Managing Digital Presence in Wineries Practicing Heroic Agriculture: The Cases of Ribeira Sacra and Lanzarote (Spain)

Abstract

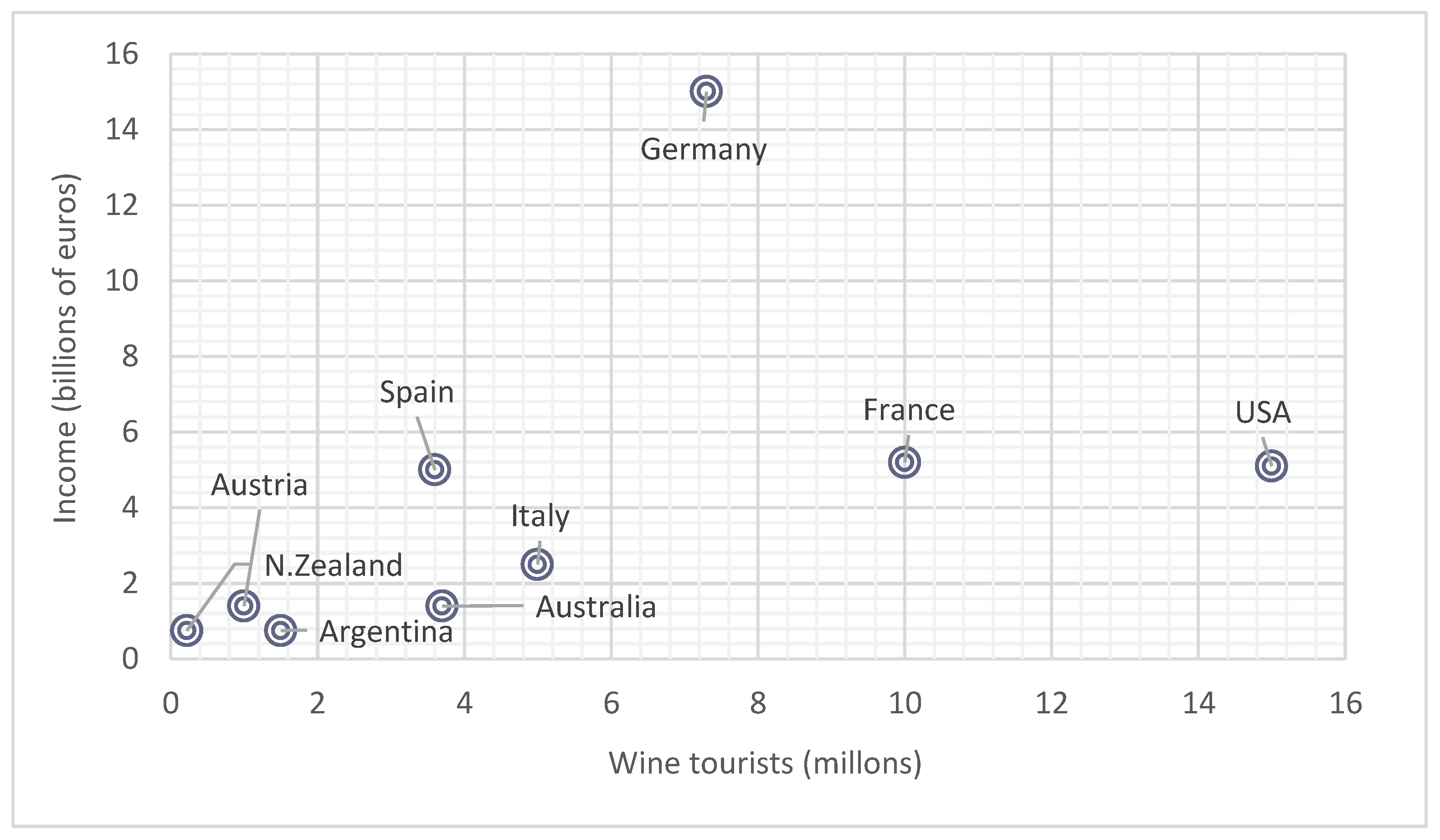

1. Introduction

- RQ1

- What does the digital presence of Ribeira Sacra wineries and Lanzarote wineries contribute to the development of the product and the rural environment?

- RQ2

- Are there values that bring us closer to a communication model of wineries through their digital presence on Instagram?

- RQ3

- Is the management of digital media used to promote the terroir adequate?

