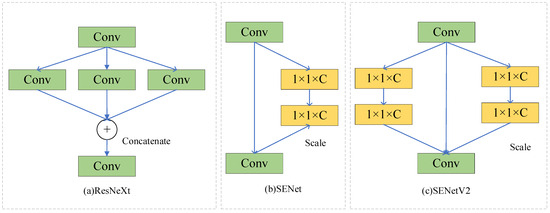

2.3.3. SENetV2 Structure

UAV-based monitoring of soybean seedling weeds occurs in complex environments, where image acquisition is frequently affected by variations in illumination, leaf occlusion, overlapping weeds, and field elevation differences. These dynamic environmental conditions can significantly disrupt target texture features, illumination patterns, and spatial positioning, thereby reducing the overall performance of detection models. To enhance model robustness under such complex conditions, attention mechanisms are widely employed in feature extraction tasks, designed to allow the network to concentrate on essential features while minimizing the impact of background noise. In comparison with widely adopted attention modules, including Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) and Efficient Channel Attention (ECA), SENetV2 (N, 20223)exhibits superior capabilities in channel modeling and global information capture. Building upon the traditional squeeze-and-excitation framework, this module incorporates the SaE (Squeeze Aggregated Excitation) mechanism, employing multi-branch fully connected layers, which improves the network’s capacity for global feature modeling. Significantly improving feature expression with minimal additional parameters [43].

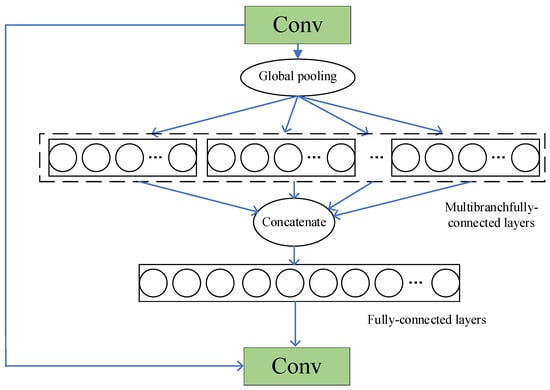

As illustrated in Figure 8, the ResNeXt module employs multi-branch convolutions to enhance feature diversity; in contrast, SENet calculates the weights for each channel using global average pooling and subsequent fully connected layers. SENetV2 combines the advantages of ResNeXt and SENet, introducing a multi-branch aggregation structure within the residual block to implement the squeeze-and-excitation mechanism. Thereby improving feature refinement and global information integration. Based on this, a C2PSA-SENetV2 module was designed in the backbone network, aiming to increase the model’s resilience under complex field conditions while strengthening its ability to distinguish soybean seedling weeds.

Figure 8.

ResNeXt, SENet, SENetv2 modules.

Figure 9 illustrates the internal mechanism of the SaE module proposed in SENetV2. Initially, the input undergoes a squeeze operation, producing condensed representations that are subsequently processed through multi-branch fully connected layers. These outputs then pass through the excitation stage, after which the segmented data are recombined to restore their original structure. This design enables the network to capture a richer and more diverse set of features from the input, while simultaneously modeling inter-channel dependencies during feature transformation, thereby enhancing the overall representational capacity of the network.

Figure 9.

SaE module.

Serving as a key framework for examining the effects of network depth, the residual module utilizes shortcut connections to skip certain layers, whose outputs are later combined with the corresponding shortcuts. In the basic version of the residual module, the input is represented as “”, which is used to modify the input operations, employing batch normalization alongside dropout to enhance network performance, represented by . The mathematical formulation corresponding to the residual module is provided in Equation (8).

In the aggregated residual module, the input is concatenated directly without alteration, facilitated by the implementation of branch convolutions. The corresponding mathematical expression is given in Equation (9).

The resulting output is then resized to restore its original dimensions. The squeeze-and-excitation (SE) mechanism within the residual module is mathematically expressed in Equation (10):

Here, the function “” represents the squeeze step, which comprises a fully connected (FC) layer incorporating a reduction ratio (r). Following the squeeze operation, after performing the “” operation, the execution of the same “” operation indicates the Excitation process. This procedure is designed to reconstruct the channel-modified input back to its original dimensions without reducing its size. This final output is scaled like that used in SENet.

Subsequently, the FC layer’s output is combined multiplicatively with the module input, thereby reinstating the original dimensionality. Equation (11) provides a formal representation of the operation sequence in the residual module.

SENetV2 builds upon the original SENet architecture by introducing the SaE (Squeeze aggregated Excitation) module, further enhancing the modeling efficiency of inter-channel relationships and global feature representation [44]. While retaining the benefits of global channel attention, SENetV2 more effectively suppresses complex background interference and emphasizes key target features, thereby demonstrating greater robustness under dynamic conditions such as illumination changes, leaf occlusion, and overlapping weeds. Compared with conventional attention mechanisms, its optimized structure significantly improves feature extraction capability with only a marginal increase in parameters [45], providing a more precise and reliable solution for soybean seedling weed detection under UAV remote sensing conditions, while also offering substantial research value and practical application potential [46].

