Statistical Optimization of Graphene Nanoplatelet-Reinforced Epoxy Nanocomposites via Box–Behnken Design for Superior Flexural and Dynamic Mechanical Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Nanocomposite Preparation

2.2.2. Experimental Design

2.2.3. Nanocomposite Characterization

Mechanical Behavior

Thermal Behavior

Dynamic Behavior

Morphological and Structural Analysis

Chemical Properties

3. Results and Discussion

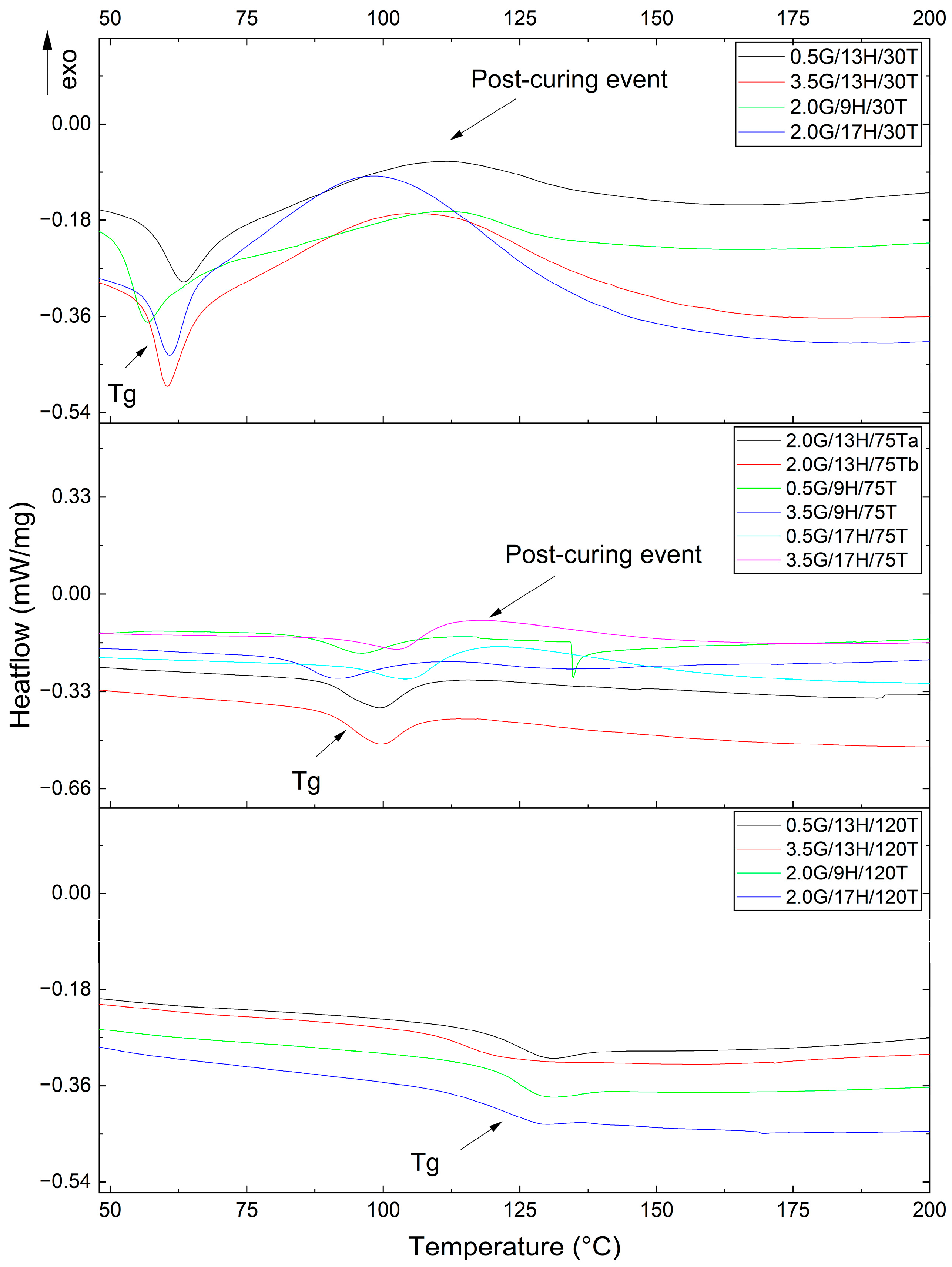

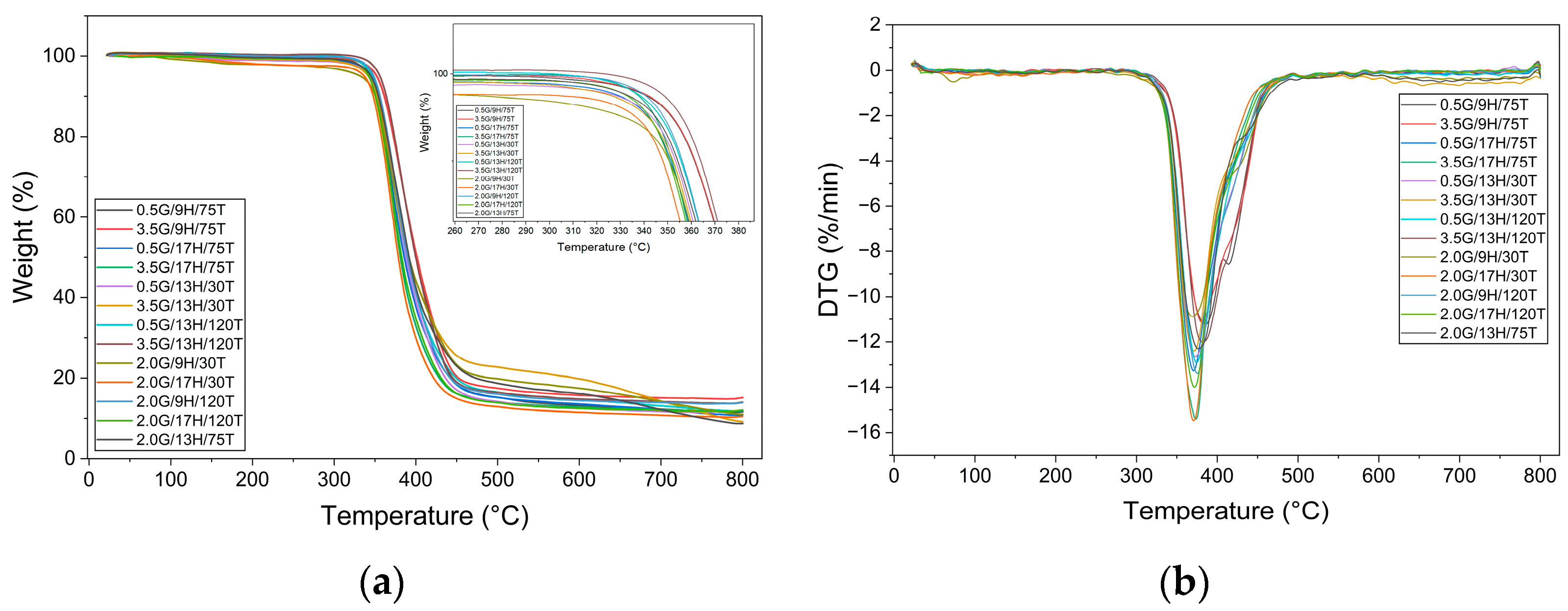

3.1. Thermal Behavior

3.2. Mechanical Behavior

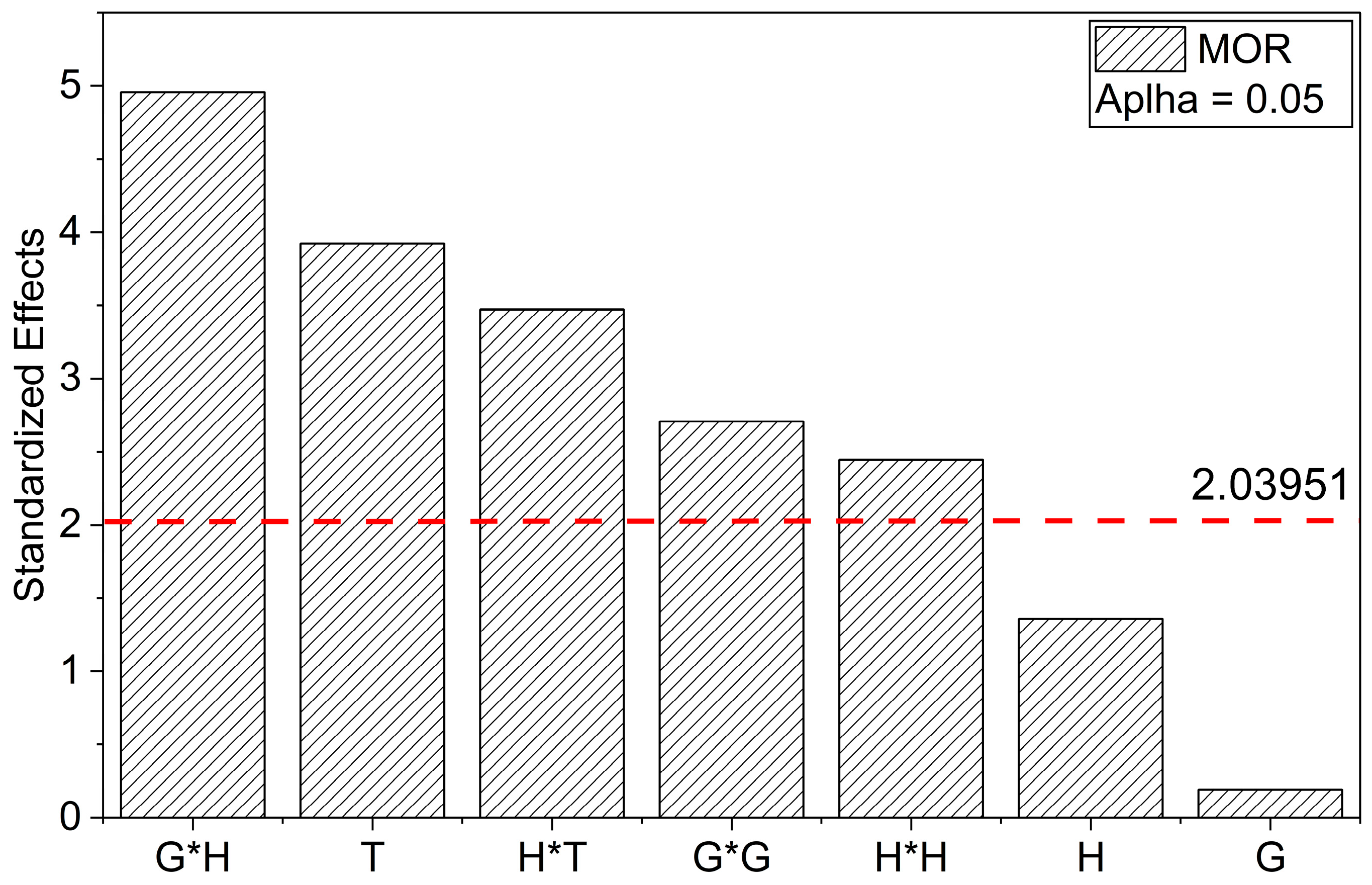

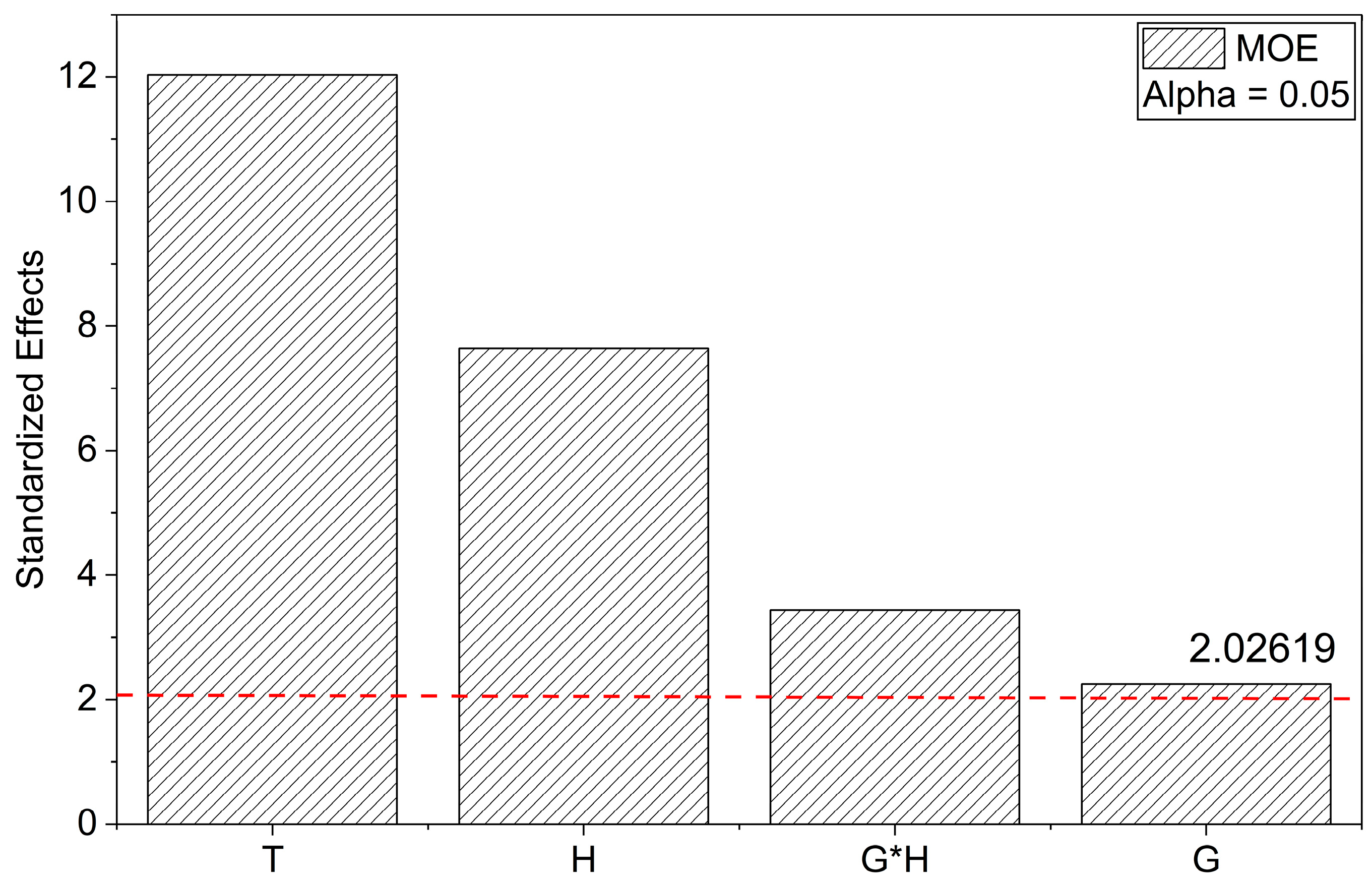

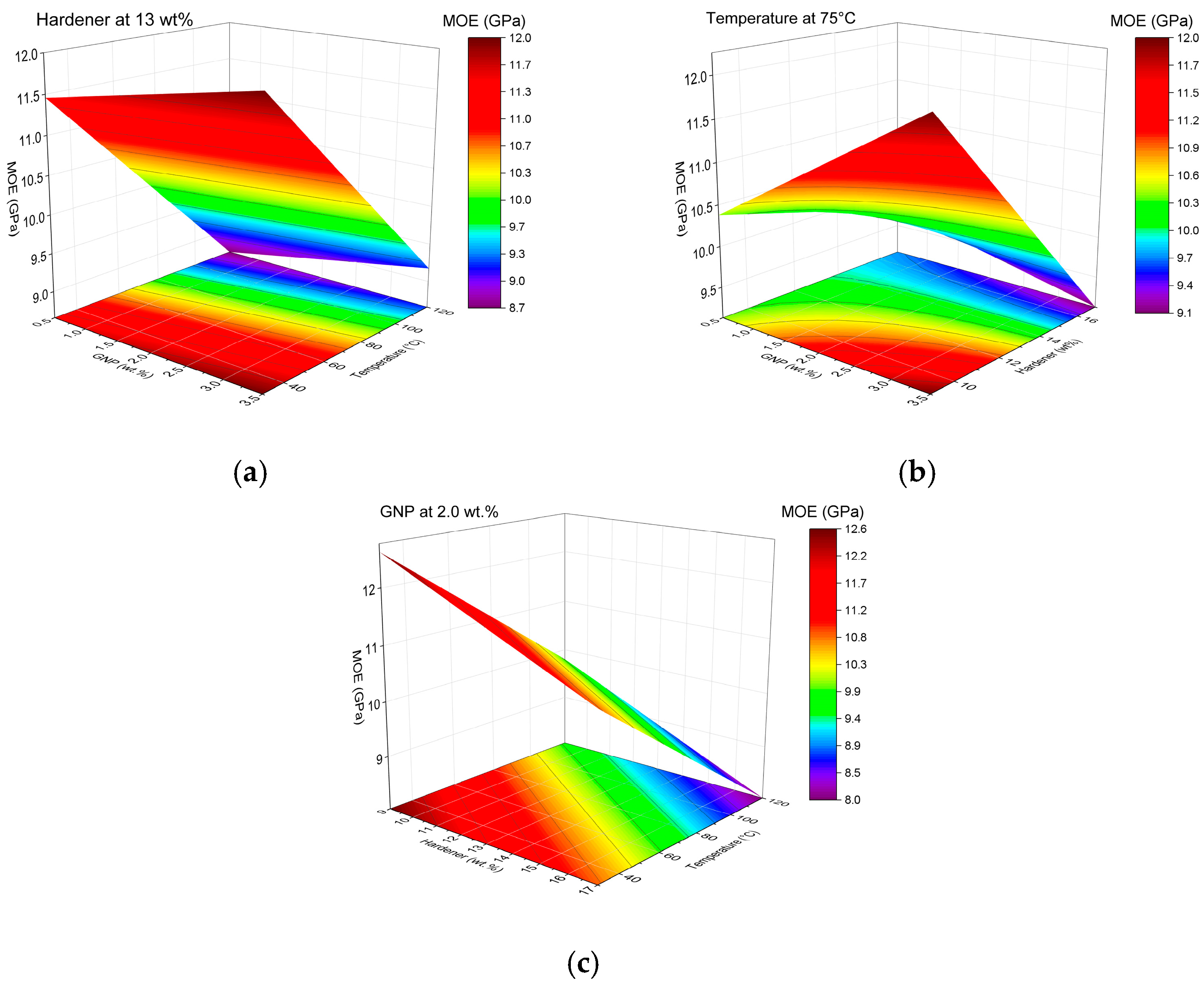

