Sustainable Membrane Development: A Biopolymer Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Membrane Manufacturing Pollution

3. Current Sustainable Membrane Manufacturing

4. Biopolymers

5. The Role of Biopolymers in Membrane Manufacturing

| Biopolymer | Method & Solvent | Membrane Properties | Application | Environmental Impact | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxymethyl chitin/nano-hydroxyapatite | Freeze dryer and cast & ethanol. |

| Bone regeneration. | Biodegradability (over 60% after 27 days with 2 mg/L lysozyme). | [85] |

| Modified lignin/zeolite/chitosan | Casting/dichloromethane-dimethylformamide |

| Preservation of perishable foods. | No eco-friendly solvents were used. | [89] |

| Chitosan/pectin/UiO-66-NH2 nanoparticles | Casting & acetic acid, water |

| Detoxifying arsenic from water. |

| [90] |

| Polylactic acid-cellulose diacetate/Polylactic acid-carbon nanotubes | Layer-by-layer electrospinning & Dichloromethane and dimethylformamide. |

| Oil/water separation |

| [91] |

| Pullulan/chitosan/salvianolic acid | Centrifugal spinning/citric acid solution |

| Drug delivery system | ND | [92] |

| Pectin/Ammonium iodide | Casting/water |

| Electrochemical application |

| [93] |

| Collagen | Nanofibrillation and functionalization |

| Air purification |

| [88] |

6. Research Opportunities in Biopolymer Production for Membrane Manufacturing

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barhoum, A.; Deshmukh, K.; García Betancourt, M.L.; Alibakhshi, S.; Mousavi, S.; Meftahi, A.; Sabery, M.; Samyn, P. Nanocelluloses as Sustainable Membrane Materials for Separation and Filtration Technologies: Principles, Opportunities, and Challenges. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 317, 121057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Li, J.; Zeng, P.; Duan, L.; Dong, J.; Ma, Y.; Yang, L. The Application of Membrane Separation Technology in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Membranes 2024, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. Grand challenge in membrane applications: Liquid. Front. Membr. Sci. Technol. 2023, 2, 1177528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Zhu, Z.; Li, L.; Shi, J.; Li, Z.; Zuo, X. Membrane fouling and cleaning strategies in microfiltration/ultrafiltration and dynamic membrane. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 318, 123977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsawaftah, N.; Abuwatfa, W.; Darwish, N.; Husseini, G. A comprehensive review on membrane fouling: Mathematical modelling, prediction, diagnosis, and mitigation. Water 2021, 13, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.Y. Role of spacers in osmotic membrane desalination: Advances, challenges, practical and artificial intelligence-driven solutions. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 201, 107587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, N.; Tao, Z.; Han, L.; Wei, B.; Qi, R.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Z. Polyamide membrane based on hydrophilic intermediate layer for simultaneous wetting and fouling resistance in membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 717, 123596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yuan, C.; Yu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, W.; Chen, X.; Bai, L.; Meng, S.; Zhou, Y. A layer-by-layer-assembly modified semi-aromatic polyamide membrane with enhanced fouling resistance. J. Membr. Sci. 2026, 738, 124720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavian, H.; Černík, M.; Dvořák, L. Advanced (bio) fouling resistant surface modification of PTFE hollow-fiber membranes for water treatment. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onuk, E.; Gungormus, E.; Cihanoğlu, A.; Altinkaya, S.A. Development of a dopamine-based surface modification technique to enhance protein fouling resistance in commercial ultrafiltration membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 717, 123554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Ismail, N.; Essalhi, M.; Tysklind, M.; Athanassiadis, D.; Tavajohi, N. Assessment of the environmental impact of polymeric membrane production. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 622, 118987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razman, K.K.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Mohammad, A.W. An overview of LCA applied to various membrane technologies: Progress, challenges, and harmonization. