1. Introduction

The increased demand for durable, cost-effective, and sustainable pavement materials has intensified interest in incorporating RAP into both hot-mix and WMA technologies. RAP, however, contains aged binder that has undergone oxidative hardening, polymer degradation, and volatilization, resulting in significantly higher stiffness and reduced ductility compared with virgin asphalt [

1]. Although RAP offers substantial environmental and economic benefits, high RAP contents often reduce mixture flexibility and increase cracking risk. This issue becomes more severe when the original pavement used polymer-modified binders (PMBs), where aging induces SBS chain scission and loss of elastic recovery, producing highly stiff, low-recovery RAP binders that are difficult to reintegrate without additional modification.

WMA technologies have further encouraged RAP utilization by lowering production temperatures and reducing thermal aging [

2]. Yet integrating high RAP contents into WMA remains challenging: reduced temperatures limit binder mobilization, slow blending between virgin and aged binder phases, and may increase moisture susceptibility. Rejuvenators have thus become essential for RAP-rich WMA systems. REOW has gained attention due to its high content of light hydrocarbon fractions that reduce asphaltene agglomeration and improve binder fluidity; however, it does not supply resin components and therefore cannot fully substitute for the complete maltene system. Instead, REOW functions by partially restoring the colloidal balance of aged binders through plasticization rather than full maltene replenishment.

Recently, waste engine oil has also been increasingly explored as a secondary raw material for bituminous binders due to its high content of light maltene-like fractions, which compensate for the loss of aromatics during aging and help restore the colloidal balance of hardened binders [

3]. Korchak et al. [

4] demonstrated that used mineral motor oils can be effectively regenerated through an integrated thermo-oxidative treatment, vacuum distillation, and urea purification process, producing regenerated oils and residues suitable for bitumen-related applications. This provides a technical basis for considering regenerated waste engine oils as plasticizing or rejuvenating agents in asphalt binder modification [

5]. In parallel, modern bitumen modification relies on several additive groups: thermoplastic polymers (e.g., LDPE [

6], EVA [

7]), thermoelastoplastics such as SBS that form elastic networks [

8], plasticizers that improve workability, adhesion promoters that enhance aggregate–binder bonding, and secondary raw materials that partially substitute fresh bitumen. Within this classification, REOW functions primarily as a rejuvenator/plasticizing secondary raw material, whereas SBS is a thermoelastoplastic modifier that increases elasticity and high-temperature performance.

Polymer modifiers such as SBS are widely used to rebuild elasticity and improve high-temperature performance. Recent studies have explored warm-mix technologies with rubber or polymer additives (Hu et al. [

9]; Yu et al. [

10]), multi-scale adhesion mechanisms in recycled SBS binders (Li et al. [

11]), rubber and fiber reinforcement (Jin et al. [

12]), and polymer-modified mixture performance (Alsolieman et al. [

13]; Safaeldeen et al. [

14]). Parallel research has investigated rejuvenation strategies using REOW/REOB-type oils (Porto et al. [

15]; Li et al. [

16]; Shi et al. [

17]) and the combined use of oil-based rejuvenators with polymers (Li et al. [

18]). RAP-oriented mixture studies (Hoy et al. [

19]; Lee and Le [

20]; Lee et al. [

21]) and comprehensive reviews on RAP blending behavior (Xing et al. [

22]) further highlight the complexities associated with recycled PMB binders.

Another important knowledge gap concerns the translation of binder-level improvements to mixture-level behavior, particularly for high-RAP warm-mix asphalt produced from polymer-modified pavements. Although rejuvenators can reduce stiffness and polymers such as SBS can enhance elasticity at the binder scale, their combined effects on mixture rutting, raveling, moisture damage, and cracking are not always straightforward. Field-aged polymer-modified binders commonly exhibit oxidation-induced hardening and degradation of the SBS network, making re-modification with SBS alone insufficient to restore viscoelastic balance. In such systems, a plasticizing component is required to re-mobilize the aged binder phase prior to effective polymer reinforcement.

High RAP contents further introduce complexities related to aggregate structure, binder film thickness, and moisture susceptibility under warm-mix asphalt conditions. Comprehensive multi-scale studies linking binder rheology (viscosity, master curves, MSCR recovery), aging behavior (RTFO, PAV), and mixture performance (ITS/TSR, Cantabro, Hamburg wheel tracking, Overlay Test, and SCB fracture energy) remain scarce, particularly for RAP derived from aged polymer-modified pavements. Against this background, this study proposes a hybrid REOW–SBS modification strategy and provides a systematic multi-scale evaluation of its effectiveness in restoring binder functionality and improving mixture performance, thereby addressing both scientific and practical challenges associated with high-RAP warm-mix asphalt.

Therefore, the objective of this study is to investigate the feasibility of combining REOW and SBS polymer to rehabilitate a field-aged RAP binder and to evaluate the resulting binder- and mixture-level performance of warm-mix asphalt containing 30 wt.% RAP at the mixture scale. In this manuscript, the term bitumen refers exclusively to the asphalt binder material, while asphalt concrete denotes the composite mixture of binder and mineral aggregates; these terms are used consistently to avoid ambiguity. To achieve this objective, the RAP binder was first extracted and recovered from reclaimed wearing-course materials and used for binder-level characterization and controlled blending studies. The recovered RAP binder was blended with virgin 60/70 binder to prepare base binders, which were then modified using recycled engine oil waste (3 wt.%) and SBS polymer (1–4 wt.%) to examine rejuvenation and polymer-reinforcement mechanisms under controlled binder conditions. Subsequently, warm-mix asphalt concretes incorporating 30 wt.% RAP aggregate were produced. The RAP asphalt content measured from extraction was used to determine the binder contribution from RAP, while virgin binder (modified according to the selected binder formulation) was added by difference to achieve a fixed total binder content. Mixture performance was evaluated through ITS/TSR, Cantabro loss, Hamburg wheel tracking, Overlay Test fatigue response, and SCB fracture energy. This integrated framework enables direct linkage between binder rheological behavior and asphalt concrete performance, providing insight into the feasibility of REOW–SBS hybrid modification for RAP-rich warm-mix asphalt systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Binder

Two types of bitumen were used in this study: a conventional 60/70 penetration-grade virgin binder and a polymer-modified RAP binder recovered from reclaimed asphalt pavement. The virgin 60/70 binder is a standard paving grade commonly used in Vietnamese dense-graded asphalt mixtures, with a penetration of 60–70 dmm, a softening point of approximately 46–50 °C, and a rotational viscosity of about 350–450 mPa·s at 135 °C.

In addition to the raw materials, a “Control Binder” (denoted as B0) was established to serve as the reference baseline. This binder was produced by blending 70 wt.% virgin 60/70 bitumen with 30 wt.% recovered RAP binder, simulating the combined binder phase of the reference warm-mix asphalt mixture prior to the addition of any rejuvenators or polymer modifiers. Its physical and rheological properties were characterized and are listed in

Table 1 alongside the base components.

In this study, the RAP binder was first extracted and recovered from reclaimed wearing-course materials in accordance with ASTM D2172 [

23] and ASTM D5404 [

24] to enable binder-level testing and controlled binder blending investigations. The reclaimed pavement originated from an expressway surface layer and was originally constructed using a polymer-modified binder (PMB). The extraction process provided the RAP asphalt content (≈5.3 wt.%), which served as a key input for both the binder study and the subsequent mixture design. The general work flow is presented in

Figure 1.

At the binder scale, the recovered RAP binder was blended with virgin 60/70 binder to prepare representative base binders for rheological evaluation and modification studies. REOW and SBS polymer were incorporated into these blended binders to investigate rejuvenation and polymer reinforcement mechanisms under controlled binder conditions (

Section 3.1).

Following the binder-level investigation, the study proceeded to mixture-level validation. RAP was incorporated into warm-mix asphalt mixtures at 30 wt.% of total aggregate mass. Based on the measured RAP asphalt content, the RAP binder contribution to the mixture was calculated (≈1.6 wt.% of mixture mass). The total binder content was fixed at 5.0 wt.%, and virgin binder—modified according to the selected binder formulations—was added by difference to achieve the target binder content. Thus, binder proportions in the mixtures were determined by RAP asphalt content and volumetric mix design, rather than by predefined binder blending ratios.

To assess the suitability of the virgin binder and the recovered RAP binder for asphalt mixture production, their fundamental physical and rheological properties were first characterized and compared against typical requirements for paving-grade bitumen. This preliminary evaluation is intended to establish whether each material can be used directly as a binder or requires further treatment.

Table 1 summarizes the penetration, softening point, ductility, viscosity, and key rheological parameters of the virgin 60/70 bitumen and the recovered polymer-modified binder from RAP, providing a basis for evaluating aging susceptibility and standalone binder usability prior to modification. Virgin paving-grade 60/70 binder meeting TCVN 7493 [

25]/ASTM D946 [

26] is intended for direct use in HMA production; recovered RAP binder generally requires blending/rejuvenation to meet paving-grade or performance specifications.

Table 1.

General properties of virgin binder and recovered RAP binder.

Table 1.

