Bio-Based Coatings: Progress, Challenges and Future Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Definition, Classification, and Global Context of Bio-Based Coatings

2.1. Definition and Evaluation Criteria of Bio-Based Coatings

2.2. Classification of Bio-Based Coatings by Raw Materials Source

2.3. Global Research Status and Data on Bio-Based Coatings

2.3.1. Publication Trend

2.3.2. Industrial Market Data

3. Bio-Based Materials Conversion Strategies

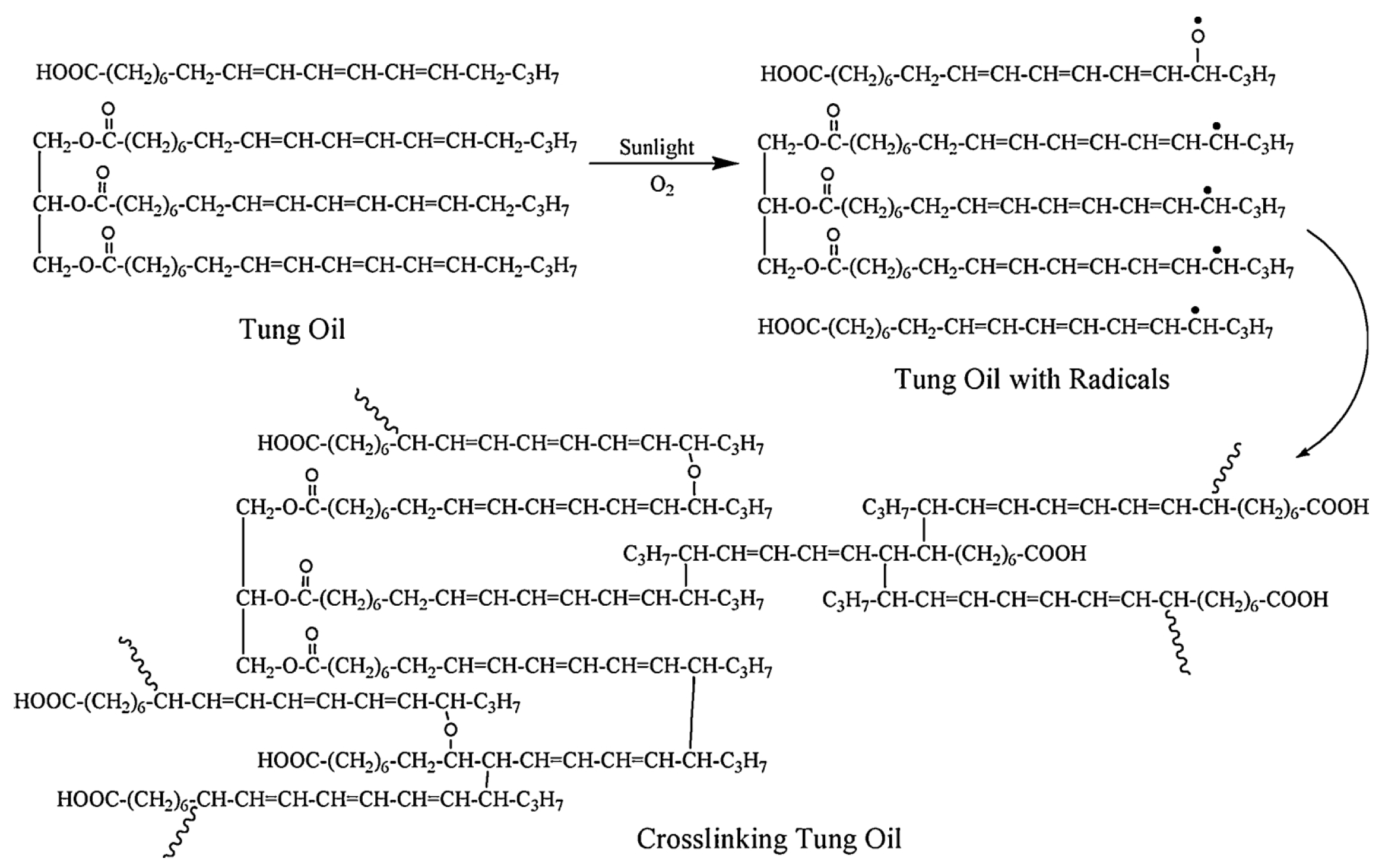

3.1. Utilize Directly

3.2. Physical Blending

3.3. Chemical Modification

3.4. Biosynthesis

- (1)

- extended polymerization times are necessary to achieve high molecular weights;

- (2)

- high reaction temperatures (typically between 100 and 140 °C) are often used for the enzymatic synthesis of polymers with high melting points and low solubility, despite a significant reduction in enzymatic activity at such elevated temperatures;

- (3)

- the cost of enzyme catalysts remains relatively high.

