Comparison of the Bond Strength to Titanium of Resin-Based Materials Fabricated by Additive and Subtractive Manufacturing Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

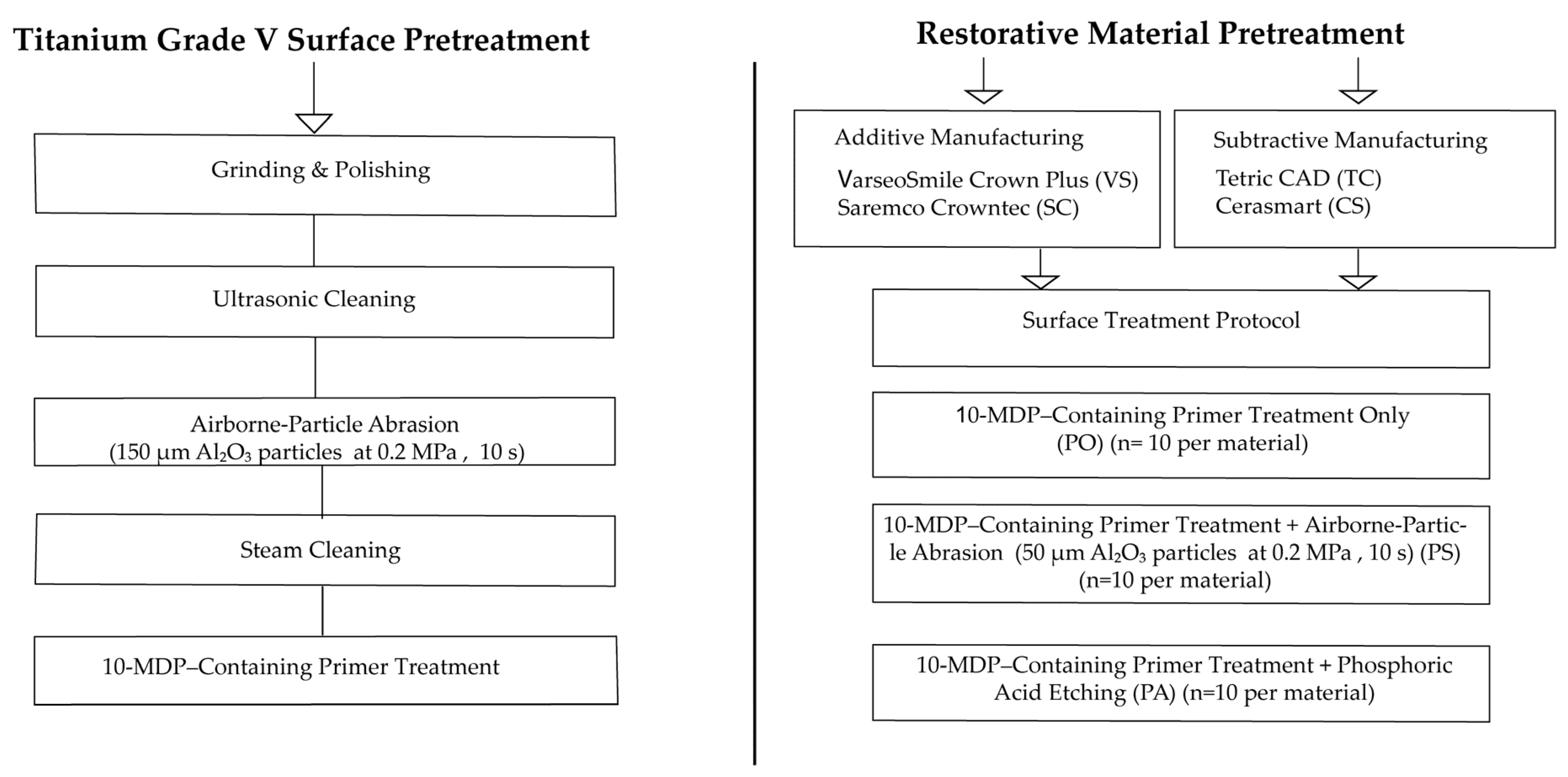

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Normality and Homogeneity of Variance

