A Method for Mitigating Degradation Effects on Polyamide Textile Yarn During Mechanical Recycling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Samples

2.3. Characterization

3. Results

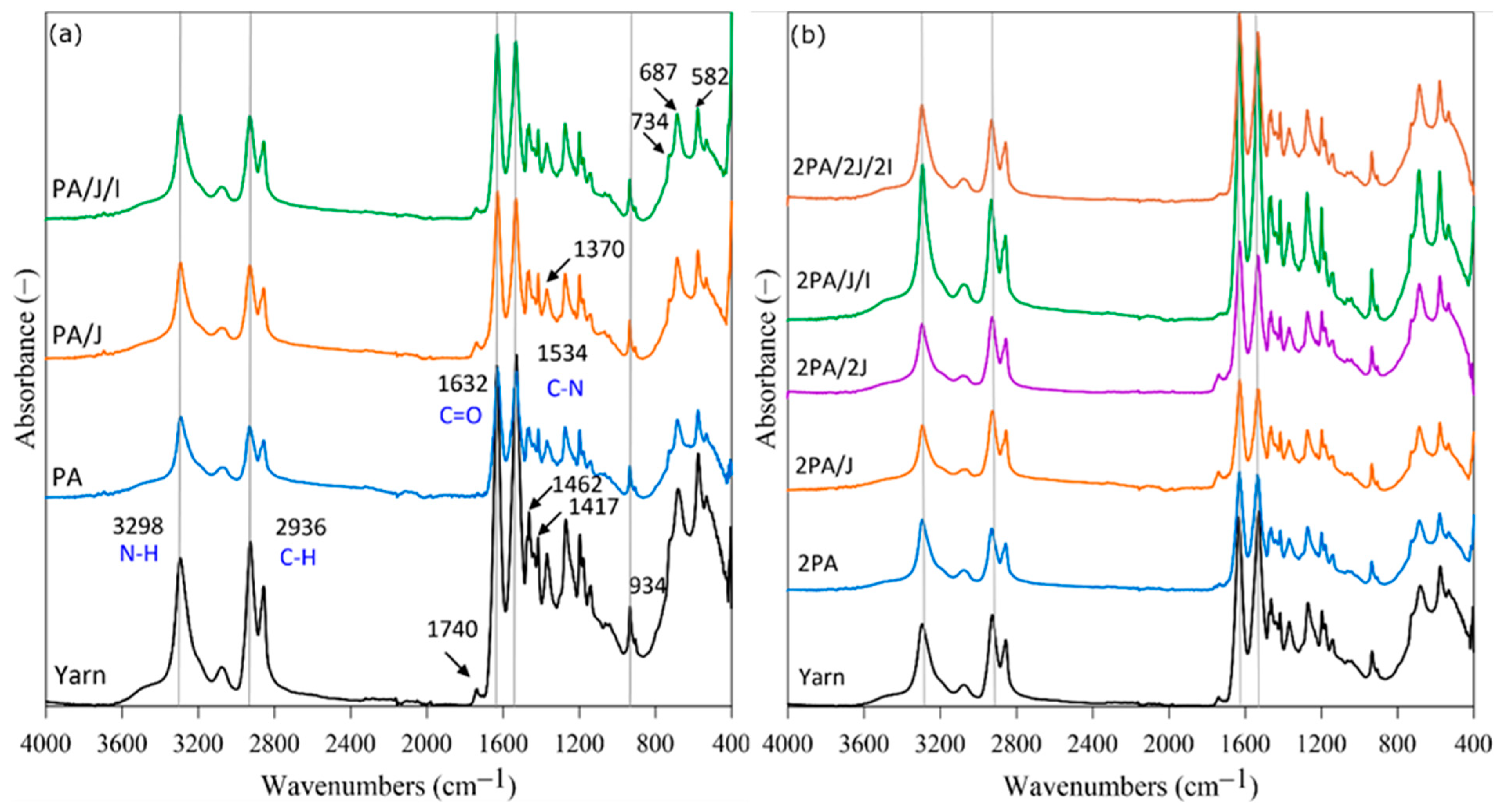

3.1. Structural Changes