General properties of virgin binder and recovered RAP binder.

| Property | Typical Requirement | Virgin 60/70 Bitumen in This Research | Current RAP Bitumen (Recovered PMB) | Control Binder (B0) | Assessment | Test Method |

|---|

| Penetration (25 °C, 100 g, 5 s) | 60–70 dmm | 65 dmm | 20 dmm | 41 dmm | RAP binder far outside acceptable range | ASTM D5 [27] |

| Softening point (Ring and Ball) | ≥46 °C | 48 °C | 65 °C | 58.5 °C | RAP binder excessively hardened | ASTM D36 [28] |

| Ductility (25 °C) | ≥75–80 cm | >80 cm | 8 cm | - | Severe embrittlement of RAP binder | ASTM D113 [29] |

| Rotational viscosity (135 °C) | ≤3.0 Pa·s | 0.42 Pa·s | 1.75 Pa·s | 0.685 Pa·s | Poor workability of RAP binder | ASTM D4402 [30] |

| G*/sinδ (64 °C, unaged) | ≤2.2 kPa (Superpave guideline) | 1.2 kPa | 8.0 kPa | 4.8 kPa | RAP binder overly stiff | ASTM D7175 [31] |

| MSCR Jnr3.2 (64 °C, unaged) | ≤2.0 kPa−1 (traffic dependent) | 2.3 kPa−1 | 0.6 kPa−1 | 1.34 kPa−1 | Limited stress relaxation | ASTM D7405 [32] |

| Standalone binder usability | Required | Suitable | Not suitable without rejuvenation | | - | |

2.1.2. Aggregate Mix

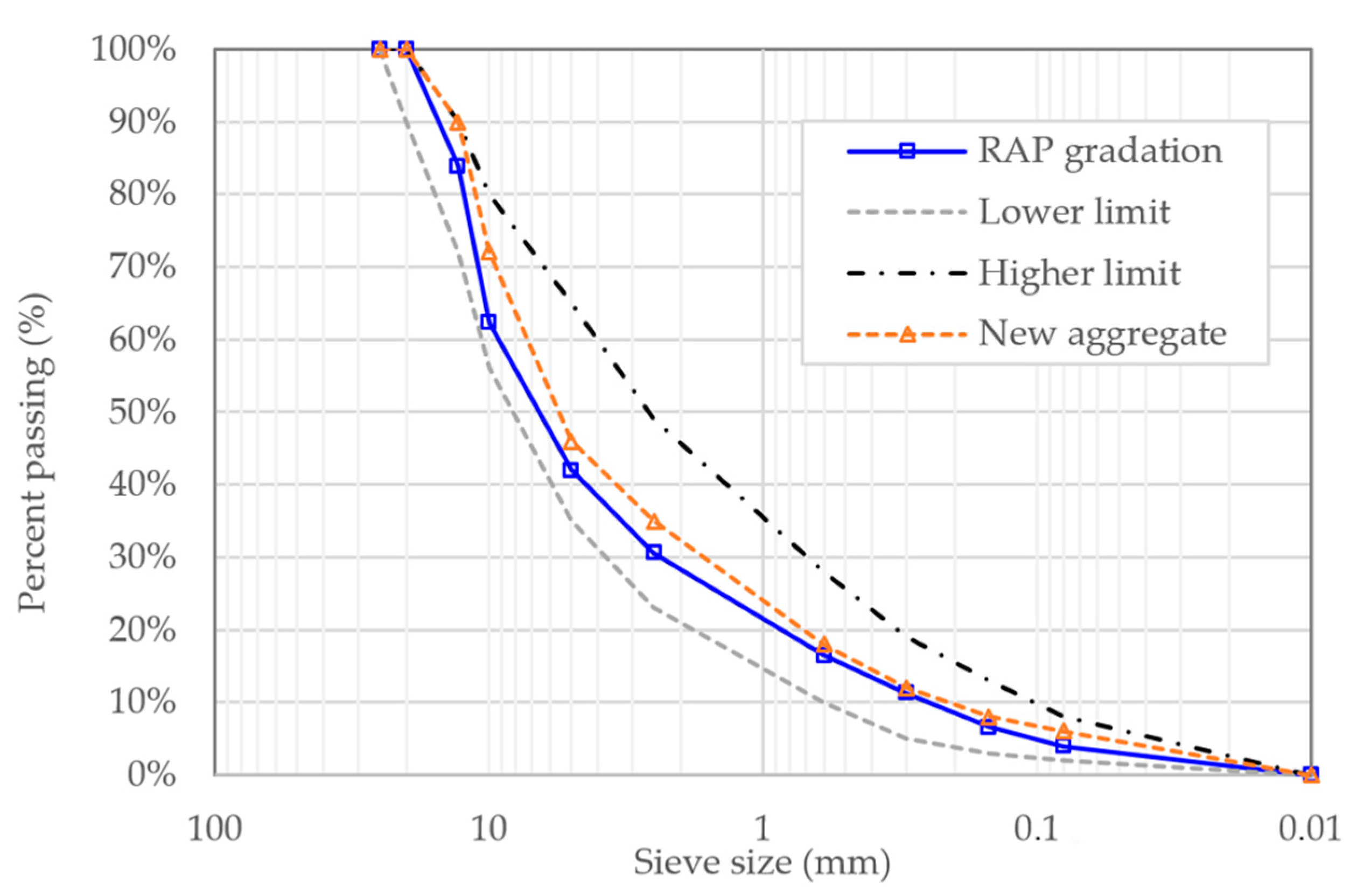

Crushed basalt aggregates sourced from a local quarry in southern Vietnam were used for all mixture preparations. Basalt is the predominant aggregate type employed in dense-graded wearing courses due to its high angularity, excellent interlock potential, and superior mechanical strength compared with sedimentary aggregates. The aggregates were oven-dried and separated into individual size fractions (19 mm, 13.2 mm, 9.5 mm, 4.75 mm, 2.36 mm, 0.425 mm, and filler) according to ASTM C136 [

33] to prepare the specified 13 mm NMAS dense-graded gradation.

Key physical properties of the coarse and fine aggregates used in this study are summarized in

Table 2. Aggregates consisted of crushed granite and natural sand blends commonly used in WMA–RAP applications.

Aggregate absorption was measured following ASTM C127 [

34] and C128 [

35], yielding values of 0.9–1.1% for coarse aggregates and 1.2–1.4% for fine aggregates. These absorption characteristics were incorporated into binder content calculations to ensure accurate volumetric control. The selected aggregates provided a high-quality skeleton structure necessary for the evaluation of binder modification effects in mixtures containing 30% RAP. The sieve size of aggregate used in this research is presented in

Figure 2 while general physical properties of the aggregates are presented in

Table 2.

Table 2.

Physical properties of basalt aggregates.

Table 2.

Physical properties of basalt aggregates.

| Property | Coarse Aggregate | Fine Aggregate | Test Method |

|---|

| Specific gravity (SSD) | 2.83 | 2.80 | ASTM C127/C128 [34] |

| Water absorption (%) | 1.0 | 1.3 | ASTM C127/C128 [34] |

| Los Angeles abrasion (%) | 21% | - | ASTM C131 [36] |

| Flakiness index (%) | 18% | - | BS 812 [37] |

| Aggregate type | Crushed basalt | Crushed basalt | - |

RAP aggregates, after binder extraction, were characterized separately to determine their independent physical properties. The extracted RAP aggregates demonstrated slightly higher absorption (1.5–1.8%) compared with virgin basalt, attributed to residual binder coating and microcracking generated during milling. The Los Angeles abrasion ranged between 18–20%, still within acceptable limits due to the high-quality basalt parent rock. RAP gradation was screened and adjusted to match the target job-mix formula, ensuring the RAP fraction contributed appropriately to the mixture’s coarse and fine aggregate skeleton.

RAP was incorporated at 30 wt.% by total aggregate mass, which corresponds to approximately 30 wt.% RAP binder replacement in the blended binder formulation. This RAP content reflects common practice in warm-mix RAP applications and provides a meaningful level of binder aging influence for evaluating the effects of REOW and SBS modification.

The general physical and binder recovery properties of the RAP material are summarized in

Table 3.

Table 3.

General properties of RAP materials.

Table 3.

General properties of RAP materials.

| Property | RAP Aggregate | Test Method |

|---|

| Maximum size | 19 mm | ASTM C136 [33] |

| Asphalt content (%) | 5.2–5.6% | ASTM D2172 [23] |

| Moisture content (%) | <1% | ASTM D1461 [38] |

| Specific gravity (SSD) | 2.70–2.74 | ASTM C127/C128 [34] |

| Water absorption (%) | 1.5–1.8% | ASTM C127/C128 [34] |

| Los Angeles abrasion (%) | 18–20% | ASTM C131 [36] |

2.1.3. Additives

Two additives were used to modify the blended binder systems: REOW as a rejuvenating agent and SBS as a polymer modifier. These additives were selected to evaluate the combined restoration and reinforcement mechanisms required for warm-mix RAP applications with a high proportion of aged polymer-modified binder.

