Extruder Path Analysis in Fused Deposition Modeling Using Thermal Imaging

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Methodology

2.1. Materials and Test Specimen

2.2. FDM Printer and Slicing Parameters

2.3. Thermal Imaging System and Software

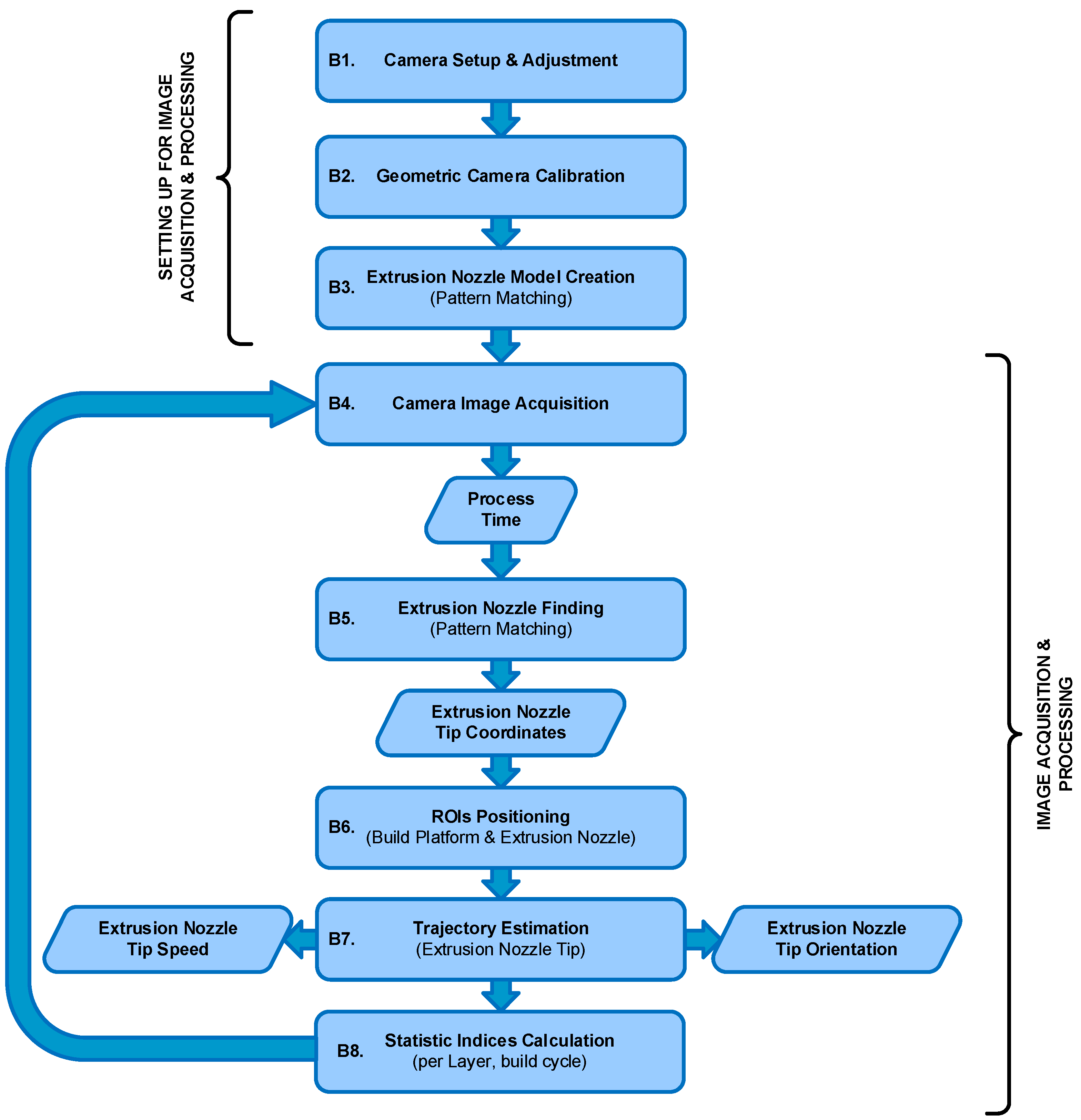

2.4. Data Processing Workflow

2.4.1. The G-Code Processing Workflow

- Group A (Shells): Layers 2, 4, 13, and 15, which share identical perimeter paths and nominal speeds.

- Group B (Infill): Layers 5 through 11, which share identical infill patterns and densities.

- Unique Layers: Layers 1 (first layer), 12, and 16 (bridge) possess unique pathing and were excluded from the repeatability comparison.

