Pine Bark as a Lignocellulosic Resource for Polyurethane Production: An Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biomass and Chemicals

2.2. Water Extraction of Pine Bark

2.3. Characterization of Pine Bark and Isolated Extractives

2.4. Oxypropylation of Pine Bark Extractives

2.5. Characterization of Polyols

2.6. PUR Foam Preparation

2.7. PUR Foam Characteristics

3. Results and Discussion

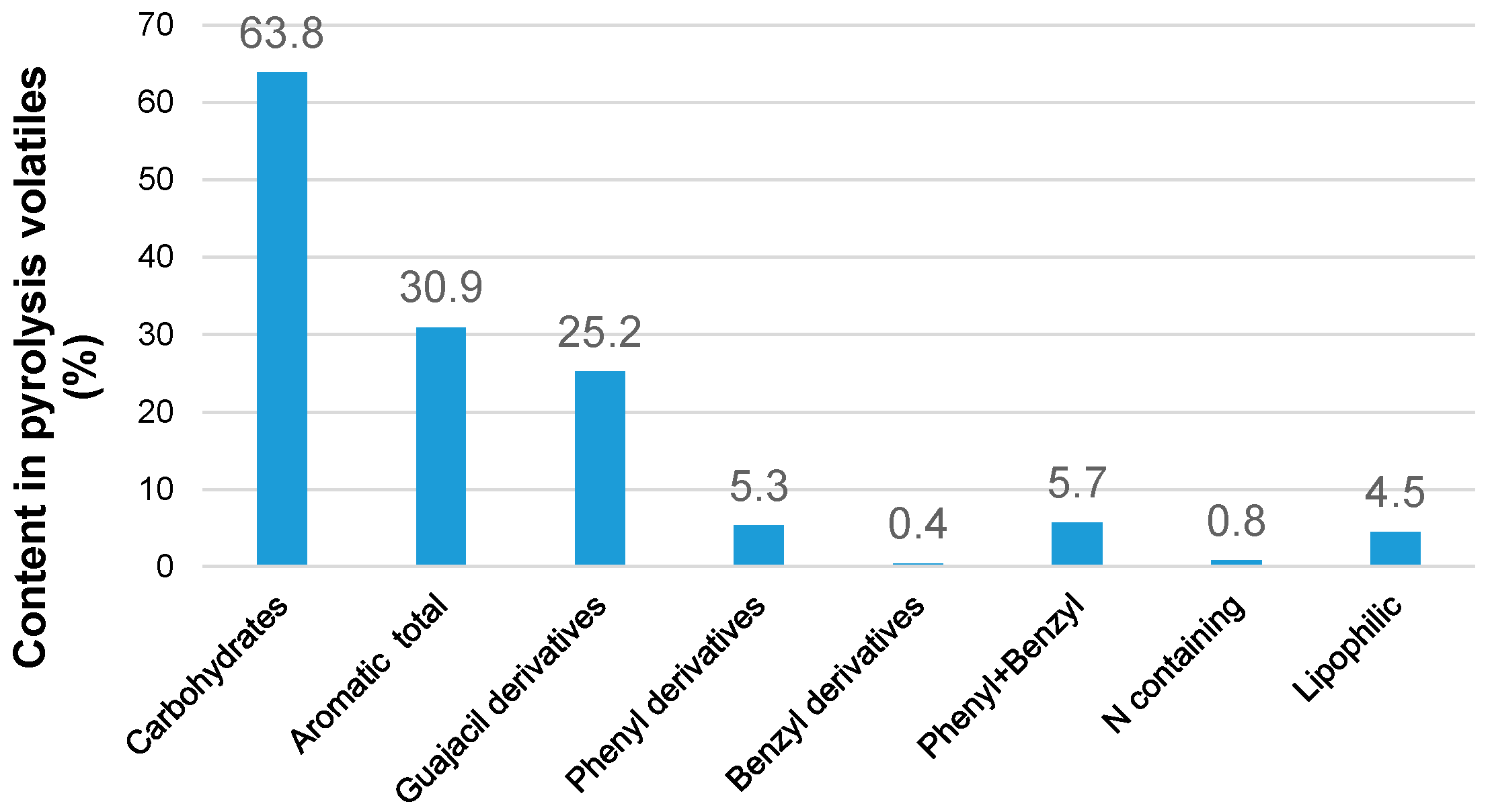

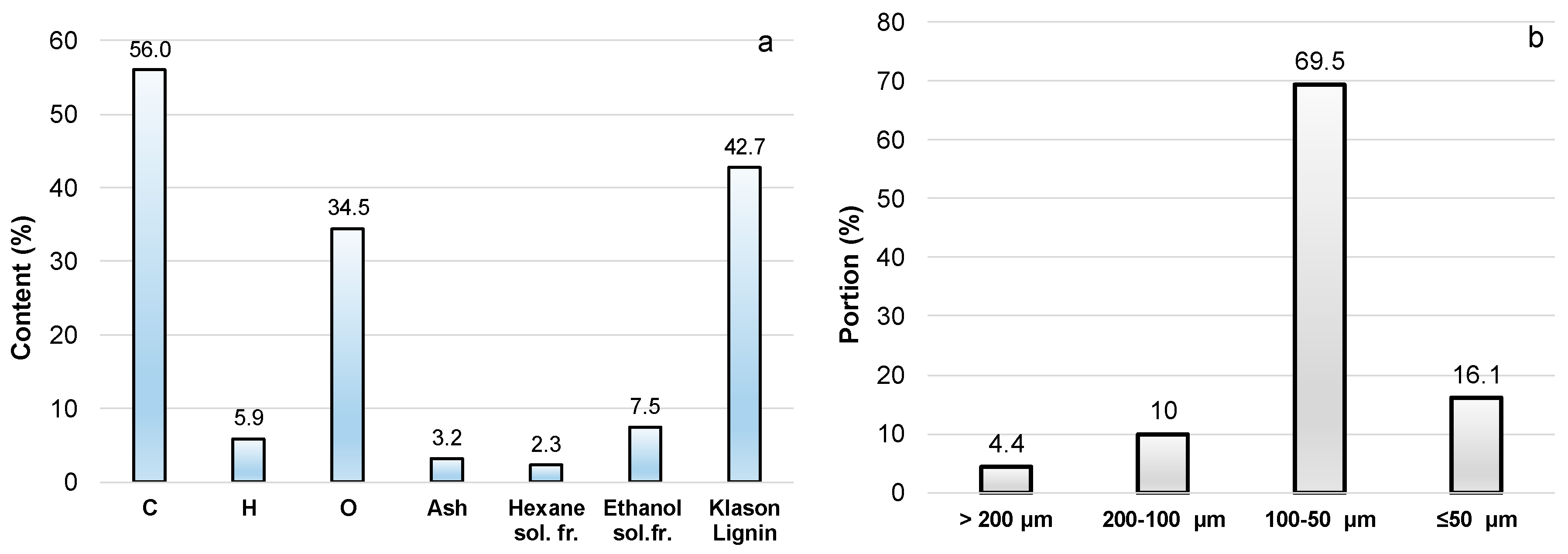

3.1. Characterization of Pine Bark

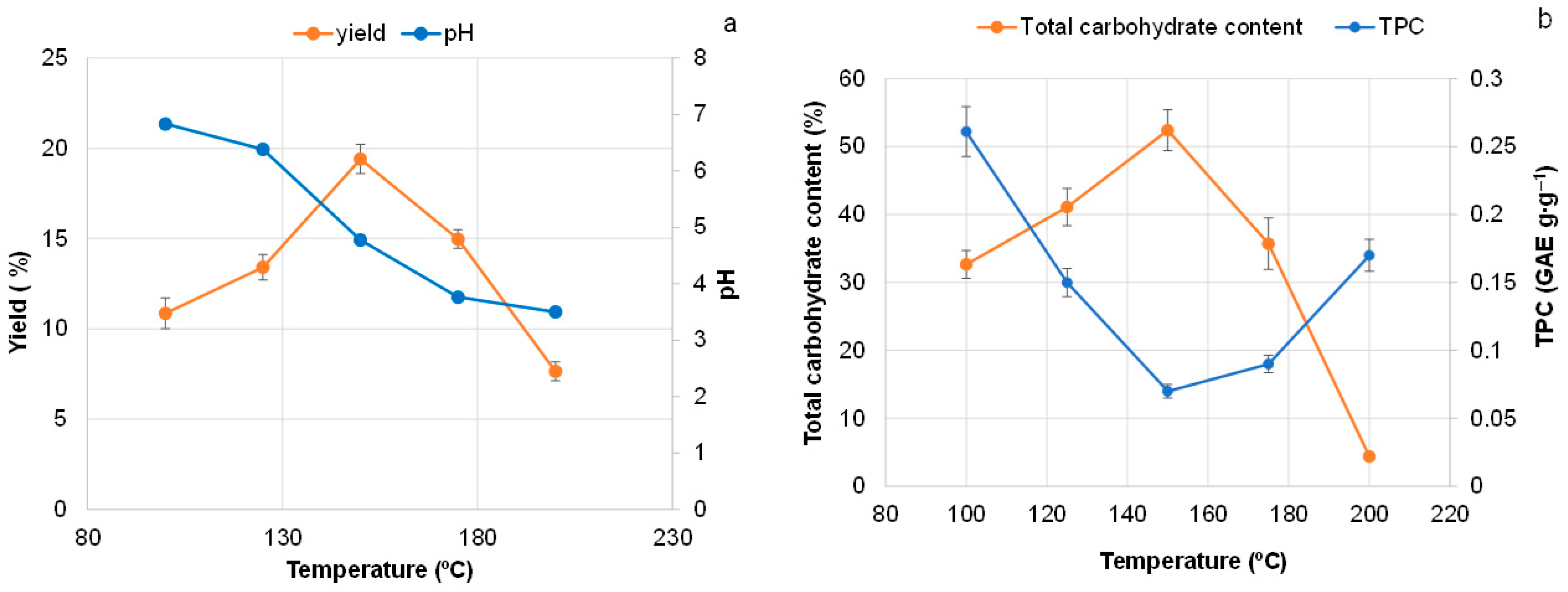

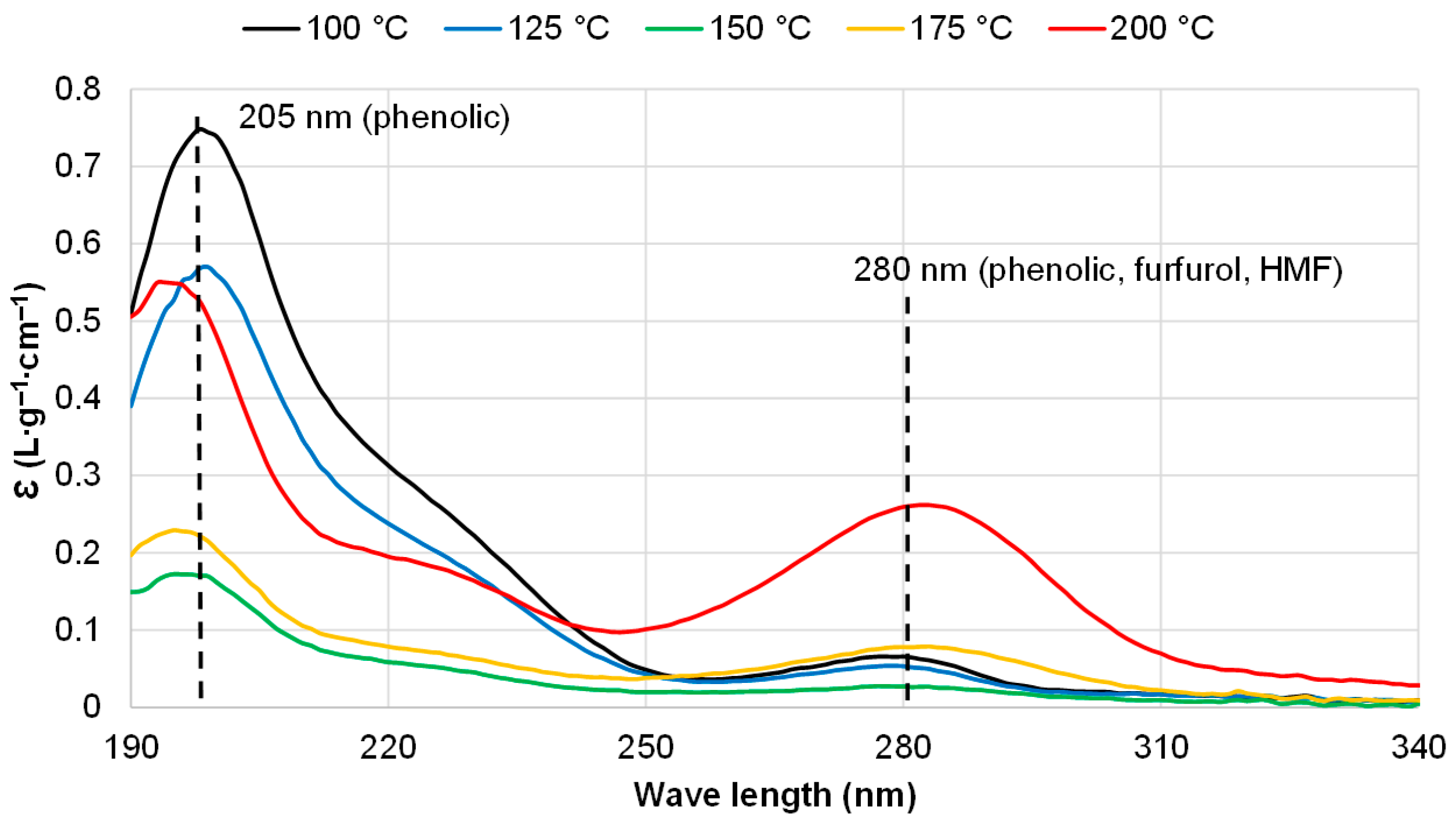