2.3.4. Soft-NMS-SIoU Loss Function

In object detection tasks, the loss function is utilized to quantify the difference between the predicted outputs and the corresponding ground truth annotations [47]. Since its inception, the Intersection over Union (IoU) metric has become the predominant standard for assessing the accuracy of bounding box predictions. Over time, IoU-based regression losses have undergone continuous development, giving rise to variants such as GIoU, DIoU, CIoU, and EIoU. In the original YOLOv11 framework, CIoU is adopted as the bounding box regression loss, which is formally defined in Equation (12):

Here, measures the aspect ratio, acts as a weight for regulating the aspect ratio term, and denotes the Euclidean distance separating the centers of the predicted and true bounding boxes. CIoU introduces a penalty term based on the center point distance to IoU, refining bounding box localization by measuring the straight-line distance between the centers of predicted and actual boxes, thereby improving detection accuracy. However, in small object detection, the center distance penalty may be amplified, potentially negatively affecting the optimization process. In small object detection scenarios, CIoU may cause the model to focus excessively on the center points while neglecting optimization of the overlapping regions. Traditional CIoU loss functions mainly improve detection accuracy by optimizing the IoU, center distance, and aspect ratio of bounding boxes. However, for small weed targets with few effective pixels and blurred edges, CIoU struggles to fully capture their geometric properties, resulting in reduced localization accuracy.

To overcome this limitation, the present study adopts SIoU as the bounding box regression loss in the enhanced YOLOv11n model, replacing the original CIoU. SIoU considers the angle formed between the line linking the centers of the bounding boxes and the horizontal or vertical axes, which improves the alignment and shape consistency of the predicted boxes and enhances both the stability and precision of the regression process.

The SIoU function comprises four separate terms: distance loss, shape loss, angle loss, and IoU loss. First, to accelerate bounding box alignment, SIoU introduces an angle loss term, denoted by , representing the angular deviation of the line joining the centers of the two boxes from the horizontal or vertical reference:

where

Here, represents the position coordinates of the center of the predicted bounding box, and represents the position coordinates of the center of the ground truth bounding box. The distances from the center points to the box edges are used to calculate the distance loss, which is formulated in Equation (15):

Here, represents the normalized value of the center point distance, defined as:

SIoU further evaluates the variation in aspect ratios of the predicted versus ground truth boxes, resulting in the shape loss, which is calculated as:

Here, denotes the normalized width difference, and denotes the normalized height difference. The overall SIoU loss is formulated as:

The SIoU loss function integrates four critical dimensions—distance, angle, shape, and intersection-over-union (IoU)—enabling a more thorough optimization of both geometric structure and directional alignment. Specifically, SIoU enhances geometric constraints by jointly considering the distance, overlap area, aspect ratio, and overall shape distribution across the predicted and actual bounding boxes, thereby enabling a more complete characterization of object boundaries. In low-altitude UAV remote sensing scenarios, small targets are often of limited size and prone to being obscured by background clutter. SIoU improves bounding-box precision through refined edge distribution and shape-matching capabilities, effectively reducing both false negatives and false positives. In terms of distance optimization, SIoU introduces directional modeling of bounding boxes by incorporating orientation-aware mechanisms, thereby improving the capture of directional characteristics. In UAV low-altitude remote sensing, where variations in camera angle, target orientation, and terrain elevation are common, the Euclidean distance–based CIoU often neglects directional information, leading to rotational deviations in bounding boxes. By contrast, SIoU’s sensitivity to orientation enables predicted boxes to align more accurately with the true target orientation, enhancing detection reliability in directionally complex scenarios. These improvements are unified under a global optimization framework, allowing SIoU to both increase IoU metrics and substantially improve the precision of bounding box localization, regression convergence speed, and adaptability to object geometry and orientation. Consequently, SIoU demonstrates superior performance in complex scenarios and small-object detection tasks.

Furthermore, Soft-NMS was introduced to replace traditional NMS. In dense small-object detection scenarios, bounding boxes corresponding to different objects may overlap substantially. Conventional NMS directly discards boxes whose IoU with the highest-scoring box exceeds a predefined threshold, setting their scores to zero. This “hard suppression” may erroneously eliminate multiple overlapping detections, leading to missed targets. While adjusting the IoU threshold can partly mitigate this issue, selecting a universally optimal threshold for all small-object scenarios remains challenging: overly low thresholds risk false negatives, whereas overly high thresholds increase false positives.

Unlike traditional NMS, which discards overlapping boxes outright, Soft-NMS progressively modifies the scores of bounding boxes based on their overlap with the top-scoring box, instead of eliminating them. Boxes with higher overlap undergo stronger score decay, while those with smaller overlap are only slightly penalized. The score decay process is modeled using a Gaussian function, as defined in Equation (19):

Here, denotes the confidence score of the target bounding box, measures the extent to which the detected box coincides with the highest-confidence box, and is a parameter that controls the degree of score decay.

The core advantage of Soft-NMS in small-object detection lies in its “flexible” score decay mechanism, which provides a more rational approach to handling the high-overlap issues commonly observed in soybean seedling weed scenarios [48]. In contrast to the “hard suppression” of conventional NMS, Soft-NMS continuously adjusts the confidence scores of bounding boxes, effectively reducing missed detections under low overlap conditions and significantly mitigating false positives under high overlap conditions [49]. This leads to greater stability and robustness in dynamic field environments [50]. Furthermore, integrating Soft-NMS with SIoU achieves a “dual optimization,” in which precise geometric localization of bounding boxes and flexible post-processing work synergistically. While SIoU enhances localization accuracy through refined bounding box constraints, Soft-NMS improves discrimination in challenging scenarios with dense targets, leaf occlusion, and complex illumination [51]. Their combined effect substantially strengthens the detection performance of the improved YOLOv11n model for small weed targets in complex field environments, providing a more reliable technical foundation for precise weed recognition and spatial distribution modeling during the soybean seedling stage [52].

