Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity in Pellet-Based 3D-Printed Polymer Structures for Advanced Heat Management in Electrical Devices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Polymer Pellets

2.2. Manufacturing of Printed Structures

2.3. Observation of Printed Structures

2.4. Thermal Conductivity Measurement

2.5. Dielectric Measurement

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microscopic Analysis of Printed Structures

3.2. Results of Thermal Conductivity

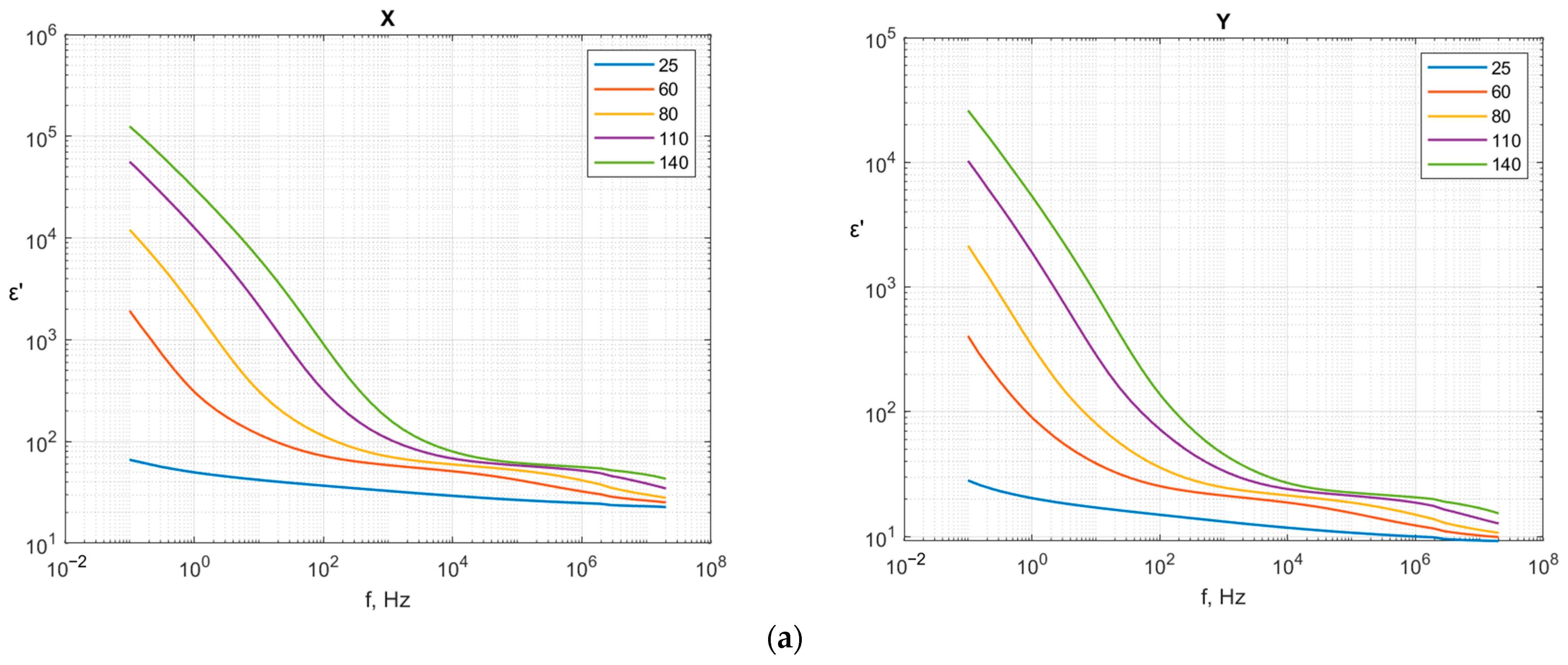

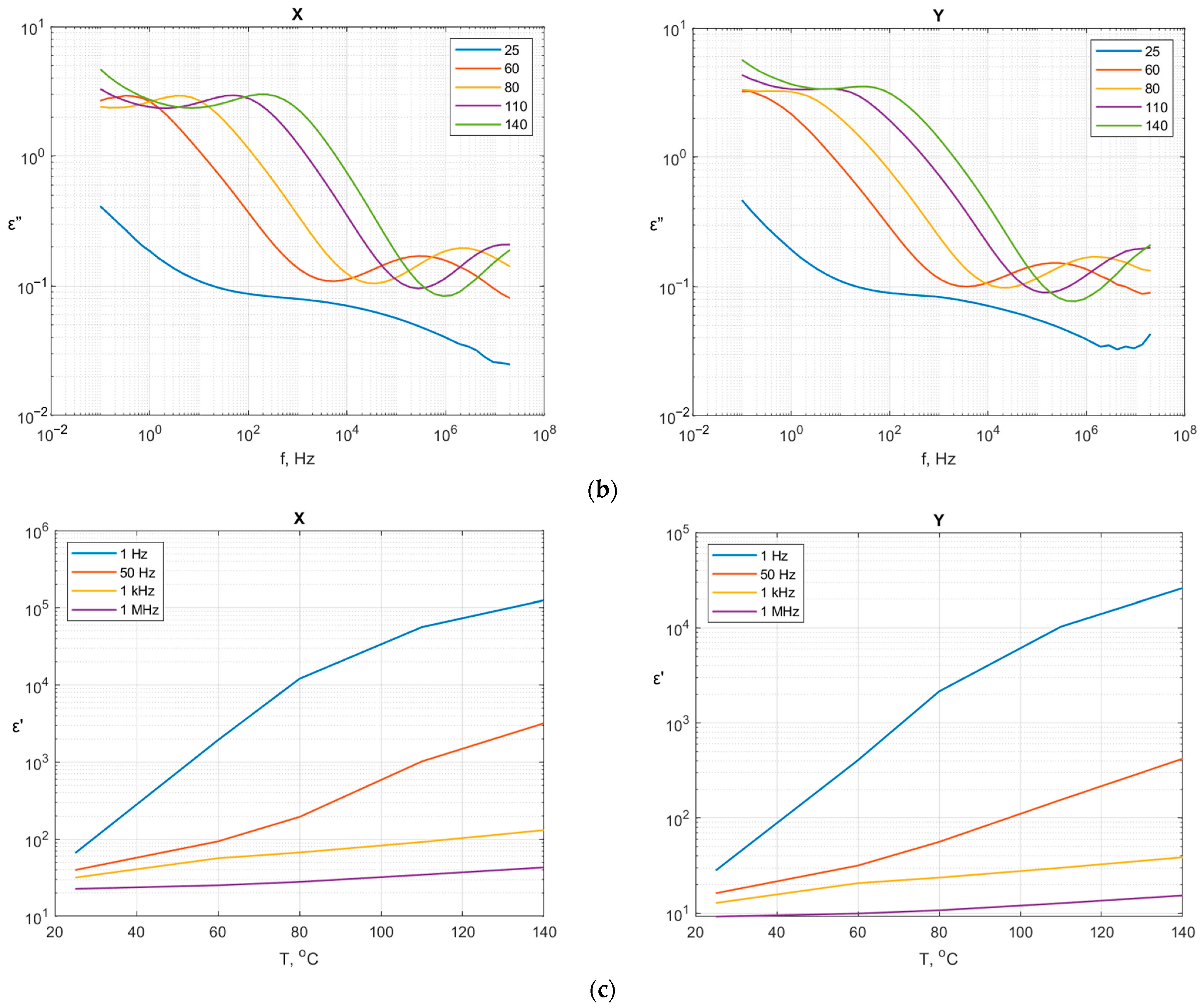

3.3. Dielectric Properties

- Filler orientation effect: the platelet-shaped mineral fillers, when aligned parallel to the electric field direction (sample X), create more extensive interfacial regions perpendicular to the field, enhancing interfacial polarization. The flake-like morphology observed in the microscopic analysis (see Figure 2) supports this interpretation. Studies on mica and clay-filled polymer composites have reported similar orientation-dependent dielectric behavior, with anisotropy ratios ranging from 1.1 to 1.8, depending on the filler aspect ratio and loading [38,39];

- Matrix microstructure effect: the FGF printing process may induce preferential orientation of PA6 crystallites and chain alignment along the extrusion direction. Previous studies on FDM-printed PA6 composites have demonstrated that processing-induced molecular orientation can significantly affect dielectric properties, with aligned chains exhibiting higher polarizability along the orientation axis [36].

