Toward Sustainable Polyhydroxyalkanoates: A Next-Gen Biotechnology Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

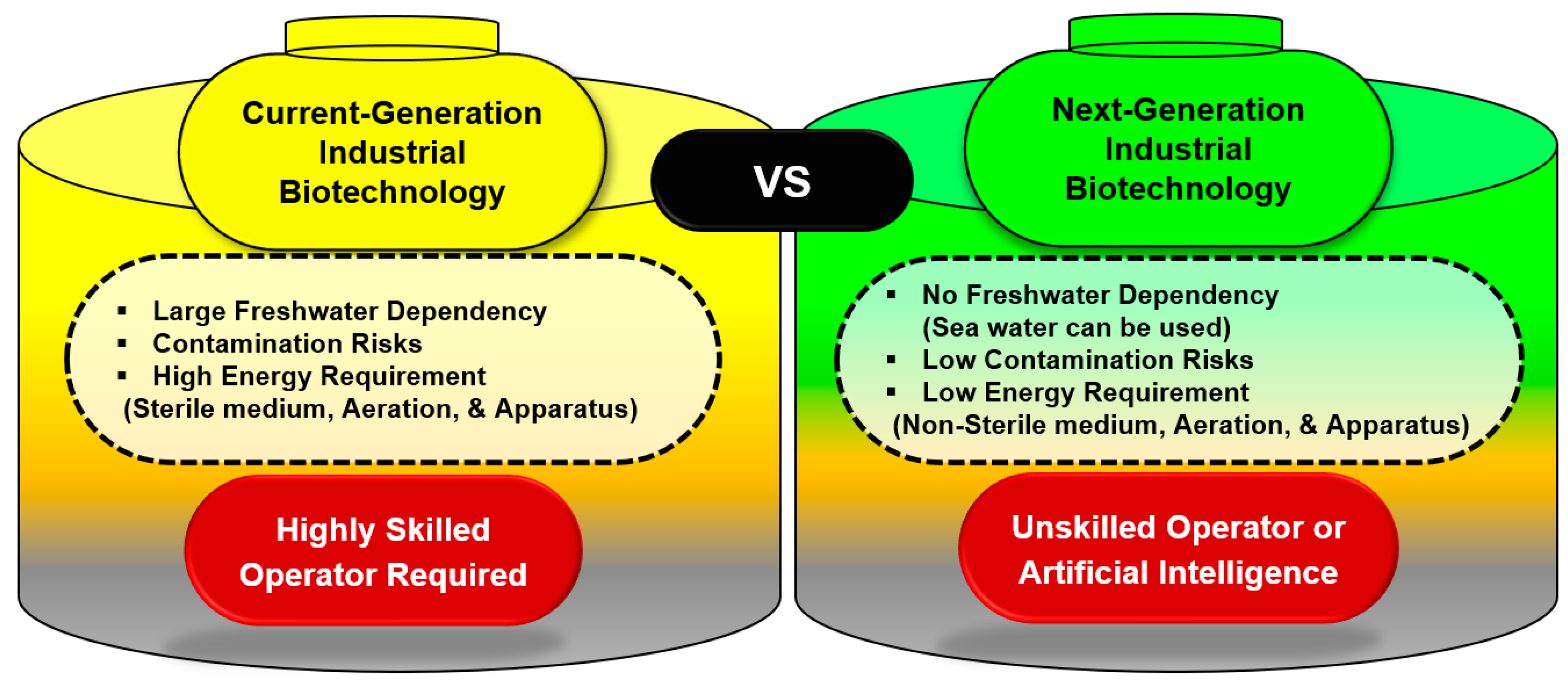

2. Current Status of Industrial Biotechnology

3. Next-Generation Industrial Biotechnology

4. PHA Production by Halophilic Archaea

4.1. PHA Production from Pure Sugars

4.2. PHA Production from Biowastes

5. PHA Production by Halophilic Bacteria

5.1. PHA Production from Sugars

5.2. PHA Production from Industrial and Agricultural Wastes

| PHA Producer | Substrate (%) | Salt (NaCl) (%) | Reactor Condition | Cell Dry Mass (g/L) | Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition (%mol Copolymer) | Content (wt%) | Yield (g/L) | ||||||

| Pure Sugars | ||||||||

| Halomonas sp. KM-1 | Glucose (10) | 0.1 | Batch | 38.4 | P(3HB) | 73.7 | 28.34 | [63] |

| Halomonas sp. O-1 | Glucose (10) | 0.1 | Batch | 6.9 | P(3HB) | 31 | 2.13 | [63] |

| Halomonas boliviensis | Glucose (2) | 4.5 | Shake flask (Fed-batch) | 44 | P(3HB) | 81 | 35.4 | [64] |

| Halomonas bluephagenesis TD01 | Glucose (3) | 5 | Shake flask | 12.88 | P(3HB) | 76.16 | 9.81 | [66] |

| Halomonas campaniensis LS21 | Glucose (1.5) | 4 | Shake flask | 27 | P(3HB) | 30 | 8.1 | [67] |

| Halomonas profundus AT1214 | Glucose (1) | 2.7 | 2-stage batch (5 L) | - | P(3HB) | - | 0.27 | [68] |

| Glucose a (1) | 2.7 | 2-stage batch (5 L) | - | P(3HB-3HV) [28 mol% 3HV] | - | 0.27 | ||

| Halomonas sp. TD01 | Glucose (3) | 6 | Continuous culture | 40 | P(3HB) | 60 | 24 | [69] |

| Glucose (3) | 6 | Continuous culture (500 L) | 112 | P(3HB) | 70 | 78.4 | [66] | |

| Glucose a (3) | 6 | Continuous culture (500 L) | 80 | P(3HB-3HV) a [12 mol% 3HV] | 70 | 56 | [70] | |

| Glucose (3) | 6 | Shake flask | 10.22 | P(3HB) | 77.68 | 7.94 | [72] | |

| Halomonas sp. TD08 pSEVA341) (blank vector) | Glucose | 6 | Shake flask | 8.61 | P(3HB-3HV) [trace 3HV] | 70.45 | 6.05 | [71] |

| Halomonas sp. TD-gltA2 (Rec.) | Glucose (3) | 6 | Shake flask | 13.53 | P(3HB) | 71.77 | 9.71 | [72] |

