Numerical Simulation of the Trajectory of UAVs Electrostatic Droplets Based on VOF-UDF Electro-Hydraulic Coupling and High-Speed Camera Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Equipment

2.2. Numerical Simulation of Motion Characteristics of Electrostatic Droplet

2.2.1. Boundary Condition Setting

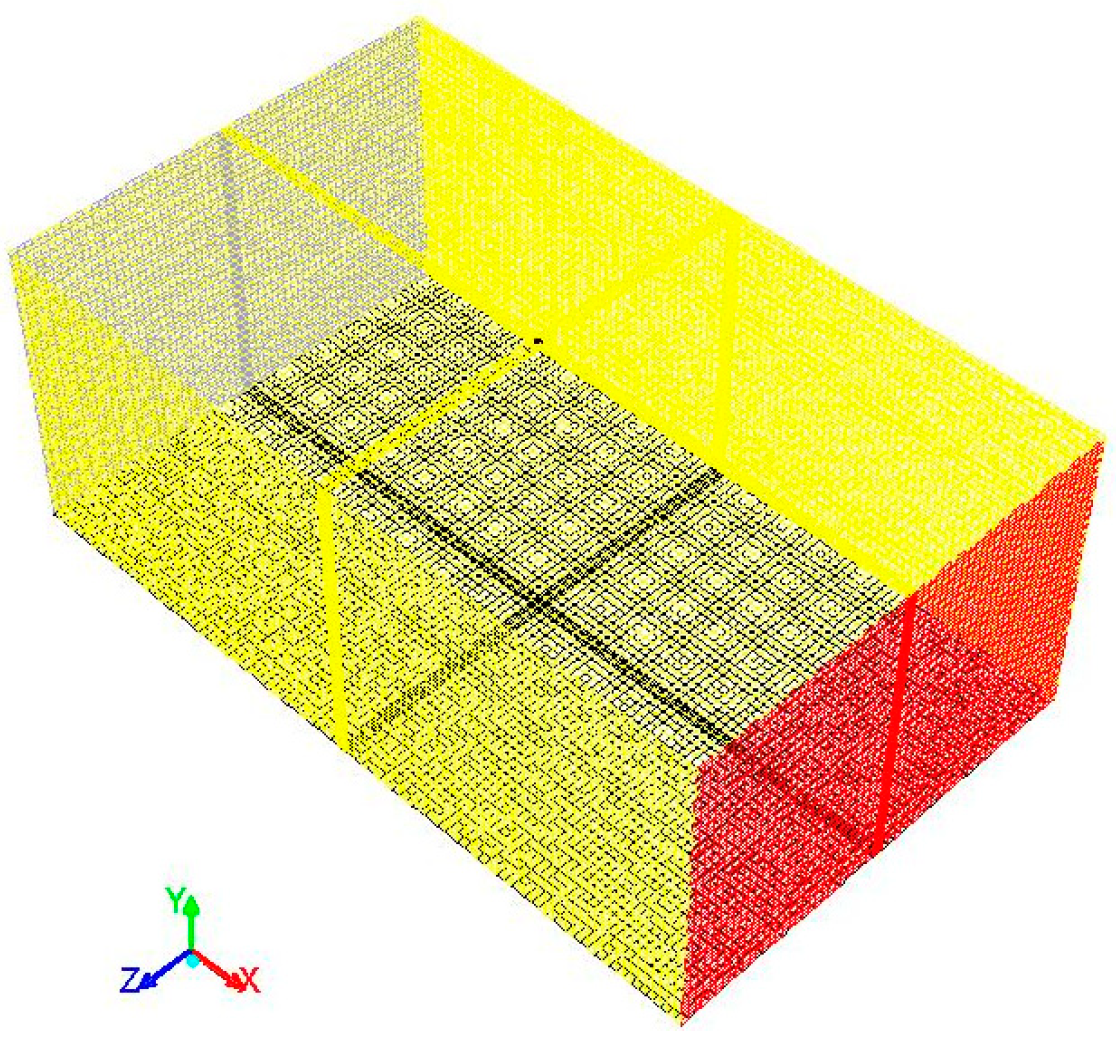

2.2.2. Grid Partitioning

2.2.3. Electric Field UDF Setting

| Algorithm 1 CFD droplet trajectory electric field programming |

| #include “udf.h” |

| #include “dpm.h” |

| #include “sg.h” |

| #include “surf.h” |

| #define q0 2.0/* charge [C]/[Kg] */ |

| DEFINE_ADJUST(calc, domain) |

| { |

| #if !RP_HOST |

| Thread *t; |

| cell_t c; |

| face_t f; |

| thread_loop_c(t,domain) |

| { |

| /* E = -grad(phi) */ |

| C_UDMI(c,t,0) = -C_UDSI_G(c,t,0)[0];/* E_x */ |

| C_UDMI(c,t,1) = -C_UDSI_G(c,t,0)[1];/* E_y */ |

| C_UDMI(c,t,2) = -C_UDSI_G(c,t,0)[2];/* E_z */ |

| } |

| thread_loop_f (t,domain) |

| { |

| if (NULL != THREAD_STORAGE(t,SV_UDS_I(0)) && |

| NULL != T_STORAGE_R_NV(t,SV_UDSI_G(0))) |

| { |

| begin_c_loop(f,t) |

| { |

| /* this is for post processing purpuses */ |

| F_UDMI(f,t,0) = - C_UDSI_G(F_C0(f,t),t->t0,0)[0]; |

| F_UDMI(f,t,1) = - C_UDSI_G(F_C0(f,t),t->t0,0)[1]; |

| F_UDMI(f,t,2) = - C_UDSI_G(F_C0(f,t),t->t0,0)[2]; |

| DEFINE_DPM_BODY_FORCE(particle_body_force, p, i) |

| { |

| #if !RP_HOST |

| cell_t c = RP_CELL(&(p->cCell)); |

| Thread *t = RP_THREAD(&(p->cCell)); |

| if ( i==0) |

| { |

| bforce=q0*exp(-0.0097*P_TIME(p))*C_UDMI(c,t,0); /* q*Ex */ |

| } |

| else if (i==1) |

| { |

| bforce = q0*exp(-0.0097*P_TIME(p))*C_UDMI(c,t,1);/* q*Ey */ |

| } |

| else |

| { |

| bforce = q0*exp(-0.0097*P_TIME(p))*C_UDMI(c,t,2);/* q*Ez */ |

| } |

| /* an acceleration should be returned m/s2 or q*E is [C/kg]*[V/m] this is [N]/[Kg] */ |

