Multi-Scale Multi-Branch Convolutional Neural Network on Google Earth Engine for Root-Zone Soil Salinity Retrieval in Arid Agricultural Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

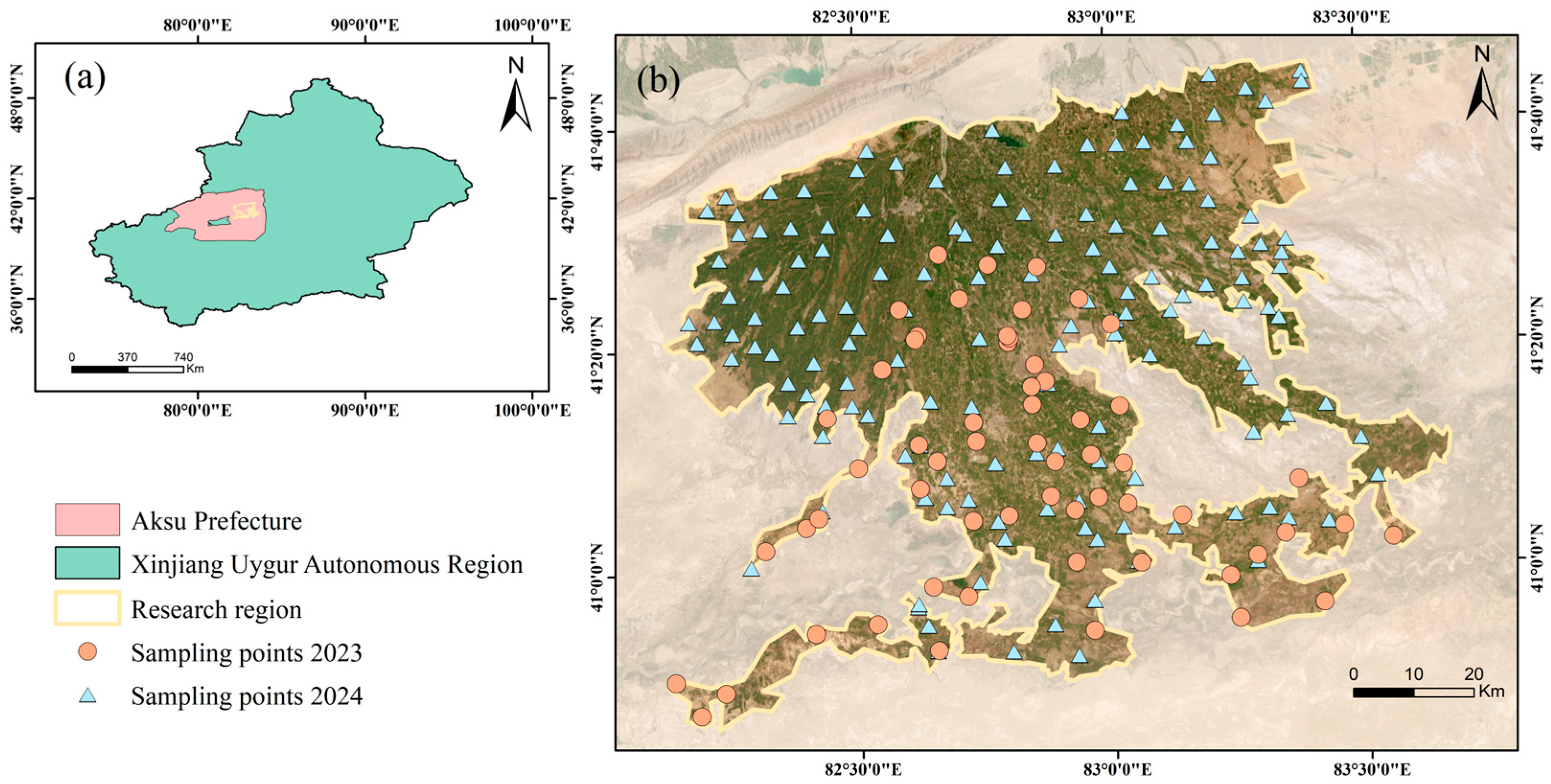

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Dataset

2.2.1. Ground Measurement Dataset

2.2.2. Remote Sensing Imagery

2.2.3. Environmental Covariates

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Feature Selection Method

2.3.2. RF Model

2.3.3. CNN Model

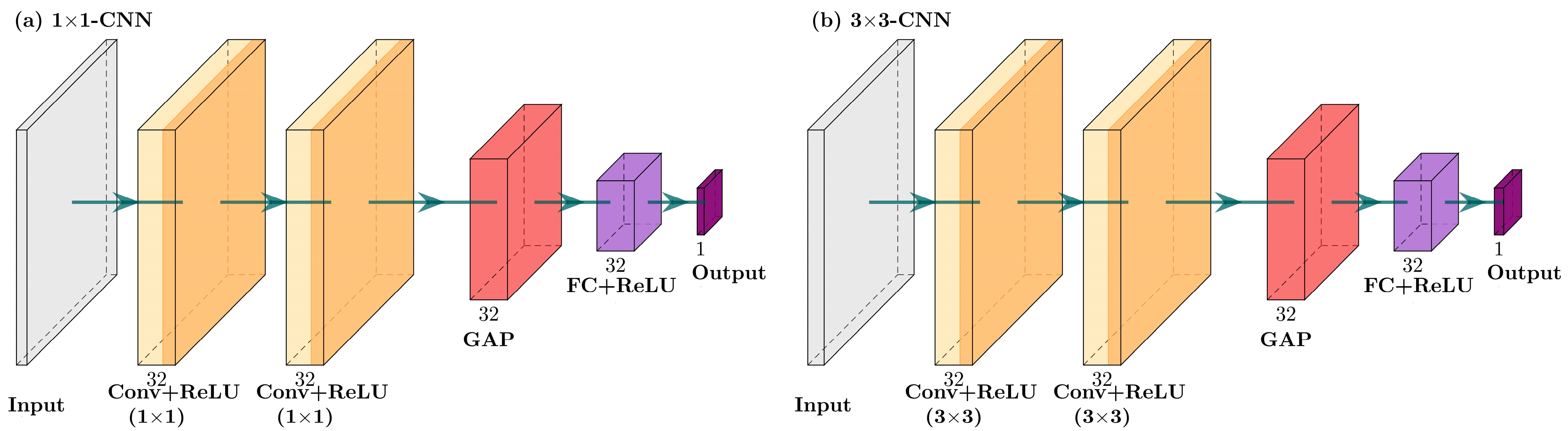

Single-Scale Convolutional Neural Network