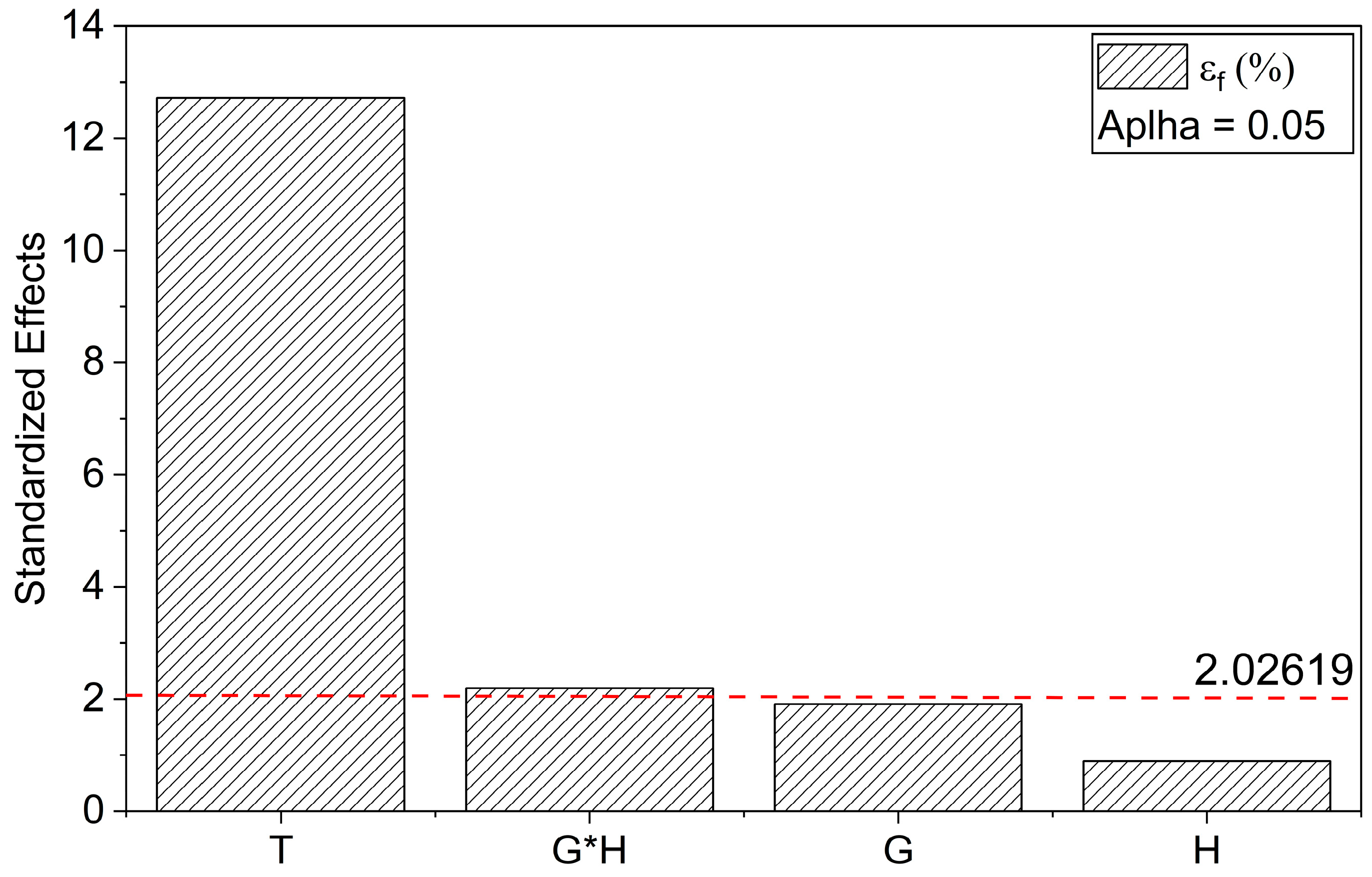

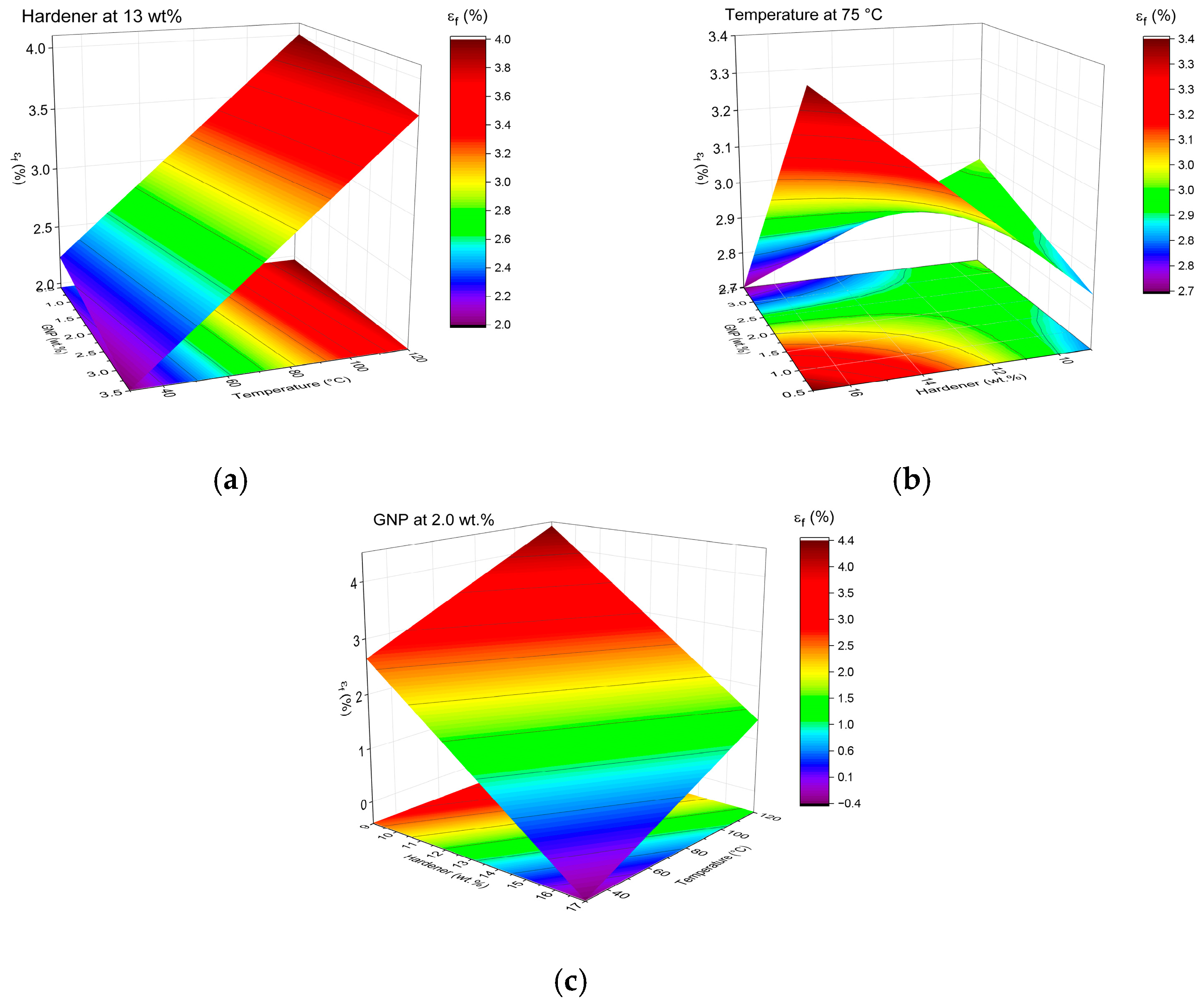

Flexural Properties

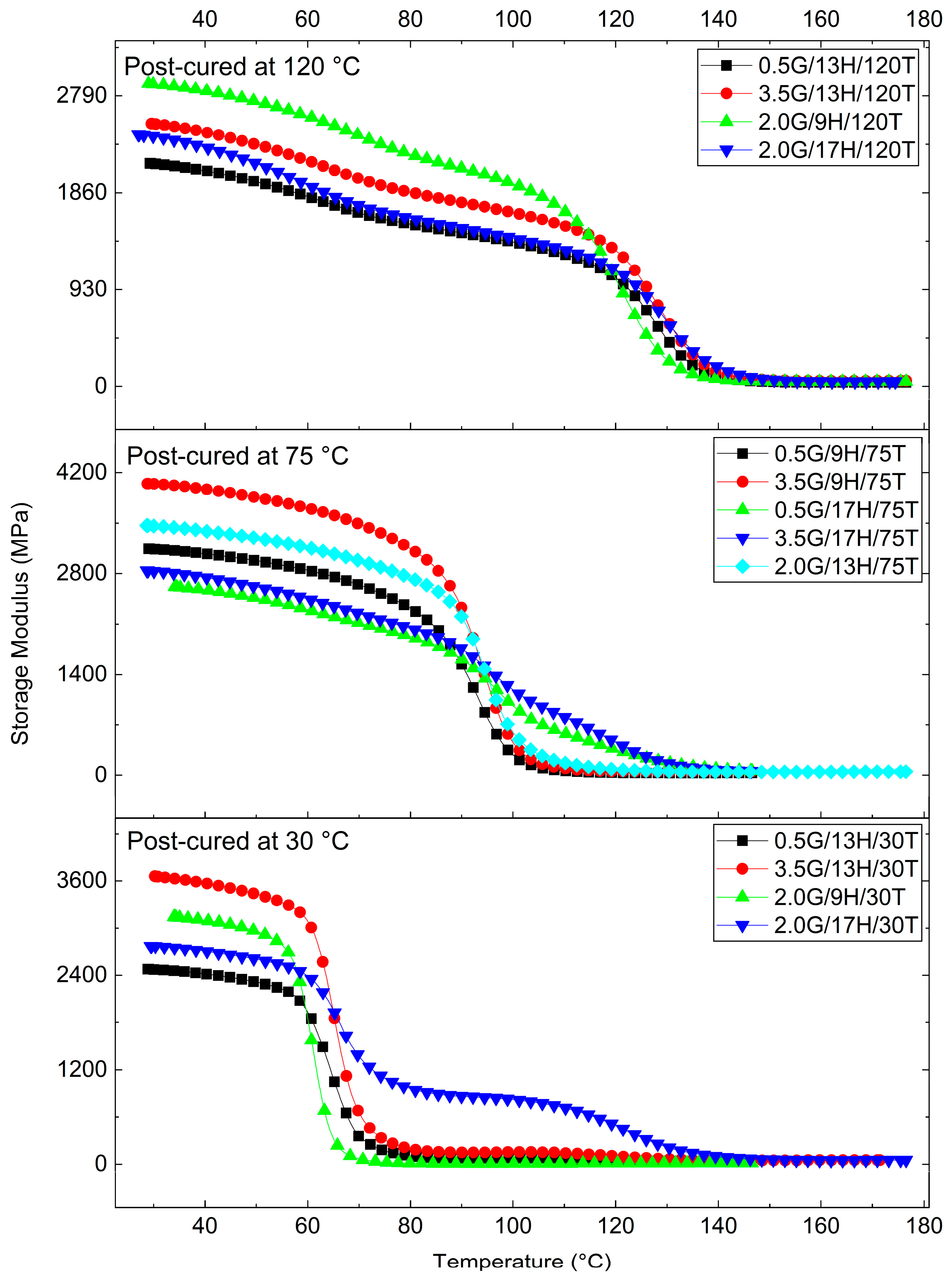

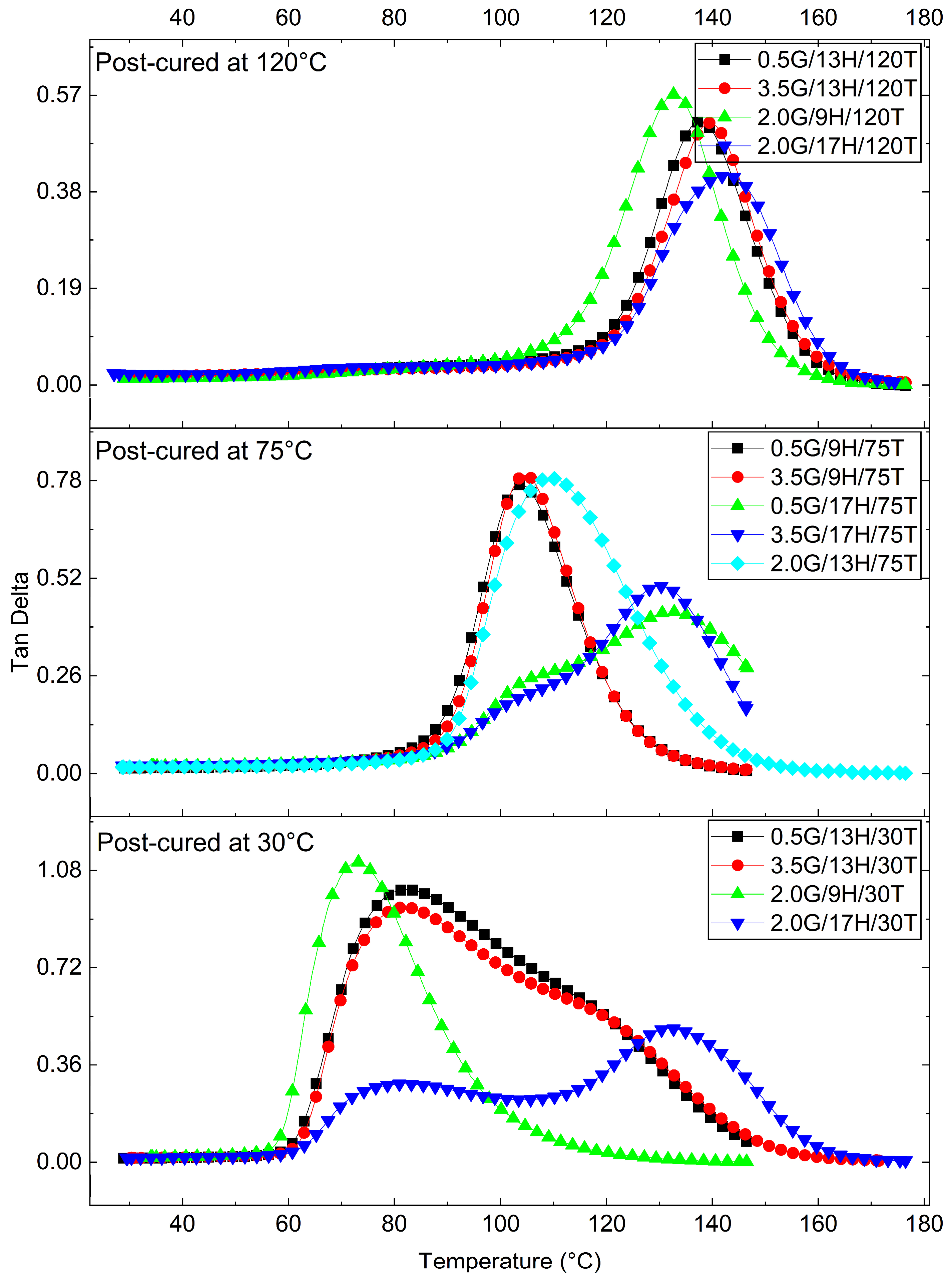

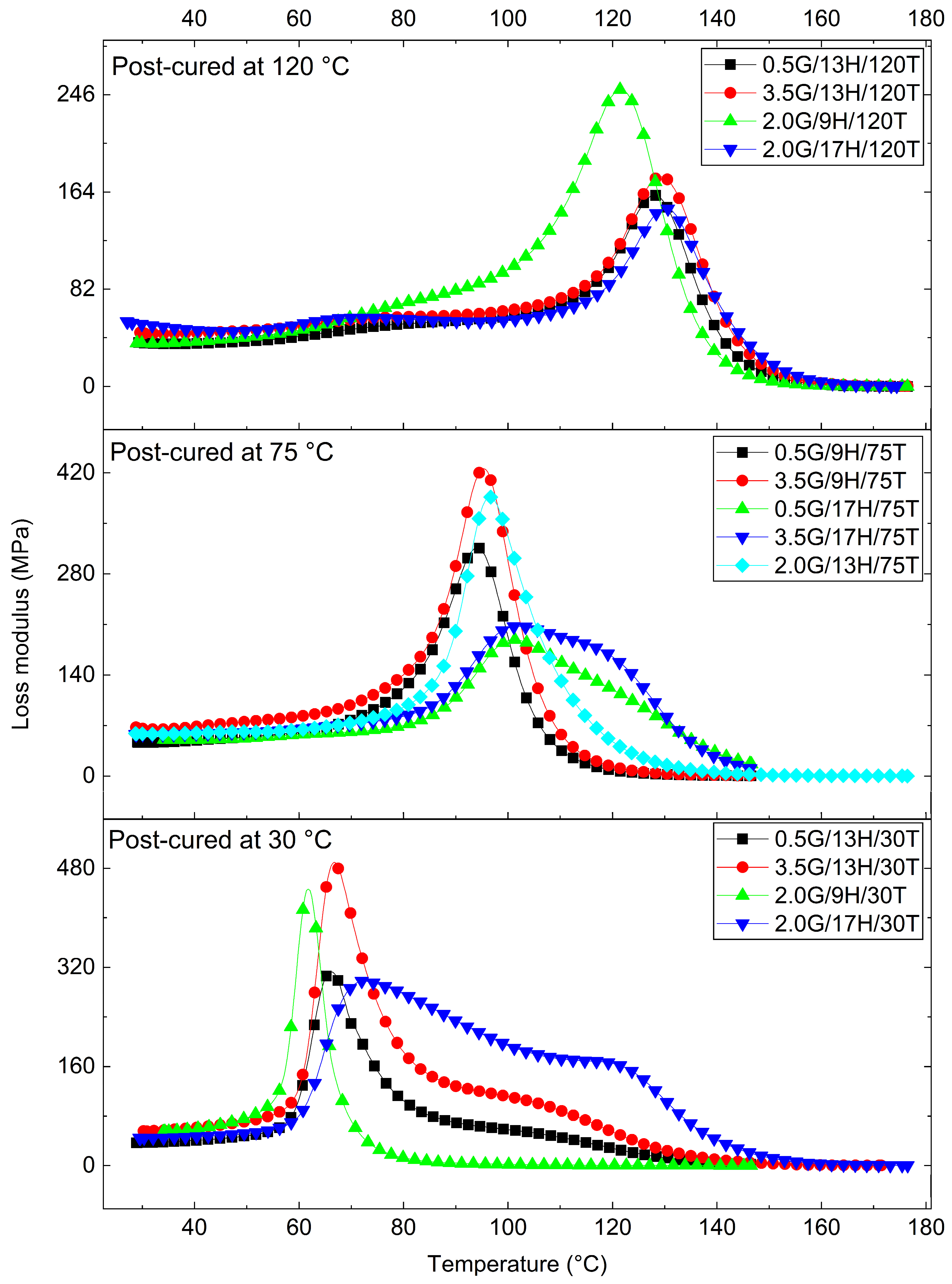

3.3. Viscoelastic Behavior of the GNP-Reinforced Epoxy Nanocomposites

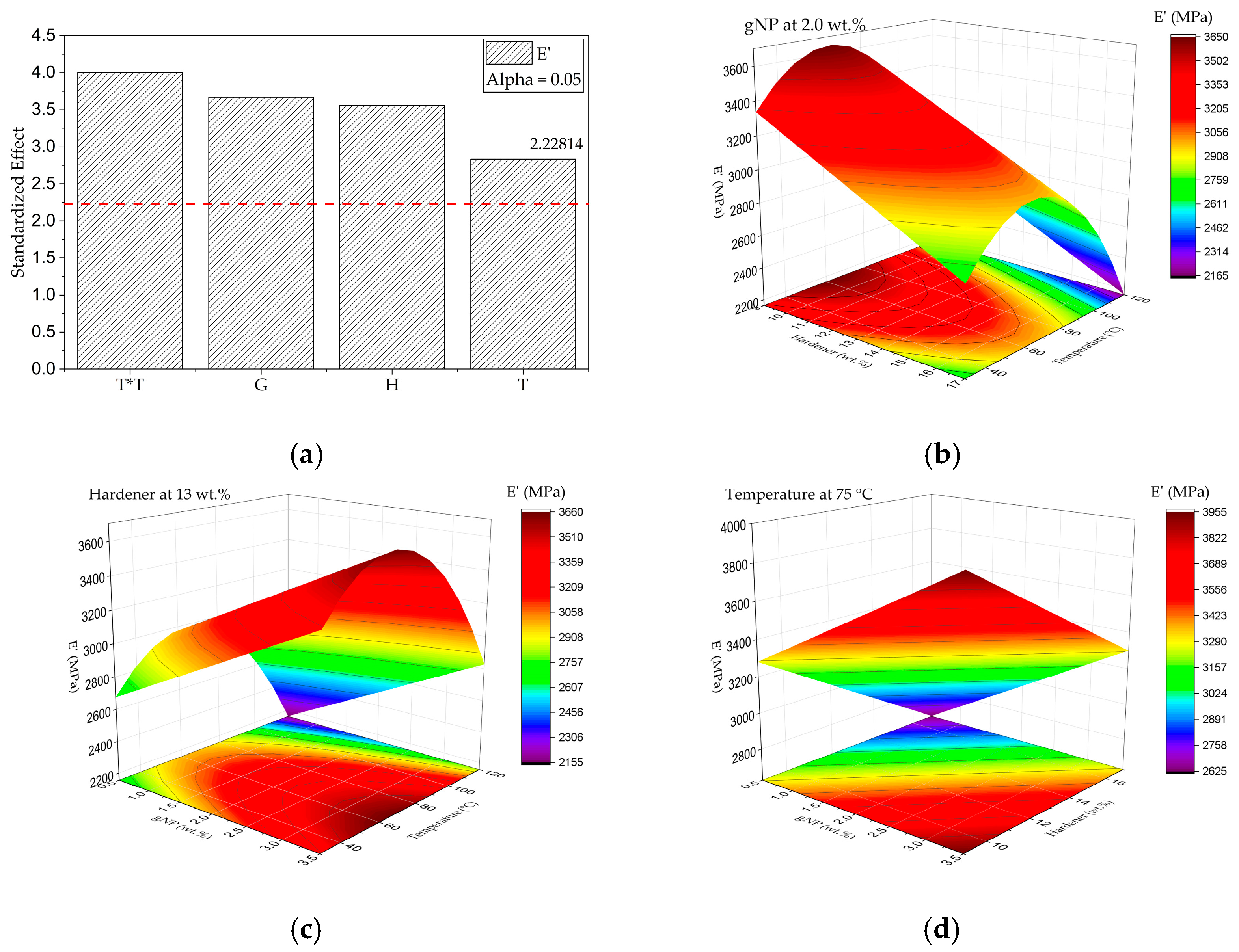

