An Experimental Study on the Mechanical Properties and ANN-Based Prediction of a Tensile Constitutive Model of ECCs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

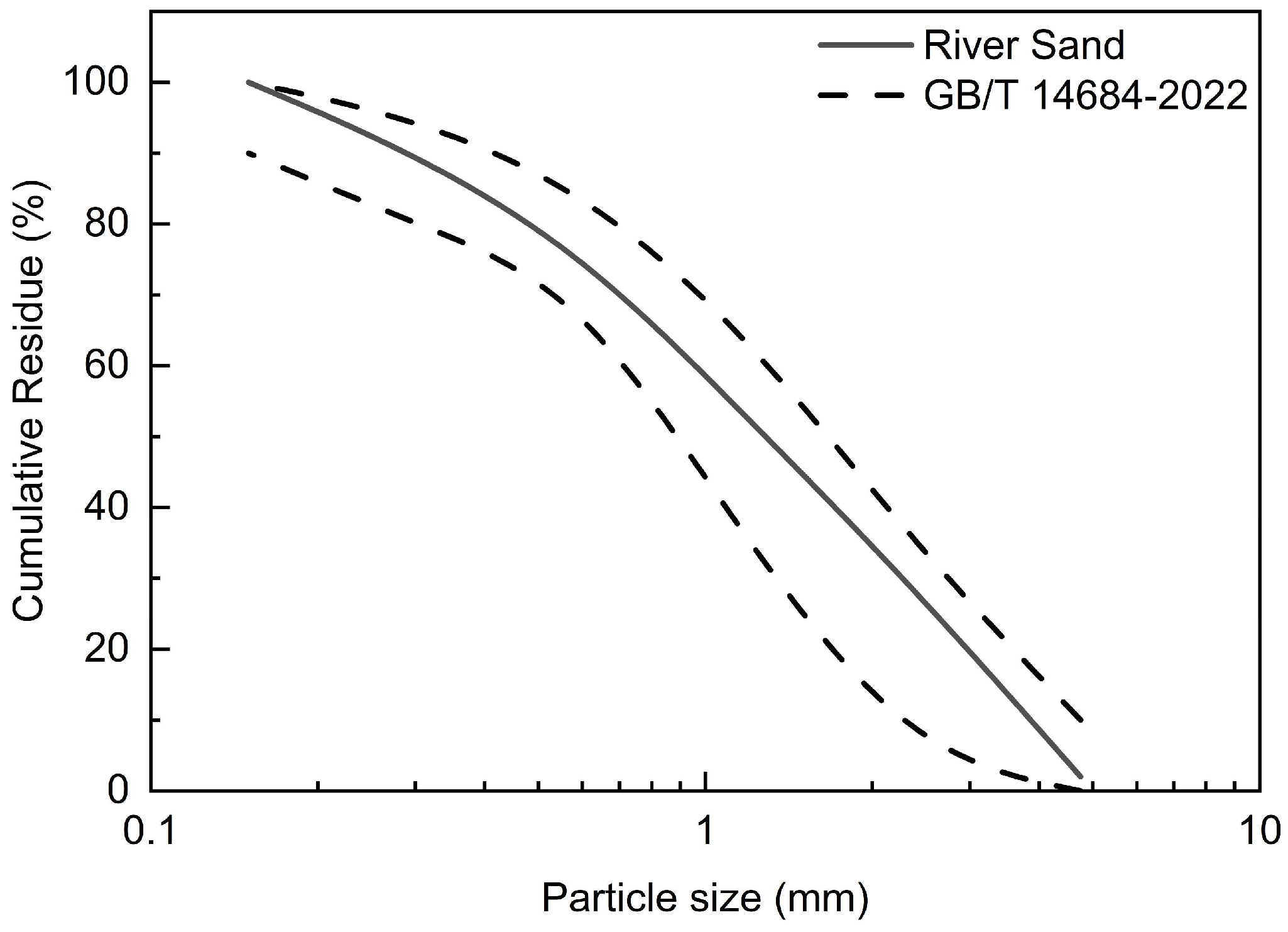

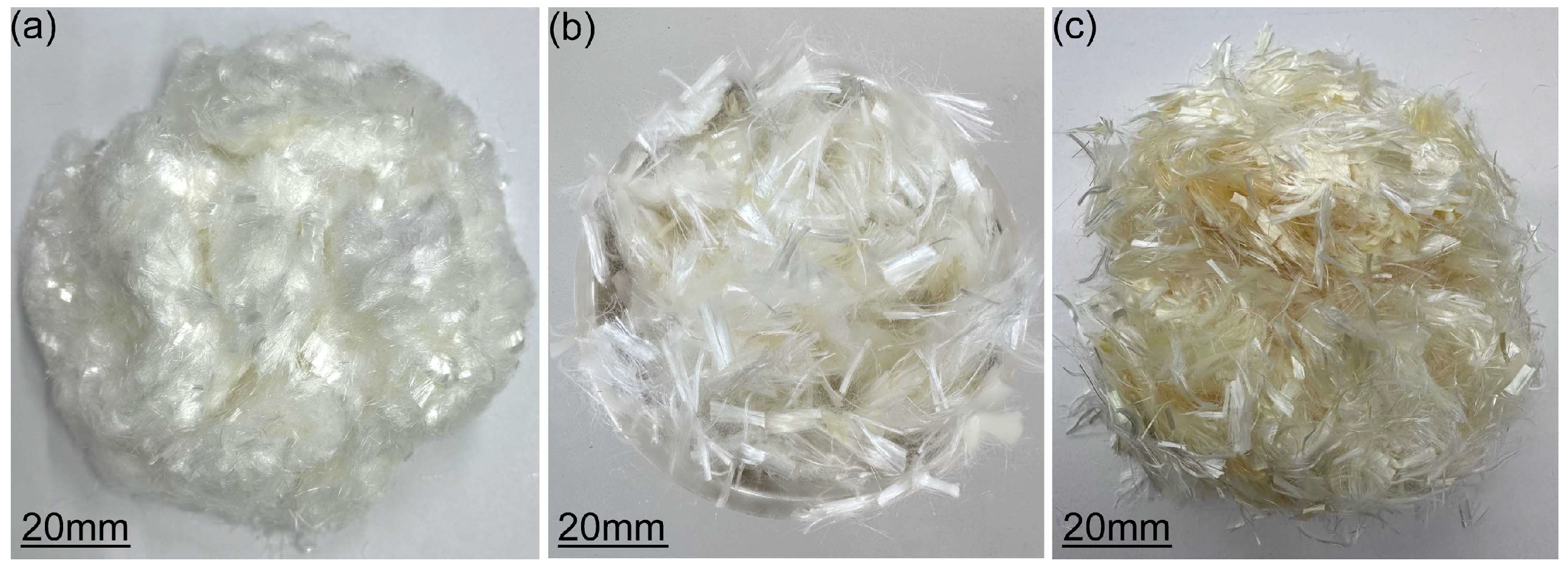