4. Conclusions

- Filler orientation dominates thermal transport—the parallel alignment of mineral fillers yields thermal conductivity of 4.09 W/m·K compared to 1.21 W/m·K for perpendicular orientation, representing a 238% enhancement. This demonstrates that manufacturing process control is critical for optimizing thermal performance;

- Strong thermal anisotropy was achieved—the anisotropy ratio of 3.4 is one of the highest reported for electrically insulating 3D-printed thermoplastic composites. This directional heat transfer capability enables targeted thermal management in confined spaces;

- A significant reduction in thermal resistance was obtained—parallel-oriented samples exhibited 70% lower thermal resistance (24.8 × 10−4 m2·K/W) compared to samples with a perpendicular orientation (82.6 × 10−4 m2·K/W). For a typical heat flux of 10 W/cm2, this translates to a 58 °C reduction in temperature rise, directly improving device reliability;

- Electrical insulation was maintained—despite the enhanced thermal conductivity, the material preserved excellent dielectric properties with low dielectric loss (tan δ < 0.05 at 1 kHz) and high surface resistivity (4 × 1014 Ω), meeting requirements for electrical insulation in medium-voltage applications;

- Industrial scalability is possible—the pellet-based FGF process enables direct use of industrial-grade polymer composites without intermediate filament production, reducing cost and expanding material options for thermal management applications in electrical devices.

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dhumal, A.R.; Kulkarni, A.P.; Ambhore, N.H. A Comprehensive Review on Thermal Management of Electronic Devices. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2023, 70, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benisi Ghadim, H.; Godin, A.; Veillere, A.; Duquesne, M.; Haillot, D. Review of Thermal Management of Electronics and Phase Change Materials. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 208, 115039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orville, T.; Tajwar, M.; Bihani, R.; Saha, P.; Hannan, M.A. Enhancing Thermal Efficiency in Power Electronics: A Review of Advanced Materials and Cooling Methods. Thermo 2025, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Hasnain, S.M.M.; Paramasivam, P.; Ayanie, A.G. Advancing Thermal Management in Electronics: A Review of Innovative Heat Sink Designs. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jebelli, A.; Lotfi, N.; Zare, M.S.; Yagoub, M.C.E. Advanced Thermal Management for High-Power ICs: Optimizing Heatsink and Airflow Design. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hu, Y. Advancing Thermal Management Technology for Power Semiconductors through Materials and Interface Engineering. Acc. Mater. Res. 2025, 6, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.-J.; Park, J.-B.; Jeon, Y.-P.; Hong, J.-Y.; Park, H.-S.; Lee, J.-U. A Review of Polymer Composites Based on Carbon Fillers for Thermal Management Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, Y.-J.; Yoon, Y.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Chung, D.-C.; Kim, B.-J. Carbon Nanotube/Polymer Composites for Functional Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, C.; Yang, Y.; Fu, C.; Ma, F.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, G. Graphene-based polymer composites in thermal management: Materials, structures and applications. Mater. Horiz. 2025, 12, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, S.; Khastgir, D. Thermal Conductivity of Polymer–Carbon Composites. In Carbon-Containing Polymer Composites; Springer Series on Polymer and Composite Materials; Rahaman, M., Khastgir, D., Aldalbahi, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, A.; Malinowski, L.; Adamus-Wlodarczyk, A.; Ulanski, P. Thermally Conductive Shape Memory Polymer Composites Filled with Boron Nitride for Heat Management in Electrical Insulation. Polymers 2021, 13, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaska, K.; Rybak, A.; Kapusta, C.; Sekula, R.; Siwek, A. Enhanced thermal conductivity of epoxy–matrix composites with hybrid fillers. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2014, 26, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, A.; Nieroda, J. Aluminosilicate-epoxy resin composite as novel material for electrical insulation with enhanced mechanical properties and improved thermal conductivity. Polym. Compos. 2019, 40, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, A. Functional Polymer Composite with Core-Shell Ceramic Filler: II. Rheology, Thermal, Mechanical, and Dielectric Properties. Polymers 2021, 13, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, A.; Gaska, K.; Kapusta, C.; Toche, F.; Salles, V. Epoxy composites with ceramic core–shell fillers for thermal management in electrical devices. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2017, 28, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaska, K.; Kmita, G.; Rybak, A.; Sekula, R.; Goc, K.; Kapusta, C. Magnetic-aligned, magnetite-filled epoxy composites with enhanced thermal conductivity. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Dunn, M.L.; Qi, H.J.; Maute, K. Recent Advances in Design Optimization and Additive Manufacturing of Composites. NPJ Adv. Manuf. 2025, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Choi, J.; Hong, M.; Lee, J.; Choi, Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Choi, W. Recent Advances in Thermal Management via Additive Manufacturing. Eng. Sci. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 1, 025260016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharudin, M.S.; Ullah, A.; Younas, M. Innovative and Sustainable Advances in Polymer Composites for Additive Manufacturing. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.A.; Elsersawy, R.; Khondoker, M.A.H. Pellet-Based Extrusion Additive Manufacturing of Lightweight Parts Using Inflatable Hollow Extrudates. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junk, S.; Herr, M. Comparison of Pellet-Based and Filament-Based Processes in Additive Manufacturing. In Sustainable Design and Manufacturing 2024; Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 112, pp. 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizio, M.; Strano, M.; Farioli, D.; Giberti, H. Extrusion Additive Manufacturing of PEI Pellets. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 6, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Sun, Y.-C.; Lees, I.; Naguib, H.E. Additive Manufacturing of Hybrid Piezoelectric/Magnetic Self-Sensing Actuator Using Pellet Extrusion and Immersion Precipitation with Statistical Modelling Optimization. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2023, 230, 110393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagatella, S.; Castoldi, L.; Cavallaro, M.; Gariboldi, E.; Suriano, R.; Levi, M. 3D-Printable Polymer Composites with Unmodified Boron Nitride for Thermal Management in Flexible Electronics. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, 57316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, I.; Cicala, G.; Recca, G.; Tosto, C. Specific Heat Capacity and Thermal Conductivity Measurements of PLA-Based 3D-Printed Parts with Milled Carbon Fiber Reinforcement. Entropy 2022, 24, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michal, R.; Jedrzej, B.; Andrzej, R.; Filip, G.; Amin, B. Method for Manufacturing of a Thermally Conductive Electrical Component EP4353449A1, 17 April 2024.