In accordance with recent classifications of bitumen additives, waste engine oil derivatives are considered plasticizers due to their ability to increase binder fluidity and reduce stiffness by replenishing maltene fractions, as discussed in recent studies [

39]. According to Prysiazhnyi et al. (2024) [

39], plasticizing additives for road bitumen are defined as materials that increase penetration and ductility while only marginally affecting the softening point, a functional behavior that justifies classifying recycled engine oil waste as a plasticizer rather than a reactive modifier.

REOW is an aromatic-rich, low-viscosity petroleum-derived plasticizer-type rejuvenator, consistent with recent classifications of waste engine oil derivatives, and is used to restore aged binder by replenishing lost maltenes and reducing asphaltene agglomeration [

15]. Its composition typically includes light maltene fractions, dispersants, and residual antioxidants, which facilitate the restoration of aged RAP binder by replenishing lost aromatics and reducing asphaltene agglomeration. The general properties of REOW is presented in

Table 4.

Table 4.

Properties of REOW rejuvenator and SBS polymer.

Table 4.

Properties of REOW rejuvenator and SBS polymer.

| Property | REOW | SBS Polymer | Test Method |

|---|

| Appearance | Dark brown, low-viscosity liquid | Light-colored granules | Visual |

| Viscosity (135 °C) | <100 mPa·s | - | ASTM D445 [40] |

| Flash point (°C) | >220 °C | - | ASTM D92 [41] |

| Specific gravity | 0.88–0.92 | 0.94–0.98 | ASTM D70 [42] |

| Ash content (%) | <0.5% | - | ASTM D482 [43] |

| Styrene content (%) | - | ~30% | Manufacturer data |

| Polymer type | - | Linear SBS (tri-block) | - |

| Melt flow index | - | 0.8–1.2 g/10 min | ASTM D1238 [44] |

SBS polymer was used to strengthen the modified binder system and to offset the high-temperature softening effect of REOW. The SBS employed in this study was a linear triblock copolymer with a styrene content of approximately 30% and a melt flow index of 0.8–1.2 g/10 min. This polymer type is widely used in PMB applications due to its ability to form an elastic three-dimensional network that enhances rutting resistance, elastic recovery, and strain-tolerance under repeated loading.

For hybrid modification, REOW was first blended into the virgin RAP binder mixture to ensure uniform diffusion and softening of the aged binder components. SBS was then added under high-shear mixing to achieve complete polymer swelling and dispersion. This sequential approach ensured both effective rejuvenation of the RAP binder fraction and proper network formation of the SBS polymer. The general characteristics of REOW and SBS used in this study are summarized in

Table 4. 2.2. Binder Preparation and Blending Procedure

All binders were prepared by blending 30 wt.% recovered RAP binder with 70 wt.% virgin 60/70 binder, followed by the incorporation of REOW and SBS according to the target modification levels as shown in

Table 5. The blending procedure was designed to ensure proper softening of the aged RAP binder, complete diffusion of rejuvenator, and full polymer development for the SBS-modified systems. The general workflow followed ASTM D7173 [

45] recommendations for binder conditioning and modification.

The virgin 60/70 binder was heated to 150 ± 5 °C, while the recovered RAP binder was preheated to 160 °C to ensure adequate fluidity. The two binders were blended for 20 min at 700 rpm under controlled temperature to obtain a homogeneous base binder.

For REOW-modified binders (B1 and B4), the rejuvenator was added at 135–140 °C and mixed for 20 min at 500–700 rpm to promote effective diffusion into the aged RAP binder. For SBS-modified binders (B4), SBS pellets were subsequently introduced at 175–180 °C and mixed under high shear (3000–4000 rpm) for 60 min to ensure complete polymer swelling and network formation. After modification, SBS-containing binders were conditioned for an additional 30 min at 160 °C to stabilize the polymer structure.

Binder characterization was conducted on unaged and RTFO-conditioned samples. RTFO aging was applied in accordance with ASTM D2872 [

46] solely as a short-term conditioning step to simulate the oxidative and volatilization effects associated with warm-mix asphalt production and RAP incorporation. The purpose of RTFO conditioning was not to evaluate binder aging resistance, but to ensure that rheological testing was performed under conditions representative of mixture production.

2.3. Binder Testing Methods

A comprehensive binder testing program was conducted to evaluate the effects of RAP, REOW, and SBS modification on binder rheology and to establish the performance characteristics needed for subsequent mixture-level assessment. All testing protocols followed ASTM and AASHTO standards to ensure reproducibility and comparability with existing literature.

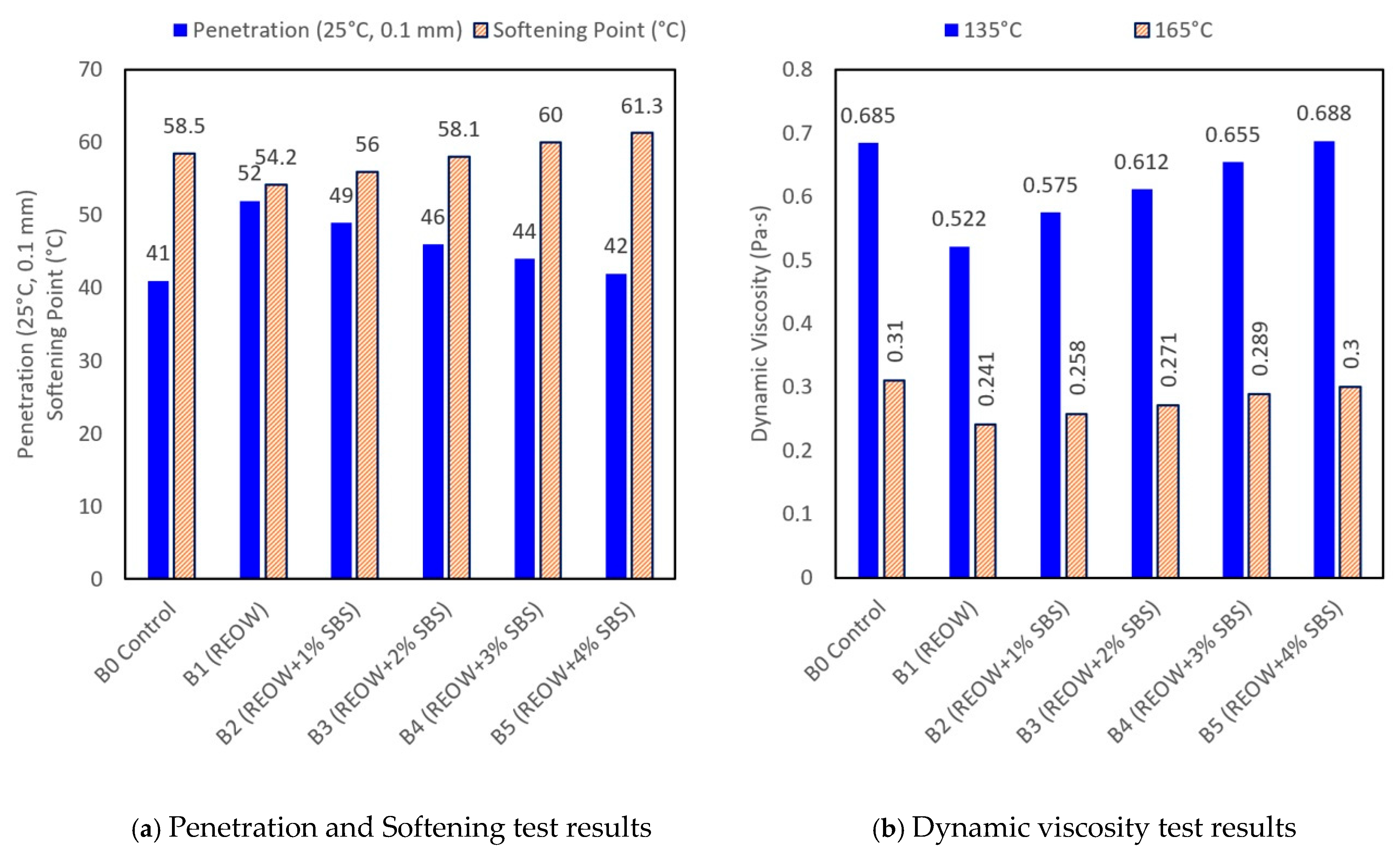

Penetration (ASTM D5 [

27]), softening point (ASTM D36 [

47]), ductility (ASTM D113 [

29]), and rotational viscosity (ASTM D4402 [

30]) were measured to establish the baseline physical characteristics of the virgin binder, recovered RAP binder, and REOW–SBS modified binders, and to screen the appropriate REOW dosage (1–4 wt.%) prior to selecting the final formulation. Short-term and long-term aging were performed using the RTFO (ASTM D2872 [

46]) at 163 °C and the PAV (ASTM D6521 [

48]) at 100 °C for 20 h, ensuring that the binders reflected realistic aging conditions associated with warm-mix production and RAP incorporation.

