Immobilization of Trypsin and Lysozyme in Halloysite Nanotubes for Producing Chitosan Coatings with Antibacterial Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Halloysite Modification

2.3. Preparation of Nanocomposites Based on Halloysite Nanotubes and the Trypsin and Lysozyme Enzymes

2.4. Determining the Nanotube Modification with CMC and Enzymes

2.5. Hyperspectral and Dark-Field Microscopy of Halloysite Nanocomposites

2.6. Atomic Force Microscopy

2.7. Antibacterial Activity of Halloysite Nanocomposites

2.8. Preparation of Coatings Based on Halloysite Nanocomposites and Chitosan

2.9. Determination of the Antibacterial Activity of the Coatings

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Composite Structure Investigation

3.1.1. Hydrodynamic Diameter and Zeta Potential of Nanocomposites

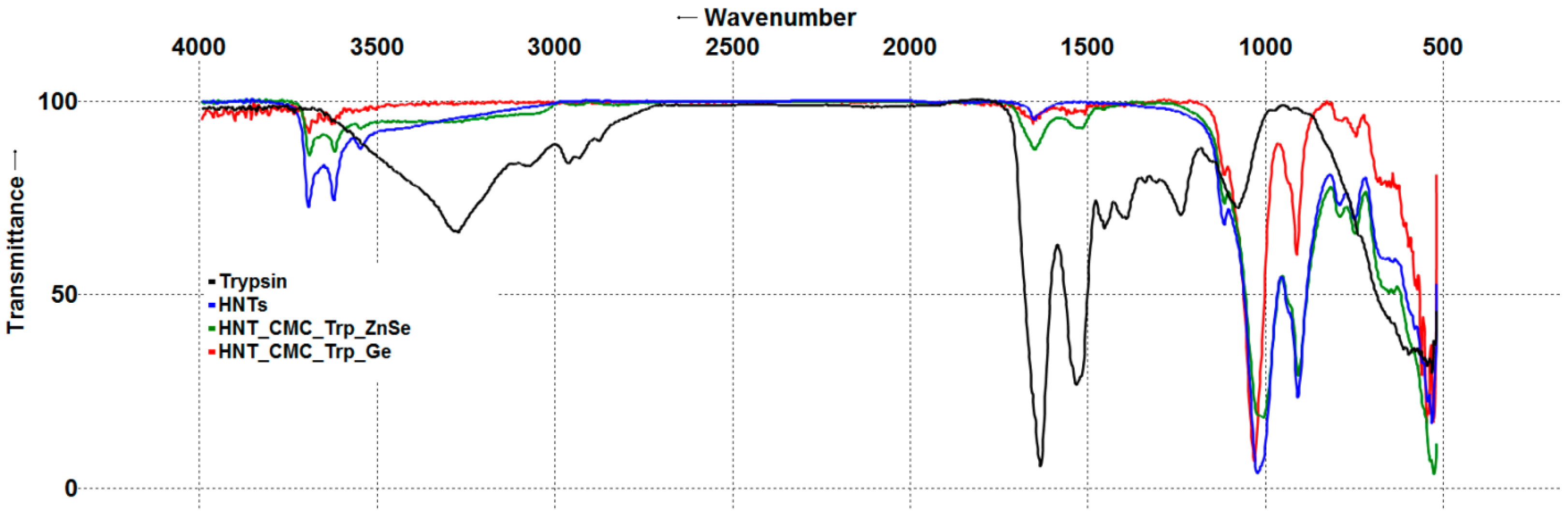

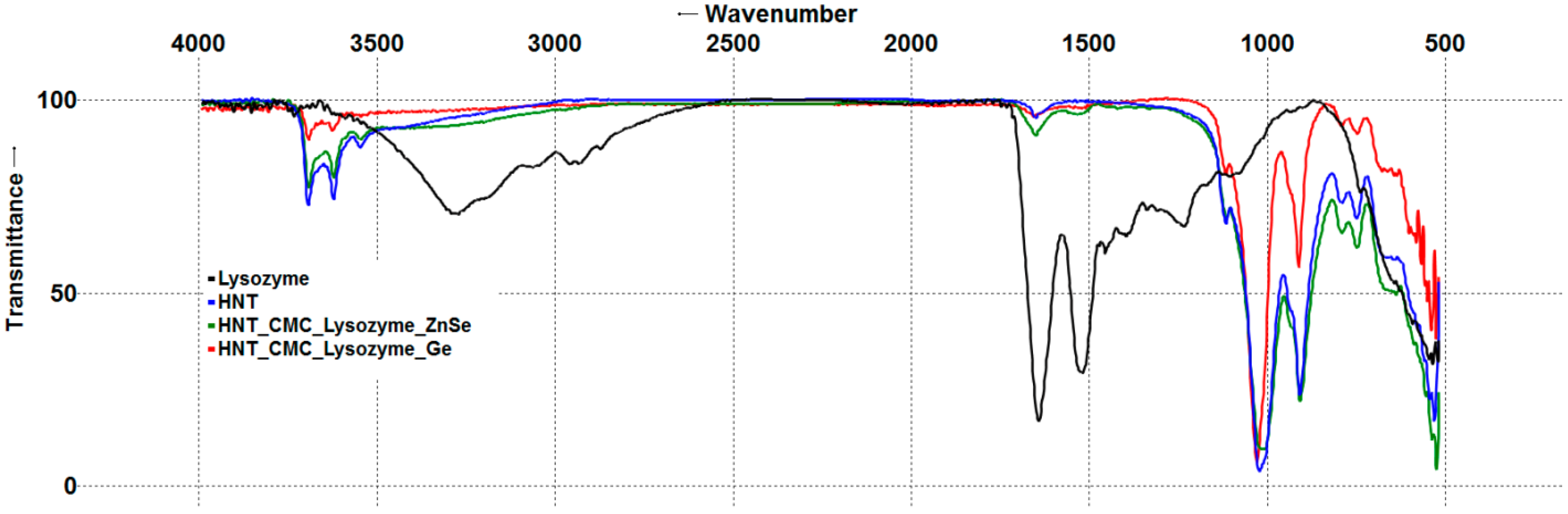

3.1.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy of Nanocomposites

