Polyacrylonitrile Nanofiber Mats Produced by Solution Blow Spinning: Influence of Process Parameters on Fiber Diameter and Residual Solvent Content

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents Used

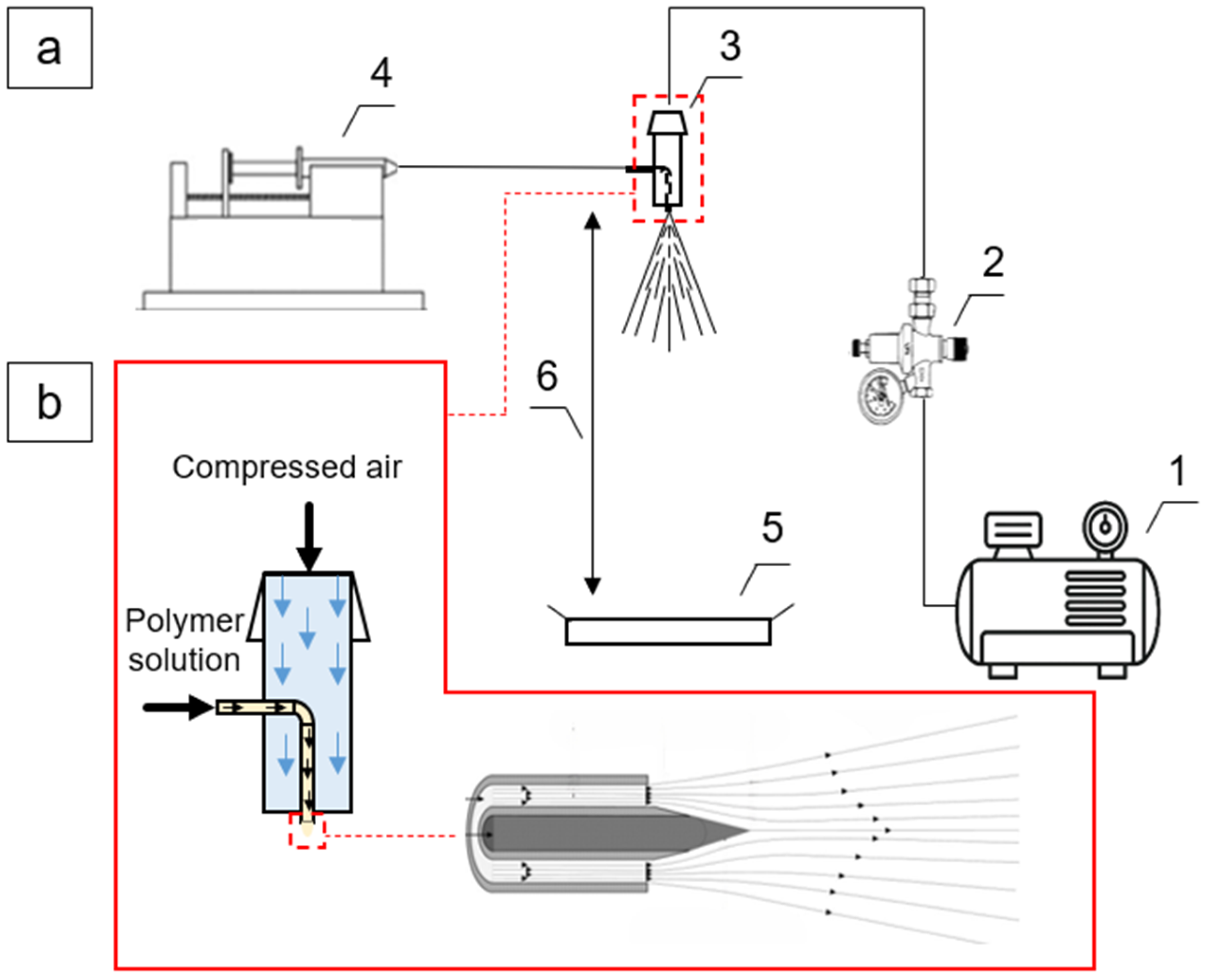

