Biowastes as Reinforcements for Sustainable PLA-Biobased Composites Designed for 3D Printing Applications: Structure–Rheology–Process–Properties Relationships

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Fiber Extraction and Preparation

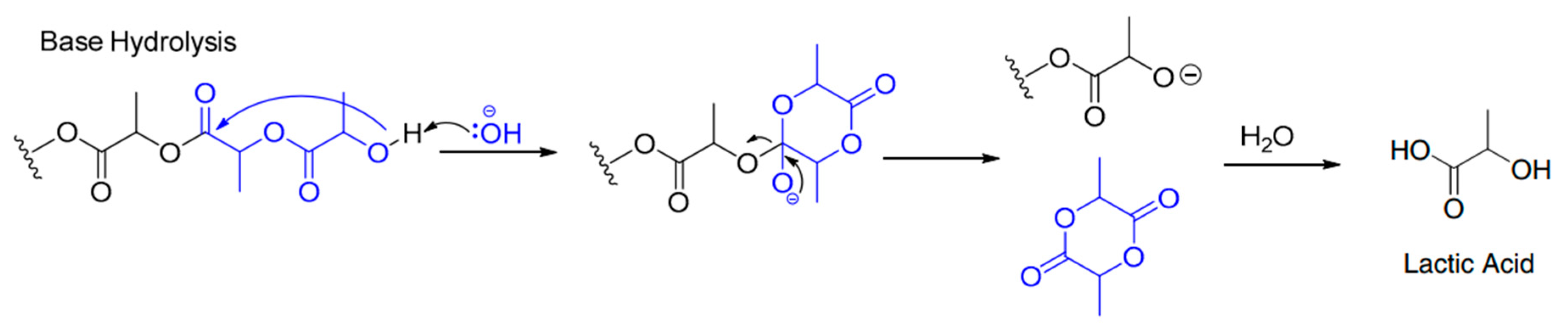

2.3. Chemical Treatment of Bagasse Fibers

2.4. Processing and Preparation of the Bio-Composites

2.4.1. Melt Extrusion

2.4.2. Solvent Casting

2.4.3. Three-Dimensional Printing Process

2.5. Characterization Methods

2.5.1. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.5.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.5.3. Melt Shear Rheological Measurements