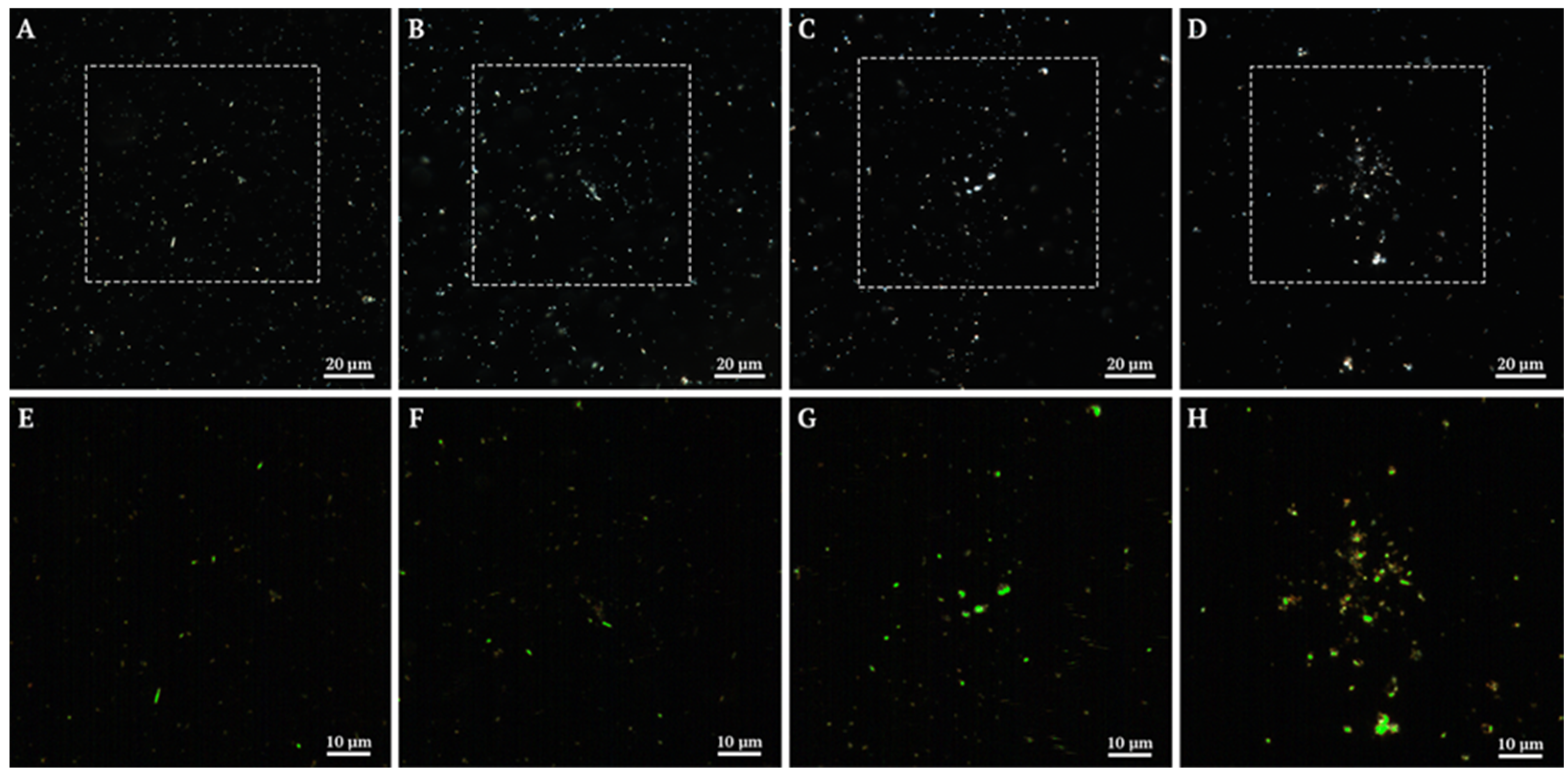

3.1.3. Composite Hyperspectral Analysis and Dark-Field Microscopy

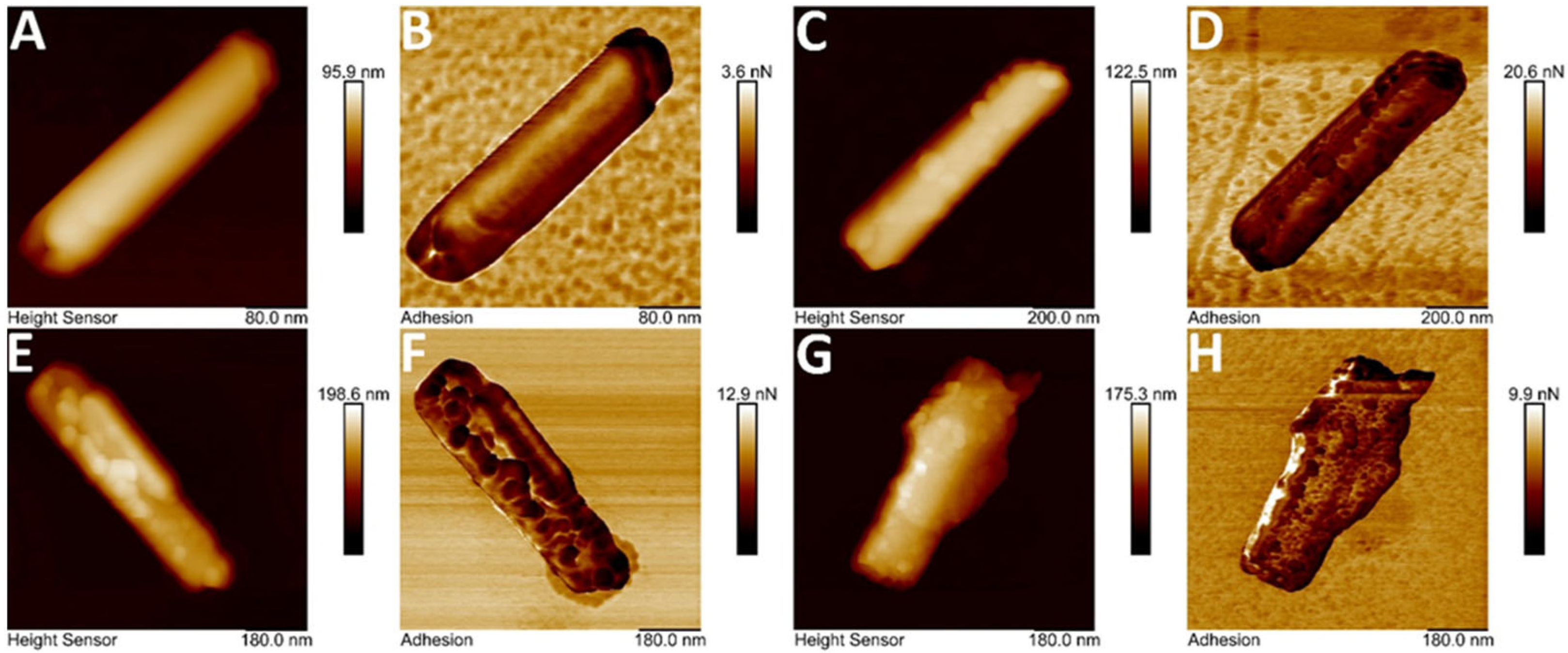

3.1.4. Atomic Force Microscopy of Halloysite-Based Composites

3.2. Antibacterial Activity of Nanocomposites

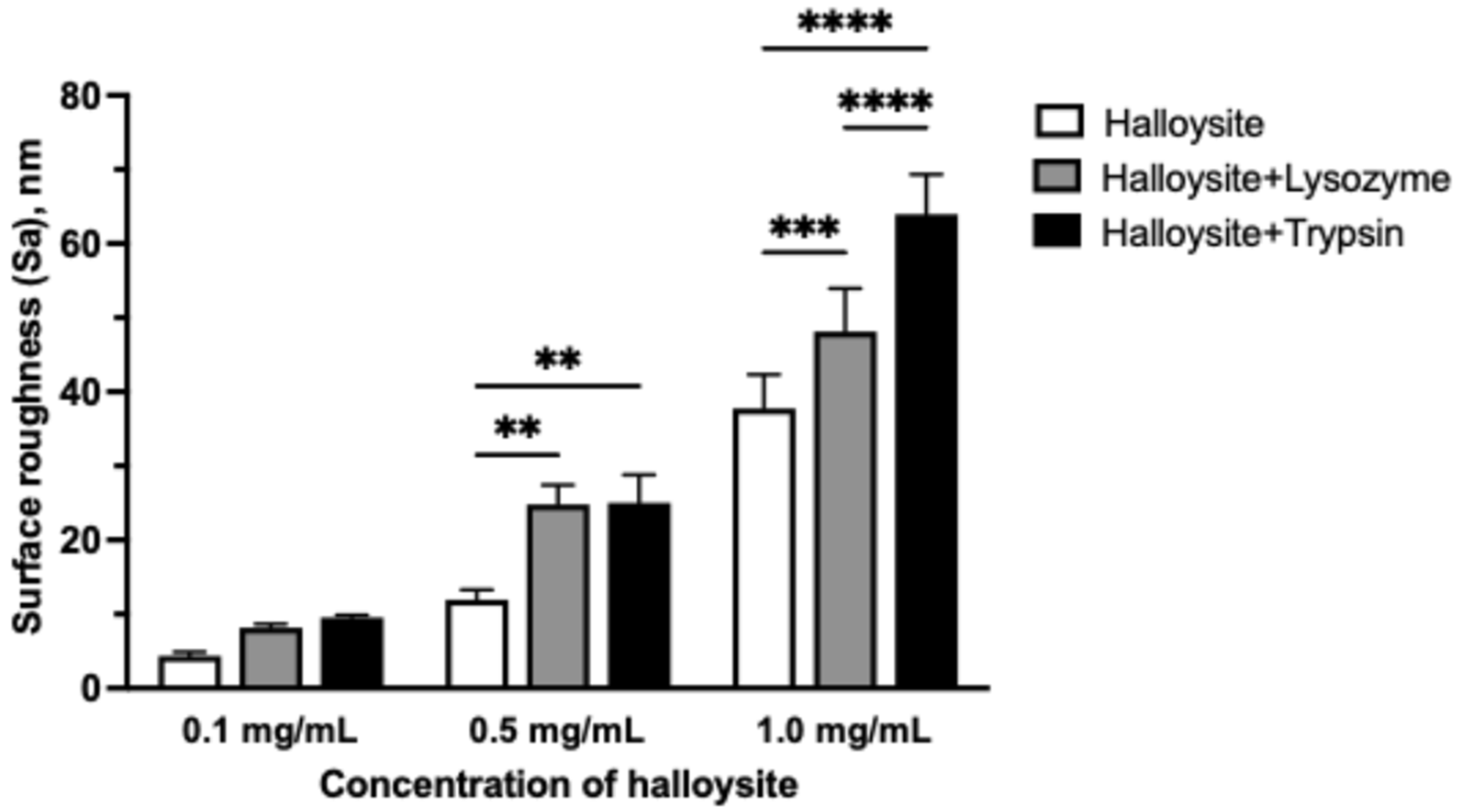