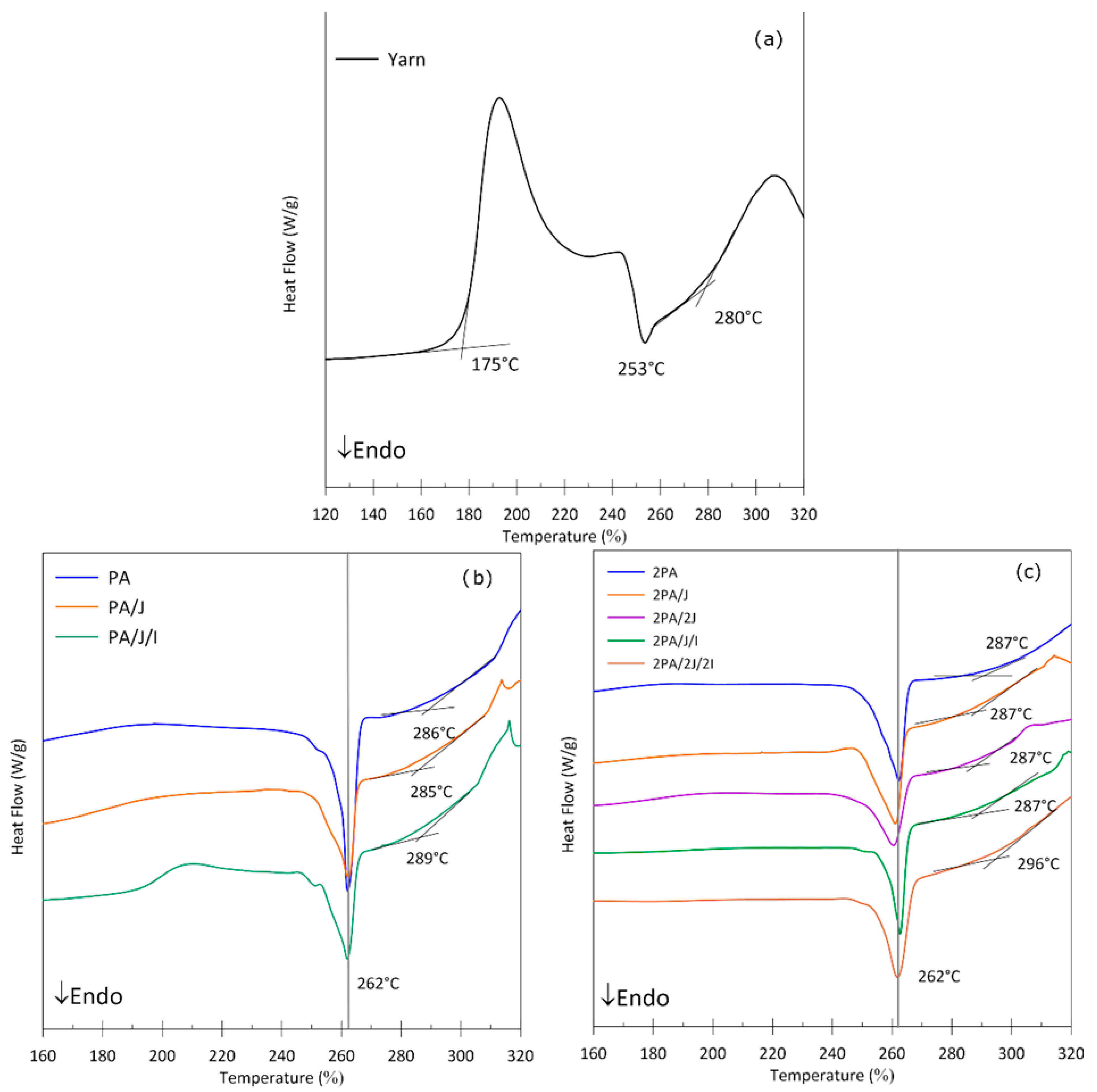

3.2. Thermal Properties

3.3. Analysis of Viscosity Parameters

| Samples Designation | RV (−) | VN (mL/g) | [η] (dL/g) | Mv * (g/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yarn | 1.76 | 136 ± 2 | 1.11 | 25,000 |