4. The Main Bio-Based Coatings

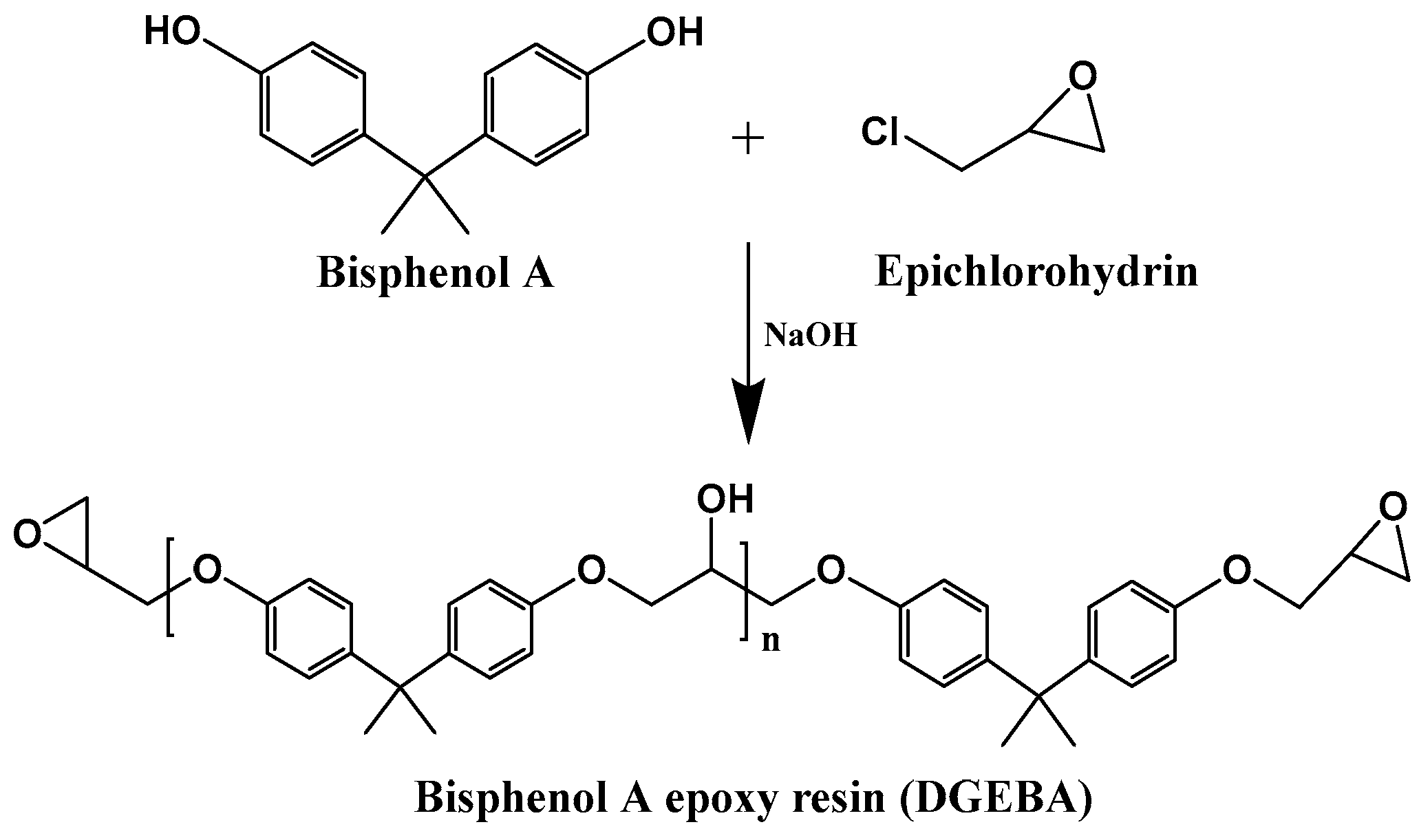

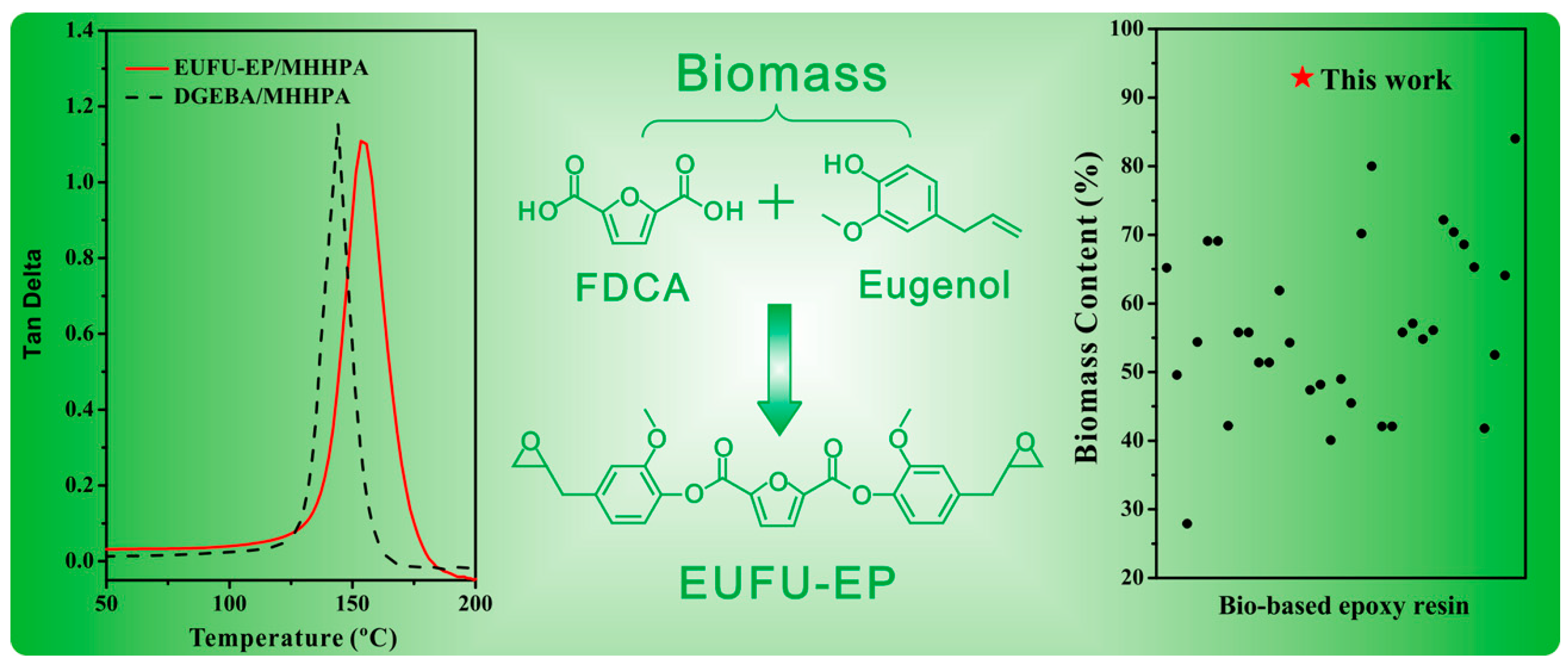

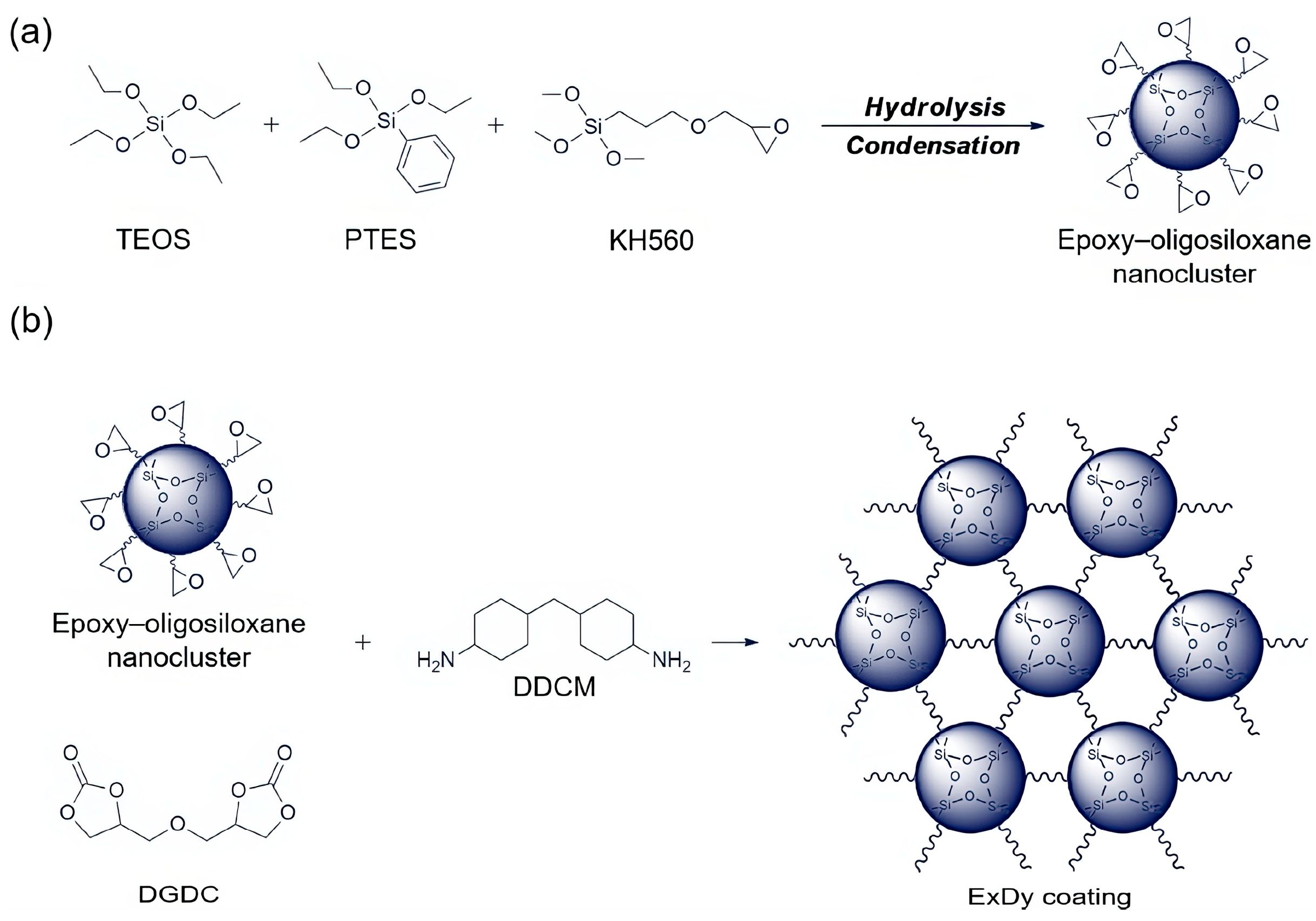

4.1. Bio-Based Epoxy Resin Coatings

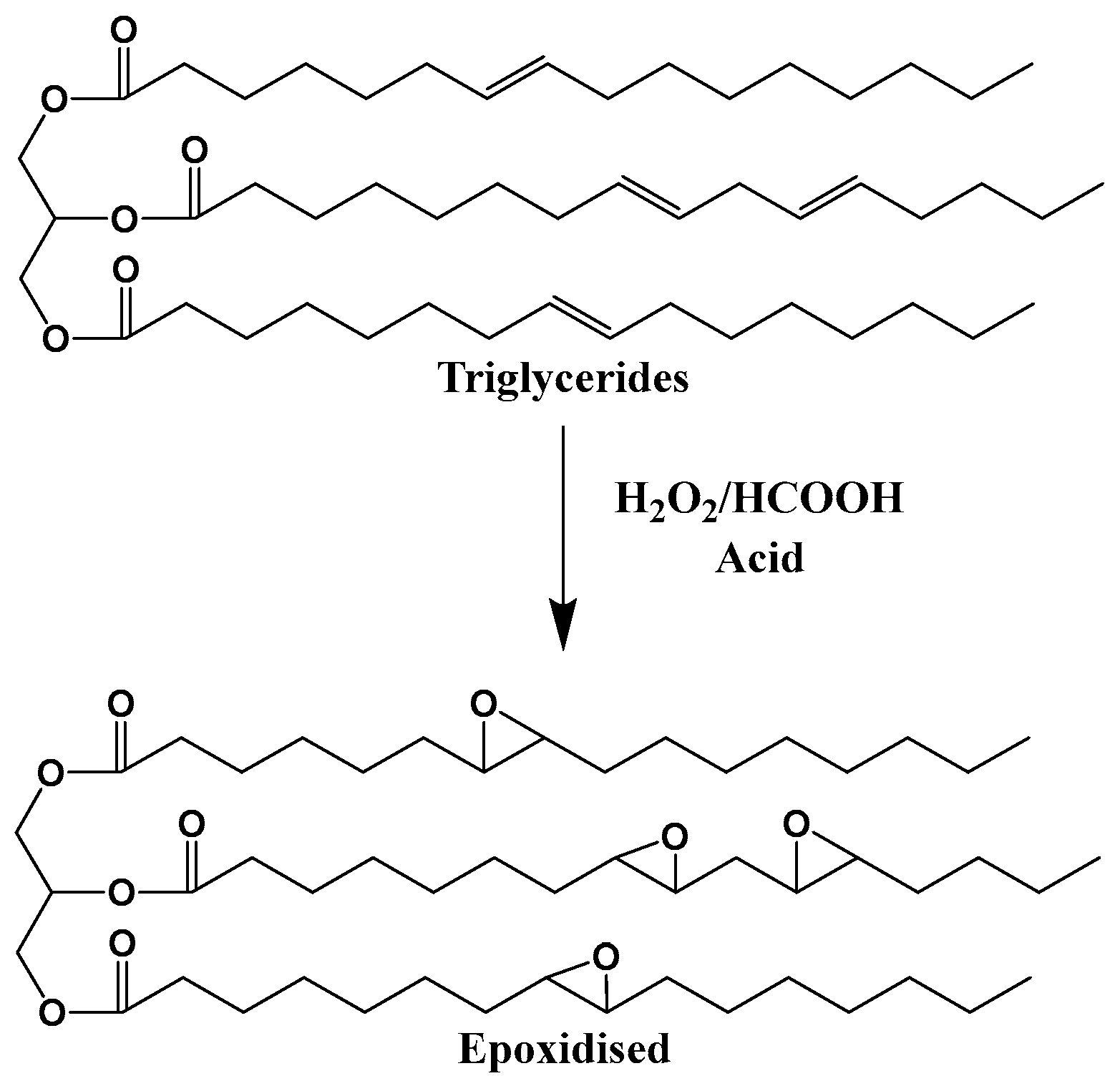

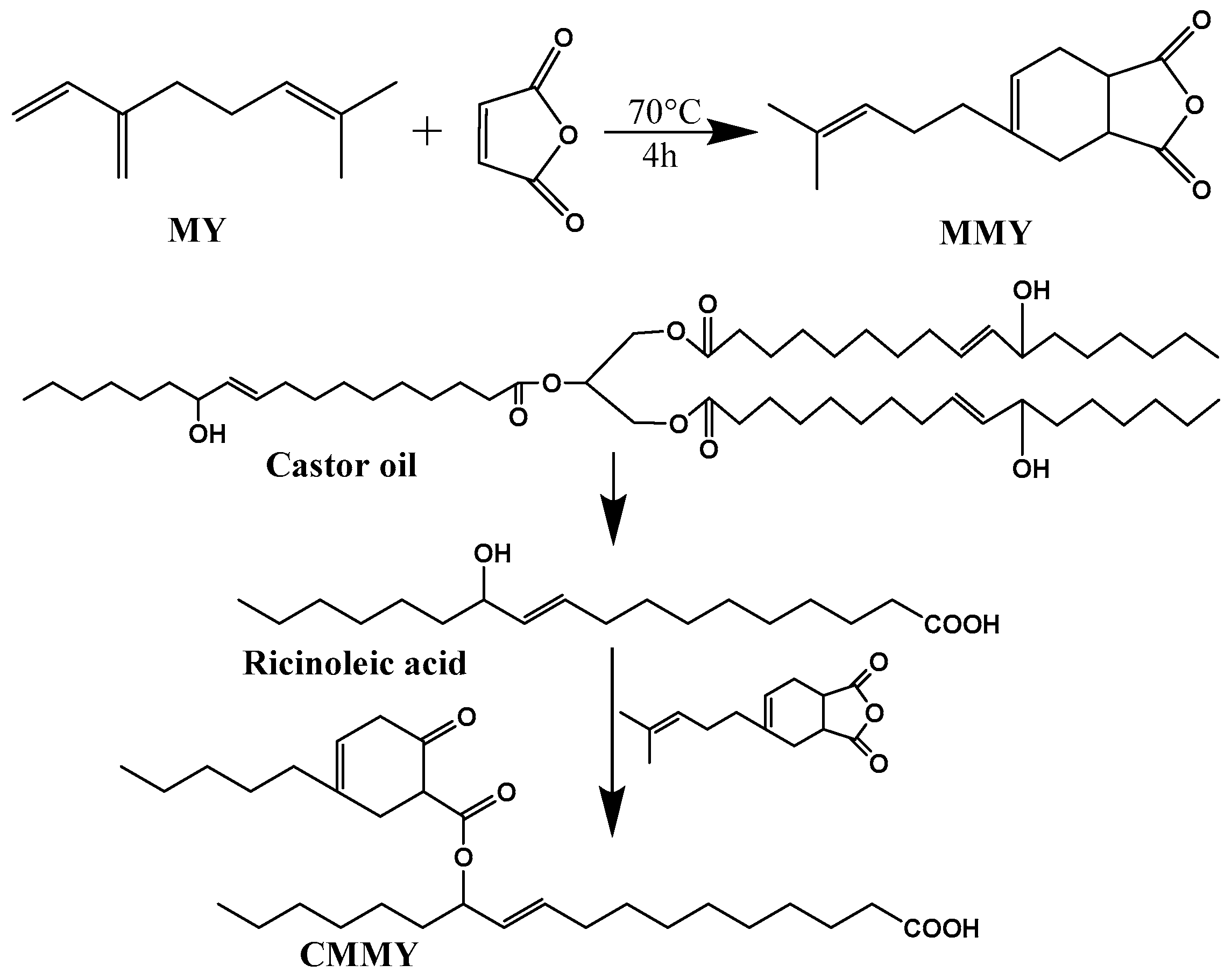

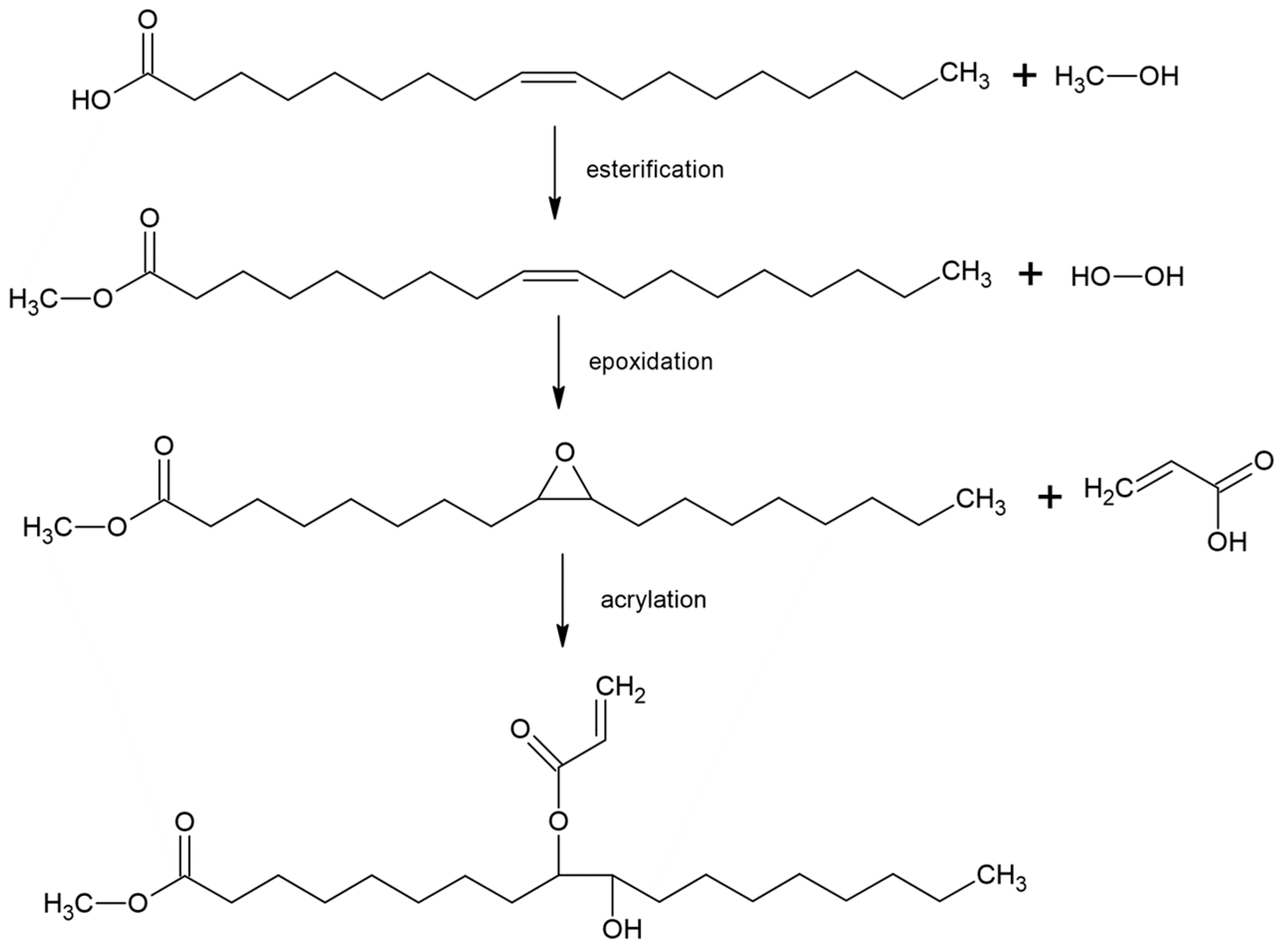

4.1.1. Plant Oils

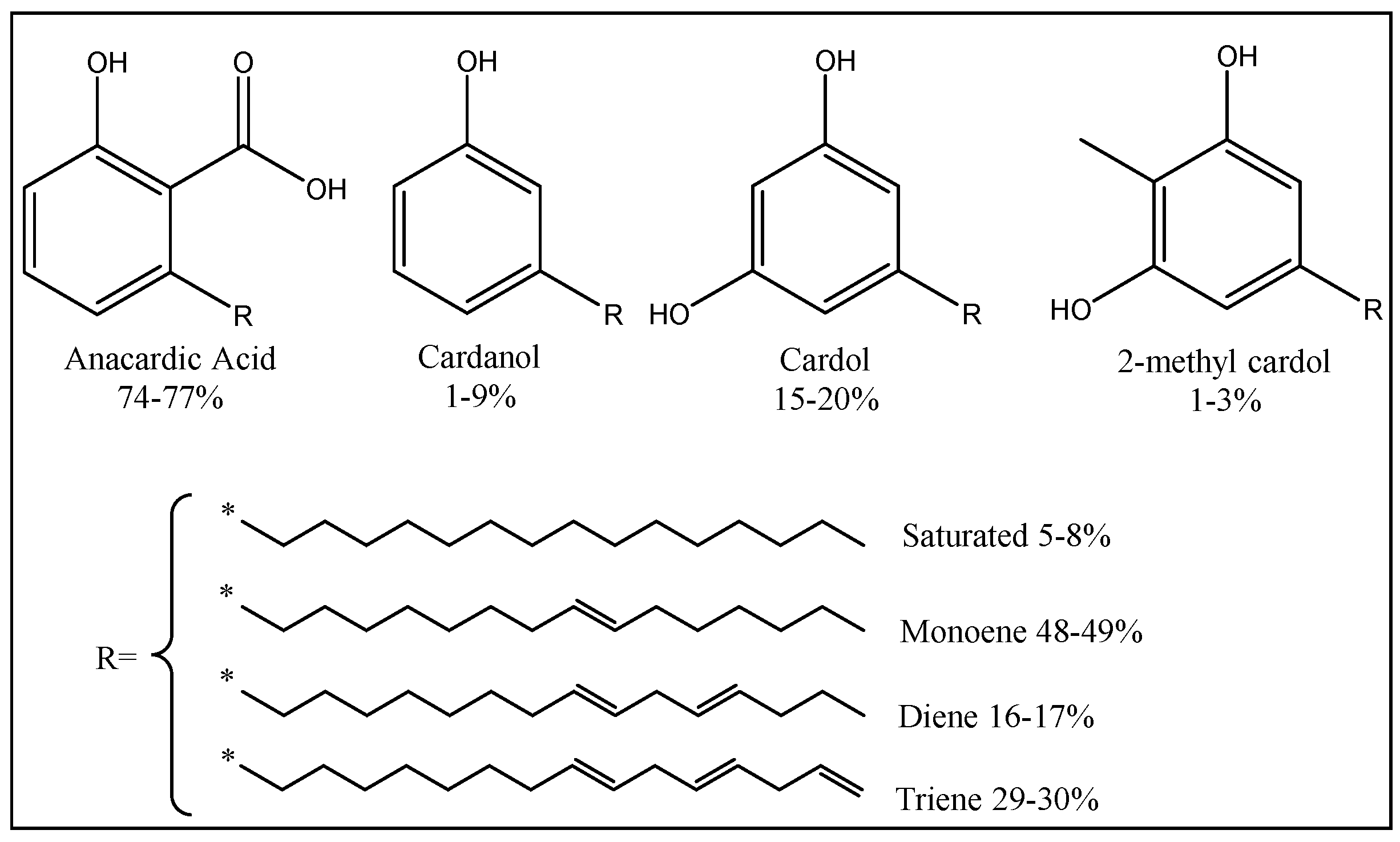

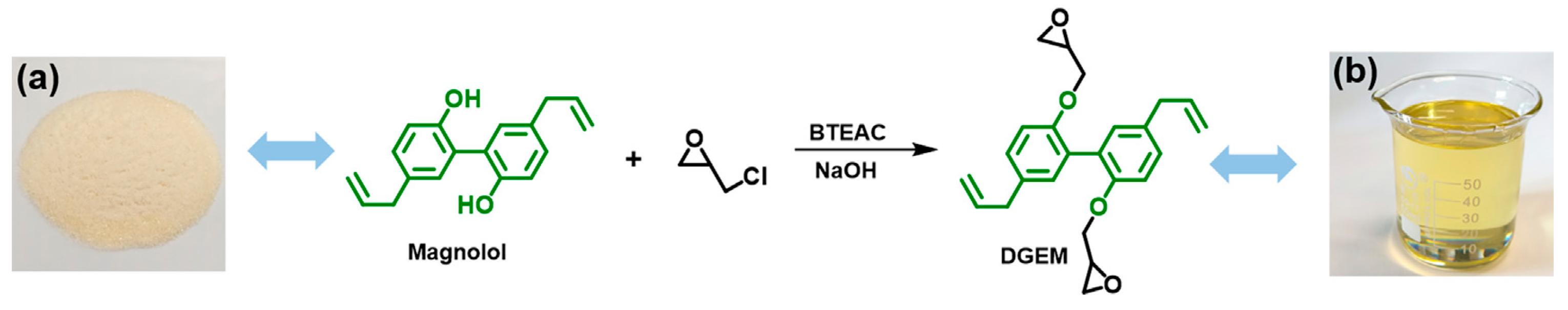

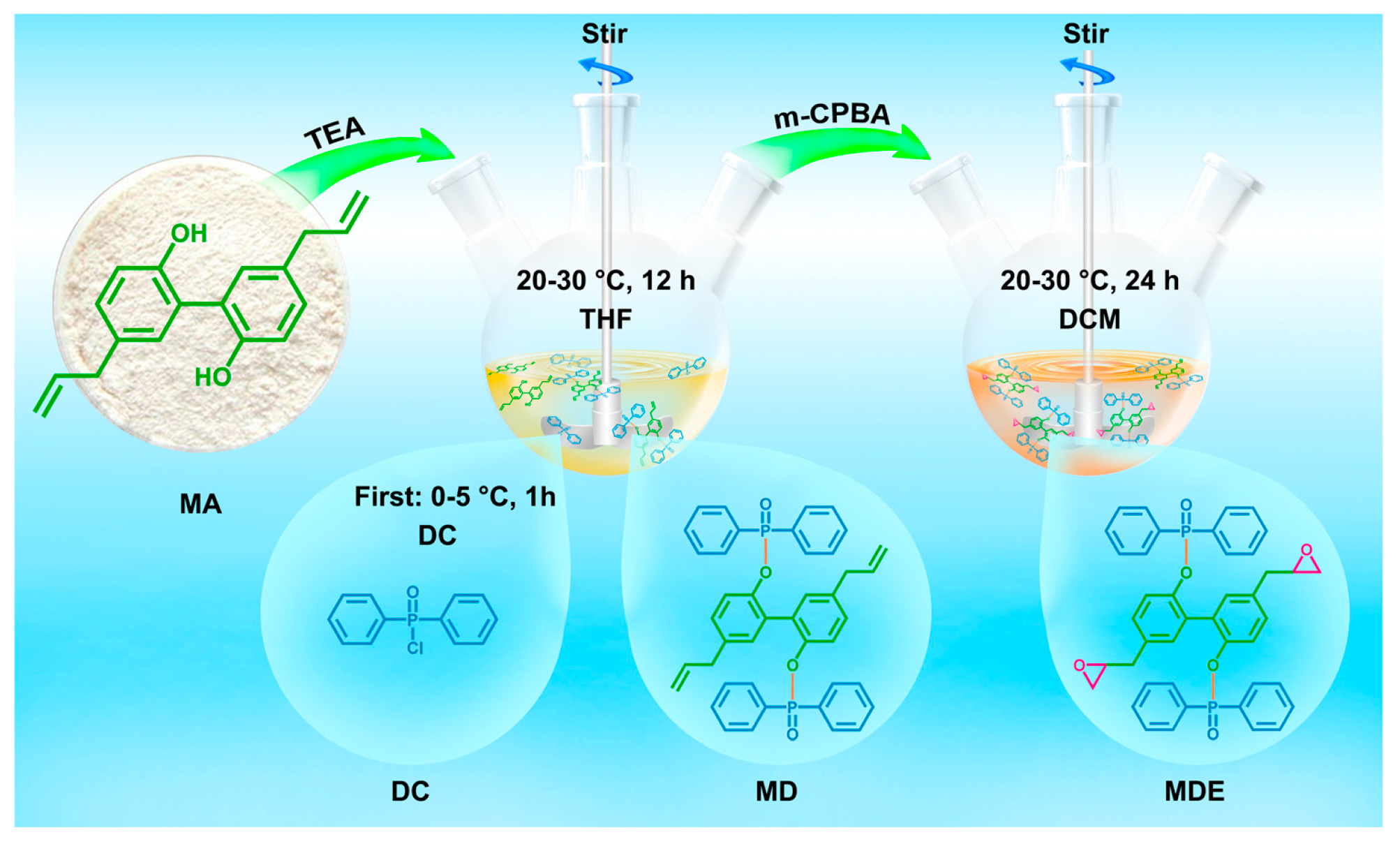

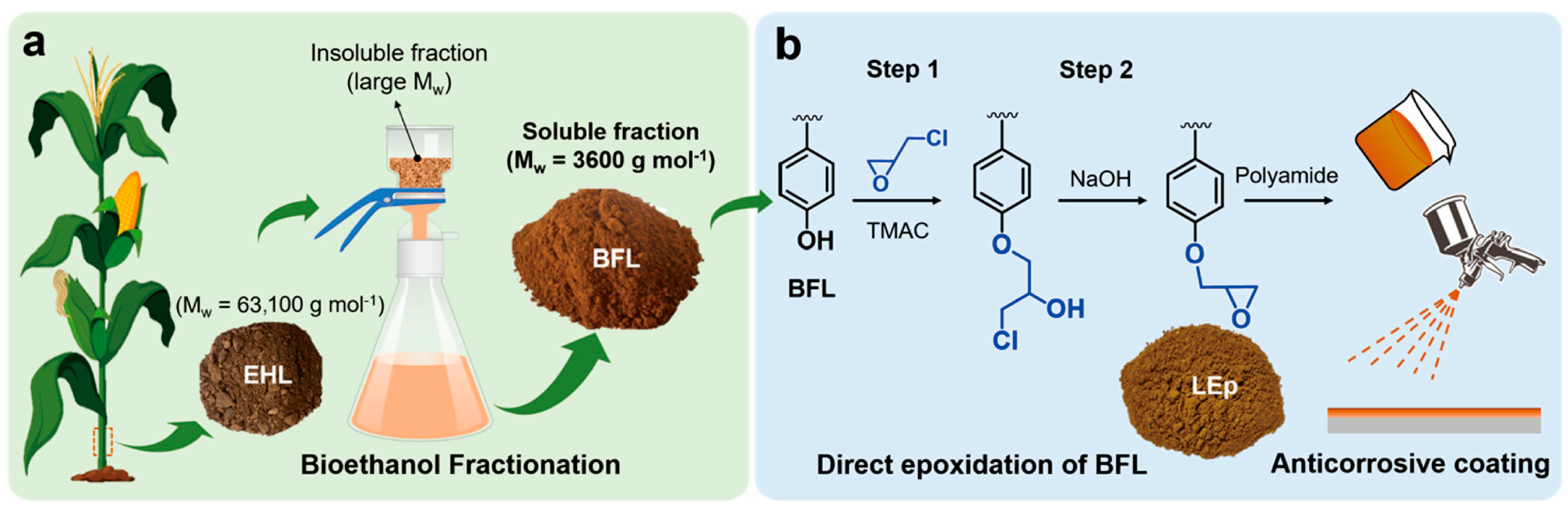

4.1.2. Plant Phenols

4.2. Bio-Based Polyurethane Coatings

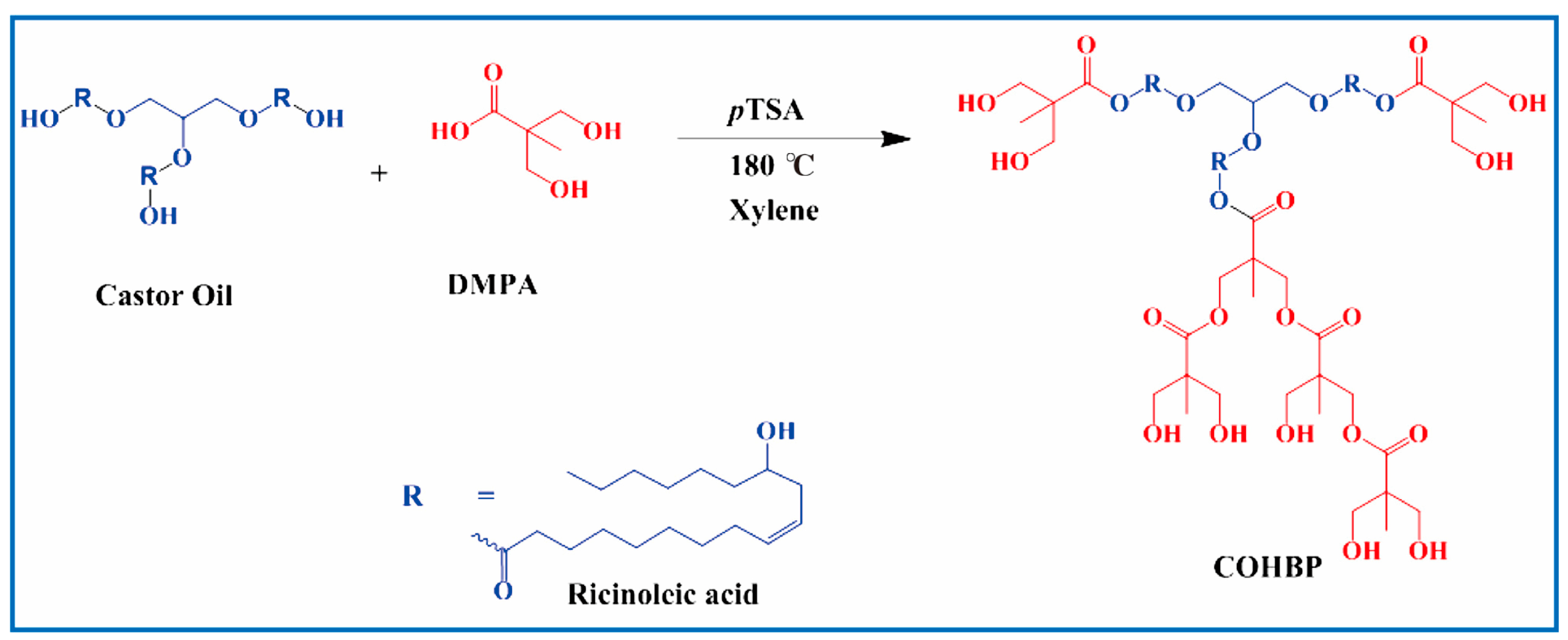

4.2.1. Bio-Based Polyols

4.2.2. Bio-Based Isocyanates

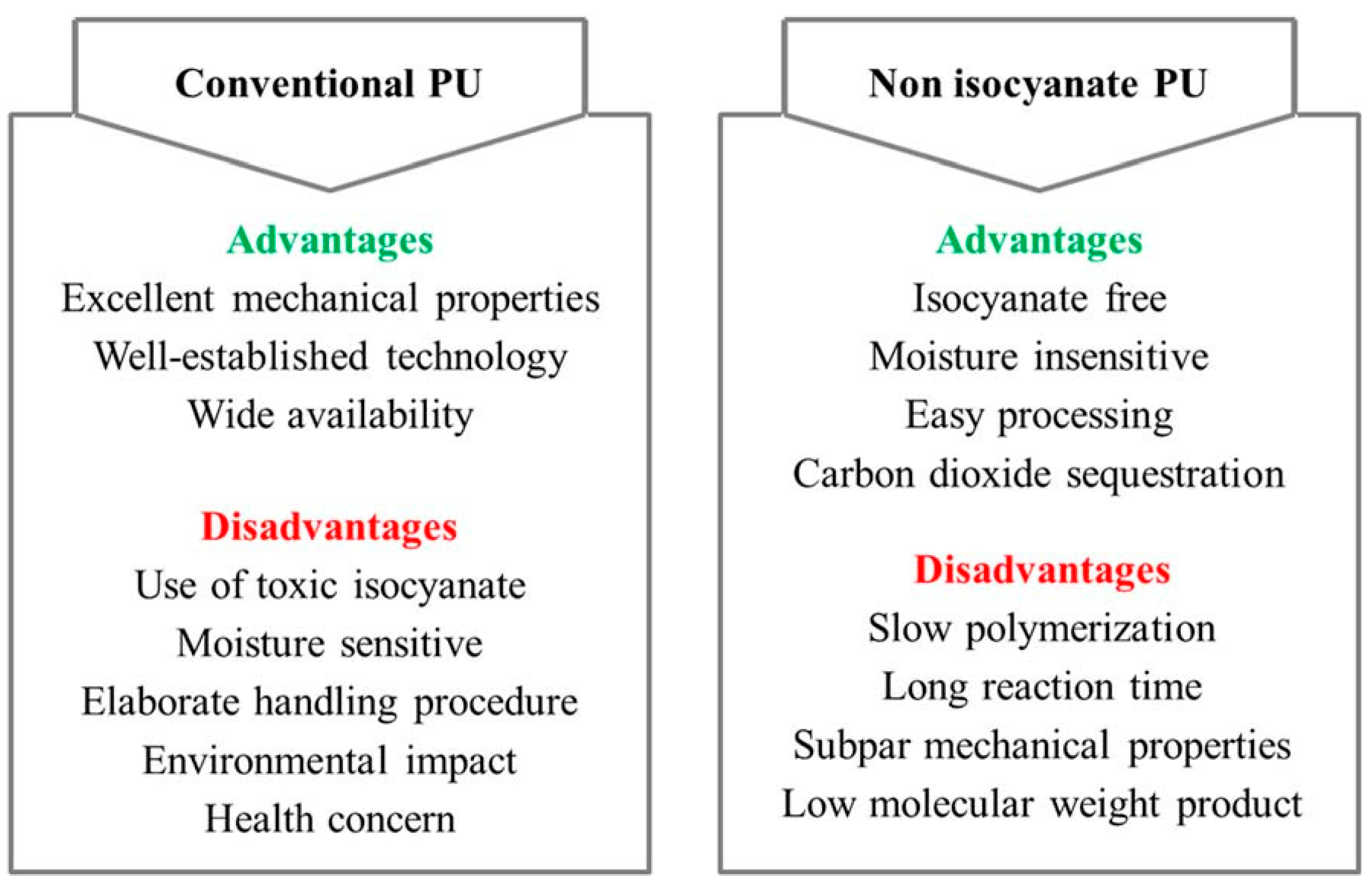

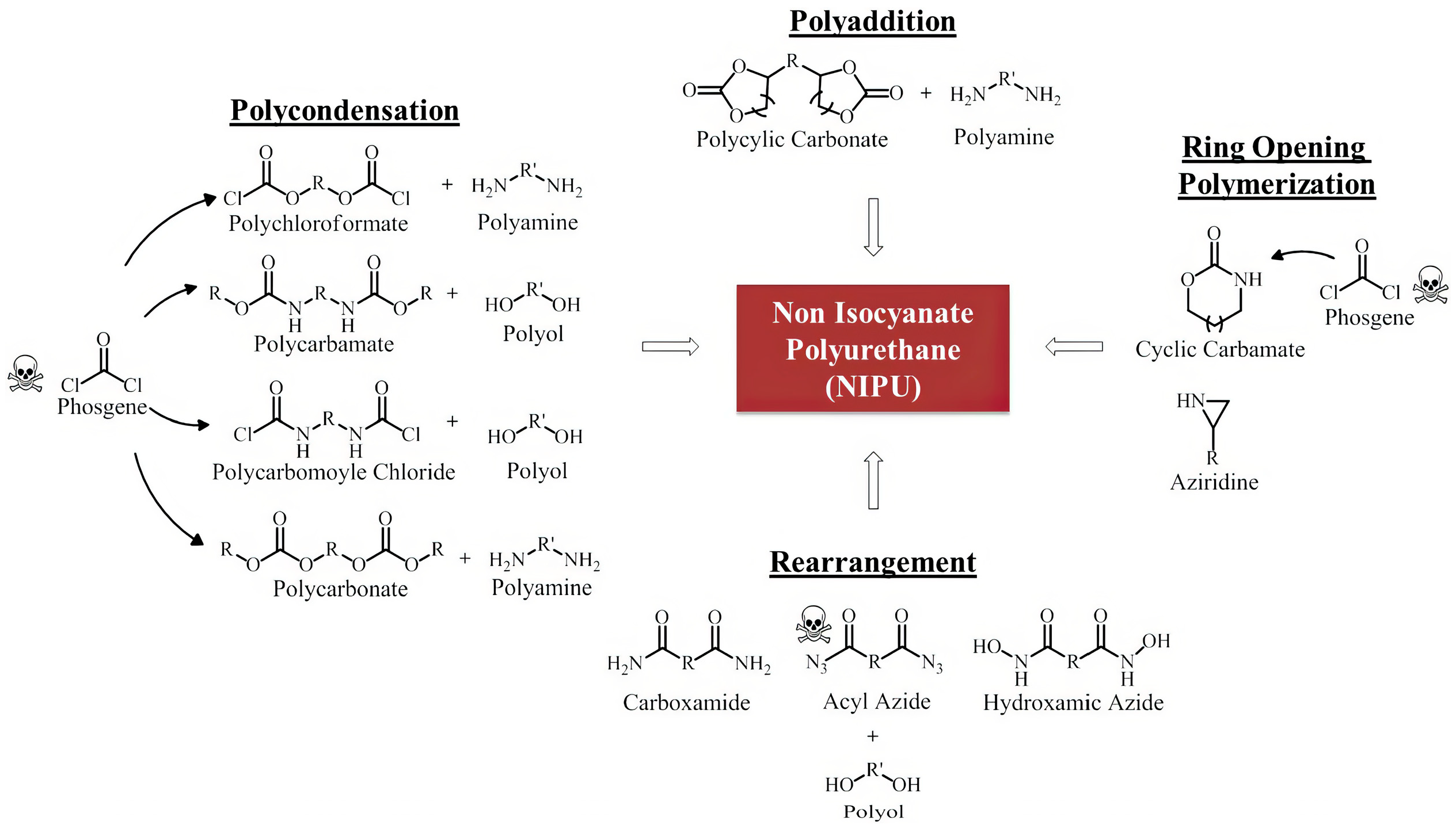

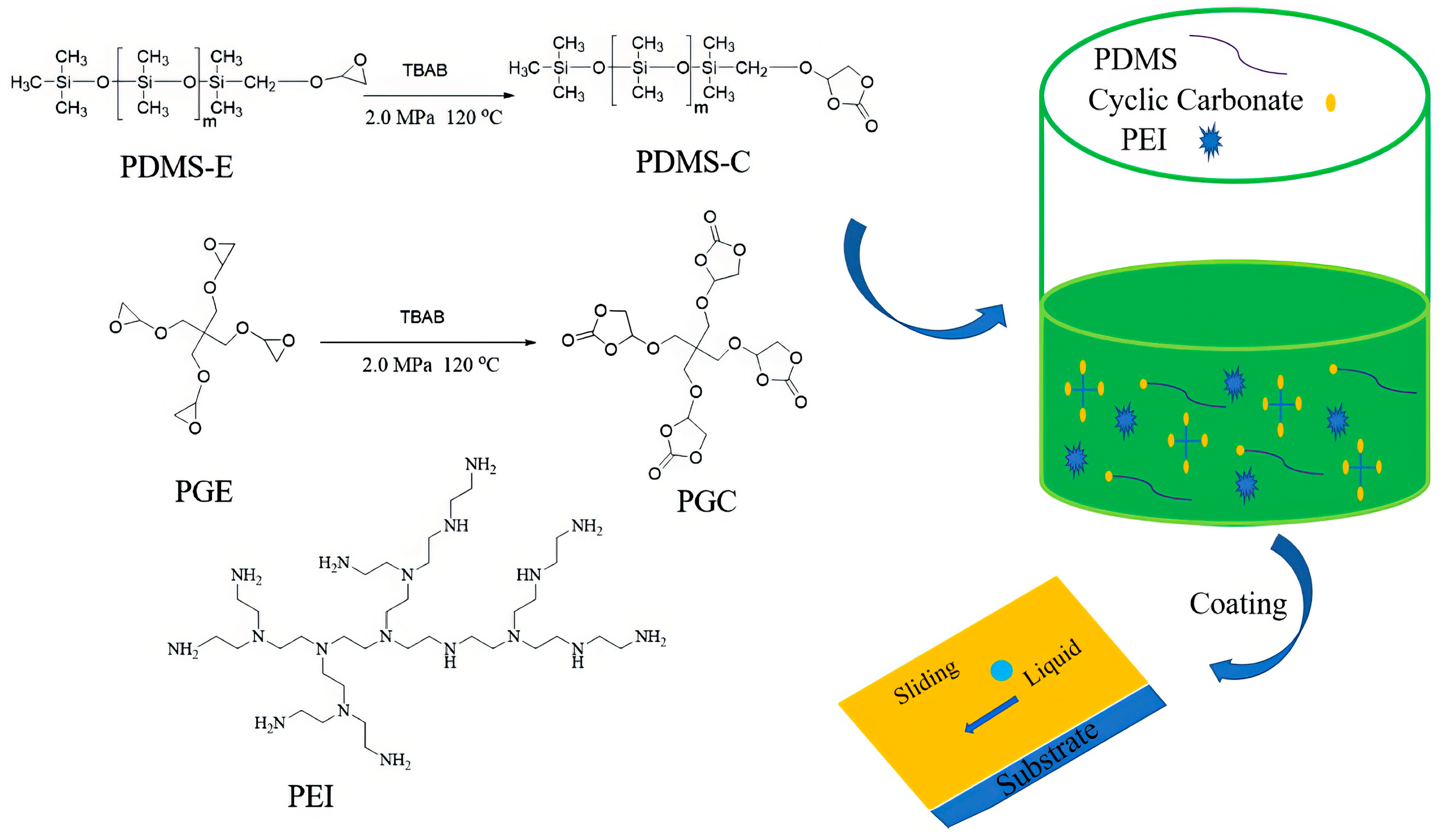

4.2.3. Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes

4.3. Bio-Based Alkyd Coatings

- replacing petroleum-derived polyols with bio-based alternatives [139];

4.4. Bio-Based Acrylic Coatings

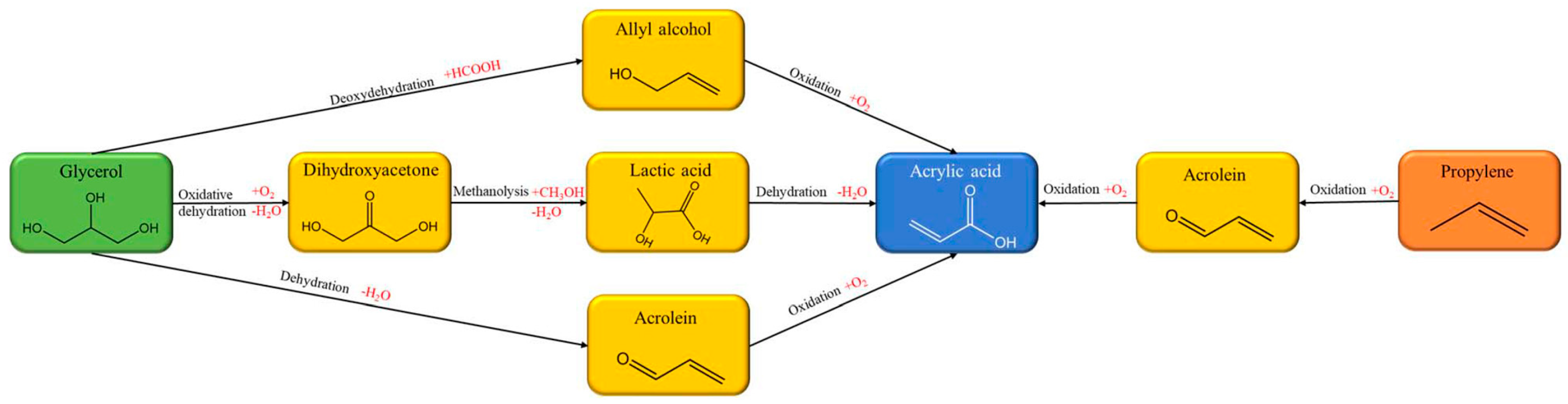

4.4.1. Synthesis of Bio-Based Acrylic Monomers

4.4.2. Construction of High-Performance Bio-Based Acrylic Resins

4.4.3. Optimization and Functional Enhancement of Coating Performance

4.5. Critical Comparison of Major Bio-Based Polymer Coatings

4.6. Intelligent Bio-Based Coatings

5. Other Key Bio-Based Components in Coating Formulations

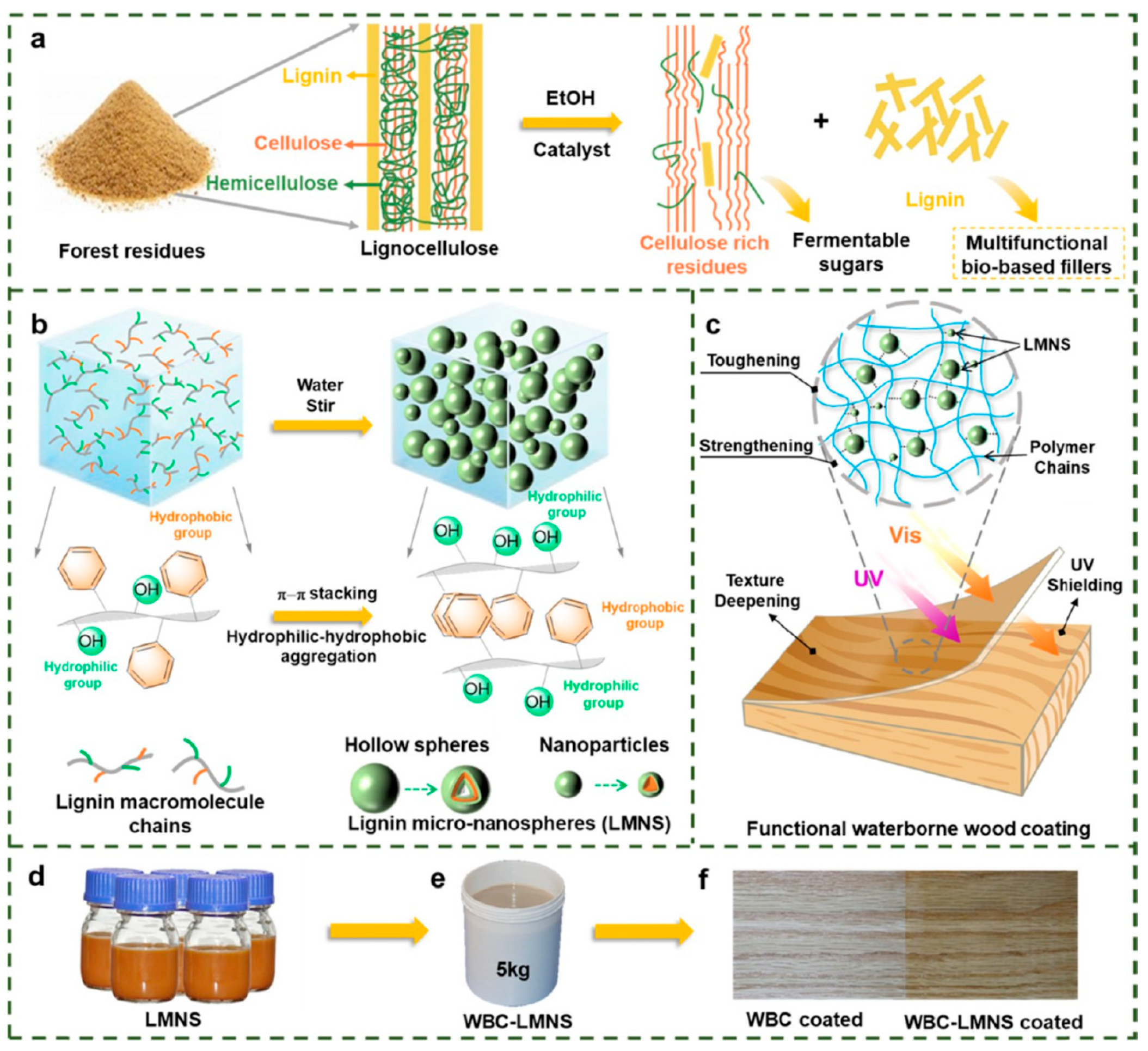

5.1. Bio-Based Pigments and Fillers

5.1.1. Bio-Based Pigments

5.1.2. Bio-Based Fillers

5.2. Bio-Based Additives

5.3. Bio-Based Solvents

6. Current Challenges and Future Outlook

6.1. The Main Current Challenges and Limitations

6.1.1. Technical and Performance Bottlenecks

6.1.2. Industrialization and Market Barriers

6.1.3. Lagging Development of Standard Systems and Certification Frameworks

6.2. Future Outlook of Bio-Based Coatings

6.2.1. Precise Design of High-Performance Bio-Based Resins

6.2.2. Breakthroughs in Key Auxiliary Component Technologies

6.2.3. Advancement of Advanced Application Technologies

6.2.4. Improvement of Industrial Chain and Standard Systems