2.4.2. Vision-Based Workflow and Camera Calibration

3. Results and Discussion

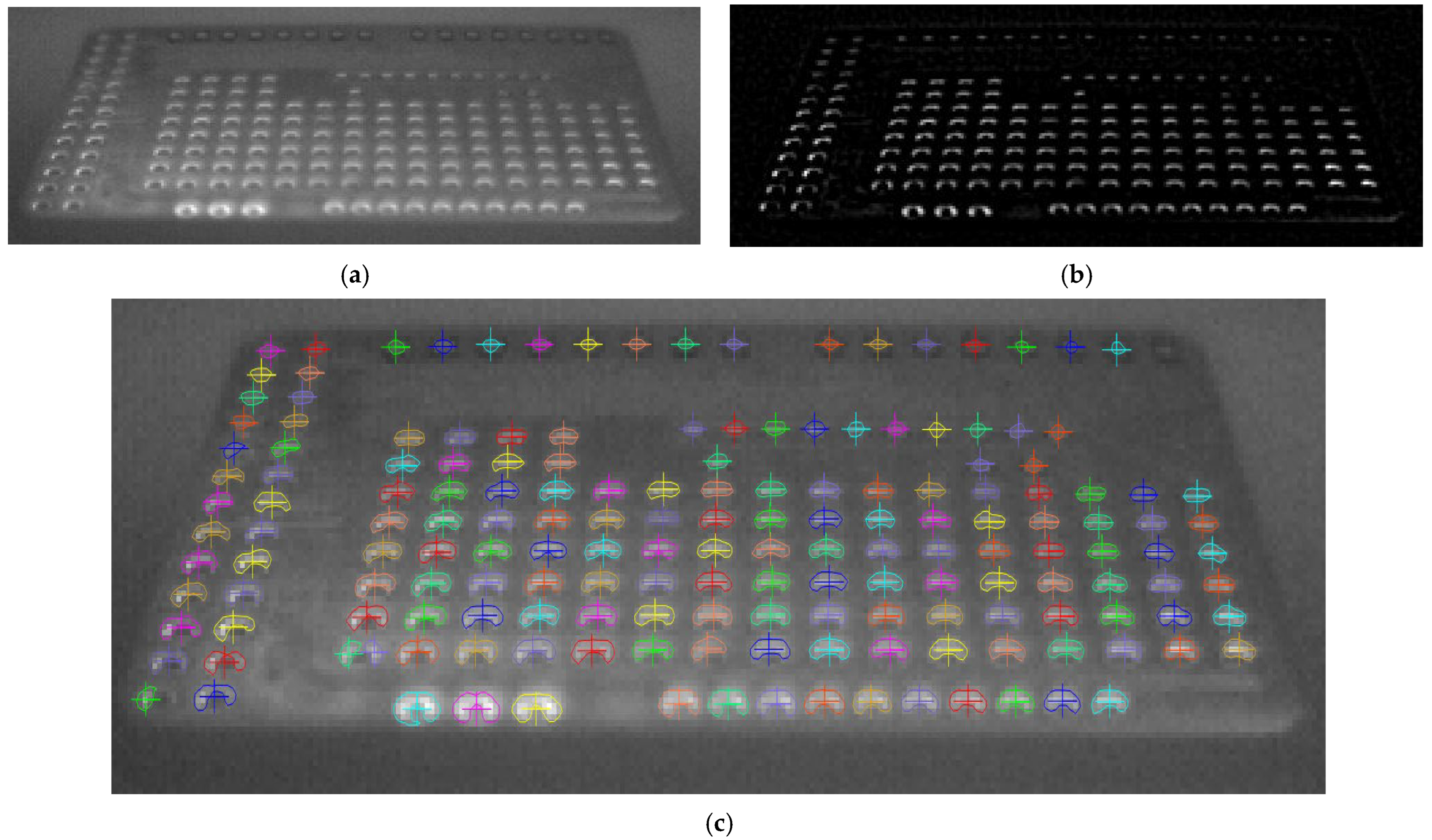

3.1. Validation of the Vision-Based Workflow: Camera Calibration

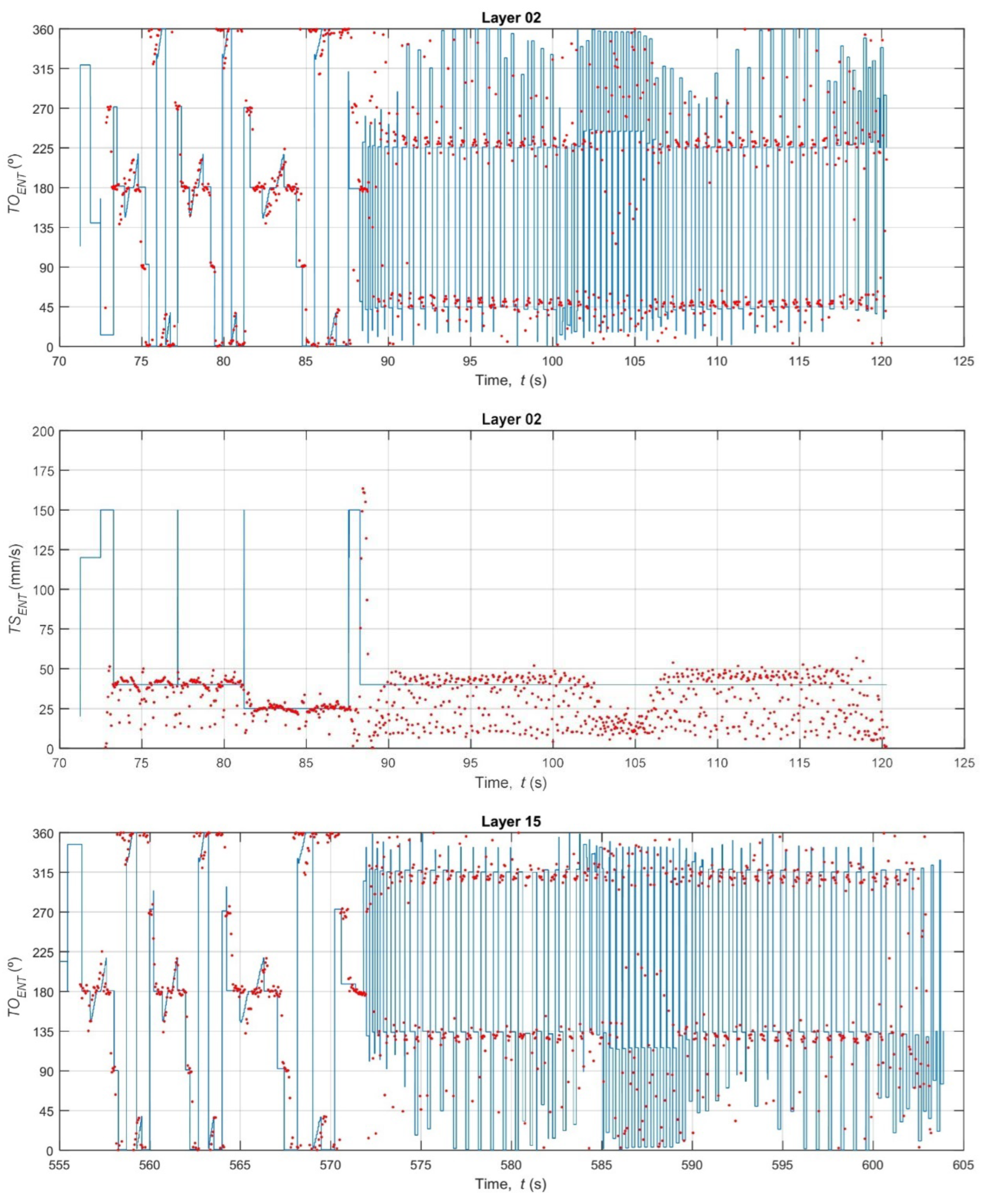