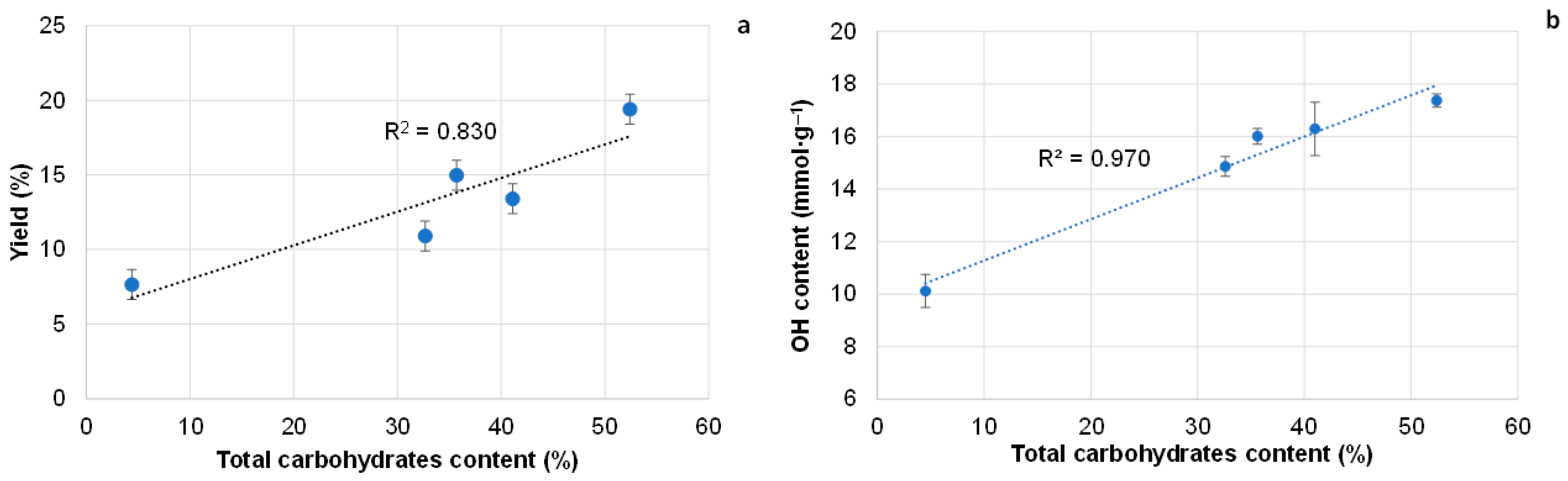

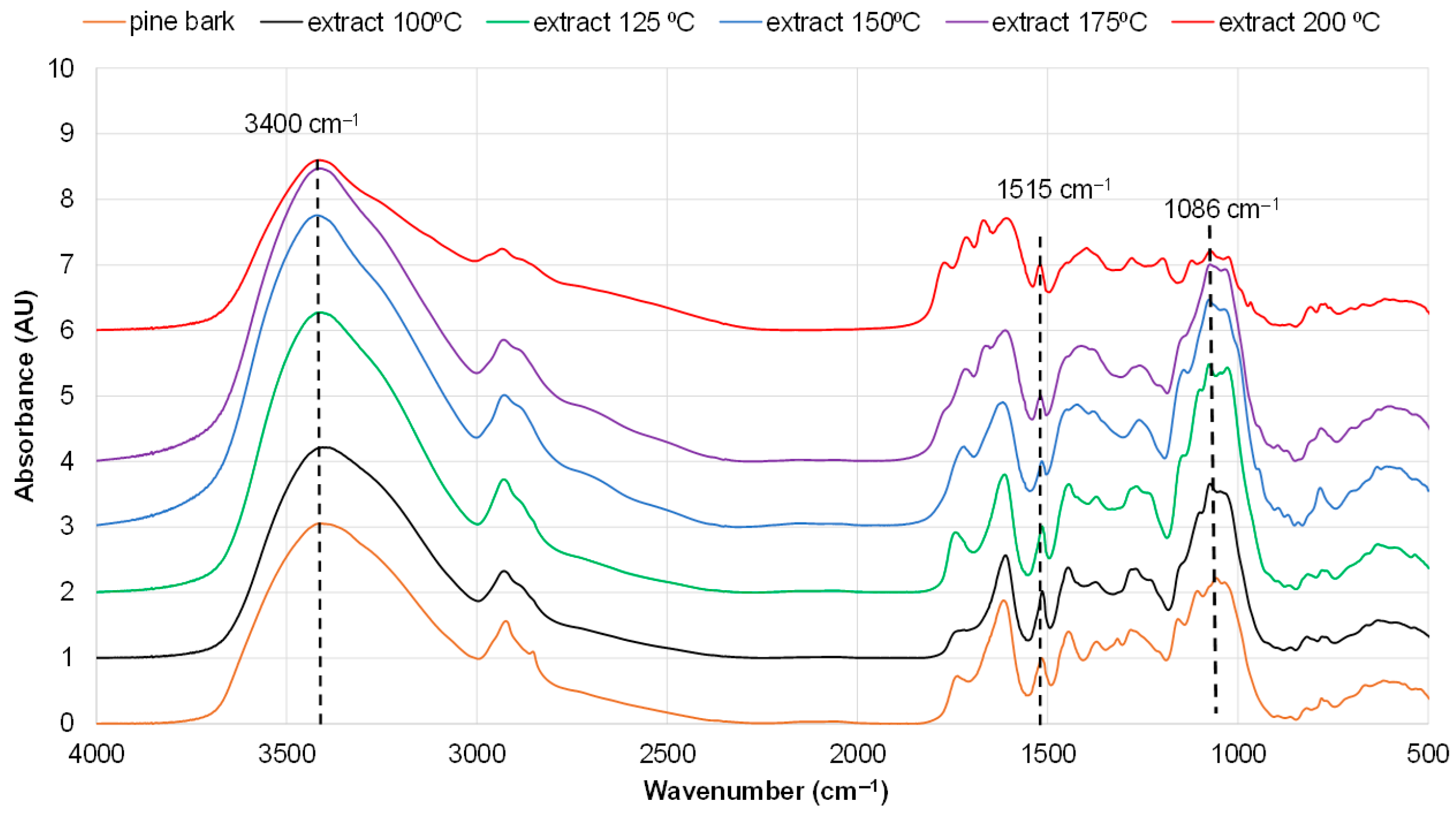

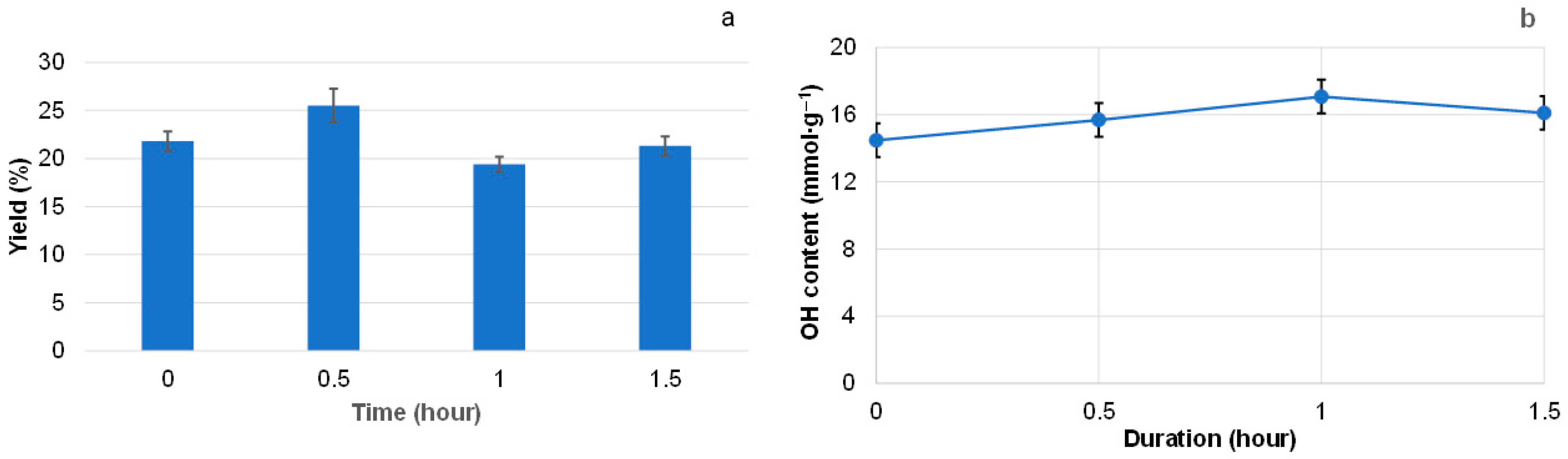

3.2. Effect of Extraction Regimes on the Yield of Extractives and Their Composition

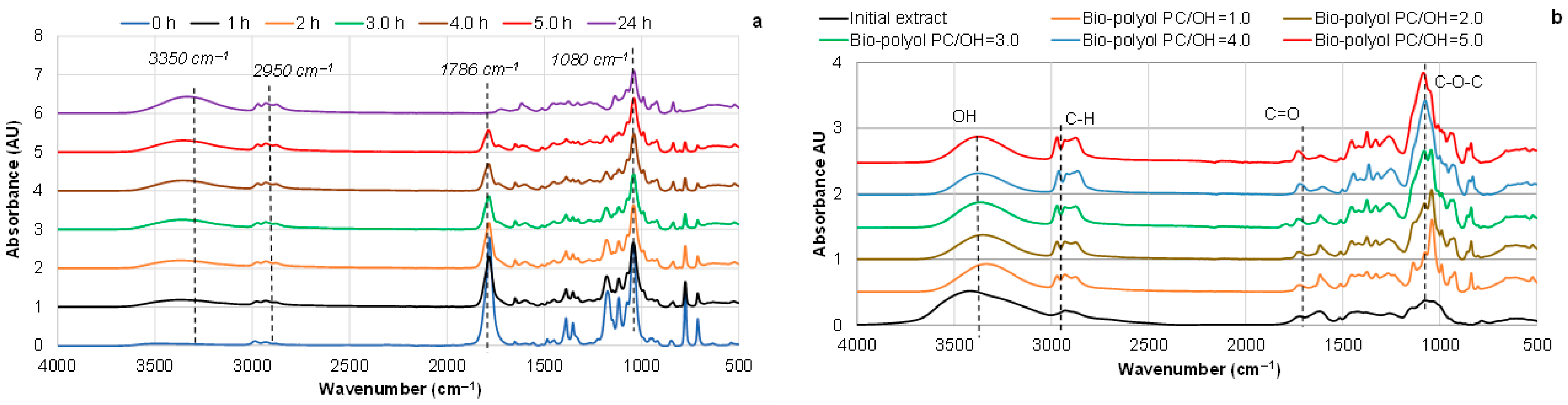

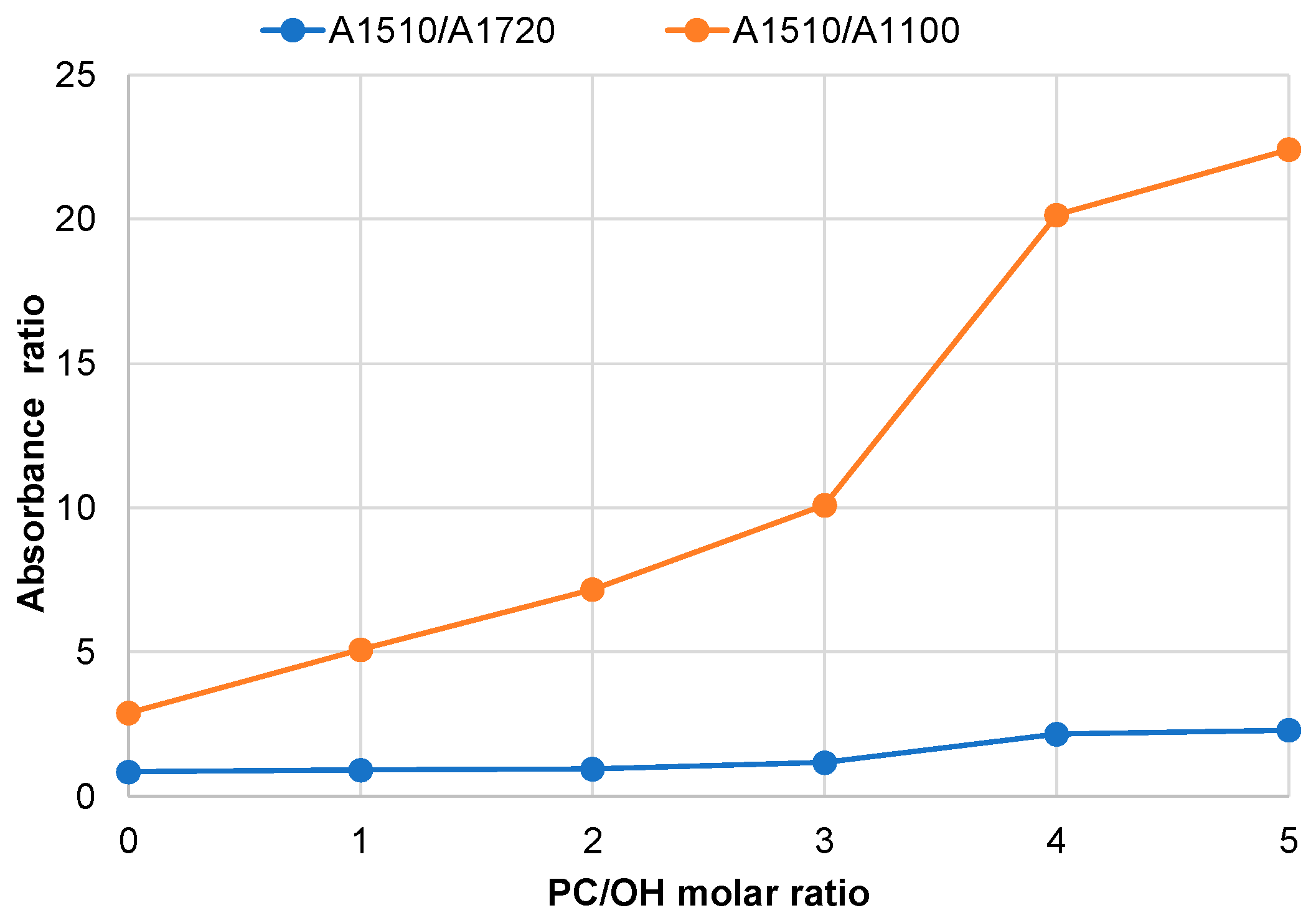

