The Effect of CO2 Laser Treatment on the Composition of Cotton/Polyester/Metal Fabric

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

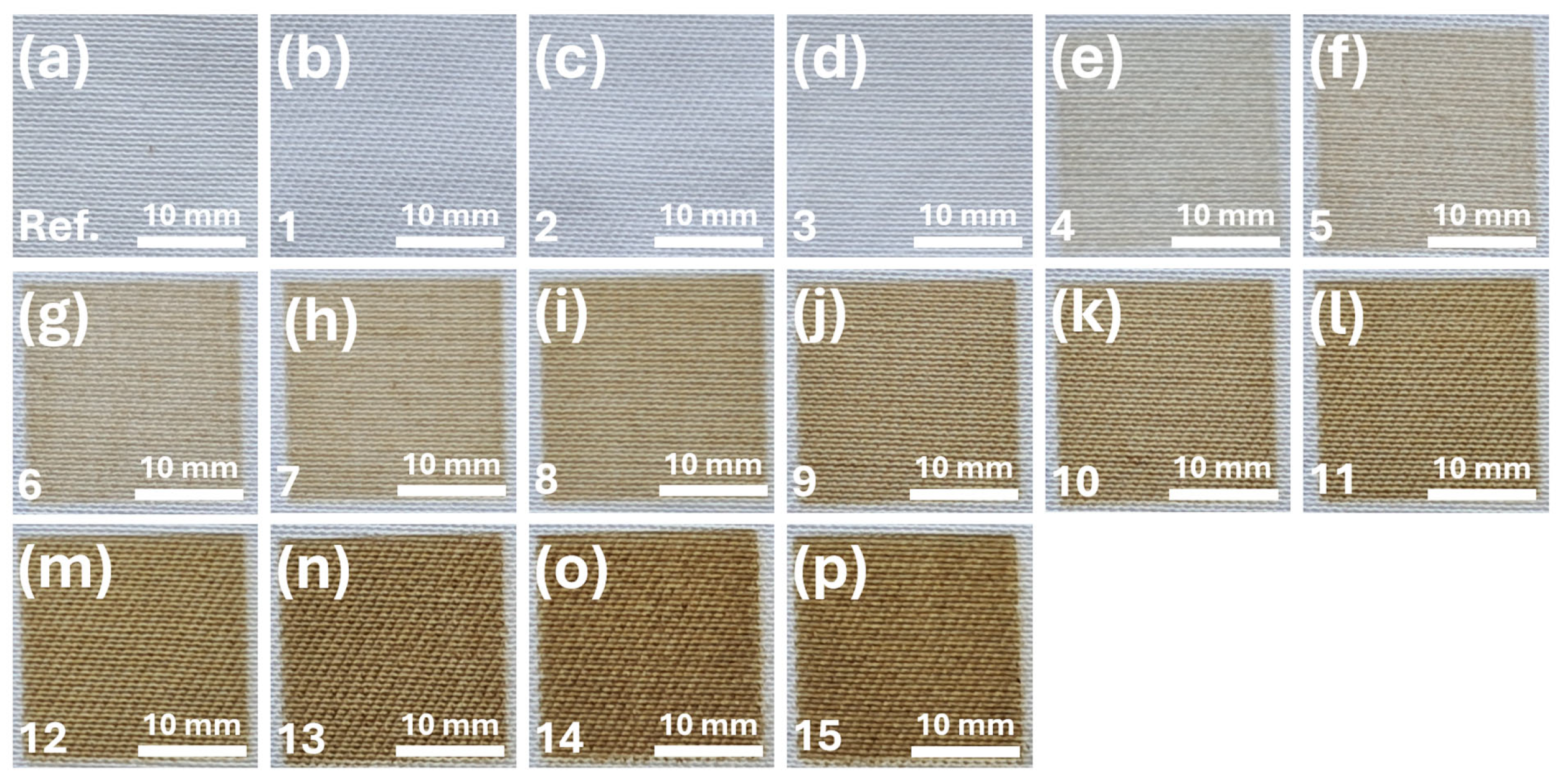

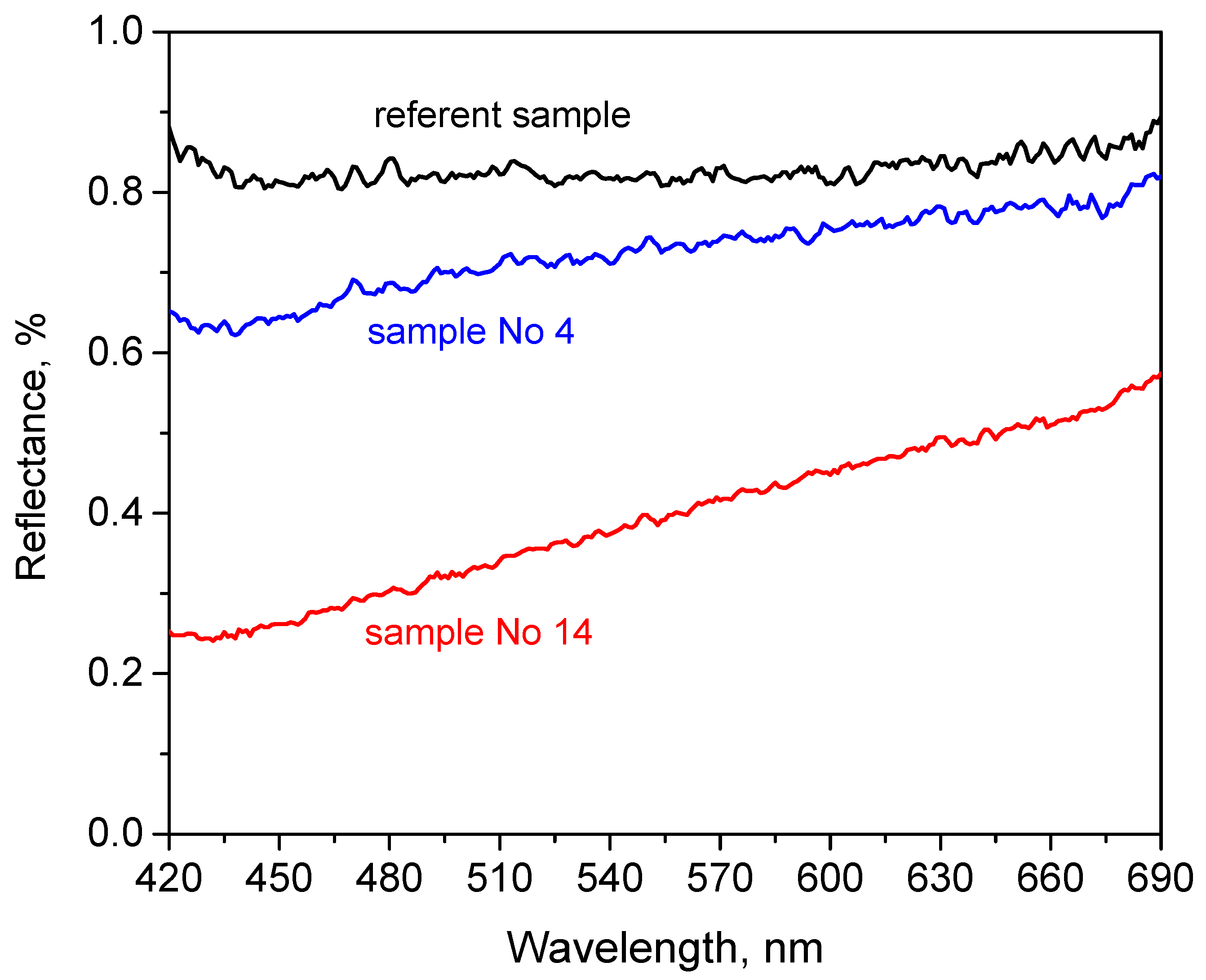

