A Hybrid Ionic Liquid–HPAM Flooding for Enhanced Oil Recovery: An Integrated Experimental and Numerical Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

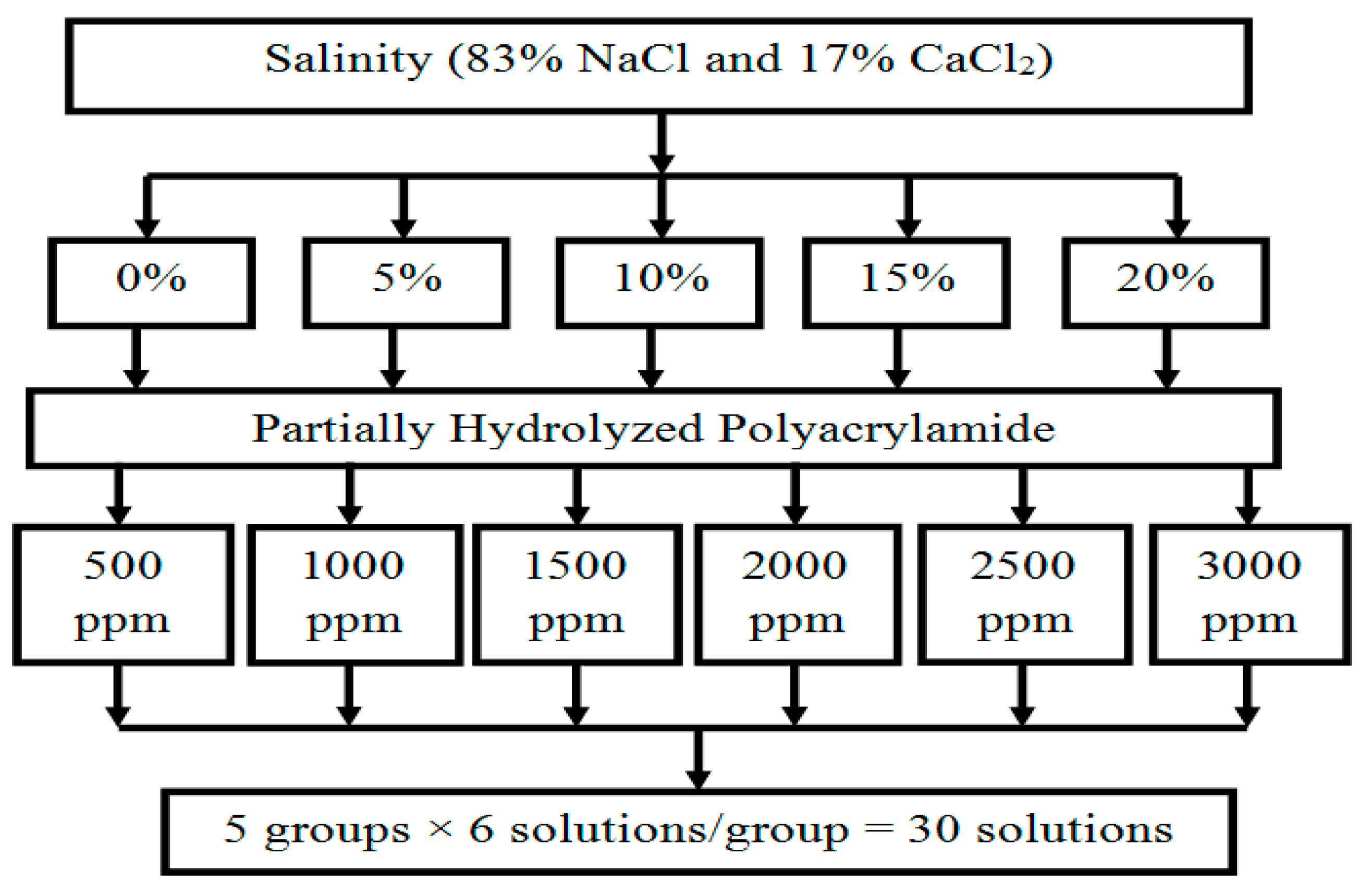

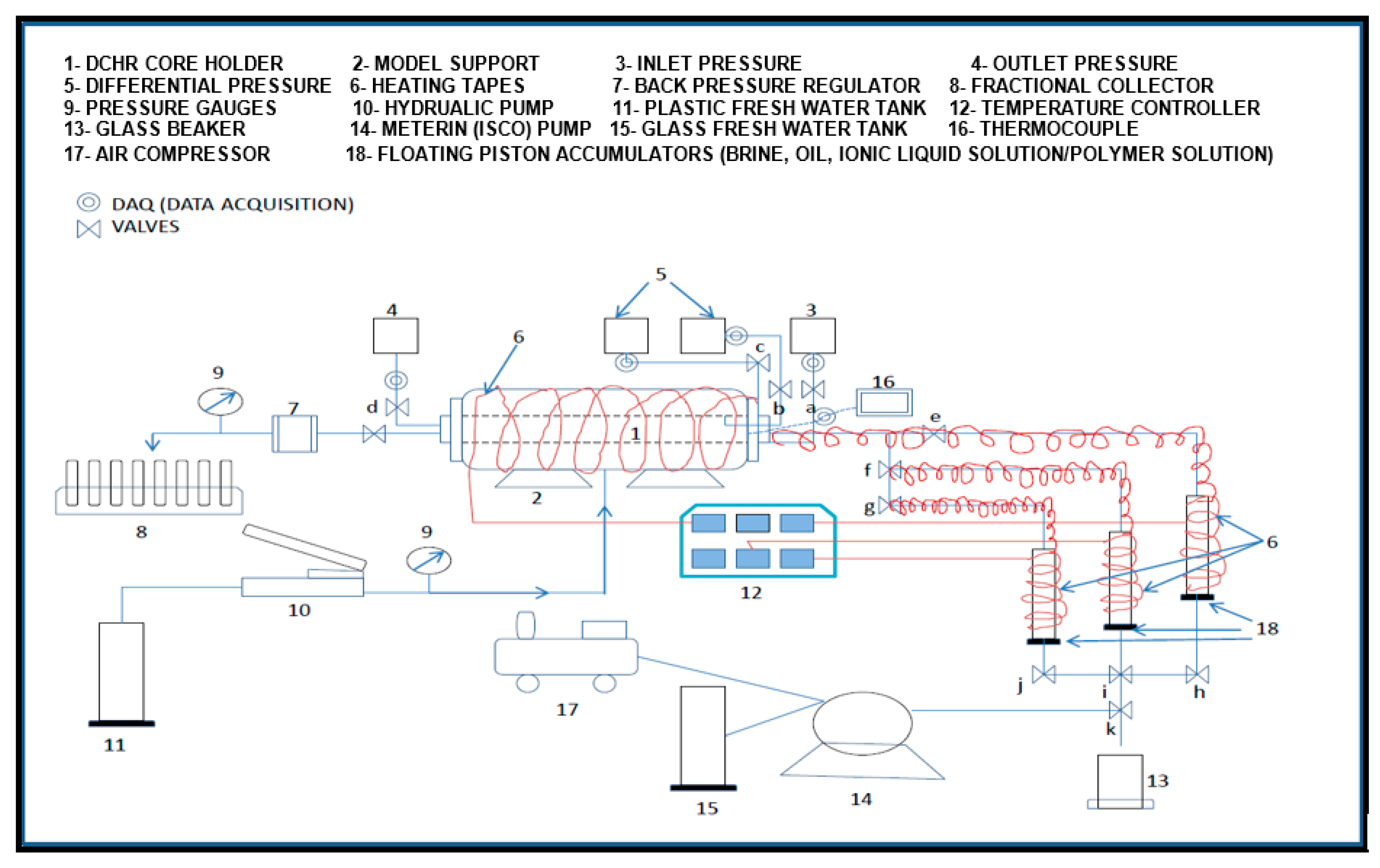

2. Materials and Methods

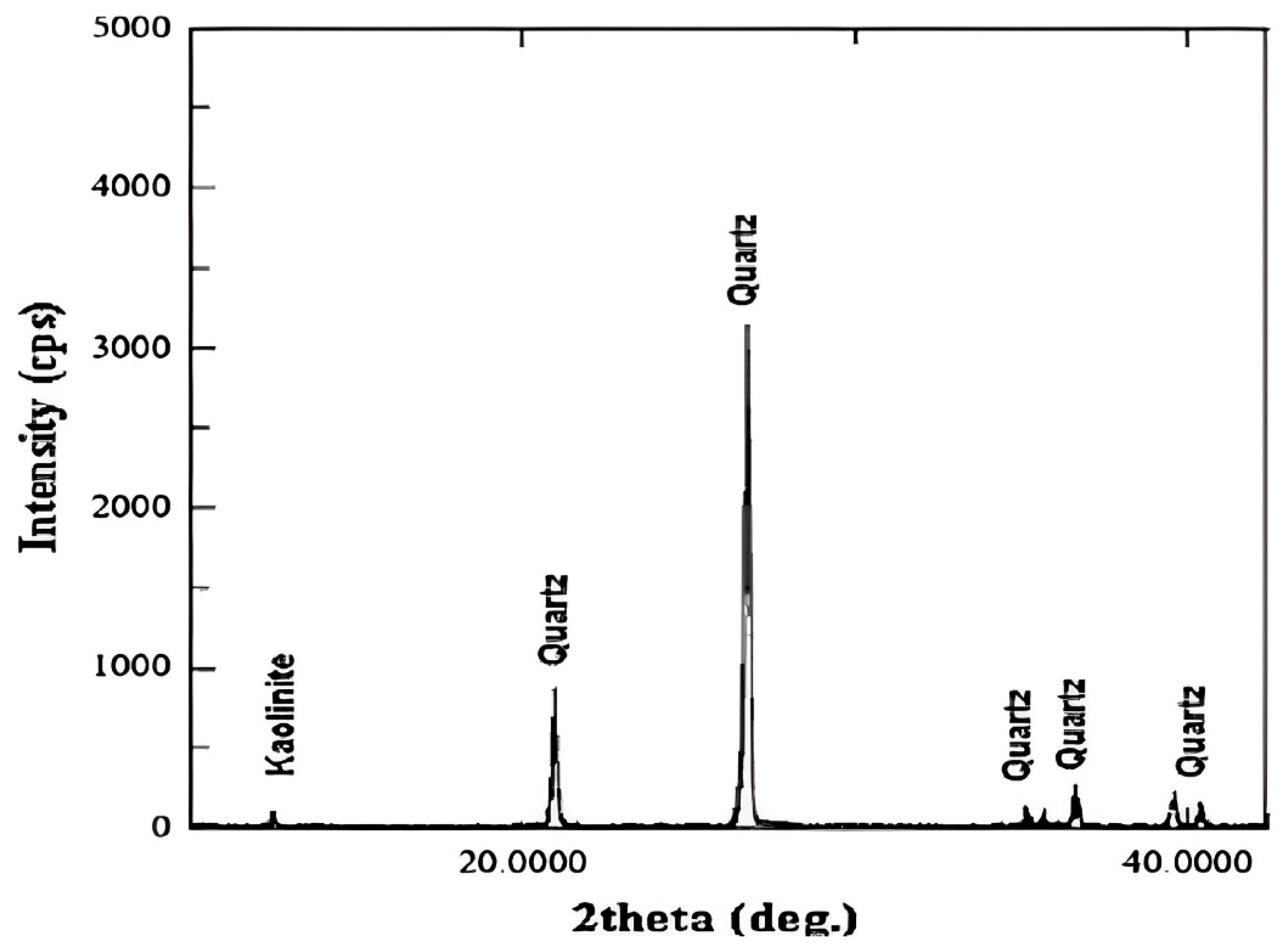

2.1. Materials

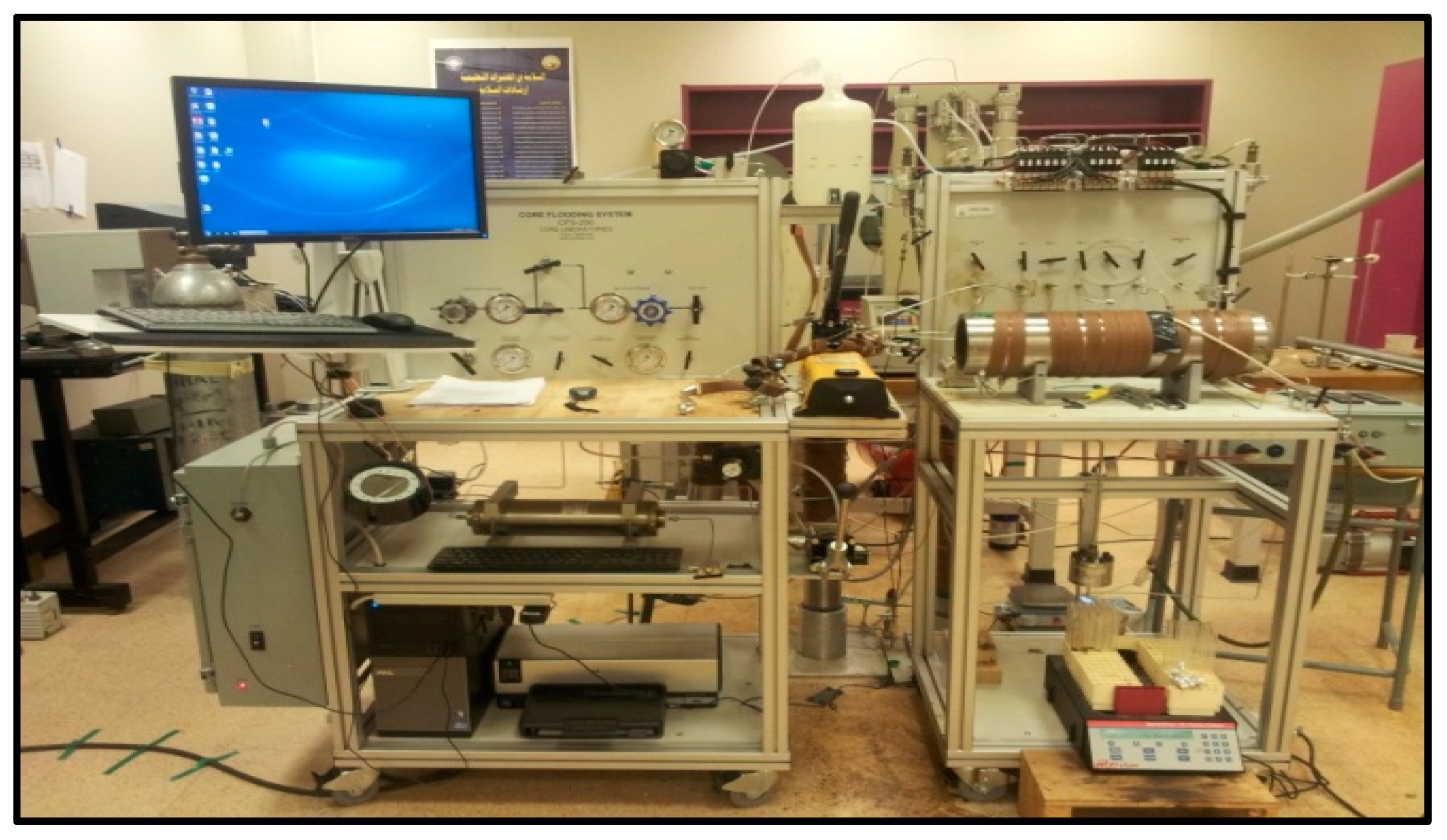

2.2. Experimental Setup and Procedure

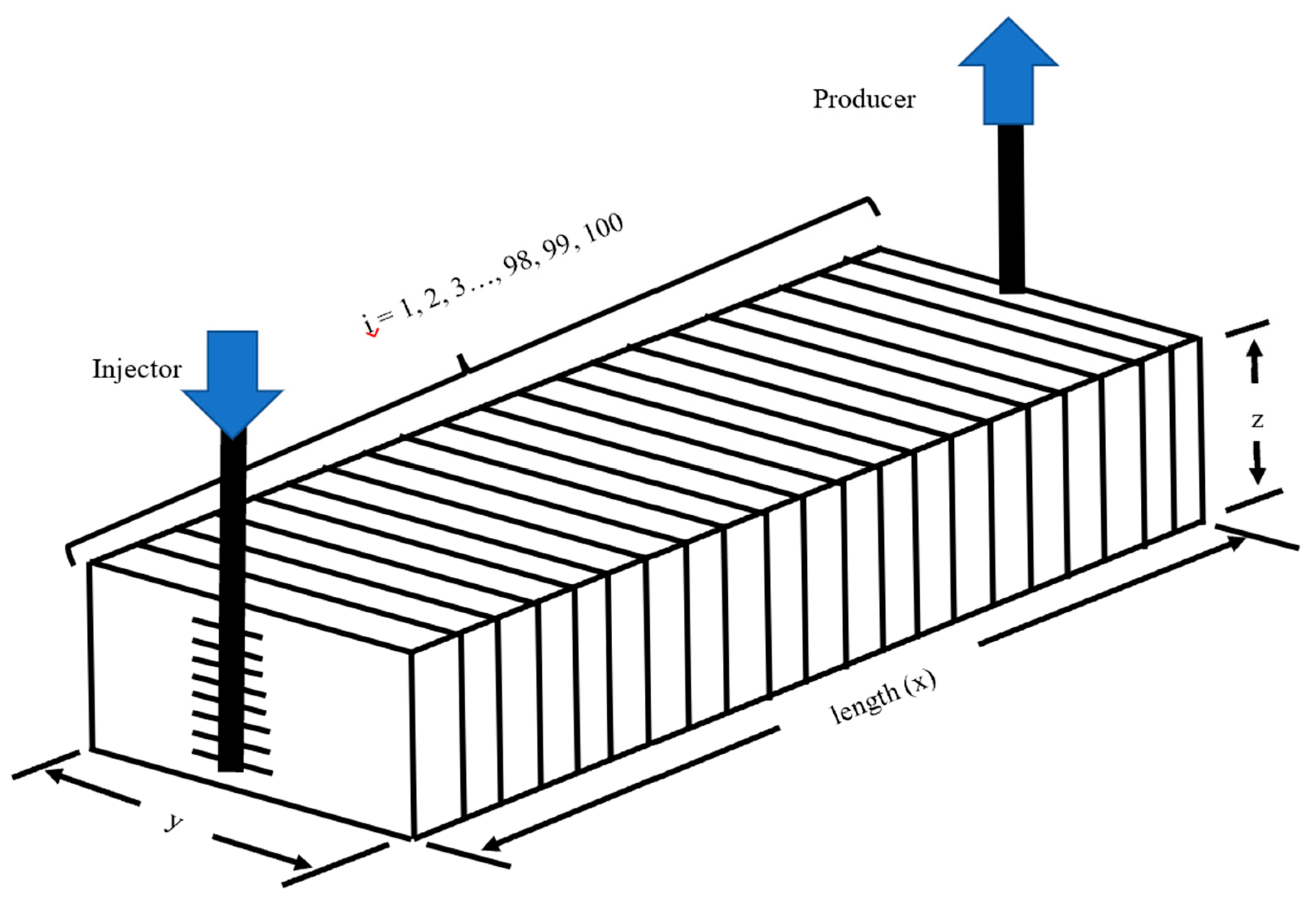

2.3. Numerical Simulation Methodology

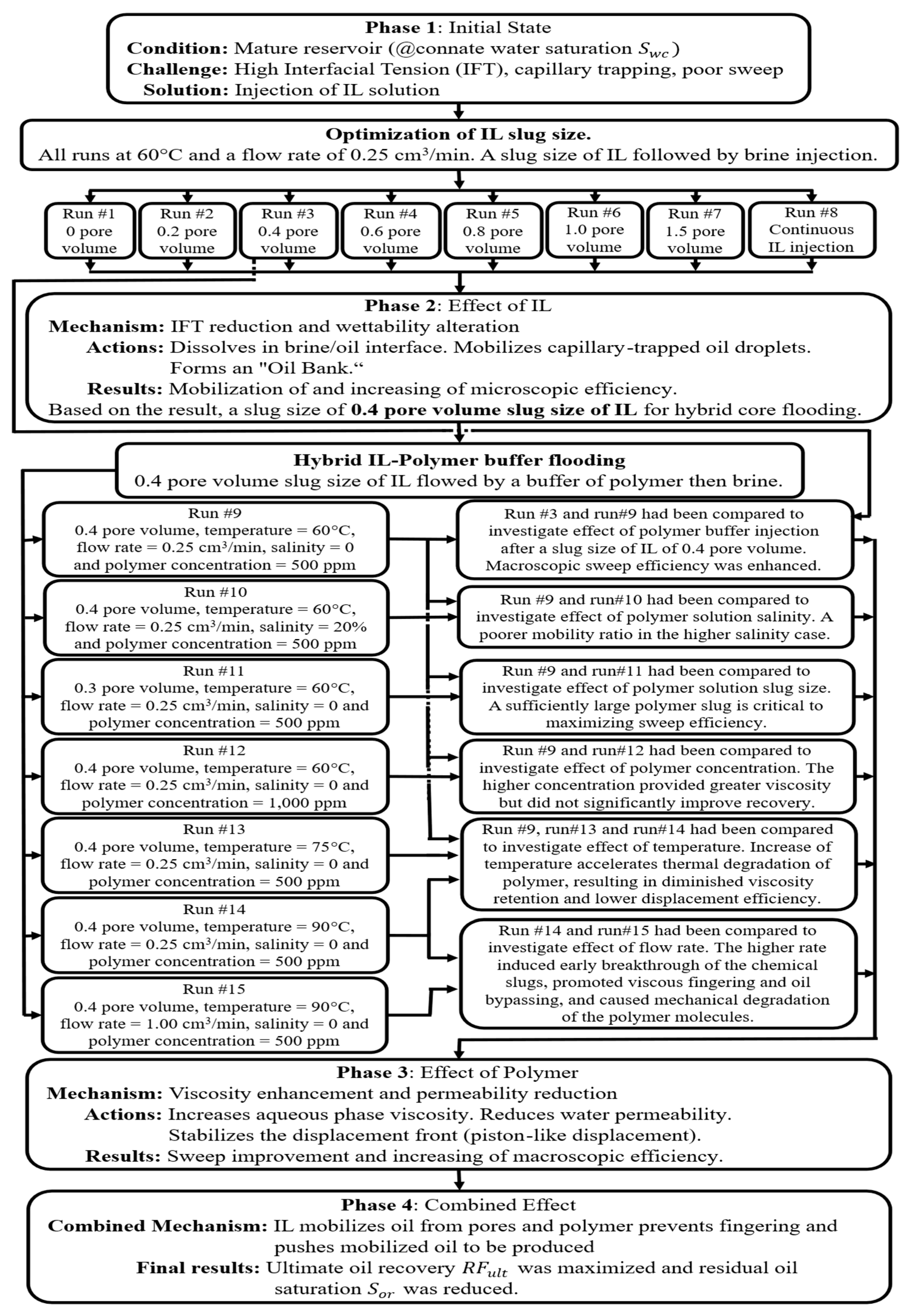

3. Results and Discussion

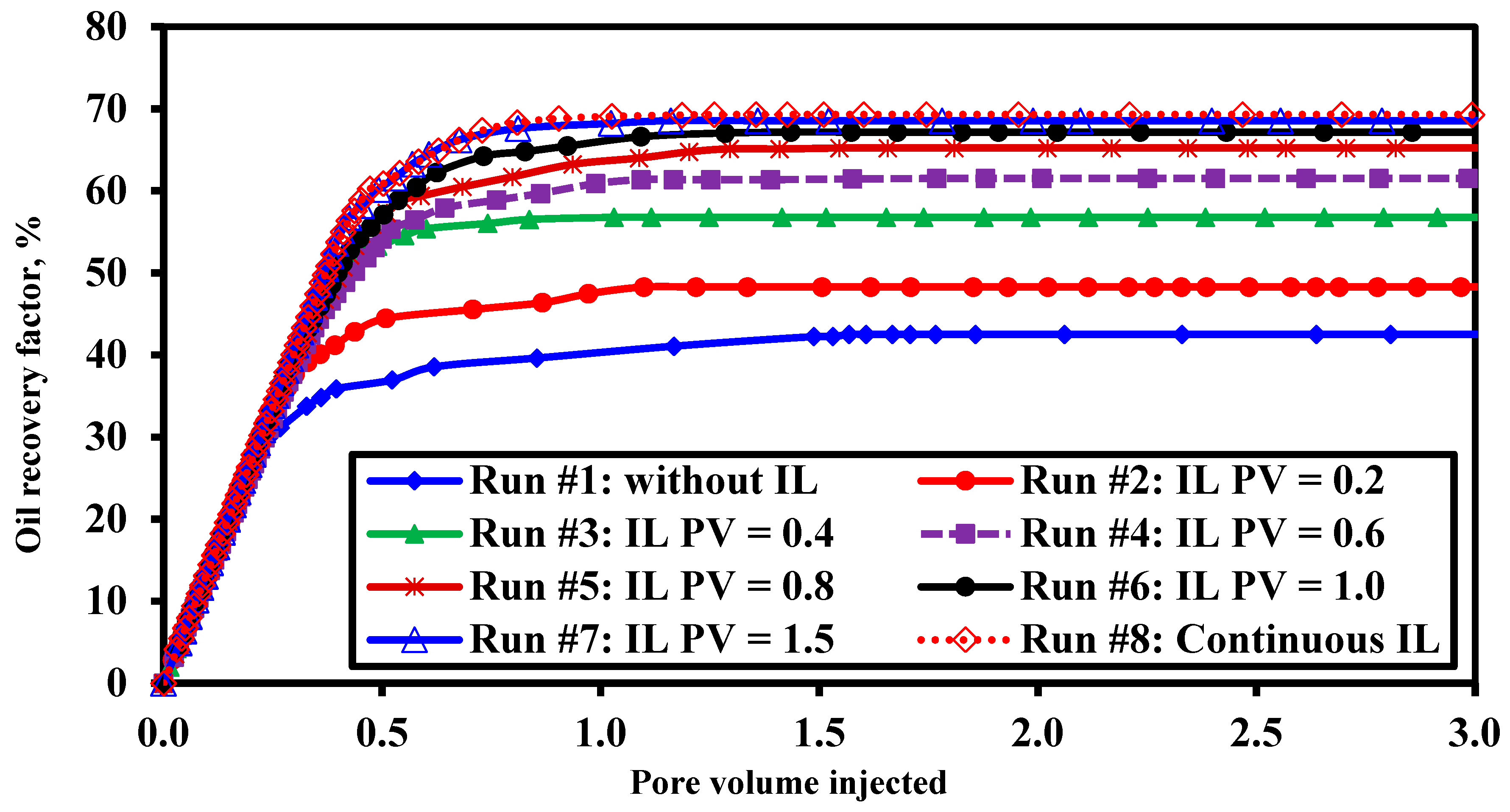

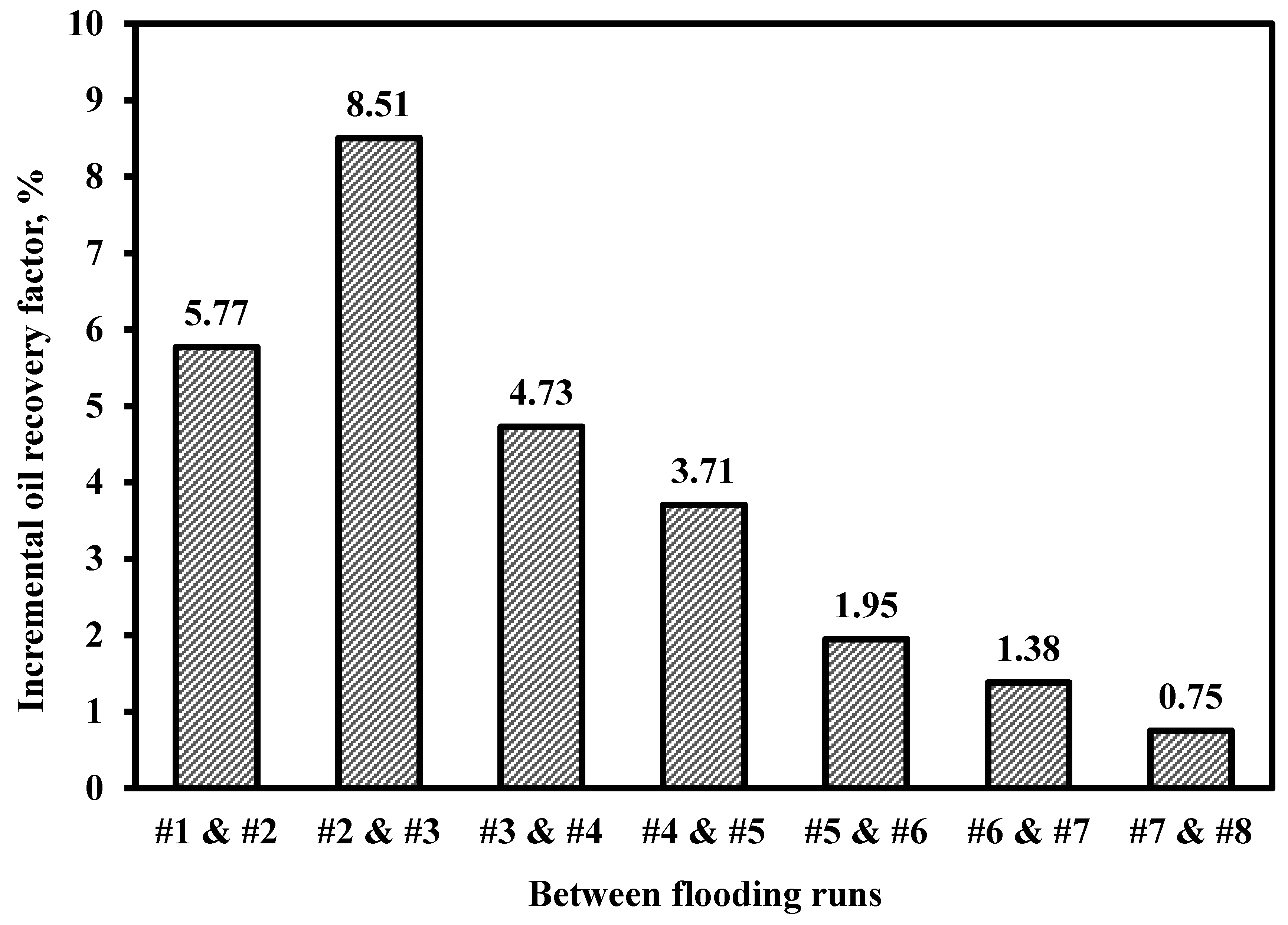

3.1. Optimization of Ionic Liquid Slug Size

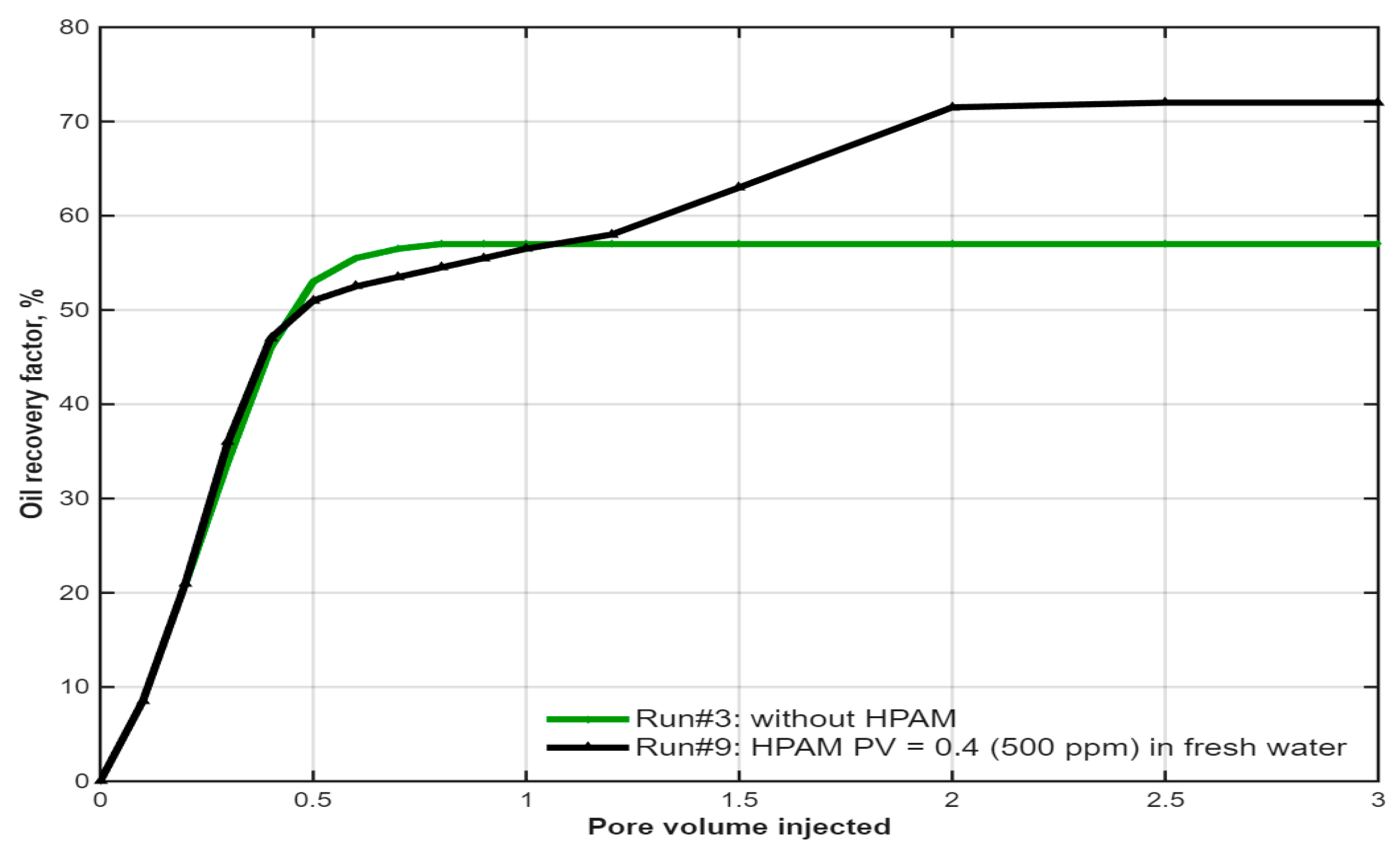

3.2. Synergistic Effect of Polymer Buffer on IL Flooding

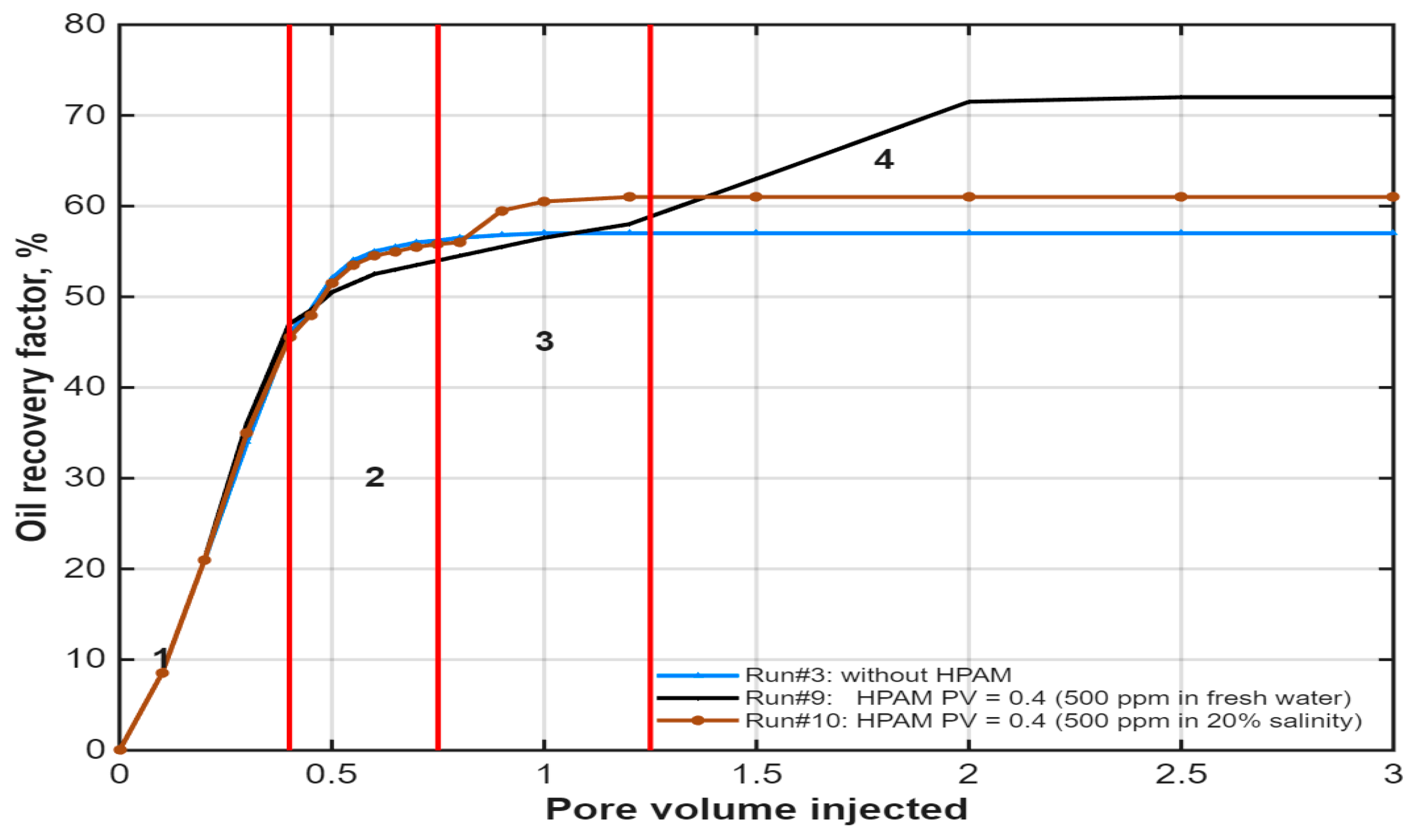

3.3. Effect of Polymer Solution Salinity

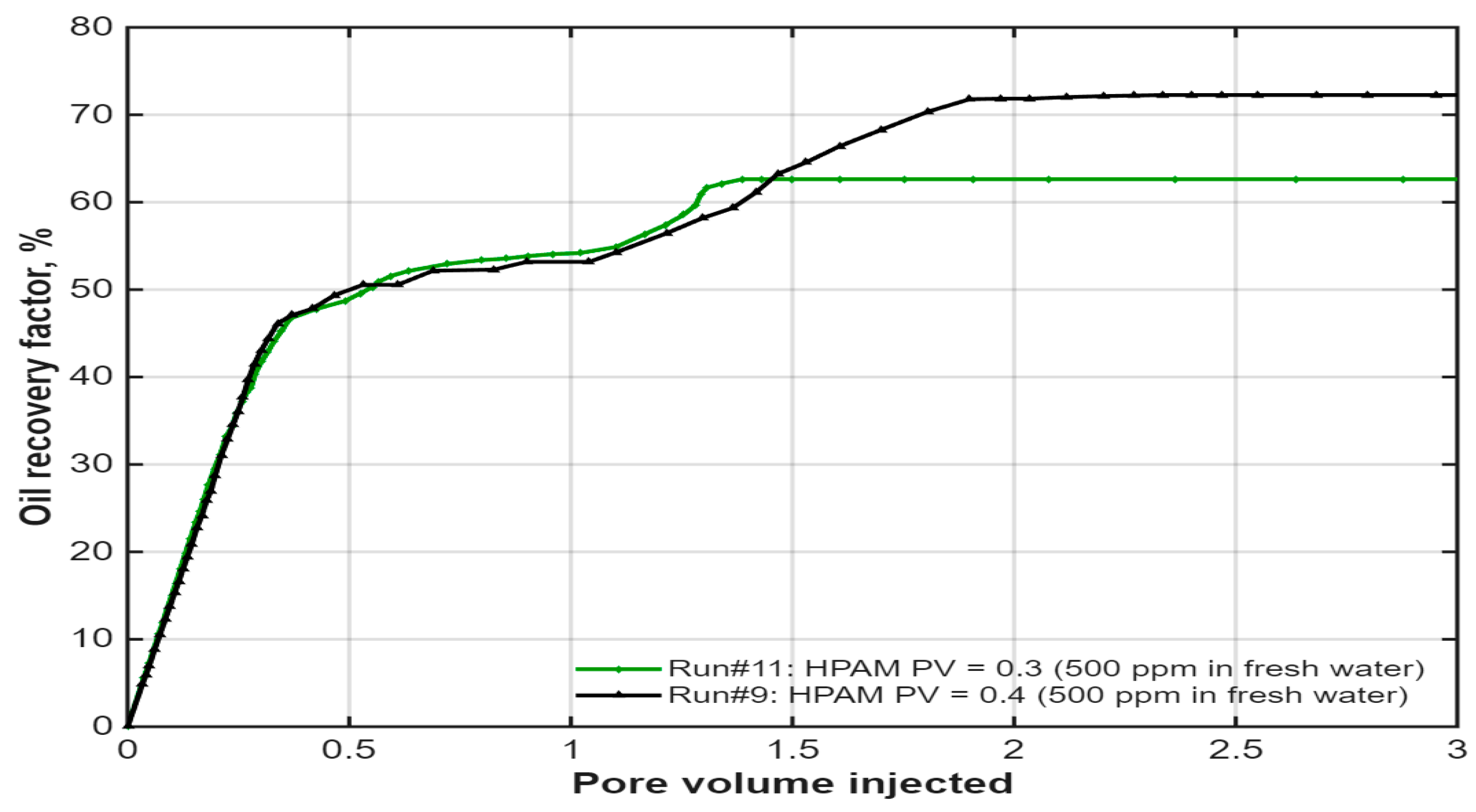

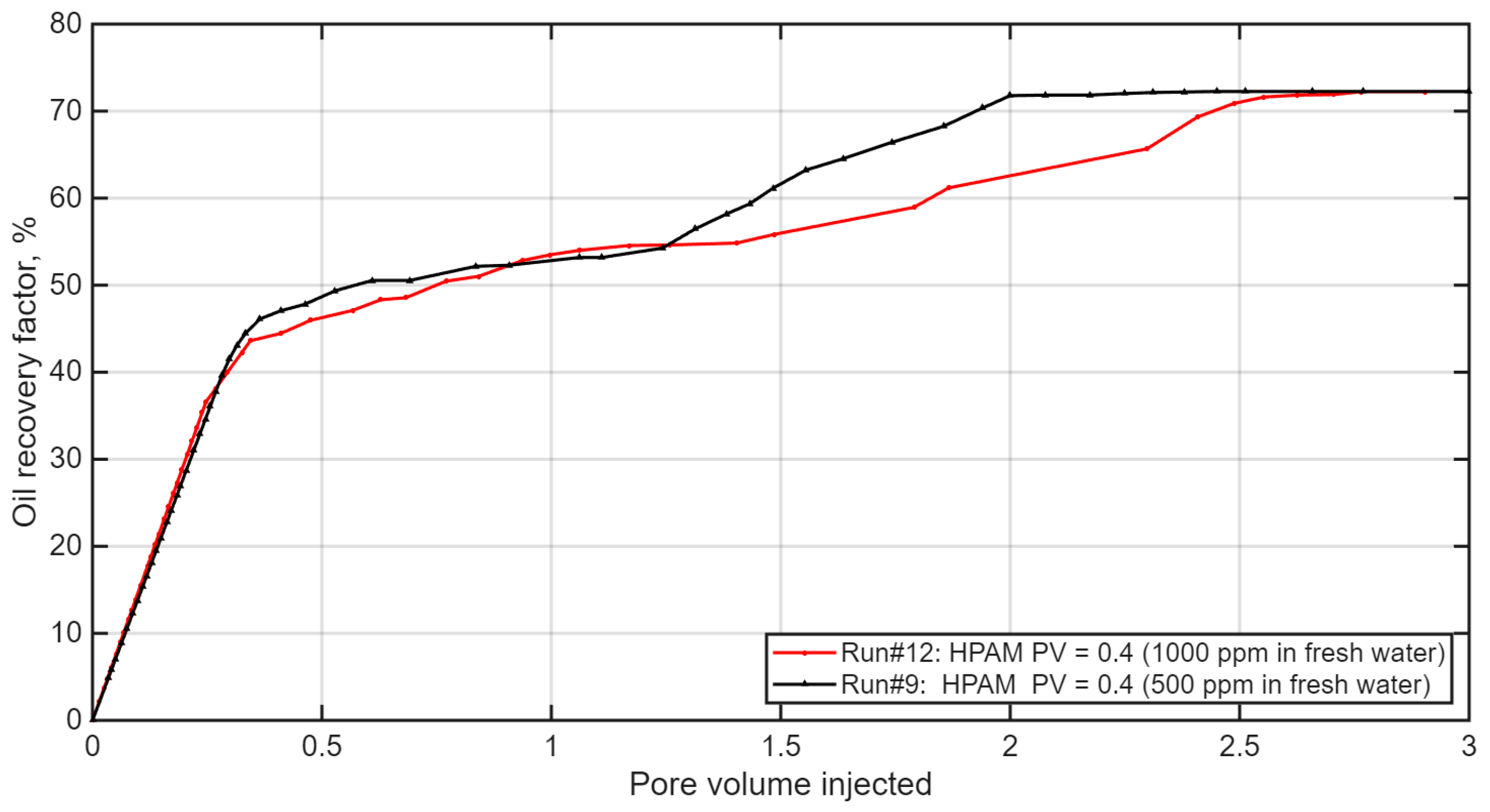

3.4. Effect of Polymer Slug Size and Concentration

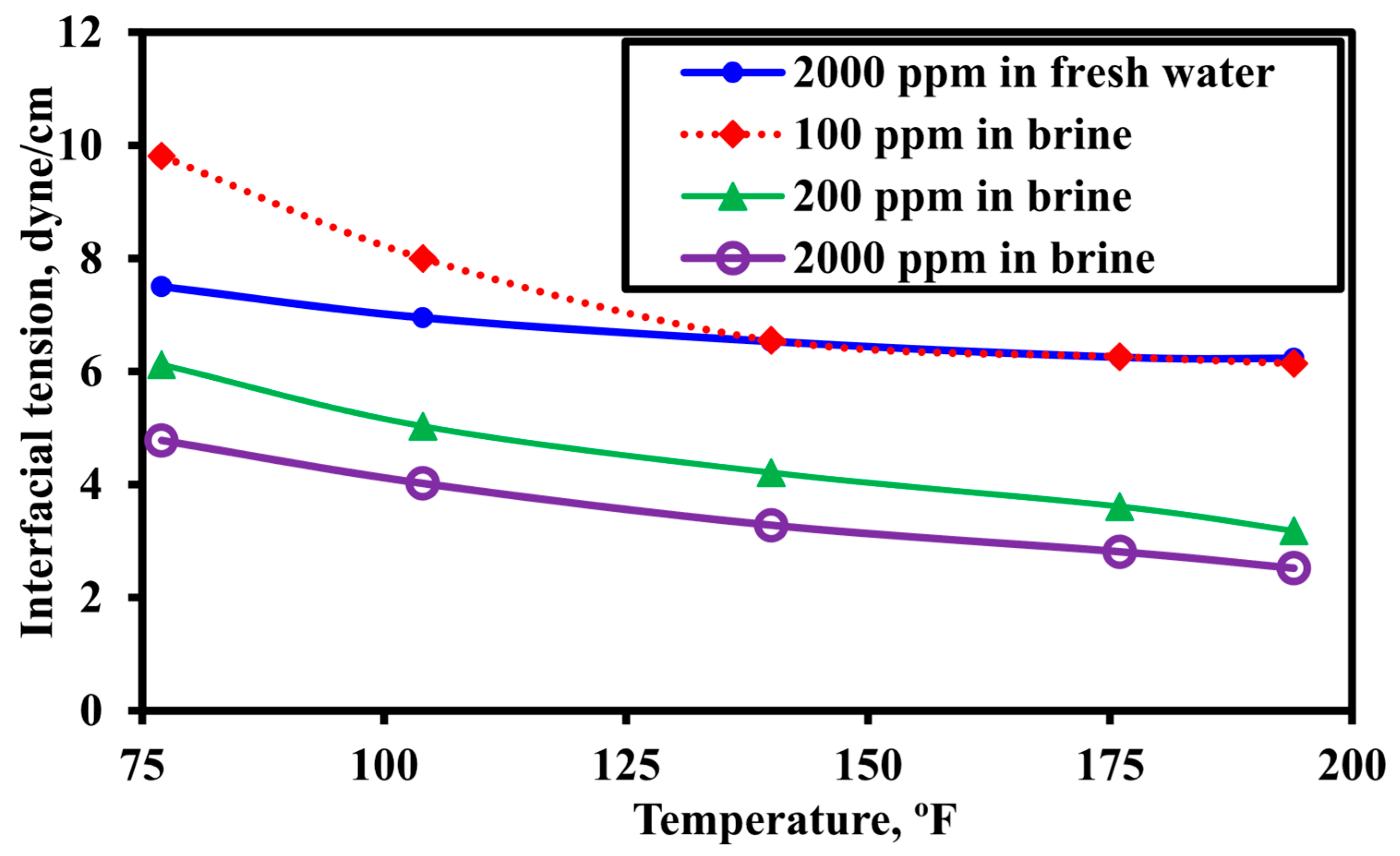

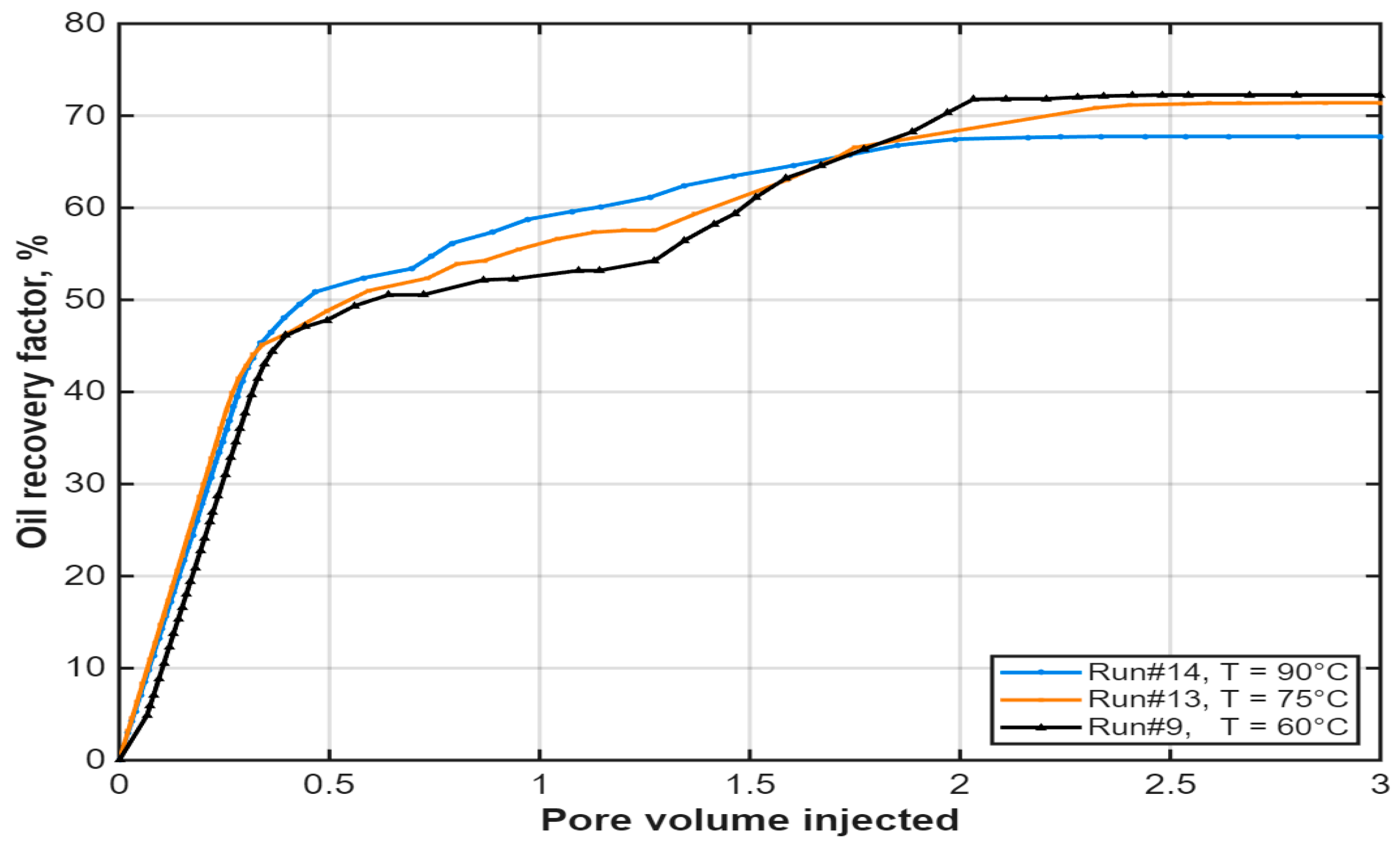

3.5. Effect of Temperature

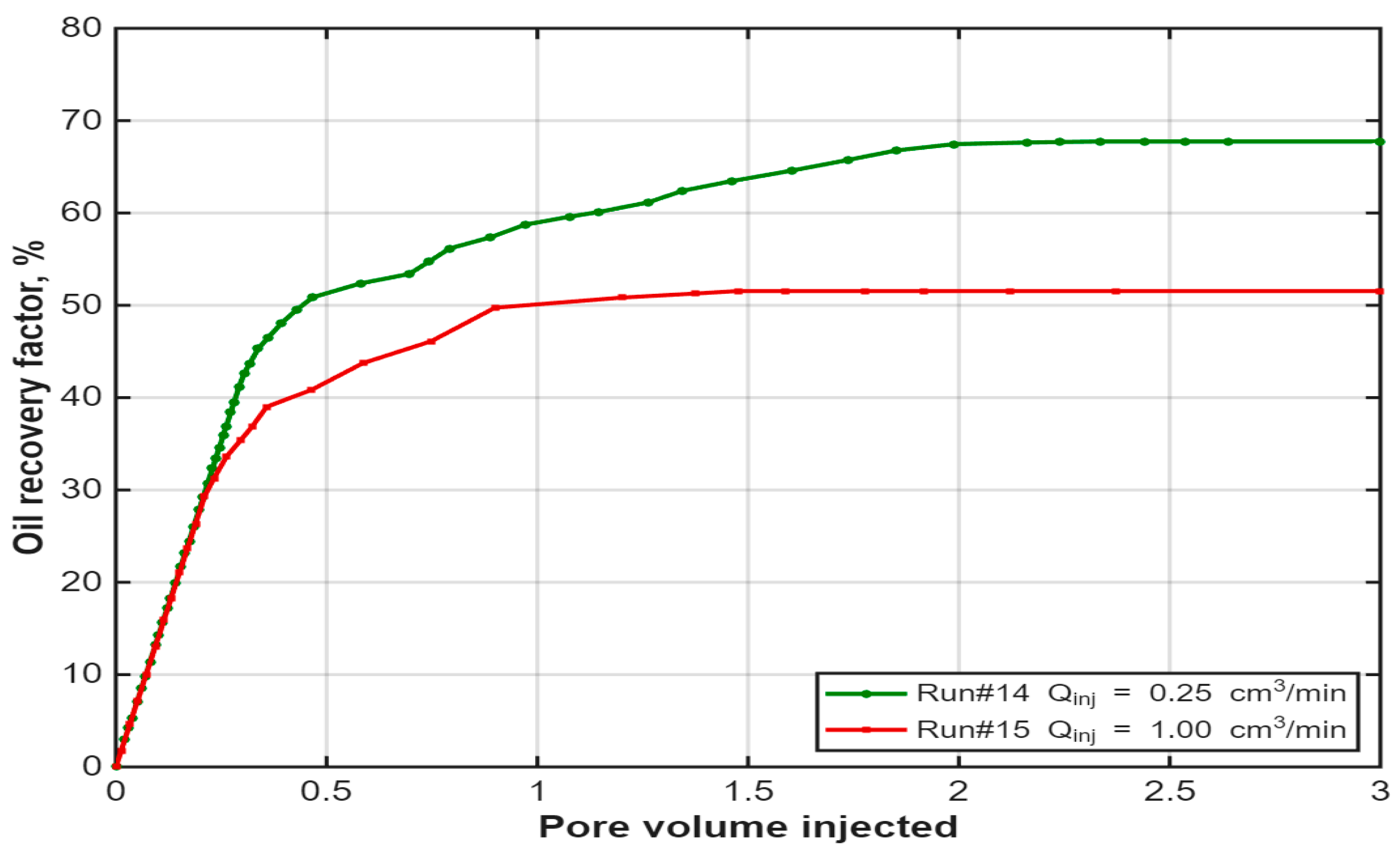

3.6. Effect of Injection Rate

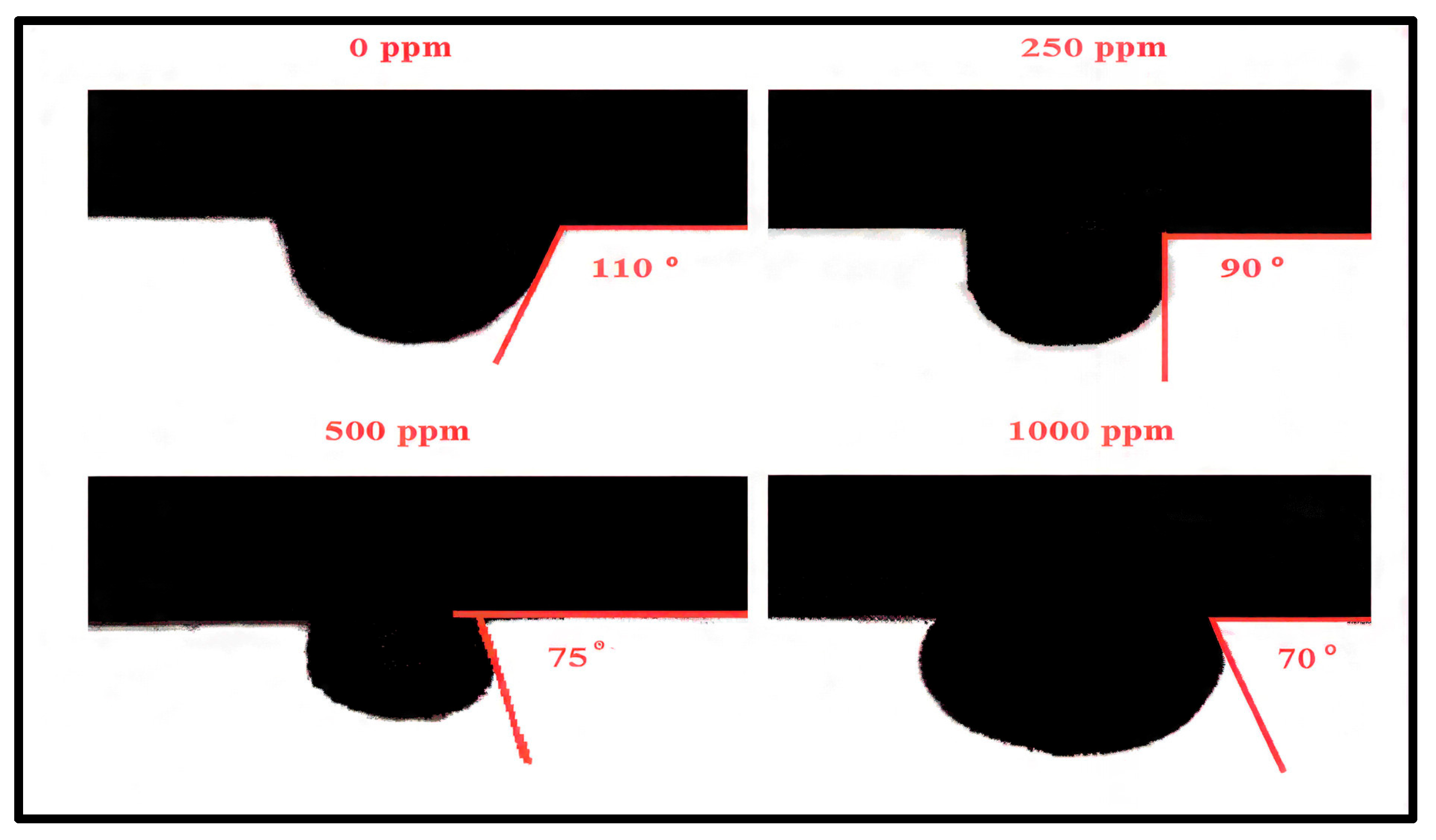

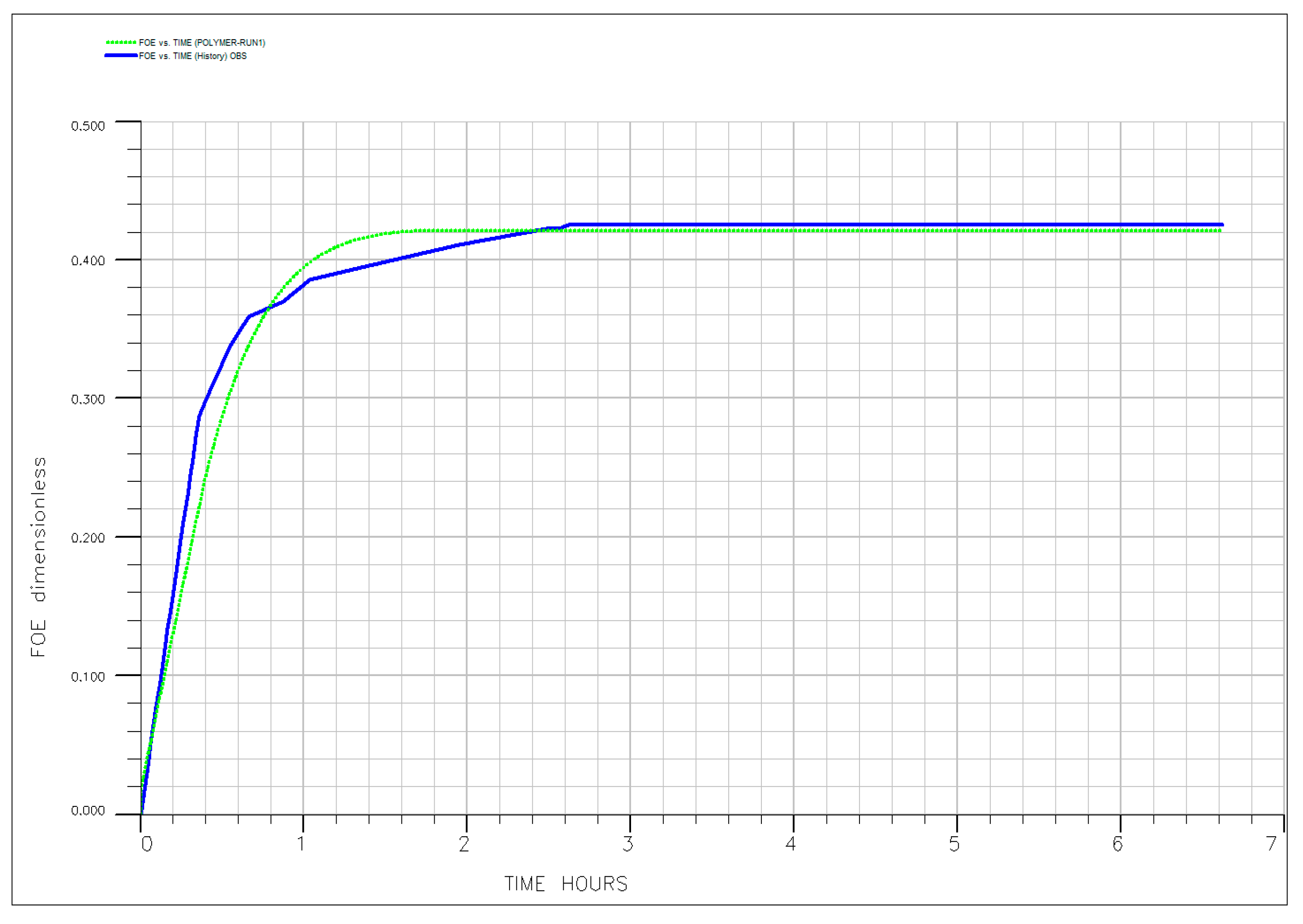

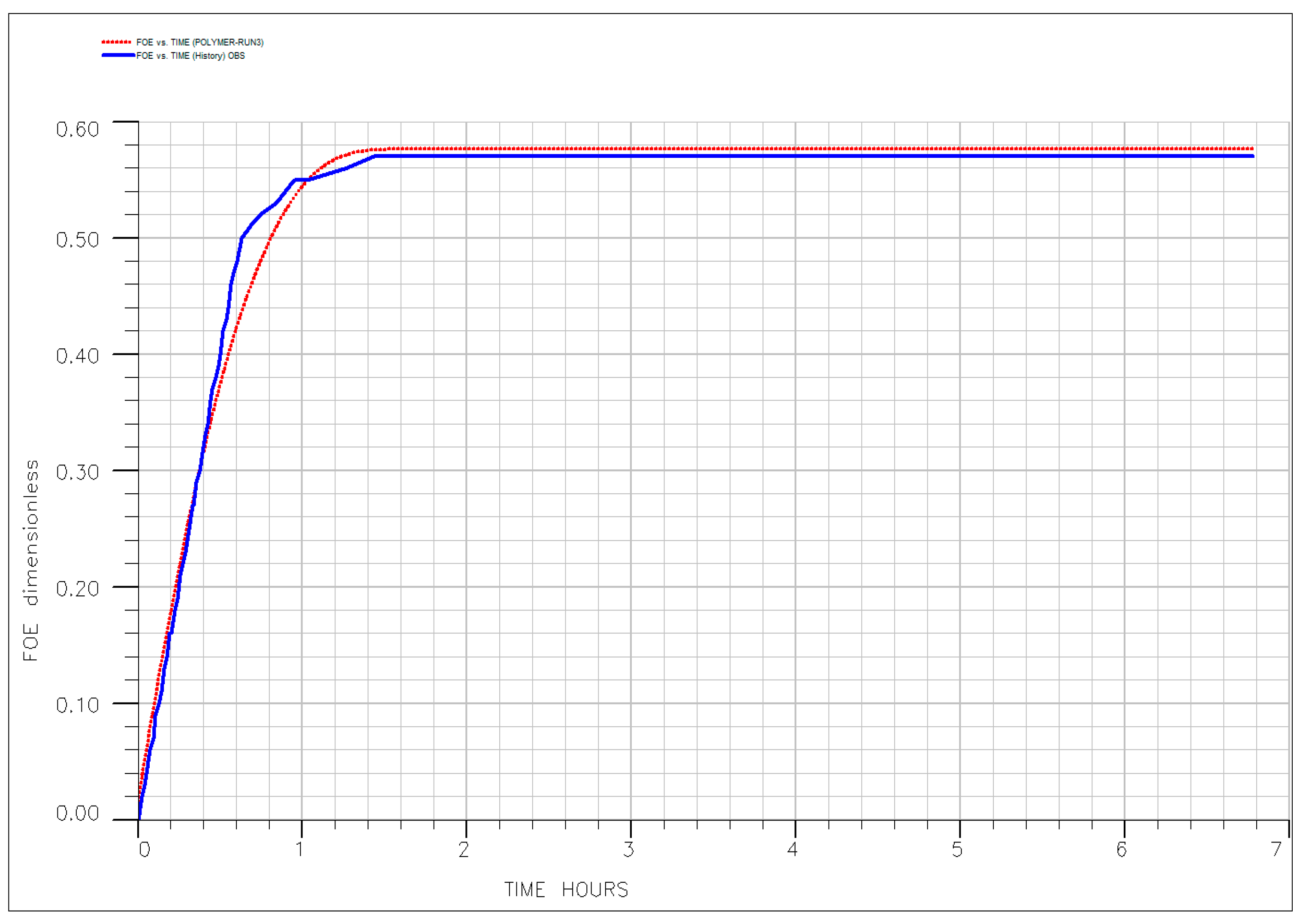

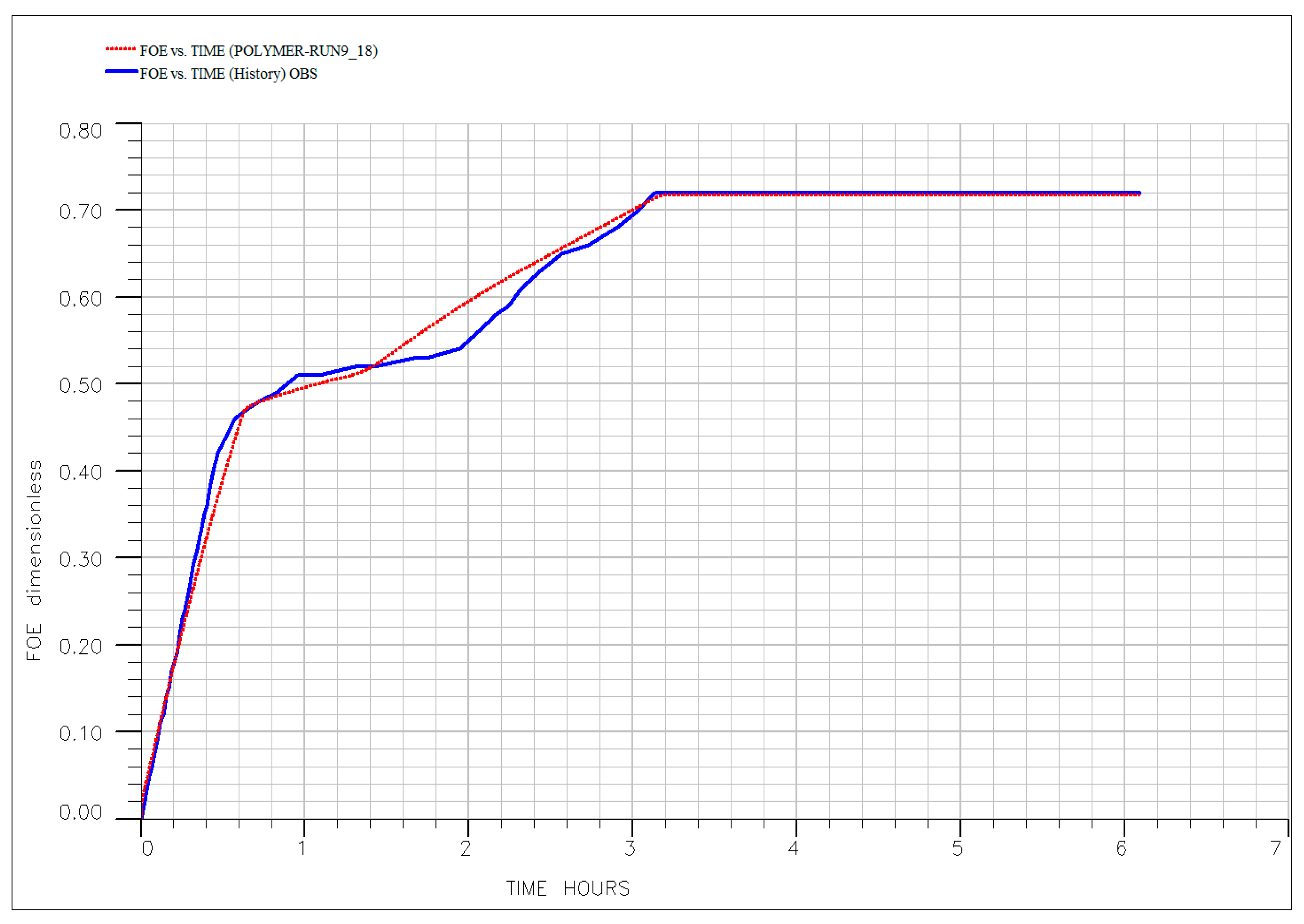

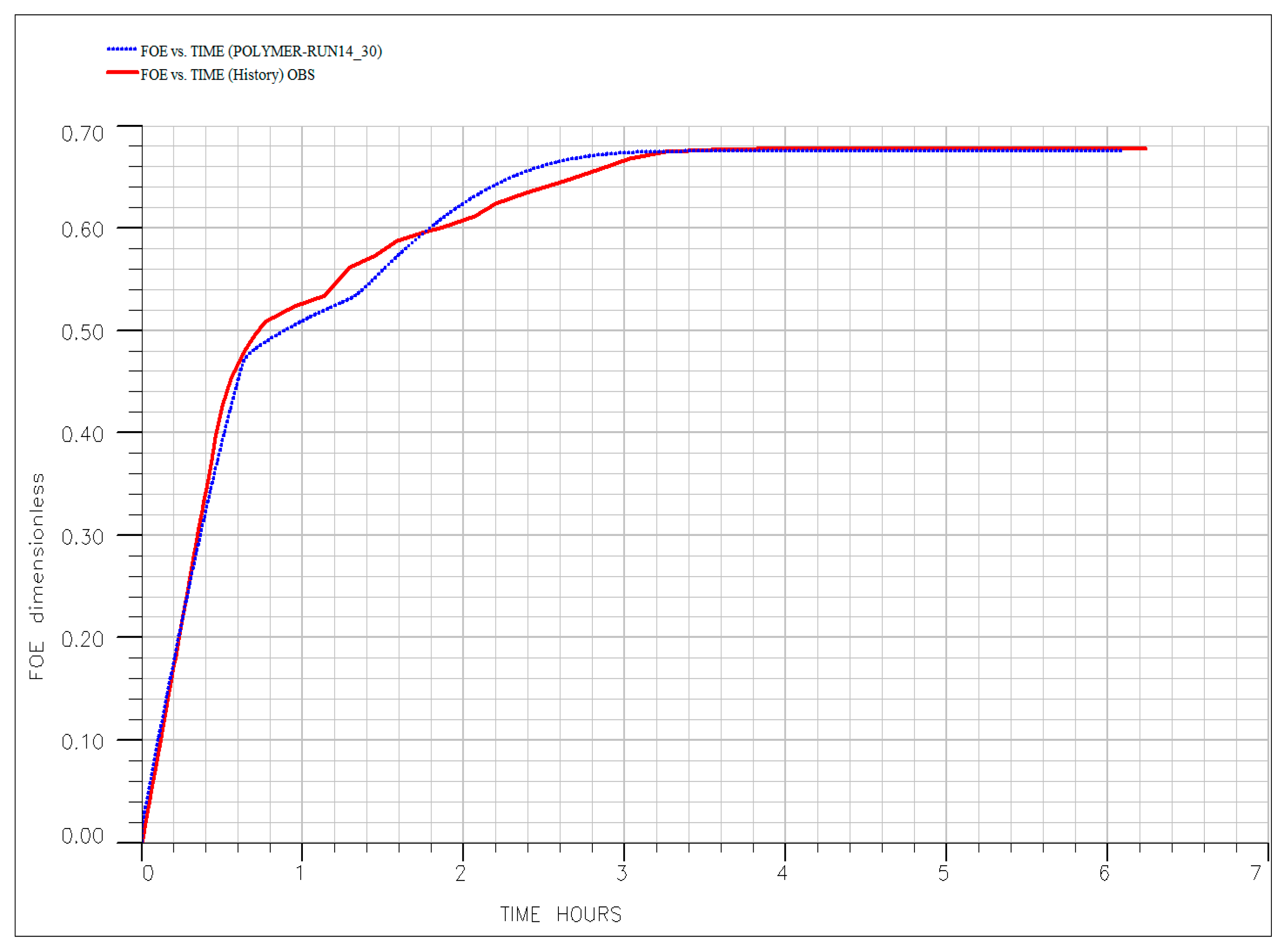

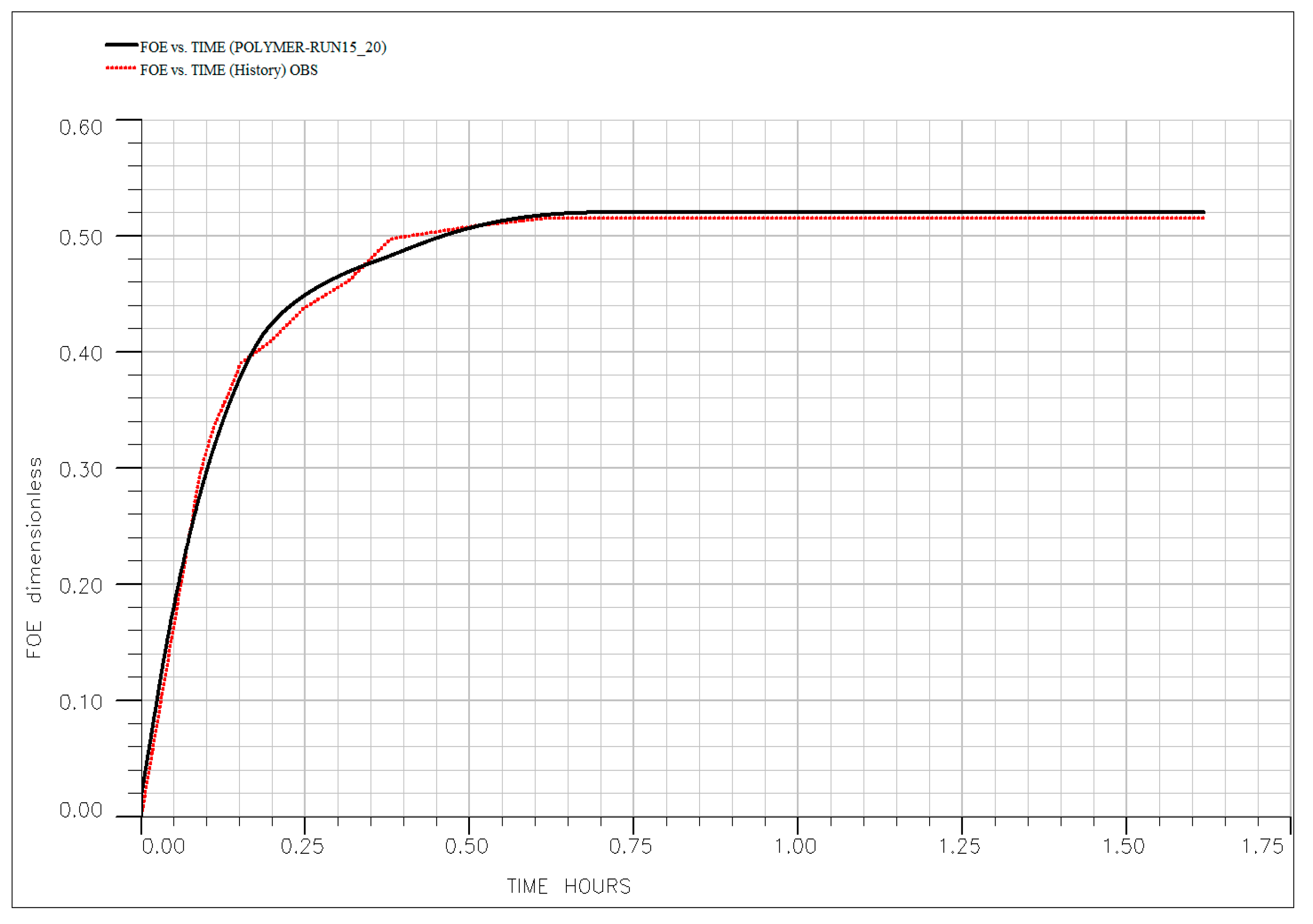

3.7. Mechanistic Interpretation and History Matching

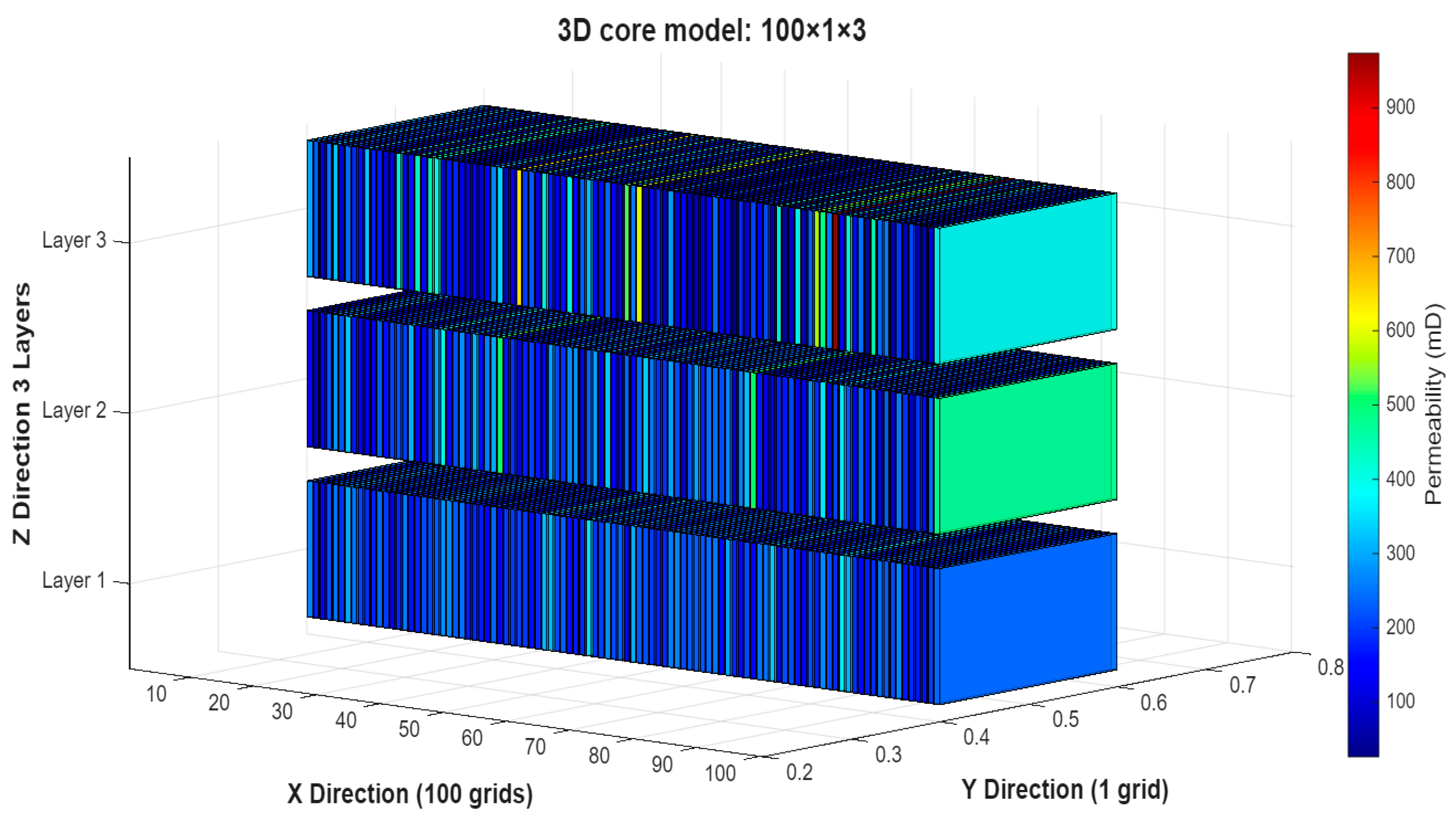

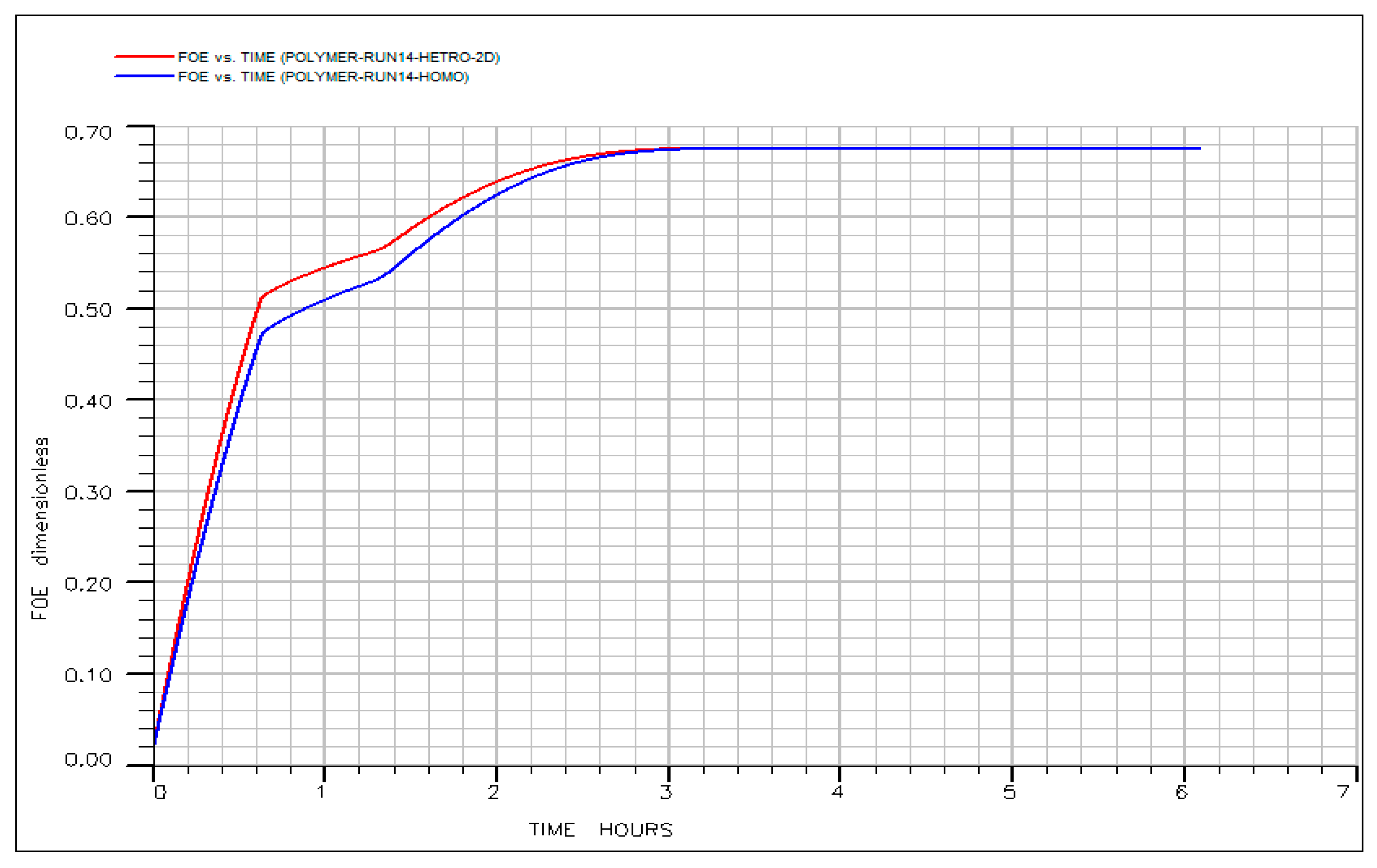

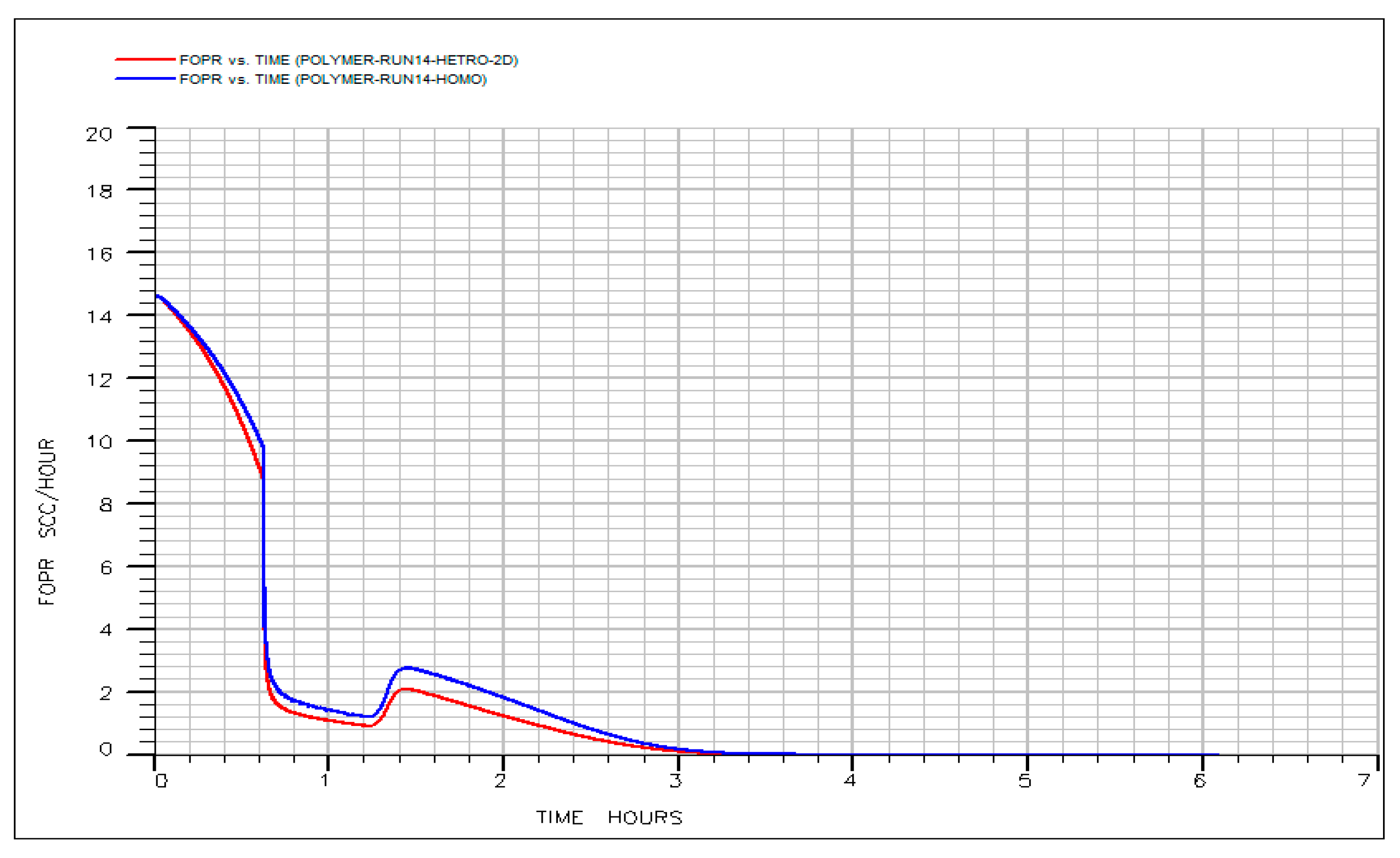

3.8. Robustness of the Optimized IL-HPAM Process to Stratified Permeability Variation

4. Conclusions

- (i)