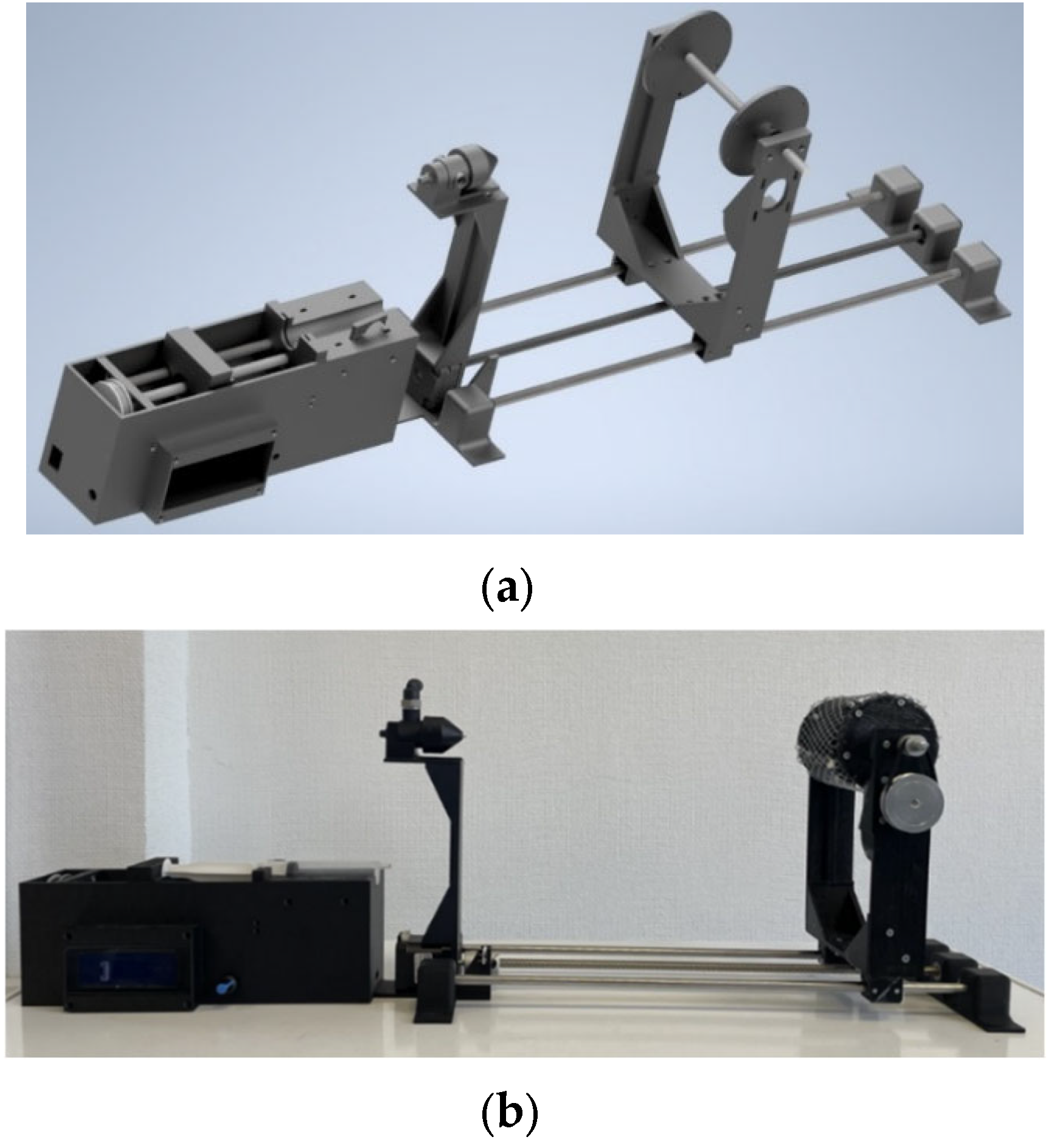

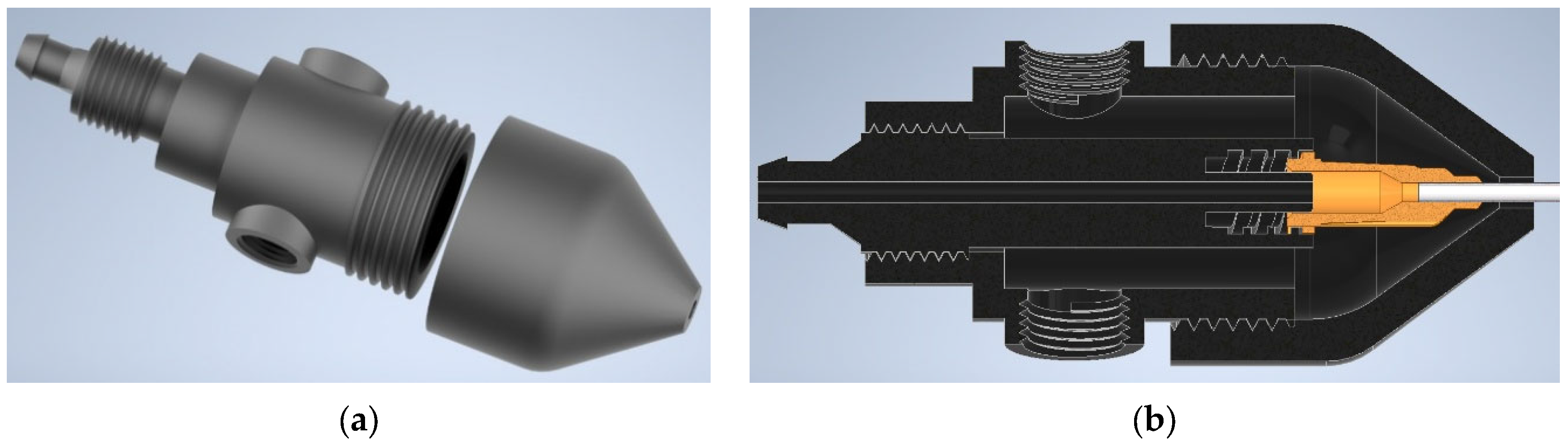

2.2. Development of SBS Installation

2.3. Preparation of Polymer Solution

2.4. Experimental Study of Solution Blow Spinning Process