| PA | 1.98 | 137 ± 1 | 1.11 | 25,500 |

| PA/J | 1.98 | 134 ± 1 | 1.12 | 27,800 |

| PA/J/I | 1.95 | 135 ± 2 | 1.14 | 35,800 |

| 2PA | 1.96 | 137 ± 0 | 1.12 | 27,500 |

| 2PA/J | 2.01 | 146 ± 1 | 1.20 | 50,700 |

| 2PA/2J | 2.09 | 149 ± 2 | 1.21 | 54,800 |

| 2PA/J/I | 2.09 | 143 ± 1 | 1.15 | 38,100 |

| 2PA/2J/2I | 2.00 | 139 ± 1 | 1.14 | 36,000 |

3.4. Mass Spectrometry Characterization of the PA66 Pyrolysis Products

3.5. Oxidation Onset Temperature

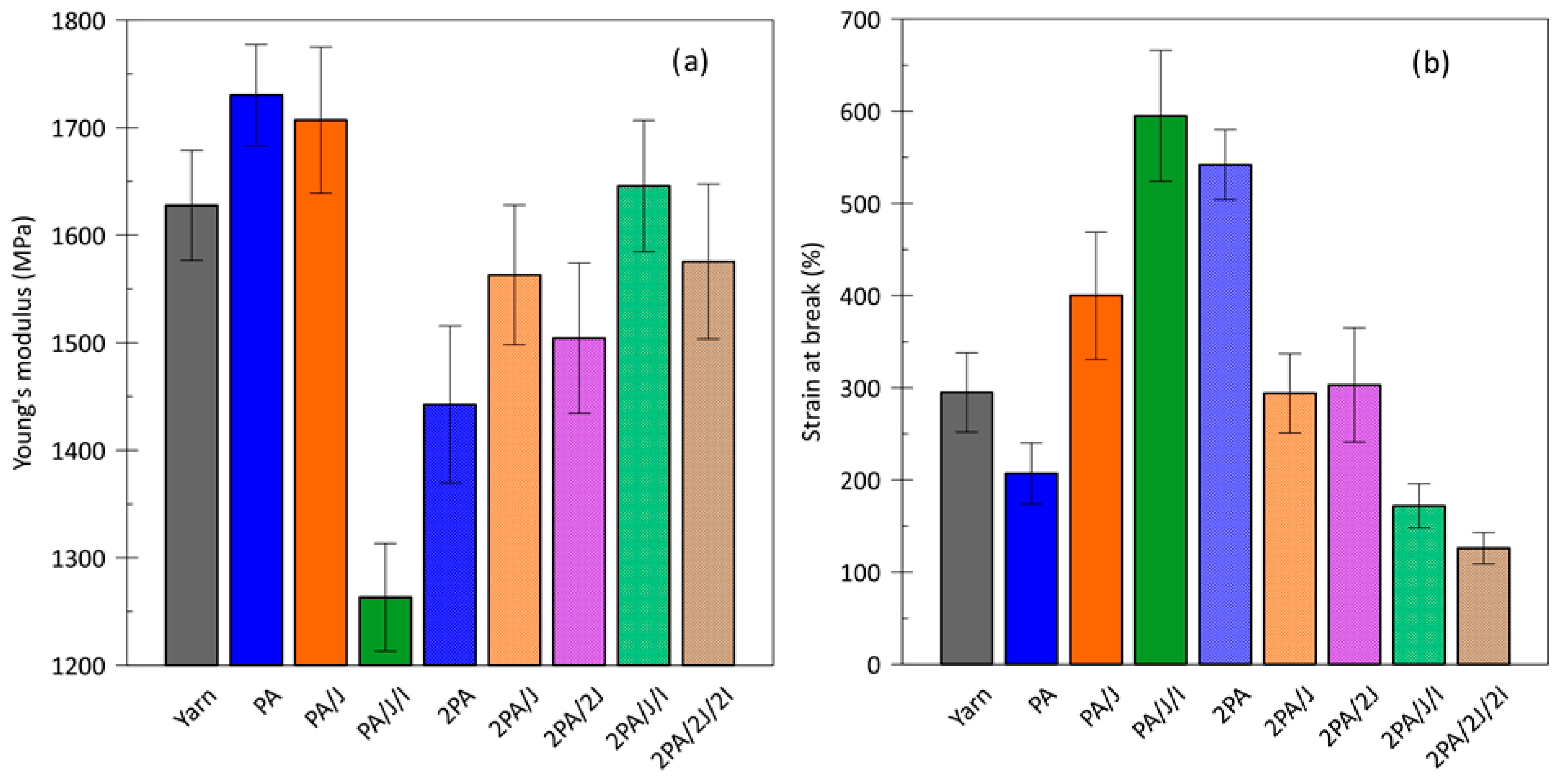

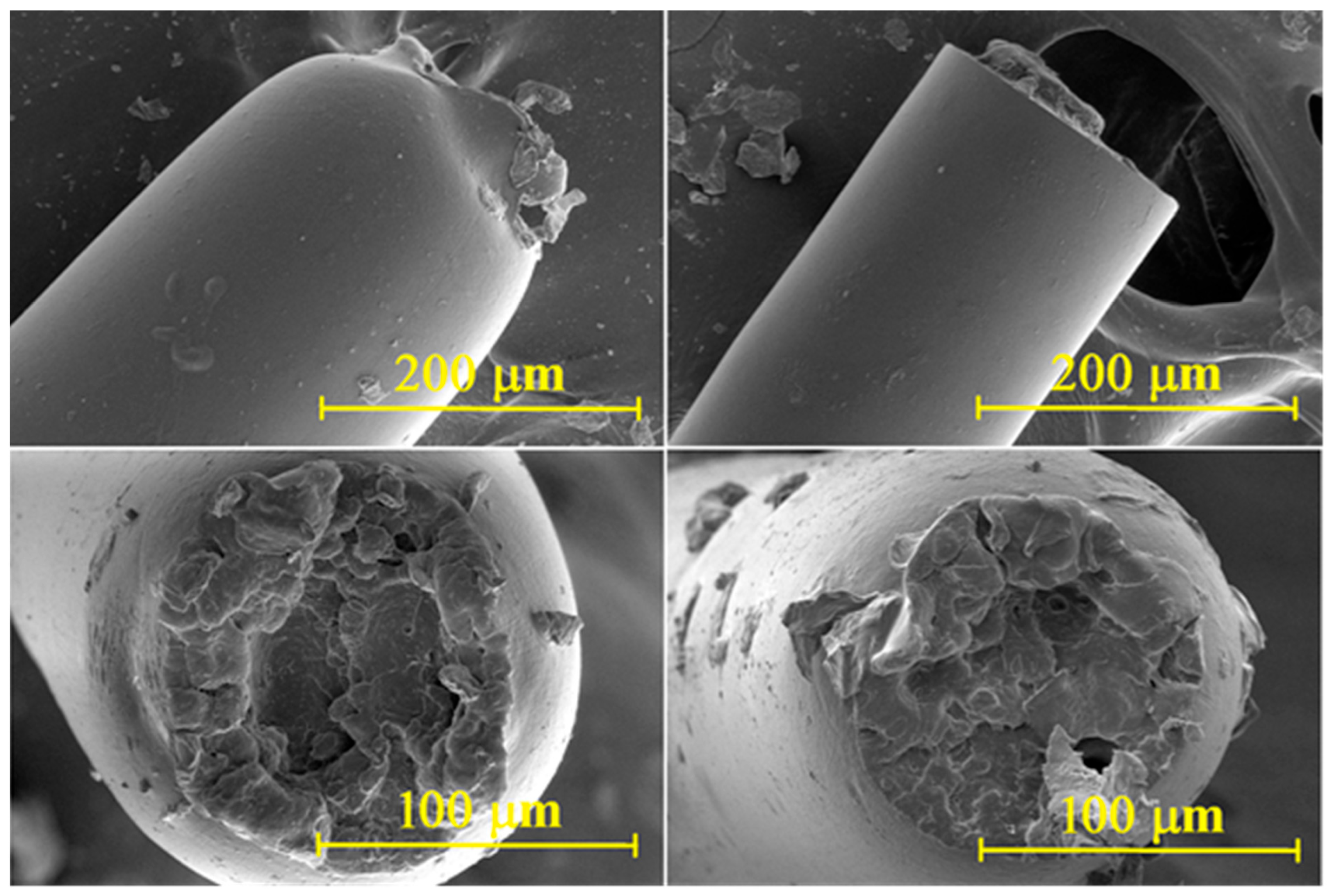

3.6. Mechanical Properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PA66 | Polyamide 66 |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| OOT | Oxidative-onset temperature |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| GC/MS | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| LDPE | Low-density polyethylene |

| HDPE | High-density polyethylene |

| PA | Polyamide |

| D | Diameter |

| L | Length |

| J | Joncryl ADR4468 |

| I | Irganox 1098 |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| RV | Relative viscosity |