2.5.4. Mechanical Properties

2.5.5. Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

2.5.6. Density Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physical Properties of the TSCB Fibers

Granulometric Distribution

3.2. Thermal Stability and Rheology of the Bio-Composites Based on PLA Composites

3.2.1. Thermal Stability of PLA and Bio-Composites Prepared by Melt Processing and Solvent Routes

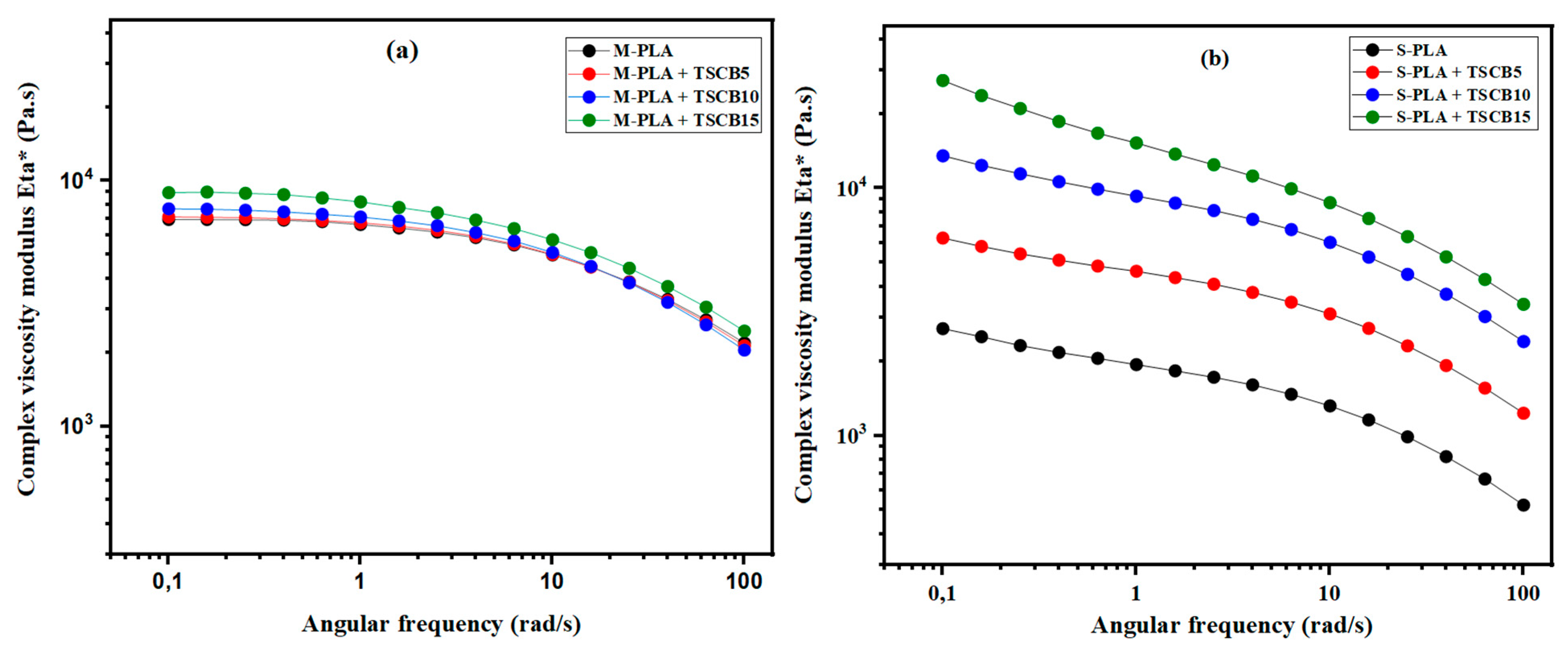

3.2.2. Small-Amplitude Oscillatory Shear (SAOS) Rheology of Molten and Solvent Casting States

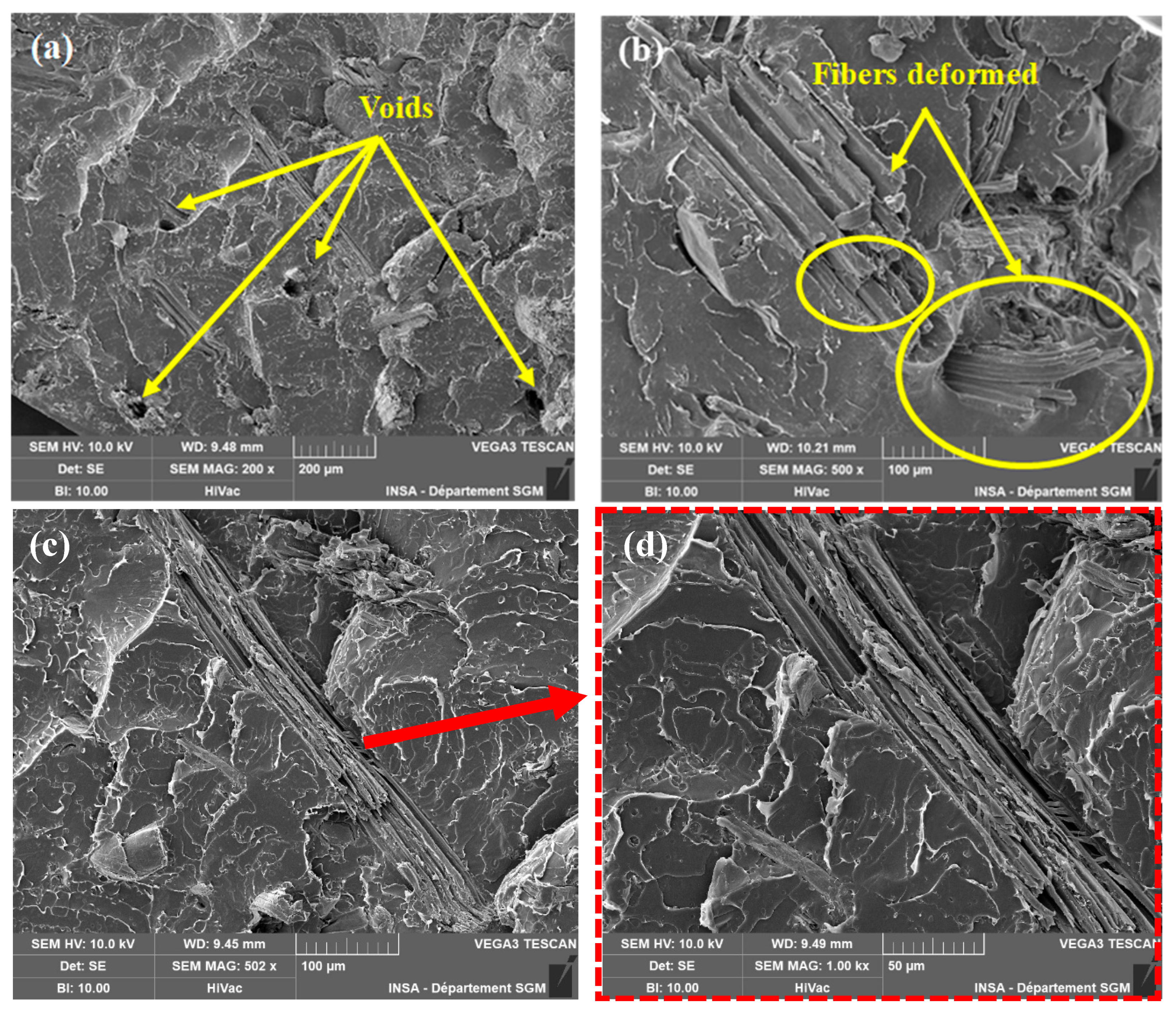

