Research Advances in Conjugated Polymer-Based Optical Sensor Arrays for Early Diagnosis of Clinical Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Design and Construction of CPs-Based Optical Sensor Arrays

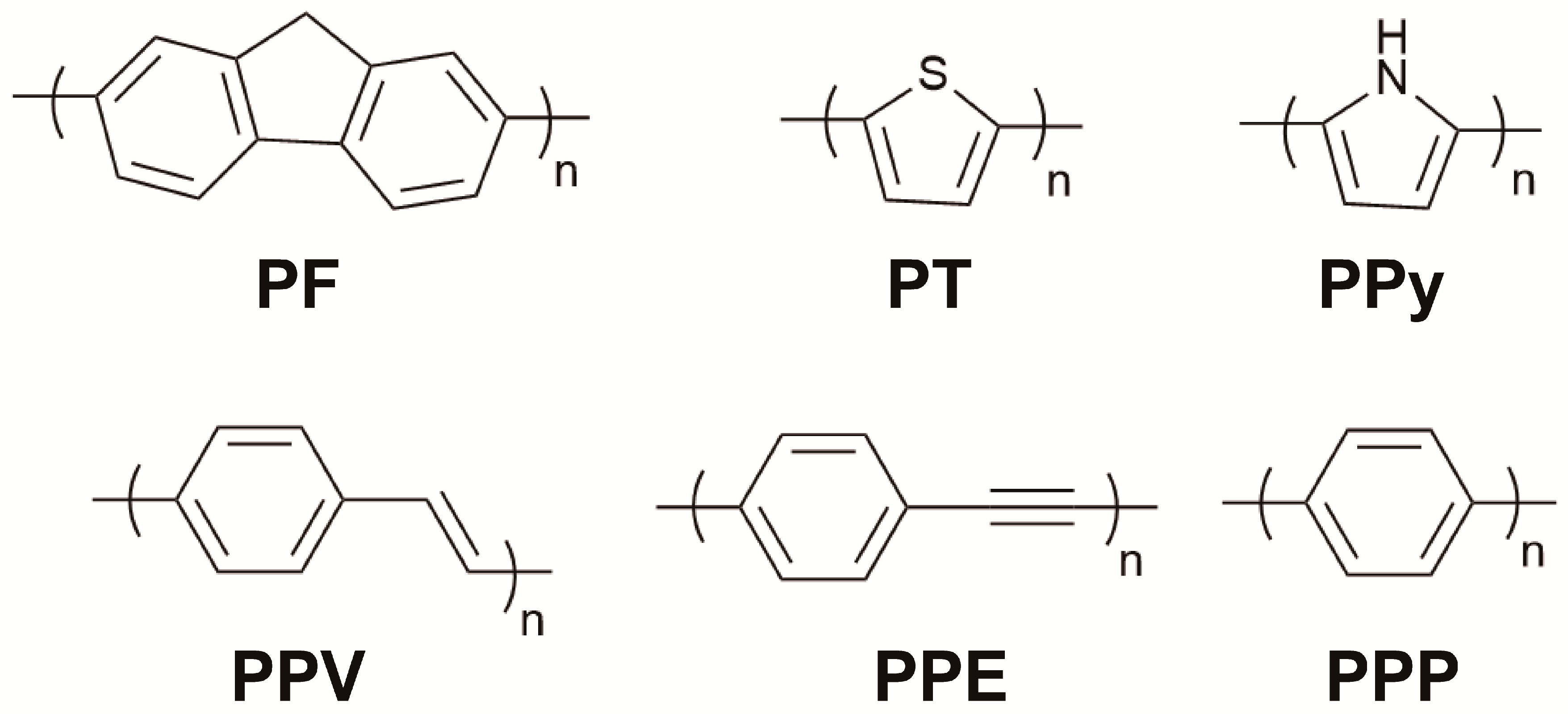

2.1. Categories and Synthesis Methods of CPs

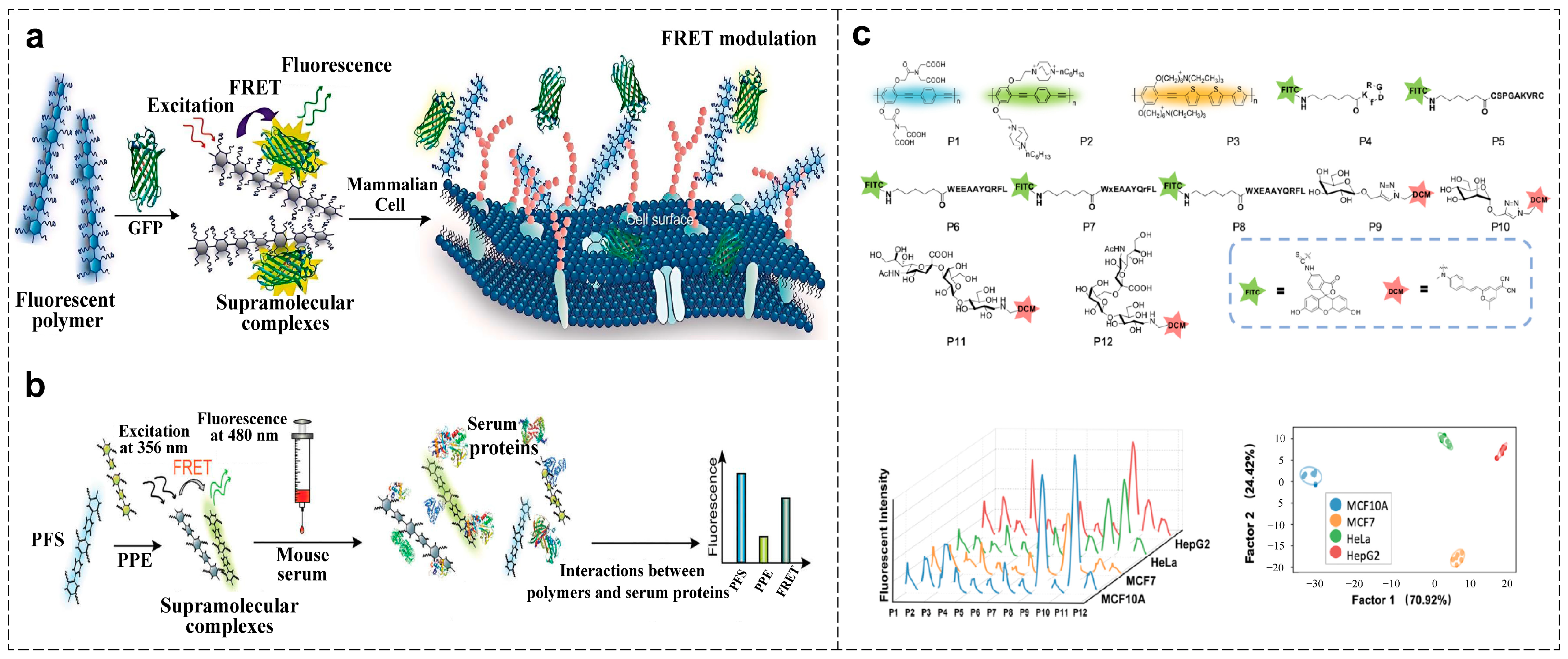

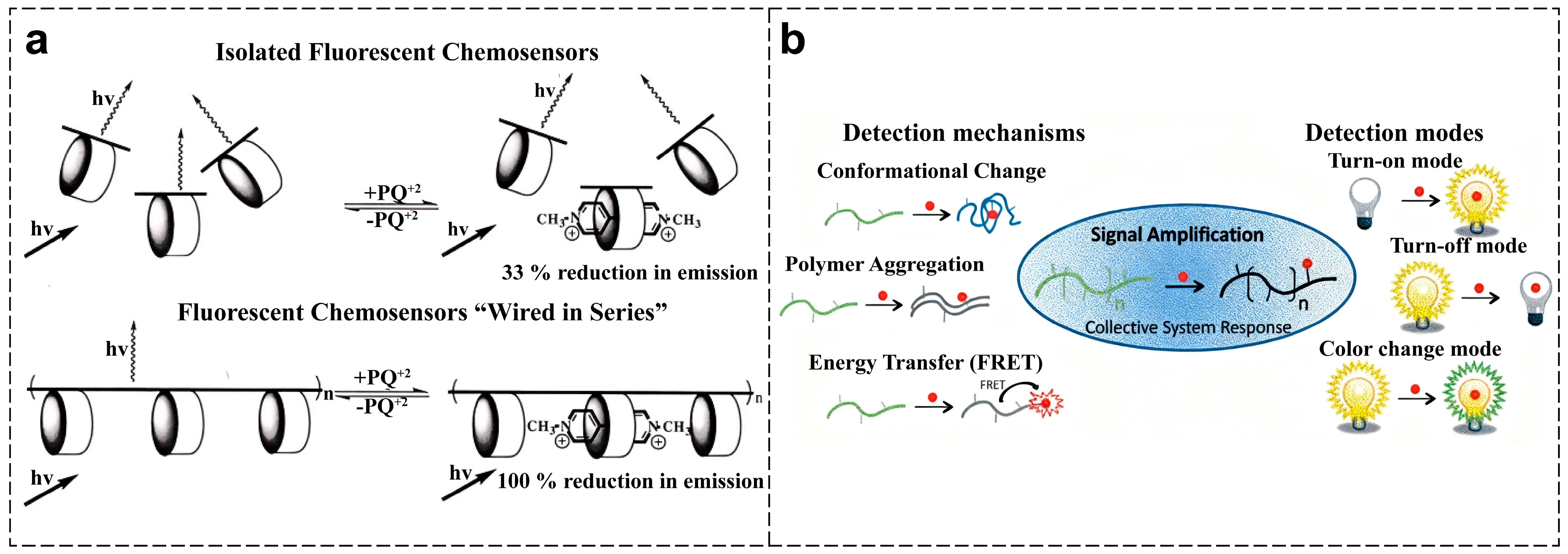

2.2. Fundamental Principles of CPs-Based Sensing

2.3. Strategies for Constructing CPs-Based Optical Sensor Arrays

2.3.1. Functionalization Strategy Based on Main Chain Modification

| Functionalization Strategy | Class of Sensor Molecule | Mechanism | Analytes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Chain Modification | Poly(phenylene vinylidene), fluorene-thiazole copolymers, fluorene-anthracene copolymers | Electron transfer | Explosives | [53] |

| Furan–thiophene, benzothiadiazole–benzene, spirobifluorene–thiophene backbones | FRET | Antibiotics | [49] | |

| PPETE, PPE | Chelation, electrostatic interactions, photoinduced electron transfer | Metal ions | [54] | |

| Acetylene groups, thiophene, bithiophene groups | IFE | Azo dyes | [55] | |

| Side-Chain Modification | Iminodiacetic acid, hexylpropionic acid ester side chains | Aggregation, metal coordination | Metal ions | [50] |

| Acid-containing, nitrogen-containing side chains | Charge distribution, hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity | Milk powder | [56] | |

| Carboxylate side chains | Electrostatic and hydrogen bonding interactions | Biogenic amines | [57] | |

| Microenvironment Regulation | PPE1, PPE2, PPE1 + PPE2 | pH-dependent electrostatic binding | Wine varieties | [58] |

| PAE | pH-modulated charge state and complex stability | Aromatic carboxylic acids | [51] | |

| PTPEs, PPEs | Hydrophobic, electrostatic interactions | Flavonoid | [59] | |

| PPE1/metal ion complexes + GFP-K72 | Synergistic interaction | Amino acids | [60] |