2.5. Determination of Residual Solvent Content

2.6. SEM Analysis and Determination of Fiber Diameter

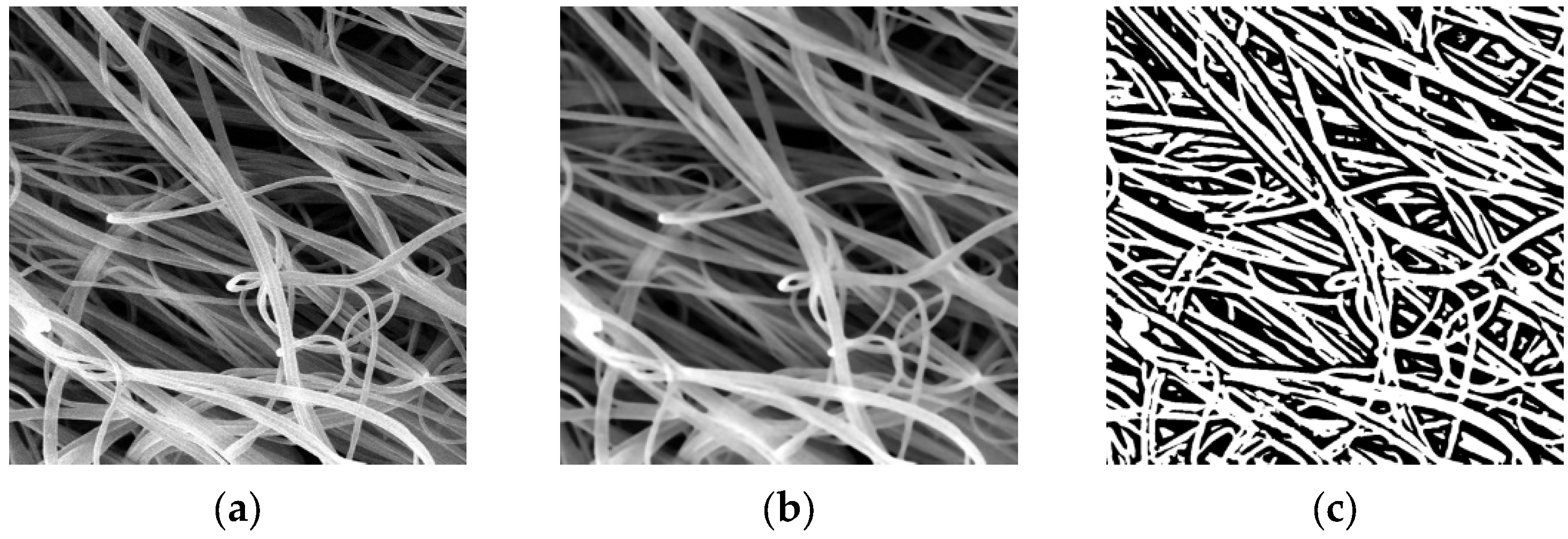

- Noise reduction. To eliminate imaging artifacts in the form of noise, median blurring and Gaussian blurring are applied.

