Evaluation of Drought Tolerance in Oat × Maize Addition Lines Through Biochemical and Yield Traits

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Biochemical Analysis

2.3. Morphological Observation and Analysis of Selected Yield Components

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

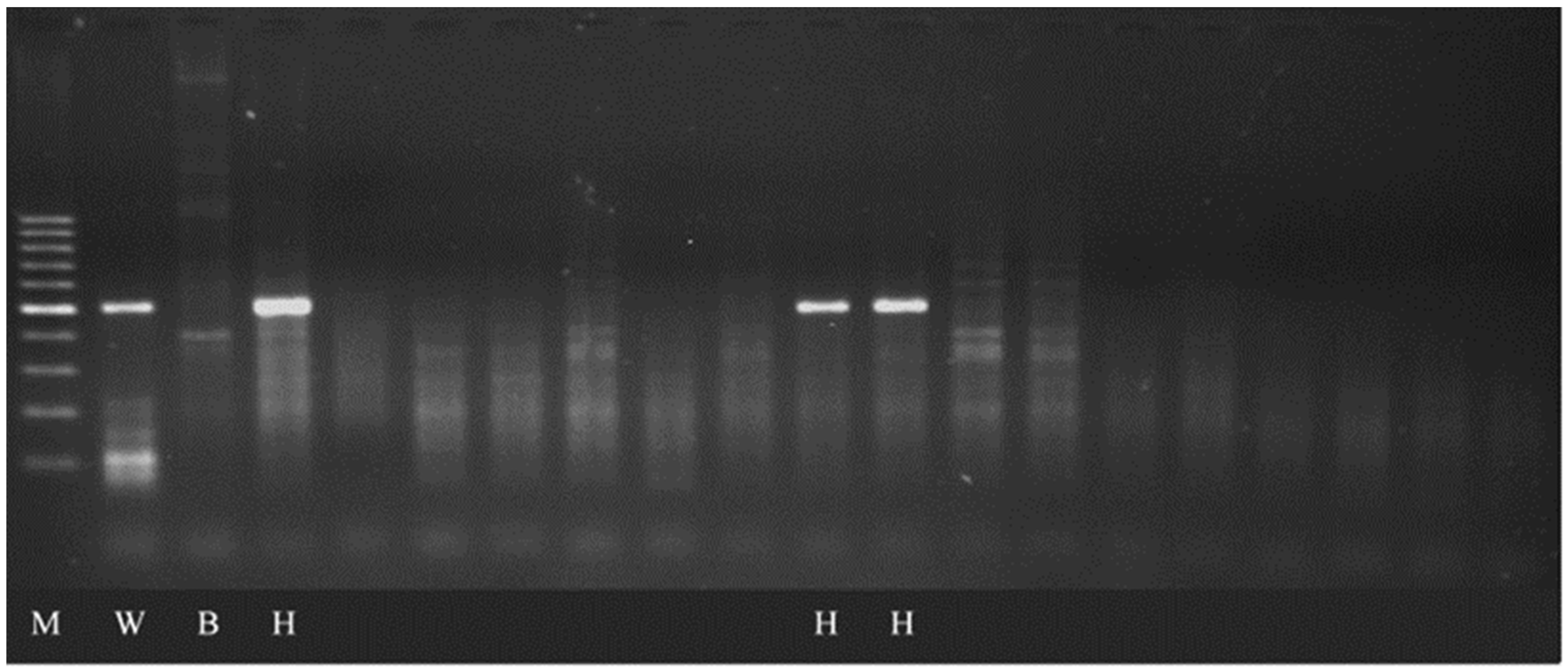

3.1. Detection of OMA Lines

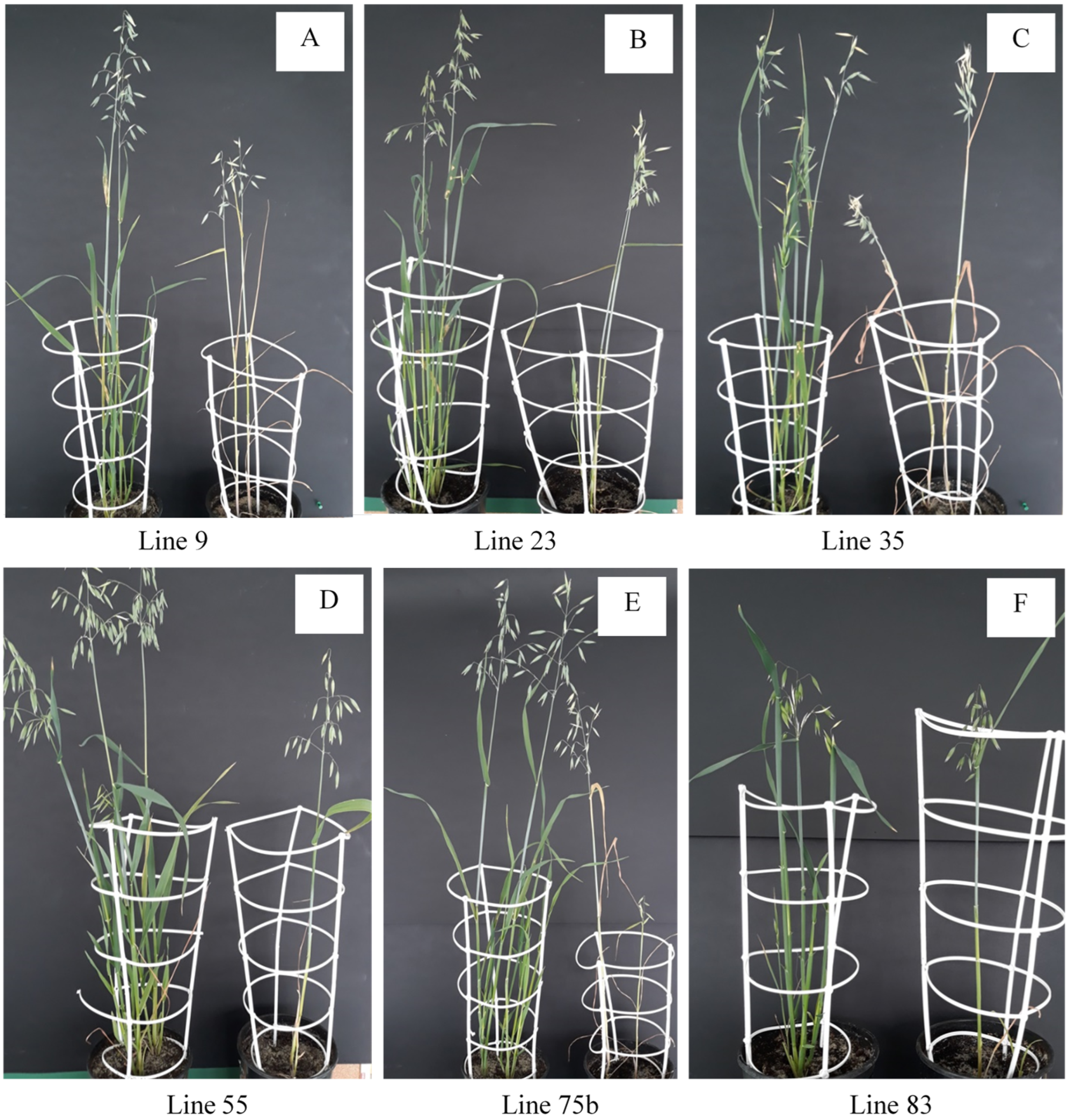

3.2. Morphological Differences in Response to Drought Stress

3.3. Statistical Analysis of Biochemical and Yield-Related Traits

3.4. Analysis of Biochemical Parameters Observed on the First Day of Drought (20% RWC)

3.5. Analysis of Biochemical Parameters Observed on the Fourteenth Day of Drought (20% RWC)

3.6. Analysis of Selected Yield Components

3.7. Shoot Biomass

3.8. Number of Grains

3.9. Grain Weight

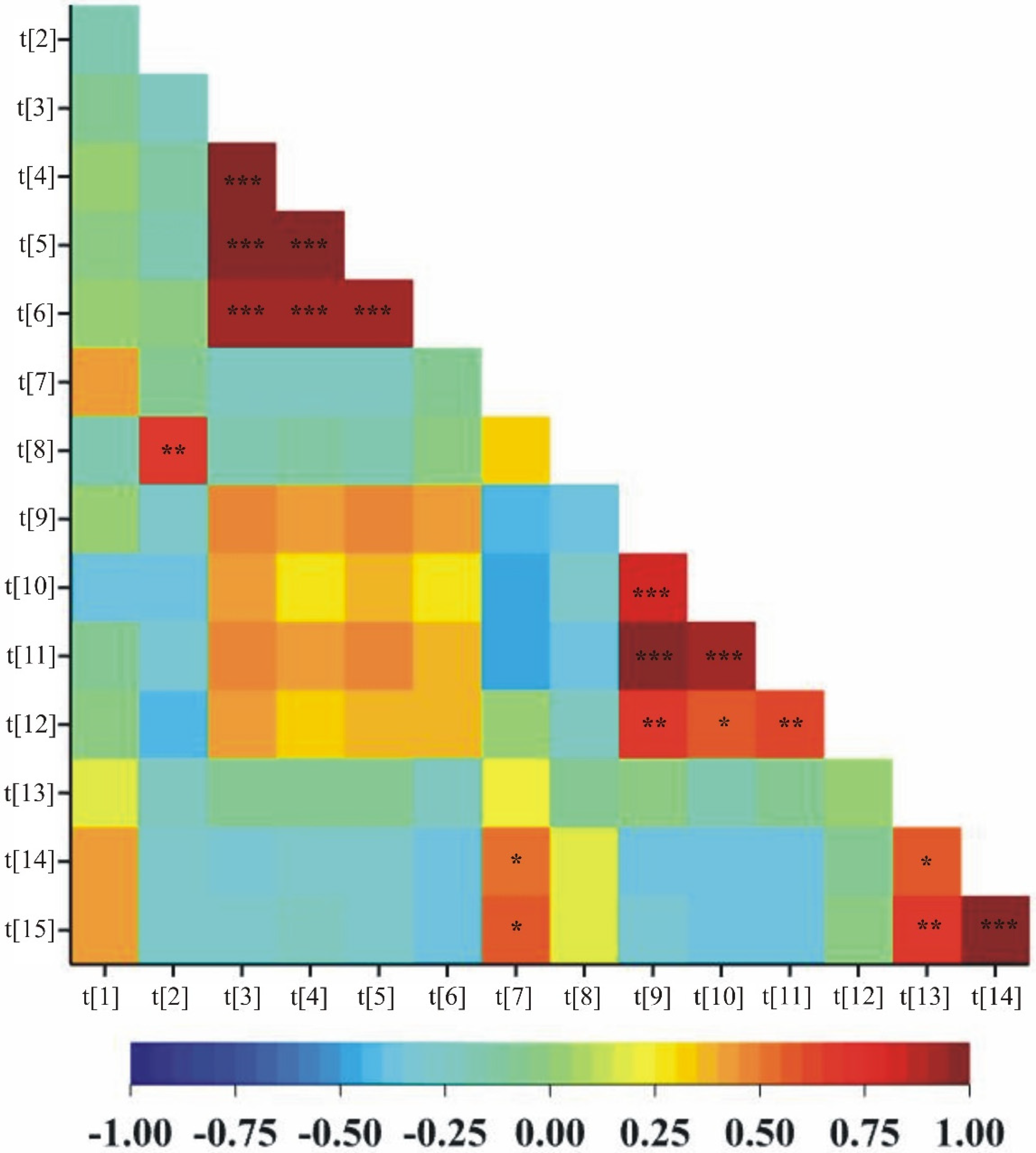

3.10. Correlation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Sadras, V.O.; Calderini, D.F. (Eds.) Crop Physiology: Case Histories for Major Crops; Academic Press (Elsevier): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAOSTAT). Available online: https://data.apps.fao.org/catalog/dataset/crop-production-yield-harvested-area-global-national-annual-faostat (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Pisulewska, E.; Tobiasz-Salach, R.; Witkowicz, R.; Cieślik, E.; Bobrecka-Jamro, D. Effect of habitat conditions on content and quality of lipids in selected oat forms. Żywność. Nauka. Technol. Jakość 2011, 3, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleksiak, T.; Spyroglou, I.; Pacoń, D.; Matysik, P.; Pernisová, M.; Rybka, K. Effect of drought on wheat production in Poland between 1961 and 2019. Crop Sci. 2022, 62, 728–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnabás, B.; Jäger, K.; Fehér, A. The effect of drought and heat stress on reproductive processes in cereals. Plant Cell Environ. 2008, 31, 11–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhatreh, Y.; Kafawin, O.; Ceccarelli, S.; Saoub, H. Selection of barley lines for drought tolerance in low rainfall areas. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2001, 186, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarah, N.; Alqudah, A.; Amayreh, J.; McAndrews, G. The Effect of Late-terminal Drought Stress on Yield Components of Four Barley Cultivars. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2009, 195, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryanto, S.; Wang, L.; Jacinthe, P.-A. Global Synthesis of Drought Effects on Maize and Wheat Production. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Shiran, B.; Wan, J.; Lewis, D.C.; Jenkins, C.L.D.; Condon, A.G.; Richards, R.A.; Dolferus, R. Importance of pre-anthesis anther sink strength for maintenance of grain number during reproductive stage water stress in wheat. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 926–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okagaki, R.J.; Kynast, R.G.; Livingston, S.M.; Russell, C.D.; Rines, H.W.; Phillips, R.L. Mapping maize sequences to chromosomes using oat-maize chromosome addition materials. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, H. Drought resistance in plants. In Mechanisms of Environmental Stress Resistance in Plants; Basra, A.S., Basra, R.K., Eds.; Harwood Academic Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, F.; Buitink, J. Mechanisms of plant desiccation tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2001, 8, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stitt, M.; Hurry, V. A plant for all seasons: Alterations in photosynthetic carbon metabolism during cold acclimation in Arabidopsis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002, 5, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.W.; Toth, Z. Effect of Drought Stress on Potato Production: A Review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Pellny, T. Carbon metabolite feedback regulation of leaf photosynthesis and development. J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrar, J.F. Fluxes and turnover of sucrose and fructans in healthy and diseased plants. J. Plant Physiol. 1989, 134, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M.; Abe, J.; Moriyama, M.; Shimokawa, S.; Nakamura, Y. Seasonal changes in the physical state of crown water associated with freezing tolerance in winter wheat. Physiol. Plant. 1997, 99, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woloshuk, C.P.; Meulenhof, J.S.; Sela-Buurlage, M.; van den Elzen, P.J.M.; Cornelissen, B.J.C. Pathogen-induced proteins with inhibitor activity toward Phytophthora infestans. Plant Cell 1991, 3, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tejeda-Sartorius, O.; Soto-Hernández, R.M.; San Miguel-Chávez, R.; Trejo-Téllez, L.I.; Caamal-Velázquez, H. Endogenous hormone profile and sugars display differential distribution in leaves and pseudobulbs of Laelia anceps plants induced and non-induced to flowering by exogenous gibberellic acid. Plants 2022, 11, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basharat, S.; Huang, Z.; Gong, M.; Lv, X.; Ahmed, A.; Hussain, I.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Liu, L. A review on current conventional and biotechnical approaches to enhance biosynthesis of steviol glycoside in Stevia rebaudiana. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 30, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rines, H.W.; Phillips, R.L.; Kynast, R.G.; Okagaki, R.J.; Galatowitsch, M.W.; Huettl, P.A.; Stec, A.O.; Jacobs, M.S.; Suresh, J.; Porter, H.L.; et al. Addition of individual chromosomes of maize inbreds B73 and Mo17 to oat cultivars Starter and Sun II: Maize chromosome retention, transmission, and plant phenotype. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009, 119, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananiev, E.V.; Phillips, R.L.; Rines, H.W. Chromosome-specific molecular organization of maize (Zea mays L.) centromeric regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 13073–13078. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlbauer, G.J.; Riera-Lizarazu, O.; Kynast, R.G.; Martin, D.; Phillips, R.L.; Rines, H.W. A maize chromosome 3 addition line of oat exhibits expression of the maize homeobox gene liguleless3 and alteration of cell fates. Genome 2000, 43, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowles, R.V.; Walch, M.D.; Minnerath, J.M.; Bernacchi, C.J.; Stec, A.O.; Rines, H.W.; Phillips, R.L. Expression of C4 photosynthetic enzymes in oat-maize chromosome addition lines. Maydica 2008, 53, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Walch, M.D. Expression of Maize Pathogenesis-Related and Photosynthetic Genes in Oat × Maize Addition Lines. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Warzecha, T.; Bathelt, R.; Skrzypek, E.; Warchoł, M.; Bocianowski, J.; Sutkowska, A. Studies of oat-maize hybrids tolerance to soil drought stress. Agriculture 2023, 13, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kynast, R.G.; Riera-Lizarazu, O.; Vales, M.I.; Okagaki, R.J.; Maquieira, S.B.; Chen, G.; Ananiev, E.V.; Odland, W.E.; Russell, C.D.; Stec, A.O.; et al. A complete set of maize individual chromosome additions to the oat genome. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 1216–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Yu, J.; Li, H.; Huang, W.; Xu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Xu, W.; Jiang, J.; Su, Z.; et al. Transcriptional and epigenetic adaptation of maize chromosomes in oat–maize addition lines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 5012–5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosnowska, K.; Majka, M.; Majka, J.; Bocianowski, J.; Kasprowicz, M.; Książczyk, T.; Szała, L.; Cegielska-Taras, T. Chromosome instabilities in resynthesized Brassica napus revealed by FISH. J. Appl. Genet. 2020, 61, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarillo, F.I.E.; Bass, H.W. A transgenomic cytogenetic sorghum (Sorghum propinquum) bacterial artificial chromosome fluorescence in situ hybridization map of maize (Zea mays L.) pachytene chromosome 9, evidence for regions of genome hyperexpansion. Genetics 2007, 177, 1509–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.J.; Arumuganathan, K.; Rines, H.W.; Phillips, R.L.; Riera-Lizarazu, O.; Sandhu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Gill, K.S. Flow cytometric sorting of maize chromosome 9 from an oat–maize chromosome addition line. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001, 102, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warchoł, M.; Juzoń-Sikora, K.; Rančić, D.; Pećinar, I.; Warzecha, T.; Idziak-Helmcke, D.; Laskoś, K.; Czyczyło-Mysza, I.; Dziurka, K.; Skrzypek, E. Comparative characteristics of oat doubled haploids and oat × maize addition lines: Anatomical features of the leaves, chlorophyll a fluorescence and yield parameters. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kynast, R.; Okagaki, R.; Rines, H.; Phillips, R. Maize individualized chromosome and derived radiation hybrid lines and their use in functional genomics. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2002, 2, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohm, H.; Shaner, G. Breeding oat for resistance to diseases. In Oat Science and Technology; Marshall, H., Sorrells, M., Eds.; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rines, H.W.; Phillips, R.L.; Kynast, R.G.; Okagaki, R.; Odland, W.E.; Stec, A.O.; Jacobs, M.S.; Granath, S.R. Maize chromosome additions and radiation hybrids in oat and their use in dissecting the maize genome. In Proceedings of the International Congress “In the Wake of the Double Helix: From the Green Revolution to the Gene Revolution”, Bologna, Italy, 27–31 May 2003; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 427–441. [Google Scholar]