2. State of the Art

2.1. The Wine Landscape and Terroir

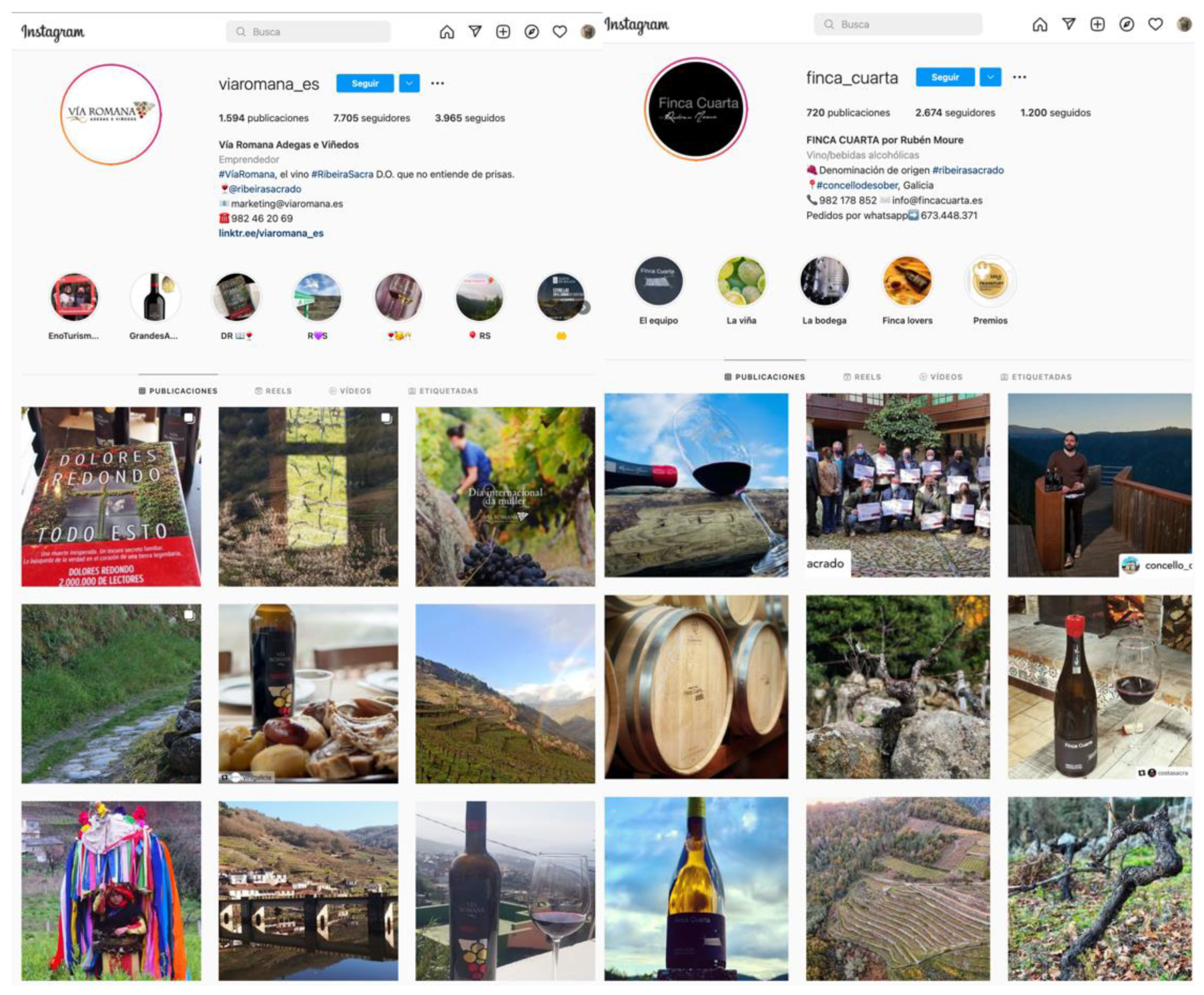

2.2. Wineries and Digital Culture

3. Methodology

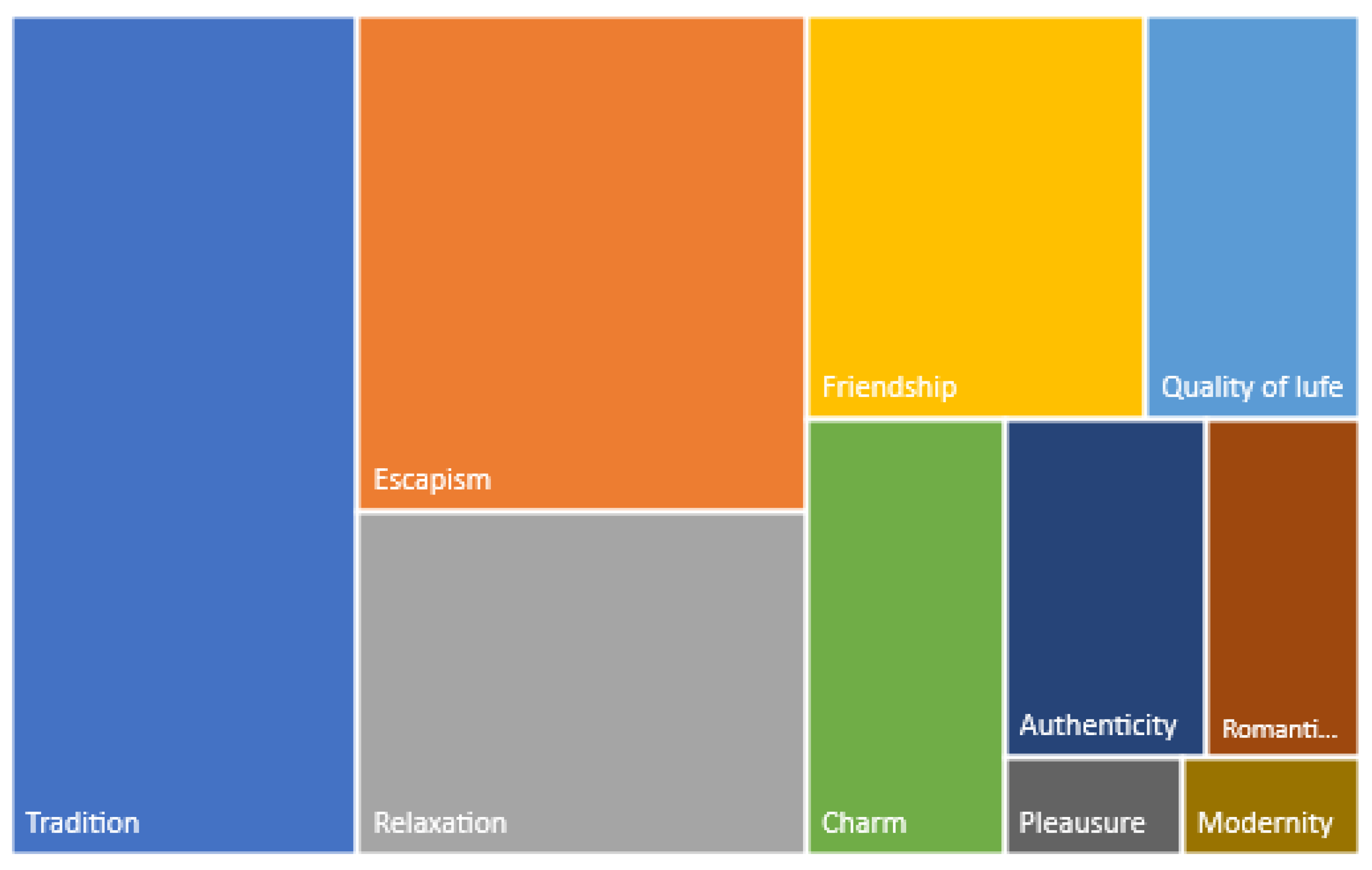

4. Results

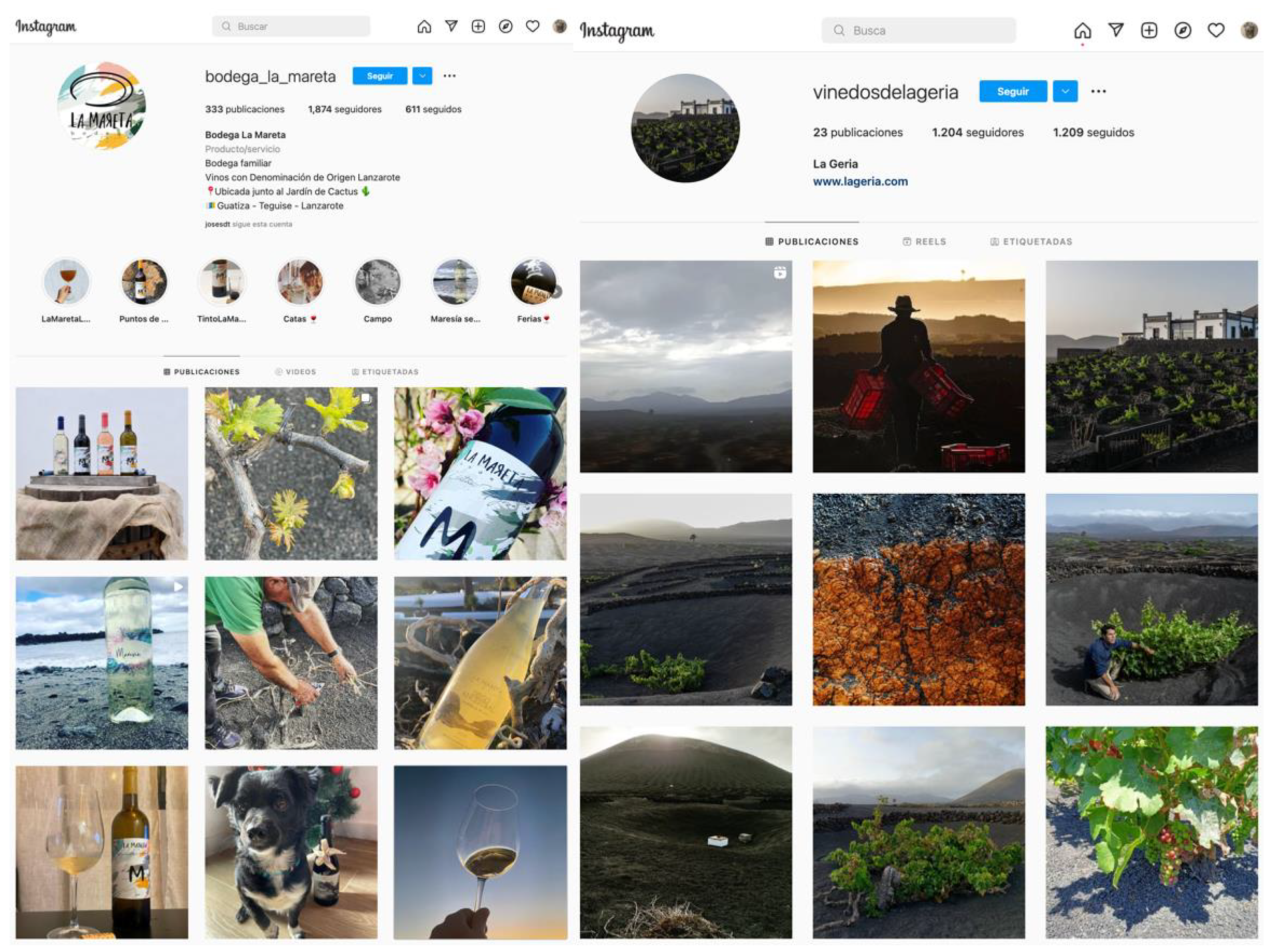

4.1. Internet Presence

4.1.1. Ribeira Sacra AO

4.1.2. Lanzarote AO

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Seguin, G. “Terroirs” and pedology of wine growing. Experientia 1986, 42, 861–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Explore Wine Tourism, Management, Development and Destinations; Cognizant Communication Corporation: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe, B.; Lee, S. Conceptualizing terroir wine tourism. Tour. Rev. Int. 2018, 22, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, G.; Shams, S.M.R.; Metallo, G.; Cuomo, M.T. Opportunities and challenges in the contribution of wine routes to wine tourism in Italy—A stakeholders’ perspective of development. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Ruiz, E.; Zamarreño-Aramendia, G.; Ruiz-Romero de la Cruz, E. Key Elements for the Design of a Wine Route. The Case of La Axarquía in Málaga (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D. Rural Food and Wine Tourism in Canada’s South Okanagan Valley: Transformations for Food Sovereignty? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sanjosé, M.L.; Gómez-Miguel, V.; Sotés, V. La Cultura del Vino, motor del desarrollo sostenible de las regiones vitivinícolas. Bio Web Conf. 2017, 9, 4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, P.A.; Dans, E.P. The ‘terroirist’ social movement: The reawakening of wine culture in Spain. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 61, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Mitchell, R. Gastronomy, Food and Wine Tourism. In Tourism Business Frontiers; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte Alonso, A.; Martens, W.; Ong, J.L.T. Food tourism development in wine regions: Perspectives from the supply side. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 1968–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. The synergy of wine and culture: The case of Ariousios wine, Greece. In Management and Marketing of Wine Tourism Business: Theory, Practice, and Cases; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Capello, A.; El Turismo Enogastronómico y la Empresa Agroturística. Estrategia de Diversificación de las Explotaciones Agrarias y Herramienta de Desarrollo Local. BS Thesis, Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales. 2020. Available online: https://udimundus.udima.es/handle/20.500.12226/870 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- López-Guzmán, T.; Millán Vázquez de la Torre, G.; Caridad y Ocerín, J.M. Análisis econométrico del enoturismo en España: Un estudio de caso. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2008, 17, 98–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zamarreño Aramendia, G.; Ruiz Romero de la Cruz, E.; Cruz Ruiz, E. The developement of oenological route of Malaga from Demand Side. In Proceedings of the Destinations Past, Present and Future, Atlas Association for Tourism and Leisure Education and Research, Viana do Castelo, Portugal, 12–16 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, B.; Fernández, R. Vino, turismo e innovación: Las Rutas del Vino de España, una estrategia integrada de desarrollo rural. Estud. Econ. Apl. 2011, 29, 5–35. [Google Scholar]

