Study on the Difference of Cadmium Extraction from Sedum alfredii and Sedum plumbizincicola Based on Population Characteristics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Experimental Site

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sampling and Processing

2.3.1. Plant Sampling and Processing

2.3.2. Soil Sampling and Processing

2.3.3. Phenological Period Observation

2.3.4. Yield Measurement

2.4. RNA Sequencing Analysis

2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

- (1)

- Cd uptake proportion of each organ (%) = [organ dry biomass (g) × Cd content of the organ (mg kg−1)]/[shoots dry biomass (g) × Cd content of shoots (mg kg−1)] × 100%.

- (2)

- Theoretical Cd uptake (g Ha−1) = shoots dry biomass (g plant−1) × Cd content of shoots (mg kg−1) × 300,000 (plants Ha−1)/106.

- (3)

- Measured Cd uptake (g Ha−1) = measured yield (kg Ha−1) × Cd content of shoots (mg kg−1)/106.

- (4)

- Theoretical yield (kg Ha−1) = shoots dry biomass (g plant−1) × 300,000 (plants Ha−1)/103.

- (5)

- Measured yield (kg Ha−1) = shoots dry biomass per unit area (kg m−2) × 10,000.

- (6)

- Logistic Equation:

3. Results

3.1. Phenophase

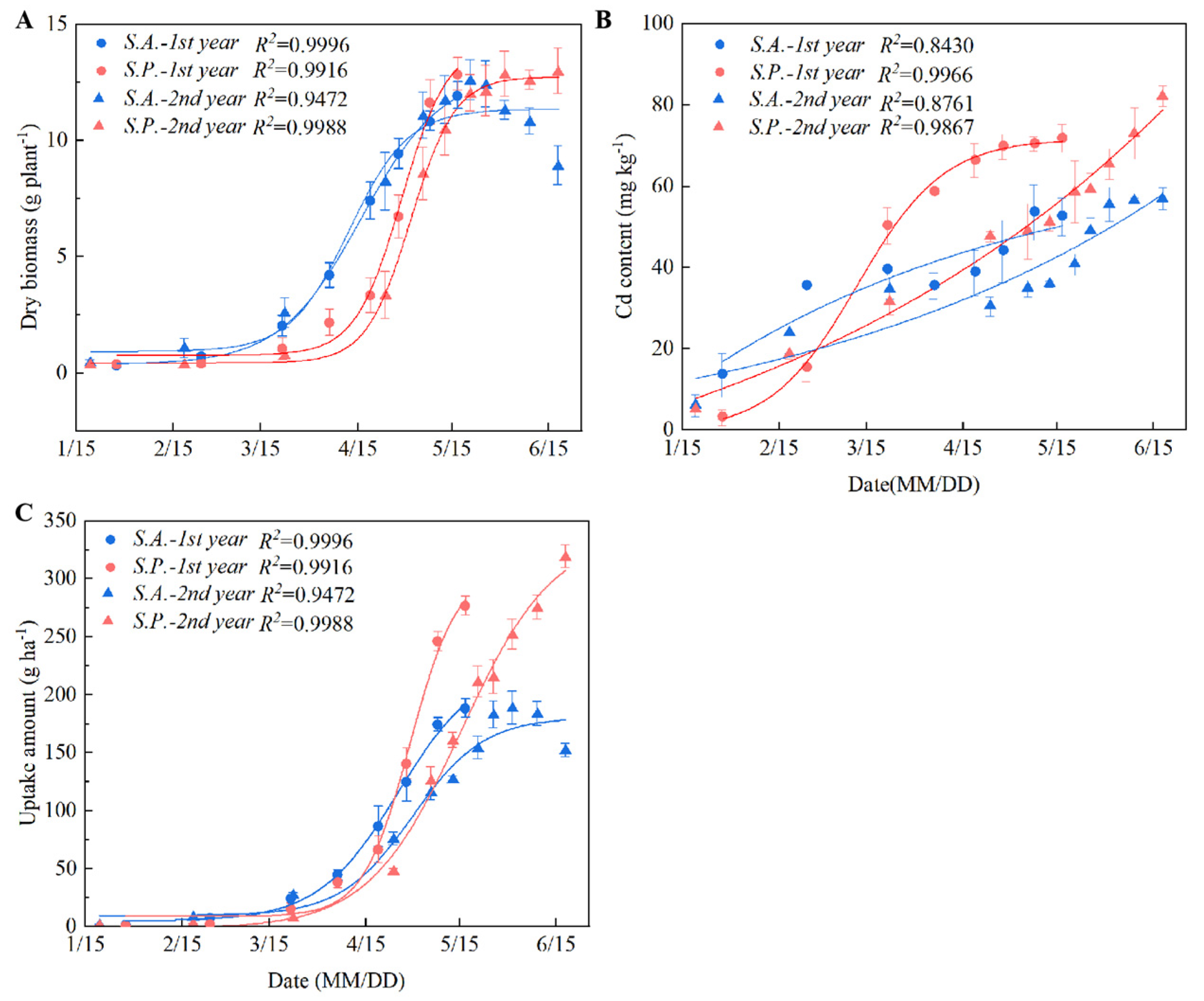

3.2. Dynamics of Dry Biomass, Cd Content, and Uptake Amount

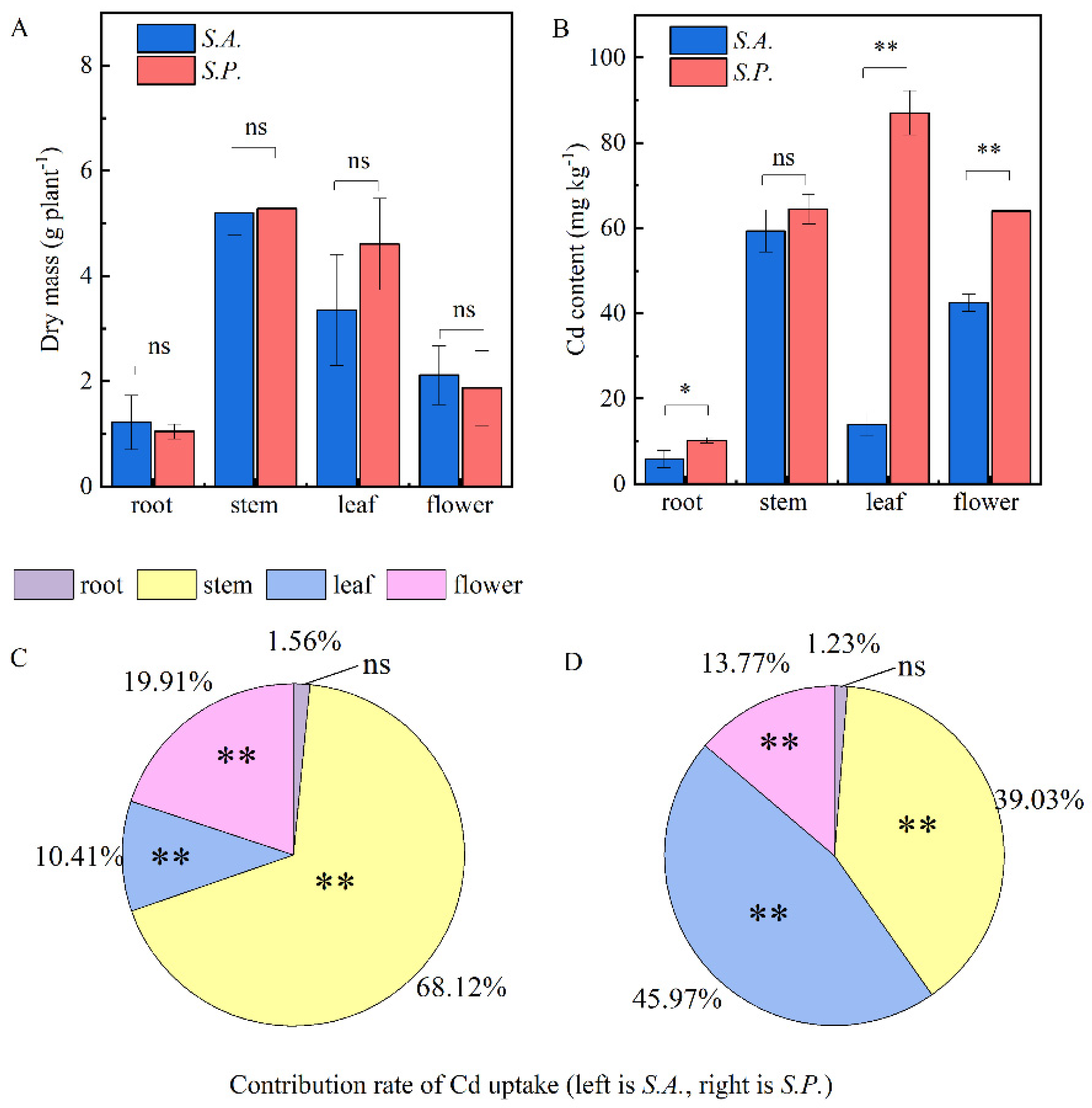

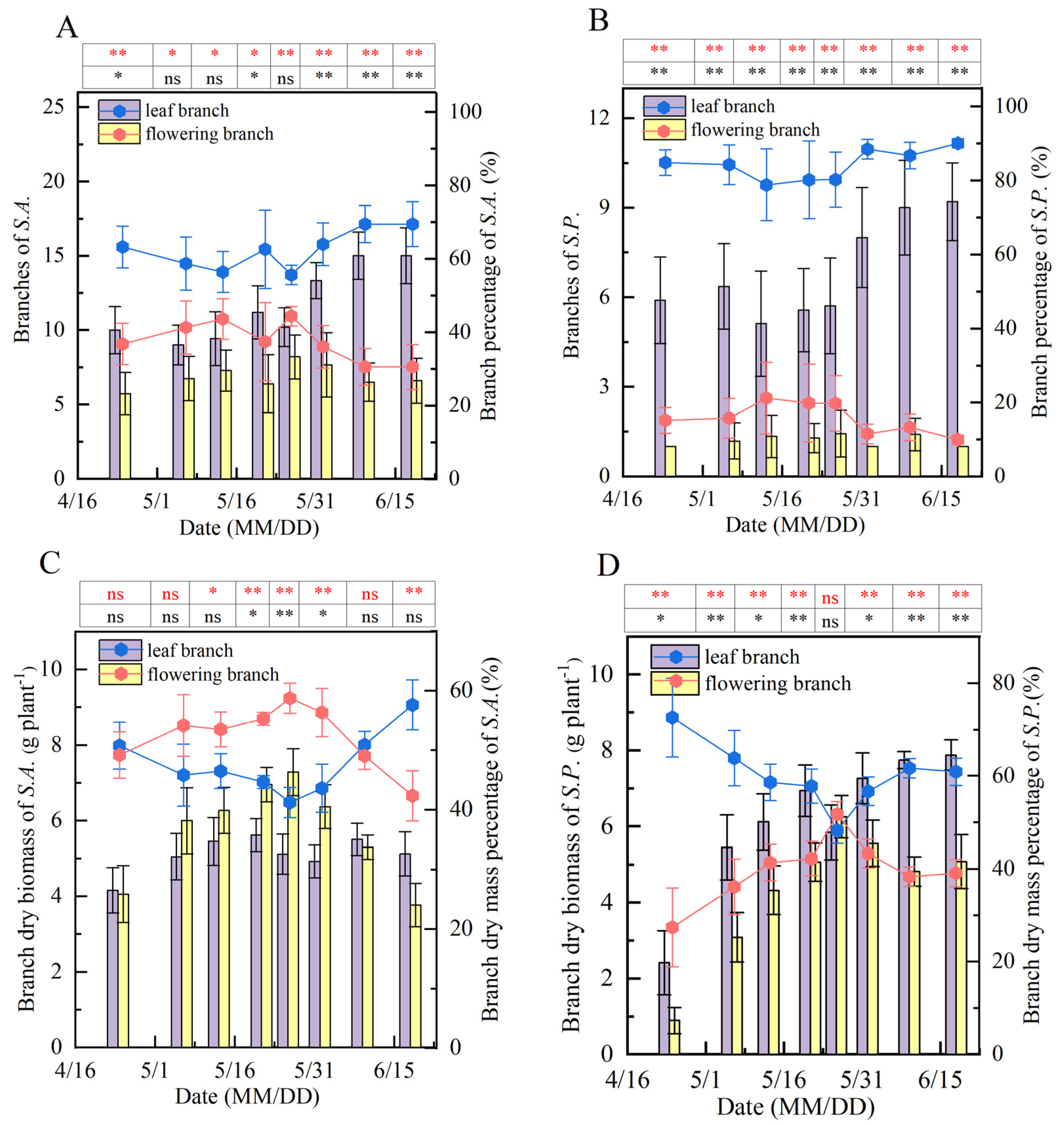

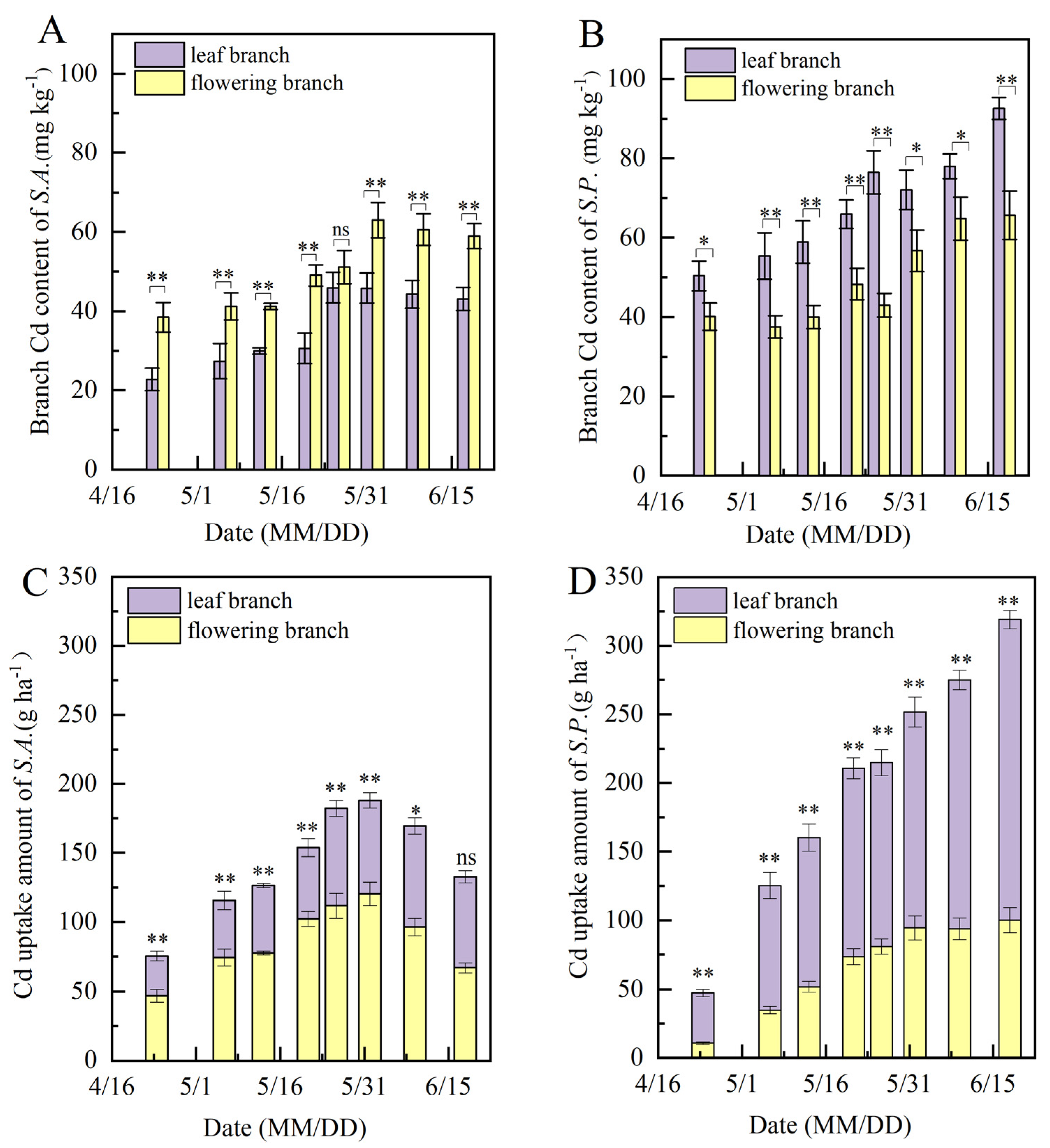

3.3. Agricultural Traits and the Distribution Pattern of Cd in Sedum

3.4. Plant Yield, Cd Uptake Efficiency, and Bioconcentration Factors (BCF)

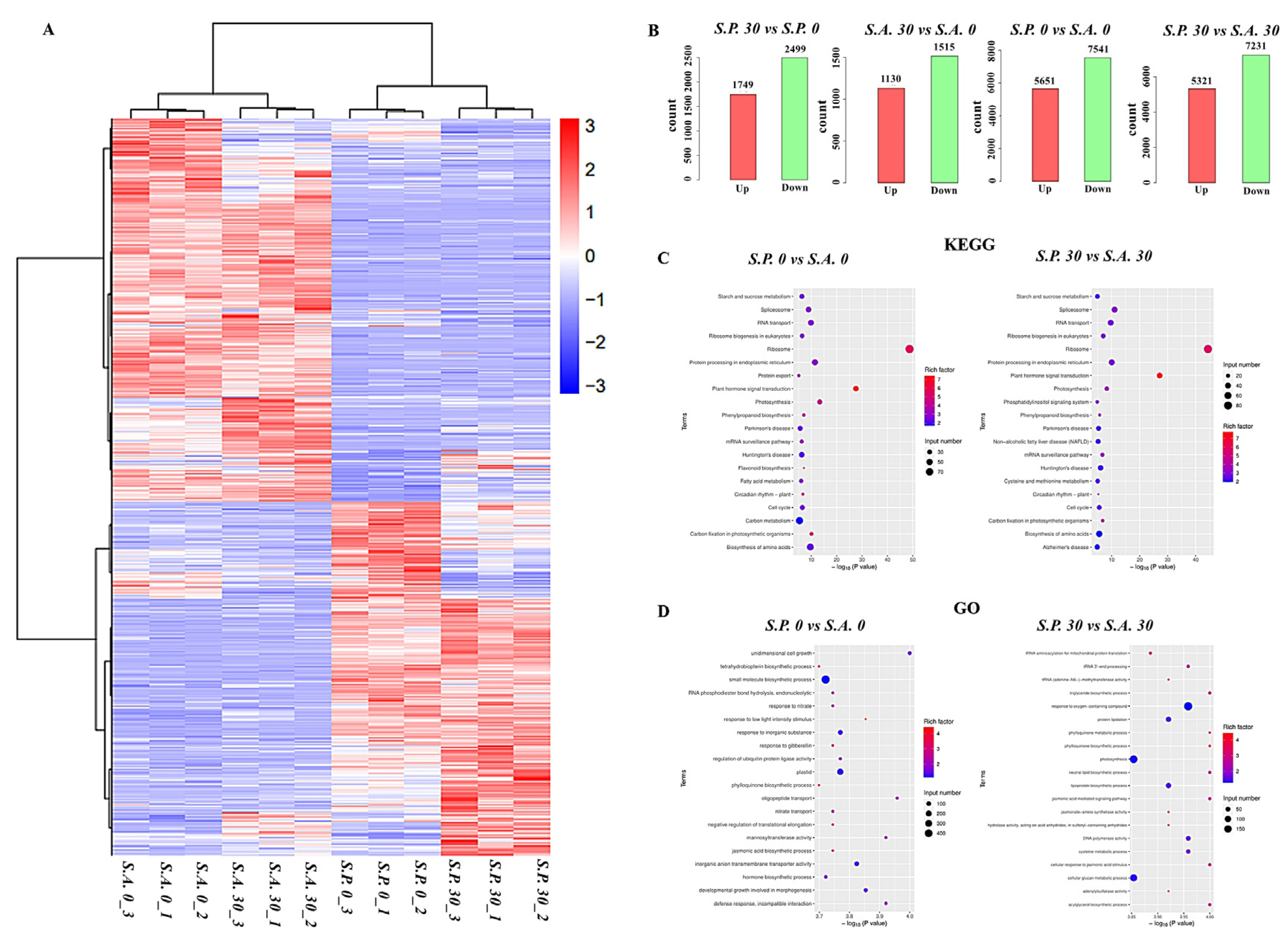

3.5. Transcriptomes of S.A. and S.P. Differentially Respond to Cd Stress