- Marcińska, I.; Nowakowska, A.; Skrzypek, E.; Czyczyło-Mysza, I. Production of double haploids in oat (Avena sativa L.) by pollination with maize (Zea mays L.). Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2013, 8, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warzecha, T.; Bocianowski, J.; Warchoł, M.; Bathelt, R.; Sutkowska, A.; Skrzypek, E. Effect of Soil Drought Stress on Selected Biochemical Parameters and Yield of Oat × Maize Addition (OMA) Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Roberts, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic Phosphotungstic Acid Reagent. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Wellburn, A.R. Determinations of total carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1983, 11, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Bocianowski, J.; Rybiński, W. Selection of promising genotypes based on path and cluster analyses. J. Agric. Sci. 2008, 146, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocianowski, J.; Majchrzak, L. Analysis of effects of cover crop and tillage method combinations on the phenotypic traits of spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using multivariate methods. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 15267–15276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalanobis, P.C. On the generalized distance in statistics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1936, 12, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- VSN International. Genstat for Windows, 23rd ed.; VSN International: Hemel Hempstead, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka, R.; Furbank, R.; Fukayama, H.; Miyao, M. Molecular Engineering of C4 Photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 2001, 52, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ober, E.S.; Le Bloa, M.L.; Clark, C.J.A.; Royal, A.; Jaggard, K.W.; Pidgeon, J.D. Evaluation of Physiological Traits as Indirect Selection Criteria for Drought Tolerance in Sugar Beet. Field Crops Res. 2005, 91, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadkhani, N.; Heidari, R. Drought-Induced Accumulation of Soluble Sugars and Proline in Two Maize Varieties. World Appl. Sci. J. 2008, 3, 448–453. [Google Scholar]

- Redillas, M.; Park, S.H.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, J.; Jung, H.; Bang, S.; Hahn, T.R.; Kim, J.K. Accumulation of Trehalose Increases Soluble Sugar Contents in Rice Plants Conferring Tolerance to Drought and Salt Stress. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2011, 6, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezayian, M.; Niknam, V.; Ebrahimzadeh, H. Differential Responses of Phenolic Compounds of Brassica napus under Drought Stress. Iran. J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 8, 2417–2425. [Google Scholar]

- Sinay, H.; Karuwal, R. Proline and Total Soluble Sugar Content at the Vegetative Phase of Six Corn Cultivars from Kisar Island Maluku, Grown under Drought Stress Conditions. Int. J. Adv. Agric. Res. 2014, 2, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Warzecha, T.; Zieliński, A.; Skrzypek, E.; Wójtowicz, T.; Moś, M. Effect of Mechanical Damage on Vigor, Physiological Parameters, and Susceptibility of Oat (Avena sativa) to Fusarium culmorum Infection. Phytoparasitica 2012, 40, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, C.; Schafleitner, R.; Guignard, C.; Oufir, M.; Aliaga, C.; Nomberto, G.; Hoffmann, L.; Hausman, J.F.; Evers, D.; Larondelle, Y. Modification of the Health-Promoting Value of Potato Tubers Field Grown under Drought Stress: Emphasis on Dietary Antioxidant and Glycoalkaloid Contents in Five Native Andean Cultivars (Solanum tuberosum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Guo, P.; Baum, M.; Grando, S.; Salvatore, C. Evaluation of Chlorophyll Content and Fluorescence Parameters as Indicators of Drought Tolerance in Barley. Agric. Sci. China 2006, 5, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Flexas, J.; Pinheiro, C. Photosynthesis under Drought and Salt Stress: Regulation Mechanisms from Whole Plant to Cell. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayalakshmi, K.; Fritz, A.K.; Paulsen, G.M.; Bai, G.; Pandravada, S.; Gill, B.S. Modeling and mapping QTL for senescence-related traits in winter wheat under high temperature. Mol. Breed. 2010, 26, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamin, R.; Khayatnezhad, M. Assessment of the Correlation between Chlorophyll Content and Drought Resistance in Corn Cultivars (Zea mays). Helix 2020, 10, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleel, C.A.; Manivannan, P.; Wahid, A.; Farooq, M.; Somasundaram, R.; Panneerselvam, R. Drought Stress in Plants: A Review on Morphological Characteristics and Pigments Composition. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2009, 11, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan, N.D.; Kulandaivelu, G. Drought-Induced Changes in Physiological, Biochemical and Phytochemical Properties of Withania somnifera Dun. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 3929–3935. [Google Scholar]

- Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Ahmadi, J.; Mehrabi, A.A.; Etminan, A.; Moghaddam, M.; Siddique, K.H.M. Physiological Responses to Drought Stress in Wild Relatives of Wheat: Implications for Wheat Improvement. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2017, 39, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteoliva, M.I.; Guzzo, M.C.; Posada, G.A. Breeding for Drought Tolerance by Monitoring Chlorophyll Content. Gene Technol. 2021, 10, 165. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaeva, M.K.; Maevskaya, S.N.; Shugaev, A.G.; Bukhov, N.G. Effect of Drought on Chlorophyll Content and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in Leaves of Three Wheat Cultivars Varying in Productivity. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2010, 57, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarah, N.H. Effects of Drought Stress on Growth and Yield of Barley. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 25, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| OMA Line Number | Origin |

|---|---|

| 1b | Bingo × Contender |

| 9 | D 109/10 × DC 2112/05 |

| 12 | STH 8-99 × DC 2112/06 |

| 18 | DC 06011-6 × POB 722 |

| 23 | STH 9511 × Bingo |

| 26 | Krezus × Bingo |

| 35 | (Chwat × Bingo) × STH 9110 |

| 42 | DC 2648/04 × Bingo |

| 43 | DC 2648/04 × Bingo |

| 55 | STH 8-50 × Canyon |

| 78b | Breton × Zolak 43/6 |

| 83 | STH 9787(b) × Bingo |

| 114 | Chimene × STH 85763(b) |

| 119 | Bingo × Chimene |

| Treatments | Growth stages of oat plants | |||||

| Sowing, germination, leaf development, and tillering BBCH 00–27 | End of tillering BBCH 27 | Beginning of stem elongation BBCH 31 | End of stem elongation BBCH 37 | Development and maturation BBCH 37–92 | Harvest of hard grains BBCH 92 | |

