Forest-to-Tea Conversion Intensifies Microbial Phosphorus Limitation and Enhances Oxidative Enzyme Pathways

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Sampling

2.3. Soil Basic Property and Nutrient Analysis

2.4. Soil Microbial Composition Analysis

2.5. Soil Extracellular Enzyme Activity Analysis and Assessment of Microbial Metabolic Limitation

2.6. Assessment of Microbial Metabolic Limitation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Soil Basic Properties and Nutrients

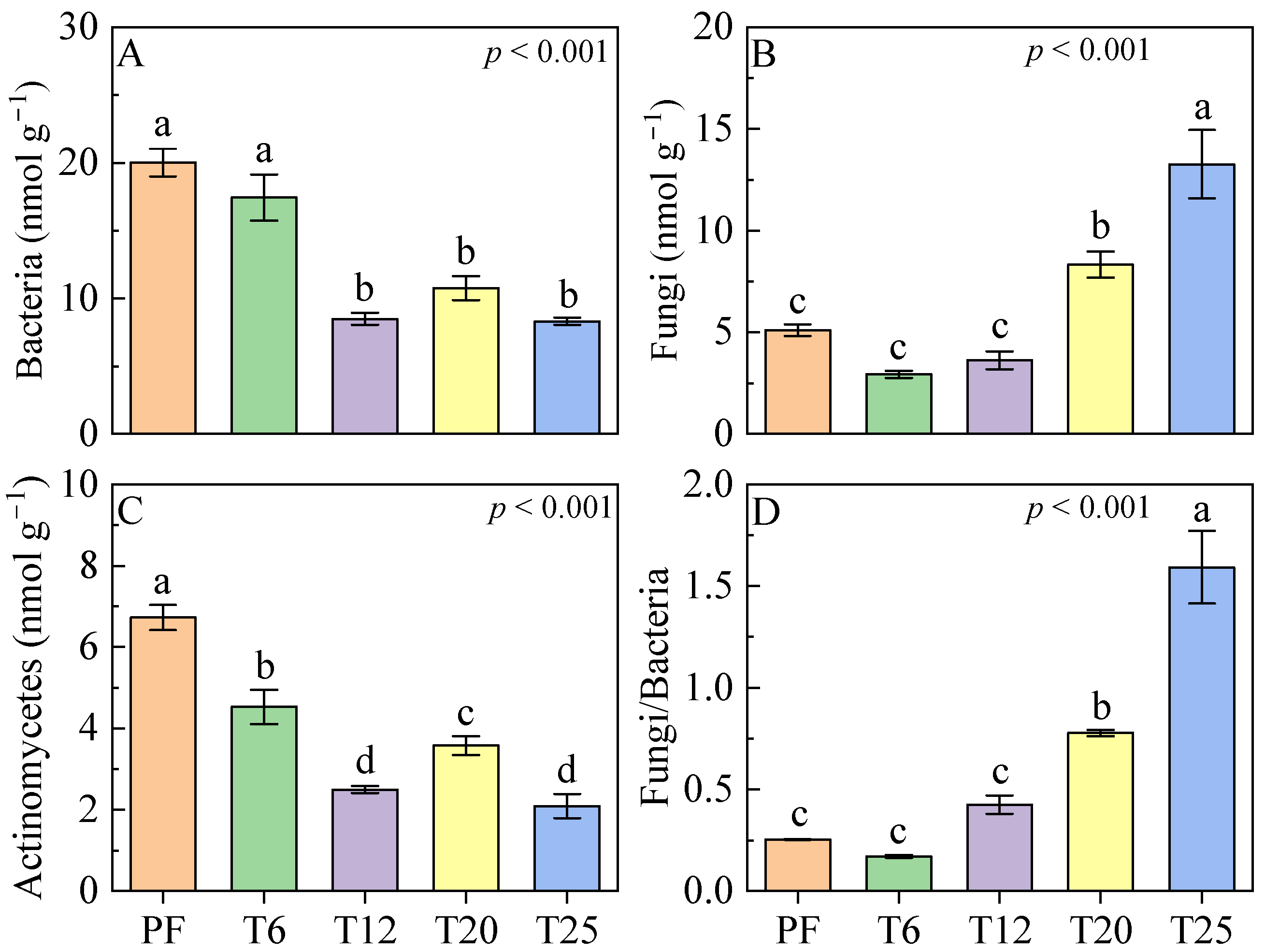

3.2. Soil Microbial Composition

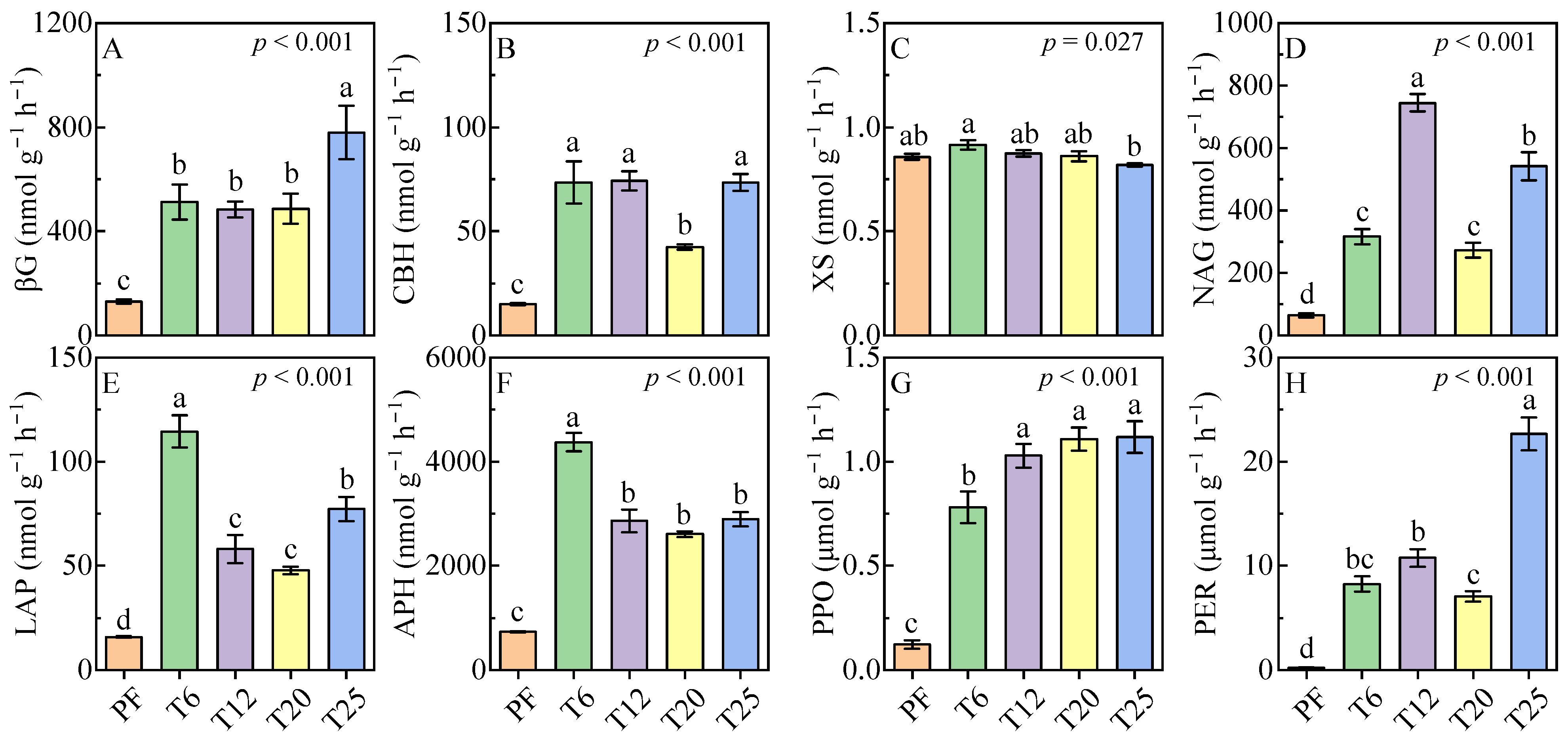

3.3. Soil Enzyme Activity

3.4. Soil Enzyme Stoichiometry and Microbial Metabolic Limitation

3.5. Factors Regulating Soil Enzyme Stoichiometry and Microbial Metabolic Limitation

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Tea Planted on Soil Basic Properties, Nutrients, and Microbial Composition

