Fabrication of a Superhydrophobic Surface via Wet Etching of a Polydimethylsiloxane Micropillar Array

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Fabrication of Micropillar Array via Photolithography

2.3. Fabrication of Micropillar Array via CNC

2.4. Wet Chemical Etching of PDMS Micropillars

2.5. Characterization and Contact Angle Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

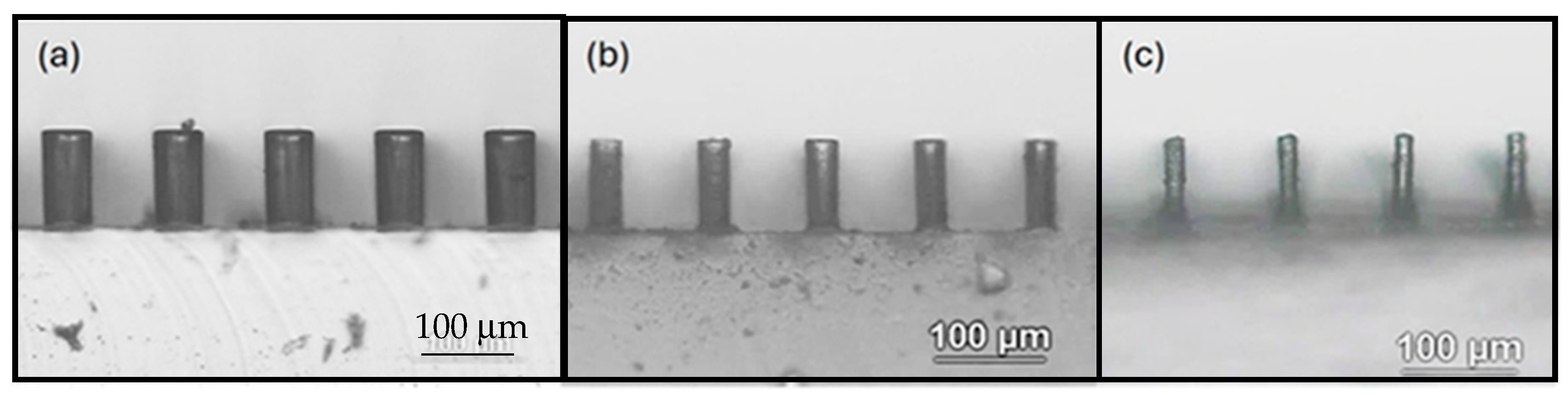

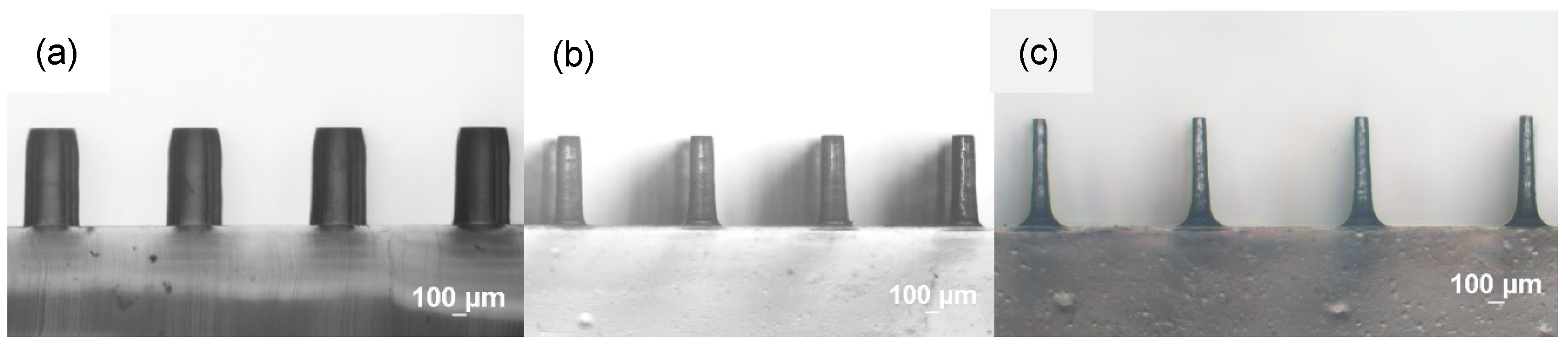

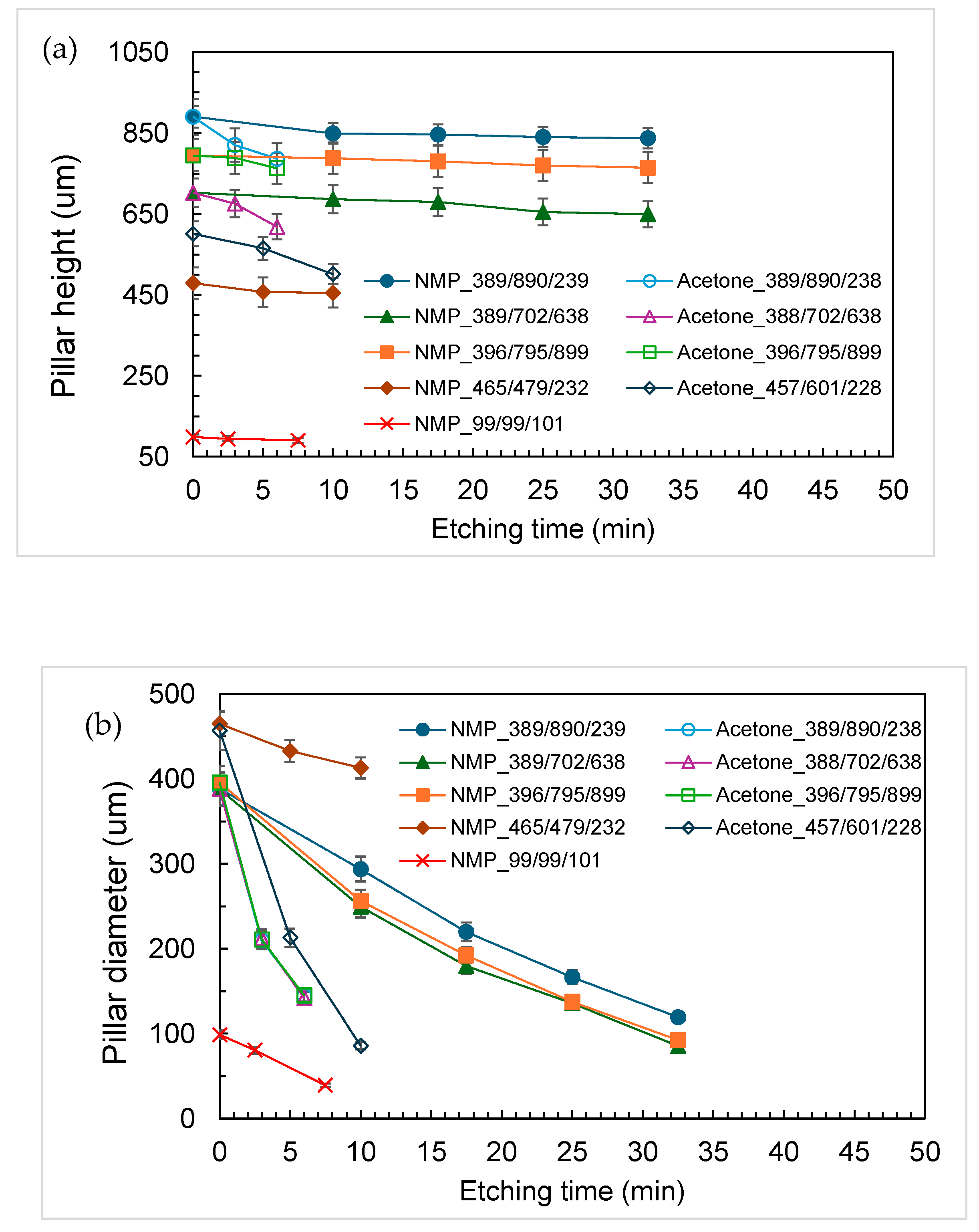

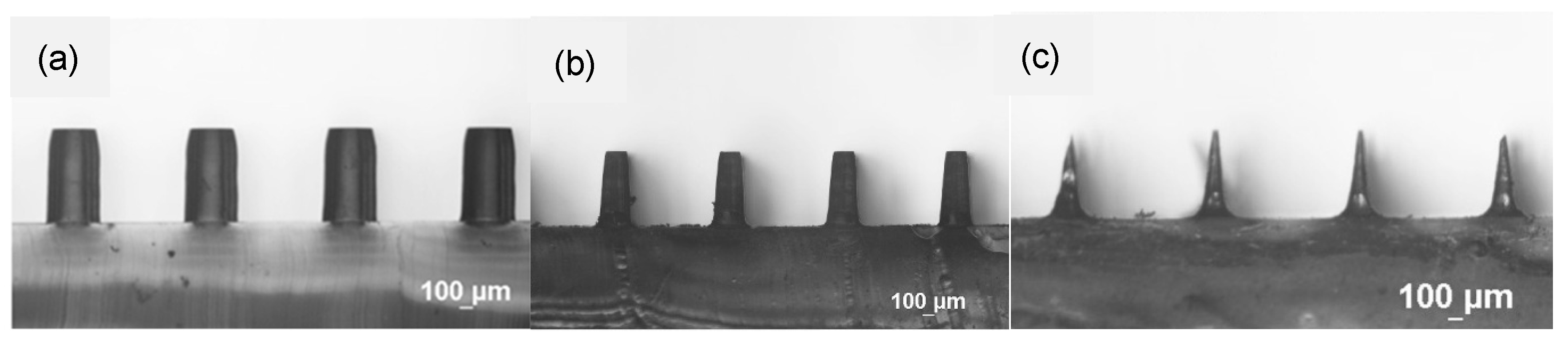

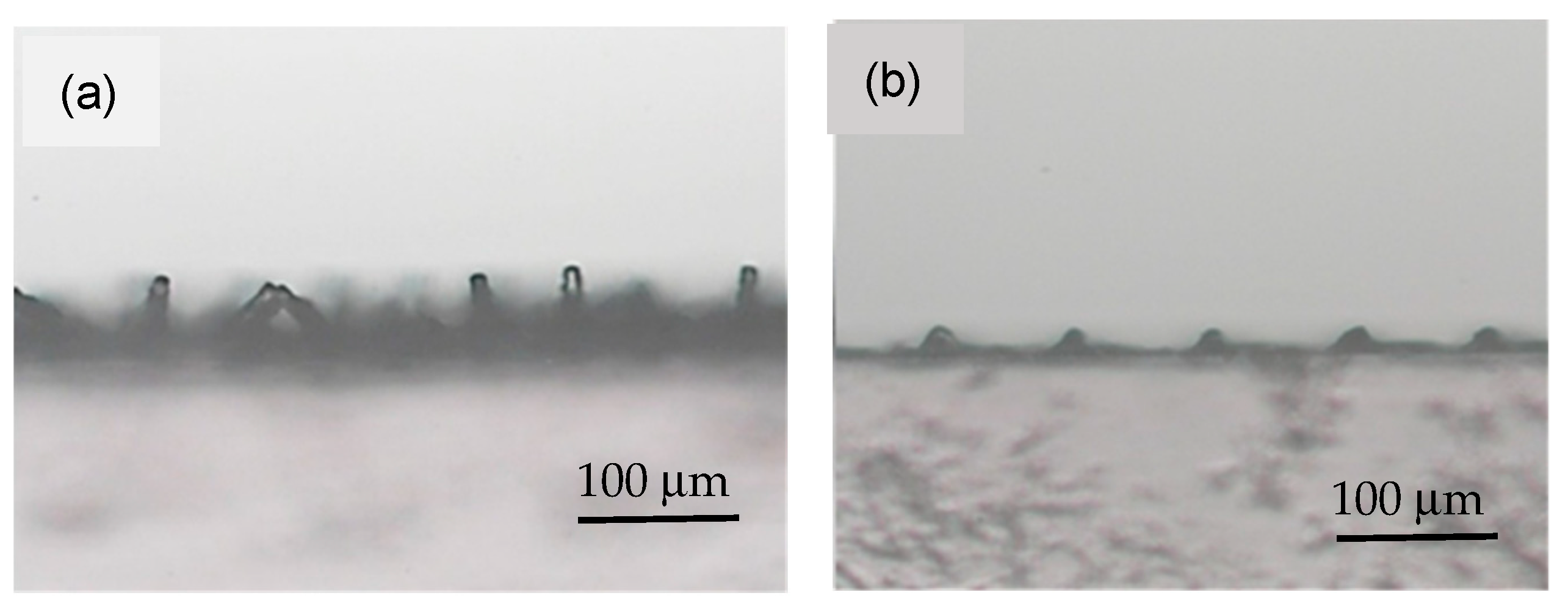

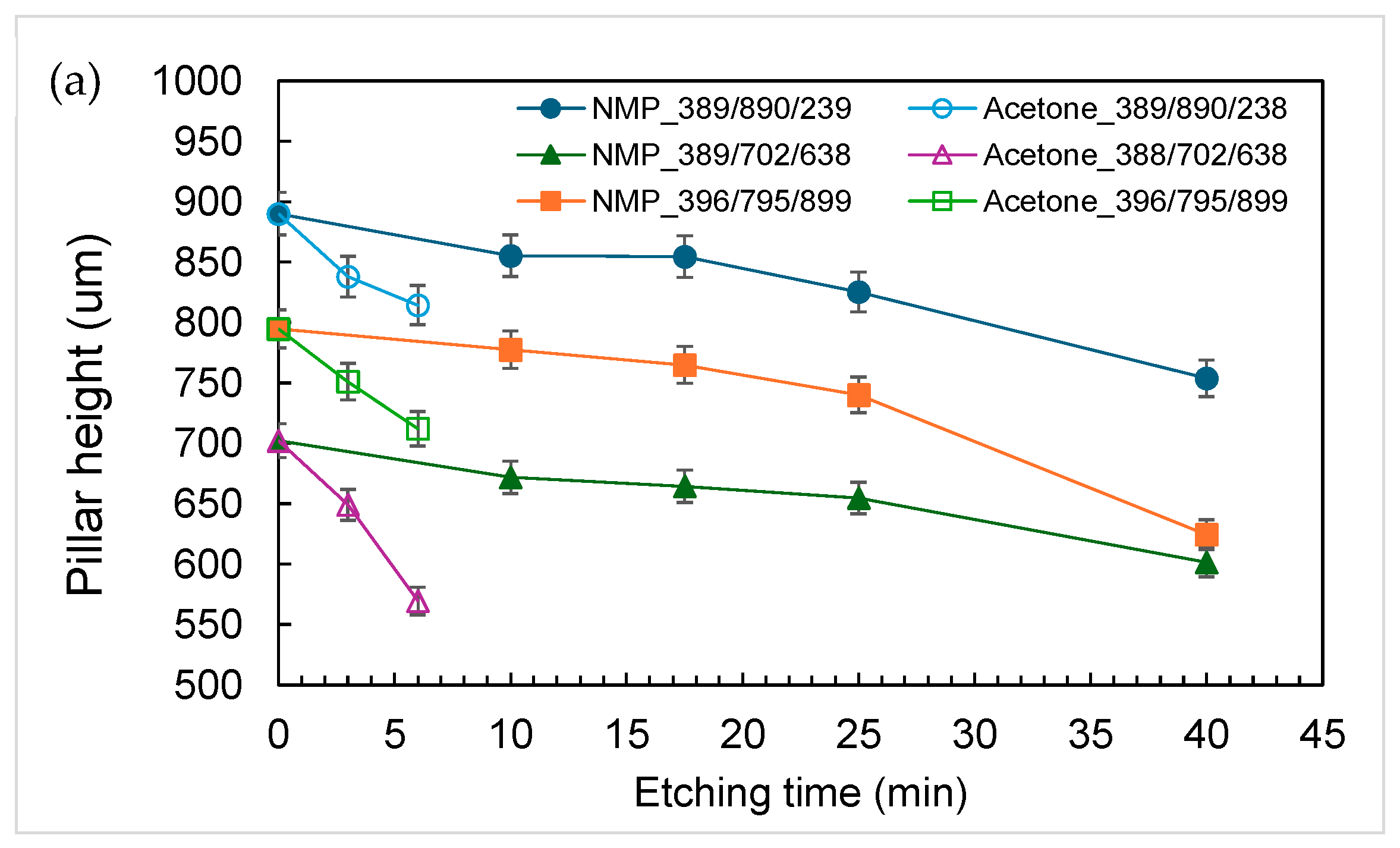

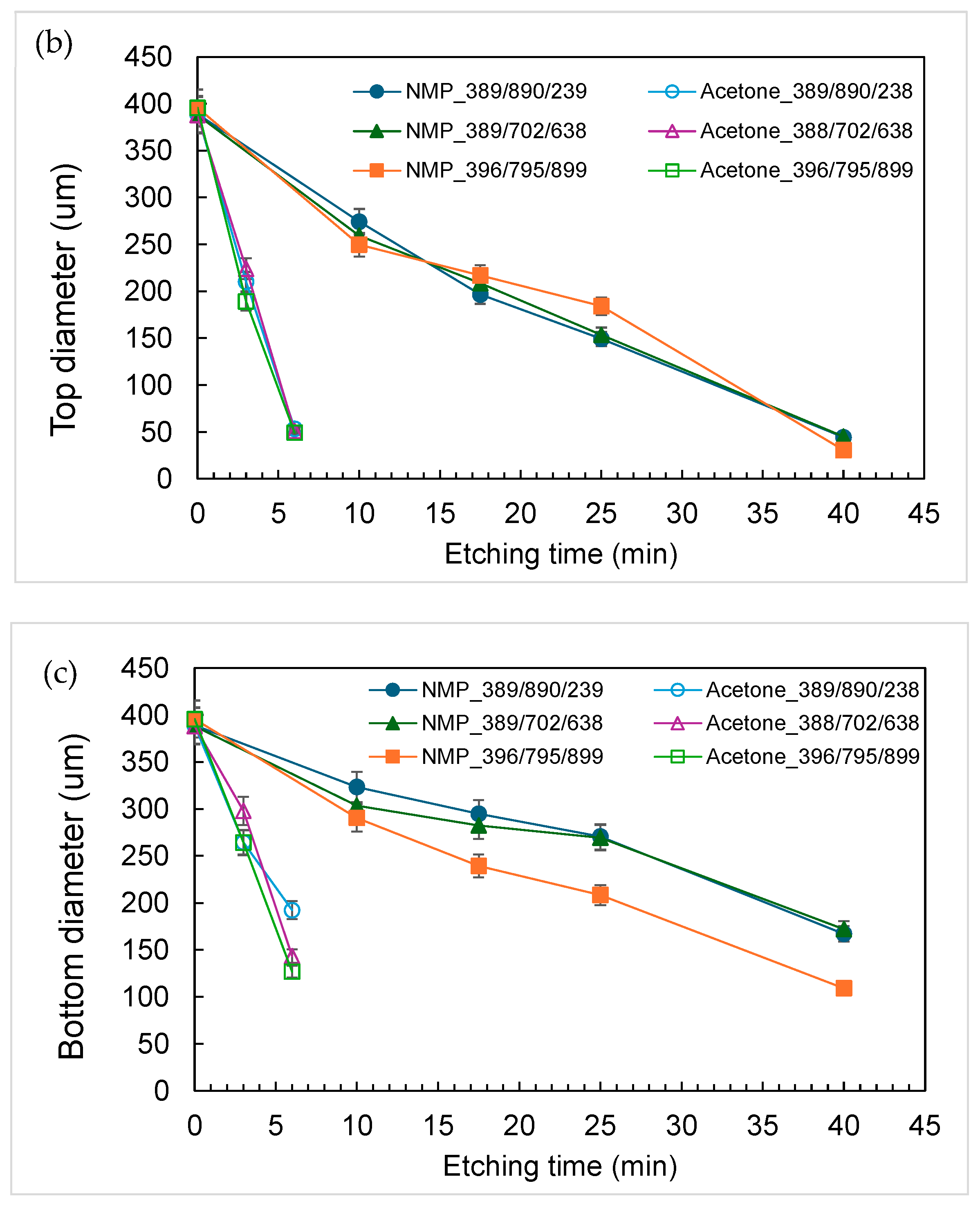

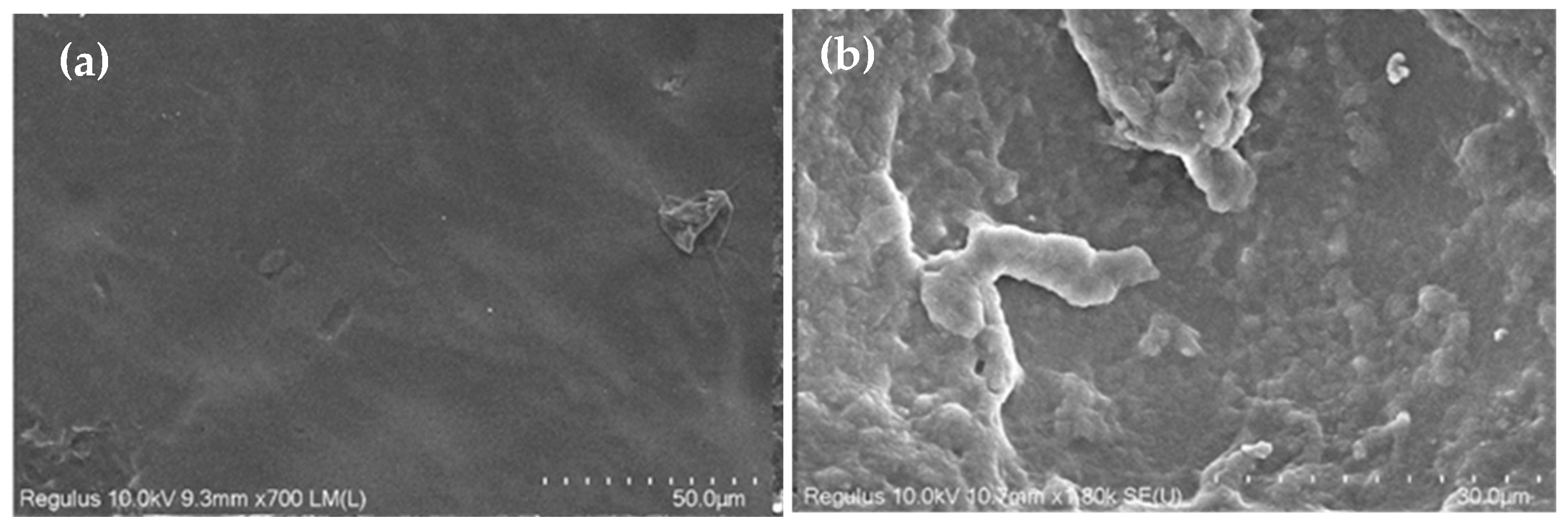

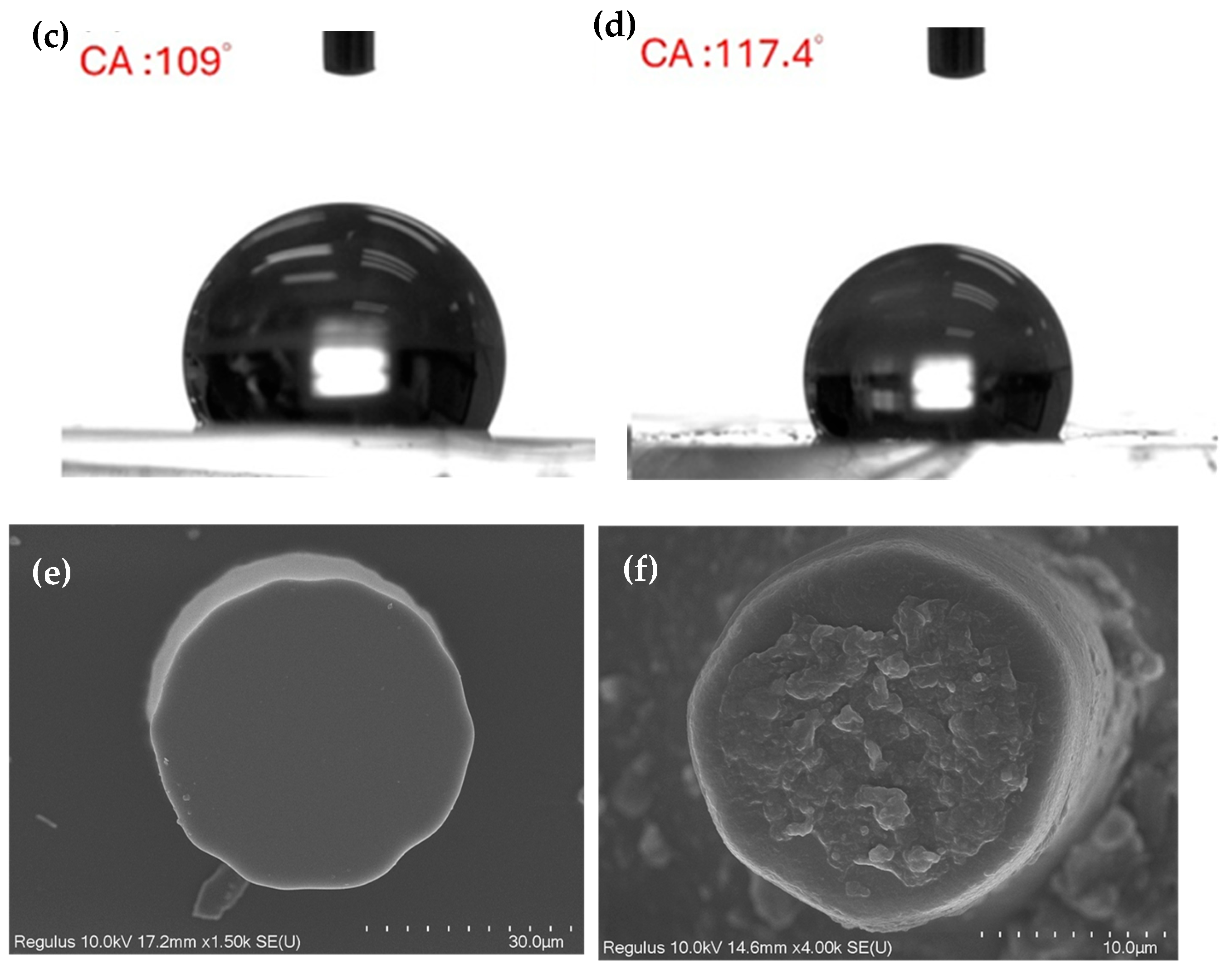

3.1. Characterization of Etching Micropillar Array

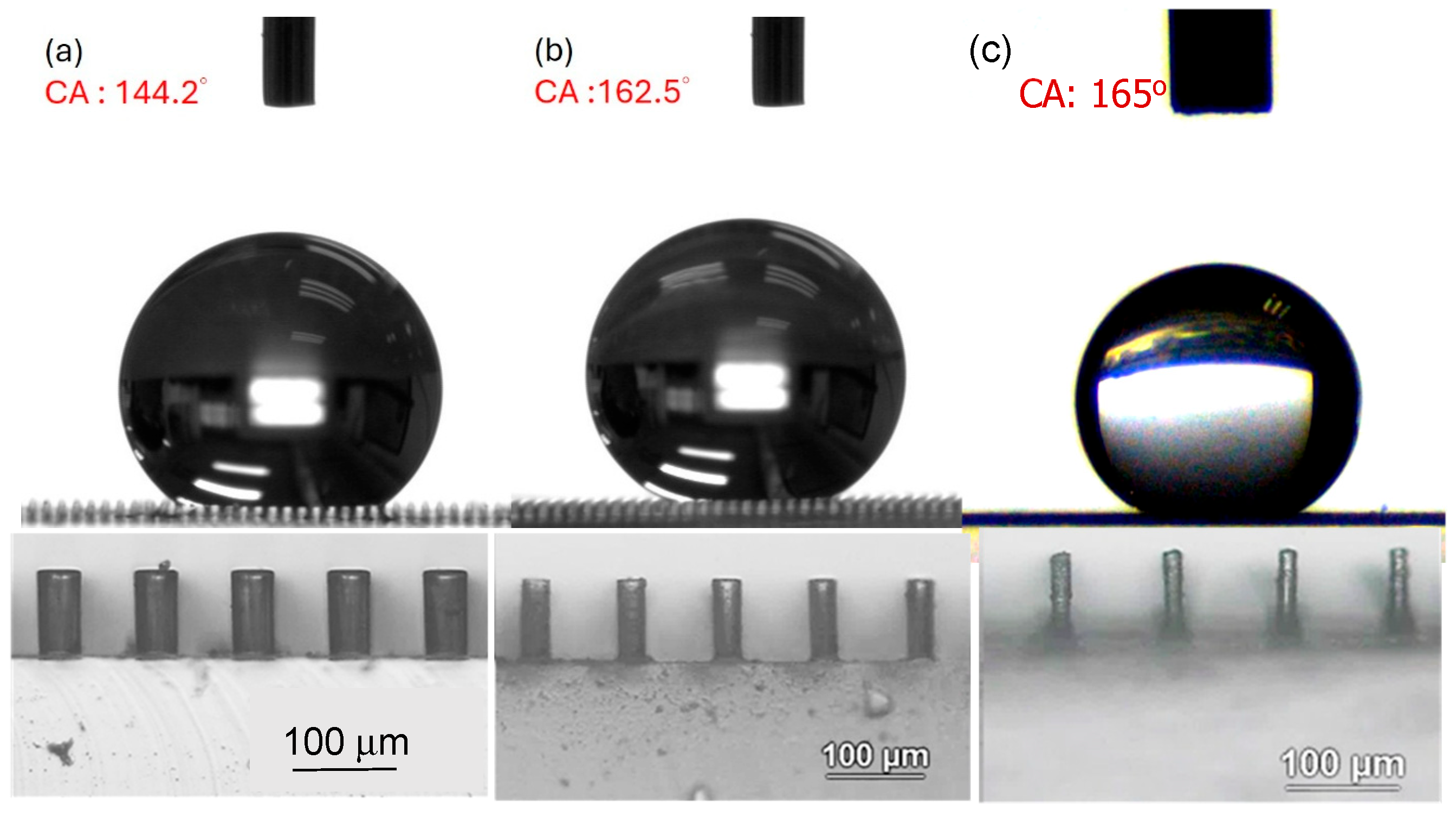

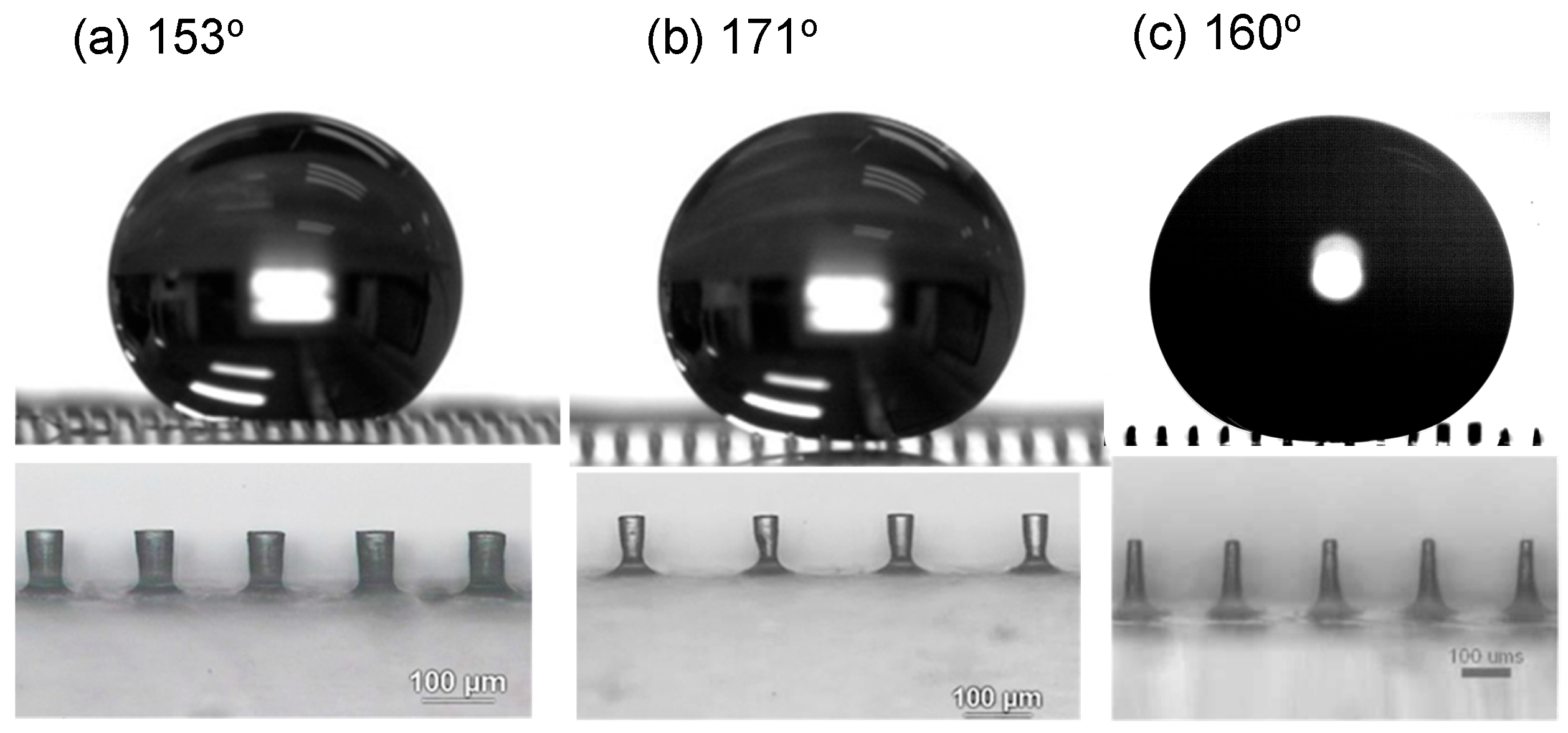

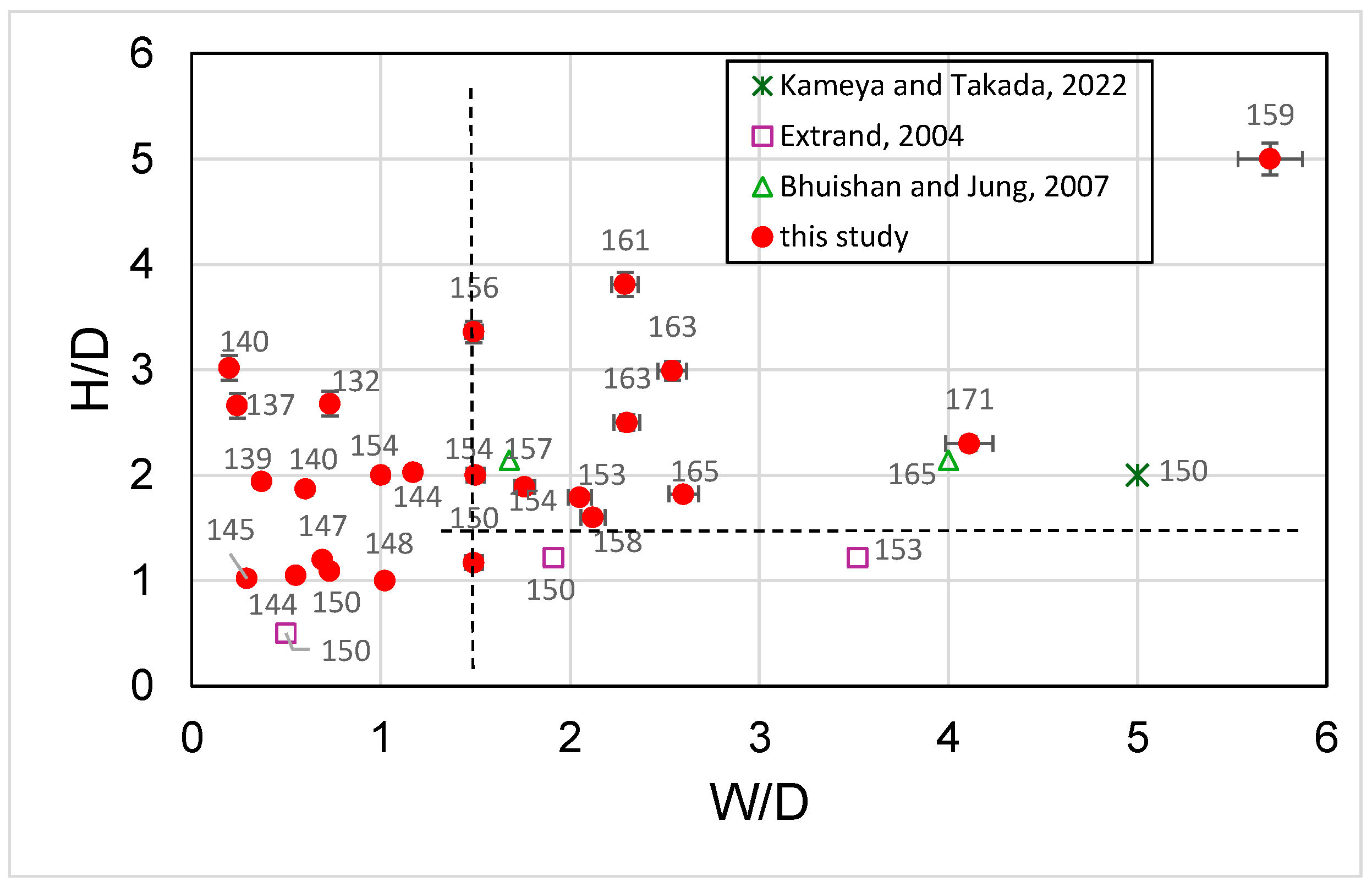

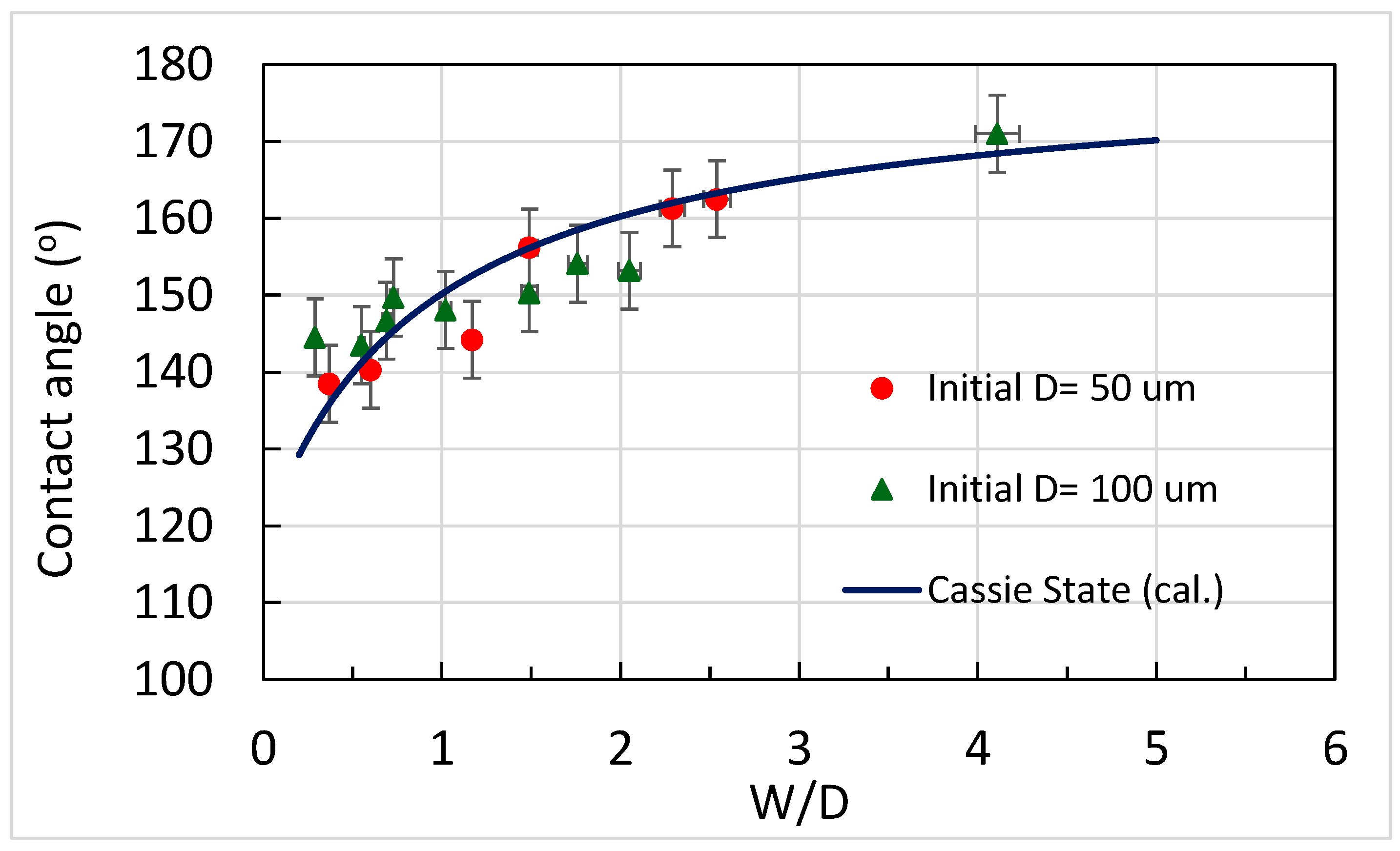

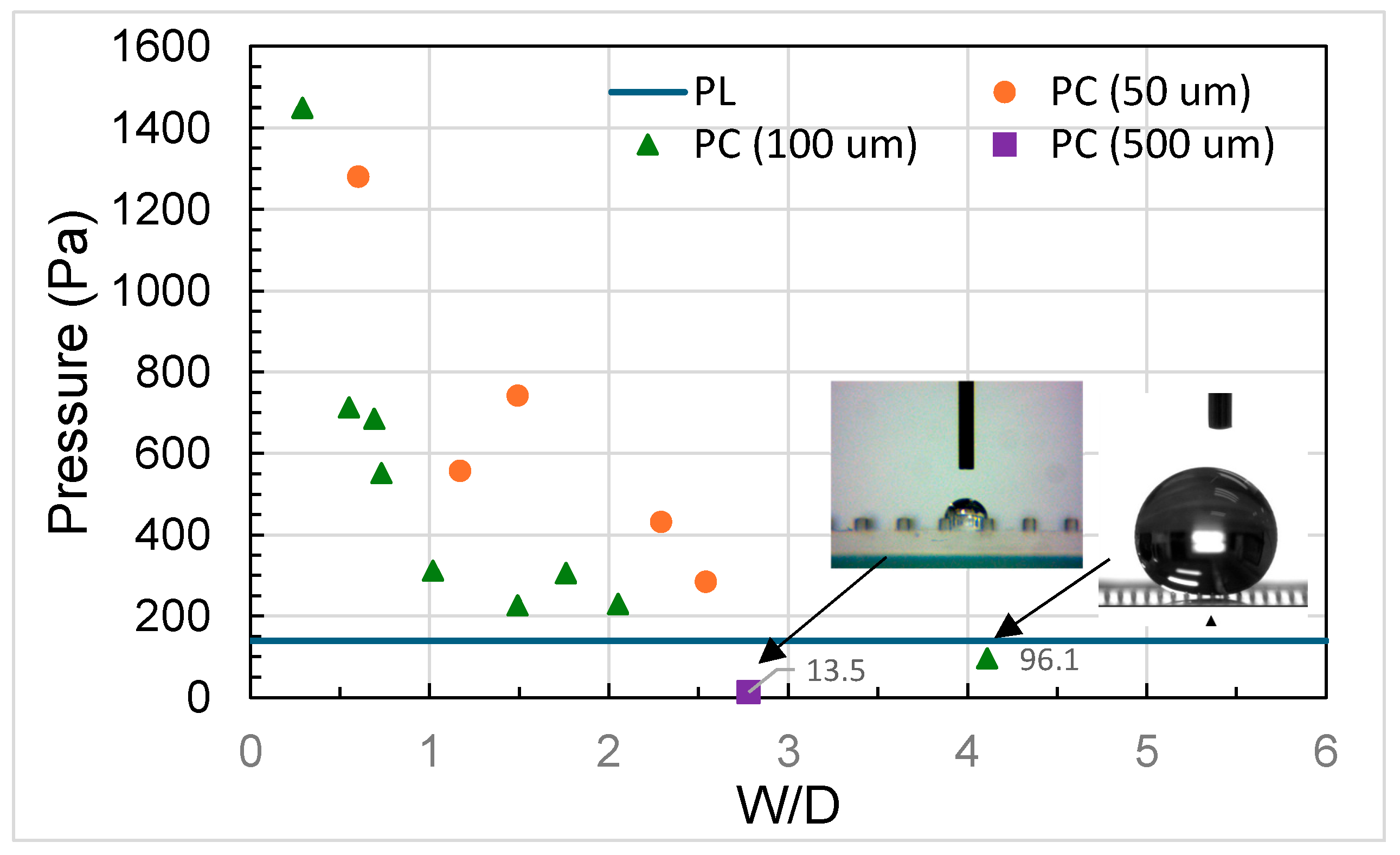

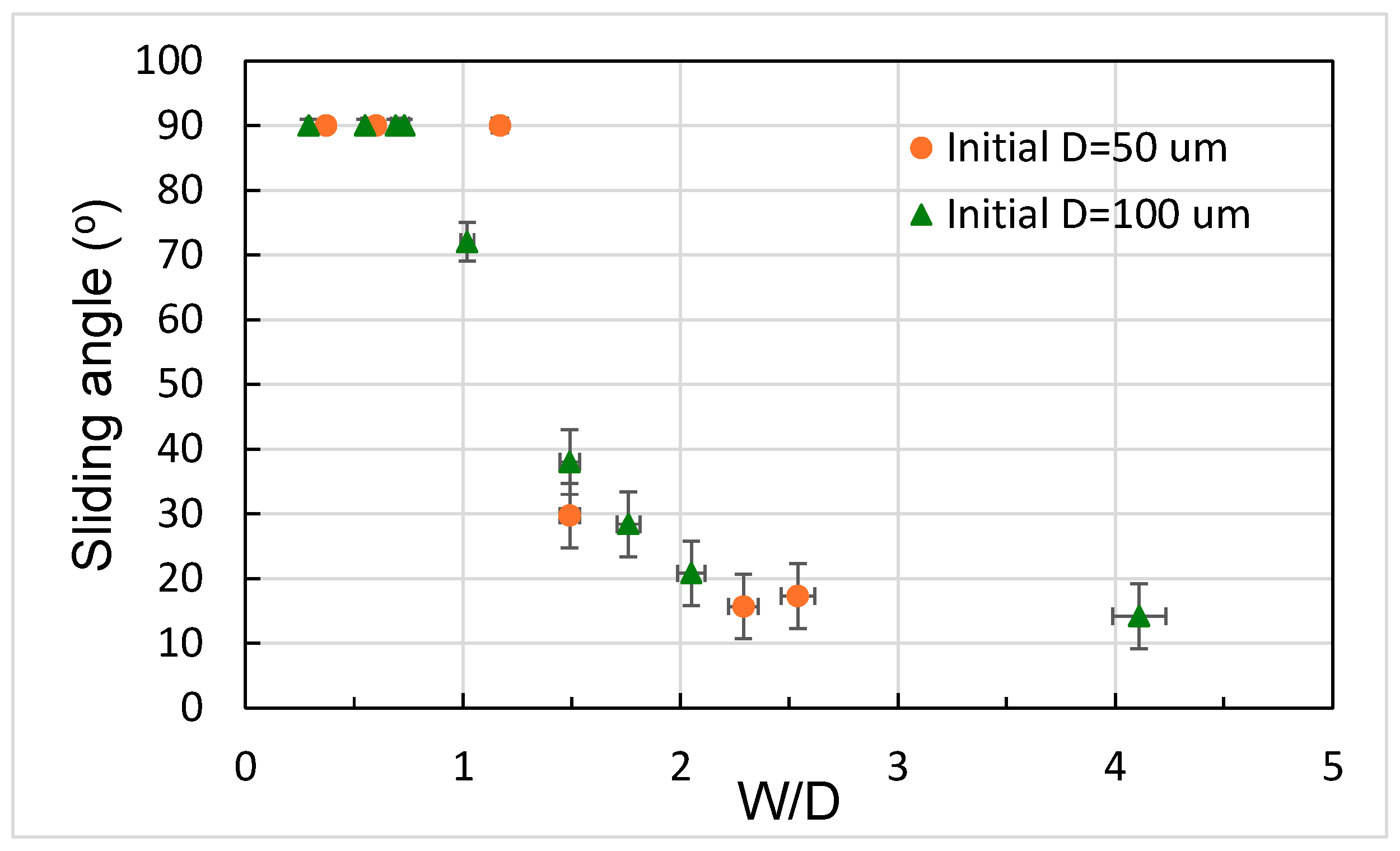

3.2. Analysis of Contact Angles, Sliding Angles, and States of Droplets