2.1. Materials

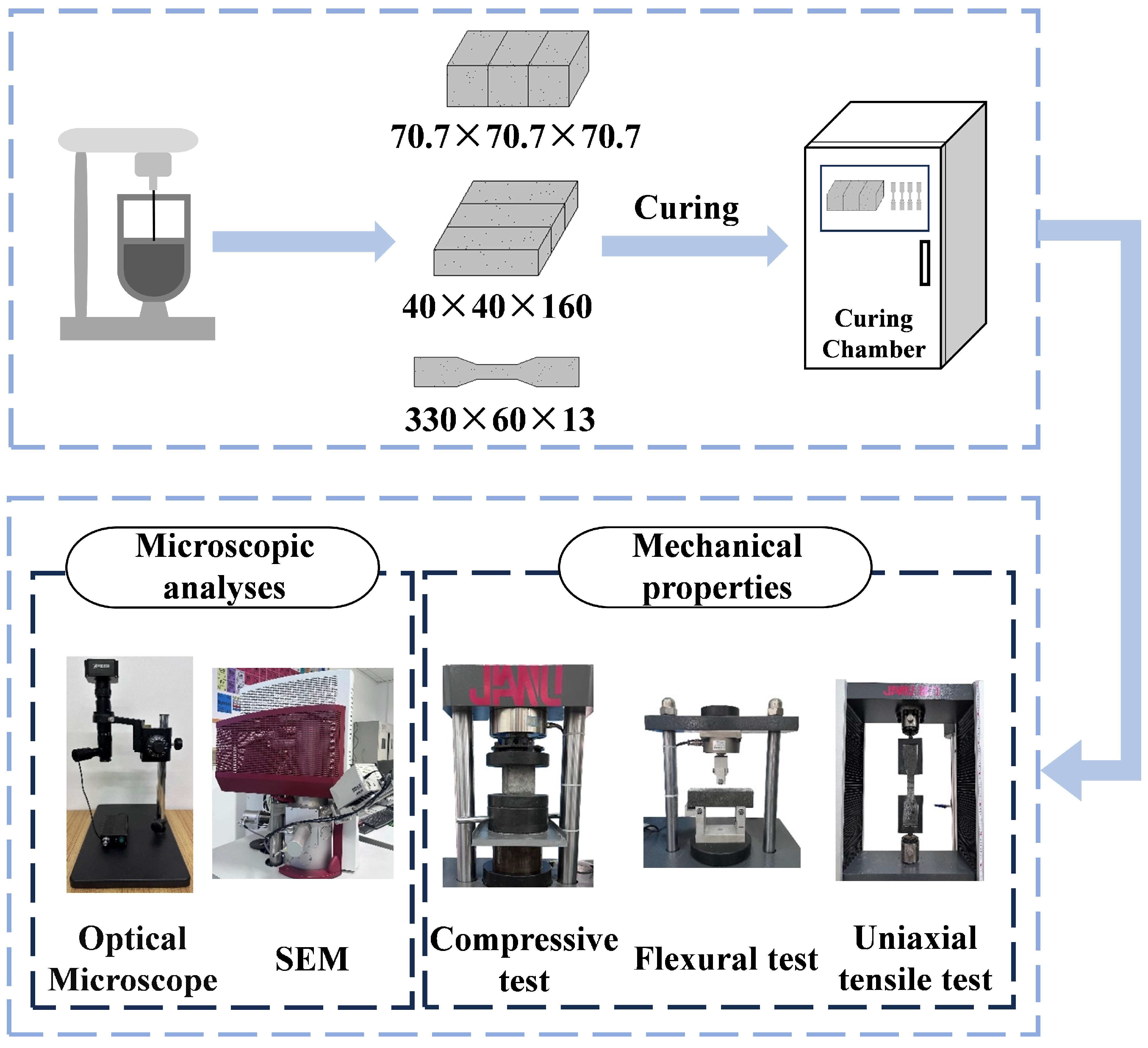

2.2. Specimen Preparation, Curing, and Testing

2.2.1. Compressive Test

2.2.2. Flexural Test

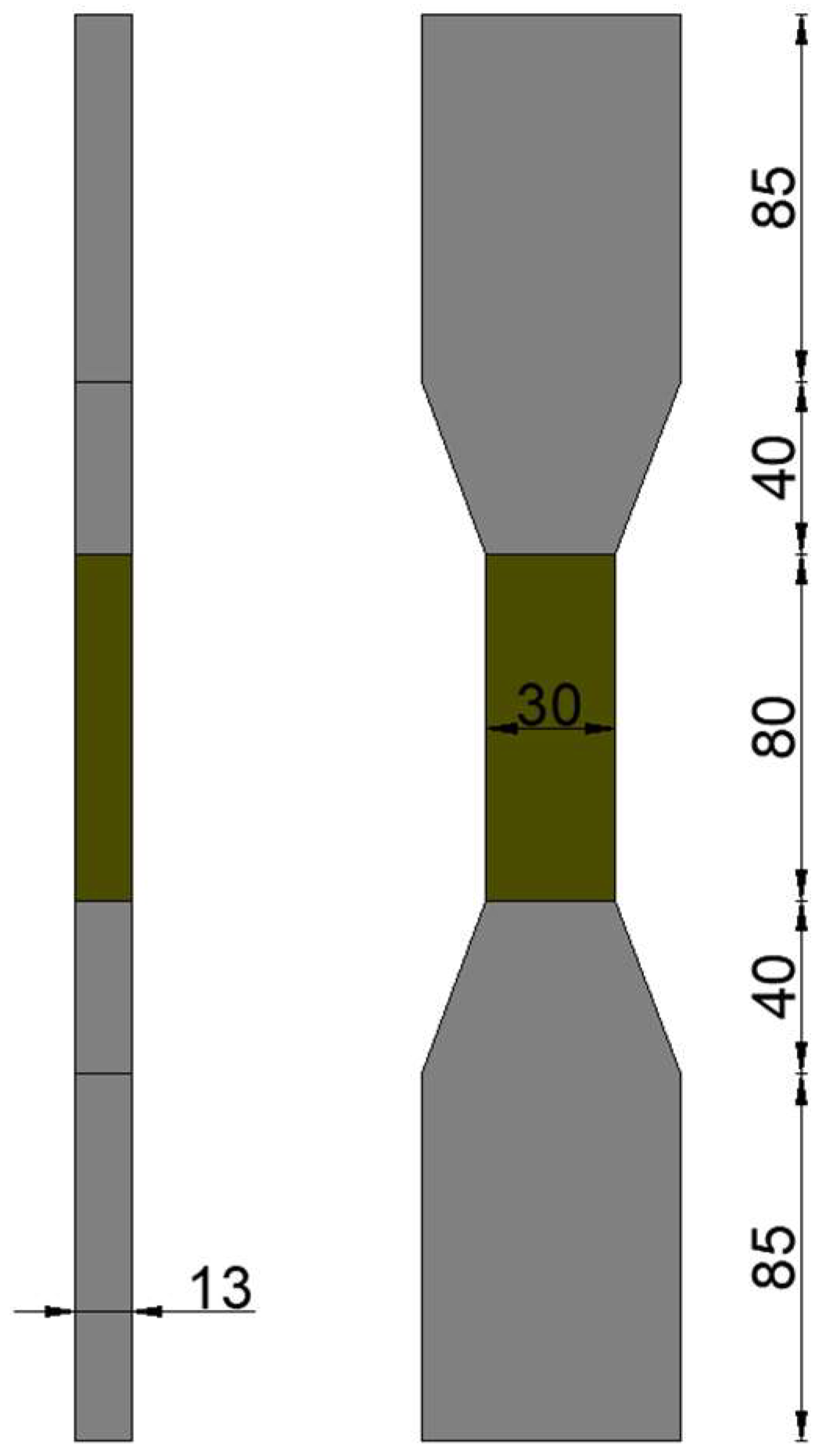

2.2.3. Uniaxial Tensile Test