- The identification of an optimal injection sequence—0.4 PV of Ammoeng 102 IL followed by 0.4 PV of HPAM (500 ppm) in diluted formation brine (20% salinity)—which delivers up to 15% OOIP incremental recovery over IL flooding alone;

- (ii)

- Clear mechanistic deconvolution confirming a dual displacement process: IL-induced microscopic oil mobilization (via wettability alteration and IFT reduction) followed by HPAM-driven macroscopic sweep improvement (via mobility control and flow diversion);

- (iii)

- Robust performance in a 3D heterogeneous layered model, demonstrating scalability and predictive capability for field-scale application.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Green, D.W.; Willhite, G.P. Enhanced Oil Recovery, 2nd ed.; Society of Petroleum Engineers: Houston, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, T. Reservoir Engineering Handbook; Gulf Professional Publishing: Woburn, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lake, L.W.; Johns, R.; Rossen, B.; Pope, G.A. Fundamentals of Enhanced Oil Recovery; Society of Petroleum Engineers: Richardson, TX, USA, 2014; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, F.A.T.; Moreno, R.B.Z.L. The effectiveness of computed tomography for the experimental assessment of surfactant-polymer flooding. Oil Gas Sci. Technol.—Rev. D’ifp Energ. Nouv. 2020, 75, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.J. Modern Chemical Enhanced Oil Recovery: Theory and Practice; Gulf Professional Publishing: Woburn, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wever, D.A.Z.; Picchioni, F.; Broekhuis, A.A. Polymers for enhanced oil recovery: A paradigm for structure–property relationship in aqueous solution. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 1558–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seright, R.S.S. Potential for polymer flooding reservoirs with viscous oils. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2010, 13, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hematpour, H.; Mardi, M.; Edalatkhah, S.; Arabjamaloei, R. Experimental study of polymer flooding in low-viscosity oil using one-quarter five-spot glass micromodel. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2011, 29, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochi, T. Flow of non-Newtonian fluids in porous media. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 2010, 48, 2437–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.; Bera, A.; Ojha, K.; Mandal, A. Effects of alkali, salts, and surfactant on rheological behavior of partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide solutions. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2010, 55, 4315–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Seright, R.S.S. Effect of concentration on HPAM retention in porous media. SPE J. 2014, 19, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajri, S.; Mahmood, S.M.; Abdulelah, H.; Akbari, S. An overview on polymer retention in porous media. Energies 2018, 11, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbie, K.S. Polymer-Improved Oil Recovery; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, R.; Lantz, R.B. Inaccessible pore volume in polymer flooding. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 1972, 12, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delshad, M.; Kim, D.H.; Magbagbeola, O.A.; Huh, C.; Pope, G.A.; Tarahhom, F. Mechanistic interpretation and utilization of viscoelastic behavior of polymer solutions for improved polymer-flood efficiency. In Proceedings of the SPE Improved Oil Recovery Conference, Tulsa, OK, USA, 20–23 April 2008; SPE: Houston, TX, USA, 2008; p. SPE-113620. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, P.; Wang, B.; Sun, S.; Hua, D.; Zhao, J. Laboratory experimental study on polymer flooding in high-temperature and high-salinity heavy oil reservoir. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.S.; Sultan, A.; Hussein, I.; Hussain, S.M.; AlSofi, A.M. Screening of surfactants and polymers for high temperature high salinity carbonate reservoirs. In Proceedings of the SPE Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Annual Technical Symposium and Exhibition, Dammam, Saudi Arabia, 23–26 April 2018; SPE: Houston, TX, USA, 2018; p. SPE-192441. [Google Scholar]

- Gbadamosi, A.; Patil, S.; Kamal, M.; Adewunmi, A.; Adeyinka, Y.; Agi, A.; Oseh, J. Application of polymers for Chemical Enhanced Oil Recovery: A review. Polymers 2022, 14, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, G. Thermal stability of high-molecular-weight polyacrylamide aqueous solutions. Polym. Bull. 1981, 5, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitoun, A.; Potie, B. Limiting conditions for the use of hydrolyzed polyacrylamides in brines containing divalent ions. In Proceedings of the SPE International Conference on Oilfield Chemistry, Denver, Colorado, 1–3 June 1983; SPE: Houston, TX, USA, 1983; p. SPE-11785. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, A.Z.; Puspasari, T.; Nugroho, W.A. Polymers for enhanced oil recovery technology. Procedia Chem. 2012, 4, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welton, T. Room-temperature ionic liquids. Solvents for synthesis and catalysis. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 2071–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.D.; Seddon, K.R. Ionic liquids-solvents of the future? Science 2003, 302, 792–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plechkova, N.V.; Seddon, K.R. Applications of ionic liquids in the chemical industry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, J.P.; Welton, T. Room-temperature ionic liquids: Solvents for synthesis and catalysis. 2. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 3508–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domańska, U. Solubilities and thermophysical properties of ionic liquids. Pure Appl. Chem. 2005, 77, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandwani, S.K.; Chakraborty, M.; Bart, H.-J.; Gupta, S. Synergism, phase behaviour and characterization of ionic liquid-nonionic surfactant mixture in high salinity environment of oil reservoirs. Fuel 2018, 229, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.B.; Santos, D.; de Brito, M.P.; Guimarães, R.C.L.; Ferreira, B.M.S.; Freitas, L.S.; de Campos, M.C.V.; Franceschi, E.; Dariva, C.; Santos, A.F.; et al. Microwave demulsification of heavy crude oil emulsions: Analysis of acid species recovered in the aqueous phase. Fuel 2014, 128, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrati, N.; Beigi, A.A.M.; Abdouss, M. Demulsification of water in crude oil emulsion using long chain imidazolium ionic liquids and optimization of parameters. Fuel 2018, 229, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Dahbag, M.S.; Al Quraishi, A.A.; Benzagouta, M.S.; Kinawy, M.M.; Al Nashef, I.M.; Al Mushaegeh, E. Experimental study of use of ionic liquids in enhanced oil recovery. J. Pet. Environ. Biotechnol. 2014, 4, 165. [Google Scholar]