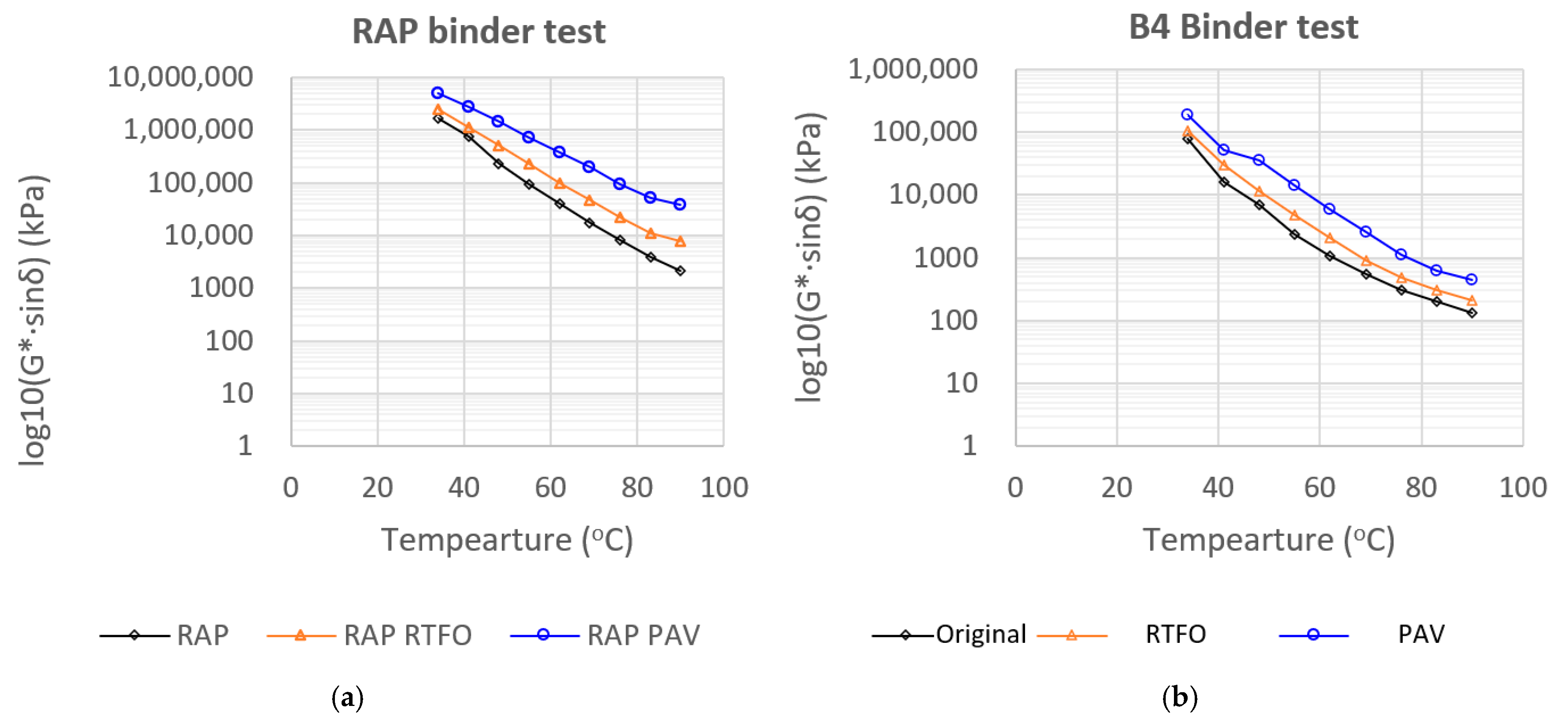

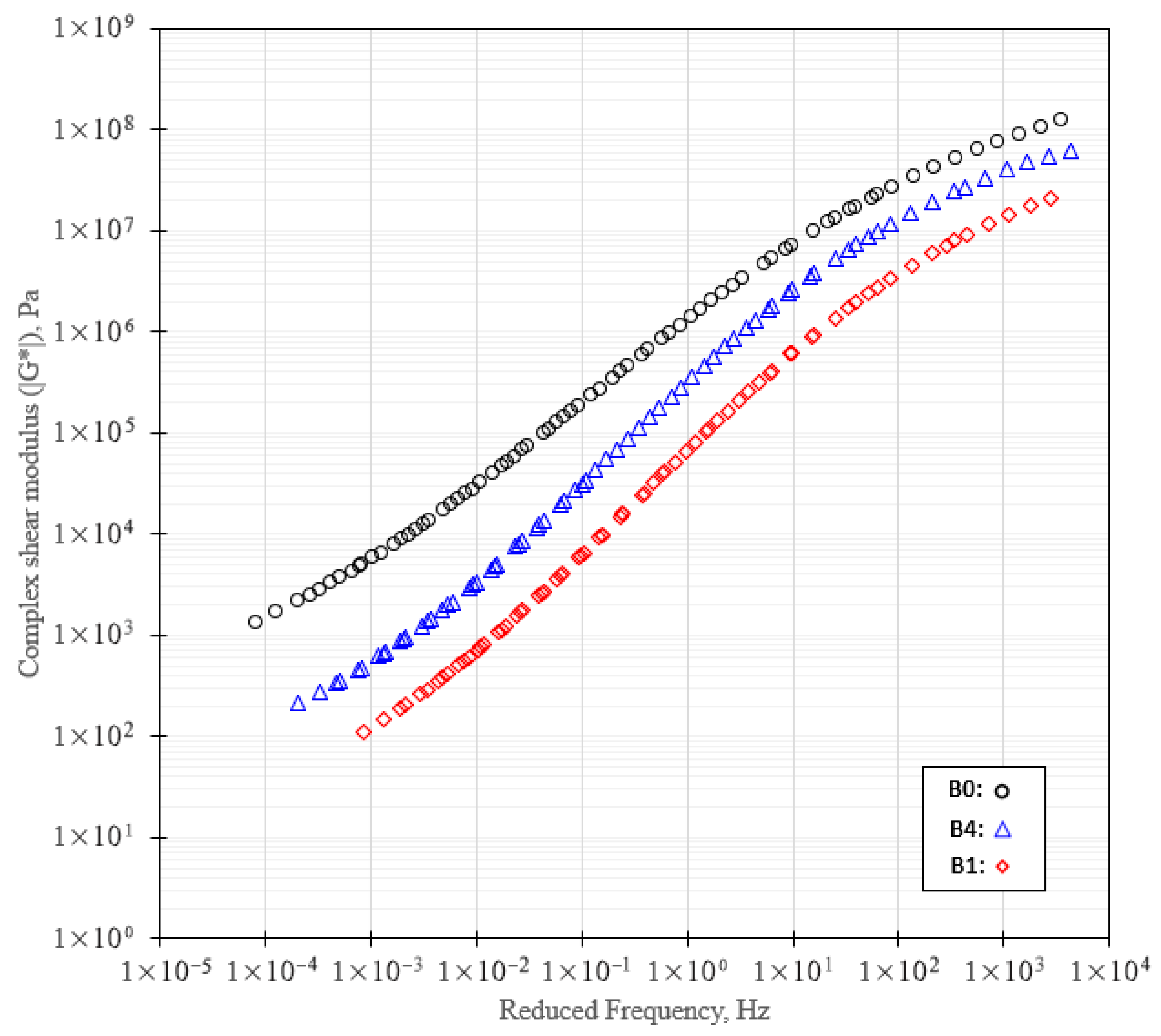

Rheological characterization was conducted using a Dynamic Shear Rheometer (ASTM D7175 [