3.1. Laser Treatment Effect on Color

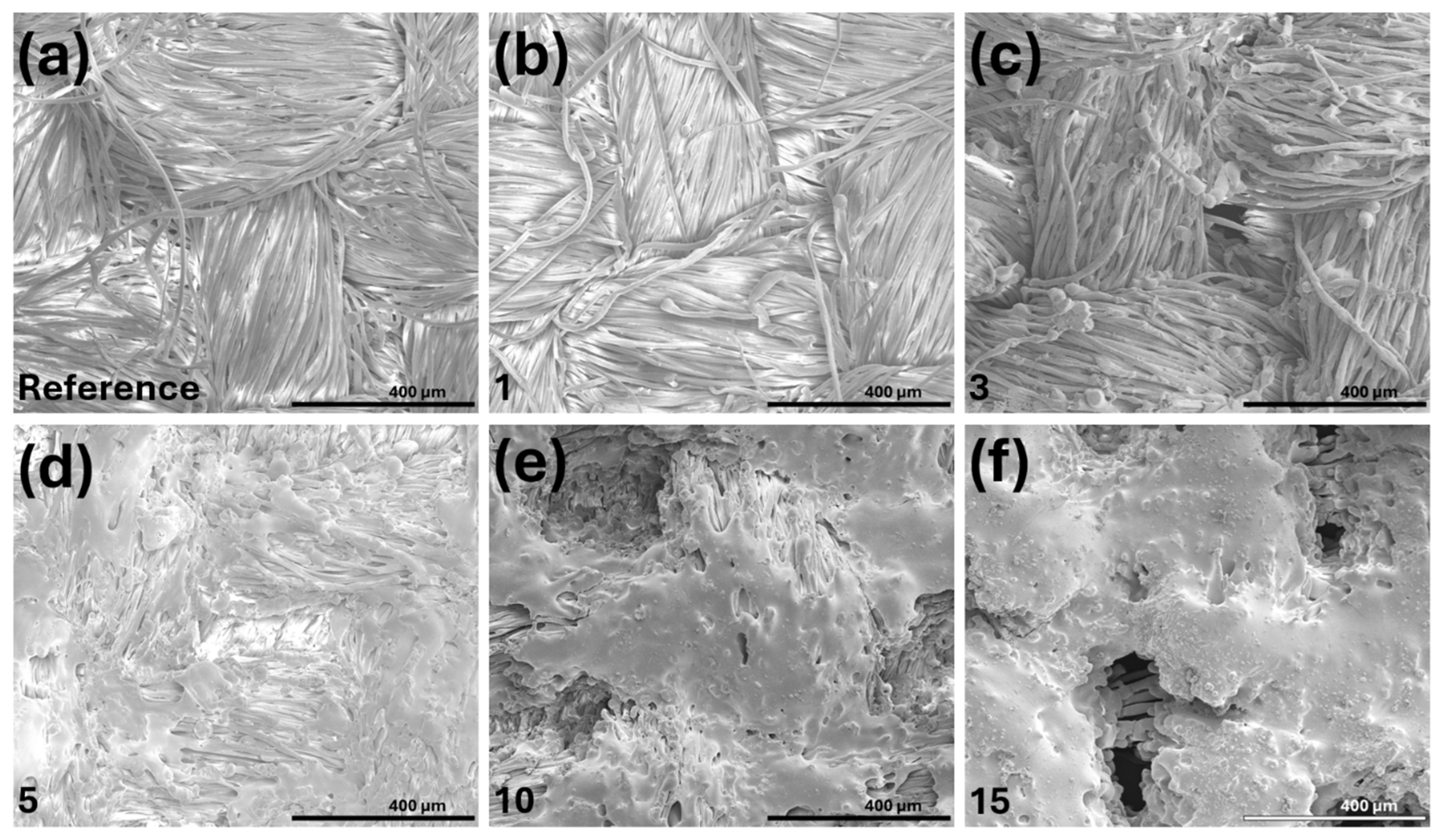

3.2. Laser Treatment Effect on Surface Morphology

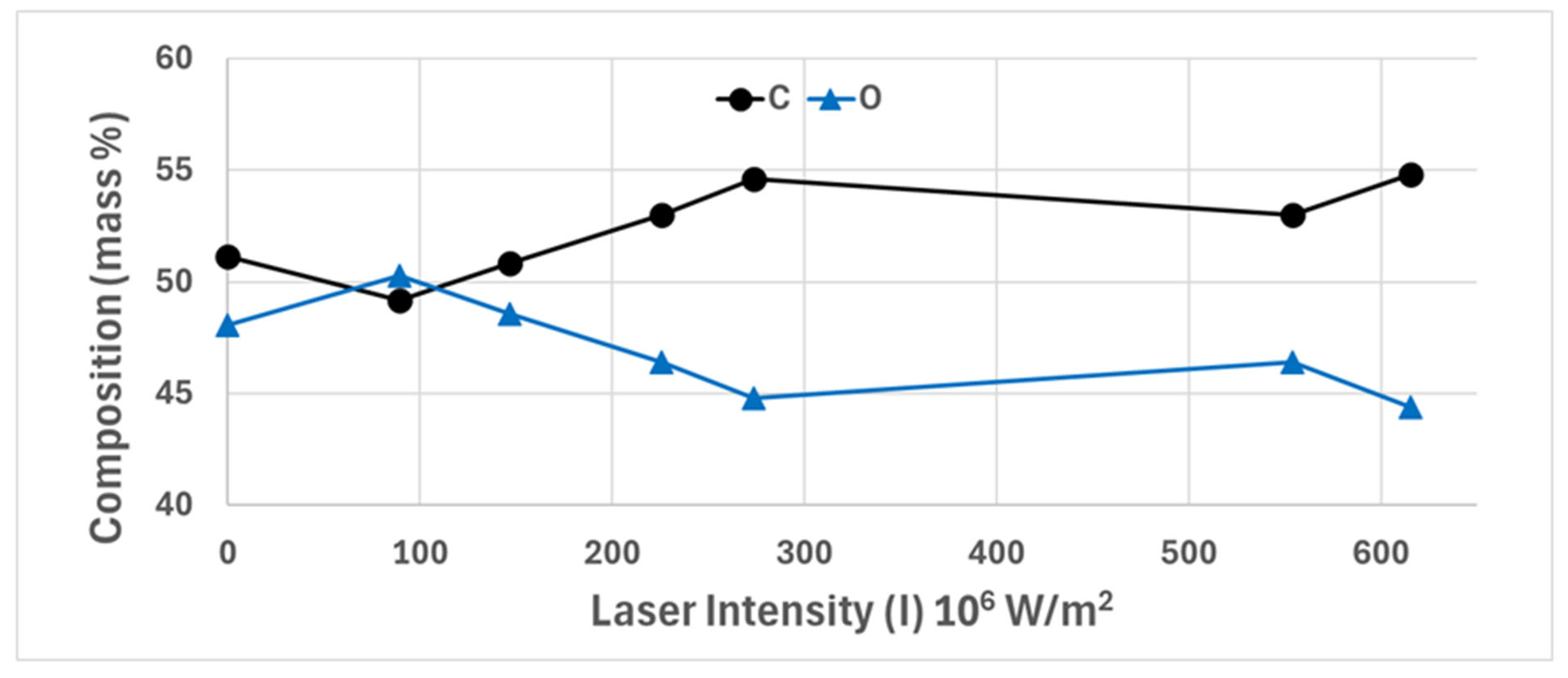

3.3. Effect of Laser Treatment on Elemental Composition