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geyer, F.; D’Acunzi, M.; Sharifi-Aghili, A.; Saal, A.; Gao, N.; Kaltbeitzel, A.; Sloot, T.-F.; Berger, R.; Butt, H.-J.; Vollmer, D. When and how self-cleaning of superhydrophobic surfaces works. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaw9727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Z.; Feng, Y.; Seeger, S. Oil/water separation with selective superantiwetting/superwetting surface materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 54, 2328–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Xu, D.; Du, C.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Huang, L.; Deng, L.; Tu, Y.; Mol, J.M.C.; Terryn, H.A. Dual-action smart coatings with a self-healing superhydrophobic surface and anti-corrosion properties. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 2355–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadi, S.; Farzaneh, M.; Kulinich, S. Anti-icing performance of superhydrophobic surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 6264–6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropmann, A.; Tanguy, L.; Koltay, P.; Zengerle, R.; Riegger, L. Completely Superhydrophobic PDMS Surfaces for Microfluidics. Langmuir 2012, 28, 8292–8295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, R.N. Resistance of solid surfaces to wetting by water. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1936, 28, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassie, A.; Baxter, S. Wettability of porous surfaces. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1944, 40, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuteja, A.; Choi, W.; Ma, M.; Mabry, J.M.; Mazzella, S.A.; Rutledge, G.C.; McKinley, G.H.; Cohen, R.E. Designing superoleophobic surfaces. Science 2007, 318, 1618–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmur, A. Wetting on hydrophobic rough surfaces: To be heterogeneous or not to be? Langmuir 2003, 19, 8343–8348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosonovsky, M. Multiscale roughness and stability of superhydrophobic biomimetic interfaces. Langmuir 2007, 23, 3157–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthlott, W.; Neinhuis, C. Purity of the sacred lotus, or escape from contamination in biological surfaces. Planta 1997, 202, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, G.S.; Green, D.W.; Schwarzkopf, L.; Li, X.; Cribb, B.W.; Myhra, S.; Watson, J.A. A gecko skin micro/nano structure—A low adhesion, superhydrophobic, anti-wetting, self-cleaning, biocompatible, antibacterial surface. Acta Biomater. 