4.2. Effects of Tea Planted on Soil Extracellular Enzymes

4.3. Effects of Tea Planted on Microbial Metabolic Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PLS-PM | Partial least squares path modeling |

| C | Carbon |

| N | Nitrogen |

| P | Phosphorus |

| SOC | Soil organic carbon |

| PLFA | Phospholipid fatty acid |

| PF | Forest land |

| T6 | 6-year-old tea garden |

| T12 | 12-year-old tea garden |

| T20 | 20-year-old tea garden |

| T25 | 25-year-old tea garden |

| SWC | Soil water content |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

| TP | Total phosphorus |

| MBC | Microbial biomass carbon |

| MBN | Microbial biomass nitrogen |

| MBP | Microbial biomass phosphorus |

| M-C/N | The ratio of Microbial biomass carbon/Microbial biomass nitrogen |

| M-C/P | The ratio of Microbial biomass carbon/Microbial biomass phosphorus |

| M-N/P | The ratio of Microbial biomass nitrogen/Microbial biomass phosphorus |

| Bac | Bacteria |

| Fun | Fungi |

| Act | Actinomycetes |

| Fun/Bac | The ratios of fungi to bacteria |

| βG | β-1,4-glucosidase |

| CBH | β-D-cellobiohydrolase |

| XY | β-1,4-xylosidase |

| NAG | β-1,4-N-acetylglucosaminidase |

| LAP | leucine aminopeptidase |

| APH | acid phosphatase |

| PPO | polyphenol oxidase |

| PER | peroxidase |

| MUB | 4-methylumbelliferyl |

| AMC | 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin |

| L-DOPA | L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine |

| ANOVA | One-way analysis of variance |

Appendix A

References

- Zou, S.; Huang, C.; Feng, T.; Chen, Y.; Bai, X.; Li, W.; He, B. Effects of Woodland Conversion to Tea Plantations and Tea Planting Age on Soil Organic Carbon Accrual in Subtropical China. Forests 2024, 15, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jin, J.; Yu, P.; Fu, W.; Morrison, L.; Lin, H.; Meng, M.; Zhou, X.; Lv, Y.; Wu, J. Converting evergreen broad-leaved forests into tea and Moso bamboo plantations affects labile carbon pools and the chemical composition of soil organic carbon. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 135225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhu, B.; Chen, G.; Ni, X.; Zhou, L.; Su, H.; Cai, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhu, J.; Ji, C.; et al. Loss of soil microbial residue carbon by converting a tropical forest to tea plantation. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 818, 151742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, L.; Shao, G.; Pang, Y.; Dai, H.; Zhang, L.; Yan, P.; Zou, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Zamanian, K.; et al. Enhanced soil quality after forest conversion to vegetable cropland and tea plantations has contrasting effects on soil microbial structure and functions. Catena 2022, 211, 106029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ni, K.; Shi, Y.; Yi, X.; Zhang, Q.; Fang, L.; Ma, L.; Ruan, J. Effects of long-term nitrogen application on soil acidification and solution chemistry of a tea plantation in China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 252, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Yao, H.; Huang, C. Study on Soil Microbial Properties and Enzyme Activities in Tea Gardens. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2005, 19, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.B.; Liu, C.Y.; Guo, C.; Duan, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, C.Y. Soil Acidification and Its Temporal Changes in Tea Plantations of Guizhou Province, Southwest China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 5648–5658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yanagisawa, N.; Asahina, M.; Yamashita, H.; Ikka, T. Soil chemical factors contributing to differences in bacterial communities among tea field soils and their relationships with tea quality. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1540659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Zhou, J.; Pan, W.; Tang, R.; Ma, Q.; Xu, M.; Qi, T.; Ma, Z.; Fu, H.; Wu, L. Impact of N application rate on tea (Camellia sinensis) growth and soil bacterial and fungi communities. Plant Soil 2022, 475, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Ji, L.; Wan, Q.; Li, H.; Li, R.; Yang, Y. Short-Term Effects of Bio-Organic Fertilizer on Soil Fertility and Bacterial Community Composition in Tea Plantation Soils. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Li, L.; Liu, H.; Yao, J.; Ma, C.; Pu, L.; Lei, Z. Biochar, Organic Fertilizer, and Bio-Organic Fertilizer Improve Soil Fertility and Tea Quality. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Li, Y.Q.; Wang, L.L.; Duan, Y.L.; Yao, B.; Chen, Y.; Cao, W.J. Soil extracellular enzyme stoichiometry reflects microbial metabolic limitations in different desert types of northwestern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 874, 162504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C.L.; Zhang, Z.H.; Zhu, X.M.; Wei, W.T.; Mustafa, A.; Chen, W.B.; Mao, Q.G.; Mo, J.M.; Li, S.; Lu, X.K. Divergent microbial metabolic limitations across soil depths after two decades of high nitrogen inputs in a primary tropical forest. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, 70440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Long, Z.J.; Ren, P.; Ren, C.J.; Cao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hu, S.L. Differential responses of soil hydrolytic and oxidative enzyme activities to the natural forest conversion. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 716, 136414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, G.; Ye, J.; Wang, H.; He, H. Soil metagenomic analysis on changes of functional genes and microorganisms involved in nitrogen-cycle processes of acidified tea soils. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 998178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunito, T.; Moro, H.; Mise, K.; Sawada, K.; Otsuka, S.; Nagaoka, K.; Fujita, K. Ecoenzymatic stoichiometry as a temporally integrated indicator of nutrient availability in soils. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 70, 246–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Lauber, C.L.; Weintraub, M.N.; Ahmed, B.; Allison, S.D.; Crenshaw, C.; Contosta, A.R.; Cusack, D.; Frey, S.; Gallo, M.E.; et al. Stoichiometry of soil enzyme activity at global scale. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 1252–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.X.; Bing, H.J.; Moorhead, D.L.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Ye, L.P.; Yu, J.L.; Zhang, S.P.; Wang, X.; Peng, S.S.; Guo, X.; et al. Ecoenzymatic stoichiometry reveals widespread soil phosphorus limitation to microbial metabolism across Chinese forests. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Moorhead, D.L.; Peng, S.; Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Peñuelas, J. Predicting microbial nutrient limitations from a stoichiometry-based threshold framework. Innov. Geosci. 2024, 2, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Zheng, Z.; Li, T.; He, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T. Effect of tea plantation age on the distribution of glomalin-related soil protein in soil water-stable aggregates in southwestern China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 1973–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Ni, K.; Shi, Y.; Yi, X.; Ji, L.; Wei, S.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Ma, Q.; et al. Metagenomics reveals N-induced changes in carbon-degrading genes and microbial communities of tea (Camellia sinensis L.) plantation soil under long-term fertilization. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, Q.; Zhou, Y.; You, W. Changes in soil properties and enzyme stoichiometry in three different forest types changed to tea plantations. Forests 2023, 14, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Zhang, K.R.; Guo, W.T.; Huang, H.J.; Gou, Z.Y.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Oh, K.; Fang, C.G.; Luo, L. The effects of partial substitution of fertilizer using different organic materials on soil nutrient condition, aggregate stability and enzyme activity in a tea plantation. Plants 2023, 12, 3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, H.; Fan, L.; Wang, D.; Yan, P.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Han, W. Organic management practices shape the structure and associations of soil bacterial communities in tea plantations. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 163, 103975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.L.; Liu, X.H.; Liu, P.; Chen, L. Enzymatic stoichiometry reveals the metabolic limitations of soil microbes under nitrogen and phosphorus addition in Chinese fir plantations. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhang, H.; Tong, Y.; Wen, D.; Xia, X.; Wang, H.; Luo, Y.; Barceló, D. Response of soil enzyme activities and bacterial communities to the accumulation of microplastics in an acid cropped soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 135634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.P.; Tsai, C.F.; Rekha, P.D.; Ghate, S.D.; Huang, H.Y.; Hsu, Y.H.; Liaw, L.L.; Young, C.C. Agricultural management practices influence the soil enzyme activity and bacterial community structure in tea plantations. Bot. Stud. 2021, 62, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, S.; Huang, C.; Chen, Y.; Bai, X.; Li, W.; He, B. Patterns of nitrogen and phosphorus along a chronosequence of tea plantations in subtropical China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, E.D.; Brookes, P.C.; Jenkinson, D.S. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987, 19, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frostegard, A.; Tunlid, A.; Baath, E. Phospholipid fatty-acid composition, biomass, and activity of microbial communities from two soil types experimentally exposed to different heavy metals. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 3605–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, D.P.; Weintraub, M.N.; Grandy, A.S.; Lauber, C.L.; Rinkes, Z.L.; Allison, S.D. Optimization of hydrolytic and oxidative enzyme methods for ecosystem studies. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1387–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Wu, L.; Wang, D.; Fu, J.; Shen, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Fan, L.; Wenyan, H. Soil acidification in Chinese tea plantations. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 715, 136963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Zhao, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, S. Soil organic carbon content and its relationship with the stand age in tea plantations (Camellia sinensis L.) in Fujian Province, China. Land 2024, 13, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Pan, W.; Yang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Wanek, W.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Marsden, K.A.; Liang, G.; Chadwick, D.R.; Gregory, A.S.; et al. Soil carbon sequestration enhanced by long-term nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization. Nat. Geosci. 2025, 18, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Li, W.; Dai, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Daniell, T.J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Yin, W.; Wang, X. Patterns and determinants of microbial- and plant-derived carbon contributions to soil organic carbon in tea plantation chronosequence. Plant Soil 2024, 505, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Xie, S.; Fan, H.; Duan, C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z. Tea cultivation: Facilitating soil organic carbon accumulation and altering soil bacterial community—Leishan County, Guizhou Province, Southwest China. PeerJ 2025, 13, e18683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Ou, X.; Chen, D.; Li, Y.; McMillan, C.; Ge, T.D.; Liu, J.; Xue, M.; Wang, C.; Shen, W. Shifts in fungal communities and potential functions under Masson pine forest-to-tea plantation conversion in subtropical China. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Hu, Q.; Huang, F.; Bao, D.; Li, X.; Dong, C.; Zhu, S.; Fu, J.; Yan, P. Long-term agricultural management alters soil fungal communities and soil carbon and nitrogen contents in tea plantations. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zheng, Z.; Li, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; He, S.; Liu, T. Effect of tea plantation age on the distribution of soil organic carbon fractions within water-stable aggregates in the hilly region of Western Sichuan, China. Catena 2015, 133, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zheng, Z.; Zhu, R. Long-term tea plantation effects on composition and stabilization of soil organic matter in Southwest China. Catena 2021, 199, 105132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, A.; Lin, C.; Wang, H.; Yu, J.; Ding, H.; Zhang, Y. Response of soil microbial communities and functions to long-term tea (Camellia sinensis L.) planting in a subtropical region. Forests 2023, 14, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yang, W.; Hu, J.; Liu, J.; Ding, W.; Huang, J. Effects of tea planting age on soil microbial biomass C:N:P stoichiometry and microbial quotient. Plant Soil Environ. 2023, 69, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yi, X.; Ni, K.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Cai, Y.; et al. Patterns and abiotic drivers of soil organic carbon in perennial tea (Camellia sinensis L.) plantation system of China. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 116925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zhou, F.; Jiang, T. Assessing soil nutrient and microbial biomass in tea plantation regions of Guizhou Province. J. Irrig. Drain. 2018, 37, 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, C.; Xue, D.; Yao, H. Microbial biomass, community diversity, and enzyme activities in response to urea application in tea orchard soils. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2010, 41, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Liu, Y.; Xue, D. Influence of tea cultivation on soil microbial biomass and substrate utilization pattern. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2006, 37, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Shen, C.; Gao, K.; Feng, S.; Li, D.; Hu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Luo, Z. Microbial nutrient limitation of different tea cultivars: Evidence from five representative cultivars. Agronomy 2024, 14, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Penuelas, J.; Sardans, J.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, F.; Wang, F. Organic management improves soil P availability via increasing inorganic P solubilization in tea plantations. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 39, 104223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, D.O.N.; Abbas, F.; Mei, X.; Yan, C.; Zeng, Z.; Mo, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y. Metabarcoding of organic tea (Camellia sinensis L.) chronosequence plots elucidates soil acidification-induced shifts in microbial community structure and putative function. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 178, 104580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Cao, F.; Wang, G. Soil microbiological properties and enzyme activity in Ginkgo-tea agroforestry compared with monoculture. Agrofor. Syst. 2013, 87, 1201–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Properties | Tea Planted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF | T6 | T12 | T20 | T25 | |

