Dual-Triggered Release Mechanisms in Calcium Alginate/Fe3O4 Capsules for Asphalt Self-Healing: Cyclic Load-Induced Sustained Release and Microwave-Activated On-Demand Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

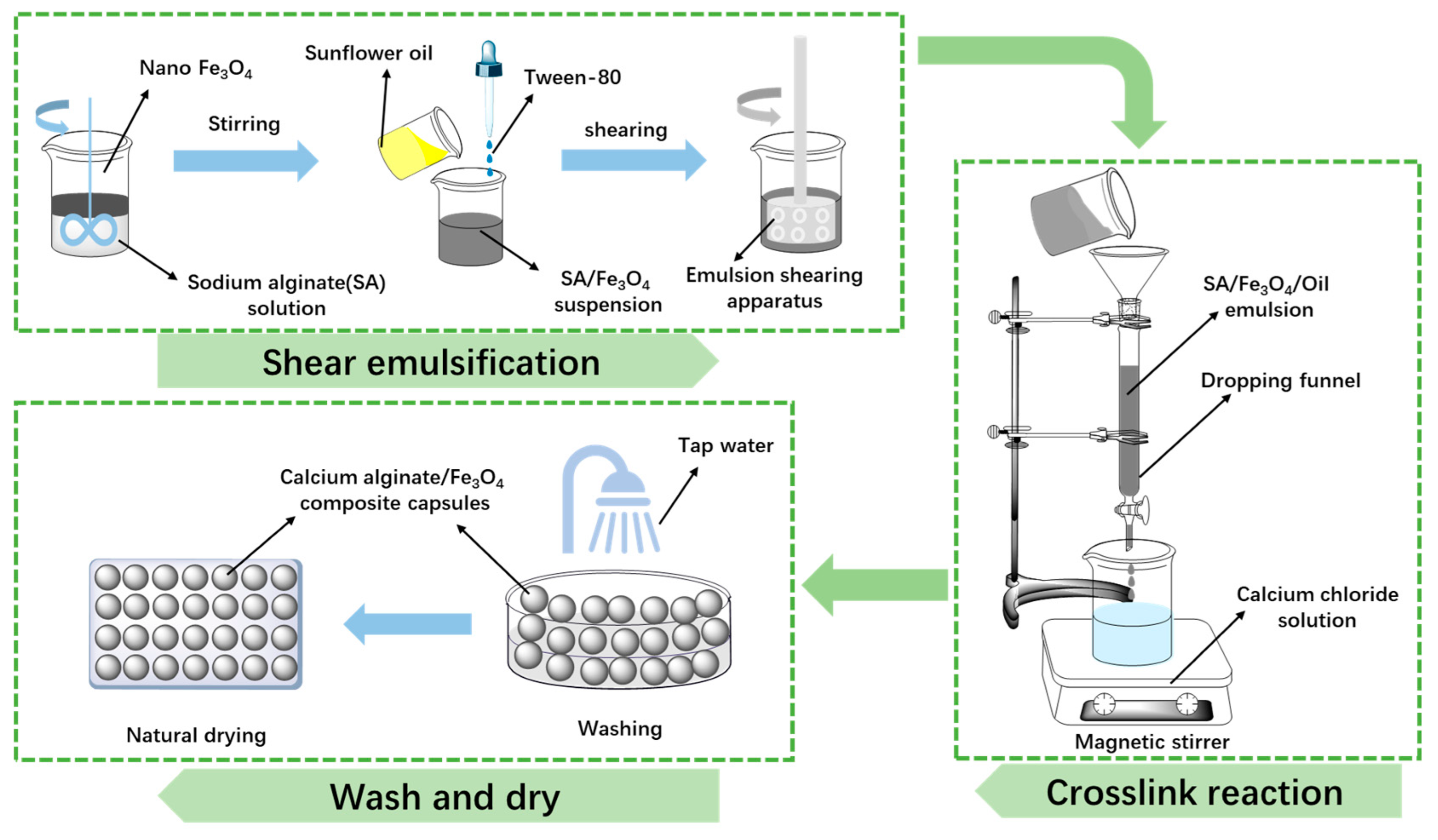

2.2. Preparation of Calcium Alginate/Fe3O4 Capsules

2.3. Characterization of Prepared Capsules