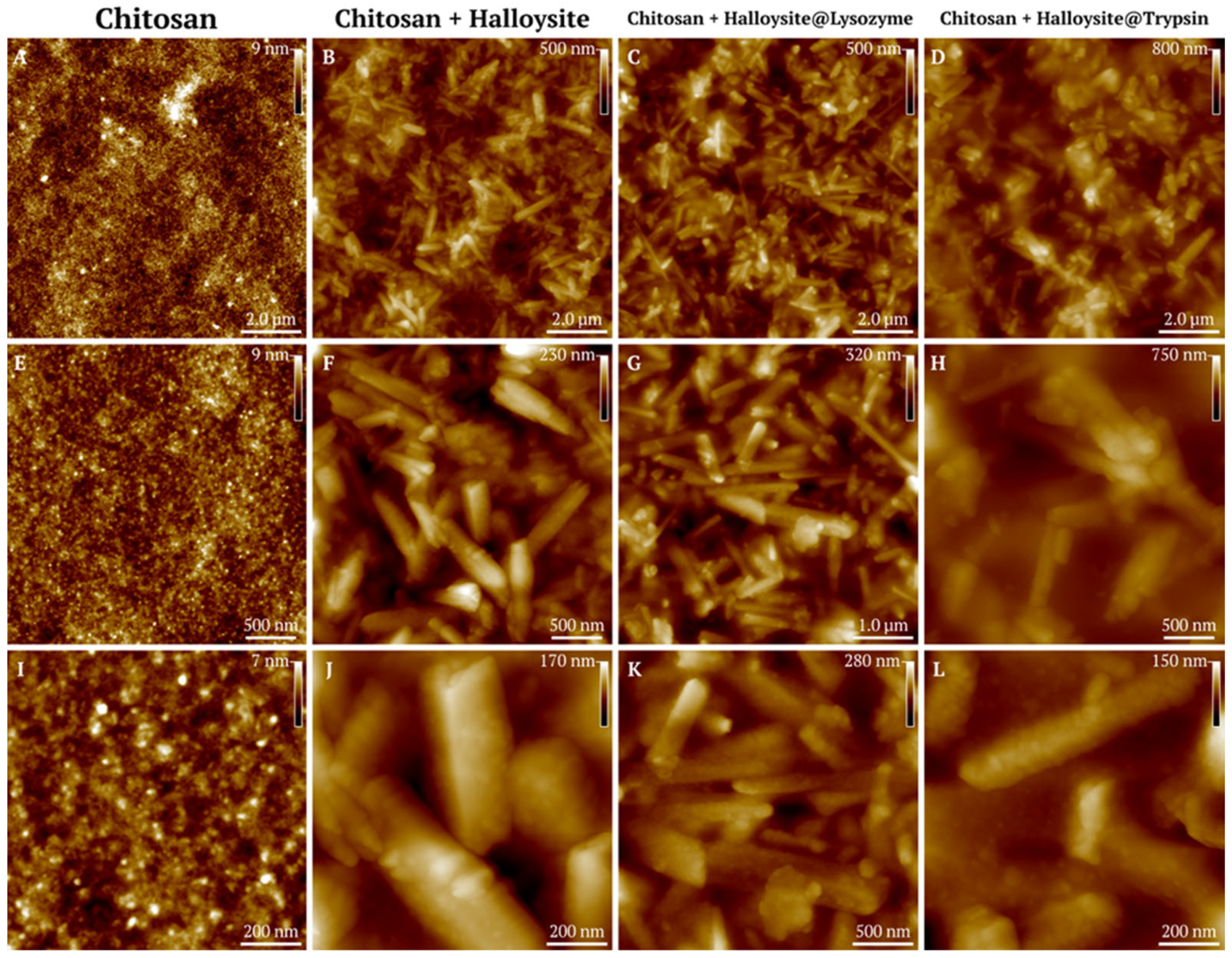

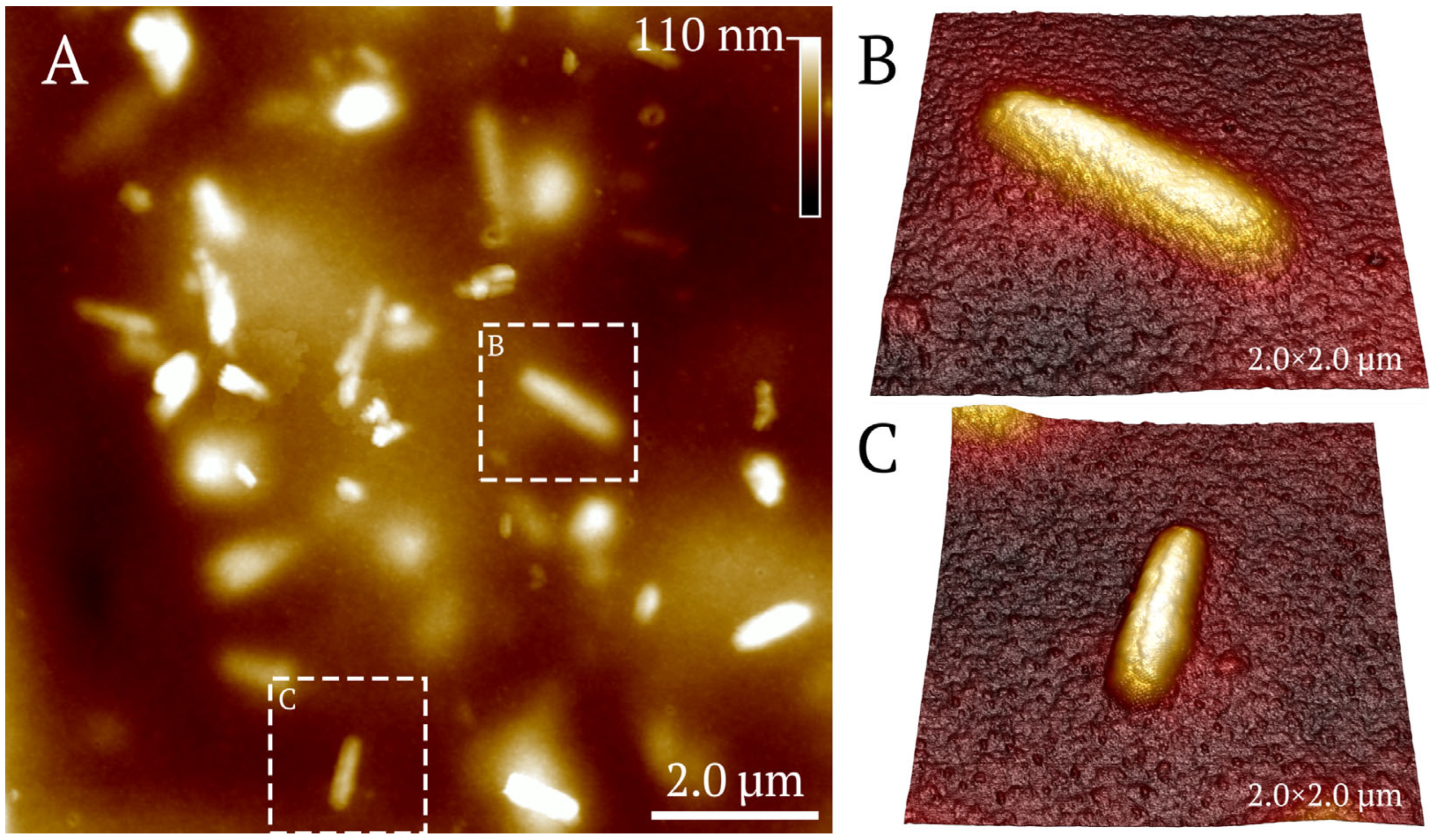

3.3. Atomic Force Microscopy of the Coatings

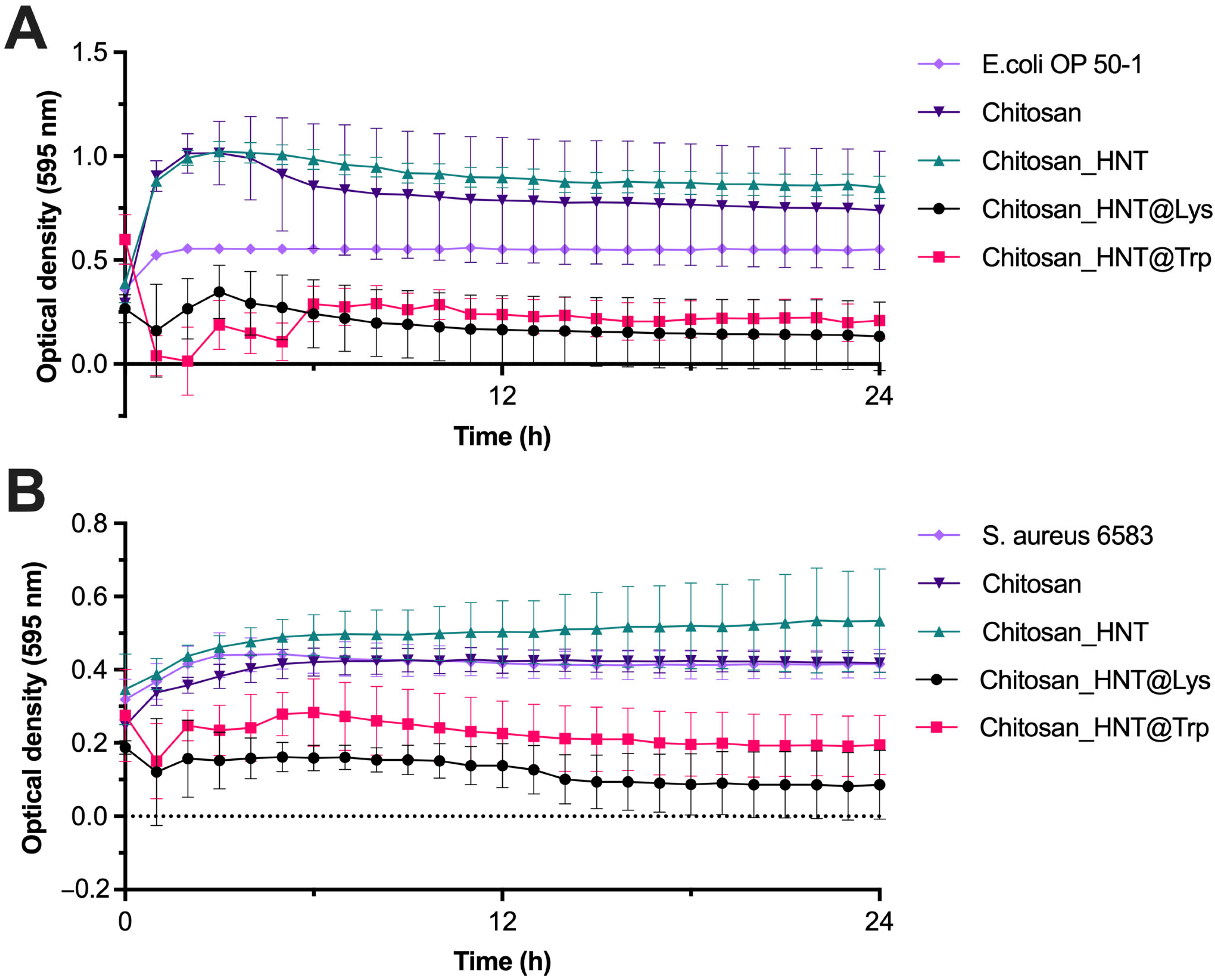

3.4. Antibacterial Activity of the Coatings

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| E. coli OP 50-1. | Escherichia coli strain OP 50-1 |

