The Effect of Organic Loading and Mode of Operation in a Sequencing Batch Reactor Producing PHAs from a Medium Corresponding to Condensate from Food Waste Drying

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

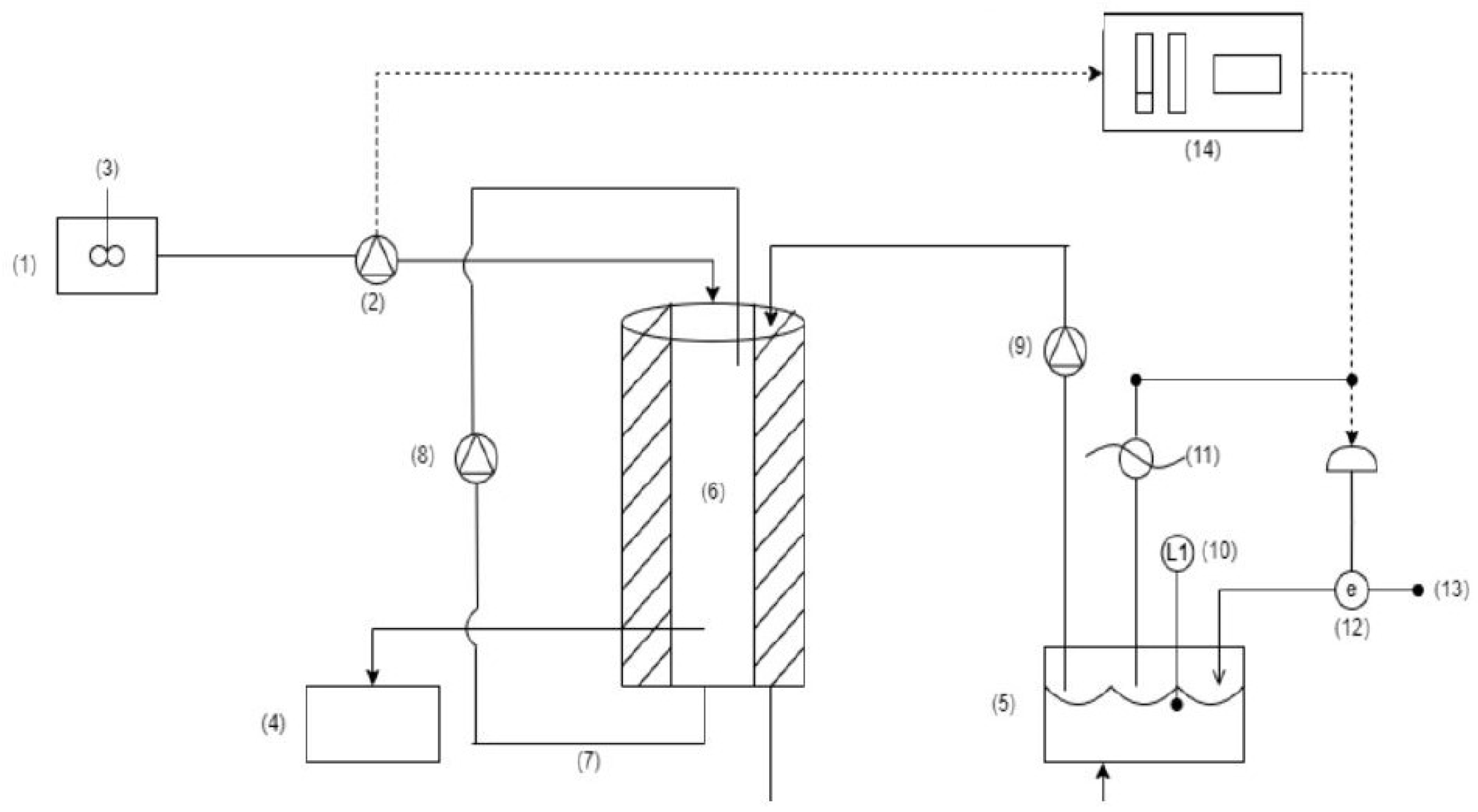

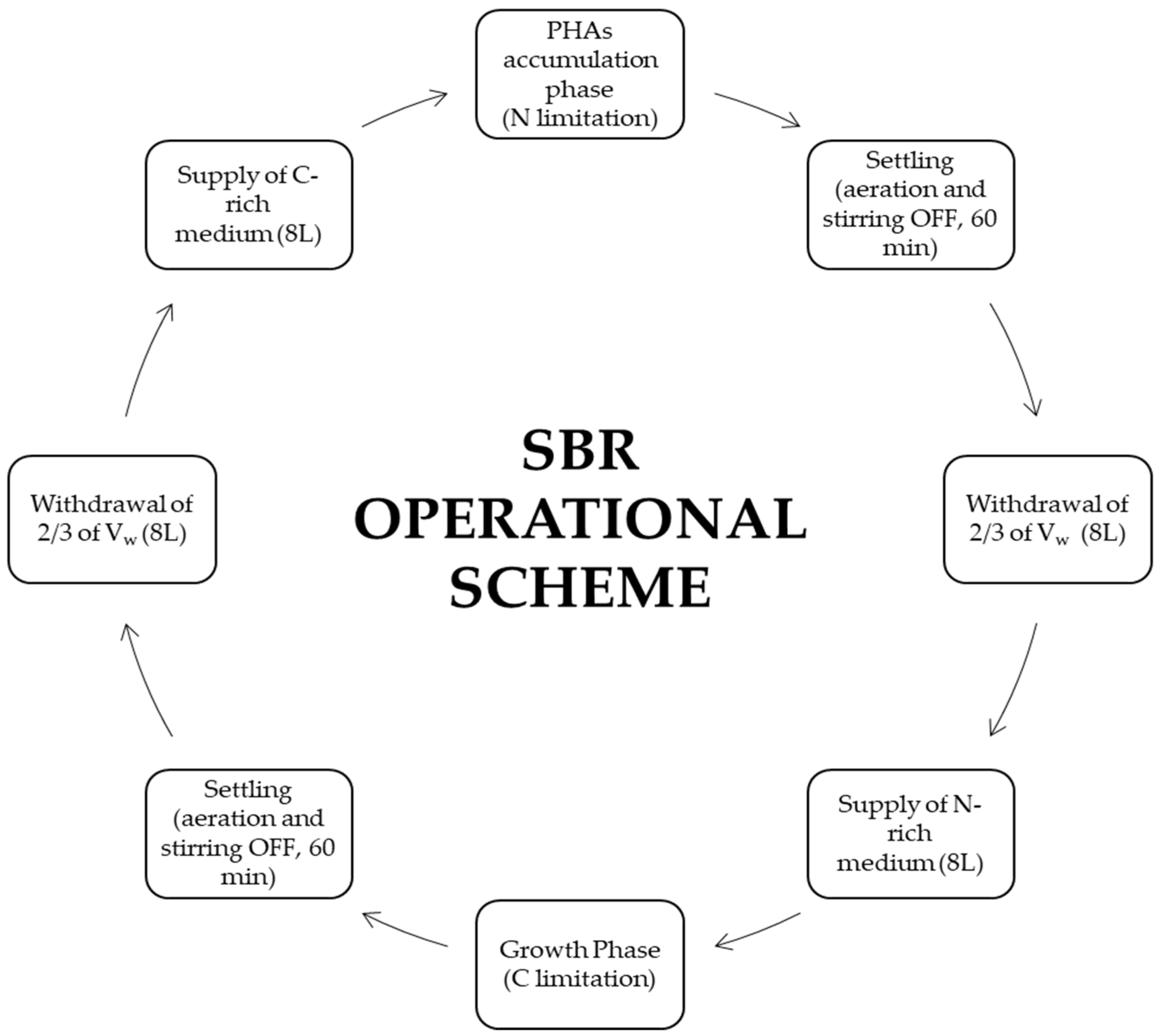

