Synergetic Effect of Fullerene and Fullerenol/Carbon Nanotubes in Cellulose-Based Composites for Electromechanical and Thermoresistive Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

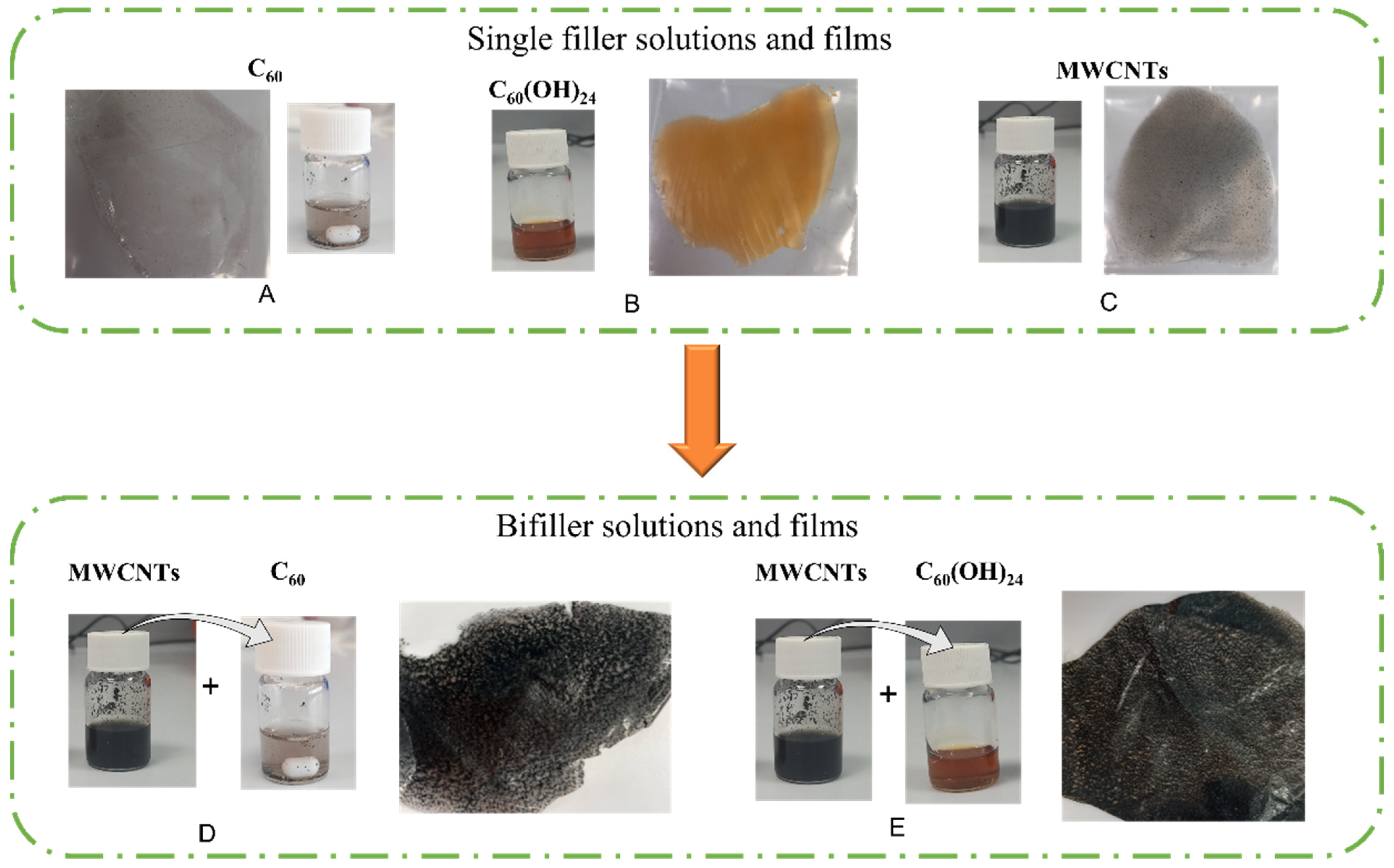

2.2. Nanocomposite Preparation

2.3. Physicochemical Characterization