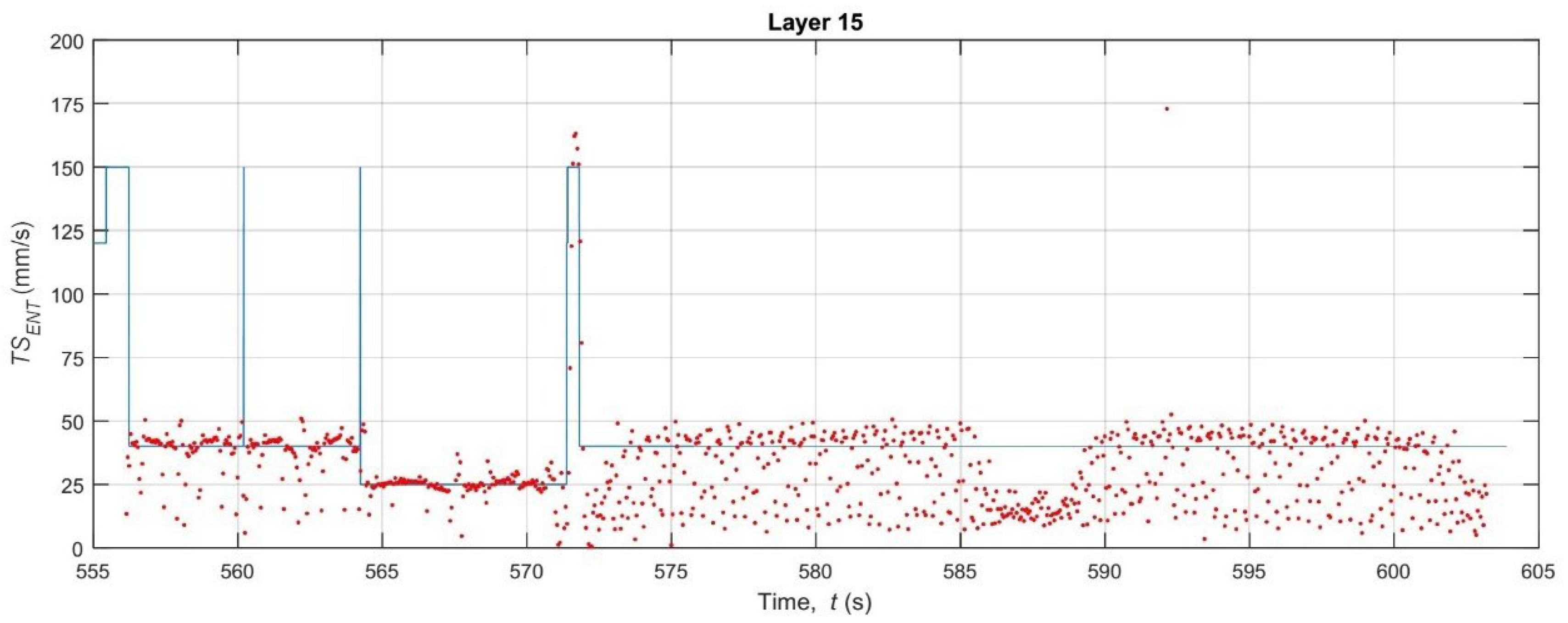

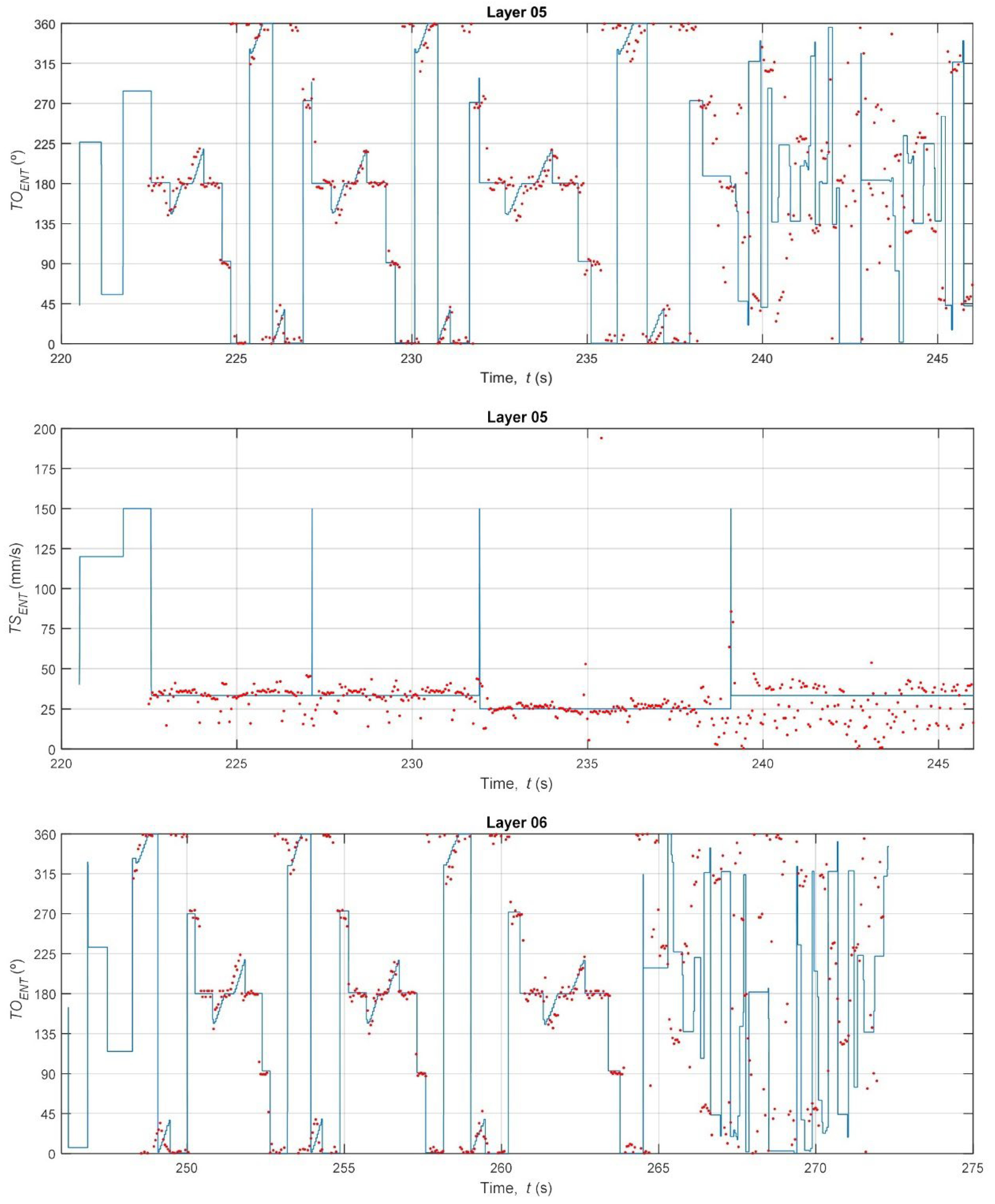

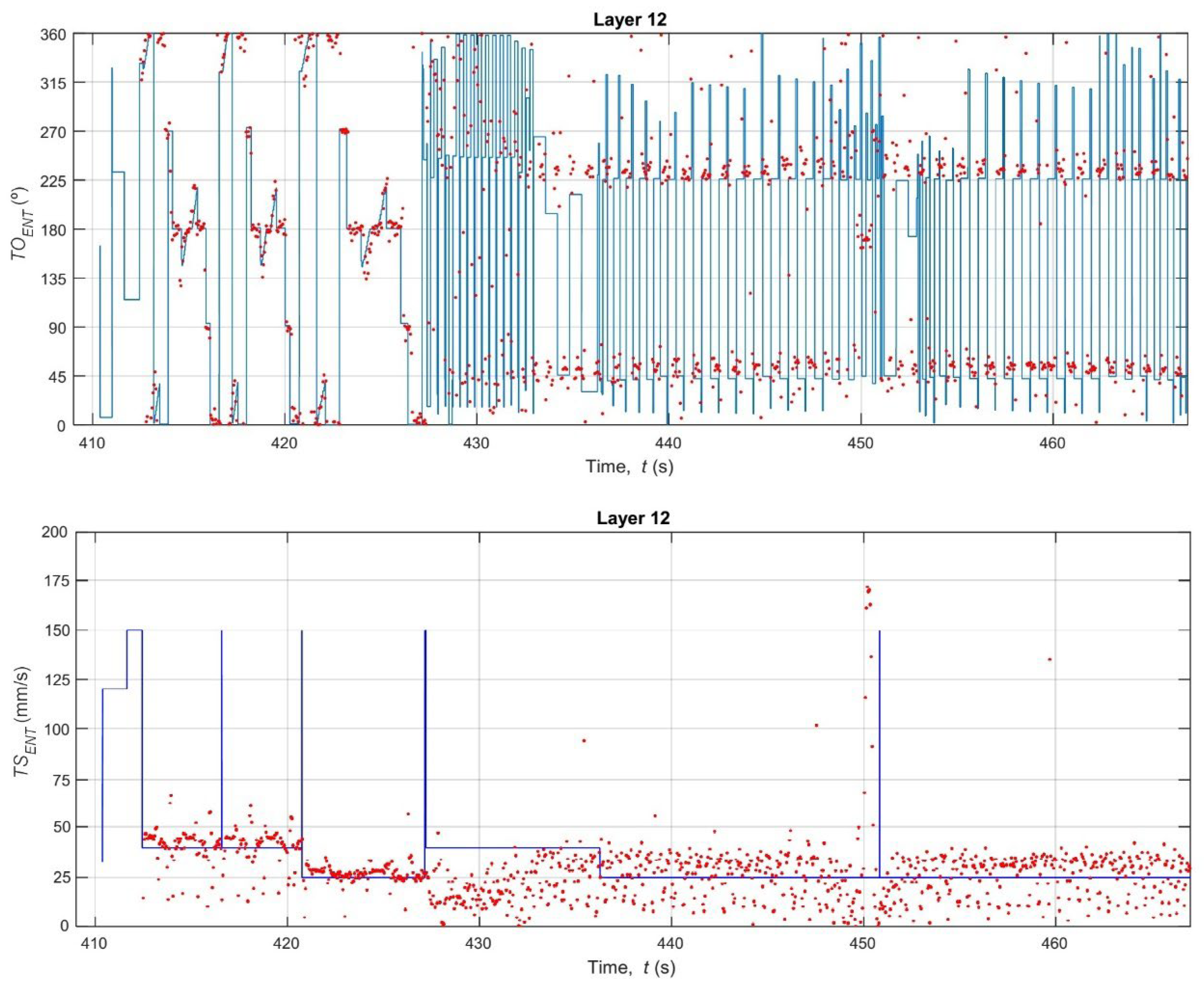

3.2. Analysis of Extruder Kinematic Fidelity: Speed and Orientation

4. Conclusions

- The system is highly sensitive to the toolpath strategy, clearly distinguishing the kinematic error profiles of different layer types. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for speed was significantly lower during the 15% grid infill layers (MAE ≈ 5.5–6.4 mm/s) compared to the solid layers (MAE ≈ 9.4–12.5 mm/s). This discrepancy was found to be driven by the system’s 27 Hz frame rate, which was insufficient to capture the high-speed (150 mm/s) G0 travel moves prevalent in solid layer strategies.