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 27, 102803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Jiménez, M.; Palacio, D.A.; Palencia, M.; Meléndrez, M.F.; Rivas, B.L. Bio-Based Polymeric Membranes: Development and Environmental Applications. Membranes 2023, 13, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogje, M.; Satdive, A.; Mestry, S.; Mhaske, S.T. Biopolymers: A Comprehensive Review of Sustainability, Environmental Impact, and Lifecycle Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Getahun, M.J.; Kassie, B.B.; Alemu, T.S. Recent advances in biopolymer synthesis, properties, & commercial applications: A review. Process. Biochem. 2024, 145, 261–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greca, L.G.; Azpiazu, A.; Reyes, G.; Rojas, O.J.; Tardy, B.L.; Lizundia, E. Chitin-based pulps: Structure-property relationships and environmental sustainability. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 325, 121561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Marín, R.; Morales, A.; Erdocia, X.; Iturrondobeitia, M.; Labidi, J.; Lizundia, E. Chitosan–Chitin Nanocrystal Films from Lobster and Spider Crab: Properties and Environmental Sustainability. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 10363–10375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradali, M.F.; Rehm, B.H.A. Bacterial biopolymers: From pathogenesis to advanced materials. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanrasu, K.; Manivannan, A.C.; Rengarajan, H.J.R.; Kandaiah, R.; Ravindran, A.; Panneerselvan, L.; Palanisami, T.; Sathish, C.I. Eco-friendly biopolymers and composites: A sustainable development of adsorbents for the removal of pollutants from wastewater. npj Mater. Sustain. 2025, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Biron, D.; Espíndola, J.C.; Subtil, E.L.; Mierzwa, J.C. A New Approach to the Development of Hollow Fiber Membrane Modules for Water Treatment: Mixed Polymer Matrices. Membranes 2023, 13, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, C.; Wasyłeczko, M.; Lewińska, D.; Chwojnowski, A. A Comprehensive Review of Hollow-Fiber Membrane Fabrication Methods across Biomedical, Biotechnological, and Environmental Domains. Molecules 2024, 29, 2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wei, W.; Chen, Z.; Wu, L.; Duan, H.; Zheng, M.; Wang, D.; Ni, B.J. The threats of micro- and nanoplastics to aquatic ecosystems and water health. Nat. Water 2025, 3, 764–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrass, F.; Benjelloun, M. Health and environmental effects of the use of N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone as a solvent in the manufacture of hemodialysis membranes: A sustainable reflexion. Nefrologia 2022, 42, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukonza, S.S.; Chaukura, N. Bird’s-eye view of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances pollution research in the African hydrosphere. npj Clean Water 2025, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliwan, T.; Hu, J. Release of microplastics from polymeric ultrafiltration membrane system for drinking water treatment under different operating conditions. Water Res. 2025, 274, 123047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Zheng, C.M.; Wang, Y.J.; Wang, Y.L.; Chiu, H.W. Effects of microplastics and nanoplastics on the kidney and cardiovascular system. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2025, 21, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.N.; Ghude, S.D.; Nivdange, S.D.; Panchang, R.; Pipal, A.S.; Mukherjee, A.; Sharma, H.; Kumar, V. Characterization and health risk assessment of airborne microplastics in Delhi NCR. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Okochi, H.; Tani, Y.; Hayami, H.; Minami, Y.; Katsumi, N.; Takeuchi, M.; Sorimachi, A.; Fujii, Y.; Kajino, M.; et al. Airborne hydrophilic microplastics in cloud water at high altitudes and their role in cloud formation. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 3055–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Auffan, M.; Eckelman, M.J.; Elimelech, M.; Kim, J.H.; Rose, J.; Zuo, K.; Li, Q.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Trends, risks and opportunities in environmental nanotechnology. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prazeres Mazur, L.; Reis Ferreira, R.; Felix da Silva Barbosa, R.; Henrique Santos, P.; Barcelos da Costa, T.; Gurgel Adeodato Vieira, M.; da Silva, A.; dos Santos Rosa, D.; Helena Innocentini Mei, L. Development of novel biopolymer membranes by electrospinning as potential adsorbents for toxic metal ions removal from aqueous solution. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 395, 123782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalani, D.V.; Nutan, B.; Singh Chandel, A.K. Sustainable Development of Membranes. In Encyclopedia of Green Materials; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanzada, N.K.; Al-Juboori, R.A.; Khatri, M.; Ahmed, F.E.; Ibrahim, Y.; Hilal, N. Sustainability in Membrane Technology: Membrane Recycling and Fabrication Using Recycled Waste. Membranes 2024, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Dai, R.; Wang, Z. Closing the loop of membranes by recycling end-of-life membranes: Comparative life cycle assessment and economic analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 198, 107153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, S.L.; Gunawan, P.; Hu, X. Critical comparison of cellulose dissolution methods through life cycle analysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.J.; Leiu, Y.X.; Hoo, D.Y.; Kikuchi, Y.; Kanematsu, Y.; Tan, K.W.; Teah, H.Y. Life cycle assessment and techno-economic analysis of nanocellulose synthesis via chlorine-free biomass pretreatments. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 203, 107912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, A.; Saeed, B.; AlMohamadi, H.; Lee, M.; Gilani, M.A.; Nawaz, R.; Khan, A.L.; Yasin, M. Sustainable and green membranes for chemical separations: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 336, 126271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Nunes, S.P. Green solvents for membrane manufacture: Recent trends and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 28, 100427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, O.; Mourya, Y.; Kavya, K.L.; Mutthuraj, D.; Rao, P.V.; Basalingappa, K.M. 3D Printing and 4D Printing: Sustainable Manufacturing Techniques for Green Biomaterials. In Sustainable Green Biomaterials as Drug Delivery Systems; Malviya, R., Sundram, S., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 103–130. ISBN 978-3-031-79062-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Y.; Hilal, N. The potentials of 3D-printed feed spacers in reducing the environmental footprint of membrane separation processes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabortty, S.; Kumar, R.; Nayak, J.; Jeon, B.-H.; Dargar, S.K.; Tripathy, S.K.; Pal, P.; Ha, G.-S.; Kim, K.H.; Jasiński, M. Green synthesis of MeOH derivatives through in situ catalytic transformations of captured CO2 in a membrane integrated photo-microreactor system: A state-of-art review for carbon capture and utilization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 182, 113417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormos, C.-C. Green hydrogen production from decarbonized biomass gasification: An integrated techno-economic and environmental analysis. Energy 2023, 270, 126926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Mazhar, A.R.; Ubaid, A.; Shah, S.M.H.; Riaz, Y.; Talha, T.; Jung, D.-W. A comprehensive review of membrane-based water filtration techniques. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 14, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, N.; Sharma, R.; Foorginezhad, S.; Jouyandeh, M.; Asadnia, M.; Rabiee, M.; Akhavan, O.; Lima, E.C.; Formela, K.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; et al. Green and Sustainable Membranes: A review. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyannarayana, K.V.V.; Singh, R.; Rani, S.L.S.; Sreekanth, M.; Raja, V.K.; Ahn, Y.-H. A paradigm assessment of low-cost ceramic membranes: Raw materials, fabrication techniques, cost analysis, environment impact, wastewater treatment, fouling, and future prospects. J. Water Process. Eng. 2024, 68, 106430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gendi, A.; Abdallah, H.; Amin, A. Economic study for blend membrane production. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2021, 45, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, N.; Runge, T.; Bergman, R.D.; Nepal, P.; Alikhani, N.; Li, L.; O’Neill, S.R.; Wang, J. Techno-economic analysis and life cycle assessment of manufacturing a cellulose nanocrystal-based hybrid membrane. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 40, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