2.4. Functional Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

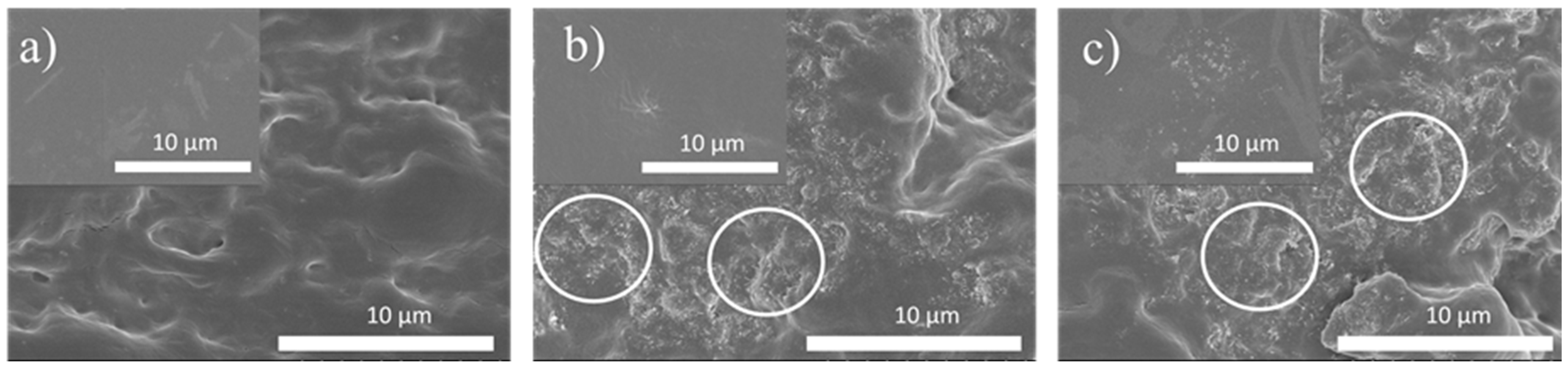

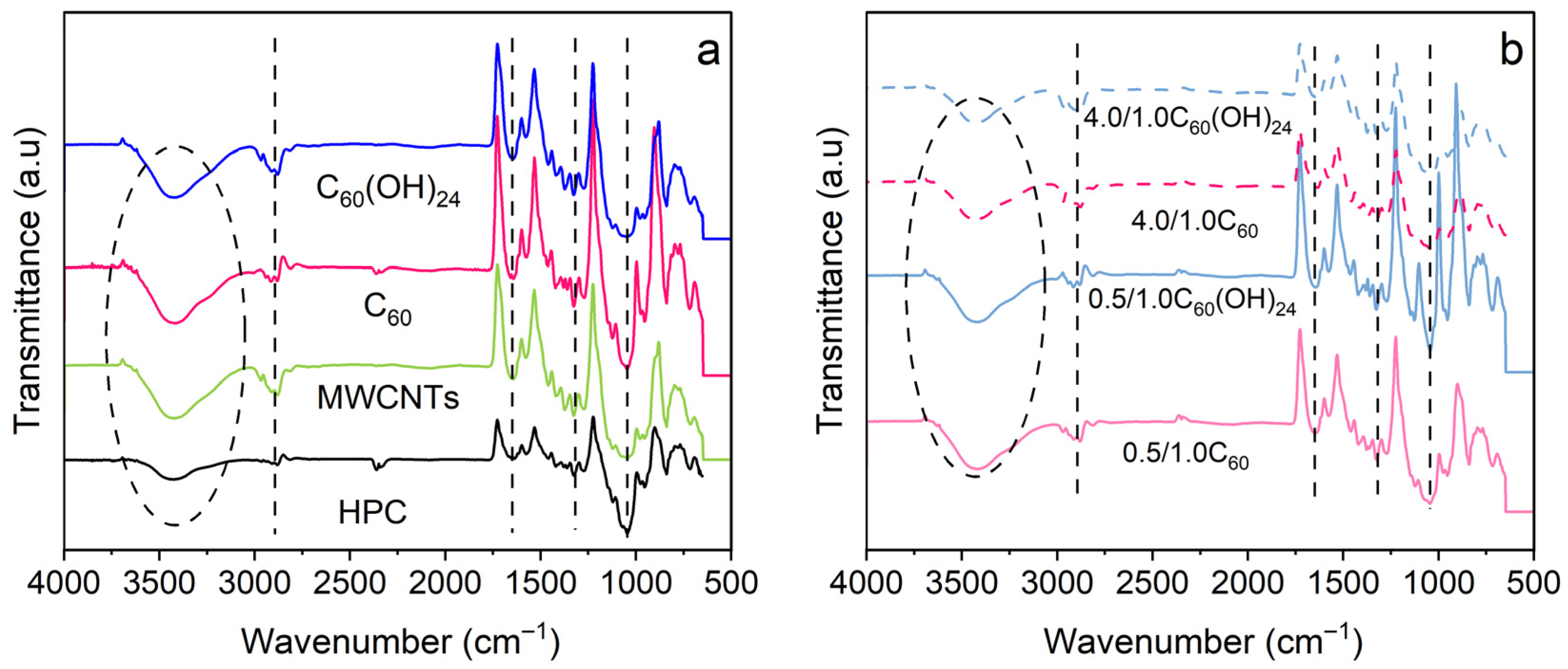

3.1. Morphological and Chemical Analysis

3.2. Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering

3.3. Thermal Properties

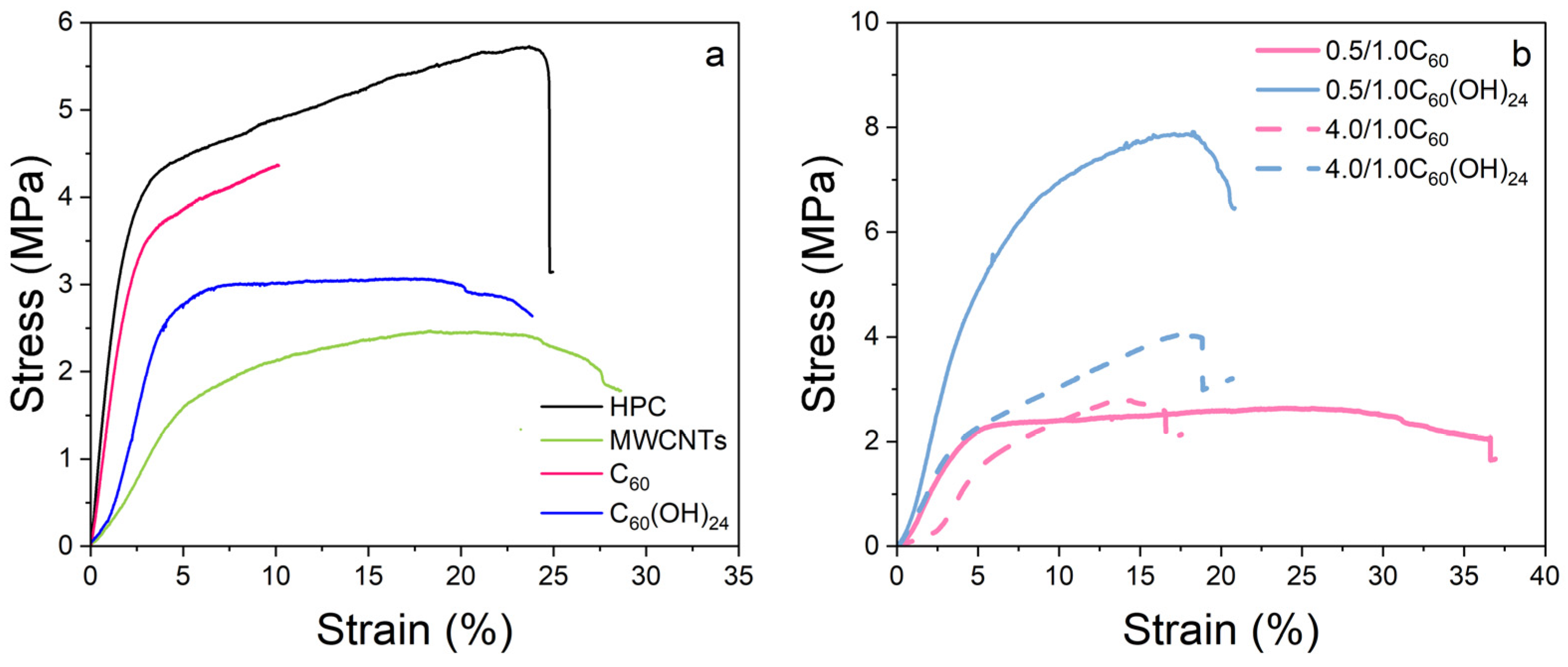