2015, 21, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, A.; Hashimoto, K.; Watanabe, T. Recent studies on super-hydrophobic films. Monatshefte Für Chem./Chem. Mon. 2001, 132, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herminghaus, S. Roughness-induced non-wetting. Europhys. Lett. 2000, 52, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyssat, M.; Yeomans, J.M.; Quéré, D. Impalement of fakir drops. Europhys. Lett. 2007, 81, 26006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, K.; Paxon, A.; Kwon, H.M.; Deng, T.; Varanasi, K.K. Dynamic wetting on superhydrophobic surfaces: Droplet impact and wetting hysteresis. In Proceedings of the 2010 12th IEEE Intersociety Conference on Thermal and Thermomechanical Phenomena in Electronic Systems, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2–5 June 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kusumaatmaja, H.; Blow, M.L.; Dupuis, A.; Yeomans, J.M. The collapse transition on superhydrophobic surfaces. Europhysics Lett. 2008, 81, 36003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasitha, T.P.; Krishna, N.G.; Anandkumar, B.; Vanithakumari, S.C.; Philip, J. A comprehensive review on anticorrosive/antifouling superhydrophobic coatings: Fabrication, assessment, applications, challenges and future perspectives. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 324, 103090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, S.; Li, J.; Li, R.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Y.; Hu, J.; Lai, Y.; Huang, J.; Wu, X.; Chen, Z. Recent developments in the fabrication, performance, and application of transparent superhydrophobic coatings. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 342, 103537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.R.; Kim, M.S.; Yoon, S.M.; Yoon, S.N.; Han, Y.J.; Yoon, S.H.; Song, J.H.; Jang, N.Y.; Yoon, C.H.; Kim, W.Y.; et al. Multifunctional micro/nanostructured interfaces, fabrication technologies, wetting control, and future prospects. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 12, e00492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Patankar, N.; Choi, J.; Lee, J. Design of surface hierarchy for extreme hydrophobicity. Langmuir 2009, 25, 6129–6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Liao, Y.; Feng, J.; Gao, W.; Xie, S.; Chen, C.; Liu, K.; Gao, R.; Peng, Y.; Leng, Y. Rapid fabrication of superhydrophobic and transparent surfaces by using a laser-induced deep etching process. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 35321–35330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Cheung, E.; Sitti, M. Wet self-cleaning of biologically inspired elastomer mushroom shaped microfibrillar adhesives. Langmuir 2009, 25, 7196–7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, H. Low-Surface-Energy Capped Hydrogel Micropillar Arrays for Transparent Superhydrophobic Antifogging Surfaces. Small 2025, 21, e09390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgaren, R.; Hosseini, M.; Jafari, R.; Momen, G. Nanoparticle-free 3D-printed hydrophobic surfaces for ice mitigation applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, F.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, F.; Sheng, S.; Liu, H.; Xu, Z.; Cao, K.; et al. High Performance Amphibious Light-Driven Soft Actuators Realized by Biomimetic Superhydrophobic Micropillars. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 11618–11625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Du, H.; Zhu, D.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, X.; He, F.; Wang, L.; Lv, C.; Hao, P. Ice adhesion properties on micropillared superhydrophobic surfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 11084–11093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Du, J.; Xu, S.; Lei, J.; Ma, J.; Zhu, L. Ultrasonic Plasticizing and Pressing of High-Aspect Ratio Micropillar Arrays with Superhydrophobic and Superoleophilic Properties. Processes 2024, 12, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Yan, Q.; Qian, Q.; Zhang, S.; Wu, L.; Jiang, S.; Guo, L.; Fan, L.; Wu, H. Directional droplet transfer on micropillar-textured superhydrophobic surfaces fabricated using a ps laser. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 594, 153414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.-L.; Juang, Y.-J. Polydimethyl siloxane wet etching for three dimensional fabrication of microneedle array and high-aspect-ratio micropillars. Biomicrofluidics 2014, 8, 026502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiman, M.; Ryu, K.A.; Esser-Kahn, A.P. Determination of factors influencing the wet etching of polydimethylsiloxane using tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2016, 217, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, C.G.; Esteve, R.M., Jr.; Jones, R.H. Organosilicon chemistry; the mechanisms of hydrolysis of triphenylsilyl fluoride and triphenylmethyl fluoride in 50percent water-50percent acetone solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949, 71, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noll, W. Chemistry and Technology of Silicones; Academic Press Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pei, W.-H.; Hung, C.-C.; Juang, Y.-J. Fabrication of a Superhydrophobic Surface via Wet Etching of a Polydimethylsiloxane Micropillar Array. Polymers 2026, 18, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010132

Pei W-H, Hung C-C, Juang Y-J. Fabrication of a Superhydrophobic Surface via Wet Etching of a Polydimethylsiloxane Micropillar Array. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010132

Chicago/Turabian StylePei, Wu-Hsuan, Chuan-Chieh Hung, and Yi-Je Juang. 2026. "Fabrication of a Superhydrophobic Surface via Wet Etching of a Polydimethylsiloxane Micropillar Array" Polymers 18, no. 1: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010132

APA StylePei, W.-H., Hung, C.-C., & Juang, Y.-J. (2026). Fabrication of a Superhydrophobic Surface via Wet Etching of a Polydimethylsiloxane Micropillar Array. Polymers, 18(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010132