3.2. Surface Morphology Analysis (SEM Evaluation)

3.3. Shear Bond Strength (SBS) Analysis

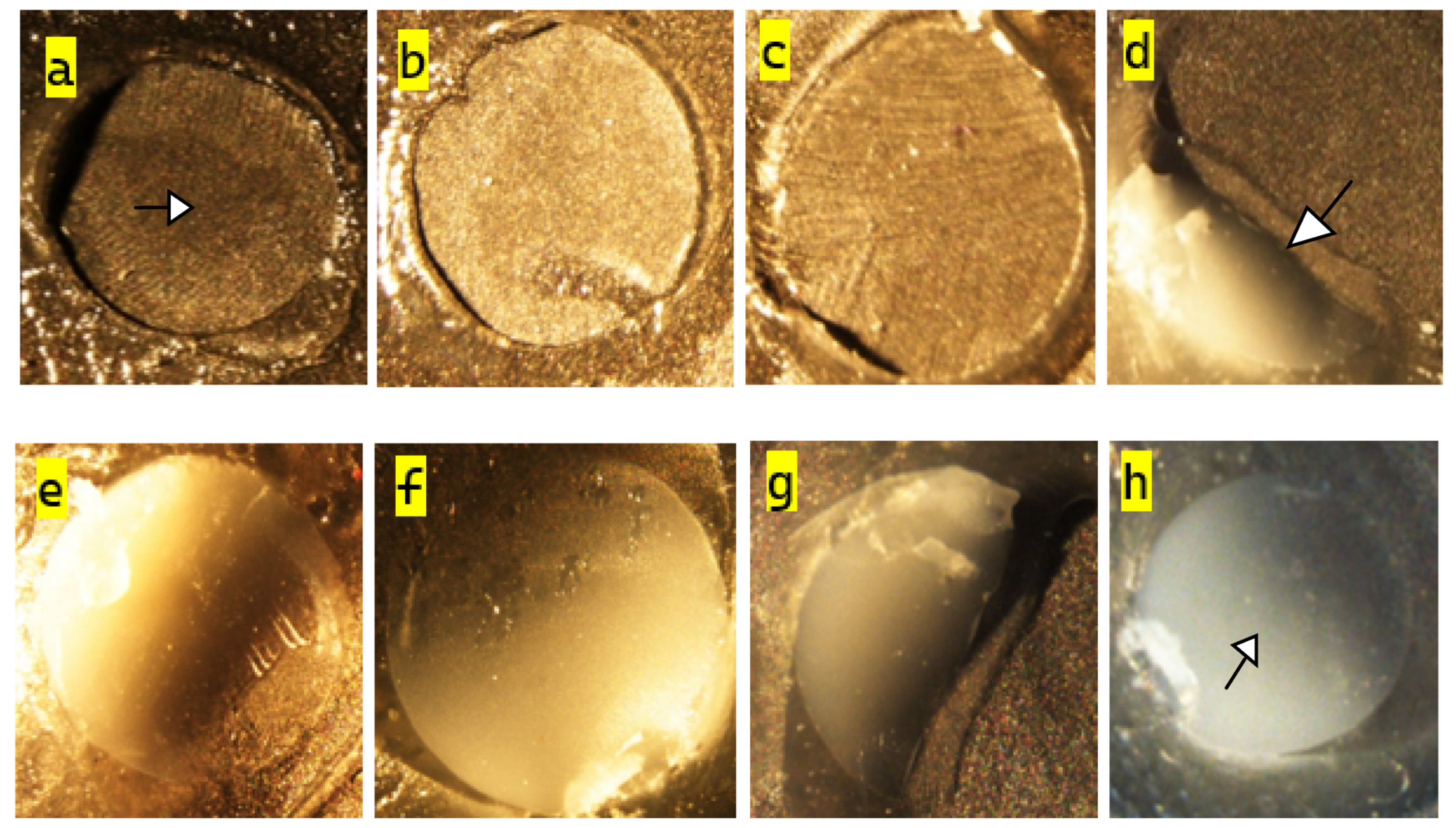

3.4. Failure Mode Distribution

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Surface treatment plays a critical role in bonding performance. Airborne-particle abrasion significantly enhances SBS by increasing surface roughness and promoting micromechanical retention.

