2.2. Orthogonal Experimental Design

To investigate the effects of different preparation parameters on the properties of AR, a five-factor, three-level segmented orthogonal experimental design (OED) was employed. OED is a statistical method for studying multiple factors and objectives simultaneously, allowing analysis of combined effects through a limited number of tests. Aromatic oil content (A), crumb rubber content (B), shear temperature (C), shear time (D), and reaction time (E) were selected as the investigated factors. The levels for each factor were set as follows: aromatic oil 4%, 5%, 6%; crumb rubber was divided into low-content group (10%, 15%, 20%) and high-content group (25%, 30%, 35%); shear temperature 180 °C, 200 °C, 220 °C; shear time 60 min, 90 min, 120 min; and reaction time 30 min, 60 min, 90 min. The overall range of crumb rubber content from 10% to 35% was selected to cover the typical dosage used in engineering practice. At lower contents, the viscosity of AR is relatively low, but the improvement in high-temperature performance and elasticity may be insufficient and the effective utilization of crumb rubber is limited. At higher contents, more crumb rubber can be used to enhance stiffness and elasticity and to reduce the binder cost, but the viscosity increases markedly and construction becomes more difficult. Therefore, both low-content and high-content AR needed to be considered in the orthogonal experimental design, and the two dosage ranges were arranged and analyzed separately in the segmented orthogonal experimental design.

Aromatic oil content was set at 4–6% to ensure adequate viscosity reduction and rubber dispersion while avoiding excessive softening point decrease and increased cost at higher contents. Crumb rubber content, the dominant factor influencing rotational viscosity, material cost, and rubber utilization, was divided into low-content (10–20%) and high-content (25–35%) groups. In the preliminary orthogonal arrangement, crumb rubber content was first treated as a single factor with six levels from 10% to 35% at 5% intervals. Range analysis of the test results showed that the range of crumb rubber content was consistently much larger than those of the other factors for all performance indicators, so the influence of the other factors could not be evaluated clearly. For this reason, the low-content and high-content groups were analyzed separately in the segmented orthogonal experimental design, and range analysis was carried out for each group. This approach improves the resolution of the other factors under different crumb rubber dosage ranges. The shear temperature levels of 180 °C, 200 °C, and 220 °C were selected to balance energy consumption with the requirements for rubber swelling and dispersion while preventing asphalt aging. Shear time levels of 60, 90, and 120 min were chosen to ensure sufficient rubber particle breakdown and system homogenization while allowing evaluation of potential performance gains. The selection of reaction time was based on the compatibility between the modifier and asphalt as well as the time cost, and the levels of 30, 60, and 90 min ensured a balance between reaction sufficiency and production efficiency.

Within this segmented orthogonal experimental design, the main effects of the five factors are obtained from the orthogonal arrangement. Explicit interaction terms between factors are not added in order to keep the number of test groups within a reasonable range. In the orthogonal table, each of the first nine groups corresponds to one of the last nine groups with the same levels of the other factors and a different level of crumb rubber content. By comparing the performance differences within these pairs, the combined influence of crumb rubber content and the other factors can be examined, and possible interactions are reflected indirectly in the trends of viscosity, softening point, and rheological indices under different factor combinations. These combined effects are discussed in the Results and Discussion section, rather than being separated as independent interaction factors in the design matrix. The orthogonal experimental design is shown in

Table 5.

The rotational viscosity at 145 °C, penetration, softening point, ductility, and elastic recovery were selected as evaluation indicators. The range analysis was used to determine the sensitivity of each factor to performance indices. This method calculates the mean range of each factor, where a higher range R indicates a stronger influence on the target index. The detailed formulas for R are shown in Equations (1) and (2).

where

is the sum of indicator values for the j-th factor at the i-th level. r is the number of occurrences of the j-th factor at the i-th level.

is the average value of

. R is the range, where a larger R value indicates a greater influence on the evaluation indicator.