| S. aureus 6583 | Staphylococcus aureus 6583 |

| CMC | carboxymethylcellulose |

| FTIR-ATR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy Attenuated total reflection |

| HNT | halloysite nanotubes |

| Lys | lysozyme |

| Trp | trypsin |

References

- Song, J.W.; Kawakami, K.; Ariga, K. Nanoarchitectonics in Combat Against Bacterial Infection using Molecular, Interfacial, and Material Tools. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 65, 101702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellard, M. The Enzyme as Drug: Application of Enzymes as Pharmaceuticals. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2003, 14, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, S.; Sharma, A.; Singh, S.; Sharma, S.; Sarma, S.J. Therapeutic Enzymes: Discoveries, Production and Applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 63, 102455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J.; Ismail, A.E.; Dinu, C.Z. Industrial Applications of Enzymes: Recent Advances, Techniques, and Outlooks. Catalysts 2018, 8, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.H.; Wang, Z.; Yin, B.; Wu, H.; Tang, S.; Wu, L.; Su, Y.N.; Lin, Y.; Liu, X.Q.; Pang, B.; et al. A Complex of Trypsin and Chymotrypsin Effectively Inhibited Growth of Pathogenic Bacteria Inducing Cow Mastitis and Showed Synergistic Antibacterial Activity with Antibiotics. Livest. Sci. 2016, 188, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuceer, M.; Caner, C. Antimicrobial Lysozyme–Chitosan Coatings Affect Functional Properties and Shelf Life of Chicken Eggs during Storage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Qin, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, M.; Xiong, L.; Sun, Q. Enhanced Antibacterial Activity of Lysozyme Immobilized on Chitin Nanowhiskers. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1507–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommarius, A.S.; Paye, M.F. Stabilizing Biocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, R.C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Carballares, D.; Morellon-Sterling, R.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Stabilization of Enzymes via Immobilization: Multipoint Covalent Attachment and Other Stabilization Strategies. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 52, 107821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavolaro, A.; Tavolaro, P.; Drioli, E. Zeolite Inorganic Supports for BSA Immobilization: Comparative Study of Several Zeolite Crystals and Composite Membranes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2007, 55, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirahama, H.; Lyklema, J.; Norde, W. Comparative Protein Adsorption in Model Systems. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1990, 139, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostuni, E.; Grzybowski, B.A.; Mrksich, M.; Roberts, C.S.; Whitesides, G.M. Adsorption of Proteins to Hydrophobic Sites on Mixed Self-Assembled Monolayers. Langmuir 2003, 19, 1861–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K.D.; Misra, R.; Williams, L.B. Unearthing the Antibacterial Mechanism of Medicinal Clay: A Geochemical Approach to Combating Antibiotic Resistance. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lvov, Y.; Abdullayev, E. Functional Polymer–Clay Nanotube Composites with Sustained Release of Chemical Agents. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013, 38, 1690–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, G.; Milioto, S.; Lazzara, G. Halloysite Nanotubes: Interfacial Properties and Applications in Cultural Heritage. Langmuir 2020, 36, 3677–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouster, P.; Dondelinger, M.; Galleni, M.; Nysten, B.; Jonas, A.M.; Glinel, K. Layer-by-Layer Assembly of Enzyme-Loaded Halloysite Nanotubes for the Fabrication of Highly Active Coatings. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 178, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Tan, D.; Annabi-Bergaya, F. Properties and Applications of Halloysite Nanotubes: Recent Research Advances and Future Prospects. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 112–113, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yendluri, R.; Liu, K.; Guo, Y.; Lvov, Y.; Yan, X. Enzyme-Immobilized Clay Nanotube–Chitosan Membranes with Sustainable Biocatalytic Activities. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, J.; Yendluri, R.; Lvov, Y. Halloysite Clay Nanotubes for Enzyme Immobilization. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzara, G.; Bruno, F.; Brancato, D.; Sturiale, V.; D’Amico, A.G.; Miloto, S.; Pasbakhsh, P.; D’Agata, V.; Saccone, S.; Federico, C. Biocompatibility Analysis of Halloysite Clay Nanotubes. Mater. Lett. 2023, 336, 133852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavitskaya, A.; Batasheva, S.; Vinokurov, V.; Fakhrullina, G.; Sangarov, V.; Lvov, Y.; Fakhrullin, R. Antimicrobial Applications of Clay Nanotube-Based Composites. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergaro, V.; Abdullayev, E.; Lvov, Y.M.; Zeitoun, A.; Cingolani, R.; Rinaldi, R.; Leporatti, S. Cytocompatibility and Uptake of Halloysite Clay Nanotubes. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Luan, M.; Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Koosha, M.; Zhai, Y.; Fakhrullin, R.F. Hydrophilic Chitosan: Modification Pathways and Biomedical Applications. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2024, 93, RCR5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tu, H.; Huang, M.; Chen, J.; Shi, X.; Deng, H.; Wang, S.; Du, Y. Incorporation of Lysozyme-Rectorite Composites into Chitosan Films for Antibacterial Properties Enhancement. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 102, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aider, M. Chitosan Application for Active Bio-Based Films Production and Potential in the Food Industry: Review. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 43, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherednichenko, Y.V.; Ishmukhametov, I.R.; Fakhrullina, G.I. Surface modifiers for reducing bacterial contamination in medicine and food industry. Colloid J. 2025, 87, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, H.; Jia, N. Direct Electrochemistry and Electrocatalysis of Horseradish Peroxidase Based on Halloysite Nanotubes/Chitosan Nanocomposite Film. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 56, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P.T.; Rodriguez, A.; de Winter, T.M.; Coish, P.; Zimmerman, J.B. A Review of Immobilization Techniques to Improve the Stability and Bioactivity of Lysozyme. Green. Chem. Lett. Rev. 2021, 14, 302–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, M.; Morsi, R.E.; Kerch, G.; Elsabee, M.Z.; Kaya, M.; Labidi, J.; Khawar, K.M. Current Advancements in Chitosan-Based Film Production for Food Technology; A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 121, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, K.; Sionkowska, A.; Kaczmarek, B.; Furtos, G. Characterization of Chitosan Composites with Various Clays. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 65, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Assimi, T.; Lakbita, O.; El Meziane, A.; Khouloud, M.; Dahchour, A.; Beniazza, R.; Boulif, R.; Raihane, M.; Lahcini, M. Sustainable Coating Material Based on Chitosan-Clay Composite and Paraffin Wax for Slow-Release DAP Fertilizer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabiri, K.; Mirzadeh, H.; Zohuriaan-Mehr, M.J.; Daliri, M. Chitosan-modified Nanoclay–Poly(AMPS) Nanocomposite Hydrogels with Improved Gel Strength. Polym. Int. 2009, 58, 1252–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ren, X.; Hanna, M.A. Chitosan/Clay Nanocomposite Film Preparation and Characterization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 99, 1684–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, J.M.; Kryuchkova, M.; Fakhrullin, R.; Mazurova, K.; Stavitskaya, A.; Cheatham, B.J.; Fakhrullin, R. Size-Dependent Oscillation in Optical Spectra from Fly Ash Cenospheres: Particle Sizing Using Darkfield Hyperspectral Interferometry. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2023, 96, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.V.; Prevost, N.T.; Condon, B.; French, A.; Wu, Q. Immobilization of Lysozyme-Cellulose Amide-Linked Conjugates on Cellulose I and II Cotton Nanocrystalline Preparations. Cellulose 2012, 19, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, K.M.A.; Orelma, H.; Mohammadi, P.; Borghei, M.; Laine, J.; Linder, M.; Rojas, O.J. Retention of Lysozyme Activity by Physical Immobilization in Nanocellulose Aerogels and Antibacterial Effects. Cellulose 2017, 24, 2837–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Pei, Y.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, C.; Xu, W.; Liu, S.; Li, B. Curcumin Encapsulated in the Complex of Lysozyme/Carboxymethylcellulose and Implications for the Antioxidant Activity of Curcumin. Food Res. Int. 2015, 75, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.V.; Prevost, N.T.; Condon, B.; French, A. Covalent Attachment of Lysozyme to Cotton/Cellulose Materials: Protein Verses Solid Support Activation. Cellulose 2011, 18, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishmukhametov, I.; Batasheva, S.; Konnova, S.; Lvov, Y.; Fakhrullin, R. Self-assembly of halloysite nanotubes in water modulated via heterogeneous surface charge and transparent exopolymer particles. Appl. Clay Sci. 2025, 270, 107775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolino, V.; Cavallaro, G.; Lazzara, G.; Milioto, S.; Parisi, F. Biopolymer-Targeted Adsorption onto Halloysite Nanotubes in Aqueous Media. Langmuir 2017, 33, 3317–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhu, X.; Xu, J.; Peng, W.; Zhong, S.; Wang, Y. The Combination of Adsorption by Functionalized Halloysite Nanotubes and Encapsulation by Polyelectrolyte Coatings for Sustained Drug Delivery. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 54463–54470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, X.; Chen, R. Surface Modification of Halloysite Nanotubes with Dopamine for Enzyme Immobilization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 10559–10564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, A.A.; Jang, J.; Lee, D.S. Supermagnetically Tuned Halloysite Nanotubes Functionalized with Aminosilane for Covalent Laccase Immobilization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 15492–15501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, M.; Arbain, D.; Islam, A.K.M.S.; Rahman, M.; Ahmad, M.S.; Ahmad, M.N. Covalent Immobilization of α-Glucosidase Enzyme onto Amine Functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Curr. Nanosci. 2014, 10, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spragg, R. Contact and Orientation Effects in FT-IR ATR Spectra. Spectroscopy 2011, 26, 8. Available online: https://www.spectroscopyonline.com/view/contact-and-orientation-effects-ft-ir-atr-spectra (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Chittur, K.K. FTIR/ATR for Protein Adsorption to Biomaterial Surfaces. Biomaterials 1998, 19, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helal, R.; Melzig, M.F. Determination of Lysozyme Activity by a Fluorescence Technique in Comparison with the Classical Turbidity Assay. Pharmazie 2008, 63, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawson, R.; Gamage, M.; Terefe, N.S.; Knoerzer, K. Ultrasound in Enzyme Activation and Inactivation. In Ultrasound Technologies for Food and Bioprocessing; Feng, H., Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V., Weiss, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 369–404. ISBN 978-1-4419-7471-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J. Facile Fabrication of Flowerlike Natural Nanotube/Layered Double Hydroxide Composites as Effective Carrier for Lysozyme Immobilization. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.-Z.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Zhao, H.-Z. Preparation and Antibacterial Activity of Lysozyme and Layered Double Hydroxide Nanocomposites. Water Res. 2013, 47, 6712–6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Bawazir, M.; Dhall, A.; Kim, H.-E.; He, L.; Heo, J.; Hwang, G. Implication of Surface Properties, Bacterial Motility, and Hydrodynamic Conditions on Bacterial Surface Sensing and Their Initial Adhesion. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 643722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, M.; Liu, S.; DeFlorio, W.; Hao, L.; Wang, X.; Salazar, K.S.; Taylor, M.; Castillo, A.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Oh, J.K.; et al. Influence of Surface Roughness, Nanostructure, and Wetting on Bacterial Adhesion. Langmuir 2023, 39, 5426–5439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morais, L.C.; Bernardes-Filho, R.; Assis, O.B.G. Wettability and Bacteria Attachment Evaluation of Multilayer Proteases Films for Biosensor Application. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 25, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Chen, X.-G.; Park, H.-J.; Liu, C.-G.; Liu, C.-S.; Meng, X.-H.; Yu, L.-J. Effect of MW and Concentration of Chitosan on Antibacterial Activity of Escherichia Coli. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 64, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y. Antimicrobial Effect of Chitooligosaccharides Produced by Bioreactor. Carbohydr. Polym. 2001, 44, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-B.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, H.-H. Low Molecular Weight Chitosan Prepared with the Aid of Cellulase, Lysozyme and Chitinase: Characterisation and Antibacterial Activity. Food Chem. 2009, 116, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillu, D.; Agnihotri, S. Cellulase Immobilization onto Magnetic Halloysite Nanotubes: Enhanced Enzyme Activity and Stability with High Cellulose Saccharification. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 900–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajišnik, D.; Uskoković-Marković, S.; Daković, A. Chitosan–Clay Mineral Nanocomposites with Antibacterial Activity for Biomedical Application: Advantages and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Yuan, L.; Chen, H. Recyclable Antibacterial Material: Silicon Grafted with 3,6-O-Sulfated Chitosan and Specifically Bound by Lysozyme. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nanoparticle | Hydrodynamic Diameter, nm | Zeta Potential, mV |