- Additively manufactured resin-based CAD/CAM materials tested in the present study showed higher initial bond strength to titanium abutments than the evaluated subtractively manufactured materials, which may be related to their more favorable surface morphology and/or system-specific processing parameters. However, these results are based on 24-h water storage and should not be interpreted as definitive evidence of superior long-term clinical performance, nor should they be generalized to all AM and SM systems.

- Combined mechanical and chemical surface treatments provide better adhesion than chemical treatment alone. The use of 10-MDP–containing universal primers is effective, particularly when preceded by surface roughening, within the short-term conditions tested.

- Each restorative material responds differently to surface treatments, indicating the necessity of material-specific bonding protocols rather than a universal approach.

- Subtractive materials, due to their dense microstructure, may require more aggressive or alternative surface treatments to achieve higher initial bond strength. Further studies, including aging protocols are required before definitive clinical recommendations can be made.

- Failure modes varied according to surface treatment and material, with mechanically treated groups showing more mixed and cohesive failures, suggesting stronger interfacial bonding.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AM | Additive manufacturing |

| SM | Subtractive manufacturing |

| SC | Saremco Crowntec |

| VS | VarseoSmile Crown Plus |

| TC | Tetric CAD |

| CS | Cerasmart |

| PO | Primer only |

| PA | Primer + phosphoric acid etching |

| PS | Primer + airborne-particle abrasion |

| SBS | Shear bond strength |

| PMMA | Polymethyl methacrylate |

| MMA | Methyl methacrylate |

| MDP | 10-Methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate |

| UDMA | Urethane dimethacrylate |

| HEMA | 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate |

| TEGDMA | Triethylene glycol dimethacrylate |

| Bis-GMA | Bisphenol A-glycidyl methacrylate |

| DMA | Dimethacrylate |

References

- Soliman, T.A.; Robaian, A.; Al-Gerny, Y.; Hussein, E.M.R. Influence of surface treatment on repair bond strength of CAD/CAM long-term provisional restorative materials: An in vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alageel, O.; Alhijji, S.; Alsadon, O.; Alsarani, M.; Gomawi, A.A.; Alhotan, A. Trueness, Flexural Strength, and Surface Properties of Various Three-Dimensional (3D) Printed Interim Restorative Materials after Accelerated Aging. Polymers 2023, 15, 3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhaei, M.; Bozorgmehr, N.; Rajati Haghi, H.; Bagheri, H.; Rangrazi, A. The Evaluation of Microshear Bond Strength of Resin Cements to Titanium Using Different Surface Treatment Methods: An In Vitro Study. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacsó, A.B.; Peter, I. A Review of Past Research and Some Future Perspectives Regarding Titanium Alloys in Biomedical Applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.W. Titanium Alloys for Dental Implants: A Review. Prosthesis 2020, 2, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaokutan, I.; Ozel, G.S. Efect of surface treatment and luting agent type on shear bond strength of titanium to ceramic materials. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2022, 14, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wan, K.; Lu, J.; Yuan, C.; Cui, Y.; Duan, R.; Yu, J. Research Progress on Surface Modification of Titanium Implants. Coatings 2025, 15, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amornwichitwech, L.; Palanuwech, M. Shear Bond Strength of Lithium Disilicate Bonded with Various Surface-Treated Titanium. Int. J. Dent. 2022, 2022, 4406703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalóki, M.; Hegedűs, V.; Fodor, T.; Renata, M. Evaluation of the effect of the microscopic glass surface protonation on the hard tissue thin section preparation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagida, H.; Tanoue, N.; Hodate, K.; Muraguchi, K.; Uenodan, A.; Minesaki, Y.; Minami, H. Evaluation of the effects of three pretreatment conditioners and a surface preparation system on the bonding durability of composite resin adhesive to a gold alloy. Dent. Mater. J. 2021, 40, 1388–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özcan, M.; Matinlinna, J. Surface Conditioning Protocol for the Adhesion of Resin-based Cements to Base and Noble Alloys: How to Condition and Why? J. Adhes. Dent. 2015, 17, 372–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, H.; Koizumi, H.; Shimoe, S.; Hirata, I.; Matsumura, H.; Nikawa, H. Effect of thione primers on adhesive bonding between an indirect composite material and Ag-Pd-Cu-Au alloy. Dent. Mater. J. 2014, 33, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, S.; Linke, B.; Torrealba, Y. Effect of MDP-Based primers on the luting agent bond to Y-TZP ceramic and to dentin. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 2438145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egoshi, T.; Taira, Y.; Soeno, K.; Sawase, T. Effects of sandblasting, H2SO4/HCl etching, and phosphate primer application on bond strength of veneering resin composite to commercially pure titanium grade 4. Dent. Mater. J. 2013, 32, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, G.; Yeşil, Z. A new era in provisional restorations: Evaluating marginal accuracy and fracture strength in additive, substractive and conventional techniques. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElMalah, N.S.; Ibrahim, Y.; Mostafa, D. Evaluation of 3D printed nano-modified resin shear bond strength on titanium surfaces (an in-vitro study). BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükekenci, A.S.; Dönmez, M.B.; Dede, D.Ö.; Çakmak, G.; Yilmaz, B. Bond strength of recently introduced computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing resin-based crown materials to polyetheretherketone and titanium. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 132, 1066.e1–1066.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lankes, V.; Reymus, M.; Mayinger, F.; Coldea, A.; Liebermann, A.; Hoffmann, M.; Stawarczyk, B. Three-Dimensional Printed Resin: Impact of Different Cleaning Protocols on Degree of Conversion and Tensile Bond Strength to a Composite Resin Using Various Adhesive Systems. Materials 2023, 16, 3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/TR 11405:2015; Dental Materials—Testing of Adhesion to Tooth Structure. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Wiedenmann, F.; Klören, M.; Edelhoff, D.; Stawarczyk, B. Bond Strength of CAD-CAM and Conventional Veneering Materials to Different Frameworks. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 125, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.S.; Goldstein, G.; Choi, M.; Bromage, T.G. In Vitro Shear Bond Strength of 2 Resin Cements to Zirconia and Lithium Disilicate: An in Vitro Study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 125, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Gallo, S.; Padovan, S.; Chiesa, M.; Poggio, C.; Scribante, A. Influence of different surface pretreatments on shear bond strength of an adhesive resin cement to various zirconia ceramics. Materials 2020, 13, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 10477:2020; Dentistry—Polymer-Based Crown and Bridge Materials. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Jain, S.; Sayed, M.E.; Shetty, M.; Alqahtani, S.M.; Al Wadei, M.H.D.; Gupta, S.G.; Othman, A.A.A.; Alshehri, A.H.; Alqarni, H.; Mobarki, A.H.; et al. Physical and Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Provisional Crowns and Fixed Dental Prosthesis Resins Compared to CAD/CAM Milled and Conventional Provisional Resins: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Polymers 2022, 14, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Schmidt, F.; Beuer, F.; Yassine, J.; Hey, J.; Prause, E. Effect of surface treatment strategies on bond strength of additively and subtractively manufactured hybrid materials for permanent crowns. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.J.; Park, Y.; Shin, Y.; Kim, J.H. Effect of Adhesion Conditions on the Shear Bond Strength of 3D Printing Resins after Thermocycling Used for Definitive Prosthesis. Polymers 2023, 15, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, A.S.; Tulbah, H.I.; Binhasan, M.; Abbasi, M.S.; Ahmed, N.; Shabib, S.; Farooq, I.; Aldahian, N.; Nisar, S.S.; Tanveer, S.A.; et al. Surface properties of polymer resins fabricated with subtractive and additive manufacturing techniques. Polymers 2021, 13, 4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamo, E.T.; Zahoui, A.; Ikejiri, L.L.; Marun, M.; da Silva, K.P.; Coelho, P.G.; Soares, S.; Bonfante, E.A. Retention of zirconia crowns to ti-base abutments: Effect of luting protocol, abutment treatment and autoclave sterilization. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2021, 65, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitznagel, F.A.; Horvath, S.D.; Guess, P.C.; Blatz, M.B. Resin bond to indirect composite and new ceramic/polymer materials: A review of the literature. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2014, 26, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, T.; Preis, V.; Behr, M.; Rosentritt, M. Roughness, surface energy, and superficial damage of CAD/CAM materials after surface treatment. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 2787–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Yabuki, C.; Kurokawa, H.; Takamizawa, T.; Kasahara, Y.; Saegusa, M.; Suzuki, M.; Miyazaki, M. Influence of surface treatment on bonding of resin luting cement to CAD/CAM composite blocks. Dent. Mater. J. 2020, 39, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongsue, S.; Thanatvarakorn, O.; Prasansuttiporn, T.; Nimmanpipug, P.; Sastraruji, T.; Hosaka, K.; Foxton, R.M.; Nakajima, M. Effect of surface topography and wettability on shear bond strength of Y-TZP ceramic. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Wolfart, S.; Scharnberg, M.; Ludwig, K.; Adelung, R.; Kern, M. Influence of contamination on zirconia ceramic bonding. J. Dent. Res. 2007, 86, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takesue Yano, H.; Ikeda, H.; Nagamatsu, Y.; Masaki, C.; Hosokawa, R.; Shimizu, H. Effects of alumina airborne-particle abrasion on the surface properties of cad/cam composites and bond strength to resin cement. Dent. Mater. J. 2021, 40, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motevasselian, F.; Amiri, Z.; Chiniforush, N.; Mirzaei, M.; Thompson, V. In vitro evaluation of the effect of different surface treatments of a hybrid ceramic on the microtensile bond strength to a luting resin cement. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 10, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Gamal, A.; Medioni, E.; Rocca, J.P.; Fornaini, C.; Muhammad, O.H.; Brulat-Bouchard, N. Shear bond, wettability and AFM evaluations on CO2 laser-irradiated CAD/CAM ceramic surfaces. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, K.; Nagaoka, N.; Maruo, Y.; Nishigawa, G.; Irie, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Van Meerbeek, B. Sandblasting may damage the surface of composite CAD-CAM blocks. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dederichs, M.; Badr, Z.; Viebranz, S.; Nietzsche, S.; Schulze-Späte, U.; Schmelzer, A.S.; Lehmann, T.; Guentsch, A. Effect of surface conditioning on the adhesive bond strength of 3D-printed resins used in permanent fixed dental prostheses. J. Dent. 2025, 155, 105621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Chen, H.; Jiang, X. Micromechanical interlocking structure at the filler/resin interface for dental composites: A review. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, L.M.; Ferraz, L.G.; Antunes, K.B.; Garcia, I.M.; Schneider, L.F.J.; Collares, F.M. Silane content influences physicochemical properties in nanostructured model composites. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37, e85–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Chi, C.W.; Lee, C.Y.; Tsai, Y.L.; Kasimayan, U.; Mahesh, K.P.O.; Lin, H.P.; Chiang, Y.C. Effects of surface treatments of bioactive tricalcium silicate-based restorative material on the bond strength to resin composite. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barutcigil, K.; Barutcigil, Ç.; Kul, E.; Özarslan, M.M.; Buyukkaplan, U.S. Effect of Different Surface Treatments on Bond Strength of Resin Cement to a CAD/CAM Restorative Material. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, G.A.; Sophr, A.M.; de Goes, M.F.; Sobrinho, L.C.; Chan, D.C. Effect of etching and airborne particle abrasion on the microstructure of different dental ceramics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2003, 89, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, M.; Allahbeickaraghi, A.; Dündar, M. Possible hazardous effects of hydrofluoric acid and recommendations for treatment approach: A review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2012, 16, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishizawa, Y.; Komagata, Y.; Nagamatsu, Y.; Kawamoto, T.; Ikeda, H. Chemical etching of CAD-CAM glass-ceramic-based materials using fluoride solutions for bonding pretreatment. Dent. Mater. J. 2024, 43, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, E.J., Jr.; Brodeur, C.; Cvitko, E.; Pires, J.A. Treatment of composite surfaces for indirect bonding. Dent. Mater. 1992, 8, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, İ.; Karaman, E. How the repair bonding strength of hybrid ceramic CAD/CAM blocks is influenced by the use of surface treatments and universal adhesives. Dent. Mater. J. 2024, 43, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Choi, Y.S. Microtensile bond strength and micromorphologic analysis of surface-treated resin nanoceramics. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2016, 8, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komagata, Y.; Ikeda, H.; Yano, H.T.; Nagamatsu, Y.; Masaki, C.; Hosokawa, R.; Shimizu, H. Influence of the thickening agent contained in a phosphoric acid etchant on bonding between feldspar porcelain and resin cement with a silane coupling agent. Dent. Mater. J. 2023, 42, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donmez, M.B.; Çakmak, G.; Yılmaz, D.; Schimmel, M.; Abou-Ayash, S.; Yilmaz, B.; Peutzfeldt, A. Bond strength of additively manufactured composite resins to dentin and titanium when bonded with dual-polymerizing resin cements. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 132, 1067.e1–1067.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Material | Material Type | Composition | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dentium Superline Pre-Milled Abutment | Titanium | Grade V Titanium;Ti-6AL-4V | Dentium, Seoul, Republic of Korea |