2.4. Production of Bitumen Concrete with Capsules

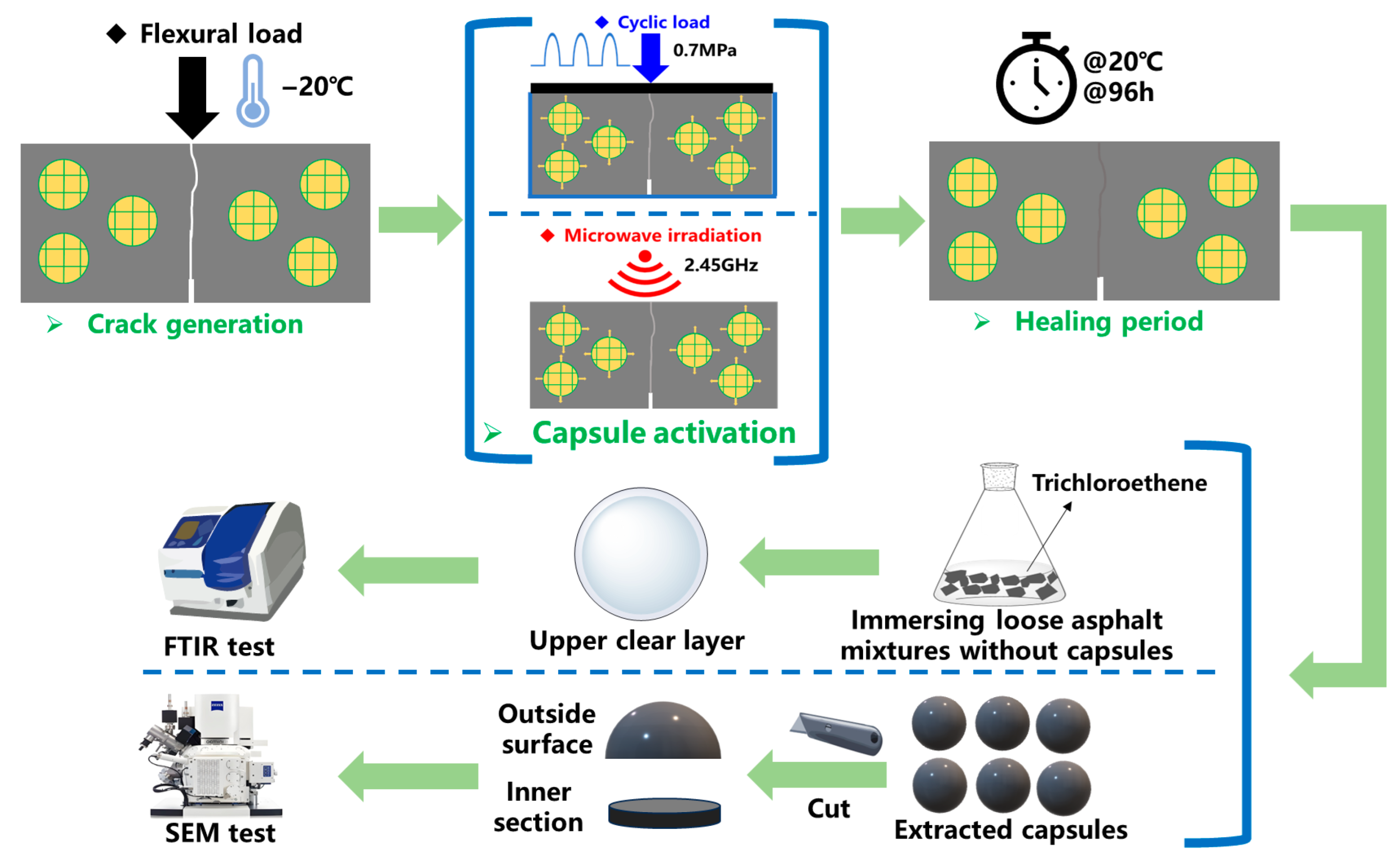

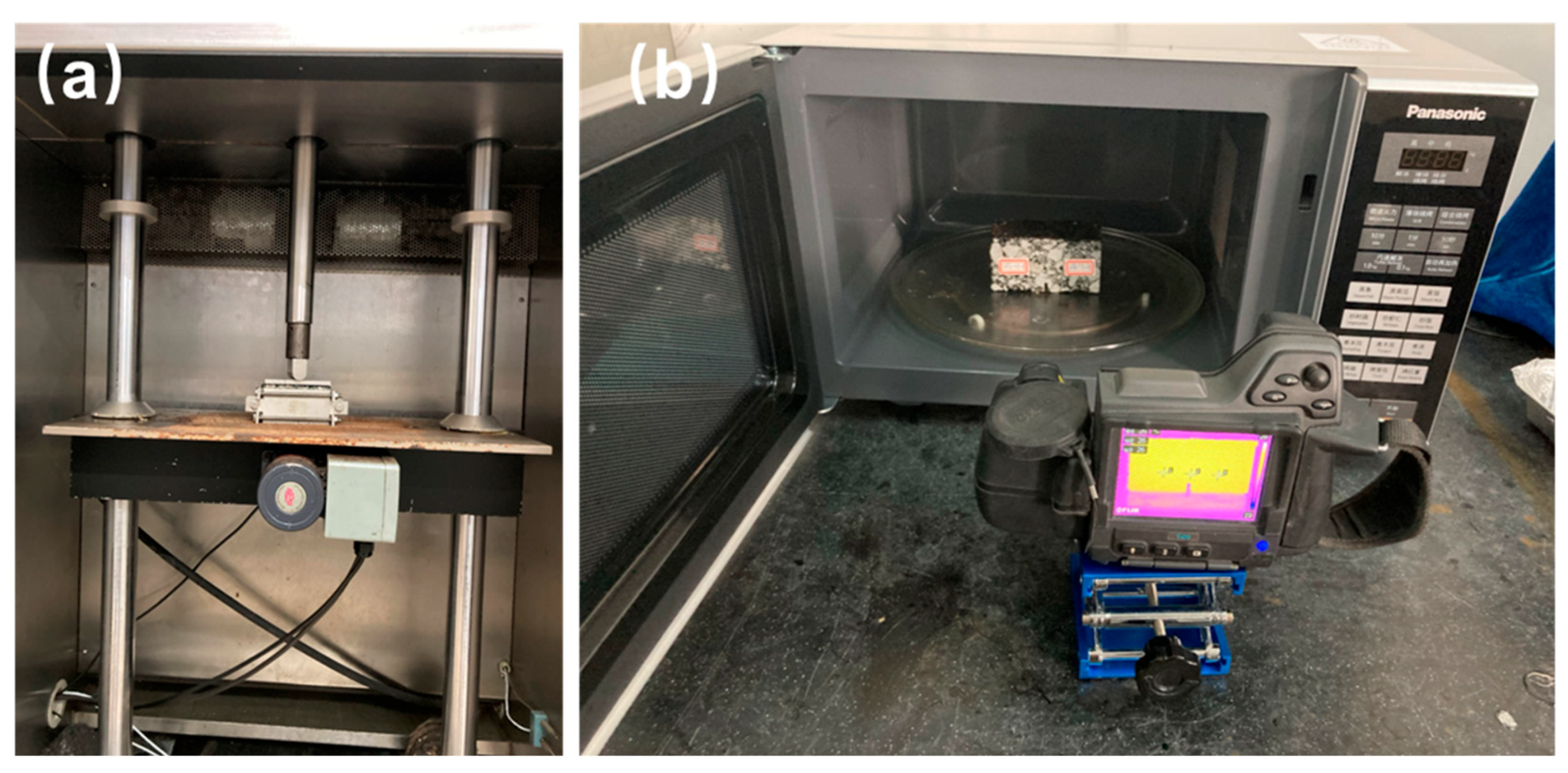

2.5. External Activation for Bitumen Concrete with Capsules

2.6. Characterization of the Internal Structure and Rejuvenator Discharge Degree of Capsules After Cyclic Load and Microwave Irradiation