3. Test Results and Analysis

3.1. Compressive Performance

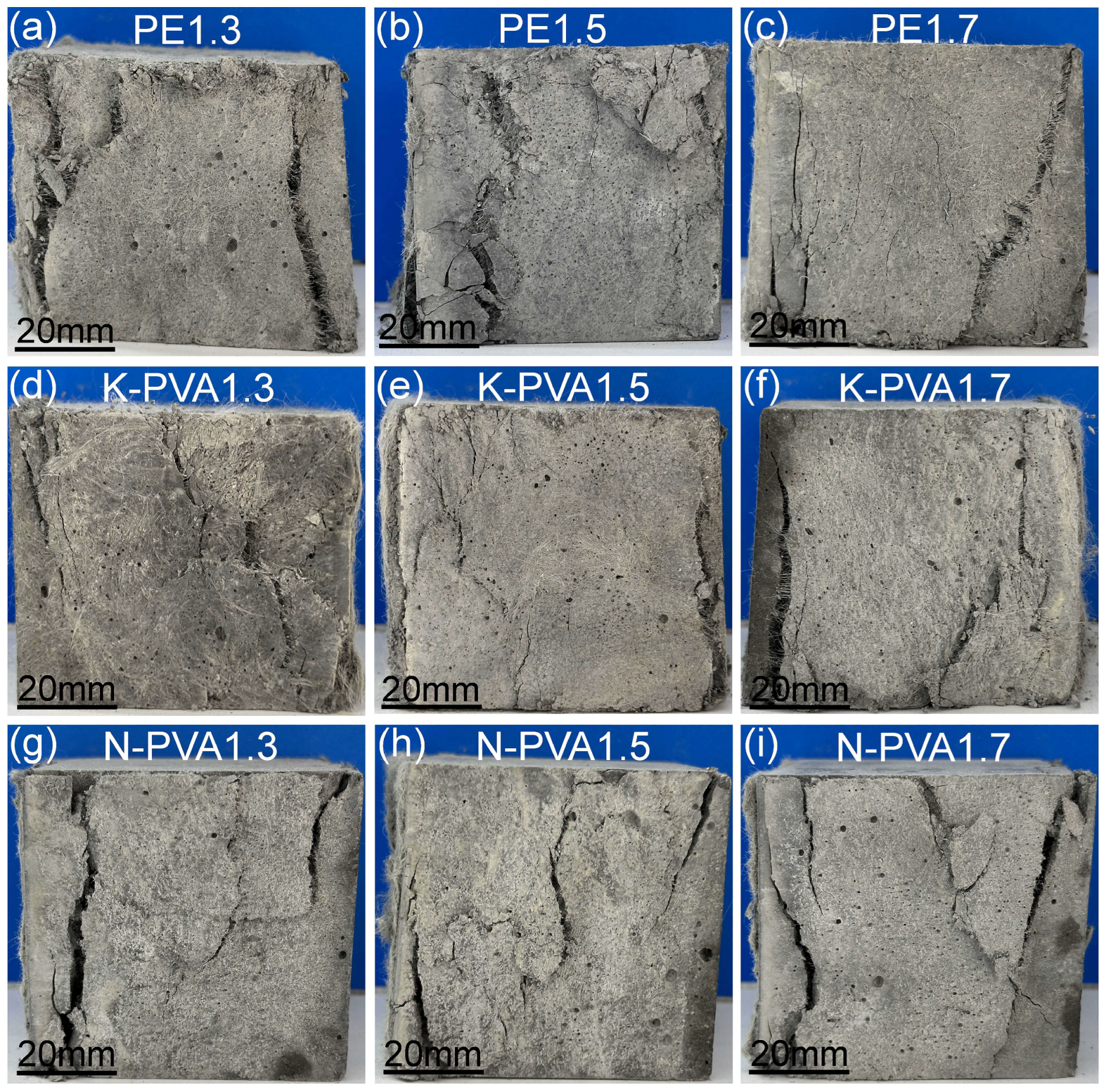

3.1.1. Compressive Destruction Form

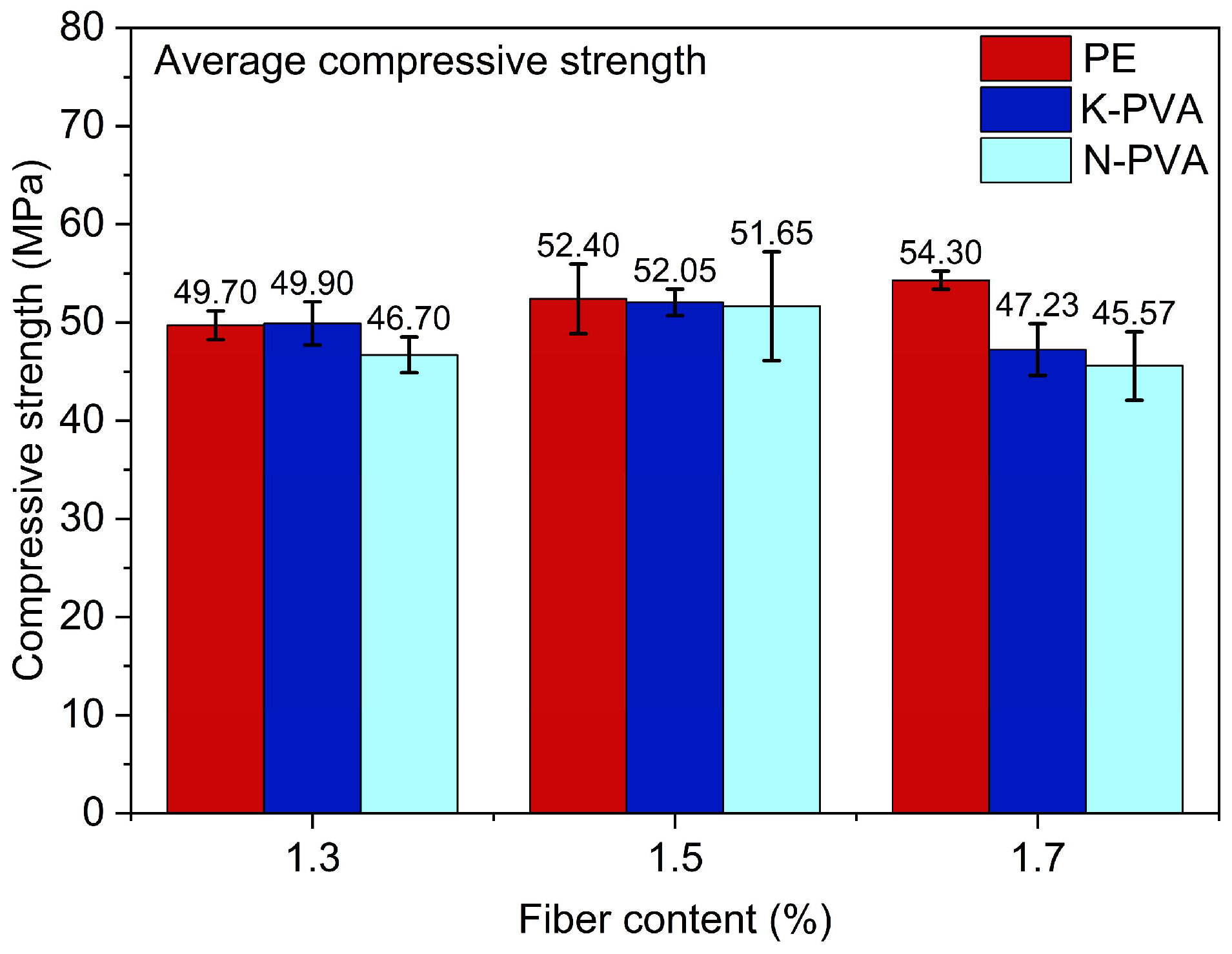

3.1.2. Compressive Strength

3.2. Flexural Performance

