Microwave-Induced Inhibition of Germination in Portulaca oleracea L. Seeds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Substrate Sampling

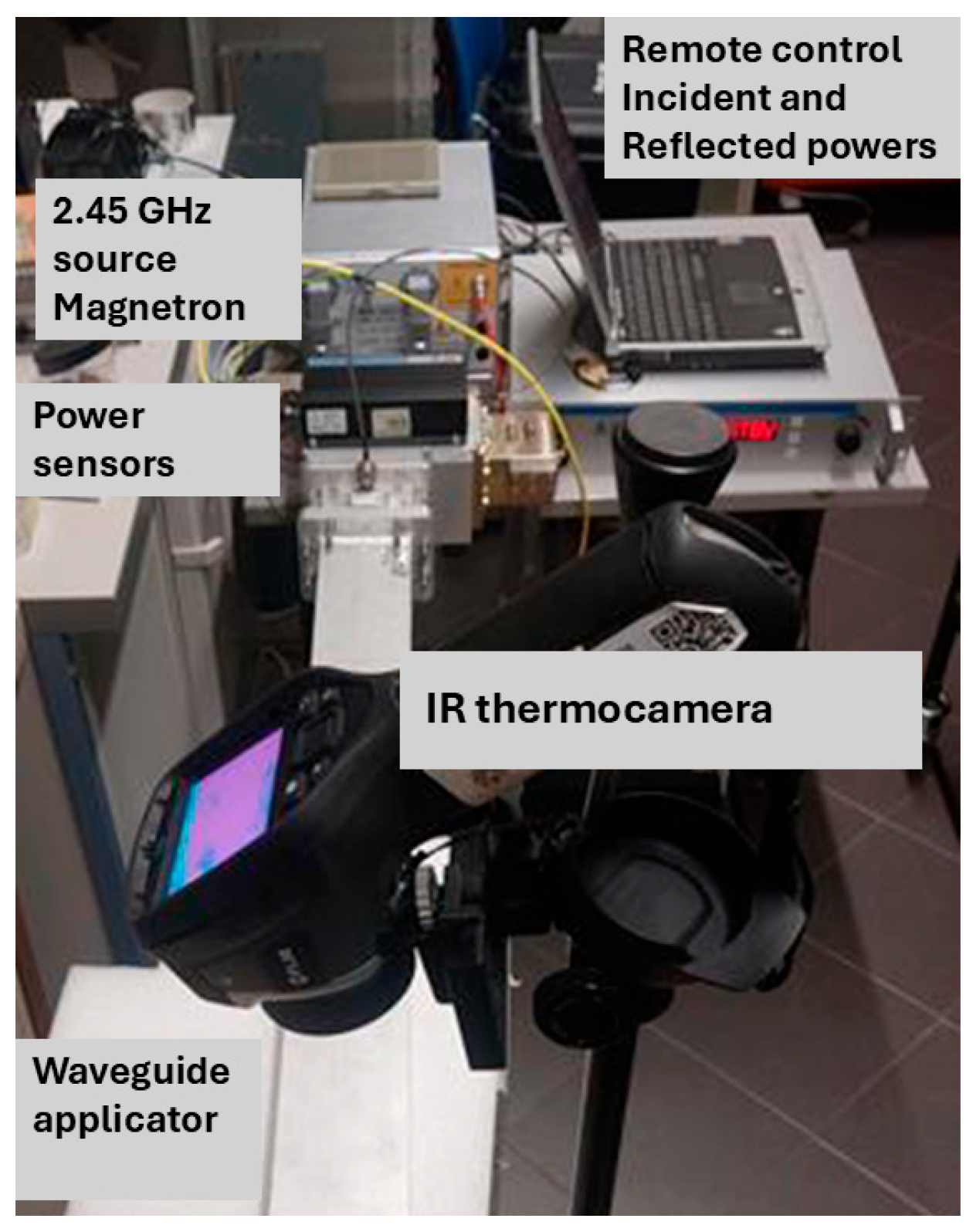

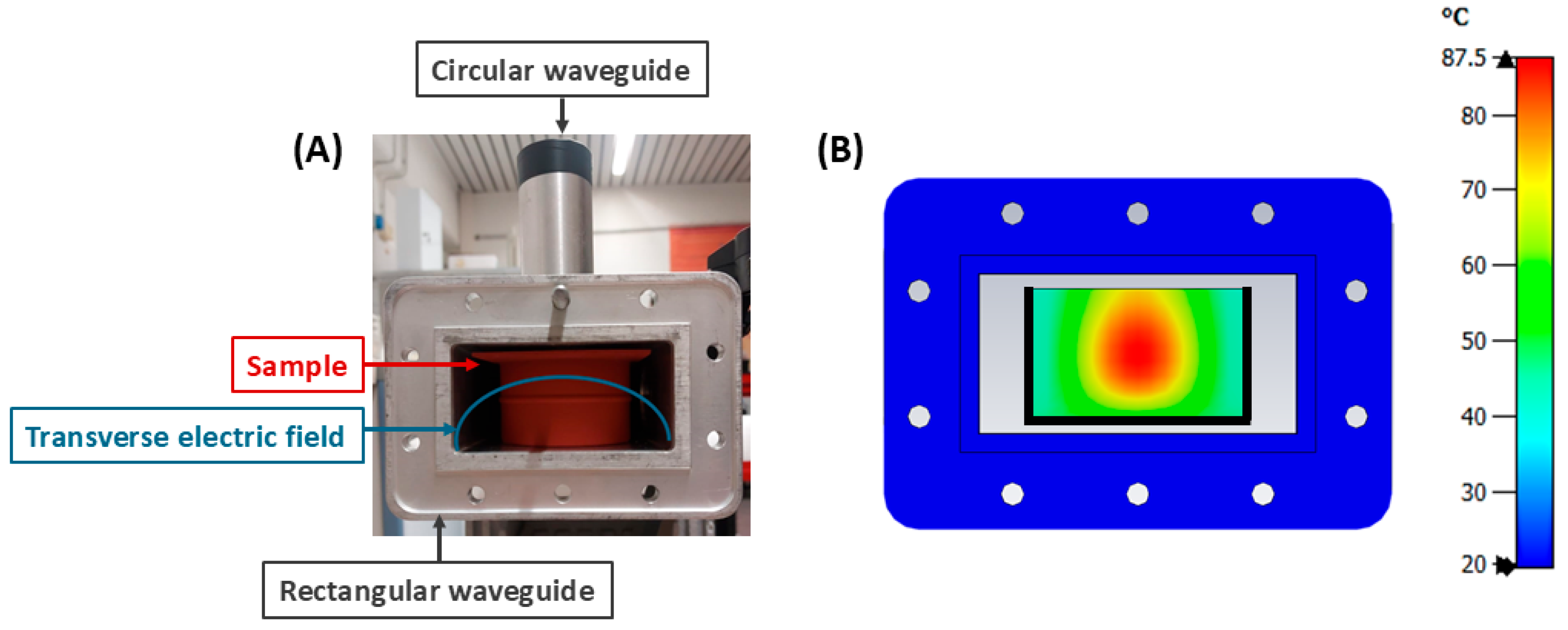

2.2. Microwave Exposure Set-Up

2.3. Experimental Design for Microwave Exposure

2.4. Germination Tests

2.5. Statistics

3. Results

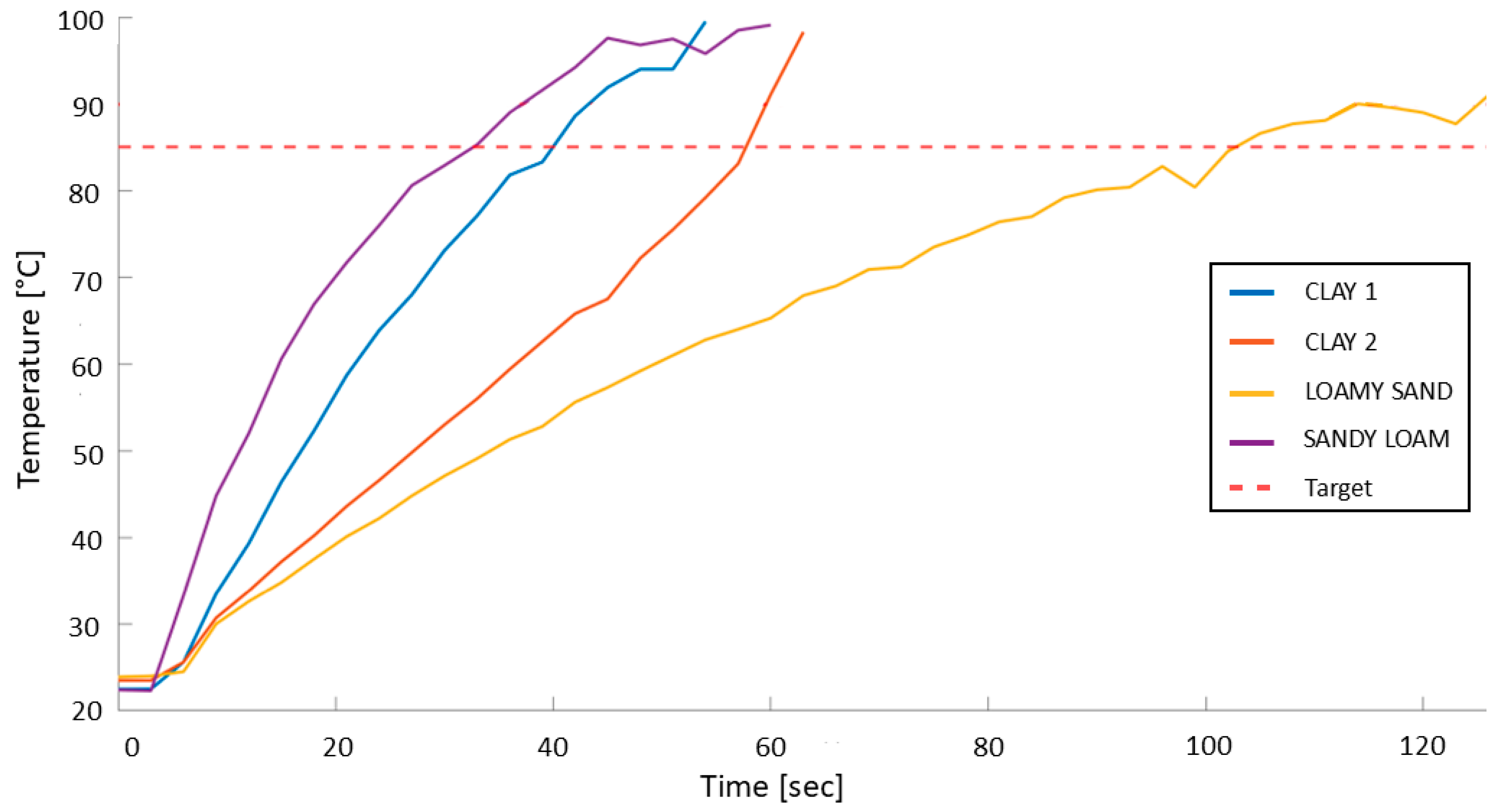

3.1. Soil Substrate Heating with Microwave Radiation

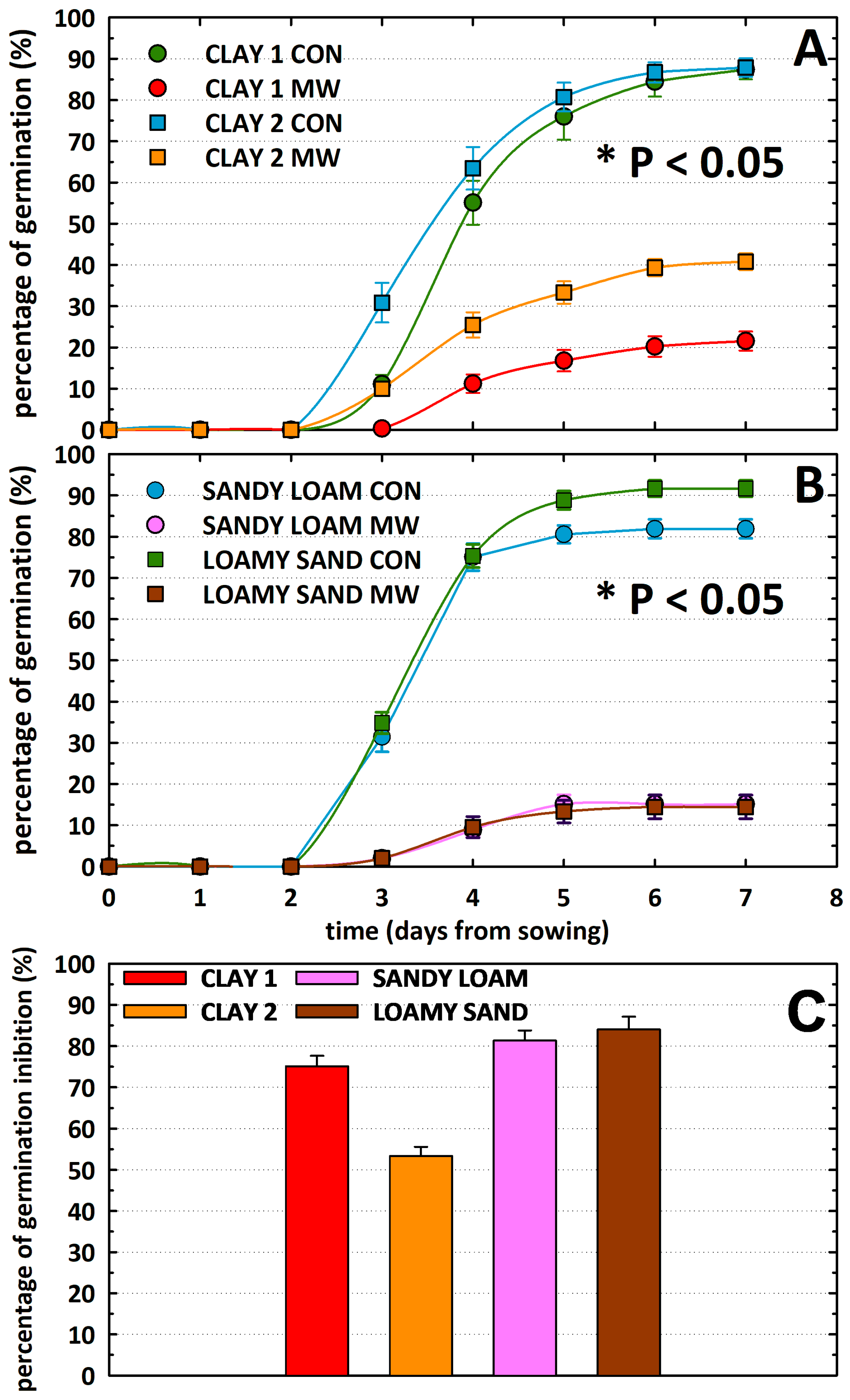

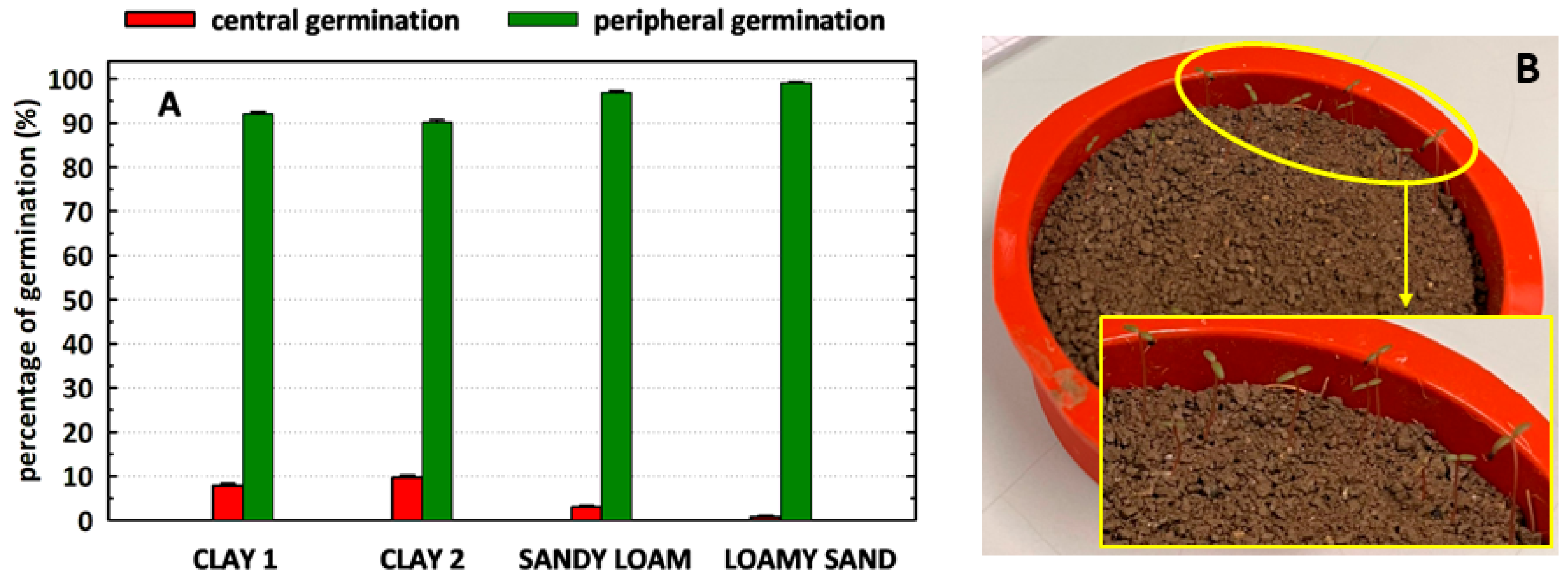

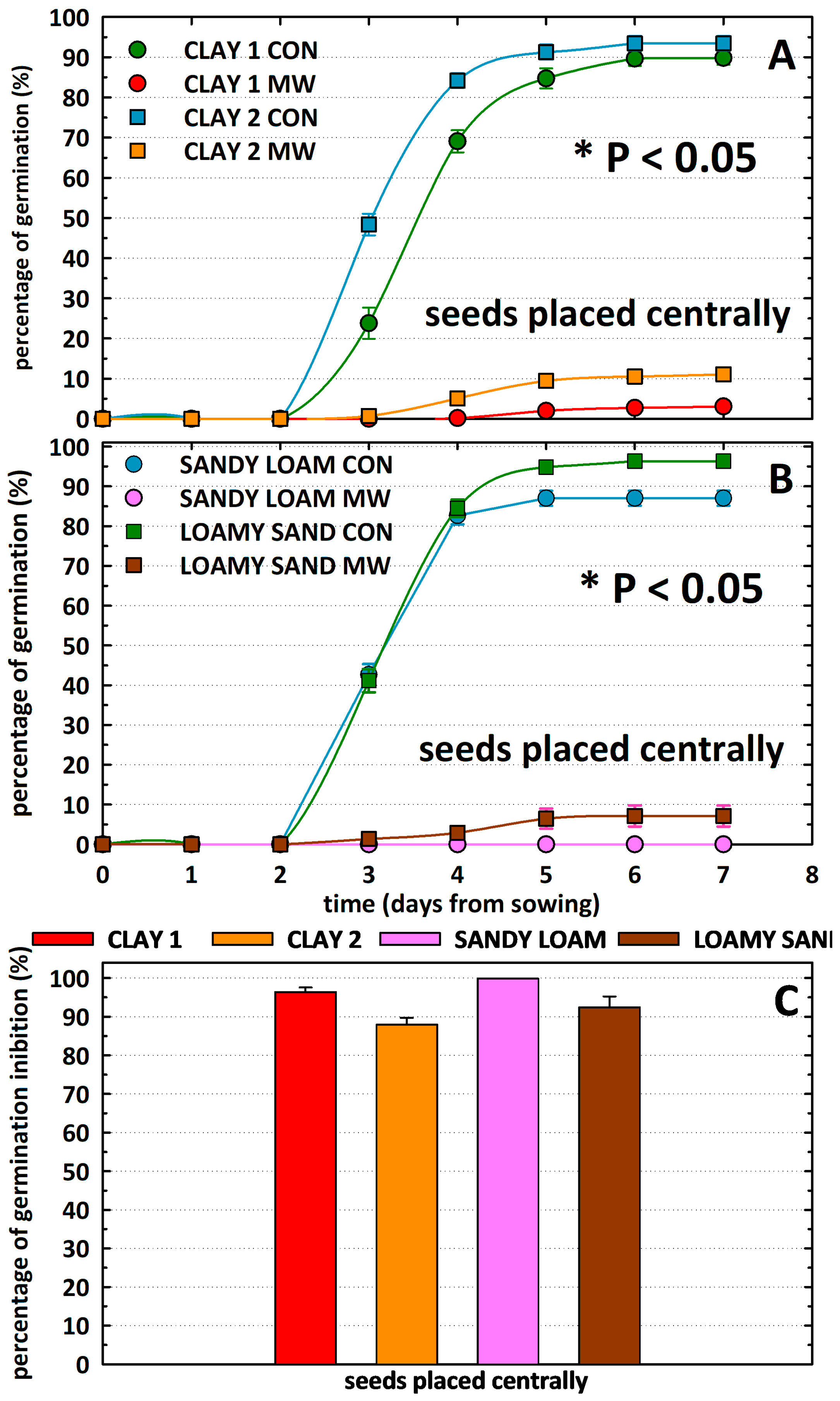

3.2. Seed Germination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WG | Waveguide |

| IR | Infrared |

| SWC | Soil–water content |

| CON | Control |

| MW | Microwave |

| SE | Standard Error |

| ANOVA | Analysis Of Variance |

| LSD | Least Significant Difference |

References

- Oerke, E.-C. Crop Losses to Pests. J. Agric. Sci. 2006, 144, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasena, N. How will weed management change under climate change? Some perspectives. J. Crop Weed 2009, 5, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- De Wilde, M.; Buisson, E.; Yavercovski, N.; Willm, L.; Bieder, L.; Mesléard, F. Using Microwave Soil Heating to Inhibit Invasive Species Seed Germination. Invasive Plant Sci. Manag. 