3. Results and Discussion

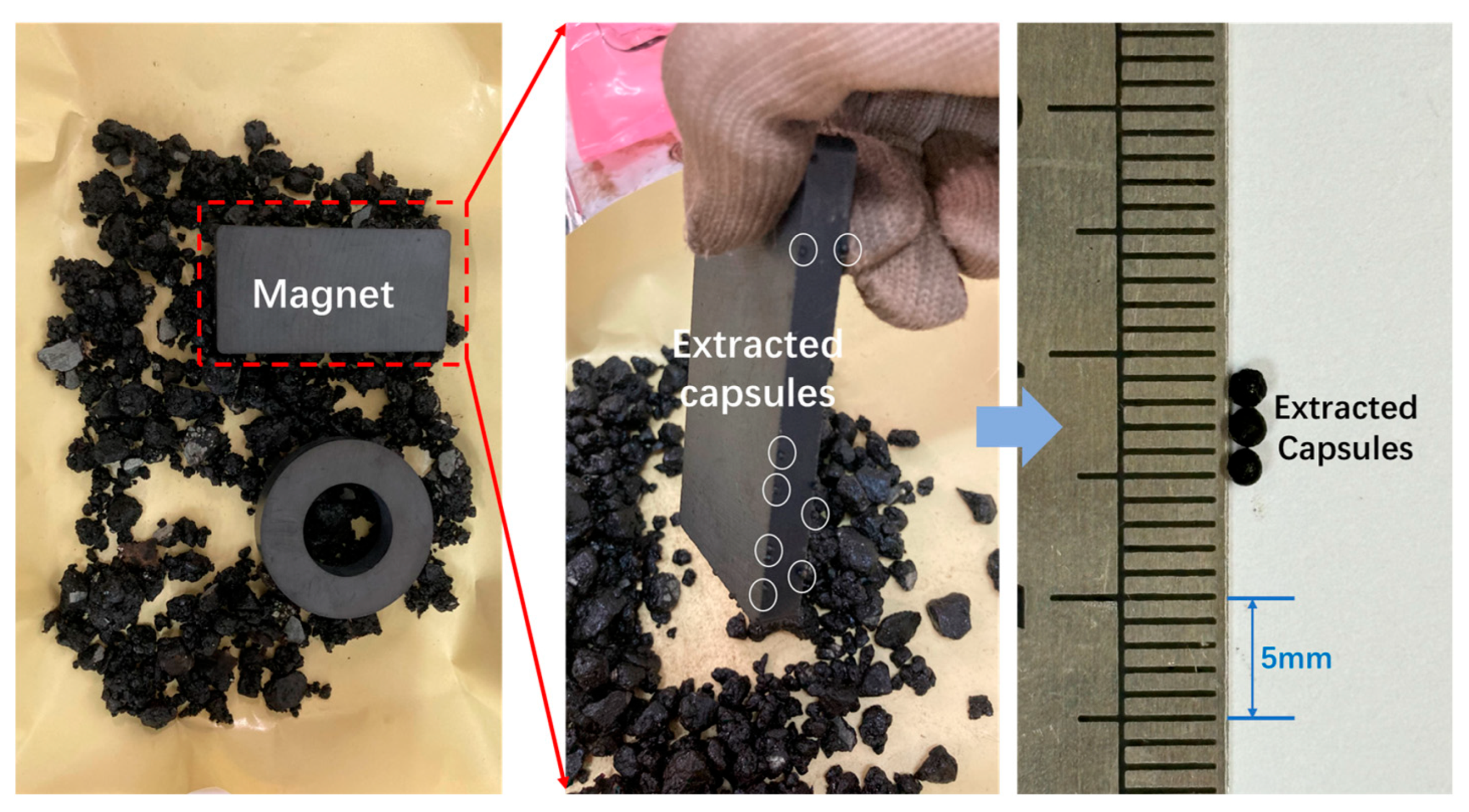

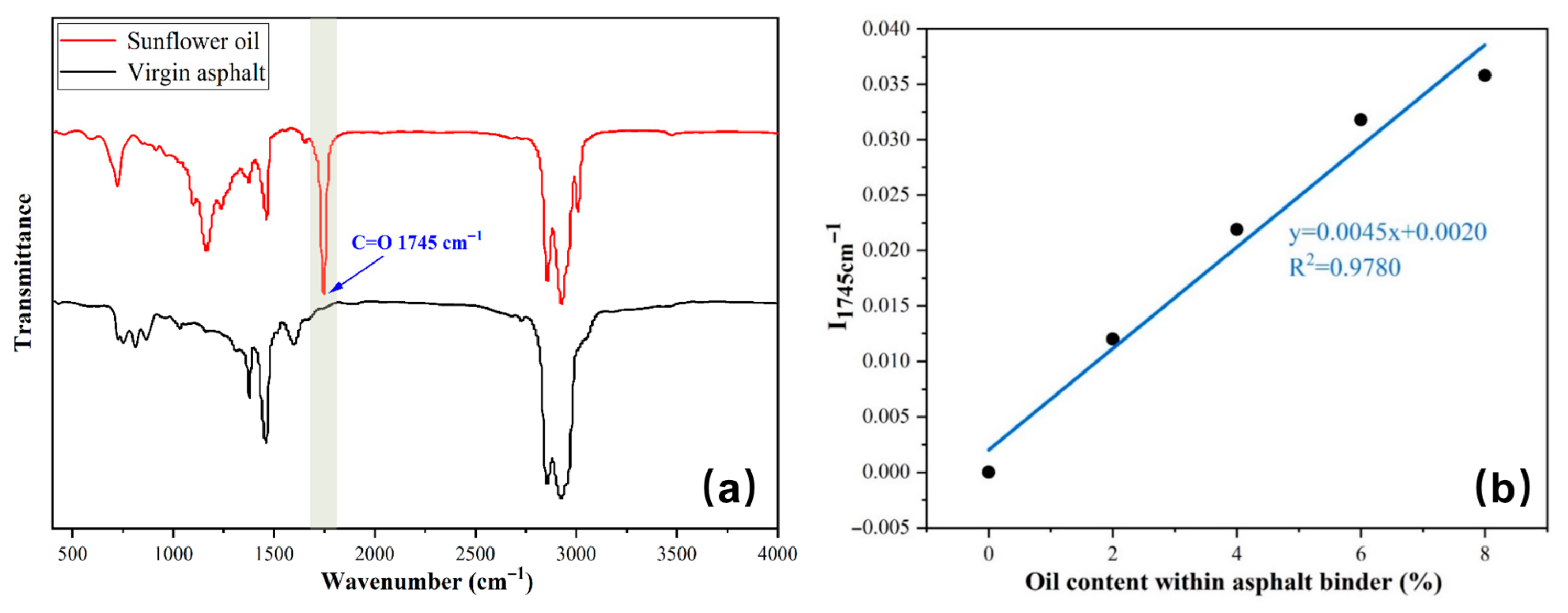

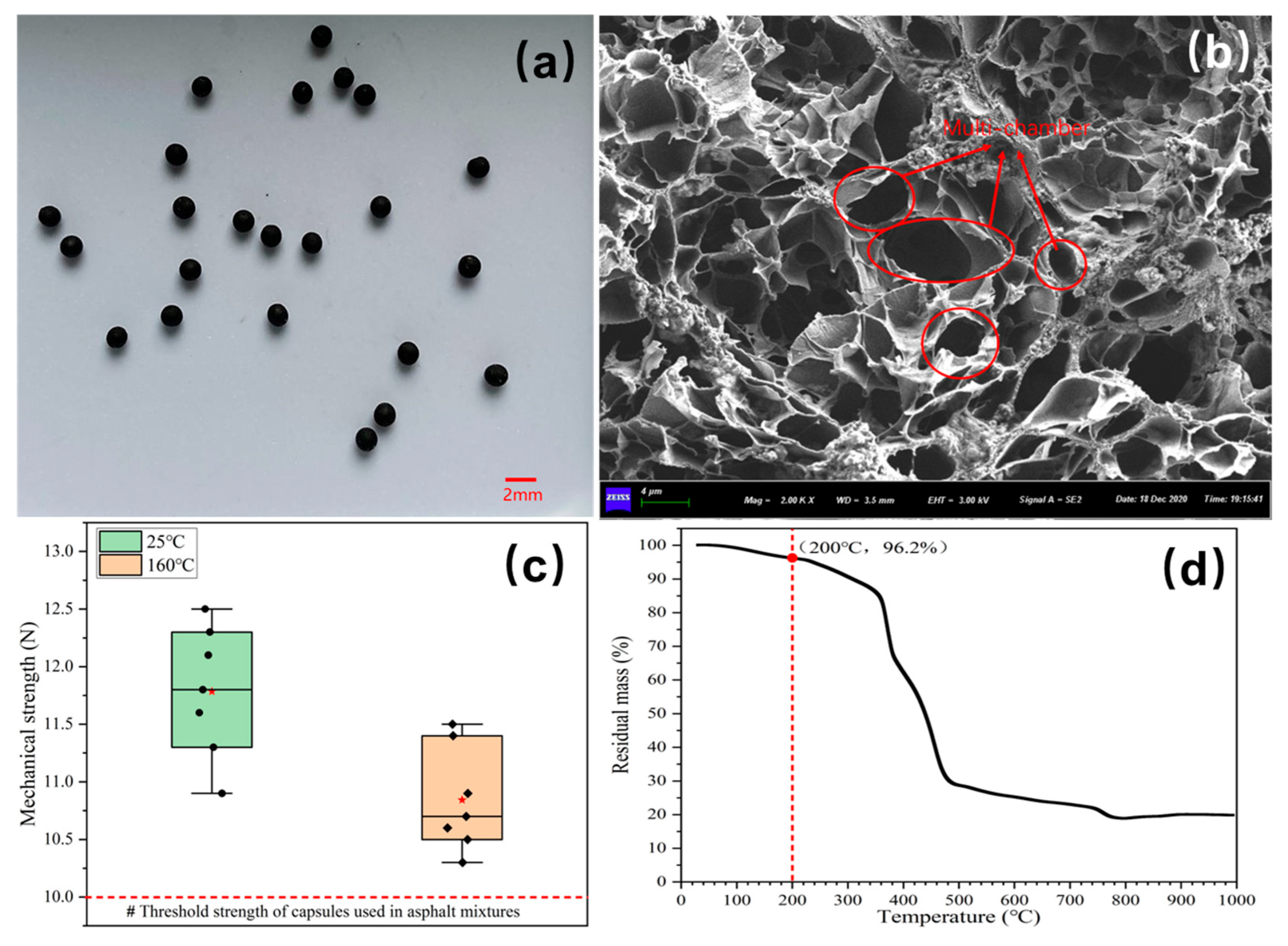

3.1. Fundamental Properties of Prepared Ca-Alginate/Fe3O4 Capsules

3.2. Rejuvenator Discharge Ratios of Capsules After Two Forms of Activation

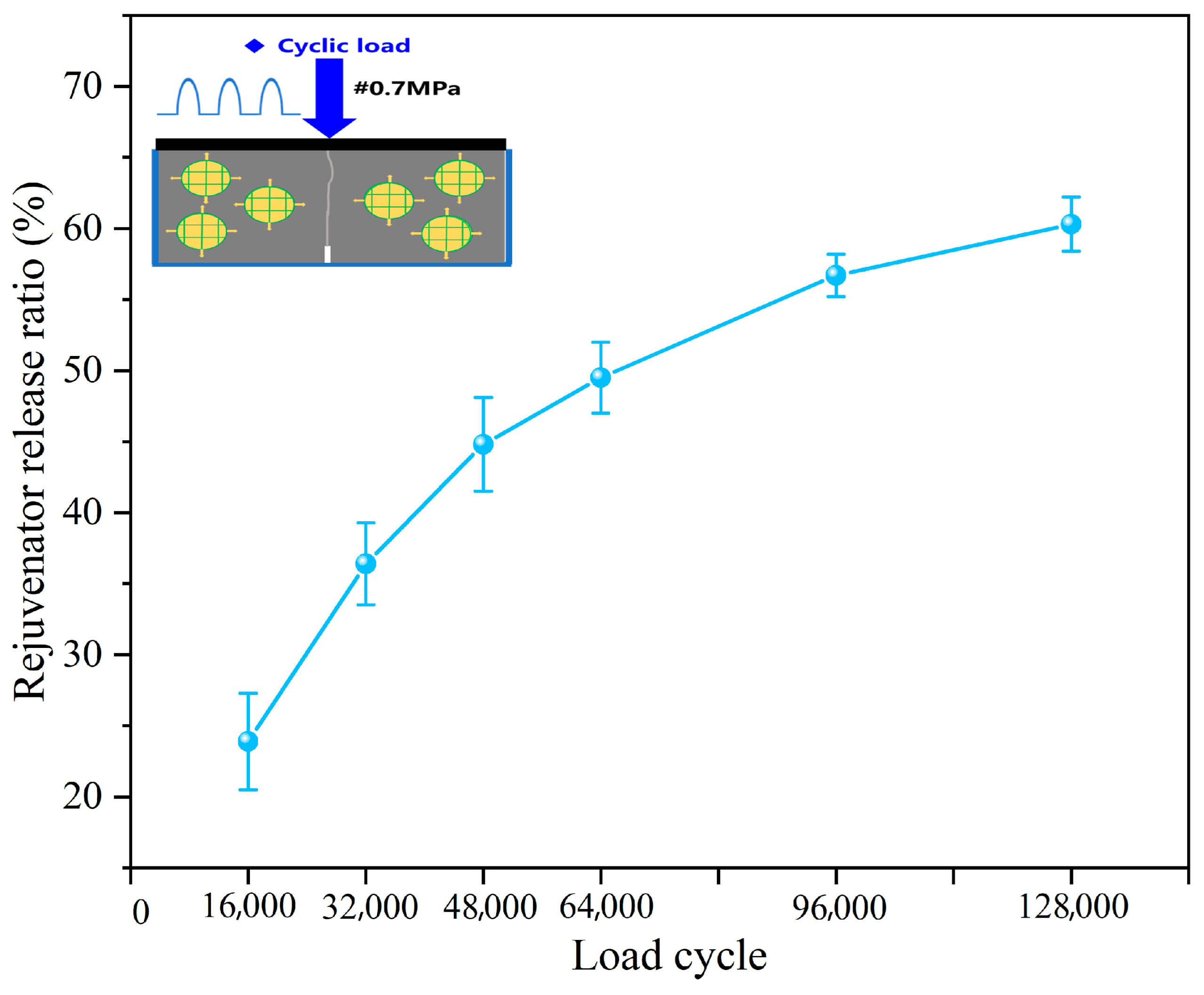

3.2.1. Rejuvenator Discharge Ratios of Capsules After Cyclic Load

3.2.2. Rejuvenator Discharge Ratios of Capsules After Microwave Irradiation

3.3. The Structure Characteristics of Capsules Extracted from Bitumen Beams After Two Types of External Activation

3.3.1. The Structure Feature of Capsules Extracted from Bitumen Beams After Cyclic Load

The Structure Feature of Outer Wall of Capsules Extracted from Bitumen Beams After Cyclic Load

The Structure Feature of the Internal Chamber of Capsules Extracted from Bitumen Beams After Cyclic Load

3.3.2. The Structure Features of Capsules Extracted from Bitumen Beams After Microwave Irradiation

The Structure Features of Outer Wall of Capsules Extracted from Concrete Beams Following Microwave Exposure

The Structure Feature of Internal Chamber of Capsules Extracted from Concrete Beams After Microwave Exposure