2.1. Experimental Setup and Operational Parameters

2.2. Analytical Techniques

3. Results and Discussion

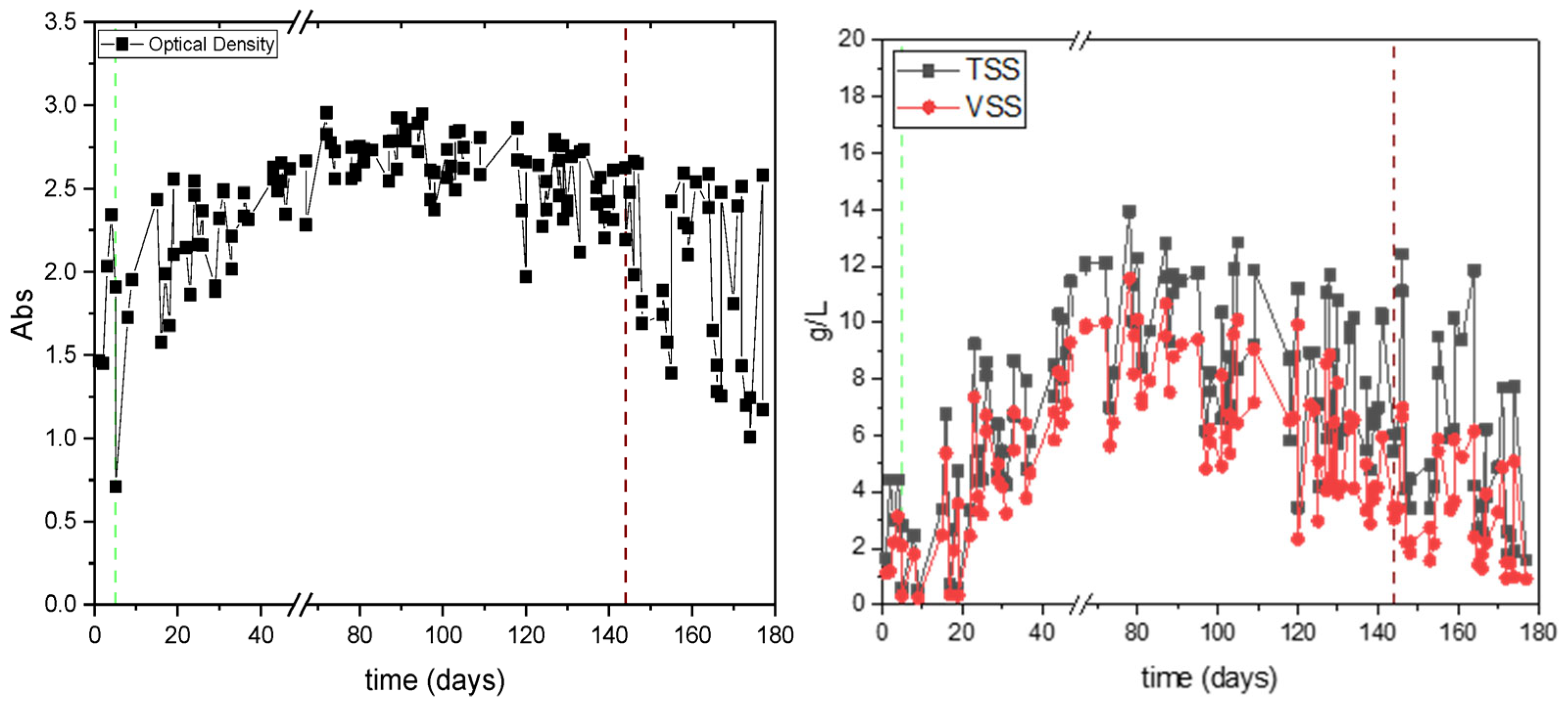

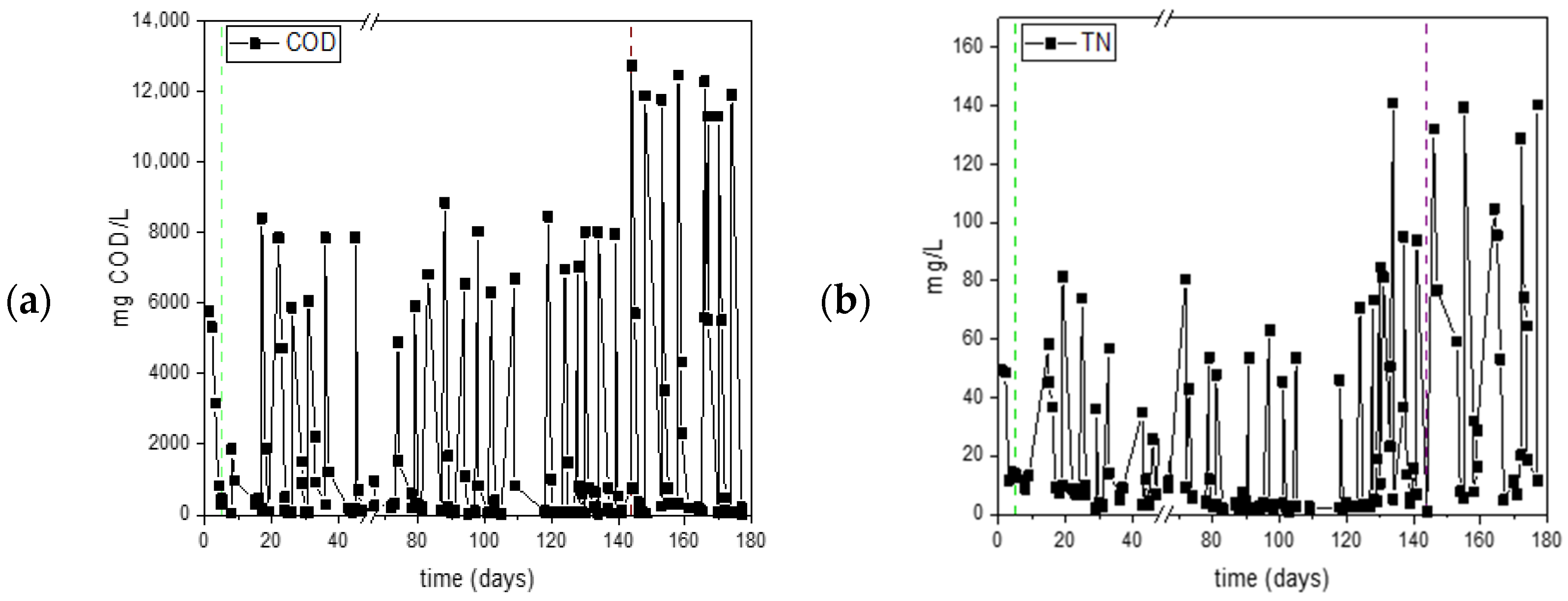

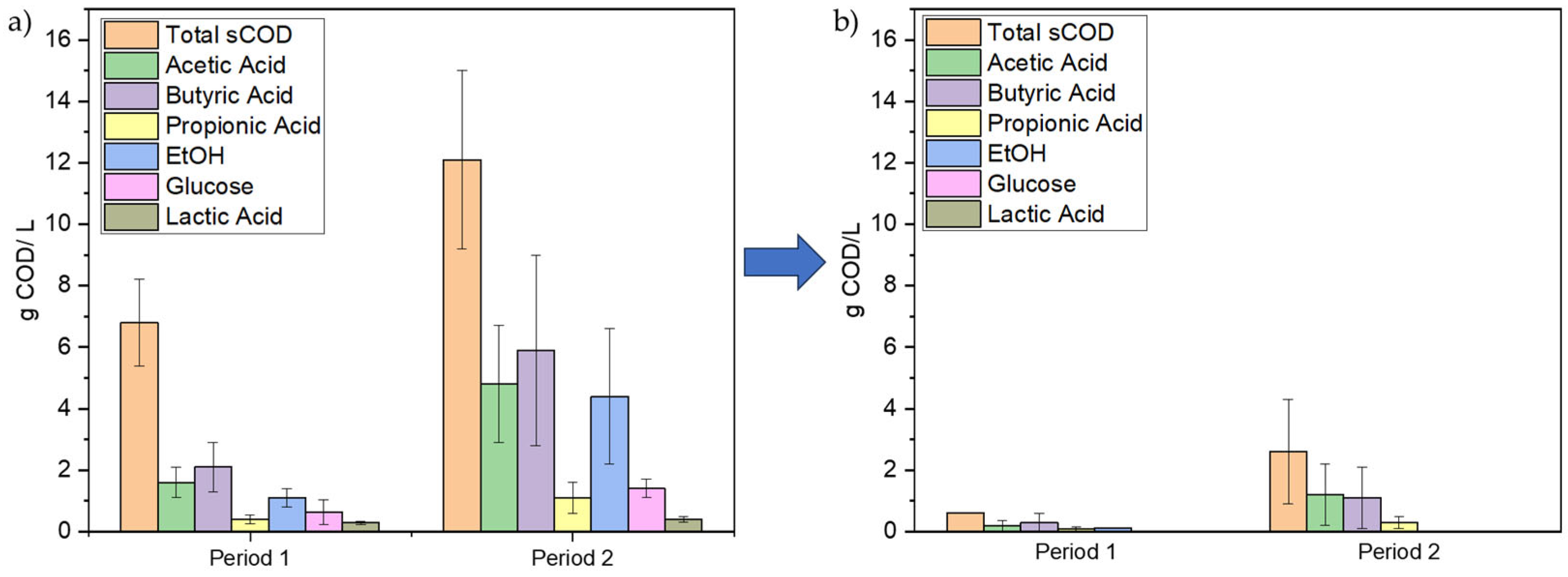

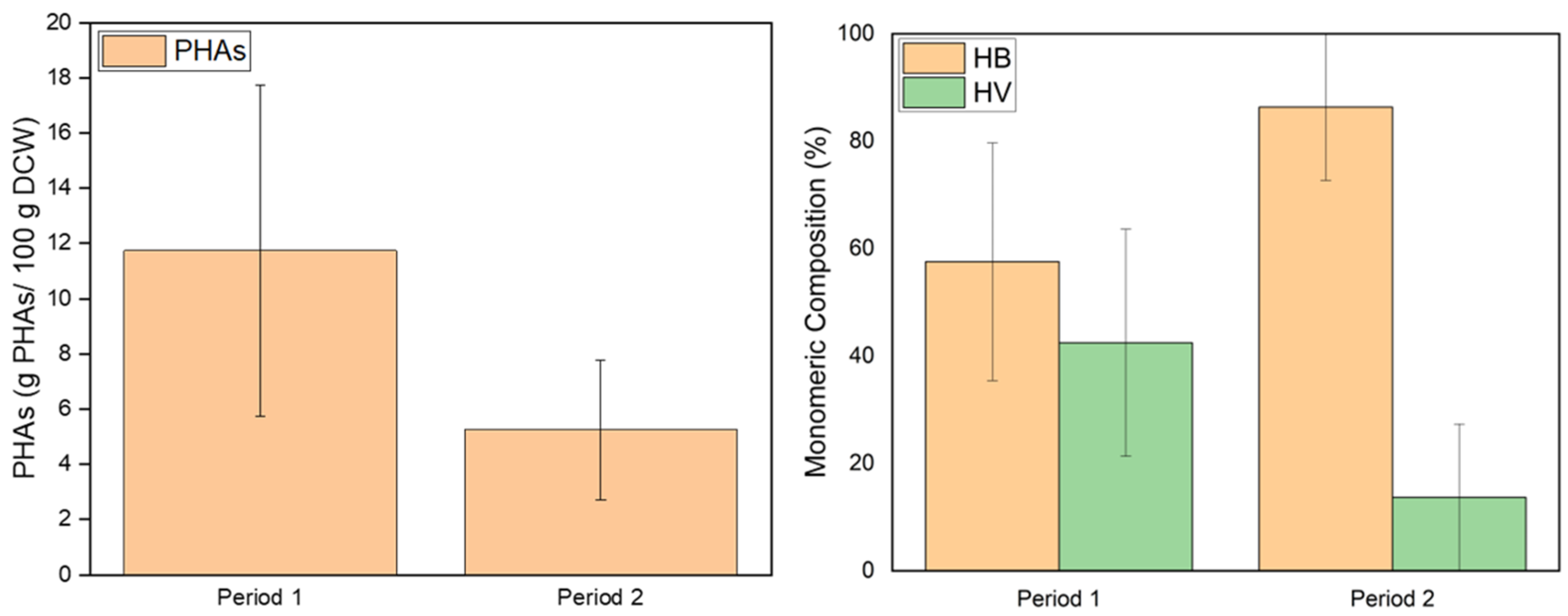

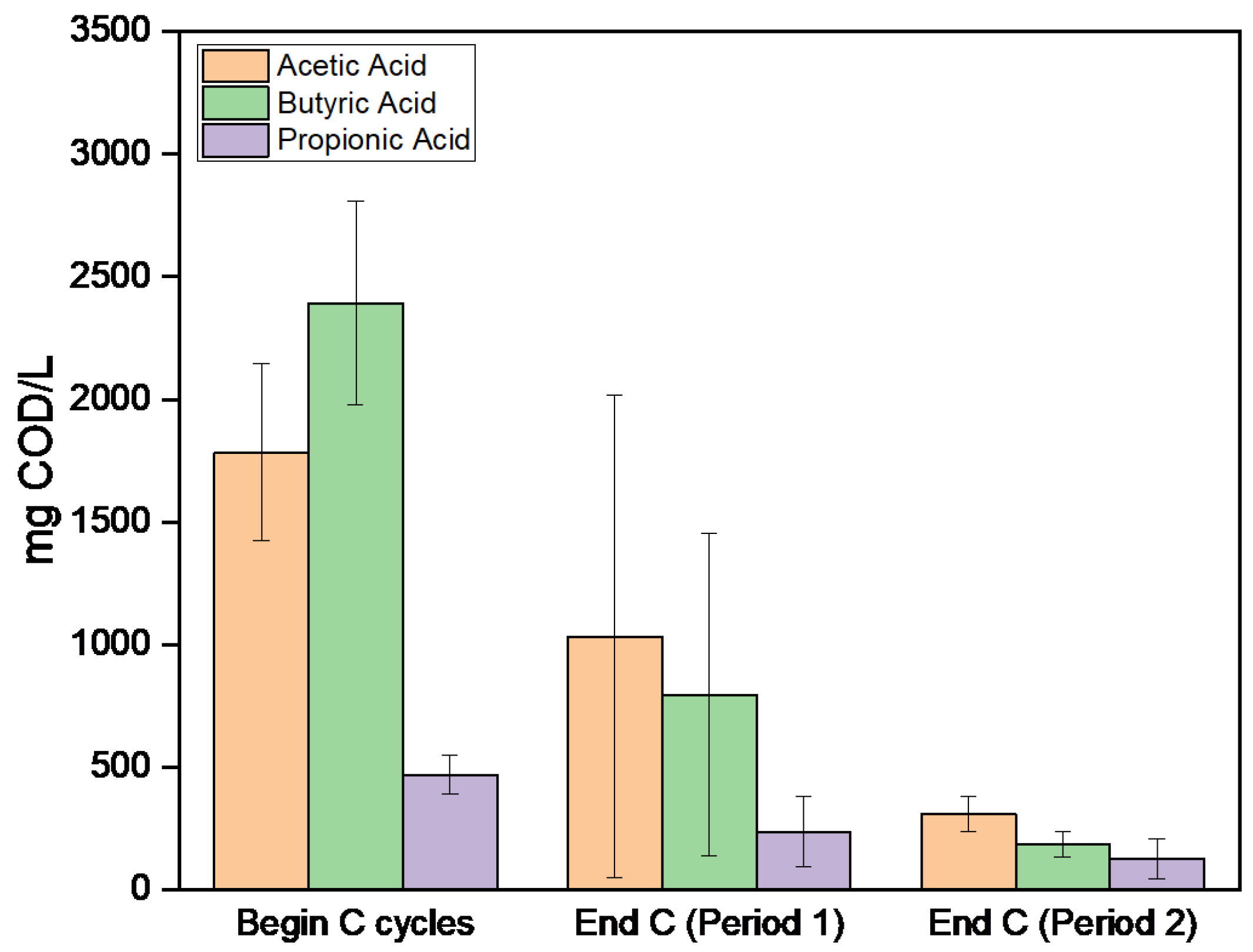