- –

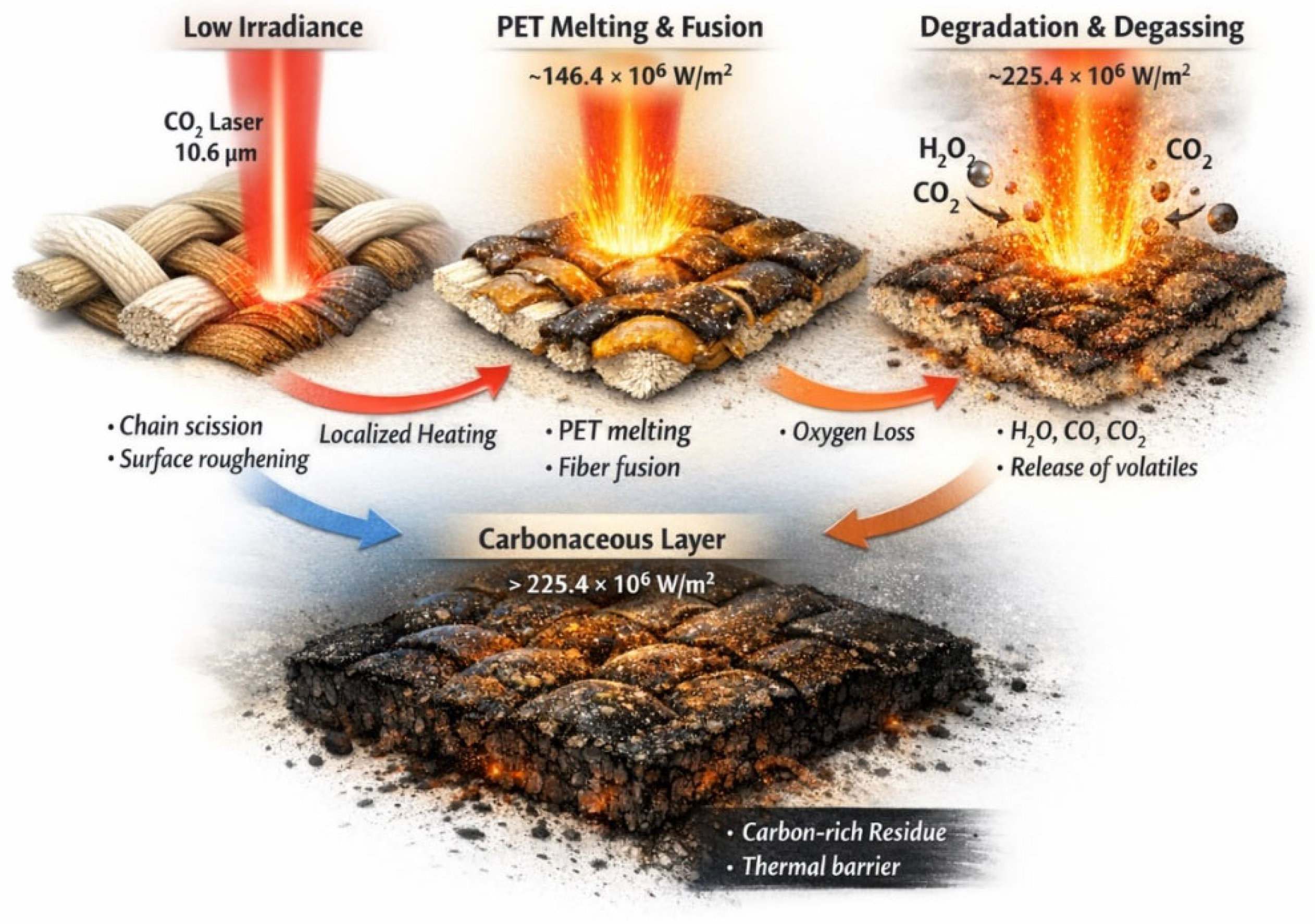

- Initial Phase (Induction): At lower intensities, the laser energy causes the rupture of polymer chains and the initiation of surface roughening.