3.4. The Rejuvenator Discharge Mechanism of Capsules in Bitumen Concrete Under Two Types of External Activation

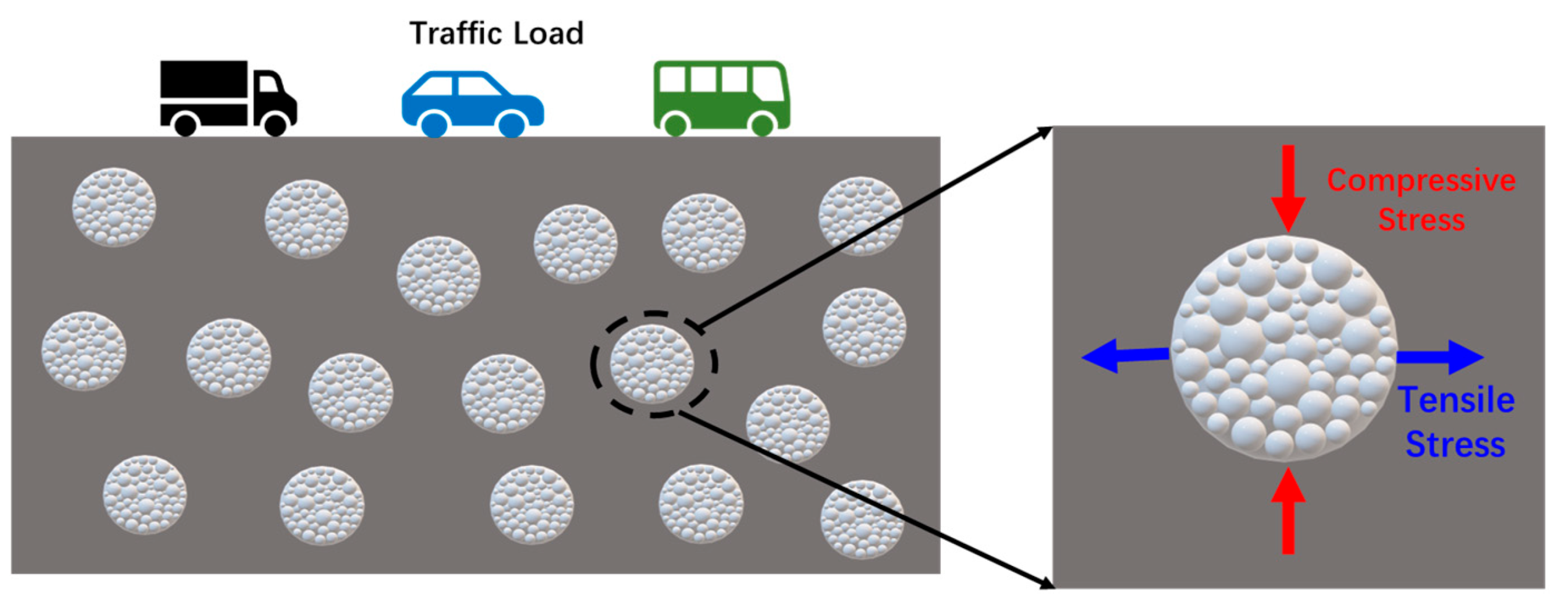

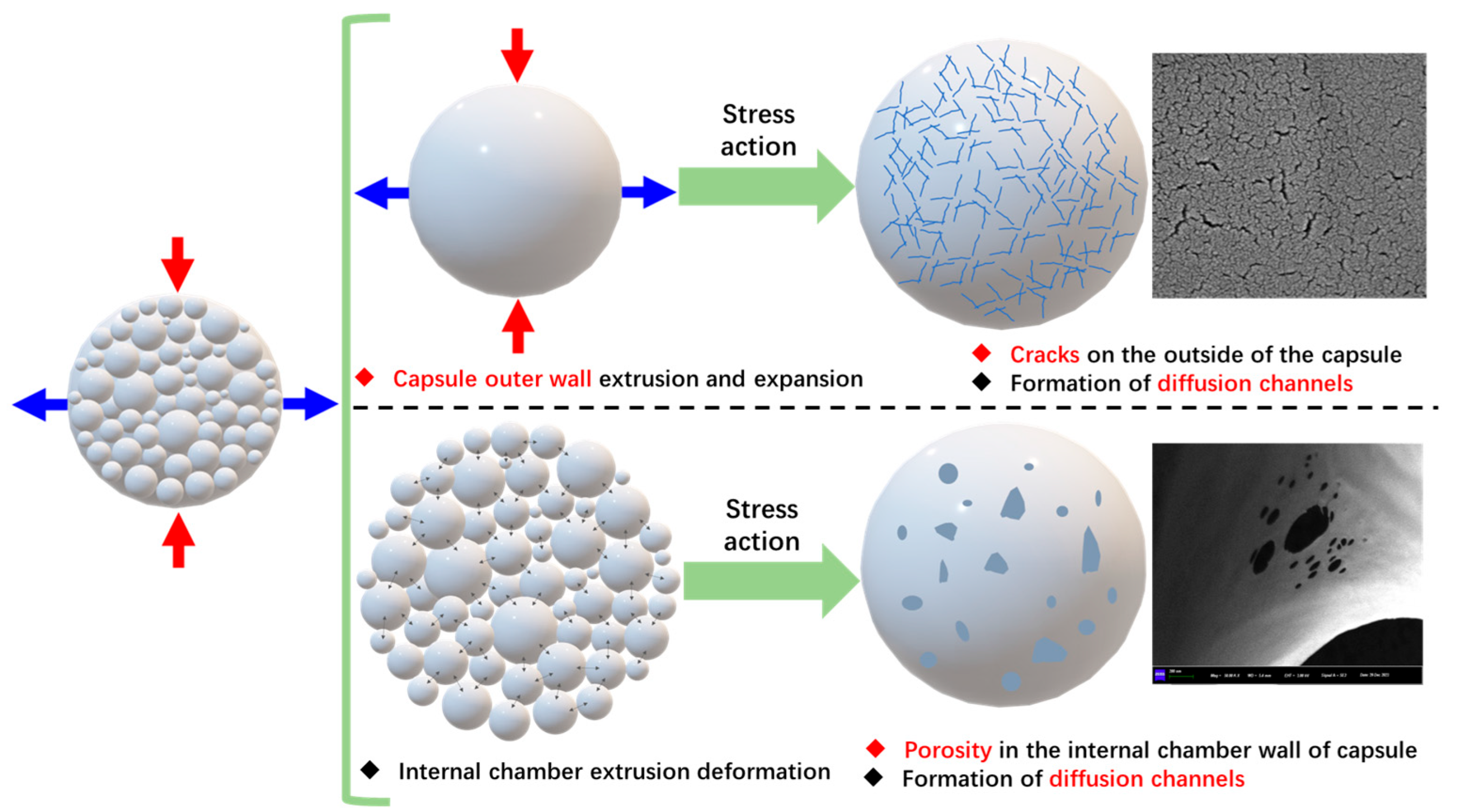

3.4.1. The Rejuvenator Discharge Mechanism of Capsules in Asphalt Concrete Under Cyclic Load

3.4.2. The Rejuvenator Discharge Mechanism of Capsules in Asphalt Concrete Under Microwave Exposure

4. Conclusions

- The prepared Ca-alginate/Fe3O4 capsules possess multi-chamber organization. The capsules exhibit a mechanical strength of 11.8 N and experience a mass loss of 3.8% at 200 °C. These results satisfy the requirements of asphalt concrete manufacture.