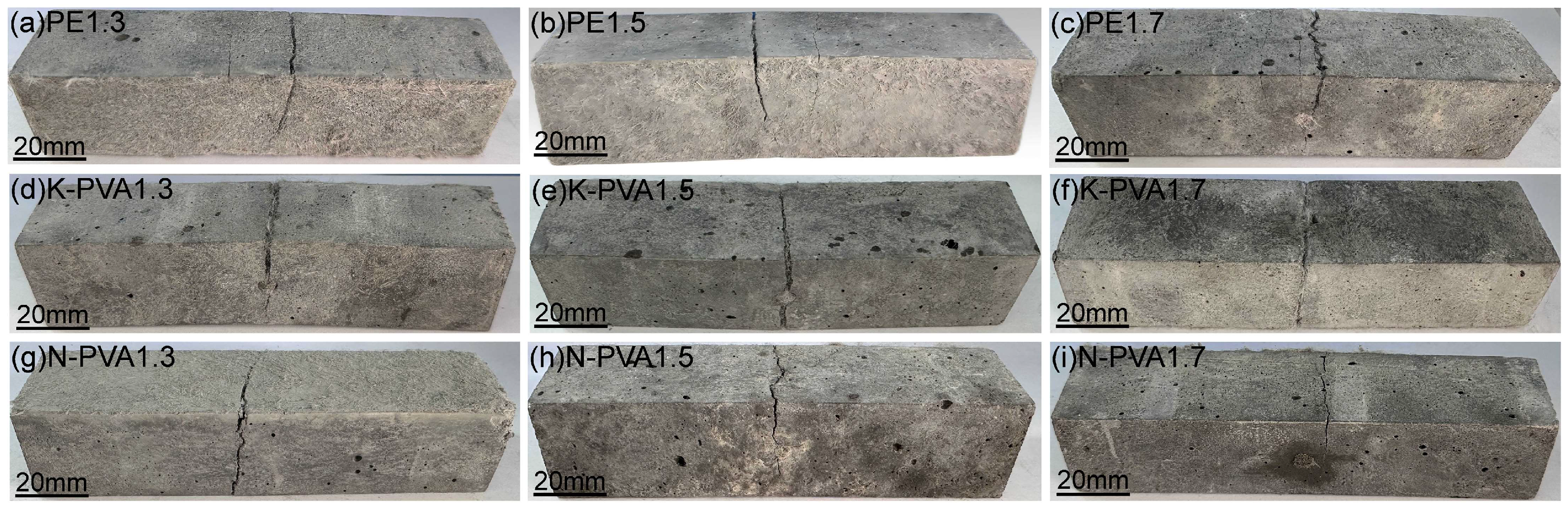

3.2.1. Flexural Destruction Form

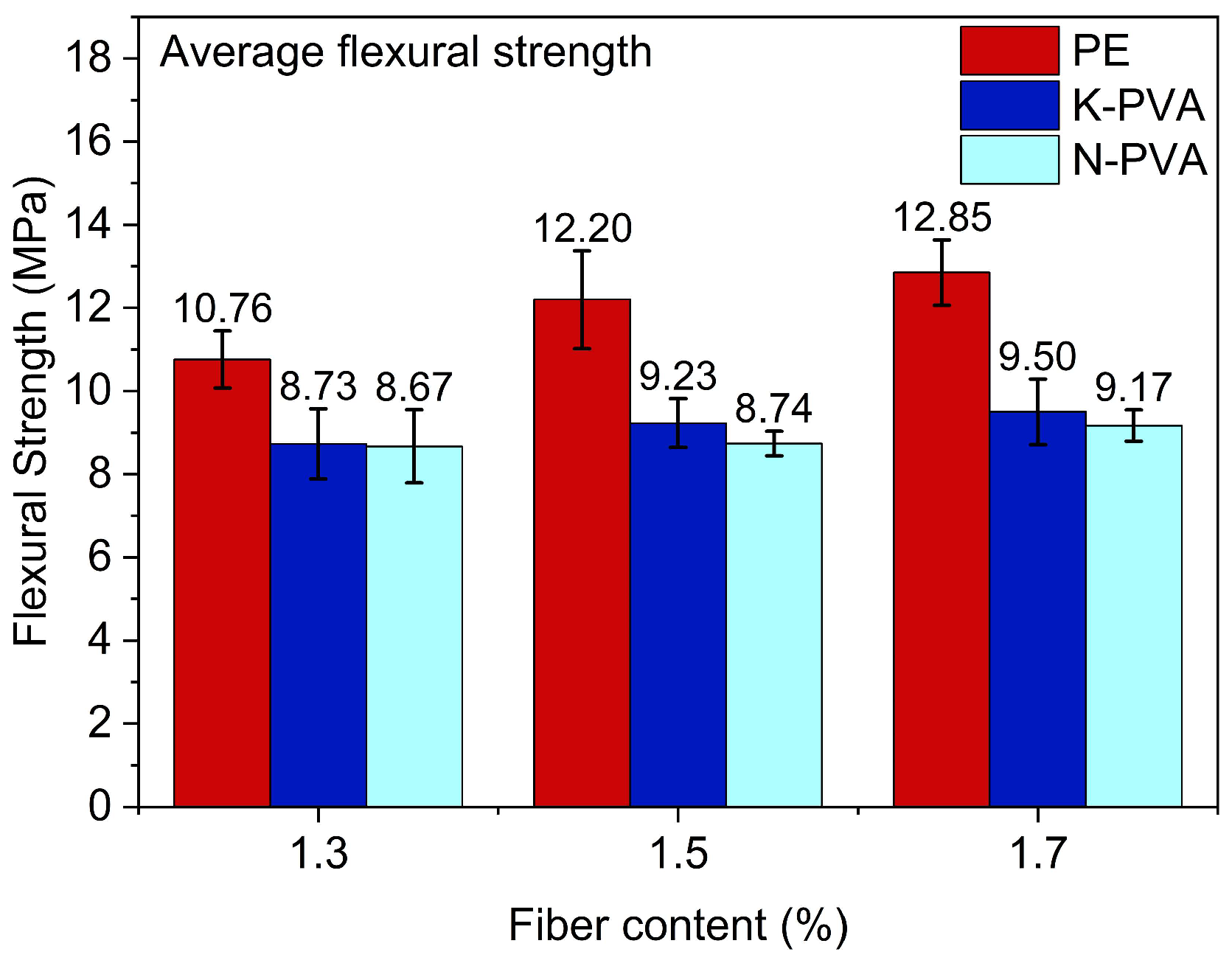

3.2.2. Flexural Strength

3.3. Uniaxial Tensile Performance

3.3.1. Tensile Destruction Form