| Halomonas halophila CCM 3662 | Glucose (2) | 6.6 | Shake flask | 5.62 | P(3HB) | 81.5 | 4.58 | [82] |

| Cellobiose (2) | 6.6 | Shake flask | 2.86 | P(3HB) | 90.8 | 2.59 | ||

| Galactose (2) | 6.6 | Shake flask | 4.22 | P(3HB) | 80.7 | 3.41 | ||

| Halomonas elongata 2FF | Glucose (1) | 10 | Shake flask | -NR | P(3HB) | -NR | 0.4 | [73] |

| H. elongata A1 | Glucose (1) | 5 | Shake flask | 6.75 | P(3HB) | 22.81 | 2.59 | [74] |

| Cellulose (1) | 5 | Shake flask | 4.17 | P(3HB) | 11.80 | 0.49 | ||

| Halomonas venusta KT832796 | Glucose (2) | 1.5 | Single pulse feeding | 37.9 | P(3HB) | 88.12 | 33.4 (8.65-fold) | [75] |

| Glucose (2) b | 1.5 | Fed-batch (2 L) | 3.52 | P(3HB) | 70.56 | 2.48 | ||

| Halomonas cupida J9 | Glucose a | 8 | Shake flask | 5.5 | P(3HB-3HDD) | 32 | 1.76 | [76] |

| Halomonas pacifica ASL10 | Sucrose (2) + Ammonium sulphate (0.2) | (up to 170) | Shake flask | 9.59 | P(3HB-3HV) | 71.9 | 6.9 | [77] |

| Halomonas salifodiane ASL11 | Sucrose (2) + Ammonium sulfate (0.2) | (up to 170) | Shake flask | 8.86 | P(3HB-3HV) | 80.1 | 7.1 | [77] |

| Vibrio proteolyticus | Fructose (2) | 5 | Shake flask | 4.94 | P(3HB) | 54.7 | 2.7 | [80] |

| Fructose a (2) | 5 | Shake flask | 3.62 | P(3HB-3HV) [15.8 mol% 3HV] | 47.68 | 1.73 | ||

| Industrial and Agricultural Wastes | ||||||||

| Halomonas campisalis MCM B-1027 | Bagasse (1) | 4.5 | Shake flask | 0.78 | P(3HB-3HV) [5.6 mol% 3HV] | 46.5 | 0.36 | [81] |

| Banana peel (1) | 4.5 | Shake flask | 0.53 | P(3HB-3HV) [52.04 mol% 3HV] | 10.5 | 0.37 | ||

| Orange peel (1) | 4.5 | Shake flask | 0.92 | P(3HB-3HV) [52.04 mol% 3HV] | 21.5 | 0.19 | ||

| H. halophila CCM 3662 | Cheese whey hydrolysate | 6.6 | Shake flask | 8.50 | P(3HB) | 38.32 | 3.26 | [82] |

| Molasses | 6.6 | Shake flask | 4.05 | P(3HB) | 64.06 | 2.57 | ||

| H. elongata P2 | Wheat straw | 5 | Shake flask | 8.42 | P(3HB) | 5.19 | 0.44 | [74] |

| Mixed substrates | 5 | Shake flask | 7.76 | P(3HB) | 16.49 | 1.28 | ||

| Oleic acid | 5 | Shake flask | 5.76 | P(3HB) | 27.42 | 1.81 | ||

| Halomonas sp. YLGW01 | Fructose syrup (2) | 2 | Shake flask | 9.15 | P(3HB) | 94.62 | 8.65 | [66] |

| Bacillus megaterium uyuni S29 | Sugar beet molasses (1) | 1 | Shake flask | 16.7 | P(3HB) | 60 | 10.02 | [35] |

| Sugar beet molasses (5) | 0/5 | Pilot scale (500 L) | 20.4 | P(3HB) | 58.8 | 12 | [83] | |

| Halomonas TD08 (pSEVA341-thrACBilvA) c | Glycerol | 6 | Shake flask | 6.65 | P(3HB-3HV) [6.12 mol% 3HV] | 67.14 | 4.46 | [71] |

| Halomonas sp. KM-1 | Pure glycerol (2) | - | Shake flask | 4.69 | P(3HB) | 40.5 | 1.9 | [84] |

| Halomonas sp. KM-1 | Pure glycerol (5) | - | Shake flask | 5.13 | P(3HB) | 44.8 | 2,3 | [84] |

| Halomonas sp. KM-1 | Waste glycerol (3) | - | Shake flask | 4.10 | P(3HB) | 39.0 | 1.6 | [84] |

| Halomonas desertis G11 | Glycerol (1) | 5 | Shake flask | 2.29 | P(3HB-3HV) [52 mol% 3HV] | 68 | 1.54 | [57] |

| Halomonas cupida J9 | Glycerol | 10 | Shake flask | 3.5 | P(3HB-3HDD) | 29 | 1.01 | [76] |

| Halomonas sp. YLGW01 | Glycerol (2) | 2 | Shake flask | 17.5 | P(3HB-3HV) [13 mol% 3HV] | 60.0 | 10.5 | [86] |

| Halomonas hydrothermalis MTCC5445 | Glycerol (5) (+Peptone) | 3.5 | Batch | - | P(3HB) | - | 2.59 | [87] |

| Glycerol (3) (+Peptone) | 3.5 | Batch | - | P(3HB) | - | 2.61 | ||

| H. hydrothermalis SM-P-3M | Jatropha biodiesel byproducts (2) | 0.5 | Batch | 0.40 | P(3HB) | 75.8 | 0.30 | [88] |

| Bacillus sorensis SM-P-1S | Jatropha biodiesel byproducts (2) | 0.5 | Batch | 0.283 | P(3HB) | 71.8 | 0/20 | [88] |

| Halomonas alkaliantarctica DSM 15686 | Biodiesel-derived glycerol (85%) (1) | 1.94 | Shake flask | - | P(3HB-3HV) [2.77 mol% 3HV] | 11 | 3.5 b | [89] |

| Biodiesel-derived glycerol (85%) (5) | 1.94 | Shake flask | - | P(3HB-3HV) [1.82 mol% 3HV] | 18 | 5.8 b | ||