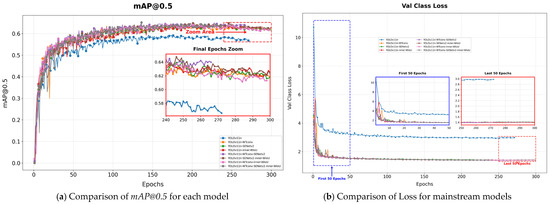

2.4. Method for Spatial Positioning of Weeds During the Seedling Stage

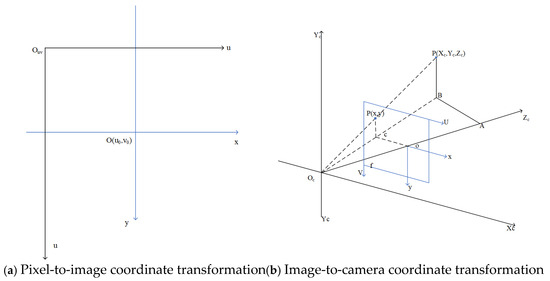

The ground target point and the imaging module are connected through imaging geometry. This constructed model primarily relies on the camera’s coordinate framework, and the association between the image plane and pixel locations is shown in Figure 10a, whereas the connections between the pixel, image, and camera coordinate systems are illustrated in Figure 10b. Ouv refers to the pixel-based coordinate framework, with its origin set at the image’s upper-left corner and coordinates expressed in pixels. Oxy denotes the image plane coordinates, setting the origin at the point where the optical axis meets the plane and using millimeters as the unit. OcXcYc denotes the camera coordinate system, where the origin is positioned at the camera’s optical center and coordinates are expressed in meters. Point P represents a location in the world coordinate system, and its corresponding image projection is denoted as p(x,y). Since the camera is rigidly mounted on the UAV, the UAV’s geographic coordinates can be directly regarded as those of the camera’s optical center, thus creating a spatial mapping between the world coordinate frame and the camera coordinate frame [53,54].

Figure 10.

Weed coordinate transformation.

The enhanced YOLOv1n model efficiently detects seedling-stage weeds in low-altitude UAV imagery and produces their pixel coordinates, which are subsequently converted into world coordinates via a coordinate transformation procedure [55]. The precise geographic coordinates of the weeds are determined using the UAV’s high-accuracy positioning system. The procedure for converting pixel coordinates into the world coordinate system is outlined as follows:

- (1)

- Mapping from Pixel → Image Coordinates: Points represented in the pixel coordinate system are first converted to the image coordinate system, as both share the same imaging plane. Typically, the geometric center of this plane—i.e., where the optical axis intersects the plane—serves as the origin for the image coordinate system. Unlike the pixel coordinate system, measured in pixels, the image coordinate system is expressed in millimeters.

- (2)

- Conversion: Image Coordinate System → Camera Coordinate System: As shown in Figure 10b, based on the principle of similar triangles, △ABOc is similar to △oCOc, and △pBOc is similar to △pCOc. This geometric similarity enables the derivation of proportional relations, facilitating the transformation of point P from the image coordinate frame to the camera coordinate frame.

- (3)

- Conversion: Camera Coordinate System → Global Coordinate System: During UAV image acquisition, the camera lens is oriented vertically downward. Therefore, the rotations around the Xw and Yw axes can be neglected, and only the rotation around the Zw axis is considered, as illustrated in Figure 10c,d.

Based on the aforementioned coordinate transformation process, the mapping between pixel coordinates and the image plane is formulated in Equation (20), where represents the physical size of each pixel along the x-direction of the image plane, and denotes the physical size of each pixel along the y-direction. The relationship between the image plane and the camera coordinate system is described in Equation (21), where f denotes the focal length of the UAV camera. represents the vertical distance between the UAV camera and the ground, corresponding to the flight altitude of the UAV. The relationship between the camera and the world coordinate system is defined in Equation (22), where R is the rotation matrix and T is the translation vector. Finally, the mapping from pixel positions to the world coordinate system is expressed in Equation (23).

In the above equations, and represent the pixel coordinates of the detected weeds in the image, while , and denote the positions of the weeds in the world coordinate system. Once the world coordinates of the weeds are determined, their corresponding geographic latitude and longitude can be computed using Equation (24).

Here, and indicate the geographic latitude and longitude of the weeds, respectively. and correspond to the UAV’s current latitude and longitude. The constant 0.000008983152 represents a one-meter variation in latitude.

2.5. Generation of Weed Spatial Distribution Maps

Spatial distribution maps of weeds provide an accurate depiction of weed abundance and density across different regions, offering a scientific foundation for precision variable-rate herbicide application [56]. In this study, a method is proposed to generate high-resolution weed spatial distribution maps by utilizing the operational area and the weeds’ geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude) [57,58], following the procedure outlined below:

- (1)

- Image Preprocessing and Field Reconstruction

Multiple UAV-acquired images were stitched and fused using the DJI Agricultural Smart Platform to generate high-resolution orthophotos of the field, providing foundational data for subsequent spatial analysis.

- (2)

- Consideration of Spraying Equipment Parameters

Different types of agricultural spraying equipment have varying operational widths. In this study, the ground sprayer used had a spraying width of 12 m, providing a reference for grid partitioning and spraying path planning.

- (3)

- Weed Identification and Spatial Localization

Utilizing the improved YOLOv11n network, weeds were accurately detected, and their geographic coordinates were obtained via UAV GPS data. The resulting weed points were incorporated into spatial grids, with the number of weeds in each grid cell calculated through ArcGIS Pro. This methodology allows for targeted herbicide selection and enables the rational deployment of multiple herbicides simultaneously, improving weed management effectiveness while lowering pesticide consumption.

- (4)

- Weed Classification and Visualization

Weed density within each rectangular grid was classified into six levels, and color coding was used to generate the weed spatial distribution map. The specific grading criteria are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Weed density classification criteria.