Multi-Scale Multi-Branch Convolutional Neural Network

2.3.4. Model Accuracy Evaluation

2.3.5. Platform Selection

3. Results

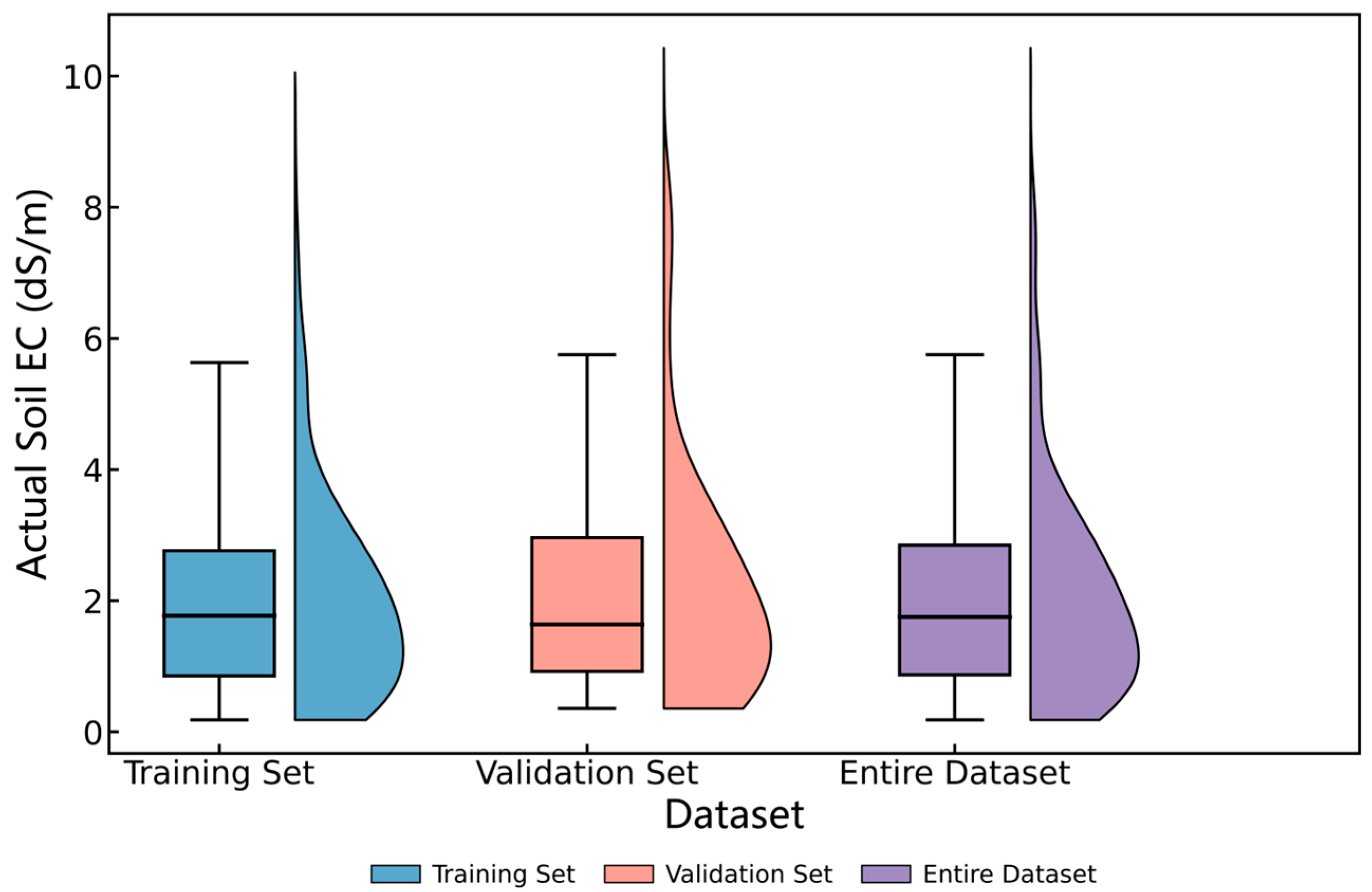

3.1. Analysis of Field Measurement Data

3.2. Selection of Model Input Features

3.3. Comparison of Model Stability

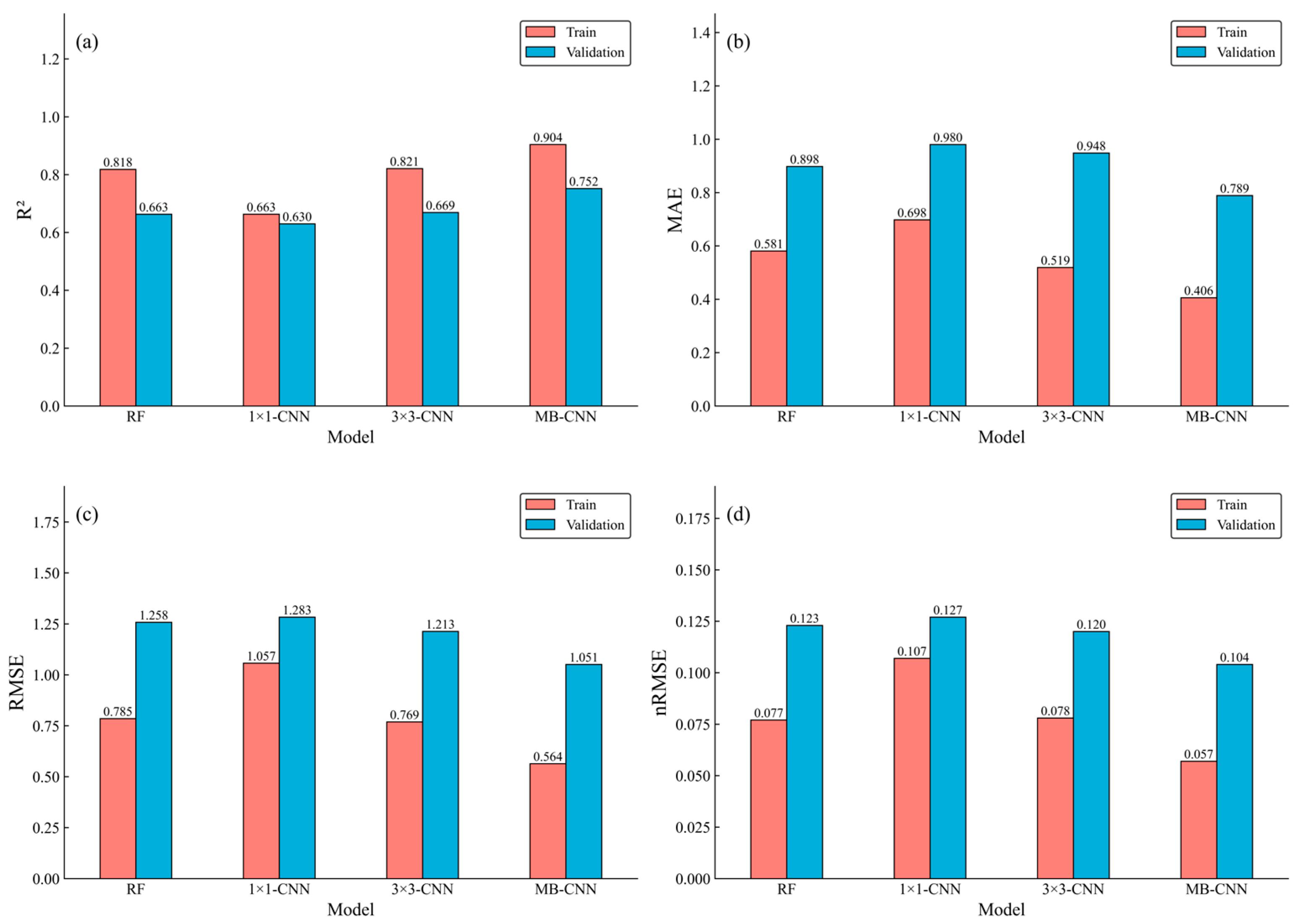

3.4. Comparison of Model Accuracy Between Single-Scale CNN and the RF Model

3.5. Comparison Between Multi-Scale and Single-Scale CNN Models

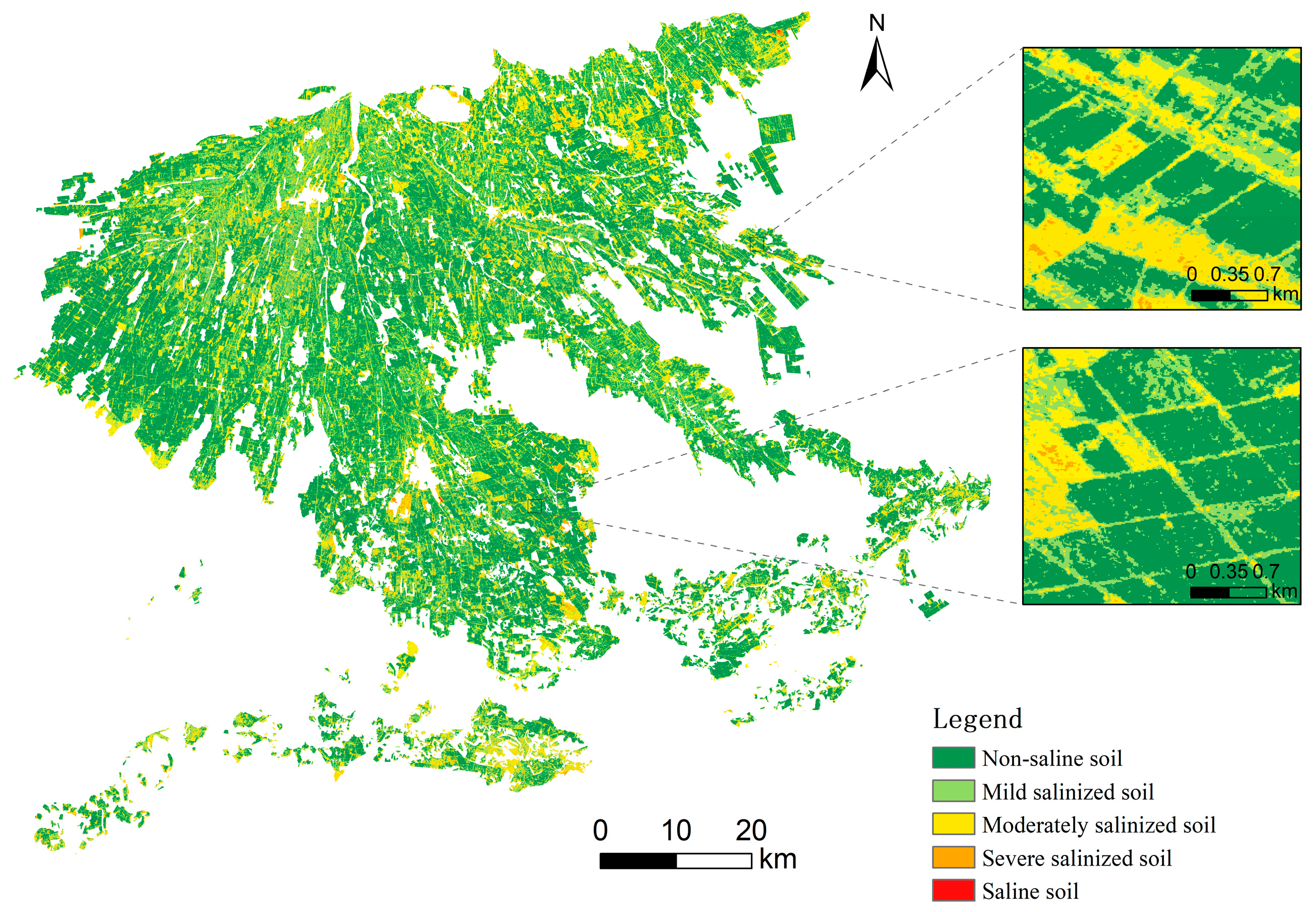

3.6. MB-CNN-Based Mapping of Soil EC in the Study Area

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Environmental Variables on Soil Salinity

4.2. Influence of Different Models on Soil Salinity Inversion

4.3. Research Limitations and Future Directions

4.4. Major Contributions and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shokri, N.; Guan, D.; Or, D. Multi-scale soil salinization dynamics from global to pore scales. Rev. Geophys. 2024, 62, e2023RG000804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, D.L. Climate change impacts on soil salinity in agricultural areas. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2020, 71, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Ma, X. Spatial heterogeneity response of soil salinization in arid oasis agricultural areas. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15160. [Google Scholar]

- Hopmans, J.W.; Qureshi, A.S.; Kisekka, I.; Munns, R.; Grattan, S.R.; Rengasamy, P.; Ben-Gal, A.; Assouline, S.; Javaux, M.; Minhas, P.S.; et al. Critical knowledge gaps and research priorities in global soil salinity. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2021; Volume 169, pp. 1–191. [Google Scholar]

