Direct Solid-State Polymerization of Highly Aliphatic PA 1212 Salt: Critical Parameters and Reaction Mechanism Investigation Under Different Reactor Designs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Starting Materials

2.2. Polyamide Salt Preparation Method

2.3. Direct Solid-State Polymerization (DSSP)

2.4. Characterization Methods

2.4.1. Particle Size Distribution

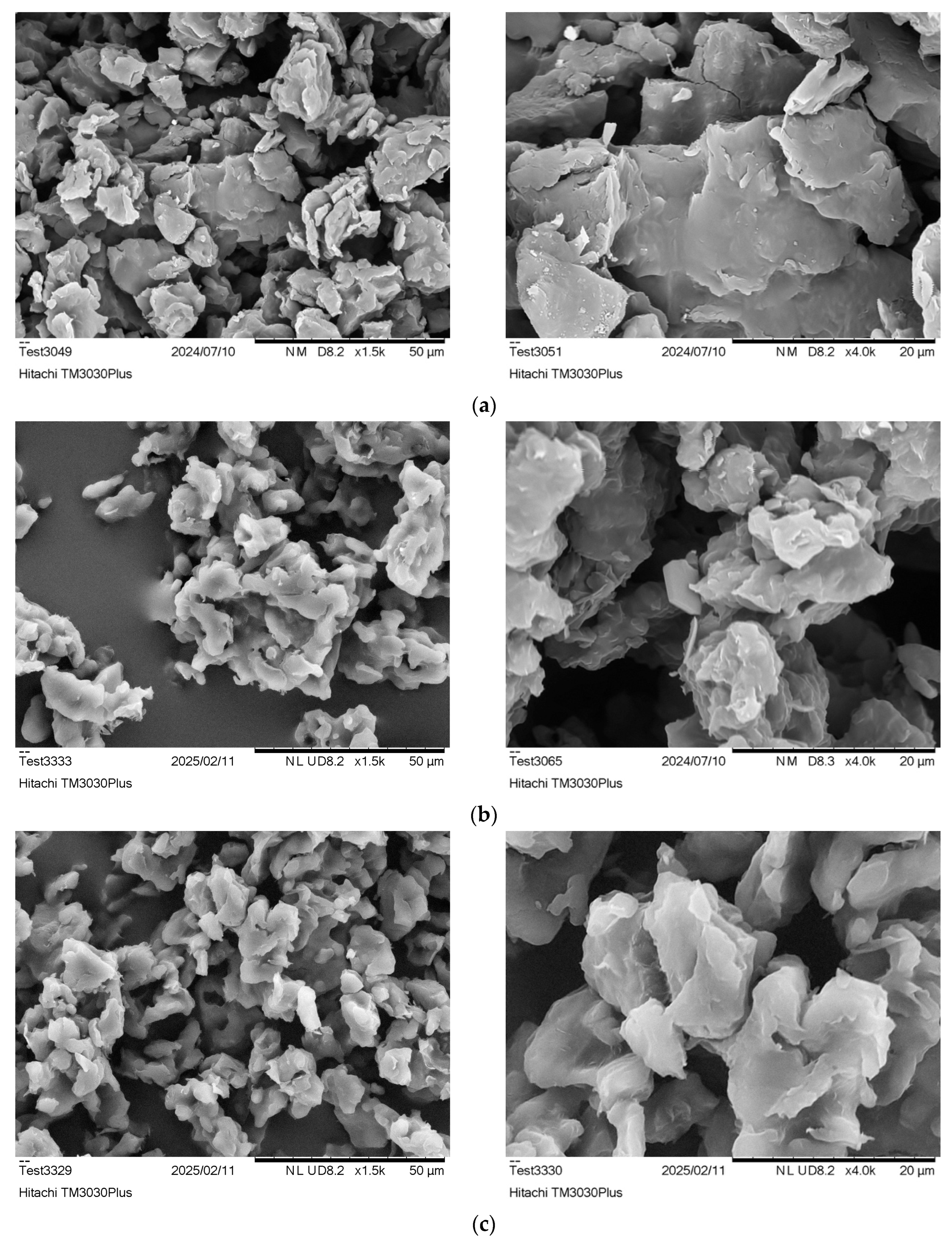

2.4.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

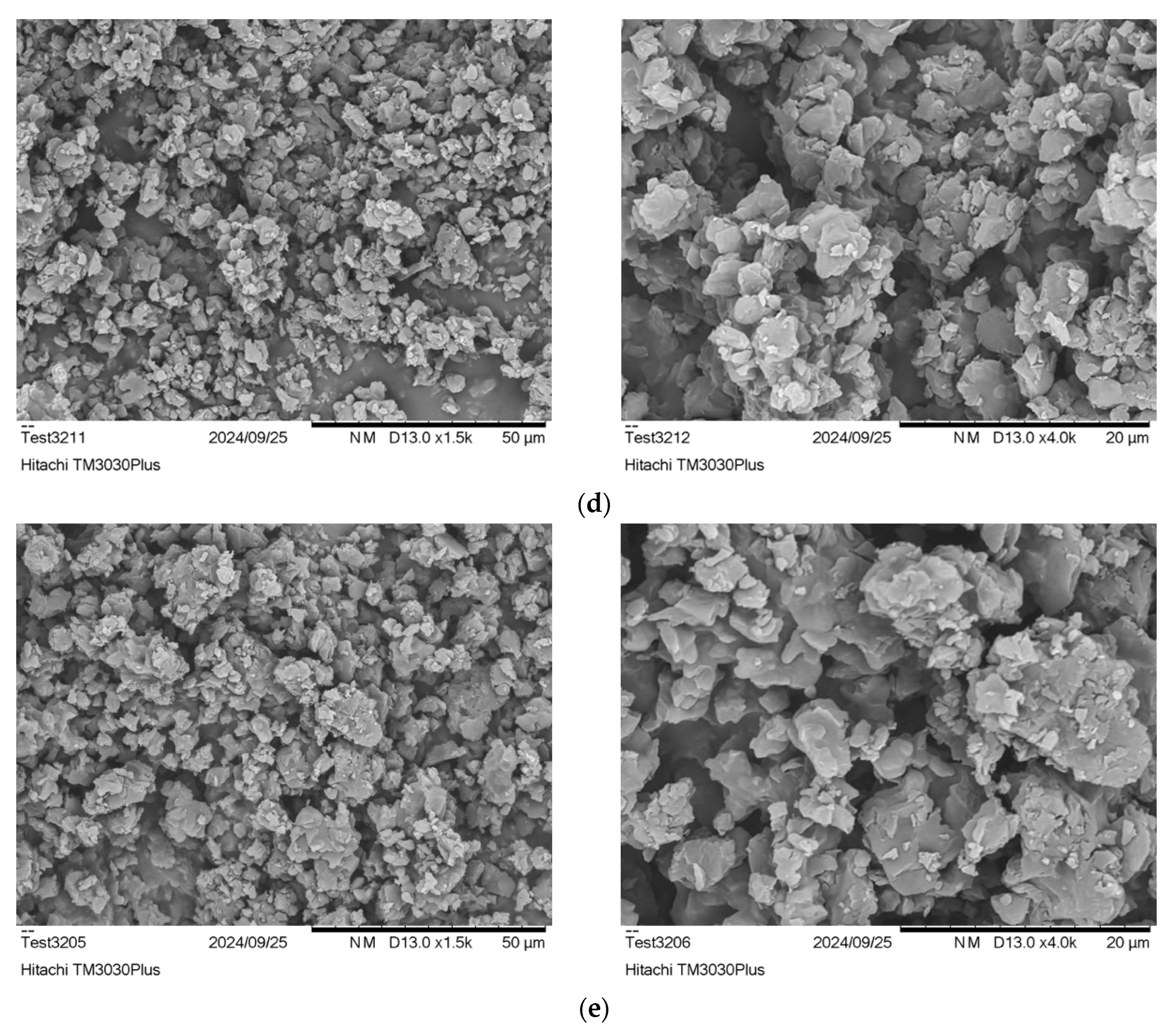

2.4.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy-Attenuated Total Refraction (FTIR-ATR)