- Simeone, M.; Russo, C.; Scarpato, D. Price Quality Cues in Organic Wine Market: Is There a Veblen Effect? Agronomy 2023, 13, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbulú, I.; Razumova, M.; Rey-Maquieira, J.; Sastre, F. Can domestic tourism relieve the COVID-19 tourist industry crisis? The case of Spain. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100568. [Google Scholar]

- Marco-Lajara, B.; Seva-Larrosa, P.; Ruiz-Fernández, L.; Martínez-Falcó, J. The Effect of COVID-19 on the Spanish Wine Industry. In Impact of Global Issues on International Trade; Özer, A.C., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, J.; Compés, R.; Faria, S.; Gonçalves, T.; Pinilla, V.; Simón-Elorz, K. COVID-19 lockdown and wine consumption frequency in Portugal and Spain. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 19, e0105R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Agnoli, L.; Cardebat, J.-M.; Compés, R.; Faye, B.; Frick, B.; Gaeta, D.; Giraud-Héraud, E.; Le Fur, E.; Livat, F.; et al. Did wine consumption change during the COVID-19 lockdown in France, Italy, Spain, and Portugal? J. Wine Econ. 2021, 16, 131–168. [Google Scholar]

- Zeler, I.; Oliveira, A.; Malaver, S. La gestión comunicativa de las empresas vitivinícolas de España en las principales redes sociales/Communication management of Spanish wine companies in the main social networks. Rev. Int. Relac. Públicas 2019, 9, 161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, M.C.C.; Pulpón, Á.R.R. Paisajes del viñedo, turismo y sostenibilidad: Interrelaciones teóricas y aplicadas. Investig. Geográficas 2020, 74, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelló, E. The will for terroir: A communicative approach. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 86, 386–397. [Google Scholar]