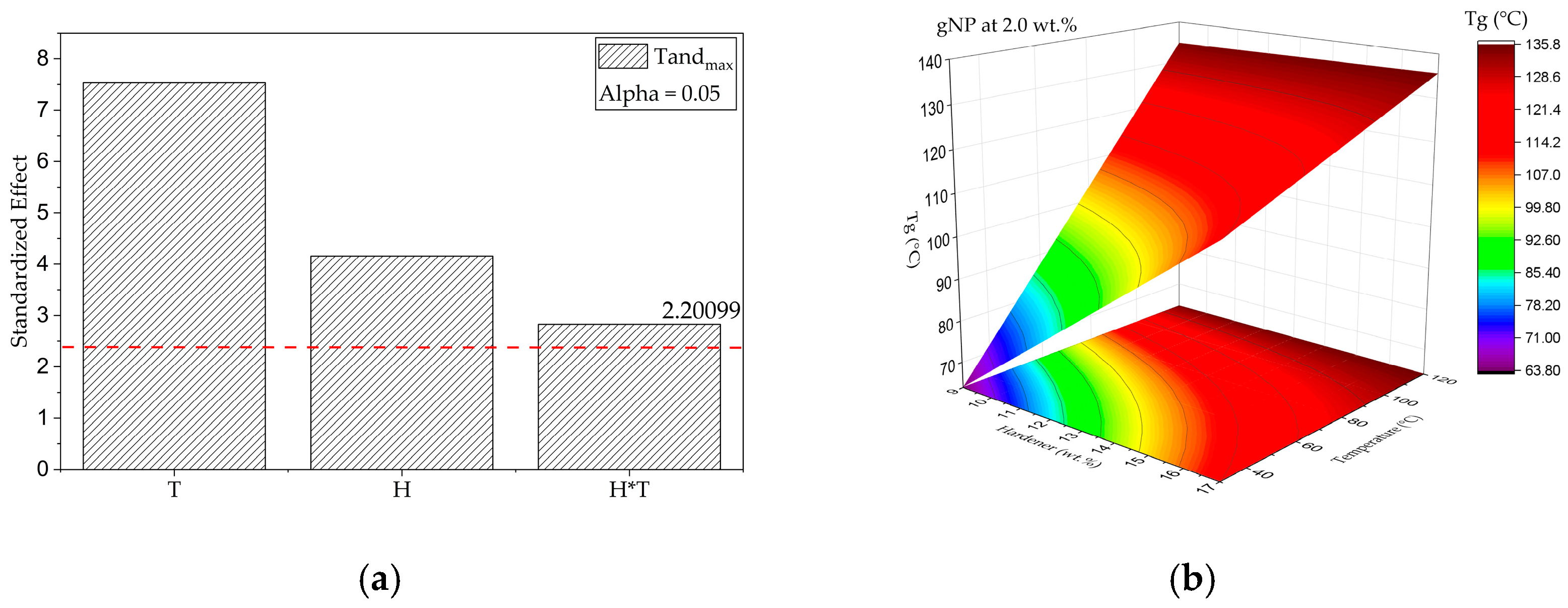

Response Surface Analysis of Dynamic Mechanical Parameters (E′ and tanδ)

- Effect of G, H, and T on E′ (30 °C)

- Effect of G, H, and T on Tg (DMA)

3.4. Morphological Characterization

- Crack deflection and branching, which increase the effective fracture surface area;

- Graphene pull-out and interfacial debonding, absorbing additional fracture energy;

- Plastic deformation in the epoxy matrix adjacent to graphene platelets, induced by strong interfacial adhesion;

- Crack pinning, where nanoplatelets act as barriers to crack propagation, creating tortuous crack paths and enhancing resistance to crack growth.