| SWC (%) | 33.37 ± 1.88 ab | 35.62 ± 0.65 ab | 36.08 ± 0.57 a | 32.22 ± 1.49 b | 33.84 ± 0.42 ab |

| pH | 4.40 ± 0.05 a | 4.06 ± 0.02 b | 3.88 ± 0.01 c | 3.84 ± 0.01 c | 3.67 ± 0.03 d |

| SOC (g kg−1) | 20.22 ± 0.25 a | 16.00 ± 0.20 b | 12.45 ± 0.13 c | 13.07 ± 0.34 cd | 11.80 ± 0.59 d |

| TN (g kg−1) | 1.21 ± 0.02 c | 1.86 ± 0.02 a | 1.43 ± 0.02 b | 1.18 ± 0.01 c | 1.44 ± 0.05 b |

| TP (g kg−1) | 0.71 ± 0.01 d | 0.79 ± 0.04 c | 0.99 ± 0.01 a | 0.69 ± 0.01 d | 0.93 ± 0.01 b |

| SOC/TN | 16.75 ± 0.24 a | 8.62 ± 0.09 c | 8.72 ± 0.18 c | 11.06 ± 0.33 b | 8.18 ± 0.12 c |

| SOC/TP | 28.47 ± 0.37 a | 20.49 ± 0.88 b | 12.53 ± 0.22 c | 18.97 ± 0.78 b | 12.75 ± 0.57 c |

| TN/TP | 1.7 ± 0.03 b | 2.38 ± 0.11 a | 1.44 ± 0.03 c | 1.71 ± 0.02 b | 1.56 ± 0.05 bc |

| MBC (mg kg−1) | 169.78 ± 2.91 a | 182.47 ± 12.65 a | 83.48 ± 6.76 b | 30.43 ± 2.67 c | 70.51 ± 4.23 b |

| MBN (mg kg−1) | 2.44 ± 0.07 d | 10.67 ± 0.66 b | 9.67 ± 1.28 b | 6.02 ± 0.62 c | 20.03 ± 0.44 a |

| MBP (mg kg−1) | 2.11 ± 0.14 c | 2.78 ± 0.40 c | 17.56 ± 2.15 b | 4.01 ± 0.61 c | 23.42 ± 2.04 a |

| M-C/N | 69.78 ± 2.18 a | 17.14 ± 0.77 b | 9.39 ± 1.94 c | 5.13 ± 0.43 d | 3.52 ± 0.22 d |

| M-C/P | 81.57 ± 5.86 a | 69.68 ± 9.91 a | 5.03 ± 0.82 b | 8.29 ± 1.67 b | 3.10 ± 0.37 b |

| M-N/P | 1.16 ± 0.05 b | 4.13 ± 0.69 a | 0.57 ± 0.09 b | 1.66 ± 0.37 b | 0.87 ± 0.07 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, C.; Zou, S.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, X. Forest-to-Tea Conversion Intensifies Microbial Phosphorus Limitation and Enhances Oxidative Enzyme Pathways. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2615. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112615

Huang C, Zou S, Chen Y, Jiang X. Forest-to-Tea Conversion Intensifies Microbial Phosphorus Limitation and Enhances Oxidative Enzyme Pathways. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2615. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112615

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Chumin, Shun Zou, Yang Chen, and Xianjun Jiang. 2025. "Forest-to-Tea Conversion Intensifies Microbial Phosphorus Limitation and Enhances Oxidative Enzyme Pathways" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2615. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112615

APA StyleHuang, C., Zou, S., Chen, Y., & Jiang, X. (2025). Forest-to-Tea Conversion Intensifies Microbial Phosphorus Limitation and Enhances Oxidative Enzyme Pathways. Agronomy, 15(11), 2615. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112615