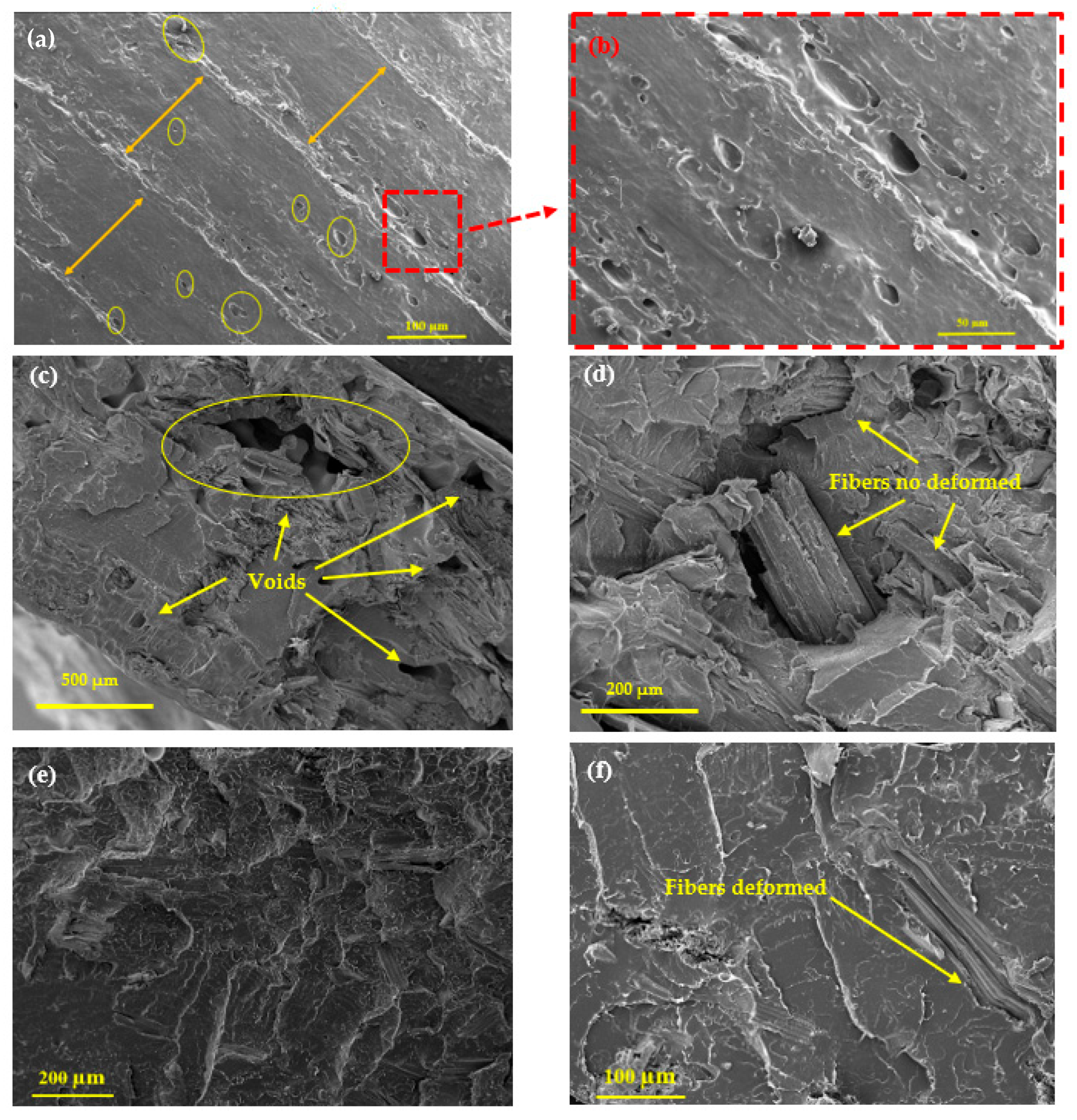

3.3. Morphological Analysis of Bio-Composites Produced by Melt Processing and Solvent Route

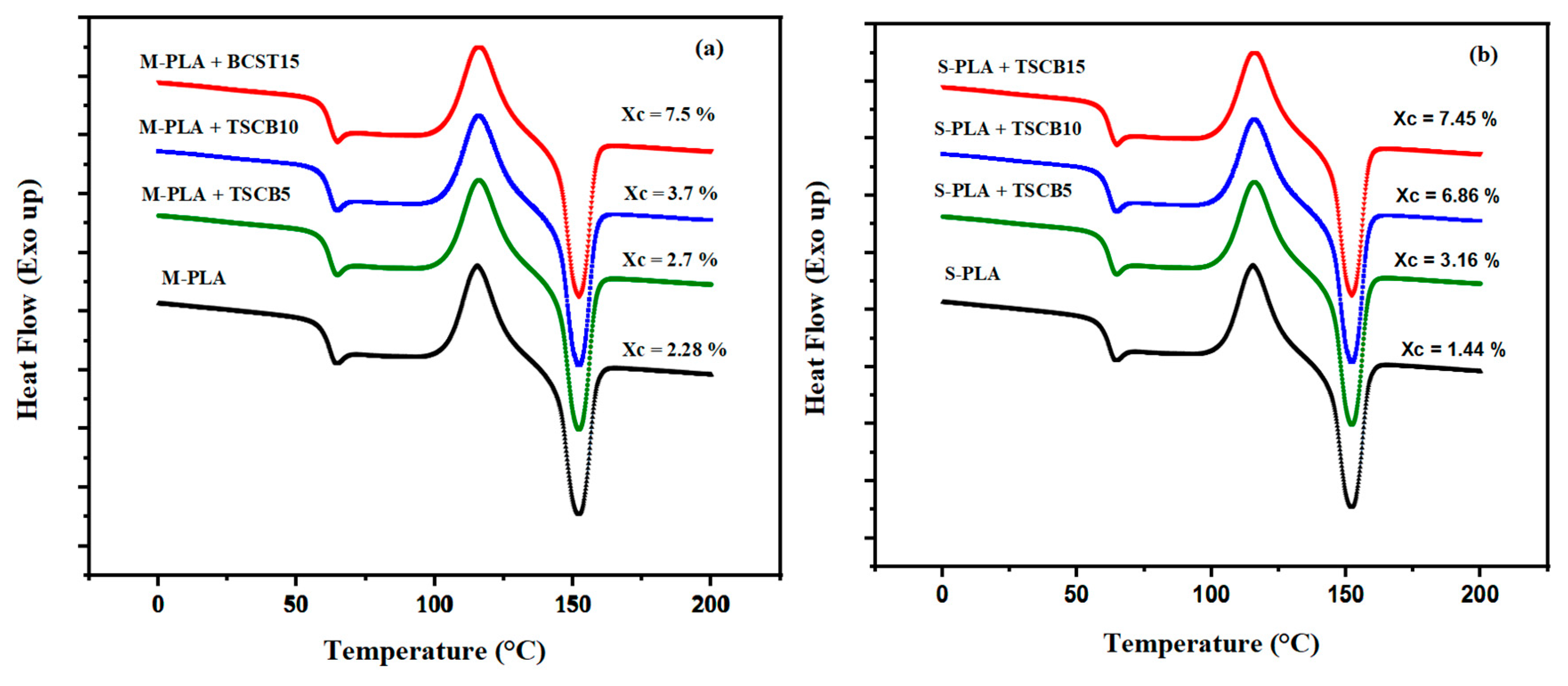

3.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry Properties of the Bio-Composites