- Hanamertani, A.S.; Pilus, R.M.; Irawan, S. A review on the application of ionic liquids for enhanced oil recovery. In ICIPEG 2016: Proceedings of the International Conference on Integrated Petroleum Engineering and Geosciences, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 15–17 August 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 133–147. [Google Scholar]

- RSaw, K.; Pillai, P.; Mandal, A. Synergistic effect of low saline ion tuned Sea Water with ionic liquids for enhanced oil recovery from carbonate reservoirs. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 364, 120011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, R.; Hartyányi, M.; Bejczi, R.; Bartha, L.; Puskás, S. Recent aspects of chemical enhanced oil recovery. Chem. Pap. 2025, 79, 2695–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiarian, A.; Maghsoudian, A.; Shirazi, M.; Tamsilian, Y.; Kord, S.; Sheng, J.J. Mechanistic investigation of the synergy of a wide range of salinities and ionic liquids for enhanced oil recovery: Fluid–fluid interactions. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 3011–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Han, P.; Chen, Q.; Su, X.; Feng, Y. Comparative study on enhancing oil recovery under high temperature and high salinity: Polysaccharides versus synthetic polymer. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 10620–10628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, N.; Saxena, N.; Laxmi, K.V.D.; Mandal, A. Interfacial behaviour, wettability alteration and emulsification characteristics of a novel surfactant: Implications for enhanced oil recovery. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 187, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TChávez-Miyauchi, E.; Kar, T.; Firoozabadi, A. Synergy of Polymer Mobility Control and Surfactant for Interface Elasticity Increase in Improved Oil Recovery. SPE J. 2025, 30, 6366–6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, M.S.M.; Agi, A.; Nwaichi, P.I.; Ridzuan, N.; Mahat, S.Q.B. Simulation study of polymer flooding performance: Effect of salinity, polymer concentration in the Malay Basin. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 228, 211986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlumberger. ECLIPSE Technical Description; Schlumberger: Houston, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, K.; Yao, J. Reservoir automatic history matching: Methods, challenges, and future directions. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2023, 7, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BinDahbag, M.S.; Hassanzadeh, H.; AlQuraishi, A.A.; Benzagouta, M.S. Suitability of ionic solutions as a chemical substance for chemical enhanced oil recovery—A simulation study. Fuel 2019, 242, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, D.B.; Pope, G.A. Selection and screening of polymers for enhanced-oil recovery. In Proceedings of the SPE Improved Oil Recovery Conference, Tulsa, OK, USA, 20–23 April 2008; SPE: Houston, TX, USA, 2008; p. SPE-113845. [Google Scholar]

- Vermolen, E.C.; Van Haasterecht, M.J.; Masalmeh, S.K.; Faber, M.J.; Boersma, D.M.; Gruenenfelder, M. Pushing the envelope for polymer flooding towards high-temperature and high-salinity reservoirs with polyacrylamide based ter-polymers. In Proceedings of the SPE Middle East Oil and Gas Show and Conference, Manama, Bahrain, 25–28 September 2011; SPE: Houston, TX, USA, 2011; p. SPE-141497. [Google Scholar]