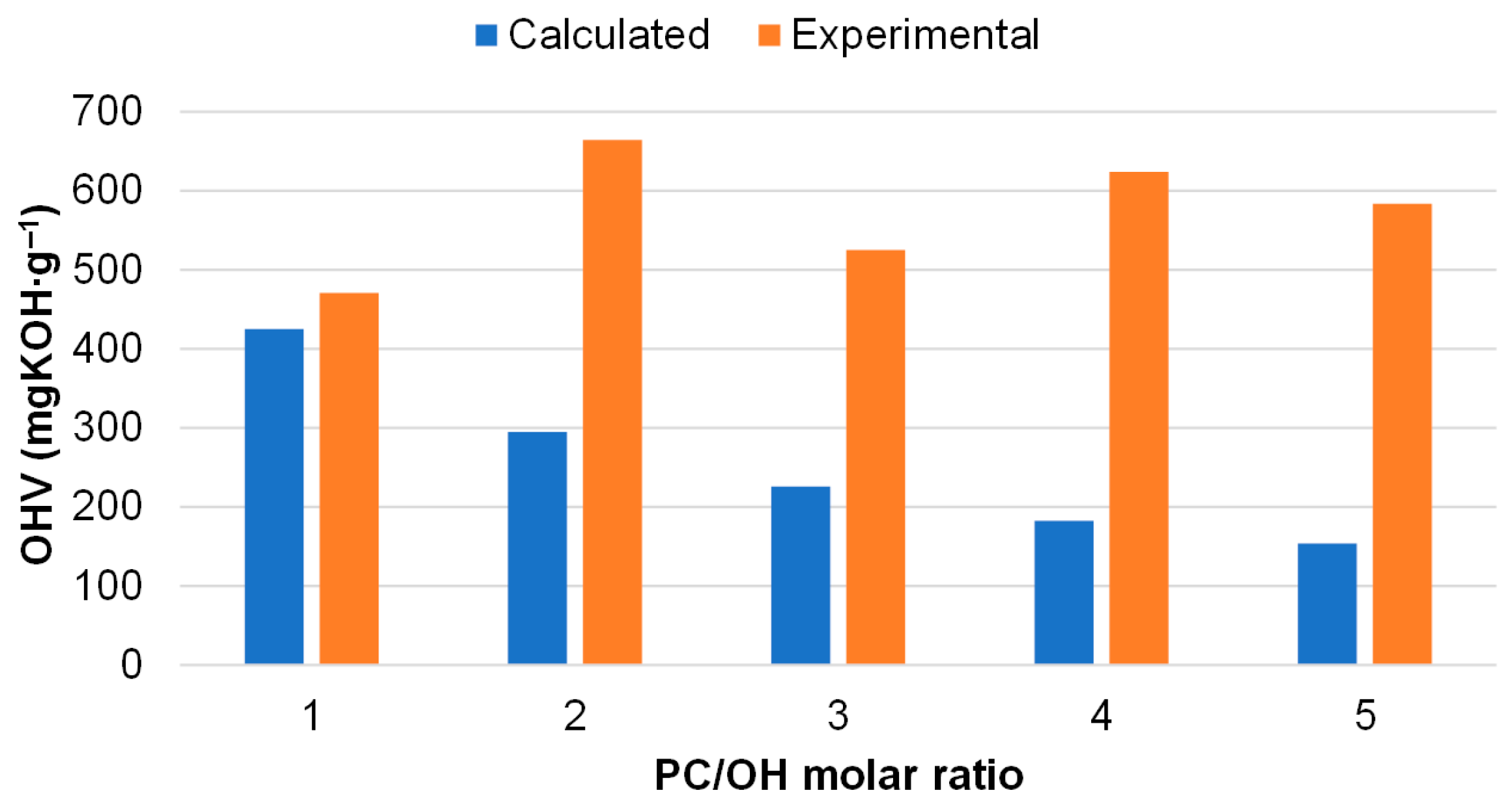

3.3. Effect of PC/OH Molar Ratio on the Oxypropylation of Pine Bark Extractives and Properties of Ensuing Polyols

3.4. Characteristics of PUR Foams on the Basis of Synthesized Bio-Polyols

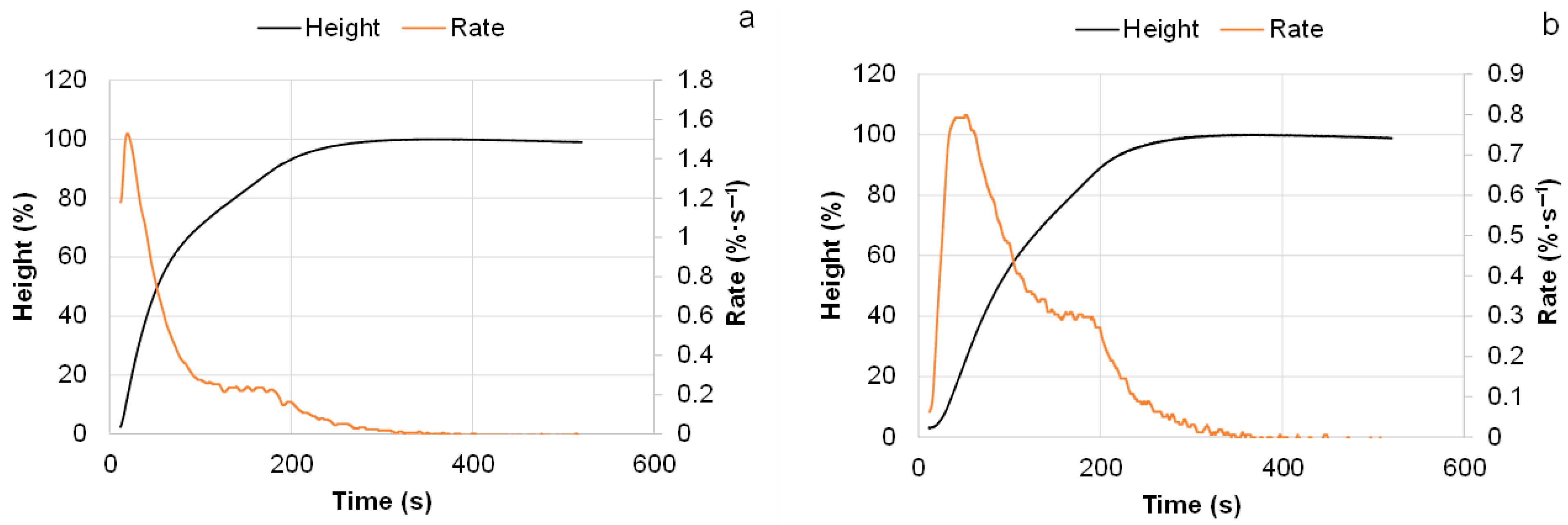

