1. Introduction

Cellular behavior is dynamically regulated through the integration of biochemical and biophysical signals originating from the surrounding microenvironment, which includes both the extracellular matrix (ECM) and neighboring cells [

1]. Beyond metabolic and humoral factors—which are outside the scope of this study—cells possess specialized mechanosensitive receptors that detect and transduce mechanical cues into intracellular signaling cascades, ultimately leading to phenotypic adaptations. This process, termed

mechanotransduction, is fundamental to a wide array of physiological and pathological processes, including embryogenesis, tissue homeostasis, aging, wound healing, and tumorigenesis [

2,

3,

4].

Among the cell types most responsive to mechanical stimuli are mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), whose fate decisions and regenerative capacity are tightly governed by mechanotransductive signaling [

2,

5]. Central to this mechanosensory machinery are integrins—transmembrane receptors that mediate cell–ECM adhesion and simultaneously sense matrix stiffness, topography, and other mechanical properties. These interactions orchestrate cytoskeletal remodeling and drive morphological and functional changes [

6,

7]. In addition to integrins, other adhesive receptors, such as members of the immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF), may also modulate MSC behavior and contribute to their mechanosensitivity [

8,

9,

10].

Collagen, the predominant structural protein within the ECM, plays a critical role in defining the matrix’s mechanical landscape, including its stiffness, porosity, and surface architecture [

11]. These biomechanical attributes facilitate force transmission and regulate intercellular communication, thereby influencing diverse cellular functions [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Despite significant advances in ECM biology, the mechanistic implications of collagen-cell interactions—particularly under pathological conditions—remain incompletely elucidated [

16,

17].

One such pathological alteration is collagen glycation, a non-enzymatic modification driven by sustained hyperglycemia. This process involves the covalent attachment of reducing sugars to free amino groups in collagen, initiating the Maillard reaction and leading to the formation of early Amadori products [

16]. Over time, these products evolve into advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which disrupt collagen’s supramolecular organization and alter its biomechanical properties [

15,

17]. In chronic diabetic conditions, excessive glycation compromises ECM integrity and perturbs mechanotransduction pathways, potentially impairing stem cell-mediated tissue regeneration and remodeling [

18].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) possess the capacity to detect and respond to extracellular collagen through multiple mechanisms, with integrins playing a central role in mediating physical anchorage to the ECM and directing lineage specification and functional behavior [

19,

20]. These cell–matrix interactions are predominantly orchestrated through focal adhesions (FAs)—dynamic multiprotein complexes that serve as key mechanotransductive nodes, bridging ECM components, integrin receptors, and the intracellular cytoskeleton [

21]. FA formation is particularly efficient on two-dimensional (2D) substrates, where biophysical parameters such as stiffness, surface topography, and surface energy critically influence their maturation and stability [

11,

21]. Moreover, the nanoscale spatial distribution of adsorbed adhesive proteins significantly modulates FA architecture and longevity [

21,

22]. Among the integrin heterodimers implicated in collagen recognition are α1β1, α2β1, and α6β1, which facilitate cellular adhesion and initiate downstream mechanotransductive signaling. Mechanical forces transmitted through integrins induce cytoskeletal remodeling and activate intracellular signaling cascades, notably the RhoA pathway. This involves the regulation of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs), which modulate actomyosin contractility and cellular tension [

23]. The dynamic reciprocity between collagen-integrin engagement and cytoskeletal signaling is essential for maintaining cellular morphology, polarity, and functional integration within the ECM. Through extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and other pathways, integrin signaling affects genes involved in cell cycle progression, differentiation, and migration. Thus, mechanical signals from integrins can influence chromatin accessibility and histone modifications, linking ECM stiffness to transcriptional programs [

24].

Recent insights have highlighted the Hippo signaling pathway as another critical downstream effector of mechanical stimuli, acting as a conduit for transducing extracellular mechanical cues into nuclear transcriptional responses [

25,

26,

27]. This evolutionarily conserved pathway, originally characterized in

Drosophila melanogaster, governs key biological processes including cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, and organ size regulation [

28]. The Hippo pathway operates through a hierarchical kinase cascade involving the serine/threonine kinases STK3 (MST2) and STK4 (MST1), which form a complex with the scaffold protein Salvador (SAV1). This complex phosphorylates and activates the Large Tumor Suppressor Kinases (LATS1 and LATS2), which subsequently inhibit the transcriptional coactivators Yes-associated protein (YAP1) and transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) by promoting their cytoplasmic retention and degradation [

26,

29]. Through this mechanism, the Hippo pathway integrates mechanical inputs to regulate gene expression programs essential for tissue homeostasis and regenerative potential.

In our recent investigations, we provided both morphological and quantitative morphometric evidence of altered mechanotransductive signaling in adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) adhering to collagen under oxidative stress conditions. These alterations implicated focal adhesions, actin cytoskeletal organization, and YAP/TAZ activity as key mechanistic components [

15]. Furthermore, we demonstrated that early-stage glycation of collagen induces significant structural and biomechanical modifications, affecting FA assembly, integrin clustering, cytoskeletal dynamics, and the remodeling of the collagen matrix [

15,

17], as well as the kinetics of cellular attachment [

10].

Building upon these findings, the present study aims to elucidate how post-translational modifications of collagen—specifically glycation—impact mechanotransduction in MSCs. Given the central role of ECM mechanics in stem cell fate determination, understanding these interactions is critical for advancing regenerative strategies under pathological conditions such as diabetes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collagen Procedures

2.1.1. Collagen Preparation

As previously mentioned, rat tail tendon was extracted using acetic acid and then salted off with NaCl to produce almost pure collagen type I [

30]. After centrifuging for 30 min at 4000 rpm and 4 °C, the pellets were redissolved in 0.05 M acetic acid and dialyzed versus 0.05 M acetic acid to get rid of the extra NaCl. As a result, a roughly monomolecular composition of rat tail collagen (RTC) solution was made, where the collagen concentration was close to 100% of the dry mass. Collagen isolation procedures were carried out at 4 °C. The modified Lowry test [

31] and optical absorbance at 220–230 nm were used to determine the collagen concentration in the solutions [

32].

