Synthesis of High-Performance and Biodegradable Polymer Blends Based on Poly(butylene succinate) and Grafted Polyrotaxane via Controlled Reactive Processing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

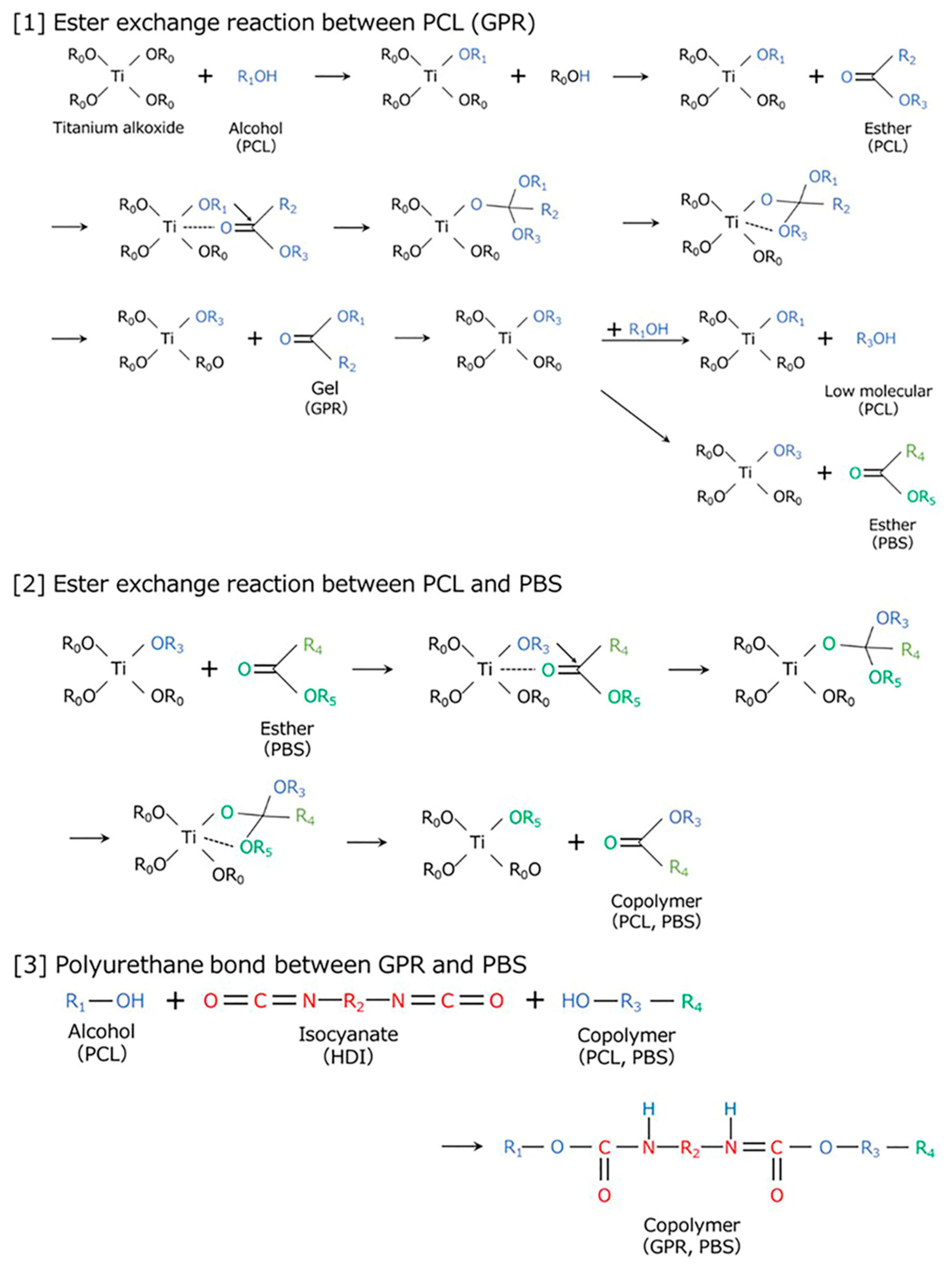

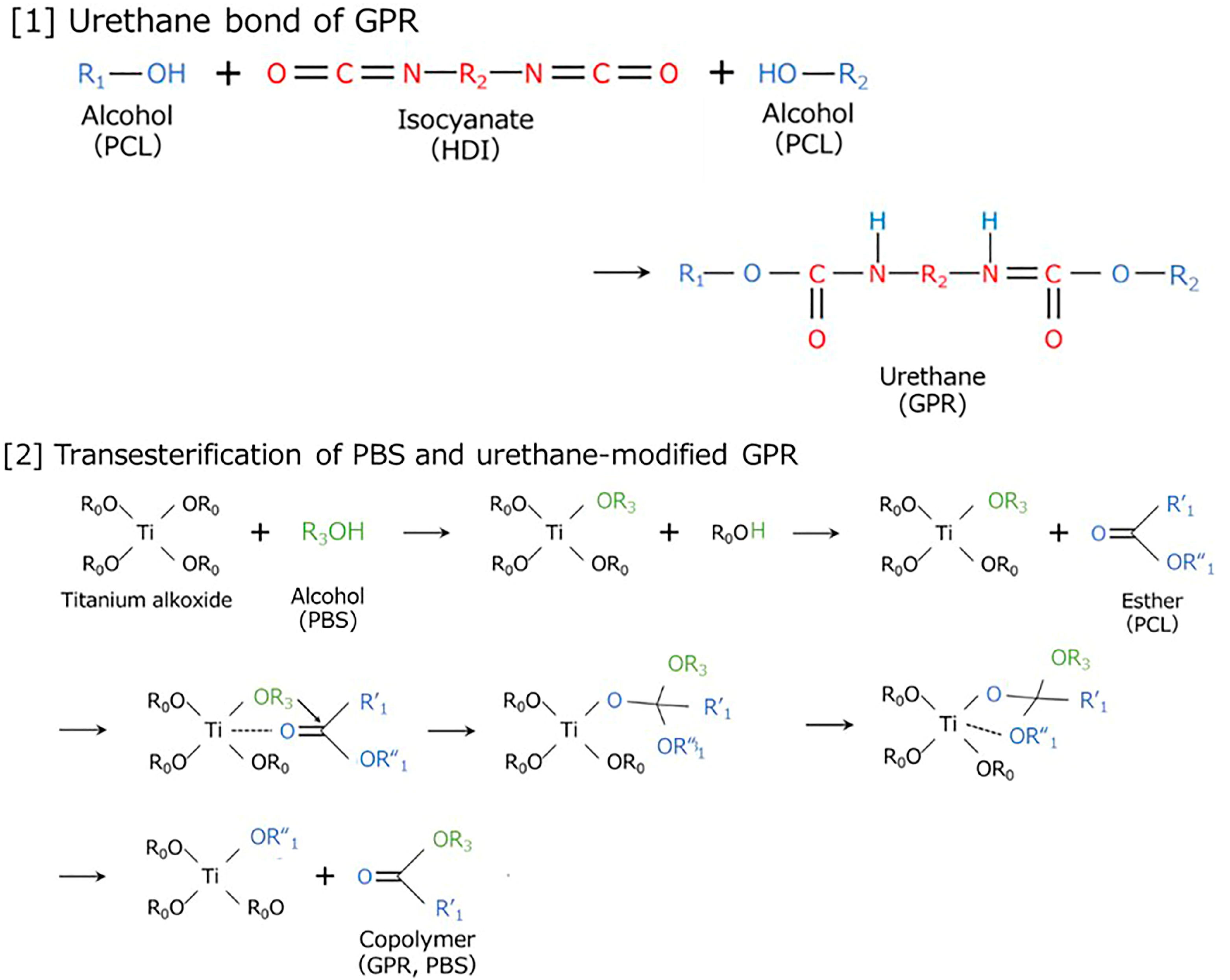

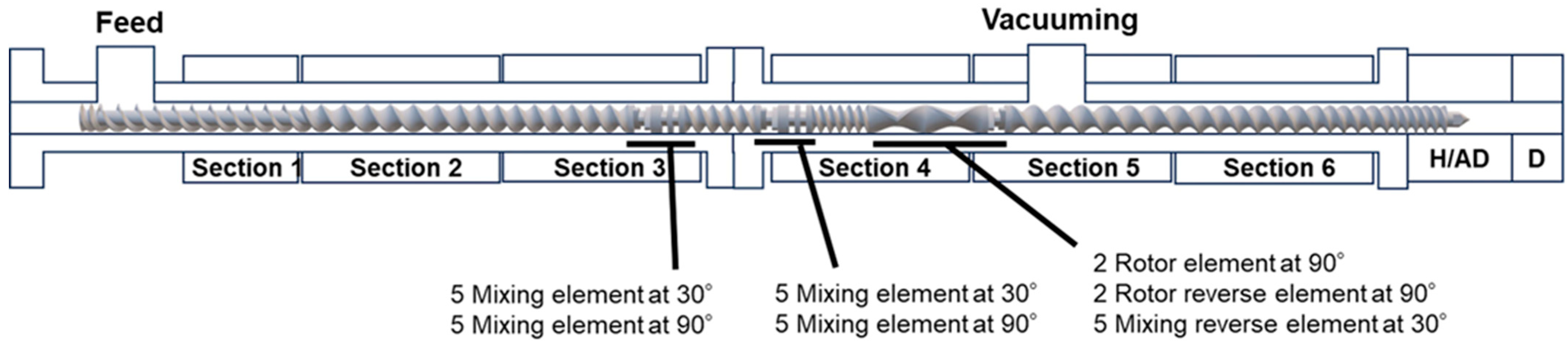

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Characterization