- Fiber segmentation. For visual separation of fibers from the background, automatic binarization is performed using Otsu’s method. This algorithm optimizes the threshold intensity level, thereby minimizing the variance between the background and the objects, which makes it possible to distinguish fibers even when the illumination in the image is non-uniform.

2.7. Regression Analysis Method

- Form the observation matrix X of size n × (p + 1), where n is the number of observations: the first column contains ones (the intercept term), and the remaining columns contain the values of the independent variables;

- Form the vector Y of observed values of the dependent variable;

- Compute the coefficient vector according to Equation (4):

- 4.

- The obtained coefficients are then substituted into the regression equation for prediction and analysis.

- 5.

- The statistical significance of the regression coefficients is assessed using the Student t-test. The tabulated Student’s t value for the present model is 2.09.

- 6.

- The adequacy of the model is evaluated using the Fisher F test. The model is considered adequate if the calculated value of the F criterion is lower than the tabulated value for the selected significance level and degrees of freedom. For this model, the tabulated Fisher criterion at p = 0.05 is 2.6.

3. Results and Discussion

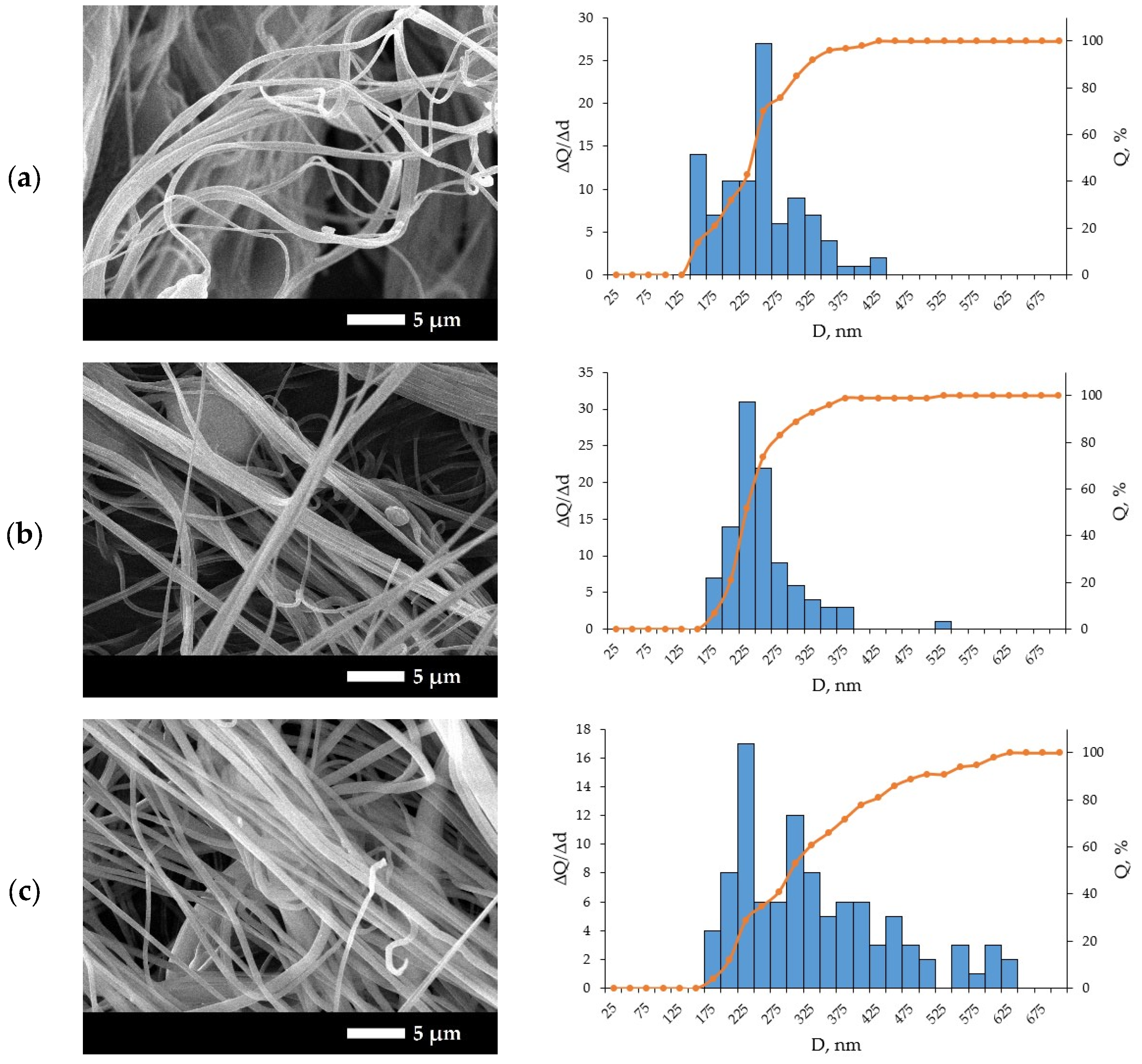

3.1. Nanofibers Structure

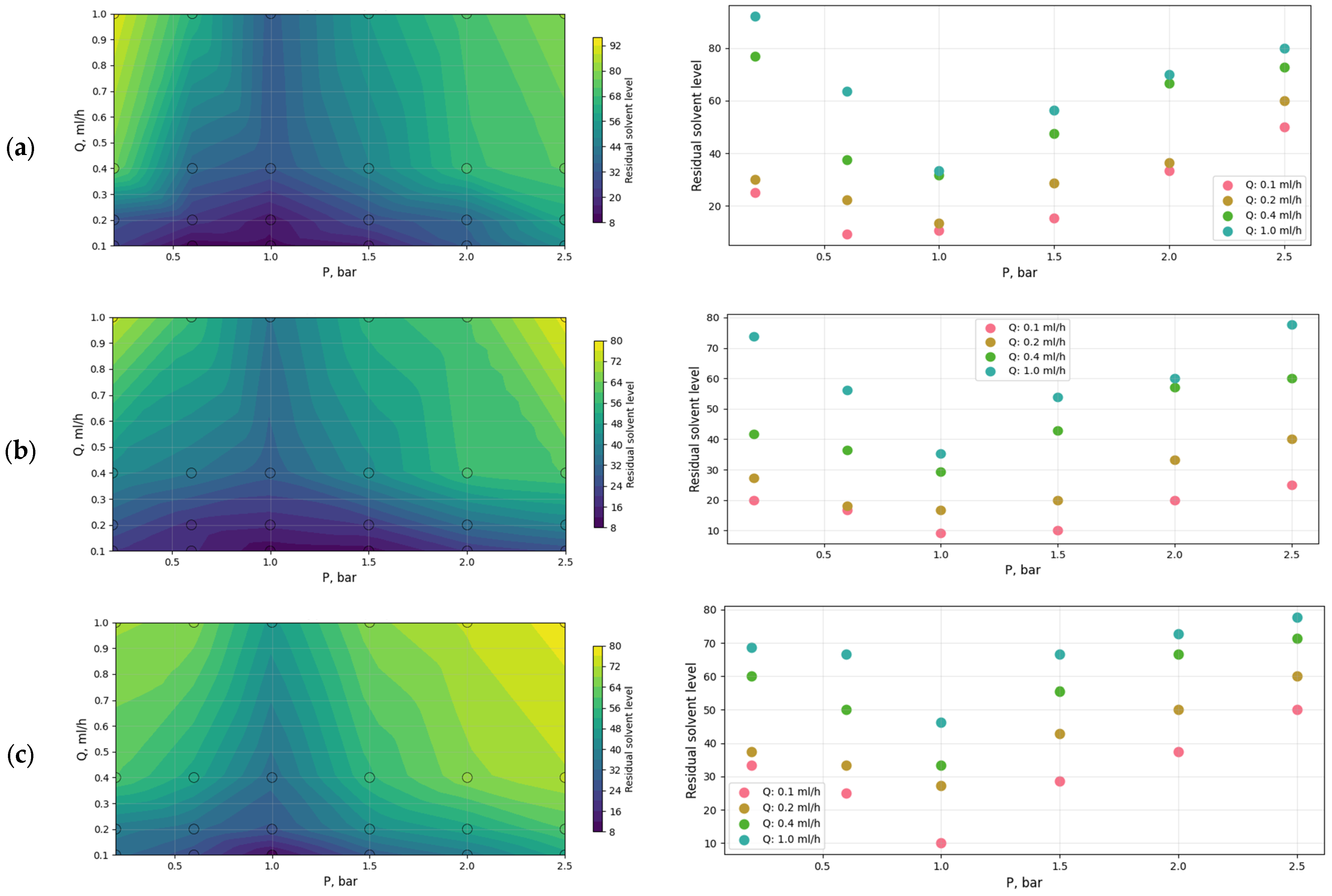

3.1.1. Residual Solvent Content

3.1.2. Nanofibers Diameter

3.2. Regression Analysis Results

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Castro Monsores, K.G.; da Silva, A.O.; Oliveira, S.D.S.A.; Weber, R.P.; Dias, M.L. Production of Nanofibers from Solution Blow Spinning (SBS). J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 16, 1824–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Su, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.X.; Huang, L.P.; Yu, M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Long, Y.Z. Recent Progress and Challenges in Solution Blow Spinning. Mater. Horiz. 2021, 8, 426–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, D.M.; Correa, D.S.; Medeiros, E.S.; Oliveira, J.E.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Advances in Functional Polymer Nanofibers: From Spinning Fabrication Techniques to Recent Biomedical Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 45673–45701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, R.; Khaliq, J.; Combrinck, M.; Hassanin, A.H.; Shehata, N.; Elnabawy, E.; Shyha, I. Solution Blow Spinning of Polyvinylidene Fluoride Based Fibers for Energy Harvesting Applications: A Review. Polymers 2020, 12, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.; Liu, J.; Cao, Y.; Li, W.; He, C. Efficient Solution Blow Spinning of PAN–CNTs Nanofiber-Based Pressure Sensors with Sandwich Structures. Langmuir 2024, 40, 20515–20525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venugopal, J.; Ramakrishna, S. Applications of Polymer Nanofibers in Biomedicine and Biotechnology. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2005, 125, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobaraki, M.; Liu, M.; Masoud, A.R.; Mills, D.K. Biomedical Applications of Blow-Spun Coatings, Mats, and Scaffolds—A Mini-Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbese, Z.; Alven, S.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Collagen-Based Nanofibers for Skin Regeneration and Wound Dressing Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, Z.; Wu, H. Blowspinning: A New Choice for Nanofibers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 33447–33464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omelko, N.A.; Khalimov, R.I. Composite Matrices for Use in Traumatology and Regenerative Medicine. Nauch. Obozr. Med. Nauki 2022, 6, 89–94. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Xu, X.; Fu, J.; Yu, D.-G.; Liu, Y. Recent Progress in Electrospun Polyacrylonitrile Nanofiber-Based Wound Dressing. Polymers 2022, 14, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.; Guo, S.; Zhang, G.; He, W.; Wu, Y.; Yu, D.-G. Electrospun Structural Hybrids of Acyclovir–Polyacrylonitrile Nanofibers for Modifying Drug Release. Polymers 2021, 13, 4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nataraj, S.K.; Yang, K.S.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Polyacrylonitrile-Based Nanofibers—A State-of-the-Art Review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 487–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Kolla, P.; Yang, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Smirnova, A.; Fong, H. Electrospun Polyacrylonitrile Nanofibrous Membranes with Varied Fiber Diameters and Different Membrane Porosities as Lithium-Ion Battery Separators. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 236, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A.; Hassan, T.; Jabri, T.; Riaz, S.; Khan, A.; Iqbal, K.M.; Khan, S.U.; Wasim, M.; Shah, M.R.; Khan, M.Q.; et al. Electrospun Nanofiber-Based Viroblock/ZnO/PAN Hybrid Antiviral Nanocomposite for Personal Protective Applications. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Song, G.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Z. Preparation of solution blown polyamic acid nanofibers and their imidization into polyimide nanofiber mats. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.S.; da Silva, A.N.; Morimoto, N.I.; Mendes, L.T.; Furlan, R.; Ramos, I. Characterization of an electrospinning process using different PAN/DMF concentrations. Polímeros 2007, 17, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. Effects of polymer concentration and cationic surfactant on the morphology of electrospun polyacrylonitrile nanofibres. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2005, 21, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, S.Y.; Ren, J.; Vancso, G.J. Process optimization and empirical modeling for electrospun polyacrylonitrile (PAN) nanofiber precursor of carbon nanofibers. Eur. Polym. J. 2005, 41, 2559–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, S.F.; Golbabaei, F.; Maddah, B.; Latifi, M.; Pezeshk, H.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Akbar-Khanzadeh, F. Optimization of electrospinning parameters for polyacrylonitrile-MgO nanofibers applied in air filtration. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2016, 66, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Jia, K.; Cheng, B.; Guan, K.; Kang, W.; Ren, Y. Preparation of polyacrylonitrile nanofibers by solution blowing process. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2013, 8, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervez, M.N.; Yeo, W.S.; Mishu, M.M.R.; Talukder, M.E.; Roy, H.; Islam, M.S.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, Y.; Stylios, G.K.; Naddeo, V. Electrospun nanofiber membrane diameter prediction using a combined response surface methodology and machine learning approach. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawlings, J.O.; Pantula, S.G.; Dickey, D.A. Applied Regression Analysis: A Research Tool, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Simonoff, J.S. Handbook of Regression Analysis; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roustaei, N. Application and interpretation of linear-regression analysis. Med. Hypothesis Discov. Innov. Ophthalmol. 2024, 13, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.K.; Shah, R.K.; Sahani, S.K. Regression analysis and forecasting with regression model in economics. Mikailalsys J. Adv. Eng. Int. 2025, 2, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Martínez-Zamora, L.; Mozafari, L.; Bueso, M.C.; Kessler, M.; Artés-Hernández, F. Response surface methodology to optimize the extraction of carotenoids from horticultural by-products—A systematic review. Foods 2023, 12, 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Lin, L.; Chen, G.; Du, Z. Prediction and optimization of electrospun polyacrylonitrile fiber diameter based on grey system