In addition to range analysis, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to further evaluate the statistical significance of the preparation factors. For each performance index, the orthogonal experimental results were grouped according to the levels of a given factor, and the between-group and within-group variations were calculated. The ANOVA statistics are shown in Equations (3)–(9).

where

is the value of the response index for the j-th test at the i-th level of a given factor,

is the mean value of the response index at the i-th level, and

is the overall mean value of the response index for all tests. k is the number of levels of the factor,

is the number of tests at the i-th level, and N is the total number of tests.

and

are the between-group and within-group sums of squares, respectively.

and

are the corresponding degrees of freedom,

and

are the between-group and within-group mean squares, respectively, F is the F statistic used to assess the significance of the factor, and p denotes the significance level. A significance level of 0.05 was adopted in this study.

Through segmented range analysis and single-index analysis, the optimal parameter combination for both low- and high-content groups was identified. A weighted scoring method was then used to comprehensively evaluate all test groups and optimized schemes. The weights assigned to each performance indicator were as follows: rotational viscosity 40%, penetration 10%, softening point 30%, ductility 10%, and elastic recovery 10%.

Weight allocation was determined based on engineering requirements, preliminary test results, and performance optimization priorities. Rotational viscosity was assigned the highest weight because high rubber content markedly increases viscosity, limiting processing and construction feasibility. Softening point was given a 30% weight due to the need for enhanced high-temperature resistance in systems without warm mix additives. Preliminary tests showed that penetration, ductility, and elastic recovery all remained within acceptable ranges and exhibited limited sensitivity to further improvement; therefore, each was assigned a weight of 10%.

The optimized preparation process was determined based on performance and cost-effectiveness. The weight scoring equations are presented in Equations (10)–(14). The evaluation ranges were as follows: rotational viscosity 0–6 Pa·s, penetration 40–80 (0.1 mm), softening point 50–70 °C, ductility 10–25 cm, and elastic recovery 70–85%.

Through implementation of these weighted scoring equations and indicator ranges, multidimensional performance indicators can be transformed into a unified quantitative scoring system. This framework clarified optimization direction and boundary limits, emphasized the central importance of viscosity and softening point, and effectively avoided conflicts among single-index optimizations. It provided a scientific and quantifiable basis for integrated analysis of orthogonal experimental results, process optimization, and cost–benefit evaluation.

2.3. Preparation of Warm Mix Rubber Composite-Modified Asphalt

The high-speed shearing was carried out using a laboratory high-speed shear mixer manufactured by Wuxi Petroleum Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd. (Wuxi, China), equipped with a high-speed shear head. A JJ-1 electric stirrer (Haijiangxing Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was used for low-speed mixing. Heating was provided by an electric furnace, and the preparation temperature was controlled using an intelligent temperature controller (ZNHW-II, Shanghai Biaohe Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) throughout the mixing and shearing procedures. Since the power consumption was not recorded during preparation, shear energy was not calculated, and process consistency was ensured by controlling the batch mass, rotor speed, and temperature profile.

The preparation of WAR was based on the optimal parameters determined for AR. The procedure was as follows: 300 g base asphalt was heated in an oven at 160 °C until melted and fluid. The optimal content of aromatic oil was then added and stirred at 160 °C and 600 r/min for 15 min. The temperature was raised to the optimal shear temperature, and the optimal contents of crumb rubber and 2% SBS were added gradually while stirring at 600 r/min for 15 min to complete preliminary mixing. The mixture was then subjected to high-speed shearing at 3000 r/min under the optimal shear temperature for the optimal shear time. Finally, it was allowed to swell and react in an oven at 180 °C to obtain the optimized rubber-modified asphalt.