6.2.5. Integration of Circular Economy Concepts

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cunningham, M.F.; Campbell, J.D.; Fu, Z.; Bohling, J.; Leroux, J.G.; Mabee, W.; Robert, T. Future green chemistry and sustainability needs in polymeric coatings. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 4919–4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czachor-Jadacka, D.; Biller, K.; Pilch-Pitera, B. Recent development advances in bio-based powder coatings: A review. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2023, 21, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahereh, H. Bio-Based Oligomers: Progress, Applications, and Future Perspectives. Sus. Chem. Eng. 2024, 5, 471–480. [Google Scholar]

- Eissen, M.; Metzger, J.O.; Schmidt, E.; Schneidewind, U. 10 Years after Rio-Concepts on the Contribution of Chemistry to a Sustainable Development. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 414–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raquez, J.M.; Deléglise, M.; Lacrampe, M.F.; Krawczak, P. Thermosetting (bio)materials derived from renewable resources: A critical review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2010, 35, 487–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chek, Y.W.; Ang, D.T.-C. Progress of bio-based coatings in waterborne system: Synthesis routes and monomers from renewable resources. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 188, 108190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bio-Based Coatings Market Size to Reach USD 29.4 Billion by 2032 Consumer Demand for Green Products Drive Market Growth, Research by SNS Insider. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2024/09/03/2939779/0/en/Bio-Based-Coatings-Market-Size-to-Reach-USD-29-4-Billion-By-2032-Consumer-Demand-for-Green-Products-Drive-Market-Growth-Research-by-SNS-Insider.html (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Sarcinella, A.; Frigione, M. Sustainable and Bio-Based Coatings as Actual or Potential Treatments to Protect and Preserve Concrete. Coatings 2022, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teacă, C.