2.4.4. End-Group Concentrations

2.4.5. Dilute Solution Viscometry

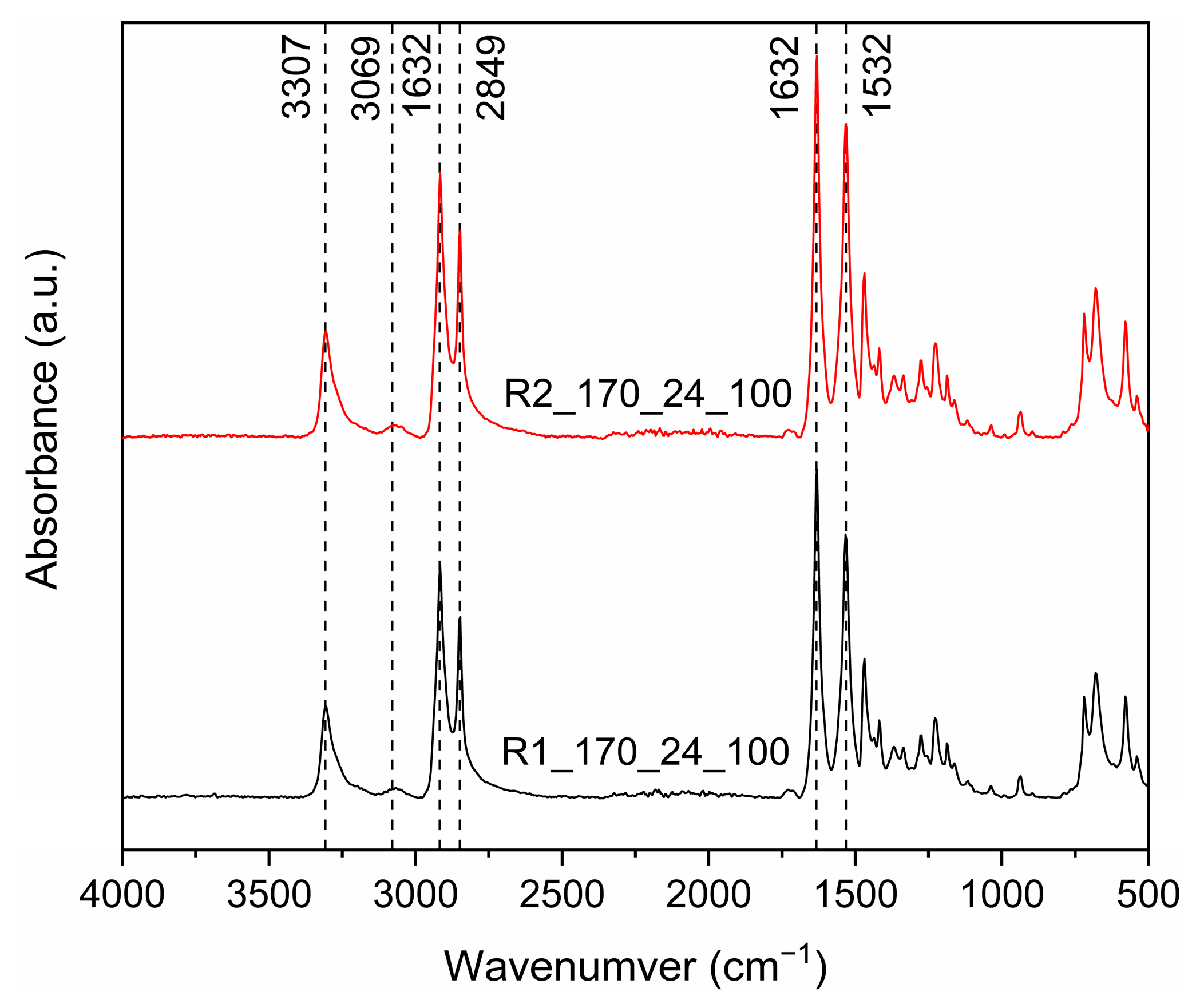

2.4.6. Thermal Properties

3. Results

3.1. Polyamide Salt Preparation

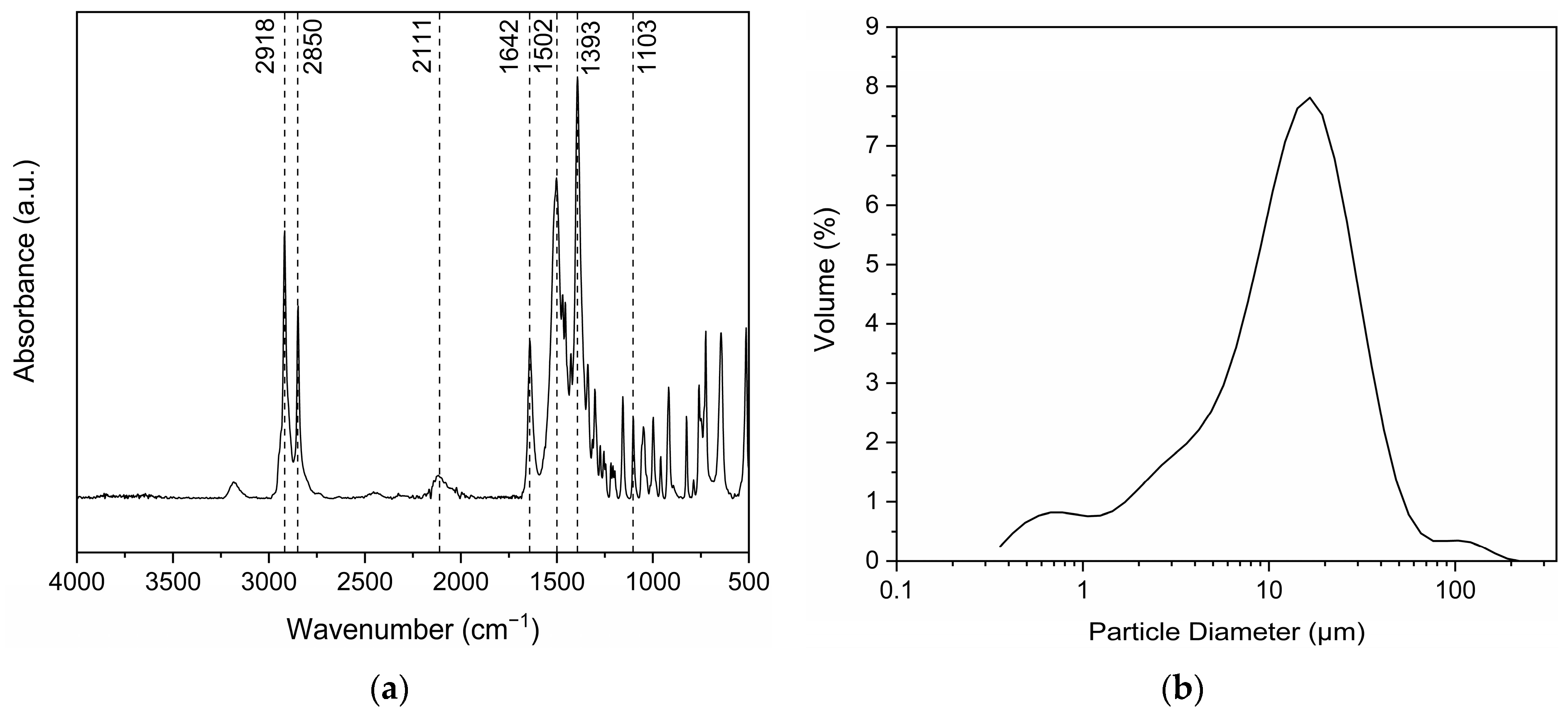