In this study, UWM was used as the base additive, and based on the viscosity–temperature curve results of preliminary tests, three dosage levels, 4%, 5%, and 6%, were set. To compensate for potential high-temperature performance loss caused by UWM, 1.5% Sasobit was added simultaneously to form a composite modification system. In addition, two control groups were prepared with 5% UWM only and 1.5% Sasobit only to verify the synergistic effect of the composite system. The UWM warm mix additive at the specified concentrations was preheated at 130 °C until molten and added together with 1.5% Sasobit into the AR cooled to 160 °C. The mixture was sheared at 160 °C and 3000 r/min for 30 min to obtain homogeneous WAR. The abbreviations and formulations of each asphalt binder are listed in

Table 6.

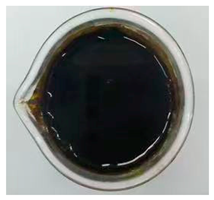

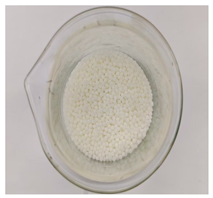

A photograph of the prepared AR and a representative WAR binder is shown in

Figure 1 to illustrate the appearance of the binders after preparation. The WAR binder appears more uniform and visually less viscous than AR, which is consistent with its reduced rotational viscosity.

2.4. Testing Methods

2.4.1. Physical Property Tests

The physical property tests were used to evaluate the physical properties of binders as per JTG E20-2011 [

29], including the rotational viscosity test, the penetration test, the softening point test, the ductility test, and the elastic recovery test. For rotational viscosity, the base asphalt was tested at both 135 °C and 145 °C, whereas the modified binders were measured at 145 °C, which was used as the evaluation index in the orthogonal analysis and in the comparison between AR and WAR.