2.1.2. Preparation of Glycated Collagen

Rat tail tendon collagen type I (2 mg/mL) was pre-glycated by incubation in 500 mM glucose (Merck, Rahway, NJ, USA) in PBS at pH 7.4 with 0.02% NaN3 for one day and five days at 37 °C, as previously reported [

18]. After dialysis against 0.05 M acetic acid, the samples were labeled RTC GL1 and RTC GL5, respectively, and stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C until needed.

2.2. Cells

Tissue Bank BulGen (Sofia, Bulgaria) provided human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSC) of passage two. The cells were obtained by liposuction with the prior written consent of regular donors. The cells were kept in DMEM/F12 media that was supplied by Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and included 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% GlutaMAXTM, and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution. The cells were employed in the tests up until the seventh passage, and the media was changed every two days until the cells attained approximately 90% confluency. Trypan blue exclusion testing was used to confirm ADMSC viability at the time of collection for each experiment. For every experiment, more than 85% vitality was considered acceptable.

2.2.1. Morphological Studies

Regular glass coverslips (12 × 12 mm, ISOLAB Laborgeräte GmbH, Eschau, Germany) were coated with collagen (100 μg/mL) in 0.05 M acetic acid for the morphological observations. The coverslips were then put on 6-well TC plates (Sensoplate, Greiner Bioone, Meckenheim, Germany) and incubated for 60 min at 37 °C. Following three PBS washes, the cells were seeded in a final volume of 3 mL serum-free media at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well and incubated for 30 min, 2 h, and 5 h. For all morphological studies at the 2nd hour, 10% FBS was added. Using an inverted microscope (Leica Thunder Imager Live Cell, Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) and phase contrast at magnification 20×, the initial cell adhesion and morphology were examined during the aforesaid time frame. The cells were then incubated before being prepared for immunofluorescent staining and morphometric analysis in two protocols, as follows:

Second Protocol (YAP/TAZ Signaling Events)

Separate samples from the same series were stained with a rabbit polyclonal anti-TAZ antibody and red fluorescent Alexa FluorTM 555 goat anti-rabbit antibody (both supplied by Sigma-Aldrich) in dilution 1:100 to track the YAP/TAZ signaling events. The samples were then counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (to view nuclei) and green fluorescent Phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany). Ultimately, all samples were placed upside down on glass slides using Mowiol and examined using a 20× objective on a Leica Thunder Imager Live Cell.

The CellProfiler 3.0 software was utilized to quantify the overall cell shape [

33,

34]. For every sample, at least three representative images were acquired. The various colors were combined with the corresponding image processing program. Every experiment was conducted four times. The distribution of a YAP/TAZ dataset was shown using box-and-whisker plots.

Quantification of Intracellular Collagen Content

ADMSCs (5 × 104) were seeded on collagen coated 22 × 22 mm coverslips in 6-well tissue culture plates and cultured serum free for 30 min and 2 h; 10% FBS was added for cultures maintained up to 5 h to preserve cell functionality.

For collagen detection, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized using 0.5% Triton X-100. Non-specific binding sites were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Samples were then incubated with a mouse monoclonal anti-human collagen type I antibody (Sigma Aldrich, 1:200 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by a green-fluorescent Alexa Fluor™ 488-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Branchburg, NJ, USA). Nuclear counterstaining was performed using Hoechst 33342 (1:200 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich/Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Fluorescence imaging was conducted using an inverted fluorescence microscope, Leica Thunder Imager, as above, and collagen expression was quantified with ImageJ software. Box-and-whisker plots were used to represent the dataset’s distribution of endogenous human collagen. Box-and-whisker plots were used to display a YAP/TAZ dataset’s distribution.

2.3. Atomic Force Microscopy of Glycated Collagen

2.3.1. Sample Preparation

For Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) imaging, a solution from native or glycated collagens (GL1 and GL5) was deposited onto freshly cleaved, square mica sheets (Structure Probe Inc./SPI Supplies, West Chester, PA, USA) that were adhered to metal pads. Approximately 100 µL of the collagen solution was applied to the mica support. After a 15 min incubation, the samples were washed with water, PBS, and water, thoroughly dried under a stream of nitrogen gas, and then transferred for AFM imaging.

2.3.2. AFM Imaging

AFM imaging was performed using a NanoScope V system (Bruker Inc., Santa Barbara, CA, USA) in tapping mode under ambient air conditions. Standard silicon nitride (Si3N4) probe tips (BudgetSensors; Innovative Solutions Ltd., Sofia, Bulgaria) with a tip radius of less than 10 nm were used. Samples were scanned at a rate of 1 Hz. Each sample was examined at 3 to 5 randomly selected locations across the mica surface. Images (512 × 512 pixels) were acquired in both height and phase modes.

2.3.3. Morphological Characterization

Morphological characterization, including the determination of height, spreading area, and average roughness of the films containing the collagen fibrils, was performed using Bruker NanoScope Analysis 1.3 software. Roughness analysis was conducted as described elsewhere [

36].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in a minimum of three independent series for each group. Because the morphometric parameters did not follow a normal distribution (as verified by Levene’s test), comparisons between subgroups of cells adhering to native and glycated collagen were carried out using a rank-based one-way ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test), which is more suitable for this data type.

Differences among subgroups in NAT (RTC), GL1, and GL5 collagens were further analyzed using Dunn’s post hoc test.

