Mechanical Properties and Failure Mechanism of a Carbon Fiber/Silicone Rubber High-Temperature Flexible Textile Composite

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Uniaxial Tensile Test and Mechanical Properties Analysis of High-Temperature Flexible Composites at Room Temperature

2.1. Uniaxial Tensile Specimens

2.2. Uniaxial Tensile Test Results

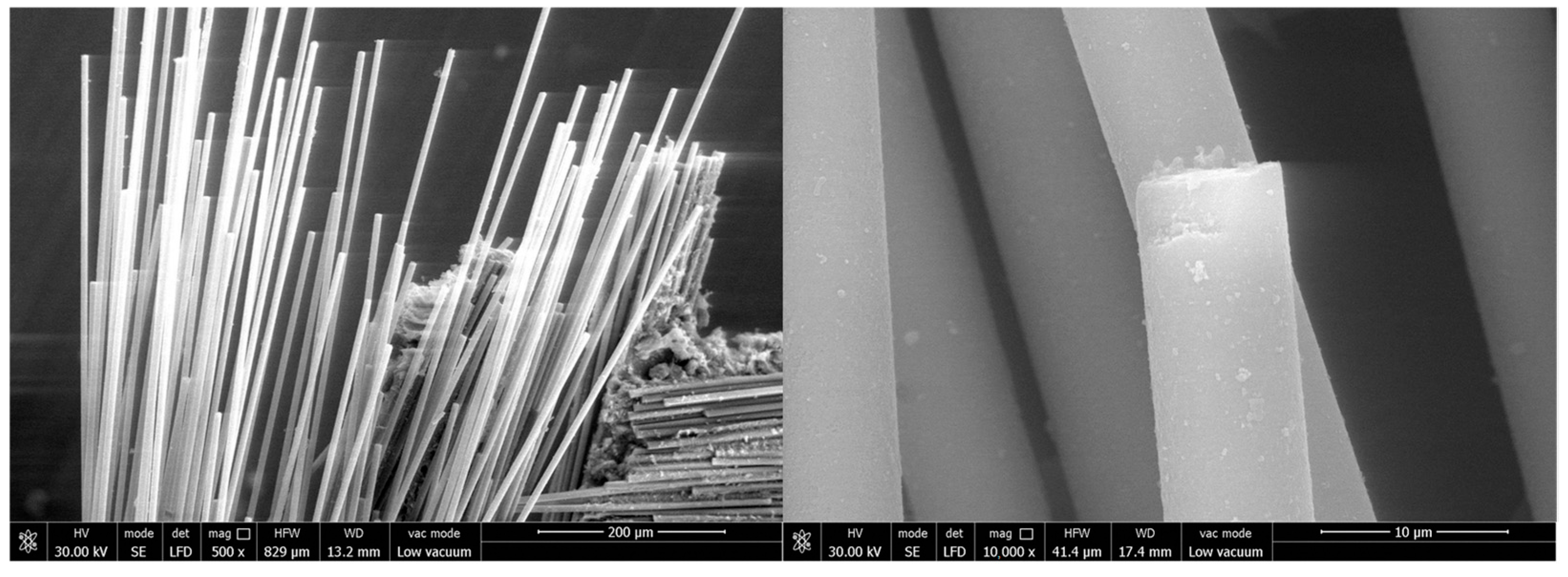

2.3. Study on Failure Modes and Mechanisms

3. High-Temperature Mechanical Properties Test and Failure Analysis of High-Temperature-Resistant Flexible Composites

3.1. Wind Tunnel Test Scheme

3.2. Results and Discussion

3.2.1. Design Status 1

3.2.2. Design Status 2

3.2.3. Design Status 3

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The mechanical properties of the flexible composite are related to the crimp degree of the braided structure. The nonlinear mechanical behavior of the flexible composites results from the crimp exchange effect of the yarn, the interaction between the yarn and yarn, and the interaction between the yarn and the matrix.

- (2)

- The tensile anisotropy of flexible composites along different off-axis angles is significant, and the uniaxial tensile failure of flexible composites with different off-axis angles is different.

- (3)

- Under the actual service environment temperature conditions without deformation, the flexible composite can be used for a long time, and no obvious damage occurred in the test part.

- (4)

- Under the triple action of such high temperature, stress caused by wing surface tensioning, and aerodynamic loading, the failure mechanism of the flexible textile composite is dominated by mechanical loading at high temperature rather than the conventionally claimed thermal instability. In the high-temperature mechanical properties test, no obvious high-temperature oxidation or erosion characteristics were observed on the surface or cross-section of the quartz fiber flexible composite and carbon fiber flexible composite fibers of the specimens, and the fracture or cracking areas were all mechanical fractures.