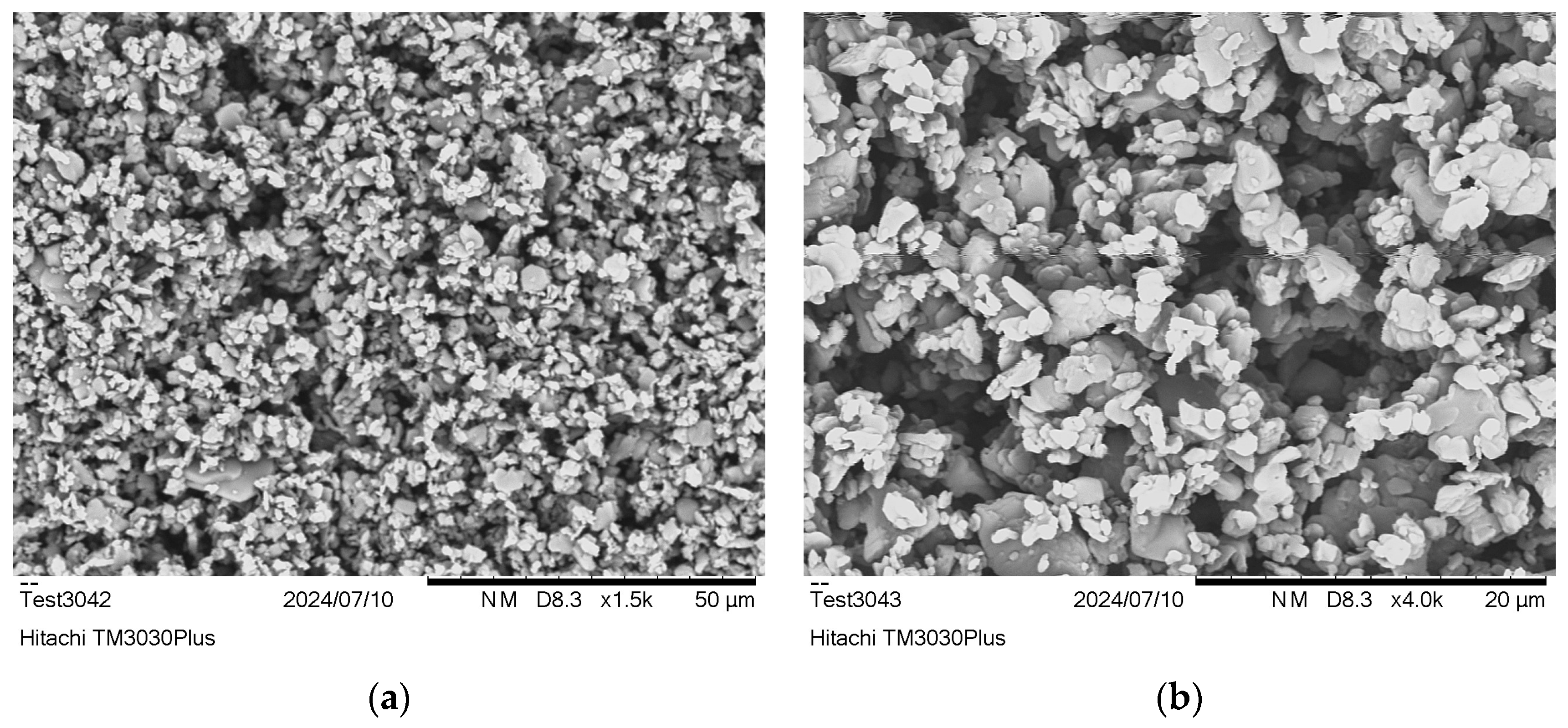

3.1.1. Salt Structure and Particle Size

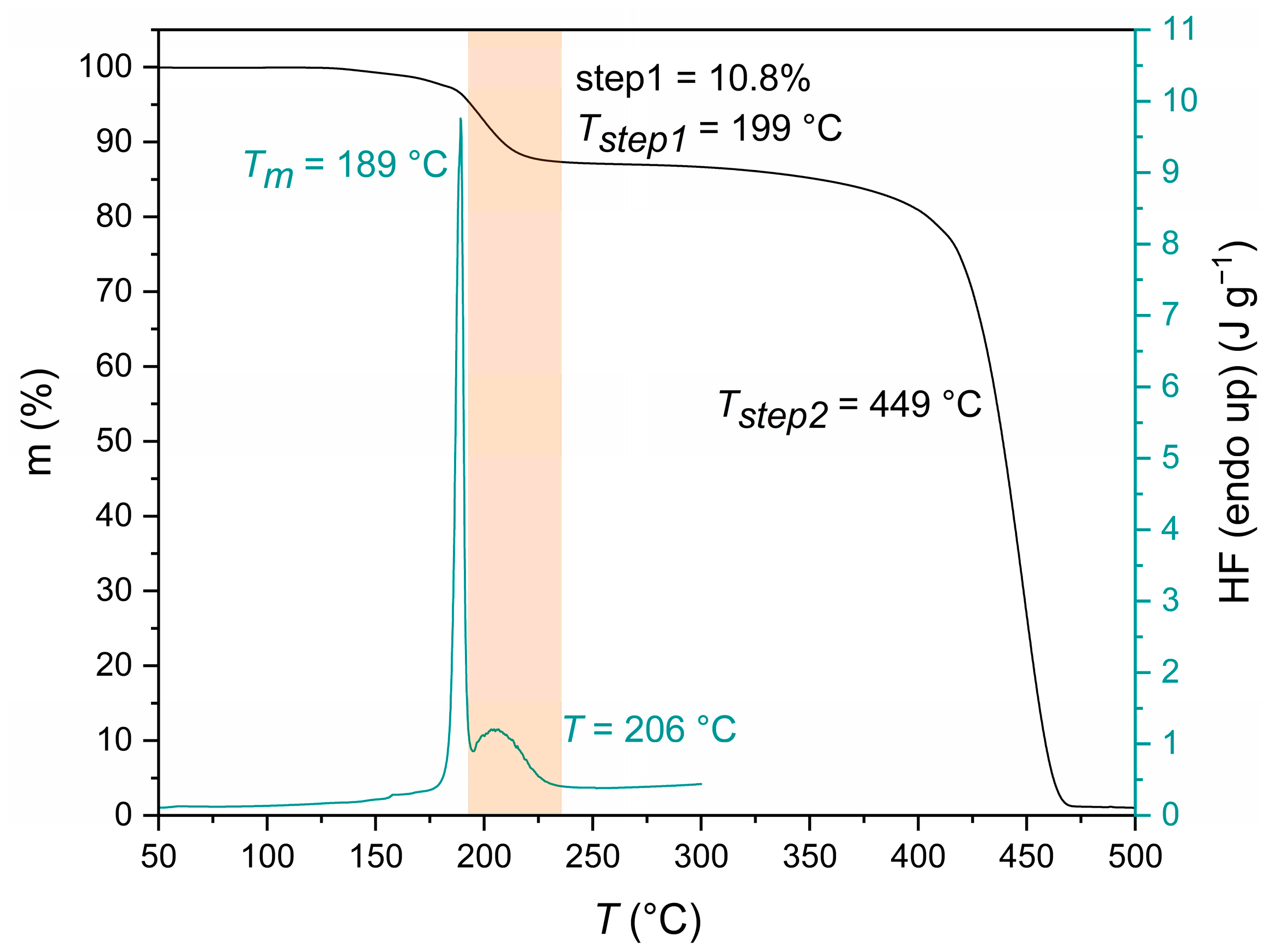

3.1.2. End-Group Analysis and Thermal Properties

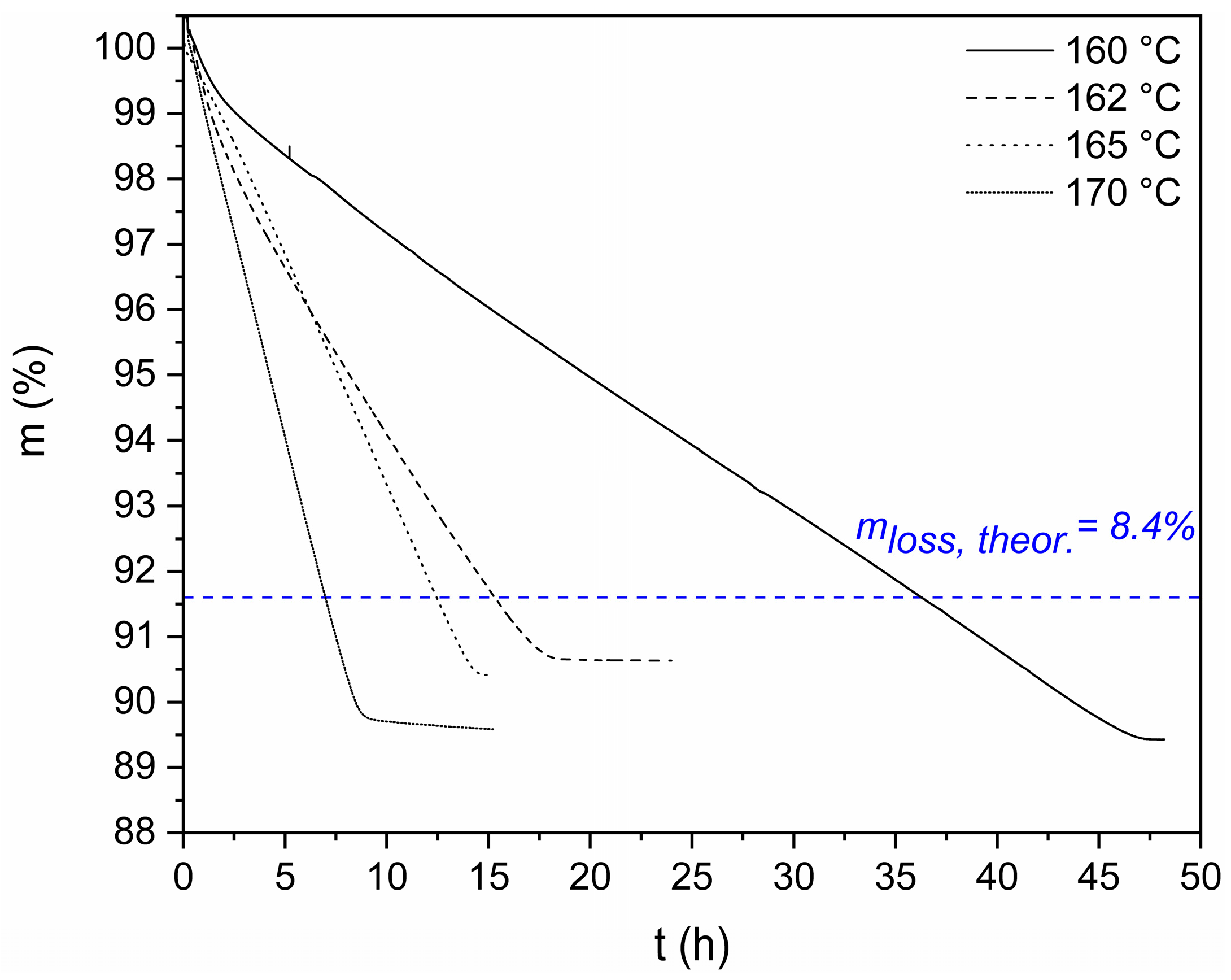