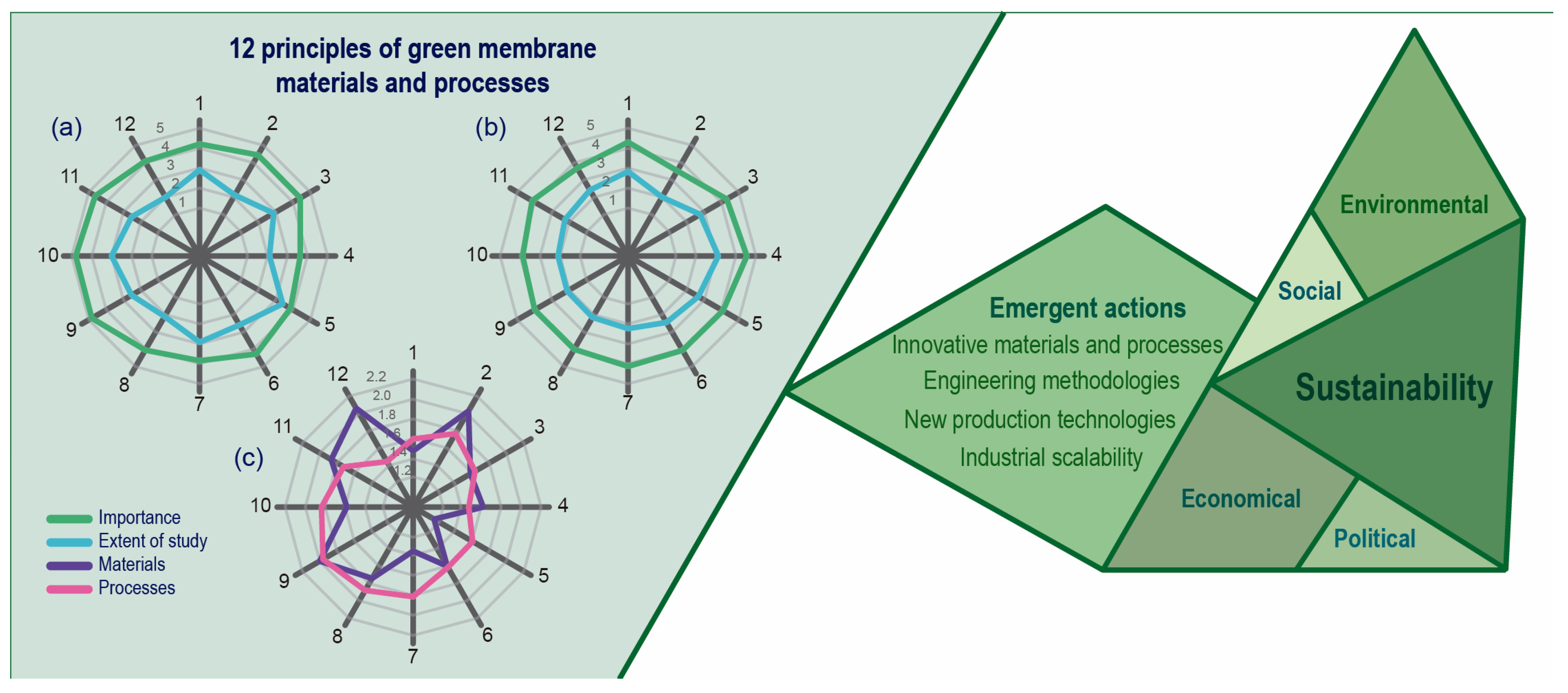

- Szekely, G. The 12 principles of green membrane materials and processes for realizing the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. RSC Sustain. 2024, 2, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, C.Y.; Burrows, A.D.; Xie, M. Sustainable Polymeric Membranes: Green Chemistry and Circular Economy Approaches. ACS Es&T Eng. 2025, 5, 1882–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpanez, T.G.; Moreira, V.R.; Silva, J.B.G.; Otenio, M.H.; Amaral, M.C.S. Membranes for nutrient recovery from waste and production of organo-mineral fertilizer in the context of circular economy. Water Res. 2026, 288, 124560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Knauer, K.M. Trends and future outlooks in circularity of desalination membrane materials. Front. Membr. Sci. Technol. 2023, 2, 1169158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, M.R.; Weinman, S.T. Membranes from upcycled waste plastics: Current status, challenges, and future outlook. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2025, 48, 101106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Ma, B.; Zou, W.; Zeng, J.; Dai, R.; Wang, Z. Alkaline pre-treatment enables controllable downcycling of Si-Al fouled end-of-life RO membrane to NF and UF membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 690, 122209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemer, H.; Wald, S.; Semiat, R. Challenges and Solutions for Global Water Scarcity. Membranes 2023, 13, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felicioni, L.; Jiránek, M.; Lupíšek, A. Environmental impacts of waterproof membranes with respect to their radon resistance. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 35, e00541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre, E. The Future of Membrane Separation Processes: A Prospective Analysis. Front. Chem. Eng. 2022, 4, 916054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.F.; Jiang, Z.; Livingston, A.G. Advancing membrane technology in organic liquids towards a sustainable future. Nat. Sustain. 2025, 8, 594–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edo, G.I.; Ndudi, W.; Yousif, E.; Gaaz, T.S.; Jikah, A.N.; Isoje, E.F.; Igbuku, U.A.; Akpoghelie, P.O.; Oberhiri Oberhiri, S.; Ufuoma, E.G.; et al. A general review on biopolymers composites. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2025, 303, 1451–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaounakis, M. Chapter 1—Introduction. In Biopolymers: Processing and Products; Niaounakis, M., Ed.; William Andrew Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 1–77. ISBN 978-0-323-26698-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zarski, A.; Kapusniak, K.; Ptak, S.; Rudlicka, M.; Coseri, S.; Kapusniak, J. Functionalization Methods of Starch and Its Derivatives: From Old Limitations to New Possibilities. Polymers 2024, 16, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, T.; Arora, S.; Pahwa, R. Cellulose and its derivatives: Structure, modification, and application in controlled drug delivery. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triunfo, M.; Tafi, E.; Guarnieri, A.; Salvia, R.; Scieuzo, C.; Hahn, T.; Zibek, S.; Gagliardini, A.; Panariello, L.; Coltelli, M.B.; et al. Characterization of chitin and chitosan derived from Hermetia illucens, a further step in a circular economy process. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, F.; Zil-E-Aimen, N.; Ahmad, R.; Mir, S.; Awwad, N.S.; Ibrahium, H.A. Carrageenan: Structure, properties and applications with special emphasis on food science. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 22035–22062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getino, L.; Martín, J.L.; Chamizo-Ampudia, A. A Review of Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Characterization, Production, and Application from Waste. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Li, X.; Duan, Y.; Li, Q.; Qu, Y.; Zhong, G.; Qiu, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Pan, X. Extraction and characterization of chitosan from Eupolyphaga sinensis Walker and its application in the preparation of electrospinning nanofiber membranes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2023, 222, 113030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumounshar, N.; Pandey, R.P.; Hasan, S.W. Enhanced hydrophilicity and antibacterial efficacy of in-situ silver nanoparticles decorated Ti3C2Tx/Polylactic acid composite membrane for real hospital wastewater purification. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otitoju, T.A.; Kim, C.H.; Ryu, M.; Park, J.; Kim, T.K.; Yoo, Y.; Park, H.; Lee, J.H.; Cho, Y.H. Exploring green solvents for the sustainable fabrication of bio-based polylactic acid membranes using nonsolvent-induced phase separation. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 467, 142905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Nguyen Thi, H.; Kang, J.; Hwang, J.; Kim, S.; Park, S.; Lee, J.-H.; Abdellah, M.H.; Szekely, G.; Suk Lee, J.; et al. Sustainable fabrication of solvent resistant biodegradable cellulose membranes using green solvents. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 494, 153201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhong, M.; Wang, W.; Lu, N.; Gou, Y.; Cai, W.; Huang, J.; Lai, Y. Engineering biodegradable bacterial cellulose/polylactic acid multi-scale fibrous membrane via co-electrospinning-electrospray strategy for efficient, wet-stable, durable PM0.3 filtration. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 352, 128143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnabawy, E.; Sun, D.; Shearer, N.; Shyha, I. The effect of electro blow spinning parameters on the characteristics of polylactic acid nanofibers: Towards green development of high-performance biodegradable membrane. Polymer 2024, 311, 127553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamah, S.C.; Goh, P.S.; Ng, B.C.; Abdullah, M.S.; Ismail, A.F.; Samavati, Z.; Ahmad, N.A.; Raji, Y.O. The utilization of chitin and chitosan as green modifiers in nanocomposite membrane for water treatment. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 62, 105394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoor, S.; Kandel, D.R.; Chang, S.; Karayil, J.; Lee, J. Carrageenan/calcium alginate composite hydrogel filtration membranes for efficient cationic dye separation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270, 132309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ullah, S.; Ullah, S.; Shakeel, M.; Afsar, T.; Husain, F.M.; Amor, H.; Razak, S. Innovative biopolymers composite based thin film for wound healing applications. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.H.; Lee, M.S.; Kim, D.Y.; Shin, M.G.; An, S.; Kang, D.K.; Kim, J.F.; Nam, S.E.; Park, S.J.; Lee, J.H. Biopolymer-supported thin-film composite membranes for reverse osmosis. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 159264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, I.; Al-Abduljabbar, A. Efficient Production and Experimental Analysis of Bio-Based PLA-CA Composite Membranes via Electrospinning for Enhanced Mechanical Performance and Thermal Stability. Polymers 2025, 17, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Fan, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Meng, Y.; Chi, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, C.; Sun, H.; Zhang, H.; et al. Preparation and characterization of gelatin/bacterial nanofibrillated cellulose composite membranes based on an ecological engineering strategy. Food Hydrocoll. 2026, 172, 111928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Sharma, S.S. Biopolymer-Based Nanocomposites. In Handbook of Biopolymers; Thomas, S., AR, A., Jose Chirayil, C., Thomas, B., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–28. ISBN 978-981-16-6603-2. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, S.; Lyczko, N.; Thomas, S.; Leruth, D.; Germeau, A.; Fati, D.; Nzihou, A. Fabrication of eco-friendly nanocellulose-chitosan-calcium phosphate ternary nanocomposite for wastewater remediation. Chemosphere 2024, 363, 142779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhya, P.K.; Sreekala, M.S.; Thomas, S. Biopolymer-Based Blend Nanocomposites. In Handbook of Biopolymers; Thomas, S., AR, A., Jose Chirayil, C., Thomas, B., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–28. ISBN 978-981-16-6603-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, B.L.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. Synergistic effects of nucleating agent, chain extender and nanocrystalline cellulose on PLA and PHB blend films: Evaluation of morphological, mechanical and functional attributes. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 215, 118614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Hassan Vakili, M.; Ameri, E. Fabrication and evaluation of a biopolymer-based nanocomposite membrane for oily wastewater treatment. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 28, 102560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutharsan, M.; Senthil Murugan, K.; Narayanan, K.; Natarajan, T.S. Chitosan/agar-agar/TiO2 biopolymer nanocomposite film for solar photocatalysis, antibacterial activity, and food preservation applications. Next Mater. 2025, 9, 101225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaikundam, M.; Santhanam, A. Magnesium oxide nanoparticles incorporated with dual polymers and pectin stabilized hydroxyapatite as a nanocomposite membrane for tissue engineering. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 726, 137963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, B.; Zhang, F.; Dai, S.Y.; Foston, M.; Tang, Y.J.; Yuan, J.S. Engineering strategies to optimize lignocellulosic biorefineries. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2025, 3, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, R.; Permala, R.; Iglauer, S.; Zargar, M. Biopolymer-based membranes and their application in per- and polyfluorinated substances removal: Perspective review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 346, 103669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Yuan, X.; Xiao, J.; Jiang, X. Hemostasis-osteogenesis integrated Janus carboxymethyl chitin/hydroxyapatite porous membrane for bone defect repair. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 313, 120888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checchetto, R.; De Angelis, M.G.; Minelli, M. Exploring the membrane-based separation of CO2/CO mixtures for CO2 capture and utilisation processes: Challenges and opportunities. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 346, 127401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Lee, R.; Rajan Sheena, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Behera, H.; Maiti, P.K.; Freeman, B.D.; Kumar, M. Highly Selective Molecular-Sieving Membranes by Interfacial Polymerization for H2Purification. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 20309–20320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Zhao, P.; Cao, D.; Li, R.; Zhao, X.; Du, Y.; Li, K.; Chen, C.; Liu, G. Nanofibrillated collagen fiber networks for enhanced air purification. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.-C.; Su, M.-Y.; Yuan, X.-Y.; Lv, H.-Q.; Feng, R.; Wu, L.-J.; Gao, X.-P.; An, Y.-X.; Li, Z.-W.; Li, M.-Y.; et al. Green fabrication of modified lignin/zeolite/chitosan-based composite membranes for preservation of perishable foods. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, H.; Rosales, M.; Zarandona, I.; Serra, J.; Gonçalves, B.F.; Valverde, A.; Cavalcanti, L.P.; Lanceros-Mendez, S.; García, A.; de la Caba, K.; et al. Metal-Organic Framework Functionalized Chitosan/Pectin Membranes for Solar-Driven Photo-Oxidation and Adsorption of Arsenic. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Feng, G.; Li, G.; Zhang, Z.; Xiang, J.; Jiao, F.; Chen, T.; Zhao, H. Structurally integrated janus polylactic acid fibrous membranes for oil-water separation. J. Water Process. Eng. 2024, 68, 106525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Keniry, M.; Padilla, V.; Anaya-Barbosa, N.; Javed, M.N.; Gilkerson, R.; Gomez, K.; Ashraf, A.; Narula, A.S.; Lozano, K. Development of pullulan/chitosan/salvianolic acid ternary fibrous membranes and their potential for chemotherapeutic applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 250, 126187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukrishnan, M.; Shanthi, C.; Selvasekarapandian, S.; Premkumar, R. Biodegradable flexible proton conducting solid biopolymer membranes based on pectin and ammonium salt for electrochemical applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 5387–5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apriyanto, A.; Compart, J.; Fettke, J. A review of starch, a unique biopolymer—Structure, metabolism and in planta modifications. Plant Sci. 2022, 318, 111223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchis, F.; Vanzolini, T.; Maricchiolo, E.; Bellucci, M.; Menotta, M.; Di Mambro, T.; Aluigi, A.; Zattoni, A.; Roda, B.; Marassi, V.; et al. A biotechnological approach for the production of new protein bioplastics. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 19, e2300363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Alsharbaty, M.H.M.; Al-Tohamy, R.; Naji, G.A.; Elsamahy, T.; Mahmoud, Y.A.G.; Kornaros, M.; Sun, J. A review of the fungal polysaccharides as natural biopolymers: Current applications and future perspective. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273, 132986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.N. Microbial biopolymers: A sustainable alternative to traditional petroleum-based polymers for a greener future. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parati, M.; Khalil, I.; Tchuenbou-magaia, F.; Adamus, G.; Mendrek, B.; Hill, R.; Radecka, I. Building a circular economy around poly (D/L-γ-glutamic acid)—A smart microbial biopolymer. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 61, 108049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, A.; Hazeena, S.; Lakshmi, N.M.; Arun, K.B.; Madhavan, A.; Sirohi, R.; Tarafdar, A.; Sindhu, R.; Awasthi, M.; Pandey, A.; et al. Bacterial biopolymers: From production to applications in biomedicine. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 25, 100582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, S.S.; Annapure, U.S. Optimization of exopolysaccharide production from the novel Enterococcus species, using statistical design of experiment. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 55, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thajuddin, F.; Rasheed, A.S.; Palanivel, P.; Thajuddin, S.F.; Nooruddin, T.; Dharumadurai, D. Evolutionary adaptations of cyanobacterial polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) biosynthesis and metabolic pathways in Spirulina, Arthrospira, and Limnospira spp. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekumar, S.; Wattjes, J.; Niehues, A.; Mengoni, T.; Mendes, A.C.; Morris, E.R.; Goycoolea, F.M.; Moerschbacher, B.M. Biotechnologically produced chitosans with nonrandom acetylation patterns differ from conventional chitosans in properties and activities. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asase, R.V.; Glukhareva, T.V. Integrating waste management with biopolymer innovation: A new frontier in xanthan gum production. Process. Biochem. 2025, 154, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrtusová, D.; Zimmermann, B.; Kohler, A.; Shapaval, V. Enhanced co-production of extracellular biopolymers and intracellular lipids by Rhodotorula using lignocellulose hydrolysate and fish oil by-product urea. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2025, 18, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basri, S.; Shee, D.; Panda, T.K.; Bhattacharyya, D. Waste to materials: Preparation and characterization of nanocomposite films using extracellular polymeric substances derived from centrifuged sewage sludge. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Kannaujiya, V.K. Bacterial extracellular biopolymers: Eco-diversification, biosynthesis, technological development and commercial applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradinho, J.; Allegue, L.D.; Ventura, M.; Melero, J.A.; Reis, M.A.M.; Puyol, D. Up-scale challenges on biopolymer production from waste streams by Purple Phototrophic Bacteria mixed cultures: A critical review. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 327, 124820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Knoblauch, D.; Mederake, L. Government policies combatting plastic pollution. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2021, 28, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morales-Jiménez, M.; Martínez-Gutiérrez, G.A.; Perez-Tijerina, E.; Solis-Pomar, F.; Meléndrez, M.F.; Palacio, D.A. Sustainable Membrane Development: A Biopolymer Approach. Polymers 2025, 17, 3260. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243260

Morales-Jiménez M, Martínez-Gutiérrez GA, Perez-Tijerina E, Solis-Pomar F, Meléndrez MF, Palacio DA. Sustainable Membrane Development: A Biopolymer Approach. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3260. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243260

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorales-Jiménez, Mónica, Gabino A. Martínez-Gutiérrez, Eduardo Perez-Tijerina, Francisco Solis-Pomar, Manuel F. Meléndrez, and Daniel A. Palacio. 2025. "Sustainable Membrane Development: A Biopolymer Approach" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3260. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243260

APA StyleMorales-Jiménez, M., Martínez-Gutiérrez, G. A., Perez-Tijerina, E., Solis-Pomar, F., Meléndrez, M. F., & Palacio, D. A. (2025). Sustainable Membrane Development: A Biopolymer Approach. Polymers, 17(24), 3260. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243260