- Khamis, M.A.; Omer, O.A.; Kinawy, M.M. Predicting the optimum concentration of partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide polymer in brine solutions for better oil recovery, experimental study. In Proceedings of the SPE Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Annual Technical Symposium and Exhibition, Dammam, Saudi Arabia, 23–26 April 2018; SPE: Houston, TX, USA, 2018; p. SPE-192281. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Seright, R.S. Hydrodynamic retention and rheology of EOR polymers in porous media. In Proceedings of the SPE International Conference on Oilfield Chemistry, Denver, Colorado, 1–3 June 1983; SPE: Houston, TX, USA, 2015; p. D011S003R006. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, N.; Wen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, D.; He, W.; Chen, Y. Polymer flooding in high-temperature and high-salinity heterogeneous reservoir by using diutan gum. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 188, 106902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, A.; Hincapie, R.E.; Tahir, M.; Langanke, N.; Ganzer, L. On the role of polymer viscoelasticity in enhanced oil recovery: Extensive laboratory data and review. Polymers 2020, 12, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.; Tao, J.; Lyu, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, H.; Meng, E.; et al. Recent advances in polymer flooding in China. Molecules 2022, 27, 6978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seright, R.S.; Wang, D. Polymer flooding: Current status and future directions. Pet. Sci. 2023, 20, 910–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, A.; Mushtaq, M.; Al-Shalabi, E.W.; AlAmeri, W.; Mohanty, K.; Masalmeh, S.; AlSumaiti, A.M. Investigating the effects of make-up water dilution and oil presence on polymer retention in carbonate reservoirs. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, M.; Alfazazi, U.; Thomas, N.C.; Al-Shalabi, E.W.; AlAmeri, W.; Masalmeh, S.; AlSumaiti, A. ATBS Polymer Injectivity in 22–86 md Carbonate Cores: Impacts of Polymer Filtration, Mechanical Shearing, and Oil Presence. SPE J. 2025, 30, 2800–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, X.; Tang, X. Reservoir Compatibility and Enhanced Oil Recovery of Polymer and Polymer/Surfactant System: Effects of Molecular Weight and Hydrophobic Association. Polymers 2025, 17, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F.; Huang, B.; Wang, C.; Tang, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Su, Y.; Chen, S.; Wu, X.; Chen, B.; et al. Hydrophobically associating polymers dissolved in seawater for enhanced oil recovery of Bohai offshore oilfields. Molecules 2022, 27, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scerbacova, A.; Sharfan, I.I.B.; Abdulhamid, M.A. Hydrophobically Modified Chitosan-Based Polymers for Enhanced Oil Recovery. CleanMat 2025, 2, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhut, P.R.; Pal, N.; Mandal, A. Characterization of hydrophobically modified polyacrylamide in mixed polymer-gemini surfactant systems for enhanced oil recovery application. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 20164–20177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, R.O.; Oluyemi, G.F.; Officer, S.; Ugwu, J.O. Hydrophobically associating polymers for enhanced oil recovery–Part A: A review on the effects of some key reservoir conditions. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 180, 681–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Alotaibi, M.B.; Fahmi, M.; Patil, S.; Mahmoud, M.; Kamal, M.S.; Hussain, S.M.S. Locally synthesized zwitterionic surfactants as EOR chemicals in sandstone and carbonate. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 43081–43092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Liu, T.; Xu, X.; Yang, J. A Lignin-Based Zwitterionic Surfactant Facilitates Heavy Oil Viscosity Reduction via Interfacial Modification and Molecular Aggregation Disruption in High-Salinity Reservoirs. Molecules 2025, 30, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Liang, M.-Y.; Lang, J.-Q.; Mtui, H.I.; Yang, S.-Z.; Mu, B.-Z. A new thermal-tolerant bio-based zwitterionic surfactant for enhanced oil recovery. Green Mater. 2024, 12, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liang, M.-Y.; Lang, J.-Q.; Mtui, H.I.; Yang, S.-Z.; Mu, B.-Z. A new bio-based zwitterionic surfactant with improved interfacial activity by optimizing hydrophilic head. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 30067–30075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimov, D.; Imekova, G.; Toktarbay, Z.; Nuraje, N. Experimental and numerical simulation studies of the zwitterionic polymers for enhanced oil recovery. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, B.G.; Duncke, A.C.P.; Pérez-Gramatges, A.; Percebom, A.M. Impact of Residual Zwitterionic Surfactants on Topside Water–Oil Separation of Pre-Salt Light Crude Oil Emulsions. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 50340–50348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golab, E.G. Evaluation of zwitterionic and polymeric surfactant adsorption for enhanced oil recovery in sandstone reservoirs with high salinity conditions. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2025, 15, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, U.E. Nanotechnology in Enhanced oil Recovery: A Review of Current Research. Chem. Sci. Int. J. 2024, 33, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.S.M. Nanotechnology Applications in Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR). Int. J. Sci. Res. Manag. 2024, 12, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Masry, J.F.; Bou-Hamdan, K.F.; Abbas, A.H.; Martyushev, D.A. A comprehensive review on utilizing nanomaterials in enhanced oil recovery applications. Energies 2023, 16, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, G.; Wang, J.; Taqi, A.A.M.; Liang, T. Combined Effects of Nanofluid and Surfactant on Enhanced Oil Recovery: An Experimental Study. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 52375–52386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tliba, L.; Sagala, F.; Hethnawi, A.; Glover, P.W.J.; Menzel, R.; Hassanpour, A. Surface-modified silica nanoparticles for enhanced oil recovery in sandstone cores. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 413, 125815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; Fan, Z.; Liu, Q.; Qiao, S.; Cai, L.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sun, A. Research progress in nanofluid-enhanced oil recovery technology and mechanism. Molecules 2023, 28, 7478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bila, A.; Stensen, J.Å.; Torsæter, O. Experimental investigation of polymer-coated silica nanoparticles for enhanced oil recovery. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bila, A.; Stensen, J.Å.; Torsæter, O. Polymer-functionalized silica nanoparticles for improving water flood sweep efficiency in Berea sandstones. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Symposium of the Society of Core Analysts (SCA 2019), Pau, France, 26–30 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goharzadeh, A.; Fatt, Y.Y.; Sangwai, J.S. Effect of TiO2–SiO2 hybrid nanofluids on enhanced oil recovery process under different wettability conditions. Capillarity 2023, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Yu, G.; Wu, K.; Dong, X.; Chen, Z. Polymer flooding in heterogeneous heavy oil reservoirs: Experimental and simulation studies. Polymers 2021, 13, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meybodi, H.E.; Kharrat, R.; Ghazanfari, M.H. Effect of heterogeneity of layered reservoirs on polymer flooding: An experimental approach using 5-spot glass micromodel. In Proceedings of the SPE Europec Featured at EAGE Conference and Exhibition, Rome, Italy, 9–12 June 2008; SPE: Houston, TX, USA, 2008; p. SPE-113820. [Google Scholar]

- Computer Modelling Group Ltd. STARS User Guide; CMG: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, M.R.; Longstaff, W.J. The development, testing, and application of a numerical simulator for predicting miscible flood performance. J. Pet. Technol. 1972, 24, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyes, A.B.; Caudle, B.H.; Erickson, R.A. Oil production after breakthrough as influenced by mobility ratio. J. Pet. Technol. 1954, 6, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahbag, M.S.B. Effect of Ionic Liquids on the Efficiency of Crude Oil Recovery; LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Omer, O.; Kinawy, M.; Khamis, M. Effect of Using Polymer Buffer on Efficiency of Crude Oil Recovery by Ionic Liquids. Int. J. Pet. Petrochem. Eng. 2017, 3, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzagouta, M.S.; AlNashef, I.M.; Karnanda, W.; Al-Khidir, K. Ionic liquids as novel surfactants for potential use in enhanced oil recovery. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 30, 2108–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahbag, M.S.B.; Hossain, M.E.; AlQuraishi, A.A. Efficiency of Ionic Liquids as an Enhanced Oil Recovery Chemical: Simulation Approach. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 9260–9265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, S.; Velusamy, S.; Nair, V.C.; Sharma, T.; Sangwai, J.S. Interfacial tension of crude oil-water system with imidazolium and lactam-based ionic liquids and their evaluation for enhanced oil recovery under high saline environment. Fuel 2017, 191, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EOR Technology | Primary Mechanism | Key Advantages (HTHS) | Critical Limitations and Challenges | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATBS copolymers | Steric hindrance and charge repulsion (sulfonate groups) | Industry standard for high thermal stability (>100 °C) and shear resistance. | High retention cost: adsorption doubles in high-salinity seawater compared to diluted brine, threatening project economics. Injectivity: prone to filtration issues in tight carbonates (<100 mD). | Seright and Wang (2023) [49]; Sebastian et al. (2024) [50]; Mushtaq et al. (2021) [51]. |

| Hydrophobically associating polymers (HAPs) | Associative intermolecular networking | Enhanced viscosity at lower concentrations; suited for offshore conditions (e.g., Bohai field). | Solubility sensitivity: complex synthesis; prone to phase separation or precipitation in hyper-saline brines if not perfectly tuned. | Liu et al. (2025) [52]; Yi et al. (2022) [53]; Afolabi et al. (2019) [56]. |

| Zwitterionic surfactants | IFT reduction and wettability alteration | Excellent solubility in high salinity; noprecipitation (unlike anionic surfactants). | Topside separation issues: residual surfactants stabilize water-in-oil emulsions, complicating dehydration and increasing OPEX. Adsorption: adsorption on sandstone increases linearly with salinity. | Deng et al. (2024) [57]; Alvarenga et al. (2025) [62]; Golab (2025) [63]. |

| Nanofluid hybrids (e.g., SiO2, MoS2) | Disjoining pressure and surface modification | Synergistic IFT reduction; wettability alteration to water-wet. | Stability and scalability: long-term dispersion stability is difficult in high salinity (agglomeration risks); functionalized nanofluids are expensive. | Wen et al. (2025) [67]; Rizvi (2024) [65]; Tong et al. (2023) [69]. |

| Hybrid IL–HPAM (this work) | Dual-displacement process: (1) IL-induced wettability alteration and IFT reduction → microscopic oil mobilization; (2) HPAM-driven mobility control → macroscopic sweep improvement | Cost and Simplicity: Uses standard HPAM (no expensive ATBS); avoids emulsion issues (vs. zwitterionics); scalable (vs. nanofluids). Salinity Management: IL pre-flush enables effective HPAM performance in diluted high-salinity brine (20% formation salinity). | Process Optimization: Requires precise design of IL slug size, HPAM concentration, and salinity zoning. | Current study |

| Physical Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Specific gravity | 0.885 |

| Gravity, °API | 28.37 |

| Density, g/cm3 | 0.883 |

| Viscosity, cp | 23.0 |

| Asphaltene content, % | 9.60 * |

| Asphaltene carbon content, % | 81.29 * |

| Asphaltene hydrogen content, % | 9.13 * |

| Asphaltene nitrogen content, % | 0.70 * |

| Asphaltene other elements content % | 8.88 * |

| Run No. | Diameter, cm | Length, cm | Bulk Volume, cm3 | Dry Weight, gm | Saturated Weight, gm | Pore Volume, cm3 | Porosity, % | Absolute Permeability, md |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 3.78 | 11.53 | 129.34 | 274.0 | 302.9 | 25.08 | 19.39 | 246 |

| #2 | 3.78 | 11.44 | 128.33 | 273.8 | 302.8 | 25.16 | 19.61 | 243 |

| #3 | 3.78 | 11.82 | 132.65 | 282.0 | 311.7 | 25.77 | 19.43 | 233 |

| #4 | 3.78 | 12.04 | 135.06 | 284.8 | 315.9 | 26.98 | 19.98 | 240 |

| #5 | 3.78 | 11.69 | 131.13 | 281.8 | 312.1 | 26.29 | 20.05 | 217 |

| #6 | 3.79 | 10.82 | 122.07 | 257.3 | 284.7 | 23.77 | 19.48 | 215 |

| #7 | 3.79 | 9.90 | 111.69 | 235.9 | 260.8 | 21.61 | 19.34 | 225 |

| #8 | 3.79 | 11.56 | 130.42 | 275.4 | 304.4 | 25.16 | 19.29 | 204 |

| #9 | 3.84 | 10.72 | 124.15 | 258.2 | 285.3 | 23.51 | 18.94 | 221 |

| #10 | 3.80 | 10.25 | 115.89 | 243.4 | 269.1 | 22.30 | 19.24 | 216 |

| #11 | 3.85 | 11.26 | 131.03 | 271.8 | 301.6 | 25.86 | 19.73 | 202 |

| #12 | 3.78 | 11.83 | 132.76 | 279.7 | 310.1 | 26.38 | 19.87 | 210 |

| #13 | 3.69 | 12.03 | 128.60 | 259.7 | 287.6 | 24.21 | 18.82 | 211 |

| #14 | 3.80 | 11.45 | 129.52 | 273.3 | 301.6 | 24.56 | 18.96 | 209 |

| #15 | 3.81 | 11.31 | 128.61 | 282.0 | 311.2 | 25.34 | 19.70 | 212 |

| Run No. | Q, cm3/min | T, °F (°C) | IL Solution PV | HPAM Solution PV | PC, ppm | HPAM Solution Salinity, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #01 | 0.25 | 140 (60) | 0.0 | 20% salinity brine was injected directly after ionic liquid solution without polymer solution injection. | ||

| #02 | 0.25 | 140 (60) | 0.2 | |||

| #03 | 0.25 | 140 (60) | 0.4 | |||

| #04 | 0.25 | 140 (60) | 0.6 | |||

| #05 | 0.25 | 140 (60) | 0.8 | |||

| #06 | 0.25 | 140 (60) | 1.0 | |||

| #07 | 0.25 | 140 (60) | 1.5 | |||

| #08 | 0.25 | 140 (60) | 3.9 * | |||

| #09 | 0.25 | 140 (60) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 500 | 0 |

| #10 | 0.25 | 140 (60) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 500 | 20 |

| #11 | 0.25 | 140 (60) | 0.4 | 0.3 | 500 | 0 |

| #12 | 0.25 | 140 (60) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1000 | 0 |

| #13 | 0.25 | 167 (75) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 500 | 0 |

| #14 | 0.25 | 194 (90) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 500 | 0 |

| #15 | 1.00 | 194 (90) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 500 | 0 |

| Run No. | Injected Ionic Liquid Slug Size/PV | Connate Water Saturation (Swc), % | Residual Oil Saturation (Sor), % | Ultimate Oil Recovery (RFult), % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 0.0 | 25.42 | 42.87 | 42.52 |

| #2 | 0.2 | 27.07 | 37.72 | 48.29 |

| #3 | 0.4 | 27.70 | 31.24 | 56.79 |

| #4 | 0.6 | 22.47 | 29.83 | 61.52 |

| #5 | 0.8 | 25.18 | 26.02 | 65.23 |

| #6 | 1.0 | 25.67 | 24.40 | 67.18 |

| #7 | 1.5 | 26.54 | 23.10 | 68.56 |

| #8 | 3.9 | 25.80 | 22.77 | 69.31 |

| Parameter | Unit | Optimum/Used Value | Role in Recovery Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Injection concentration | kg/m3 | 0.4–0.5 | Balances viscosity gain with chemical cost. |

| Viscosity multiplier | - | 4.5–5.0 (at 0.4–0.5 kg/m3) | Primary driver for mobility control and sweep improvement. |

| Max. adsorption capacity | kg/kg-rock | 0.012 (0.5 kg/m3) | Defines chemical loss; low value aids deep propagation. |

| Residual resistance factor | - | 2.633 | Indicates minimal permeability reduction; favors injectivity over diversion. |

| Inaccessible pore volume | fraction | 0.08 | Causes faster polymer front velocity, improving economic efficiency. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Khamis, M.A.; Omer, O.A.; Altawati, F.S.; Almobarky, M.A. A Hybrid Ionic Liquid–HPAM Flooding for Enhanced Oil Recovery: An Integrated Experimental and Numerical Study. Polymers 2026, 18, 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030359

Khamis MA, Omer OA, Altawati FS, Almobarky MA. A Hybrid Ionic Liquid–HPAM Flooding for Enhanced Oil Recovery: An Integrated Experimental and Numerical Study. Polymers. 2026; 18(3):359. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030359

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhamis, Mohammed A., Omer A. Omer, Faisal S. Altawati, and Mohammed A. Almobarky. 2026. "A Hybrid Ionic Liquid–HPAM Flooding for Enhanced Oil Recovery: An Integrated Experimental and Numerical Study" Polymers 18, no. 3: 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030359

APA StyleKhamis, M. A., Omer, O. A., Altawati, F. S., & Almobarky, M. A. (2026). A Hybrid Ionic Liquid–HPAM Flooding for Enhanced Oil Recovery: An Integrated Experimental and Numerical Study. Polymers, 18(3), 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030359