Novel Core–Shell Nanostructure of ε-Poly-L-lysine and Polyamide-6 Polymers for Reusable and Durable Antimicrobial Function

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Electrospinning Solution

2.3. Electrospinning

2.4. Thermal Bonding of Core–Shell Nanofibers

2.5. Morphological Analysis

2.6. Chemical Characterization

2.7. Thermal Analysis

2.8. Water Contact Angle

2.9. Antimicrobial Analysis

2.10. Antimicrobial Performance upon Long-Term Exposure to Bacteria

2.11. Reusability of Antimicrobial Function

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

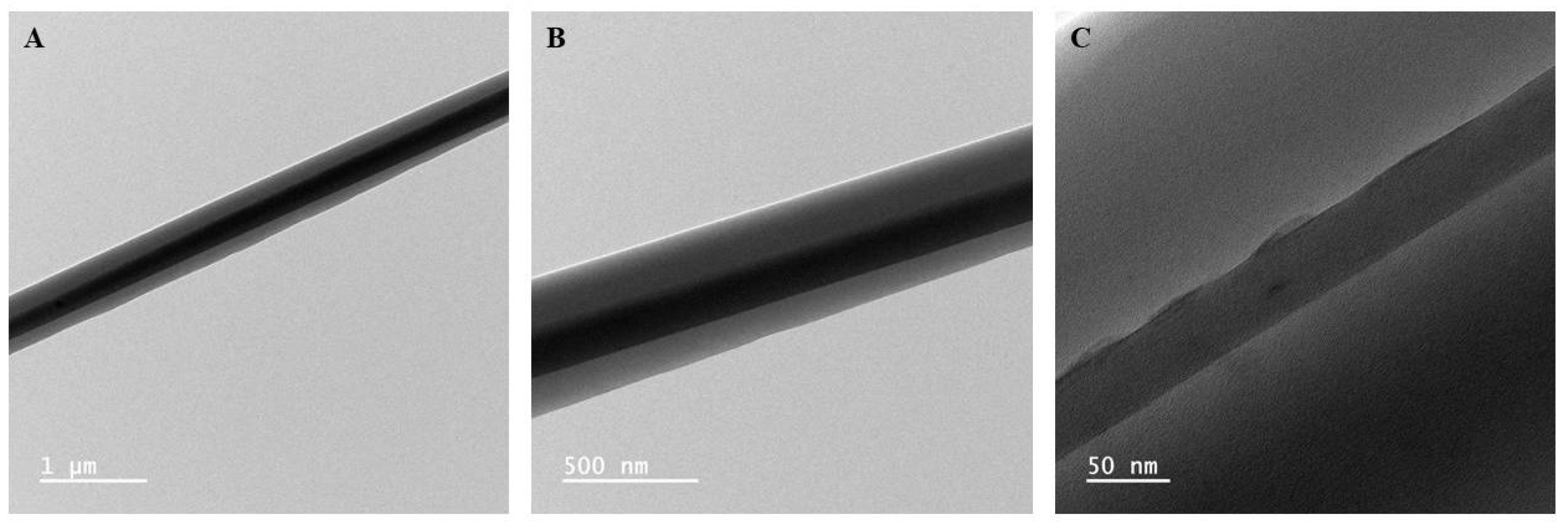

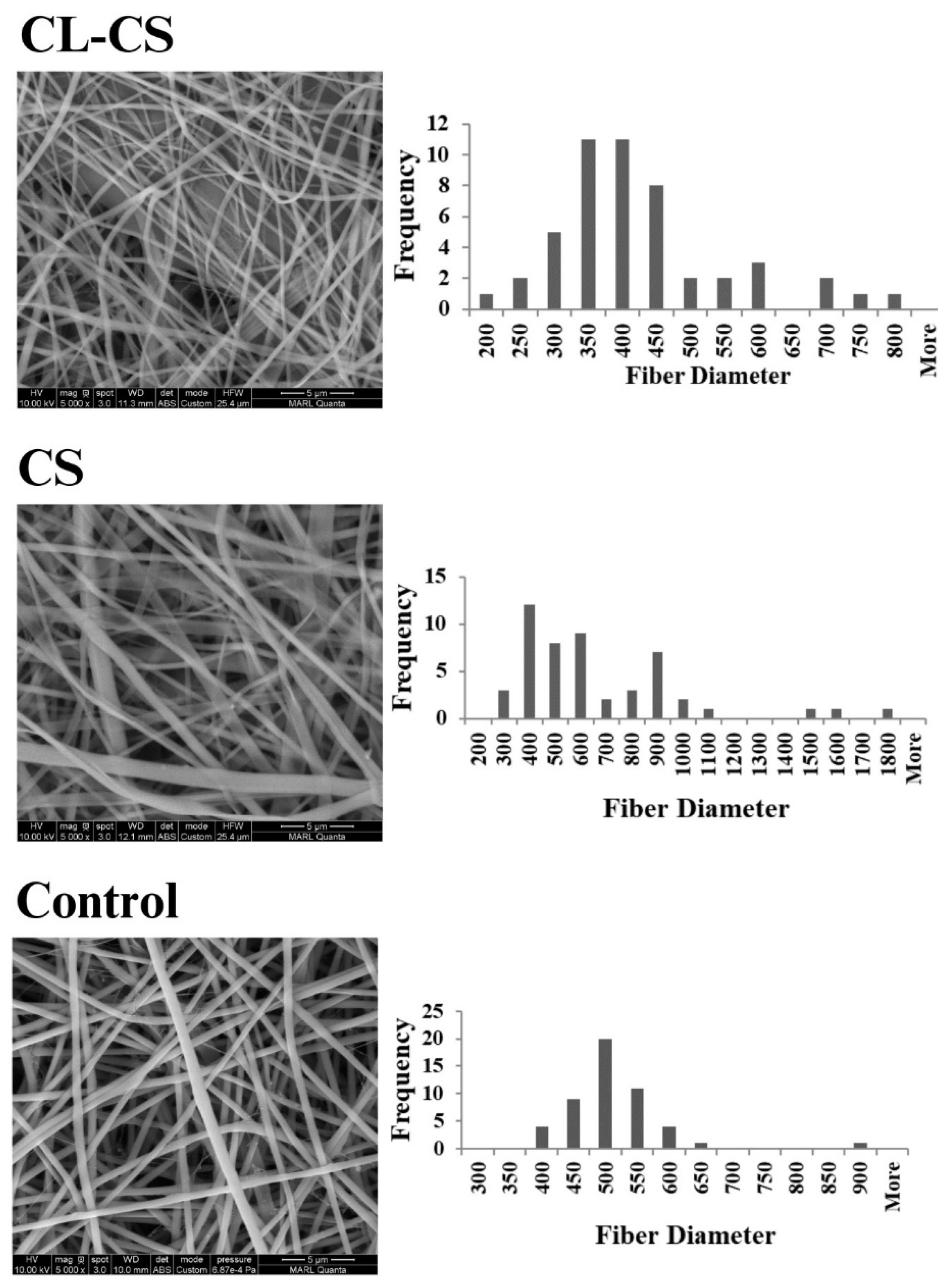

3.1. Morphological Analysis of Nanofibers

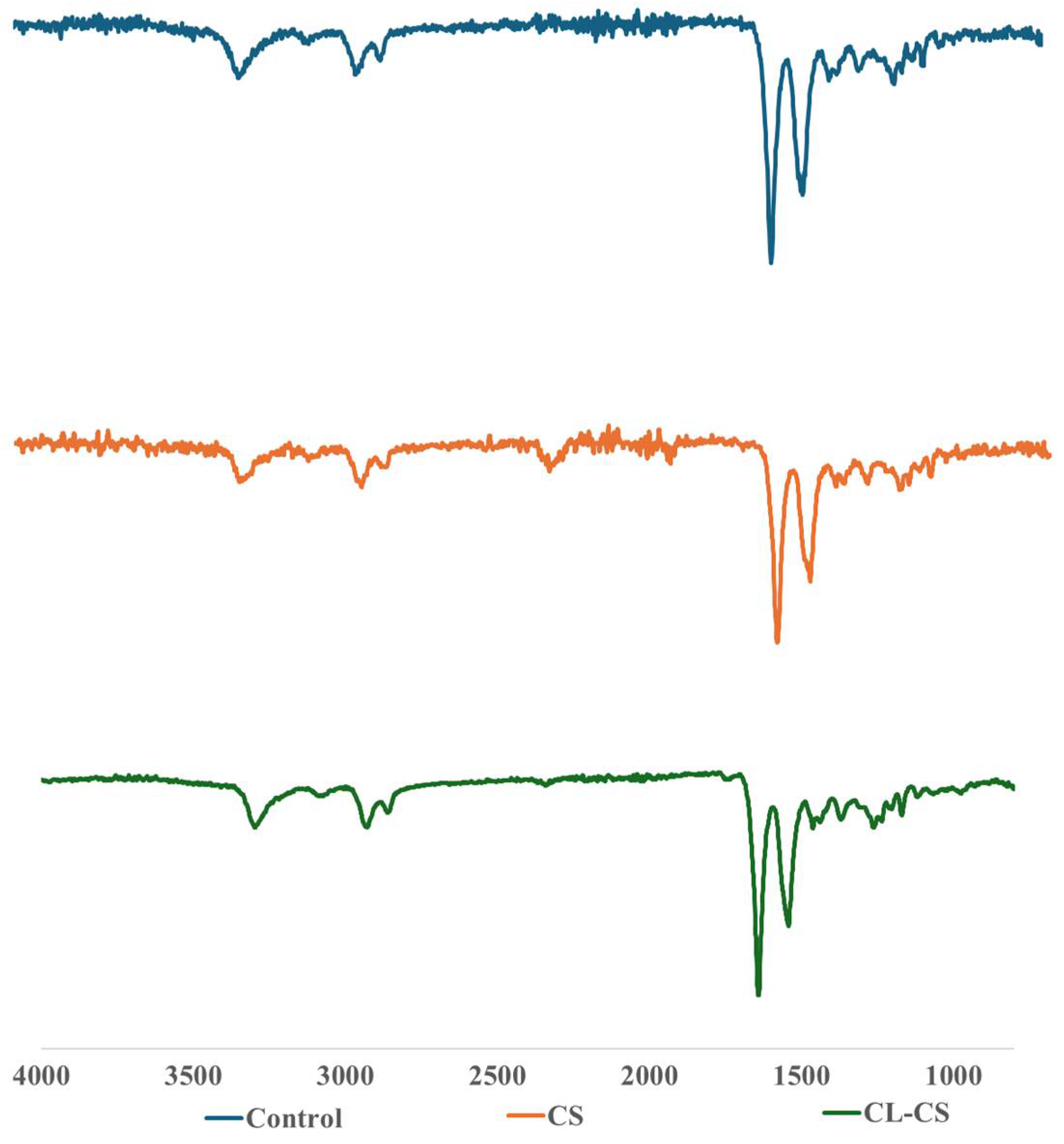

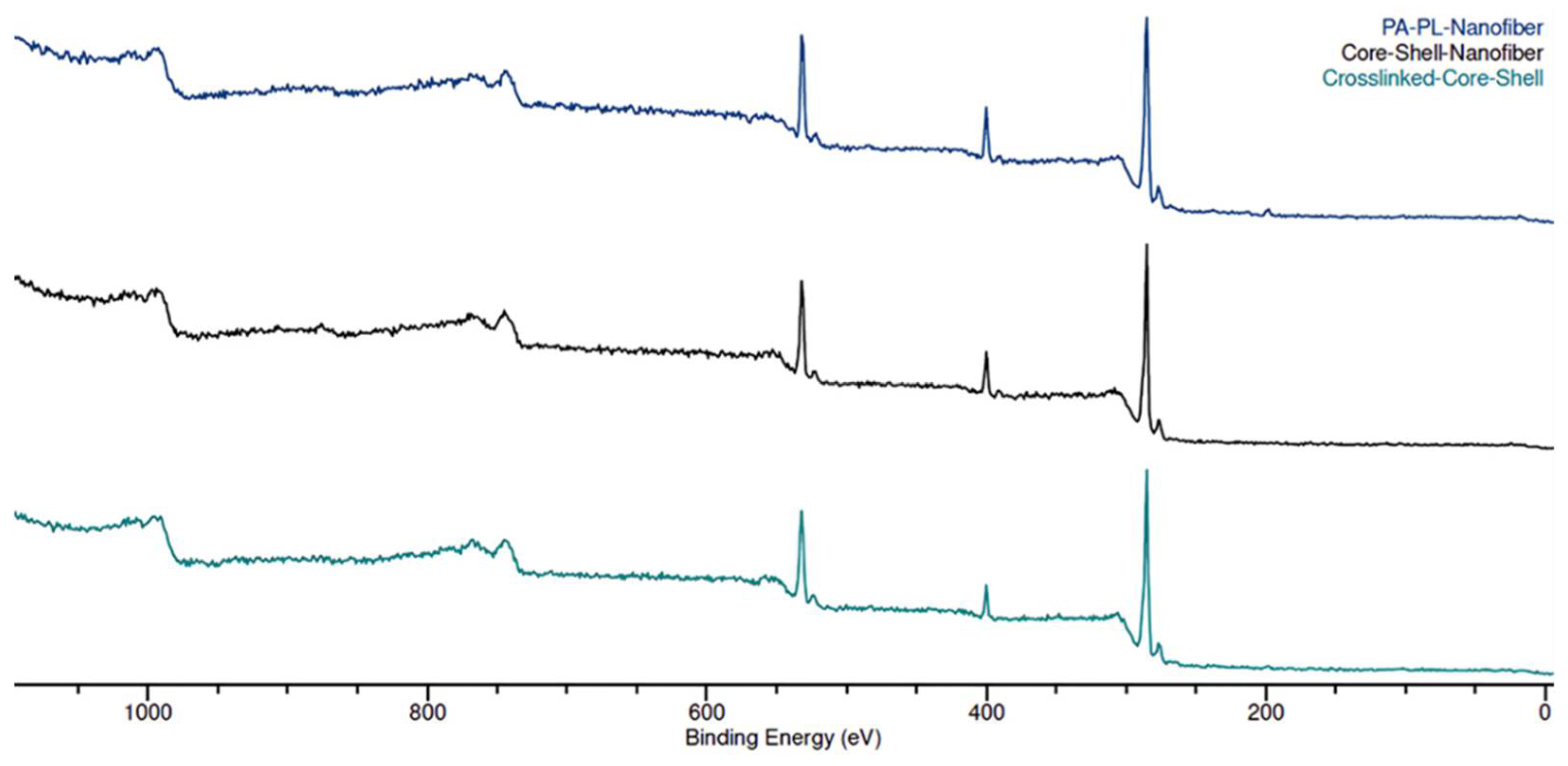

3.2. Chemical Characterization of Nanomembranes

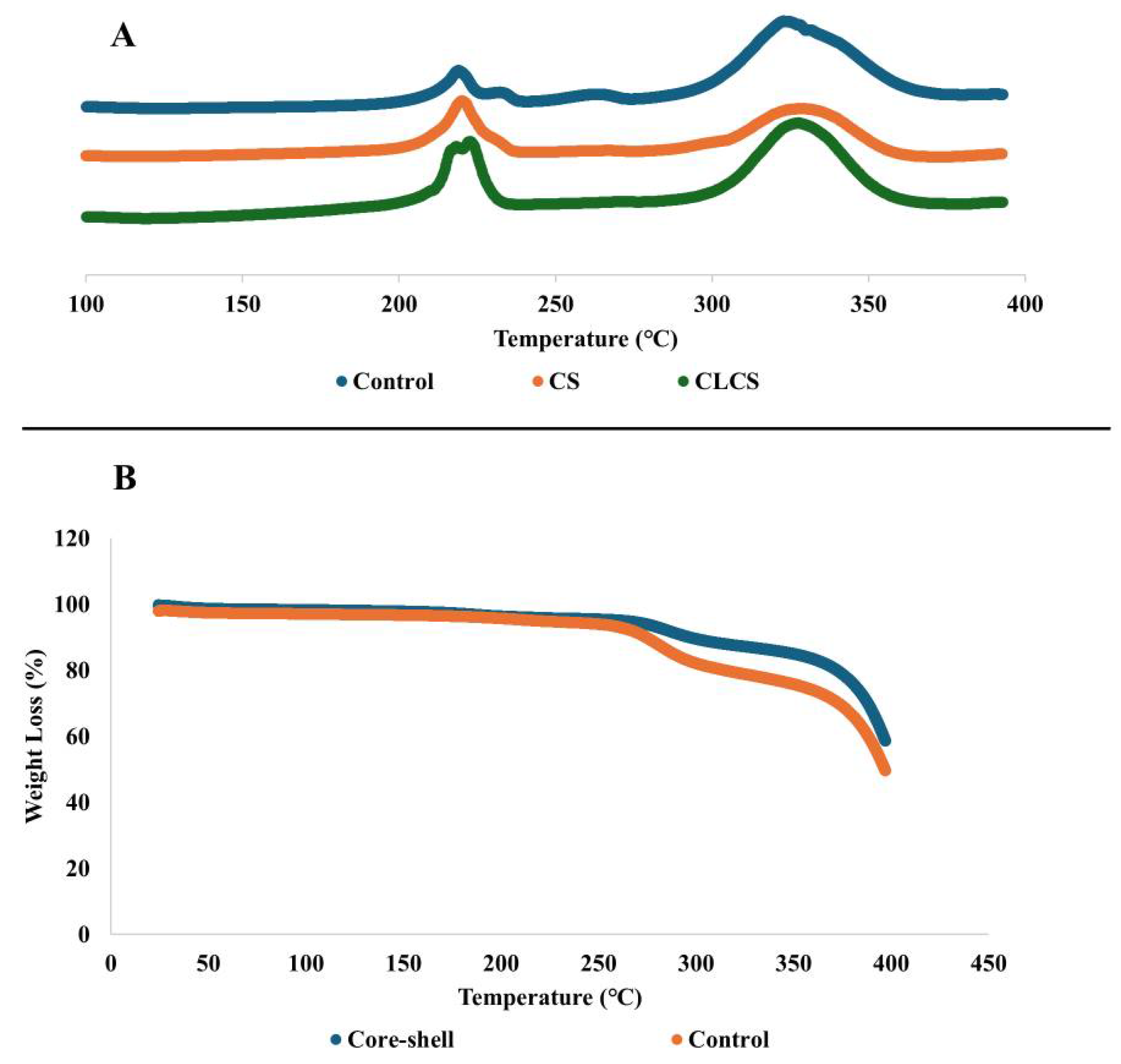

3.3. Thermal Analysis of Nanomembranes

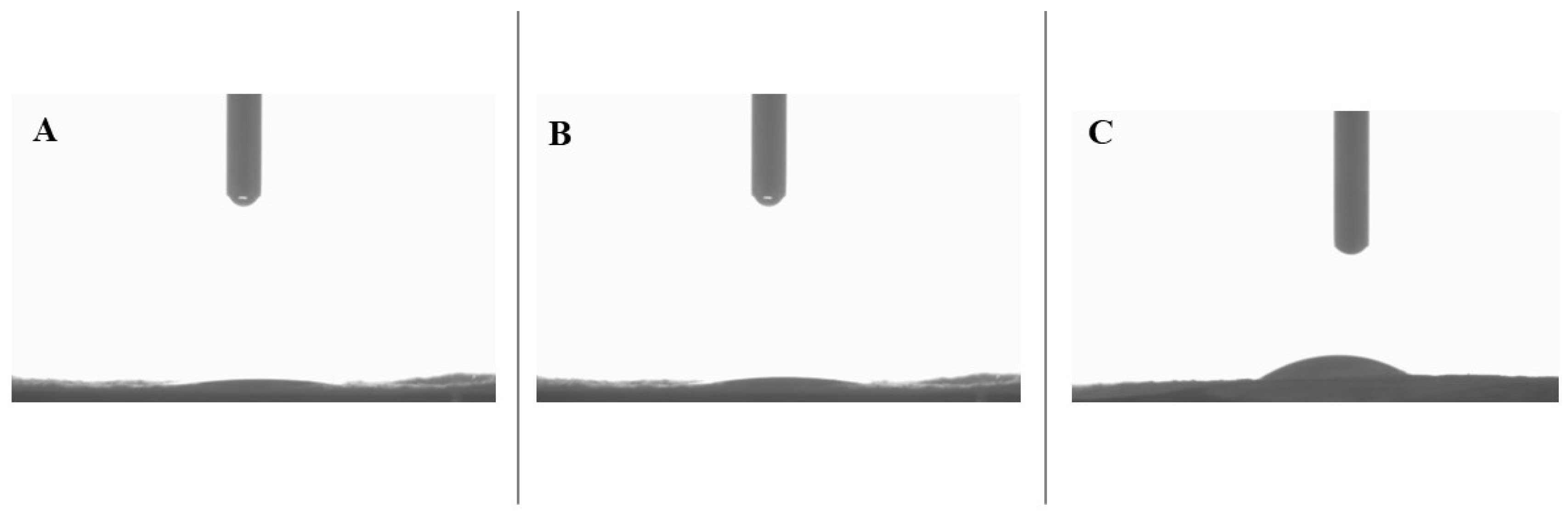

3.4. Static Water Contact Angle

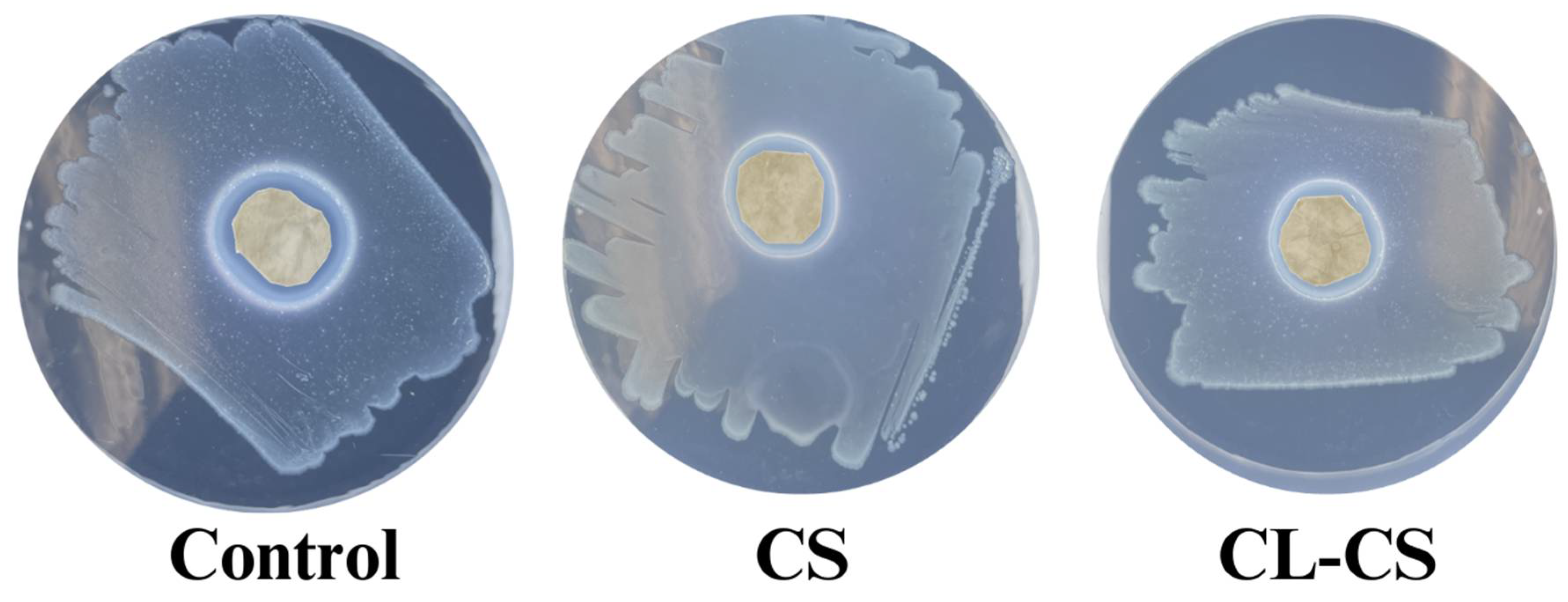

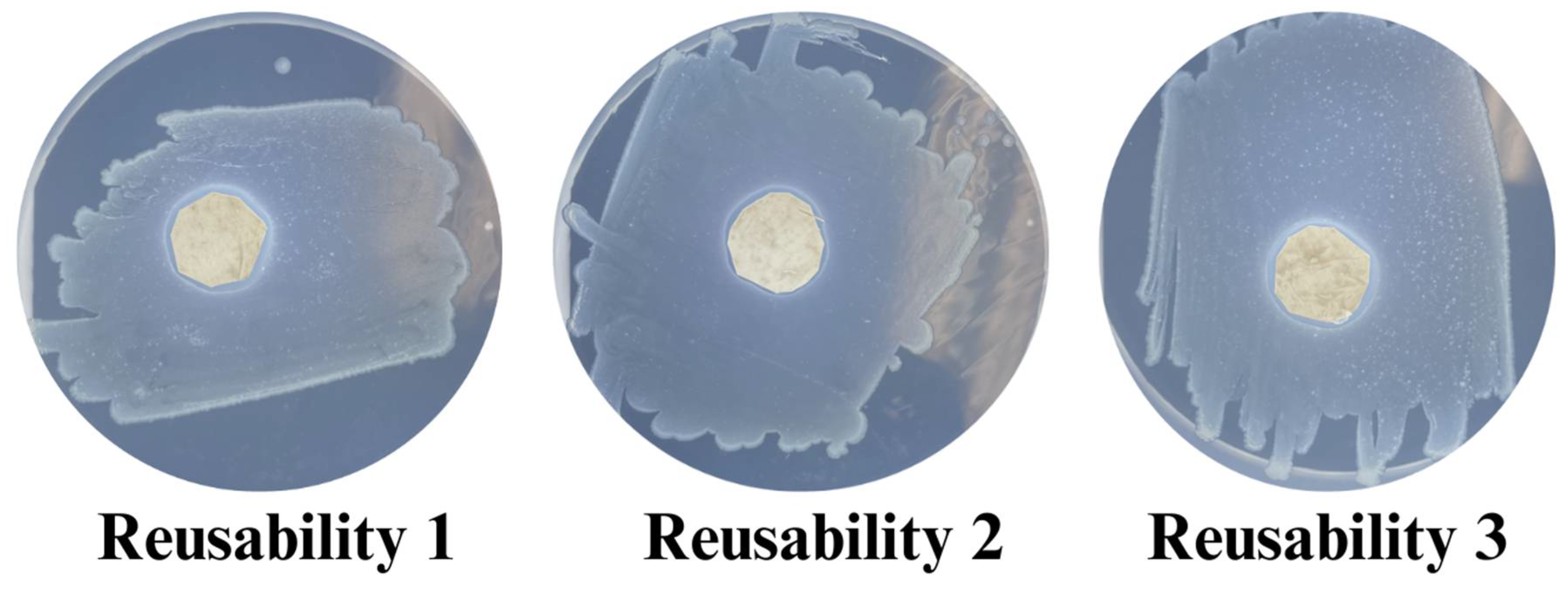

3.5. Antimicrobial Behavior of Nanomembranes

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stokes, K.; Peltrini, R.; Bracale, U.; Trombetta, M.; Pecchia, L.; Basoli, F. Enhanced medical and community face masks with antimicrobial properties: A systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, V.; Jose, S.; Badanayak, P.; Sankaran, A.; Anandan, V. Antimicrobial finishing of metals, metal