3.5. Chemical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sabet, M. Unveiling transformative potential: Recent advances in graphene-based polymer composites. Iran. Polym. J. 2024, 33, 1651–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.J.; Yan, Y.N.; Zhou, Y.; Qi, Z.J.; Li, Y.F.; Chen, C.M. Thermal properties of graphene and graphene-based nanocomposites: A review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 8445–8463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, J.; Channa, I.A.; Memon, A.G.; Chandio, I.A.; Chandio, A.D.; Shar, M.A.; Alsalhi, M.S.; Devanesan, S. Enhancement of thermal and gas barrier properties of graphene-based nanocomposite films. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 41054–41063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danial, W.H.; Abdul Majid, Z. Recent advances on the enhanced thermal conductivity of graphene nanoplatelets composites: A short review. Carbon Lett. 2022, 32, 1411–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilisik, K.; Akter, M. Graphene nanoplatelets/epoxy nanocomposites: A review on functionalization, characterization techniques, properties, and applications. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2022, 41, 99–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, M.N.; Norddin, M.M.; Ismail, I.; Rasol, A.A.; Risal, A.R.; Yakasai, F.; Oseh, J.O.; Ngouangna, E.N.; Younas, R.; Ridzuan, N.; et al. Graphene nanoplatelet surface modification for rheological properties enhancement in drilling fluid operations: A review. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 7751–7781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, O.A.; Ndou, N. Synergy of hybrid fillers for emerging composite and nanocomposite materials—A review. Polymers 2024, 16, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, M.; Ozdemir, H.; Bilisik, K. Epoxy/graphene nanoplatelet (GNP) nanocomposites: An experimental study on tensile, compressive, and thermal properties. Polymers 2024, 16, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, N.A.; Ahmad, S.H.; Chen, R.S.; Mohammad, N.E. Mechanical performance and thermal stability of modified epoxy nanocomposite with low loading of graphene platelets. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, J.; Sapuan, S.M.; Rashid, U.; Ilyas, R.A.; Hassan, M.R. Thermal, mechanical, thermo-mechanical and morphological properties of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced green epoxy nanocomposites. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 1998–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkefli, N.A.; Mustapha, R.; Jusoh, S.M.; Awang, M.; Ghazali, C.M.; Mustapha, S.N. The influence of different graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs) loadings on mechanical and thermal behavior of epoxidized palm oil–epoxy resin nanocomposites. AIP Conf. Proc. 2025, 3310, 070002. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Atif, R.; Vo, T.; Inam, F. Graphene nanoplatelets in epoxy system: Dispersion, reaggregation, and mechanical properties of nanocomposites. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015, 561742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustina, E.; Goak, J.C.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.; Hong, S.C.; Seo, Y.; Lee, N. Effect of graphite nanoplatelet size and dispersion on the thermal and mechanical properties of epoxy-based nanocomposites. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junid, R.; Siregar, J.P.; Endot, N.A.; Razak, J.A.; Wilkinson, A.N. Optimization of glass transition temperature and pot life of epoxy blends using response surface methodology (RSM). Polymers 2021, 13, 3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La, L.B.; Nguyen, H.; Tran, L.C.; Su, X.; Meng, Q.; Kuan, H.C.; Ma, J. Exfoliation and dispersion of graphene nanoplatelets for epoxy nanocomposites. Adv. Nanocomposites 2024, 1, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Ferreira, D.P.; Araújo, J.C.; Ferreira, A.; Fangueiro, R. The potential of graphene nanoplatelets in the development of smart and multifunctional ecocomposites. Polymers 2020, 12, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, B.; Gajević, S.; Kostić, N.; Miladinović, S.; Vencl, A. Optimization of parameters that affect wear of A356/Al2O3 nanocomposites using RSM, ANN, GA and PSO methods. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 2022, 74, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, Y.; Raza, H.; Ahmed, A.; Quazi, M.M.; Jamshaid, M.; Anwar, M.T.; Bashir, M.N.; Younas, T.; Jafry, A.T.; Soudagar, M.E. Integration of response surface methodology (RSM), machine learning (ML), and artificial intelligence (AI) for enhancing properties of polymeric nanocomposites—A review. Polym. Compos. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shettar, M.; Doshi, M.; Rawat, A.K. Study on mechanical properties and water uptake of polyester–nanoclay nanocomposite and analysis of wear property using RSM. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 1618–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.Z.; Shah, S.Z.; Megat-Yusoff, P.S.; Choudhry, R.S.; Ahmad, F.; Hussnain, S.M. Toughening epoxy resin system using nano-structured block copolymer and graphene nanoplatelets to mitigate matrix microcracks in epoxy nanocomposites: A DoE-based framework. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 43, 111697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D790-17; Standard Test Methods for Flexural Properties of Unreinforced and Reinforced Plastics and Electrical Insulating Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM E1131-20; Standard Test Method for Compositional Analysis by Thermogravimetry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D7028-08; Standard Test Method for Glass Transition Temperature (DMA Tg) of Polymer Matrix Composites by Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008.