4. Discussion

4.1. Phenological and Agronomic Responses

4.2. Cd Uptake and Organ Distribution

4.3. Molecular Mechanisms

4.4. Practical Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cd | Cadmium |

| S.A. | Sedum alfredii |

| S.P. | Sedum plumbizincicola |

| BCF | Bioconcentration factors |

References

- Xin, J. Enhancing soil health to minimize cadmium accumulation in agro-products: The role of microorganisms, organic matter, and nutrients. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 348, 123890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Li, H. Cost-Effectiveness analysis for soil heavy metal contamination treatments. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2018, 229, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Dong, M.; Mao, P.; Zhuang, P.; Paz-Ferreiro, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Hu, X.; Netherway, P.; Li, Z. Evaluation of phytoremediation potential of five Cd (hyper) accumulators in two Cd contaminated soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 721, 137581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Xin, J.; Dai, H.; Zhou, W. Effects of Interaction between cadmium (Cd) and selenium (Se) on grain yield and Cd and Se accumulation in a hybrid rice (Oryza sativa) system. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 9537–9546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Jiang, P.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Liu, X.; Cao, C.; Luo, G.; Ou, L. Deciphering the distinct associations of rhizospheric and endospheric microbiomes with capsicumplant pathological status. Microb. Ecol. 2025, 88, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Tu, C.; Zhou, J.; Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, L.; Newman, L.A.; Luo, Y. Cadmium phytoextraction by Sedum alfredii and Sedum plumbizincicola: Mechanisms, challenges and prospects. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2025, 27, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yi, H.; Gong, J. Isolation and characterization of cadmium tolerant gene SpMT2 in the hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola. Chin. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 36, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.-S.; Din, G.; Meng, S.; Yi, H.-Y.; Gong, J.-M. Enhanced metal tolerance correlates with heterotypic variation in SpMTL, a metallothionein-like protein from the hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 1368–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhou, L.; Yang, F.; Liang, S.; Zhao, Q. Phytoremediation Effects and Contrast of Sedum alfredii and Sedum plumbizincicola on Cd/Zn Contaminated Soil. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2019, 28, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhu, D.; Wu, L.; Xing, W.; Luo, Y.; Christie, P. Repeated phytoextraction of metal contaminated calcareous soil by hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2018, 20, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, T.; Zhou, S.; Wu, L.; Luo, Y.; Christie, P. Phytoextraction potential of soils highly polluted with cadmium using the cadmium/zinc hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2019, 21, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Tan, C.; Cao, X.