| First day of drought stress | Fourteenth day of drought stress | |||||

| Soil drought | Irrigation up to 70% of field water capacity (FWC) | Cessation of irrigation—FWC decreases from 70% to 20% | Soil drought—20% FWC | Resumption of irrigation—up to 70% FWC | ||

| Control conditions | Irrigation up to 70% FWC during whole vegetation period | |||||

| Measurements/activities performed | Sampling for biochemical analysis | Sampling for biochemical analysis | Photographic documentation of plants | Harvest of above ground plant organs (stems and panicles) | ||

| Trait | Soluble Sugars (mg g−1 DW) | Phenolic Compounds (mg g−1 DW) | Chlorophyll a (mg g−1 DW) | Chlorophyll b (mg g−1 DW) | Chlorophyll a and b (mg g−1 DW) | Carotenoids (mg g−1 DW) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Genotype | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. |

| C | 9 | 191.6 | 49.32 | 64.02 | 5.79 | 0.68 | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.02 | 1.03 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.01 |

| 12 | 205.5 | 25.45 | 50.05 | 4.63 | 0.72 | 0.12 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 1.07 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.03 | |

| 18 | 122.2 | 17.64 | 50.85 | 1.35 | 0.82 | 0.08 | 0.37 | 0.03 | 1.20 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.01 | |

| 23 | 242.3 | 41.40 | 55.05 | 1.76 | 0.65 | 0.06 | 0.32 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.01 | |

| 26 | 202.0 | 23.20 | 56.08 | 6.69 | 0.63 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.94 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.01 | |

| 35 | 204.9 | 44.94 | 59.29 | 5.60 | 0.97 | 0.07 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 1.42 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.01 | |

| 42 | 178.0 | 35.35 | 83.50 | 3.91 | 0.64 | 0.15 | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.98 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.03 | |

| 43 | 165.4 | 15.03 | 65.42 | 8.16 | 0.62 | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.02 | |

| 55 | 235.9 | 14.43 | 57.12 | 1.22 | 0.95 | 0.08 | 0.43 | 0.03 | 1.38 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.04 | |

| 83 | 274.0 | 27.52 | 52.23 | 2.93 | 0.71 | 0.05 | 0.38 | 0.03 | 1.09 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.02 | |

| 114 | 218.7 | 41.54 | 61.22 | 4.41 | 0.71 | 0.06 | 0.36 | 0.03 | 1.07 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.01 | |

| 119 | 205.3 | 31.33 | 52.92 | 6.80 | 0.65 | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.98 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.02 | |

| 1b | 162.2 | 26.51 | 52.80 | 4.92 | 0.81 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 0.05 | 1.21 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.03 | |

| 78b | 191.8 | 13.90 | 57.42 | 1.50 | 0.61 | 0.11 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.91 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.02 | |

| Bingo | 222.7 | 25.15 | 58.09 | 7.38 | 0.47 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.74 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.02 | |

| D | 9 | 173.2 | 21.49 | 75.45 | 6.74 | 0.59 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| 12 | 227.0 | 30.77 | 55.08 | 0.91 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.77 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.02 | |

| 18 | 137.6 | 21.17 | 58.18 | 3.79 | 0.68 | 0.11 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 1.03 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.02 | |

| 23 | 192.9 | 30.82 | 59.65 | 16.06 | 0.47 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.02 | |

| 26 | 183.2 | 43.67 | 64.16 | 12.58 | 0.64 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.95 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.02 | |

| 35 | 192.7 | 21.08 | 64.40 | 2.01 | 0.79 | 0.06 | 0.44 | 0.04 | 1.23 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.01 | |

| 42 | 220.6 | 46.64 | 78.93 | 3.06 | 0.67 | 0.14 | 0.36 | 0.04 | 1.03 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.03 | |

| 43 | 161.4 | 23.38 | 60.77 | 4.31 | 0.66 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.05 | 0.97 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.04 | |

| 55 | 198.4 | 19.37 | 62.04 | 5.02 | 0.89 | 0.10 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 1.36 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.05 | |

| 83 | 240.5 | 36.25 | 60.11 | 2.30 | 0.72 | 0.08 | 0.32 | 0.09 | 1.04 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.05 | |

| 114 | 167.5 | 25.82 | 70.33 | 5.99 | 0.60 | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.92 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.03 | |

| 119 | 159.5 | 50.21 | 59.91 | 5.52 | 0.51 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.02 | 0.80 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.02 | |

| 1b | 197.6 | 25.94 | 65.08 | 2.87 | 0.73 | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.02 | 1.07 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.01 | |

| 78b | 195.4 | 14.9 | 69.17 | 7.04 | 0.53 | 0.12 | 0.30 | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.03 | |

| Bingo | 233.0 | 31.03 | 54.46 | 7.42 | 0.59 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.03 | 0.89 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.01 | |

| F-ANOVA | 0.032 | 0.064 | 0.078 | 0.115 | 0.142 | 0.076 | |||||||

| LSD0.05 | 43.64 | 8.48 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Trait | Soluble Sugars (mg g−1 DW) | Phenolic Compounds (mg g−1 DW) | Chlorophyll a (mg g−1 DW) | Chlorophyll b (mg g−1 DW) | Chlorophyll a and b (mg g−1 DW) | Carotenoids (mg g−1 DW) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Genotype | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. |

| C | 9 | 216.3 | 32.56 | 67.09 | 5.84 | 0.62 | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 0.93 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.01 |

| 12 | 267.9 | 73.84 | 62.41 | 3.30 | 0.63 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.96 | 0.30 | 0.11 | 0.05 | |

| 18 | 177.2 | 15.96 | 61.29 | 1.56 | 0.71 | 0.07 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 1.10 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.03 | |

| 23 | 285.0 | 26.89 | 62.53 | 3.02 | 0.61 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.02 | |

| 26 | 256.1 | 51.39 | 60.08 | 4.82 | 0.57 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.02 | 0.86 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.01 | |