2.3.2. Functionalization Strategy Based on Side-Chain Modification

2.3.3. Construction of Response Patterns Based on Microenvironment Regulation

3. Data Analysis and Pattern Recognition Methods

3.1. Unsupervised Learning Algorithms

3.2. Supervised Learning Algorithms

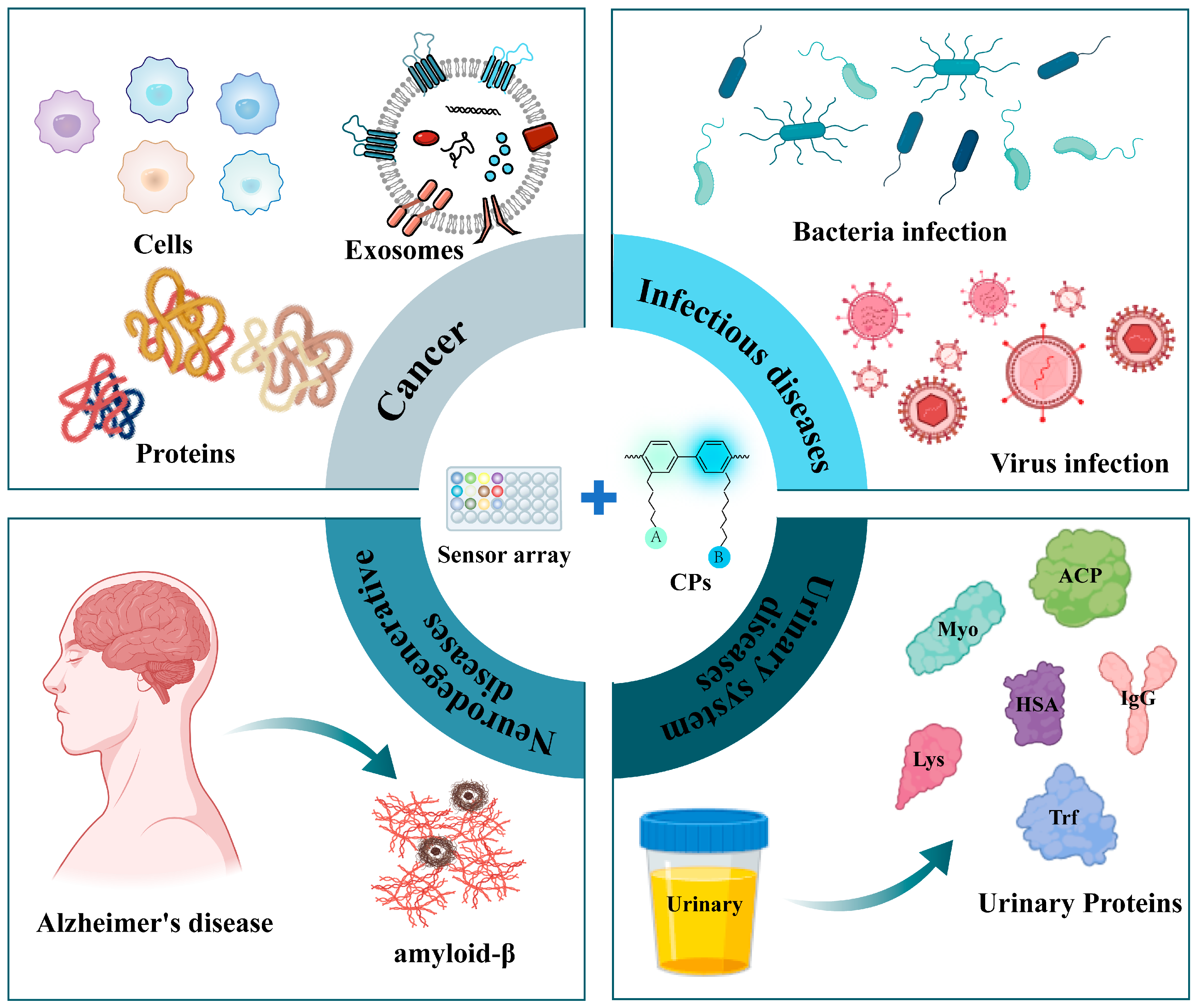

4. Application in Clinical Disease Diagnosis

4.1. Cancer Diagnosis

4.1.1. Cell Phenotype Analysis

4.1.2. Biomarker Detection

4.2. Infectious Diseases Diagnosis

4.3. Neurodegenerative Diseases Diagnosis

4.4. Urinary System Diseases Diagnosis

5. Summary and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Askim, J.R.; Suslick, K.S. The Optoelectronic Nose: Colorimetric and Fluorometric Sensor Arrays. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 231–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, M.; Jia, M. Optical Sensor Arrays for the Detection and Discrimination of Natural Products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2023, 40, 628–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haripriya, P.; Rangarajan, M.; Pandya, H.J. Breath VOC Analysis and Machine Learning Approaches for Disease Screening: A Review. J. Breath Res. 2023, 17, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hu, J.; Hu, N.; Wu, S.; Lu, Y. Machine Learning-Assisted Pd-Au/MXene Sensor Array for Smart Gas Identification. Small Struct. 2025, 6, 2400619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Cui, X.; Du, P.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, X.; Gong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, C. An Integrated Carbon Dots-Based Sensing Platform via Alkali-Assisted Hydrothermal Reaction for pH/Fe(II) Detection and a Sensing Array for Sulfur Species. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 496, 139340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Chen, K.; Zeng, C.; Cao, Q.; Deng, Y.; Yuan, K. In Situ Synthesis of Ordered Macroporous Metal Oxides Monolayer on MEMS Chips: Toward Gas Sensor Arrays for Artificial Olfactory. Small 2025, 21, e03267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Bazan, G.C.; Liu, B. Conjugated-Polymer-Amplified Sensing, Imaging, and Therapy. Chem 2017, 2, 760–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, V.-D.; Tran, V.V. Advances and Innovations in Conjugated Polymer Fluorescent Sensors for Environmental and Biological Detection. Biosensors 2025, 15, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Zhu, C.; Yue, Z.; Hao, Y.; Gao, R.; Wei, J. Rational Design of Signal Amplifying Fluorescent Conjugated Polymers for Environmental Monitoring Applications: Recent Advances and Perspectives. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 499, 215480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hussain, S.; Hao, Y.; Tian, X.; Gao, R. Review—Recent Advances of Signal Amplified Smart Conjugated Polymers for Optical Detection on Solid Support. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 037006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Song, G.; Lin, H.; Bai, H.; Huang, Y.; Lv, F.; Wang, S. Sensing, Imaging, and Therapeutic Strategies Endowing by Conjugate Polymers for Precision Medicine. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2310032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihde, M.H.; Tropp, J.; Diaz, M.; Shiller, A.M.; Azoulay, J.D.; Bonizzoni, M. A Sensor Array for the Ultrasensitive Discrimination of Heavy Metal Pollutants in Seawater. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2112634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Zhao, W.; Qiu, Q.; Xie, A.; Cheng, S.; Jiao, Y.; Pan, X.; Dong, W. Fluorescent Conjugated Microporous Polymer (CMP) Derived Sensor Array for Multiple Organic/Inorganic Contaminants Detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 320, 128448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, Y.; Ito, S.; Zhang, Z.; Lyu, X.; Takizawa, S.; Kubota, R.; Minami, T. Supramolecular Sensor for Astringent Procyanidin C1: Fluorescent Artificial Tongue for Wine Components. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 16236–16240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, X.; Matsumoto, A.; Minami, T. A Polythiophene-Based Chemosensor Array for Japanese Rice Wine (Sake) Tasting. Polym. J. 2021, 53, 1287–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Lu, C.; Niu, C.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, J. Binding Studies of Cationic Conjugated Polymers and DNA for Label-Free Fluorescent Biosensors. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 6211–6218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Zhou, X.; Li, H. Conjugated Polymer Sensitized Hyperbranched Titanium Dioxide Based Photoelectrochemical Biosensor for Detecting AFP in Serum. Surf. Interfaces 2021, 24, 101103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Lu, S.; Qiu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, A.; Gong, S.; Wang, K.; Gao, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, H. Biomimetic Analysis of Neurotransmitters for Disease Diagnosis through Light-Driven Nanozyme Sensor Array and Machine Learning. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e05333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Huang, S.; Guo, W.; Liu, W.; Wen, M.; Shang, L. Multicolor Gold Clusterzyme-Enabled Construction of Ratiometric Fluorescent Sensor Array for Visual Biosensing. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 18873–18879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Khan, M.A.; Yu, Z.; Yang, W.; Zhao, H.; Ye, D.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J. The Identification of Oral Cariogenic Bacteria through Colorimetric Sensor Array Based on Single-Atom Nanozymes. Small 2024, 20, 2403878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Kong, T.; Cao, Z.; Xie, H.; Liang, W.; Wang, Y.; Qian, S.; Chao, J.; et al. Nanozyme Inhibited Sensor Array for Biothiol Detection and Disease Discrimination Based on Metal Ion-Doped Carbon Dots. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 8906–8913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arwani, R.T.; Tan, S.C.L.; Sundarapandi, A.; Goh, W.P.; Liu, Y.; Leong, F.Y.; Yang, W.; Zheng, X.T.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, C.; et al. Stretchable Ionic–Electronic Bilayer Hydrogel Electronics Enable in Situ Detection of Solid-State Epidermal Biomarkers. Nat. Mater. 2024, 23, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Feng, L. Photothermal Conjugated Polymers and Their Biological Applications in Imaging and Therapy. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 4222–4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghi, P.; Coluccini, C. Literature Review on Conjugated Polymers as Light-Sensitive Materials for Photovoltaic and Light-Emitting Devices in Photonic Biomaterial Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodedla, G.B.; Zhang, M.; Wong, W.-Y. Advancements in Molecular Design of Thiazolo[5,4-d]Thiazole-Based Conjugated Polymers and Their Emerging Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2025, 172, 102054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Phung, V.-D.; Tran, V.V. Recent Advances in Conjugated Polymer-Based Biosensors for Virus Detection. Biosensors 2023, 13, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdatiyekta, P.; Zniber, M.; Bobacka, J.; Huynh, T.-P. A Review on Conjugated Polymer-Based Electronic Tongues. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1221, 340114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, K.W.; Abdul Rahim, N.A.; Teh, P.L.; Othman, M.B.H.; Voon, C.H. Unravelling Structure–Property Relationships in Polyfluorene Derivatives for Optoelectronic Advancements: A Review. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 3201–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, B.; Sasaki, Y.; Minami, T. Strategy for Pattern Recognition-driven Optical Chemosensing Based on Polythiophene. Smart Mol. 2024, 2, e20240001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, L.; Yu, D. Progress of Conductive Polypyrrole Nanocomposites. Synth. Met. 2022, 290, 117138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Sari, S.M.; Patah, M.F.A.; Ang, B.C.; Daud, W.M.A.W. A Review of Polymerization Fundamentals, Modification Method, and Challenges of Using PPy-Based Photocatalyst on Perspective Application. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, J.; Dutta, K. A Short Overview on the Synthesis, Properties and Major Applications of Poly(p-Phenylene Vinylene). Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 5139–5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.; Ni, W.; Liu, H.; Han, J. Poly(p-Phenyleneethynylene)s-Based Sensor Array for Diagnosis of Clinical Diseases. ChemMedChem 2025, 20, e202400686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choeichom, P.; Sirivat, A. High Sensitivity Room Temperature Sulfur Dioxide Sensor Based on Conductive Poly(p-Phenylene)/ZSM-5 Nanocomposite. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1130, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Xue, M.; Gu, Q.; Qi, J.; Kang, F.; He, Q.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, Q. Constructing N-Containing Poly(p-Phenylene) (PPP) Films Through A Cathodic-Dehalogenation Polymerization Method. Small Methods 2024, 8, 2400185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberg, J.; Hinkel, F.; Jänsch, D.; Bunz, U.H.F. Chemical Tongues and Noses Based upon Conjugated Polymers. Top. Curr. Chem. 2017, 375, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, C.; Naqvi, S.; Leclerc, M. Strategies for the Synthesis of Water-Soluble Conjugated Polymers. Trends Chem. 2022, 4, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari Gharahcheshmeh, M.; Gleason, K.K. Texture and Nanostructural Engineering of Conjugated Conducting and Semiconducting Polymers. Mater. Today Adv. 2020, 8, 100086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimian, R.; Nardin, C. Conjugated Polymers for Aptasensing Applications. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 3411–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Swager, T.M. Fluorescent Chemosensors Based on Energy Migration in Conjugated Polymers: The Molecular Wire Approach to Increased Sensitivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 12593–12602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swager, T.M. The Molecular Wire Approach to Sensory Signal Amplification. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998, 31, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavase, T.R.; Lin, H.; Shaikh, Q.; Hussain, S.; Li, Z.; Ahmed, I.; Lv, L.; Sun, L.; Shah, S.B.H.; Kalhoro, M.T. Recent Advances of Conjugated Polymer (CP) Nanocomposite-Based Chemical Sensors and Their Applications in Food Spoilage Detection: A Comprehensive Review. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 273, 1113–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.W.; Joly, G.D.; Swager, T.M. Chemical Sensors Based on Amplifying Fluorescent Conjugated Polymers. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 1339–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Povlich, L.K.; Kim, J. Recent Advances in Fluorescent and Colorimetric Conjugated Polymer-Based Biosensors. Analyst 2010, 135, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Wan, J.; Lei, H.; Chen, Y.; Feng, J.; Liu, K. Energy Band Gap Modulation and Photoinduced Electron Transfer Fluorescence Sensing Properties of D–A Conjugated Polymers Containing Benzotriazole. J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 62, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhan, H.; Chen, J.; Sun, L.; Fan, L. Synthesis of a Conjugated Polymer for Sensing Ferric/Ferrous Cations Based on Dual Responses. J. Polym. Sci. 2020, 58, 2088–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Hao, Y.; Tian, X.; He, Y.; Li, J.; Shahid, M.; Iyer, P.K.; Gao, R. Aggregation and Binding-Directed FRET Modulation of Conjugated Polymer Materials for Selective and Point-of-Care Monitoring of Serum Albumins. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 10685–10694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Pan, G.; He, Y. Conjugated Microporous Organic Polymer as Fluorescent Chemosensor for Detection of Fe3+ and Fe2+ Ions with High Selectivity and Sensitivity. Talanta 2022, 236, 122872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Shang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Hu, A. An Electronic Tongue Based on Conjugated Polymers for the Discrimination and Quantitative Detection of Tetracyclines. Analyst 2023, 148, 5152–5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Tan, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y.Z.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, Y.; Tan, C. Fluorescence Array-Based Sensing of Metal Ions Using Conjugated Polyelectrolytes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 6882–6888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wang, B.; Bender, M.; Seehafer, K.; Bunz, U.H.F. Water-Soluble Poly(p-Aryleneethynylene)s: A Sensor Array Discriminates Aromatic Carboxylic Acids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 20415–20421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Pinto, M.R.; Hardison, L.M.; Mwaura, J.; Müller, J.; Jiang, H.; Witker, D.; Kleiman, V.D.; Reynolds, J.R.; Schanze, K.S. Variable Band Gap Poly(Arylene Ethynylene) Conjugated Polyelectrolytes. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 6355–6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodka, M.D.; Schnee, V.P.; Polcha, M.P. Fluorescent Polymer Sensor Array for Detection and Discrimination of Explosives in Water. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 9917–9924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wu, W.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, T.; Fan, L.-J. Construction of Response Patterns for Metal Cations by Using a Fluorescent Conjugated Polymer Sensor Array from Parallel Combinatorial Synthesis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 5041–5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropp, J.; Ihde, M.H.; Crater, E.R.; Bell, N.C.; Bhatta, R.; Johnson, I.C.; Bonizzoni, M.; Azoulay, J.D. A Sensor Array for the Nanomolar Detection of Azo Dyes in Water. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Du, N.; Huang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Tan, Y.; Tan, C. Discrimination of Powdered Infant Formula According to Species, Country of Origin, and Brand Using a Fluorescent Sensor Array. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 1392–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T.L.; Tran, I.; Ingallinera, T.G.; Maynor, M.S.; Lavigne, J.J. Multi-Layered Analyses Using Directed Partitioning to Identify and Discriminate between Biogenic Amines. Analyst 2007, 132, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Bender, M.; Seehafer, K.; Bunz, U.H.F. Identification of White Wines by Using Two Oppositely Charged Poly(p-phenyleneethynylene)s Individually and in Complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 7689–7692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Seehafer, K.; Bunz, U.H.F. Discrimination of Flavonoids by a Hypothesis Free Sensor Array. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2019, 1, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Han, J.; Ma, C.; Bender, M.; Seehafer, K.; Herrmann, A.; Bunz, U.H.F. A Simple Optoelectronic Tongue Discriminates Amino Acids. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 12471–12474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Y.X.; Tan, E.X.; Leong, S.X.; Lin Koh, C.S.; Thanh Nguyen, L.B.; Ting Chen, J.R.; Xia, K.; Ling, X.Y. Where Nanosensors Meet Machine Learning: Prospects and Challenges in Detecting Disease X. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 13279–13293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greener, J.G.; Kandathil, S.M.; Moffat, L.; Jones, D.T. A Guide to Machine Learning for Biologists. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Liu, K.; Zhou, Y.; Debliquy, M.; Bittencourt, C.; Zhang, C. A Comprehensive Overview of the Principles and Advances in Electronic Noses for the Detection of Alcoholic Beverages. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 156, 104862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.X.; Wai, H.-T.; Li, L.; Scaglione, A. A Review of Distributed Algorithms for Principal Component Analysis. Proc. IEEE 2018, 106, 1321–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.-L.; Gan, H.-Q.; Qin, Z.-Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, M.; Chen, D.; Sessler, J.L.; Tian, H.; He, X.-P. Phenotyping of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Using a Ratiometric Sensor Array. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 8917–8926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, X.; Xi, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z. Comprehensive Survey on Hierarchical Clustering Algorithms and the Recent Developments. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 8219–8264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Tan, C. Cross-Reactive Fluorescent Sensor Array for Discrimination of Amyloid Beta Aggregates. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 5469–5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Raitoharju, J.; Iosifidis, A.; Gabbouj, M. Saliency-Based Multilabel Linear Discriminant Analysis. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 10200–10213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh, A. What Are Artificial Neural Networks? Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.R.; Wang, X.-J. Artificial Neural Networks for Neuroscientists: A Primer. Neuron 2020, 107, 1048–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhen, L.; Bi, Z.; Jin, P.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, H. The Facile Discriminative Detection of Four Synthetic Antioxidants in Edible Oil by a Multi-Signal Sensor Array Based on the Bop-Cu Nanozyme Combining Machine Learning. Food Res. Int. 2025, 218, 116917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S.; Hafeez, A.; Shah, H.; Mutiullah, I.; Ali, A.; Khan, K.; Figueroa-González, G.; Reyes-Hernández, O.D.; Quintas-Granados, L.I.; Peña-Corona, S.I.; et al. Emerging Biomarkers for Early Cancer Detection and Diagnosis: Challenges, Innovations, and Clinical Perspectives. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.K.; Koshy, P.; Yang, J.; Sorrell, C.C. Preclinical Cancer Theranostics—From Nanomaterials to Clinic: The Missing Link. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2104199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, D.; Bhatia, S.; Brindle, K.M.; Coussens, L.M.; Dive, C.; Emberton, M.; Esener, S.; Fitzgerald, R.C.; Gambhir, S.S.; Kuhn, P.; et al. Early Detection of Cancer. Science 2022, 375, eaay9040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wu, F.-G. Fluorescent Carbon Dots for Discriminating Cell Types: A Review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 3945–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Elci, S.G.; Mout, R.; Singla, A.K.; Yazdani, M.; Bender, M.; Bajaj, A.; Saha, K.; Bunz, U.H.F.; Jirik, F.R.; et al. Ratiometric Array of Conjugated Polymers–Fluorescent Protein Provides a Robust Mammalian Cell Sensor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 4522–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Tao, L.; Qiu, J.; Xu, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, X.; Guan, X.; Cen, X.; Zhao, Y. Tumor Biomarkers for Diagnosis, Prognosis and Targeted Therapy. Sig. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Lin, X.; Chen, F.; Qin, X.; Yan, Y.; Ren, L.; Yu, H.; Chang, L.; Wang, Y. Current Research Status of Tumor Cell Biomarker Detection. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2023, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.D.B.; Singla, A.K.; Geng, Y.; Han, J.; Seehafer, K.; Prakash, G.; Moyano, D.F.; Downey, C.M.; Monument, M.J.; Itani, D.; et al. Simple and Robust Polymer-Based Sensor for Rapid Cancer Detection Using Serum. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 11458–11461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Du, N.; Huang, Y.; Shen, W.; Tan, Y.; Chen, Y.Z.; Dou, W.-T.; He, X.-P.; Yang, Z.; Xu, N.; et al. Fluorescence Analysis of Circulating Exosomes for Breast Cancer Diagnosis Using a Sensor Array and Deep Learning. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 1524–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, C.; Barrias, S.; Chaves, R.; Adega, F.; Martins-Lopes, P.; Fernandes, J.R. Biosensors as Diagnostic Tools in Clinical Applications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2022, 1877, 188726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbelkar, A.A.; Furst, A.L. Electrochemical Diagnostics for Bacterial Infectious Diseases. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 1567–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, H.; Lu, H.; Fu, X.; Zhang, E.; Lv, F.; Liu, L.; Wang, S. Supramolecular Strategy Based on Conjugated Polymers for Discrimination of Virus and Pathogens. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 2117–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ni, W.; Hu, Q.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, S.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A Dual Fluorescence Turn-On Sensor Array Formed by Poly(Para-aryleneethynylene) and Aggregation-Induced Emission Fluorophores for Sensitive Multiplexed Bacterial Recognition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202318483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Li, M.; Li, R.; Cheng, J.; Lin, H.; Qi, R.; Yuan, H.; Bai, H. Statistical Learning-Assisted Dual-Signal Sensing Arrays Based on Conjugated Molecules for Pathogen Detection and Identification. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 45489–45500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D.M.; Cookson, M.R.; Van Den Bosch, L.; Zetterberg, H.; Holtzman, D.M.; Dewachter, I. Hallmarks of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cell 2023, 186, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.; Sun, Z.; Gou, F.; Wang, J.; Fan, Q.; Zhao, D.; Yang, L. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Impairment: Key Drivers in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 104, 102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duy Mac, K.; Su, J. Optical Biosensors for Diagnosing Neurodegenerative Diseases. npj Biosensing 2025, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-Y.; Zhou, C.-M.; Jin, R.-L.; Song, J.-H.; Yang, K.-C.; Li, S.-L.; Tan, B.-H.; Li, Y.-C. The Detection Methods Currently Available for Protein Aggregation in Neurological Diseases. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2024, 138, 102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, A.; Babu, S.S.; Ghosh, S.; Velyutham, R.; Kapusetti, G. Advances and Future Trends in the Detection of Beta-Amyloid: A Comprehensive Review. Med. Eng. Phys. 2025, 135, 104269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, M.; Sun, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, F.; Han, J. Machine Learning-Assisted Pattern Recognition of Amyloid Beta Aggregates with Fluorescent Conjugated Polymers and Graphite Oxide Electrostatic Complexes. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 2757–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Guo, Y.; Lin, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hou, J.; Wei, X. Utilization of Aggregation-induced Emission Materials in Urinary System Diseases. Aggregate 2024, 5, e580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, K.; Patel, D.M. Urinalysis. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 107, 659–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Guo, B.; Jiang, H.; Tan, C.; Jiang, Y. Fluorescence Sensor Array for Discrimination of Urine Proteins and Differentiation Diagnosis of Urinary System Diseases. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 5639–5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinic Disease | Class of Sensor Molecule | Analytes | Analysis Method | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | PPE/GFP | cells | LDA, HCA | [76] |