- Sahbeni, G.; Ngabire, M.; Musyimi, P.K.; Székely, B. Challenges and Opportunities in Remote Sensing for Soil Salinization Mapping and Monitoring: A Review. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Soil salinization management for sustainable development: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 277, 111383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Han, L.; Liu, L.; Bai, C.; Ao, J.; Hu, H.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Guo, X.; Wei, Y. Advancements and perspective in the quantitative assessment of soil salinity utilizing remote sensing and machine learning algorithms: A review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleymanov, A.; Gabbasova, I.; Komissarov, M.; Suleymanov, R.; Garipov, T.; Tuktarova, I.; Belan, L. Random forest modeling of soil properties in saline semi-arid areas. Agriculture 2023, 13, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Ding, J.; Teng, D.; Wang, J.; Huo, T.; Jin, X.; Wang, J.; He, B.; Han, L. Updated soil salinity with fine spatial resolution and high accuracy: The synergy of Sentinel-2 MSI, environmental covariates and hybrid machine learning approaches. Catena 2022, 212, 106054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, T.; Feng, W.; Han, L.; Gao, R.; Wang, F.; Ma, S.; Han, D.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, S.; et al. Integrating multi-temporal Sentinel-1/2 vegetation signatures with machine learning for enhanced soil salinity mapping accuracy in coastal irrigation zones: A case study of the Yellow River Delta. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.X.; Tuia, D.; Mou, L.; Xia, G.S.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Fraundorfer, F. Deep learning in remote sensing: A comprehensive review and list of resources. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2017, 5, 8–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Garajeh, M.K.; Blaschke, T.; Makki, M. A deep learning convolutional neural network algorithm for detecting saline flow sources and mapping the environmental impacts of the Urmia Lake drought in Iran. Catena 2021, 207, 105585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Guo, B.; Zhang, R. The optimal estimation model for soil salinization based on the FOD-CNN spectral index. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Ning, S.; Sheng, J.; Su, T. Spatial heterogeneity response of soil salinization to cotton field expansion in arid regions using deep learning models. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12345. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, S.; Fang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X. Spatial–temporal differentiation and pattern optimization of landscape ecological security in the Ugan–Kuqa River Oasis. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 5473–5482. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, L.; Sun, R.; Wang, J.; Chen, Q. Retrieval of soil salinity from Sentinel-1 dual-polarized SAR data based on deep neural network regression. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2020, 19, 4006905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhu, P.; Yang, R.; Sun, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. Ecosystem stability in the Ugan–Kuqa River Basin, Xinjiang, China: Investigation of spatial and temporal dynamics and driving forces. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Chen, S.; Huang, J.; Frappart, F.; Taghizadeh, R.; Zhang, X.; Wigneron, J.-P.; Xue, J.; Xiao, Y.; Peng, J.; et al. Global soil salinity estimation at 10 m using multi-source remote sensing. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 4, 0130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, J.; Yu, D.; Teng, D.; He, B.; Chen, X.; Ge, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. Machine learning-based detection of soil salinity in an arid desert region, Northwest China: A comparison between Landsat-8 OLI and Sentinel-2 MSI. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 136092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, D.; Chen, H.; Liu, P. Integrating both driving and response environmental variables to enhance soil salinity inversion. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Rusuli, Y.; Amuti, T.; He, Q. Quantitative assessment of soil salinity using multi-source remote sensing data based on the support vector machine and artificial neural network. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 40, 284–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N. Use of a green channel in remote sensing of global vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Biswas, A.; Jiang, Q.; Zhao, R.; Hu, J.; Hu, B.; Shi, Z. Estimating soil salinity from remote sensing and terrain data in southern Xinjiang Province, China. Geoderma 2019, 337, 1309–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, D.J.; Baret, F.; Guyot, G. A ratio vegetation index adjusted for soil brightness. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1990, 11, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.M.; Rastoskuev, V.V.; Sato, Y.; Shiozawa, S. Assessment of hydrosaline land degradation by using a simple approach of remote sensing indicators. Agric. Water Manag. 2005, 77, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douaoui, A.E.K.; Nicolas, H.; Walter, C. Detecting salinity hazards within a semiarid context by means of combining soil and remote-sensing data. Geoderma 2006, 134, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannari, A.; Guedon, A.M.; El-Harti, A.; Cherkaoui, F.Z.; El-Ghmari, A. Characterization of slightly and moderately saline and sodic soils in irrigated agricultural land using simulated data of advanced land imager (EO-1) sensor. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2008, 39, 2795–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allbed, A.; Kumar, L.; Aldakheel, Y.Y. Assessing soil salinity using soil salinity and vegetation indices derived from IKONOS high-spatial resolution imageries: Applications in a date palm dominated region. Geoderma 2014, 230–231, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.L. Narrowband to broadband conversions of land surface albedo: I. Algorithms. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 76, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Dong, T.; Wang, J.; Fan, Y.; Wu, H.; Geng, Q.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Z. The applicability of remote sensing models of soil salinization based on feature space. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmemet, I.; Sagan, V.; Ding, J.-L.; Halik, U.; Abliz, A.; Yakup, Z. A WFS-SVM model for soil salinity mapping in Keriya Oasis, northwestern China using polarimetric decomposition and fully PolSAR data. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzi, R.; Goze, S.; Le Toan, T.; Lopes, A.; Mougin, E. Polarimetric discriminators for SAR images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2002, 30, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, K.; Wang, M. Downscaling Groundwater Storage Data in China to a 1-km Resolution Using Machine Learning Methods. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeys, Y.; Inza, I.; Larrañaga, P. A review of feature selection techniques in bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2507–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohavi, R.; John, G.H. Wrappers for feature subset selection. Artif. Intell. 1997, 97, 273–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, G.; Sahin, F. A survey on feature selection methods. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2014, 40, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.A.; Metwaly, M.M.; Metwalli, M.R.; AbdelRahman, M.A.; Badreldin, N. Integrating active and passive remote sensing data for mapping soil salinity using machine learning and feature selection approaches in arid regions. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, C.; Chen, H.; Liu, P. Soil salinity inversion by combining multi-temporal Sentinel-2 images near the sampling period in coastal salinized farmland. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1533419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghadosi, M.M.; Hasanlou, M.; Eftekhari, K. Retrieval of soil salinity from Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 40, 510–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.L.; Jia, K.L.; Li, X.Y.; Zhang, M.L.; Hu, Z.W. Inversion of soil salt content by combining optical and microwave remote sensing in cultivated land. Arid Land Geogr. 2024, 47, 433–444. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.D.; Wu, H.Y.; Ju, B.; Shi, X.; Zhang, G.L. Pedoclimatic zone-based three-dimensional soil organic carbon mapping in China. Geoderma 2020, 363, 114145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Du, B. Deep learning for remote sensing data: A technical tutorial on the state of the art. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2016, 4, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulczyjew, Ł.; Kawulok, M.; Longépé, N.; Le Saux, B.; Nalepa, J. A multibranch convolutional neural network for hyperspectral unmixing. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 6011105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legates, D.R.; McCabe Jr, G.J. Evaluating the use of “goodness-of-fit” measures in hydrologic and hydroclimatic model validation. Water Resour. Res. 1999, 35, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudiero, E.; Skaggs, T.H.; Corwin, D.L. Regional-scale soil salinity assessment using Landsat ETM+ canopy reflectance. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 169, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metternicht, G.I.; Zinck, J.A. Remote sensing of soil salinity: Potentials and constraints. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 85, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Cui, X.; Han, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L. Improved soil salinity estimation in arid regions: Leveraging bare soil periods and environmental factors. iScience 2025, 28, 113020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahbeni, G.; Szatmári, J.; Kovács, F. Soil salinity mapping using Landsat 8 OLI data and regression modeling in the Hungarian Great Plain. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, W.; Niu, Z.; Huang, H. Land salinization dynamics based on feature space combinations from Landsat image in Tongyu County, Northeast China. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 3, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Xue, J.; Peng, J.; Biswas, A.; He, Y.; Shi, Z. Integrating remote sensing and landscape characteristics to estimate soil salinity using machine learning methods: A case study from Southern Xinjiang, China. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, F.; Hong, B.; Yang, S. Revealing spatial variability of groundwater level in typical ecosystems of the Tarim Basin through ensemble algorithms and limited observations. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, N.; Zribi, M.; Loumagne, C.; Ansart, P.; El Hajj, M. Estimating soil moisture with C-band radar data: Application to ERS-SAR data over wheat fields. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 96, 443–451. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Kayem, K.; Hao, Y.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, C.; Peng, J.; Liu, W.; Zuo, Q.; Ji, W.; Li, B. Mapping the levels of soil salination and alkalization by integrating machine learning methods and soil-forming factors. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garajeh, M.K.; Malakyar, F.; Weng, Q.; Feizizadeh, B.; Blaschke, T.; Lakes, T. An automated deep learning convolutional neural network algorithm applied for soil salinity distribution mapping in Lake Urmia, Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 778, 146253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazi, E.H.; Samak, A.A.; Yang, L.; Huang, R.; Huang, J. Prediction of soil moisture content from Sentinel-2 images using convolutional neural network (CNN). Agronomy 2023, 13, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wang, J.; Qi, Z. Maize classification in arid regions via spatiotemporal feature optimization and multi-source remote sensing integration. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature Types | Description | Formula | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation indices | Normalized differential vegetation index | [22] | |