| Crowntec | 3D-printed permanent composite resin material | 4,4-isopropylphenol, ethoxylated and esterified with 2-methylprop-2-enoic acid, silanized dental glass, pyrogenic silica (SiO2), initiators. Total inorganic filler content: 30–50% (by weight) | Saremco Dental AG, Rebstein, Switzerland |

| VarseoSmile Crown Plus | 3D-printed permanent hybrid composite resin material | Esterification products of 4,4-isopropylphenol, ethoxylated and 2-methylprop-2-enoic acid, silanized dental glass, methyl benzoylformate, diphenyl (2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide. Total inorganic filler content: 30–50% (by weight) | BEGO, Bremen, Germany |

| Tetric CAD | Composite Resin Material | Cross-linked dimethacrylate matrix containing 80% (by weight) nanoparticles | Ivoclar-Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein |

| Cerasmart | Nano-ceramic resin composite material | UDMA, Bis-MEPP, dimethacrylate, 71% (by weight) silica (40 nm), barium-silica nanoparticles | GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan |

| G-CEM LinkForce | Dual-cure adhesive resin cement | Resin-based composite cement: A: Bis-GMA, UDMA, DMA, barium silica, initiator, pigment B: Bis-MEPP, UDMA, DMA, barium silica, initiator | GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan |

| Monobond Plus | Universal Primer | Ethanol, 3-trimethoxysilylpropyl methacrylate (silane), methacrylated phosphoric acid ester (10-MDP), and disulfide acrylate | Ivoclar-Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein |

| DeTrey Conditioner 36 | Phosphoric Acid | Phosphoric acid, highly dispersed silicon dioxide, detergent, pigment, water | Dentsply Sirona, Charlotte, NC, USA |

| Substrate | Abrasive | Particle Size (µm) | Pressure (MPa) | Distance (mm) | Duration (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Titanium abutment (Grade V) | Aluminum oxide (Al2O3) | 150 | 0.2 | 10 | 10 |

| Restorative Materials | Aluminum oxide (Al2O3) | 50 | 0.2 | 10 | 10 |

| Group | Shapiro-Wilk Statistics | df | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|

| TC_PO | 0.908 | 10 | 0.270 |

| TC_PS | 0.981 | 10 | 0.971 |

| TC_PA | 0.909 | 10 | 0.273 |

| SC_PO | 0.940 | 10 | 0.555 |

| SC_PS | 0.896 | 10 | 0.197 |

| SC_PA | 0.897 | 10 | 0.203 |

| CS_PO | 0.952 | 10 | 0.690 |

| CS_PS | 0.918 | 10 | 0.340 |

| CS_PA | 0.942 | 10 | 0.581 |

| VS_PO | 0.913 | 10 | 0.306 |

| VS_PS | 0.919 | 10 | 0.346 |

| VS_PA | 0.874 | 10 | 0.110 |

| F | df1 | df2 | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.780 | 11 | 108 | 0.000 * |