Box-and-whisker plots, a visual tool that displays a dataset’s distribution using its five-number summary: minimum, first quartile (Q1), median (Q2), third quartile (Q3), and maximum, were used for a dataset of YAP TAZ and endogenous human collagen presentation. Significance is indicated by asterisks (*), corresponding to p < 0.05, or (**) corresponding to p < 0.01. visual tool that displays a dataset’s distribution using its five-number summary: minimum, first quartile (Q1), median (Q2), third quartile (Q3), and maximum.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Response of Stem Cells on Glycated Collagen

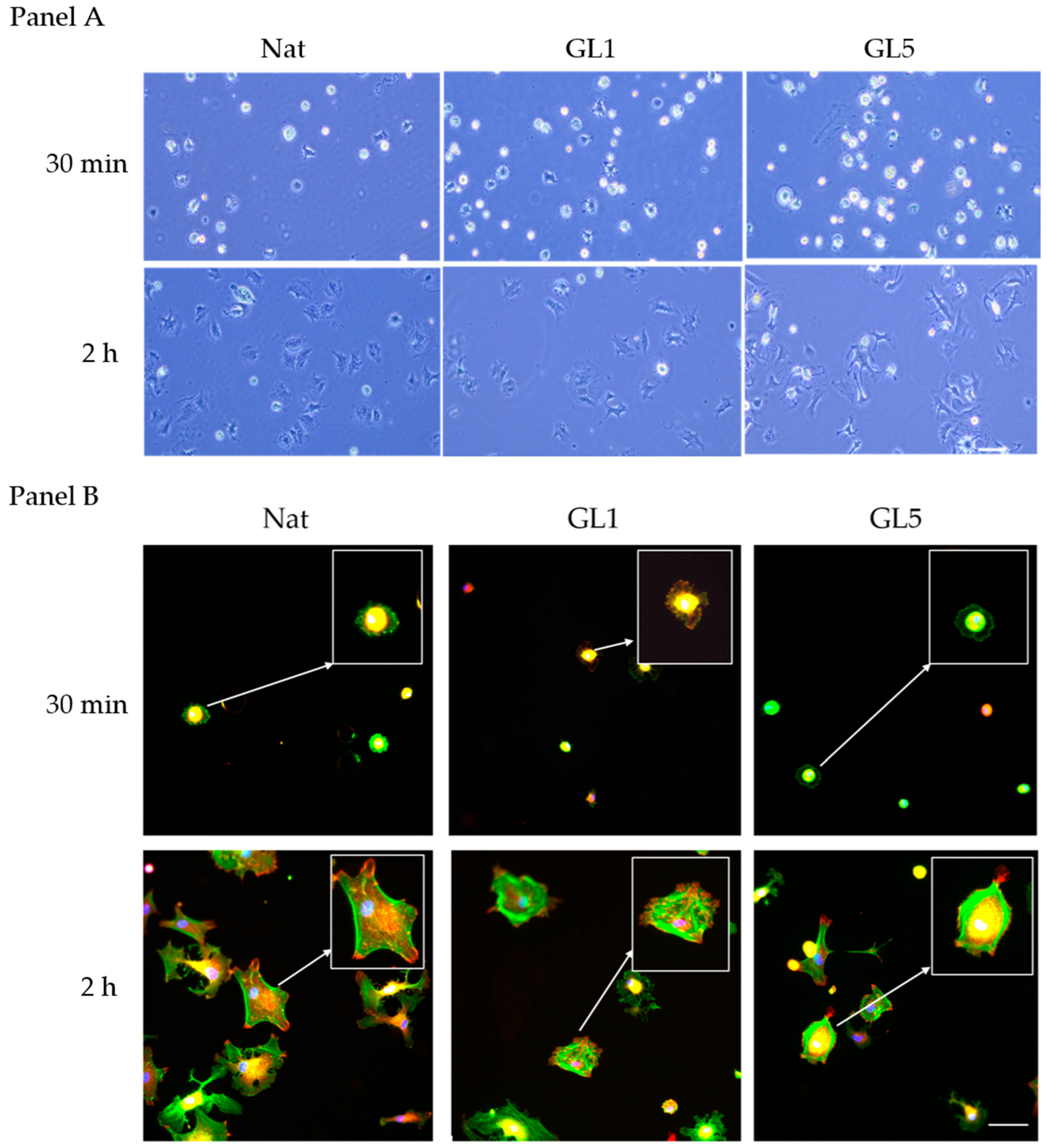

As demonstrated by phase contrast images of living cells captured directly from the plate (

Figure 1 Panel A), under static culture conditions, AD-MSCs exhibit efficient initial adhesion at 30 min (left row) and further spread well at the 2nd hour mark. The initial adhesion however significantly increases on glycated collagen samples, both Gl1 and Gl5, while tend to be reduced at the 2nd hour mark, an effect that was well documented previously [

1,

10,

15,

17], and now validated by our current findings. As shown in

Figure 1 Panel B (bottom row), within two hours post-seeding, AD-MSCs exhibit a robust organization of the actin cytoskeleton, characterized by extensive formation of stress fibers (

Figure 1 Panel B (Nat, 2 h, viewed in green), which coincide with focal adhesion (FA) complexes (red), better seen on the augmented 2× insert, and also below. In contrast, collagen glycation markedly impairs cellular spreading activity. Notably, substrates subjected to five days of glycation (GL5) induce significant cellular shrinkage (

Figure 1, Panel B, GL5 for 2 h), suggesting an altered substratum interaction, whereas those glycated for one day (GL1) promote an intermediate morphological phenotype (

Figure 1, Panel B, GL1 for 2 h). These observations are consistent with our earlier study, supporting a hypothesis of altered integrin-mediated recognition of glycated collagen [

10,

15,

17].