theory. Materials 2019, 12, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecka, K.; Wojasiński, M.; Ciach, T.; Sajkiewicz, P. Solution blow spinning of polycaprolactone—Rheological determination of spinnability and the effect of processing conditions on fiber diameter and alignment. Materials 2021, 14, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena, C.R.; Silva, M.J.; Malmonge, L.F.; Malmonge, J.A. Poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) sub-microfibers produced by solution blow spinning. J. Polym. Res. 2018, 25, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daristotle, J.L.; Behrens, A.M.; Sandler, A.D.; Kofinas, P. A Review of the Fundamental Principles and Applications of Solution Blow Spinning. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 34951–34963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasireddi, R.; Kruse, J.; Vakili, M.; Kulkarni, S.; Keller, T.F.; Monteiro, D.C.F.; Trebbin, M. Solution Blow Spinning of Polymer/Nanocomposite Micro-/Nanofibers with Tunable Diameters and Morphologies Using a Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, A.; Senz, V.; Schmidt, W.; Huling, J.; Grabow, N.; Illner, S. General Image Fiber Tool: A Concept for Automated Evaluation of Fiber Diameters in SEM Images. Measurement 2021, 177, 109265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coefficients | b0 | b1 | b2 | b3 | b4 | b5 | b6 |

| Values | 300.48 | 37.19 | −16.59 | 16.26 | −2.29 | 4.11 | −0.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Menshutina, N.; Kunaev, D.; Abramov, A.; Aleksandr, A. Polyacrylonitrile Nanofiber Mats Produced by Solution Blow Spinning: Influence of Process Parameters on Fiber Diameter and Residual Solvent Content. Polymers 2026, 18, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010100

Menshutina N, Kunaev D, Abramov A, Aleksandr A. Polyacrylonitrile Nanofiber Mats Produced by Solution Blow Spinning: Influence of Process Parameters on Fiber Diameter and Residual Solvent Content. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010100

Chicago/Turabian StyleMenshutina, Natalia, Danil Kunaev, Andrey Abramov, and Alekseev Aleksandr. 2026. "Polyacrylonitrile Nanofiber Mats Produced by Solution Blow Spinning: Influence of Process Parameters on Fiber Diameter and Residual Solvent Content" Polymers 18, no. 1: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010100

APA StyleMenshutina, N., Kunaev, D., Abramov, A., & Aleksandr, A. (2026). Polyacrylonitrile Nanofiber Mats Produced by Solution Blow Spinning: Influence of Process Parameters on Fiber Diameter and Residual Solvent Content. Polymers, 18(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010100