- (5)

- In the raised state, the surface of the quartz fiber flexible composite and carbon fiber flexible composite specimens form stagnation points, and the protruding position of the material is still damaged under low state heat flow condition.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Xi, F. Optimal design and analysis of a deformable mechanism for a redundantly driven variable swept wing. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 146, 108993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Hou, S.; Xia, Q.; Tan, H. Structural design and dynamic analysis of an inflatable delta wing. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 139, 108371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgens, B.; Birchall, M. Form and function: The significance of material properties in the design of tensile fabric structures. Eng. Struct. 2012, 44, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambroziak, A.; Kłosowski, P. Mechanical testing of technical woven fabrics. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2013, 32, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Li, K.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, Y. Fracture Failure Analysis of Central Tearing Behavior and a Novel Tearing Strength Model for Flexible Composites. Polym. Compos. 2025, early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.P.; Li, Y.F.; Liu, L.B. Failure properties of flexible composite under trouser-shaped tests. J. Compos. Mater. 2022, 56, 2147–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxe, K.; Kurten, R. Investigation about the temperature-depending stress-strain behaviour of PTFE-coated glass fabrics at usual treatment temperatures. Bauingenieur 1992, 67, 291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, Y. Mechanical properties of PTFE coated fabrics. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2010, 29, 3624–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbonneau, L.; Polak, M.A.; Penlidis, A. Mechanical properties of ETFE foils: Testing and modelling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 60, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.D.; Guo, K.; Chen, C.; Chang, M.Z.; Wang, R.Z.; Tang, E.L. Thermal-dynamic response of flexible composite structures under combined thermal flux and tensile loading. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 210, 108345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.Q.; Fang, G.D.; Xu, C.H.; Chen, S. Tensile behavior and deformation mechanisms of SiC twill woven fabric at room temperature and high-temperature oxidation environment. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 60555–60564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, W.; Merkel, D.; Sansoz, F.; Fletcher, D. Fracture behavior of woven silicon carbide fibers exposed to high-temperature nitrogen and oxygen plasmas. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 98, 3825–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R.S.; Chater, R.J. Oxidation kinetics strength of Hi-NicalonTM-S SiC fiber after oxidation in dry and wet air. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 100, 4125–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R.S. SiC fiber strength after low pO2 oxidation. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 101, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sun, Z.E.; Gao, Q. Performance-based fire protection design of ruins protection pavilion based on air-supported membrane structure. Procedia. Eng. 2016, 135, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, G.Q.; Zhang, G.W.; Han, R.S. Performance-based fire design of air-supported membrane coal storage shed. Procedia. Eng. 2013, 52, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Zhu, G.Q.; Guo, F.; Gao, Y.J.; Tao, H.J. Effect of DPK flame retardant on combustion characteristics and fire safety of PVC membrane. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2017, 10, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.Y.; Yan, L.W.; Huang, M.Y.; Luo, Y.F.; Chen, Y.; Liang, M.; Zou, H.W.; Heng, Z.G. In-situ constructing SiC frame in silicone rubber to fabricate novel flexible thermal protective polymeric materials with excellent ablation resistance. Polymer 2023, 285, 126234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.X.; Ma, T.; Yuan, W.; Song, H.W. Ablation behavior of the high-silica/phenolic pyramidal lattice-reinforced silicone rubber composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2026, 202, 109507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yu, D.P.; Xu, F.H.; Kong, Y.; Shen, X.D. Flexible silica aerogel composites for thermal insulation under high-temperature and thermal-force coupling conditions. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 6326–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Yan, L.W.; Zhou, C.X.; Heng, Z.G.; Liang, M.; Zou, H.W.; Chen, Y. The effect of layered materials on the ablation resistance and heat insulation performance of liquid silicone rubber. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2022, 33, 2751–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.X.; Yu, Y.H.; An, P. A novel glass fiber–flexible silicone aerogel composite with improvement of thermal insulation, hydrophobicity and mechanical properties. Mater. Lett. 2025, 394, 138626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.F.; Hua, K.R.; Chen, Y.N.; Lyu, D.K.; Li, J.G.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.B.; He, J.H. Lightweight, high-strength SiO2@Al2O3 composite yarns and textiles for high-temperature thermal insulation. Compos. Commun. 2025, 60, 102646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T30161-2013; Coated Fabrics for Membrane Structures. China National Textile and Apparel Council: Beijing, China, 2013.

- GB/T 3923.1-2013; Textiles—Tensile Properties of Fabrics—Part 1: Determination of Maximum Force and Elongation at Maximum Force Using the Strip Method. China National Textile and Apparel Council: Beijing, China, 2013.

| Material Type | Thickness/mm | Area Density (g/m2) | Weave Density (yarns/cm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warp | Weft | |||

| Carbon fiber flexible composite | 0.55 | 715 | 4.28 | 4.25 |

| Quartz fiber flexible composite | 0.28 | 400 | 20 | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, J.; Mei, J.; Ning, H.; Zhuo, Y.; Shan, H.; Meng, F.; Jiang, X. Mechanical Properties and Failure Mechanism of a Carbon Fiber/Silicone Rubber High-Temperature Flexible Textile Composite. Polymers 2026, 18, 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030358

Huang J, Mei J, Ning H, Zhuo Y, Shan H, Meng F, Jiang X. Mechanical Properties and Failure Mechanism of a Carbon Fiber/Silicone Rubber High-Temperature Flexible Textile Composite. Polymers. 2026; 18(3):358. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030358

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Jiandong, Jie Mei, Hui Ning, Yue Zhuo, Hanxiang Shan, Fanfu Meng, and Xueqi Jiang. 2026. "Mechanical Properties and Failure Mechanism of a Carbon Fiber/Silicone Rubber High-Temperature Flexible Textile Composite" Polymers 18, no. 3: 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030358

APA StyleHuang, J., Mei, J., Ning, H., Zhuo, Y., Shan, H., Meng, F., & Jiang, X. (2026). Mechanical Properties and Failure Mechanism of a Carbon Fiber/Silicone Rubber High-Temperature Flexible Textile Composite. Polymers, 18(3), 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030358