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, S.; Peng, X.; Deng, Y.; Sun, L. Effect of three organic acids on the remediation efficiency of Sedum plumbizincicola and soil microbial quantity. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 34, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Rao, S.; Fang, J.; Lv, Y.; Zhao, A.; Ye, Z.; Fu, W. Organic materials could improve the phytoremediation efficiency of soil potentially hazardous metal by Sedum alfredii Hance. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 91, 1529–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Zheng, F.; He, B.; Gu, M. Exogenous abscisic acid (ABA) promotes cadmium (Cd) accumulation in Sedum alfredii Hance by regulating the expression of Cd stress response genes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 8719–8731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, Q.; Chen, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, M.; Munir, M.A.M.; Feng, Y.; He, Z.; Yang, X. Roles of exogenous plant growth regulators on phytoextraction of Cd/Pb/Zn by Sedum alfredii Hance in contaminated soils. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 293, 118510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yan, K.; He, Y.; Zhan, F.; Zu, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, B. Effect of shading on the accumulation characteristics of Cd, Pb and Zn of Sedum plumbizincicola. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2021, 30, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.-Y.; He, J.-Q.; Qin, H.; Liu, D.-H.; Deng, L.; Chang, H.-W.; Gui, J.; Li, Z.; Zhou, T. Effect of film mulching on plant growth and cadmium uptake by Sedum plumbizincicola. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2019, 38, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-H.; Zu, Y.-Q.; Zhan, F.-D.; Li, B.; Li, Y. Effects of passivators on the growth and cadmium accumulation of intercropped maize and Sedum plumbizincicola. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2019, 38, 2103–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.-J.; Liu, H.-Y.; Sun, X.; Zhu, R.-F.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Wu, L.-H. Effects of intercropping on growth and Cd/Zn Uptake by Sedum plumbizincicola and Excoecaria cochinchinensis. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2021, 40, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wang, P.; Tang, C.; Liu, Z. Remediation and micro-Ecological regulation of cadmium and arsenic co-contaminated soils by rotation of high-biomass crops and Sedum alfredii Hance: A field study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Cao, X.; Jiang, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, G.; Song, J.; Afsheen, Z.; Yang, X.E. Study on the remediation patterns of rotation or intercropping between hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii and oil crops in cadmium and lead co-contaminated agricultural soils. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Agric. Life Sci.) 2021, 47, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; He, A.; Hu, Z.; Bai, L.; Zhao, S.; Nie, Y.; Chen, J. Study of quality grading standards on Sedum plumbizincicola seedlings for phytoremediation. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Agric. Life Sci.) 2022, 48, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.D.; Wakefield, M.J.; Smyth, G.K.; Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: Accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Cai, T.; Olyarchuk, J.G.; Wei, L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3787–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Araki, M.; Goto, S.; Hattori, M.; Hirakawa, M.; Itoh, M.; Katayama, T.; Kawashima, S.; Okuda, S.; Tokimatsu, T.; et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, D480–D484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, A.D.; Keenan, T.F.; Migliavacca, M.; Ryu, Y.; Sonnentag, O.; Toomey, M. Climate change, phenology, and phenological control of vegetation feedbacks to the climate system. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 169, 156–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, J.; Zhai, L.; Ge, L.; Hao, S.; Shi, L.; Lian, C.; Chen, C.; Shen, Z.; Chen, Y. A meta-analysis about the accumulation of heavy metals uptake by Sedum alfredii and Sedum plumbizincicola in contaminated soil. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2022, 24, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Tian, S.; Foyer, C.H.; Hou, D.; Wang, H.; Zhou, W.; Liu, T.; Ge, J.; Lu, L.; Lin, X. Efficient phloem transport significantly remobilizes cadmium from old to young organs in a hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 365, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Wang, Y.; Przybyłowicz, W.J.; Li, Z.; Barnabas, A.; Wu, L.; Luo, Y.; Mesjasz-Przybyłowicz, J. Elemental