- Aramendia, G.Z.; Ruiz, E.C.; Nieto, C.H. La digitalización de la experiencia enoturística: Una revisión de la literatura y aplicaciones prácticas. Doxa Comun. 2021, 33, 257–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CERVIM. Heroic Viticulture. Centre for Research, Environmental Sustainability, and Advancement of Mountain Viticulture (CERVIM). Available online: http://www.cervim.org/en/heroic-viticulture.aspx (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- De Uña-Álvarez, E.; Villarino-Pérez, M. Enlazando cultura del vino, identidad, turismo y desarrollo rural en un territorio con Denominación de Origen (Noroeste de España). Cuad. Tur. 2019, 44, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Varela, S. Estrategias territoriales integrales para la puesta en valor de paisaje cultural agrícola. La Ribeira Sacra, Galicia, España. Proy. Prog. Arquit. 2019, 21, 52–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, S.; González, A.; Ramón, A. El paisaje vinícola como recurso turístico y territorial en Lanzarote (Canarias, España). Ería 2017, 3, 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Zottele, F.; Santana, A.G. “Faraway, So Close!”: The Landscapital Proof-of-Concept Applied of the Terraced Landscapes of the Canary Islands (Spain) and of Val di Cembra (Italian Alps). Vegueta Anu. Fac. Geogr. Hist. 2021, 21, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristófol, F.J.; Aramendia, G.Z.; de-San-Eugenio-Vela, J. Effects of social media on enotourism. Two cases study: Okanagan Valley (Canada) and Somontano (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Correo Gallego. Mil Años de Vino en Ribeira Sacra. 17 February 2020. Available online: https://www.elcorreogallego.es/hemeroteca/mil-anos-vino-ribeira-sacra-FTCG1230577 (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Gómez-Encinas, L.; Martínez-Moure, O. Recursos turísticos sostenibles en la Ribeira Sacra tras la pandemia global methaodos. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2020, 211–226. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeira Sacra. Ribeira Sacra [Fotografía]. La D.O. Ribeira Sacra Despide el Mejor año de su Historia. 30 December 2019. Available online: https://elcorreodelvino.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/BURDEOS-LONDON_2PEQ-002.jpg (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- D.O. Lanzarote. 10 June 2020. Available online: https://dolanzarote.com/vino/lanzarote (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Curiel, J.E.; Sánchez, V.E.; Antonovica, A.; Aranda, E.; Pineda, H.A.Y.; Gómez, M.L. Turismo Gastronómico y Enológico; Dykinson S.L: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez García, J.; López Guzmán, T.; Cañizarez Ruiz, S.M.; Jiménez García, M. Turismo del Vino en el Marco de Jerez. Un Análisis Desde la Perspectiva de la Oferta. Cuad. Tur. 2010, 217–234. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/116351 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Rita, P.Y.; Moro, S. Tasting the Port wine cellar experience: What features please the most? J. Wine Res. 2022, 33, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caamaño Franco, I.; Pérez García, A.; Martínez Iglesias, S. La enogastronomíacomo motivación de viaje. Caso de estudio: Rías Baixas (Pontevedra, España). J. Tour. Herit. Res. 2020, 3, 56–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, M.; Haller, C. The impact of social media on the behavior of wine tourists: A typology of power sources. In Management and Marketing of Wine Tourism Business: Theory, Practice, and Cases; Sigala, M., Robinson, R.N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; ISBN 9783319754628. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, M.; Christou, E.; Gretzel, U. Social Media in Travel, Tourism and Hospitality: Theory, Practice and Cases; Sigala, M., Christou, E., Gretzel, U., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing: Surrey, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Belias, D.; Velissariou, E.; Kyriakou, D.; Vasiliadis, L.; Mantas, C.; Sdrolias, L.; Aspridis, G.; Kakkos, N. The Importance of Customer Relationship Management and Social Media in the Greek Wine Tourism Industry. In Innovative Approaches to Tourism and Leisure; Katsoni, V., Velander, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, M.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. Interaction as a Central Element of Co-Creative Wine Tourism Experiences—Evidence from Bairrada, a Portuguese Wine-Producing Region. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canovi, M.; Pucciarelli, F. Social media marketing in wine tourism: Winery owners’ perceptions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, B. The Classification System in Burgundy. Decanter. Available online: https://jeroboams.co.uk/advice-centre/buyers-guide/burgundy-wine-classification-guide/#:~:text=View%20here-,Four%20tier%20classification,always%20different%20to%20one%20another (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- International Organisation of Vine and Wine. “RESOLUCIÓN OIV/VITI 333/2010”. 2010. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/380/viti-2010-1-es.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Seguin, G. Ecosystems of the great red wines produced in the maritime climate of Bordeaux. In The Symposium on Maritime Climate Winegrowing; Department of Horticultural Sciences, Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 36–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bérard, L.; Cegarra, M.; Djama, M.; Louafi, S.; Marchenay, P.; Roussel, B.; Verdeaux, F. Savoirs et savoir-faire naturalistes locaux: L’originalité française. VertigO Rev. Électronique Sci. Environ. 2005, 6. Available online: https://agritrop.cirad.fr/530567/1/document_530567.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Demossier, M. Beyond terroir: Territorial construction, hegemonic discourses, and French wine culture. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2011, 17, 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iland, P.; Gago, P. Australian Wine: From the Vine to the Glass; Patrick Iland Wine Promotions: Adelaide, Australia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.; Harding, J. The Oxford Companion to Wine; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, C. Terroir: The effect of the physical environment on vine growth, grape ripening and wine sensory attributes. Manag. Wine Qual. 2022, 9, 341–393. [Google Scholar]