An inverse trend was observed when ADMSC adhesive interactions were assessed at the early 30 min incubation stage (

Figure 1, Panel B, upper row). At this time point, cells exhibited visibly enhanced attachment to glycated collagen substrates (

Figure 1 Panel B upper row) compared to native collagen (

Figure 1, Panel B, first left image).

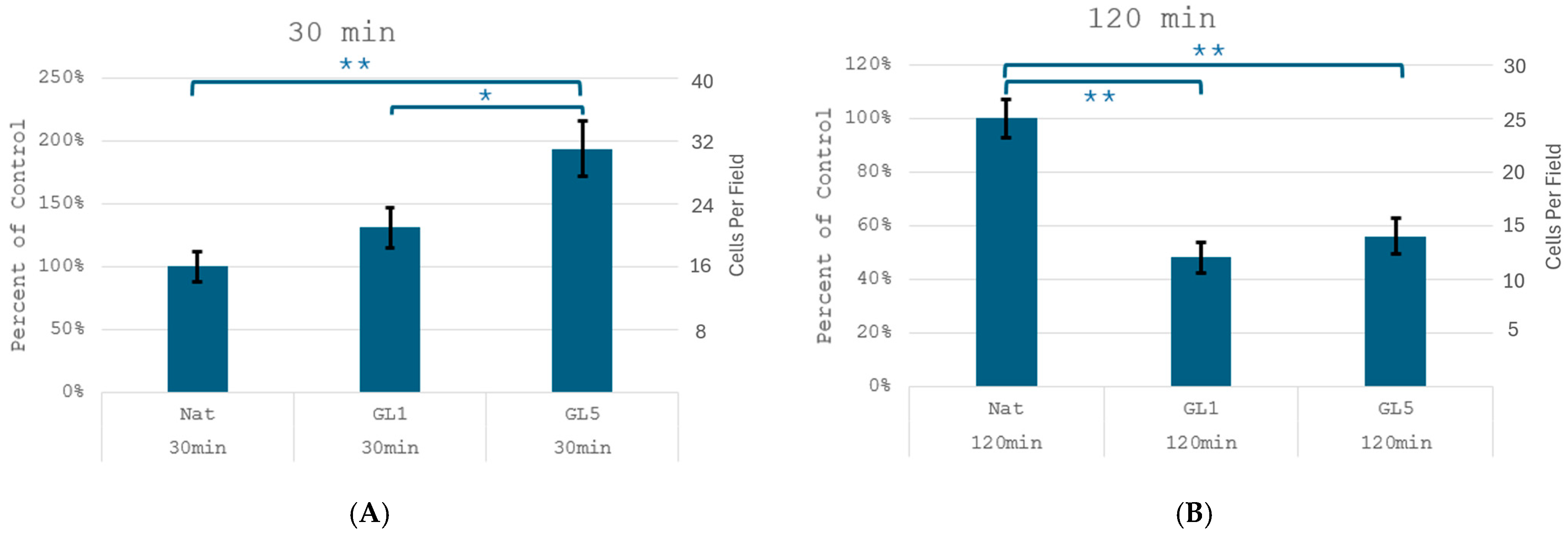

These morphological observations corroborate the direct quantities of cell adhesion (

Figure 2), which revealed a significant increase in the number of adherent cells at the 30 min mark on glycated samples—from 15 ± 2 cells/field on native collagen (Nat) it increases to 21 ± 3 and 32 ± 4 cells/field on GL 1 and GL 5, respectively. For clarity these results are also presented as % increase vs. control (left axis), showing about 140 and 190% increase for Gl1 and Gl5, respectively. Conversely, at 2nd hour mark adhesion significantly drops on glycated samples in about 45 and 48% for Gl1 and Gly5 samples, respectively, from about 25 ± 3 cells/slide to about 12 ± 1 and 14 ± 2 cells/slide, for GL 1 and GL 5, respectively. These quantities are in harmony with the morphological observation in

Figure 1 at panels A and B.