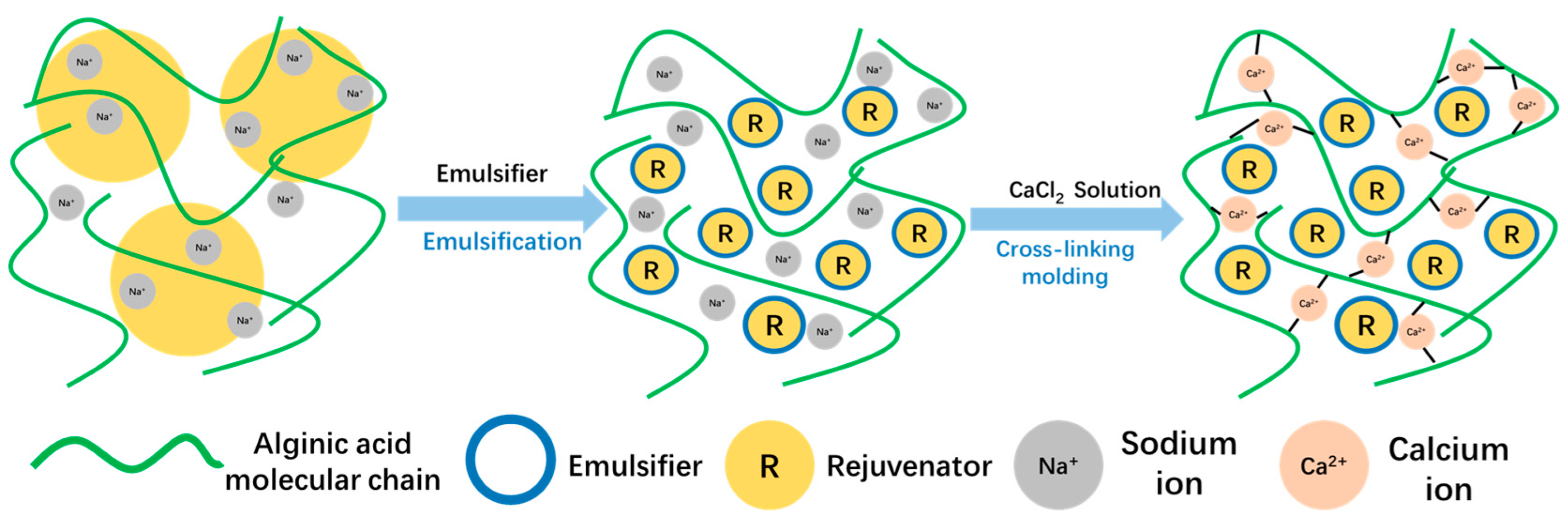

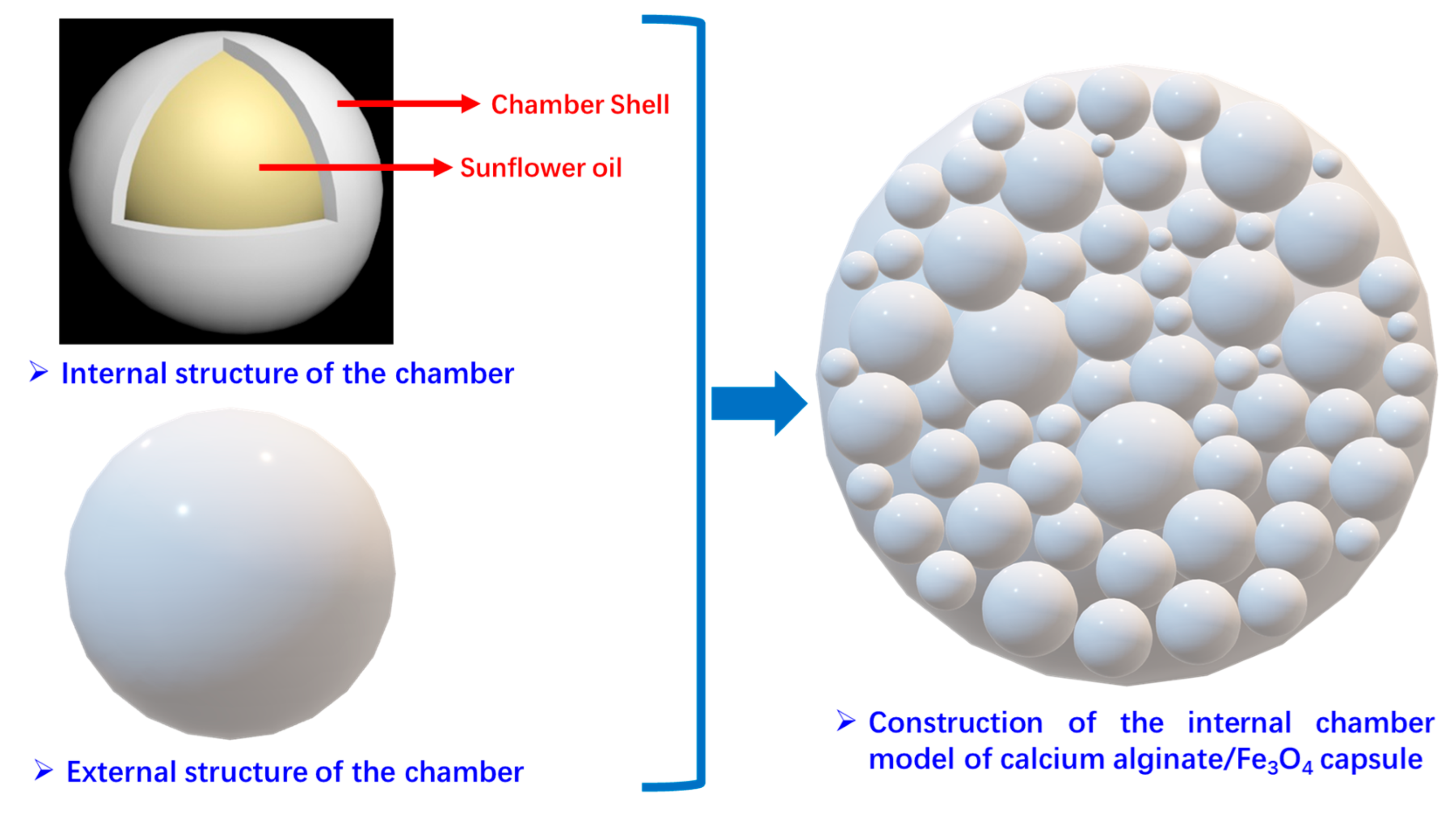

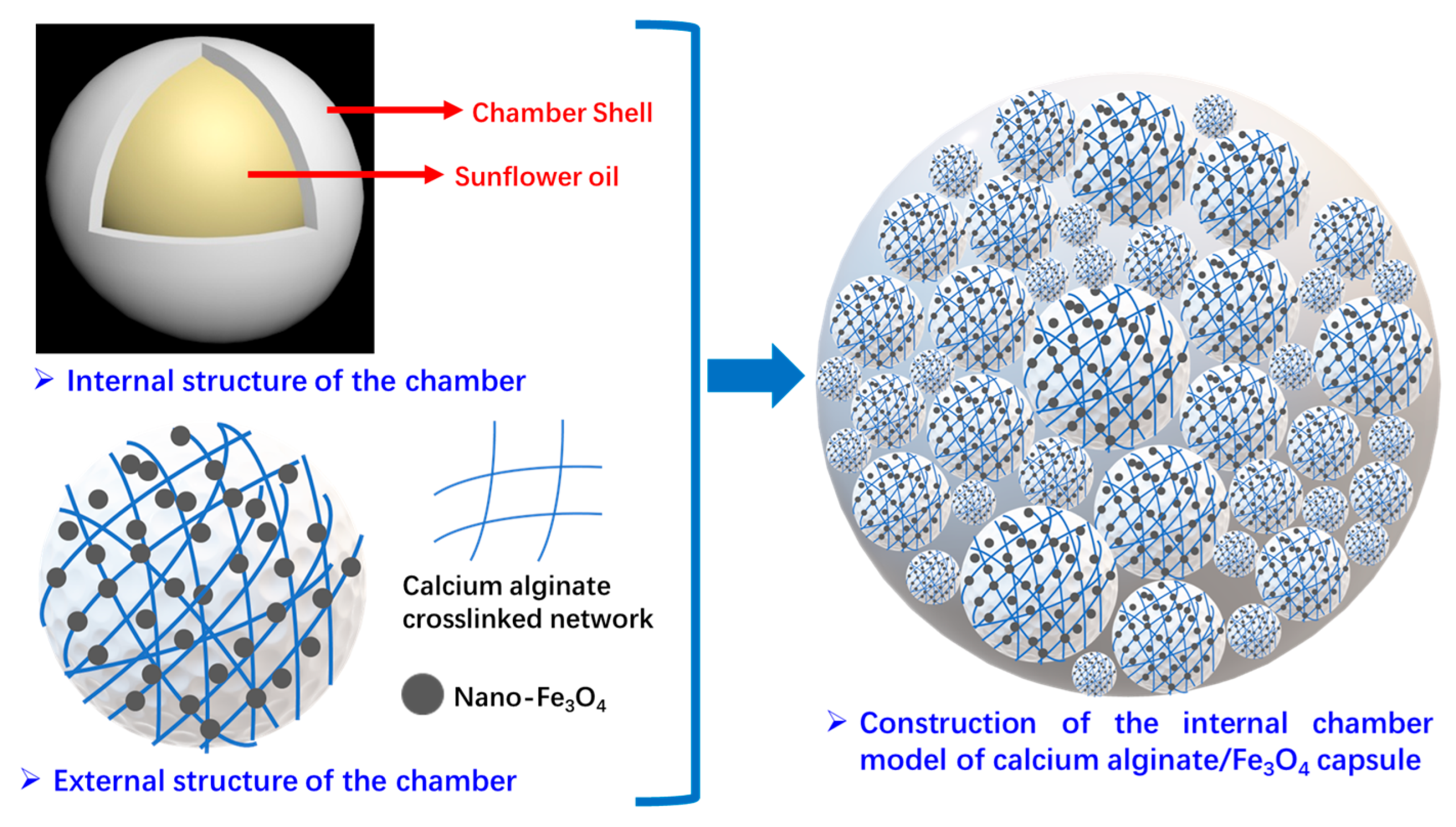

- The ideal chamber distribution in the capsule is established first. The chambers inside the capsule are uniformly shaped spheres of varying diameters, and several spherical chambers are haphazardly distributed within the capsule, with one chamber being close to another. The individual chambers exhibit a “core–shell structure”, where sunflower oil is enclosed inside spherical chambers of various forms. The chamber walls are composed of calcium alginate and nano-Fe3O4.