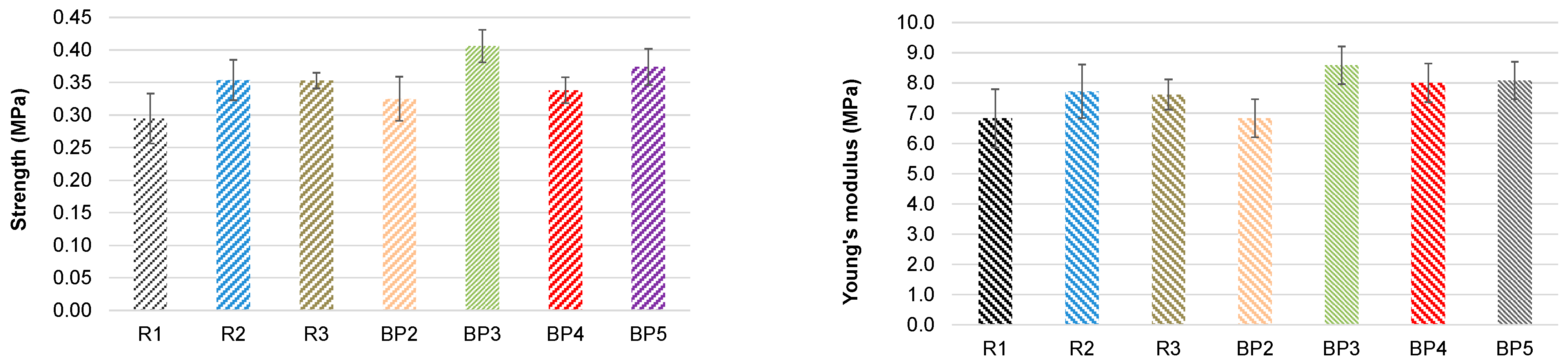

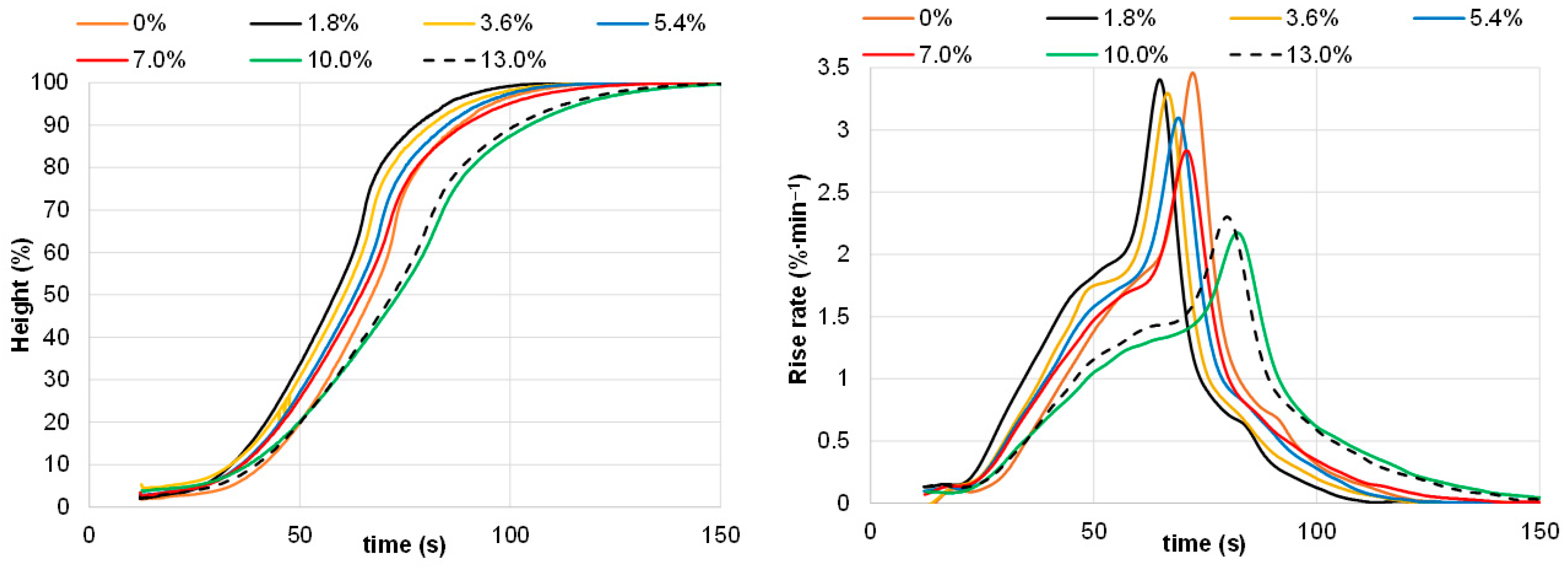

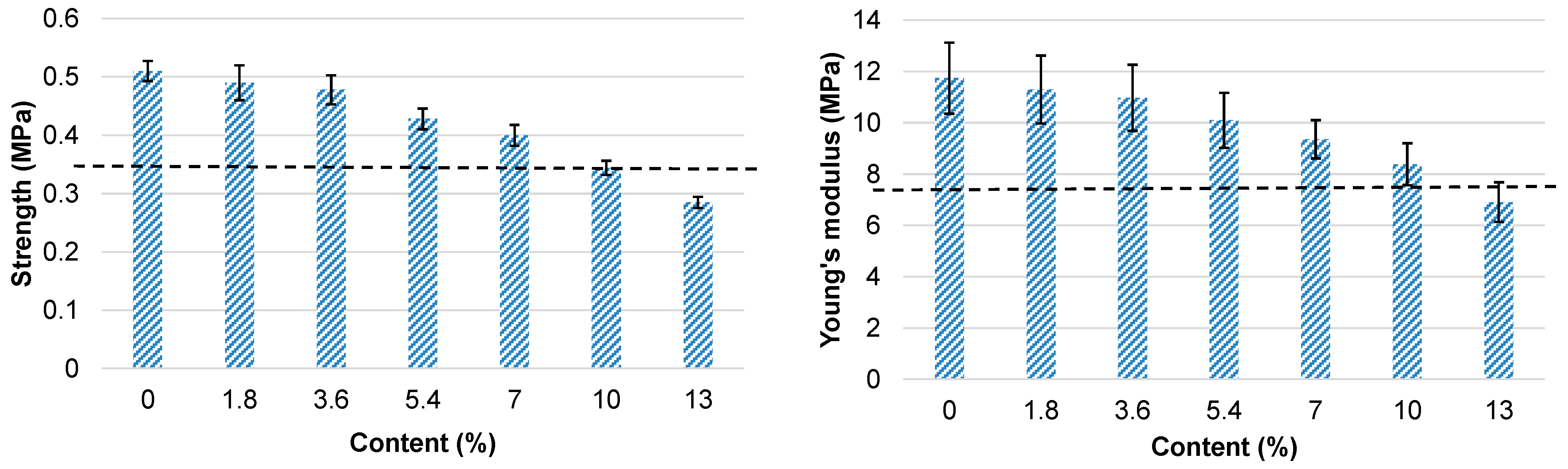

3.4.1. Effect of the Substitution Extent of Commercial Polyols with Bio-Polyol on the Foaming Behavior, Morphology, Mechanical Properties, and Thermal Degradation of PUR Foams