| Type III Sum of Squares | df | F | p | Partial Eta Squared | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material Type | 738.080 | 3 | 6042.079 | 0.000 * | 0.994 |

| Surface Treatment | 258.633 | 2 | 3175.832 | 0.000 * | 0.983 |

| Material Type & Surface Treatment | 103.567 | 6 | 423.911 | 0.000 * | 0.959 |

| Error | 4.398 | 108 | |||

| Total | 18,581.537 | 120 | |||

| Corrected Total | 1104.677 | 119 |

| PO | PS | PA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material | Mean ± Standard Deviation (95%CI) (MPa) | Mean ± Standard Deviation (95%CI) (MPa) | Mean ± Standard Deviation (95%CI) (MPa) |

| TC | 8.29 (±0.24) A (8.13–8.49) | 13.80 (±0.30) G (13.57–14.03) | 10.20 (±0.18) D (10.07–10.34) |

| SC | 12.38 (±0.38) E (12.10–12.67) | 18.48 (±0.13) I (18.38–18.58) | 15.05 (±0.07) H (15.01–15.11) |

| CS | 8.07 (±0.17) A (7.94–8.20) | 9.37 (±0.01) C (9.36–9.38) | 8.96 (±0.09) B (8.89–9.03) |

| VS | 12.72(±0.13) E (12.61–12.81) | 14.15 (±0.17) G (14.02–14.28) | 13.31 (±0.20) F (13.16–13.46) |

| Total | 10.36 (±2.23) (9.65–11.07) | 13.95 (±3.26) (12.91–14.99) | 11.88 (±2.45) (11.10–12.66) |

| Material Type | PO | PS | PA | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adh | Coh | Mix | Adh | Coh | Mix | Adh | Coh | Mix | Adh | Coh | Mix | |

| TC | 10 (%100) | 0 (%0) | 0 (%0) | 8 (%80) | 0 (%0) | 2 (%20) | 9 (%90) | 0 (%0) | 1 (%10) | 27 (%90) | 0 (%0) | 3 (%10) |

| SC | 7 (%70) | 0 (%0) | 3 (%30) | 4 (%40) | 1 (%10) | 5 (%50) | 7 (%70) | 0 (%0) | 3 (%30) | 18 (%60) | 1 (%3) | 11 (%37) |

| CS | 10 (%100) | 0 (%0) | 0 (%0) | 9 (%90) | 0 (%0) | 1 (%10) | 10 (%100) | 0 (%0) | 0 (%0) | 29 (%97) | 0 (%0) | 1 (%3) |

| VS | 7 (%70) | 0 (%0) | 3 (%30) | 2 (%20) | 2 (%20) | 6 (%60) | 4 (%40) | 1 (%10) | 5 (%50) | 13 (%43) | 3 (%10) | 14 (%47) |

| Total | 34 (%85) | 0 (%0) | 6 (%15) | 23 (%58) | 3 (%7) | 14 (%35) | 30 (%75) | 1 (%2) | 9 (%23) | 107 (%76) | 4 (%4) | 29 (%20) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yavşan, A.; Türken, R. Comparison of the Bond Strength to Titanium of Resin-Based Materials Fabricated by Additive and Subtractive Manufacturing Methods. Polymers 2026, 18, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010056

Yavşan A, Türken R. Comparison of the Bond Strength to Titanium of Resin-Based Materials Fabricated by Additive and Subtractive Manufacturing Methods. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleYavşan, Asiye, and Recep Türken. 2026. "Comparison of the Bond Strength to Titanium of Resin-Based Materials Fabricated by Additive and Subtractive Manufacturing Methods" Polymers 18, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010056

APA StyleYavşan, A., & Türken, R. (2026). Comparison of the Bond Strength to Titanium of Resin-Based Materials Fabricated by Additive and Subtractive Manufacturing Methods. Polymers, 18(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010056