Abstract

The global food security faces significant threats from phytopathogenic microbes and weeds. In this study, seven secondary metabolites (1–7) were isolated from the insect-associated fungus Leptosphaeria sp. FZN28 in Mecopoda elongata. Their structures were elucidated through a combination of spectroscopic analyses. In bioactive assays, peniciphenalenin E (1) exhibited great antimicrobial activities against Phytophthora capsici and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, with EC50 values of 8.8 and 10.8 μg/mL, respectively. Scleroderolide (2) demonstrated EC50 values of 20.4 and 14.8 μg/mL against the same strains, respectively. Notably, as seen with in vitro assays, 100 μg/mL of 1 could effectively prevent infection of P. capsici with a protection efficacy of 69.1%, and compounds 1 and 2 at a concentration of 200 μg/mL could greatly inhibit disease development in S. sclerotiorum-infected cole leaves with inhibitory efficacies of 66.9% and 61.0%, respectively. Moreover, the two compounds could also affect the hyphal morphology of S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici via scanning electron microscope and transmission electron microscope. Additionally, compounds 1 and 2 at a concentration of 200 μg/mL could significantly inhibit the radicle growth and germ elongation of monocotyledon weed and dicotyledon weed, Echinochloa crusgalli and Eclipta prostrata. Considering their antimicrobial and herbicidal activities, compounds 1 and 2 showed promise for the development of new bio-pesticides.

1. Introduction

Microorganisms have the remarkable ability to produce secondary metabolites and small organic molecules, collectively known as natural products (NPs), and NPs serve as valuable reservoirs of potential bioactive compounds with applications in agriculture [1]. Recent reports indicate that approximately half of approved drugs are derived from NPs or their derivatives, highlighting their significance in pharmaceutical development [2]. Insect-associated fungi, microorganisms residing internally in the tissues of insects and microbes without causing negative effects [3], have gained recognition as crucial sources of natural products with diverse activities [4,5,6,7,8,9].

The Leptosphaeria species, a distributed fungal genus, are widely found in host plants and encompass both phytopathogenic and endophytic strains. Some Leptosphaeria species are known as phytopathogens causing diseases such as rape black shank [10,11,12]. However, other Leptosphaeria species function as endophytes, contributing to the production of an extensive array of secondary metabolites with antibacterial, antifungal, and plant growth-promoting activities [13,14]. Notable examples include sesquiterpenoid leptosphins B from the endophytic fungus Leptosphaeria sp. XL026, exhibiting antibacterial activity against Bacillus cereus [15], and leptosphaerin D, which demonstrated antifungal effects against plant pathogens Fusarium nivale (CGMCC 3.4600) and Piricularia oryzae (CGMCC 3.3283) with IC50 values of 12.5 and 18.1 μM, respectively [16].

Weeds and plant diseases pose significant threats to global agriculture, leading to substantial losses in crop yield [17]. Chemical control has been widely adopted for crop production to manage plant diseases and weeds, and the growing demand for sustainable agrochemicals with eco-friendly profiles has led to increased interest in secondary metabolites from microbes [18,19]. In our relentless pursuit of bioactive metabolites from endophytic and insect-associated fungi, seven secondary metabolites (1–7) were isolated from the insect-associated fungus Leptosphaeria sp. FZN28 in Mecopoda elongata. This report presents the isolation, structural elucidation of these compounds and reveals their antimicrobial and herbicidal activities in vitro and in vivo.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Experimental Procedures

High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectra (HR-ESI-MS) were collected on an Agilent 6210 TOF LC–MS spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). NMR spectra were obtained with a Bruker Avance-500 NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Rheinstetten, Germany) in CDCl3, DMSO-d6, or acetone-d6 at room temperature. Silica gel (200–300 mesh, Qingdao Marine Chemical Company, Pingdu, Qingdao, China) and Sephadex LH-20 (GE Biotech, San Diego, CA, USA) were used for column chromatography (CC). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed with a Shimadzu LC-20AT instrument with an SPD-20 A detector (Agilent, CA, USA) with an ODS column (ODS-2 HYPERSIL, 250 × 10 mm, 5 μm, Thermo Scientific, Shanghai, China).

2.2. Fungal Strains and Weed Seeds

Leptosphaeria sp. FZN28 was isolated from Mecopoda elongata collected in Zijin Mountain of Nanjing, China. General primers ITS1 and ITS4 were used for sequencing. A basic local alignment search tool (BLAST 2.16.0) (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 25 September 2024)) search of the partial sequence revealed that the closest sequence matched with 100% identity to Leptosphaeria sp. strains (accession number MT732008.1). Phytophthora capsici and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum were provided by the Lab of Natural Products and Pesticide Chemistry, Nanjing Agricultural University, China. The weed seeds of Echinochloa crusgalli and Eclipta prostrata were provided by the Lab of Herbicide Toxicology and Resistance, Nanjing Agricultural University, China.