-A.; Roşu, D.; Mustaţă, F.; Rusu, T.; Roşu, L.; Roşca, I.; Varganici, C.-D. Natural bio-based products for wood coating and protection against degradation: A Review. BioResources 2019, 14, 4873–4901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, I.; Mata, T.M.; Martins, A.A. Environmental analysis of a bio-based coating material for automobile interiors. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 133011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Shi, L.; Fan, Z.; Yu, Y.; Liu, R. Bio-based coating of phytic acid, chitosan, and biochar for flame-retardant cotton fabrics. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 199, 109898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, F.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Sustainable biodegradable coatings for food packaging: Challenges and opportunities. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 4934–4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugoku Marine Paints’ ISCC Certified Bio-Based Epoxy Resin Paint Adopted for Mitsui Chemicals’ Liquefied Ammonia Tanker. Available online: https://jp.mitsuichemicals.com/en/release/2025/2025_0707/index.htm (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Chugoku Marine Paints’ ISCC Certified Bio-Based Epoxy Resin Coating Adopted for Mitsui Chemicals’ Liquefied Ammonia Tanker. Available online: https://www.cmp-chugoku.com/global/news-release/20250728EN.html (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Queneau, Y.; Han, B. Biomass: Renewable carbon resource for chemical and energy industry. Innovation 2022, 3, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 39514; Terminology, Definition, Identification of Biobased Materials. State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China; Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- ASTM D6866; Standard Test Methods for Determining the Biobased Content of Solid, Liquid, and Gaseous Samples Using Radiocarbon Analysis. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, America, 2024.