| 35 | 266.0 | 56.47 | 62.99 | 5.38 | 0.55 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 0.81 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.04 | |

| 42 | 214.9 | 26.78 | 75.78 | 6.04 | 0.62 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.91 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.04 | |

| 43 | 160.4 | 21.41 | 66.85 | 3.11 | 0.54 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.84 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.02 | |

| 55 | 177.8 | 39.1 | 58.69 | 8.41 | 0.81 | 0.18 | 0.35 | 0.09 | 1.16 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.07 | |

| 83 | 220.6 | 30.43 | 63.34 | 9.25 | 0.65 | 0.11 | 0.30 | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.04 | |

| 114 | 161.3 | 16.1 | 55.89 | 10.20 | 0.59 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.89 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.02 | |

| 119 | 163.8 | 25.28 | 48.34 | 7.44 | 0.70 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.06 | 1.02 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.04 | |

| 1b | 148.9 | 22.26 | 59.23 | 1.68 | 0.66 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 0.98 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.03 | |

| 78b | 220.5 | 48.2 | 63.37 | 5.84 | 0.57 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.85 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.01 | |

| Bingo | 275.2 | 47.42 | 63.74 | 8.72 | 0.56 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.03 | |

| D | 9 | 225.5 | 13.73 | 71.84 | 4.46 | 0.56 | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0.05 | 0.88 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.02 |

| 12 | 296.7 | 24.51 | 60.78 | 7.38 | 0.52 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.01 | |

| 18 | 170.1 | 12.24 | 71.78 | 8.14 | 0.74 | 0.06 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 1.09 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.03 | |

| 23 | 329.8 | 31.13 | 66.94 | 20.32 | 0.65 | 0.09 | 0.32 | 0.06 | 0.97 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.03 | |

| 26 | 246.9 | 28.43 | 65.01 | 6.35 | 0.57 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.83 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.03 | |

| 35 | 263.6 | 9.35 | 66.88 | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.10 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 0.91 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.02 | |

| 42 | 238.5 | 39.31 | 74.70 | 3.63 | 0.52 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.81 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.02 | |

| 43 | 194.5 | 10.89 | 63.51 | 3.79 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.86 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.02 | |

| 55 | 236.6 | 14.46 | 62.64 | 5.23 | 0.58 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.88 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.02 | |

| 83 | 289.1 | 40.08 | 65.66 | 5.07 | 0.53 | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0.06 | 0.84 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.03 | |

| 114 | 172.8 | 29.54 | 76.01 | 6.22 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.55 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.01 | |

| 119 | 234.8 | 39.5 | 66.98 | 3.69 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.73 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.02 | |

| 1b | 198.9 | 11.32 | 65.56 | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.00 | |

| 78b | 217.9 | 22.1 | 78.01 | 6.21 | 0.56 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.84 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.02 | |

| Bingo | 361.9 | 78.58 | 62.78 | 11.10 | 0.57 | 0.09 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.87 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.02 | |

| F-ANOVA | 0.118 | 0.018 | 0.037 | 0.086 | 0.048 | 0.14 | |||||||

| LSD0.05 | 50.275 | 9.84 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Trait | The Mass of Stems Plant−1 [g] | The Number of Grains | The Mass of Grains Plant−1 [g] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Genotype | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. |

| C | 9 | 3.61 | 1.09 | 61.75 | 25.14 | 1.68 | 0.54 |

| 12 | 4.51 | 1.34 | 57.75 | 14.41 | 1.82 | 0.52 | |

| 18 | 1.94 | 0.45 | 2.33 | 2.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | |

| 23 | 4.45 | 1.75 | 52.75 | 14.06 | 1.72 | 0.49 | |

| 26 | 5.38 | 1.80 | 43.00 | 14.4 | 1.61 | 0.47 | |

| 35 | 2.83 | 0.57 | 24.25 | 6.29 | 0.73 | 0.13 | |

| 42 | 3.05 | 1.15 | 9.00 | 8.04 | 0.33 | 0.27 | |

| 43 | 3.11 | 0.79 | 26.67 | 2.62 | 0.91 | 0.03 | |

| 55 | 4.10 | 0.50 | 21.75 | 14.55 | 0.79 | 0.53 | |

| 83 | 3.06 | 0.54 | 50.75 | 9.81 | 1.54 | 0.39 | |

| 114 | 2.81 | 0.58 | 21.00 | 26.17 | 0.49 | 0.53 | |

| 119 | 3.16 | 0.89 | 8.50 | 6.45 | 0.26 | 0.19 | |

| 1b | 4.82 | 0.36 | 34.33 | 3.77 | 1.17 | 0.14 | |

| 78b | 4.39 | 1.79 | 61.00 | 21.02 | 1.61 | 0.64 | |

| Bingo | 2.82 | 0.63 | 37.75 | 9.64 | 1.18 | 0.54 | |

| D | 9 | 2.32 | 0.9 | 32.25 | 12.69 | 0.88 | 0.35 |

| 12 | 2.89 | 1.31 | 16.75 | 13.89 | 0.65 | 0.56 | |

| 18 | 1.91 | 0.26 | 0 | 04.00 | 0 | 0 | |

| 23 | 2.01 | 0.93 | 21.25 | 15.84 | 0.69 | 0.46 | |

| 26 | 2.85 | 0.63 | 17.50 | 5.00 | 0.52 | 0.20 | |

| 35 | 1.79 | 0.25 | 19.67 | 1.89 | 0.56 | 0.06 | |

| 42 | 2.83 | 1.39 | 3.75 | 1.50 | 0.11 | 0.05 | |

| 43 | 2.89 | 0.43 | 20.67 | 1.25 | 0.77 | 0.02 | |

| 55 | 2.89 | 0.88 | 26.25 | 14.68 | 0.79 | 0.41 | |

| 83 | 2.02 | 1.01 | 29.50 | 19.94 | 0.81 | 0.52 | |

| 114 | 2.44 | 0.29 | 0.50 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| 119 | 2.02 | 0.35 | 2.75 | 2.22 | 0.07 | 0.06 | |