oxides, and metal composites on textiles: A systematic review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.; Kidanemariam, A.; Lee, D.; Pham, T.T.D.; Park, J. Durability of antimicrobial agent on nanofiber: A collective review from 2018 to 2022. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2024, 130, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simončič, B.; Klemenčič, D. Preparation and performance of silver as an antimicrobial agent for textiles: A review. Text. Res. J. 2016, 86, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karypidis, M.; Karanikas, E.; Papadaki, A.; Andriotis, E.G. A mini-review of synthetic organic and nanoparticle antimicrobial agents for coatings in textile applications. Coatings 2023, 13, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencova, S.; Stiborova, H.; Munzarova, M.; Demnerova, K.; Zdenkova, K. Potential of Polyamide Nanofibers With Natamycin, Rosemary Extract, and Green Tea Extract in Active Food Packaging Development: Interactions With Food Pathogens and Assessment of Microbial Risks Elimination. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 857423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanzada, H.; Salam, A.; Qadir, M.B.; Phan, D.N.; Hassan, T.; Munir, M.U.; Pasha, K.; Hassan, N.; Khan, M.Q.; Kim, I.S. Fabrication of promising antimicrobial aloe vera/PVA electrospun nanofibers for protective clothing. Materials 2020, 13, 3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; El-Moghazy, A.Y.; Wisuthiphaet, N.; Nitin, N.; Castillo, D.; Murphy, B.G.; Sun, G. Daylight-induced antibacterial and antiviral nanofibrous membranes containing vitamin K derivatives for personal protective equipment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 49416–49430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallakpour, S.; Azadi, E.; Hussain, C.M. Protection, disinfection, and immunization for healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic: Role of natural and synthetic macromolecules. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Chen, X.; Jia, F.; Wang, S.; Xiao, C.; Cui, F.; Li, Y.; Bian, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, X. New chemosynthetic route to linear ε-poly-lysine. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 6385–6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, N.A.; Kandasubramanian, B. Functionalized polylysine biomaterials for advanced medical applications: A review. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 146, 110248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, S.; Matsuoka, H.; Iwamoto, T.; Sakai, H. Antimicrobial action of ε-poly-L-lysine. J. Antibiot. 1984, 37, 1449–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amariei, G.; Kokol, V.; Vivod, V.; Boltes, K.; Letón, P.; Rosal, R. Biocompatible antimicrobial electrospun nanofibers functionalized with ε-poly-l-lysine. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 553, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayandi, V.; Wen Choong, A.C.; Dhand, C.; Lim, F.P.; Aung, T.T.; Sriram, H.; Dwivedi, N.; Periayah, M.H.; Sridhar, S.; Fazil, M.H.U.T.; et al. Multifunctional antimicrobial nanofiber dressings containing ε-polylysine for the eradication of bacterial bioburden and promotion of wound healing in critically colonized wounds. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 15989–16005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Xue, L.; Duraiarasan, S.; Haiying, C. Preparation of ε-polylysine/chitosan nanofibers for food packaging against Salmonella on chicken. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 17, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wang, D.; Wu, H.; Du, L.; Wang, D. Preparation and antibacterial properties of ε-polylysine-containing gelatin/chitosan nanofiber films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 3376–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Y.J.; Robles, J.R.; Sinha-Ray, S.; Abiade, J.; Pourdeyhimi, B.; Niemczyk-Soczynska, B.; Kolbuk, D.; Sajkiewicz, P.; Yarin, A.L. Solution-blown poly (hydroxybutyrate) and ε-poly-l-lysine submicro-and microfiber-based sustainable nonwovens with antimicrobial activity for single-use applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 3980–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souri, Z.; Hedayati, S.; Niakousari, M.; Mazloomi, S.M. Fabrication of ɛ-Polylysine-Loaded Electrospun