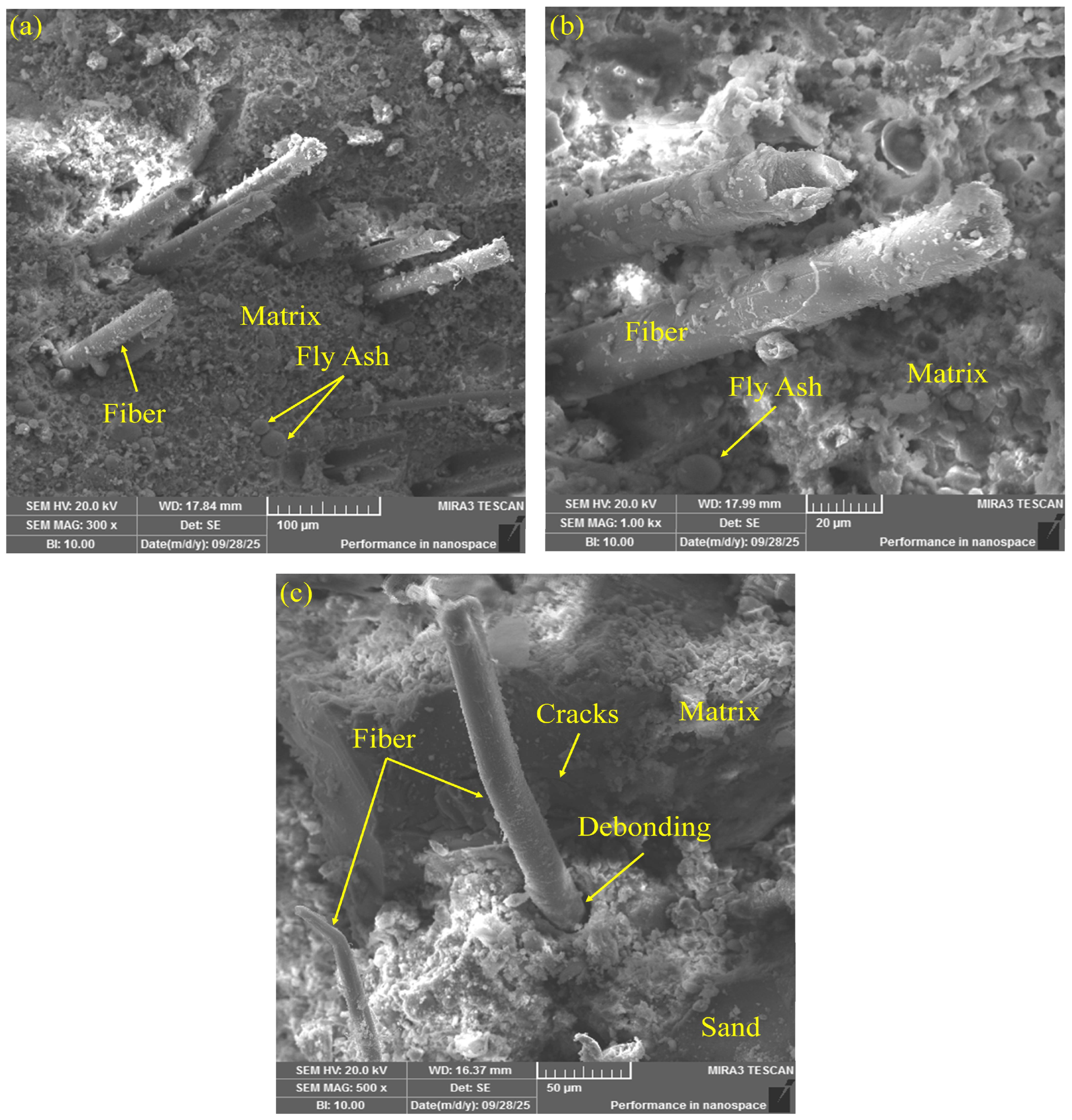

3.3.2. SEM Analysis

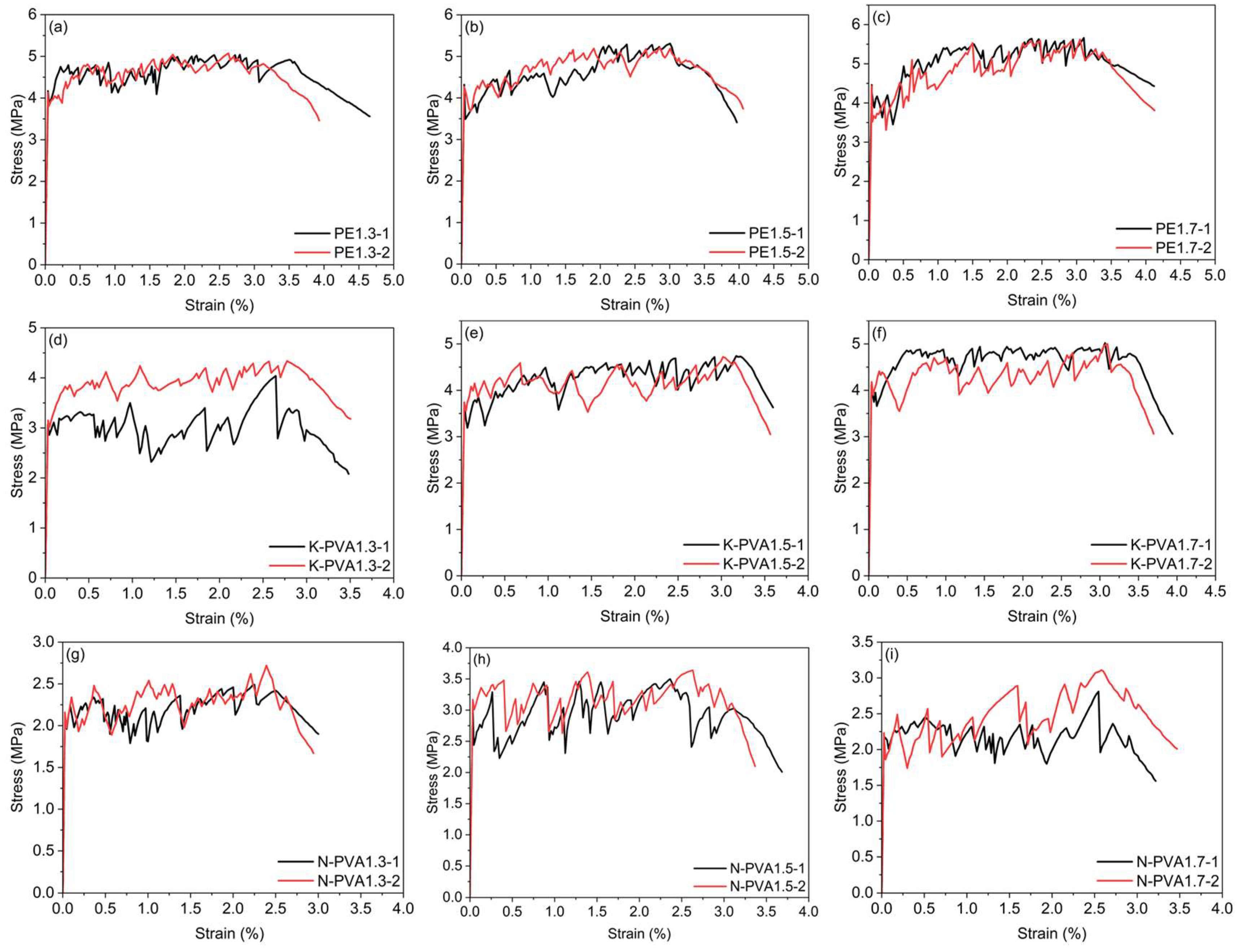

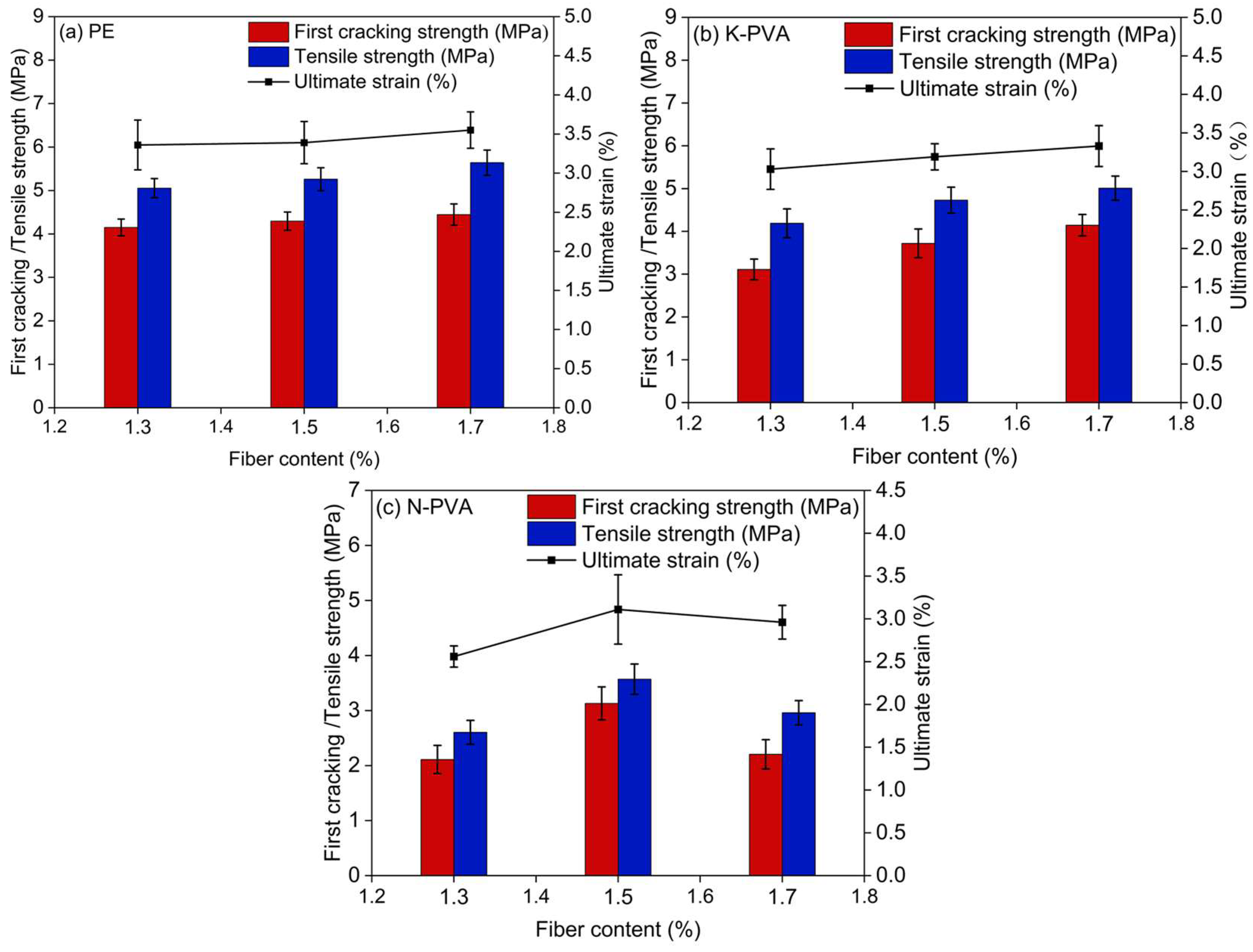

3.3.3. Tensile Stress–Strain Curve

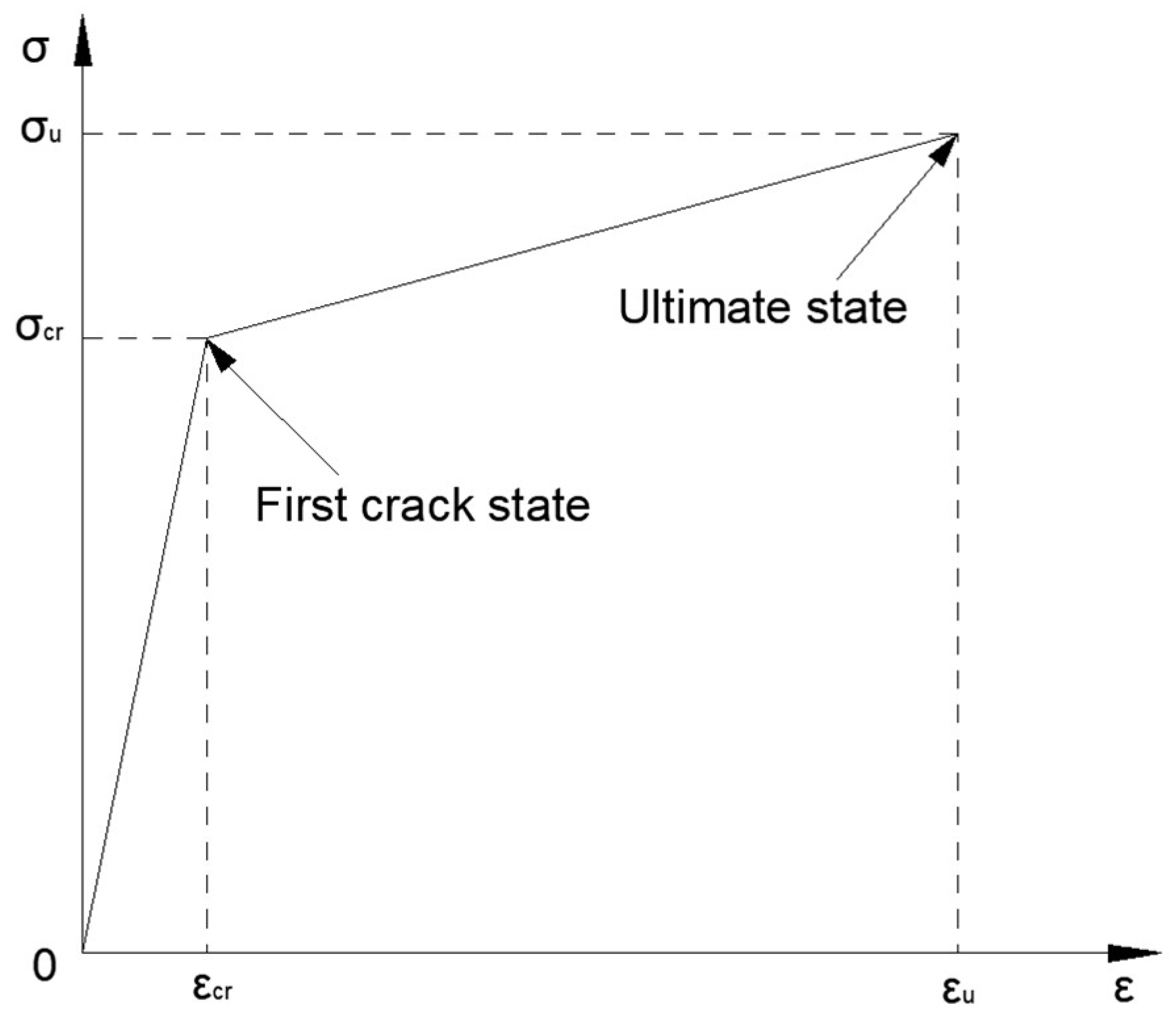