3.4. Mechanical Properties

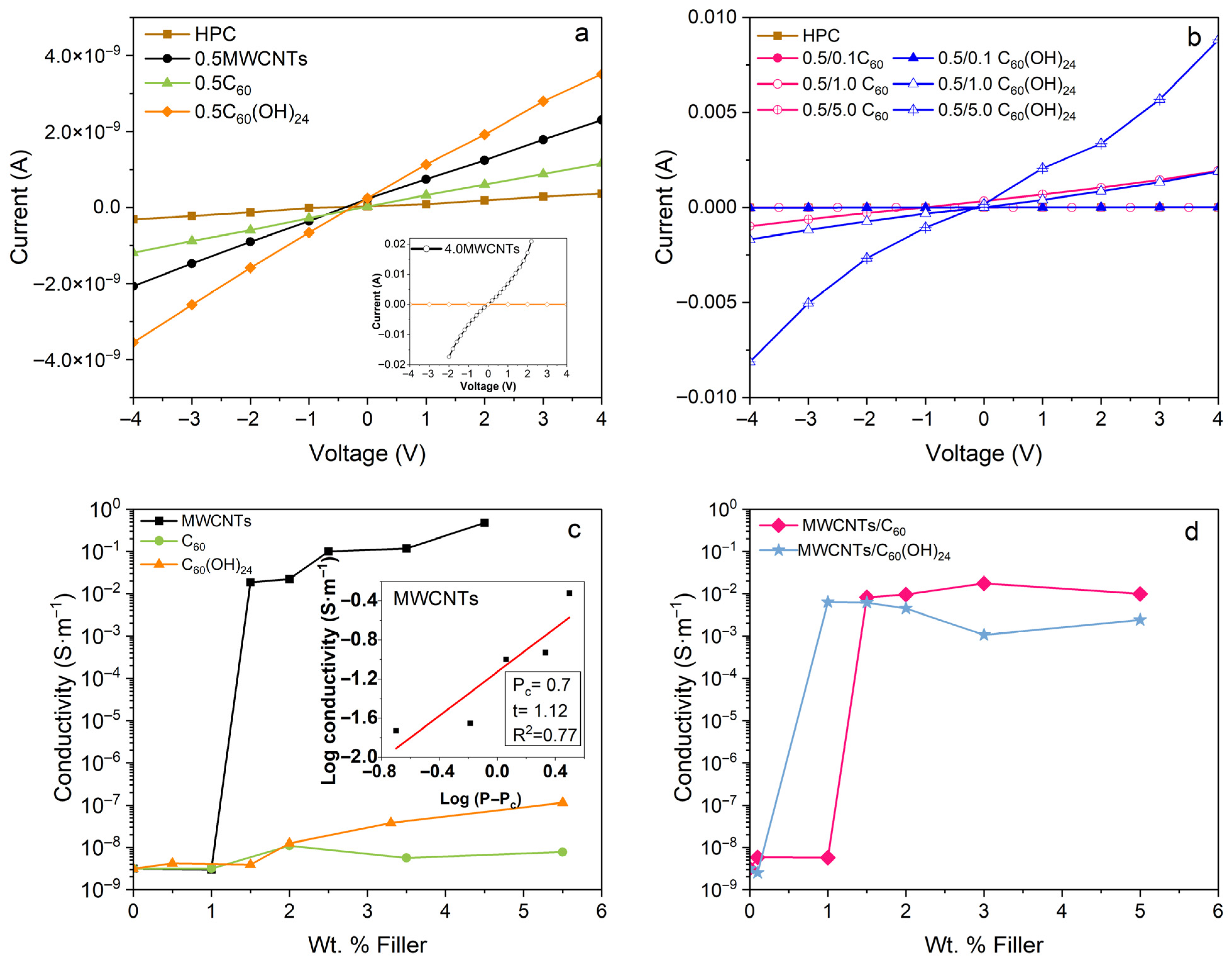

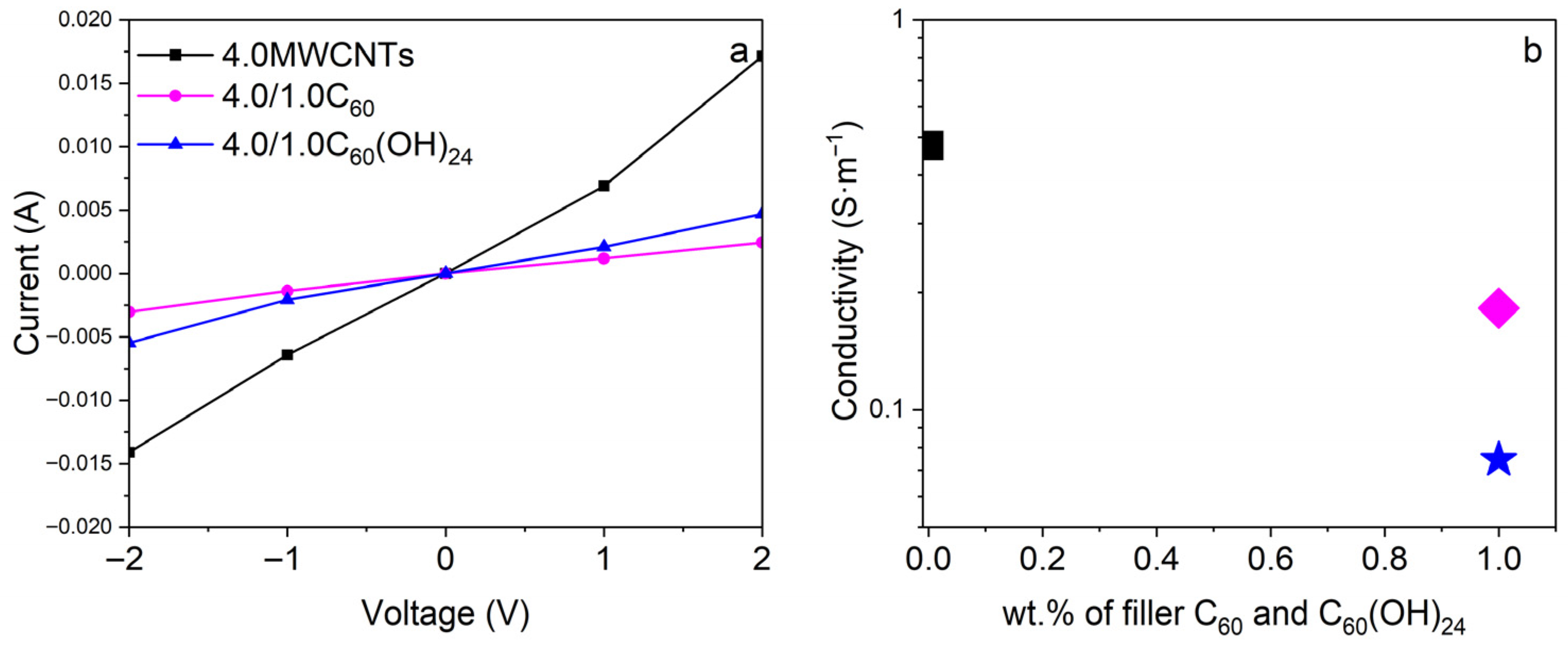

3.5. Electrical Conductivity Properties

3.6. Piezoresistive and Thermoresistive Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DSC | Differential-scanning calorimetry |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared (spectroscopy) |

| HPC | Hydroxypropyl cellulose |

| MWCNT | Multi-walled carbon nanotubes |

| PR | Piezoresistive (response) |

| TR | Thermoresistive (response) |

| SAXS | Small-angle X-ray scattering |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