Nanofiber Mats from Persian Gum–Poly (Ethylene Oxide) and Evaluation of Their Physicochemical and Antimicrobial Properties. Foods 2023, 12, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, H.; Shi, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Yu, J.; Fan, Y. Preparation of amino cellulose nanofiber via ε-poly-L-lysine grafting with enhanced mechanical, anti-microbial and food preservation performance. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 194, 116288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purandare, S.; Li, R.; Xiang, C.; Song, G. Development of Innovative Composite Nanofiber: Enhancing Polyamide-6 with ε-Poly-L-Lysine for Medical and Protective Textiles. Polymers 2024, 16, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, F.; Wang, F.P.; Xie, Y.Y.; Chu, L.Q.; Jia, S.R.; Duan, Y.X.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, C. Reusable ternary PVA films containing bacterial cellulose fibers and ε-polylysine with improved mechanical and antibacterial properties. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 183, 110486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Lee, Y.K.; Lee, Y.; Hwang, W.T.; Lee, J.; Park, S.; Song, H.; Kim, H.; Lee, K.G.; Kim, I.-D.; et al. Anti-viral, anti-bacterial, but non-cytotoxic nanocoating for reusable face mask with efficient filtration, breathability, and robustness in humid environment. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Wu, T.; Dai, Y.; Xia, Y. Electrospinning and electrospun nanofibers: Methods, materials, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 5298–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, W.E.; Ramakrishna, S. A review on electrospinning design and nanofiber assemblies. Nanotechnology 2006, 17, R89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, J.; Cheng, H.; Li, G.; Cho, H.; Jiang, M.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, X. Developments of advanced electrospinning techniques: A critical review. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021, 6, 2100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulubayram, K.; Calamak, S.; Shahbazi, R.; Eroglu, I. Nanofibers based antibacterial drug design, delivery and applications. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 1930–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, A.; Shaibani, P.Á.; Etayash, H.; Kaur, K.; Thundat, T. Sustained drug release and antibacterial activity of ampicillin incorporated poly (methyl methacrylate)–nylon6 core/shell nanofibers. Polymer 2013, 54, 2699–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Ghosh, C.; Hwang, S.G.; Chanunpanich, N.; Park, J.S. Porous core/sheath composite nanofibers fabricated by coaxial electrospinning as a potential mat for drug release system. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 439, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matulevicius, J.; Kliucininkas, L.; Martuzevicius, D.; Krugly, E.; Tichonovas, M.; Baltrusaitis, J. Design and characterization of electrospun polyamide nanofiber media for air filtration applications. J. Nanomater. 2014, 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencova, S.; Svarcova, V.; Stiborova, H.; Demnerova, K.; Jencova, V.; Hozdova, K.; Zdenkova, K. Bacterial biofilms on polyamide nanofibers: Factors influencing biofilm formation and evaluation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 13, 2277–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Frey, M.W. Increasing mechanical properties of 2-D-structured electrospun nylon 6 non-woven fiber mats. Materials 2016, 9, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Morales, J.; Amariei, G.; Letón, P.; Rosal, R. Antimicrobial activity of poly (vinyl alcohol)-poly (acrylic acid) electrospun nanofibers. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2016, 146, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Luo, T.; Zhong, Z.; Huang, D.; Liang, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Tang, Y. Green cross-linking of gelatin/tea polyphenol/ε-poly (L-lysine) electrospun nanofibrous membrane for edible and bioactive food packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 34, 100970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7334-08; Standard Practice for Surface Wettability of Coatings, Substrates and Pigments by Advancing Contact Angle Measurement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008.