2.4.2. Rheological Property Tests

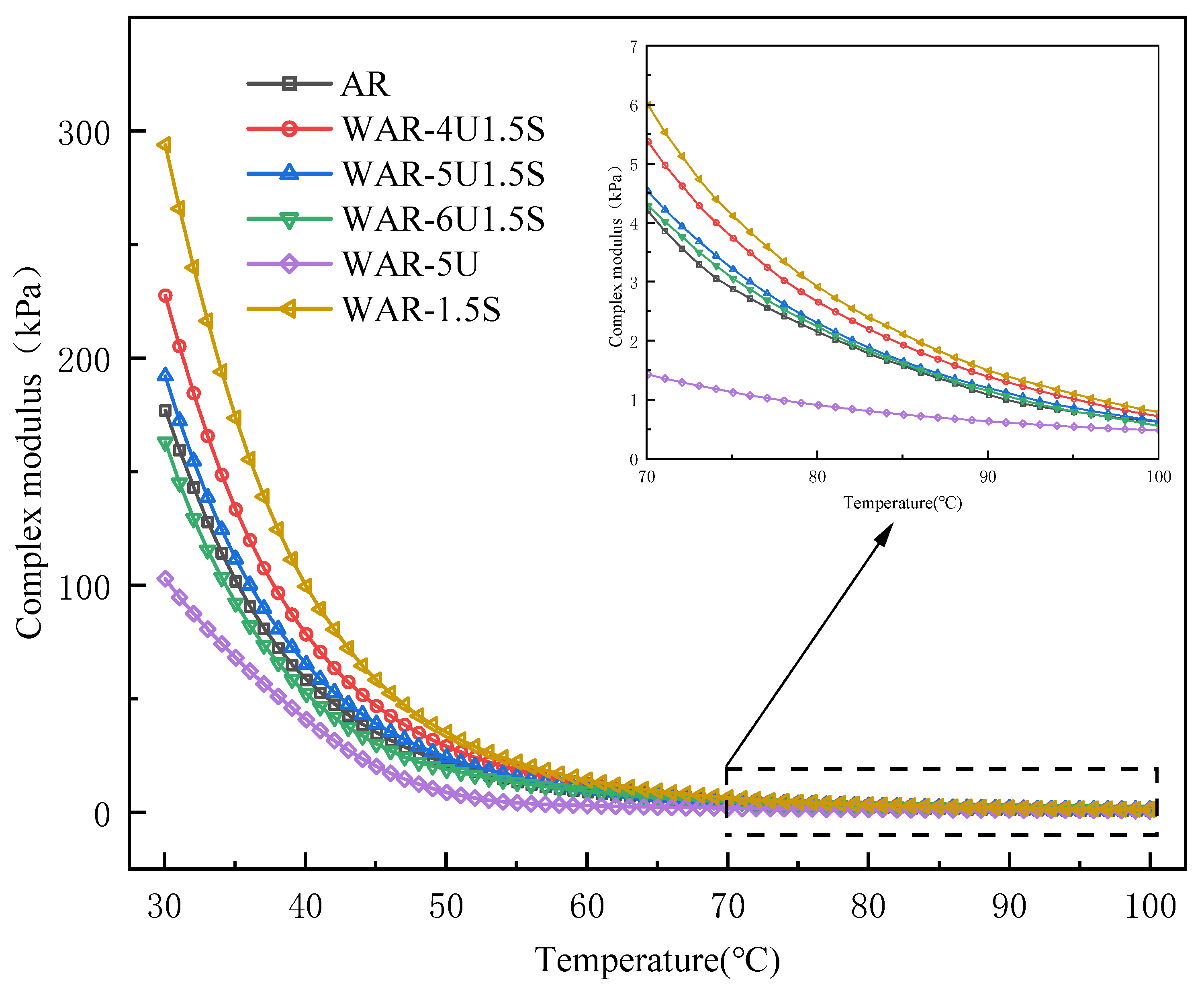

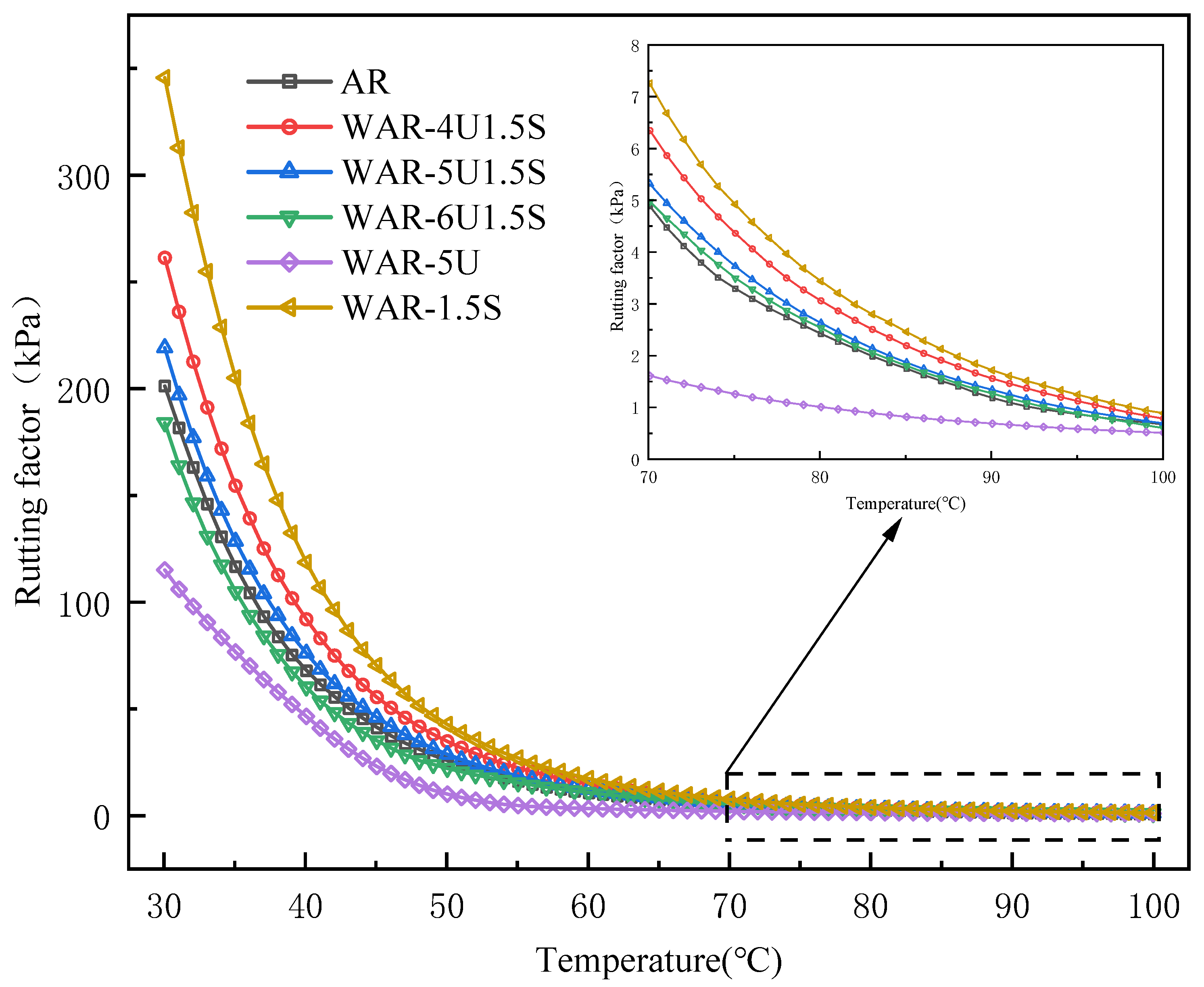

Temperature sweep test was employed using Dynamic Shear Rheometer (DSR) with 25 mm parallel plates (1 mm gap) at a frequency of 1.5 Hz in strain-controlled mode with a constant shear strain amplitude of 1%. The test was taken from 30 °C to 100 °C at a heating rate of 1 °C/min to determine complex modulus , phase angle , and rutting factor . Binder specimens for DSR testing were prepared by pouring hot binder onto the center of the lower plate, then lowering the upper plate to a 1 mm gap. After the gap was stabilized for about 5 min, the excess binder was trimmed so that the edge was flush with the plate. Before each test, the specimen was conditioned at the target temperature for 10 min to reach thermal equilibrium.