3.2. DSSP in Microscale

3.3. DSSP on a Laboratory Scale

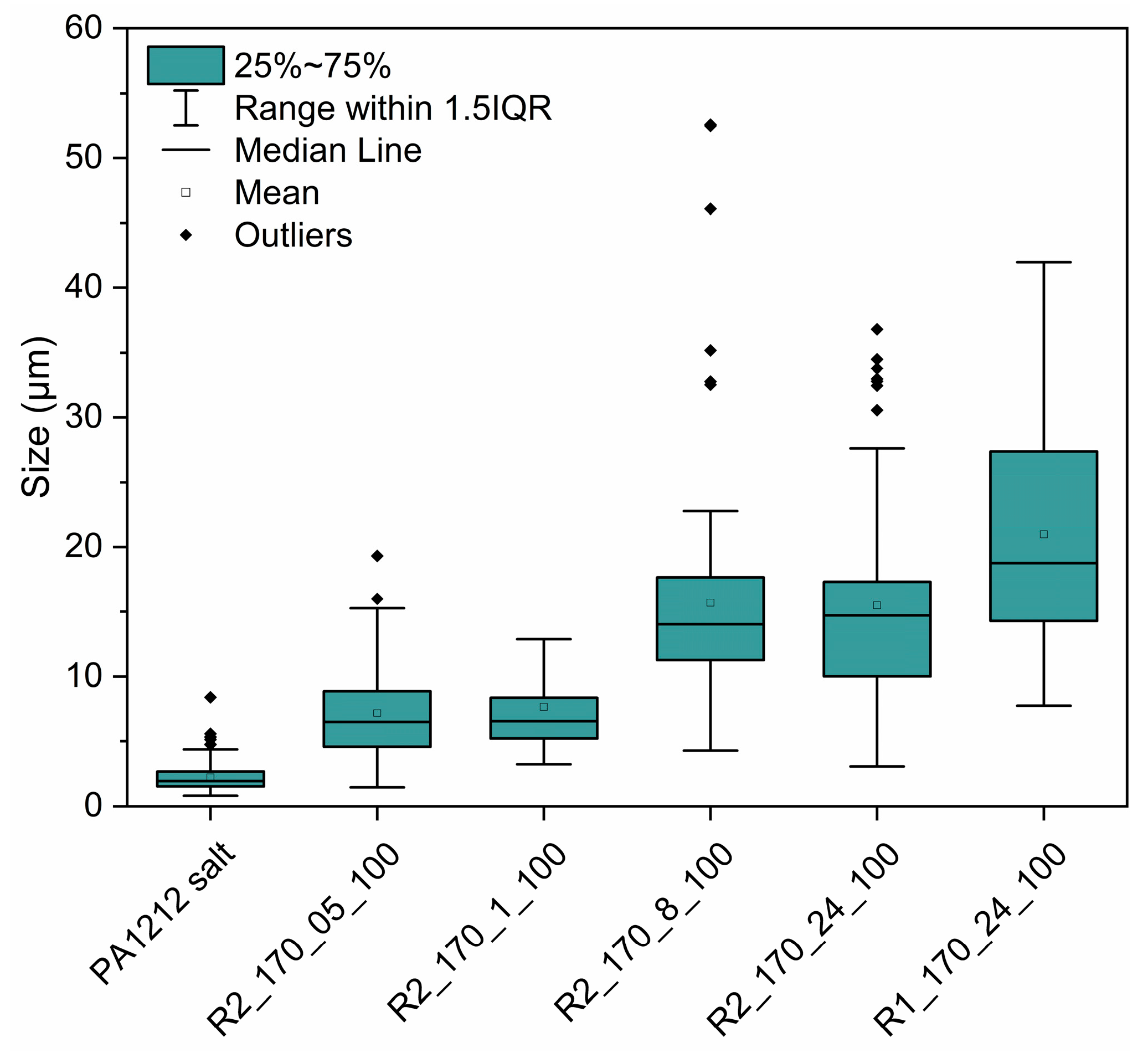

3.3.1. Effect of Reactor Design: Comparison of R1 and R2

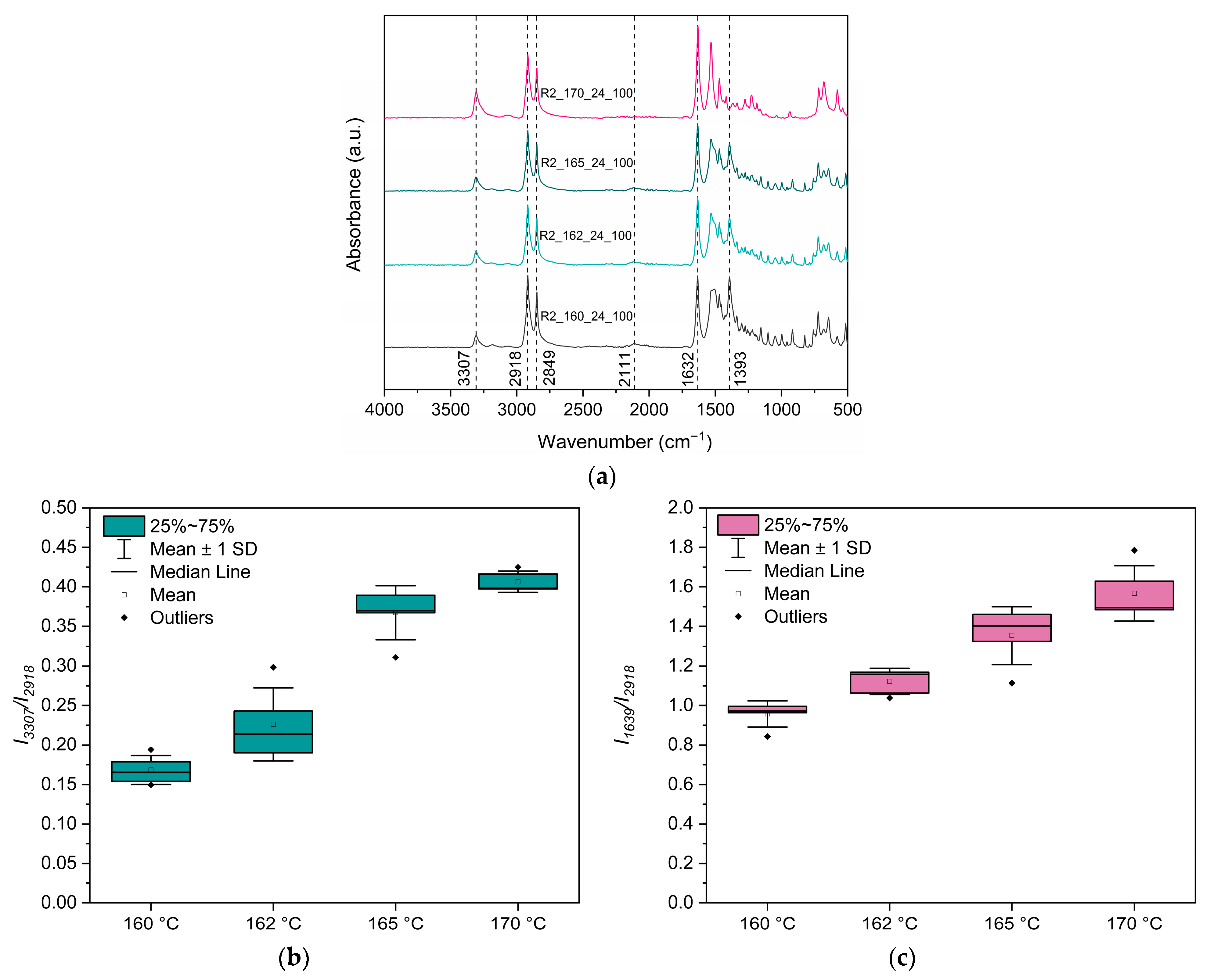

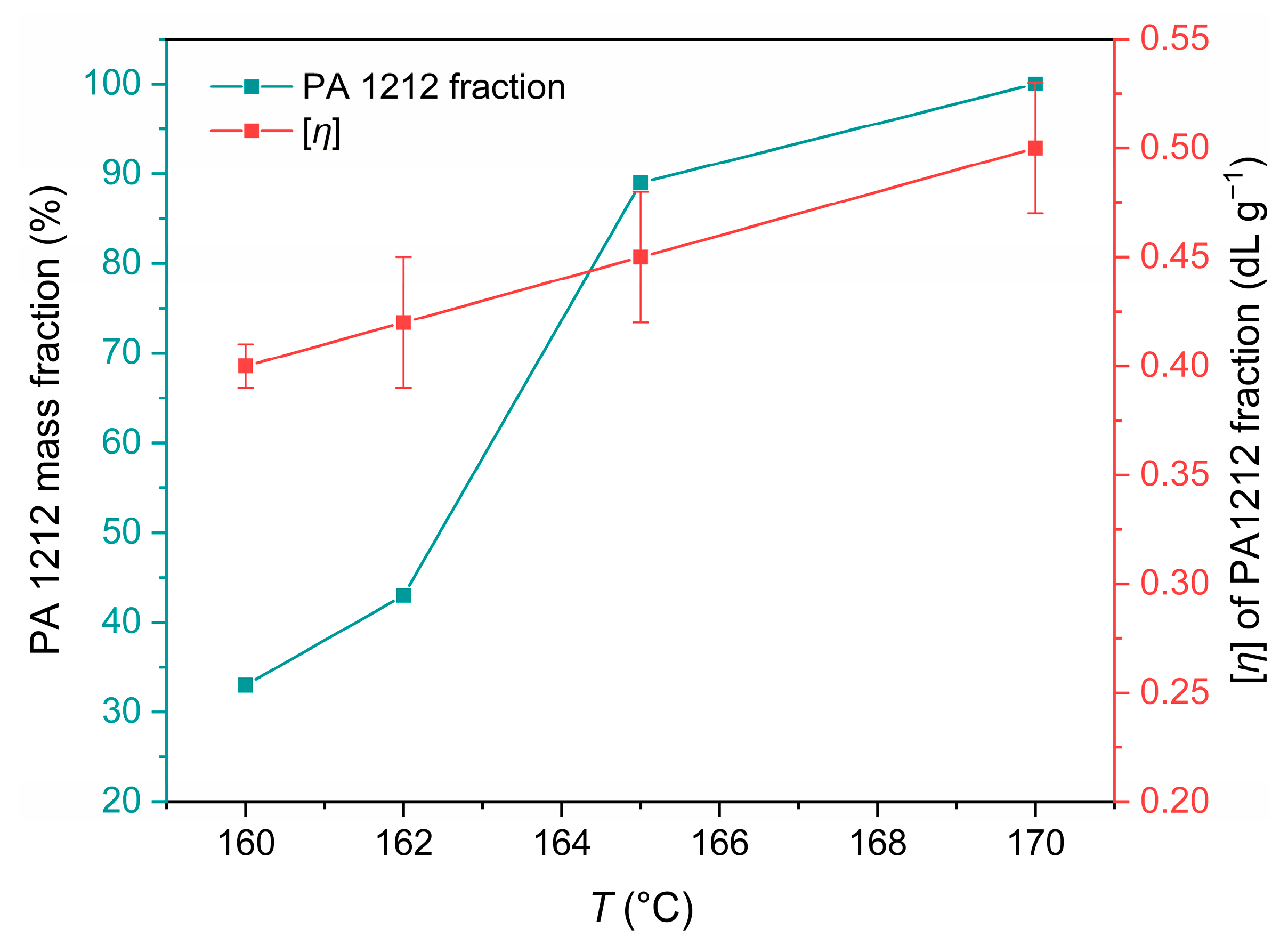