- (5)

- Grid Partitioning and Spraying Matching

A 6 m × 6 m rectangular grid was selected as the standard unit, corresponding to the optimal coverage width of the sprayer to ensure uniform and precise application [59,60]. Grid layout facilitates planning sprayer paths for full field coverage, optimizes spraying routes, improves operational efficiency, and reduces pesticide waste.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

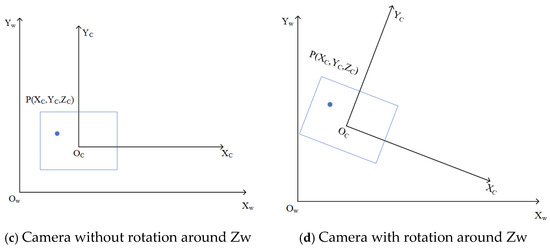

3.1. Ablation Study

To validate the effectiveness of each module, we conducted a systematic ablation study (results are shown in Table 3 and Figure 11). The experiments demonstrate that the WTConv module increased the recall rate from the baseline of 83.0% to 84.0%, but the increase in computational load led to a decrease in FPS. The SENetv2 module, focusing on improving feature quality, increased the mAP@0.5 by 1.3% with almost no impact on speed. Meanwhile, Soft-NMS-SIoU, by optimizing the post-processing stage, increased the mAP@0.5 by 1.1% without adding to the model complexity.

Table 3.

Comparison of Ablation Experiment Results.

Figure 11.

Comparison of mAP@0.5 and Loss for each model in the ablation test.

The module combinations demonstrated powerful synergistic effects. Notably, the combination of WTConv and Soft-NMS-SIoU significantly pushed the recall rate to 86.0%, reflecting the complementary nature of feature extraction and detection optimization. Ultimately, the complete model integrating all three modules achieved the best performance, with the recall rate and mAP@0.5 reaching 87.0% and 63.4%, respectively, representing a substantial improvement over the baseline. This fully confirms the effectiveness and complementarity of our proposed module combination in enhancing model performance, providing a solution that excels in both accuracy and efficiency for weed identification in complex scenarios.

3.2. Model Comparison Experiments

To comprehensively evaluate the proposed soybean seedling-stage weed detection method, we conducted a systematic comparison with mainstream algorithms such as Faster R-CNN, SSD, and the YOLO series, as shown in Figure 12 and Table 4. The experimental results revealed the characteristic differences of various architectures in agricultural scenarios: the traditional two-stage method, Faster R-CNN, is limited by its complex region proposal mechanism. Although its detection accuracy is reasonable (mAP@50 = 37.8%), the recall rate is significantly low (30.0%), and the inference speed is slow (30.19 FPS), indicating inherent limitations when dealing with dense, small-target weed scenes. SSD employs a single-stage detection paradigm, which shows a speed improvement (43.42 FPS); however, its shallow feature extraction capability leads to poor generalization performance in complex farmland backgrounds (mAP@50 = 23.7%). In contrast, the YOLO series achieves a better balance between speed and accuracy through multi-scale feature fusion and predefined anchor box mechanisms. YOLOv8 and YOLOv11, with optimized backbone networks and feature pyramid designs, achieved mAP@50 of 60.3% and 60.0%, respectively, while maintaining high inference efficiency (77.7 and 72.6 FPS), demonstrating the advantages of single-stage detectors in agricultural real-time vision tasks. This study builds upon the balanced architecture of YOLOv11 and innovatively introduces WTConv to enhance local feature extraction capabilities. It integrates SENetv2 for channel-wise adaptive calibration and adopts Soft-NMS-SIoU to optimize the processing of overlapping targets. As a result, it achieves a significant improvement in detection performance under complex backgrounds: the recall rate reaches 85.0%, mAP@50 improves to 63.4%, while maintaining a leading inference speed (80.4 FPS). This result not only validates the synergistic effect of the proposed modules in weed detection tasks but also demonstrates that targeted structural optimization can effectively enhance the model’s perception capabilities in complex agricultural scenarios while maintaining real-time performance, providing a more reliable technical solution for drone-based precision spraying.

Figure 12.

Comparison of mAP@0.5 and GFLOPs among mainstream models.

Table 4.

Algorithm comparison of test results.

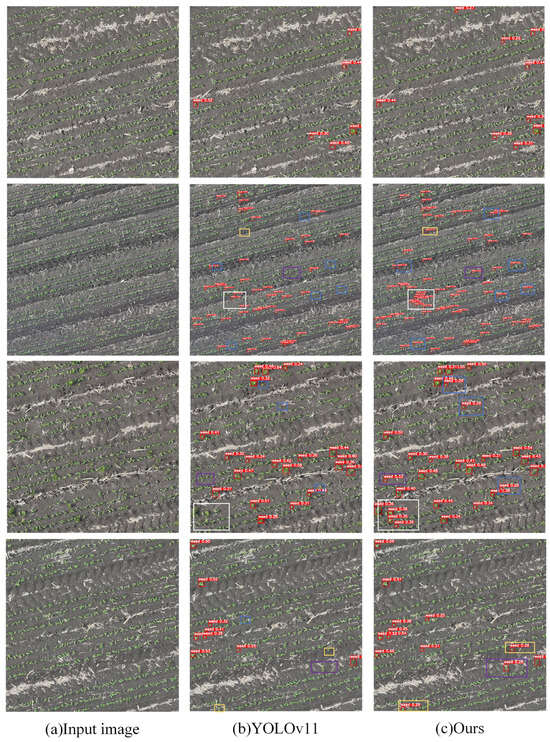

3.3. Detection Performance of the Improved YOLOv11n Model

To more intuitively evaluate the performance of the improved YOLOv11n algorithm, this study presents its detection results for soybean seedling-stage weeds through visualizations. As shown in Figure 13, the model can accurately detect and localize weeds under various complex conditions, including small weeds, overlapping weeds, densely distributed weed clusters, and seedlings morphologically similar to gramineous weeds. Notably, for broadleaf weeds, the bounding boxes achieve precise localization, avoiding overfitting or missed detections. Analysis of the visualized results indicates that the improved YOLOv11n exhibits high robustness when handling complex field scenarios, such as variations in lighting, background interference, and overlapping targets. Specifically, in the figure, blue bounding boxes denote small weed targets (e.g., isolated small individuals), white boxes indicate dense weed clusters (e.g., clustered weed areas), purple boxes mark overlapping weeds (e.g., overlapping or partially occluded targets), and gold boxes highlight seedlings morphologically similar to broadleaf weeds (e.g., objects with similar texture and color). These visualizations confirm the reliability and practicality of the improved YOLOv11n in real agricultural applications, providing effective technical support for precise weed management.