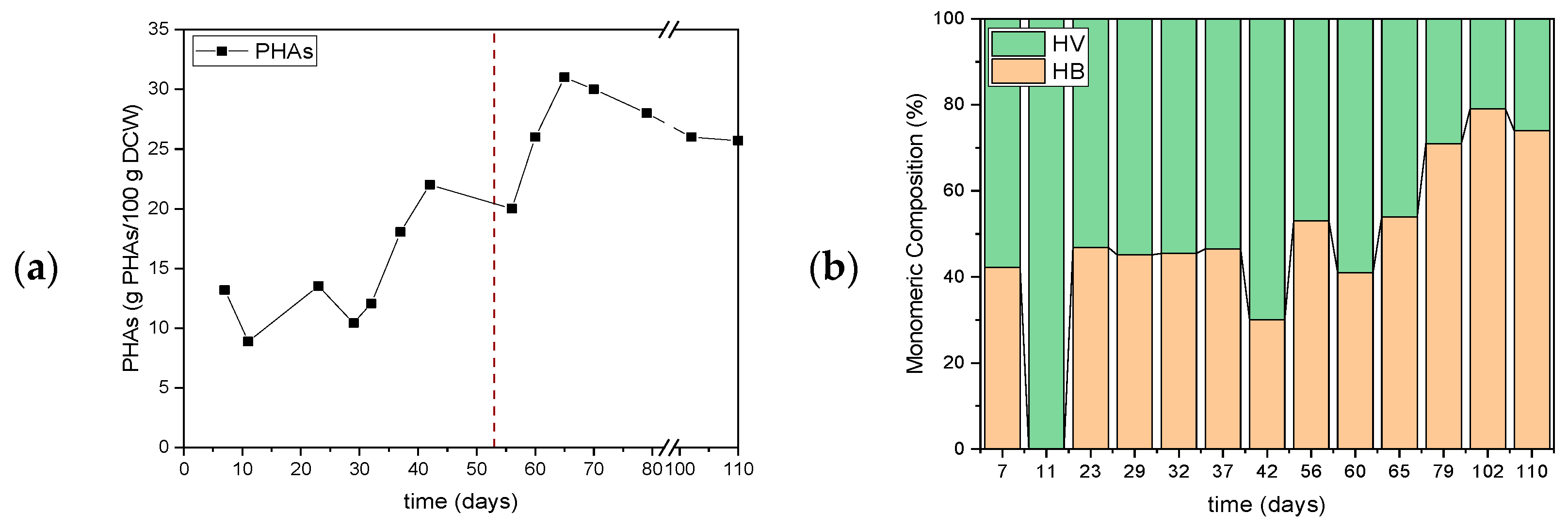

3.1. First Set of Experiments for Assessing the Effect of Organic Load

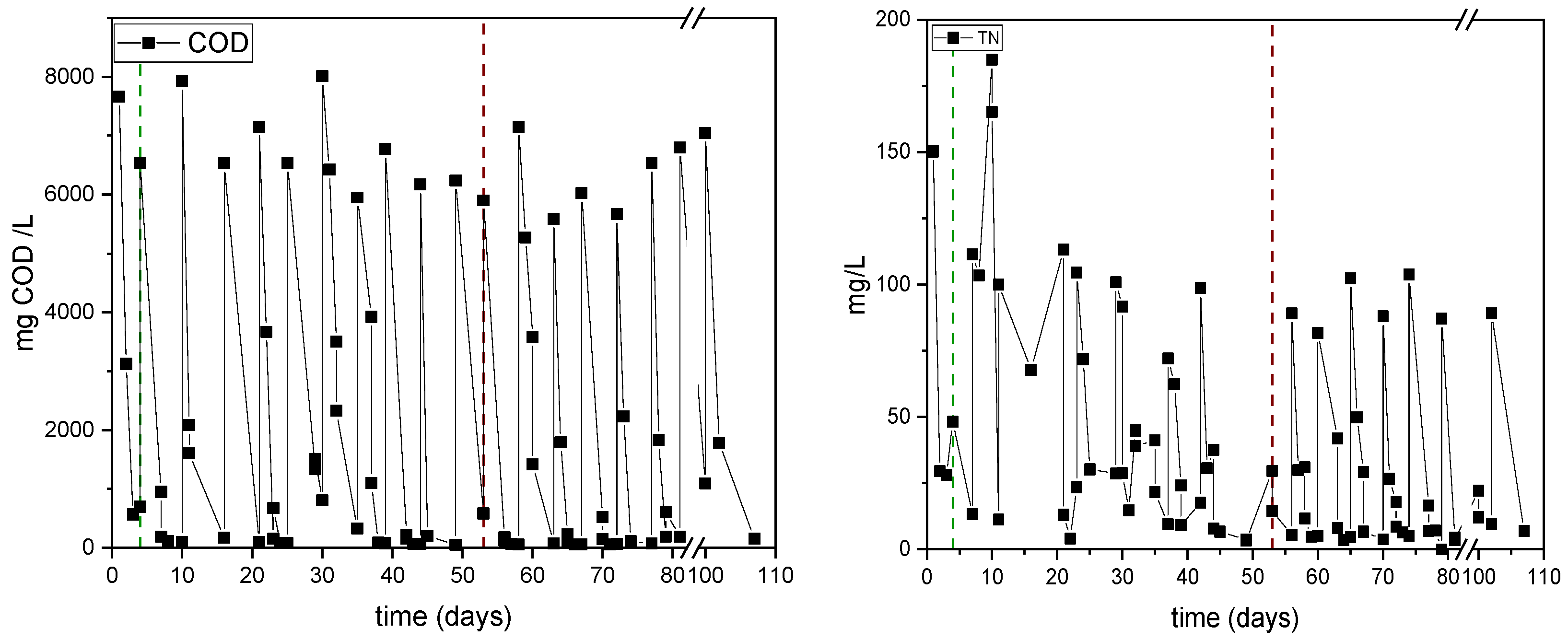

3.2. Second Set of Experiments for Assessing the Impact of Including or Not Including a Settling Phase

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PHA | Polyhydroxyalkanoates |

| SBR | Sequencing Batch Reactor |

| 3HB | 3-R-hydroxybutyrate |

| 3HV | 3-R-hydroxyvalerate |

| PHBV | Poly (3-R-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-R-hydroxyvalerate) |

| MT | Metric ton |

| MMC | Mixed microbial cultures |

| FAO | Food and Agricultural Organization |

| DO | Dissolved Oxygen |

| sCOD | Soluble Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| TSS | Total Suspended Solids |

| VSS | Volatile Suspended Solids |

| VFAs | Volatile Fatty Acids |

| HPLC | High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| DFR | Draw and Fill Reactor |