| 1b | 3.39 | 0.37 | 22.00 | 6.48 | 0.79 | 0.19 | |

| 78b | 2.70 | 0.67 | 30.25 | 14.73 | 0.87 | 0.35 | |

| Bingo | 2.69 | 0.49 | 43.00 | 16.59 | 0.99 | 0.29 | |

| F-ANOVA | 0.149 | 0.003 | 0.006 | ||||

| LSD0.05 | 1.311 | 17.6 | 0.511 | ||||

| Trait | t [1] | t [2] | t [3] | t [4] | t [5] | t [6] | t [7] | t [8] | t [9] | t [10] | t [11] | t [12] | t [13] | t [14] | t [15] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t [1] | 1.00 | −0.10 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.72 | −0.31 | −0.12 | 0.03 | −0.08 | −0.31 | 0.27 | 0.54 | 0.50 |

| t [2] | −0.17 | 1.00 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.20 | −0.45 | 0.73 | −0.30 | −0.21 | −0.28 | −0.28 | 0.14 | −0.19 | −0.20 |

| t [3] | −0.08 | −0.21 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.99 | 0.93 | −0.26 | −0.20 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.25 | −0.31 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| t [4] | 0.03 | −0.14 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.87 | −0.19 | −0.07 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.22 | −0.28 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.02 |

| t [5] | −0.05 | −0.19 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.93 | −0.25 | −0.16 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.24 | −0.30 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| t [6] | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 1.00 | −0.27 | −0.10 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.15 | −0.30 | 0.23 | −0.03 | −0.03 |

| t [7] | 0.41 | −0.06 | −0.24 | −0.23 | −0.24 | −0.05 | 1.00 | −0.51 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.56 | 0.48 |

| t [8] | −0.17 | 0.70 | −0.19 | −0.11 | −0.17 | −0.03 | 0.32 | 1.00 | −0.25 | −0.18 | −0.24 | 0.09 | −0.20 | −0.35 | −0.42 |

| t [9] | 0.03 | −0.28 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.42 | −0.44 | −0.37 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.99 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.28 |

| t [10] | −0.37 | −0.38 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.29 | −0.48 | −0.29 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.54 | −0.25 | 0.28 | 0.30 |

| t [11] | −0.10 | −0.32 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.40 | −0.47 | −0.36 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.56 | −0.07 | 0.25 | 0.29 |

| t [12] | −0.01 | −0.42 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.03 | −0.24 | 0.65 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 1.00 | −0.28 | −0.13 | −0.14 |

| t [13] | 0.18 | −0.22 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.24 | 0.24 | −0.09 | −0.03 | −0.19 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 0.21 | 0.33 |

| t [14] | 0.41 | −0.26 | −0.31 | −0.26 | −0.30 | −0.36 | 0.53 | 0.19 | −0.36 | −0.38 | −0.38 | −0.06 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 0.96 |

| t [15] | 0.43 | −0.28 | −0.30 | −0.24 | −0.28 | −0.35 | 0.58 | 0.18 | −0.33 | −0.36 | −0.35 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.97 | 1.00 |

| * | ** | *** |

| Trait | V1 | V2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First day of drought (20% RWC) | Soluble sugar content | −0.1861 | 0.2337 |

| Phenolic compound content | 0.347 | 0.6147 *** | |

| Chlorophyll a content | 0.5851 *** | −0.2591 | |

| Chlorophyll b content | 0.636 *** | −0.1393 | |

| Chlorophyll a and b content | 0.6095 *** | −0.2274 | |

| Carotenoid content | 0.6673 *** | −0.0698 | |

| After two weeks of drought (20% RWC) | Soluble sugar content | −0.3643 * | 0.563 ** |

| Phenolic compound content | 0.0333 | 0.6846 *** | |

| Chlorophyll a content | 0.0666 | −0.5201 ** | |

| Chlorophyll b content | 0.059 | −0.4195 * | |

| Chlorophyll a and b content | 0.0665 | −0.5071 ** | |

| Carotenoid content | −0.1082 | −0.1136 | |

| At the stage of grains’ full maturity | The mass of stems/plant | −0.3278 | −0.4786 ** |

| The number of grains | −0.7358 *** | 0.0131 | |

| The mass of grains/plant | −0.7288 *** | −0.0991 | |

| Percentage of explained variation | 26.53 | 20.75 | |

| Control | Drought Stress | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gen. | 9 | 12 | 18 | 23 | 26 | 35 | 42 | 43 | 55 | 83 | 114 | 119 | 1b | 78b | Bingo | 9 | 12 | 18 | 23 | 26 | 35 | 42 | 43 | 55 | 83 | 114 | 119 | 1b | 78b | Bingo | |

| Control | 9 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 4.57 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | 7.86 | 6.45 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 | 4.69 | 2.33 | 7.40 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26 | 6.70 | 3.51 | 6.37 | 3.85 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 35 | 7.86 | 7.53 | 7.31 | 6.88 | 8.26 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 42 | 7.33 | 8.27 | 7.48 | 7.63 | 7.66 | 6.56 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 43 | 4.22 | 4.80 | 5.47 | 5.12 | 4.85 | 7.77 | 6.16 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 55 | 8.12 | 6.72 | 5.77 | 6.28 | 6.21 | 5.22 | 6.57 | 6.63 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 83 | 5.19 | 3.95 | 7.43 | 3.50 | 5.62 | 6.61 | 7.98 | 5.73 | 5.80 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 114 | 6.74 | 6.65 | 4.67 | 6.61 | 6.36 | 6.24 | 5.82 | 4.98 | 4.52 | 5.82 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 119 | 8.33 | 7.27 | 5.27 | 7.02 | 6.18 | 7.54 | 7.69 | 5.87 | 4.64 | 6.93 | 3.96 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1b | 7.04 | 5.39 | 4.69 | 6.44 | 4.38 | 8.32 | 7.94 | 4.30 | 5.69 | 6.56 | 5.24 | 5.03 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 78b | 3.06 | 4.37 | 7.10 | 4.92 | 5.65 | 8.71 | 7.77 | 4.07 | 8.14 | 5.88 | 6.03 | 7.39 | 6.07 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| Bingo | 4.26 | 3.47 | 7.26 | 2.59 | 4.69 | 7.67 | 7.42 | 4.40 | 7.35 | 4.09 | 6.44 | 6.83 | 6.75 | 4.47 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| Drought stress | 9 | 3.22 | 5.88 | 7.30 | 5.61 | 7.05 | 7.33 | 5.17 | 3.93 | 7.95 | 6.21 | 6.23 | 8.16 | 7.47 | 4.75 | 4.58 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||