Melt Processing and Solvent Casting Properties

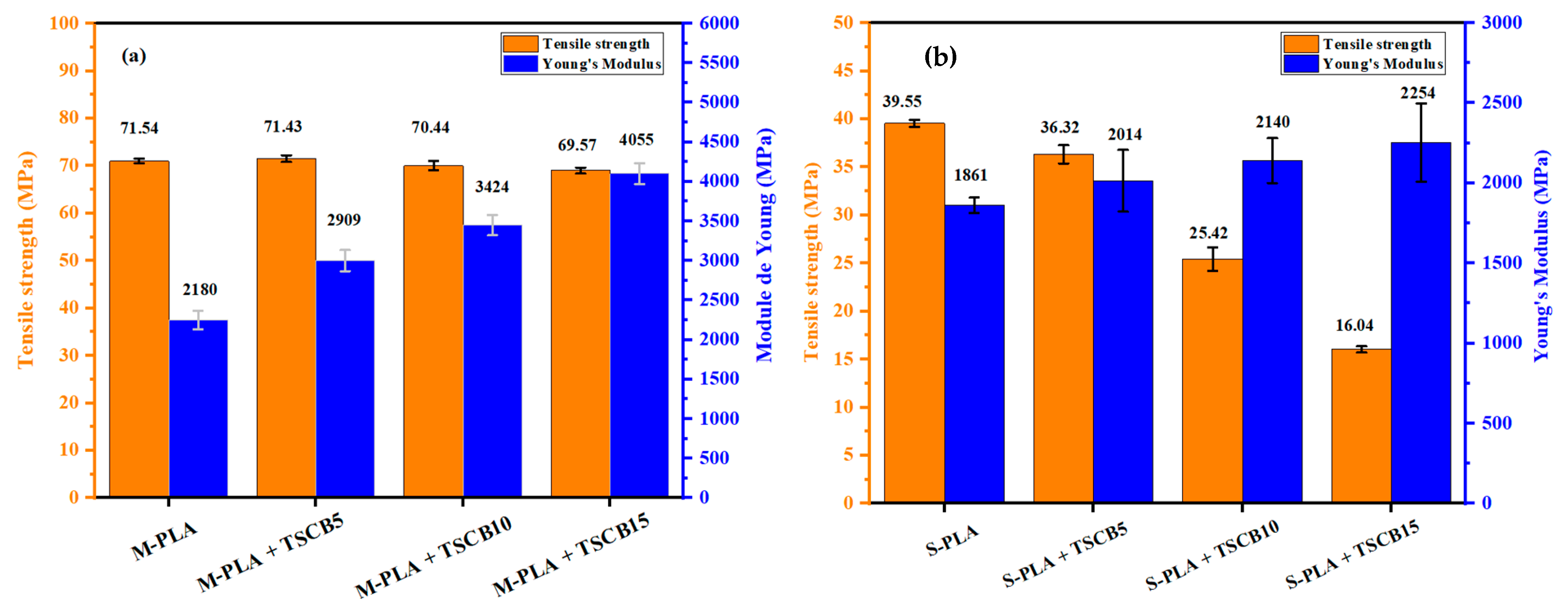

3.5. Mechanical Properties

Tensile Test Properties

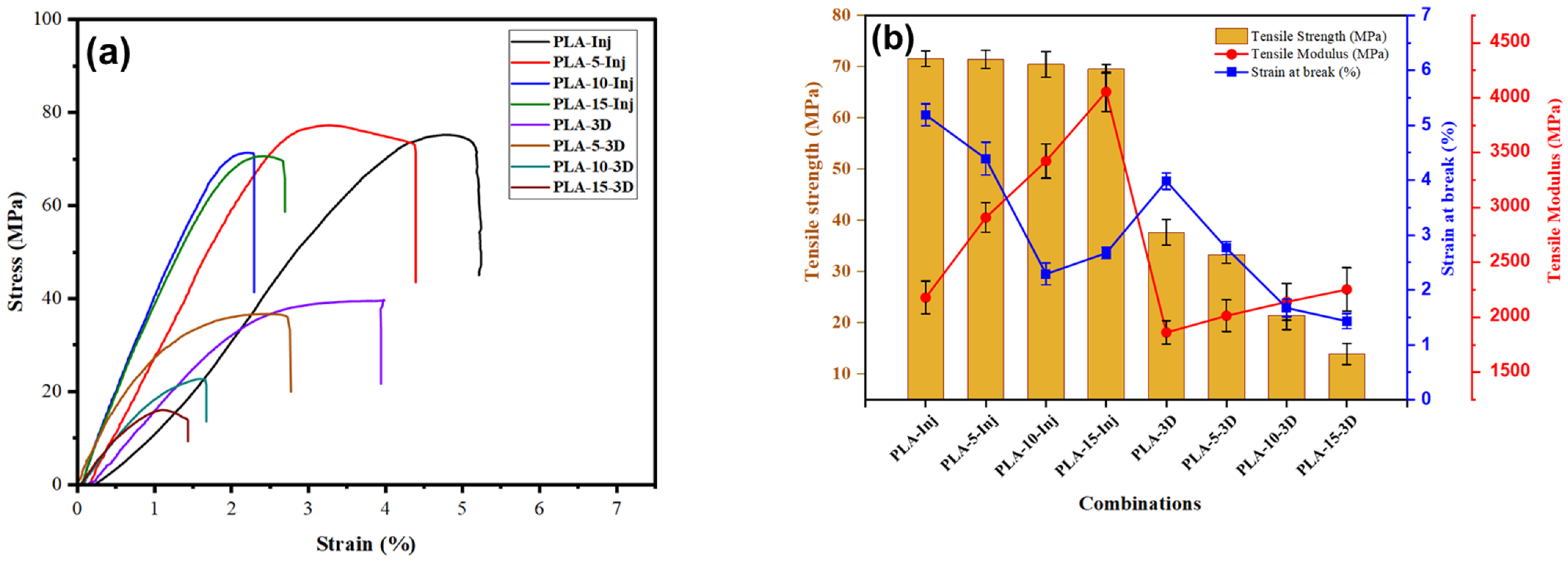

3.6. Comparative Study Between Mechanical Properties of Printed and Injected Specimens

3.6.1. Density and Void Content

3.6.2. Mechanical and Morphological Properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qiao, H.; Sudre, G.; Maazouz, A.; Lamnawar, K. Dual enhancement of dispersion of cellulose nanocrystals, crystallization performance, flexibility and barrier properties through polyethylene glycol coating in melt-processed poly (L-lactide)-based nanocomposites. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 224, 120337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanifard, M.; Khademi, S.M.H.; Asheghi-Oskooee, R.; Farizeh, T.; Hemmati, F. Reactive processing-microstructure-mechanical performance correlations in biodegradable poly (lactic acid)/expanded graphite nanocomposites. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 794–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Maazouz, A.; Lamnawar, K. Study of Morphology, Rheology, and Dynamic Properties toward Unveiling the Partial Miscibility in Poly (lactic acid)—Poly (hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate) Blends. Polymers 2022, 14, 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furet, A.; Singh, S.; Gardrat, C.; Alembik, L.; Jaouannet, R.; Poças, F.; Coma, V. Cellulose trays with PLA-based liners as single-used food packaging: Characterization, performance and migration. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 45, 101329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejene, B.K.; Gudayu, A.D.; Abtew, M.A. Development and optimization of sustainable and functional food packaging using false banana (Enset) fiber and zinc-oxide (ZnO) nanoparticle-reinforced polylactic acid (PLA) biocomposites: A case of Injera preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkumar, G.; Seshadri, S.A.; Devnani, G.L.; Sanjay, M.R.; Siengchin, S.; Maran, J.P.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Karuppiah, P.; Mariadhas, V.A.; Sivarajasekar, N.; et al. Environment friendly, renewable and sustainable poly lactic acid (PLA) based natural fiber reinforced composites – A comprehensive review. J. Cleaner Prod. 2021, 310, 127483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Itry, R.; Lamnawar, K.; Maazouz, A. Reactive extrusion of PLA, PBAT with a multi-functional epoxide: Physico-chemical and rheological properties. Eur. Polym. J. 2014, 58, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaouadi, N.; Jaziri, M.; Maazouz, A.; Lamnawar, K. Biosourced Multiphase Systems Based on Poly(Lactic Acid) and Polyamide 11 from Blends to Multi-Micro/Nanolayer Polymers Fabricated with Forced-Assembly Multilayer Coextrusion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Abdellah, A.; Belcadi, O.; Balla, M.A.; Bounouader, H.; Kaddami, H.; Abidi, N.; Arrakhiz, F.-E. Alkaline Treatment of Sugarcane Bagasse Fibers for Biocomposite Applications. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2024, 58, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Jha, K.; Petru, M.; Kumar, R.; Sharma, S.; Saini, M.S.; Mohammed, K.A.; Kumar, A.; Abbas, M.; Tag-Eldin, E.M. Fabrication and characterization of weld attributes in hot gas welding of alkali treated hybrid flax fiber and pine cone fibers reinforced poly-lactic acid (PLA) based biodegradable polymer composites: Studies on mechanical and morphological properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 272–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcadi, O.; Balla, M.A.; Legrand, C.; Lyagoubi, N.; Laaguel, F.E.; Khalij, L.; Desilles, N.; Gautrelet, C.; El Minor, H.; Arrakhiz, F.E. Impact of process parameters and coupling agent on the thermal stability of argan nutshell composites. J. Compos. Mater. 