| PHB | Polyhydroxybutyrate |

| PHV | Polyhydroxyvalerate |

References

- Swetha, T.A.; Bora, A.; Ananthy, V.; Ponnuchamy, K.; Muthusamy, G.; Arun, A. A review of bioplastics as an alternative to petrochemical plastics: Its types, structure, characteristics, degradation, standards, and feedstocks. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35, e6482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folino, A.; Karageorgiou, A.; Calabrò, P.S.; Komilis, D. Biodegradation of wasted bioplastics in natural and industrial environments: A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, P.D.; Kim, S.; Sarkar, B.; Oleszczuk, P.; Sang, M.K.; Haque, N.; Ahn, J.H.; Bank, M.S.; Ok, Y.S. Effects of microplastics on the terrestrial environment: A critical review. Environ. Res. 2022, 209, 112734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, S.; Gautam, A.; Pawaday, J.; Kanzariya, R.K.; Yao, Z. Current Status and Challenges in the Commercial Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoate-Based Bioplastic: A Review. Processes 2024, 12, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narancic, T.; Cerrone, F.; Beagan, N.; O’connor, K.E. Recent advances in bioplastics: Application and biodegradation. Polymers 2020, 12, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafim, L.S.; Lemos, P.C.; Albuquerque, M.G.E.; Reis, M.A.M. Strategies for PHA production by mixed cultures and renewable waste materials. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 81, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, D.; Proença, D.N.; Morais, P.V. The Role of Bacterial Polyhydroalkanoate (PHA) in a Sustainable Future: A Review on the Biological Diversity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-Alonso, Á.; Pei, R.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.; Kleerebezem, R.; Werker, A. Scaling-up microbial community-based polyhydroxyalkanoate production: Status and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 327, 124790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntaikou, I.; Koumelis, I.; Tsitsilianis, C.; Parthenios, J.; Lyberatos, G. Comparison of yields and properties of microbial polyhydroxyalkanoates generated from waste glycerol based substrates. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Perez, S.; Serrano, A.; Pantión, A.A.; Alonso-Fariñas, B. Challenges of scaling-up PHA production from waste streams. A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 205, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamira-Algarra, B.; Garcia, J.; Gonzalez-Flo, E. Cyanobacteria microbiomes for bioplastic production: Critical review of key factors and challenges in scaling from laboratory to industry set-ups. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 422, 132231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Peng, L.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, D.; Ni, B.-J.; et al. Towards scaling-up implementation of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production from activated sludge: Progress and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakarika, M.; Matassa, S.; Carvajal-Arroyo, J.M.; Ganigué, R. Editorial: Microbial biorefineries for a more sustainable, circular economy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1512756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simona, C.; Laura, L.; Francesco, V.; Marianna, V.; Cristina, M.G.; Barbara, T.; Mauro, M.; Simona, R. Effect of the organic loading rate on the PHA-storing microbiome in sequencing batch reactors operated with uncoupled carbon and nitrogen feeding. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 825, 153995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, R.N.; Hassemer, G.d.S.; Steffens, J.; Junges, A.; Valduga, E. Recent updates to microbial production and recovery of polyhydroxyalkanoates. 3 Biotech 2023, 13, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, F.; Torres-Aravena, Á.; Pinto-Ibieta, F.; Campos, J.L.; Jeison, D. On-Line Control of Feast/Famine Cycles to Improve PHB Accumulation during Cultivation of Mixed Microbial Cultures in Sequential Batch Reactors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kora, E.; Antonopoulou, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Q.; Lyberatos, G.; Ntaikou, I. Investigating the efficiency of a two-stage anaerobic-aerobic process for the treatment of confectionery industry wastewaters with simultaneous production of biohydrogen and polyhydroxyalkanoates. Environ. Res. 2024, 248, 118526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kora, E.; Tsaousis, P.C.; Andrikopoulos, K.S.; Chasapis, C.T.; Voyiatzis, G.A.; Ntaikou, I.; Lyberatos, G. Production efficiency and properties of poly(3hydroxybutyrate-co-3hydroxyvalerate) generated via a robust bacterial consortium dominated by Zoogloea sp. using acidified discarded fruit juices as carbon source. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 226, 1500–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippou, K.; Bouzani, E.; Kora, E.; Ntaikou, I.; Papadopoulou, K.; Lyberatos, G. Polydroxyalkanoates Production from Simulated Food Waste Condensate Using Mixed Microbial Cultures. Polymers 2025, 17, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, F.; Karabegovic, L.; Majone, M.; Morgan-Sagastume, F.; Werker, A. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) storage within a mixed-culture biomass with simultaneous growth as a function of accumulation substrate nitrogen and phosphorus levels. Water Res. 2015, 77, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozejko-Ciesielska, J.; Szacherska, K.; Marciniak, P. Pseudomonas Species as Producers of Eco-friendly Polyhydroxyalkanoates. J. Polym. Environ. 2019, 27, 1151–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, M.; Muhr, A. Continuous production mode as a viable process-engineering tool for efficient poly(hydroxyalkanoate) (PHA) bio-production. Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q. 2014, 28, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamperidis, T.; Pandis, P.K.; Argirusis, C.; Lyberatos, G.; Tremouli, A. Effect of Food Waste Condensate Concentration on the Performance of Microbial Fuel Cells with Different Cathode Assemblies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellos, G.; Tremouli, A.; Kondylis, A.; Stamelou, A.; Lyberatos, G. Anaerobic Co-digestion of the Liquid Fraction of Food Waste with Waste Activated Sludge. Waste Biomass Valorization 2024, 15, 3339–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodger, B.B.; Andrew, E.D.; Eugene, R.W. (Eds.) Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Waste Water, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA; American Water Works Association: Denver, CO, USA; Water Environment Federation: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiskira, K.; Lymperopoulou, T.; Lourentzatos, I.; Tsakanika, L.-A.; Pavlopoulos, C.; Papadopoulou, K.; Ochsenkühn, K.-M.; Tsopelas, F.; Chatzitheodoridis, E.; Lyberatos, G.; et al. Bioleaching of Scandium from Bauxite Residue using Fungus Aspergillus Niger. Waste Biomass Valorization 2023, 14, 3377–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehmen, A.; Keller-Lehmann, B.; Zeng, R.J.; Yuan, Z.; Keller, J. Optimisation of poly-β-hydroxyalkanoate analysis using gas chromatography for enhanced biological phosphorus removal systems. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1070, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Zamora, U.; Fajardo-Ortiz, M.d.C.; Cuetero-Martínez, Y.; Tavera-Mejía, W.; Salazar-Peláez, M.L. Aerobic granulation for polyhydroxyalkanoates accumulation using organic waste leachates. J. Water Process. Eng. 2022, 51, 103464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, P.; Wei, Y.; Feng, Z.; Jia, Z.; Li, J.; Ren, L. Untargeted metabolomics elucidated biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoate by mixed microbial cultures from waste activated sludge under different pH values. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 331, 117300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, T.; Jing, H.; Shen, T.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Y. Performance of production of polyhydroxyalkanoates from food waste fermentation with Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 385, 129165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ga, E.; Mc, W. Modelling Inorganic Material in Activated Sludge Systems. Water SA 2004, 30, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heran, M.; Wisniewski, C.; Orantes, J.; Grasmick, A. Measurement of kinetic parameters in a submerged aerobic membrane bioreactor fed on acetate and operated without biomass discharge. Biochem. Eng. J. 2008, 38, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, N.; Benner, R. Bacterial release of dissolved organic matter during cell growth and decline: Molecular origin and composition. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2006, 51, 2170–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan-Sagastume, F.; Karlsson, A.; Johansson, P.; Pratt, S.; Boon, N.; Lant, P.; Werker, A. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates in open, mixed cultures from a waste sludge stream containing high levels of soluble organics, nitrogen and phosphorus. Water Res. 2010, 44, 5196–5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentino, F.; Morgan-Sagastume, F.; Campanari, S.; Villano, M.; Werker, A.; Majone, M. Carbon recovery from wastewater through bioconversion into biodegradable polymers. New Biotechnol. 2017, 37, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, M.; Albuquerque, M.; Villano, M.; Majone, M. Mixed Culture Processes for Polyhydroxyalkanoate Production from Agro-Industrial Surplus/Wastes as Feedstocks. In Comprehensive Biotechnology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagnoli, A.; Falcioni, S.; Touloupakis, E.; Pasciucco, F.; Pasciucco, E.; Michelotti, A.; Iannelli, R.; Pecorini, I. Influence of Aeration Rate on Uncoupled Fed Mixed Microbial Cultures for Polyhydroxybutyrate Production. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, M.G.E.; Carvalho, G.; Kragelund, C.; Silva, A.F.; Crespo, M.T.B.; Reis, M.A.M.; Nielsen, P.H. Link between microbial composition and carbon substrate-uptake preferences in a PHA-storing community. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yue, Z.-B.; Sheng, G.-P.; Yu, H.-Q. Kinetic analysis on the production of polyhydroxyalkanoates from volatile fatty acids by Cupriavidus necator with a consideration of substrate inhibition, cell growth, maintenance, and product formation. Biochem. Eng. J. 2010, 49, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Gao, A.X.; Liu, X.; Bai, Z.; Wang, P.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. Microbial conversion of ethanol to high-value products: Progress and challenges. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2024, 17, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W.; Yin, F.; Cao, Q.; Lian, T.; Dong, H. Polyhydroxyalkanoates production from lactic acid fermentation broth of agricultural waste without extra purification: The effect of concentrations. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 32, 103311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, L.D.D.; Sayavedra, S.M.; Rene, E.R. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production via resource recovery from industrial waste streams: A review of techniques and perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 331, 124985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel-Jarillo, G.; Carrera, J.; Eugenia Suárez-Ojeda, M. Enrichment of a mixed microbial culture for polyhydroxyalkanoates production: Effect of pH and N and P concentrations. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 583, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.; Matos, M.; Pereira, B.; Ralo, C.; Pequito, D.; Marques, N.; Carvalho, G.; Reis, M.A. An integrated process for mixed culture production of 3-hydroxyhexanoate-rich polyhydroxyalkanoates from fruit waste. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 131908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpurohit, H.; Eiteman, M.A. Nutrient-Limited Operational Strategies for the Microbial Production of Biochemicals. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourmentza, C.; Plácido, J.; Venetsaneas, N.; Burniol-Figols, A.; Varrone, C.; Gavala, H.N.; Reis, M.A.M. Recent advances and challenges towards sustainable polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, L.; Wen, Q.; Guo, Z. Efficient polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) accumulation by a new continuous feeding mode in three-stage mixed microbial culture (MMC) PHA production process. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 209, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experimental Period | Days | C/N Ratio | sCOD (g/L) | TN (g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch | 5 | 100 | ||