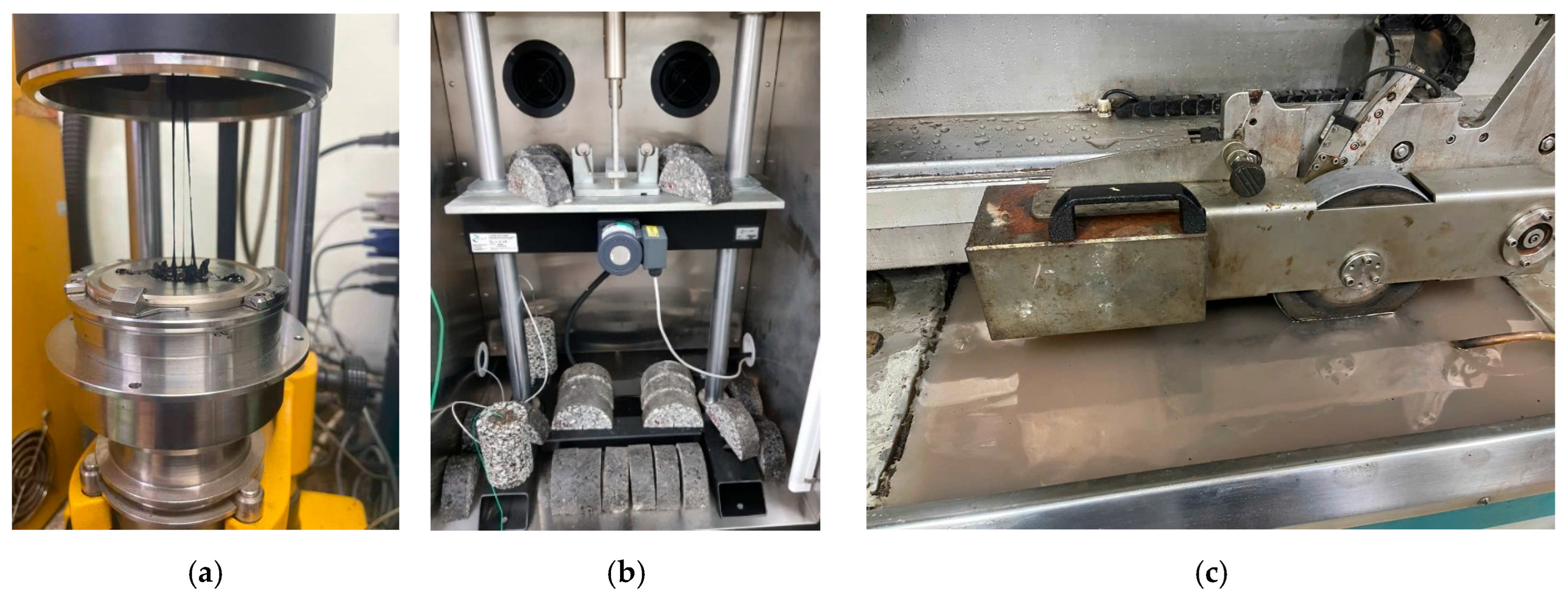

31]) (

Figure 3a), including temperature sweep tests (46–82 °C) to determine complex shear modulus (G*). Frequency sweep tests (0.1–100 rad/s) were further used to construct master curves using time–temperature superposition, providing detailed insight into binder viscoelasticity, stiffness evolution, and temperature susceptibility across modification levels.

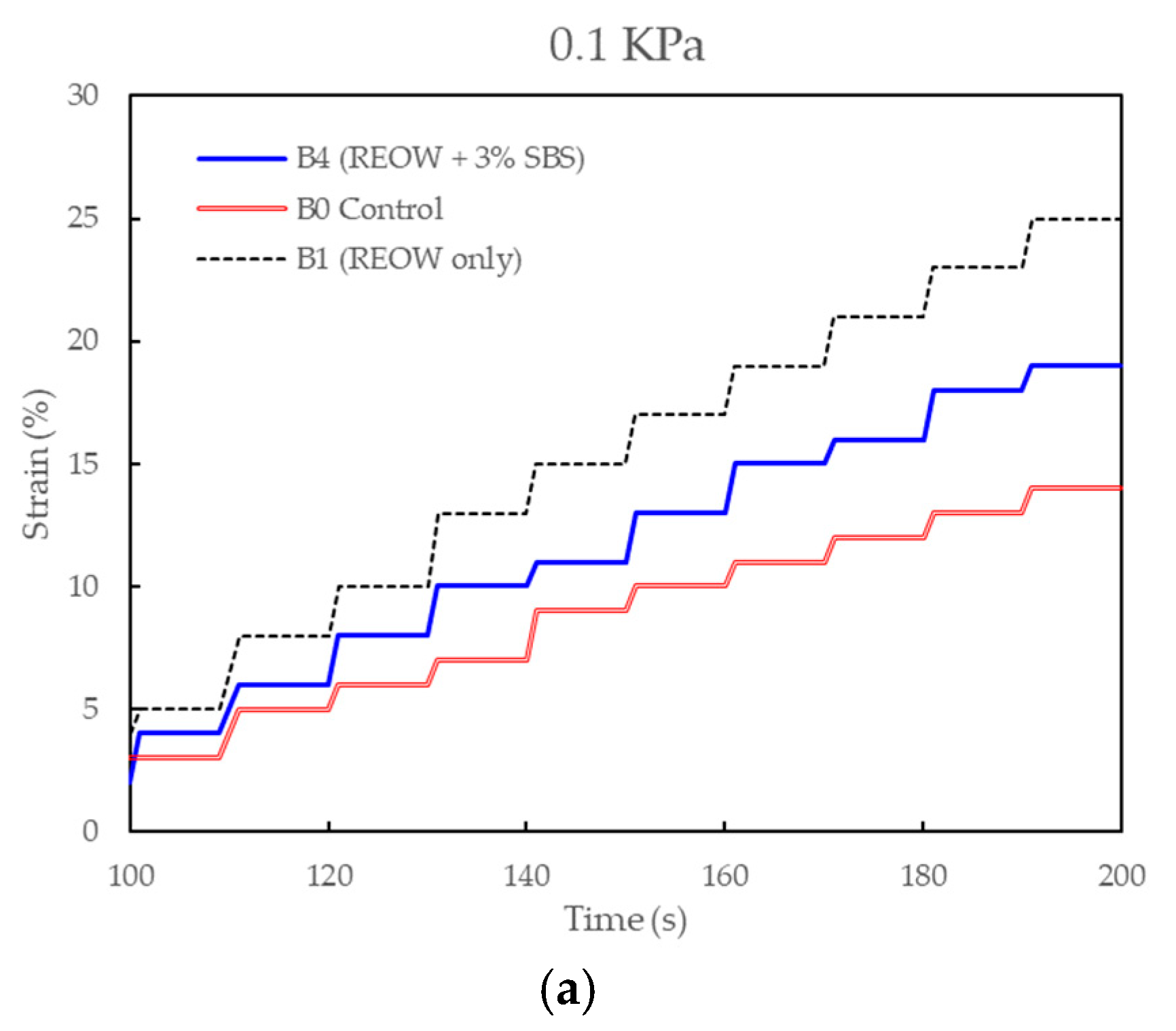

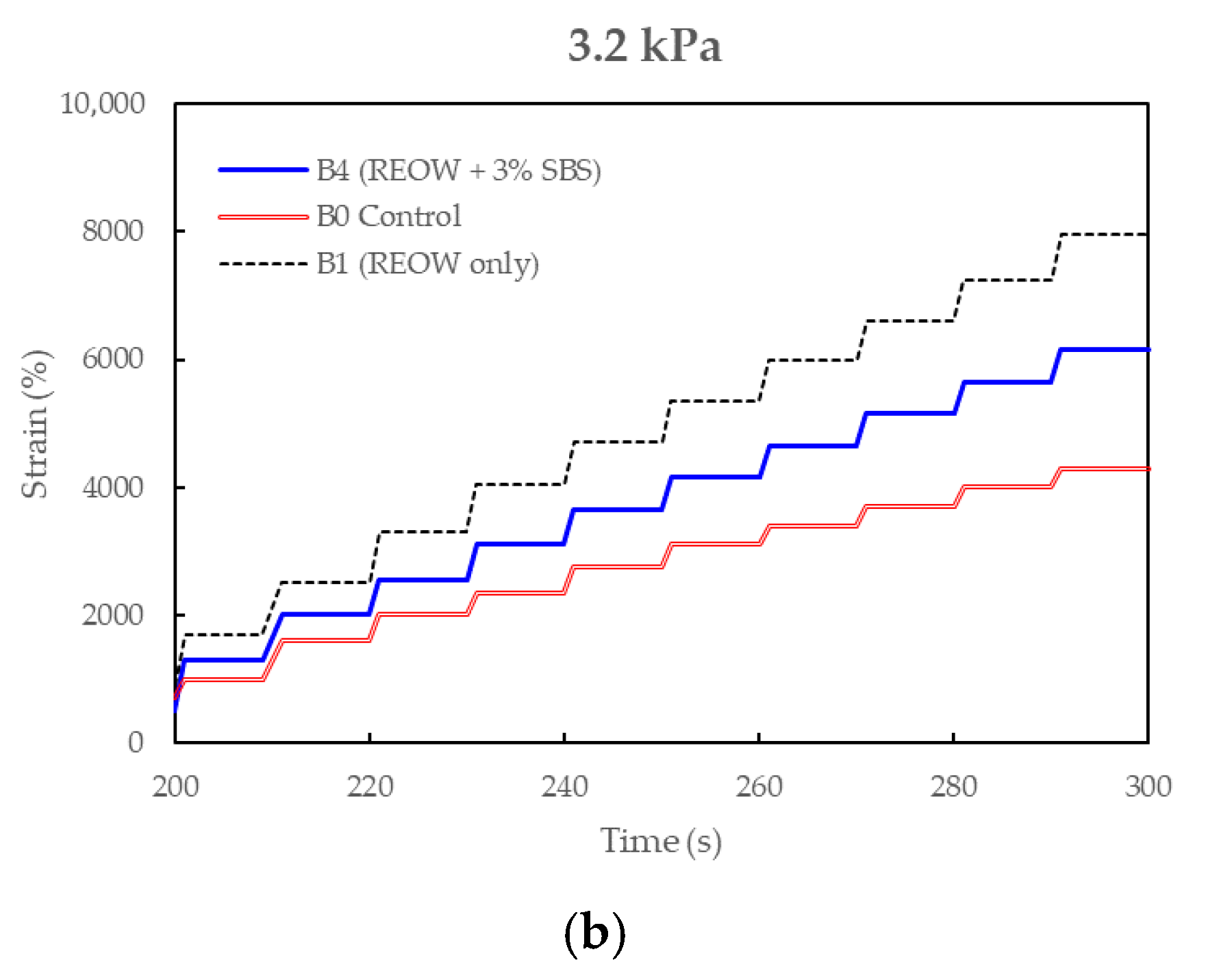

MSCR tests were performed in accordance with ASTM D7405 [

32] to evaluate high-temperature deformation resistance and elastic recovery of the modified binders. Tests were conducted at 3.2 kPa and 0.1 kPa stress levels, capturing both stress sensitivity and polymeric recovery behavior.