2.3.1. Fourier Transform-Infrared Spectroscopy

2.3.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

2.3.3. Rheological Properties

2.3.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis

2.3.5. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis

2.3.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy

2.4. Mechanical Properties

2.4.1. Impact Strength Test

2.4.2. Morphological Observation of Fractured Surfaces

2.4.3. Tensile Tests

2.5. Gel Fraction Measurement

2.6. Biodegradability Test

2.6.1. Biochemical Oxygen Demand Test

2.6.2. Disintegration Test

3. Results and Discussion

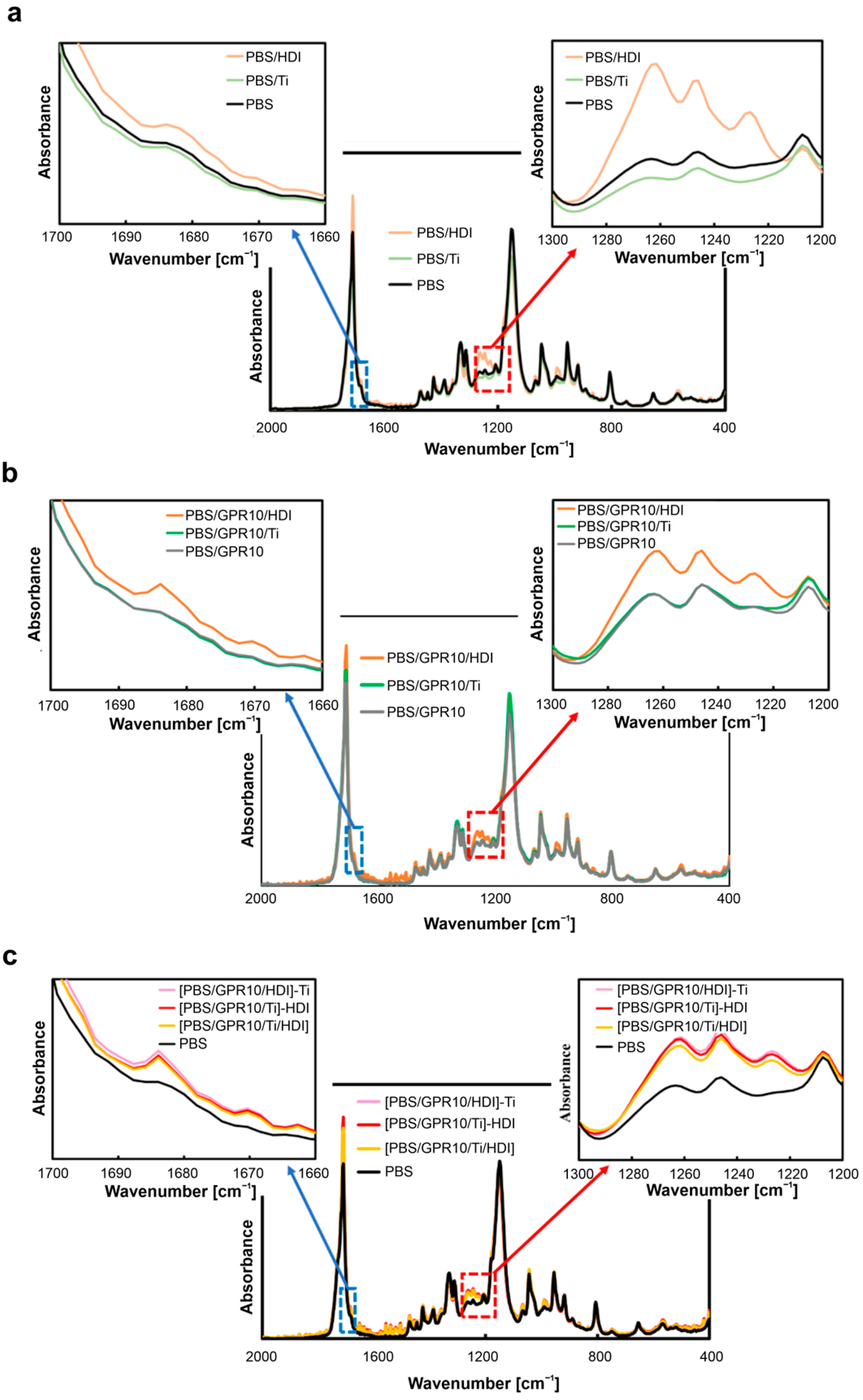

3.1. FT-IR Analysis of Chemical Structures

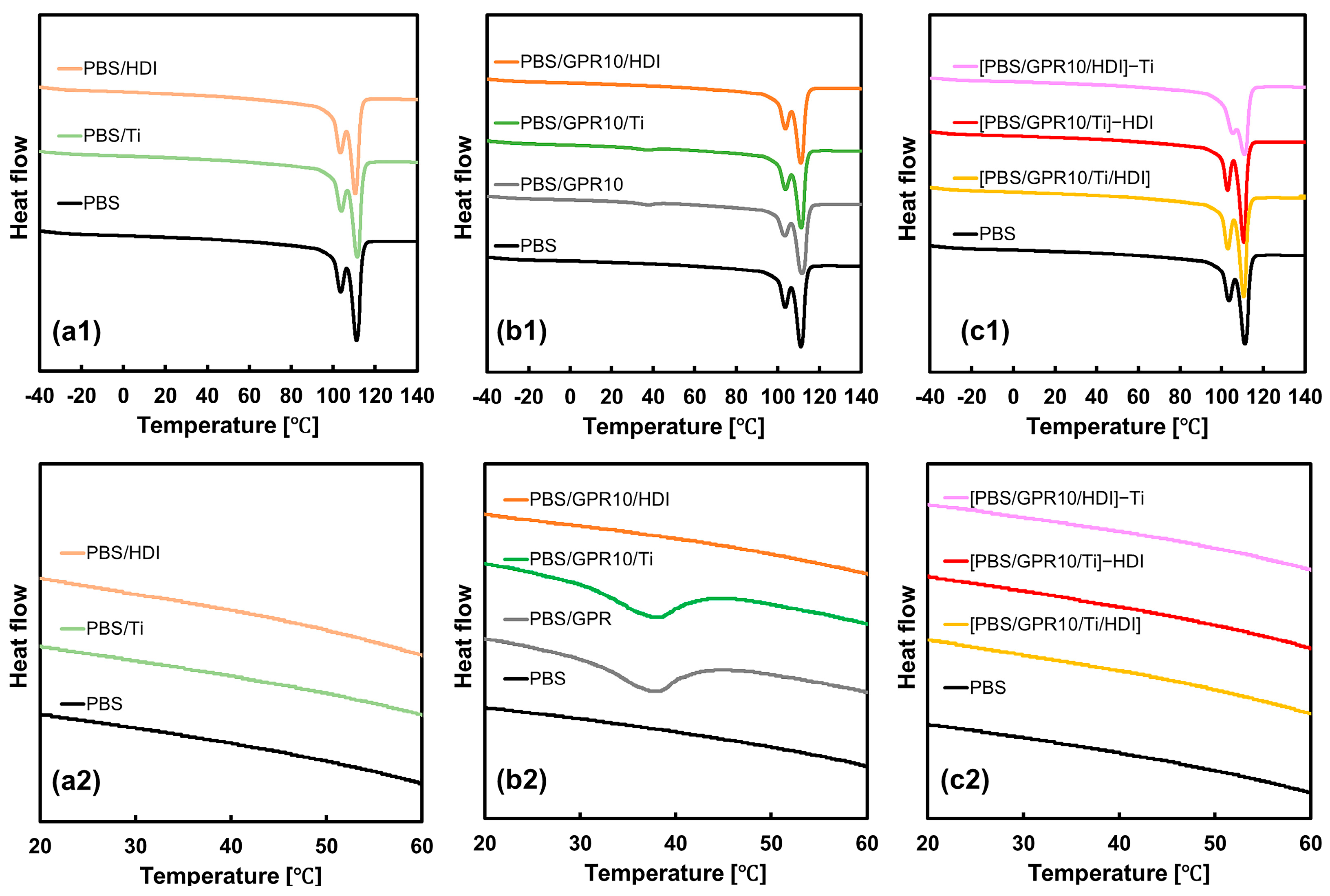

3.2. Thermal Properties Evaluated via DSC

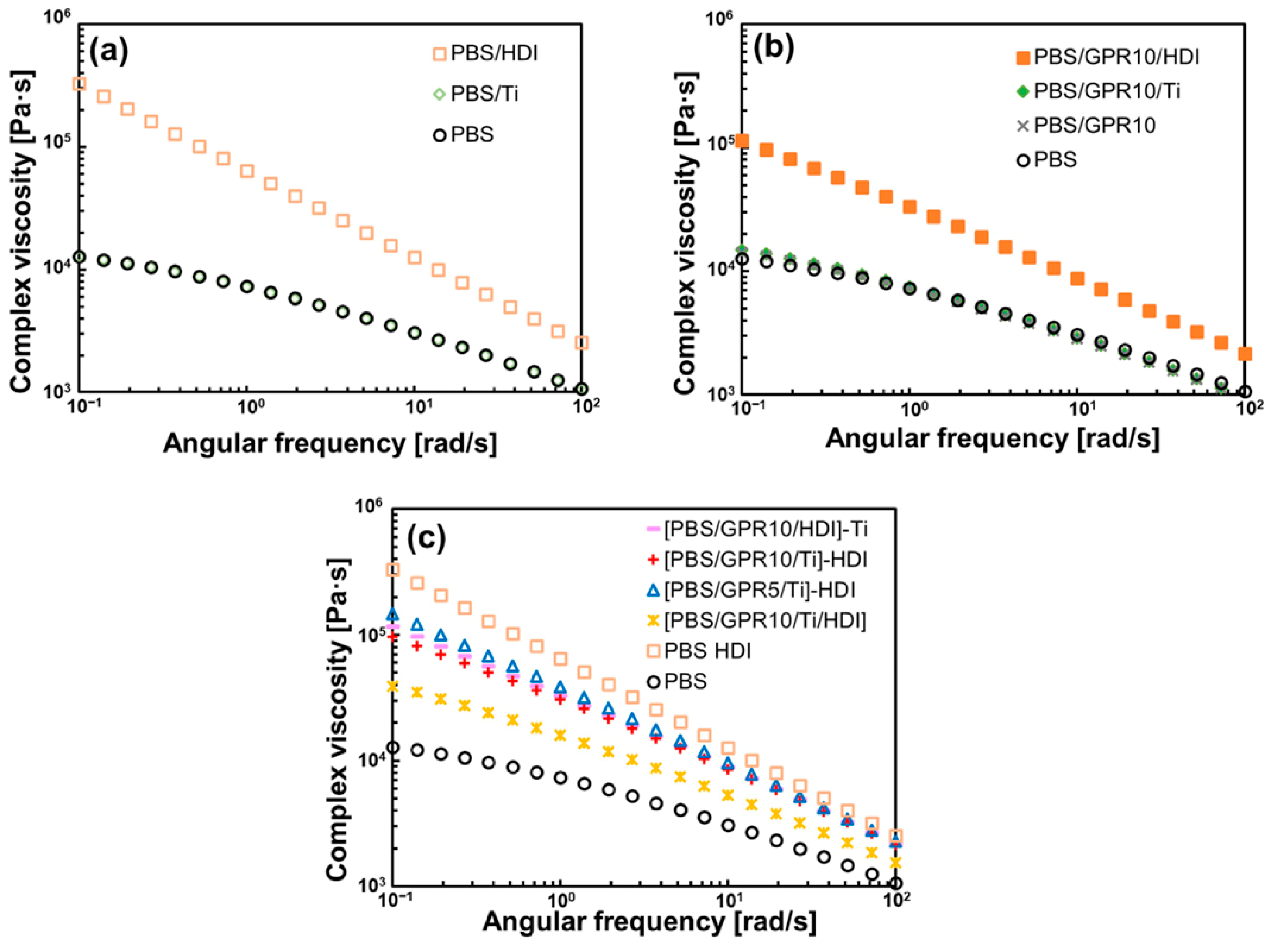

3.3. Rheological Properties Evaluation