- Falcetti, M. Le Terroir. Qu’est-ce qu’un Terroir? Pourquoi l’étudier? Pourquoi l’enseigner? Bull. l’OIV 1994, 67, 246–275. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, A.P.; Díaz, M.V.; Chao, R.B. Pleistocene Glaciation in Spain. Quartenary Glaciations-Extent and Chronology; Ehlers, J., Gibbard, P.L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 2, pp. 390–394. [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius, I.S. Tasting the terroir of wine yeast innovation. FEMS Yeast Res. 2020, 20, foz084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stupino, M.; Giacosa, E.; Pollifroni, M. Tradition and innovation within the wine sector: How a strong combination could increase the company’s competitive advantage. In Processing and Sustainability of Beverages; Grumezescu, A., Holban, A.-M., Eds.; Woodhead: Sawston, UK, 2019; pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Portela, J.; Pardo-Abad, C.J. Las plataformas digitales en el desarrollo del enoturismo en Castilla y León: Páginas web y redes sociales. Cuad. Tur. 2020, 46, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeri, M.; Baggio, R. Social network analysis: Organizational implications in tourism management. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2020, 29, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasén, A.; Puente, H. La cultura digital. López Gómez Daniel Tecnol. Soc. Comun. Mater. Docentes UOC Módulo Didáctico 2016, 3, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Galati, A.; Crescimanno, M.; Tinervia, S.; Fagnani, F. Social media as a strategic marketing tool in the Sicilian wine industry: Evidence from Facebook. Wine Econ. Policy 2017, 6, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, T.; Casprini, E.; Nosi, C.; Zanni, L. Does social media usage affect online purchasing intention for wine? The moderating role of subjective and objective knowledge. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egaña, F.; Pezoa-Fuentes, C.; Roco, L. The Use of Digital Social Networks and Engagement in Chilean Wine Industry. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1248–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chironi, S.; Altamore, L.; Columba, P.; Bacarella, S.; Ingrassia, M. Study of Wine Producers’ Marketing Communication in Extreme Territories–Application of the AGIL Scheme to Wineries’ Website Features. Agronomy 2020, 10, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sottini, V.A.; Barbierato, E.; Bernetti, I.; Capecchi, I.; Fabbrizzi, S.; Menghini, S. Winescape perception and big data analysis: An assessment through social media photographs in the Chianti Classico region. Wine Econ. Policy 2019, 8, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Prayag, G. Wine tourism: Moving beyond the cellar door? Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2017, 29, 338–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. Relationships among Source Credibility of Electronic Word of Mouth, Perceived Risk, and Consumer Behavior on Consumer Generated Media. 2013. Available online: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2123&context=theses (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Jalilvand, M.R.; Samiei, N. The effect of electronic word of mouth on brand image and purchase intention: An empirical study in the automobile industry in Iran. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2012, 30, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Sung, H. Travel destination websites: Cross-cultural effects on perceived information value and performance evaluation. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.; Holland, S.; Jun, S.H.; Gibson, H. Enhancing destination image through travel website information. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llodrà-Riera, I.; Llodrà-Riera, I.; Martínez-Ruiz, M.P.; Jiménez-Zarco, A.I. A multidimensional analysis of the information sources construct and its relevance for destination image formation. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinillo, S.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Buhalis, D. DMO online platforms: Image and intention to visit. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Gerritsen, R. What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 10, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Huang, C.R.; Yang, K.C. eWOM: The effects of online consumer information adoption on purchasing decision. In Proceedings of the 2011 10th Internarional Marketing Trends Conference, Paris, France, 20–22 January 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, T.H. Attracting repeat customers to wineries. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1999, 11, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, R.; Goodman, S. Succeeding on social media: Exploring communication strategies for wine marketing. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 33, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, M.T.; Tortora, D.; Festa, G.; Giordano, A.; Metallo, G. Exploring consumer insights in wine marketing: An ethnographic research on# Winelovers. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar]

- IAB Spain. Estudio de Redes Sociales 2021. IAB Web Page. Available online: https://iabspain.es/estudio/estudio-de-redessociales-2021/ (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Wimmer, R.D.; Dominick, J.R. La Investigación Científica de los Medios de Comunicación: Una Introducción a sus Métodos; Editorial Bosch: Barcelona, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hilal, A.H.; Alabri, S.S. Using Nvivo For Data Analysis In Qualitative Research. Int. Interdiscip. J. Educ. 2013, 2, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce de León Elizondo, A.; Valdemoros San Emeterio, M.A.; Sanz, E. Fundamentos en el manejo del NVIVO 9 como herramienta al servicio de estudios cualitativos. Context. Educ. Rev. Educ. 2011, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas Roig, A. El Community Manager y la Comunicación de los Valores de Marca de Destino a Través de los Medios Sociales; Universitat Rovira i Virgili: Tarragona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Obermayer, N.; Kővári, E.; Leinonen, J.; Bak, G.; Valeri, M. How social media practices shape family business performance: The wine industry case study. Eur. Manag. J. 2022, 40, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigon, B. Grape/Wine Marketing with New Media and Return of the Boomer. Pract. Winery Vineyard J. Winter 2011. Available online: http://www.practicalwinery.com/winter2011/marketing1.htm (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Pijet-Migoń, E.; Migoń, P. Linking wine culture and geoheritage—Missing opportunities at European UNESCO World Heritage sites and in UNESCO Global Geoparks? A survey of web-based resources. Geoheritage 2021, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Alant, K. The hedonic nature of wine tourism consumption: An experiential view. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Rueger-Muck, E. Wine tourism and hedonic experience: A motivation-based experiential view. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Brown, G. Critical Success Factors for Wine Tourism Regions: A Demand Analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Romero de la Cruz, E.; Cruz-Ruiz, E.; Zamarreño-Aramendia, G. Rutas Enológicas y Desarrollo Local. Presente y Futuro en La Provincia de Málaga. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2017, 3, 283–310. [Google Scholar]