- –

- Melting and Fusion (Intensity ~146.4 × 106 W/m2): The polyester (PET) component, having a lower melting point, begins to melt and coat the cotton fibers, creating a carbon-rich amorphous layer.

- –

- Degradation and Degassing: High thermal energy triggers the decomposition of oxygen-containing functional groups, releasing volatile species such as H2O, CO, and CO2.

- –

- Formation of Carbonaceous Layer (Intensity up to 225.4 × 106 W/m2): A stable carbon-rich residue (char) forms on the surface. This layer eventually acts as a thermal insulator, slowing down further deep chemical degradation as laser intensity increases.

- –

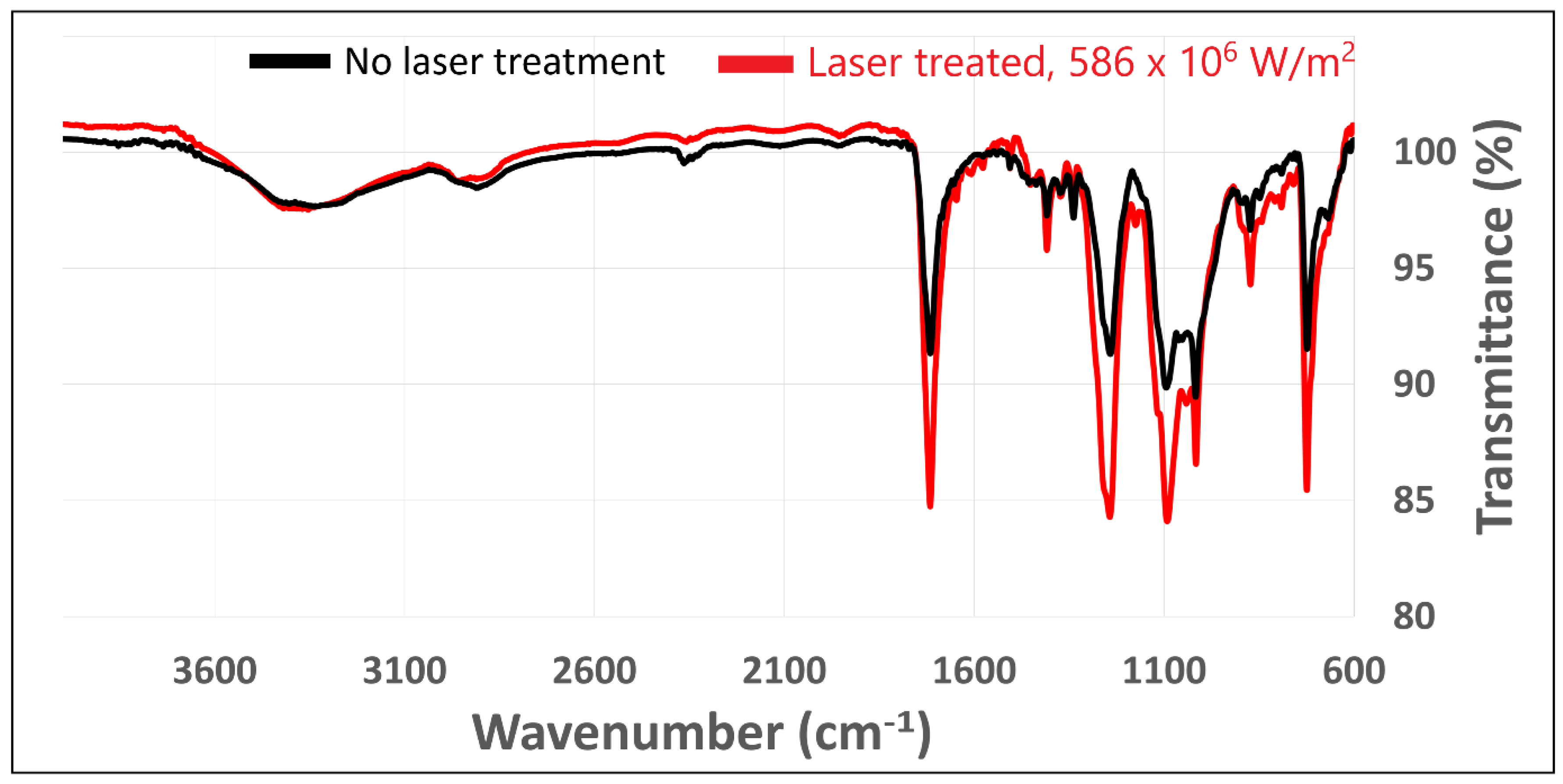

- Hydroxyl Groups (-OH): Abundant in the cellulose structure of cotton. These are highly sensitive to thermal energy and undergo dehydration and decarboxylation.

- –

- Ester and Carbonyl Groups (C=O, C-O-C): Present in the polyester (PET) chains. The laser causes “chain scission” and the cleavage of ester bonds, leading to a significant loss of oxygen atoms.

- –

- Methylene Groups (CH2): While less volatile, their relative exposure and orientation change as the polymer matrix rearranges during melting and carbonization.