| VN | Viscosity number |

| RT | Retention time |

| CP | Cyclopentanone |

References

- Muthu, S.S.; Li, Y.; Hu, J.-Y.; Mok, P.-Y. Recyclability Potential Index (RPI): The Concept and Quantification of RPI for Textile Fibres. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 18, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanga-Labayen, J.P.; Labayen, I.V.; Yuan, Q. A Review on Textile Recycling Practices and Challenges. Textiles 2022, 2, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnambalam, S.G.; Sankaranarayanan, B.; Karuppiah, K.; Thinakaran, S.; Chandravelu, P.; Lam, H.L. Analysing the Barriers Involved in Recycling the Textile Waste in India Using Fuzzy DEMATEL. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmsen, P.; Scheffer, M.; Bos, H. Textiles for Circular Fashion: The Logic behind Recycling Options. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberg, V.; Rodrigue, D. Recycling of Polyamides: Processes and Conditions. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 61, 1937–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Memon, H.A.; Wang, Y.; Marriam, I.; Tebyetekerwa, M. Circular Economy and Sustainability of the Clothing and Textile Industry. Mater. Circ. Econ. 2021, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militký, J.; Venkataraman, M.; Mishra, R. 12—The Chemistry, Manufacture, and Tensile Behavior of Polyamide Fibers. In Handbook of Properties of Textile and Technical Fibres, 2nd ed.; Bunsell, A.R., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 367–419. ISBN 978-0-08-101272-7. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R.; Perez, B.A.; Toraman, H.E. Comparative Analysis of Additive Decomposition Using One-Dimensional and Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography: Part I—Irganox 1010, Irganox 1076, and BHT. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1732, 465243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Kim, M.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Lim, J.; Lee, W.; Kim, H.S.; Cho, D.H.; Lee, J.; Choi, S. Melt Spinnability Comparison of Mechanically and Chemically Recycled Polyamide 6 for Plastic Waste Reuse. Polymers 2024, 16, 3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, K.; Sjöblom, T.; Persson, A.; Kadi, N. Improving Mechanical Textile Recycling by Lubricant Pre-Treatment to Mitigate Length Loss of Fibers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandin, G.; Peters, G.M. Environmental Impact of Textile Reuse and Recycling—A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A. Gaining Benefits from Discarded Textiles: LCA of Different Treatment Pathways; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; ISBN 978-92-893-4658-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tuna, B.; Benkreira, H. Chain Extension of Recycled PA6. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2018, 58, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Guan, B.; Guo, W.; Liu, X. Effect of Antioxidants on Thermo-Oxidative Stability and Aging of Bio-Based PA56T and Fast Characterization of Anti-Oxidation Performance. Polymers 2022, 14, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.R.d.M.; Henrique, M.A.; Luna, C.B.B.; de Carvalho, L.H.; de Almeida, Y.M.B. Influence of a Multifunctional Epoxy Additive on the Performance of Polyamide 6 and PET Post-Consumed Blends During Processing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdmann, R.; Rennert, M.; Meins, T. Influence of Epoxy Functional Chain-Extenders on the Thermal and Rheological Properties of Bio-Based Polyamide 10.10. Polymers 2023, 15, 3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gültürk, C.; Berber, H. Effects of Mechanical Recycling on the Properties of Glass Fiber–Reinforced Polyamide 66 Composites in Automotive Components. E-Polymers 2023, 23, 20230129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 307:2019; Plastics—Polyamides—Determination of Viscosity Number. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.technicke-normy-csn.cz/csn-en-iso-307-643605-212663.html (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Mao, X.; Liu, W.; Li, Z.; Mei, S.; Zong, B. Preparation of an Antibacterial Branched Polyamide 6 via Hydrolytic Ring-Opening Co-Polymerization of ε-Caprolactam and Lysine Derivative. Polymers 2024, 16, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 527-1:2019; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 1: General Principles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/75824.html (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Farias-Aguilar, J.C.; Ramírez-Moreno, M.J.; Téllez-Jurado, L.; Balmori-Ramírez, H. Low Pressure and Low Temperature Synthesis of Polyamide-6 (PA6) Using Na0 as Catalyst. Mater. Lett. 2014, 136, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyaz, A.; Asghar, H.; Waqas, M.; Kamal, A.; Al-Onazi, W.A.; Al-Mohaimeed, A.M. Multi-Spectroscopic Characterization of MgO/Nylon (6/6) Polymer: Evaluating the Potential of LIBS and Statistical Methods. Polymers 2023, 15, 3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, P.P.X.; Yen, Z.; Salim, T.; Lim, H.C.A.; Chung, C.K.; Lam, Y.M. The Impact of Mechanical Recycling on the Degradation of Polyamide. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 225, 110773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umarov, A.V.; Kuchkarov, H.; Kurbanov, M. Study and Analysis of the IR Spectra of a Composition Based on Polyamide Filled with Iron Nanoparticles. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 401, 05085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashaei, S.; Siddaramaiah; Avval, M.M.; Syed, A.A. Thermal Degradation Kinetics of Nylon6/GF/Crysnano Nanoclay Nanocomposites by TGA. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2011, 17, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, A.; Marzullo, F.; Ostrowska, M.; Dotelli, G. Thermal Degradation of Glass Fibre-Reinforced Polyamide 6,6 Composites: Investigation by Accelerated Thermal Ageing. Polymers 2025, 17, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasanthan, N.; Salem, D.R. Infrared Spectroscopic Characterization of Oriented Polyamide 66: Band Assignment and Crystallinity Measurement. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2000, 38, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallner, G.M.; Grabmann, M.K.; Klocker, C.; Buchberger, W.; Nitsche, D. Effect of Carbon Nanotubes on the Global Aging Behavior of β-Nucleated Polypropylene Random Copolymers for Absorbers of Solar-Thermal Collectors. Sol. Energy 2018, 172, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedicke, K.; Wittich, H.; Mehler, C.; Gruber, F.; Altstädt, V. Crystallisation Behaviour of Polyamide-6 and Polyamide-66 Nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2006, 66, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, B.; Kroschwald, L.; Pötschke, P. The Influence of the Blend Ratio in PA6/PA66/MWCNT Blend Composites on the Electrical and Thermal Properties. Polymers 2019, 11, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccella, M.; Dorigato, A.; Pasqualini, E.; Caldara, M.; Fambri, L. Chain Extension Behavior and Thermo-Mechanical Properties of Polyamide 6 Chemically Modified with 1,1′-Carbonyl-Bis-Caprolactam. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2014, 54, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamba-Diogo, O.; Fernagut, F.; Guilment, J.; Pery, F.; Fayolle, B.; Richaud, E. Thermal Stabilization of Polyamide 11 by Phenolic Antioxidants. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 179, 109206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, M.A.; Marchildon, E.K.; McAuley, K.B.; Cunningham, M.F. Thermal Nonoxidative Degradation of Nylon 6,6. J. Macromol. Sci. Part C 2000, 40, 233–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.J.; Orofino, T.A. Nylon 66 Polymers. I. Molecular Weight and Compositional Distribution. J. Polym. Sci. Part A-2 Polym. Phys. 1969, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duemichen, E.; Braun, U.; Kraemer, R.; Deglmann, P.; Senz, R. Thermal Extraction Combined with Thermal Desorption: A Powerful Tool to Investigate the Thermo-Oxidative Degradation of Polyamide 66 Materials. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2015, 115, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.N.; White, G.V.; White, M.I.; Bernstein, R.; Hochrein, J.M. Characterization of Volatile Nylon 6.6 Thermal-Oxidative Degradation Products by Selective Isotopic Labeling and Cryo-GC/MS. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2012, 23, 1579–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hu, H.; Jiang, D.; Du, Y.; Jiang, W.; Wang, H. Identification of Two Polyamides (PA11 and PA1012) Using Pyrolysis-GC/MS and MALDI-TOF MS. Polym. Test. 2013, 32, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, T.; Hajime, O.; Chuichi, W. Part 2—Pyrograms and Thermograms of 163 High Polymers, and MS Data of the Major Pyrolyzates. In Pyrolysis–GC/MS Data Book of Synthetic Polymers; Shin, T., Hajime, O., Chuichi, W., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 7–335. ISBN 978-0-444-53892-5. [Google Scholar]