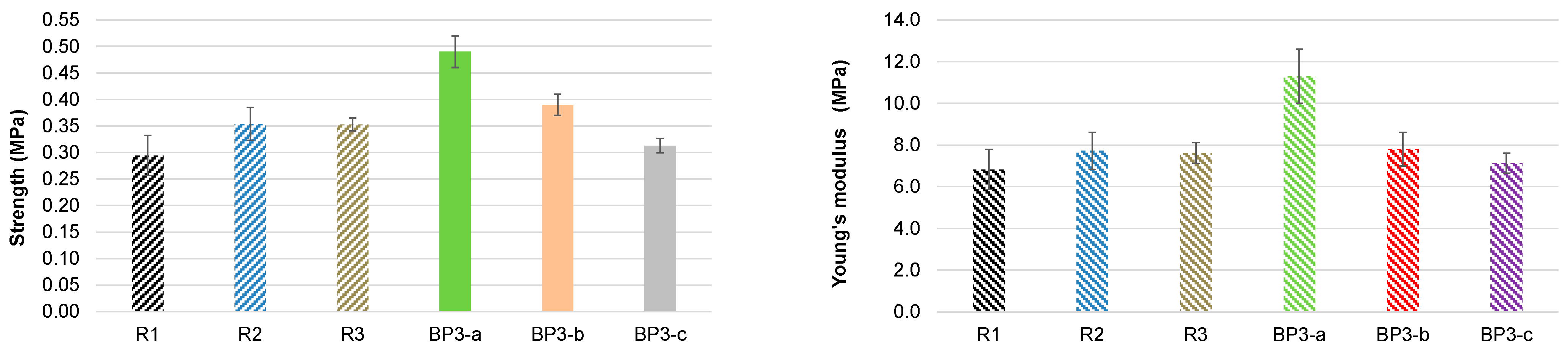

3.4.2. The Extracted Pine Bark as a Natural Filler of Bio-Polyol Based PUR Foams

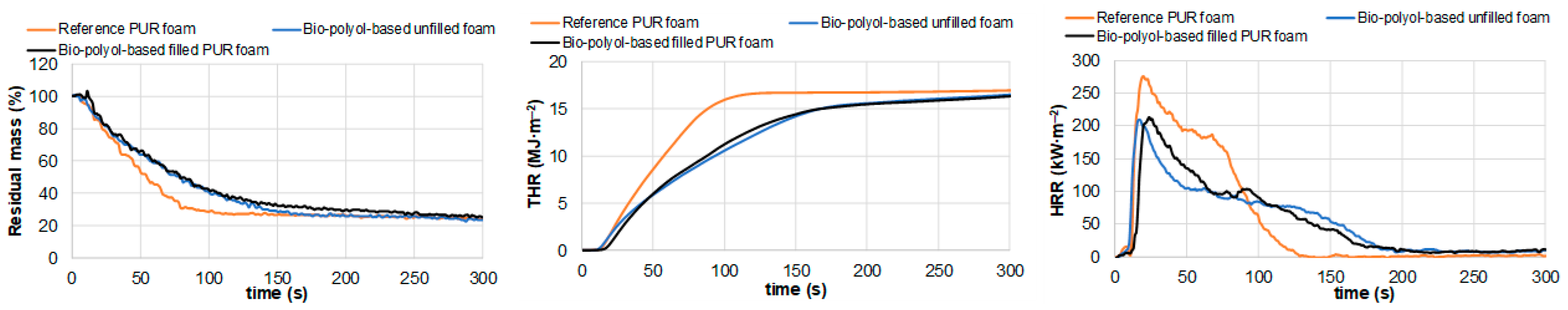

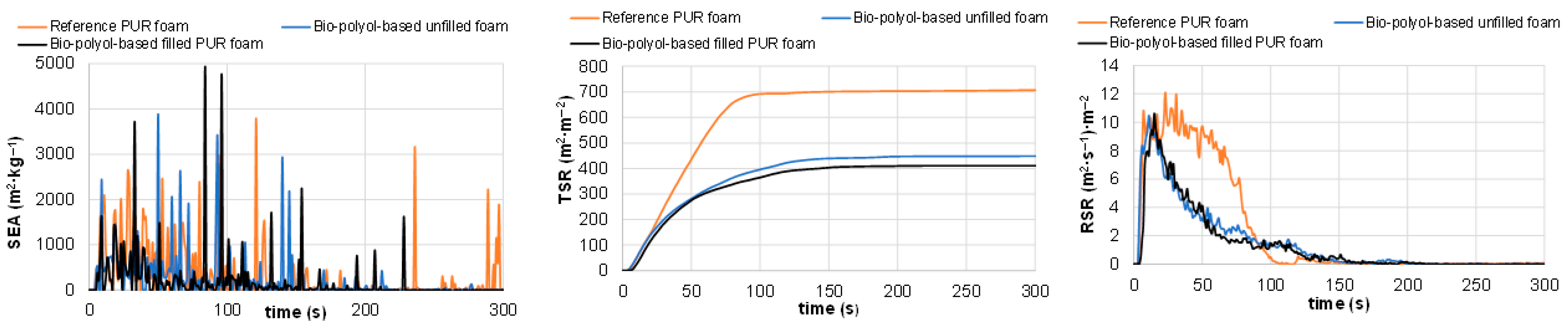

3.4.3. Cone Calorimetric Tests of Reference and Pine Bark Biomass-Containing PUR Foams

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PU | Polyurethane |

| PUR foam | Rigid polyurethane foam |

| PO | Propylene oxide |

| PC | Propylene carbonate |

| pMDI | Polymeric methane disicyanate |

| TCPP | Tris(1-chloro-2-propyl)phosphate |

| DBU | 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene |

| OHV | Hydroxyl value |

| pbw | Part by weight |

| KL | Klason lignin |

| TTI | Time to ignition |

| TFO | Time to flameout |

| THR | Total heat release |

| TSR | Total smoke release |

| PHRR | Peak heat release rate |

| MARHE | Maximal average heat emission |

| Av-EHC | Average effective heat of combustion |

| Av-CO2Y | Average CO2 emission |

| Av-COY | Average CO emission |

References

- European Commission Plastics Strategy. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/plastics-strategy_en (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Statista Market Volume of Polyurethane Worldwide from 2015 to 2025, with a Forecast for 2022 to 2029. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/720341/global-polyurethane-market-size-forecast/ (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- NOVA European Bioplastics. Available online: https://www.european-bioplastics.org/tag/nova-institut/ (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Saunders, K.J. Polyurethanes. In Organic Polymer Chemistry; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 358–387. ISBN 9789401070317. [Google Scholar]

- Jayalath, P.; Ananthakrishnan, K.; Jeong, S.; Shibu, R.P.; Zhang, M.; Kumar, D.; Yoo, C.G.; Shamshina, J.L.; Therasme, O. Bio-Based Polyurethane Materials: Technical, Environmental, and Economic Insights. Processes 2025, 13, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristri, M.A.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Yadav, S.M.; Antov, P.; Papadopoulos, A.N.; Pizzi, A.; Fatriasari, W.; Ismayati, M.; Iswanto, A.H. Recent Developments in Lignin- and Tannin-Based Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane Resins for Wood Adhesives—A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Song, Y.; Lin, Y.; Yin, X.; Zuo, M.; Zhao, Y.; Tao, X.; Zheng, Q. Progress in Study of Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 6517–6527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubens, M.; Van Wesemael, M.; Feghali, E.; Luntadila Lufungula, L.; Blockhuys, F.; Vanbroekhoven, K.; Eevers, W.; Vendamme, R. Exploring the Reactivity of Aliphatic and Phenolic Hydroxyl Groups in Lignin Hydrogenolysis Oil towards Urethane Bond Formation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 180, 114703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García González, M.N.; Börjesson, P.; Levi, M.; Turri, S. Development and Life Cycle Assessment of Polyester Binders Containing 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid and Their Polyurethane Coatings. J. Polym. Environ. 2018, 26, 3626–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, G.; Gaudio, M.T.; Lopresto, C.G.; Calabro, V.; Curcio, S.; Chakraborty, S. Bioplastic from Renewable Biomass: A Facile Solution for a Greener Environment. Earth Syst. Environ. 2021, 5, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung Hai, T.A.; Tessman, M.; Neelakantan, N.; Samoylov, A.A.; Ito, Y.; Rajput, B.S.; Pourahmady, N.; Burkart, M.D. Renewable Polyurethanes from Sustainable Biological Precursors. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 1770–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supriyadi, D.; Damayanti, D.; Veigel, S.; Hansmann, C.; Gindl-Altmutter, W. Unlocking the Potential of Tree Bark: Review of Approaches from Extractives to Materials for Higher-Added Value Products. Mater. Today Sustain. 2025, 29, 101074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pásztory, Z.; Ronyecz Mohácsiné, I.; Gorbacheva, G.; Börcsök, Z. The Utilization of Tree Bark. BioResources 2016, 11, 7859–7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, S.S.; Glasser, W.G.; Ward, T.C. Engineering Plastics from Lignin XIV. Characterization of Chain-Extended Hydroxypropyl Lignins. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 1988, 8, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, J.; George, B.; Camargo, R.; Yan, N. Synthesis and Characterization of Bio-Polyols through the Oxypropylation of Bark and Alkaline Extracts of Bark. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 76, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, W.G.; Barnett, C.A.; Rials, T.G.; Saraf, V.P. Engineering Plastics from Lignin II. Characterization of Hydroxyalkyl Lignin Derivatives. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1984, 29, 1815–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cateto, C.A.; Barreiro, M.F.; Rodrigues, A.E.; Belgacem, M.N. Optimization Study of Lignin Oxypropylation in View of the Preparation of Polyurethane Rigid Foams. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 2583–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pals, M.; Lauberte, L.; Ponomarenko, J.; Lauberts, M.; Arshanitsa, A. Microwave-Assisted Water Extraction of Aspen (Populus tremula) and Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) Barks as a Tool for Their Valorization. Plants 2022, 11, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshanitsa, A.; Ponomarenko, J.; Pals, M.; Jashina, L.; Lauberts, M. Impact of Bark-Sourced Building Blocks as Substitutes for Fossil-Derived Polyols on the Structural, Thermal, and Mechanical Properties of Polyurethane Networks. Polymers 2023, 15, 3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshanitsa, A.; Pals, M.; Godina, D.; Bikovens, O. The Oxyalkylation of Hydrophilic Black Alder Bark Extractives with Propylene Carbonate with a Focus on Green Polyols Synthesis. J. Renew. Mater. 2024, 12, 1927–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnel, I.; Saake, B.; Lehnen, R. Oxyalkylation of Lignin with Propylene Carbonate: Influence of Reaction Parameters on the Ensuing Bio-Based Polyols. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 101, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnel, I.; Saake, B.; Lehnen, R. Comparison of Different Cyclic Organic Carbonates in the Oxyalkylation of Various Types of Lignin. React. Funct. Polym. 2017, 120, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, F.R.; Barros-Timmons, A.; Evtuguin, D.V.; Pinto, P.C.R. Effect of Different Catalysts on the Oxyalkylation of Eucalyptus Lignoboost® Kraft Lignin. Holzforschung 2020, 74, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech-Polak, J.; Oliwa, R.; Oleksy, M.; Budzik, G. Rigid Polyurethane Foams with Improved Flame Resistance. Polimery 2018, 63, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uram, K.; Leszczyńska, M.; Prociak, A.; Czajka, A.; Gloc, M.; Leszczyński, M.K.; Michałowski, S.; Ryszkowska, J. Polyurethane Composite Foams Synthesized Using Bio-Polyols and Cellulose Filler. Materials 2021, 14, 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciorek-Sadowska, J.; Borowicz, M.; Isbrandt, M.; Czupryński, B.; Apiecionek, Ł. The Use of Waste from the Production of Rapeseed Oil for Obtaining of New Polyurethane Composites. Polymers 2019, 11, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augaitis, N.; Vaitkus, S.; Członka, S.; Kairytė, A. Research of Wood Waste as a Potential Filler for Loose-Fill Building Insulation: Appropriate Selection and Incorporation into Polyurethane Biocomposite Foams. Materials 2020, 13, 5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeney, A.B.; Harris, P.J.; Henry, R.J.; Stone, B.A. A Simple and Rapid Preparation of Alditol Acetates for Monosaccharide Analysis. Carbohydr. Res. 1983, 113, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshanitsa, A.; Ponomarenko, J.; Lauberte, L.; Jurkjane, V.; Pals, M.; Akishin, Y.; Lauberts, M.; Jashina, L.; Bikovens, O.; Telysheva, G. Advantages of MW-Assisted Water Extraction, Combined with Steam Explosion, of Black Alder Bark in Terms of Isolating Valuable Compounds and Energy Efficiency. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 181, 114832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. [14] Analysis of Total Phenols and Other Oxidation Substrates and Antioxidants by Means of Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent. In Oxidants and Antioxidants Part A; Methods in enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 152–178. ISBN 9780121822002. [Google Scholar]