| Biodiesel-derived glycerol (85%) (8) | 1.94 | Shake flask | - | P(3HB-3HV) [1.65 mol% 3HV] | 9 | 3.0 b | ||

| Halomonas daqingensis | Algal biodiesel waste residue (Crude glycerol) (3) | 3.5 | Batch | 0.362 | P(3HB-3HV) | 65.2 | 0.236 | [90] |

| Salinivibrio sp. M318 | Glycerol + waste fish oil and sauce (as nitrogen source) (3) | 4.5 | Fed-batch | 5.7 | P(3HB), P(3HB-3HV), P(3HB-4HB) a [2.9 mol% 3HV] | 52.8 | 3 | [91] |

| Halomonas organivorans CCM 7142 | Waste frying oil (2) | 4 | Shake flask | 3.64 | P(3HB) | 61.98 | 2.26 | [91] |

| Halomonas hydrothermalis CCM 7104 | Waste frying oil (2) | 8 | Shake flask | 1.60 | P(3HB) | 23.76 | 0.38 | [91] |

| Waste frying oil (2) | 8 | Shake flask | 2.75 | P(3HB-3HV) a [7.16 mol% 3HV] | 47.17 | 1.29 | ||

| Halomonas neptunia CCM 7107 | Waste frying oil (2) | 6 | Shake flask | 2.28 | P(3HB) | 55.71 | 1.27 | [91] |

| Waste frying oil (2) | 8 | Shake flask | 1.23 | P(3HB-3HV) a [26.07 mol% 3HV] | 15.85 | 0.19 | ||

| Halomonas bluephagensis TD01 | Glucose (3) (60MMG medium with γ-butyrolactone + waste corn steep liquor; waste gluconate) | 6 | Continuous culture (Pilot:5 m3) | 100 | P(3HB-4HB) [13.5 mol% 4HB] | 60 | 0.6 | [92] |

- Archaeal feedstocks generally yield much higher PHA concentrations (up to 77.8 g/L) than bacterial feedstocks (max 10.5 g/L).

- Bacterial systems achieve higher PHA content (95.26%) than archaea (max 87.5%).

- Crude glycerol and sugar beet molasses appear to be the best bacterial feedstocks for industrial feasibility, while rice bran–corn starch mix and hydrolyzed whey dominate archaeal production.

- Waste valorization is a key advantage in both cases, although archaea demonstrate broader substrate adaptability.

- Archaea are better suited for large-scale biopolymer production, while bacteria are more cost-effective in non-sterile industrial settings.

6. Robust Contender for PHA Production

- Halomonas spp. as an optimal chassis for PHA production: Halomonas species, particularly H. bluephagenesis and H. campaniensis, have been identified as highly suitable hosts for PHA biosynthesis due to their fast growth, high tolerance, and ease of genetic manipulation [69,96]. These bacteria can thrive under unsterile conditions, with H. campaniensis reported to sustain growth in artificial seawater for over two months [32,97,98].

- Genetic engineering strategies: Recent advancements in the genetic modification of Halomonas spp. involve the development of unique plasmids carrying inducible gene expression systems controlled by constitutive promoters [99,100,101]. Tools like CRISPR/Cas9 and CRISPRi have been employed to regulate metabolic flux, particularly the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydride/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH/NAD+) ratio, by deleting flavoprotein genes to enhance PHA synthesis in H. bluephagenesis [13,102,103,104,105]. Additionally, H. bluephagenesis has been engineered to optimize oxygen uptake under low oxygen conditions via inducible promoter control [106].

- Enhancing PHA production through morphological and metabolic engineering: Genetic modifications, including the overexpression of sulA (encoding cell division inhibitor protein) or minCD and deletion of mreB, have resulted in higher cell densities [1,67,107,108]. In addition to the downstream processing techniques, these strategies promote the formation of larger cells containing larger PHA granules [66]. Moreover, self-flocculation mechanisms have been optimized to facilitate easy harvesting [109]. Synchronizing cell autolysis with substrate exhaustion has also been explored to improve the cost efficiency of PHA synthesis [110].

- Industrial-scale achievements and economic feasibility: Studies have successfully produced PHA copolymers containing monomers, such as 3HB, 4HB, HHx, and functionally modified 3-hydroxyhex-5-enoate (HHxE) [92,111,112]. This has enabled industrial-scale PHA production, reaching biomass levels of 100 g/L and copolymer yields of 60 wt% in 5000 L reactors [92,113]. With these next-generation biotechnological advancements, the production cost of PHA is projected to decrease. The cost of P(3HB-co-4HB) production by genetically engineered H. bluephagenesis was reported to be USD 1.98 /kg by replacing γ-butyrolactone with unrelated carbon sources. The production cost was envisaged to be reduced further to 1.66–1.94 /kg for slaughtering waste streams. It was also observed that replacing glucose with gluconate can help to achieve a USD 0.75/kg cost-reduction [88].

| Distinctive Traits | References |

|---|---|

| Extremophilic bacteria with high salt tolerance and higher oxygen uptake, even at extremely low oxygen levels, are suitable for industrial PHA production | [32,69,92,96,98,106] |

| Microbes engineered with a constitutive promoter-mediated genetic system | [99,100,101,102] |

| Modified cell shape (filamentous) with higher density, larger PHA granules for easy recovery—downstream processing achieved by deleting gene (mreB) in association with overexpression of genes of cell division (minCD or sulA) | [66,67,107,108,109] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 and CRISPRi-based multi-purpose PHA synthase and manipulating carbon flux and energy regulation (NADH/NAD+), enhanced acetyl-CoA diversion leading to enhanced PHA yield | [13,103,104,105] |

| Diversity of PHA copolymers with monomers of 3-hydroxybutyrate, 4-hydroxybutyrate, and 3-hydroxy hexanoate | [89,111,112] |

| Commercial level PHA production: 5000 L reactors | [92,113] |

7. Perspectives

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PHA | Polyhydroxyalkanoates |

| NGIB | Next-Generation Industrial Biotechnology |

| scl-PHA | Short-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoate |

| mcl-PHA | Medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoate |

| P(3HB) | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) |

| P(3HB-3HV) | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-3-hydroxyvalerate) |

| CDW | Cell dry weight |

| M.Wt. | Molecular weight |

| SCB | Sugarcane bagasse |

| NADH/NAD+ | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydride/Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats Cas protein systems |

| CRISPRi | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats interference |