- Volponi, J. Use of Oxidation Onset Temperature Measurements for Evaluating the Oxidative Degradation of Isotatic Polypropylene. J. Polym. Environ. 2004, 12, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fan, H.; Bai, J.; Liu, X.; Ding, Y.; Yang, M. A Novel Polyhedral Oligomeric Silsesquioxane Antioxidant Based on Amide-Linked Hindered Phenols and Its Anti-Oxidative Behavior in Polyamide 6,6. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 229, 110939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, U.; Khan, Z.I.; Mohamad, Z.B. Compatibility and Miscibility of Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate/Polyamide 11 Blends with and without Joncryl® Compatibilizer: A Comprehensive Study of Mechanical, Thermal, and Thermomechanical Properties. Iran. Polym. J. 2024, 33, 1313–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, B.; Cant, E.; Amel, H.; Jenkins, M. The Effect of Physical Aging and Degradation on the Re-Use of Polyamide 12 in Powder Bed Fusion. Polymers 2022, 14, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Input Material * | No. of Processing Cycles | Additive Type | Additive Dosage (%wt.) | Sample Designation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yarn | 1 | - | - | PA |

| Yarn | 1 | Joncryl | 0.5 | PA/J |

| Yarn | 1 | Joncryl + Irganox | 0.5 + 0.1 | PA/J/I |

| PA | 2 | - | - | 2PA |

| PA/J | 2 | - | - | 2PA/J |

| PA/J | 2 | Joncryl | 0.5 | 2PA/2J |

| PA/J/I | 2 | - | - | 2PA/J/I |

| PA/J/I | 2 | Joncryl + Irganox | 0.5 + 0.1 | 2PA/2J/2I |

| Sample Designation | T10 (°C) | T50 (°C) | Tmax (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yarn | 372 | 410 | 407 |

| PA | 386 | 420 | 426 |

| PA/J | 394 | 422 | 423 |

| PA/J/I | 390 | 420 | 423 |

| 2PA | 386 | 418 | 423 |

| 2PA/J | 390 | 418 | 417 |

| 2PA/2J | 395 | 422 | 423 |

| 2PA/J/I | 392 | 421 | 422 |

| 2PA/2J/2I | 392 | 420 | 422 |

| Samples Designation | Tm (°C) | ΔHm (J/g) | Tc1 (°C) | ΔHc1 (J/g) | Tc2 (°C) | ΔHc2 (J/g) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yarn | 264 | 72.0 | 169 | 6.1 | 235 | 72.5 | 37 |

| PA | 265 | 77.4 | 157 | 5.1 | 234 | 70.0 | 40 |

| PA/J | 265 | 80.3 | 161 | 5.3 | 235 | 71.3 | 41 |

| PA/J/I | 264 | 67.0 | 169 | 3.3 | 235 | 72.6 | 34 |

| 2PA | 264 | 74.8 | 172 | 3.6 | 236 | 71.9 | 38 |

| 2PA/J | 265 | 71.2 | 167 | 9.7 | 235 | 70.6 | 36 |

| 2PA/2J | 264 | 73.4 | 159 | 7.1 | 235 | 71.6 | 38 |

| 2PA/J/I | 264 | 62.0 | 166 | 10.7 | 235 | 53.1 | 32 |

| 2PA/2J/2I | 264 | 65.8 | 163 | 9.1 | 234 | 68.6 | 34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Drohsler, P.; Pummerova, M.; Hanusova, D.; Sanetrnik, D.; Foldynova, D.; Marek, J.; Martinkova, L.; Sedlarik, V. A Method for Mitigating Degradation Effects on Polyamide Textile Yarn During Mechanical Recycling. Polymers 2025, 17, 3243. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243243

Drohsler P, Pummerova M, Hanusova D, Sanetrnik D, Foldynova D, Marek J, Martinkova L, Sedlarik V. A Method for Mitigating Degradation Effects on Polyamide Textile Yarn During Mechanical Recycling. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3243. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243243

Chicago/Turabian StyleDrohsler, Petra, Martina Pummerova, Dominika Hanusova, Daniel Sanetrnik, Dagmar Foldynova, Jan Marek, Lenka Martinkova, and Vladimir Sedlarik. 2025. "A Method for Mitigating Degradation Effects on Polyamide Textile Yarn During Mechanical Recycling" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3243. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243243

APA StyleDrohsler, P., Pummerova, M., Hanusova, D., Sanetrnik, D., Foldynova, D., Marek, J., Martinkova, L., & Sedlarik, V. (2025). A Method for Mitigating Degradation Effects on Polyamide Textile Yarn During Mechanical Recycling. Polymers, 17(24), 3243. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243243