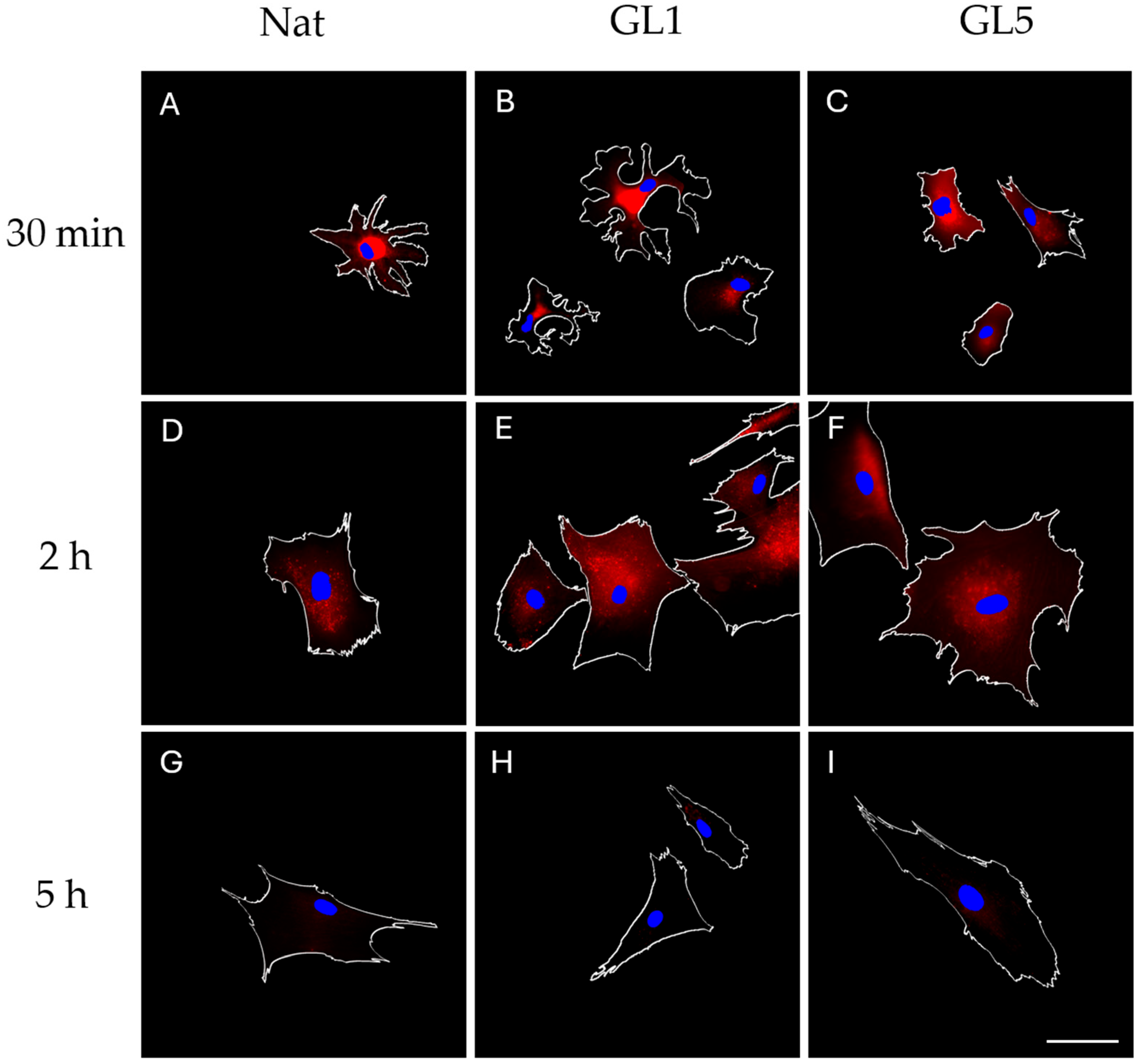

To address potential variability in morphological characteristics across distinct microscopic fields, ImageJ software 1.54g version (Windows, Mac, Linux) was employed in a follow-up experiment to quantitatively assess cell adhesion efficiency. Parameters analysed included mean cell spreading area (CSA, μm

2), perimeter (μm), and cell shape index (CSI) of the cells presented in

Figure 3. This experiment also incorporated an extended incubation period of 5 h. The resulting data are summarised in

Table 1.

As shown in

Table 1—and despite the apparently improved attachment observed in

Figure 2—ADMSCs exhibit reduced adhesion efficiency to glycated collagen substrates during the initial 30 min of incubation. This is most evident in the cell spreading area (CSA), which decreases by approximately 58%, from 3165 μm

2 on native collagen (Nat) to 1337 μm

2 and 1326 μm

2 on GL1 and GL5 substrates, respectively. A similar reduction is observed in cell perimeter, which declines by roughly 45%, from 225 μm on Nat to 144 μm and 136 μm on GL1 and GL5, respectively. Prolonged incubation for 5 h results in only a modest increase in perimeter (~20%), indicating limited enhancement of cell spreading over time. The cell shape index (CSI) however decreases progressively from 0.7 to 0.2 between 30 min and 5 h, reflecting a morphological transition from rounded to more elongated cell profiles. These findings suggest that although initial adhesion to glycated collagen appears accelerated (as illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), it is characterized by restricted spreading and morphological adaptation, indicative of a rapid yet suboptimal adhesion process.

By 2 h of incubation, ADMSCs cultured on native collagen exhibit a pronounced enhancement in adhesion efficiency, reflected by an approximate twofold increase in both cell spreading area (CSA) and perimeter—from 3165 μm2 to 7522 μm2, and from 225 μm to 468 μm, respectively. In contrast, glycated collagen substrates continue to suppress these parameters by roughly 20%. At the 5-h mark, cells begin to partially restore their spreading capacity, as indicated by a modest increase in perimeter and a ~20% decrease in cell shape index (CSI), consistent with a shift toward a more elongated, adherent morphology.

This temporal pattern is consistent with our recent findings [

10], demonstrating that ADMSCs rapidly adhere to glycated collagen substrates under both static and flow-based conditions, followed by a gradual decline in adhesion strength and cell spreading at later time points. These observations prompted the hypothesis that additional adhesive receptors may be involved in mediating early interactions with glycated matrices. As previously proposed [

10], particular attention was given to the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF)—a broad class of cell surface and soluble proteins implicated in cellular recognition, binding, and adhesion processes [

37,

38].

Although our earlier experiments did not reveal substantial RAGE expression in ADMSCs, literature reports suggest that RAGE may be transiently expressed under specific conditions, including exposure to extrinsic microenvironmental cues and prolonged in vitro culture [

39,

40,

41]. To address this, the present study undertook a more systematic morphological investigation of RAGE expression dynamics over extended incubation periods.

3.2. RAGE Expression in ADMSCs During Collagen Adhesion

RAGE expression was evaluated at 30 min, 2 h, and 5 h after ADMSC adhesion to collagen substrates. Up to 2 h, experiments were conducted under serum-free conditions to ensure specific collagen adhesion (integrin clusters already formed), after which 10% serum was added to maintain cell functionality.

Representative images in

Figure 3A–F reveal relatively low levels of RAGE expression, primarily detectable during the early incubation intervals—namely at 30 min and 2 h. Notably, no discrete adhesive clusters were observed at the cell periphery. Instead, RAGE localization appeared diffusely distributed, concentrated rather in the cells middle, but not in the nucleus, suggesting potential association with intracellular compartments or extracellular deposition zones, such as the underlying substratum. By the 5 h time point, RAGE expression showed a pronounced reduction.