| 12 | 6.60 | 4.62 | 6.32 | 3.63 | 4.37 | 6.59 | 7.03 | 5.30 | 6.06 | 5.08 | 5.82 | 5.41 | 6.43 | 6.32 | 3.16 | 6.08 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||

| 18 | 6.27 | 6.28 | 4.18 | 6.53 | 6.35 | 6.82 | 5.76 | 3.96 | 5.80 | 6.69 | 5.08 | 5.05 | 4.90 | 6.36 | 5.84 | 5.37 | 5.38 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||

| 23 | 6.06 | 4.98 | 7.26 | 4.38 | 5.64 | 7.55 | 7.03 | 5.89 | 7.69 | 5.51 | 7.15 | 7.37 | 7.57 | 6.37 | 3.03 | 5.29 | 3.23 | 5.73 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||

| 26 | 5.24 | 5.54 | 5.74 | 4.75 | 5.50 | 5.40 | 4.75 | 4.09 | 5.56 | 5.83 | 4.45 | 5.13 | 6.16 | 5.08 | 4.28 | 4.29 | 3.79 | 4.12 | 4.63 | 0.00 | |||||||||||

| 35 | 7.30 | 6.98 | 6.71 | 7.00 | 7.75 | 5.16 | 6.24 | 6.86 | 6.55 | 6.04 | 6.14 | 7.87 | 7.38 | 8.30 | 6.80 | 6.09 | 6.17 | 5.85 | 5.79 | 6.06 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| 42 | 7.95 | 8.65 | 7.84 | 7.78 | 8.39 | 5.30 | 2.79 | 7.04 | 6.31 | 7.91 | 5.92 | 7.75 | 8.58 | 8.62 | 7.71 | 5.85 | 6.71 | 6.18 | 7.22 | 5.02 | 5.36 | 0.00 | |||||||||

| 43 | 4.88 | 4.39 | 4.79 | 4.40 | 4.17 | 6.77 | 6.15 | 2.11 | 5.67 | 5.39 | 4.65 | 4.85 | 4.34 | 4.49 | 3.94 | 4.65 | 4.12 | 3.69 | 5.16 | 2.91 | 6.72 | 6.87 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| 55 | 8.21 | 7.36 | 6.24 | 7.37 | 7.47 | 4.03 | 5.80 | 7.44 | 4.99 | 6.32 | 5.02 | 7.22 | 7.12 | 8.52 | 7.92 | 7.46 | 6.92 | 6.60 | 7.52 | 6.15 | 4.01 | 5.34 | 6.88 | 0.00 | |||||||

| 83 | 5.49 | 5.27 | 6.82 | 4.53 | 6.84 | 5.43 | 6.82 | 6.12 | 6.60 | 4.93 | 5.75 | 7.67 | 8.17 | 6.07 | 4.58 | 4.89 | 4.71 | 6.72 | 5.14 | 4.46 | 5.82 | 6.24 | 5.42 | 6.31 | 0.00 | ||||||

| 114 | 7.13 | 8.74 | 8.18 | 8.23 | 8.89 | 7.20 | 6.49 | 5.67 | 8.38 | 8.84 | 7.27 | 7.86 | 8.06 | 7.84 | 7.58 | 5.80 | 7.27 | 5.45 | 8.16 | 5.33 | 7.54 | 5.86 | 5.98 | 8.54 | 7.74 | 0.00 | |||||

| 119 | 6.31 | 6.30 | 5.49 | 6.15 | 6.00 | 6.90 | 6.00 | 4.13 | 6.96 | 6.80 | 5.17 | 5.18 | 5.71 | 5.91 | 4.90 | 5.17 | 4.06 | 3.34 | 4.68 | 3.14 | 5.82 | 6.04 | 3.61 | 6.93 | 6.17 | 4.90 | 0.00 | ||||

| 1b | 5.04 | 4.69 | 5.15 | 4.13 | 4.65 | 5.54 | 4.75 | 3.28 | 4.05 | 4.85 | 4.22 | 4.94 | 4.98 | 5.40 | 4.38 | 4.36 | 4.08 | 3.64 | 5.19 | 2.83 | 5.75 | 5.12 | 2.61 | 5.76 | 4.73 | 5.82 | 4.42 | 0.00 | |||

| 78b | 3.36 | 5.36 | 7.40 | 5.08 | 6.21 | 7.89 | 5.61 | 3.40 | 7.88 | 5.70 | 6.33 | 7.72 | 6.72 | 4.29 | 3.82 | 2.27 | 5.48 | 4.92 | 4.70 | 4.24 | 6.32 | 6.31 | 4.26 | 7.82 | 5.55 | 5.76 | 4.48 | 4.32 | 0.00 | ||

| Bingo | 5.62 | 5.76 | 8.33 | 4.86 | 7.56 | 6.43 | 7.84 | 7.30 | 8.15 | 5.87 | 7.28 | 8.33 | 9.14 | 6.07 | 4.47 | 5.66 | 4.89 | 7.30 | 4.37 | 4.90 | 6.63 | 7.28 | 6.54 | 7.64 | 3.71 | 8.21 | 6.15 | 6.16 | 5.84 | 0.00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Warzecha, T.; Warchoł, M.; Bathelt, R.; Bocianowski, J.; Idziak-Helmcke, D.; Sutkowska, A.; Skrzypek, E. Evaluation of Drought Tolerance in Oat × Maize Addition Lines Through Biochemical and Yield Traits. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2259. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102259

Warzecha T, Warchoł M, Bathelt R, Bocianowski J, Idziak-Helmcke D, Sutkowska A, Skrzypek E. Evaluation of Drought Tolerance in Oat × Maize Addition Lines Through Biochemical and Yield Traits. Agronomy. 2025; 15(10):2259. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102259

Chicago/Turabian StyleWarzecha, Tomasz, Marzena Warchoł, Roman Bathelt, Jan Bocianowski, Dominika Idziak-Helmcke, Agnieszka Sutkowska, and Edyta Skrzypek. 2025. "Evaluation of Drought Tolerance in Oat × Maize Addition Lines Through Biochemical and Yield Traits" Agronomy 15, no. 10: 2259. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102259

APA StyleWarzecha, T., Warchoł, M., Bathelt, R., Bocianowski, J., Idziak-Helmcke, D., Sutkowska, A., & Skrzypek, E. (2025). Evaluation of Drought Tolerance in Oat × Maize Addition Lines Through Biochemical and Yield Traits. Agronomy, 15(10), 2259. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102259