References

- Kalia, V.C.; Patel, S.K.S.; Karthikeyan, K.K.; Jeya, M.; Kim, I.W.; Lee, J.-K. Manipulating microbial cell morphology for the sustainable production of biopolymers. Polymers 2024, 16, 4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, V.C.; Patel, S.K.S.; Krishnamurthi, P.; Singh, R.V.; Lee, J.-K. Exploiting latent microbial potentials for producing polyhydroxyalkanoates: A holistic approach. Environ. Res. 2025, 259, 120895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koller, M. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) biopolyesters by extremophiles. MOJ Polym. Sci. 2017, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, S.; Singh, D. Microbial polyhydroxyalkanoates from extreme niches: Bioprospection status, opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 147, 1255–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obulisamy, P.; Mehariya, S. Polyhydroxyalkanoates from extremophiles: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 325, 124653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obruča, S.; Dvořák, P.; Sedláček, P.; Koller, M.; Sedlář, K.; Pernicová, I.; Šafránek, D. Polyhydroxyalkanoates synthesis by halophiles and thermophiles: Towards sustainable production of microbial bioplastics. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 58, 107906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Ouyang, P.; Liu, X. Next-generation industrial biotechnology for low-cost mass production of PHA. Trends Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourmentza, C.; Placido, J.; Venetsaneas, N.; Burniol-Figols, A.; Varrone, C.; Gavala, H.; Reis, M. Recent advances and challenges towards sustainable polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, M. Linking food industry to “green plastics”—Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) biopolyesters from agro-industrial by-products for securing food safety. Appl. Food Biotechnol. 2019, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcântara, J.M.G.; Distante, F.; Storti, G.; Moscatelli, D.; Morbidelli, M.; Sponchioni, M. Current trends in the production of biodegradable bioplastics: The case of polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 42, 107582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panuschka, S.; Drosg, B.; Ellersdorfer, M.; Meixner, K.; Fritz, I. Photoautotrophic production of poly-hydroxybutyrate—First detailed cost estimations. Algal Res. 2019, 41, 101558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstutz, V.; Zinn, M. Syngas as a sustainable carbon source for PHA production. In The Handbook of Polyhydroxyalkanoates; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 377–416. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Y.; Perez, V.; Lopez, J.; Bordel, S.; Firmino, P.; Lebrero, R.; Munoz, R. Coupling biogas with PHA biosynthesis. In The Handbook of Polyhydroxyalkanoates; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 357–376. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-K.; Patel, S.K.S.; Sung, B.H.; Kalia, V.C. Biomolecules from municipal and food industry wastes: An overview. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 298, 22346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Jiang, X. Next generation industrial biotechnology based on extremophilic bacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 50, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Wang, Y.; Tong, Y.; Chen, G. Grand challenges for industrializing polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs). Trends Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 953–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.P.; Wu, F.; Chen, G. Next-generation industrial biotechnology-transforming the current industrial biotechnology into competitive processes. Biotechnol. J. 2019, 14, e1800437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-Q. A microbial polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) based bio- and materials industry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 2434–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahlawat, G.; Srivastava, A.K. Model-based nutrient feeding strategies for the increased production of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) by Alcaligenes latus. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 183, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikawa, H.; Matsumoto, K.; Fujiki, T. Polyhydroxyalkanoate production from sucrose by Cupriavidus necator strains harboring csc genes from Escherichia coli W. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 7497–7507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chung, A.; Chen, G.Q. Synthesis of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoate homopolymers, random copolymers, and block copolymers by an engineered strain of Pseudomonas entomophila. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017, 6, 1601017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Y.K.; Show, P.L.; Ooi, C.W.; Ling, T.C.; Lan, J.C.W. Current trends in polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) biosynthesis: Insights from the recombinant Escherichia coli. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 180, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.E.; Park, S.J.; Kim, W.J.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, H.; Shin, J.; Lee, S.Y. One-step fermentative production of aromatic polyesters from glucose by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli strains. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, H.W.; Hahn, S.K.; Chang, Y.K.; Chang, H.N. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) by high cell density fed-batch culture of Alcaligenes eutrophus with phosphate limitation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1997, 55, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, S.Y.; Han, K. Cloning of the Alcaligenes latus polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis genes and use of these genes for enhanced production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 4897–4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.Y.; Rhie, M.N.; Kim, H.T.; Joo, J.C.; Cho, I.J.; Son, J.; Jo, S.Y.; Sohn, Y.J.; Baritugo, K.A.; Pyo, J.; et al. Metabolic engineering for the synthesis of polyesters: A 100-year journey from polyhydroxyalkanoates to non-natural microbial polyesters. Metab. Eng. 2020, 58, 47–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Yin, J.; Chen, G.Q. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering: Production, Isolation and Purification of Industrial Products; Pandey, A., Negi, S., Soccol, C.R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 655–692. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez, B.A.; Raghavan, V.; Tartakovsky, B. A comparative analysis of biopolymer production by microbial and bioelectrochemical technologies. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 16105–16118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, S.; Khan, M.T.; Moholkar, V.S. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs): Mechanistic Insights and Contributions to Sustainable Practices. Encyclopedia 2024, 5, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillaguaman, J.; Guzmán, H.; Van-Thuoc, D.; Hatti-Kaul, R. Synthesis and production of polyhydroxyalkanoates by halophiles: Current potential and future prospects. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 1687–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, M.; Chiellini, E.; Braunegg, G. Study on the production and re-use of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) and extracellular polysaccharide by the archaeon Haloferax mediterranei strain DSM 1411. Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q. 2015, 29, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Chen, J.C.; Wu, Q.; Chen, G.Q. Halophiles, coming stars for industrial biotechnology. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waditee-Sirisattha, R.; Kageyama, H.; Takabe, T. Halophilic microorganism resources and their applications in industrial and environmental biotechnology. AIMS. Microbiol. 2016, 2, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemechko, P.; Le Fellic, M.; Bruzaud, S. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrateco-3-hydroxyvalerate) using agro-industrial effluents with tunable proportion of 3-hydroxyvalerate monomer units. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 128, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.T.; Song, H.; Raschbauer, M.; Emerstorfer, F.; Omann, M.; Stelzer, F.; Neureiter, M. Utilization of desugarized sugar beet molasses for the production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) by halophilic Bacillus megaterium uyuni S29. Process Biochem. 2019, 86, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.M.; Yepes-Perez, M.; Contreras, K.A.C.; Moreno, P.E.Z. Production of poly (3- hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) by Bacillus megaterium LVN01 using biogas digestate. Appl. Microbiolog. 2024, 4, 1057–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, V.; Lebrero, R.; Munoz, R.; Perez, R. The fundamental role of pH in CH4 bioconversion into polyhydroxybutyrate in mixed methanotrophic cultures. Chemosphere 2024, 355, 141832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Q.; Wang, Z.; Liu, B.; Liu, S.; Huang, H.; Chen, Z. Enrichment performance and salt tolerance of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) producing mixed cultures under different saline environments. Environ. Res. 2024, 251, 118722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Huang, J.; Cui, R.; Xu, Y.; Song, Z. Genetic engineering strategies for sustainable polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production from carbon-rich wastes. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 30, 103069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Liu, S. The production, recovery, and valorization of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) based on circular bioeconomy. Biotechnol. Adv. 2024, 72, 108340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atares, L.; Chiralt, A.; Gonzalez-Martínez, C.; Vargas, M. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates for biodegradable food packaging applications using Haloferax mediterranei and agrifood wastes. Foods 2024, 13, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacon, M.; Wongsirichot, P.; Winterburn, J.; Dixon, N. Genetic and process engineering for polyhydroxyalkanoate production from pre-and post-consumer food waste. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2024, 85, 103024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizki, W.O.S.; Ratnaningsih, E.; Andini, D.G.T.; Komariah, S.; Simbara, A.T.; Hertadi, R. Physicochemical characterization of biodegradable polymer polyhydroxybutyrate from halophilic bacterium local strain Halomonas elongata. Global J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2024, 10, 1117–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aynsley, M.; Hofland, A.; Morris, A.J.; Montague, G.A.; Di Massimo, C. Artificial intelligence and the supervision of bioprocesses (real-time knowledge-based systems and neural networks). Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 1993, 48, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nikodinovic-Runic, J.; Guzik, M.; Kenny, S.T.; Babu, R.; Werker, A.; Connor, K.E. Carbon-rich wastes as feedstocks for biodegradable polymer (polyhydroxyalkanoate) production using bacteria. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 84, 139–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danis, O.; Ogan, A.; Tatlican, P.; Attar, A.; Cakmakci, E.; Mertoglu, B.; Birbir, M. Preparation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-cohydroxyvalerate) films from halophilic archaea and their potential use in drug delivery. Extremophiles 2015, 19, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Lu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, J.; Xiang, H. Molecular characterization of the phaECHm genes, required for biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) in the extremely halophilic archaeon Haloarcula marismortui. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 6058–6065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don, T.-M.; Chen, C.W.; Chan, T.-H. Preparation and characterization of poly (hydroxyalkanoate) from the fermentation of Haloferax mediterranei. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2006, 17, 1425–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Han, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, J.; Xiang, H. Genetic and biochemical characterization of the poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) synthase in Haloferax mediterranei. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 4173–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Rao, Z.; Xue, Y.; Gong, P.; Ji, Y.; Ma, Y. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3- hydroxyvalerate) production by Haloarchaeon Halogranum amylolyticum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 7639–7649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgaonkar, B.; Bragança, J. Biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) by Halogeometricum borinquense strain E3. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 78, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahansaria, R.; Dhara, A.; Saha, A.; Haldar, S.; Mukherjee, J. Production enhancement and characterization of the polyhydroxyalkanoate produced by Natrinema ajinwuensis (as synonym) ≡ Natrinema altunense strain RM-G10. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 1480–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.W.; Don, T.-M.; Yen, H.-F. Enzymatic extruded starch as a carbon source for the production of poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) by Haloferax mediterranei. Process Biochem. 2006, 41, 2289–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.-Y.; Duan, K.-J.; Huang, S.-Y.; Chen, C.W. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates from inexpensive extruded rice bran and starch by Haloferax mediterranei. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 33, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koller, M.; Hesse, P.; Bona, R.; Kutschera, C.; Atlic, A.; Braunegg, G. Potential of various archae- and eubacterial strains as industrial polyhydroxyalkanoate producers from whey. Macromol. Biosci. 2007, 7, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koller, M.; Hesse, P.; Bona, R.; Kutschera, C.; Atlic, A.; Braunegg, G. Biosynthesis of high quality polyhydroxyalkanoate co-and terpolyesters for potential medical application by the archaeon Haloferax mediterranei. Macromol. Symp. 2007, 253, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Pramanik, A.; Maji, S.; Haldar, S.; Mukhopadhyay, U.; Mukherjee, J. Utilization of vinasse for production of poly-3-(hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate) by Haloferax mediterranei. AMB Express 2012, 2, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Saha, J.; Haldar, S.; Bhowmic, A.; Mukhopadhyay, U.; Mukherjee, J. Production of poly-3-(hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate) by Haloferax mediterranei using rice-based ethanol stillage with simultaneous recovery and re-use of medium salts. Extremophiles 2014, 18, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, A.; Mitra, A.; Arumugam, M.