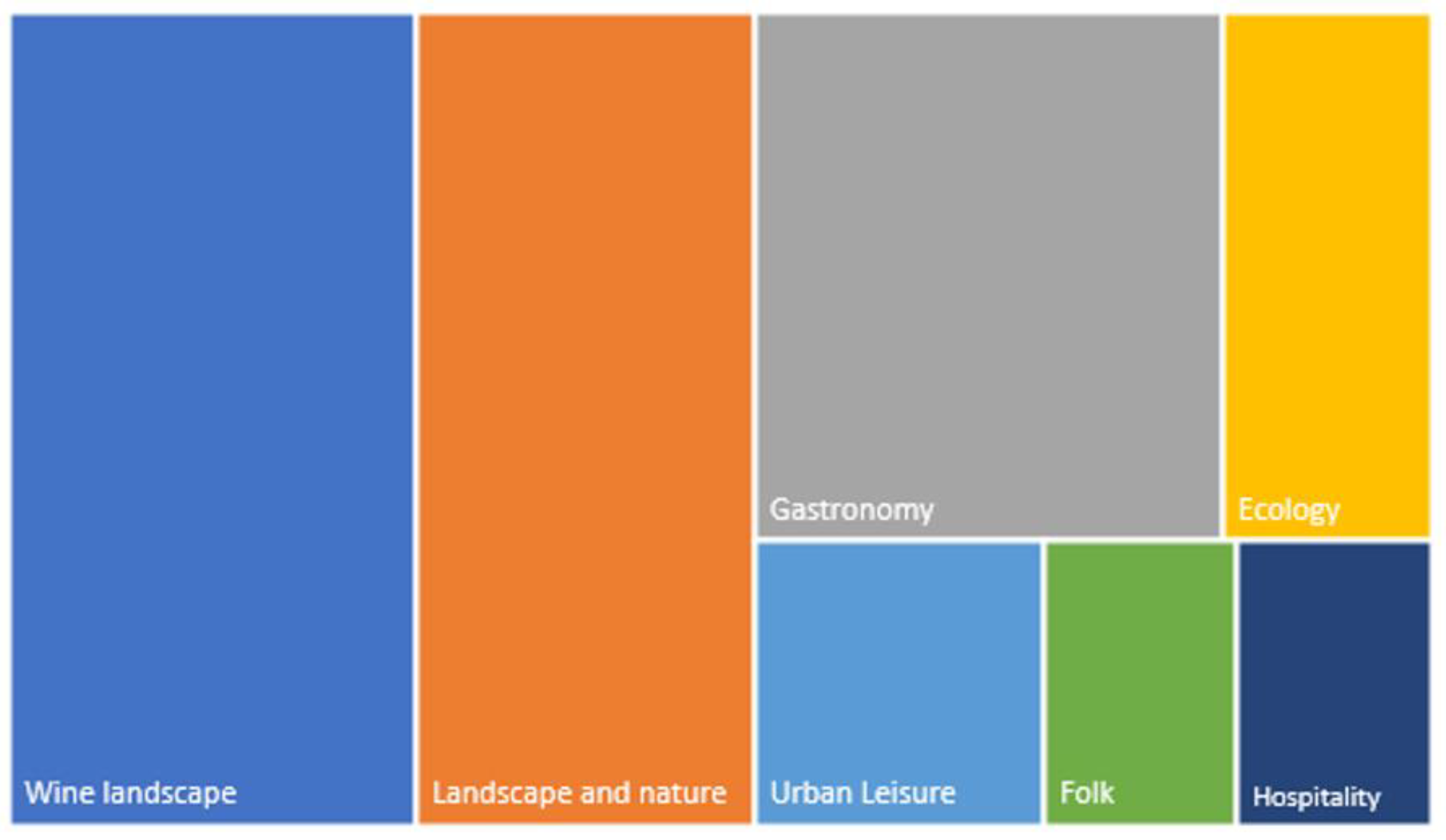

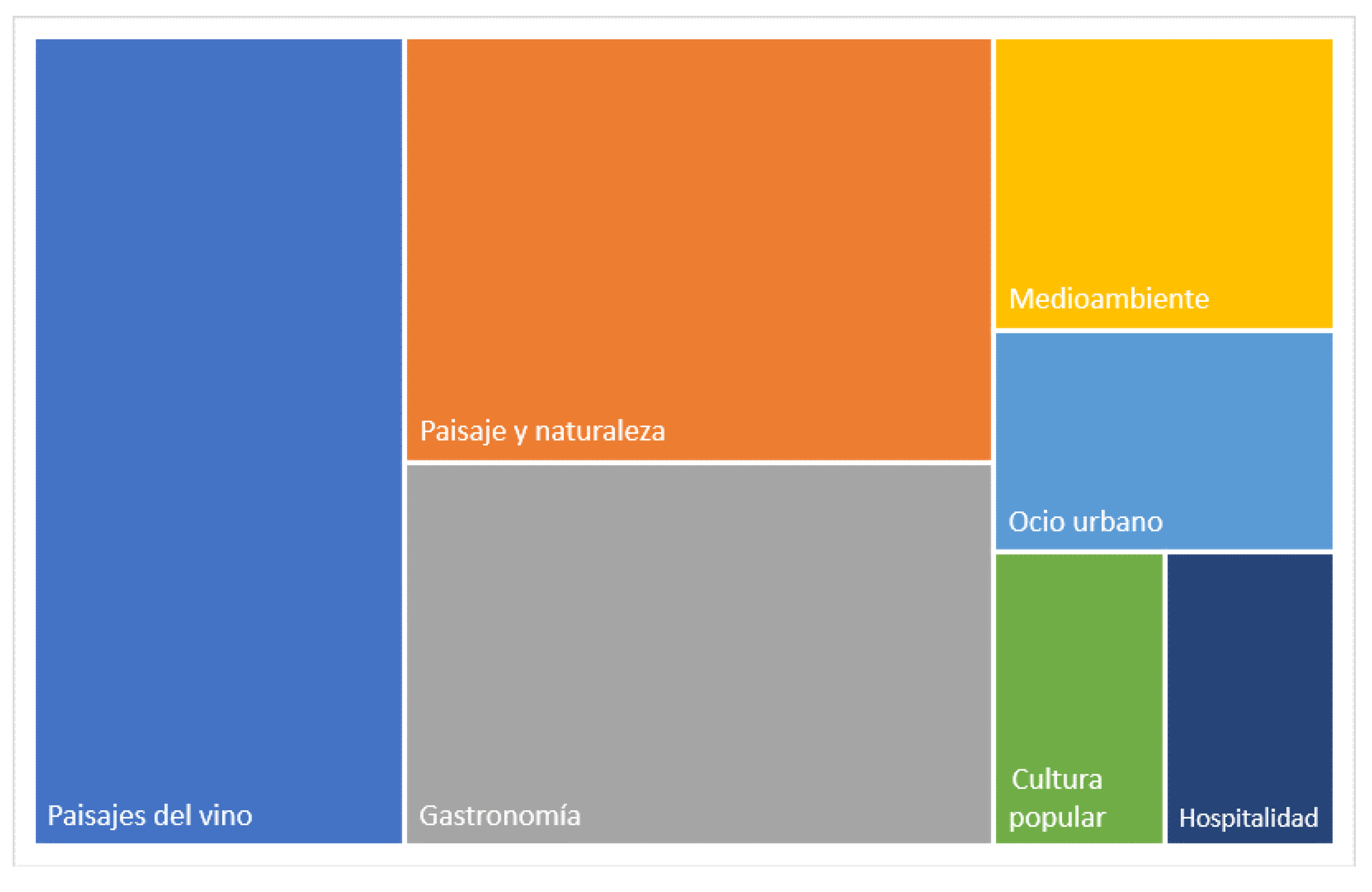

| Tourist Attractions | Emotional Values |

|---|---|

| Landscape and nature | Romanticism |

| Wine landscape | Charm |

| Intangible heritage | Friendship |

| Folk | Escapism |

| Urban landscape | Modernity |

| Urban leisure | Cosmopolitanism |

| Nightlife | Responsibility |

| Shopping | Authenticity |

| Sun and beach | Safety |

| Weather | Joy |

| Gastronomy | Youth |

| Ecology | Dynamism |

| Hospitality | Relaxation |

| Luxury | Tradition |

| Sports as spectacle | Quality of life |

| Sports to practice | Sophistication |

| Plans | Diversity |

| Others | Others |

| Tourist Attractions | Definition |

|---|---|

| Landscape and nature | Presence of landscapes or natural elements |

| Wine landscape | Presence of vineyards, vines, plantations or other elements related to viticulture. |

| Intangible heritage | Non-physical heritage elements |

| Folk | Folkloric manifestations of people |

| Urban landscape | Presence of urban elements (buildings, streets, furniture, etc) |

| Urban leisure | City-related leisure: city bars, museums, etc. |

| Nightlife | Nightlife-related leisure: pubs, clubs, discotheques, etc. |

| Shopping | Presence of elements related to shopping (shopping malls, stores, etc.) |

| Sun and beach | Presence of elements related to sun and beach tourism (sand, beach, beach bars, etc.) |

| Weather | Elements related to the weather (sun, clouds, rain, etc.) |

| Gastronomy | Presence of food or wine dishes |

| Ecology | Elements of environmental care |

| Hospitality | Attitudes that evoke closeness and good treatment |

| Luxury | Appearance of luxury elements: brands, boats, private jets, etc. |

| Sports as spectacle | Celebration of sporting events: soccer, sailing, basketball, etc. to be watched |

| Sports to practice | Celebration of sporting events to be practiced: golf, regattas, etc. |

| Plans | Proposal of leisure plans |

| Others | Everything not included in the above |

| Emotional Values | Definition |

|---|---|

| Romanticism | Evocation of romantic attitudes in a couple |

| Charm | Elements that highlight positive feelings |

| Friendship | Attitudes that evoke the feeling of friendship |

| Escapism | Absence of noise in the images, cleanliness and tranquillity |

| Modernity | Presence of modern elements such as buildings, new technologies, etc. |

| Cosmopolitanism | Presence of different cultural elements or ethnicities |

| Responsibility | Values related to care and attention |