2.3. Plant Materials and Growth

Nicotiana benthamiana was grown and maintained in growth rooms with an environmental temperature of 22–25 °C under a 16 h day/8 h night photoperiod. Brassica napus was grown under outdoor conditions with temperatures ranging from 10 °C to 25 °C.

2.4. Fermentation, Extraction, and Characterization of Secondary Metabolites

Leptosphaeria sp. FZN28 was cultured on PDA medium (200 g potatoes, 20 g glucose in 1 L of water) at 25 °C in the dark for 5 days. Mycelial agar plugs from the edge of the colony were transferred to 100 flasks each containing 400 mL of fermentation medium (PDB: 200 g potatoes, 20 g glucose, 1 L water) and incubated at 25 °C on rotary shakers (150 rpm) for 12–14 days. The fermentation broth (40 L) was filtered through three layers of muslin cloth and extracted with ethyl acetate (40 L) three times to obtain the crude extract (5.78 g). The solvent was removed by a rotary evaporator. The crude extract was applied to a silica gel column chromatography with gradients of CH2Cl2/methanol (MeOH) (100:0, 100:1, 100:2, 100:4, 100:8, 100:16) to give five fractions (Fr1–Fr5). Fr2 was chromatographed over a Sephadex LH-20 (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 1:1 v/v) column and purified by semi-preparative HPLC using 70% MeOH in water to obtain 5 (5 mg) and 6 (10 mg). Fr3 was separated by a Sephadex LH-20 (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 1:1 v/v) column and then purified by semi-preparative HPLC using 65% MeOH in water to obtain 1 (20 mg), 2 (20 mg), and 3 (6 mg). Compound 4 (5 mg) was isolated from Fr4 by semi-preparative HPLC using 70% MeOH as the mobile phase. Fr5 was purified by Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) column to produce 7 (6 mg).

2.5. Zoospore Germination Experiments

A spore suspension of Phytophthora capsici was prepared as previously described [20]. We manually counted the number of zoospores by hemocytometer under a microscope, and the spore suspension was adjusted to the appropriate concentration (1 × 105 cfu mL−1). All assays were repeated at least three times.

2.6. Biological Assays Against S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici In Vitro

S. sclerotiorum was cultured on PDA medium (20 g glucose, 200 g potatoes, 20 g agar in 1 L water) at 25 °C in the dark. P. capsici was cultured on 10% V8 medium (100 mL V8 juice, 1 g CaCO3, 20 g agar in 1 L water) at 25 °C in the dark. The activity of compounds against P. capsici and S. sclerotiorum was referred to the mycelia growth inhibition method as reported [21,22]. These compounds were dissolved in DMSO to prepare the 1.0 × 104 μg/mL stock solution before mixing with PDA media or 10% V8 media below 60 °C. The percentage inhibition rate (%) was calculated as (b − a)/(b − 5) × 100%, where a represented the mycelial diameter (mm) in Petri dishes with compounds, b represented the diameter (mm) of the negative control, and 5 was the diameter (mm) of strain blocks. The corresponding median effective concentration (EC50) values were calculated according to linear regression analysis. All assays were carried out in triplicate.

2.7. Protection Efficacies of Compounds 1 and 2

Healthy cole leaves (Brassica napus) in the bolting stage were sprayed with 1 and 2 (100 μg/mL and 200 μg/mL, spray volume: 5 mL) and subsequently cultivated at 25 °C for 12 h before artificial inoculation with agar pieces (5 mm) of S. sclerotiorum. Results were observed after cultivation at 25 °C for 48–72 h [23]. Tebuconazole was assayed as the positive control, which could inhibit the biosynthesis of ergosterol in fungi. The concentration of tebuconazole was 100 μg/mL and 200 μg/mL, and the spray volume was 5 mL. All assays were repeated at least three times.

The efficacies of 1 and 2 against P. capsici were tested by using zoospores in a greenhouse test [24]. For the assays, water was used as a negative control, and azoxystrobin was used as a positive control at 100 μg/mL. The plants (Nicotiana benthamiana) were cultured in a 100 cm2 pot with vermiculite and reached the vegetative growth stage for testing. The concentrations of 1 and 2 were diluted to 100 μg/mL, and 40 mL were used for each treatment. Then, the zoospore suspension of P. capsici (1 × 105 cfu mL−1) was conducted after 24 h. All the treated plants were placed in the greenhouse at 25 °C with 85% relative humidity for 4–8 days to observe disease status and control effect [25,26]. All assays were repeated at least three times.