- Zakis, G.F. Functional Analysis of Lignins and Their Derivatives; TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1994; ISBN 7610898522587. [Google Scholar]

- Arshanitsa, A.; Pals, M.; Vevere, L.; Jashina, L.; Bikovens, O. The Complex Valorization of Black Alder Bark Biomass in Compositions of Rigid Polyurethane Foam. Materials 2024, 18, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, A.; Kosmela, P.; Vēvere, L.; Kirpluks, M.; Cabulis, U.; Piszczyk, Ł. Effect of Bio-Polyol Molecular Weight on the Structure and Properties of Polyurethane-Polyisocyanurate (PUR-PIR) Foams. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werkelin, J.; Skrifvars, B.-J.; Hupa, M. Ash-Forming Elements in Four Scandinavian Wood Species. Part 1: Summer Harvest. Biomass Bioenergy 2005, 29, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Mesquita, L.M.; Contieri, L.S.; e Silva, F.A.; Bagini, R.H.; Bragagnolo, F.S.; Strieder, M.M.; Sosa, F.H.B.; Schaeffer, N.; Freire, M.G.; Ventura, S.P.M.; et al. Path2Green: Introducing 12 Green Extraction Principles and a Novel Metric for Assessing Sustainability in Biomass Valorization. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 10087–10106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrote, G.; Domínguez, H.; Parajó, J.C. Interpretation of Deacetylation and Hemicellulose Hydrolysis during Hydrothermal Treatments on the Basis of the Severity Factor. Process Biochem. 2002, 37, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, S.; Kroslakova, I.; Janzon, R.; Mayer, I.; Saake, B.; Pichelin, F. Characterization of Condensed Tannins and Carbohydrates in Hot Water Bark Extracts of European Softwood Species. Phytochemistry 2015, 120, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soukup-Carne, D.; Fan, X.; Esteban, J. An Overview and Analysis of the Thermodynamic and Kinetic Models Used in the Production of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural and Furfural. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 442, 136313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xi, G.; Yu, K.; Yu, H.; Wang, X. Furfural Production from Biomass–Derived Carbohydrates and Lignocellulosic Residues via Heterogeneous Acid Catalysts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 98, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristescu, C.; Karlsson, O. Changes in Content of Furfurals and Phenols in Self-Bonded Laminated Boards. Bioresources 2013, 8, 4056–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, R.M.; Webster, F.X.; Kiemle, D. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds, 7th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 9781118311653. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-C.; Litt, M.H. Ring-Opening Polymerization of Ethylene Carbonate and Depolymerization of Poly(Ethylene Oxide-co-Ethylene Carbonate). Macromolecules 2000, 33, 1618–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, A.; Avérous, L. Oxyalkylation of Condensed Tannin with Propylene Carbonate as an Alternative to Propylene Oxide. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 3103–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, M. Chemistry and Technology of Polyols for Polyurethanes; Rapra Technology: Shriopshire, UK, 2005; Volume 1, ISBN 9781910242131. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, M.C.; O’Toole, B.; Jackovich, D. Cell Morphology and Mechanical Properties of Rigid Polyurethane Foam. J. Cell. Plast. 2005, 41, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, D.K.; Webster, D.C. Thermal Stability and Flame Retardancy of Polyurethanes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2009, 34, 1068–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.; Aramburu, A.B.; Beltrame, R.; Gatto, D.A.; Amico, S.; Labidi, J.; Delucis, R.d.A. Wood Flour Modified by Poly(Furfuryl Alcohol) as a Filler in Rigid Polyurethane Foams: Effect on Water Uptake. Polymers 2022, 14, 5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Avila Delucis, R.; Magalhães, W.L.E.; Petzhold, C.L.; Amico, S.C. Forest-based Resources as Fillers in Biobased Polyurethane Foams. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 45684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanzadeh, R.; Fathi, S.; Azdast, T.; Rostami, M. Theoretical Investigation and Optimization of Radiation Thermal Conduction of Thermal-Insulation Polyolefin Foams. IUST 2020, 17, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczewski, M.; Kurańska, M.; Sałasińska, K.; Michałowski, S.; Prociak, A.; Uram, K.; Lewandowski, K. Rigid Polyurethane Foams Modified with Thermoset Polyester-Glass Fiber Composite Waste. Polym. Test. 2020, 81, 106190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukarska, D.; Walkiewicz, J.; Derkowski, A.; Mirski, R. Properties of Rigid Polyurethane Foam Filled with Sawdust from Primary Wood Processing. Materials 2022, 15, 5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.-W.; Sung, W.-F.; Chu, H.-S. Thermal Conductivity of Polyurethane Foams. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 1999, 42, 2211–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelle, B.P. Traditional, State-of-the-Art and Future Thermal Building Insulation Materials and Solutions—Properties, Requirements and Possibilities. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 2549–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.-C. Orientation Effect on Cone Calorimeter Test Results to Assess Fire Hazard of Materials. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 172, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Liu, D.-Y.; Liang, W.-J.; Li, F.; Wang, J.-S.; Liu, Y.-Q. Bi-Phase Flame-Retardant Actions of Water-Blown Rigid Polyurethane Foam Containing Diethyl-N,N-Bis(2-Hydroxyethyl) Phosphoramide and Expandable Graphite. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2017, 124, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, F.; Pan, J.; Guo, L.; Deng, J.; Wang, D.; Bai, Z.; Ren, S.; Su, C.; Pan, C.; Tian, Z. Synergistic Effect of Modified Carbon Nanotubes and Magnesium Hydroxide on Flame Retardancy and Smoke Suppression of Silicone Rubber Foam. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 244, 111835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.G.; Lee, J.S.; Ma, B.C. Understanding the Flame Retardant Mechanism of Intumescent Flame Retardant on Improving the Fire Safety of Rigid Polyurethane Foam. Polymers 2022, 14, 4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babrauskas, V. Ignition Handbook: Principles and Applications to Fire Safety Engineering, Fire Investigation, Risk Management and Forensic Science; Fire Science Publishers: Issaquah, WA, USA, 2003; ISBN 0-9728111-3-3. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, M.; Wan, C. Density Effect on Flame Retardancy, Thermal Degradation, and Combustibility of Rigid Polyurethane Foam Modified by Expandable Graphite or Ammonium Polyphosphate. Polymers 2019, 11, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Content on DM, % | Mean 1 |

|---|---|

| Carbon | 52.8 ± 0.5 |

| Hydrogen | 6.1 ± 0.05 |

| Nitrogen | 0.42 ± 0.04 |

| Ash | 2.6 ± 0.2 |

| Lignin (by TAPPI 222 2-om): | |

| Acid insoluble (Klason Lignin) | 31.7 ± 0.3 |

| Acid soluble | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| Total | 33.2 ± 0.3 |

| Extractives 2: | |

| Hexane soluble | 3.2 ± 0.2 |

| Ethanol (96%) soluble | 16.8 ± 0.3 |

| Total | 21.0 ± 0.4 |

| Monomeric carbohydrates content 3 | 38.5 ± 2.4 |

| Content on DM | Mean 2 |

|---|---|

| Carbon (%) | 41.2 ± 0.5 |

| Hydrogen (%) | 6.10 ± 0.05 |

| Nitrogen (%) | 0.42 ± 0.02 |

| Ash (%) | 2.6 ± 0.2 |

| TPC (GAE g∙g−1) | 0.08 ± 0.02 |

| Monomeric carbohydrate (%) 1 | 57.4 ± 2.2 |

| ΣOH group (mmol∙g−1) | 16.0 ± 0.1 |

| Nr. 1 | PC/OH Molar Ratio | PC/Extract Weight Ratio | Content in Bio-Polyol (% w/w) 2 | Reaction Time (h) | OHV (mg KOH∙g−1) | Viscosity (25 °C) at 50 s−1 (Pa∙s) | H2O by K.F (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass | DBU | 150 °C | 170 °C | ||||||