3.3. ADMSC Mechanotransduction from Glycated Collagen

Cell–matrix interactions are predominantly mediated by focal adhesions (FAs), which—as outlined in the introduction paragraph—serve as central hubs for mechanotransduction by linking ECM components to integrins and the actin cytoskeleton [

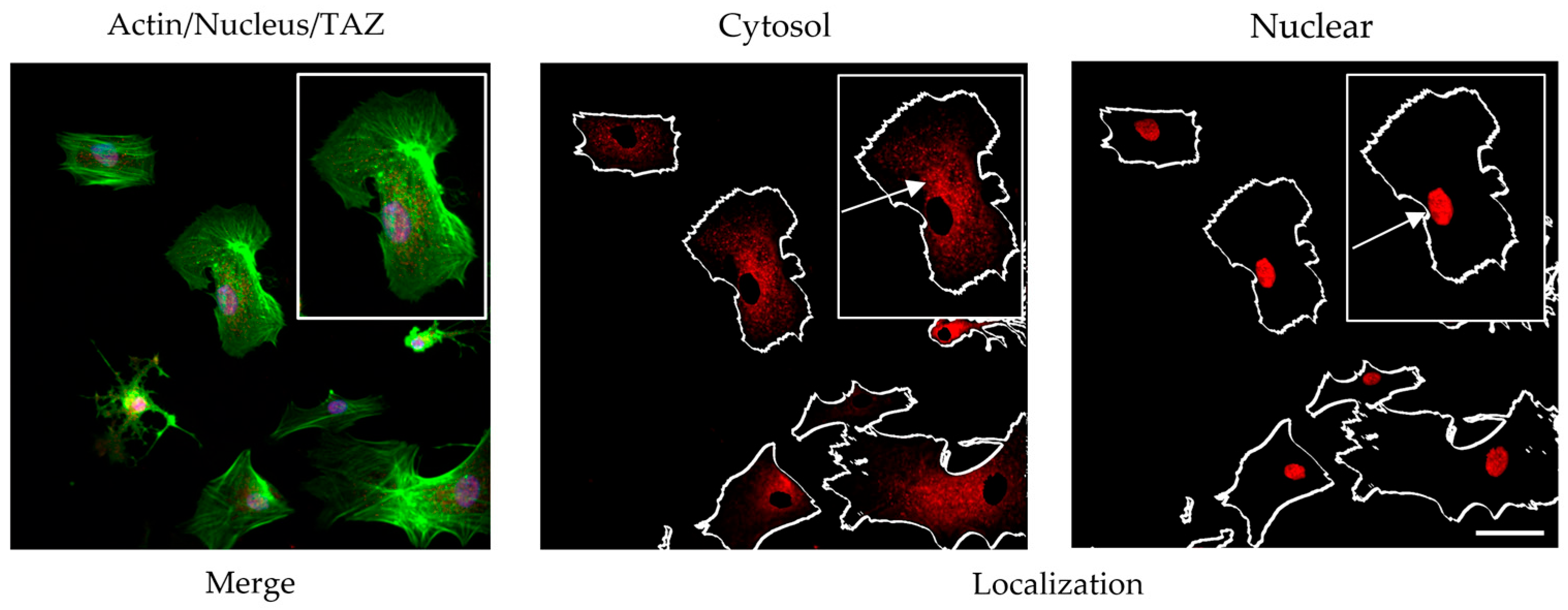

21]. In parallel, emerging evidence underscores the pivotal role of the Hippo signaling pathway in relaying mechanical cues to the nucleus. To concurrently assess FA dynamics and Hippo pathway activation during ADMSC adhesion to glycated collagen substrates, we focused on the immunofluorescent visualization of FAs and the YAP/TAZ signaling axis, the principal intracellular effectors of Hippo pathway.

A preliminary investigation was conducted using a previously validated protocol involving a 2 h incubation under serum-free conditions [

17]. Following incubation, cells were fixed and subjected to dual immunostaining: anti-vinculin antibody was employed to visualize focal adhesions, while anti-TAZ antibody labeling was used to assess Hippo pathway activity (

Figure 4). Quantification of TAZ activity was based on the ratio of nuclear to cytoplasmic signal intensity. To ensure accurate spatial resolution, nuclear counterstaining was performed, enabling clear delineation of intra- and extranuclear compartments for precise assessment of TAZ distribution.

The morphological data obtained from this study revealed several notable findings:

At this time point (2 h) of ADMSC incubation, collagen glycation led to a reduction in the number of FAs. Nevertheless, these structures remained detectable (red), showing a persistent presence despite the overall decline. However, a subtle and rather inconclusive trend was observed toward nuclear translocation of YAP/TAZ, suggesting a potential—but not definitive—activation of this pathway under our experimental conditions.

These observations underscored the need to implement a morphometric approach for the quantitative assessment of focal adhesion (FA) dynamics and YAP/TAZ activity in a time-resolved manner. This strategy enables the characterization of the temporal progression of these processes and facilitates the determination of their dependence on incubation duration.

3.3.1. Quantification of Focal Adhesion (FA) Dynamics

Data is presented in

Table 2, which summarizes the morphometric results across all experimental settings, together with the number of cells analyzed. FA dynamics were quantified using ImageJ 1.54g software. As anticipated in

Table 2, minimal FA formation was detected after 30 min of incubation, despite the improved initial adhesion observed on glycated substrates (

Figure 1 and

Table 1). At this early time point, the number of FAs per cell was negligible (ranging from 1 to 2 per cell). By the 2 h mark, FA formation markedly increased on native collagen, reaching 98 ± 29 FAs per cell. In contrast, FA numbers were significantly reduced on glycated collagen, with GL1 and GL5 showing approximately 40% and 35% decreases, respectively (

Table 2,

Figure 5). The same trend follows also the Total area of FA, showing about a two-fold drop for GL1 and about a triple reduction for GL5 (from an initial 1407 µm

2 for Native collagen to 782 and 492 µm

2 for GL1 and GL5, respectively.