References

- Díez, A.G.; Tubio, C.R.; Gómez, A.; Berastegi, J.; Bou-Ali, M.M.; Etxebarria, J.G.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Tuning Magnetorheological Functional Response of Thermoplastic Elastomers by Varying Soft-Magnetic Nanofillers. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2022, 33, 2610–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Tan, Q.; Yu, J.; Wang, M. A Global Perspective on E-Waste Recycling. Circ. Econ. 2023, 2, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Duenas, L.; Gomez, E.; Larrañaga, M.; Blanco, M.; Goitandia, A.M.; Aranzabe, E.; Vilas-Vilela, J.L. A Review on Sustainable Inks for Printed Electronics: Materials for Conductive, Dielectric and Piezoelectric Sustainable Inks. Materials 2023, 16, 3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassajfar, M.N.; Abdulkareem, M.; Horttanainen, M. End-of-Life Options for Printed Electronics in Municipal Solid Waste Streams: A Review of the Challenges, Opportunities, and Sustainability Implications. Flex. Print. Electron. 2024, 9, 033002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.; Alves, R.; Perinka, N.; Tubio, C.; Costa, P.; Lanceros-Mendéz, S. Water-Based Graphene Inks for All-Printed Temperature and Deformation Sensors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2020, 2, 2857–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polícia, R.; Peřinka, N.; Mendes-Felipe, C.; Martins, P.; Correia, D.M.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Toward Sustainable Electroluminescent Devices for Lighting and Sensing. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2024, 8, 2400140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, J.R.; Silva, T.A.; Rivas, G.A.; Janegitz, B.C. Novel Eco-Friendly Water-Based Conductive Ink for the Preparation of Disposable Screen-Printed Electrodes for Sensing and Biosensing Applications. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 409, 139968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, S.; Goswami, S.; Marques, A.; Gaspar, D.; Grey, P.; Cunha, I.; Nunes, D.; Pimentel, A.; Igreja, R.; Barquinha, P.; et al. Cellulose: A Contribution for the Zero e-Waste Challenge. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021, 6, 2000994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, T.; Farid, A.; Haq, F.; Kiran, M.; Ullah, A.; Zhang, K.; Li, C.; Ghazanfar, S.; Sun, H.; Ullah, R.; et al. A Review on the Modification of Cellulose and Its Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Karakoç, A.; Palko, T.; Yigitler, H.; Ruttik, K.; Jäntti, R.; Paltakari, J. A Review on Printed Electronics: Fabrication Methods, Inks, Substrates, Applications and Environmental Impacts. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2021, 5, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.H.; Avinash, K.; Varaprasad, B.K.S.V.L.; Goel, S. A Review on Printed Electronics with Digital 3D Printing: Fabrication Techniques, Materials, Challenges and Future Opportunities. J. Electron. Mater. 2022, 51, 2747–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.; Shuai, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X. Progress on Chemical Modification of Cellulose in “Green” Solvents. Polym. Chem. 2022, 13, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.I.; Biliuta, G.; Macsim, A.M.; Dinu, M.V.; Coseri, S. Chemistry of Hydroxypropyl Cellulose Oxidized by Two Selective Oxidants. Polymers 2023, 15, 3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes-Felipe, C.; Costa, P.; Roppolo, I.; Sangermano, M.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Bio-Based Piezo- and Thermoresistive Photocurable Sensing Materials from Acrylated Epoxidized Soybean Oil. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2022, 307, 2100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norizan, M.N.; Moklis, M.H.; Ngah Demon, S.Z.; Halim, N.A.; Samsuri, A.; Mohamad, I.S.; Knight, V.F.; Abdullah, N. Carbon Nanotubes: Functionalisation and Their Application in Chemical Sensors. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 43704–43732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dios, J.R.; Garcia-Astrain, C.; Gonçalves, S.; Costa, P.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Piezoresistive Performance of Polymer-Based Materials as a Function of the Matrix and Nanofiller Content to Walking Detection Application. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 181, 107678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Ayerdi, A.; Rubio-Peña, L.; Peřinka, N.; Oyarzabal, I.; Vilas, J.L.; Costa, P.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Towards Sustainable Temperature Sensor Production through CO2-Derived Polycarbonate-Based Composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Lee, J.H.; Shen, X.; Chen, X.; Kim, J.K. Graphene-Based Wearable Piezoresistive Physical Sensors. Mater. Today 2020, 36, 158–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ying, Y.; Ping, J. Structure, Synthesis, and Sensing Applications of Single-Walled Carbon Nanohorns. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 167, 112495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Min, L.; Niu, F.