distribution by cryo-micro-PIXE in the zinc and cadmium hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola grown naturally. Plant Soil 2015, 388, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Bai, N.; Ma, M.; Peng, J. SpHIPP45 gene from Sedum plumbizincicola specically mediates cadmium tolerance. Plant Physiol. J. 2022, 58, 1346–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.-S.; Wang, Y.-J.; Ding, G.; Ma, H.-L.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Gong, J.-M. A pivotal role of cell wall in cadmium accumulation in the crassulaceae hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhong, J.; He, A.G.; Ji, X.H.; Hu, Z.X.; Dai, Y.J. First report of Sedum plumbizincicola wilt caused by Plectosphaerella cucumerina in China. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Chen, J.; Mao, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, W.; Peng, J.; Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Guo, P.; Zhang, M.; et al. Lipid-mediated photoprotection confers strong light resilience in hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii. Plant Sci. 2025, 360, 112688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | pH | Total Cadmium mg kg−1 | Effective Cadmium mg kg−1 | Total Nitrogen g kg−1 | Total Phosphorus g kg−1 | Total Potassium g kg−1 | Alkaline Nitrogen mg kg−1 | Available Phosphorus mg kg−1 | Available Potassium mg kg−1 | Organic Matter g kg−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st year | 5.0 | 0.84 | 0.42 | 2.23 | 0.80 | 35.20 | 184.25 | 23.13 | 120.25 | 38.53 |