2.8. Bioassays with Echinochloa crusgalli and Eclipta prostrata

Herbicidal assays of 1 and 2 were tested in 6 cm diameter Petri dishes against two weeds, Echinochloa crusgalli and Eclipta prostrata. The seeds were first sterilized with 1.0% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite for 10 min. Then, the seeds were washed 2–3 times with water [27]. For these assays, stock solutions of 1 and 2 were diluted to a final concentration of 25 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, 100 μg/mL, and 200 μg/mL, respectively. The test compound solution (2 mL) was transferred into the Petri dishes, and 20 seeds were placed in every dish. The Petri dishes were placed in a growth chamber calibrated to provide 12 h light/12 h darkness at 25 ± 1 °C. Three replicates were used for each treatment. The primary radicle and germ lengths were measured after 7 or 10 days. The results were calculated using the following formula: inhibition rate (%) = ((b − a)/b) × 100, where b is the length of the control and a is the length of the treatment [28].

2.9. Effects of Compounds 1 and 2 on Hyphal Morphology of S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici

Mycelial plugs (5 mm in diameter) of S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici cut from the periphery of a 3-day-old colony were placed in the center of PDA plates amended with compounds 1 and 2 at 50 μg/mL. PDA plates without the test compounds were used as the control. After 72 h at 25 °C, the collected fungal masses were treated as described by reference [29], and then, the treated mycelia were observed under a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Hitachi SU8010, Hitachi Co., Tokyo, Japan).

A mycelial plug (5 mm in diameter) of S. sclerotiorum cut from the periphery of a 3-day-old colony was inoculated in 50 mL of sterilized PDB broth and cultivated at 25 °C with shaking at 150 rpm for 36 h. After that, compounds 1 and 2 with a final concentration of 50 μg/mL were added to the broth, and methanol was set as a control. A mycelial plug (5 mm in diameter) of P. capsici was inoculated into a Petri dish (90 cm) with 15 mL of V8 media and cultivated stationarily at 25 °C for 24 h. After that, compounds 1 and 2 with a final concentration of 50 μg/mL were added to the media. After incubation for 12 h, the mycelia were centrifuged at 4000× g for 10 min at 4 °C; the collected mycelia were treated as described by reference [30]. The mycelial morphology was observed under a transmission electron microscope (TEM) (Hitachi H-7650, Hitachi Co., Tokyo, Japan).

2.10. Statistical Analysis

All bioassays were repeated in triplicate. The results are shown as mean values ± standard deviation. The data were analyzed using SPSS 24.0 with the probit analysis, and the variance analysis between means was calculated by Tukey’s HSD test. When the value p ≤ 0.05, the differences were significant.

3. Results

3.1. Structure Elucidation

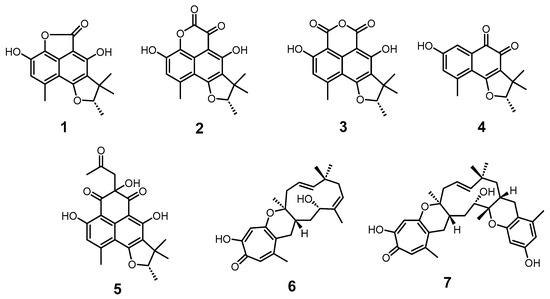

Seven secondary metabolites were isolated from the culture broth of Leptosphaeria sp. FZN28 (Figure 1). The planar structures of compounds 1–7 were determined by mass spectrometry and NMR analysis.

Figure 1.

Structures of compounds 1–7.

Peniciphenalenin E (1): colorless powder; HRESIMS m/z 301.1088 [M+H]+ (calcd for C17H17O5, 301.1071). 1H NMR (500 MHz, actone-d6) and 13C NMR (125 MHz, actone-d6) data, see Table S1 and Figures S1 and S2. All spectroscopic data were identical with the previously reported data [31,32].

Scleroderolide (2): orange solid powder; HRESIMS m/z 329.1021 [M+H]+ (calcd for C18H17O6, 329.1020). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) and 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) data, see Table S2 and Figures S3 and S4. All spectroscopic data were identical with the previously reported data [31,33].

(-)Sclerodin (3): colorless powder; HRESIMS m/z 327.0901 [M-H]- (calcd for C18H15O6, 327.0874). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) and 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) data, see Table S3 and Figures S5 and S6. All spectroscopic data were identical with the previously reported data [34].

Trypethelone (4): purple powder; HRESIMS m/z 273.1130 [M+H]+ (calcd for C16H17O4, 273.1121). 1H NMR (500 MHz, actone-d6) and 13C NMR (125 MHz, actone-d6) data, see Table S4 and Figures S7 and S8. All spectroscopic data were identical with the previously reported data [31,32].

(9S)-3,5,7-trihydroxy-1,8,8,9-tetramethyl-5-(2-oxopropyl)-8,9-dihydro-4H-phenaleno [1,2-b]furan-4,6(5H)-dione (5): pale yellow oil; HRESIMS m/z 399.1440 [M+H]+ (calcd for C22H23O7, 399.1438). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) and 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) data, see Table S5 and Figures S9 and S10. All spectroscopic data were identical with the previously reported data [35].