- Monteserín, C.; Blanco, M.; Aranzabe, E.; Aranzabe, A.; Laza, J.; Larrañaga-Varga, A.; Vilas, J. Effects of Graphene Oxide and Chemically-Reduced Graphene Oxide on the Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Epoxy Amine Composites. Polymers 2017, 9, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Son, S.; Heo, S.; Seong, D. Investigation on the optimized curing cycle of epoxy resin for enhancing thermal and mechanical properties of glass fiber reinforced plastic applications. Funct. Compos. Struct. 2025, 7, 015007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, J.; Berry, R.; Foster, H. On the Nature of Epoxy Resin Post-Curing. Polymers 2020, 12, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonahal, M.; Saeb, M.R.; Jafari, S.H.; Rastin, H.; Khonakdar, H.A.; Najafi, F.; Simon, F. Design, preparation, and characterization of fast cure epoxy/amine-functionalized graphene oxide nanocomposites. Polym. Compos. 2018, 39, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cui, X.; Qin, J.; Shi, M.; Wang, D.; Yang, L.; Lyu, M.; Liang, L. Ultra-high cross-linked active ester-cured epoxy resins: Side group cross-linking for performance enhancement. Polymer 2024, 301, 127063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhao, G.; Shi, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Ren, S. Effect of crosslink structure on mechanical properties, thermal stability and flame retardancy of natural flavonoid based epoxy resins. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 162, 110898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabill, F.; Ayoob, R.; Andritsch, T.; Vaughan, A. Effect of resin/hardener stoichiometry on electrical behavior of epoxy networks. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2017, 24, 3739–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, M.; Shundo, A.; Kuwahara, R.; Yamamoto, S.; Tanaka, K. Mesoscopic Heterogeneity in the Curing Process of an Epoxy–Amine System. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 2075–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.G.; Soares, B.G.; Pita, V.J.; Sánchez, R.; Rieumont, J. Mechanical properties of epoxy networks based on DGEBA and aliphatic amines. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 106, 2047–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascano, D.; Quiles-Carrillo, L.; Torres-Giner, S.; Boronat, T.; Montanes, N. Optimization of the Curing and Post-Curing Conditions for the Manufacturing of Partially Bio-Based Epoxy Resins with Improved Toughness. Polymers 2019, 11, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.V.; Brito, F.S.; Franceschi, W.; Simonetti, E.A.N.; Cividanes, L.S.; Chipara, M.; Lozano, K. Functionalized graphene oxide as reinforcement in epoxy based nanocomposites. Surf. Interfaces 2018, 10, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, U.O.; Nascimento, L.F.; Garcia, J.M.; Bezerra, W.B.; Monteiro, S.N. Evaluation of Izod impact and bend properties of epoxy composites reinforced with mallow fibers. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheith, M.; Aziz, M.; Ghori, W.; Saba, N.; Asim, M.; Jawaid, M.; Alothman, O. Flexural, thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of date palm fibres reinforced epoxy composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, F.; Wu, X.; Huang, W.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Influence of gamma irradiation on the molecular dynamics and mechanical properties of epoxy resin. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 168, 108940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Varshney, D.; Sreenivasa, S.; N, B.; Karthikeyan, A. Comparison of the tensile and flexural properties of epoxy nanocomposites reinforced by graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, S835–S845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Afroj, S.; Karim, N. Toward sustainable composites: Graphene-modified jute fiber composites with bio-based epoxy resin. Glob. Chall. 2023, 7, 2300111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, M.; Drzal, L. Surface modification of bamboo fiber with sodium hydroxide and graphene oxide in epoxy composites. Polym. Compos. 2021, 42, 1135–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Luz, F.S.; Garcia Filho, F.D.C.; Del-Río, M.T.G.; Nascimento, L.F.C.; Pinheiro, W.A.; Monteiro, S.N. Graphene-incorporated natural fiber polymer composites: A first overview. Polymers 2020, 12, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelar, M.; Suryawanshi, V.; Wayzode, N. Tensile and flexural behavior of graphene-reinforced carbon/epoxy composites manufactured via compression molding method. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 15891–15900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Tang, B.; Liu, K.; Zeng, X.; Lu, J.; Zhang, T.; Shen, X. Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2019, 8, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaftelen-Odabaşi, H.; Odabaşi, A.; Özdemir, M.; Baydoğan, M. A study on graphene reinforced carbon fiber epoxy composites: Investigation of electrical, flexural, and dynamic mechanical properties. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Shah, S.; Megat-Yusoff, P.; Choudhry, R.; Sharif, T.; Hussnain, S. Optimizing flexural performance of 3D fibre-reinforced composites with hybrid nano-fillers using response surface methodology (RSM). Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2025, 190, 108713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Lu, H.; Yang, Y. Constructing hierarchically structured interphases for strong and tough epoxy nanocomposites by amine-rich graphene surfaces. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 9635–9643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Sun, X.; Lin, X.; Shen, X.; Mai, Y.W.; Kim, J.K. Exceptional electrical conductivity and fracture resistance of 3D interconnected graphene foam/epoxy composites. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 5774–5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Fan, X.; Zhu, C.; Yao, X.; Liu, Z. Mechanical and thermal properties of epoxy resin nanocomposites reinforced with graphene oxide. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2012, 51, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, H.B.; Mahamuni, S.S.; Gaikwad, P.M.; Pula, M.A.; Mahamuni, S.; Bansode, S.H.; Nehatrao, S.A. Enhanced mechanical properties of epoxy/graphite composites. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Stud. 2017, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gouda, K.; Bhowmik, S.; Das, B. Thermomechanical behavior of graphene nanoplatelets and bamboo micro filler incorporated epoxy hybrid composites. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 015328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, K.; Dixit, A.R. A review of the mechanical and thermal properties of graphene and its hybrid polymer nanocomposites for structural applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 5992–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, M.R.V.; Silva, B.L.; Opelt, C.V.; Coelho, L.A.F. Effect of graphene nanoparticle dispersion on the cure and mechanical properties of a 3D printing resin. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 13088–13102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K.H.; Mohamad, Z.; Khan, Z.I. Influence of graphene nanoplatelets and post-curing conditions on the mechanical and viscoelastic properties of stereolithography 3D-printed nanocomposites. Polymers 2024, 16, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Weng, G.J. Uncovering the glass-transition temperature and temperature-dependent storage modulus of graphene-polymer nanocomposites through irreversible thermodynamic processes. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2021, 158, 103411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelov, B.; Mischanchuk, O.; Sigareva, N.; Shulga, S.; Gorb, A.; Polovina, O.; Yukhymchuk, V. Structural and Dipole-Relaxation Processes in Epoxy–Multilayer Graphene Composites with Low Filler Content. Polymers 2021, 13, 3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awwad, K.; Yousif, B.; Fallahnezhad, K.; Saleh, K.; Zeng, X. Influence of graphene nanoplatelets on mechanical properties and adhesive wear performance of epoxy-based composites. Friction 2020, 9, 856–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijerathne, D.; Gong, Y.; Afroj, S.; Karim, N.; Abeykoon, C. Mechanical and thermal properties of graphene nanoplatelets-reinforced recycled polycarbonate composites. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2023, 6, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazik, M.; Sultan, M.; Jawaid, M.; Talib, A.; Mazlan, N.; Shah, A.; Safri, S. Effect of nanofiller content on dynamic mechanical and thermal properties of multi-walled carbon nanotube and montmorillonite nanoclay filler hybrid shape memory epoxy composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Hoa, S.; Ma, M.; Tong, T. Effects of composition of hardener on the curing and aging for an epoxy resin system. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 99, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Phan, N.; Kihara, K.; Shundo, A.; Tanaka, K. Off-stoichiometry effect on the physical properties of epoxy resins. Polym. J. 2025, 57, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prolongo, M.; Salom, C.; Arribas, C.; Sánchez-Cabezudo, M.; Masegosa, R.; Prolongo, S. Influence of graphene nanoplatelets on curing and mechanical properties of graphene/epoxy nanocomposites. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 125, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, F.A.; Vitorazi, L.; Checca Huaman, N.R.; Monteiro, S.N.; Gómez-del Río, T.; Costa, U.O. Development and characterization of graphene-reinforced epoxy nanocomposites optimized via Box–Behnken design. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 3137–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Akram, S.; Kanellopoulos, A.; Elmarakbi, A.; Karagiannidis, P. Development of new graphene/epoxy nanocomposites and study of cure kinetics, thermal and mechanical properties. Thermochim. Acta 2020, 694, 178785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netkueakul, W.; Tarat, A.; Jitrwung, R.; Sahakaro, K.; Suwanmala, P.; Chiarakorn, S. Release of Graphene-Related Materials from Epoxy-Based Composites: Characterization, Quantification and Hazard Assessment In Vitro. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 10703–10722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Li, S.; Roy, S.; King, J.A.; Odegard, G.M. Fracture properties of nanographene reinforced EPON 862 thermoset polymer system. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2015, 114, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabihi, O.; Ahmadi, M.; Abdollahi, T.; Nikafshar, S.; Naebe, M. Collision-Induced Activation: Towards Industrially Scalable Approach to Graphite Nanoplatelets Functionalization for Superior Polymer Nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, S.-S.; Ma, C.-L.; Jin, F.-L.; Park, S.-J. Fracture Toughness Enhancement of Epoxy Resin Reinforced with Graphene Nanoplatelets and Carbon Nanotubes. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 37, 2075–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, H.M.; Hinder, S.J.; Taylor, A.C. Graphene Nanoplatelet-Modified Epoxy: Effect of Aspect Ratio and Surface Functionality on Mechanical Properties and Toughening Mechanisms. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 8764–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoramishad, H.; Ebrahimijamal, M.; Fasihi, M. The Effect of Graphene Oxide Nano-Platelets on Fracture Behavior of Adhesively Bonded Joints. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2017, 40, 1905–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Soutis, C.; Gresil, M. Fracture Toughness of Hybrid Carbon Fibre/Epoxy Enhanced by Graphene and Carbon Nanotubes. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2021, 28, 1111–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi-Moghadam, B.; Sharafimasooleh, M.; Shadlou, S.; Taheri, F. Effect of functionalization of graphene nanoplatelets on the mechanical response of graphene/epoxy composites. Mater. Des. 2015, 66, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotti, A.; Arcaro, S.; Causin, V.; Pegoretti, A. Effect of the Mixing Technique of Graphene Nanoplatelets and Graphene Nanofibers on Fracture Toughness of Epoxy-Based Nanocomposites and Composites. Polymers 2022, 14, 5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, N.D.; Paragkamian, Z.; Poulin, P.; Kourkoulis, S.K. Fracture related mechanical properties of low and high graphene reinforcement of epoxy nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2017, 150, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatenko, V.Y.; Ilyin, S.O.; Kostyuk, A.V.; Bondarenko, G.N.; Antonov, S.V. Acceleration of epoxy resin curing by using a combination of aliphatic and aromatic amines. Polym. Bull. 2020, 77, 1519–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Zhang, B.; Sun, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Song, C. Morphology, thermal and mechanical properties of epoxy adhesives containing well-dispersed graphene oxide. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2019, 88, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švajdlenková, H.; Kleinová, A.; Šauša, O.; Rusnák, J.; Dung, T.A.; Koch, T.; Knaack, P. Microstructural study of epoxy-based thermosets prepared by “classical” and cationic frontal polymerization. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 41098–41109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancoko, M.; Nuri, H.L.; Prasetyo, A.; Manaf, A.; Jami, A.; Yanto, A.R.; Suntoro, A. Characterization and performance evaluation of epoxy-based plastic scintillators for gamma ray detection. Front. Phys. 2024, 12, 1289759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vryonis, O.; Virtanen, S.T.; Andritsch, T.; Vaughan, A.S.; Lewin, P.L. Understanding the cross-linking reactions in highly oxidized graphene/epoxy nanocomposite systems. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 3035–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ci | GNP Content (G) (wt.%) | Hardener Content (H) (wt.%) | Post-Curing Temperature (T) (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0.5 | 9 | 30 |

| 0 | 2.0 | 13 | 70 |

| +1 | 3.5 | 17 | 120 |

| Coded Parameters | Uncoded Parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | G | H | T | G | H | T | Nomenclature |

| 1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0.5 | 9 | 75 | 0.5G/9H/75T |

| 2 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 3.5 | 9 | 75 | 3.5G/9H/75T |

| 3 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 17 | 75 | 0.5G/17H/75T |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3.5 | 17 | 75 | 3.5G/17H/75T |

| 5 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0.5 | 13 | 30 | 0.5G/13H/30T |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 3.5 | 13 | 30 | 3.5G/13H/30T |

| 7 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 13 | 120 | 0.5G/13H/120T |