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Sadhukhan, S.; Ray, A.; Haldar, S.; Mukhopadhyay, U.K.; Mukherjee, J. Utilization of vinasse for the production of polyhydroxybutyrate by Haloarcula marismortui. Folia Microbiol. 2012, 57, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafadi, D.; Al-Mashaqbeh, O. A one-stage cultivation process for the production of poly-3-(hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate) from olive mill wastewater by Haloferax mediterranei. New Biotechnol. 2017, 34, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgaonkar, B.; Bragança, J. Utilization of Sugarcane Bagasse by Halogeometricum borinquense strain E3 for biosynthesis of Poly(3- hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate). Bioengineering 2017, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgaonkar, B.; Mani, K.; Bragança, J. Sustainable bioconversion of cassava waste to poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) by Halogeometricum borinquense strain E3. J. Polym. Environ. 2019, 27, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.-X.; Shi, L.-H.; Kawata, Y. Metabolomics-based component profiling of Halomonas sp. KM-1 during different growth phases in poly (3-hydroxybutyrate) production. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 140, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillaguamán, J.; Doan-Van, T.; Guzmán, H.; Guzmán, D.; Martín, J.; Everest, A.; Hatti-Kaul, R. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) production by Halomonas boliviensis in fed-batch culture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 78, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; Oh, S.J.; Hwang, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Shin, N.; Bhatia, S.K.; Jeon, J.M.; Yoon, J.J.; Yoo, J.; Ahn, J.; et al. Polyhydroxybutyrate production from crude glycerol using a highly robust bacterial strain Halomonas sp. YLGW01. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 236, 123997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, R.; Ning, Z.-Y.; Lan, Y.-X.; Chen, J.-C.; Chen, G.-Q. Manipulation of polyhydroxyalkanoate granular sizes in Halomonas bluephagenesis. Metab. Eng. 2019, 54, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.-R.; Yao, Z.-H.; Chen, G.-Q. Controlling cell volume for efficient PHB production by Halomonas. Metab. Eng. 2017, 44, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Colin, C.; Raguenes, G.; Cozien, J.; Guezennec, J. Halomonas profundus sp. nov., a new PHA-producing bacterium isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent shrimp. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 104, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Xue, Y.S.; Aibaidula, G.; Chen, G.Q. Unsterile and continuous production of polyhydroxybutyrate by Halomonas TD01. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 8130–8136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Tan, D.; Aibaidula, G.; Wu, Q.; Chen, J.; Chen, G. Development of Halomonas TD01 as a host for open production of chemicals. Metab. Eng. 2014, 23, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Wu, Q.; Chen, J.C.; Chen, G.Q. Engineering Halomonas TD01 for the low-cost production of polyhydroxyalkanoates. Metab. Eng. 2014, 26, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Lv, L.; Chen, G.-Q. Engineering Halomonas species TD01 for enhanced polyhydroxyalkanoates synthesis via CRISPRi. Microb. Cell Factories 2017, 16, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, A.; Floare, C.; Borodi, G.; Leopold, N.; Kasco, I.; Cadar, O.; Banciu, H. Physical and chemical detection of polyhydroxybutyrate from Halomonas elongata strain 2FFF. New Front. Chem. 2017, 26, S4_OP3. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, G. Biodegradable polyhydroxyalkanoates production from wheat straw by recombinant Halomonas elongata A1. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 187, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, A.; Punil Kumar, H.; Mutturi, S.; Vijayendra, S. Fed-batch strategies for production of PHA using a native isolate of Halomonas venusta KT832796 Strain. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 184, 935–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, S.; Huo, K.; Chen, Y.; Guo, H.; Wong, S.; Liu, R.; Yang, C. Unsterile production of a polyhydroxyalkanoate copolymer by Halomonas cupida J9. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 223, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-malek, F.; Farag, A.; Omar, S.; Khairy, H. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) from Halomonas pacifica ASL10 and Halomonas salifodiane ASL11 isolated from Mariout salt lakes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 1318–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramezani, M.; Amoozegar, M.A.; Ventosa, A. Screening and comparative assay of poly-hydroxyalkanoates produced by bacteria isolated from the Gavkhooni Wetland in Iran and evaluation of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate production by halotolerant bacterium Oceanimonas sp. GK1. Ann. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.; Tan, B.; Li, Z. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates by a moderately halophilic bacterium of Salinivibrio sp. TGB10. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 186, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.W.; Song, H.S.; Moon, Y.M.; Hong, Y.-G.; Bhatia, S.K.; Jung, H.-R.; Choi, T.-R.; Yang, S.-Y.; Park, H.-Y.; Choi, Y.-K.; et al. Polyhydroxybutyrate production in halophilic marine bacteria Vibrio proteolyticus isolated from the Korean peninsula. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 42, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.O.; Kanekar, P.P.; Jog, J.P.; Sarnaik, S.S.; Nilegaonkar, S.S. Production of copolymer, poly (hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate) by Halomonas campisalis MCM B-1027 using agro-wastes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 72, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucera, D.; Pernicova, I.; Kovalcik, A.; Koller, M.; Mullerova, L.; Sedlacek, P.; Mravec, F.; Nebesarova, J.; Kalina, M.; Marova, I.; et al. Characterization of the promising poly (3-hydroxybutyrate) producing halophilic bacterium Halomonas halophila. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 256, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.; Sykacek, E.; O’Connor, K.; Omann, M.; Mundigler, N.; Neureiter, M. Pilot scale production and evaluation of mechanical and thermal properties of P (3HB) from Bacillus megaterium cultivated on desugarized sugar beet molasses. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 139, 51503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, Y.; Aiba, S. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) production by isolated Halomonas sp. KM-1 using waste glycerol. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010, 74, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammami, K.; Souissi, Y.; Souii, A.; Ouertani, A.; El-Hidri, D.; Jabberi, M.; Chouchane, H.; Mosbah, A.; Masmoudi, A.S.; Cherif, A.; et al. Extremophilic bacterium Halomonas desertis G11 as a cell factory for Poly-3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate copolymer’s production. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 878843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Bhatia, S.; Gurav, R.; Choi, T.; Kim, H.; Song, H.; Park, J.; Han, Y.; Lee, S.; Park, S.; et al. Fructose based hyper production of poly-3- hydroxybutyrate from Halomonas sp. YLGW01 and impact of carbon sources on bacteria morphologies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Mishra, S. Natural sea salt based polyhydroxyalkanoate production by wild Halomonas hydrothermalis strain. Fuel 2022, 311, 122593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastav, A.; Mishra, S.K.; Shethia, B.; Pancha, I.; Jain, D.; Mishra, S. Isolation of promising bacterial strains from soil and marine environment for polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) production utilizing Jatropha biodiesel byproduct. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2010, 47, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Możejko-Ciesielska, J.; Moraczewski, K.; Czaplicki, S. Halomonas alkaliantarctica as a platform for poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) production from biodiesel-derived glycerol. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2024, 16, e13225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Mishra, S. Efficient production of polyhydroxyalkanoate through halophilic bacteria utilizing algal biodiesel waste residue. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 624859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernicova, I.; Kucera, D.; Nebesarova, J.; Kalina, M.; Novackova, I.; Koller, M.; Obruca, S. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates on waste frying oil employing selected Halomonas strains. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 292, 122028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Huang, W.; Wang, D.; Chen, F.; Yin, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, H.; Chen, G. Pilot scale-up of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) production by Halomonas bluephagenesis via cell growth adapted optimization process. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13, 1800074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van-Thuoc, D.; Huu-Phong, T.; Minh-Khuong, D.; Hatti-Kaul, R. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) production by a moderate Halophile Yangia sp. ND199 using glycerol as a carbon source. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015, 175, 3120–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, V.C.; Patel, S.K.S.; Shanmugam, R.; Lee, J.-K. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Trends and advances toward biotechnological applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 326, 124737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalia, V.C.; Patel, S.K.S.; Lee, J.-K. Exploiting polyhydroxyalkanoates for biomedical applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.T.; Ling, C.; Yang, T.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Deng, H.; Wu, Q.; Chen, J.; Chen, G.Q. A seawater based open and continuous process for polyhydroxyalkanoates production by Halomonas campaniensis LS21. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2014, 7, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillaguaman, J.; Delgado, O.; Mattiasson, B.; Hatti-Kaul, R. Poly(b-hydroxybutyrate) production by a moderate halophile, Halomonas boliviensis LC1. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2006, 38, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlacek, P.; Slaninova, E.; Koller, M.; Nebesarova, J.; Marova, I.; Krzyzanek, V.; Obruca, S. PHA granules help bacterial cells to preserve cell integrity when exposed to sudden osmotic imbalances. New Biotechnol. 2019, 49, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Rocha, R.; Martínez-García, E.; Calles, B.; Chavarría, M.; Arce-Rodríguez, A.; de Las Heras, A.; Paez-Espino, A.D.; Durante-Rodríguez, G.; Kim, J.; Nikel, P.I.; et al. The Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA): A coherent platform for the analysis and deployment of complex prokaryotic phenotypes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D666–D675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Li, T.; Ji, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Chen, G.Q.; Lou, C.; Ouyang, Q. Engineering of core promoter regions enables the construction of constitutive and inducible promoters in Halomonas sp. Biotechnol. J. 2016, 11, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, H.M.; Chen, X.; Li, T.; Wu, Q.; Ouyang, Q.; Chen, G.Q. Novel T7-like expression systems used for Halomonas. Metab. Eng. 2017, 39, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Ling, C.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, T.; Yin, J.; Guo, Y.; Chen, G.Q. CRISPR/Cas9 editing genome of extremophile Halomonas spp. Metab. Eng. 2018, 47, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.Q.; Jiang, X.R. Engineering microorganisms for improving polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 53, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Qiao, G.Q.; Shuai, B.W.; Olavarria, K.; Yin, J.; Xiang, R.J.; Song, K.N.; Shen, Y.H.; Guo, Y.; Chen, G.Q. Engineering NADH/NAD+ ratio in Halomonas bluephagenesis for enhanced production of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA). Metab. Eng. 2018, 49, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagong, H.Y.; Son, H.F.; Choi, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, K.J. Structural insights into polyhydroxyalkanoates biosynthesis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2018, 43, 790–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, P.F.; Wang, H.; Hajnal, I.; Wu, Q.; Guo, Y.; Chen, G.Q. Increasing oxygen availability for improving poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) production by Halomonas. Metab. Eng. 2018, 45, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.R.; Chen, G.Q. Morphology engineering of bacteria for bio-production. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Ling, C.; Hajnal, I.; Wu, Q.; Chen, G.Q. Construction of Halomonas bluephagenesis capable of high cell density growth for efficient PHA production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 4499–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Qiao, G.Q.; Shuai, B.W.; Song, K.N.; Yao, W.X.; Jiang, X.R.; Chen, G.Q. Engineering self-flocculating Halomonas campaniensis for wastewaterless open and continuous fermentation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 116, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajnal, I.; Chen, X.; Chen, G.Q. A novel cell autolysis system for cost competitive downstream processing. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 9103–9110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Hu, D.; Yin, J.; Huang, W.; Xiang, R.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Han, J.; Chen, G.Q. Stimulus response-based fine-tuning of polyhydroxyalkanoate pathway in Halomonas. Metab. Eng. 2020, 57, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.P.; Yan, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.B.; Wu, Q.; Jiang, X.R.; Chen, G.Q. Biosynthesis of functional polyhydroxyalkanoates by engineered Halomonas bluephagenesis. Metab. Eng. 2020, 59, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.B.; Yin, J.; Ye, J.; Zhang, H.; Che, X.; Ma, Y.; Chen, G.Q. Engineering Halomonas bluephagenesis TD01 for unsterile production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate). Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 244, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, M. Established and advanced approaches for recovery of microbial polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) biopolyesters from surrounding microbial biomass. EuroBiotech J. 2020, 4, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PHA Producer | Substrate (%) | Salt (NaCl) (%) | Reactor | Cell Dry Mass (g/L) | Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition (%mol Copolymer) | Content (wt%) | Yield (g/L) | ||||||