- The orientation error (TOENT) was consistently high across all layers (MAE ≈ 15.3–20.5°). This finding is not a measurement failure but rather the first-time quantification of the physical lag, jerk, and stabilization time the extruder head experiences during rapid directional changes—dynamics that are idealized and ignored by the nominal G-code. This metric serves as a direct measurement of the printer’s mechanical limitations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yadollahi, A.; Shamsaei, N. Additive Manufacturing of Fatigue Resistant Materials: Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Fatigue 2017, 98, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fico, D.; Rizzo, D.; Casciaro, R.; Corcione, C.E. A Review of Polymer-Based Materials for Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF): Focus on Sustainability and Recycled Materials. Polymers 2022, 14, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizon, J.R.C.; Espera, A.H.; Chen, Q.; Advincula, R.C. Mechanical Characterization of 3D-Printed Polymers. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 20, 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yeon-Gil, J. Overview of Additive Manufacturing Process. In Additive Manufacturing: Materilas, Processes, Quantifications and Applications; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 1–38. ISBN 9780128121559. [Google Scholar]

- Tofail, S.A.M.; Koumoulos, E.P.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Bose, S.; O’Donoghue, L.; Charitidis, C. Additive Manufacturing: Scientific and Technological Challenges, Market Uptake and Opportunities. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Rathee, S.; Patel, V.; Kumar, A.; Koppad, P.G. A Review of Various Materials for Additive Manufacturing: Recent Trends and Processing Issues. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 21, 2612–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, J.M.; Caminero, M.A.; García-plaza, E.; Núñez, P.J. Additive Manufacturing of PLA Structures Using Fused Deposition Modelling: Effect of Process Parameters on Mechanical Properties and Their Optimal Selection. Mater. Des. 2017, 124, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshin, N.P.; Grigor’ev, M.V.; Shchipakov, N.A.; Prilutskii, M.A.; Murashov, V.V. Applying Nondestructive Testing to Quality Control of Additive Manufactured Parts. Russ. J. Nondestruct. Test. 2016, 52, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Downey, A.; Yuan, L.; Pratt, A.; Balogun, Y. In Situ Monitoring for Fused Filament Fabrication Process: A Review. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 38, 101749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, K.; Rama Koti Reddy, D.V.; Mulaveesala, R. Application of Image Fusion for the IR Images in Frequency Modulated Thermal Wave Imaging for Non Destructive Testing (NDT). Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpetuini, D.; Formenti, D.; Cardone, D.; Filippini, C.; Merla, A. Regions of Interest Selection and Thermal Imaging Data Analysis in Sports and Exercise Science: A Narrative Review. Physiol. Meas. 2021, 42, 08TR01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, I.; Lucchi, E.; de Rubeis, T.; Ambrosini, D. Quantification of Heat Energy Losses through the Building Envelope: A State-of-the-Art Analysis with Critical and Comprehensive Review on Infrared Thermography. Build. Environ. 2018, 146, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercuri, F.; Buonora, P.; Cicero, C.; Helas, P.; Manzari, F.; Marinelli, M.; Paoloni, S.; Pasqualucci, A.; Pinzari, F.; Romani, M.; et al. Metastructure of Illuminations by Infrared Thermography. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 31, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Periñán, P.J.; Martínez-Ramos, J.L. Influencial Factors in Thermographic Analysis in Substations. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2018, 90, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Saavedra, S.; Hernandez-Callejo, L.; Duque-Perez, O. Image Resolution Influence in Aerial Thermographic Inspections of Photovoltaic Plants. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2018, 14, 5678–5686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Mian, T.; Fatima, S. Convolutional Neural Network Based Bearing Fault Diagnosis of Rotating Machine Using Thermal Images. Measurement 2021, 176, 109196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.; Souto, A.; Gonzalez, C.; Mendez-Rial, R. Embedded Vision System for Monitoring Arc Welding with Thermal Imaging and Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Omni-Layer Intelligent Systems, COINS 2020, Virtual, 31 August–2 September 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.V.C.; Brioschi, M.L.; Dias, F.G.; Parolin, M.B.; Mulinari-Brenner, F.A.; Ordonez, J.C.; Colman, D. Normalized Methodology for Medical Infrared Imaging. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2009, 52, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patino, L.; Hubner, M.; King, R.; Litzenberger, M.; Roupioz, L.; Michon, K.; Szklarski, Ł.; Pegoraro, J.; Stoianov, N.; Ferryman, J. Fusion of Heterogenous Sensor Data in Border Surveillance. Sensors 2022, 22, 7351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quttineh, N.H.; Olsson, P.M.; Larsson, T.; Lindell, H. An Optimization Approach to the Design of Outdoor Thermal Fire Detection Systems. Fire Saf. J. 2022, 129, 103548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagoz, A.S.; Hasirci, V. 3D Printing of Polymeric Tissue Engineering Scaffolds Using Open-Source Fused Deposition Modeling. Emergent Mater. 