|---|---|---|

| HNT | 284.5 ± 5.3 | −27.6 ± 0.3 |

| HNT + CMC | 369.7 ± 10.7 | −35.5 ± 0.1 |

| HNT + CMC + lysozyme | 460.7 ± 7.7 | −24.5 ± 0.8 |

| HNT + CMC + trypsin | 501.6 ± 22.4 | −18.8 ± 0.7 |

| Sample | Sa, nm | Sp, nm | Sq, nm | Sv, nm | Sz, nm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | 0.96 ± 0.09 | 15.76 ± 4.01 | 1.26 ± 0.12 | −4.85 ± 0.45 | 20.62 ± 3.95 | |

| Chitosan + Halloysite, mg/mL | 0.1 | 4.35 ± 0.54 | 94.35 ± 13.30 | 7.47 ± 1.13 | −15.88 ± 4.24 | 110.6 ± 14.50 |

| 0.5 | 11.96 ± 1.30 * | 123.7 ± 33.55 * | 17.30 ± 2.11 * | −59.04 ± 10.39 * | 182.6 ± 31.88 | |

| 1.0 | 37.75 ± 4.59 * | 169.3 ± 64.10 * | 47.57 ± 5.78 * | −149.3 ± 24.09 * | 352.2 ± 52.86 * | |

| Chitosan + Halloysite + Lysozyme, mg/mL | 0.1 | 8.16 ± 0.51 | 104.3 ± 42.71 | 11.87 ± 0.93 | −25.97 ± 4.50 | 130.4 ± 39.91 |

| 0.5 | 24.83 ± 2.60 * | 166.0 ± 22.61 * | 32.43 ± 3.21 * | −106.9 ± 18.48 * | 273.0 ± 13.11 * | |

| 1.0 | 48.16 ± 5.80 * | 293.0 ± 78.34 * | 61.03 ± 7.90 * | −200.3 ± 35.93 * | 493.4 ± 100.4 * | |

| Chitosan + Halloysite + Trypsin, mg/mL | 0.1 | 9.54 ± 0.30 | 105.9 ± 7.09 | 13.88 ± 0.43 * | −46.08 ± 14.10 | 151.8 ± 11.87 |

| 0.5 | 25.03 ± 3.78 * | 189.0 ± 48.51 * | 32.87 ± 4.79 * | −106.0 ± 24.05 * | 295.0 ± 63.69 * | |

| 1.0 | 64.03 ± 5.36 * | 349.4 ± 57.87 * | 80.99 ± 8.16 * | −249.8 ± 49.03 * | 589.0 ± 73.37 * | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cherednichenko, Y.; Ishmukhametov, I.; Batasheva, S.; Fakhrullina, G.; Fakhrullin, R. Immobilization of Trypsin and Lysozyme in Halloysite Nanotubes for Producing Chitosan Coatings with Antibacterial Properties. Polymers 2025, 17, 3212. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233212

Cherednichenko Y, Ishmukhametov I, Batasheva S, Fakhrullina G, Fakhrullin R. Immobilization of Trypsin and Lysozyme in Halloysite Nanotubes for Producing Chitosan Coatings with Antibacterial Properties. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3212. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233212

Chicago/Turabian StyleCherednichenko, Yuliya, Ilnur Ishmukhametov, Svetlana Batasheva, Gölnur Fakhrullina, and Rawil Fakhrullin. 2025. "Immobilization of Trypsin and Lysozyme in Halloysite Nanotubes for Producing Chitosan Coatings with Antibacterial Properties" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3212. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233212

APA StyleCherednichenko, Y., Ishmukhametov, I., Batasheva, S., Fakhrullina, G., & Fakhrullin, R. (2025). Immobilization of Trypsin and Lysozyme in Halloysite Nanotubes for Producing Chitosan Coatings with Antibacterial Properties. Polymers, 17(23), 3212. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233212