2017, 10, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tataridas, A.; Kanatas, P.; Chatzigeorgiou, A.; Zannopoulos, S.; Travlos, I. Sustainable Crop and Weed Management in the Era of the EU Green Deal: A Survival Guide. Agronomy 2022, 12, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heap, I. The International Herbicide-Resistant Weed Database. WeedScience.org. Available online: https://www.weedscience.org. (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Fanti, A.; Spanu, M.; Lodi, M.B.; Desogus, F.; Mazzarella, G. Nonlinear Analysis of Soil Microwave Heating: Application to Agricultural Soils Disinfection. IEEE J. Multiscale Multiphys. Comput. Tech. 2017, 2, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S.O. A Review and Assessment of Microwave Energy for Soil Treatment to Control Pests. Trans. ASAE 1996, 39, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, G.; Botta, C.; Woodworth, J. Preliminary Investigation into Microwave Soil Pasteurization Using Wheat as a Test Species. Plant Prot. Q. 2007, 22, 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, G.; Torgovnikov, G. Microwave Soil Heating with Evanescent Fields from Slow-Wave Comb and Ceramic Applicators. Energies 2022, 15, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, G.; Khan, M.J.; Gupta, D. Microwave soil treatment and plant growth. In Microwave Systems and Applications; Brodie, G., Khan, M.J., Balkrishnan, G., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; pp. 161–184. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.J.; Jurburg, S.D.; He, J.; Brodie, G.; Gupta, D. Impact of Microwave Disinfestation Treatments on the Bacterial Communities of No-till Agricultural Soils. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2020, 71, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.H. Controlling Gorse Seedbanks with Microwave Energy. In Proceedings of the 15th Australian Weeds Conference, Weed Management Society of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia, 24–28 September 2006; pp. 283–286. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, G.; Hamilton, S.; Woodworth, J. An Assessment of Microwave Soil Pasteurization for Killing Seeds and Weeds. Plant Prot. Q. 2007, 22, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.J.; Brodie, G.; Gupta, D. Potential of Microwave Soil Heating for Weed Management and Yield Improvement in Rice Cropping. Crop. Pasture Sci. 2019, 70, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Brodie, G.; Jurburg, S.D.; Chen, Q.; Hu, H.