- Chen, C. Sustainable Bio-Based Epoxy Technology Progress. Processes 2025, 13, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 16640; Bio-Based Products-Bio-Based Carbon Content-Determination of the Bio-Based Carbon Content Using the Radiocarbon Method. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- T/CNCIA 01032; Bio-Based Coatings and Raw Materials—Alkyd Resin Coatings. China National Coatings Industry Association: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Wang, J.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y. Design and Application of Antifouling Bio-Coatings. Polymers 2025, 17, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, R.; Rahmat, A.R.; Majid, R.A.; Mustapha, S.N.H. Vegetable oil-based epoxy resins and their composites with bio-based hardener: A short review. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2019, 58, 1311–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basafa, M.; Hawboldt, K. A review on sources and extraction of phenolic compounds as precursors for bio-based phenolic resins. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2021, 13, 4463–4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobade, S.K.; Paluvai, N.R.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. Bio-Based Thermosetting Resins for Future Generation: A Review. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2016, 55, 1863–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Shun, W.; Dai, J.; Peng, Y.; Liu, X. Recent development on bio-based thermosetting resins. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 59, 1474–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimnezhad-Khaljiri, H.; Ghadi, A. Recent advancement in synthesizing bio-epoxy nanocomposites using lignin, plant oils, saccharides, polyphenols, and natural rubbers: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Ha, C.; Sun, C.; Zhou, B.; Yu, J.; Shen, M.; Mo, J. Properties of Bio-based Epoxy Resins from Rosin with Different Flexible Chains. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 13233–13240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, S.; Zhu, J. Bio-based shape memory epoxy resin synthesized from rosin acid. Iran. Polym. J. 2016, 25, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, D.M.; Phalak, G.A.; Mhaske, S.T. Design and synthesis of bio-based UV curable PU acrylate resin from itaconic acid for coating applications. Des. Monomers Polym. 2017, 20, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mauro, C.; Genua, A.; Mija, A. Fully bio-based reprocessable thermosetting resins based on epoxidized vegetable oils cured with itaconic acid. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 185, 115116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhuo, G.; Huang, Y.; Qin, M.; Liu, M.; Li, L.; Guo, C. Synthesis of bio-based epoxy resins derived from itaconic acid and application in rubber wood surface coating. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.K.; Khandelwal, V.; Manik, G. Development of completely bio-based epoxy networks derived from epoxidized linseed and castor oil cured with citric acid. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2018, 29, 2080–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaman, S.; Ahmetli, G.; Temiz, M. Newly epoxy resin synthesis from citric acid and the effects of modified almond shell waste with different natural acids on the creation of bio-based composites. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 220, 119106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayung, M.; Ghani, N.A.; Hasanudin, N. A review on vegetable oil-based non isocyanate polyurethane: Towards a greener and sustainable production route. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 9273–9299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnaturi, R.; Zagni, C.; Patamia, V.; Barbera, V.; Floresta, G.; Rescifina, A. CO2-derived non-isocyanate polyurethanes (NIPUs) and their potential applications. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 9574–9602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błażek, K.; Datta, J. Renewable natural resources as green alternative substrates to obtain bio-based non-isocyanate polyurethanes-review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 49, 173–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Enjoji, M.; Sakazume, K.; Ifuku, S. Bio-based epoxy/chitin nanofiber composites cured with amine-type hardeners containing chitosan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 144, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Fujigasaki, J.; Enjoji, M.; Shibita, A.; Teramoto, N.; Ifuku, S. Amino acid-cured bio-based epoxy resins and their biocomposites with chitin- and chitosan-nanofibers. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 98, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fustes-Damoc, I.; Dinu, R.; Malutan, T.; Mija, A. Valorisation of Chitosan Natural Building Block as a Primary Strategy for the Development of Sustainable Fully Bio-Based Epoxy Resins. Polymers 2023, 15, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Liu, H.; Yan, Q.; Chen, Q.; Hong, M.; Zhou, Z.X.; Fu, H. Straightforward synthesis of novel chitosan bio-based flame retardants and their application to epoxy resin flame retardancy. Compos. Commun. 2024, 48, 101949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, M.; Bacardit, A.; Sannia, G.; Lettera, V. From Leather Wastes back to Leather Manufacturing: The Development of New Bio-Based Finishing Systems. Coatings 2023, 13, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreen, A.; Mahmood, S.; Khalid, A.; Takriff, S.; Anjum, M.; Riaz, L.; Ditta, A.; Mahmood, T. Synthesis and characterization of bio-based UV curable polyurethane coatings from algal biomass residue. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2022, 14, 11505–11521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gawad, W.M.A.; Abdo, S.M. Fabrication and application of naturally sourced nano-pigments based on algal biomass in multifunctional coatings. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Saini, P.; Iqbal, U.; Sahu, K. Edible microbial cellulose-based antimicrobial coatings and films containing clove extract. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2024, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanckart, L.; Munasinghe, E.A.; Bendt, E.; Rahaman, A.; Abomohra, A.; Mahltig, B. Algae-Based Coatings for Fully Bio-Based and Colored Textile Products. Textiles 2025, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrot, L.; Zouari, M.; Schwarzkopf, M.; DeVallance, D.B. Sustainable biocarbon/tung oil coatings with hydrophobic and UV-shielding properties for outdoor wood substrates. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 177, 107428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Qian, J.; Qu, L.; Yan, N.; Yi, S. Effects of Tung oil treatment on wood hygroscopicity, dimensional stability and thermostability. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 140, 111647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humar, M.; Lesar, B. Efficacy of linseed- and tung-oil-treated wood against wood-decay fungi and water uptake. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 85, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Kuang, S.; Huang, J.; Man, L.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, T. Synthesis and characterization of novel renewable tung oil-based UV-curable active monomers and bio-based copolymers. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 129, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Zhao, J.; Li, G.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, T. Facile synthesis and characterization of novel multi-functional bio-based acrylate prepolymers derived from tung oil and its application in UV-curable coatings. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 138, 111585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Huang, J.; Lu, J.; Cheng, J.; Liu, C.; Hu, L.; Miao, H.; et al. High-biobased-content UV-curable oligomers derived from tung oil and citric acid: Microwave-assisted synthesis and properties. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 140, 109997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

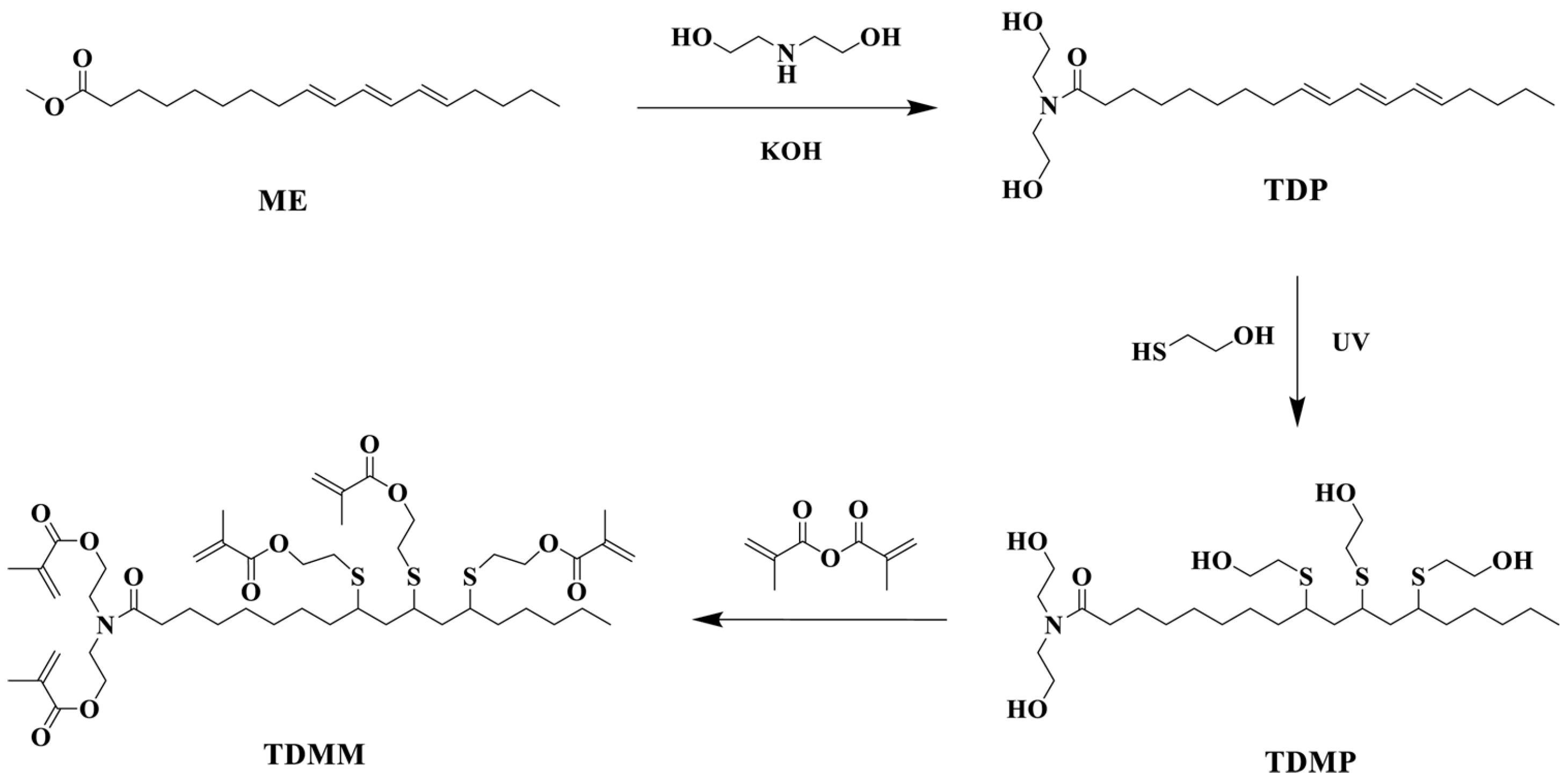

- Chu, Z.; Feng, Y.; Xie, B.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, T.; Yang, Z. Bio-based polyfunctional reactive diluent derived from tung oil by thiol-ene click reaction for high bio-content UV-LED curable coatings. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 160, 113117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V.R.L.; Santos, F.K.G.; Leite, R.H.L.; Aroucha, E.M.M.; Silva, K.N.O. Use of biopolymeric coating hydrophobized with beeswax in post-harvest conservation of guavas. Food Chem. 2018, 259, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorram, F.; Ramezanian, A.; Hosseini, S.M.H. Shellac, gelatin and Persian gum as alternative coating for orange fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 225, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versino, F.; Lopez, O.V.; Garcia, M.A.; Zaritzky, N.E. Starch-based films and food coatings: An overview. Starch-Stärke 2016, 68, 1026–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, J.; Bhardwaj, N. Development of bio-based polymeric blends—A comprehensive review. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2024, 36, 102–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, V.; Samyn, P. Bio-Based Coatings for Paper Applications. Coatings 2015, 5, 887–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Huo, J.; Yu, Y. Bio-based episulfide composed of cardanol/cardol for anti-corrosion coating applications. Polymer 2017, 121, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, F.; Arcuri, N.; Cardinali, G.D.; Fazio, S.D. A Bio-Based Render for Insulating Agglomerated Cork Panels. Coatings 2021, 11, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