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, B.; Liu, Y.; Pan, K. Conductive Nanomaterials with Different Dimensions for Flexible Piezoresistive Sensors: From Selectivity to Applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2201886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumfleth, J.; Adroher, X.C.; Schulte, K. Synergistic Effects in Network Formation and Electrical Properties of Hybrid Epoxy Nanocomposites Containing Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes and Carbon Black. J. Mater. Sci. 2009, 44, 3241–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Yang, G.; Schubert, D.W. Electrically Conductive Polymer Composite Containing Hybrid Graphene Nanoplatelets and Carbon Nanotubes: Synergistic Effect and Tunable Conductivity Anisotropy. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2022, 5, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Araby, S.; Kuan, H.C.; Naeem, M.; Ma, J. A Comparative Study of Polymer Nanocomposites Containing Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene Nanoplatelets. Nano Mater. Sci. 2022, 4, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collavini, S.; Delgado, J.L. Fullerenes: The Stars of Photovoltaics. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2018, 2, 2480–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergeroglu, H.; Yildirim, S.; Ebeoglugil, M.F. Nano-Carbons in Biosensor Applications: An Overview of Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) and Fullerenes (C60). SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.C.; Cabral, J.T. Mechanism and Kinetics of Fullerene Association in Polystyrene Thin Film Mixtures. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 4530–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Pei, Z.; Jing, Z.; Song, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Sang, S. A Highly Stretchable Strain Sensor Based on CNT/Graphene/Fullerene-SEBS. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 11225–11232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, A.; Srdjenovic, B.; Seke, M.; Petrovic, D.; Injac, R.; Mrdjanovic, J. Review of Synthesis and Antioxidant Potential of Fullerenol Nanoparticles. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015, 567073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- João, J.P.; Hof, F.; Chauvet, O.; Zarbin, A.J.G.; Pénicaud, A. The Role of Functionalization on the Colloidal Stability of Aqueous Fullerene C60 Dispersions Prepared with Fullerides. Carbon 2021, 173, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seke, M.; Zivkovic, M.; Stankovic, A. Versatile Applications of Fullerenol Nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 660, 124313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón-Iglesias, M.; Lizundia, E.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Water-Soluble Cellulose Derivatives as Suitable Matrices for Multifunctional Materials. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 2786–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, C.E.; Spilotros, A.; Schwemmer, F.; Graewert, M.A.; Kikhney, A.; Jeffries, C.M.; Franke, D.; Mark, D.; Zengerle, R.; Cipriani, F.; et al. Versatile Sample Environments and Automation for Biological Solution X-Ray Scattering Experiments at the P12 Beamline (PETRA III, DESY). J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2015, 48, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanton, T.N.; Barnes, C.L.; Lelental, M. Applied Crystallography Preparation of Silver Behenate Coatings to Provide Low-to Mid-Angle Diffraction Calibration. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2000, 33, 172–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.; Costa, P.; Nunes-Pereira, J.; Silva, A.P.; Tubio, C.R.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Additive Manufacturing of Multifunctional Epoxy Adhesives with Self-Sensing Piezoresistive and Thermoresistive Capabilities. Compos. B Eng. 2025, 293, 112130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Armada, D.; González Rodríguez, V.; Costa, P.; Lanceros-Mendez, S.; Arias-Ferreiro, G.; Abad, M.J.; Ares-Pernas, A. Polyethylene/Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate/Carbon Nanotube Composites for Eco-Friendly Electronic Applications. Polym. Test. 2022, 112, 107642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htwe, Y.Z.N.; Mariatti, M.; Khan, J. Review on Solvent- and Surfactant-Assisted Water-Based Conductive Inks for Printed Flexible Electronics Applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, L.A.; Svergun, D.I. Structure Analysis by Small-Angle X-Ray and Neutron Scattering; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Golosova, A.A.; Adelsberger, J.; Sepe, A.; Niedermeier, M.A.; Lindner, P.; Funari, S.S.; Jordan, R.; Papadakis, C.M. Dispersions of Polymer-Modified Carbon Nanotubes: A Small-Angle Scattering Investigation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 15765–15774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokubo, K.; Matsubayashi, K.; Tategaki, H.; Takada, H.; Oshima, T. Facile Synthesis of Highly Water-Soluble Fullerenes More than Half-Covered by Hydroxyl Groups. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, V.T.; Kulvelis, Y.V.; Voronin, A.S.; Komolkin, A.V.; Kyzyma, E.A.; Tropin, T.V.; Garamus, V.M. Mechanisms of Supramolecular Ordering of Water-Soluble Derivatives of Fullerenes in Aqueous Media. Fuller. Nanotub. Carbon Nanostructures 2020, 28, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropin, T.V.; Kyrey, T.O.; Kyzyma, O.A.; Feoktistov, A.V.; Avdeev, M.V.; Bulavin, L.A.; Rosta, L.; Aksenov, V.L. Experimental Investigation of C 60/NMP/Toluene Solutions by UV-Vis Spectroscopy and Small-Angle Neutron Scattering. J. Surf. Investig. X-Ray Synchrotron Neutron Tech. 2013, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Velázquez, D.; Bello, A.; Pérez, E. Preparation and Characterisation of Hydrophobically Modified Hydroxypropylcellulose: Side-Chain Crystallisation. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2004, 205, 1886–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Carracedo, A.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Gómez-Amoza, J.L.; Concheiro, A. Chemical Structure and Glass Transition Temperature of Non-Ionic Cellulose Ethers. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2003, 73, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yu, S.; Luo, S.; Chu, B.; Sun, R.; Wong, C.P. Investigation of Nonlinear I-V Behavior of CNTs Filled Polymer Composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2016, 206, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Maestu, J.; García Díez, A.; Tubio, C.R.; Gómez, A.; Berasategui, J.; Costa, P.; Bou-Ali, M.M.; Etxebarria, J.G.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Ternary Multifunctional Composites with Magnetorheological Actuation and Piezoresistive Sensing Response. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2023, 5, 4296–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dios, J.R.; García-Astrain, C.; Costa, P.; Viana, J.C.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Carbonaceous Filler Type and Content Dependence of the Physical-Chemical and Electromechanical Properties of Thermoplastic Elastomer Polymer Composites. Materials 2019, 12, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.C.; Woo, J.S.; Park, S.Y. Flexible Carbonized Cellulose/Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Films with High Conductivity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 196, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfah, A.D.; Abdalla, S.; Ferjani, H.; Tavares, C.J.; Etzkorn, J. Optical, Electrical, and Structural Properties of Polyethylene Oxide/Fullerene Nanocomposite Films. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2024, 679, 415787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Bai, Y.; Li, Z.; Cheng, B. C60 as Fine Fillers to Improve Poly(Phenylene Sulfide) Electrical Conductivity and Mechanical Property. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghgoo, M.; Ansari, R.; Hassanzadeh-Aghdam, M.K. Synergic Effect of Graphene Nanoplatelets and Carbon Nanotubes on the Electrical Resistivity and Percolation Threshold of Polymer Hybrid Nanocomposites. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2021, 136, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Q.; Huang, Y.; Liao, X.; Niu, Y. Synergistic Effect of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes and Carbon Black on Rheological Behaviors and Electrical Conductivity of Hybrid Polypropylene Nanocomposites. Polym. Compos. 2018, 39, E723–E732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradonna, A.; Badini, C.; Padovano, E.; Pietroluongo, M. Electrical and Thermal Conductivity of Epoxy-Carbon Filler Composites Processed by Calendaring. Materials 2019, 12, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleh, M.H. Synergistic Effect of CNT/CB Hybrid Mixture on the Electrical Properties of Conductive Composites. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 065011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Yokozeki, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Wang, H.; Wu, L.; Koyanagi, J.; Sun, Q. The Decoupling Electrical and Thermal Conductivity of Fullerene/Polyaniline Hybrids Reinforced Polymer Composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2017, 144, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Zhang, L.; Yong, K.T.; Li, J.; Wu, Y. Recent Progress in Flexible Nanocellulosic Structures for Wearable Piezoresistive Strain Sensors. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 2021, 9, 11001–11029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Park, H.; Lee, G.; Jeong, Y.R.; Hong, S.Y.; Keum, K.; Yoon, J.; Kim, M.S.; Ha, J.S. Paper-Like, Thin, Foldable, and Self-Healable Electronics Based on PVA/CNC Nanocomposite Film. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1905968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, E.; Costa, P.; Tubio, C.R.; Vilaça, J.L.; Costa, C.M.; Lanceros-Méndez, S.; Miranda, D. Printable Piezoresistive Polymer Composites for Self-Sensing Medical Catheter Device Applications. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2023, 239, 110071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Wt.% C60 | Sample | wt.% C60(OH)24 | Sample | wt.% MWCNTs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5C60 | 0.5 | 0.5C60(OH)24 | 0.5 | 0.5MWCNTs | 0.5 |