3.3.2. Effect of Reaction Temperature

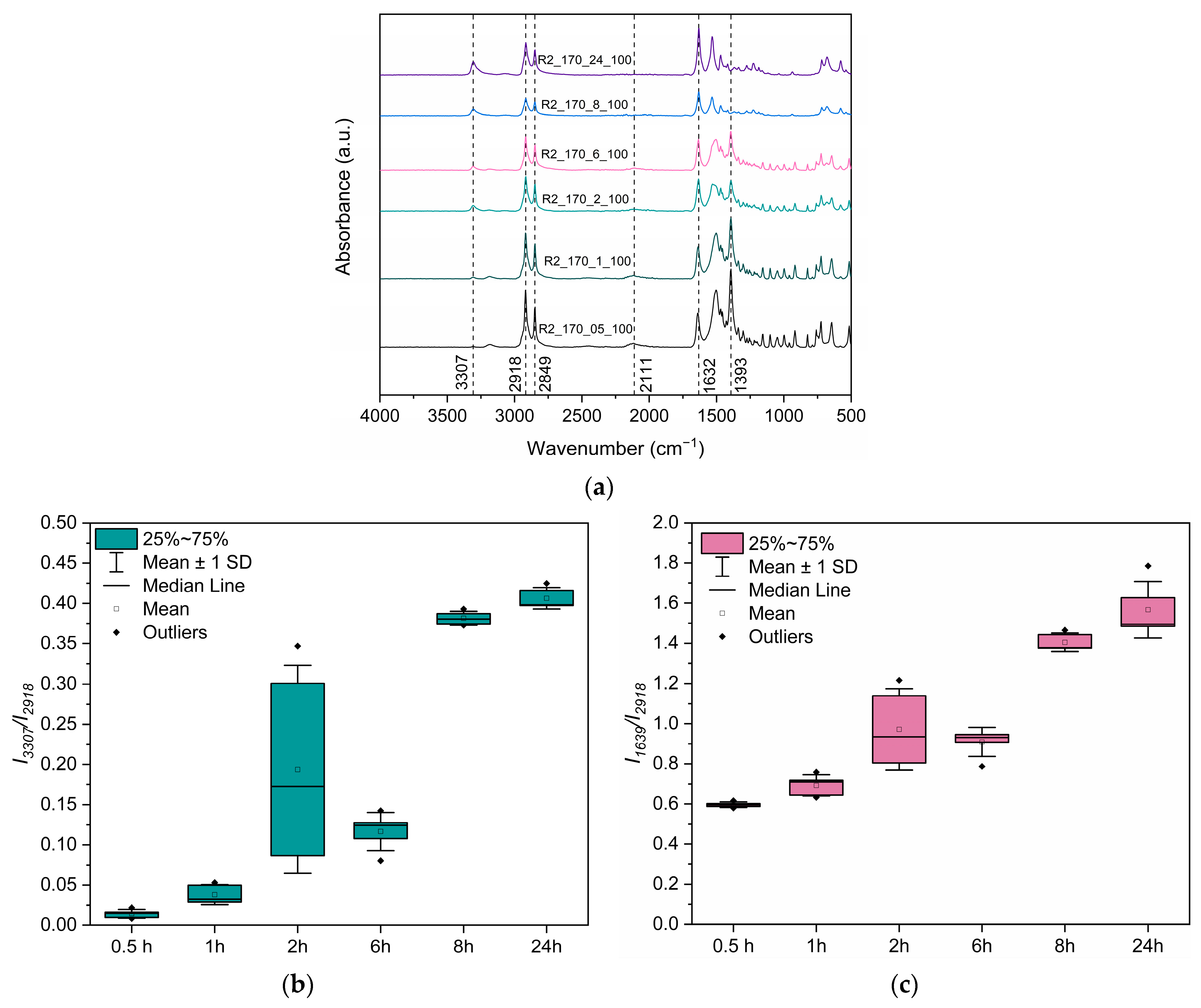

3.3.3. Assessment of the Reaction Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DSSP | Direct solid-state polymerization |