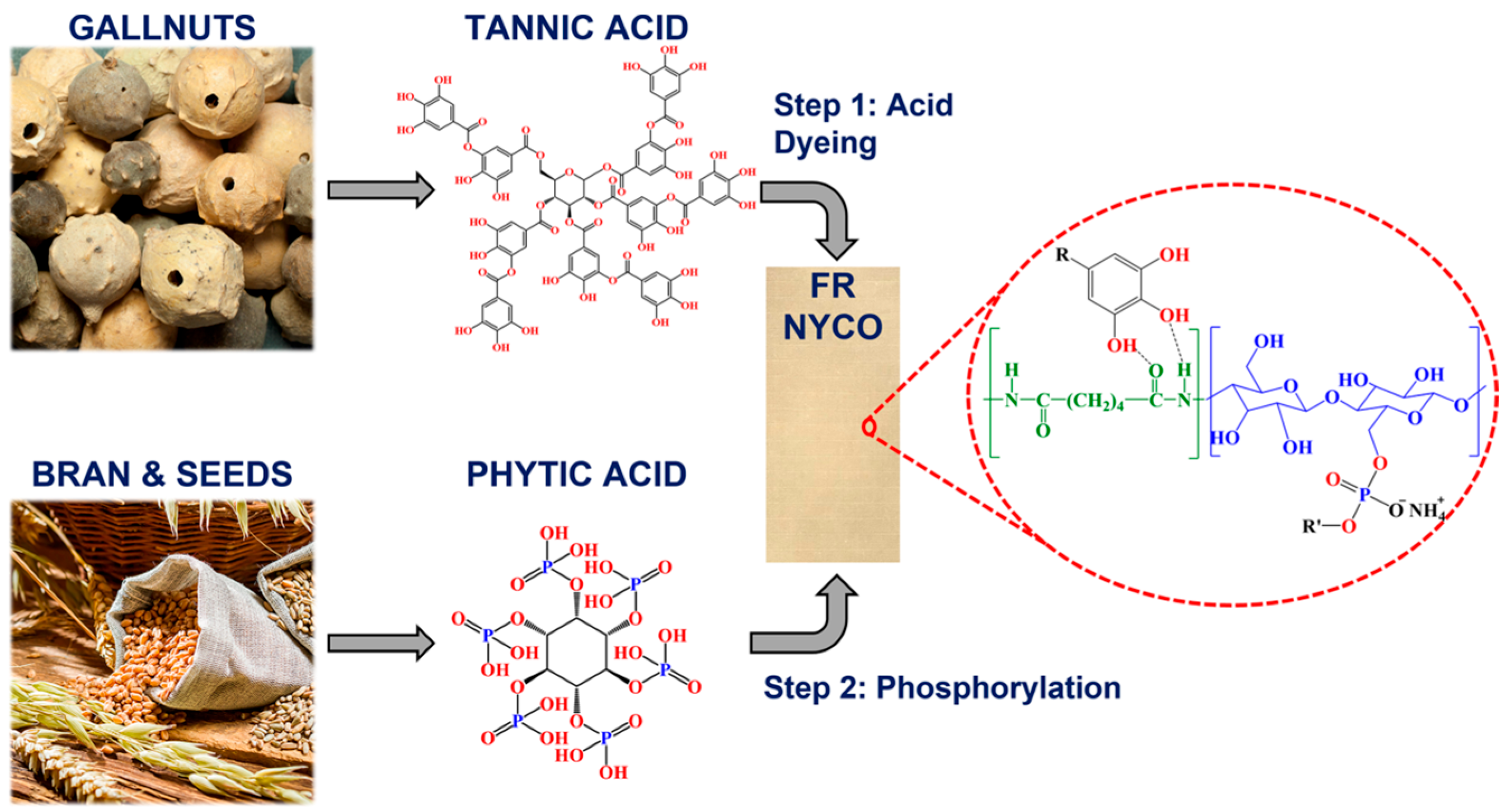

- Kulkarni, S.; Xia, Z.; Yu, S.; Kiratitanavit, W.; Morgan, A.B.; Kumar, J.; Mosurkal, R.; Nagarajan, R. Bio-Based Flame-Retardant Coatings Based on the Synergistic Combination of Tannic Acid and Phytic Acid for Nylon-Cotton Blends. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 61620–61628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, N.; Keerthana, P.; Kumar, S.A.; Kumar, G.A.; Ghosh, S. Dual purpose, bio-based polylactic acid (PLA)-polycaprolactone (PCL) blends for coated abrasive and packaging industrial coating applications. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias Montes, M.L.; D’amico, D.A.; Manfredi, L.B.; Cyras, V.P. Effect of Natural Glyceryl Tributyrate as Plasticizer and Compatibilizer on the Performance of Bio-Based Polylactic Acid/poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) Blends. J. Polym. Environ. 2019, 27, 1429–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, K.M.; Sulong, N.H.R.; Johan, M.R.; Afifi, A.M. Synergistic effect of industrial- and bio-fillers waterborne intumescent hybrid coatings on flame retardancy, physical and mechanical properties. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 149, 105905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqlibous, A.; Tretsiakova-McNally, S.; Fateh, T. Waterborne Intumescent Coatings Containing Industrial and Bio-Fillers for Fire Protection of Timber Materials. Polymers 2020, 12, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devansh; Patil, P.; Pinjari, D.V. Oil-based epoxy and their composites: A sustainable alternative to traditional epoxy. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- España, J.M.; Sánchez-Nacher, L.; Boronat, T.; Fombuena, V.; Balart, R. Properties of Biobased Epoxy Resins from Epoxidized Soybean Oil (ESBO) Cured with Maleic Anhydride (MA). J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2012, 89, 2067–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

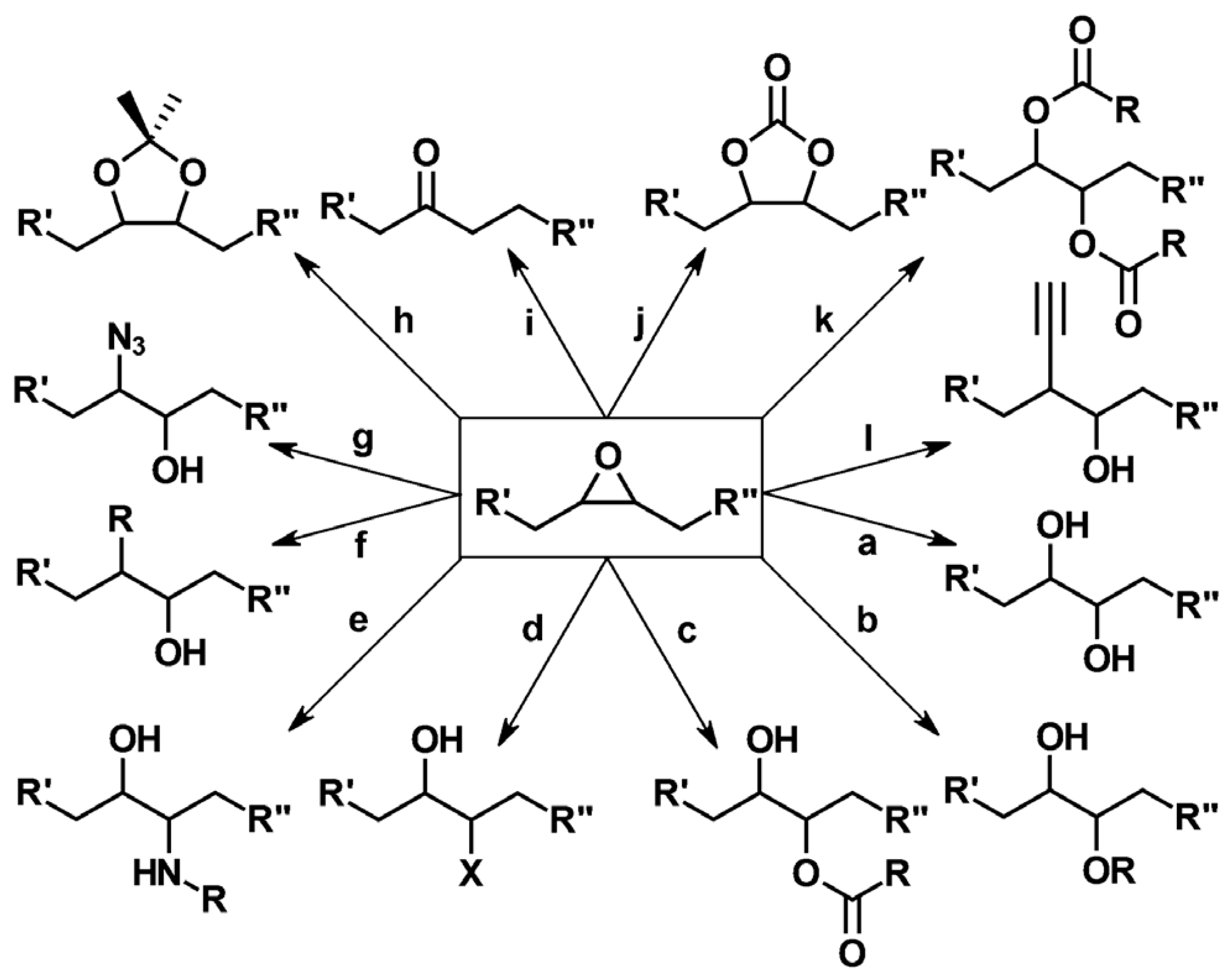

- Moser, B.R.; Cermak, S.C.; Doll, K.M.; Kenar, J.A.; Sharma, B.K. A review of fatty epoxide ring opening reactions: Chemistry, recent advances, and applications. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2022, 99, 801–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otache, M.A.; Duru, R.U.; Achugasim, O.; Abayeh, O.J. Advances in the Modification of Starch via Esterification for Enhanced Properties. J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 29, 1365–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clasen, S.H.; Muller, C.M.O.; Parize, A.L.; Pires, A.T.N. Synthesis and characterization of cassava starch with maleic acid derivatives by etherification reaction. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 180, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh Dastidar, T.; Netravali, A.N. ‘Green’ crosslinking of native starches with malonic acid and their properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 90, 1620–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, H.; Bai, R.; Bi, F.; Liu, J.; Qin, Y.; Liu, J. Synthesis, characterization, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of starch aldehyde-quercetin conjugate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 156, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Zhang, C.; Deng, Y.; Xie, P.; Liu, L.; Cheng, J. Research advances in chemical modifications of starch for hydrophobicity and its applications: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 240, 116292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapper, M.; Chiralt, A. Starch-Based Coatings for Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables. Coatings 2018, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriani, V.B.; Molina, G.; Chiumarelli, M.; Pastore, G.M.; Hubinger, M.D. Properties of cassava starch-based edible coating containing essential oils. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, E189–E194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.; Zhang, H.; Dai, H.; Xiao, H. Starch-Based Flexible Coating for Food Packaging Paper with Exceptional Hydrophobicity and Antimicrobial Activity. Polymers 2018, 10, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

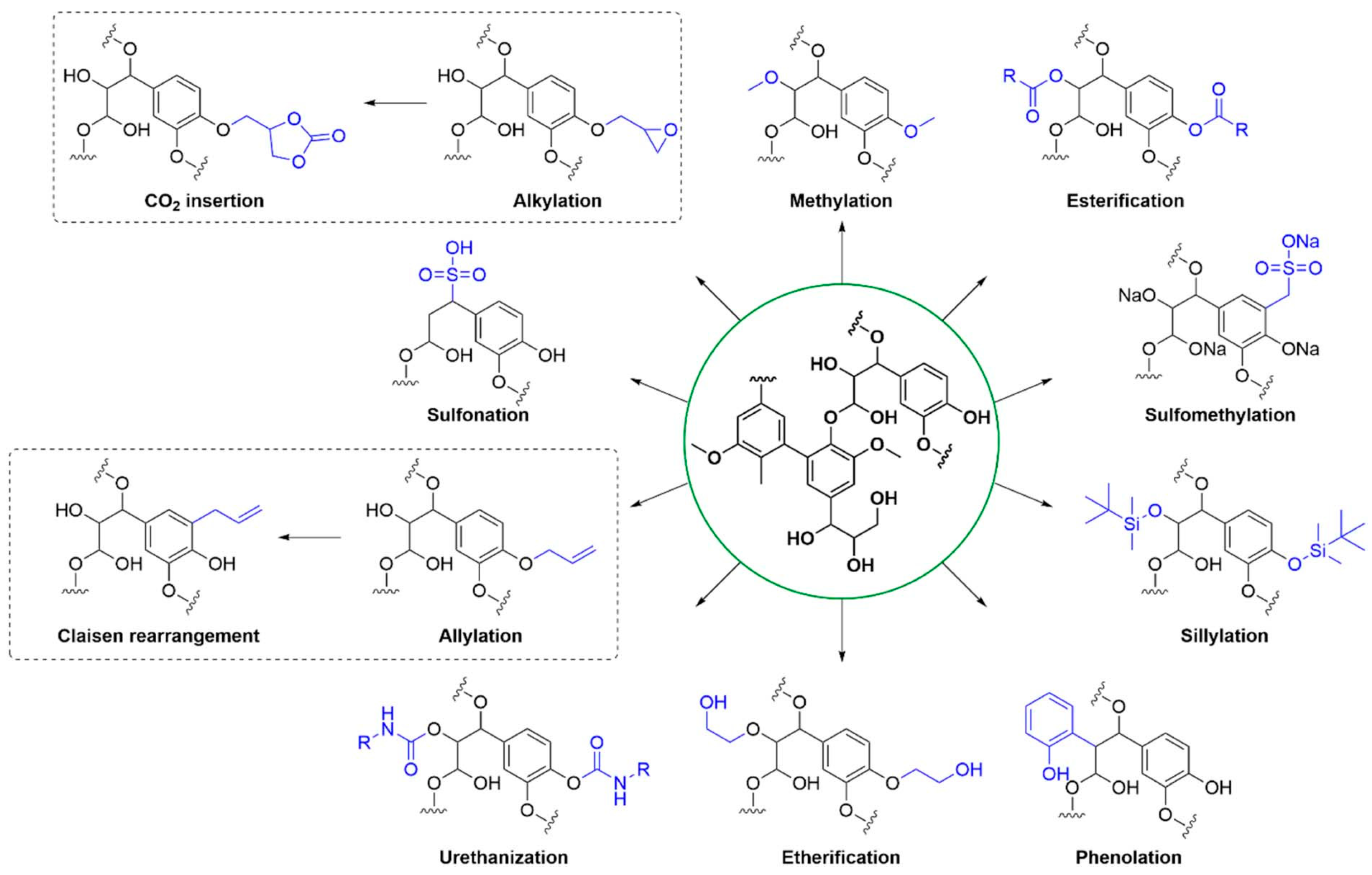

- Ruwoldt, J.; Blindheim, F.H.; Chinga-Carrasco, G. Functional surfaces, films, and coatings with lignin—A critical review. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 12529–12553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreejaya, M.M.; Jeevan Sankar, R.; K, R.; Pillai, N.P.; Ramkumar, K.; Anuvinda, P.; Meenakshi, V.S.; Sadanandan, S. Lignin-based organic coatings and their applications: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 60, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghifar, H.; Ragauskas, A. Lignin as a UV Light Blocker-A Review. Polymers 2020, 12, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kúdela, J.; Hrčka, R.; Svocák, J.; Molčanová, S. Transparent Coating Systems Applied on Spruce Wood and Their Colour Stability on Exposure to an Accelerated Ageing Process. Forests 2024, 15, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goliszek, M.; Podkościelna, B.; Smyk, N.; Sevastyanova, O. Towards lignin valorization: Lignin as a UV-protective bio-additive for polymer coatings. Pure Appl. Chem. 2023, 95, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurichesse, S.; Avérous, L. Chemical modification of lignins: Towards biobased polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 1266–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, C.; Feghali, E.; Vanbroekhoven, K.; Triantafyllidis, K.S. Recent advances in epoxy resins and composites derived from lignin and related bio-oils. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 38, 100687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarica, C.; Suriano, R.; Levi, M.; Turri, S.; Griffini, G. Lignin Functionalized with Succinic Anhydride as Building Block for Biobased Thermosetting Polyester Coatings. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 3392–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, E.-L.; Ropponen, J.; Poppius-Levlin, K.; Ohra-Aho, T.; Tamminen, T. Enhancing the barrier properties of paper board by a novel lignin coating. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 50, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Tang, S.; Chi, X.; Han, G.; Bai, L.; Shi, S.Q.; Zhu, Z.; Cheng, W. Valorization of Lignin from Biorefinery: Colloidal Lignin Micro-Nanospheres as Multifunctional Bio-Based Fillers for Waterborne Wood Coating Enhancement. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 11655–11665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