| 1 | 139 | 100 | 6.8 ± 1.4 | 0.06 ± 0.02 |

| 2 | 33 | 100 | 12.1 ± 2.9 | 0.12 ± 0.04 |

| Experimental Period | Days | sCOD (g/L) | TN (g/L) | Operation Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch | 4 | |||

| 1 | 49 | 6.5 ± 0.7 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | Settling phase |

| 2 | 57 | No Settling Phase |

| Experimental Period | Carbon Source | Mean COD Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acetate | 88.4 ± 29.8 |

| Butyrate | 80.5 ± 29.2 | |

| Propionate | 85.2 ± 30.8 | |

| EtOH | 89.0 ± 22.5 | |

| Glucose | 100 ± 20.4 | |

| Lactic Acid | 96.0 ± 20.4 | |

| 2 | Acetate | 77.8 ± 33.3 |

| Butyrate | 78.5 ± 43.6 | |

| Propionate | 83.6 ± 32.6 | |

| EtOH | 100 ± 3.7 | |

| Glucose | 100 ± 23.8 | |

| Lactic Acid | 100 ± 24.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Filippou, K.; Diamantopoulou, K.; Gatzia, M.; Ntaikou, I.; Papadopoulou, K.; Lyberatos, G. The Effect of Organic Loading and Mode of Operation in a Sequencing Batch Reactor Producing PHAs from a Medium Corresponding to Condensate from Food Waste Drying. Polymers 2025, 17, 3270. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243270

Filippou K, Diamantopoulou K, Gatzia M, Ntaikou I, Papadopoulou K, Lyberatos G. The Effect of Organic Loading and Mode of Operation in a Sequencing Batch Reactor Producing PHAs from a Medium Corresponding to Condensate from Food Waste Drying. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3270. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243270

Chicago/Turabian StyleFilippou, Konstantina, Konstantina Diamantopoulou, Melisa Gatzia, Ioanna Ntaikou, Konstantina Papadopoulou, and Gerasimos Lyberatos. 2025. "The Effect of Organic Loading and Mode of Operation in a Sequencing Batch Reactor Producing PHAs from a Medium Corresponding to Condensate from Food Waste Drying" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3270. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243270

APA StyleFilippou, K., Diamantopoulou, K., Gatzia, M., Ntaikou, I., Papadopoulou, K., & Lyberatos, G. (2025). The Effect of Organic Loading and Mode of Operation in a Sequencing Batch Reactor Producing PHAs from a Medium Corresponding to Condensate from Food Waste Drying. Polymers, 17(24), 3270. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243270