3.4. Laser Treatment Effect on Chemical Composition

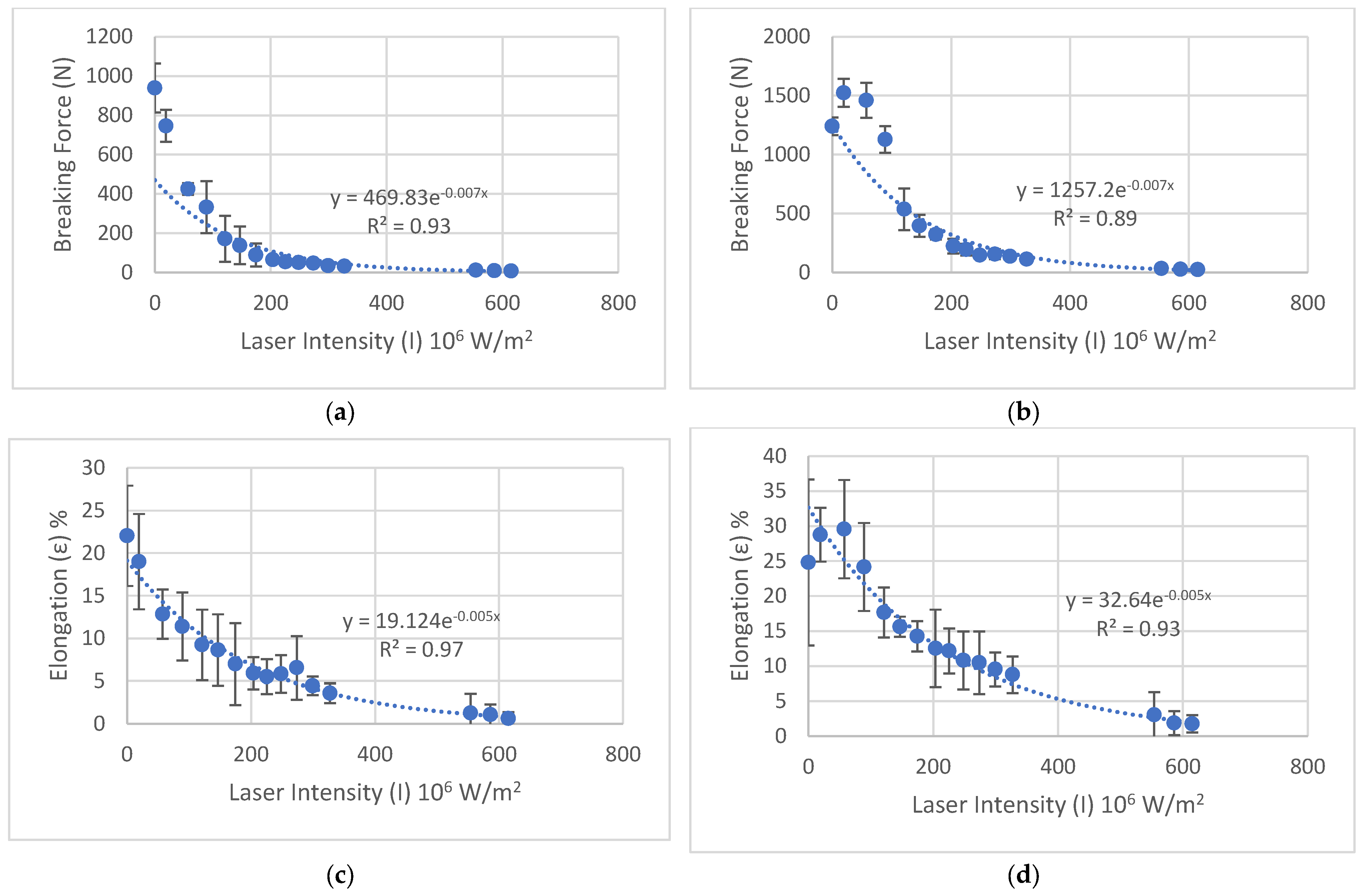

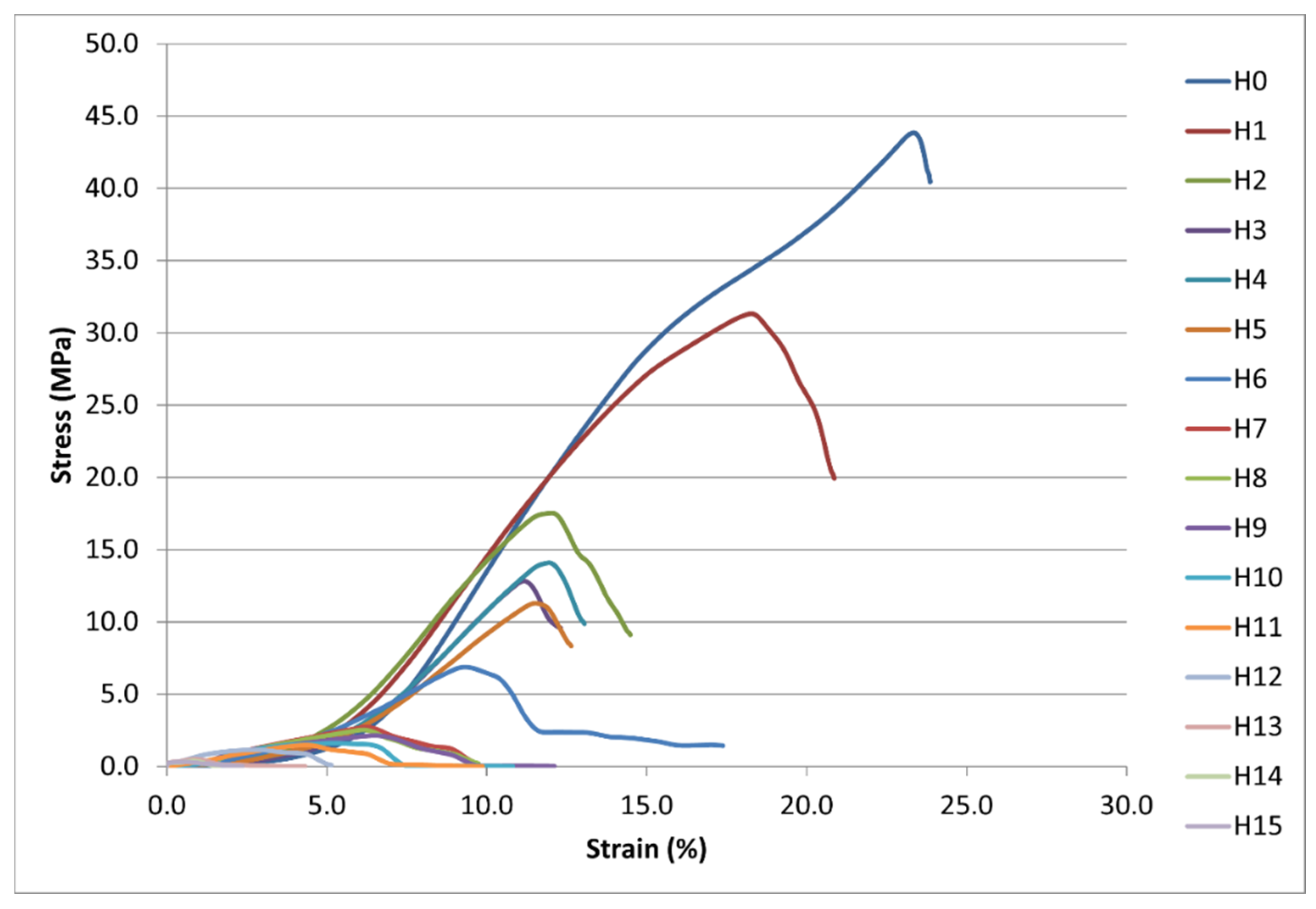

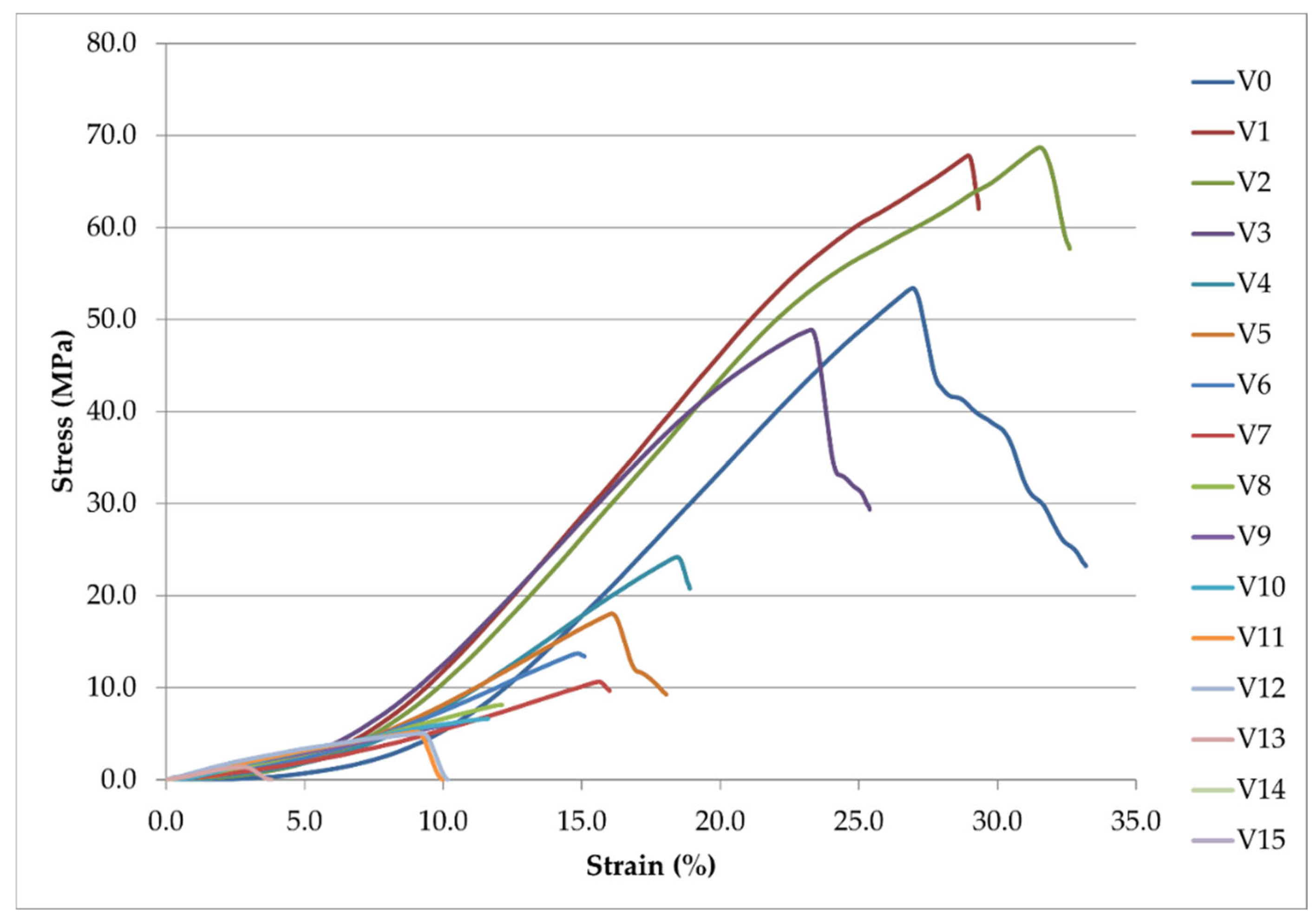

3.5. Laser Treatment Effect on Mechanical Properties

3.6. Surface Wettability and Contact Angle Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Shen, X.; Xu, W. Effect of hydrogen peroxide treatment on the properties of wool fabric. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 10012–10016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, M.; Walzak, M.J.; Hill, J.M.; Lin, A.; Karbashewski, E.; Lyons, C.S. A comparison of gas-phase methods of modifying polymer surfaces. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 1995, 9, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchaniya, J.V.; Lasenko, I.; Kanukuntla, S.P.; Mannodi, A.; Viluma-gudmona, A.; Gobins, V. Preparation and Characterization of Non-Crimping Laminated Textile Composites Reinforced with Electrospun Nanofibers. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchaniya, J.V.; Lasenko, I.; Vijayan, V.; Smogor, H.; Gobins, V.; Kobeissi, A.; Goljandin, D. A Novel Method to Enhance the Mechanical Properties of Polyacrylonitrile Nanofiber Mats: An Experimental and Numerical Investigation. Polymers 2024, 16, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchaniya, J.V.; Lasenko, I.; Kanukuntala, S.P.; Smogor, H.; Viluma-Gudmona, A.; Krasnikovs, A.; Tipans, I.; Gobins, V. Mechanical and Thermal Characterization of Annealed Oriented PAN Nanofibers. Polymers 2023, 15, 3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, C.-W.; Lo, C.K.Y.; Man, W.S. Environmentally friendly aspects in coloration. Color. Technol. 2016, 132, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchaniya, J.V.; Lasenko, I.; Gobins, V.; Kobeissi, A. A Finite Element Method for Determining the Mechanical Properties of Electrospun Nanofibrous Mats. Polymers 2024, 16, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasenko, I.; Sanchaniya, J.V.; Kanukuntla, S.P.; Viluma-Gudmona, A.; Vasilevska, S.; Vejanand, S.R. Assessment of Physical and Mechanical Parameters of Spun-Bond Nonwoven Fabric. Polymers 2024, 16, 2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbinienė, A.; Fataraitė-Urbonienė, E.; Jucienė, M.; Dobilaitė, V.; Valeika, V. Effect of CO2 laser treatment on the leather surface morphology and wettability. J. Ind. Text. 2021, 51, 2483S–2498S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffar, M.A.; Ahammed, B.; Hoque, T.; Maksura, S.; Islam, M.R. Advanced Surface Modification Techniques for Sustainable Coloration of Textile Materials. In Advancements in Textile Coloration: Techniques, Technologies, and Trends; Shahid, M., Maiti, S., Khan, S.A., Adivarekar, R.V., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 287–315. ISBN 978-981-96-5091-0. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, P.; Shukla, A. Advancements in Plasma Technology for Textile Surface Modification. In Advancements in Textile Finishing: Techniques, Technologies, and Trends; Shahid, M., Biranje, S., Yusuf, M., Adivarekar, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 293–303. ISBN 978-981-96-6385-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ekunde, R.A.; Sutar, R.S.; Ingole, S.S.; Jundle, A.R.; Gaikwad, P.P.; Saji, V.S.; Liu, S.; Bhosale, A.K.; Latthe, S.S. Fluorine-free and breathable self-cleaning superhydrophobic CS/PDMS/PLA coatings on wearable cotton fabric with light-induced self-sterilization. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 208, 109514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, C.W. Impact on textile properties of polyester with laser. Opt. Laser Technol. 2008, 40, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, Y.L.; Chan, C.K.; Kan, C.W. Effect of CO2 laser treatment on cotton surface. Cellulose 2011, 18, 1635–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, Y.L.F.; Chan, A.; Kan, C.-W. Effect of CO2 laser irradiation on the properties of cotton fabric. Text. Res. J. 2011, 82, 1220–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, O.N.; Chan, C.K.; Kan, C.W.; Yuen, C.W.M.; Song, L.J. Artificial neural network approach for predicting colour properties of laser-treated denim fabrics. Fibers Polym. 2014, 15, 1330–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, C. CO2 laser treatment as a clean process for treating denim fabric. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, C.W. Colour fading effect of indigo-dyed cotton denim fabric by CO2 laser. Fibers Polym. 2014, 15, 426–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukle, S.; Lazov, L.; Lohmus, R.; Briedis, U.; Adijans, I.; Bake, I.; Dunchev, V.; Teirumnieka, E. The Impact of CO2 Laser Treatment on Kevlar® KM2+ Fibres Fabric Surface Morphology and Yarn Pull-Out Resistance. Polymers 2025, 17, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, E.; Pogreb, R.; Sheshnev, A.; Shulzinger, E.; Bormashenko, Y.; Katzir, A. IR laser radiation induced changes in the IR absorption spectra of thermoplastic and thermosetting polymers. J. Opt. A Pure Appl. Opt. 2001, 3, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, O.-N.; Chan, C.-K.; Kan, C.-W.; Yuen, C.-W. Marcus Microscopic study of the surface morphology of CO2 laser-treated cotton and cotton/polyester blended fabric. Text. Res. J. 2016, 87, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, O.; Kan, C. Effect of CO2 Laser Treatment on the Fabric Hand of Cotton and Cotton/Polyester Blended Fabric. Polymers 2017, 9, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, O.N.; Chan, C.K.; Kan, C.W.; Yuen, C.W.M. An analysis of some physical and chemical properties of CO2 laser-treated cotton-based fabrics. Cellulose 2017, 24, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, O.; Kan, C. A Study of CO2 Laser Treatment on Colour Properties of Cotton-Based Fabrics. Coatings 2017, 7, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jucienė, M.; Urbelis, V.; Juchnevičienė, Ž.; Čepukonė, L. The effect of laser technological parameters on the color and structure of denim fabric. Text. Res. J. 2013, 84, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weclawski, B.T.; Horrocks, A.R.; Ebdon, J.R.; Mosurkal, R.; Kandola, B.K. Combined atmospheric pressure plasma and UV surface functionalisation and diagnostics of nylon 6.6 fabrics. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 562, 150090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, D.; Lott, P.; Stollenwerk, J.; Thomas, H.; Möller, M.; Kuehne, A.J.C. Laser Carbonization of PAN-Nanofiber Mats with Enhanced Surface Area and Porosity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 28412–28417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayesh, M.; Horrocks, A.R.; Kandola, B.K. The Impact of Atmospheric Plasma/UV Laser Treatment on the Chemical and Physical Properties of Cotton and Polyester Fabrics. Fibers 2022, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, F.; Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Yu, L. Thermal degradation and combustion properties of most popular synthetic biodegradable polymers. Waste Manag. Res. 2022, 41, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Wang, W.; Wang, R. Thermal Degradation and Carbonization Mechanism of Fe-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks onto Flame-Retardant Polyethylene Terephthalate. Polymers 2023, 15, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, G.; Pei, G.; Guo, F.; Ren, X. Experimental study on nanosecond laser thermal decomposition of CFRP and recycling of carbon fibers. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 175, 110741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayu, A.; Nandiyanto, D.; Ragadhita, R.; Fiandini, M. Interpretation of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectra (FTIR): A Practical Approach in the Polymer/Plastic Thermal Decomposition. Indones. J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 8, 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Irwan, I.; Mohamad, J.N.; Galih, V.; Putra, V. FT-IR Spectral model of polyester-cotton fabrics with corona plasma treatment using artificial neural networks (ANNs). Indones. J. Appl. Phys. 2023, 13, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machnowski, W.; Wąs-Gubała, J. Evaluation of Selected Thermal Changes in Textile Materials Arising in the Wake of the Impact of Heat Radiation. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, M.L.; Sousa, C. Discrimination and Quantification of Cotton and Polyester Textile Samples Using Near-Infrared and Mid-Infrared Spectroscopies. Molecules 2024, 29, 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delacroix, S.; Wang, H.; Heil, T.; Strauss, V. Laser-Induced Carbonization of Natural Organic Precursors for Flexible Electronics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2020, 6, 2000463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili Gashtroudkhani, A.; NazarpourFard, H.; Ghobadian, A.; Alihoseini, M. Non-thermal, atmosphere pressure and roll-to-roll plasma treatment for improving the surface characteristics and antistatic solution absorption in polyester fabrics. J. Text. Inst. 2024, 115, 2693–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Number | Laser Intensity (I) 106 W/m2 | Sample Number | Laser Intensity (I) 106 W/m2 | Sample Number | Laser Intensity (I) 106 W/m2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19.1 | 6 | 174.4 | 11 | 299.2 |