| SMT | Solid melt transition |

| DDDA | 1,12-Dodecanedioic acid |

| DMDA | 1,12-Diaminododecane |

References

- Cai, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Xiao, X.; Fang, D.; Bao, H. The Structure Evolution of Polyamide 1212 after Stretched at Different Temperatures and Its Correlation with Mechanical Properties. Polymer 2017, 117, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Spoljaric, S.; Seppälä, J. Redefining polyamide property profiles via renewable long-chain aliphatic segments: Towards impact resistance and low water absorption. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 109, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Spoljaric, S.; Seppälä, J. Renewable Polyamides via Thiol-Ene ‘Click’ Chemistry and Long-Chain Aliphatic Segments. Polymer 2018, 153, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stempfle, F.; Ortmann, P.; Mecking, S. Long-Chain Aliphatic Polymers To Bridge the Gap between Semicrystalline Polyolefins and Traditional Polycondensates. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 4597–4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayorinde, F.O.; Powers, F.T.; Streete, L.D.; Shepard, R.L.; Tabi, D.N. Synthesis of Dodecanedioic Acid from Vernonia galamensis Oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1989, 66, 690–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picataggio, S.; Rohrer, T.; Deanda, K.; Lanning, D.; Reynolds, R.; Mielenz, J.; Eirich, L.D. Metabolic Engineering of Candida Tropicalis for the Production of Long–Chain Dicarboxylic Acids. Nat. Biotechnol. 1992, 10, 894–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huf, S.; Krügener, S.; Hirth, T.; Rupp, S.; Zibek, S. Biotechnological Synthesis of Long-chain Dicarboxylic Acids as Building Blocks for Polymers. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2011, 113, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyulavska, M.; Toncheva-Moncheva, N.; Rydz, J. Biobased Polyamide Ecomaterials and Their Susceptibility to Biodegradation. In Handbook of Ecomaterials; Martínez, L.M.T., Kharissova, O.V., Kharisov, B.I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Klatte, S.; Wendisch, V.F. Redox Self-Sufficient Whole Cell Biotransformation for Amination of Alcohols. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 5578–5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Li, H.; Luo, J.; Yin, J.; Wan, Y. High-Level Productivity of α,ω-Dodecanedioic Acid with a Newly Isolated Candida viswanathii Strain. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, I.; Rimmel, N.; Schorsch, C.; Sieber, V.; Schmid, J. Production of Dodecanedioic Acid via Biotransformation of Low Cost Plant-Oil Derivatives Using Candida tropicalis. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendisch, V.F.; Mindt, M.; Pérez-García, F. Biotechnological Production of Mono- and Diamines Using Bacteria: Recent Progress, Applications, and Perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 3583–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, S.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Li, H.; Chen, K.; Ouyang, P. The Production of Biobased Diamines from Renewable Carbon Sources: Current Advances and Perspectives. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 30, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhou, C.; Zhu, N. The Nucleating Effect of Montmorillonite on Crystallization of Nylon 1212/Montmorillonite Nanocomposite. Polym. Test. 2002, 21, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.L.; Zhao, Q.X.; Liu, M.Y.; Fu, P.; Yu, Y.B.; Xu, J.W. Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Nylon 1212 Modified with Brown Corundum Ash and Solid Lubricants. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 295–297, 1573–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, J.; He, W.; Wu, H.; Qin, S.; Yu, J. Different Component Ratio of Polyamide 1212/Thermoplastic Polyurethane Blends: Effect on Phase Morphology, Mechanical Properties, Wear Resistance, and Crystallization Behavior. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2022, 35, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Huang, F.; Huang, A.; Liu, T.; Peng, X.; Wu, J.; Geng, L. Foaming Behavior of Polyamide 1212 Elastomers/Polyurethane Composites with Improved Melt Strength and Interfacial Compatibility via Chain Extension. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2023, 63, 1082–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Tang, Q.; Pan, X.; Xi, Z.; Zhao, L.; Yuan, W. Structure and Morphology of Thermoplastic Polyamide Elastomer Based on Long-Chain Polyamide 1212 and Renewable Poly(Trimethylene Glycol). Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 17502–17512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Cheng, W.; Tang, Q.; Pan, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, L.; Xi, Z.; Yuan, W. Multiblock Poly(Ether-b-Amide) Copolymers Comprised of PA1212 and PPO-PEO-PPO with Specific Moisture-Responsive and Antistatic Properties. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 53, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, Z.; Mei, S.; Chen, X.; Ding, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, X.; Cui, Z.; Fu, P.; et al. 4D Printed Thermoplastic Polyamide Elastomers with Reversible Two-Way Shape Memory Effect. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2202066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wen, J.; Fan, X.; Chen, L.; Luo, Q. Preparation Method of Nylon1212 Powder for Laser Sintering. CN104356643A, 18 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, F. Process Method for Preparing Nylon 1212. CN 201010216419, 2 January 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M. Fermented Petroleum Nylon “1212” and Its Synthesis Process. CN1255507A, 7 June 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Volokhina, A.V.; Kudryavtsev, G.I.; Skuratov, S.M.; Bonetskaya, A.K. The Polyamidation Process in the Solid State. J. Polym. Sci. 1961, 53, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampouris, E.M. New Solid State Polyamidation Process. Polymer 1976, 17, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaspyrides, C.D.; Vouyiouka, S.N. Fundamentals of Solid State Polymerization. In Solid State Polymerization; Papaspyrides, C.D., Vouyiouka, S.N., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tynan, D.G.; Papaspyrides, C.D.; Bletsos, I.V. Polymer Mixing Apparatus and Method. U.S. Patent 5941634A, 2 August 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Papaspyrides, C.D.; Kampouris, E.M. Solid-State Polyamidation of Dodecamethylenediammonium Adipate. Polymer 1984, 25, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampouris, E.M.; Papaspyrides, C.D. Solid State Polyamidation of Nylon Salts: Possible Mechanism for the Transition Solid-Melt. Polymer 1985, 26, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaspyrides, C.D.; Kampouris, E.M. Influence of Acid Catalysts on the Solid-State Polyamidation of Dodecamethylenediammonium Adipate. Polymer 1986, 27, 1433–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaspyrides, C.D. Solid-State Polyamidation of Nylon Salts. Polymer 1988, 29, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaspyrides, C.D.; Porfyris, A.D.; Vouyiouka, S.; Rulkens, R.; Grolman, E.; Poel, G.V. Solid State Polymerization in a Micro-reactor: The Case of Poly(Tetramethylene Terephthalamide). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, app.43271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shang, Y.; Huang, W.; Xue, B.; Zhang, X.; Cui, Z.; Fu, P.; Pang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, M. Synthesis of Succinic Acid-based Polyamide through Direct Solid-state Polymerization Method: Avoiding Cyclization of Succinic Acid. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 51017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Cheng, K.; Liu, T.; Li, N.; Zhang, H.; He, Y. Fully Bio-Based Poly (Pentamethylene Glutaramide) with High Molecular Weight and Less Glutaric Acid Cyclization via Direct Solid-State Polymerization. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 180, 111618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaspyrides, C.D. Solid State Polyamidation of Aliphatic Diamine-Aliphatic Diacid Salts: A Generalized Mechanism for the Effect of Polycondensation Water on Reaction Behaviour. Polymer 1990, 31, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussia, A.C.; Vouyiouka, S.N.; Porfiris, A.D.; Papaspyrides, C.D. Long-Aliphatic-Segment Polyamides: Salt Preparation and Subsequent Anhydrous Polymerization. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2010, 295, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfyris, A.D.; Papaspyrides, C.D.; Rulkens, R.; Grolman, E. Direct Solid State Polycondensation of Tetra- and Hexa-methylenediammonium Terephthalate: Scaling up from the TGA Micro-reactor to a Laboratory Autoclave. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 45080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytara, A.D.; Porfyris, A.D.; Vouyiouka, S.N.; Papaspyrides, C.D. New Aspects on the Direct Solid State Polycondensation (DSSP) of Aliphatic Nylon Salts: The Case of Hexamethylene Diammonium Dodecanoate. Polymers 2021, 13, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fang, X.; Yan, Y.; Li, Z.; Wen, Q.; Zhang, K.; Li, M.; Wu, J.; Yang, P.; Wang, J. Solid Forms of Bio-Based Monomer Salts for Polyamide 512 and Their Effect on Polymer Properties. Polymers 2024, 16, 2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Zhao, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, G.; He, Y.; Cui, Z.; Fu, P.; Pang, X.; et al. Large-Scale Fabrication of Less Entangled Polyamide by Direct Solid-State Polymerization and the Impact of Entanglement on Crystal Structure and Performance. Polymer 2025, 320, 128072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaspyrides, C.D.; Porfyris, A.D.; Rulkens, R.; Grolman, E.; Kolkman, A.J. The Effect of Diamine Length on the Direct Solid State Polycondensation of Semi-aromatic Nylon Salts. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2016, 54, 2493–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolffs, M.; Cotton, L.; Kolkman, A.J.; Rulkens, R. New Sustainable Alternating Semi-aromatic Polyamides Prepared in Bulk by Direct Solid-state Polymerization. Polym. Int. 2021, 70, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikawa, I. High Pressure Solid State Polymerization of Polyamide Monomer Crystals. In Solid State Polymerization; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; p. 181. [Google Scholar]

- Pipper, G.; Mueller, W.F.; Dauns, H. Manufacturing Process of Linear Polyamides. E.P.O. 055066A1, 6 November 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Flory, P.J. Principles of Polymer Chemistry; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA; London, UK, 1992; ISBN 978-0-8014-0134-3. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Walsh, J.J. Solid-Phase Polymerization Mechanism of Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) Affected by Gas Flow Velocity and Particle Size. Polymer 1998, 39, 6991–6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volokhina, A.V.; Kudryavtsev, G.I.; Raeva, M.; Bogdanov, M.; Kalmykova, V.; Mandrosova, F. Polycondensation Reactions in the Solid Phase: V. Polycondensation of the Diamine Salts of Terepthalic Acid and Hexahydroterepthalic Acids in the Solid State. Khim. Volokna 1964, 6, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

| End-Group Analysis | |||||||||||

| [NH3+]theor = [COO−]theοr (meq kg−1) | [NH3+] (meq kg−1) | [COO–] (meq kg−1) | D = [COO–] − [NH3+] (meq kg−1) | ||||||||

| 4644 | 4562 ± 37 | 4642 ± 99 | 80 | ||||||||

| Particle Size Distribution via Laser Diffraction | |||||||||||

| D(4,3) (μm) | D(v, 0.1) (μm) | D(v, 0.5) (μm) | D(v, 0.9) (μm) | Đ | Specific surface area (m2/g) | ||||||

| 15.65 ± 0.03 | 2.20 ± 0.07 | 11.92 ± 0.36 | 29.90 ± 0.69 | 2.32 ± 0.01 | 1.30 ± 0.01 | ||||||

| Thermal Properties | |||||||||||

| Tm (°C) | ΔHm (J g−1) | Tstep1 (°C) | Tstep2 (°C) | Step1 (%) | |||||||

| 190 ± 2 | 167 ± 12 | 200 ± 1 | 450 ± 2 | 11.0 ± 0.2 | |||||||

| ΤDSSP (°C) | N2 (mL min−1) | t1/2 (h) | Mass Loss (%) | Amine Loss (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 160 | 25 | 21.2 | 10.6 | 2.2 |