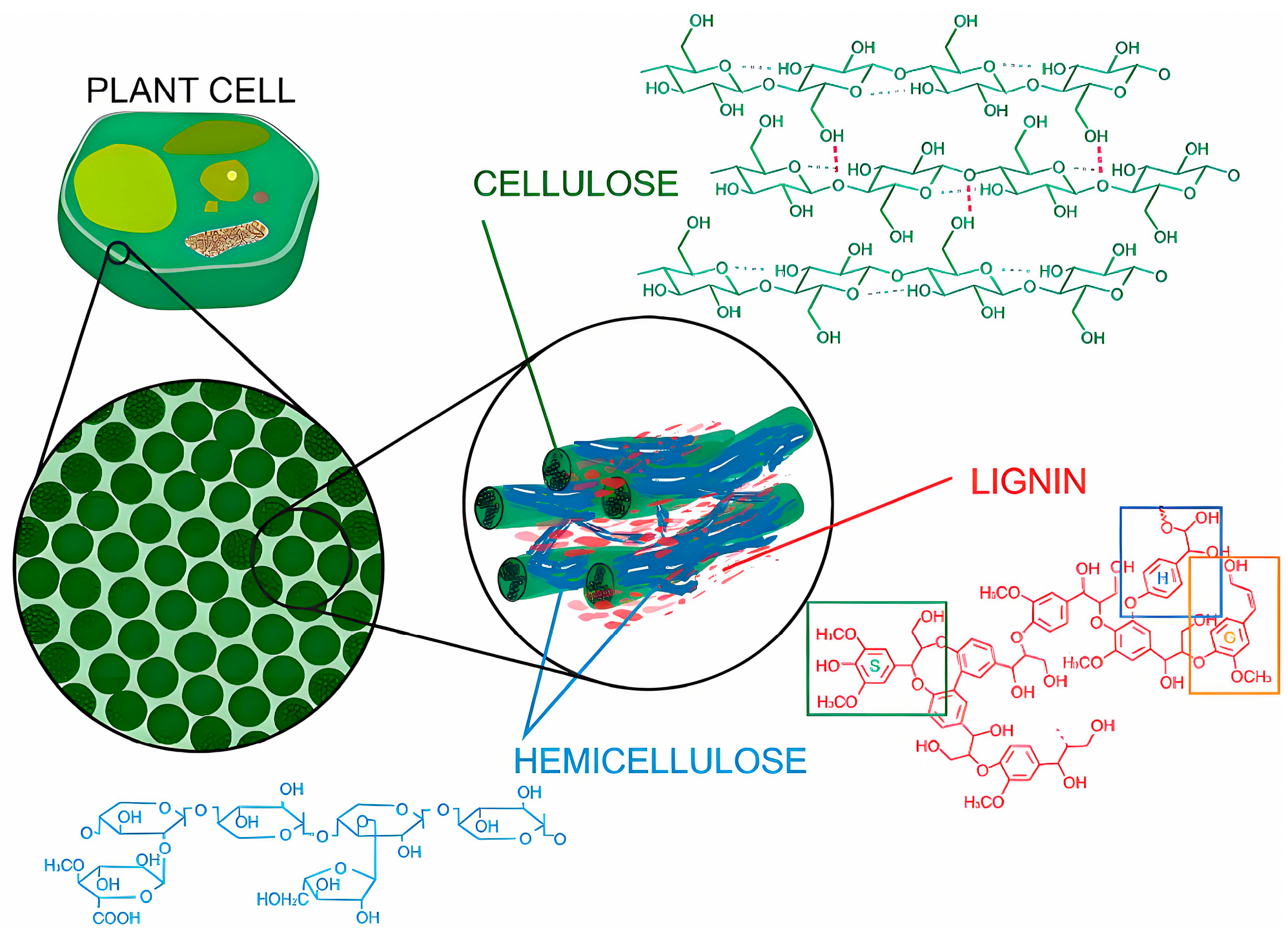

- Cherian, R.M.; Tharayil, A.; Varghese, R.T.; Antony, T.; Kargarzadeh, H.; Chirayil, C.J.; Thomas, S. A review on the emerging applications of nano-cellulose as advanced coatings. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 282, 119123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonoobi, M.; Oladi, R.; Davoudpour, Y.; Oksman, K.; Dufresne, A.; Hamzeh, Y.; Davoodi, R. Different preparation methods and properties of nanostructured cellulose from various natural resources and residues: A review. Cellulose 2015, 22, 935–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonjaroen, V.; Ummartyotin, S.; Chittapun, S. Algal cellulose as a reinforcement in rigid polyurethane foam. Algal Res. 2020, 51, 102057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irbe, I.; Filipova, I.; Skute, M.; Zajakina, A.; Spunde, K.; Juhna, T. Characterization of Novel Biopolymer Blend Mycocel from Plant Cellulose and Fungal Fibers. Polymers 2021, 13, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