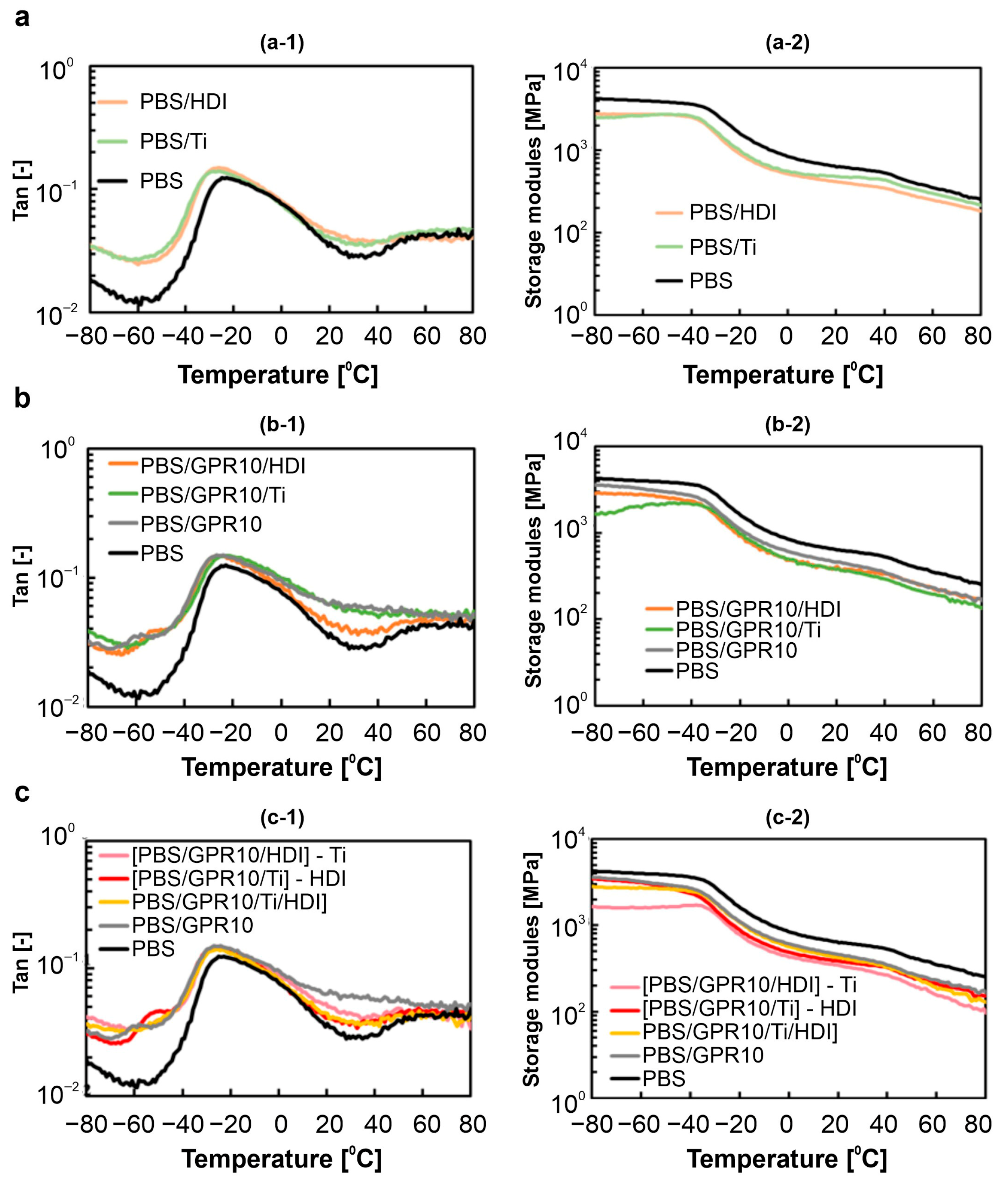

3.4. DMA of Solid-State Viscoelasticity

3.5. Thermal Stability Evaluation via TGA

3.6. Morphology Characterizations via TEM

3.7. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties

3.7.1. Izod Impact Test

3.7.2. Morphological Observation of Impact Fracture Surfaces

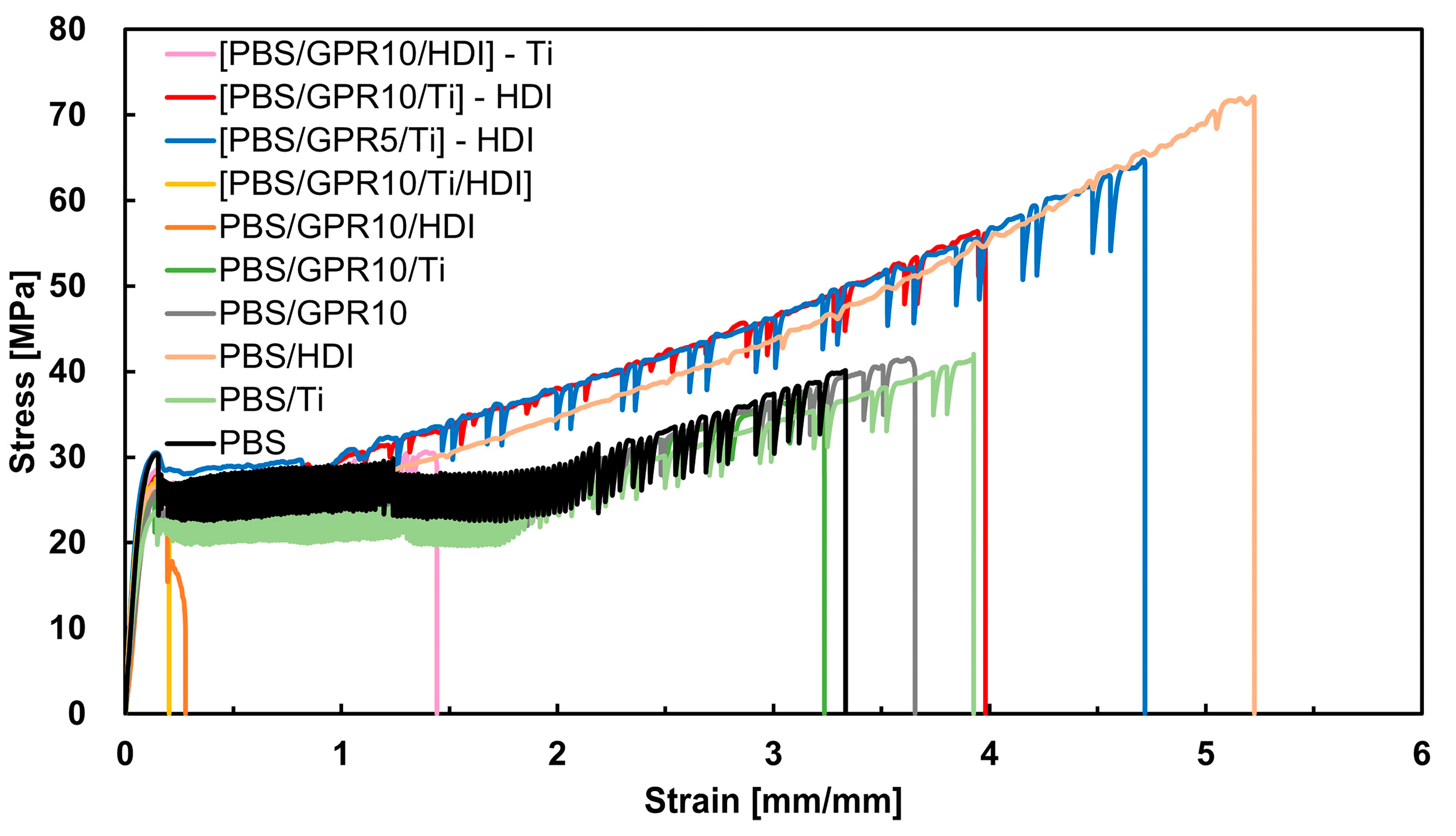

3.7.3. Tensile Test

3.8. Gel Fraction Measurement

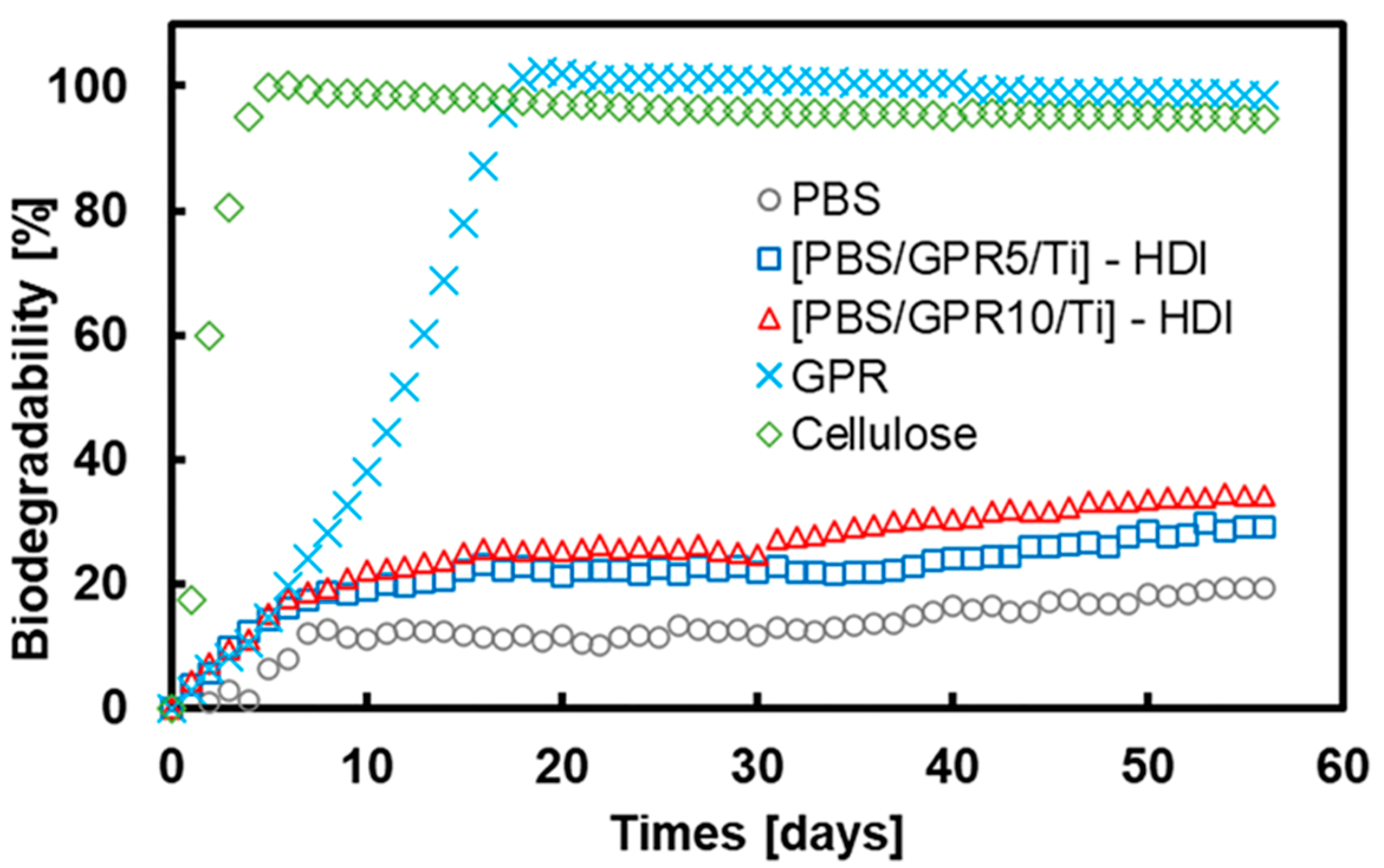