| 162 | 25 | 9.2 | 10.3 | 1.9 |

| 165 | 25 | 7.0 | 10.1 | 1.7 |

| 170 | 25 | 4.4 | 10.5 | 2.1 |

| Experiments Reactor_T_t_flow Rate | TDSSP (°C) | tDSSP (h) | Volumetric Flow Rate (mL min−1) | Gas Velocity (m min−1) [1] | [-NH2] (meq kg−1) | [-COOH] (meq kg−1) | (g mol−1) | D = [COOH] − [NH2] (meg kg−1) | [η] (dL g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Runs at 170 °C: Effect of reactor design (Comparison of R1 and R2) | |||||||||

| R1_170_24_100 | 170 | 24 | 100 | 0.16 | 46 ± 8 | 395 ± 21 | 4500 | 349 | 0.41 ± 0.02 |

| R2_170_24_100 | 170 | 24 | 100 | 0.20 | 39 ± 1 | 509 ± 50 | 3700 | 470 | 0.50 ± 0.03 |

| Effect of reaction temperature in Reactor R2 | |||||||||

| R2_160_24_100 | 160 | 24 | 100 | 0.20 | 2685 ± 101 | 3271 ± 152 | 300 | 585 | 0.40 ± 0.01 [2] |

| R2_162_24_100 | 162 | 24 | 100 | 0.20 | 2135 ± 37 | 2439 ± 40 | 400 | 304 | 0.42 ± 0.03 [2] |

| R2_165_24_100 | 165 | 24 | 100 | 0.20 | 524 ± 20 | 717 ± 35 | 1500 | 193 | 0.45 ± 0.03 [2] |

| R2_170_24_100 | 170 | 24 | 100 | 0.20 | 39 ± 1 | 509 ± 50 | 3700 | 470 | 0.50 ± 0.03 |

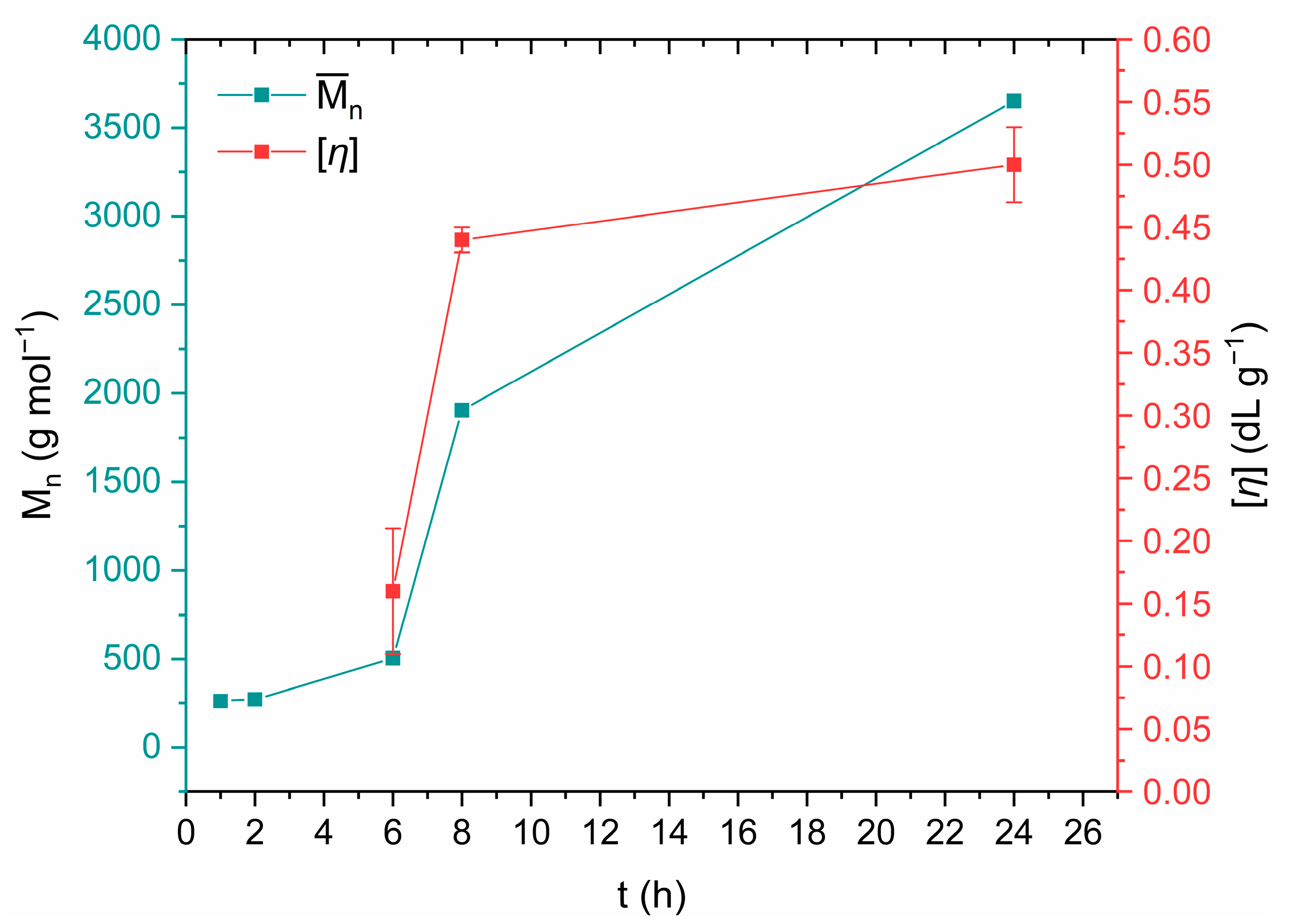

| Effect of residence time in reactor R2 at 170 °C | |||||||||

| R2_170_05_100 | 170 | 0.5 | 100 | 0.20 | n.d. [3] | n.d. [3] | n.d. [3] | n.d. [3] | n.d. [3] |

| R2_170_1_100 | 170 | 1 | 100 | 0.20 | 3701 ± 24 | 3936 ± 155 | 260 | 235 | n.d. [3] |

| R2_170_2_100 | 170 | 2 | 100 | 0.20 | 3142 ± 145 | 3595 ± 150 | 270 | 383 | n.d. [3] |

| R2_170_6_100 | 170 | 6 | 100 | 0.20 | 1718 ± 36 | 2032 ± 101 | 500 | 314 | 0.16 ± 0.05 |

| R2_170_8_100 | 170 | 8 | 100 | 0.20 | 150 ± 13 | 575 ± 7 | 1900 | 425 | 0.44 ± 0.01 |

| R2_170_24_100 | 170 | 24 | 100 | 0.20 | 39 ± 1 | 509 ± 50 | 3700 | 470 | 0.50 ± 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mytara, A.D.; Porfyris, A.D.; Papaspyrides, C.D. Direct Solid-State Polymerization of Highly Aliphatic PA 1212 Salt: Critical Parameters and Reaction Mechanism Investigation Under Different Reactor Designs. Polymers 2026, 18, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010101

Mytara AD, Porfyris AD, Papaspyrides CD. Direct Solid-State Polymerization of Highly Aliphatic PA 1212 Salt: Critical Parameters and Reaction Mechanism Investigation Under Different Reactor Designs. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010101

Chicago/Turabian StyleMytara, Angeliki D., Athanasios D. Porfyris, and Constantine D. Papaspyrides. 2026. "Direct Solid-State Polymerization of Highly Aliphatic PA 1212 Salt: Critical Parameters and Reaction Mechanism Investigation Under Different Reactor Designs" Polymers 18, no. 1: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010101

APA StyleMytara, A. D., Porfyris, A. D., & Papaspyrides, C. D. (2026). Direct Solid-State Polymerization of Highly Aliphatic PA 1212 Salt: Critical Parameters and Reaction Mechanism Investigation Under Different Reactor Designs. Polymers, 18(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010101