- Yoo, G.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Jung, Y.C.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.Y. Anisotropically enhanced thermal conductivity of polymer composites based on segregated nanocarbon networks. Carbon Lett. 2025, 35, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, R.; Liu, M.; Fan, A.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Investigation of Anisotropic Thermophysical Properties of Highly Oriented Carbon Fiber Composites: From One to Three Dimensions. Carbon 2025, 243, 120477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E1530-19; Standard Test Method for Evaluating the Resistance to Thermal Transmission by the Guarded Heat Flow Meter Technique. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Nan, C.W.; Birringer, R.; Clarke, D.R.; Gleiter, H. Effective thermal conductivity of particulate composites with interfacial thermal resistance. J. Appl. Phys. 1997, 81, 6692–6699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, A. Processing Influence on Thermal Conductivity of Polymer Nanocomposites. In Processing of Polymer Nanocomposites; Kenig, S., Ed.; Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co. KG: München, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://www.hanser-elibrary.com/doi/10.3139/9781569906361.016 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Swartz, E.T.; Pohl, R.O. Thermal boundary resistance. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1989, 61, 605–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klett, J.; Hardy, R.; Romine, E.; Walls, C.; Burchell, T. High-thermal-conductivity, mesophase-pitch-derived carbon foams: Effect of precursor on structure and properties. Carbon 2000, 38, 953–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, H.; Rimdusit, S. Very high thermal conductivity obtained by boron nitride-filled polybenzoxazine. Thermochim. Acta 1998, 320, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Lee, S.; Chen, G. Heat transfer in thermoelectric materials and devices. J. Heat Transfer 2013, 135, 061605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Pan, B.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Gao, D.; Wang, Y. Fabrication of a Sensor Based on the FDM-Printed CNT/PA6 Dielectric Layer with Hilbert Fractal Microstructure. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 369, 115190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdum, A.I.; Banu, A.; Enache, L.; Ciuprina, F. Dielectric Properties of PA6-HGB-MWCNT Hybrid Composites. In Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Advanced Topics in Electrical Engineering (ATEE), Bucharest, Romania, 23–25 March 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddabattuni, S.; Schuman, T.P.; Dogan, F. Dielectric Properties of Polymer–Particle Nanocomposites Influenced by Electronic Nature of Filler Surfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 1917–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuncer, E.; Sauers, I.; James, D.R.; Ellis, A.R.; Paranthaman, M.P.; Aytuğ, T.; Sathyamurthy, S.; More, K.L.; Li, J.; Goyal, A. Electrical Properties of Epoxy Resin Based Nano-Composites. Nanotechnology 2007, 18, 025703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Properties | Description or Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Density | 1.68 | g/cm3 |