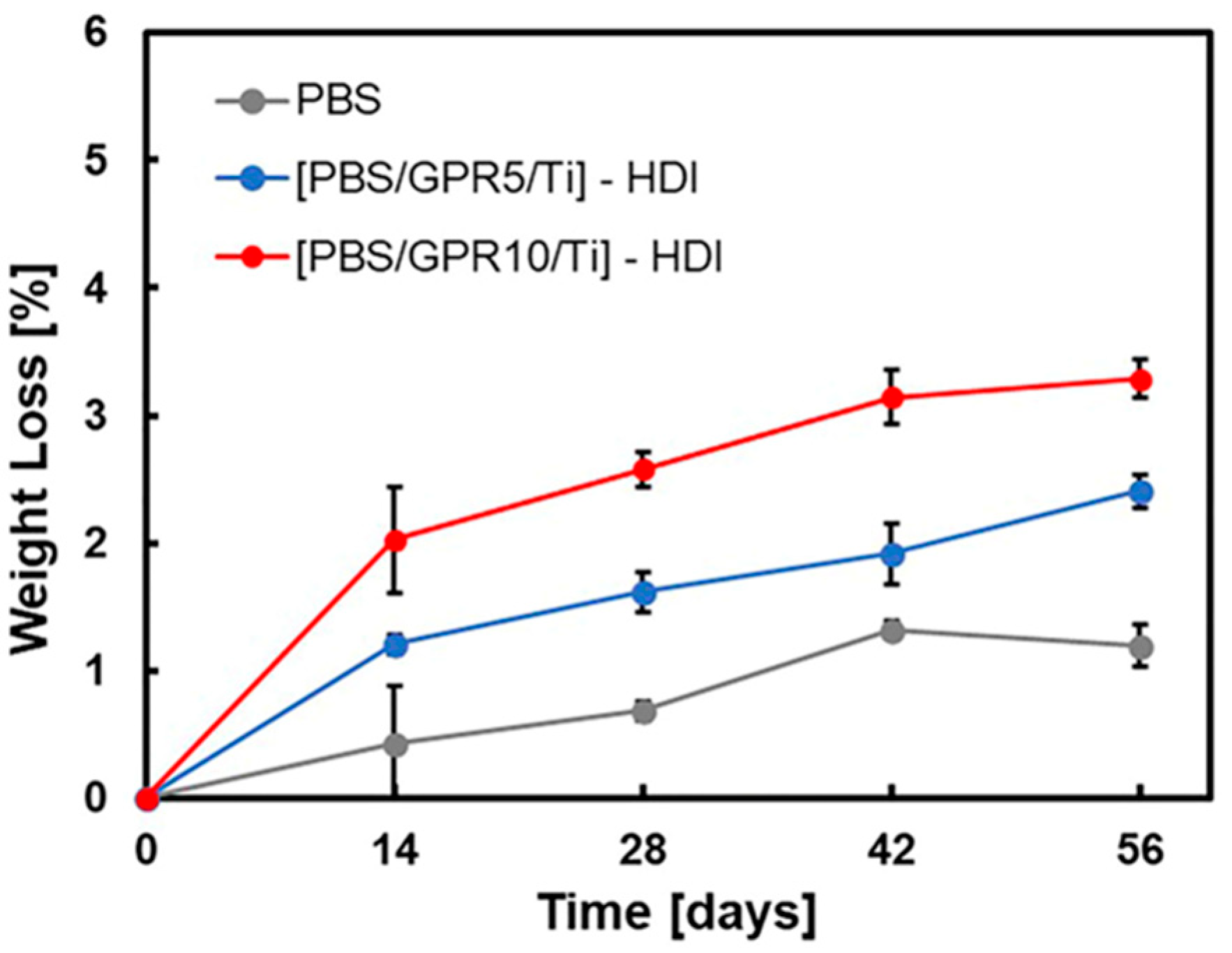

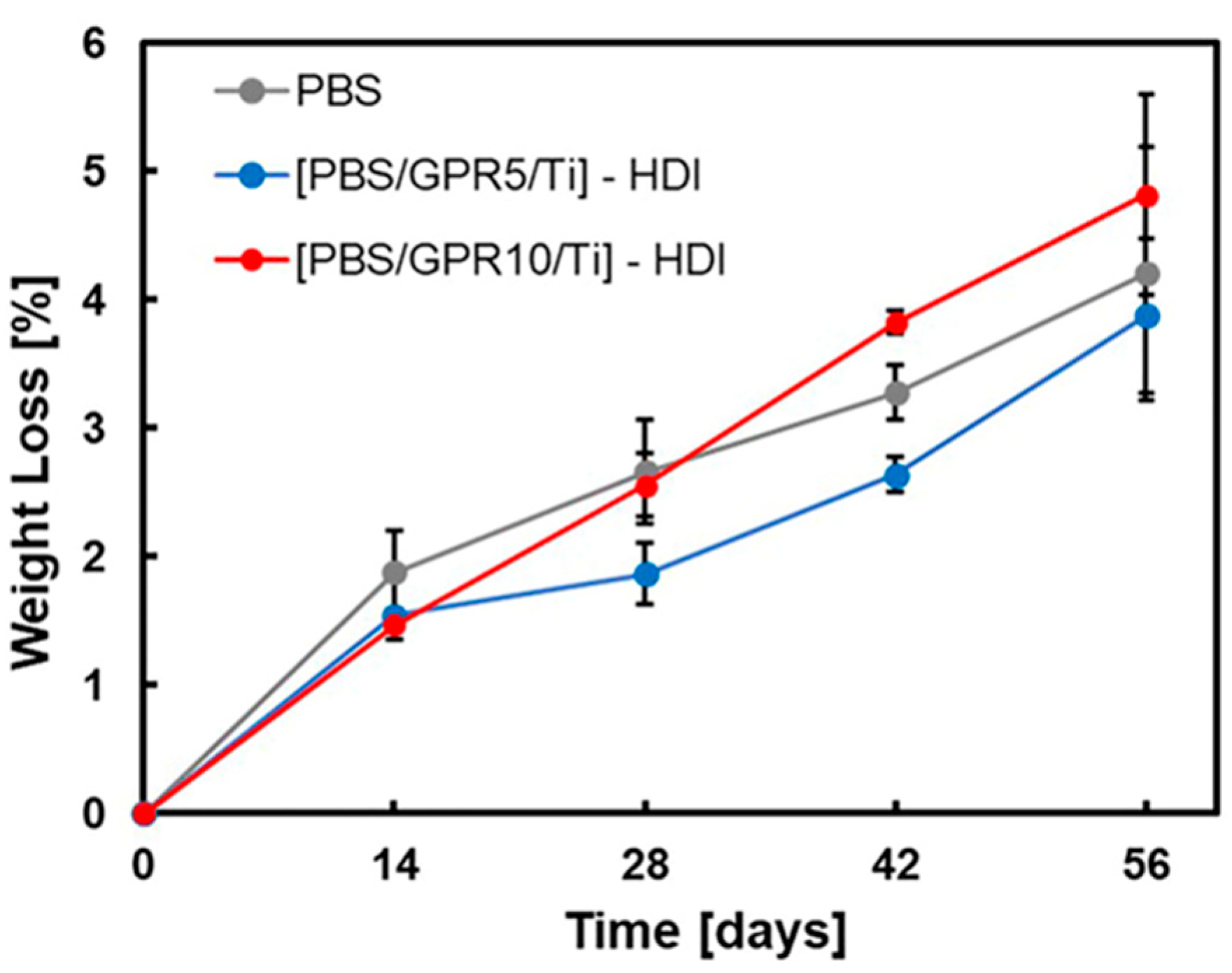

3.9. Biodegradability Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PBS | Poly(butylene succinate) |

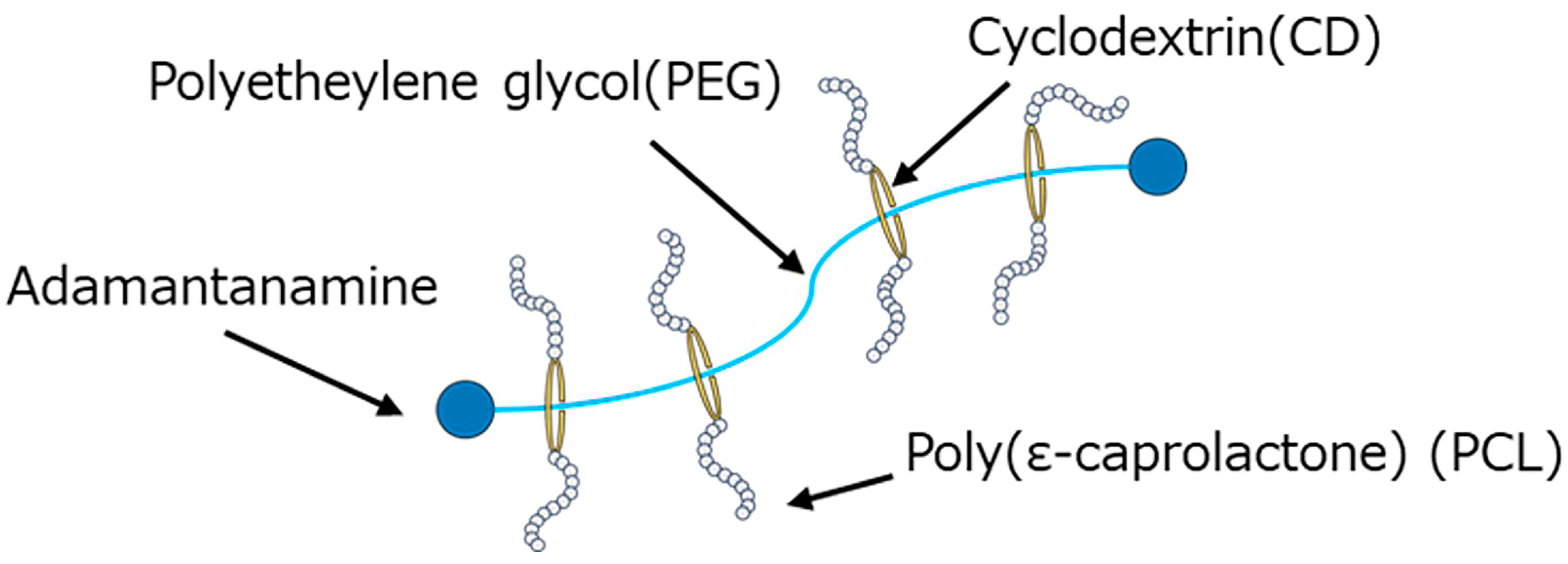

| GPR | Grafted polyrotaxane |

| PR | Polyrotaxane |

| PCL | Polycaprolactone |

| HDI | Hexamethylene diisocyanate |

| E′ | Storage modulus |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| FT-IR | Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy |

| DMA | Dynamic mechanical analysis |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| BOD | Biochemical oxygen demand |

| ThOD | Theoretical oxygen demand |

| Tg | Glass-transition temperature |

| Tm | Melting temperature |

| Wf | Energy to break |

| SDS | Sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| η* | Complex viscosity |