| 2nd year | 4.9 | 0.75 | 0.38 | 2.31 | 0.70 | 31.13 | 156.67 | 30.53 | 102.67 | 39.37 |

| Sedum | Seedling Stage | Vigorous Growing Stage | Budding Stage | Flowering Stage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Flowering Stage | Full Flowering Stage | Terminal Flowering Stage | ||||

| S.A. | Transplanting date-20 February | 20 February–15 May | 5 April–20 April | 21 April–25 April | 26 April–6 May | 6 May–25 May |

| S.P. | Transplanting date-20 March | 5 April–20 May | 25 April–10 May | 11 May–14 May | 15 May–25 May | 26 May–15 June |

| Year | Sedum | Cd Content (mg kg−1) | BCF | Yield (kg ha−1) | Uptake Amount (g ha−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Value | Measured Value | Theoretical Value | Measured Value | ||||

| 2020–2021 | S.A. | 52.59 b | 62.36 b | 3573.00 b | 3308.94 a | 187.89 b | 174.00 a |

| S.P. | 71.82 a | 85.17 a | 3845.50 a | 1917.54 b | 276.17 a | 137.71 b | |

| 2021–2022 | S.A. | 49.01 b | 66.41 b | 3719.46 a | 3541.46 a | 182.30 b | 173.58 a |

| S.P. | 82.04 a | 109.39 a | 3887.59 a | 2436.65 b | 318.95 a | 199.91 a | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Dai, Y.; Deng, Y.; Chen, X.; He, A.; Jiang, H.; Duan, M. Study on the Difference of Cadmium Extraction from Sedum alfredii and Sedum plumbizincicola Based on Population Characteristics. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2595. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112595

Chen J, Dai Y, Deng Y, Chen X, He A, Jiang H, Duan M. Study on the Difference of Cadmium Extraction from Sedum alfredii and Sedum plumbizincicola Based on Population Characteristics. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2595. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112595

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jin, Yanjiao Dai, Yan Deng, Xi Chen, Aiguo He, Huidan Jiang, and Meijuan Duan. 2025. "Study on the Difference of Cadmium Extraction from Sedum alfredii and Sedum plumbizincicola Based on Population Characteristics" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2595. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112595

APA StyleChen, J., Dai, Y., Deng, Y., Chen, X., He, A., Jiang, H., & Duan, M. (2025). Study on the Difference of Cadmium Extraction from Sedum alfredii and Sedum plumbizincicola Based on Population Characteristics. Agronomy, 15(11), 2595. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112595