| 1 | - | - | 100.0 | - | - | - | 846 ± 21 | - | - |

| 2 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 50.2 | 5.8 | 24 | 0 | 471 ± 19 | >1000 | 0.25 |

| 3 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 34.9 | 4.0 | 24 | 6 | 664 ± 21 | 85.1 ± 5.1 | 0.20 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 4.6 | 26.7 | 3.1 | 24 | 8 | 527 ± 18 | 14.9 ± 2.1 | 0.16 |

| 5 | 4.0 | 6.2 | 21.6 | 2.5 | 24 | 16 | 624 ± 27 | 9.9 ± 1.6 | 0.13 |

| 6 | 5.0 | 7.7 | 18.2 | 2.1 | 24 | 24 | 584 ± 39 | 8.6 ± 0.6 | 0.08 |

| 7 3 | 3.0 | 4.6 | 26.7 | 6.0 | 24 | 0 | 710 ± 17 | 9.2 ± 1 | 0.09 |

| 8 4 | 3.0 | 4.6 | 26.7 | 3.1 | 0 | 24 | 592 ± 21 | 210 ± 250 | 0.11 |

| Position | R1 | R2 | 50% Substitution of Lupranol 3300 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R3 | BP2 | BP3 | BP4 | BP5 | |||

| Composition (pbw): | |||||||

| Lupranol 3300 | 100 | - | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Lupranol 3422 | - | 100 | 50 | - | - | - | - |

| Bio-polyol (PC/OH = 2) | - | - | - | 50 | - | - | - |

| Bio-polyol (PC/OH = 3) | - | - | - | - | 50 | - | - |

| Bio-polyol (PC/OH = 4) | - | - | - | - | - | 50 | - |

| Bio-polyol (PC/OH = 5) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 50 |

| Water | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Catalyst Polycat | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Surfactant, Niax Silicone | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Blowing agent, Opteon TM 1100 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Plasticizer TCPP | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Isocyanate pMDI | 119.5 | 144.1 | 133.7 | 155.6 | 136.9 | 150.1 | 144.7 |

| B/A ratio 1 | 0.89 | 1.08 | 1.0 | 1.16 | 1.02 | 1.12 | 1.08 |

| Position | PUR Foam System | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| BP3-a | BP3-b | BP3-c | |

| Composition (pbw): | |||

| 1 Bio-polyol Nr. 4 | 100 | - | - |

| 1 Bio-polyol Nr. 7 | - | 100 | - |

| 1 Bio-polyol Nr. 8 | - | - | 100 |

| Water | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Catalyst Polycat | - | - | - |

| Surfactant, Niax Silicone | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Blowing agent, Opteon TM 1100 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Plasticizer TCPP | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Isocyanate pMDI | 154.3 | 201.4 | 172.2 |

| B/A ratio | 1.16 | 1.54 | 1.29 |

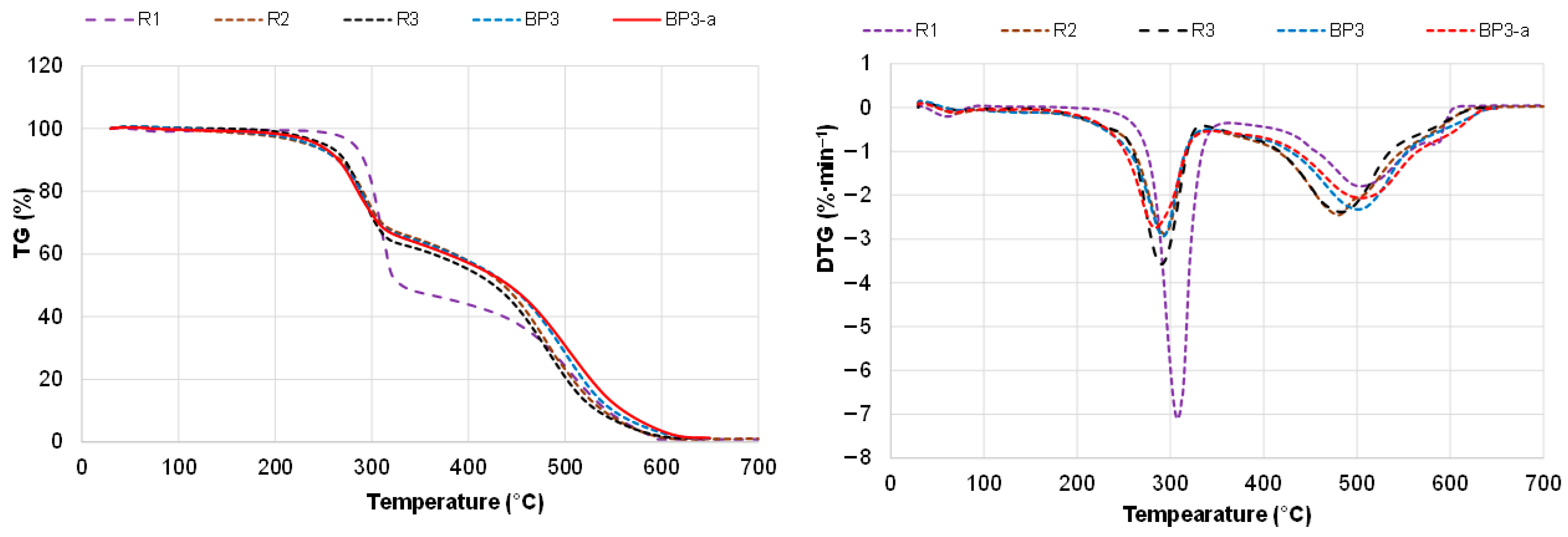

| Sample | T5% (°C) 1 | max (%∙min−1) 2 | Tmax (°C) 3 | T50% (°C) 4 | Δm500°C (%) 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | 282 ± 6 | 7.1 ± 0.4 | 308 ± 8 | 350 ± 10 | 24.2 ± 1.0 |

| R2 | 233 ± 5 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 294 ± 4 | 427 ± 6 | 20.8 ± 0.8 |

| R3 | 251 ± 5 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 291 ± 5 | 425 ± 10 | 20.7 ± 0.7 |

| BP3 | 236 ± 2 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 291 ± 4 | 440 ± 8 | 28.5 ± 1.2 |

| BP3a | 244 ± 5 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 284 ± 6 | 442 ± 7 | 30.8 ± 0.8 |

| Parameters | Abbreviation | PUR Foam Compositions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Bio-Polyol-Based Unfilled | Bio-Polyol-Based Filled | ||

| Apparent density, kg∙m−3 | - | 52 ± 1 | 48 ± 1 | 50 ± 1 |

| Time to ignition, s | TTI | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 5.7 ± 1 |

| Time to flameout, s | TFO | 133 ± 10 | 166 ± 14 | 180 ± 14 |

| Mass loss, % | Δm | 81.0 ± 1.3 | 80.4 ± 0.8 | 84.2 ± 3.2 |

| Average mass loss rate, %∙s−1 | Av-MLR | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.43 ± 0.05 |

| Total heat release, MJ∙m−2 | THR | 17.4 ± 0.6 | 17.8 ± 0.4 | 18.8 ± 0.8 |

| Peak heat release rate, kW∙m−2 | PHRR | 278 ± 2 | 208 ± 9 | 207 ± 5 |

| Maximum average rate of heat emission, kW∙m−2 | MARHE | 175.8 ± 7.6 | 124.4 ± 5.6 | 124.7 ± 3.3 |

| Average effective heat of combustion, MJ∙kg−1 | Av-EHC | 15.4 ± 1 | 18.5 ± 0.4 | 18.1 ± 0.3 |

| Total smoke release, m2∙m−2 | TSR | 764 ± 51 | 476 ± 21 | 479 ± 31 |

| Average carbon dioxide yield, kg∙kg−1 | Av-CO2Y | 1.70 ± 0.02 | 2.10 ± 0.05 | 2.06 ± 0.11 |

| Average carbon monoxide yield, kg∙kg−1 | Av-COY | 0.082 ± 0.002 | 0.132 ± 0.011 | 0.145 ± 0.015 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arshanitsa, A.; Pals, M.; Vjalikova, A.; Vevere, L.; Bikovens, O.; Jashina, L. Pine Bark as a Lignocellulosic Resource for Polyurethane Production: An Evaluation. Polymers 2026, 18, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010096

Arshanitsa A, Pals M, Vjalikova A, Vevere L, Bikovens O, Jashina L. Pine Bark as a Lignocellulosic Resource for Polyurethane Production: An Evaluation. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010096

Chicago/Turabian StyleArshanitsa, Alexander, Matiss Pals, Alexandra Vjalikova, Laima Vevere, Oskars Bikovens, and Lilija Jashina. 2026. "Pine Bark as a Lignocellulosic Resource for Polyurethane Production: An Evaluation" Polymers 18, no. 1: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010096

APA StyleArshanitsa, A., Pals, M., Vjalikova, A., Vevere, L., Bikovens, O., & Jashina, L. (2026). Pine Bark as a Lignocellulosic Resource for Polyurethane Production: An Evaluation. Polymers, 18(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010096