Figure 13.

Field Detection Results of the Improved YOLOv11n Model. Notes: The image employs a blue bounding box for small-target weeds, a white bounding box for dense weed communities, a purple bounding box for mutually occluded weeds, and a golden bounding box for morphologically similar seedling weeds.

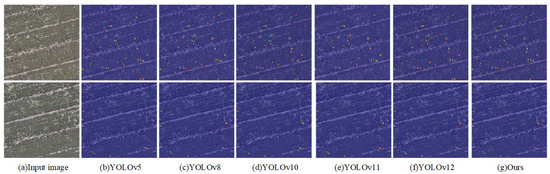

3.4. Feature Map Visualization Experiment

Feature heatmaps serve as an effective visualization tool, intuitively reflecting the model’s focus on target regions, where color intensity indicates different activation levels: red represents highly activated areas, blue represents weakly activated areas, and yellow and green indicate intermediate activation levels. When the target region is large and the proportion of red and yellow increases, it indicates higher model attention to that target. To further compare the feature extraction differences between the improved algorithm and the original algorithm, Grad-CAM visualization was applied to selected images from the test set using both the improved YOLOv11n model and its original version, as shown in Figure 14. In the figure, red areas represent high activation, while blue areas indicate weak activation. Comparative analysis shows that the original YOLOv11n model exhibits higher attention to non-target soybean seedlings, manifesting as prominent red activation regions. In contrast, the improved model significantly reduces attention to such non-target regions, concentrating activation (red and yellow areas) on inter-row weeds, demonstrating more effective capture of critical information in target weed regions. This enhancement improves detection accuracy and robustness, particularly highlighting the model’s superior ability to distinguish weeds from crops in complex field environments.

Figure 14.

Grad-Cam feature map analysis.

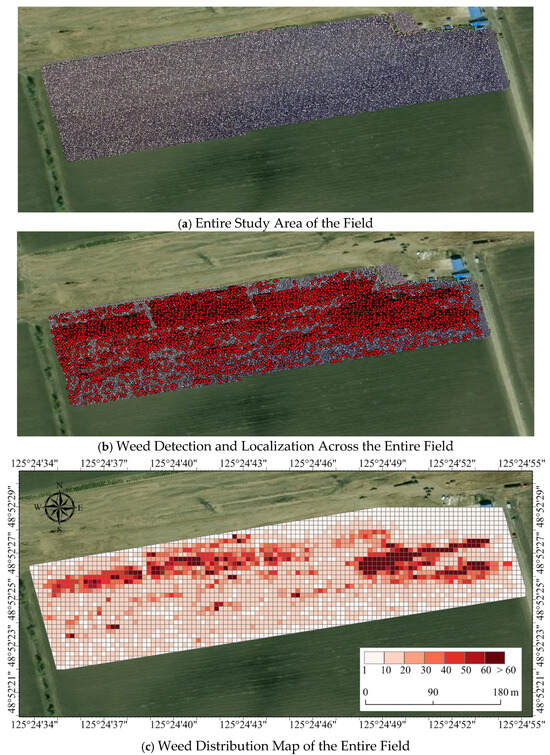

3.5. Generation of Seedling-Stage Weed Spatial Distribution Maps

When generating weed distribution maps, the field was divided into 6 m × 6 m grid units, with the number of weeds in each grid visualized using color intensity, where darker colors indicate higher weed density. The maps include geographic orientation and a scale bar to ensure spatial referencing accuracy. Although slight errors in weed latitude and longitude positioning may cause minor displacement of individual plants, at the grid scale, this deviation does not affect overall weed count statistics or herbicide application planning. Therefore, the resulting distribution maps fully meet agricultural application requirements. Figure 15 illustrates the process of generating the soybean seedling weed distribution map.

Figure 15.

Visualization Process of Soybean Seedling-Stage Weed Distribution Map.

In the spatial distribution modeling process, this study incorporated the Kriging interpolation method (the specific process is described in Section 2.1.4). The continuous weed density surface generated via Kriging interpolation can be further processed in a GIS platform using raster reclassification and threshold-based grading to categorize weed distribution into different levels. A final weed distribution map is then produced. By combining agricultural expert knowledge or economic threshold principles, each density level is mapped to the corresponding herbicide dosage, creating a variable-rate prescription map. This prescription map is typically output in raster or vector grid format and can seamlessly interface with intelligent spraying equipment to implement a “quantitative–spatial” differentiated control strategy. This process not only significantly reduces herbicide usage and environmental pollution but also improves control effectiveness, providing a scientific basis for the precise management of soybean seedling weeds.