2020, 3, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caltanissetta, F.; Dreifus, G.; Hart, A.J.; Colosimo, B.M. In-Situ Monitoring of Material Extrusion Processes via Thermal Videoimaging with Application to Big Area Additive Manufacturing (BAAM). Addit. Manuf. 2022, 58, 102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbouelNour, Y.; Gupta, N. Assisted Defect Detection by In-Process Monitoring of Additive Manufacturing Using Optical Imaging and Infrared Thermography. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 67, 103483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yu, Z.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Kong, Q.; Tang, J. Real-Time Monitoring of Raster Temperature Distribution and Width Anomalies in Fused Filament Fabrication Process. Adv. Manuf. 2022, 10, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H. Fault Diagnosis of FDM Process Based on Support Vector Machine (SVM). Rapid Prototyp. J. 2020, 26, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, R.E.N.; Lewis, J.; Moore, A.L. In Situ Infrared Temperature Sensing for Real-Time Defect Detection in Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 47, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, L.; Rackl, S.; Scholz, M.; Hartmann, M. Linking Thermal Images with 3D Models for FFF Printing. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 217, 1168–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppala, J.E.; Davis, C.S.; Migler, K.B. Weld Formation during Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing. Soft Matter 2017, 13, 6761–6769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malekipour, E.; Attoye, S.; El-Mounayri, H. Investigation of Layer Based Thermal Behavior in Fused Deposition Modeling Process by Infrared Thermography. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 26, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraris, E.; Zhang, J.; Van Hooreweder, B. Thermography Based In-Process Monitoring of Fused Filament Fabrication of Polymeric Parts. CIRP Ann. 2019, 68, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Meng, F.; Ferraris, E. Temperature Gradient at the Nozzle Outlet in Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing with Thermoplastic Filament. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 73, 103660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, Y.; Liu, S.; Duan, M. In-Situ Additive Manufacturing Deposition Trajectory Monitoring and Compensation with Thermal Camera. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 78, 103820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D638-14; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics 2014. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- Optris IRImagerDirect SDK. Available online: https://sdk.optris.com/libirimager2/html/index.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Halcon MVtec Software. Available online: https://www.mvtec.com/products/halcon (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Badarinath, R.; Prabhu, V. Real-Time Sensing of Output Polymer Flow Temperature and Volumetric Flowrate in Fused Filament Fabrication Process. Materials 2022, 15, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swamidoss, I.N.; Bin Amro, A.; Sayadi, S. Systematic Approach for Thermal Imaging Camera Calibration for Machine Vision Applications. Optik 2021, 247, 168039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheikh, A.; Abu-nabah, B.A.; Hamdan, M.O. Infrared Camera Geometric Calibration: A Review and a Precise Thermal Radiation Checkerboard Target. Sensors 2023, 23, 3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgibbon, A.W. Simultaneous Linear Estimation of Multiple View Geometry and Lens Distortion. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Kauai, HI, USA, 8–14 December 2001; Volume 1, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. A Flexible New Technique for Camera Calibration. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2000, 22, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, M.G.; Kong, S.G. Focusing in Thermal Imagery Using Morphological Gradient Operator. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2014, 38, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelonas, M.A.; Veinidis, C.N.; Bartsokas, T.K. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition for the Analysis of 2D/3D Remote Sensing Data in Geoscience: A Survey. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Jiang, X.; Fan, A.; Jiang, J.; Yan, J. Image Matching from Handcrafted to Deep Features: A Survey. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 23–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahne, B.; Haußecker, H.; Geißler, P. Handbook of Computer Vision and Applications. Volume 2. Signal Processing and Pattern Recognition; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999; Volume 2, ISBN 0123797705. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, R.C.; Woods, R.E. Digital Image Processing, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | Description | Value (mm) | Tolerance (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| W | Width of narrow section | 3.18 | ±0.5 |

| L | Length of narrow section | 9.53 | ±0.5 |

| WO | Width overall, min | 9.53 | ±3.18 |

| LO | Length overall, min | 63.5 | no max |

| G | Gage length | 7.62 | ±0.25 |

| D | Distance between grips | 25.4 | ±5 |

| R | Radius of fillet | 12.7 | ±1 |

| T | Thickness | 3.2 | ±0.4 |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nozzle diameter | 0.4 mm | Nozzle temperature | 212 °C |