| #endif |

| } |

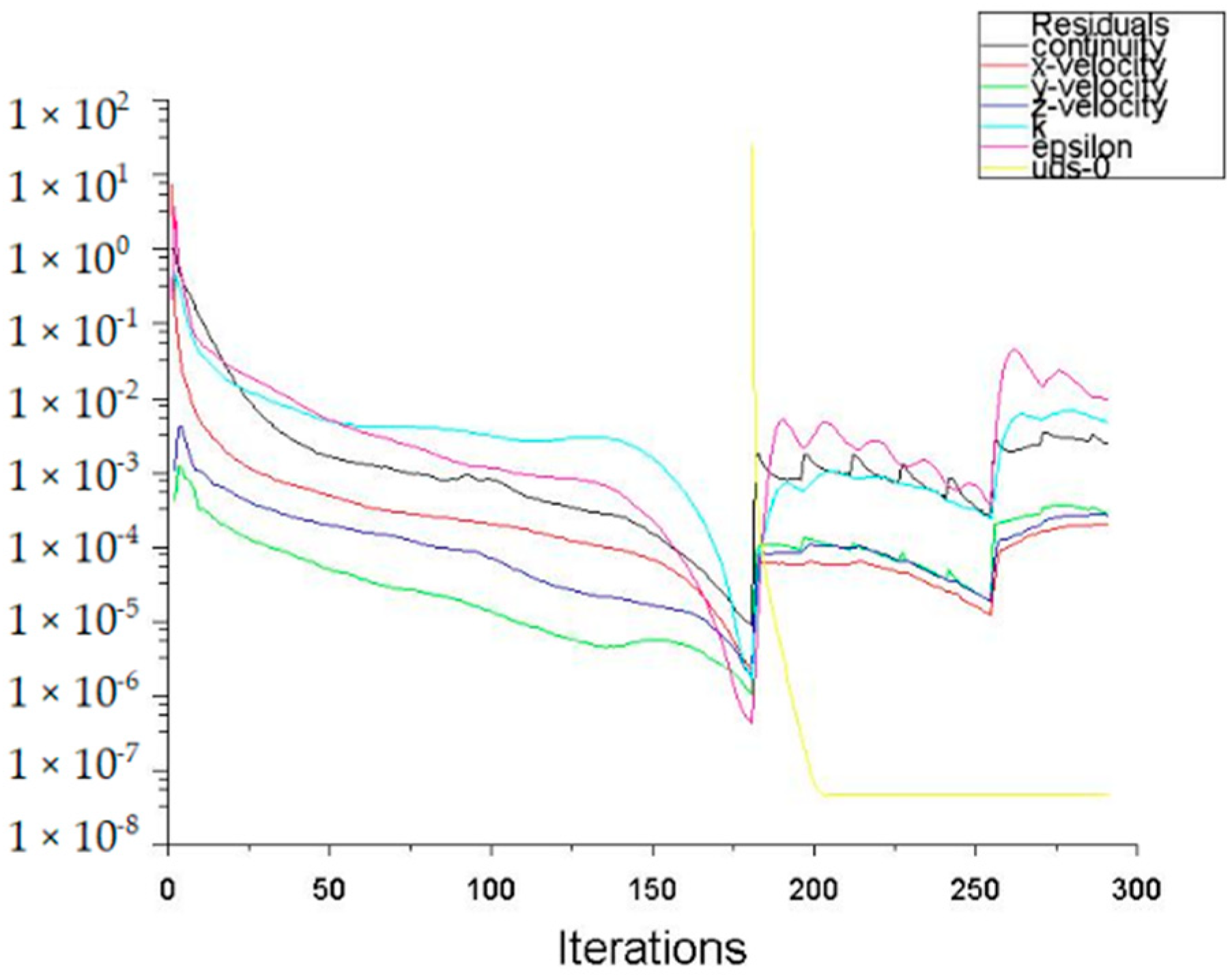

2.2.4. Simulation Model Verification

2.2.5. Experiment Design

3. Results and Discussion

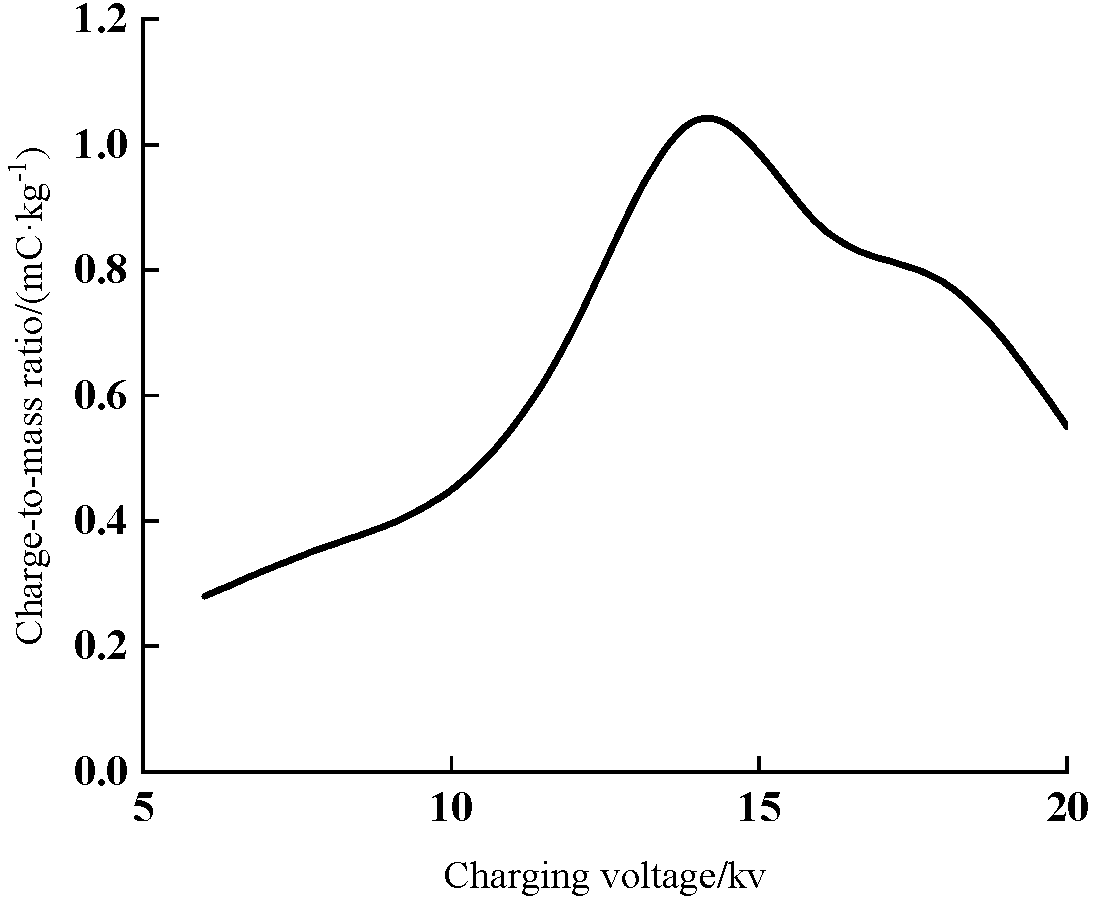

3.1. Charge-Mass Ratio of Electrostatic Droplets Analysis

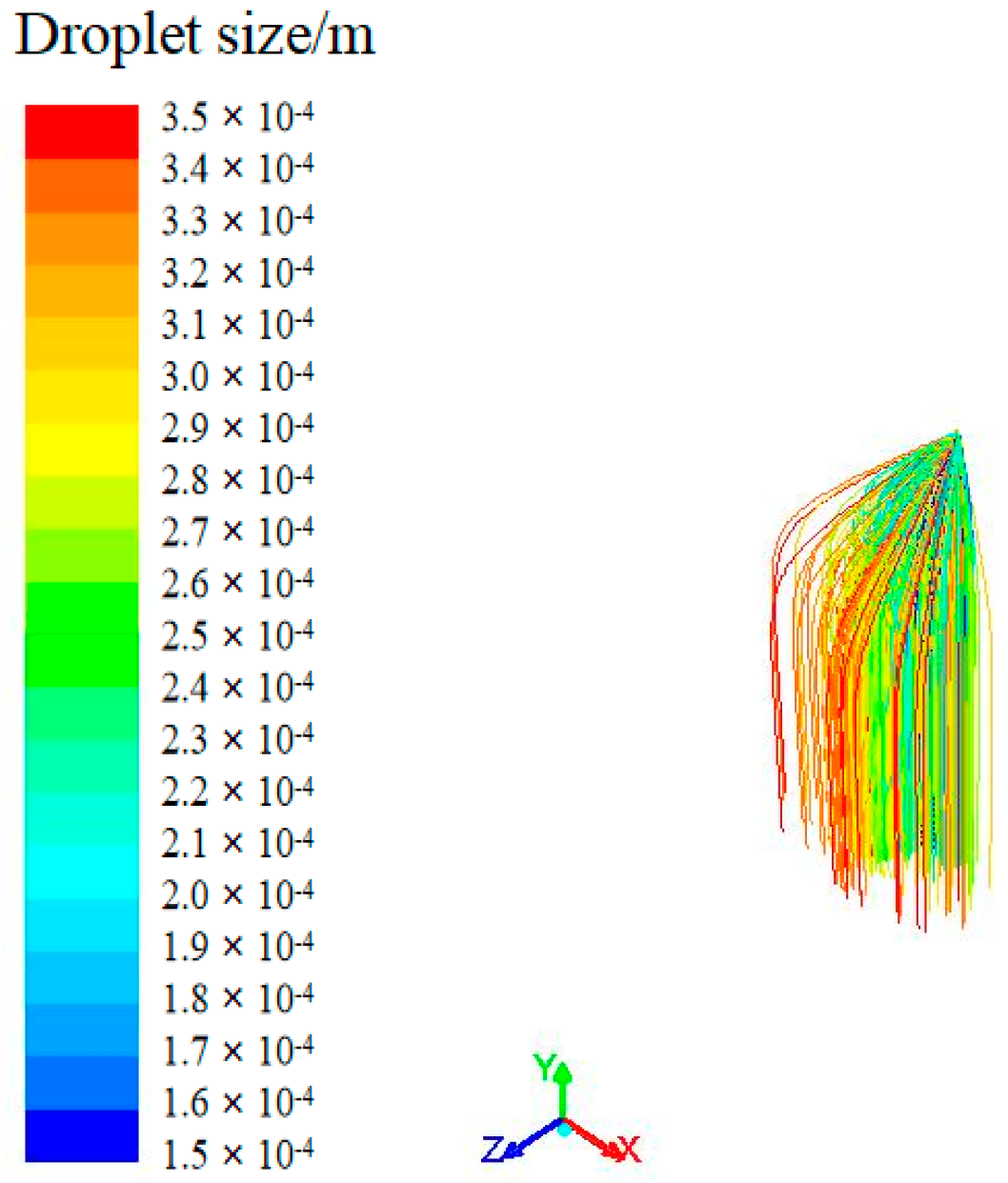

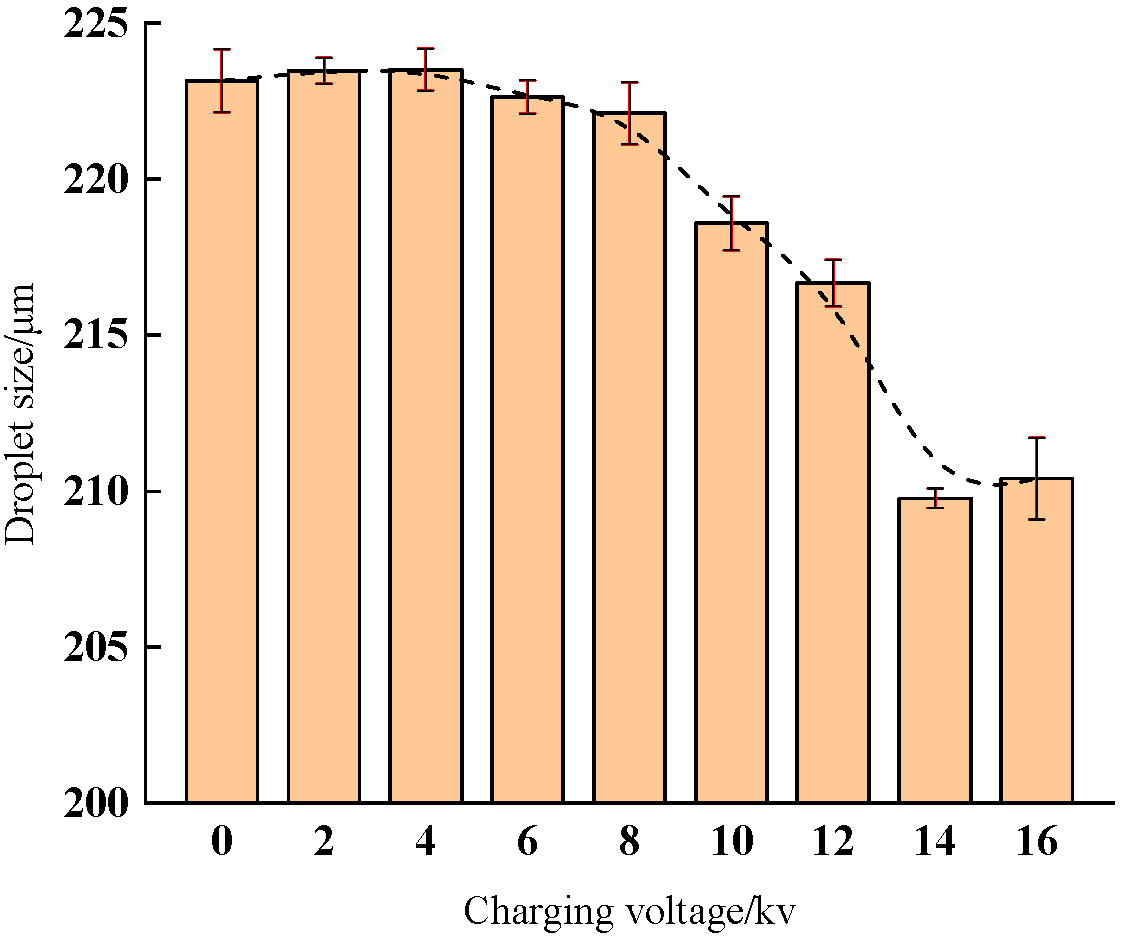

3.2. Particle Size of Electrostatic Droplets Analysis

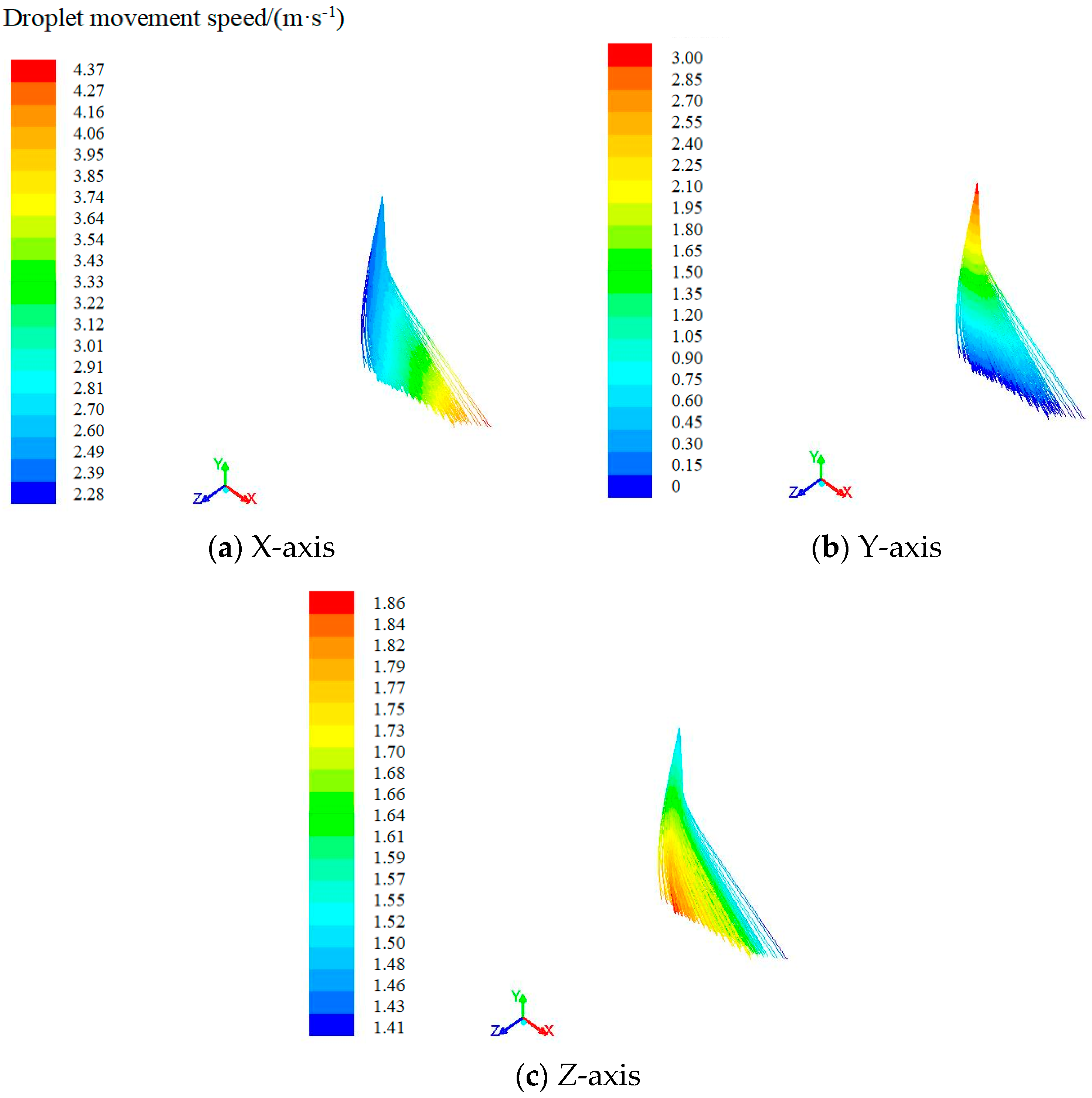

3.3. Numerical Simulation Analysis

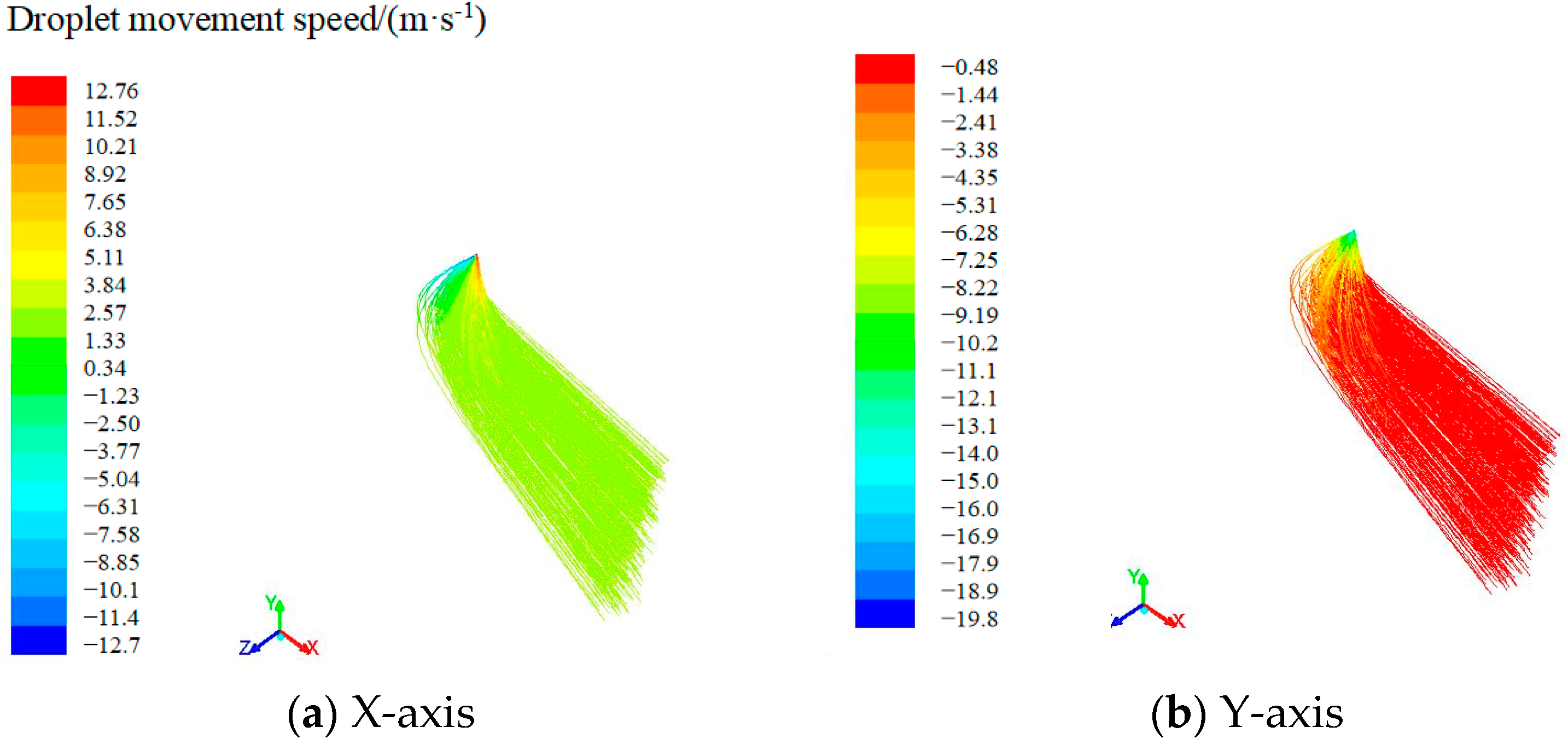

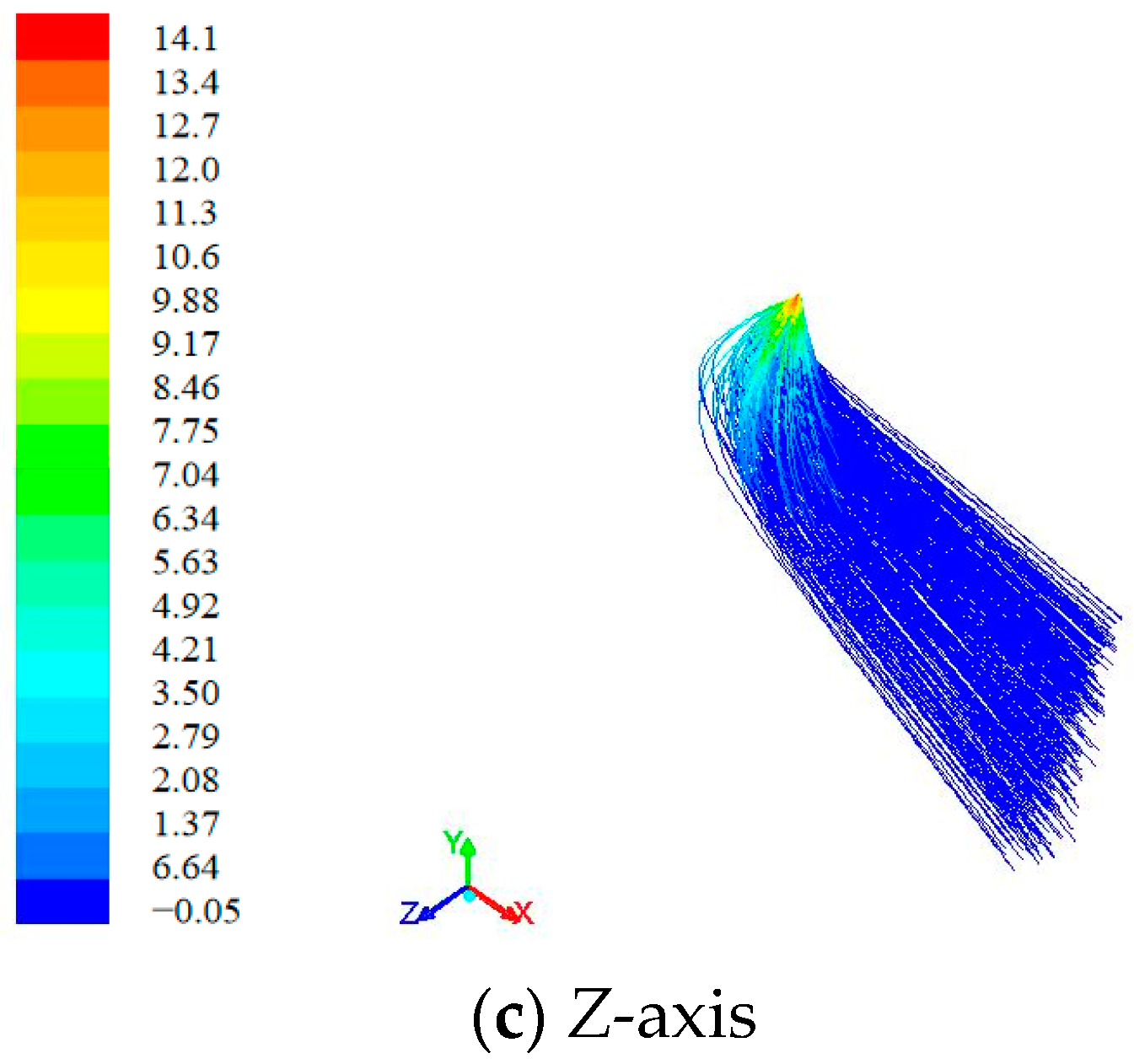

3.3.1. Droplets Movement Trajectory at Different Spray Heights

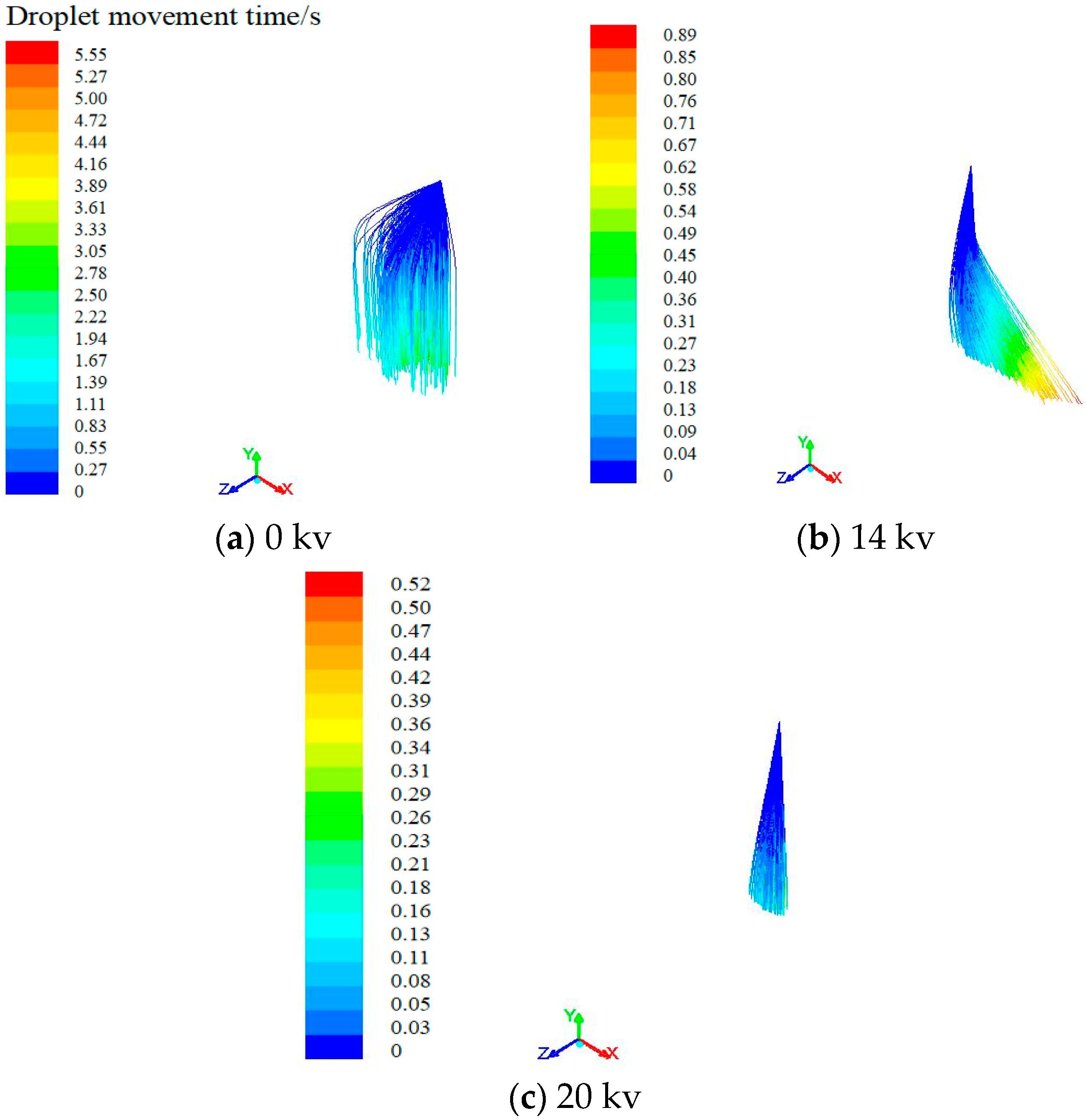

3.3.2. Droplets Movement Trajectory at Different Charging Voltages

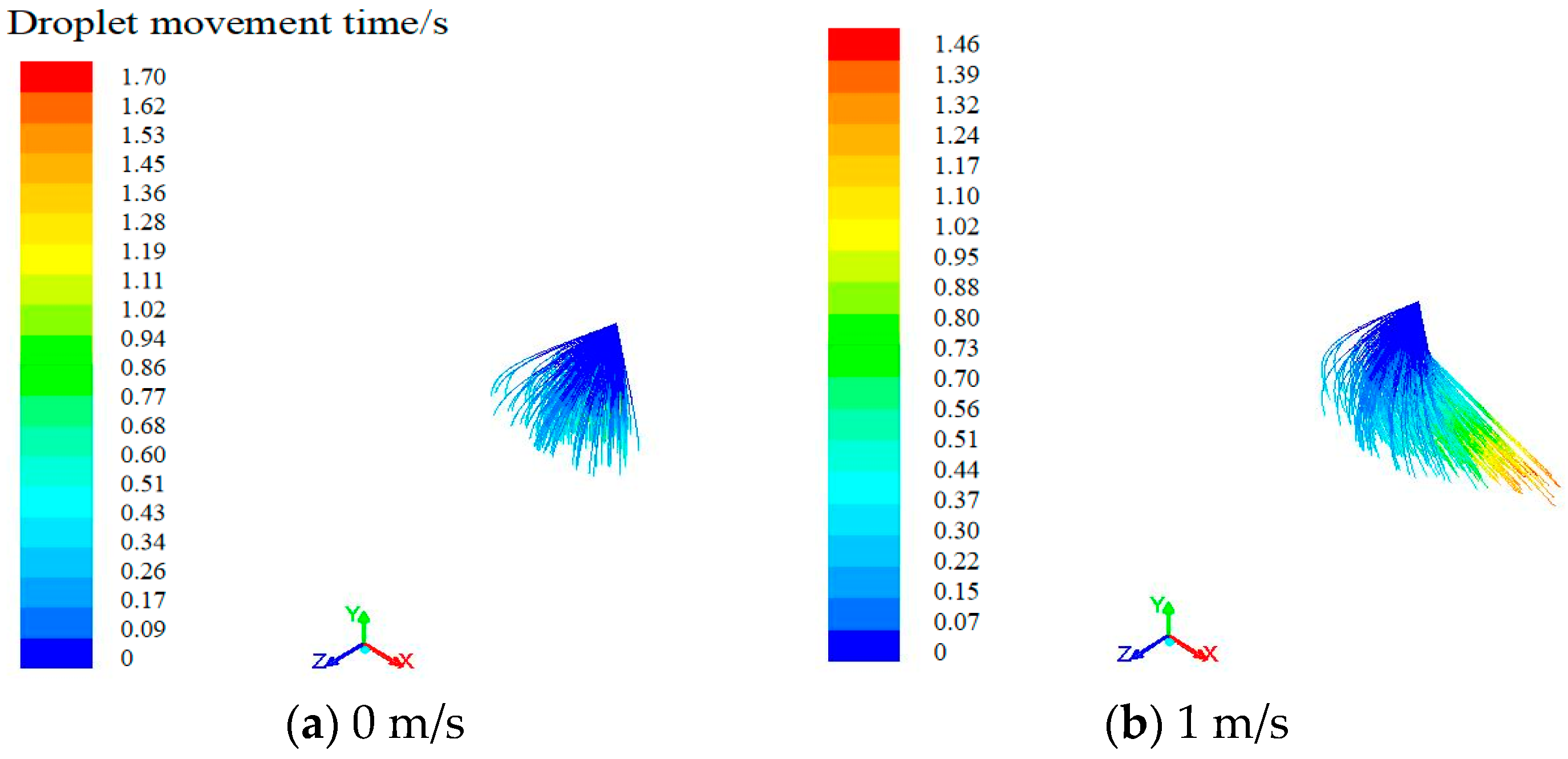

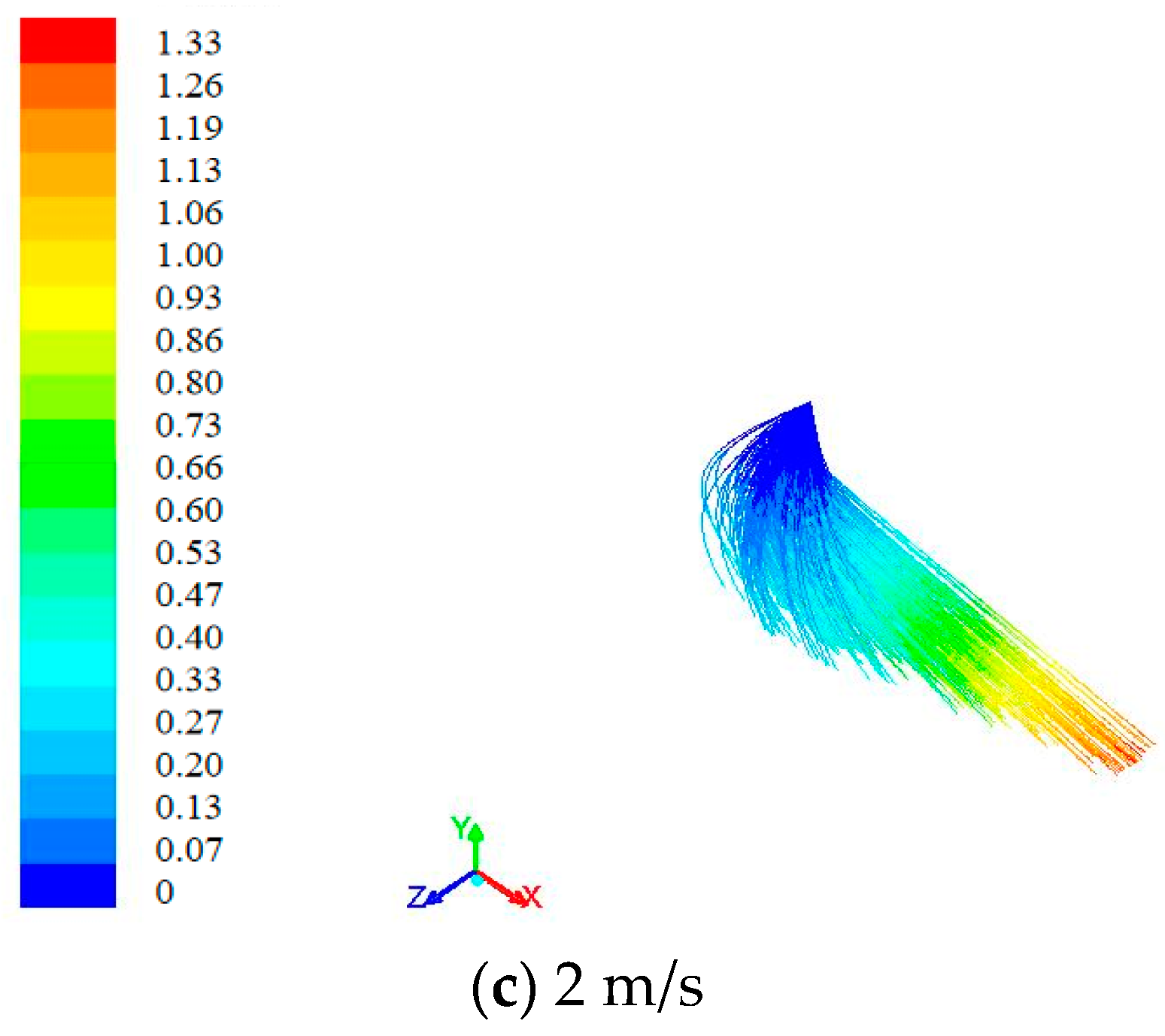

3.3.3. Droplets Movement Trajectory at Different Lateral Winds

3.3.4. Motion Characteristics of Charged Droplet Comparative Analysis

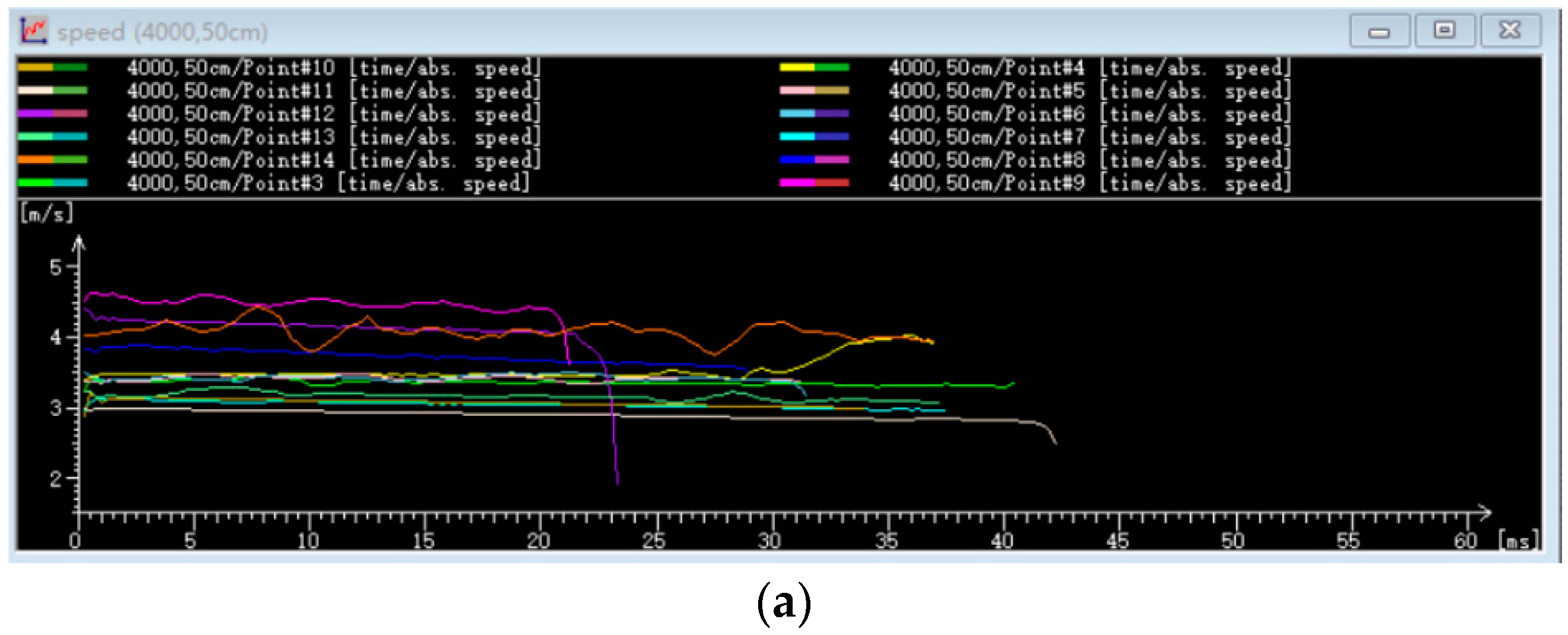

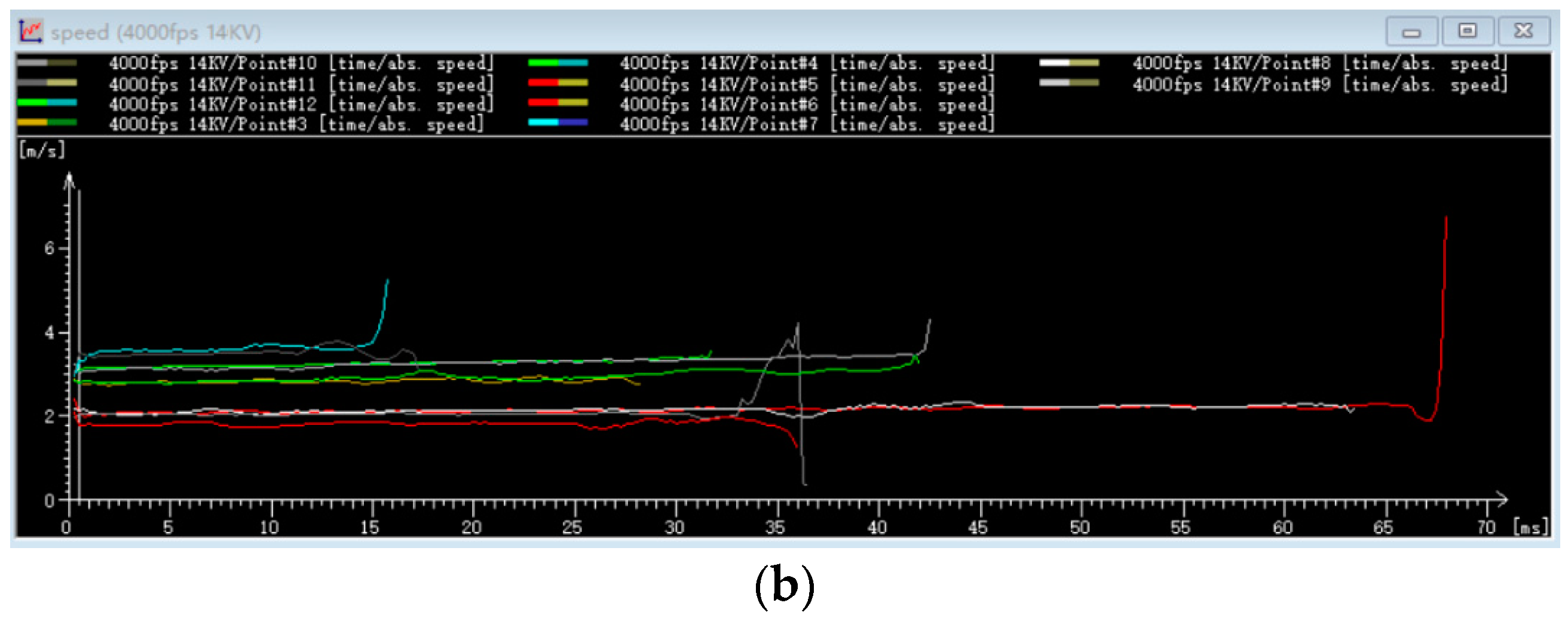

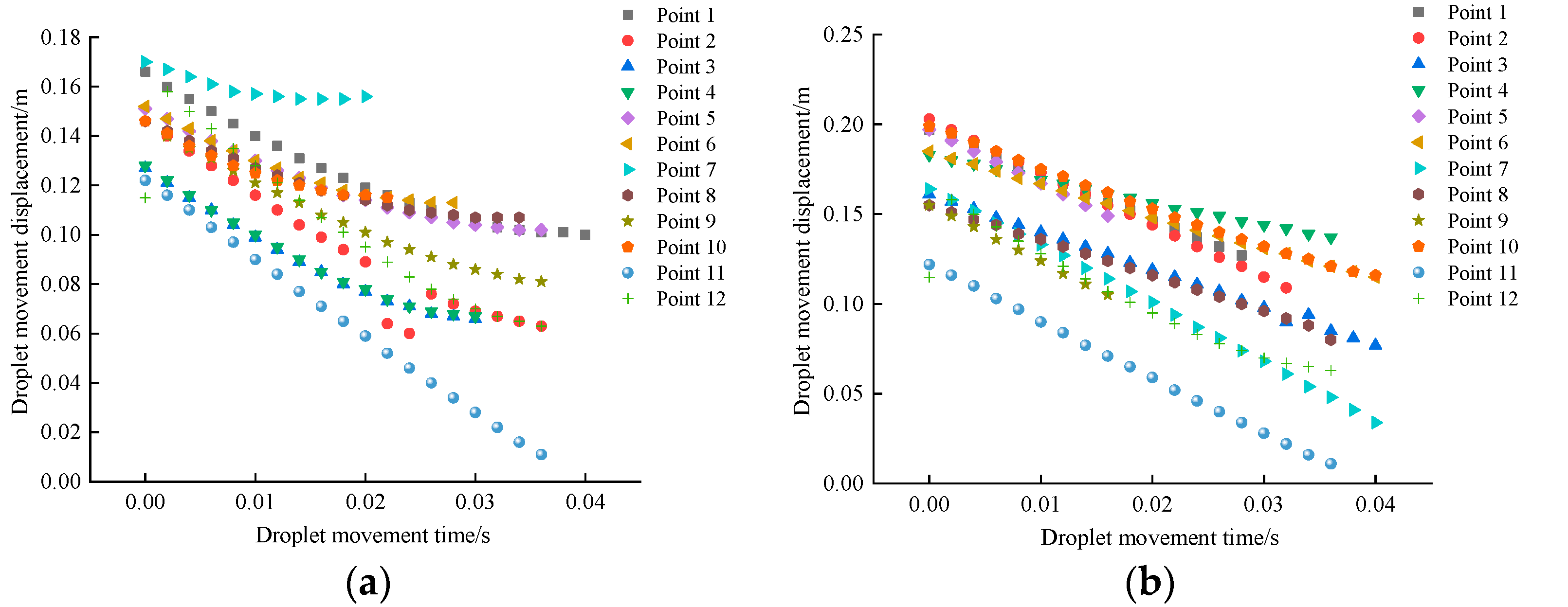

3.4. Droplet Motion Characteristics by High-Speed Camera Technology Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, X.; Song, L.; Cui, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, M. Decoupling on influence of air droplets stress and canopy porosity change on deposition performance in air-assisted spray. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2021, 52, 117–126, 137. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Y.; Chen, S. Current status and trends of plant protection UAV and its spraying technology in China. Int. J. Precis. Agric. Aviat. 2018, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Chen, S.; Fritz, B.K. Current status and future trends of precision agricultural aviation technologies. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2017, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Lan, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Liang, D. Current status and future trends of agricultural aerial spraying technology in China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2014, 45, 53–59. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Y.; Chen, S.; Deng, J.; Zhou, Z.; Ouyang, F. Development situation and problem analysis of plant protection unmanned aerial vehicle in China. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2019, 10, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.; Latheef, M. Aerial electrostatic spray deposition and canopy penetraion in cotton. J. Electrost. 2017, 90, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Latheef, M.; López, J. Electrostatically charged aerial application improved spinosad deposition on early season cotton. J. Electrost. 2019, 97, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Praveen, B.; Sahoo, H.; Patel, B.; Kumar, A.; Singh, M. An advance air-induced air-assisted electrostatic nozzle with enhanced performance. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 135, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, J.; Barizon, R.; Ferracini, V. Spray drift and caterpilar and stink bug control from aerial applications with electrostatic charge and atomizer on soybean crop. Eng. Agric. 2017, 37, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, L.; Xue, X. Research progress and application status of electrostatic pesticide spray technology. Trans. CSAE 2018, 34, 1–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Zhou, H. Design and experiment of an aerial electrostatic spraying system for unmanned agricultural aircraft systems. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2020, 36, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, S.; Roten, R. A review of the effects of droplet size and flow rate on the chargeability of spray droplets in electrostatic agricultural