-W.; Gupta, D.; Mattner, S.W.; He, J.-Z. Assessing the Effects of Microwave Heat Disturbance on Soil Microbial Communities in Australian Agricultural Environments: A Microcosm Study. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 198, 105386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebawi, F.F.; Cooper, A.P.; Brodie, G.I.; Madigan, B.A.; Vitelli, J.S.; Worsley, K.J.; Davis, K.M. Effect of microwave radiation on seed mortality of rubber vine (Cryptostegia grandiflora R. Br.), parthenium (Parthenium hysterophorus L.) and bellyache bush (Jatropha gossypiifolia L.). Plant Prot. Q. 2007, 22, 136–142. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.P. Effect of temperature and light on seed germination of two ecotypes of portulaca oleracea L. New Phytol. 1973, 72, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AnastáCio, A.; Carvalho, I.S. Accumulation of Fatty Acids in Purslane Grown in Hydroponic Salt Stress Conditions. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 64, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyanishi, K.; Cavers, P.B. The biology of Canadian weeds.: 40. Portulaca oleracea L. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1980, 60, 953–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egley, G.H. Dormancy variations in common purslane seeds. Weed Sci. 1974, 22, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinato, M.I.; Moody, K.; Piggin, C.M. Upland Rice Weeds of South and Southeast Asia; International Rice Research Institute: Los Baños, Philippines, 1999; p. 47. ISBN 978-971-22-0077-9. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, B.S.; Johnson, D.E. Seed germination ecology of Portulaca oleracea L.: An important weed of rice and upland crops. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2009, 155, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaciari, M.; Orlandi, F.; Ruga, L.; Pezzolla, D.; Cocozza, C.; Ederli, L. Impact of Varied Microwave Exposures on Weed Species. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falciglia, P.P.; Roccaro, P.; Bonanno, L.; De Guidi, G.; Vagliasindi, F.G.A.; Romano, S. A Review on the Microwave Heating as a Sustainable Technique for Environmental Remediation/Detoxification Applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 95, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA NRCS. Chapter 3: Selected Chemical and Physical Properties. In Soil Survey Manual; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-09/SSM-ch3.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Vidotto, F.; De Palo, F.; Ferrero, A. Effect of Short-duration High Temperatures on Weed Seed Germination. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2013, 163, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, R.; Lodato, F.; Carraturo, F.; Nappo, A.; Annunziata, M.; Guida, M.; D’Ambrosio, N. Preliminary Results on Fungicidal Efficacy of Microwave Treatment on Fusarium oxysporum. In Proceedings of the 4th URSI Atlantic Radio Science Meeting (AT-RASC), Meloneras, Spain, 19–24 May 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Romeo, S.; D’Avino, C.; Pinchera, D.; Zeni, O.; Scarfi, M.R.; Massa, R. A Waveguide Applicator for In Vitro Exposures to Single or Multiple ICT Frequencies. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2013, 61, 1994–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, M.C.; Ulaby, F.T.; Hallikainen, M.T.; El-Rayes, M.A. Microwave dielectric behavior of wet soil, Part II: Dielectric mixing models. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1985, GRS-23, 3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, G.; Harris, G.; Pasma, L.; Travers, A.; Leyson, D.; Lancaster, C.; Woodworth, J. Microwave soil heating for controlling ryegrass seed germination. Trans. ASABE 2009, 52, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, R.; Migliore, M.D.; Panariello, G.; Pinchera, D.; Schettino, F.; Caprio, E.; Griffo, R. Wide Band Permittivity Measurements of Palm (Phoenix Canariensis) and Rhynchophorus Ferrugineus (Coleoptera Curculionidae) for RF Pest Control. J. Microw. Power Electromagn. Energy 2014, 48, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, R.E. Foundation of Microwave Engineering. McGraw-Hill Book Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Metaxas, A.C.; Meredith, R. Industrial Microwave Heating; Peter Peregrinus: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Maynaud, G.; Baudoin, E.; Bourillon, J.; Duponnois, R.; Cleyet-Marel, J.-C.; Brunel, B. Short-term Effect of 915-MHz Microwave Treatments on Soil Physicochemical and Biological Properties. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2019, 70, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, G.; Pchelnikov, Y.; Torgovnikov, G. Development of Microwave Slow-Wave Comb Applicators for Soil Treatment at Frequencies 2.45 and 0.922 GHz (Theory, Design, and Experimental Study). Agriculture 2020, 10, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Soil Substrate | Water Content % | Power | Exposure Time | Time to Reach 85 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campania 1 | CLAY 1 | 15.2% | 300 W | 60 s | 41 s |