2.4. Warm Asphalt Mixture Preparation

WMA mixtures were produced using REOW as the warm-mix additive to enable reduced production temperatures while incorporating a high RAP content. All mixtures followed a 13 mm NMAS dense-graded gradation and contained 30 wt.% RAP aggregate by total mixture mass.

The average asphalt content of RAP was determined by extraction to be approximately 5.3 wt.%, resulting in a RAP binder contribution of 1.6 wt.% of the mixture. The total binder content was fixed at 5.0 wt.%, and virgin 60/70 binder (with or without REOW and SBS modification) was added by difference to achieve the target binder content. No predefined RAP binder–virgin binder blending ratio was imposed.

Three main mixture types were prepared: M0 using the control binder (B0), M1 incorporating REOW-modified binder (B1), and M4 incorporating the hybrid REOW–SBS modified binder (B4). The mixture preparation procedure was kept identical for all mixtures, with adjustments applied only to mixing and compaction temperatures to account for viscosity reductions induced by the WMA additive.

Virgin aggregates were oven-dried at 110 ± 5 °C and preheated to their designated mixing temperature. RAP materials were dried at 60–70 °C to prevent additional oxidative aging while ensuring sufficient moisture removal. Virgin and RAP aggregates were then combined in their specified proportions and dry-mixed to achieve temperature uniformity prior to binder addition. The prepared binder was introduced gradually under continuous mechanical mixing to ensure uniform coating of both virgin and RAP aggregates. Mixing temperatures were set at 160–165 °C for the control mixture and reduced to 145–150 °C for REOW-containing mixtures, based on binder viscosity results reported in

Section 2.3.

Compaction was carried out using a Superpave gyratory compactor at the corresponding compaction temperatures. The control mixture (M0) was compacted at 150–155 °C, whereas REOW-containing mixtures (M1 and M4) were compacted at 135–140 °C due to enhanced binder mobility. All mixtures were compacted to N_design = 75 gyrations, targeting 4.0 ± 0.5% air voids. After compaction, specimens were allowed to cool for 24 h and were subsequently cut or conditioned to meet the dimensional requirements for mechanical testing, including ITS, TSR, Cantabro loss, Hamburg wheel tracking, Overlay Test, and SCB fracture energy. The final composition of the studied mixtures is presented in

Table 6. It should be noted that RAP aggregate, virgin aggregate, and total binder contents are expressed as wt.% of total mixture mass (

Table 6), whereas RAP binder contribution, virgin binder addition, REOW, and SBS contents are expressed relative to the total binder mass (

Table 5).

2.5. Mixture Testing Methods

A comprehensive mixture-level testing program was conducted to evaluate the mechanical performance of the WMA mixtures incorporating RAP, REOW, and SBS. After compaction and 24-h conditioning at room temperature, specimens were prepared for each performance test following the dimensional and environmental requirements prescribed in the corresponding ASTM and AASHTO standards.

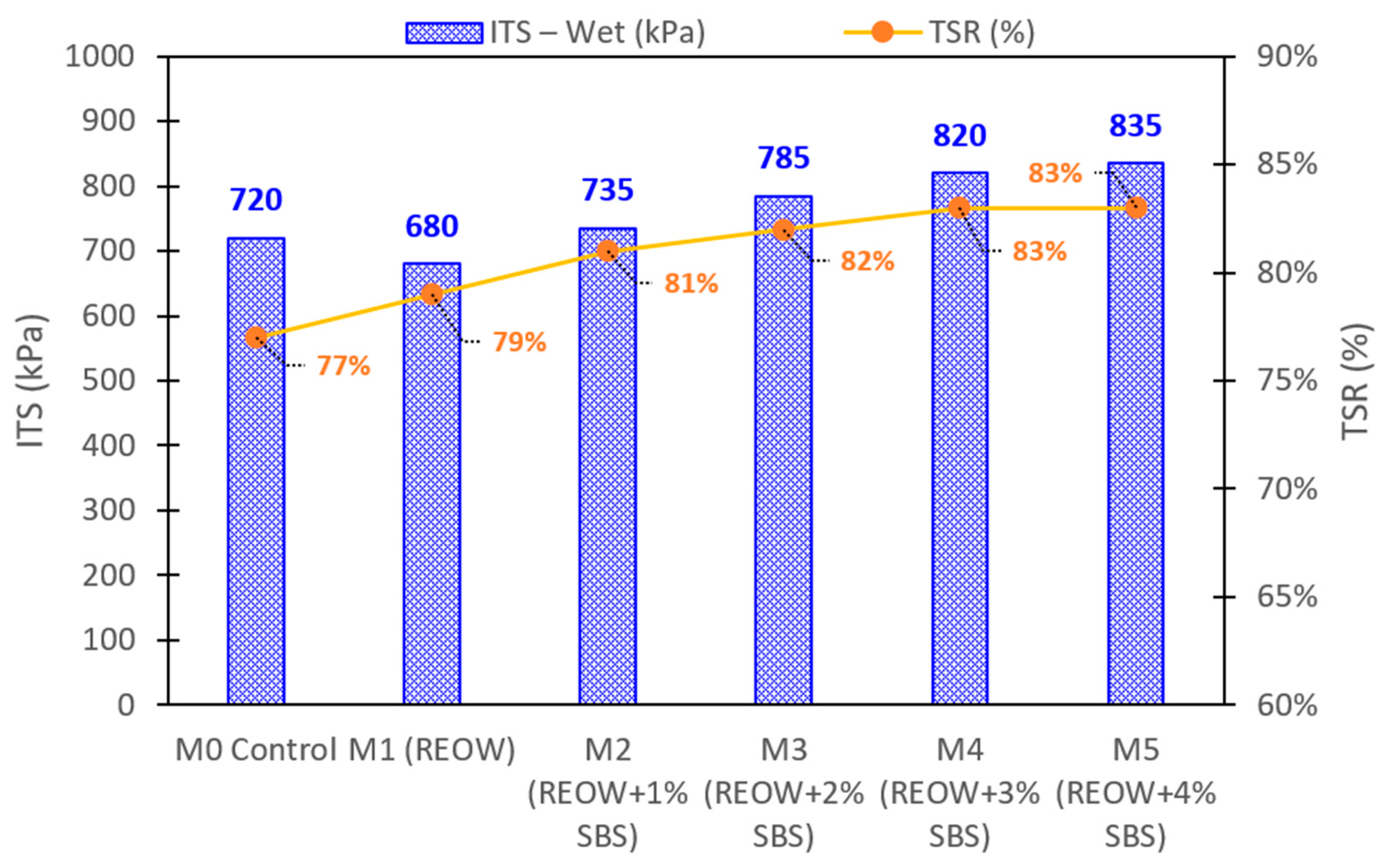

ITS and TSR tests were carried out according to ASTM D6931 [

49] and AASHTO T283 [

50], respectively. Cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 100 mm and a height of approximately 63.5 mm were tested at 25 °C using a loading rate of 50 mm/min. TSR measurements were obtained by conditioning half of the specimens in a freeze–thaw cycle while keeping the other half dry, allowing the evaluation of moisture susceptibility and adhesive bonding performance in the presence of RAP and rejuvenator.

The raveling resistance of the mixtures was assessed using the Cantabro loss test (ASTM D7064 [