3.3.2. Quantification of YAP/TAZ Activity

The ImageJ software was further used to quantify the coordinated YAP/TAZ translocation to the nucleus, as exemplified in

Figure 3:

For this preliminary experiment, actin was used to outline the overall cell shape as a region of interest (ROI) within the cytosol, while the ROI of the nucleus was marked from the blue channel (both shown with arrows). This allowed us to measure separately the fluorescence intensity, representing YAP/TAZ activity of the nucleus and the cytosol on the red channel, and providing opportunity their ratio (nucleus vs. cytosol) to be calculated.

The next experiment was already designed to compare the YAP/TAZ activity of ADMSC between native and glycated collagens, GL1 and GL5, respectively (

Figure 6).

Figure 4 presents the morphological view upon evaluation of YAP/TAZ activity at the 2nd hour of incubation.

To provide a comprehensive overview of the process, additional time points were analyzed and are presented in

Figure 7 as quantitative data—expressed as nuclear-to-cytosolic fluorescence intensity ratios—covering 30 min, 2 h, and 5 h of incubation. Quantification was performed using ImageJ 1.54g.

The graphs depict YAP/TAZ nuclear accumulation, quantified as the ratio of fluorescence intensity between the nuclear region of interest (ROI) and the cytosolic ROI, as presented on the Y scale. Box-and-whisker plots illustrate the distribution of nuclear signaling efficiency, showing the median and interquartile range (IQR). Comparisons were performed across native collagen (control), GL-1 (1-day glycated), and GL-5 (5-day glycated) substrates at three time points: 30 min (gray), 2 h (light green), and 5 h (blue). A significant difference was found between native and GL5 at 30 min, GL1 at 30 min and 5 h, and GL5 at 30 min and 5 h.

Figure 7 summarizes the quantitative data, revealing a marked nuclear accumulation of YAP/TAZ during the early adhesion phase (30 min), with a particularly strong signal in cells cultured on glycated collagen substrates. This increase corresponds to elevated nuclear-to-cytoplasmic localization ratios, indicative of effective mechanotransduction. In glycated conditions—especially GL1—YAP/TAZ nuclear localization continues to intensify up to 2 h. In contrast, GL5 substrates show a declining signal beyond this point, which is largely resolved by 5 h. These findings suggest that glycated collagen induces a rapid, but rather transient activation of YAP/TAZ signaling, peaking during the initial 30 min adhesion window.

3.4. Morphological Evidence for an Increased Collagen Synthesis of ADMSC on Glycated Collagen

Although enhanced YAP/TAZ signaling was observed in ADMSCs at 30 min of adhesion to glycated collagen, this did not correspond to an immediate increase in collagen production, as evidenced by intracellular staining patterns shown in

Figure 8. Beginning at the 30 min time point, ADMSCs exhibited a progressive increase in fluorescence intensity indicative of intracellular collagen content, primarily localized to the perinuclear region—suggestive of various stages of Golgi-mediated processing. Notably, by the 5 h mark, distinct secretory granules became apparent at the cell periphery (arrows, bottom panel), indicating active endogenous collagen secretion. These findings suggest that collagen synthesis and secretion may proceed independently of early YAP/TAZ activation.

To validate this trend, we further analyzed endogenous collagen content at the same time points of ADMSC adhesion to native and glycated collagen substrates. The graph in

Figure 9 summarizes the data on the quantification of total collagen content per cell using a monoclonal antibody followed by a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody. Cells were incubated for 30 min, 2 h, and 5 h, as stated in the

Figure 8, legend and collagen content was assessed via ImageJ 1.54g software.

ADMSCs were cultured under the same conditions as described in

Figure 8. Following incubation, cells were fixed and immunostained using an anti-human collagen type I primary antibody, with visualization achieved via a green-fluorescent goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Fluorescence intensity, expressed as Arbitrary Photometric Units (APU) per cell, was quantified using ImageJ 1.54g software. Box-and-whisker plots represent the intensity of endogenous collagen fluorescence in AU (Arbitrary Units), displaying the median, interquartile range (IQR), and full data spread. Comparisons were made across native collagen (control), GL-1 (1-day glycated), and GL-5 (5-day glycated) substrates at three time points: 30 min (gray), 2 h (light green), and 5 h (blue).

As shown in

Figure 9, the intensity of the endogenous collagen signal increases with prolonged incubation, in a comparable ratio under both native and glycated conditions, and appearing to peak around the 2 h mark. Notably, GL5 consistently displays higher fluorescence than GL1, with nearly double the signal at 30 min and a sustained, though attenuated, difference at 2 and 5 h.

3.5. AFM Studies of Glycated Collagen

Cell adhesion may strongly depend on the geometry of the underlying substratum and the positional cues that ADMSCs can recognize there, which can be relatively easily studied by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). Typical AFM images of collagen films deposited onto mica supports, obtained from solutions of native and glycated collagens, along with corresponding cross-sectional profiles, are presented in

Figure 10. These images reveal strict differences in morphology, network formation, and fibril structure upon glycation of collagen.

Figure 10A depicts a typical self-assembled collagen network on mica, demonstrating the characteristic fibrillar morphology of native collagen. More specifically, for the morphology of the film from native collagen in

Figure 10A, one can identify a well-defined network of long, interconnected fibrils. The fibrils are relatively uniform in width and appear to be well-assembled (

Figure 10A). The height profile (bottom graph) reveals significant vertical variations, indicating distinct fibrils rising above the scanned surface. Considering the network density, it appears to be relatively dense, with good surface coverage, as evidenced by the surface roughness measurements, which yield average values of

Furthermore, section analysis, as shown in the profile of

Figure 10A, indicates collagen fibril heights of

, and widths ranging from tens to hundreds of nanometers, consistent with typical collagen fibril sizes measured by AFM [

42].