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3.5 | 13 | 120 | 3.5G/13H/120T |

| 9 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 2.0 | 9 | 30 | 2.0G/9H/30T |

| 10 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 2.0 | 17 | 30 | 2.0G/17H/30T |

| 11 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 2.0 | 9 | 120 | 2.0G/9H/120T |

| 12 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2.0 | 17 | 120 | 2.0G/17H/120T |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.0 | 13 | 75 | 2.0G/13H/75T |

| Uncoded Parameters | Thermal Properties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | H | T | Tg (°C) | Tonset (°C) | Tmax (°C) | ΔHres (J.s−1) |

| 0.5 | 9 | 75 | 83.3 | 350.2 | 385.1 | 0.4 |

| 3.5 | 9 | 75 | 80.4 | 350.1 | 380.7 | 0.9 |

| 0.5 | 17 | 75 | 93.7 | 344.2 | 370.4 | 2.4 |

| 3.5 | 17 | 75 | 89.4 | 342.2 | 373.3 | 1.7 |

| 0.5 | 13 | 30 | 54.9 | 343.4 | 369.3 | 6.5 |

| 3.5 | 13 | 30 | 54.8 | 342.2 | 371.1 | 9.2 |

| 0.5 | 13 | 120 | 114.5 | 345.2 | 382.0 | - |

| 3.5 | 13 | 120 | 106.3 | 352.4 | 374.4 | - |

| 2.0 | 9 | 30 | 49.4 | 342.2 | 372.7 | 5.1 |

| 2.0 | 17 | 30 | 54.0 | 344.6 | 370.8 | 8.9 |

| 2.0 | 9 | 120 | 118.0 | 347.4 | 375.3 | - |

| 2.0 | 17 | 120 | 109.7 | 343.0 | 371.8 | - |

| 2.0 | 13 | 75 | 87.9 | 346.0 | 376.6 | 0.9 |

| Uncoded Parameters | Mechanical Properties | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | H | T | MOR (MPa) | MOE (GPa) | εf (%) |

| 0.5 | 9 | 75 | 205.2 ± 8.5 | 10.1 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.1 |

| 3.5 | 9 | 75 | 284.8 ± 6.4 | 12.1 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.1 |

| 0.5 | 17 | 75 | 285.0 ± 10.6 | 9.2 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.2 |

| 3.5 | 17 | 75 | 229.4 ± 19.7 | 8.7 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

| 0.5 | 13 | 30 | 216.3 ± 5.8 | 11.8 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.1 |

| 3.5 | 13 | 30 | 213.0 ± 9.2 | 11.8 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| 0.5 | 13 | 120 | 259.2 ± 9.6 | 8.6 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.2 |

| 3.5 | 13 | 120 | 245.8 ± 18.9 | 9.1 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.3 |

| 2.0 | 9 | 30 | 240.9 ± 32.8 | 12.6 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 0.2 |

| 2.0 | 17 | 30 | 180.7 ± 6.7 | 10.8 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.1 |

| 2.0 | 9 | 120 | 322.0 ± 12.8 | 9.7 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.2 |

| 2.0 | 17 | 120 | 245.8 ± 5.9 | 8.3 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.1 |

| 2.0 | 13 | 75 | 253.6 ± 35.7 | 10.6 ± 0.7 | 2.8 ± 0.3 |

| System | Filler Content | MOR (MPa) | MOE (GPa) | ΔMOR (%) | ΔMOE (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neat epoxy (DGEBA/TETA) | 0 wt.% | 70–110 | 2.2–3.0 | +258 | +273 | [36,37,38] |

| Epoxy + palm fibers | 50 vol.% | 32.64 | 3.28 | +887 | +196 | [36] |

| Epoxy + jute fibers | 50 wt.% | 208–248 | 2.0–2.5 | +41 | +331 | [39] |

| Epoxy + bamboo fibers + GO | 40–50 vol.% | 259.9–334.6 | 16.7–23.8 | +8 | −52 | [40] |

| Epoxy + GO | 0.5–1.0 wt.% | 98.5 | 3.65 | +227 | +166 | [38] |

| Epoxy + rGO | 0.5–1.0 wt.% | 92.7 | 3.28 | +247 | +196 | [38] |

| Epoxy + graphite | 1.0–1.2 wt.% | 80–90 | 3.0–3.2 | +279 | +213 | [41] |

| Pristine graphene/epoxy | 0.5–1.0 wt.% | 118.9 | 3.41 | +171 | +185 | [42] |

| GO/aramid fiber/epoxy | 0.1–0.7 wt.% | 130.5 | 2.94 | +147 | +230 | [43] |

| Epoxy + gNP | 0.5–1.5 wt.% | 80–110 | 2.8–3.2 | +239 | +223 | [44,45] |

| Epoxy+ NH2-GNs | 0.6 wt.% | 152.3 | 5.4 | +111 | +96 | [46] |

| Epoxy + pDop-rGO | 0.1 wt.% | 141 | 5.3 | +128 | +83 | [47] |

| Epoxy + gNP (optimized) | 2.0 wt.% GNP (2.0G/9H/120T) | 322.0 | 9.7 | — | — | PW |

| Uncoded Parameters | Viscoelastic Properties | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | H | T | Tg (°C) | E′ (30 °C) (MPa) | E′ (Tg + 30 °C) (MPa) | ΔlogE′ | tanδmax | (×10−3 mol.m−3) |

| 0.5 | 9 | 75 | 94.1 | 3141.2 | 31.4 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 3.2 |

| 3.5 | 9 | 75 | 104.7 | 4046.3 | 47.2 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 4.6 |

| 0.5 | 17 | 75 | 116.4 | 2616.7 | 59.6 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 5.7 |

| 3.5 | 17 | 75 | 115.3 | 2835.4 | 60.0 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 5.7 |

| 0.5 | 13 | 30 | 82.2 | 2473.6 | 65.9 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 6.9 |

| 3.5 | 13 | 30 | 81.8 | 3659.7 | 136.8 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 14.2 |

| 0.5 | 13 | 120 | 138.2 | 2140.5 | 38.8 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 3.5 |

| 3.5 | 13 | 120 | 139.5 | 2521.5 | 53.7 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 4.9 |

| 2.0 | 9 | 30 | 72.9 | 3144.3 | 9.4 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| 2.0 | 17 | 30 | 132.0 | 2770.1 | 49.1 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 4.5 |

| 2.0 | 9 | 120 | 133.0 | 2904.0 | 46.0 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 4.2 |

| Vibration | Wavenumber (cm−1) |

|---|---|

| -OH stretching | 3411 |

| C-H stretching | 2800–3000 |

| Asymmetrical stretching -CH and -CH2 group | 2937 |

| Symmetrical stretching -CH and -CH3 group | 2871 |

| C=C stretching bands of aromatic rings | 1505–1605 |

| Epoxy ring mode | 1295, 917 |

| Asymmetric axial deformation of the ether group | 1233 |

| C-O stretching of the aromatic ring | 1180 |

| Symmetrical aromatic C-O stretching | 1030 |

| Aromatic ring bent out of plane | 825 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mendes, J.; Magalhães, C.P.; Vitorazi, L.; Huaman, N.R.C.; Monteiro, S.N.; Gómez-del Río, T.; Costa, U.O. Statistical Optimization of Graphene Nanoplatelet-Reinforced Epoxy Nanocomposites via Box–Behnken Design for Superior Flexural and Dynamic Mechanical Performance. Polymers 2025, 17, 3218. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233218

Mendes J, Magalhães CP, Vitorazi L, Huaman NRC, Monteiro SN, Gómez-del Río T, Costa UO. Statistical Optimization of Graphene Nanoplatelet-Reinforced Epoxy Nanocomposites via Box–Behnken Design for Superior Flexural and Dynamic Mechanical Performance. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3218. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233218

Chicago/Turabian StyleMendes, Júlia, Camila Prudente Magalhães, Letícia Vitorazi, Noemi Raquel Checca Huaman, Sergio Neves Monteiro, Teresa Gómez-del Río, and Ulisses Oliveira Costa. 2025. "Statistical Optimization of Graphene Nanoplatelet-Reinforced Epoxy Nanocomposites via Box–Behnken Design for Superior Flexural and Dynamic Mechanical Performance" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3218. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233218

APA StyleMendes, J., Magalhães, C. P., Vitorazi, L., Huaman, N. R. C., Monteiro, S. N., Gómez-del Río, T., & Costa, U. O. (2025). Statistical Optimization of Graphene Nanoplatelet-Reinforced Epoxy Nanocomposites via Box–Behnken Design for Superior Flexural and Dynamic Mechanical Performance. Polymers, 17(23), 3218. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233218