- Under cyclic load, the capsule forms microcracks on its outer surface through continuous contraction–expansion, and the internal chambers squeeze each other, resulting in the formation of pores on the chamber wall, and the healing agent inside the chamber discharges through the voids on the chamber wall and the cracks on the outer surface of the capsule. The capsule gradually discharges the rejuvenator under cyclic load. After 16,000, 32,000, 48,000, 64,000, 96,000, and 128,000 cycles of cyclic loading (0.7 MPa), the rejuvenator discharge rates of capsules are 23.9%, 36.4%, 44.8%, 49.5%, 56.7%, and 60.3%, respectively. The long-lasting and slow-discharge properties of the capsules are conducive to the realization of long-lasting repair of asphalt concrete.

- Under the action of microwave irradiation, the magnetic nano-Fe3O4 particles embedded in the outer surface of the capsule rotate, vibrate, and exhibit other irregular movements, forming voids of varying sizes on the surface. Meanwhile, the nano-Fe3O4 particles on the wall of the internal chamber are subjected to irregular orientation movements in an alternating magnetic field, and at the same time, heat is generated, resulting in the emergence of micropores in the wall of the chamber, which prompts the restorative agent within the chamber to flow through the micropores and diffuse to the asphalt through the void on the outer surface. After 30, 60 s, and 90 s of microwave exposure, the rejuvenator discharge rates of capsule restorative are 31.7%, 46.2%, and 57.5%, respectively.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, M.; Yao, X.; Du, X. Low temperature cracking behavior of asphalt binders and mixtures: A review. J. Road Eng. 2023, 3, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Wang, F.; Liu, K.; Liu, Q.; Liu, P.; Oeser, M. Inductive asphalt pavement layers for improving electromagnetic heating performance. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 2159401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabette, M.; Pais, J.; Micaelo, R. Extrinsic healing of asphalt mixtures: A review. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2023, 25, 1145–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Ahmad, W.; Amin, M.N.; Khan, S.A.; Deifalla, A.F.; Younes, M.Y.M. Research evolution on self-healing asphalt: A scientometric review for knowledge mapping. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2023, 62, 20220331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Wu, S.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Gong, X.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, S.; Jiang, J.; Fan, L.; Tu, L. Extrinsic self-healing asphalt materials: A mini review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 138910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yuan, L.; Cong, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, J. Self-healing microcapsule properties improvement technology: Key challenges and solutions for application in asphalt materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 439, 137298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, S.; Valizadeh, M.; Khavandi, A. Evaluation of the sensitivity of the rheology characteristics of bitumen and slurry seal modified with cellulose nanofiber solution. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 422, 135318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Yun, S.; Liu, H. The properties of a new fog seal material made from emulsified asphalt modified by composite agents. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2024, 25, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zheng, M.; Ding, X.; Qiao, R.; Zhang, W. Laboratory proportion design and performance evaluation of Fiber-Reinforced rubber asphalt chip seal based on multiple properties enhancement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 403, 133204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.M.; Ma, H.-J.; Park, D.-W. Evaluation on performance of rubber tire powder and waste glass modified binder as crack filling materials using 3D printing technology. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 135225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaza Apaza, F.R.; Rodrigues Guimaraes, A.C.; Vivoni, A.M.; Schroder, R. Evaluation of the performance of iron ore waste as potential recycled aggregate for micro-surfacing type cold asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 266, 121020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Feng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yu, H.; Korolev, E.; Obukhova, S.; Zou, G.; Zhang, Y. Investigation of cracking resistance of cold asphalt mixture designed for ultra-thin asphalt layer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 414, 134941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian, K.M.; Carpio, M.; González, Á. Assessment of the sustainability of asphalt pavement maintenance using the microwave heating self-healing technique. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-h. Strategy for reducing carbon dioxide emissions from maintenance and rehabilitation of highway pavement. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Dong, W.; Fu, Z.; Wang, R.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J. Life cycle assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from asphalt pavement maintenance: A case study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokede, O.O.; Whittaker, A.; Mankaa, R.; Traverso, M. Life cycle assessment of asphalt variants in infrastructures: The case of lignin in Australian road pavements. Structures 2020, 25, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Á. Self-healing of open cracks in asphalt mastic. Fuel 2012, 93, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agzenai, Y.; Pozuelo, J.; Sanz, J.; Perez, I.; Baselga, J. Advanced self-healing asphalt composites in the pavement performance field: Mechanisms at the nano level and new repairing methodologies. Recent Pat. Nanotechnol. 2015, 9, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayar, P.; Moreno-Navarro, F.; Rubio-Gámez, M.C. The healing capability of asphalt pavements: A state of the art review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaković, A.; Schlangen, E. Self-healing technology for asphalt pavements. In Self-Healing Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 285–306. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.; Sun, G.; Zhu, X.; Guarin, A.; Li, B.; Dai, Z.; Ling, J. A comprehensive review on self-healing of asphalt materials: Mechanism, model, characterization and enhancement. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 256, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; García, A.; Su, J.; Liu, Q.; Tabaković, A.; Schlangen, E. Self-Healing Asphalt Review: From Idea to Practice. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 5, 1800536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Torre, I.; Norambuena-Contreras, J. Recent advances on self-healing of bituminous materials by the action of encapsulated rejuvenators. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 258, 119568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hao, P.; Zhang, M. Fabrication, characterization and assessment of the capsules containing rejuvenator for improving the self-healing performance of asphalt materials: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, D.; Sun, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Guan, Y. Preparation, characterization and repeated repair ability evaluation of asphalt-based crack sealant containing microencapsulated epoxy resin and curing agent. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 256, 119433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Tan, X.; Zhu, C.; Guan, Y. Effects of microcapsules on self-healing performance of asphalt materials under different loading modes. J. Transp. Eng. Part B Pavements 2021, 147, 04021010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ji, X.-p.; Fang, X.-z.; Hu, Y.-l.; Hua, W.-l.; Zhang, Z.-m.; Shao, D.-y. Self-healing performance and prediction model of microcapsule asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 330, 127085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Wang, S.; Yao, B.; Si, W.; Wang, C.; Wu, T.; Zhang, X. Preparation and properties of nano-SiO2 modified microcapsules for asphalt pavement. Mater. Des. 2023, 229, 111871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hao, P.; Zhang, M.; Sun, B.; Liu, J.; Li, N. Synthesis and characterization of calcium alginate capsules encapsulating soybean oil for in situ rejuvenation of aged asphalt. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04021310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norambuena-Contreras, J.; Concha, J.; Arteaga-Pérez, L.; Gonzalez-Torre, I. Gonzalez-Torre, Synthesis and characterisation of alginate-based capsules containing waste cooking oil for asphalt self-healing. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T.; Freire, A.C.; Sá-da-Costa, M.; Canejo, J.; Cordeiro, V.; Micaelo, R. Investigating asphalt self-healing with colorless binder and pigmented rejuvenator. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Su, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, Z.; Sun, G. Waste cooking oil based capsules for sustainable self-healing asphalt pavement: Encapsulation, characterization and fatigue-healing performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 425, 136032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Wu, S.; Liu, Q.; Zou, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, S. Recent advances in calcium alginate hydrogels encapsulating rejuvenator for asphalt self-healing. J. Road Eng. 2022, 2, 181–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hoff, I.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, C.; Wang, F. A methodological review on development of crack healing technologies of asphalt pavement. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Li, B.; Sun, D.; Hu, M.; Ma, J.; Sun, G. Advances in controlled release of microcapsules and promising applications in self-healing of asphalt materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Liu, Q.; Wu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, S.; Zou, Y.; Rao, W.; Yu, X. A novel microwave induced oil release pattern of calcium alginate/ nano-Fe3O4 composite capsules for asphalt self-healing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Liu, Q.; Wu, S.; Zou, Y.; Zhao, F.; Wang, H.; Niu, Y.; Ye, Q. Dual responsive self-healing system based on calcium alginate/Fe3O4 capsules for asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 360, 129585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Wu, S.; Liu, Q.; Xu, H.; Wang, H.; Peng, Z.; Rao, W.; Zou, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, S. Self-healing properties of asphalt concrete containing responsive calcium alginate/nano-Fe3O4 composite capsules via microwave irradiation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 310, 125258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Wu, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Q.; Xu, S.; Wang, J. A novel combined healing system for sustainable asphalt concrete based on loading-microwave dual responsive capsules. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, M.; Nizamuddin, S.; Madapusi, S.; Giustozzi, F. Sustainable asphalt rejuvenation using waste cooking oil: A comprehensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Yao, H.; Suo, Z.; You, Z.; Li, H.; Xu, S.; Sun, L. Effectiveness of vegetable oils as rejuvenators for aged asphalt binders. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2017, 29, D4016003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Liu, Q.; Wan, P.; Song, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J. Effect of ageing on self-healing properties of asphalt concrete containing calcium alginate/attapulgite composite capsules. Materials 2022, 15, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concha, J.L.; Delgadillo, R.; Arteaga-Perez, L.E.; Segura, C.; Norambuena-Contreras, J. Optimised sunflower oil content for encapsulation by vibrating technology as a rejuvenating solution for asphalt self-healing. Polymers 2023, 15, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norambuena-Contreras, J.; Yalcin, E.; Garcia, A.; Al-Mansoori, T.; Yilmaz, M.; Hudson-Griffiths, R. Effect of mixing and ageing on the mechanical and self-healing properties of asphalt mixtures containing polymeric capsules. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 175, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norambuena-Contreras, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wu, S.; Yalcin, E.; Garcia, A. Influence of encapsulated sunflower oil on the mechanical and self-healing properties of dense-graded asphalt mixtures. Mater. Struct. 2019, 52, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Q.; Li, H.; Norambuena-Contreras, J.; Wu, S.; Bao, S.; Shu, B. Synthesis and characterization of multi-cavity Ca-alginate capsules used for self-healing in asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 211, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, W.; Liu, Q.; Yu, X.; Wan, P.; Wang, H.; Song, J.; Ye, Q. Efficient preparation and characterization of calcium alginate-attapulgite composite capsules for asphalt self-healing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 299, 123931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.; Schlangen, E.; van de Ven, M.; Sierra-Beltran, G. Preparation of capsules containing rejuvenators for their use in asphalt concrete. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 184, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Tabaković, A.; Liu, X.; Palin, D.; Schlangen, E. Optimization of the calcium alginate capsules for self-healing asphalt. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.-H.; Tsai, C.-H.; Liao, C.-F.; Liu, D.-M.; Chen, S.-Y. Controlled rupture of magnetic polyelectrolyte microcapsules for drug delivery. Langmuir 2008, 24, 11811–11818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhao, B.; Song, K.; Yang, G.; Tung, C.-H. Bio-inspired controlled release through compression-relaxation cycles of microcapsules. NPG Asia Mater. 2015, 7, e148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Raw Material | Purity | Manufacture |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium alginate | CP | Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Beijing, China) |