| PPE, PFS | serum protein | LDA | [79] | |

| PPE | cells, exosomes | LDA, Deep learning | [80] | |

| Infectious Diseases | PT/CB [7] | virus, microbes | LDA | [83] |

| PPE/AIE | bacteria | LDA, Deep learning | [84] | |

| CCP/Ag | bacteria, fungi | LDA, PCA | [85] | |

| Neurodegenerative diseases | PPE, ThT, NR | Aβ | LDA, HCA | [67] |

| PPE/GO | Aβ | LDA, Deep learning | [91] | |

| Urinary System Diseases | PPE, ANS, NR | urine proteins | LDA, HCA | [94] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ye, Q.; Fan, S.; Lao, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, P. Research Advances in Conjugated Polymer-Based Optical Sensor Arrays for Early Diagnosis of Clinical Diseases. Polymers 2026, 18, 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030310

Ye Q, Fan S, Lao J, Xu J, Liu X, Wu P. Research Advances in Conjugated Polymer-Based Optical Sensor Arrays for Early Diagnosis of Clinical Diseases. Polymers. 2026; 18(3):310. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030310

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Qiuting, Shijie Fan, Jieling Lao, Jiawei Xu, Xiyu Liu, and Pan Wu. 2026. "Research Advances in Conjugated Polymer-Based Optical Sensor Arrays for Early Diagnosis of Clinical Diseases" Polymers 18, no. 3: 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030310

APA StyleYe, Q., Fan, S., Lao, J., Xu, J., Liu, X., & Wu, P. (2026). Research Advances in Conjugated Polymer-Based Optical Sensor Arrays for Early Diagnosis of Clinical Diseases. Polymers, 18(3), 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030310