2025, 59, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, V.; Pariante, R.; Bonanno, A.; Ruiz de Ballesteros, O.; Mollica, F.; Filippone, G. Reinforcing mechanisms of natural fibers in green composites: Role of fibers morphology in a PLA/hemp model system. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 180, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Zainudin, E.S.; Zuhri, M.Y.M. Physical, mechanical and thermal properties of novel bamboo/kenaf fiber-reinforced polylactic acid (PLA) hybrid composites. Compos. Commun. 2024, 51, 102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemakem, M.; Lamnawar, K.; Maazouz, A.; Jaziri, M. Biocomposites based on polylactic acid and olive solid waste fillers: Effect of two compatibilization approaches on the physicochemical, rheological, and mechanical properties. Polym. Compos. 2018, 39, E152–E163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, R.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S. Agro-waste for renewable and sustainable green production: A review. J. Cleaner Prod. 2024, 434, 139989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, R.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S. Sugarcane bagasse for sustainable development of thermoplastic biocomposites. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 120115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, I.; Steuernagel, L.; Ziegmann, G. Optimization of the alkali treatment process of date palm fibres for polymeric composites. Compos. Interfaces 2007, 14, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, I.; Tshai, K.Y.; Hoque, M.E. Manufacturing of Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Manufacturing of Natural Fibre-Reinforced Polymer Composites by Solvent Casting Method; pp. 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukaffa, H.; Asrofi, M.; Sujito; Asnawi; Hermawan, Y.; Sumarji; Qoryah, R.D.H.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Atiqah, A. Effect of alkali treatment of piper betle fiber on tensile properties as biocomposite based polylactic acid: Solvent cast-film method. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 48, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, O.; Ave, L. Poly(lactic acid): Plasticization and properties of biodegradable multiphase systems. Polymer 2001, 42, 6209–6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufresne, A. Comparing the mechanical properties of high performances polymer nanocomposites from biological sources. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2006, 6, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samir, M.A.S.A.; Alloin, F.; Dufresne, A. Review of Recent Research into Cellulosic Whiskers, Their Properties and Their Application in Nanocomposite Field. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 612–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bras, J.; Viet, D.; Bruzzese, C.; Dufresne, A. Correlation between stiffness of sheets prepared from cellulose whiskers and nanoparticles dimensions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 84, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatansever, E.; Arslan, D.; Nofar, M. Polylactide cellulose-based nanocomposites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 137, 912–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, T.; Budtova, T. Morphology and molten-state rheology of polylactide and polyhydroxyalkanoate blends. Eur. Polym. J. 2012, 48, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, P.; Jones, M.D. The Chemical Recycling of PLA: A Review. Sustain. Chem. 2020, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krikorian, V.; Pochan, D.J. Poly (L-Lactic Acid)/Layered Silicate Nanocomposite: Fabrication, Characterization, and Properties. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 4317–4324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signori, F.; Coltelli, M.-B.; Bronco, S. Thermal degradation of poly (lactic acid) (PLA) and poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) and their blends upon melt processing. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2009, 94, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzner, A.B. Rheology of Suspensions in Polymeric Liquids. J. Rheol. 1985, 29, 739–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Itry, R.; Lamnawar, K.; Maazouz, A. Improvement of thermal stability, rheological and mechanical properties of PLA, PBAT and their blends by reactive extrusion with functionalized epoxy. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 1898–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, A.; Pop, M.A.; Coșereanu, C. 3D Printing Application in Wood Furniture. Materials 2022, 15, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Liu, C.; Coppola, B.; Barra, G.; Maio, L.D.; Incarnato, L.; Lafdi, K. Effect of Porosity and Crystallinity on 3D Printed PLA Properties. Polymer 2019, 11, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa-Velarde, V.; Diaz-Vidal, T.; Cisneros-López, E.O.; Robledo-Ortiz, J.R.; López-Naranjo, E.J.; Ortega-Gudiño, P.; Rosales-Rivera, L.C. Mechanical and Physicochemical Properties of 3D-Printed Agave Fibers/Poly(lactic) Acid Biocomposites. Materials 2021, 14, 3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaliotis, E.M.; Ake-Concha, B.D.; May-Pat, A.; Morales-Arias, J.P.; Bernal, C.; Valadez-Gonzalez, A.; Herrera-Franco, P.J.; Proust, G.; Koh-Dzul, J.F.; Carrillo, J.G.; et al. Tensile Behavior of 3D Printed Polylactic Acid (PLA) Based Composites Reinforced with Natural Fiber. Polymers 2022, 14, 3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Kong, F.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Yin, Q.; Xing, D.; Li, P. A review on voids of 3D printed parts by fused filament fabrication. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 4860–4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochnia, J.; Blasiak, M.; Kozior, T. A Comparative Study of the Mechanical Properties of FDM 3D Prints Made of PLA and Carbon Fiber-Reinforced PLA for Thin-Walled Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhang, M.; Guo, Z.; Sang, L.; Hou, W. Investigation of processing parameters on tensile performance for FDM-printed carbon fiber reinforced polyamide 6 composites. Compos. Commun. 2020, 22, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qu, P.; Kong, H.; Lei, Y.; Guo, A.; Wang, S.; Wan, Y.; Takahashi, J. Enhanced mechanical properties of sandwich panels via integrated 3D printing of continuous fiber face sheet and TPMS core. Thin. Walled. Struct. 2024, 204, 112312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qu, P.; Kong, H.; Zhu, Y.; Hua, C.; Guo, A.; Wang, S. Multi-scale numerical analysis of damage modes in 3D stitched composites. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 266, 108983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polymer 10. | Supplier | Tg (°C) | Tm (°C) | MFI (g/10 min) (190 °C/2.16 Kg) | Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | Natureworks, Plymouth, MN, USA | 60 | 155 | 6 | 1.24 |