| Anhydrous CaCl2 | CP | Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Beijing, China) |

| Nano-Fe3O4 (50 nm) | 99.9% | Chaowei nanomaterials Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). |

| Sunflower oil | Food grade | Arowana Group Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) |

| Tween 80 | AR | Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Beijing, China) |

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Density (15 °C) | 0.935 g/cm3 |

| Viscosity (60 °C) | 0.285 Pa·s |

| Flash point | 230 °C |

| Experiment | Instrument | Manufacturers | Work Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEM |  | Gemini 300 Zeiss Oberkochen, Germany | Coat substance: Platinum powder Coat time: 30 s |

| UCT |  | Instron 5967 Instron Norwood, MA, USA | Load speed: 0.05 mm/min |

| TGA |  | STA449F3 Netzsch Selb, Germany | Temperature range: 40~990 °C Temperature rise rate: 10 °C/min |

| Sieve size/mm | 16 | 13.2 | 9.5 | 4.75 | 2.36 | 1.18 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.15 | 0.075 |

| Passing rate/% | 100 | 96.5 | 78.2 | 51.9 | 33.3 | 21.0 | 14.6 | 11.2 | 9.0 | 6.8 |

| Specific limit/% | 100 | 90–100 | 68–85 | 38–68 | 24–50 | 15–38 | 10–28 | 7–20 | 5–15 | 4–8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wan, P.; Wang, J.; Ma, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhong, P.; Zou, X.; Shen, Y.; Lin, N.; Chen, H.; Wu, S.; et al. Dual-Triggered Release Mechanisms in Calcium Alginate/Fe3O4 Capsules for Asphalt Self-Healing: Cyclic Load-Induced Sustained Release and Microwave-Activated On-Demand Delivery. Polymers 2025, 17, 3187. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233187

Wan P, Wang J, Ma Z, Lin Z, Zhong P, Zou X, Shen Y, Lin N, Chen H, Wu S, et al. Dual-Triggered Release Mechanisms in Calcium Alginate/Fe3O4 Capsules for Asphalt Self-Healing: Cyclic Load-Induced Sustained Release and Microwave-Activated On-Demand Delivery. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3187. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233187

Chicago/Turabian StyleWan, Pei, Jiazhu Wang, Zirong Ma, Zhiming Lin, Peixin Zhong, Xiaobin Zou, Yilun Shen, Niecheng Lin, Hang Chen, Shaopeng Wu, and et al. 2025. "Dual-Triggered Release Mechanisms in Calcium Alginate/Fe3O4 Capsules for Asphalt Self-Healing: Cyclic Load-Induced Sustained Release and Microwave-Activated On-Demand Delivery" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3187. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233187

APA StyleWan, P., Wang, J., Ma, Z., Lin, Z., Zhong, P., Zou, X., Shen, Y., Lin, N., Chen, H., Wu, S., Liu, Q., Feng, J., Zhang, L., & Gong, X. (2025). Dual-Triggered Release Mechanisms in Calcium Alginate/Fe3O4 Capsules for Asphalt Self-Healing: Cyclic Load-Induced Sustained Release and Microwave-Activated On-Demand Delivery. Polymers, 17(23), 3187. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233187