Neosetophomone B (6): white powder; HRESIMS m/z 385.2458 [M+H]+ (calcd for C24H33O4, 385.2373). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) and 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) data, see Table S6 and Figures S11 and S12. All spectroscopic data were identical with the previously reported data [36].

Noreupenifeldin B (7): colorless powder; HRESIMS m/z 521.2875 [M+H]+ (calcd for C32H41O6, 521.2898). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) and 13C NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) data, see Table S7 and Figures S13 and S14. All spectroscopic data were identical with the previously reported data [36].

3.2. Biological Activity

To explore the antimicrobial potential of the isolated compounds, compounds 1, 2, and 6, which are in large quantities, were screened for antimicrobial activities against phytopathogens at a concentration of 50 μg/mL. According to the results, 1 had broad-spectrum activity against S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici with inhibition rates of 94.2% and 80.0%, respectively. Compound 2 exhibited good activity against S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici with inhibition rates of 75.0% and 74.5%, respectively. However, compound 6 showed moderate antimicrobial activity with inhibition rates of 47.8% and 46.2% against P. capsici and S. sclerotiorum, respectively. In addition, the EC50 values of compound 1 against P. capsici and S. sclerotiorum were 8.8 and 10.8 μg/mL, respectively. The EC50 values of compound 2 against the above two strains were 20.4 and 14.8 μg/mL, while the EC50 values of compound 6 exceeded 50 μg/mL (Table 1).

Table 1.

EC50 (μg/mL) compounds 1, 2, and 6 against three plant-pathogenic strains.

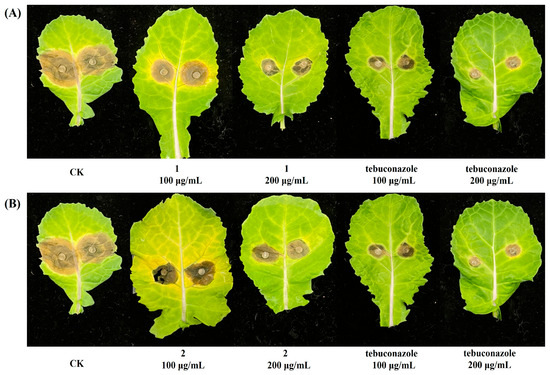

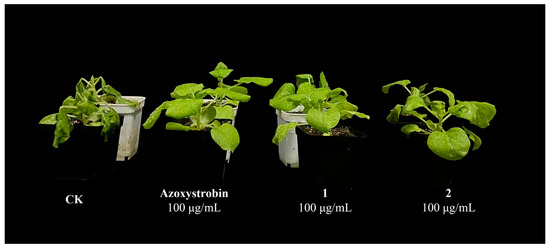

3.3. Protection Efficacies of 1 and 2 Against S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici

To further investigate the roles of compounds 1 and 2 against S. sclerotiorum, we examined their effects against S. sclerotiorum-infected cole leaves. The results revealed that 200 μg/mL of 1 could successfully inhibit disease development in S. sclerotiorum-infected cole leaves with an inhibitory efficacy of 66.9%. At a concentration of 200 μg/mL, compound 2 showed significant activity with an inhibitory efficacy of 61.0% (Figure 2 and Table 2). Moreover, we further investigated the protective activities of compounds 1 and 2 against P. capsici in greenhouse tests. The results in Table 3 and Figure 3 showed that 100 μg/mL of compound 1 could effectively prevent infection of P. capsici with a protection efficacy of 69.1%, comparable to the positive control azoxystrobin.

Figure 2.

(A) Protective effects of compound 1 against S. sclerotiorum -infected cole leaves. (B) Protective effects of compound 2 against S. sclerotiorum-infected cole leaves. CK, control check.

Table 2.

Protective efficacy of compounds 1 and 2 on cole leaves infected by S. sclerotiorum.

Table 3.

Protection efficacies of compounds 1 and 2 against P. capsici in greenhouse tests.

Figure 3.

Protective effects of compounds 1 and 2 against P. capsici in greenhouse tests. CK, control check.

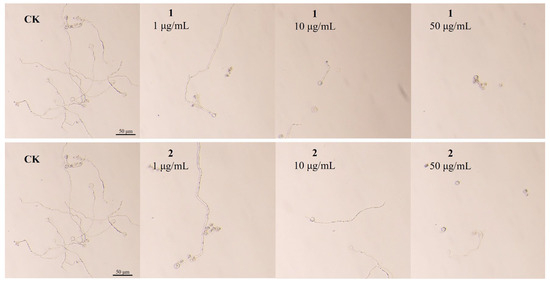

3.4. Effects of Compounds 1 and 2 on Spore Germination of P. capsici

The effects of compounds 1 and 2 on zoospore germination of P. capsici are shown in Figure 4; zoospore germination was significantly delayed by the two compounds (Table S8). With the concentration increase in compounds 1 and 2, the germination rate of zoospores was decreased gradually, and 50 μg/mL of compounds 1 and 2 totally blocked zoospore germination. These results suggest that compounds 1 and 2 have good activities in inhibiting zoospore germination and germ tube elongation of P. capsici.