References

- Thomas, D.S.; Kneifel, J.D.; Butry, D.T. The U.S. Plastics Recycling Economy: Current State, Challenges, and Opportunities; NIST Advanced Manufacturing Series; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2021; pp. 100–164. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI). Available online: https://www.meti.go.jp/report/tsuhaku2024/index.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Locock, K.E.S.; Deane, J.; Kosior, E.; Prabaharan, H.; Skidmore, M.; Hutt, O.E. The Recycled Plastics Market: Global Analysis and Trends. Available online: https://www.csiro.au/en/research/environmental-impacts/recycling/plastic-recycling-analysis (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Circular Plastics Alliance (Automotive Working Group). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/43694 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Cho, Y.; Withana, P.A.; Rhee, J.H.; Lim, S.T.; Lim, J.Y.; Park, S.W.; Ok, Y.S. Achieving the sustainable waste management of medical plastic packaging using a life cycle assessment approach. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, S.; Fangueiro, R. Advanced composites in aerospace engineering. In Advanced Composite Materials for Aerospace Engineering, 1st ed.; Rana, S., Fangueiro, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Regional Plastics Outlook for Southeast and East Asia: Current Plastics Use, Waste and End-of-Life Fates; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/regional-plastics-outlook-for-southeast-and-east-asia_5a8ff43c-en.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- PlasticsEurope. Plastics—The Facts. 2020. Available online: https://www.plasticseurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Plastics_the_facts-WEB-2020_versionJun21_final.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Plastics Industry Association (PLASTICS). Available online: https://www.plasticsindustry.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Plastics Europe. Plastics—The Fast Facts. 2024. Available online: https://www.plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-fast-facts-2024/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- OECD. Global Plastics Outlook. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/global-plastics-outlook_aa1edf33-en.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- UNEP. From Pollution to Solution: A Global Assessment of Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution—Synthesis. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/36965 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Valuing Plastic: The Business Case for Measuring, Managing and Disclosing Plastic Use in the Consumer Goods Industry. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/9238 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Wilcox, C.; Van Sebille, E.; Hardesty, B.D. Threat of plastic pollution to seabirds is global, pervasive, and increasing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 11899–11904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- eClinicalMedicine. Plastic Pollution and Health. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 60, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minderoo Foundation. The Price of Plastic Pollution–Social Costs and Corporate Liabilities. Available online: https://cdn.minderoo.org/content/uploads/2022/10/14130457/The-Price-of-Plastic-Pollution.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Dokl, M.; Copot, A.; Krajnc, D.; Fan, Y.V.; Vujanović, A.; Aviso, K.B.; Tan, R.R.; Kravanja, Z.; Čuček, L. Global projections of plastic use, end-of-life fate and potential changes in consumption, reduction, recycling and replacement with Bioplastics to 2050. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 51, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dailin, D.J.; Jusoh, Y.M.; Abd Rasid, Z.I.; Abang Zaidel, D.N.; Ramli, S.; Mata, S.A.; Ahmad, M.Z.; El-Enshasy, H.A. Recent understanding on biodegradation and abiotic degradation of plastics: A review. Bioprocessing 2025, 4, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokiwa, Y.; Calabia, B.P.; Ugwu, C.U.; Aiba, S. Biodegradability of plastics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 3722–3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Zhuang, X.; Tang, Z.; Chen, X. Polylactic acid (PLA): Research, development and industrialization. Biotechnol. J. 2010, 5, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan Nampoothiri, K.M.; Nair, N.R.; John, R.P. An overview of the recent developments in polylactide (PLA) research. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8493–8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Sehgal, R.; Gupta, R. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA): Properties and modifications. Polymer 2021, 212, 123161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.-Y.A.; Chen, C.-L.; Li, L.; Ge, L.; Wang, L.; Razaad, I.M.N.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Mo, Y.; Wang, J.-Y. Start research on biopolymer polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA): A review. Polymers 2014, 6, 706–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajgond, V.; Mohite, A.; More, N.; More, A. Biodegradable polyester-polybutylene succinate (PBS): A review. Polym. Bull. 2023, 81, 5703–5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongtanayut, K.; Thongpin, C.; Santawitee, O. The effect of rubber on morphology, thermal properties and mechanical properties of PLA/NR and PLA/ENR blends. Energy Procedia 2013, 34, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachirahuttapong, S.; Thongpin, C.; Sombatsompop, N. Effect of PCL and compatibility contents on the morphology, crystallization and mechanical properties of PLA/PCL blends. Energy Procedia 2016, 89, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Deng, Y.; Chun Chen, J.C.; Chen, G.Q. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) scaffolds with good mechanical properties and biocompatibility. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 1041–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Reinforcement effect of poly(butylene succinate) (PBS)-grafted cellulose nanocrystal on toughened PBS/polylactic acid blends. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 140, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.-F.; Chen, L.-S.; Jeng, R.-J. Preparation and properties of biodegradable PBS/multi-walled carbon nanotube nanocomposites. Polymer 2008, 49, 4602–4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaluddin, N.; Razaina, M.T.; Mohd Ishak, Z.A. Mechanical and morphology behaviours of polybutylene succinate/thermoplastic polyurethane blend. Procedia Chem. 2016, 19, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khankrua, R.; Pivsa-Art, S.; Hiroyuki, H.; Suttiruengwong, S. Thermal and mechanical properties of biodegradable polyester/silica nanocomposites. Energy Procedia 2013, 34, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.R.; Barlow, J.W. Polymer blends. J. Macromol. Sci. 1980, 18, 109–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, Z.; Kang, H.; Zhang, L. Renewable and super-toughened poly(butylene succinate) with bio-based elastomers: Preparation, compatibility and performances. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 116, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, T. Polyrotaxane and polyrotaxane network: Supramolecular architectures based on the concept of dynamic covalent bond chemistry. Polym. J. 2006, 38, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y. Precise synthesis of polyrotaxane and preparation of supramolecular materials based on its mobility. Polym. J. 2021, 53, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Kato, K.; Mayumi, K.; Yokoyama, H.; Ito, K. Efficient mechanical toughening of polylactic acid without substantial decreases in stiffness and transparency by the reactive grafting of polyrotaxanes. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2019, 93, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kang, H.; Shen, J.; Zhang, L.; Nishi, T.; Ito, K.; Zhao, C.; Coates, P.D. Highly toughened polylactide with novel sliding graft copolymer by in situ reactive compatibilization, crosslinking and chain extension. Polymer 2014, 55, 4313–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigami, A.; Watanabe, K.; Kurose, T.; Ito, H. Physical and morphological properties of tough and transparent PMMA-based blends modified with polyrotaxane. Polymers 2020, 12, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumai, K.; Yamada, Y.; Narita, Y.; Suetsugu, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ito, H. Improvement of the mechanical properties of marine biodegradable polymers by adding polyrotaxane. Seikei-Kakou 2025, 37, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, J.; Kataoka, T.; Ito, K. Preparation of a “sliding graft copolymer”, an organic solvent-soluble polyrotaxane containing mobile side chains, and its application for a crosslinked elastomeric supramolecular film. Soft Matter 2008, 4, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, K.; Inoue, K.; Kudo, M.; Ito, K. Synthesis of graft polyrotaxane by simultaneous capping of backbone and grafting from rings of pseudo-polyrotaxane. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 2573–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Mechanistic details of the titanium-mediated polycondensation reaction of polyesters: A DFT study. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemoto, I.; Kawakami, T.; Taiko, H.; Okumura, M. A quantum chemical study on the polycondensation reaction of polyesters: The mechanism of catalysis in the polycondensation reaction. Polymer 2011, 52, 3443–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, S.; Mori, L.; Cappello, M.; Polacco, G. Glycidyl azide-butadiene block copolymers: Synthesis from the homopolymers and a chain extender. Propellant Explos. Pyrotech. 2017, 42, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, N.; Daimon, H.; Kumanotani, J. Polyesters containing ring units in main chains. I. Preparation and stereochemistry of monomers and polyesters. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Chem. Ed. 1980, 18, 1665–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuokkanen, T.; Vähäoja, P.; Välimäki, I.; Lauhanen, R. Suitability of the respirometric BOD OxiTop method for determining the biodegradability of oils in ground water using forestry hydraulic oils as model compounds. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2004, 84, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokkola, H.; Heponiemi, A.; Pesonen, J.; Kuokkanen, T.; Lassi, U. Reliability of biodegradation measurements for inhibitive industrial wastewaters. ChemEngineering 2022, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, H.; Osaka, N.; Kikuchi, T.; Tanaka, K. Development and multi-site validation of a rapid biodegradation test method for seafloor conditions using extracted seawater with microbes from sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 1002, 180597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, S.; Potolincă, O. Synthesis of polyether urethanes with a pyrimidine ring in the main chain. Des. Monomers Polym. 2010, 13, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thébault, M.; Pizzi, A.; Santiago-Medina, F.J.; Al-Marzouki, F.M.; Abdalla, S. Isocyanate-free polyurethanes by coreaction of condensed tannins with aminated tannins. J. Renew. Mater. 2017, 5, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulyanska, Y.; Cruz-Lopes, L.; Esteves, B.; Guiné, R.; Domingos, I. FTIR monitoring of polyurethane foams derived from acid-liquefied and base-liquefied polyols. Polymers 2024, 16, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srichatrapimuk, V.W. Infrared thermal analysis of polyurethane block polymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1978, 22, 2967–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ren, Z.; He, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, C. FTIR spectroscopic characterization of polyurethane-urea model hard segments (PUUMHS) based on three diamine chain extenders. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2007, 66, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılgör, I.; Yılgör, E.; Güler, I.G.; Ward, T.C.; Wilkes, G.L. FTIR investigation of the influence of diisocyanate symmetry on the morphology development in model segmented polyurethanes. Polymer 2006, 47, 4105–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Jia, Y.; He, A. Preparation of higher molecular weight poly (l-lactic acid) by chain extension. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2013, 2013, 315917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matumba, K.I.; Motloung, M.P.; Ojijo, V.; Ray, S.S.; Sadiku, E.R. Investigation of the effects of chain extender on material properties of PLA/PCL and PLA/PEG blends: Comparative study between polycaprolactone and polyethylene glycol. Polymers 2023, 15, 2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-Y.; Lee, C.-H.; Cho, S.; Lee, D.-H.; Yoon, K.-B. Enhancement of physical properties of thermoplastic polyether-ester elastomer by reactive extrusion with chain extender. Polym. Bull. 2011, 66, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J.; Jing, B.; Zou, X. High melt viscosity, low yellowing, strengthened and toughened biodegradable polyglycolic acid via chain extension of aliphatic diisocyanate and epoxy oligomer. React. Funct. Polym. 2024, 200, 105926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, G.J.; Yoo, J.H.; Lee, J.W. Effect of long-chain branches of polypropylene on rheological properties and foam-extrusion performances. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 96, 1793–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Shekh, M.I.; Cui, S.; Stadler, F.J. Rheological behavior of blends of metallocene catalyzed long-chain branched polyethylenes. Part I: Shear rheological and thermorheological behavior. Polymers 2021, 13, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, P.; Schweissinger, E.; Maier, S.; Hilf, S.; Sirak, S.; Martini, A. Effect of polymer structure and chemistry on viscosity index, thickening efficiency, and traction coefficient of lubricants. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 359, 119215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dally, J.W.; Shukla, A. Energy loss in Homalite 100 during crack propagation and arrest. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1980, 13, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockey, D.A.; Seaman, L.; Curran, D.R. Computation of crack propagation and arrest by simulating microfracturing at the crack tip. In Fast Fracture and Crack Arrest; Hahn, G.T., Kanninen, M.F., Eds.; ASTM Special Technical Publication 627; ASTM International: Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1977; pp. 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-Q.; Fan, Z.; Gupta, C.; Siavoshani, A.; Smith, T. Fracture behavior of polymers in plastic and elastomeric states. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 3875–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinloch, A.J.; Young, R.J. Fracture of polymers. In Fracture Behaviour of Polymers; Kinloch, A.J., Ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | PBS [wt%] | GPR [wt%] | Ti [phr] | HDI [phr] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | 100 | - | - | - |