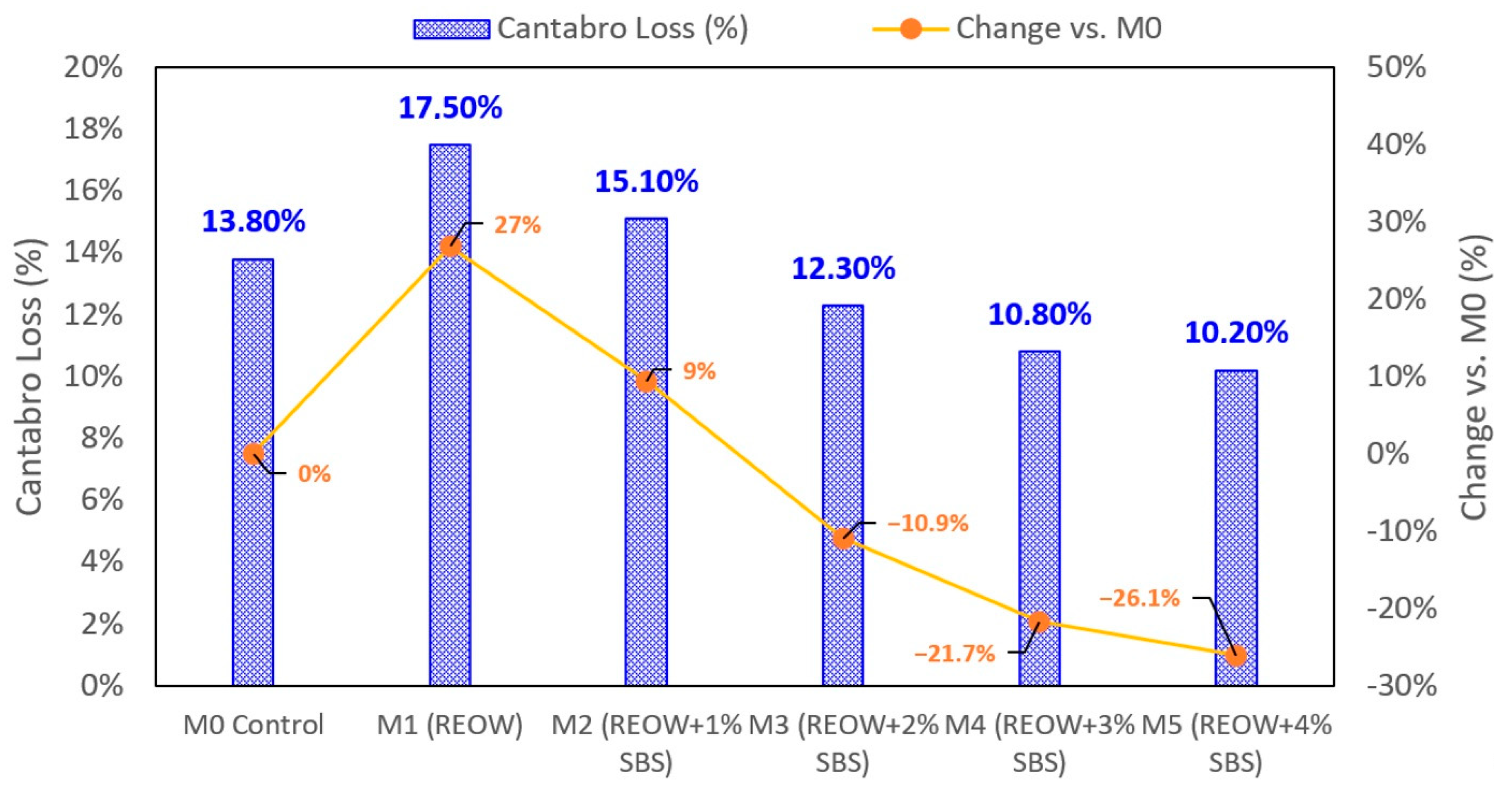

51]). This test was performed on 100-mm-diameter gyratory-compacted specimens without steel balls, using 300 drum revolutions at room temperature. The difference between initial and final specimen mass was used to calculate surface abrasion and aggregate retention, providing insight into the cohesion of the modified binder and RAP–virgin aggregate interface.

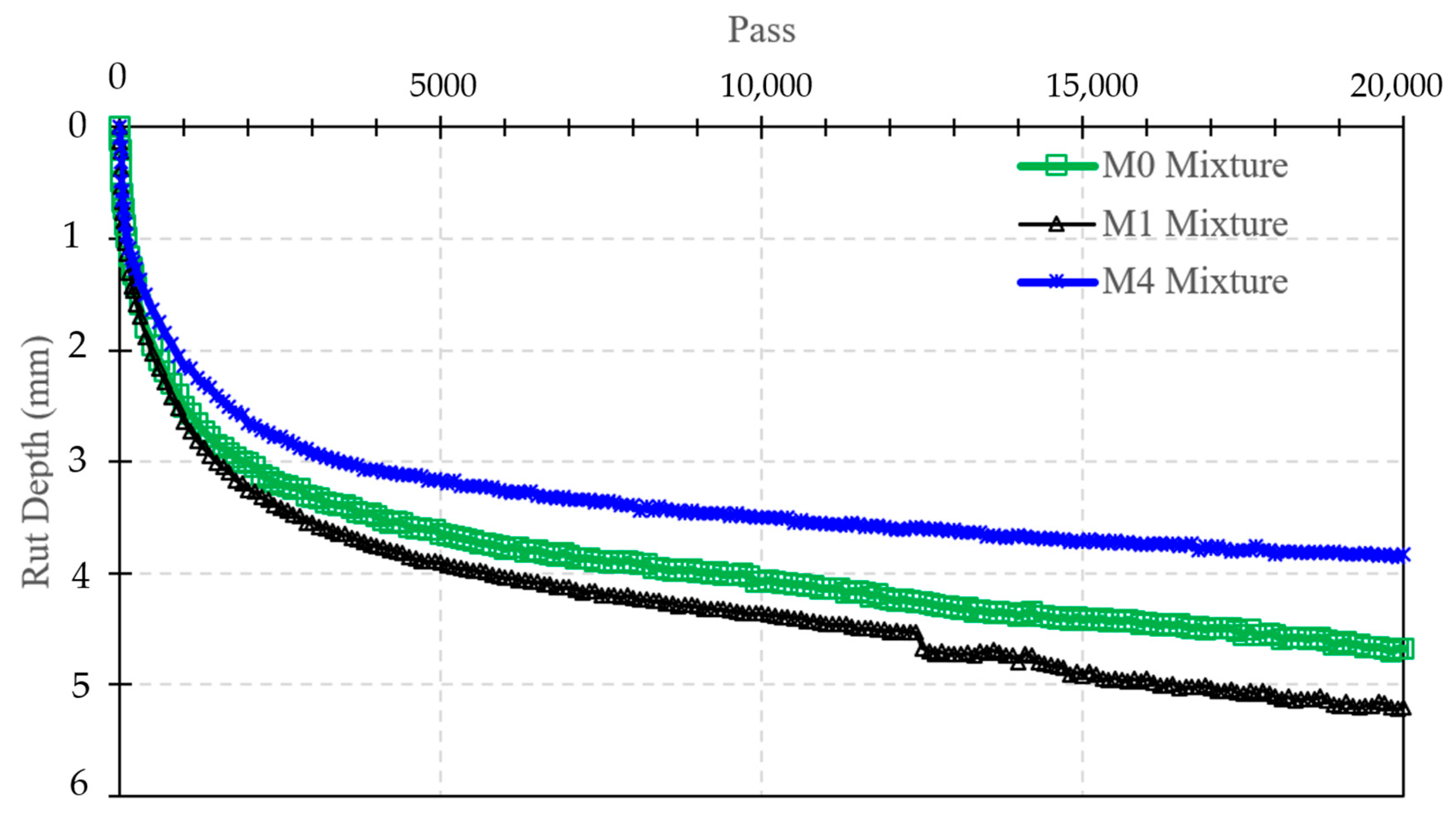

Rutting performance was evaluated using the Hamburg Wheel Tracking Test (AASHTO T324 [

52]). Slab specimens were compacted and cut to the required dimensions before being submerged in a 50 °C water bath (see

Figure 3b). The wheel tracking device applied repeated loading cycles up to 20,000 passes while monitoring rut depth progression. The test allowed identification of permanent deformation behavior, rutting rate, and the occurrence of stripping inflection points in the presence of REOW and SBS.

