The Potential Lubricating Mechanism of Alginate Acid and Carrageenan on the Inner Surface of Orthokeratology Lenses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Orthokeratology Lens and Reagents

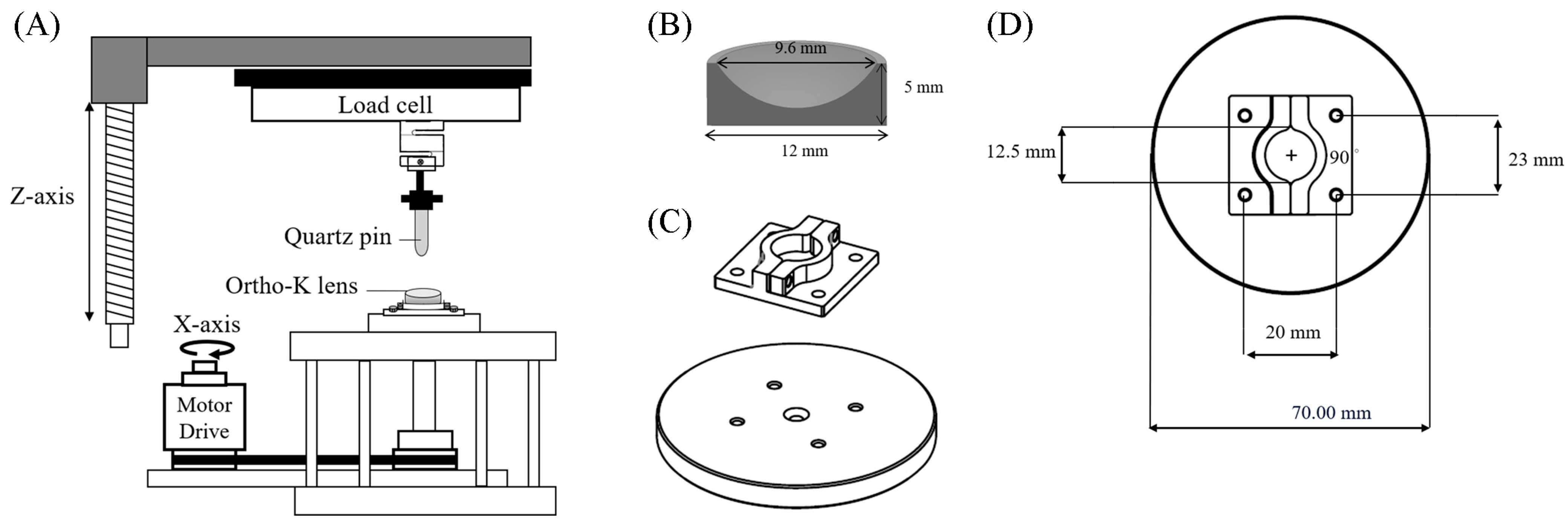

2.2. In Vitro Tribological Property Analysis for Ortho-K Lenses

2.3. Adsorption and Desorption Analyses

2.4. Viscosity

2.5. Measurement of Zeta Potential

2.6. Turbidity

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

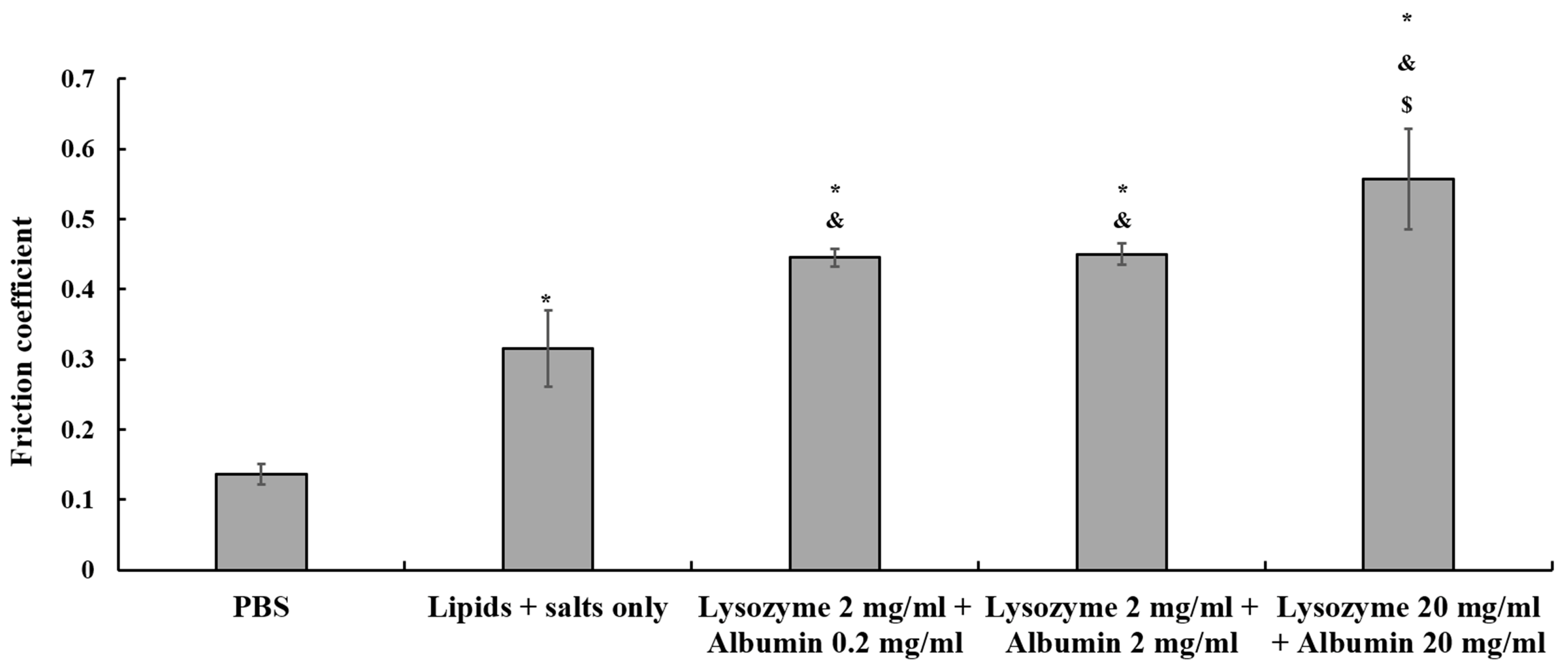

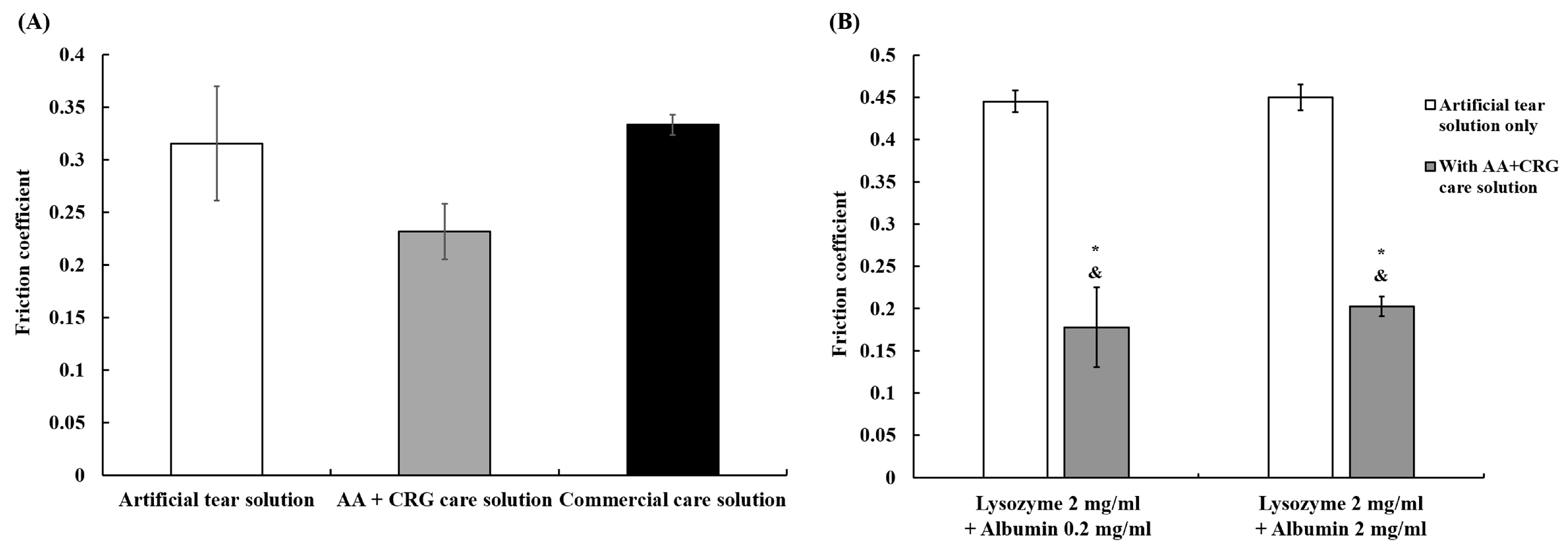

3.1. The Effects of Various Solutions on the Friction Coefficient of Ortho-K Lenses

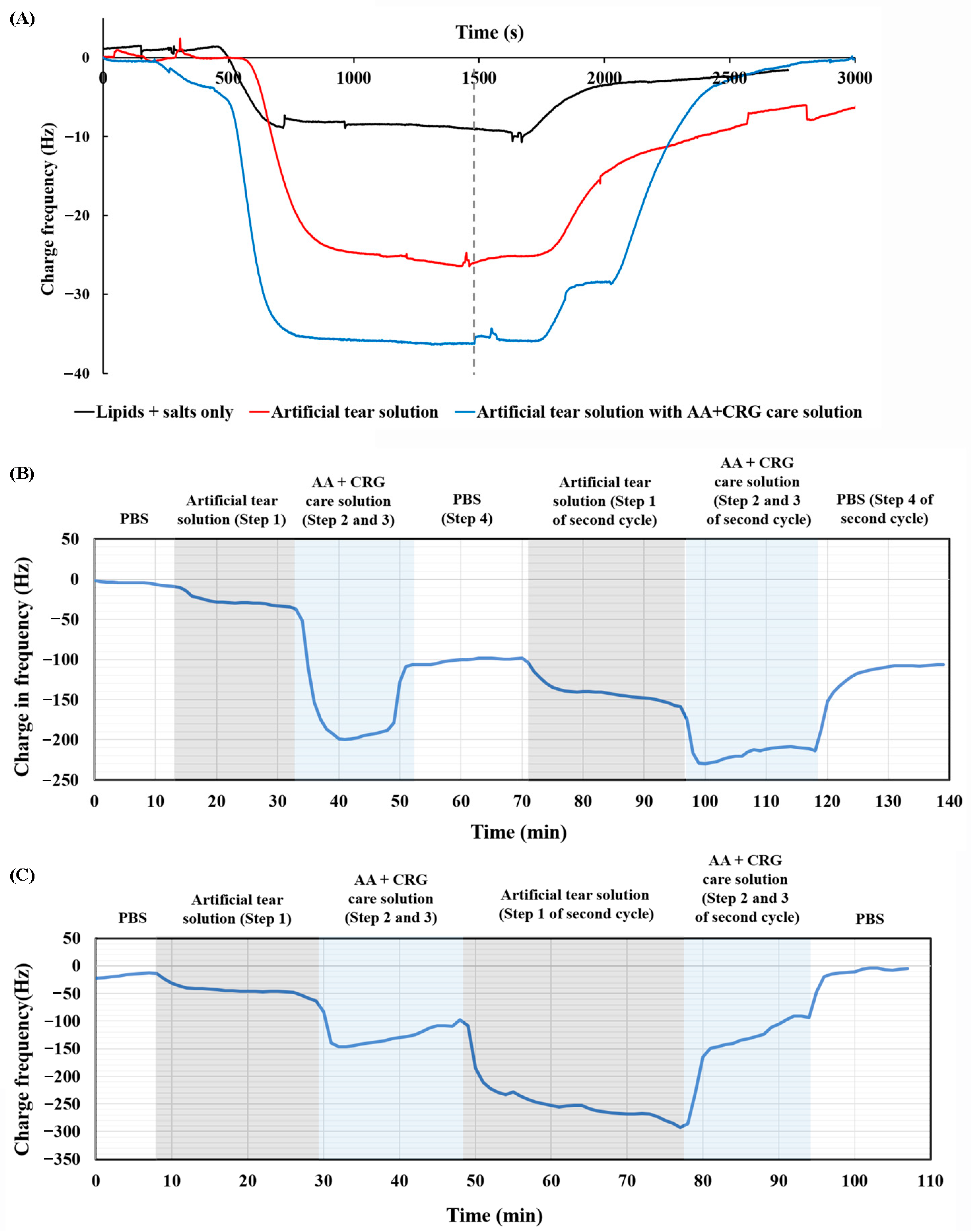

3.2. Adsorption and Desorption Behavior of AA + CRG Care Solution on PMMA-Coated Surface

3.3. The Potential Interaction Between AA + CRG Care Solution and Tear Film Proteins

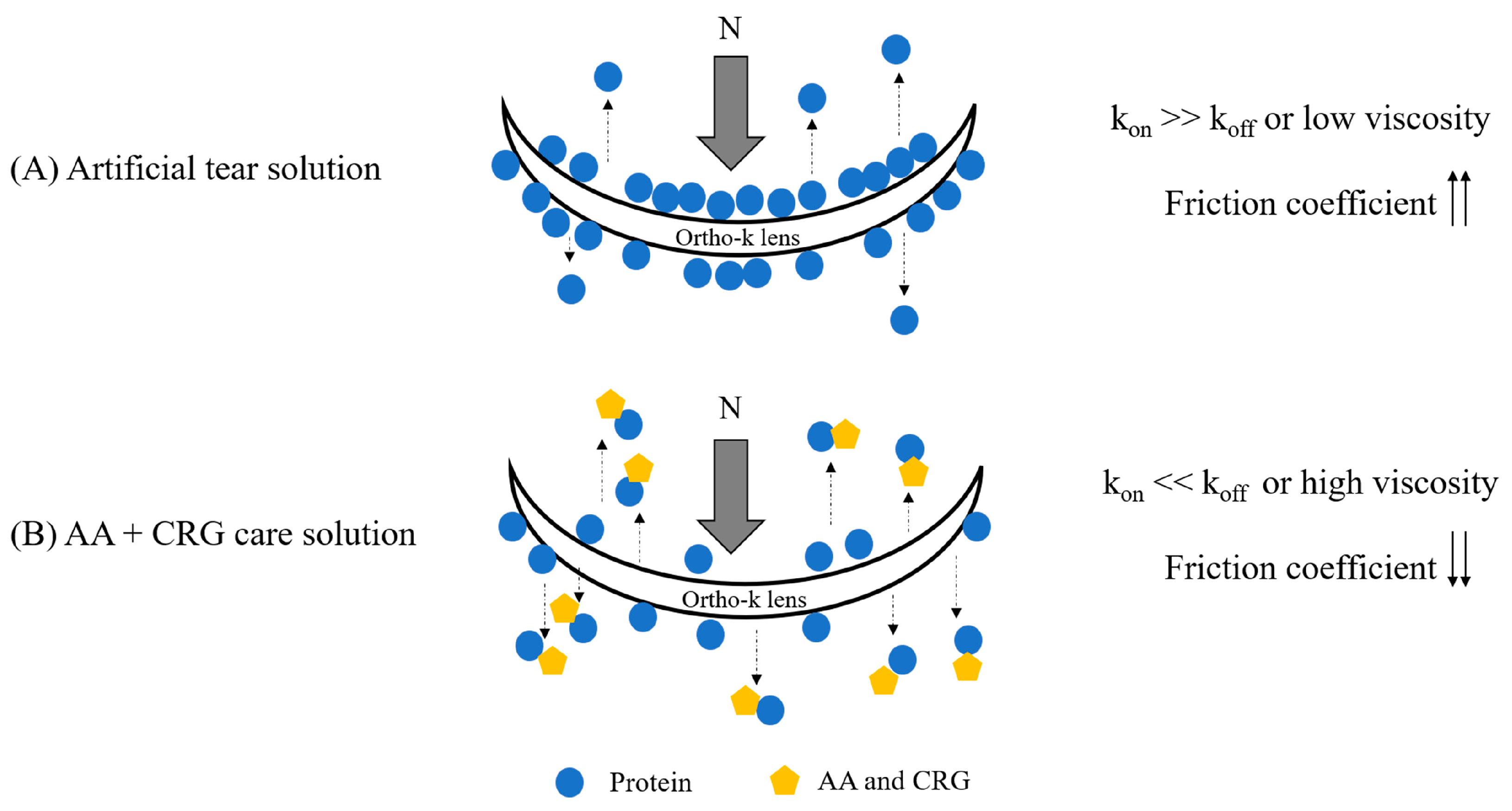

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holden, B.A.; Fricke, T.R.; Wilson, D.A.; Jong, M.; Naidoo, K.S.; Sankaridurg, P.; Wong, T.Y.; Naduvilath, T.J.; Resnikoff, S. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezinne, N.E.; Bhattarai, D.; Ekemiri, K.K.; Harbajan, G.N.; Crooks, A.C.; Mashige, K.P.; Ilechie, A.A.; Zeried, F.M.; Osuagwu, U.L. Demographic profiles of contact lens wearers and their association with lens wear characteristics in trinidad and tobago: A retrospective study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullimore, M.A.; Johnson, L.A. Overnight orthokeratology. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2020, 43, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrigin, J.; Perrigin, D.; Quintero, S.; Grosvenor, T. Silicone-acrylate contact lenses for myopia control: 3-year results. Optom. Vis. Sci. 1990, 67, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bontempo, A.R.; Rapp, J. Protein-lipid interaction on the surface of a rigid gas-permeable contact lens in vitro. Curr. Eye Res. 1997, 16, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.Y.; Yeh, L.K.; Huang, P.H.; Lin, W.P.; Huang, H.F.; Lai, C.C.; Fang, H.W. Long-term effects of tear film component deposition on the surface and optical properties of two different orthokeratology lenses. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2023, 46, 101852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.Y.; Yeh, L.K.; Tsao, Y.F.; Lin, W.P.; Hou, C.H.; Huang, H.F.; Lai, C.C.; Fang, H.W. The effect of different cleaning methods on protein deposition and optical characteristics of orthokeratology lenses. Polymers 2021, 13, 4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roba, M.; Duncan, E.G.; Hill, G.A.; Spencer, N.D.; Tosatti, S.G.P. Friction measurements on contact lenses in their operating environment. Tribol. Lett. 2011, 44, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterner, O.; Aeschlimann, R.; Zurcher, S.; Osborn Lorenz, K.; Kakkassery, J.; Spencer, N.D.; Tosatti, S.G. Friction measurements on contact lenses in a physiologically relevant environment: Effect of testing conditions on friction. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 5383–5392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.Y.; Lai, C.C.; Yeh, L.K.; Li, K.Y.; Shih, B.W.; Tseng, C.L.; Fang, H.W. The characteristics of a preservative-free contact lens care solution on lysozyme adsorption and interfacial friction behavior. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 171, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.Y.; Fang, H.W.; Nimatallah, M.; Qatmera, Z.; Kasem, H. Experimental evaluation of the tribological properties of rigid gas permeable contact lens under different lubricants. Lubricants 2025, 13, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Brennan, N.A.; Gonzalez-Meijome, J.; Lally, J.; Maldonado-Codina, C.; Schmidt, T.A.; Subbaraman, L.; Young, G.; Nichols, J.J. The tfos international workshop on contact lens discomfort: Report of the contact lens materials, design, and care subcommittee. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, TFOS37–TFOS70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, A.C.; Tichy, J.A.; Uruena, J.M.; Sawyer, W.G. Lubrication regimes in contact lens wear during a blink. Tribol. Int. 2013, 63, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsom, M.; Chan, A.; Iwabuchi, Y.; Subbaraman, L.; Jones, L.; Schmidt, T.A. In vitro friction testing of contact lenses and human ocular tissues: Effect of proteoglycan 4 (prg4). Tribol. Int. 2014, 89, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.Y.; Tseng, C.L.; Wu, S.H.; Shih, B.W.; Chen, Y.Z.; Fang, H.W. Poly-gamma-glutamic acid functions as an eective lubricant with antimicrobial activity in multipurpose contact lens care solutions. Polymers 2019, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amornvit, P.; Rokaya, D.; Shrestha, B.; Srithavaj, T. Prosthetic rehabilitation of an ocular defect with post-enucleation socket syndrome: A case report. Saudi Dent. J. 2014, 26, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.B.; Pacelli, S.; Haj, A.J.E.; Dua, H.S.; Hopkinson, A.; White, L.J.; Rose, F. Gelatin-based materials in ocular tissue engineering. Materials 2014, 7, 3106–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentz, H.; Heynen, M.; Tran, H.; Jones, L. Using an in vitro model of lipid deposition to assess the efficiency of hydrogen peroxide solutions to remove lipid from various contact lens materials. Curr. Eye Res. 2012, 37, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, N.; Morgan, P.B. Soft contact lens care regimens in the UK. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2008, 31, 283–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frediansyah, A. The antiviral activity of iota-, kappa-, and lambda-carrageenan against COVID-19: A critical review. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 12, 100826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Shen, P.; Peng, Q. Structures, properties and application of alginic acid: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Guo, X.; Mahmoudi, N.; Gobbo, P.; Briscoe, W.H. Lipogels: Robust self-lubricating physically cross-linked alginate hydrogels embedded with liposomes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e14611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, M.; Yuan, J.; Li, P.; Men, X. Graphene enhanced and in situ-formed alginate hydrogels for reducing friction and wear of polymers. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 589, 124434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.E.; Brunet, M.Y.; Chapple, I.; Heagerty, A.H.M.; Metcalfe, A.D.; Grover, L.M. Self-delivering microstructured iota carrageenan spray inhibits fibrosis at multiple length scales. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 2023, 3, 2300048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.P.; Iwasaki, Y.; Osada, Y. Friction of gels. 5. Negative load dependence of polysaccharide gels. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 3423–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozbial, A.; Li, L. Study on the friction of kappa-carrageenan hydrogels in air and aqueous environments. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2014, 36, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Novetsky, A.P.; Keller, M.J.; Gradissimo, A.; Chen, Z.; Morgan, S.L.; Xue, X.; Strickler, H.D.; Fernandez-Romero, J.A.; Burk, R.; Einstein, M.H. In vitro inhibition of human papillomavirus following use of a carrageenan-containing vaginal gel. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 143, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.Y.; Chen, C.C.; Huang, Y.L.; Chen, S.W.; Fang, H.W. Optimization of biomolecular additives for a reduction of friction in the artificial joint system. Tribol. Int. 2017, 111, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y.; Yeh, L.K.; Su, C.Y.; Huang, P.H.; Lai, C.C.; Fang, H.W. The effect of polysaccharides on preventing proteins and cholesterol from being adsorbed on the surface of orthokeratology lenses. Polymers 2022, 14, 4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omali, N.B.; Subbaraman, L.N.; Heynen, M.; Ng, A.; Coles-Brennan, C.; Fadli, Z.; Jones, L. Surface versus bulk activity of lysozyme deposited on hydrogel contact lens materials in vitro. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2018, 41, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barishak, Y.; Zavaro, A.; Samra, Z.; Sompolinsky, D. An immunological study of papillary conjunctivitis due to contact lenses. Curr. Eye Res. 1984, 3, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choy, C.K.; Cho, P.; Benzie, I.F.; Ng, V. Effect of one overnight wear of orthokeratology lenses on tear composition. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2004, 81, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sack, R.A.; Tan, K.O.; Tan, A. Diurnal tear cycle: Evidence for a nocturnal inflammatory constitutive tear fluid. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1992, 33, 626–640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shaw, A.J.; Collins, M.J.; Davis, B.A.; Carney, L.G. Eyelid pressure and contact with the ocular surface. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 1911–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbato, G.; Wehr, T.A. Phasic rem: Across night behavior and transitions to wake. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menicon Pharma. Instructions for Menicare Plus Multipurpose Solution for All Rigid Gas Permeable Lenses; Menicon Pharma: Nagoya, Japan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Oculus Pte Ltd. Patient Instruction Guide for Ocuviq® All-Lenses Cleaner; Oculus Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.W.; Zhou, Y.; Bhattacharya, P.; Erck, R.; Qu, J.; Bays, J.T.; Cosimbescu, L. Probing the molecular design of hyper-branched aryl polyesters towards lubricant applications. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillon, M.; Dumbleton, K.; Theodoratos, P.; Patel, T.; Karkkainen, T.; Moody, K. Objective assessment of ocular surface response to contact lens wear in presbyopic contact lens wearers of asian descent. Eye Contact Lens 2018, 44, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, C.W.; Rayborn, E. Tribology and the ocular surface. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 16, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Feng, X.; Kong, Q.; Ren, X. Efficient binding paradigm of protein and polysaccharide: Preparation of isolated soy protein-chitosan quaternary ammonium salt complex system and exploration of its emulsification potential. Food Chem. 2023, 407, 135111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luensmann, D.; Jones, L. Albumin adsorption to contact lens materials: A review. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2008, 31, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omali, N.B.; Subbaraman, L.N.; Coles-Brennan, C.; Fadli, Z.; Jones, L.W. Biological and clinical implications of lysozyme deposition on soft contact lenses. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2015, 92, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mession, J.L.; Assifaoui, A.; Lafarge, C.; Saurel, R.; Cayot, P. Protein aggregation induced by phase separation in a pea proteins-sodium alginate-water ternary system. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 28, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.C.; Su, C.Y.; Chang, C.H.; Fang, H.W.; Wei, Y. Correlation between tribological properties and the quantified structural changes of lysozyme on poly (2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) contact lens. Polymers 2020, 12, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Chen, C.; Kang, R.; Jin, Z. Study of mechanical properties and subsurface damage of quartz glass at high temperature based on md simulation. J. Micromechanics Mol. Phys. 2019, 4, 1950003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strozewski, B.; Sly, M.K.; Flores, K.M.; Skemer, P. Viscoplastic rheology of α-quartz investigated by nanoindentation. JGR Solid. Earth 2021, 126, e2021JB022229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkurt Arslan, M.; Brignole-Baudouin, F.; Chardonnet, S.; Pionneau, C.; Blond, F.; Baudouin, C.; Kessal, K. Profiling tear film enzymes reveals major metabolic pathways involved in the homeostasis of the ocular surface. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Artificial Tear Solution Containing 2 mg/mL Lysozyme and 0.2 mg/mL Albumin | Artificial Tear Solution Containing 2 mg/mL Lysozyme and 2 mg/mL Albumin | AA + CRG Care Solution Containing 2 mg of Lysozyme and 0.2 mg/mL of Albumin | AA + CRG Care Solution Containing 2 mg/mL of Lysozyme and 2 mg/mL of Albumin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viscosity (mPa·s) at 19.2 s−1 | 1.15 ± 0.16 | 1.65 ± 0.17 * | 12.23 ± 0.02 *,& | 11.92± 0.05 *,& |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Su, C.-Y.; Yeh, L.-K.; Chang, Y.-C.; Lu, P.-T.; Chang, Y.-H.; Hung, K.-H.; Lai, C.-C.; Fang, H.-W. The Potential Lubricating Mechanism of Alginate Acid and Carrageenan on the Inner Surface of Orthokeratology Lenses. Polymers 2026, 18, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010004

Su C-Y, Yeh L-K, Chang Y-C, Lu P-T, Chang Y-H, Hung K-H, Lai C-C, Fang H-W. The Potential Lubricating Mechanism of Alginate Acid and Carrageenan on the Inner Surface of Orthokeratology Lenses. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Chen-Ying, Lung-Kun Yeh, You-Cheng Chang, Pei-Ting Lu, Yung-Hsiang Chang, Kuo-Hsuan Hung, Chi-Chun Lai, and Hsu-Wei Fang. 2026. "The Potential Lubricating Mechanism of Alginate Acid and Carrageenan on the Inner Surface of Orthokeratology Lenses" Polymers 18, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010004

APA StyleSu, C.-Y., Yeh, L.-K., Chang, Y.-C., Lu, P.-T., Chang, Y.-H., Hung, K.-H., Lai, C.-C., & Fang, H.-W. (2026). The Potential Lubricating Mechanism of Alginate Acid and Carrageenan on the Inner Surface of Orthokeratology Lenses. Polymers, 18(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010004