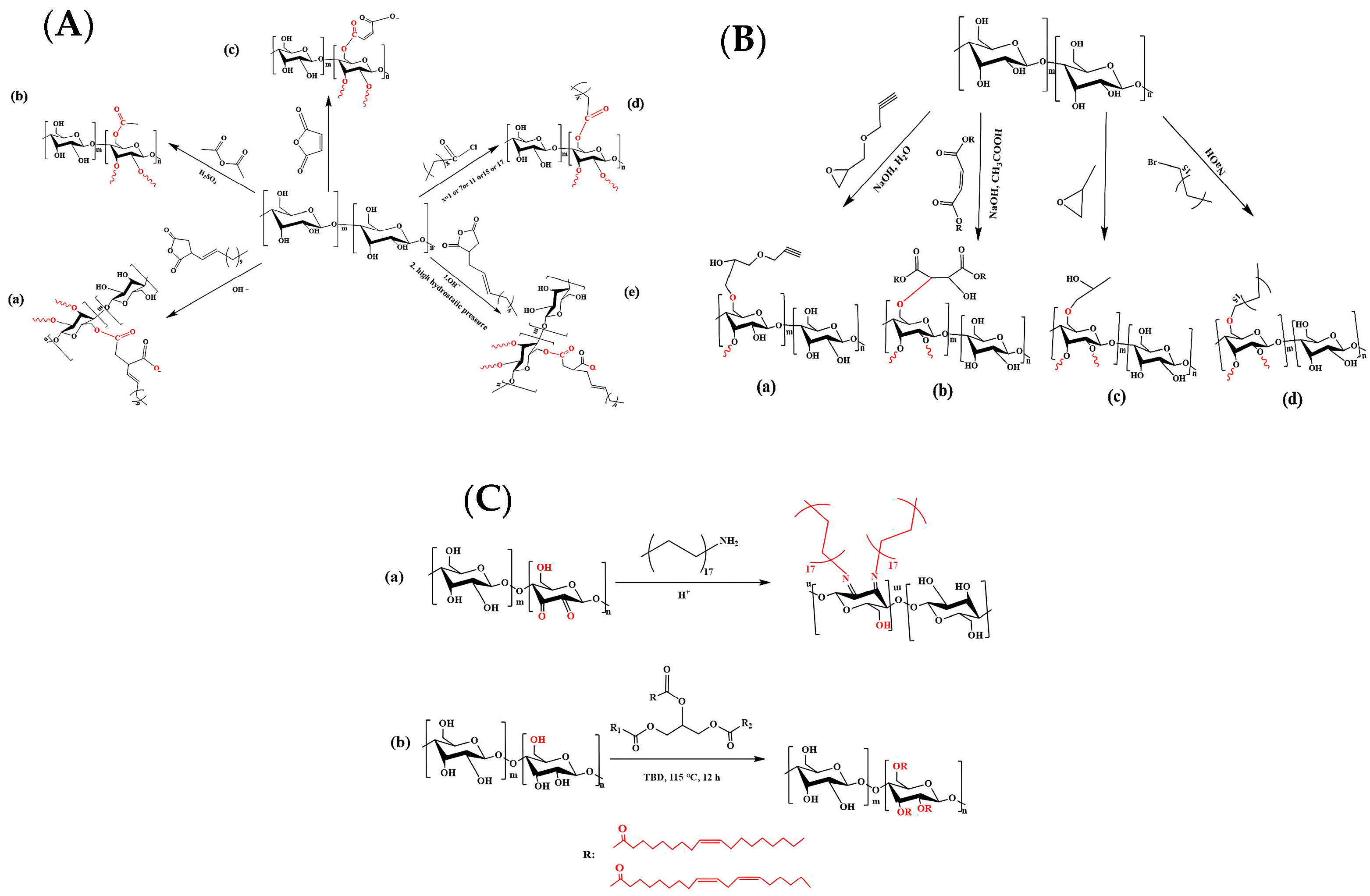

- Aziz, T.; Farid, A.; Haq, F.; Kiran, M.; Ullah, A.; Zhang, K.; Li, C.; Ghazanfar, S.; Sun, H.; Ullah, R.; et al. A Review on the Modification of Cellulose and Its Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Qi, Y.; Shen, Y.; Li, H. Research Progress on Chemical Modification and Application of Cellulose: A Review. Mater. Sci. 2022, 28, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poaty, B.; Vardanyan, V.; Wilczak, L.; Chauve, G.; Riedl, B. Modification of cellulose nanocrystals as reinforcement derivatives for wood coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2014, 77, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auclair, N.; Kaboorani, A.; Riedl, B.; Landry, V.; Hosseinaei, O.; Wang, S. Influence of modified cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) on performance of bionanocomposite coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 123, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, S.; Jämsä, S.; Talja, R.; Heikkinen, H.; Vuoti, S. Chemically modified cellulose nanofibril as an additive for two-component polyurethane coatings. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 44801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaud, F.; Faucard, P.; Tarquis, L.; Pizzut-Serin, S.; Roblin, P.; Morel, S.; Le Gall, S.; Falourd, X.; Rolland-Sabaté, A.; Lourdin, D.; et al. Enzymatic synthesis of polysaccharide-based copolymers. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 4012–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocek, M. Enzymatic Synthesis of Base-Functionalized Nucleic Acids for Sensing, Cross-linking, and Modulation of Protein-DNA Binding and Transcription. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 1730–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavadia, M.R.; Yadav, M.G.; Odaneth, A.A.; Lali, A.M. Synthesis of designer triglycerides by enzymatic acidolysis. Biotechnol. Rep. 2018, 18, e00246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legras-Lecarpentier, D.; Stadler, K.; Weiss, R.; Guebitz, G.M.; Nyanhongo, G.S. Enzymatic Synthesis of 100% Lignin Biobased Granules as Fertilizer Storage and Controlled Slow Release Systems. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 12621–12628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Loos, K. Enzymatic Synthesis of Biobased Polyesters and Polyamides. Polymers 2016, 8, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goujard, L.; Roumanet, P.-J.; Barea, B.; Raoul, Y.; Ziarelli, F.; Le Petit, J.; Jarroux, N.; Ferré, E.; Guégan, P. Evaluation of the Effect of Chemical or Enzymatic Synthesis Methods on Biodegradability of Polyesters. J. Polym. Environ. 2015, 24, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- da Silva, L.R.R.; Carvalho, B.A.; Pereira, R.C.S.; Diogenes, O.B.F.; Pereira, U.C.; da Silva, K.T.; Araujo, W.S.; Mazzetto, S.E.; Lomonaco, D. Bio-based one-component epoxy resin: Novel high-performance anticorrosive coating from agro-industrial byproduct. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 167, 106861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellido-Aguilar, D.A.; Zheng, S.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Z. Solvent-Free Synthesis and Hydrophobization of Biobased Epoxy Coatings for Anti-Icing and Anticorrosion Applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 19131–19141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonamigo Moreira, V.; Rintjema, J.; Bravo, F.; Kleij, A.W.; Franco, L.; Puiggali, J.; Aleman, C.; Armelin, E. Novel Biobased Epoxy Thermosets and Coatings from Poly(limonene carbonate) Oxide and Synthetic Hardeners. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 2708–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Li, T.; Liu, X.; Zhu, J. Research progress on bio-based thermosetting resins. Polym. Int. 2015, 65, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, M.B.; Mohana, K.N.S.; Rajitha, K.; Madhusudhana, A.M. Reduced graphene oxide-epoxidized linseed oil nanocomposite: A highly efficient bio-based anti-corrosion coating material for mild steel. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 159, 106399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, C.; Li, S.; Huang, K.; Li, M.; Mao, W.; Cao, S.; Xia, J. Study on the synthesis of bio-based epoxy curing agent derived from myrcene and castor oil and the properties of the cured products. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teijido, R.; Monteserin, C.; Blanco, M.; Odriozola, J.L.L.; Olabarria, M.I.M.; Vilas-Vilela, J.L.; Lanceros-Méndez, S.; Zhang, Q.; Ruiz-Rubio, L. Exploring anti-corrosion properties and rheological behaviour of tannic acid and epoxidized soybean oil-based fully bio-based epoxy thermoset resins. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 196, 108719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaina, C.; Ursache, O.; Gaina, V.; Serban, A.M.; Asandulesa, M. Novel Bio-Based Materials: From Castor Oil to Epoxy Resins for Engineering Applications. Materials 2023, 16, 5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, D.; Ramis, X.; Fernández-Francos, X.; De la Flor, S.; Serra, A. Preparation of new biobased coatings from a triglycidyl eugenol derivative through thiol-epoxy click reaction. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 114, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramon, E.; Sguazzo, C.; Moreira, P.M.G.P. A Review of Recent Research on Bio-Based Epoxy Systems for Engineering Applications and Potentialities in the Aviation Sector. Aerospace 2018, 5, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.-T.; Yuan, L.; Guan, Q.; Liang, G.; Gu, A. Biobased Heat Resistant Epoxy Resin with Extremely High Biomass Content from 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid and Eugenol. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 7003–7011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillol, S. Cardanol: A promising building block for biobased polymers and additives. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2018, 14, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darroman, E.; Durand, N.; Boutevin, B.; Caillol, S. New cardanol/sucrose epoxy blends for biobased coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2015, 83, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadarola, A.; Di Matteo, P.; Ciardiello, R.; Gazza, F.; Lambertini, V.G.; Brunella, V.; Paolino, D.S. Mechanical Characterization of Cardanol Bio-Based Epoxy Resin Blends: Effect of Different Bio-Contents. Polymers 2025, 17, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Weng, Z.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, C.; Jian, X. Magnolol-based bio-epoxy resin with acceptable glass transition temperature, processability and flame retardancy. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 387, 124115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, M.; Huang, Y.; Hu, M.; Li, L. Facile preparation of magnolol-based epoxy resin with intrinsic flame retardancy, high rigidity and hydrophobicity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 192, 116124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Weng, Z.; Qi, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, S.; Wei, Z.; Chen, Y.; Jian, X. Achieving higher performances without an external curing agent in natural magnolol-based epoxy resin. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 2195–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Yang, D.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, B.; Xiang, W.; Sun, Z.; Xu, R.; Zhang, M.; Hu, W. Performance of UV curable lignin based epoxy acrylate coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 116, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Leng, W.; Nayanathara, R.M.O.; Caldona, E.B.; Liu, L.; Chen, L.; Advincula, R.C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X. Anticorrosive epoxy coatings from direct epoxidation of bioethanol fractionated lignin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 221, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, X.; Cui, X.; Al-Haimi, A.; Wang, X.; Liang, H.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Z. Fully bio-based epoxy resins from lignin and epoxidized soybean oil: Rigid-flexible, tunable properties and high lignin content. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254, 127760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paraskar, P.M.; Prabhudesai, M.S.; Hatkar, V.M.; Kulkarni, R.D. Vegetable oil based polyurethane coatings—A sustainable approach: A review. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 156, 106267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, C.K.; Rajput, S.D.; Marathe, R.J.; Kulkarni, R.D.; Phadnis, H.; Sohn, D.; Mahulikar, P.P.; Gite, V.V. Synthesis of bio-based polyurethane coatings from vegetable oil and dicarboxylic acids. Prog. Org. Coat. 2017, 106, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormaiztegui, M.E.V.; Daga, B.; Aranguren, M.I.; Mucci, V. Bio-based waterborne polyurethanes reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals as coating films. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 144, 105649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinejad, M.; Henry, C.; Nikafshar, S.; Gondaliya, A.; Bagheri, S.; Chen, N.; Singh, S.K.; Hodge, D.B.; Nejad, M. Lignin-Based Polyurethanes: Opportunities for Bio-Based Foams, Elastomers, Coatings and Adhesives. Polymers 2019, 11, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haro, J.C.; Allegretti, C.; Smit, A.T.; Turri, S.; D’Arrigo, P.; Griffini, G. Biobased Polyurethane Coatings with High Biomass Content: Tailored Properties by Lignin Selection. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 11700–11711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čuk, N.; Steinbücher, M.; Vidmar, N.; Ocepek, M.; Venturini, P. Fully Bio-Based and Solvent-Free Polyester Polyol for Two-Component Polyurethane Coatings. Coatings 2023, 13, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Webster, D.C. New biobased high functionality polyols and their use in polyurethane coatings. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.M.; Jirimali, H.D.; Gite, V.V.; Jagtap, R.N. Synthesis and performance of bio-based hyperbranched polyol in polyurethane coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 149, 105895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poussard, L.; Lazko, J.; Mariage, J.; Raquez, J.M.; Dubois, P. Biobased waterborne polyurethanes for coating applications: How fully biobased polyols may improve the coating properties. Prog. Org. Coat. 2016, 97, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.A.R.; Marques, A.C.; dos Santos, R.G.; Shakoor, R.A.; Taryba, M.; Montemor, M.F. Development of BioPolyurethane Coatings from Biomass-Derived Alkylphenol Polyols—A Green Alternative. Polymers 2023, 15, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, H.; Iqbal, S.; Irfan, M.; Darda, A.; Rawat, N.K. A review on the production, properties and applications of non-isocyanate polyurethane: A greener perspective. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 154, 106124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Gu, L.; Liu, S.; Su, Y.; Zhou, Q. Non-isocyanate polyurethane from bio-based feedstocks and their interface applications. RSC Appl. Interfaces 2025, 2, 1123–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesiobędzka, J.; Datta, J. Challenges and recent advances in bio-based isocyanate production. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 2482–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichon, E.; De Smet, D.; Rouster, P.; Freulings, K.; Pich, A.; Bernaerts, K.V. Bio-based non-isocyanate polyurethane(urea) waterborne dispersions for water resistant textile coatings. Mater. Today Chem. 2023, 34, 101822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareanshahraki, F.; Asemani, H.R.; Skuza, J.; Mannari, V. Synthesis of non-isocyanate polyurethanes and their application in radiation-curable aerospace coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 138, 105394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, X.; Wu, Z.; Qu, J. Synthesis and properties of poly(dimethylsiloxane)-based non-isocyanate polyurethanes coatings with good anti-smudge properties. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 163, 106690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, G.; Pan, J.; Ma, C.; Zhang, G. Non-isocyanate Polyurethane Coating with High Hardness, Superior Flexibility, and Strong Substrate Adhesion. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 5998–6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizman, C.; KaçAkgil, E.C. Alkyd resins produced from bio-based resources for more sustainable and environmentally friendly coating applications. Turk. J. Chem. 2023, 47, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Coombes, A.; Rathbone, M.J.; Gan, S.N. Synthesis and characterization of novel biocompatible palm oil-based alkyds. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2015, 118, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Fearon, O.; Agustin, M.; Alonso, S.; Balda, E.C.; Franco, S.; Kalliola, A. Fractionation of Kraft Lignin for Production of Alkyd Resins for Biobased Coatings with Oxidized Lignin Dispersants as a Co-Product. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 46276–46292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulsbosch, J.; Claes, L.; Jonckheere, D.; Mestach, D.; De Vos, D.E. Synthesis and characterisation of alkyd resins with glutamic acid-based monomers. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 8220–8227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janesch, J.; Bacher, M.; Padhi, S.; Rosenau, T.; Gindl-Altmutter, W.; Hansmann, C. Biobased Alkyd Resins from Plant Oil and Furan-2,5-dicarboxylic Acid. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 17625–17632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otabor, G.O.; Ifijen, I.H.; Mohammed, F.U.; Aigbodion, A.I.; Ikhuoria, E.U. Alkyd resin from rubber seed oil/linseed oil blend: A comparative study of the physiochemical properties. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samyn, P.; Bosmans, J.; Cosemans, P. Comparative study on mechanical performance of photocurable acrylate coatings with bio-based versus fossil-based components. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 104002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandid, A.; Esteban, J.; D’Agostino, C.; Spallina, V. Process assessment of renewable-based acrylic acid production from glycerol valorisation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansod, Y.; Jafari, M.; Pawanipagar, P.; Ghasemzadeh, K.; Spallina, V.; D’Agostino, C. Techno-economic assessment of bio-based routes for acrylic acid production. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 10612–10632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Yamada, Y.; Sato, S.; Ueda, W. Glycerol as a potential renewable raw material for acrylic acid production. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 3186–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brobbey, M.S.; Louw, J.; Görgens, J.F. Biobased acrylic acid production in a sugarcane biorefinery: A techno-economic assessment using lactic acid, 3-hydroxypropionic acid and glycerol as intermediates. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 193, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolář, M.; Machotová, J.; Hájek, M.; Honzíček, J.; Hájek, T.; Podzimek, Š. Application of Vegetable Oil-Based Monomers in the Synthesis of Acrylic Latexes via Emulsion Polymerization. Coatings 2023, 13, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, D.; Tade, R.; Sabnis, A.S. Development of bio-based polyester-urethane-acrylate (PUA) from citric acid for UV-curable coatings. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2023, 20, 1083–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potdar, S.; Maiti, S.; Ukirade, A.; Jagtap, R. Bio-based interior UV-curable coating designed for wood substrates. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2024, 22, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, X.; Liu, R.; Liu, X.; Liu, J. Highly functional bio-based acrylates with a hard core and soft arms: From synthesis to enhancement of an acrylated epoxidized soybean oil-based UV-curable coating. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 134, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, R.; Luo, J. Synthesis of acrylated tannic acid as bio-based adhesion promoter in UV-curable coating with improved corrosion resistance. Colloids Surf. A 2022, 644, 128834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.; Sun, X.S. Cardanol modified fatty acids from camelina oils for flexible bio-based acrylates coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 123, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demchuk, Z.; Kirianchuk, V.; Kingsley, K.; Voronov, S.; Voronov, A. Plasticizing and Hydrophobizing Effect of Plant OilBased Acrylic Monomers in Latex Copolymers with Styrene and Methyl Methacrylate. Int. J. Theor. Appl. Nanotechnol. 2018, 6, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebotar, A.; Shymborska, Y.; Stetsyshyn, Y.; Awsiuk, K.; Raczkowska, J.; Bernasik, A.; Donchak, V.; Kostruba, A.; Budkowski, A. Grafted coatings of poly(castor seed oil-derived monomer) exhibiting unexpected thermo- and pH-responsive behavior: A new concept of the transition mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 523, 168867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczkowska, J.; Stetsyshyn, Y.; Awsiuk, K.; Lekka, M.; Marzec, M.; Harhay, K.; Ohar, H.; Ostapiv, D.; Sharan, M.; Yaremchuk, I.; et al. Temperature-responsive grafted polymer brushes obtained from renewable sources with potential application as substrates for tissue engineering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 407, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebotar, A.; Domnich, B.; Panchenko, Y.; Donchak, V.; Stetsyshyn, Y.; Voronov, A. Thermal behavior of polymers and copolymers based on plant oils with differing saturated and monounsaturated content. Polym. Int. 2024, 74, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venil, C.K.; Dufossé, L.; Renuka Devi, P. Bacterial Pigments: Sustainable Compounds with Market Potential for Pharma and Food Industry. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, L.S.; Krishnan, R.; Begum, S.; Nath, D.; Mohanty, A.; Misra, M.; Kumar, S. Curcumin as Bioactive Agent in Active and Intelligent Food Packaging Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Z.; Ju, H.; Xu, G.S.; Wu, Y.C.; Chen, X.; Li, H.J. Recent development of carrier materials in anthocyanins encapsulation applications: A comprehensive literature review. Food Chem. 2024, 439, 138104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Xiong, F.; Wang, H.; Qing, Y.; Chu, F.; Wu, Y. Tailorable and scalable production of eco-friendly lignin micro-nanospheres and their application in functional superhydrophobic coating. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 457, 141309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Caldona, E.B.; Leng, W.; Street, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Z. Anticorrosive epoxy coatings containing ultrafine bamboo char and zinc particles. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Xia, H.; Tang, K.; Zhou, Y. Plasticizers Derived from Biomass Resources: A Short Review. Polymers 2018, 10, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchant, R.; Banat, I.M. Biosurfactants: A sustainable replacement for chemical surfactants? Biotechnol. Lett 2012, 34, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.S.M.; Silva, V.M.T.M.; Rodrigues, A.E. Ethyl lactate as a solvent: Properties, applications and production processes—A review. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Jerome, F. Bio-based solvents: An emerging generation of fluids for the design of eco-efficient processes in catalysis and organic chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 9550–9570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilon, L.; Day, D.; Maslen, H.; Stevens, O.P.J.; Carslaw, N.; Shaw, D.R.; Sneddon, H.F. Development of a solvent sustainability guide for the paints and coatings industry. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 9697–9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Raw Material Category | Representative Source | Core Advantage | Inherent Defect | Typical Coating Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant source | Plant oils (linseed oil, soybean oil, canola oil, castor oil et al.) Plant phenols (eugenol, guaiacol, cardanol, vanillin, magnolol, gallic acid, protocatechuic acid, lignin) Polysaccharides (starch, cellulose, pectin, inulin, glycogen, sorbitol, isosorbitol, hyaluronic acid, chondroitin sulfate, xanthan gum, dextran, lentinan, ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide, agar, sodium alginate) Rosin (turpentine, terpenes, terpineol, resin acids) Biological acids (itaconic acid, citric acid, amino acid, rosin acid, lactic acid, oxalic acid, phytic acid, tartaric acid, fatty acids) Bio-based non-isocyanate polyurethane (epoxidized plant oils, sugar derivatives, lignocellulose derivatives) | Abundant sources; widely present in nature; true renewability; low toxicity/VOC potential for any sources. | Plant oils: oxidation instability during storage, affecting long-term performance. Plant phenols: complex extraction processes lead to high costs. Polysaccharides: poor water resistance of films formed. Biological acids: some have strong acidity, potentially corroding substrates. Bio-based non-isocyanate polyurethane: harsh synthesis conditions and low reaction efficiency. Performance variability: chemical composition can vary with crop, season, and climate, leading to batch-to-batch inconsistencies. Compatibility issues: some bio-based polymers may have poor compatibility with traditional petroleum-based resins or additives. | Alkyd coatings, epoxy coatings, polyurethane coatings, acrylic coatings, benzoxazine coatings plant acid-modified functional coatings |

| Animal source | Chitin, chitosan, collagen, gelatin, shellac, beeswax | Strong antibacterial property; good biocompatibility; excellent film-forming ability; excellent adhesion and film toughness for some (e.g., collagen, gelatin). | Limited by animal breeding, supply stability is challenged. Beeswax: low melting point, prone to softening at high temperatures. Long microbial fermentation cycle and strict control requirements for fermentation conditions (temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, etc.), making large-scale production costly. Some microbial-derived polymers: insufficient mechanical strength for high-strength coating applications. Ethical concerns and market acceptance issues related to animal-derived ingredients. Potential allergenicity for certain animal-derived proteins (e.g., shellac, collagen). | Shellac-based protective coatings, chitosan-modified anticorrosive coatings, beeswax-based wood coatings |

| Microbial source | Chlorella, spirulina, Dunaliella, Haematococcus pluvialis, xanthan gum, gellan gum, bacterial cellulose, polyhydroxyalkanoates | Precise regulation of structure; excellent weather resistance; biodegradable; environmental friendliness. Non-competition with arable land: cultivation in fermenters does not require farmland. Utilization of waste streams: many microbes can use industrial/agricultural waste as culture media. | High production cost associated with fermentation and downstream processing. Relatively low yield for some target polymers. | Xanthan gum-based thickened coatings, polyhydroxyalkanoates-based biodegradable coatings, bacterial cellulose-based high-performance coatings polylactic acid (PLA)-based coatings |

| Conversion Strategy | Advantages | Limitations | Application Scope | Representative Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct utilization | Simple process, low cost; retains natural properties of biomass | Poor performance (e.g., long drying time of tung oil); limited application | Wood protection, fruit preservation coatings | Tung oil wood coating, beeswax fruit coating | [46,53] |

| Physical blending | Low research and development cost; flexible property adjustment; compatible with traditional resins | Poor miscibility; limited performance improvement | Anticorrosion, flame-retardant coatings | Cardanol/DGEBA blend anticorrosion coating | [58,60] |

| Chemical modification | Precise molecular regulation; significant performance enhancement | Complex process; high cost; potential environmental impact of chemical reagents | High-performance coatings (e.g., high Tg, corrosion resistance) | Epoxidized plant oil epoxy resin, lignin-modified acrylic resin | [67,85] |

| Biosynthesis | Mild reaction conditions; high specificity; low environmental footprint | Long reaction time; high enzyme cost; difficulty in large-scale production | Biodegradable coatings, specialty coatings | Enzymatically synthesized polyhydroxy-alkanoate (PHA) coatings | [99,100] |

| Coating Type | Key Advantages | Core Limitation and Liabilities | Typical Applications | Technological Maturity | Relative Cost and Feasibility | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-based epoxy | Excellent adhesion and chemical resistance High mechanical strength and hardness Good thermal stability (especially with phenolics) good corrosion protection | Low Tg and flexibility (plant oil-based) Complex extraction (plant phenol-based) Often requires petro-based curing agents Brittleness if not properly formulated | Marine and automotive anticorrosion coatings High-performance industrial floors Electronic encapsulants | Commercial (growing) | Medium to high Plant oils: cost-competitive Plant phenols: more expensive | [105,111,119] |

| Bio-based polyurethane (PU) | Superior abrasion resistance and toughness Excellent flexibility and low-temperature performance NIPUs avoid toxic isocyanates | High cost and toxicity of isocyanates (conventional route) Poor hydrolytic stability (some polyols) NIPUs: slower curing and lower performance than conventional PUs | Furniture and wood finishes Automotive interior coatings Textile and leather coatings Aerospace coatings | Commercial (mature for polyols) | Medium to high Bio-polyols: competitive Bio-isocyanates/NIPUs: premium | [128,136,137] |

| Bio-based alkyd | Low cost and easy application Good penetration and wetting on substrates Autoxidative curing (air-drying) Proven technology, easy to retrofit | High VOC (in solvent-borne forms) Slow drying compared to acrylics/PUs Susceptible to yellowing and oxidative degradation Limited chemical/alkali resistance | Architectural and decorative paints Primer and undercoats for metal/wood Heavy-duty maintenance coatings | Commercial (mature) | Low to medium Most cost-effective bio-based option | [139,142,143] |

| Bio-based acrylic | Outstanding UV and weather resistance High clarity and color retention Fast curing (especially UV-curable) Good mechanical property balance | High rigidity and brittleness (if not modified) Lower chemical resistance than epoxies/PUs Reliance on fossil-based acrylic acid (partially) | Clear varnishes for wood and plastic Overprint varnishes and inks Architectural and automotive topcoats | Research and development to commercial (growing fast) | Medium Bio-acrylic acid: currently premium | [150,151,154] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xia, L.; Gui, T.; Wang, J.; Tian, H.; Wang, Y.; Ning, L.; Wu, L. Bio-Based Coatings: Progress, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Polymers 2025, 17, 3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243266

Xia L, Gui T, Wang J, Tian H, Wang Y, Ning L, Wu L. Bio-Based Coatings: Progress, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243266

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Lijian, Taijiang Gui, Junjun Wang, Haoyuan Tian, Yue Wang, Liang Ning, and Lianfeng Wu. 2025. "Bio-Based Coatings: Progress, Challenges and Future Perspectives" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243266

APA StyleXia, L., Gui, T., Wang, J., Tian, H., Wang, Y., Ning, L., & Wu, L. (2025). Bio-Based Coatings: Progress, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Polymers, 17(24), 3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243266