| PBS/Ti | 100 | - | 0.1 | - |

| PBS/HDI | 100 | - | - | 1 |

| PBS/GPR10 | 90 | 10 | - | - |

| PBS/GPR5/Ti | 95 | 5 | 0.1 | - |

| PBS/GPR10/Ti | 90 | 10 | 0.1 | - |

| PBS/GPR10/HDI | 90 | 10 | - | 1 |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti/HDI] | 90 | 10 | 0.1 | 1 |

| Code | Ti [phr] | HDI [phr] | PBS/GPR5/Ti [wt%] | PBS/GPR10/Ti [wt%] | PBS/GPR10/HDI [wt%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [PBS/GPR5/Ti]-HDI | - | 1 | 100 | - | - |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti]-HDI | - | 1 | - | 100 | - |

| [PBS/GPR10/HDI]-Ti | 0.1 | - | - | - | 100 |

| Section | Section 1 | Section 2 | Section 3 | Section 4 | Section 5 | Section 6 | H/AD | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature [°C] | 40 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 |

| Code | Temperature [°C] at Section 4 | Pressure [MPa] at H/AD |

|---|---|---|

| PBS | 142 | 5.0 |

| PBS/Ti | 142 | 5.0 |

| PBS/HDI | 143 | 7.2 |

| PBS/GPR10 | 136 | 4.9 |

| PBS/GPR10/Ti | 138 | 4.9 |

| PBS/GPR10/HDI | 138 | 5.9 |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti/HDI] | 135 | 5.5 |

| [PBS/GPR5/Ti]-HDI | 135 | 6.2 |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti]-HDI | 135 | 5.2 |

| [PBS/GPR10/HDI]-Ti | 135 | 5.9 |

| Code | PBS | GPR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tm [°C] | χc [%] | Tg [°C] | Tm [°C] | ΔHm [J/g] | |

| PBS | 112.9 | 59.3 | −31.7 | - | - |

| PBS/Ti | 111.1 | 59.0 | −33.4 | - | - |

| PBS/HDI | 109.5 | 54.8 | −33.4 | - | - |

| PBS/GPR10 | 112.2 | 58.8 | −31.1 | 37.9 | 3.6 |

| PBS/GPR10/Ti | 111.6 | 59.8 | −32.4 | 37.7 | 3.2 |

| PBS/GPR10/HDI | 111.0 | 54.5 | −32.2 | - | - |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti/HDI] | 110.8 | 60.8 | −34.2 | - | - |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti]-HDI | 111.6 | 55.9 | −34.2 | - | - |

| [PBS/GPR10/HDI]-Ti | 110.6 | 57.4 | −33.5 | - | - |

| Code | PBS Tg [°C] | GPR Tg [°C] |

|---|---|---|

| PBS | −25.7 | - |

| PBS/Ti | −28.6 | - |

| PBS/HDI | −26.2 | - |

| PBS/GPR10 | −24.9 | −56.1 |

| PBS/GPR10/Ti | −25.4 | −51.0 |

| PBS/GPR10/HDI | −25.2 | −52.5 |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti/HDI] | −24.3 | −53.7 |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti]-HDI | −29.7 | −49.4 |

| [PBS/GPR10/HDI]-Ti | −27.1 | −51.6 |

| Code | Td,5% [°C] | Tmax [°C] |

|---|---|---|

| PBS | 355.1 | 413.5 |

| GPR | 336.7 | 380.1 |

| PBS/Ti | 357.9 | 414.8 |

| PBS/HDI | 356.3 | 412.8 |

| PBS/GPR10 | 357.2 | 416.1 |

| PBS/GPR10/Ti | 353.0 | 416.8 |

| PBS/GPR10/HDI | 355.1 | 413.1 |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti/HDI] | 354.5 | 413.2 |

| [PBS/GPR5/Ti]–HDI | 357.1 | 414.5 |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti]–HDI | 356.3 | 413.4 |

| [PBS/GPR10/HDI]–Ti | 355.1 | 413.1 |

| Code | Impact Strength [kJ/m2] |

|---|---|

| PBS | 10.1 |

| PBS/Ti | 11.5 |

| PBS/HDI | 12.3 |

| PBS/GPR10 | 14.0 |

| PBS/GPR10/Ti | 14.3 |

| PBS/GPR10/HDI | 12.3 |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti/HDI] | 11.2 |

| [PBS/GPR5/Ti]-HDI | 61.6 |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti]-HDI | 75.9 |

| [PBS/GPR10/HDI]-Ti | 43.5 |

| Code | εb [mm/mm] | σb [MPa] | σy [MPa] | E [MPa] | Wf [MJ/m3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | 3.35 | 38.4 | 28.0 | 423 | 89.8 |

| PBS/Ti | 3.85 | 40.7 | 23.6 | 267 | 106 |

| PBS/HDI | 5.10 | 68.8 | 26.0 | 321 | 193 |

| PBS/GPR10 | 3.68 | 40.9 | 25.3 | 351 | 103 |

| PBS/GPR10/Ti | 3.07 | 35.0 | 23.3 | 287 | 78.3 |

| PBS/GPR10/HDI | 0.27 | 23.6 | 23.2 | 261 | 4.85 |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti/HDI] | 0.20 | 27.6 | 26.8 | 364 | 4.23 |

| [PBS/GPR5/Ti]-HDI | 4.53 | 64.0 | 29.4 | 480 | 188 |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti]-HDI | 3.92 | 56.2 | 26.8 | 437 | 149 |

| [PBS/GPR10/HDI]-Ti | 1.51 | 32.2 | 28.5 | 295 | 41.0 |

| Code | Gel Fraction [%] | Impact Strength [kJ/m2] | η [Pa·s] @1 rad/s | Wf [kJ/m2] | εb [mm/mm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | 0 | 10.1 | 7350.7 | 89.8 | 3.35 |

| PBS/Ti | 0 | 11.5 | 7280.6 | 106 | 3.85 |

| PBS/HDI | 0 | 12.3 | 64,433 | 193 | 5.10 |

| PBS/GPR10 | 0 | 14.0 | 7372.1 | 103 | 3.68 |

| PBS/GPR10/Ti | 0 | 14.3 | 7590.5 | 78.3 | 3.07 |

| PBS/GPR10/HDI | 7.77 | 12.3 | 33,917 | 4.85 | 0.27 |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti/HDI] | 9.83 | 11.2 | 15,895 | 4.23 | 0.20 |

| [PBS/GPR5/Ti]-HDI | 0.99 | 61.6 | 38,481 | 188 | 4.53 |

| [PBS/GPR10/Ti]-HDI | 3.07 | 75.9 | 30,619 | 149 | 3.92 |

| [PBS/GPR10/HDI]-Ti | 7.31 | 43.5 | 32,647 | 41.0 | 1.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kitada, Y.; Ishigami, A.; Kobayashi, Y.; Suetsugu, Y.; Taguchi, H.; Kikuchi, T.; Ito, H. Synthesis of High-Performance and Biodegradable Polymer Blends Based on Poly(butylene succinate) and Grafted Polyrotaxane via Controlled Reactive Processing. Polymers 2026, 18, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010038

Kitada Y, Ishigami A, Kobayashi Y, Suetsugu Y, Taguchi H, Kikuchi T, Ito H. Synthesis of High-Performance and Biodegradable Polymer Blends Based on Poly(butylene succinate) and Grafted Polyrotaxane via Controlled Reactive Processing. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleKitada, Yuki, Akira Ishigami, Yutaka Kobayashi, Yoshiyuki Suetsugu, Hironori Taguchi, Takako Kikuchi, and Hiroshi Ito. 2026. "Synthesis of High-Performance and Biodegradable Polymer Blends Based on Poly(butylene succinate) and Grafted Polyrotaxane via Controlled Reactive Processing" Polymers 18, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010038

APA StyleKitada, Y., Ishigami, A., Kobayashi, Y., Suetsugu, Y., Taguchi, H., Kikuchi, T., & Ito, H. (2026). Synthesis of High-Performance and Biodegradable Polymer Blends Based on Poly(butylene succinate) and Grafted Polyrotaxane via Controlled Reactive Processing. Polymers, 18(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010038