Figure 4.

Effect of compounds 1 and 2 on P. capsici spore germination at 1, 10, and 50 μg/mL.

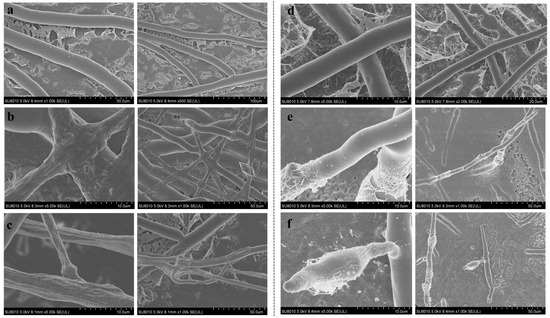

3.5. Effects of Compounds 1 and 2 on the Hyphal Morphology and Ultrastructure of S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici

To better understand the mode of antifungal action of compounds 1 and 2, we observed the mycelial morphology and ultrastructure of S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici treated with two compounds via SEM and TEM, respectively. The SEM results showed that the control sample exhibited a fine morphology of smooth and uniform (Figure 5a,d). However, in the compound-treated samples, an altered morphology was characterized by twisted and deformed hyphae (Figure 5b,c,e,f).

Figure 5.

Effects of compounds 1 and 2 on the hyphal morphology of S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici. (a) Healthy hyphae of S. sclerotiorum. (b,c) Hyphae of S. sclerotiorum treated with compounds 1 and 2 (50 µg/mL). (d) Healthy hyphae of P. capsici. (e,f) Hyphae of P. capsici treated with compounds 1 and 2 (50 µg/mL).

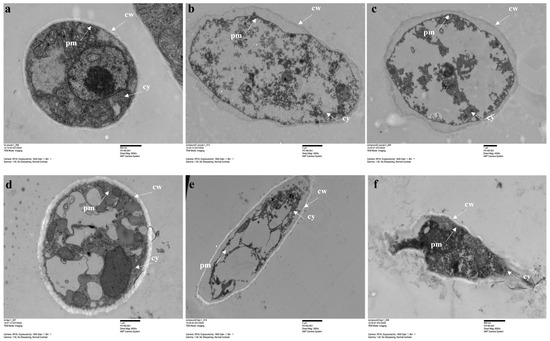

Moreover, the effects of compounds 1 and 2 on the hyphal ultrastructure of S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici were observed via TEM. The control sample displayed a normal hyphal ultrastructure of intact and smooth cell membranes, in addition to well-organized cytoplasm and mitochondria (Figure 6a,d). In the sample treated with two compounds, the hyphae’s cell membranes became rough and invaginated, and organelles were disordered (Figure 6b,c,e,f). Furthermore, it was observed that cytoplasm was lost due to plasma membrane dissociation and cell wall disruption in the treatment.

Figure 6.

Effects of compounds 1 and 2 on the hyphal cell ultrastructure of S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici. (a) Healthy hyphae of S. sclerotiorum. (b,c) Hyphae of S. sclerotiorum treated with compounds 1 and 2 (50 µg/mL). (d) Healthy hyphae of P. capsici on the control plate. (e,f) Hyphae of P. capsici treated with compounds 1 and 2 (50 µg/mL).

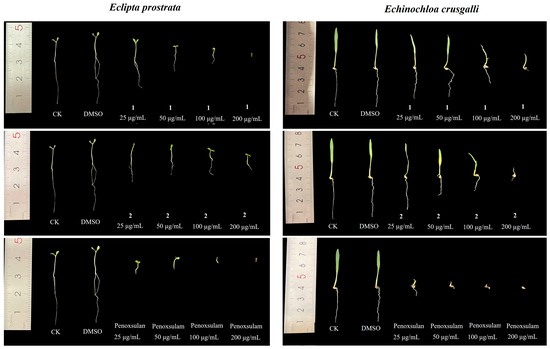

3.6. Bioassays with Weed Species

In recent years, interest in natural products with herbicidal activity as new tools for integrated weed management has increased; therefore, we further tested the herbicidal activity of compounds 1 and 2. An assay to evaluate the effectiveness of compounds 1 and 2 on the radicle and germ elongation of two weed species was conducted using the above method. The results showed that compounds 1 and 2 exhibited great inhibitory activities against radicle and germ growth. As shown in Figure 7 and Table 4, compounds 1 and 2 almost completely inhibited the radicle growth of the monocotyledon species Echinochloa crusgalli at 200 μg/mL with inhibition ratios of 97.2% and 91.7%, respectively. Additionally, compound 1 had good activity against the radicle and germ elongation of dicotyledon species Eclipta prostrata, with an inhibition ratio of 100% at 200 μg/mL, which was consistent with the positive control penoxsulam at the same concentration.