In

Figure 10B, a representative film of GL1 glycated collagen on a mica substrate is shown, illustrating that glycation (GL1) significantly disrupts the self-assembly of collagen into well-defined fibrils. This suggests that glycation interferes with normal fibrillogenesis, likely by altering the protein’s structure and hindering proper intermolecular interactions. The morphology of the film reveals a much sparser distribution of collagen compared to native collagen (

Figure 10A). During the self-assembly process on the mica surface, some regions remain uncovered, appearing as round, substrate-exposed areas. Additionally, there are fewer distinct fibrils, and the surface appears more aggregated and less organized. The height profile exhibits reduced variation, indicating a flatter surface with fewer prominent features. Indeed, the estimated surface roughness is nearly half that of the native collagen sample, with an Rₐ value of 0.6 nm. As seen in the image, the collagen network is sparse and poorly developed. Fibril dimension measurements further confirm that the fibrils are smaller and less defined than those in the native sample, with diameters ranging approximately from 1 to 2 nm.

Figure 10C clearly shows that glycation in the GL5 sample also disrupts collagen self-assembly, but perhaps to a lesser extent than in the GL1 sample. This suggests that the degree of glycation or the specific glycation sites might influence the extent of disruption in collagen fibrillogenesis [

43]. Analyzing the morphology of the film, one can argue that a network is more developed than that of the GL1 sample, but it is still less organized and has less fibrillar structure compared to the native collagen sample. The film remains clumped and aggregated, yet discernible fibrillar structures are apparent, as the profile demonstrates. Notably, the estimated roughness, measured as

aligns more closely with native collagen and has a higher roughness than the GL1 sample. Also, the network looks denser compared to the GL1 sample, but less dense than the native collagen sample. Fibril dimensions range roughly to 4 nm, and their features are larger and more defined than those of the GL1 sample, suggesting a better degree of fibril formation. However, they are still less organized than the fibrils of native collagen.

4. Discussion

This study reveals a dual mechanism of adhesion in adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) interacting with collagen substrates, particularly under conditions of glycation. Our data support the existence of two temporally distinct adhesion pathways: a rapid, RAGE-mediated mechanism active within the first 30 min, and a slower, integrin-dependent process that dominates at later stages. This duality is consistent with findings of Olson et al., 2021 [

44], who demonstrated that advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) disrupt integrin signaling while promoting RAGE-dependent adhesion and differentiation in myoblasts.

Emerging evidence underscores the pivotal role of the YAP/TAZ signaling axis as a central intracellular mechanism governing cellular behavior in response to mechanical stimuli [

26,

27]. The activity of this pathway is tightly regulated by the Hippo signaling cascade. When the Hippo pathway is active, YAP/TAZ undergo phosphorylation, resulting in their cytoplasmic retention and subsequent proteasomal degradation [

3,

45], reflected by a lower nuclear to cytosolic ratio. In contrast, suppression of Hippo signaling permits the nuclear translocation of unphosphorylated YAP/TAZ, where they associate with TEA domain (TEAD1–4) transcription factors to drive the expression of genes involved in proliferation, survival, and differentiation [

46]. The temporal overlap between RAGE engagement and YAP/TAZ activation suggests a functional link between these signaling axes. In our study, YAP/TAZ nuclear localization peaked during early adhesion (30 min), coinciding with enhanced attachment to glycated collagen. This activity diminished at later time points (2–5 h), when focal adhesions matured and integrin signaling became dominant. Ref. [

47] similarly reported that YAP/TAZ activity in mesenchymal stem cells is tightly regulated by ECM composition and mechanical cues, with collagen deposition enhancing integrin-mediated mechanotransduction. Our findings extend this concept by suggesting that RAGE signaling may serve as an alternative mechanosensitive pathway during early adhesion events.

Glycation of collagen significantly altered the adhesion profile of ADMSCs. Glycated substrates accelerated early adhesion, likely via RAGE signaling, while attenuating focal adhesion formation, as evidenced by reduced vinculin-positive structures. These observations align with the work of Lucas Olson and colleagues [

44], who showed that AGE-modified collagen suppresses integrin expression and cytoskeletal organization, while RAGE agonists such as S100b can restore adhesion and differentiation. The attenuation of integrin-mediated adhesion on glycated substrates may reflect structural changes in the ECM that impair classical adhesion receptor engagement.

Interestingly, endogenous collagen synthesis, quantified via immunofluorescence, appeared to be a constitutive process, active during both early and late adhesion phases. As shown in

Figure 9, the intensity of the endogenous collagen signal increased approximately twofold with prolonged incubation, reaching a comparable ratio under both native and glycated conditions, and appearing to peak around the 2 h mark. Notably, GL5 consistently displayed higher fluorescence than GL1, with nearly double the signal at 30 min and a sustained, though attenuated, difference at 2 and 5 h. These findings indicate that while endogenous collagen synthesis proceeds in a largely constitutive manner, it remains responsive to the glycation status of the surrounding matrix, particularly under highly glycated conditions such as those in Gl5. Its expression did not correlate directly with YAP/TAZ activity, suggesting that collagen production in ADMSCs may be regulated independently of Hippo pathway dynamics. This biphasic response may reflect differential cellular adaptation to substrate integrity and mechanical feedback.

AFM analysis showed that glycation disrupted collagen self-assembly, with GL1 forming sparse, disorganized structures and GL5 displaying partial fibril restoration through increased aggregation. This improvement after 5 days is likely due to progressive formation of advanced glycation end-products and crosslinks, which stabilize collagen fibrils and modulate adhesion dynamics, consistent with our previous findings [

10].