sprays. Trans. ASABE 2018, 61, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Lan, Y.; Shen, W. Development of a charge transfer space loop to improve adsorption performance in aerial electrostatic spray. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2020, 13, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, Y.; Jin, L.; Jia, Z. Design and experiment on electrostatic spraying system for unmanned aerial vehicle. Trans. CSAE 2015, 31, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Assuno, H.; Cunha, J.; Silva, S. Spray deposition on maize using an electrostatic sprayer. Eng. Agrícola 2020, 40, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hou, Y.; Liu, X. Wind tunnel experimental study on droplet drift reduction by a conical electrostatic nozzle for pesticide spraying. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2017, 10, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Krinke, T.; Deppert, K.; Magnusson, M. Microscopic of the deposition of nanoparticles from the gas phase. J. Aerosol Sci. 2002, 33, 1341–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbert, S.; Colmcross, A. A computer simulation for predicting electrostatic spray coating patterns. Powder Technol. 2005, 151, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastourani, H.; Jahannama, M.; Eslami-Majd, A. A physical insight into electrospray process in cone-jet mode: Role of operating parameters. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2018, 70, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Lan, Y.; Sun, Z.; Chang, C.; Hoffmann, W.C. Develop an unmanned aerial vehicle based automatic aerial spraying system. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 128, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhao, S.; Li, Q.; Zhang, W. Numerical Simulation on Air-Liquid Transient Flow and Regression Model on Air-Liquid Ratio of Air Induction Nozzle. Agronomy 2023, 13, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, W.; Wen, J. Numerical simulation on gas-liquid phase flow of large-scale plant protection unmanned aerial vehicle spraying. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2017, 48, 62–69. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mark, N.; Malay, M.; Robert, C. Predicting particle trajectories on an electrodynamic screen-theory and experiment. J. Electrost. 2013, 71, 185–188. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, T. Experimental study on size and velocity of charged droplets. Procedia Eng. 2015, 126, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwek, J.; Heng, D.; Lee, S. High speed imaging with electrostatic charge monitoring to track powder deagglomeration upon impact. J. Aerosol Sci. 2013, 65, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frej, D.; Jaśkiewicz, M. Comparison of Volunteers’ Head Displacement with Computer Simulation—Crash Test with Low Speed of 20 km/h. Sensors 2022, 22, 9720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Liang, H.; Yang, Y. Molecular dynamics study of electric field acting on water surface potential. Chem. J. 2019, 77, 1045–1053. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Main Parameter | Norms and Numerical Value |

|---|---|

| Accuracy of image/DPI | 2.7 × 106 |

| Pixel size/μm | 11 |

| Precision of time/μs | 1.5 |

| Maximum dynamic range/dB | 66 |

| Storage memory/GB | 9 |

| Range of color levels/bit | 12 |

| Sensitivity of system/iso | 6400 |

| Serial Number | Diameter/(μm) |

|---|---|

| Point 1 | 132.4 |

| Point 2 | 147.6 |

| Point 3 | 152.3 |

| Point 4 | 143.2 |

| Point 5 | 146.6 |

| Point 6 | 132.1 |

| Point 7 | 153.4 |

| Point 8 | 141.9 |

| Point 9 | 147.3 |

| Point 10 | 145.6 |

| Point 11 | 151.7 |