| Campania 2 | CLAY 2 | 18.0% | 300 W | 60 s | 58 s |

| Lombardia | SANDY LOAM | 14.8% | 400 W | 60 s | 35 s |

| Sardinia | LOAMY SAND | 7.2% | 400 W | 120 s | 113 s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Ambrosio, N.; Di Sio, F.; Esposito, A.; Lodato, F.; Massa, R.; Chirico, G.; Schettino, F. Microwave-Induced Inhibition of Germination in Portulaca oleracea L. Seeds. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2418. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102418

D’Ambrosio N, Di Sio F, Esposito A, Lodato F, Massa R, Chirico G, Schettino F. Microwave-Induced Inhibition of Germination in Portulaca oleracea L. Seeds. Agronomy. 2025; 15(10):2418. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102418

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Ambrosio, Nicola, Francesca Di Sio, Alessio Esposito, Francesca Lodato, Rita Massa, Gaetano Chirico, and Fulvio Schettino. 2025. "Microwave-Induced Inhibition of Germination in Portulaca oleracea L. Seeds" Agronomy 15, no. 10: 2418. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102418

APA StyleD’Ambrosio, N., Di Sio, F., Esposito, A., Lodato, F., Massa, R., Chirico, G., & Schettino, F. (2025). Microwave-Induced Inhibition of Germination in Portulaca oleracea L. Seeds. Agronomy, 15(10), 2418. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102418