| HDT, 0.45 MPa | 203 | °C |

| Flexural strength | 105 | MPa |

| Tensile strength | 75 | MPa |

| Tensile strain | 1.1 | % |

| Impact strength | 9 | kJ/m2 |

| Thermal conductivity through-plane | 1.2 | W/m·K |

| Thermal conductivity in-plane | 5.5 | W/m·K |

| Surface resistivity | 4·× 1014 | Ω |

| Dielectric strength | 7.2 | kV/mm |

| Flame class rating, UL 94 | V-0 |

| Settings and Conditions | Value |

|---|---|

| Upper-plate temperature (°C) | 30 |

| Lower-plate temperature (°C) | 10 |

| Ambient temperature (°C) | 20 |

| Measurement type | Through thickness |

| Expected accuracy | Within 5% |

| Sample Type | Sample Thickness 1 (mm) | Thermal Conductivity () | Thermal Resistance () |

|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | 10.12 | 4.12 ± 0.11 | 24.6 ± 0.6 |

| X2 2 | 10.15 | 4.06 ± 0.04 | 25.0 ± 0.2 |

| Y1 2 | 9.85 | 1.20 ± 0.01 | 82.4 ± 0.9 |

| Y2 | 10.16 | 1.23 ± 0.02 | 82.7 ± 1.3 |

| Z | 10.15 | 2.11 ± 0.03 | 48.1 ± 0.7 |

| Polymer Matrix | Filler Type | TC Max | TC Min | TC Anisotropy Ratio | Printing Method | Electrical Properties | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA6 | Mineral (BN-type) | 4.09 | 1.21 | 3.4 | FGF | Insulating | This work |

| Flexible resin | BN platelets (20 wt.%) | 0.73 | 0.51 | 1.4 | VPP | Insulating | [24] |

| PLA | Carbon fiber | 0.20 | 0.16 | 1.2 | FFF | Conductive | [25] |

| Polymer Matrix | Filler Type | Dielectric Constant @ 1 kHz | Dissipation Factor @ 1 kHz | Manufacturing Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA6 | Mineral (BN-type) | 6 ÷ 8 | <0.05 | FGF | This work |

| Flexible resin | BN platelets (20 wt.%) | 8 | 0.2 | VPP | [24] |

| Epoxy resin | BN platelets (30 wt.%) | 4.5 | <0.02 | Vacuum casting | [14] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rzepecki, M.; Rybak, A. Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity in Pellet-Based 3D-Printed Polymer Structures for Advanced Heat Management in Electrical Devices. Polymers 2026, 18, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010093

Rzepecki M, Rybak A. Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity in Pellet-Based 3D-Printed Polymer Structures for Advanced Heat Management in Electrical Devices. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010093

Chicago/Turabian StyleRzepecki, Michal, and Andrzej Rybak. 2026. "Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity in Pellet-Based 3D-Printed Polymer Structures for Advanced Heat Management in Electrical Devices" Polymers 18, no. 1: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010093

APA StyleRzepecki, M., & Rybak, A. (2026). Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity in Pellet-Based 3D-Printed Polymer Structures for Advanced Heat Management in Electrical Devices. Polymers, 18(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010093