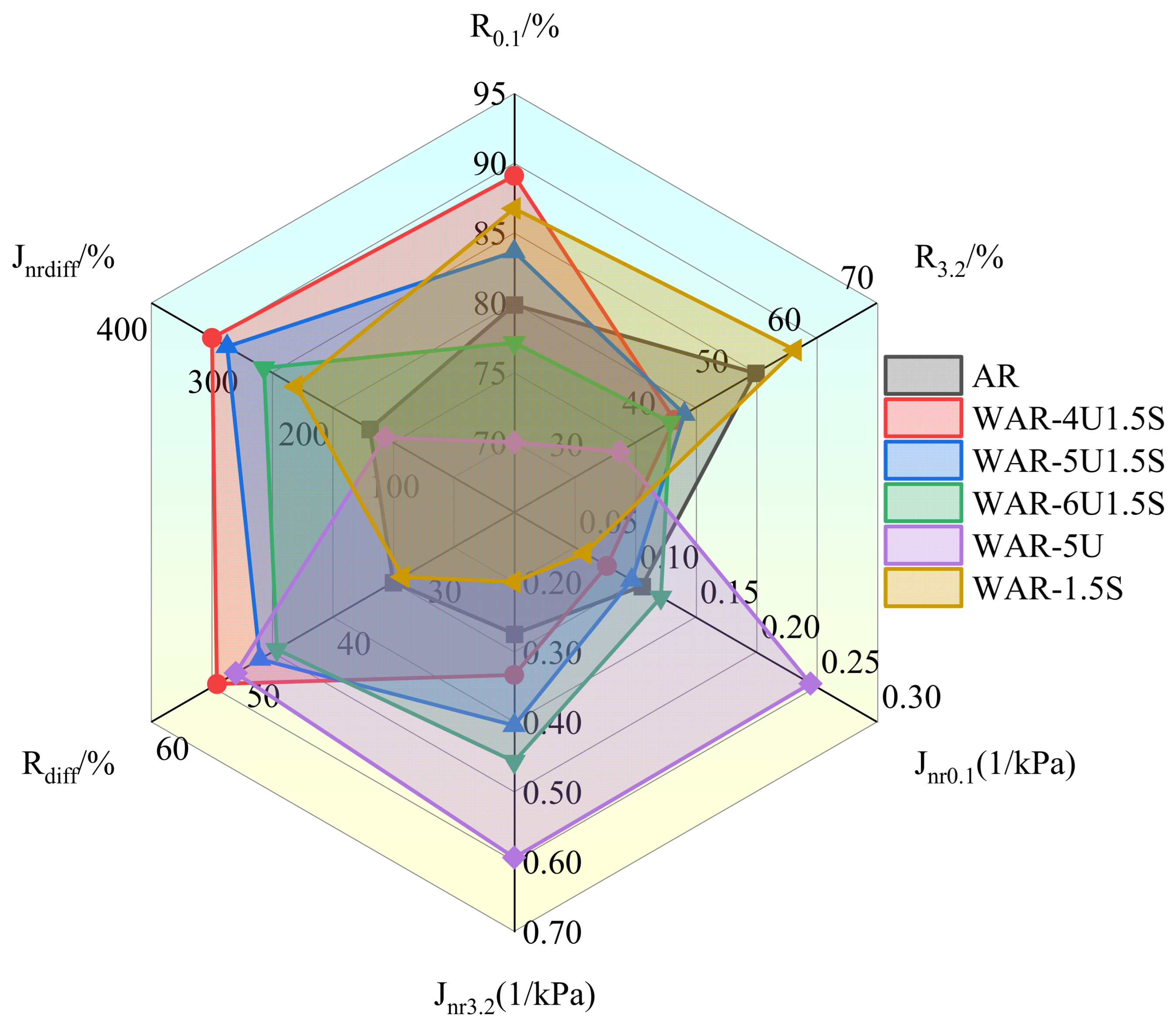

The Multiple Stress Creep Recover (MSCR) test was conducted at 64 °C using 25 mm plates. Ten cycles of stress loading 0.1 kPa and 3.2 kPa were applied, each consisting of 1 s loading and 9 s recovery. The key parameters, percent recovery R, and non-recoverable creep compliance Jnr were calculated. The same plate geometry, specimen preparation procedure, and 1 mm gap as in the temperature sweep test were used, and each specimen was conditioned at 64 °C for 10 min before loading.