| Enhanced vegetation index | [23] | ||

| Normalized difference water index | [24] | ||

| Soil-adjusted vegetation index | [25] | ||

| Enhanced normalized differential vegetation index | [22] | ||

| Differential vegetation index | [26] | ||

| Salinity indices | Normalized difference salinity index | [27] | |

| Salinity index | [21] | ||

| Salinity index 1 | [28] | ||

| Salinity index 2 | [28] | ||

| Salinity index 3 | [28] | ||

| Salinity index 4 | [29] | ||

| Salinity index I | [28] | ||

| Salinity index II | [28] | ||

| Salinity index III | [28] | ||

| Salinity index V | [28] | ||

| Salinity index VI | [28] | ||

| Salinity index VII | [30] | ||

| Salinity index VIII | [29] | ||

| Salinity index IX | [29] | ||

| Salinity index | [31] | ||

| Soil indices | Brightness index | [28] | |

| Albedo | 0.36B + 0.13R + 0.37NIR + 0.09SWIR1 + 0.07SWIR2 − 0.002 | [32] | |

| Feature space | SI-Albedo | [33] | |

| Original backscatter feature | Normalized backscatter coefficient | - | |

| Radar index | Radar vegetation index | [34] | |

| Square difference index | [19] | ||

| Ratio of backscatter coefficient | [19] | ||

| Total scattering power | [35] | ||

| Normal difference index | [19] |

| Feature Type | Covariate | Spatial Resolution | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terrain data | DEM | 30 m | NASA JPL, SRTM V3 (SRTM Plus) Digital Elevation Model |