Figure 7.

Effects of compounds 1 and 2 against the radicle and germ growth of two weed seeds.

Table 4.

Inhibition rate of compounds 1 and 2 against the radicle and germ growth of two weed seeds.

4. Discussion

The sustainability of modern agriculture is threatened by plant diseases caused by S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici and the emergence of herbicide-resistant weeds [37,38,39]. Natural products play an important role in developing fungicides and herbicides [40]. This study focused on the secondary metabolites from Leptosphaeria sp. FZN28 in Mecopoda elongata, with compounds 1 and 2 showing potent antimicrobial and herbicidal activities.

In biological assays, compound 1 exhibited superior efficacy against P. capsici and S. sclerotiorum compared to compound 2, with EC50 values of 8.8/10.8 μg/mL and 20.4/14.8 μg/mL, respectively. Notably, compound 1 prevented infection of P. capsici with a protection efficacy of 69.1% in the greenhouse test, though its efficacy was slightly lower than the positive control, which suggested it had potential to serve as a candidate through further modification.

SEM and TEM observations provided key insights into the mechanism of action of compounds 1 and 2. The twisted hyphae, disrupted cell membranes, and disordered organelles in treated pathogens differed from the intact structures in controls, implying the two compounds could target cell membrane integrity and cytoplasmic homeostasis.

In bioassays with weeds, compounds 1 and 2 showed concentration-dependent inhibition of E. crusgalli and E. prostrata. At 200 μg/mL, the efficacies of compound 1 in inhibiting radicle and germ growth were consistent with the positive control penoxsulam, while compound 2 exhibited slightly lower efficacy. This broad-spectrum weed control, including monocotyledon weeds and dicotyledon weeds, suggested potential for compounds 1 and 2 to be developed for multi-functional biopesticides.

Natural products are increasingly considered as potential candidates for biocontrol. In this paper, compounds 1 and 2 not only have different structures but also exhibit a range of biological activities against different plant diseases and weeds, making them attractive for development in the field of agriculture. Despite advantages in the use of natural products, there remain obstacles that hinder their full potential, such as low yield and intrinsic instability. To address these concerns, the biosynthesis research and chemical synthesis study emerged as a promising solution to overcome these barriers.

5. Conclusions

Over the last decades, microorganisms have played an important role in the discovery of valuable natural resources. In this study, seven secondary metabolites were isolated from Leptosphaeria sp. FZN28 in Mecopoda elongata. Bioassay tests showed that compounds 1 and 2 could effectively control S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici, which were reported for the first time in this study. The action mode of 1 and 2 against S. sclerotiorum and P. capsici was attributed to the disruption of plasma membrane integrity, ultrastructure distortion, and morphological alteration of hyphae, leading to cell death. Furthermore, 1 and 2 not only exhibited a potent activity against radicle and germ growth of the dicotyledon species E. prostrata but could also inhibit radicle and germ of monocotyledon species E.crusgalli. Taken together, these findings enrich a potent source for the production of agrochemicals to ensure food security and highlight their potential as leading compounds for the development of new biopesticides.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122673/s1, Figure S1: 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz, acetone-d6) of 1; Figure S2: 13C NMR spectrum (125 MHz, acetone-d6) of 1; Figure S3: 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) of 2; Figure S4: 13C NMR spectrum (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) of 2; Figure S5: 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz, CDCl3) of 3; Figure S6: 13C NMR spectrum (125 MHz, CDCl3) of 3. Figure S7. 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz, acetone-d6) of 4. Figure S8: 13C NMR spectrum (125 MHz, acetone-d6) of 4; Figure S9: 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) of 5; Figure S10: 13C NMR spectrum (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) of 5; Figure S11: 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz, CDCl3) of 6; Figure S12: 13C NMR spectrum (125 MHz, CDCl3) of 6; Figure S13: 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz, CDCl3) of 7; Figure S14. 13C NMR spectrum (125 MHz, CDCl3) of 7; Table S1: 1H NMR (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) data of 1 in acetone-d6; Table S2: 1H NMR (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) data of 2 in DMSO-d6; Table S3: 1H NMR (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) data of 3 in CDCl3; Table S4: 1H NMR (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) data of 4 in acetone-d6; Table S5: 1H NMR (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) data of 5 in DMSO-d6; Table S6: 1H NMR (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) data of 6 in CDCl3; Table S7: 1H NMR (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) data of 7 in CDCl3; Table S8: Effects of compounds 1 and 2 on spore germination of P. capsici.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y. and Y.L.; methodology, Y.L., C.P. and M.Y.; software, L.C. and S.S.; validation, Y.L. and Q.Z.; formal analysis, Y.L. and L.C.; investigation, C.P. and B.H.; resources, W.Y.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, Y.Y.; project administration, Y.L. and W.Y.; funding acquisition, Y.L. and W.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1401000), the Jiangsu Agriculture Science and Technology Innovation Fund (CX(23)3018), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32402412), the Jiangsu Funding Program for Excellent Postdoctoral Talent (2024ZB317), and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF under Grant Number GZC20240722.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscope |

References

- Rodrigues, T.; Reker, D.; Schneider, P.; Schneider, G. Counting on natural products for drug design. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, S.; Das, G.; Sen, S.K.; Shin, H.; Patra, J.K. Endophytes: A treasure house of bioactive compounds of medicinal importance. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Li, G.; Lou, H.X. Structural diversity and biological activities of novel secondary metabolites from endophytes. Molecules 2018, 23, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.X.; Xiong, Y.M.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.N.; Wang, Y.; Jia, X.W.; Yang, X.P.; Tan, L.L.; Xu, C.P. Antifungal Macrocyclic Trichothecenes from the Insect-Associated Fungus Myrothecium roridum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 13033–13039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.; Deyrup, S.T.; Shim, S.H. Endophyte-produced antimicrobials: A review of potential lead compounds with a focus on quorum-sensing disruptors. Phytochem. Rev. 2021, 20, 543–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Klimova, E.; Rodríguez-Peña, K.; Sánchez, S. Endophytes as sources of antibiotics. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 134, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajamanikyam, M.; Vadlapudi, V.; Amanchy, R.; Upadhyayula, S.M. Endophytic fungi as novel resources of natural therapeutics. Biol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 60, e17160542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.S.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Zheng, C.J.; Guo, L.; Li, W.C.; Sun, P.X.; Qin, L.P. Recent developments and future prospects of antimicrobial metabolites produced by endophytes. Microbiol. Res. 2010, 165, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Peng, G.; Kutcher, R.; Yu, F.Q. Genetic diversity and population structure of Leptosphaeria maculans isolates in Western Canada. J. Genet. Genom. 2021, 48, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitt, B.D.L.; Brun, H.; Barbetti, M.J.; Rimmer, S.R. World-Wide importance of phoma stem canker (Leptosphaeria maculans and L. biglobosa) on oilseed rape (Brassica napus). Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2006, 114, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Liu, C.; Fernando, D.W.G.; Lang, R.; Mclaren, D.L.; Johnson, E.N.; Kutcher, H.R.; Singh, G.; Turkington, T.K.; Yu, F. Early fungicide treatment reduces blackleg on canola but yield benefit is realized only on susceptible cultivars under high disease pressure. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 43, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, C.; Draeger, S.; Schulz, B. A fine line-endophytes or pathogens in Arabidopsis thaliana. Fungal Ecol. 2012, 5, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, M.; Gade, A.; Zimowska, B.; Ingle, A.P.; Ingle, P. Harnessing the potential of novel bioactive compounds produced by endophytic phoma spp.- biomedical and agricultural applications. Acta Sci. Pol.-Hortorum Cultus 2020, 19, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Liu, T.K.; Shi, Q.; Yang, X.L. Sesquiterpenoids and diterpenes with antimicrobial activity from Leptosphaeria sp. XL026 2019, an endophytic fungus in Panax notoginseng. Fitoterapia 2019, 137, 104243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Liu, S.C.; Sun, B.; Niu, S.; Li, E.; Liu, X.Z.; Che, Y.S. Polyketides from the ascomycete fungus Leptosphaeria sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerke, E.C. Crop losses to pests. J. Agric. Sci. 2006, 144, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Li, X.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, P. Antifungal secondary metabolites produced by the fungal endophytes: Chemical diversity and potential use in the development of biopesticides. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 689527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, A.; Were, E.; Hilger, T.; Zahir, Z.A.; Ahmad, M.; Hussain, A.; Rasche, F. Bacterial secondary metabolites: Possible mechanism for weed suppression in wheat. Can. J. Microbiol. 2023, 69, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Z.F.; Chen, L.Y.F.; Zhu, M.Y.; Wang, D.C.; Jing, M.F.; Chen, Y.L.; Sun, Z.Q.; Wang, Y.M.; He, B.; et al. New metabolites from Streptomyces pseudovenezuelae NA07424 and their potential activity of inducing resistance in plants against Phytophthora capsici. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.Q.; Sun, W.B.; Meng, J.J.; Wang, A.; Wang, X.H.; Tian, J.; Fu, X.X.; Dai, J.G.; Liu, Y.; Lai, D.W.; et al. Bioactive bisnaphtho-γ-pyrones from rice false smut pathogen Ustilaginoidea virens. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 3501–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Wang, X.; Li, K.; Li, T.X.; Wang, J.J.; Yao, K.C.; Cao, L.L.; Zhao, S.S.; Ye, Y.H. Design, synthesis, and antifungal activity of carboxamide derivatives possessing 1,2,3-triazole a potential succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2019, 156, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.S.