| Authenticity | Presence of values consistent with the reality of the territory |

| Safety | Absence of risk |

| Joy | Existence of elements that show feelings, degrees or gestures and acts that express joy |

| Youth | Presence of elements highlighting actions related to youth |

| Dynamism | Evocation of values related to the activity |

| Relaxation | Appearance of elements that present mental and physical distraction or rest |

| Tradition | Features of a region’s identity |

| Quality of life | Presence of elements that emphasize hedonism |

| Sophistication | Elements that highlight elegant and refined values |

| Diversity | Diversity of sexes, genders, races or religions |

| Others | Everything not included in the above |

| Territory | Total Number of Wineries | With Website | % Website |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ribeira Sacra | 96 | 50 | 52.1% |

| Lanzarote | 21 | 12 | 57.1% |

| Territory | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribeira Sacra | 96 | 43 | 44.8% | 14 | 14.6% | 22 | 22.9% |

| Lanzarote | 21 | 16 | 76.2% | 5 | 23.8% | 14 | 66.7% |

| Territory | Active Websites | Touristic Attractiveness | Emotional Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ribeira Sacra | 47 | Wine Landscape 36 (76.7%) | Tradition 34 (72.4%) |

| Territory | Wineries | Website | % Web |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lanzarote | 12 | Wine landscape, 8 (66.6%) | Tradition, 9 (75%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cruz-Ruiz, E.; Cristòfol, F.J.; Zamarreño-Aramendia, G. Managing Digital Presence in Wineries Practicing Heroic Agriculture: The Cases of Ribeira Sacra and Lanzarote (Spain). Agronomy 2023, 13, 946. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13030946

Cruz-Ruiz E, Cristòfol FJ, Zamarreño-Aramendia G. Managing Digital Presence in Wineries Practicing Heroic Agriculture: The Cases of Ribeira Sacra and Lanzarote (Spain). Agronomy. 2023; 13(3):946. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13030946

Chicago/Turabian StyleCruz-Ruiz, Elena, F. J. Cristòfol, and Gorka Zamarreño-Aramendia. 2023. "Managing Digital Presence in Wineries Practicing Heroic Agriculture: The Cases of Ribeira Sacra and Lanzarote (Spain)" Agronomy 13, no. 3: 946. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13030946

APA StyleCruz-Ruiz, E., Cristòfol, F. J., & Zamarreño-Aramendia, G. (2023). Managing Digital Presence in Wineries Practicing Heroic Agriculture: The Cases of Ribeira Sacra and Lanzarote (Spain). Agronomy, 13(3), 946. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13030946