| Slope | 30 m | ||

| Aspect | 30 m | ||

| Plan curvature | 30 m | ||

| Profile curvature | 30 m | ||

| Terrain ruggedness index (TRI) | 30 m | ||

| Topographic surface convexity (TSC) | 30 m | ||

| Climate data | Land Surface temperature (LST) | 1000 m | MOD11A1 Version 6.1 (MODIS, NASA LP DAAC) |

| Evapotranspiration (ET) | 500 m | MOD16A2 Version 6.1 (MODIS, NASA LP DAAC) | |

| Soil texture data | Clay | 250 m | SoilGrids (ISRIC–World Soil Information) |

| Sand | 250 m | ||

| Silt | 250 m | ||

| Groundwater | Groundwater table depth (WTD) | 1000 m | [36] |

| Category | Parameter | Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Model structure | Convolutional layers | Two layers per branch (32 filters each) |

| Kernel size | 1 × 1 (1 × 1-CNN), 3 × 3 (3 × 3-CNN), dual 1 × 1 & 3 × 3 (MB-CNN) | |

| Pooling layer | Adaptive average pooling | |

| Fully connected layers | 32 → 1 | |

| Training configuration | Loss function | Smooth L1 loss |

| Optimizer | AdamW | |

| Learning rate | 0.01 | |

| Weight decay | 1 × 10−4 | |

| Batch size | 16 | |

| Epochs | 200 (with early stopping, patience = 10) | |

| Implementation | Framework | PyTorch 2.4.1 |

| Rank | RF | 1 × 1-CNN | 3 × 3-CNN | MB-CNN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NDWI | SI4 | NDVI | NDVI |

| 2 | SDI | S9 | LST | Clay |

| 3 | ENDVI | LST | BI | WTD |

| 4 | DEM | SPAN | SI4 | TSC |

| 5 | LST | NDVI | S2 | DVI |

| 6 | Clay | Plan curvature | S3 | NDWI |

| 7 | SI-Albedo | SI | DEM | TRI |

| 8 | S9 | Albedo | SI-T | ENDVI |

| 9 | SI4 | Clay | SI3 | VV |

| 10 | RVI | DEM | ENDVI | SDI |

| 11 | SI2 | Slope | SI-Albedo | Albedo |

| 12 | S3 | DVI | EVI | SI2 |

| 13 | S2 | BI | TRI | SI-T |

| 14 | S1 | VH | SI | Slope |

| 15 | BI | TRI | S1 | SPAN |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, W.; Wang, X.; Ning, S.; Zhou, W.; Gao, S.; Li, C.; Huang, Y.; Dong, L.; Sheng, J. Multi-Scale Multi-Branch Convolutional Neural Network on Google Earth Engine for Root-Zone Soil Salinity Retrieval in Arid Agricultural Areas. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2534. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112534

Dong W, Wang X, Ning S, Zhou W, Gao S, Li C, Huang Y, Dong L, Sheng J. Multi-Scale Multi-Branch Convolutional Neural Network on Google Earth Engine for Root-Zone Soil Salinity Retrieval in Arid Agricultural Areas. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2534. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112534

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Wenli, Xinjun Wang, Songrui Ning, Wanzhi Zhou, Shenghan Gao, Chenyu Li, Yu Huang, Luan Dong, and Jiandong Sheng. 2025. "Multi-Scale Multi-Branch Convolutional Neural Network on Google Earth Engine for Root-Zone Soil Salinity Retrieval in Arid Agricultural Areas" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2534. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112534

APA StyleDong, W., Wang, X., Ning, S., Zhou, W., Gao, S., Li, C., Huang, Y., Dong, L., & Sheng, J. (2025). Multi-Scale Multi-Branch Convolutional Neural Network on Google Earth Engine for Root-Zone Soil Salinity Retrieval in Arid Agricultural Areas. Agronomy, 15(11), 2534. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112534