4. Discussion

This study proposes a soybean seedling-stage weed detection method based on low-altitude UAV remote sensing imagery and an improved YOLOv11n model. While ensuring that the model is lightweight and maintains real-time performance, it significantly enhances the detection capability for small Poaceae weeds. Compared with the conventional YOLOv11n, the improved model incorporates WTConv convolution in the C3K2 module, effectively mitigating over-parameterization caused by receptive field expansion and enhancing multi-scale feature extraction. Our experimental results, which showed a rise in mAP@0.5 from 60.0% to 60.4% with the integration of WTConv, align with the findings of Zhou et al. [61], who demonstrated that incorporating multi-scale decomposition techniques can significantly improve the feature representation of small objects in complex backgrounds. Additionally, the C2PSA module based on SENetv2 further strengthens the model’s robustness under complex backgrounds and varying illumination conditions. This observation is consistent with recent studies on advanced attention mechanisms. For instance, Zhuang et al. [62] reported that channel-wise attention can suppress irrelevant background features, a finding that supports our model’s improved performance in distinguishing weeds from crop residues and soil noise. The introduction of Soft-NMS-SIoU demonstrates superior discrimination in overlapping object scenarios, significantly improving detection accuracy in dense regions. The effectiveness of this approach echoes the work of Sun et al. [63], which highlighted that softened suppression strategies and geometry-aware IoU metrics are crucial for mitigating missed detections in densely packed object populations. Experimental results indicate that the improved YOLOv11n outperforms the baseline model in key metrics such as mAP@0.5 and FPS, while only marginally increasing FLOPs and parameter count, demonstrating a favorable trade-off between accuracy and efficiency that is essential for practical agricultural applications.

Furthermore, this study integrates UAV high-precision positioning data with ArcGIS Pro spatial analysis capabilities, converting detection results into continuous weed density distribution maps, thereby establishing a complete technical chain from target recognition to spatial modeling. The Kriging-based spatial modeling method can accurately reflect the field-scale distribution patterns of weeds, providing a scientific basis for subsequent variable-rate herbicide application. This geostatistical approach for mapping biotic stressors is well-established in precision agriculture. Our methodology of generating prescription maps from UAV-derived detection data shares conceptual ground with the work of Li et al. [64], who successfully mapped weed pressures in cereal crops, though our study specifically tailors the workflow for soybean systems and integrates a more recent object detection architecture.

This “recognition–modeling–prescription map generation” methodological framework not only addresses the challenge of quantifying weed distribution patterns over large farmland areas, but also offers a novel approach for intelligent weed management in precision agriculture.

Nonetheless, several limitations remain in this study, which should be considered when interpreting the results and guiding future research. First, the study area is primarily concentrated in typical dry fields in Heilongjiang, and the model’s cross-regional transferability and adaptability require further validation. This is a common challenge in agricultural computer vision, as models trained on region-specific data often experience performance degradation when applied to new geographic locations with different soil types, weed species compositions, and planting practices [65]. Second, the dataset is primarily based on RGB images under natural lighting conditions, and its applicability under extreme lighting, strong wind, or shadow conditions needs further exploration. The performance sensitivity of RGB-based models to varying illumination and weather conditions is a known constraint. Previous research, such as Romero and Heenkenda [66], has suggested that incorporating multi-spectral data or employing robust data augmentation strategies can mitigate these effects, representing a valuable direction for our future work. Finally, although the generated weed density distribution maps provide references for variable-rate spraying, practical application still requires secondary optimization considering sprayer performance, economic thresholds, and other factors to ensure operational feasibility in production. This gap between algorithmic maps and operational reality is widely acknowledged. As noted by Munir et al. [67], the transition from a weed map to an effective prescription must account for dynamic factors like economic injury levels and sprayer hydraulic lag times to achieve true precision and cost-effectiveness. While comparisons of variable-rate prescription maps and weed area statistics would more directly demonstrate herbicide reduction potential, this study deliberately focused on the essential premise—precise weed detection and spatial mapping. The comparative assessment of prescription maps and their quantitative efficacy will be systematically undertaken following hardware integration in subsequent research.