| Pure Sugars | ||||||||

| Haloarcula marismortui ATCC 43049 (33960/pWLEC) | Glucose (2) | 20 | Shake flask | 15.4 | P(3HB) | 18 | 2.77 | [47] |

| Haloferax mediterranei | Glucose a (1) | 20 | Fed-batch | 85.8 | P(3HB-3HV) [10.7 mol% 3HV] | 48.6 | 41.69 | [48] |

| Halogranum amylolyticum TNN58 | Glucose a (1) | 20 | Fed-batch (7.5 L) | 5.4 | P(3HB-3HV) [20.1 mol% 3HV] | 26.6 | 1.4 | [50] |

| Halogeometricum borinquense E3 | Glucose a (2) | 20 | Shake flask | 2.1 | P(3HB-3HV) [21.47 mol% 3HV] | 73.51 | 1.54 | [51] |

| Natrinema ajinwuensis RM-G10 | Glucose a (1) | 20 | Shake flask (Repeat batch) | 24.2 | P(3HB-3HV) [13.93 mol% 3HV] | 61 | 14.78 | [52] |

| Biowastes | ||||||||

| Starch-based feedstocks | ||||||||

| H. mediterranei | Extruded starch (1) | 23.4 | Shake flask | 39.4 | P(3HB-3HV) [10.4 mol% 3HV] | 50.8 | 20/01 | [53] |

| Extruded rice bran: corn starch::1:8) (1) | 23.4 | Fed-batch | 140 | P(3HB-3HV) [10.4 mol% 3HV] | 55.6 | 77.84 | [54] | |

| Extruded corn starch (1) | 23.4 | Fed-batch | 62.6 | P(3HB-3HV) [10.4 mol% 3HV] | 38.7 | 24.2 | ||

| H. mediterranei CGMCC 1.2087 | Starch (1) + AS-168 medium | 20 | Shake flask | 7.33 | P(3HB-3HV) [9.33 mol% 3HV] | 18.21 | 1.33 | [49] |

| Starch (1) + MST medium | 20 | Shake flask | 7.01 | P(3HB-3HV) [13.37 mol% 3HV] | 24.88 | 1.74 | ||

| Natrinema sp. 1KYS1 | Starch (2) | 25 | Shake flask | 2.21 | P(3HB-3HV) | 2.48 | 0.055 | [46] |

| Corn starch (2) | 25 | Shake flask | 0.17 | P(3HB-3HV) [25 mol% 3HV] | 53.14 | 0.075 | ||

| Dairy and ethanol industry waste | ||||||||

| H. mediterranei DSM 1411 | Hydrolyzed whey | 15.6 | Shake flask | 24 | P(3HB-3HV) [8 mol% 3HV] | 50 | 12 | [55] |

| Hydrolyzed whey sodium valerate and γ-butyrolactone | 15 | Batch | 16.8 | P(3HB-3HV-4HB) [21.8 mol% 3HV; 5.1 mol% 4HB] | 87.5 | 14.7 | [56] | |

| Pre-treated vinasse (25%) | 20 | Shake flask | 28.14 | P(3HB-3HV) [12.36 mol% 3HV] | 70 | 19.7 | [57] | |

| Pre-treated vinasse (50%) | 20 | Shake flask | 26.34 | P(3HB-3HV) [14.09 mol% 3HV] | 66 | 17.4 | ||

| Rice-based ethanol stillage | 20 | Shake flask | 23.12 | P(3HB-3HV) [15.4 mol% 3HV] | 71 | 16.42 | [58] | |

| H. marismortui MTCC 1596 | Raw vinasse (10) | 20 | Shake flask | 12 | P(3HB) | 23 | 2.8 | [59] |

| Raw vinasse (pre-treated—activated carbon) (100) | 20 | Shake flask | 15 | P(3HB) | 30 | 4.5 | ||

| Natrinema sp. 1KYS1 | Whey (2) | 25 | Shake flask | 0.454 | P(3HB-3HV) | 19.92 | 0.091 | [46] |

| Agro-industrial waste and other feedstocks | ||||||||

| Natrinema sp. 1KYS1 | Melon waste (2) | 25 | Shake flask | 0.37 | P(3HB-3HV) | 10.5 | 0.039 | [46] |

| Apple waste (2) | 25 | Shake flask | 2.55 | P(3HB-3HV) | 3.02 | 0.077 | ||

| Tomato waste (2) | 25 | Shake flask | 3.85 | P(3HB-3HV) | 12.03 | 0.46 | ||

| H. mediterranei | Olive mill wastewater (15) | 22 | Shake flask | 10 | P(3HB-3HV) [6.5 mol% 3HV] | 43 | 4.3 | [60] |

| Halogeometricum borinquense E3 | Sugarcane bagasse hydrolysate (20) | 20 | Shake flask | 3.17 | P(3HB-3HV) [13.29 mol% 3HV] | 50.4 | 1.59 | [61] |

| Starch (2) | 20 | Shake flask | 6.2 | P(3HB-3HV) [13.11 mol% 3HV] | 74.19 | 4.6 | [62] | |

| Cassava waste hydrolysate (10) | 20 | Shake flask | 3.4 | P(3HB-3HV) [19.65 mol% 3HV] | 44.7 | 1.52 | ||

| Criteria | Archaea | Bacteria |

|---|---|---|

| Max. PHA Yield (g/L) | 77.8 (Rice bran-corn starch mix) | 10.5 (Optimized crude glycerol) |

| Max. PHA Content (%) | 87.5 | 95.26 |

| Best Feedstocks | Hydrolyzed whey, rice bran-corn starch, ethanol waste | Fructose syrup, sugar beet molasses, crude glycerol |

| Copolymer Composition | 21.8 mol% 3HV, 5.1 mol% 4HB | 52 mol% 3HV, high M.Wt. PHA |

| Waste Valorization | Strong (vinasse, bagasse, agro-waste) | Moderate (biodiesel byproducts, wheat straw) |

| Industrial Feasibility | More established (high yield and adaptability to hypersaline environments) | More cost-effective (low-cost substrates, non-sterile fermentation) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kalia, V.C.; Singh, R.V.; Gong, C.; Lee, J.-K. Toward Sustainable Polyhydroxyalkanoates: A Next-Gen Biotechnology Approach. Polymers 2025, 17, 853. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17070853

Kalia VC, Singh RV, Gong C, Lee J-K. Toward Sustainable Polyhydroxyalkanoates: A Next-Gen Biotechnology Approach. Polymers. 2025; 17(7):853. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17070853

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalia, Vipin Chandra, Rahul Vikram Singh, Chunjie Gong, and Jung-Kul Lee. 2025. "Toward Sustainable Polyhydroxyalkanoates: A Next-Gen Biotechnology Approach" Polymers 17, no. 7: 853. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17070853

APA StyleKalia, V. C., Singh, R. V., Gong, C., & Lee, J.-K. (2025). Toward Sustainable Polyhydroxyalkanoates: A Next-Gen Biotechnology Approach. Polymers, 17(7), 853. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17070853