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Yan, W.; Cao, L.L.; Xiao, Y.; Ye, Y.H. Chaetomium globosum CDW7, a potential biological control strain and its antifungal metabolites. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2017, 364, fnw287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.G.; Dou, M.L.; Xie, J.; Hou, S.; Liu, Q.F.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, B.J.; Zheng, S.; Yin, F.M.; Zhang, M.; et al. Discovery of zeylenone from Uvaria grandiflora as a potential botanical fungicide. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 5407–5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, G.; Shen, L.; Qin, Y.; Li, H.; Ye, J.; Qi, Z.; Cao, Z. Selection of pepper blight resistance and control fungicide of pepper varieties in Hainan province. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2019, 58, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Q.; Hu, Z.; Li, T.; Tao, J.; Dou, M.; Zhang, M.; Shao, Y.; et al. Discovery of N-Aryl-pyridine-4-ones as novel potential agrochemical fungicides and bactericides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 13904–13913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ma, J.J.; Liu, B.; Huang, L.; Sang, X.Q.; Zhou, L.J. Herbicidal spectrum, absorption and transportation, and physiological effect on Bidens pilosa of the natural alkaloid berberine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 6100–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.L.; Yan, W.; Gu, C.G.; Wang, Z.Y.; Zhao, S.S.; Kang, S.; Khan, B.; Zhu, H.L.; Li, J.; Ye, Y.H. New alkylitaconic acid derivatives from Nodulisporium sp. A21 and their auxin herbicidal activities on weed seeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 2811–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Huang, S.-X.; Ma, Z.; Wen, Z.; Liu, C.; Xiang, W. Discovery of frenolicin B as potential agrochemical fungicide forcontrolling fusarium head blight on wheat. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 2108–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yuan, S.; Sun, J.; Li, Q.; Jiang, W.; Cao, J. Ethyl p -coumarate exerts antifungal activity in vitro and in vivo against fruit Alternaria alternata via membrane-targeted mechanism. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 278, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsebai, M.F.; Kehraus, S.; Lindequist, U.; Sasse, F.; Shaaban, S.; Gütschow, M.; Josten, M.; Sahl, H.G.; König, G.M. Antimicrobial phenalenone derivatives from the marine-derived fungus Coniothyrium cereale. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 802–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhu, R.; Yi, W.; Chai, W.Y.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Lian, X.Y. Peniciphenalenins A-F from the culture of a marine-associated fungus Penicillium sp. ZZ901. Phytochemistry 2018, 152, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsebai, M.F.; Natesan, L.; Kehraus, S.; Mohamed, I.E.; Schnakenburg, G.; Sasse, F.; Shaaban, S.; Gütschow, M.; König, G.M. HLE-inhibitory alkaloids with a polyketide skeleton from the marine-derived fungus Coniothyrium cereale. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 2282–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.; Maddah, F.E.; Kehraus, S.; Egereva, E.; Piel, J.; Brachmannb, A.O.; König, G.M. Phenalenones: Insight into the biosynthesis of polyketides from the marine alga-derived fungus Coniothyrium cereale. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 8071–8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayer, W.A.; Hoyano, Y.; Pedras, M.S.; Altena, I.V. Metabolites produced by the Scleroderris canker fungus, Gremmeniella abietina. Part 1. Can. J. Chem. 1986, 64, 1585–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Elimat, T.; Raja, H.A.; Ayers, S.; Kurina, S.J.; Burdette, J.E.; Mattes, Z.; Sabatelle, R.; Bacon, J.W.; Colby, A.H.; Grinstaff, M.W.; et al. Meroterpenoids from Neosetophoma sp.: A Dioxa [4.3.3] propellane ring system, potent cytotoxicity, and prolific expression. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberto, D.; Serra, A.A.; Sulmon, C.; Gouesbet, G.; Couee, I. Herbicide-related signaling in plants reveals novel insights for herbicide use strategies, environmental risk assessment and global change assessment challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 569, 1618–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, D.C.; Ribiero, O.K. Phytophthora diseases worldwide. Plant Pathol. 1998, 47, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- William, U.; Michelle, G.; Misar, C.G.; Gulya, T.J.; Seiler, G.J.; Markell, S.G. Multiple species of asteraceae plants are susceptible to root infection by the necrotrophic fungal pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Duan, C.B.; Jin, B.; Ali, A.S.; Han, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.Z.; Zhang, W.H.; Gu, Y.C. Recent advances in the natural products-based lead discovery for new agrochemicals. Adv. Agrochem. 2023, 2, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).