5. Conclusions

This study proposes a method for soybean seedling-stage weed detection and distribution map generation, integrating low-altitude UAV remote sensing, an improved YOLOv11n model, and GIS spatial analysis. By incorporating WTConv and SENetv2 modules into YOLOv11n and combining the Soft-NMS-SIoU algorithm, the method significantly improves detection accuracy for small weeds and robustness under complex backgrounds, achieving a 3.4% increase in mAP@50 while maintaining high real-time performance. Using UAV imagery and GPS positioning data, weed detection results are spatially processed through the ArcGIS Pro platform, and continuous weed density surfaces are generated via Kriging interpolation to create prescription maps directly applicable to variable-rate spraying systems. This approach overcomes the limitation of previous studies that focused solely on object detection, establishing a complete chain from weed identification to spatial modeling and facilitating differentiated weeding operations with intelligent agricultural machinery over large fields. The study provides a feasible technical pathway for precise monitoring and intelligent management of soybean seedling-stage weeds in large fields, contributing to pesticide reduction, improved agricultural resource efficiency, and sustainable agricultural development. Future work will further explore the integration of multi-source remote sensing data, enhance the model’s cross-regional adaptability, and combine it with field validation of variable-rate spraying to promote practical application in agricultural production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and Methodology, Y.Y. and A.Z.; Software, Y.Y. and A.Z.; Validation, Y.Y.; Formal Analysis, Y.Y.; Investigation, Y.Y.; Resources, Y.Y.; Data Curation, Y.Y.; Writing-Raw Draft, Y.Y.; Writing—Review and Editing, A.Z.; Visualization, Y.Y.; Supervision, A.Z.; Funding Acquisition, A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University Research Initiation Programme for Scholars and Imported Talents [No. XYB202401].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Saini, P.; Nagesh, D.S. A review of deep learning applications in weed detection: UAV and robotic approaches for precision agriculture. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 168, 127652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedbol, É.; Lucotte, M.; Tremblay, G.; Moingt, M.; Paquet, S.; Brillon, J.B.; Brais, É.S. Weed management strategies effect on glyphosate-tolerant maize and soybean yields and quality. Agrosystems Geosci. Environ. 2020, 3, e20088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnkar, V.K.; Verma, N. Study of Critical Crop-Weed Competition Period on Quality Characters of Soybean. Trends Biosci. 2014, 7, 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.P.; Liang, C.Y.; Li, P.; Wang, P.Y.; Zou, L.W.; Zhang, R.D. Research Status and Prospects of Precision Fertilization Technology. Trop. Agric. Eng. 2022, 46, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Zheng, P.; Chen, F. Research on the Method of Generating Field Prescription Maps for Soybean Fields Based on ArcGIS Desktop. Soybean Sci. 2013, 32, 797–800. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M.; Hu, B. Research Status and Prospects of Algorithm for Generating Prescription Maps for Pesticide Spraying. China South. Agric. Mach. 2024, 55, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, C.; Li, W.; Lan, Y. Monitoring Cotton Defoliation Effects and Generating Prescription Maps Based on UAV Multispectral Remote Sensing. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2022, 45, 799–808. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Gu, S.; Mi, B. Innovative Application of Plant Protection UAVs in Rice Precision Cultivation and Efficient Pest Control. Agric. Dev. Equip. 2025, 10, 81–83. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.; Zhao, N.; Cheng, M. Research Progress and Prospects of Field Weed Recognition Based on Image Processing. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2020, 51, 323–334. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, R.; Yang, H.; Wu, J. Identification of Overlapping Leaves of Spinach and Weeds Based on Image Block Division and Reconstruction. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Han, Y.; Ai, H.; Dong, C.; Liu, H. Weed identification in soybean seedling stage based on UAV images and Faster R-CNN. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.D.; Liu, W.; Izere, P.; Singh, P.; Yu, C.; Riggan, B.; Zhang, K.; Jhala, A.J.; Knezevic, S.; Ge, Y.; et al. Towards real-time weed detection and segmentation with lightweight CNN models on edge devices. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Tan, Y. Advancements of UAV and Deep Learning Technologies for Weed Management in Farmland. Agronomy 2024, 14, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Luo, T.; Wei, D.; Long, T.; Wang, Z. Weed detection in sesame fields using a YOLO model with an enhanced attention mechanism and feature fusion. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 202, 107412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, F.; Chen, D.; Lu, Y.; Li, Z. YOLOWeeds: A novel benchmark of YOLO object detectors for multi-class weed detection in cotton production systems. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 205, 107655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Sun, T.; Chai, X.; Zhou, J. YOLO-WDNet: A lightweight and accurate model for weeds detection in cotton field. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 225, 109317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Cao, Y. Weed Detection Algorithms in Rice Fields Based on Improved YOLOv10n. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Li, H. FCB-YOLOv8s-Seg: A Malignant Weed Instance Segmentation Model for Targeted Spraying in Soybean Fields. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, B.B.; Hu, C.; Bagavathiannan, M.V. Evaluating Cross-Applicability of Weed Detection Models Across Different Crops in Similar Production Environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 837726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Yang, Y.; Subburaj, V.H. YOLOv7 for Weed Detection in Cotton Fields Using UAV Imagery. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Yi, J.; He, P.; Tie, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, W.; Long, L. Improvement of the YOLOv8 Model in the Optimization of the Weed Recognition Algorithm in Cotton Field. Plants 2024, 13, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Fu, D.; Mi, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Shi, Y.; Su, B. Real-time identification and spatial distribution mapping of weeds through unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) remote sensing. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 169, 127699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Jizhong, D.; Yali, Z.; Chang, Y.; Zhiwei, Y.; Yaqing, X. Research on the Distribution Map of Weeds in Rice Fields Based on Low-altitude Remote Sensing by Drones. J. South China Agric. Univ. 2020, 41, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; When, C. Soybean field weed identification based on lightweight sum-product network and UAV remote sensing images. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Deng, J.; Lan, Y.; Yang, A.; Deng, X.; Wen, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y. Accurate Weed Mapping and Prescription Map Generation Based on Fully Convolutional Networks Using UAV Imagery. Sensors 2018, 18, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gašparović, M.; Zrinjski, M.; Barković, Đ.; Radočaj, D. An automatic method for weed mapping in oat fields based on UAV imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 173, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee Sarvestani, G.; Edalat, M.; Shirzadifar, A.; Pourghasemi, H.R. Early season dominant weed mapping in maize field using unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) imagery: Towards developing prescription map. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 11, 100956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, P.; Zheng, Z.; Luo, W.; Cheng, B.; Wang, S.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, Z. RT-MWDT: A lightweight real-time transformer with edge-driven multiscale fusion for precisely detecting weeds in complex cornfield environments. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 239, 110923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiche, A.T.; Wittstruck, L.; Jarmer, T. Weed Detection from Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Imagery Using Deep Learning-A Comparison between High-End and Low-Cost Multispectral Sensors. Sensors 2024, 24, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, P.D.; Evstatiev, B.I.; Atanasov, A.Z.; Atanasov, A.I. Evaluation of Weed Infestations in Row Crops Using Aerial RGB Imaging and Deep Learning. Agriculture 2025, 15, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, F.L.; Nóbrega, H.; de Freitas, J.G.R.; Pinheiro de Carvalho, M.A.A. Assessment of Vegetation Indices Derived from UAV Imagery for Weed Detection in Vineyards. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhao, J.; Fan, Y. Research on CTSA-DeepLabV3+ Urban Green Space Classification Model Based on GF-2 Images. Sensors 2025, 25, 3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, M. SENetV2: Aggregated dense layer for channelwise and global representations. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.10807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhou, X.; Hu, S. Research on real-time obstacle detection algorithm for driverless electric locomotive in mines based on RSAE-YOLOv11n. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2025, 22, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Zheng, W.; Xu, Y. YOLO-SEA: An Enhanced Detection Framework for Multi-Scale Maritime Targets in Complex Sea States and Adverse Weather. Entropy 2025, 27, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, T.; Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Wang, H. YOLO-WAS: A Lightweight Apple Target Detection Method Based on Improved YOLO11. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Huang, J.; Duan, Q.; Li, Z. WT-HMFF: Wavelet Transform Convolution and Hierarchical Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Network for Detecting Infrared Small Targets. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Shen, X.; Zhang, H. A Dynamic Weights-Based Wavelet Attention Neural Network for Defect Detection. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 16211–16221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, C. DAFPN-YOLO: An Improved UAV-Based Object Detection Algorithm Based on YOLOv8s. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 83, 1929–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finder, L.; Wang, J.; Li, K. Wavelet Convolution for Multi-scale Feature Extraction in Image Recognition. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 45678–45689. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.J.H.; Li, Z. An Improved YOLO Model for Small Target Detection in Complex Environments Using Wavelet Transform. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2025, 20, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Taseer, A.; Han, X. Advancements in variable rate spraying for precise spray requirements in precision agriculture using Unmanned aerial spraying Systems: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 219, 108841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Li, Y.; Feng, H.; Wu, J.; Sun, W.; Ruan, Y. Research on a Trellis Grape Stem Recognition Method Based on YOLOv8n-GP. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mambile, C.; Leo, J.; Kaijage, S. Comparative analysis of CNN architectures for satellite-based forest fire detection: A mobile-friendly approach using Sentinel-2 imagery. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2025, 40, 101739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.-C.; Lee, S.-H.; Shen, Y.-C.; Yang, C.-S. Improved U-Net based on ResNet and SE-Net with dual attention mechanism for glottis semantic segmentation. Med. Eng. Phys. 2025, 136, 104298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi-Márquez, F.; Flores, G.; Valentín-Coronado, L.M. Leveraging deep semantic segmentation for assisted weed detection. J. Agric. Eng. 2025, 56, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, H. UAV Small Target Detection Algorithm Based on Cross-Scale Feature Fusion. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2025, 61, 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Yin, C.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Q.; Gu, Z. Research on Apple Recognition and Localization Method Based on Deep Learning. Agronomy 2025, 15, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Chen, H.; Xu, Z.; Ou, Z. Weed Detection Method Based on Lightweight and Contextual Information Fusion. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zhang, J.; Lei, A.; Wang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, C.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Xie, J. Enhancing detection accuracy of highly overlapping targets in agricultural imagery using IoA-SoftNMS algorithm across diverse image sizes. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Mostafa, K.; Yuan, G. Weed Identification in Maize Fields Based on Improved Swin-Unet. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Longchamps, L. Comparative performance of YOLOv8, YOLOv9, YOLOv10, YOLOv11 and Faster R-CNN models for detection of multiple weed species. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 9, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Su, W.-H.; Li, J.-L.; Peng, Y. Real-time lettuce-weed localization and weed severity classification based on lightweight YOLO convolutional neural networks for intelligent intra-row weed control. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 226, 109404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Research on Field Weed Recognition and Spatial Distribution of Rice Based on Deep Learning. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang Agricultural University, Shenyang, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R. Research on Weed Recognition and Positioning Based on Low-Altitude Remote Sensing. Master’s Thesis, Northwest Agriculture & Forestry University, Xianyang, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Pu, Y.; Qiu, X. Experimental Study on Optimization of Precision Spraying Prescription for Farmland Based on Dual-Path Control. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2024, 6, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mkhize, Y.; Madonsela, S.; Cho, M.; Nondlazi, B.; Main, R.; Ramoelo, A. Mapping weed infestation in maize fields using Sentinel-2 data. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2024, 134, 103571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, B.; Salcedo, R.; Garcia-Ruiz, F.; Gil, E. Field validation of a variable rate application sprayer equipped with ultrasonic sensors in apple tree plantations. Precis. Agric. 2025, 26, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q. Research on Target Recognition Method for Weeding Robots Based on Lightweight Network Models. Master’s Thesis, Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, Q. Development of a General Prescription Farming Embedded GIS Information Processing System. Agric. Equip. Technol. 2019, 45, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Hu, Y.; Huang, A.; Chen, Y.; Tong, X.; Liu, M.; Pan, Y. Lightweight SCC-YOLO for Winter Jujube Detection and 3D Localization with Cross-Platform Deployment Evaluation. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.; Wang, C.; Hao, H.; Song, W.; Guo, X. Maize Anthesis-Silking Interval Estimation via Image Detection under Field Rail-Based Phenotyping Platform. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Tian, P.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Niu, X.; Zhang, H.; Qian, Y. WT-CNN-BiLSTM: A Precise Rice Yield Prediction Method for Small-Scale Greenhouse Planting on the Yunnan Plateau. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Research on the Method for Generating Thermal Maps of Soybean Weeds Distribution in Fields Based on Drones. Master’s Thesis, Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University, Daqing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.; Anderson, J. Review on unmanned aerial vehicles, remote sensors, imagery processing, and their applications in agriculture. Agron. J. 2021, 113, 971–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, K.F.; Heenkenda, M.K. Developing Site-Specific Prescription Maps for Sugarcane Weed Control Using High-Spatial-Resolution Images and Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR). Land 2024, 13, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, A.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Anwar, S.; El-Maleh, A.; Khan, A.H.; Rehman, A. Impact of Adverse Weather and Image Distortions on Vision-Based UAV Detection: A Performance Evaluation of Deep Learning Models. Drones 2024, 8, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).