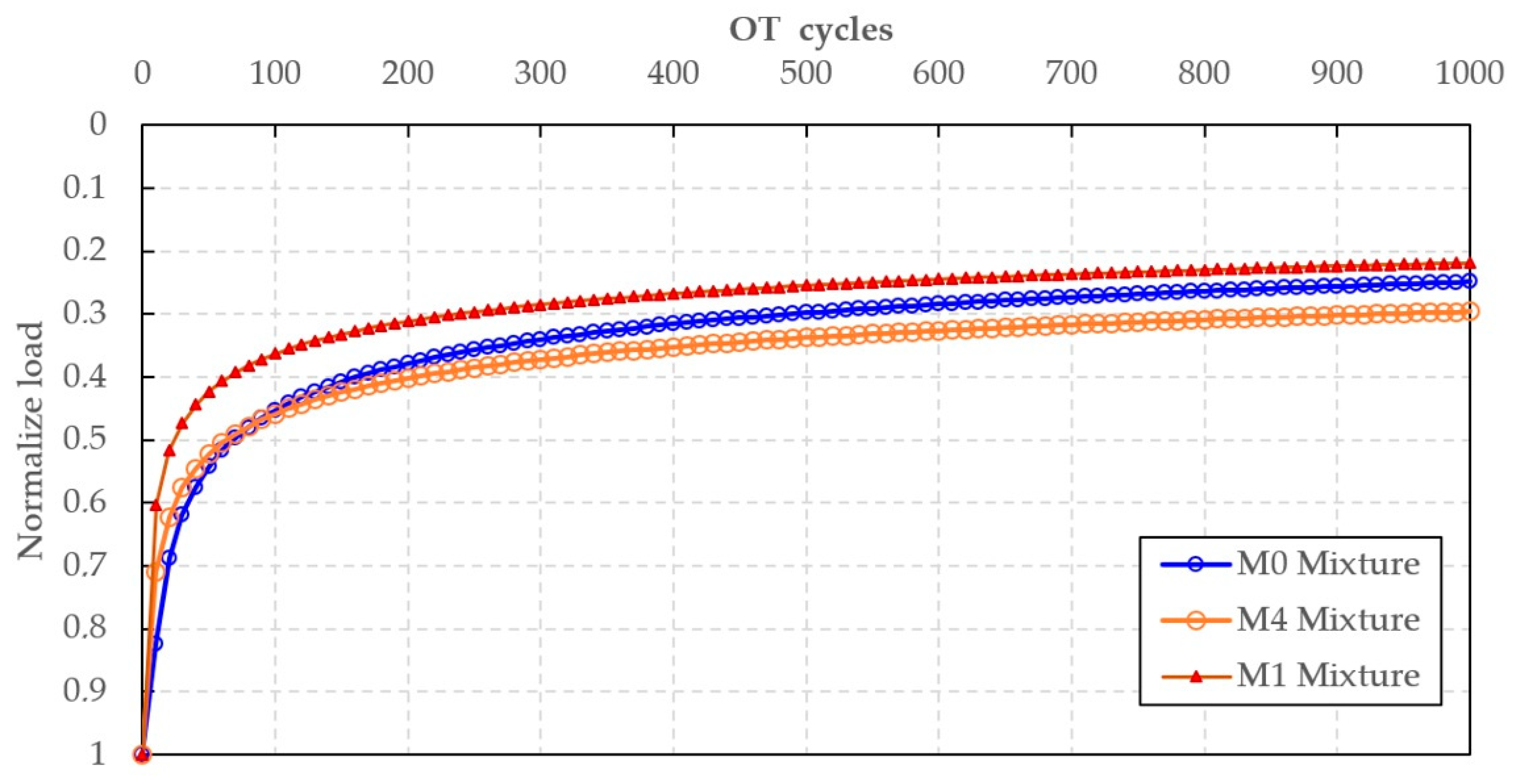

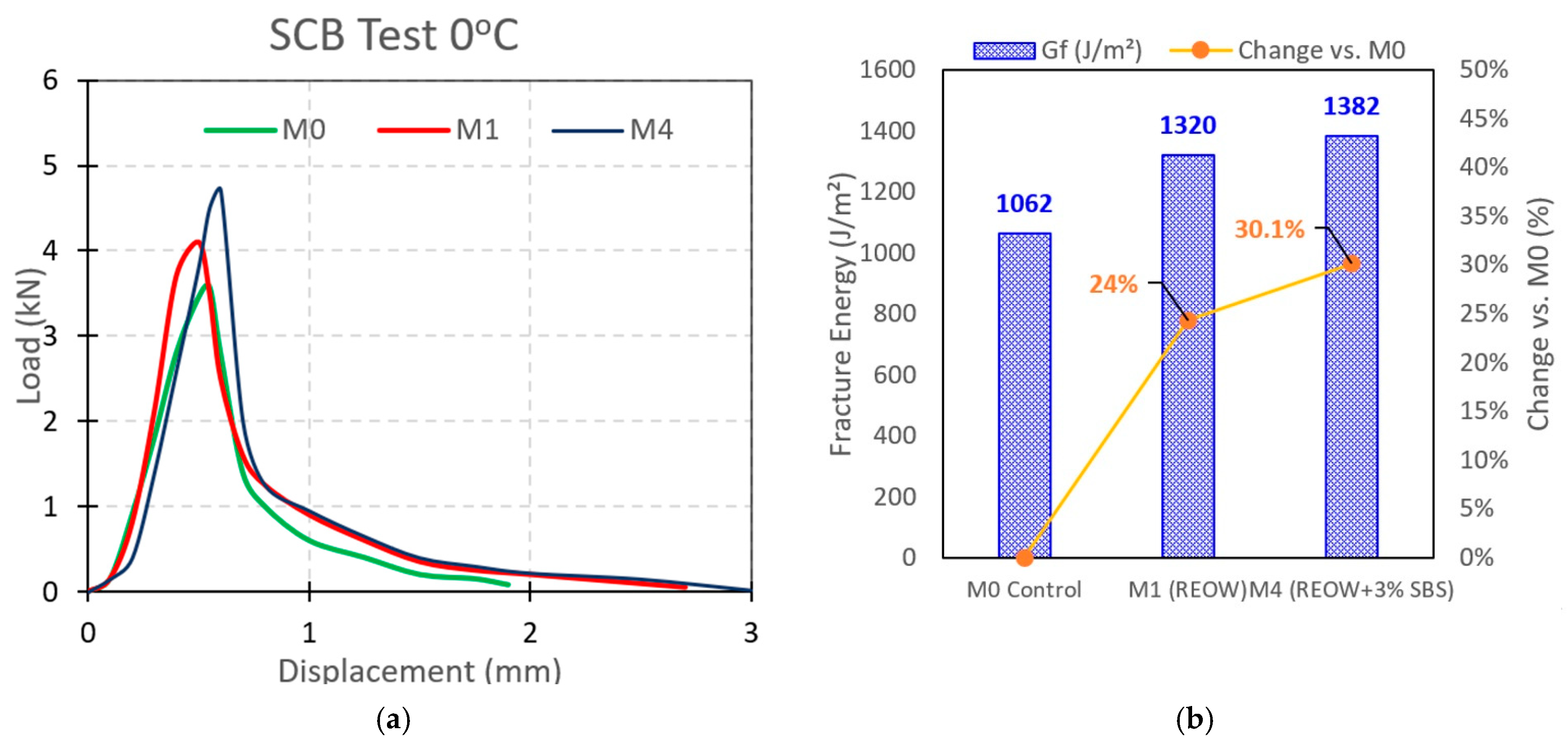

Cracking resistance was examined using both the OT and the SCB test. The OT was performed following Tex-248-F [

53] to assess reflective cracking susceptibility under repeated opening–closing displacements. Beam specimens were conditioned at 25 °C and subjected to cyclic displacements of 0.025 inches, from which normalized peak load degradation and stripping inflection patterns were obtained. The SCB test was conducted in accordance with ASTM D8044 [

54] at 0 °C using semicircular specimens with a 50-mm thickness and a 15-mm notch depth (see

Figure 3c). Load–displacement curves were used to determine fracture energy and post-peak softening behavior, enabling evaluation of low-temperature cracking performance.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the feasibility of combining recycled engine oil waste and SBS polymer to rehabilitate polymer-modified RAP binder and to produce high-RAP warm-mix asphalt containing 30 wt.% RAP. The following conclusions can be drawn:

Binder-level performance recovery was quantitatively confirmed. The recovered RAP binder exhibited severe aging, whereas hybrid modification using 3 wt.% REOW and 3 wt.% SBS (B4) restored rheological profile. Compared with the control binder, B4 achieved a penetration of 44 dmm and a softening point of 60.0 °C, while maintaining rotational viscosities of 0.655 Pa·s at 135 °C and 0.289 Pa·s at 165 °C. MSCR results showed that REOW increased non-recoverable creep compliance at 3.2 kPa from 1.34 to 2.48 kPa−1 while reducing recovery from 58.1% to 22.6%, whereas SBS incorporation moderated this effect, yielding a response with Jnr of 1.92 kPa−1 and recovery of 32.5%.

Mixture performance results demonstrate clear benefits of the REOW–SBS hybrid system. At the mixture scale, the hybrid mixture (M4) achieved a wet ITS of 820 kPa and a TSR of 83%, exceeding the commonly adopted 80% moisture resistance criterion, whereas the control mixture remained below this threshold (77%). Cantabro loss was reduced from 13.8% (M0) to 10.8% (M4), indicating improved resistance to raveling. Hamburg wheel tracking results showed that rut depth at 20,000 cycles decreased from 4.4 mm (M0) and 4.9 mm (M1) to 3.9 mm for M4, corresponding to an approximately 12–20% reduction in permanent deformation.

Cracking resistance was markedly enhanced through the combined effects of REOW rejuvenation and SBS polymer reinforcement. The SCB fracture energy increased from 1062 J/m2 for the control mixture (M0) to 1320 J/m2 with REOW modification alone (M1) and further to 1382 J/m2 for the REOW–SBS hybrid mixture (M4), corresponding to improvements of approximately 24% and 30%, respectively, relative to the control. Overlay Test results showed a higher residual load at 1000 cycles (≈0.30–0.32 for M4 versus ≈0.25 for M0), confirming the superior resistance of the hybrid mixture to fatigue-induced cracking.

Overall, the hybrid REOW–SBS mixture (M4) delivered the most balanced performance, achieving 14% higher wet ITS and 6% higher TSR than the control, 22–26% lower Cantabro loss, and approximately 20% lower Hamburg rut depth after 20,000 passes without evidence of stripping. It also produced about 30% higher SCB fracture energy and the highest Overlay Test residual load, demonstrating that the combination of REOW-induced flexibility and SBS-derived elasticity acts synergistically to resist cracking, raveling, and permanent deformation in RAP-rich warm-mix asphalt systems.

The findings are based on laboratory-scale testing using a single RAP source derived from a polymer-modified surface course and a fixed RAP content of 30 wt.%. Long-term field validation, evaluation under different RAP sources and polymer types, and durability under extended aging conditions were not addressed in this study. Therefore, while the results demonstrate technical feasibility and performance potential, direct field implementation should be preceded by project-specific mixture design verification and agency acceptance testing.