4. ANN-Based Prediction of the Tensile Constitutive Model of ECCs

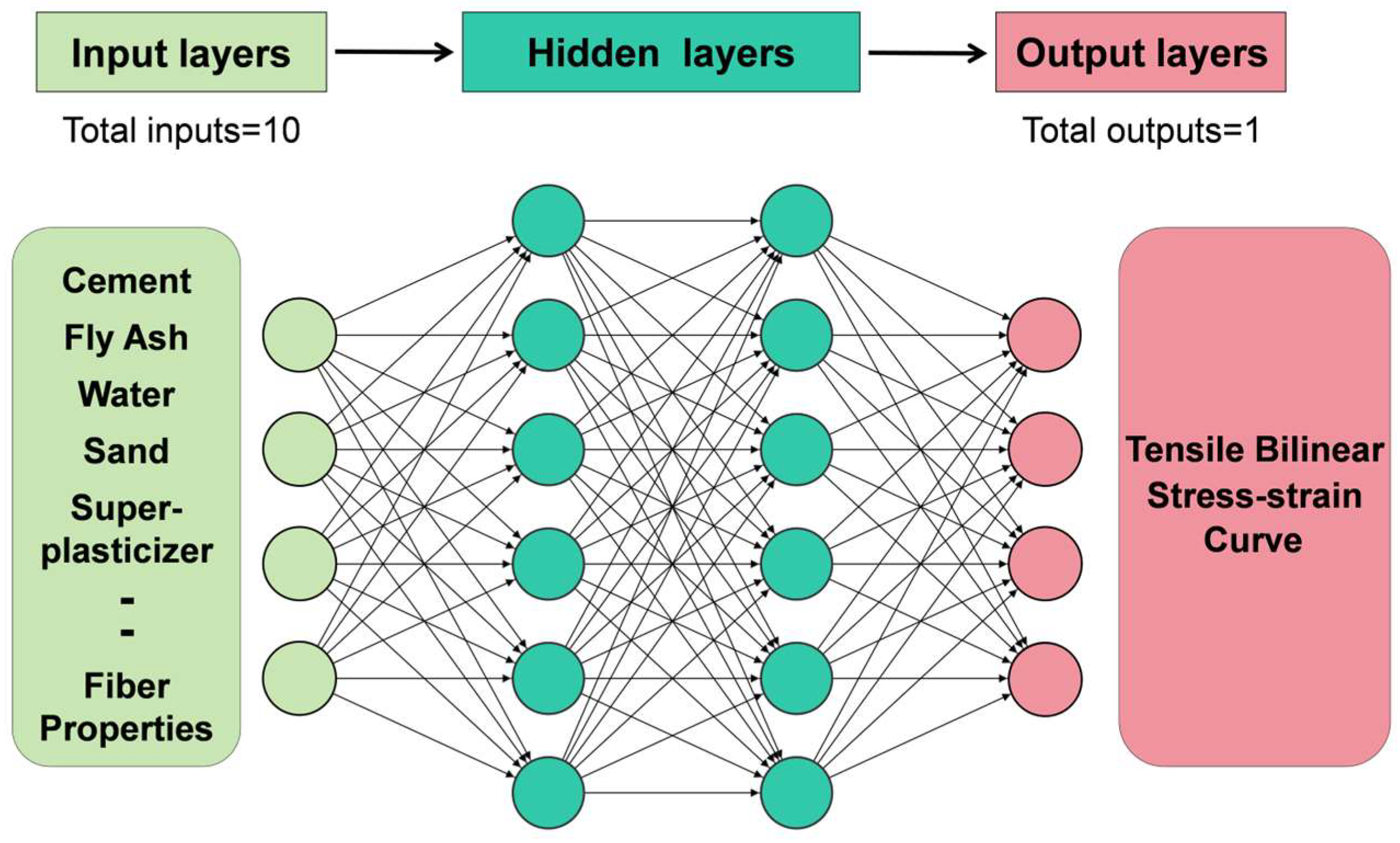

4.1. Model Establishment

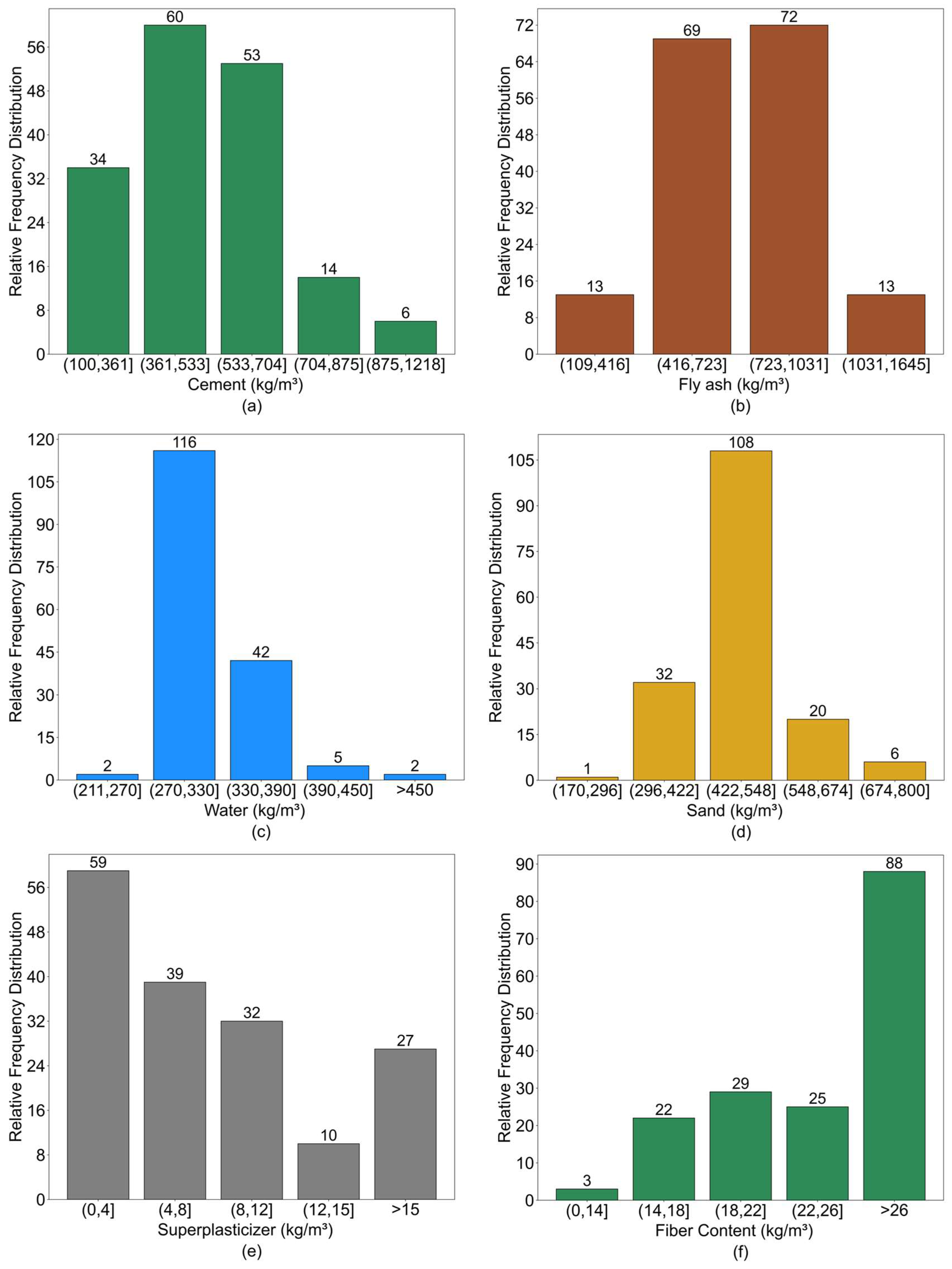

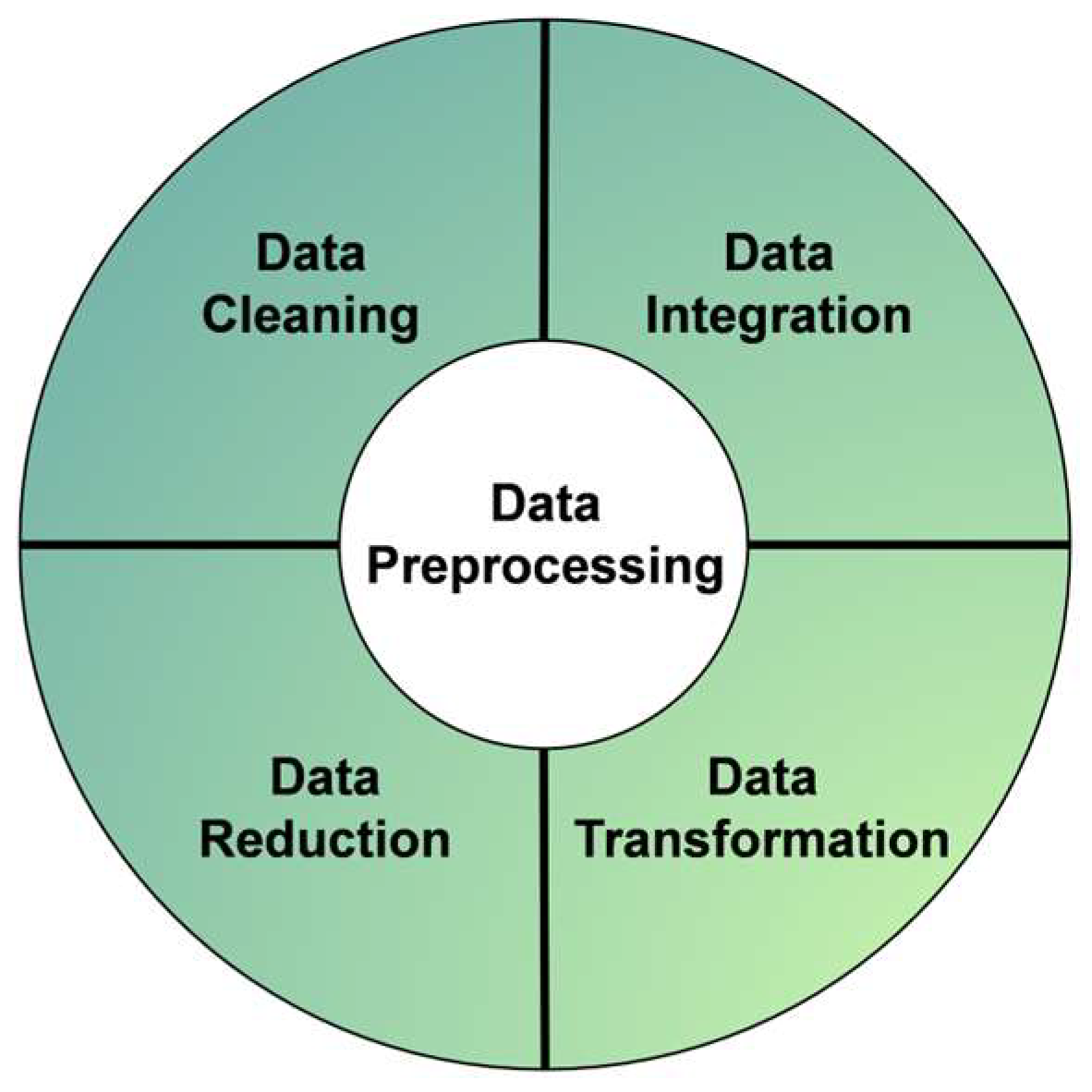

4.2. Dataset

4.2.1. Data Collection