| 1.0C60 | 1.0 | 1.0C60(OH)24 | 1.0 | 1.0MWCNTs | 1.0 |

| 1.5C60 | 1.5 | 1.5C60(OH)24 | 1.5 | 1.5MWCNTs | 1.5 |

| 3.0C60 | 3.0 | 3.0C60(OH)24 | 3.0 | 3.0MWCNTs | 3.0 |

| - | - | - | - | 4.0MWCNTs | 4.0 |

| 5.0C60 | 5.0 | 5.0C60(OH)24 | 5.0 | 5.0MWCNTs | 5.0 |

| Sample | wt.% MWCNTs/C60 | Sample | wt.% MWCNTs/C60(OH)24 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5/0.1C60 | 0.5/0.1 | 0.5/0.1C60(OH)24 | 0.5/0.1 |

| 0.5/1.0C60 | 0.5/1.0 | 0.5/1.0C60(OH)24 | 0.5/1.0 |

| 0.5/1.5C60 | 0.5/1.5 | 0.5/1.5C60(OH)24 | 0.5/1.5 |

| 0.5/2.0C60 | 0.5/2.0 | 0.5/2.0C60(OH)24 | 0.5/2.0 |

| 0.5/3.0C60 | 0.5/3.0 | 0.5/3.0C60(OH)24 | 0.5/3.0 |

| 0.5/5.0C60 | 0.5/5.0 | 0.5/5.0C60(OH)24 | 0.5/5.0 |

| 4.0/1.0C60 | 4.0/1.0 | 4.0/1.0C60(OH)24 | 4.0/1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martín-Ayerdi, A.; Tropin, T.; Peřinka, N.; Vilas-Vilela, J.L.; Costa, P.; Garamus, V.M.; Soloviov, D.; Petrenko, V.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Synergetic Effect of Fullerene and Fullerenol/Carbon Nanotubes in Cellulose-Based Composites for Electromechanical and Thermoresistive Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243259

Martín-Ayerdi A, Tropin T, Peřinka N, Vilas-Vilela JL, Costa P, Garamus VM, Soloviov D, Petrenko V, Lanceros-Méndez S. Synergetic Effect of Fullerene and Fullerenol/Carbon Nanotubes in Cellulose-Based Composites for Electromechanical and Thermoresistive Applications. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243259

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartín-Ayerdi, Ane, Timur Tropin, Nikola Peřinka, José Luis Vilas-Vilela, Pedro Costa, Vasil M. Garamus, Dmytro Soloviov, Viktor Petrenko, and Senentxu Lanceros-Méndez. 2025. "Synergetic Effect of Fullerene and Fullerenol/Carbon Nanotubes in Cellulose-Based Composites for Electromechanical and Thermoresistive Applications" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243259

APA StyleMartín-Ayerdi, A., Tropin, T., Peřinka, N., Vilas-Vilela, J. L., Costa, P., Garamus, V. M., Soloviov, D., Petrenko, V., & Lanceros-Méndez, S. (2025). Synergetic Effect of Fullerene and Fullerenol/Carbon Nanotubes in Cellulose-Based Composites for Electromechanical and Thermoresistive Applications. Polymers, 17(24), 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243259