| Sample Name | PLA Content (wt%) | TSCB Content (wt%) |

|---|---|---|

| M-PLA | 100 | 0 |

| M-PLA-TSCB5 | 95 | 5 |

| M-PLA-TSCB10 | 90 | 10 |

| M-PLA-TSCB15 | 85 | 15 |

| Sample Name | PLA Content (wt%) | TSCB Content (wt%) |

|---|---|---|

| S-PLA | 100 | 0 |

| S-PLA-TSCB5 | 95 | 5 |

| S-PLA-TSCB10 | 90 | 10 |

| S-PLA-TSCB15 | 85 | 15 |

| Samples | (g/mol) | (g/mol) | (g/mol) | K (Degradation Parameter) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA pellet | 125.000 | 91.540 | 168.100 | |

| PLA E@ 170 °C | 122.400 | 90.550 | 160.700 | 1.01 |

| PLA R@ 190 °C | 117.200 | 87.760 | 152.900 | 1.04 |

| PLA5 E@ 170 °C | 111.900 | 88.320 | 146.800 | 1.03 |

| PLA5 R@ 190 °C | 106.600 | 82.650 | 141.000 | 1.10 |

| PLA10 E@ 170 °C | 108.200 | 82.400 | 144.300 | 1.11 |

| PLA10 R@ 190 °C | 97.930 | 79.100 | 138.300 | 1.16 |

| PLA15 E@ 170 °C | 107.200 | 80.590 | 142.800 | 1.13 |

| PLA15 R@ 190 °C | 98.670 | 77.630 | 125.600 | 1.17 |

| Sample | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | ) | ) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-PLA | 60 | 119 | 150 | 20.57 | 18.43 | 2.28 |

| M-PLA + TSCB5 | 60 | 120 | 150.9 | 21.5 | 19.09 | 2.7 |

| M-PLA + TSCB10 | 60.3 | 121 | 150.9 | 20.61 | 17.47 | 3.7 |

| M-PLA + TSCB15 | 60.1 | 121 | 151.1 | 22.77 | 18.44 | 7.5 |

| Sample | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | ) | ) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-PLA | 57 | 119 | 151.9 | 9.73 | 8.38 | 1.44 |

| S-PLA + TSCB5 | 58 | 121 | 151.8 | 15.22 | 12.41 | 3.16 |

| S-PLA + TSCB10 | 59.8 | 121 | 150.9 | 17.82 | 12.04 | 6.86 |

| S-PLA + TSCB15 | 60.1 | 122 | 150.9 | 18.04 | 12.11 | 7.45 |

| Method | Sample | Strain at Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Melt processing | M-PLA | 5.19 (±1.2) |

| M-PLA + TSCB5 | 4.39 (±0.7) | |

| M-PLA + TSCB10 | 2.29 (±0.5) | |

| M-PLA + TSCB15 | 2.67 (±0.3) | |

| Solvent casting | S-PLA | 3.34 (±0.7) |

| S-PLA + TSCB5 | 3.45 (±0.4) | |

| S-PLA + TSCB10 | 2.39 (±0.2) | |

| S-PLA + TSCB15 | 2.85 (±0.4) |

| Formulations | Theoretical Density (g/cm3) | Experimental Density (g/cm3) | Void Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M-PLA inj | 1.24 | 1.22 | 1.6 |

| M-PLA-3D | 1.24 | 1.16 | 6.5 |

| M-PLA+5 TSCB inj | 1.25 | 1.21 | 3.3 |

| M-PLA+5 TSCB-3D | 1.25 | 1.15 | 8.1 |

| M-PLA+10 TSCB | 1.26 | 1.21 | 4.1 |

| M-PLA+10 TSCB-3D | 1.26 | 1.14 | 9.7 |

| M-PLA+15 TSCB | 1.27 | 1.18 | 7.3 |

| M-PLA+15 TSCB-3D | 1.27 | 1.12 | 12.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ait Balla, M.; Maazouz, A.; Lamnawar, K.; Arrakhiz, F.E. Biowastes as Reinforcements for Sustainable PLA-Biobased Composites Designed for 3D Printing Applications: Structure–Rheology–Process–Properties Relationships. Polymers 2026, 18, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010128

Ait Balla M, Maazouz A, Lamnawar K, Arrakhiz FE. Biowastes as Reinforcements for Sustainable PLA-Biobased Composites Designed for 3D Printing Applications: Structure–Rheology–Process–Properties Relationships. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010128

Chicago/Turabian StyleAit Balla, Mohamed, Abderrahim Maazouz, Khalid Lamnawar, and Fatima Ezzahra Arrakhiz. 2026. "Biowastes as Reinforcements for Sustainable PLA-Biobased Composites Designed for 3D Printing Applications: Structure–Rheology–Process–Properties Relationships" Polymers 18, no. 1: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010128

APA StyleAit Balla, M., Maazouz, A., Lamnawar, K., & Arrakhiz, F. E. (2026). Biowastes as Reinforcements for Sustainable PLA-Biobased Composites Designed for 3D Printing Applications: Structure–Rheology–Process–Properties Relationships. Polymers, 18(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010128