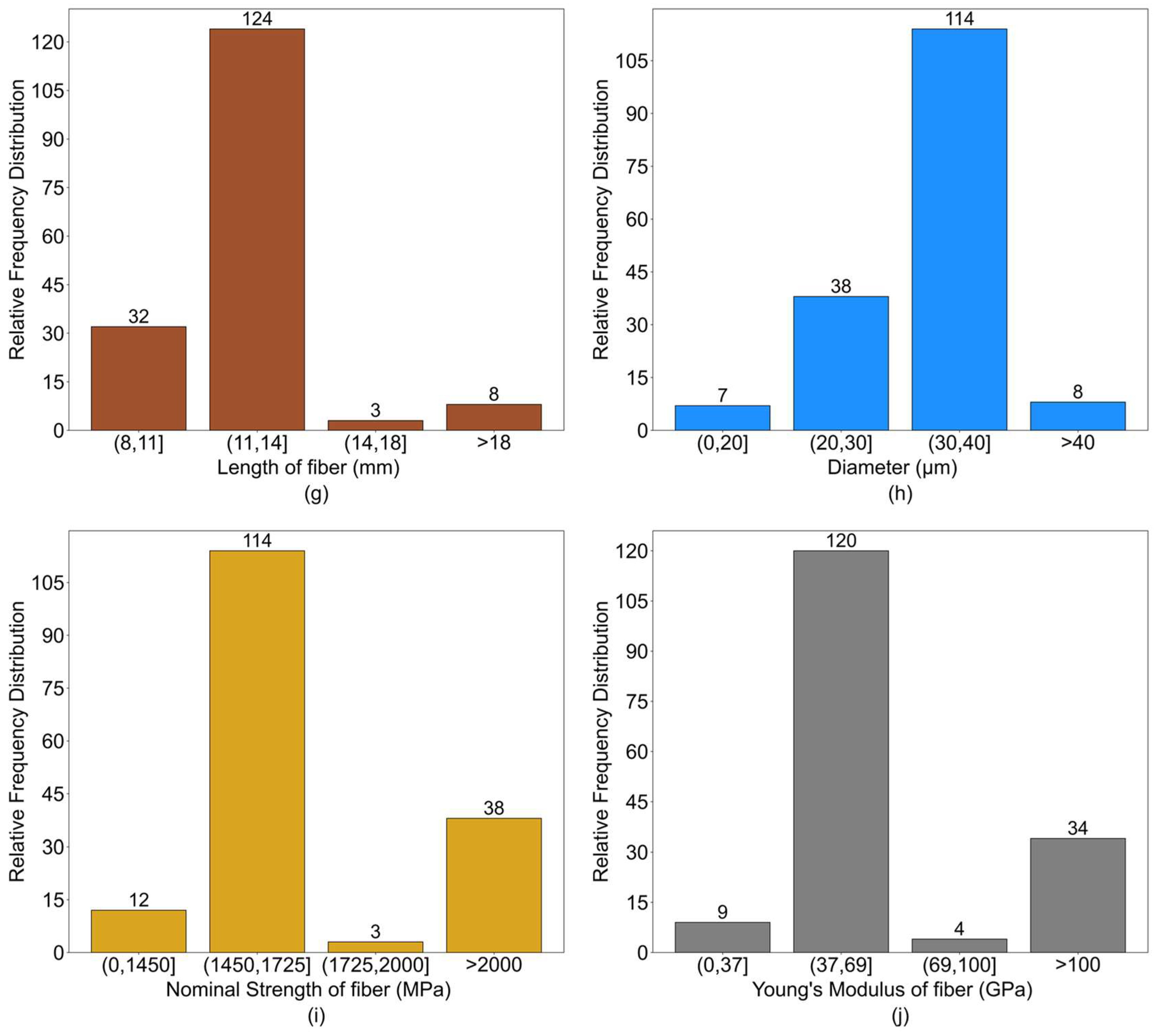

4.2.2. Data Preprocessing and Normalization

4.3. Training and Performance Evaluation of the ANN Model

4.3.1. Training Method and Hyperparameter Optimization of the ANN Model