| Point 12 | 144.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, C.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhao, S.; Li, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, M. Numerical Simulation of the Trajectory of UAVs Electrostatic Droplets Based on VOF-UDF Electro-Hydraulic Coupling and High-Speed Camera Technology. Agronomy 2023, 13, 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13020512

Liu C, Hu J, Li Y, Zhao S, Li Q, Zhang W, Zhao M. Numerical Simulation of the Trajectory of UAVs Electrostatic Droplets Based on VOF-UDF Electro-Hydraulic Coupling and High-Speed Camera Technology. Agronomy. 2023; 13(2):512. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13020512

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Changxi, Jun Hu, Yufei Li, Shengxue Zhao, Qingda Li, Wei Zhang, and Mingming Zhao. 2023. "Numerical Simulation of the Trajectory of UAVs Electrostatic Droplets Based on VOF-UDF Electro-Hydraulic Coupling and High-Speed Camera Technology" Agronomy 13, no. 2: 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13020512

APA StyleLiu, C., Hu, J., Li, Y., Zhao, S., Li, Q., Zhang, W., & Zhao, M. (2023). Numerical Simulation of the Trajectory of UAVs Electrostatic Droplets Based on VOF-UDF Electro-Hydraulic Coupling and High-Speed Camera Technology. Agronomy, 13(2), 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13020512