| Extrusion width | 0.4 mm | Bed temperature | 55 °C |

| Layer height | 0.2 mm | Infill density | 15% |

| Total layers | 16 | Grid pattern infill layers | 7 |

| Solid bottom layers | 4 | Solid top layers | 4 |

| Bottom/top infill rater angle | ±45° | Bottom/top infill pattern | monotonic |

| Bridging layers | 1 | Bridging infill pattern | monotonic |

| Bridging infill raster angle | 45° | Infill speed (Grid) | ≈32 mm/s |

| Perimeter (per layer) | 2 turns | External perimeter (per layer) | 1 turn |

| Layer | N | (s) | (°) | (mm/s) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | |||||||

| 1 | 1413 | 0.0 | 72.0 | 18.0 | 22.5 | 11.3 | 15.2 | |||

| 2 | 951 | 72.1 | 47.9 | 19.7 | 23.4 | 11.6 | 16.0 | |||

| 3 | 945 | 120.1 | 50.1 | 18.2 | 22.0 | 11.2 | 15.6 | |||

| 4 | 950 | 170.2 | 49.3 | 20.1 | 23.5 | 11.7 | 16.8 | |||

| 5 | 588 | 219.5 | 26.6 | 17.4 | 21.5 | 5.8 | 8.8 | |||

| 6 | 478 | 246.2 | 26.3 | 16.0 | 20.0 | 5.5 | 8.2 | |||

| 7 | 483 | 272.5 | 25.2 | 15.3 | 19.4 | 5.8 | 8.7 | |||

| 8 | 480 | 297.7 | 25.8 | 16.3 | 20.7 | 5.7 | 8.0 | |||

| 9 | 482 | 323.5 | 25.6 | 15.8 | 20.2 | 6.0 | 8.7 | |||

| 10 | 443 | 349.1 | 25.7 | 15.5 | 19.7 | 5.5 | 7.8 | |||

| 11 | 438 | 374.8 | 26.3 | 17.1 | 21.3 | 6.4 | 9.1 | |||

| 12 | 1129 | 401.1 | 59.0 | 18.6 | 22.4 | 9.4 | 12.3 | |||

| 13 | 940 | 460.1 | 47.0 | 20.5 | 24.3 | 12.5 | 15.6 | |||

| 14 | 954 | 507.1 | 48.7 | 19.0 | 22.6 | 12.2 | 16.3 | |||

| 15 | 942 | 555.8 | 48.3 | 18.8 | 22.7 | 11.1 | 15.4 | |||

| 16 | 953 | 604.1 | 48.8 | 19.2 | 22.73 | 10.8 | 13.2 | |||

| Layer Group | Layer Type | (°) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | ||||||||

| Avg | Std | Avg | Std | Avg | Std | Avg | Std | ||||

| I | Top/Bottom (−45°) | 19.8 | 0.73 | 23.5 | 0.66 | 11.7 | 0.58 | 16.0 | 0.62 | ||

| II | Top/Bottom (+45°) | 18.6 | 0.57 | 23.1 | 0.64 | 12.0 | 0.35 | 16.6 | 0.35 | ||

| III | Infill (grid pattern) | 16.2 | 0.79 | 20.4 | 0.80 | 5.8 | 0.31 | 8.5 | 0.48 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cañero-Nieto, J.M.; Campo-Campo, R.J.; Díaz-Bolaño, I.B.; Solano-Martos, J.F.; Vergara, D.; Ariza-Echeverri, E.A.; Deluque-Toro, C.E. Extruder Path Analysis in Fused Deposition Modeling Using Thermal Imaging. Polymers 2025, 17, 3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243310

Cañero-Nieto JM, Campo-Campo RJ, Díaz-Bolaño IB, Solano-Martos JF, Vergara D, Ariza-Echeverri EA, Deluque-Toro CE. Extruder Path Analysis in Fused Deposition Modeling Using Thermal Imaging. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243310

Chicago/Turabian StyleCañero-Nieto, Juan M., Rafael J. Campo-Campo, Idanis B. Díaz-Bolaño, José F. Solano-Martos, Diego Vergara, Edwan A. Ariza-Echeverri, and Crispulo E. Deluque-Toro. 2025. "Extruder Path Analysis in Fused Deposition Modeling Using Thermal Imaging" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243310

APA StyleCañero-Nieto, J. M., Campo-Campo, R. J., Díaz-Bolaño, I. B., Solano-Martos, J. F., Vergara, D., Ariza-Echeverri, E. A., & Deluque-Toro, C. E. (2025). Extruder Path Analysis in Fused Deposition Modeling Using Thermal Imaging. Polymers, 17(24), 3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243310