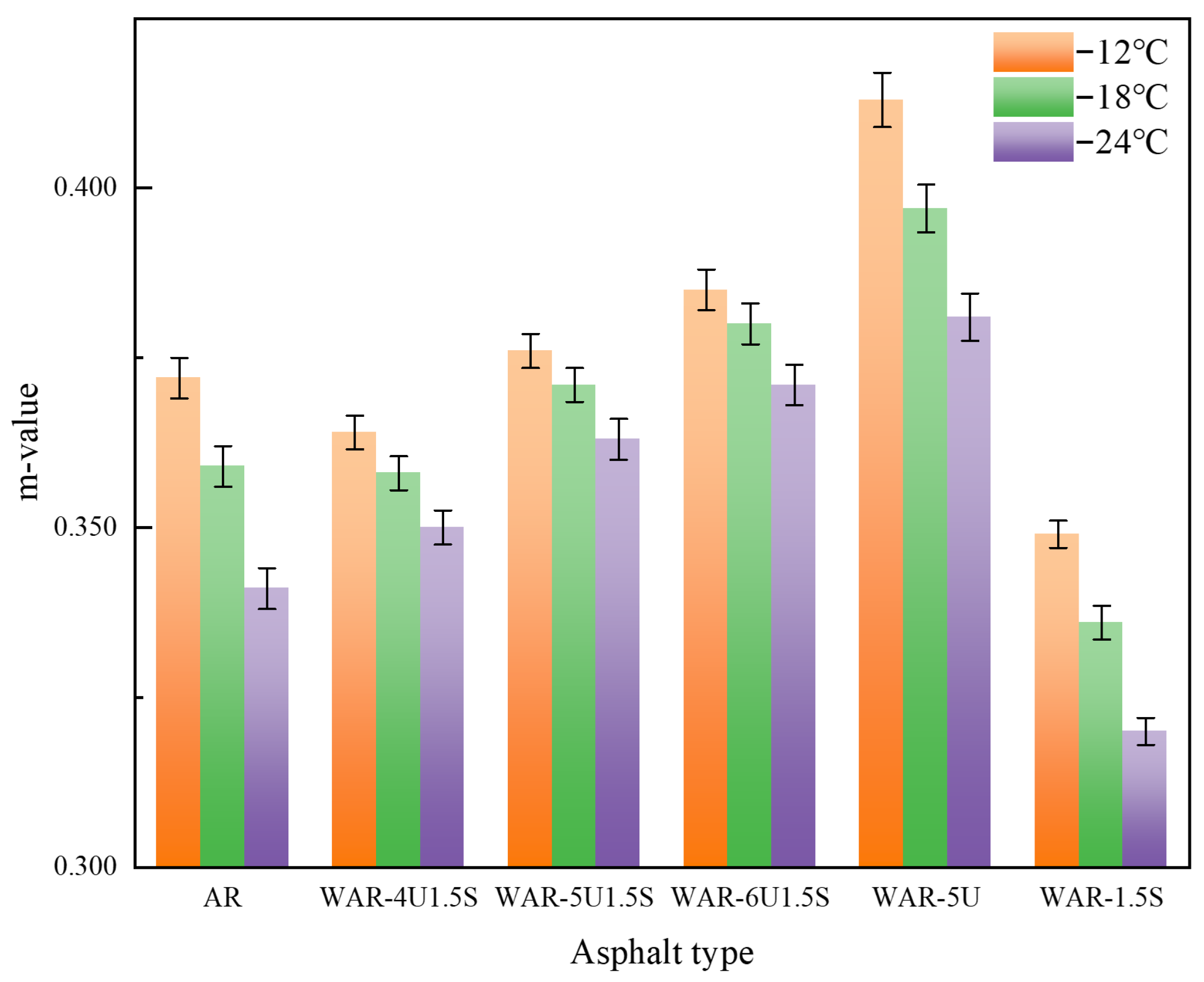

The Bending Beam Rheometer (BBR) test was performed at −12 °C, −18 °C, and −24 °C on asphalt samples. A load of 980 mN was applied for 60 s, and the creep stiffness S and creep rate m-value were recorded. The requirement of S ≤ 300 MPa and m-value ≥ 0.3 at 60 s must be met. BBR specimens were prepared in aluminum beam molds with dimensions of 127 mm × 12.7 mm × 6.35 mm. Before demolding, the molds containing the specimens were cooled at −5 °C for no more than 5 min to avoid deformation. After demolding, the beams were immediately placed in a temperature-controlled bath at the test temperature and conditioned for 60 min before loading.

In summary, the experimental program consists of three main stages. First, AR is produced by the wet process and a segmented OED is used to study the influence of five preparation parameters, aromatic oil content, crumb rubber content, shear temperature, shear time, and reaction time, on the physical properties of AR, including rotational viscosity at 145 °C, penetration, softening point, ductility, and elastic recovery. Second, the optimized AR obtained from the OED is used as the base binder to prepare a series of WAR samples with different warm mix formulations, including the UWM-only binder, the Sasobit only binder, and composite UWM–Sasobit binders with 30% crumb rubber content. Third, these binders are characterized by physical tests and rheological tests including DSR temperature sweep, MSCR, and BBR to determine their high- and low-temperature performance. This framework allows the relationships between preparation parameters, warm mix formulations, and the final properties of the UWM–Sasobit-based WAR and the control binders to be evaluated.