- AATCC TM147; Antibacterial Activity Assessment of Textile Materials: Parallel Streak Method. American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists: Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2011.

- Xiong, S.W.; Fu, P.G.; Zou, Q.; Chen, L.Y.; Jiang, M.Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Z.-G.; Cui, L.-S.; Guo, H.; Gai, J.G. Heat conduction and antibacterial hexagonal boron nitride/polypropylene nanocomposite fibrous membranes for face masks with long-time wearing performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 13, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koombhongse, S.; Liu, W.; Reneker, D.H. Flat polymer ribbons and other shapes by electrospinning. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2001, 39, 2598–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, H.; Li, Y.; Chan, K.H.; Kotaki, M. Morphology and mechanical properties of PVA nanofibers spun by free surface electrospinning. Polym. Bull. 2016, 73, 2761–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, R.; Dong, F.; Tian, A.; Li, Z.; Dai, Y. Physical, mechanical and antimicrobial properties of starch films incorporated with ε-poly-l-lysine. Food Chem. 2015, 166, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Sun, J.; Lu, Y.; Wu, T.; Pang, J.; Hu, Y. In situ self-assembly chitosan/ε-polylysine bionanocomposite film with enhanced antimicrobial properties for food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 132, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotter, G.; Ishida, H. FTIR separation of nylon-6 chain conformations: Clarification of the mesomorphous and γ-crystalline phases. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 1992, 30, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, B.; Kawakami, T.; Shigemoto, I.; Sugita, Y.; Yagi, K. Weight-averaged anharmonic vibrational analysis of hydration structures of polyamide 6. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 6050–6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, L.; Xu, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Shinoda, M.; Kishimoto, M.; Tanaka, T.; Yamane, H. Effect of the Application of a Dehydrothermal Treatment on the Structure and the Mechanical Properties of Collagen Film. Materials 2020, 13, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lan, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Tian, F.; Li, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Tang, Y. Preparation and in vitro evaluation of ε-poly (L-lysine) immobilized poly (ε-caprolactone) nanofiber membrane by polydopamine-assisted decoration as a potential wound dressing material. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 220, 112945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunaratne, L.M.W.K.; Shanks, R.A. Multiple melting behaviour of poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate) using step-scan DSC. Eur. Polym. J. 2005, 41, 2980–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asran, A.S.; Razghandi, K.; Aggarwal, N.; Michler, G.H.; Groth, T. Nanofibers from blends of polyvinyl alcohol and polyhydroxy butyrate as potential scaffold material for tissue engineering of skin. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 3413–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yan, K.W.; Lin, Y.D.; Hsieh, P.C. Biodegradable core/shell fibers by coaxial electrospinning: Processing, fiber characterization, and its application in sustained drug release. Macromolecules 2015, 43, 6389–6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liu, C.; Hsu, P.C.; Xu, J.; Kong, B.; Wu, T.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, G.; Huang, W.; Cui, Y. Core–shell nanofibrous materials with high particulate matter removal efficiencies and thermally triggered flame retardant properties. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 894–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Sun, D. Potential of rhBMP-2 and dexamethasone-loaded Zein/PLLA scaffolds for enhanced in vitro osteogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 169, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, H.F.; Luqman, M.; Khalil, K.A.; Elnakady, Y.A.; Abd-Elkader, O.H.; Rady, A.M.; Alharthi, N.H.; Karim, M.R. Fabrication of core-shell structured nanofibers of poly (lactic acid) and poly (vinyl alcohol) by coaxial electrospinning for tissue engineering. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 98, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Su, Y.; He, C.; Wang, H.; Fong, H.; Mo, X. Sorbitan monooleate and poly (l-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) electrospun nanofibers for endothelial cell interactions. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A Off. J. Soc. Biomater. Jpn. Soc. Biomater. Aust. Soc. Biomater. Korean Soc. Biomater. 2008, 91, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Tao, Y. Poly (ε-lysine) and its derivatives via ring-opening polymerization of biorenewable cyclic lysine. Polym. Chem. 2021, 12, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Sun, L.; Zhao, B.; Fang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Ning, G.; Ye, J. Reusable electrospun nanofibrous membranes with antibacterial activity for air filtration. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 10872–10880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riga, E.K.; Vöhringer, M.; Widyaya, V.T.; Lienkamp, K. Polymer-Based Surfaces Designed to Reduce Biofilm Formation: From Antimicrobial Polymers to Strategies for Long-Term Applications. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2017, 38, 1700216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, M.; Yang, S.Y.; Asmatulu, R. Effects of gentamicin-loaded PCL nanofibers on growth of Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria. Int. J. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Res. 2017, 5, 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Takehara, M.; Hirohara, H. Occurrence and production of poly-epsilon-l-lysine in microorganisms. In Amino-Acid Homopolymers Occurring in Nature; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, R.; Devenney, W.; Siegel, S.; Dan, N. Anomalous release of hydrophilic drugs from poly (ϵ-caprolactone) matrices. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.Y.; Wang, P.F.; Li, H.X.; Yang, Y.J.; Rao, S.Q. Enhanced Antibacterial Efficiency and Anti-Hygroscopicity of Gum Arabic–ε-Polylysine Electrostatic Complexes: Effects of Thermal Induction. Polymers 2003, 15, 4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Average Core Diameter (nm) | Average Shell Thickness (nm) |

|---|---|

| 196.79 ± 27.63 | 114.48 ± 34.14 |

| Sample | Average Diameter (Microns) |

|---|---|

| Control | 0.49 ± 0.07 |

| CS | 0.62 ± 0.32 |

| CL-CS | 0.40 ± 0.12 |

| Sample | N/O Ratio |

|---|---|

| Control | 0.750 |

| CS | 0.610 |

| CL-CS | 0.430 |

| Sample | Diameter of Zone of Inhibition (cm2) |

|---|---|

| Control | 1.347 ± 0.151 a |

| CS | 1.265 ± 0.042 a |

| CL-CS | 1.128 ± 0.161 a |

| Sample | Diameter of Zone of Inhibition (cm2) |

|---|---|

| Control | 1.027 ± 0.072 a |

| CS | 1.052 ± 0.235 a |

| CL-CS | 1.106 ± 0.047 a |

| Antimicrobial Test | Diameter of Zone of Inhibition (cm2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Before Reusability Tests | 1.128 ± 0.161 a | |

| After Reusability Tests | Cycle 1 | 1.009 ± 0.119 a |

| Cycle 2 | 0.963 ± 0.043 a | |

| Cycle 3 | 0.941 ± 0.048 a | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Purandare, S.; Li, R.; Xiang, C.; Song, G. Novel Core–Shell Nanostructure of ε-Poly-L-lysine and Polyamide-6 Polymers for Reusable and Durable Antimicrobial Function. Polymers 2025, 17, 3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233195

Purandare S, Li R, Xiang C, Song G. Novel Core–Shell Nanostructure of ε-Poly-L-lysine and Polyamide-6 Polymers for Reusable and Durable Antimicrobial Function. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233195

Chicago/Turabian StylePurandare, Saloni, Rui Li, Chunhui Xiang, and Guowen Song. 2025. "Novel Core–Shell Nanostructure of ε-Poly-L-lysine and Polyamide-6 Polymers for Reusable and Durable Antimicrobial Function" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233195

APA StylePurandare, S., Li, R., Xiang, C., & Song, G. (2025). Novel Core–Shell Nanostructure of ε-Poly-L-lysine and Polyamide-6 Polymers for Reusable and Durable Antimicrobial Function. Polymers, 17(23), 3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233195