| 2 | 57.3 | 7 | 203.7 | 12 | 327.2 |

| 3 | 89.1 | 8 | 225.4 | 13 | 554.0 |

| 4 | 121.0 | 9 | 248.3 | 14 | 586.0 |

| 5 | 146.4 | 10 | 273.7 | 15 | 615.0 |

| Name | Breaking Load (F) N ISO 13934-1:2013 | Elongation at Break (%) ISO 13934-1:2013 | Thickness (mm) | E (MPa) | UTS (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H0 | 939 ± 124 | 22.04 ± 6 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 347.76 | 43.85 |

| H1 | 746 ± 81 | 19 ± 6 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 302.44 | 31.33 |

| H2 | 425 ± 29 | 12.84 ± 3 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 266.17 | 17.53 |

| H3 | 332.8 ± 132 | 11.4 ± 4 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 225.24 | 12.81 |

| H4 | 171.58 ± 117 | 9.24 ± 4 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 221.80 | 14.10 |

| H5 | 137.74 ± 96 | 8.64 ± 4 | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 178.23 | 17.65 |

| H6 | 88.98 ± 58 | 7 ± 5 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 121.37 | 6.86 |

| H7 | 65.24 ± 15 | 5.92 ± 2 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 43.42 | 2.71 |

| H8 | 54.2 ± 5 | 5.52 ± 2 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 41.66 | 2.51 |

| H9 | 51.32 ± 4 | 5.84 ± 2 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 25.51 | 2.13 |

| H10 | 47.96 ± 8 | 6.56 ± 4 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 61.56 | 1.6 |

| H11 | 35.33 ± 2 | 4.44 ± 1 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 39.41 | 1.46 |

| H12 | 32.46 ± 3 | 3.6 ± 1 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 66.92 | 1.14 |

| H13 | 11.904 ± 2 | 1.28 ± 2 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | - | 0.49 |

| H14 | 9.074 ± 3 | 1.08 ± 1 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | - | 0.59 |

| H15 | 7.872 ± 2 | 0.64 ± 1 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | - | 0.47 |

| V0 | 1240 ± 75 | 24.8 ± 12 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 317.81 | 53.38 |

| V1 | 1524 ± 118 | 28.76 ± 4 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 352.17 | 67.80 |

| V2 | 1460 ± 149 | 29.56 ± 7 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 343.02 | 68.66 |

| V3 | 1128.6 ± 114 | 24.15 ± 6 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 317.75 | 48.87 |

| V4 | 536.6 ± 176 | 17.64 ± 4 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 210.34 | 24.2 |

| V5 | 396 ± 93 | 15.6 ± 1 | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 164.21 | 28.25 |

| V6 | 322.4 ± 42 | 14.24 ± 2 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 115.63 | 13.73 |

| V7 | 224.2 ± 62 | 12.52 ± 6 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 97.09 | 10.65 |

| V8 | 195 ± 49 | 12.16 ± 3 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 62.90 | 8.12 |

| V9 | 147.6 ± 31 | 10.8 ± 4 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 58.49 | 6.10 |

| V10 | 155.6 ± 41 | 10.48 ± 4 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 60.57 | 6.66 |

| V11 | 137.2 ± 15 | 9.52 ± 2 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 61.39 | 5.23 |

| V12 | 113.34 ± 19 | 8.76 ± 3 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 56.47 | 5.06 |

| V13 | 34.32 ± 12 | 3.04 ± 3 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 67.64 | 1.40 |

| V14 | 27.66 ± 14 | 1.88 ± 2 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 115.41 | 1.78 |

| V15 | 25.42 ± 9 | 1.76 ± 1 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 58.26 | 1.34 |

| Sample Number | Laser Intensity (106 W/m2) | Contact Angle, θ (Degrees) | Surface State |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0 | 105° ± 3° | Hydrophobic |

| 1 | 19.1 | 108° ± 4° | Hydrophobic |

| 4 | 121.0 | 115° ± 3° | Hydrophobic |

| 8 | 225.4 | 128° ± 5° | Highly Hydrophobic |

| 15 | 615.0 | 135° ± 6° | Highly Hydrophobic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Skromulis, A.; Lasenko, I.; Adijāns, I.; Liepiņlauska, I.; Merisalu, M.; Mäeorg, U.; Sokolova, S.; Vasilevska, S.; Kanukuntla, S.P.; Sanchaniya, J.V. The Effect of CO2 Laser Treatment on the Composition of Cotton/Polyester/Metal Fabric. Polymers 2026, 18, 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020215

Skromulis A, Lasenko I, Adijāns I, Liepiņlauska I, Merisalu M, Mäeorg U, Sokolova S, Vasilevska S, Kanukuntla SP, Sanchaniya JV. The Effect of CO2 Laser Treatment on the Composition of Cotton/Polyester/Metal Fabric. Polymers. 2026; 18(2):215. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020215

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkromulis, Andris, Inga Lasenko, Imants Adijāns, Ilze Liepiņlauska, Maido Merisalu, Uno Mäeorg, Svetlana Sokolova, Sandra Vasilevska, Sai Pavan Kanukuntla, and Jaymin Vrajlal Sanchaniya. 2026. "The Effect of CO2 Laser Treatment on the Composition of Cotton/Polyester/Metal Fabric" Polymers 18, no. 2: 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020215

APA StyleSkromulis, A., Lasenko, I., Adijāns, I., Liepiņlauska, I., Merisalu, M., Mäeorg, U., Sokolova, S., Vasilevska, S., Kanukuntla, S. P., & Sanchaniya, J. V. (2026). The Effect of CO2 Laser Treatment on the Composition of Cotton/Polyester/Metal Fabric. Polymers, 18(2), 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020215