4.3.2. Evaluation of Model Performance Indicators

4.3.3. Model Training Process

4.4. Prediction Results and Sensitivity Analysis of the ANN Model

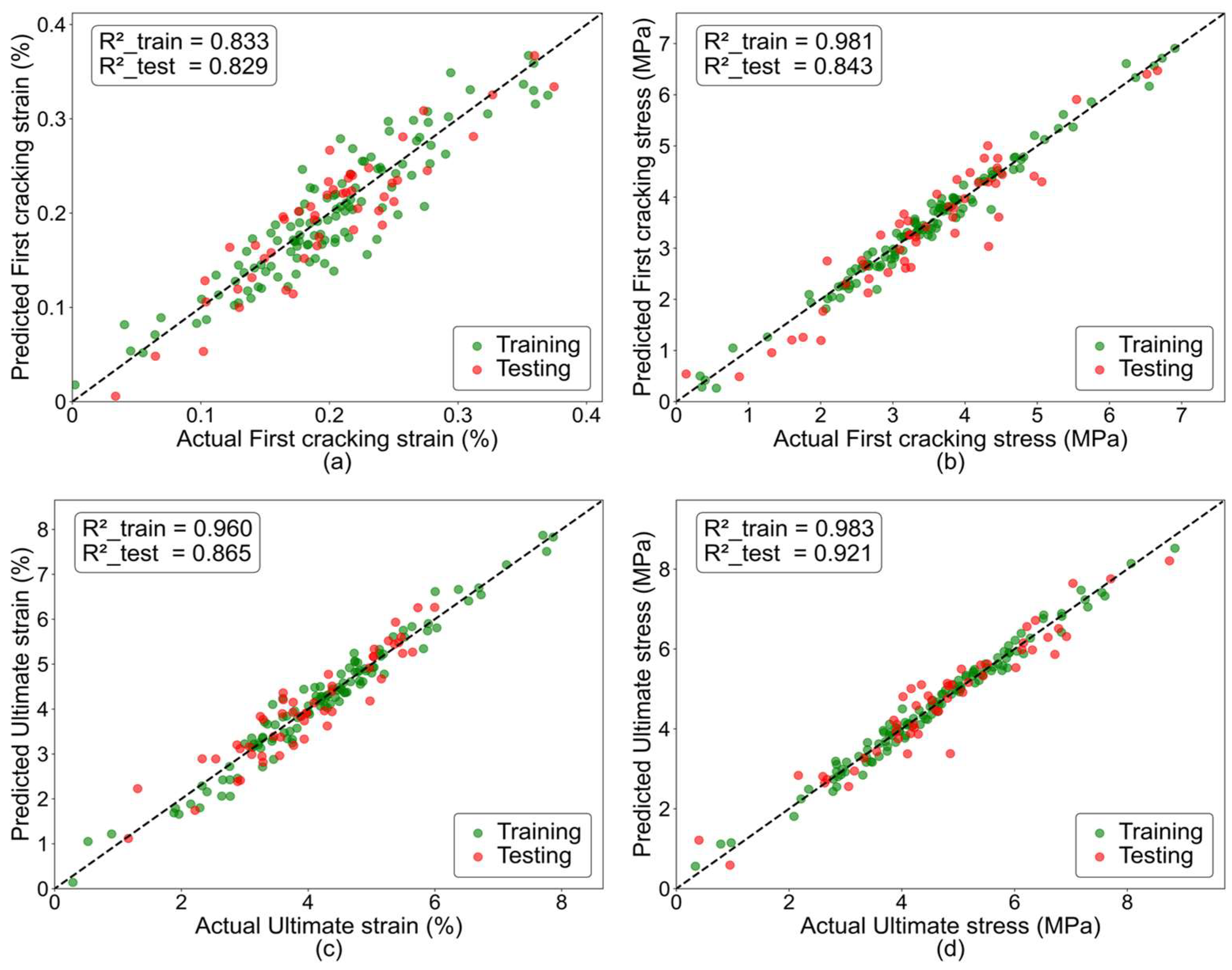

4.4.1. Prediction Results of the Model

4.4.2. Sensitivity Analysis

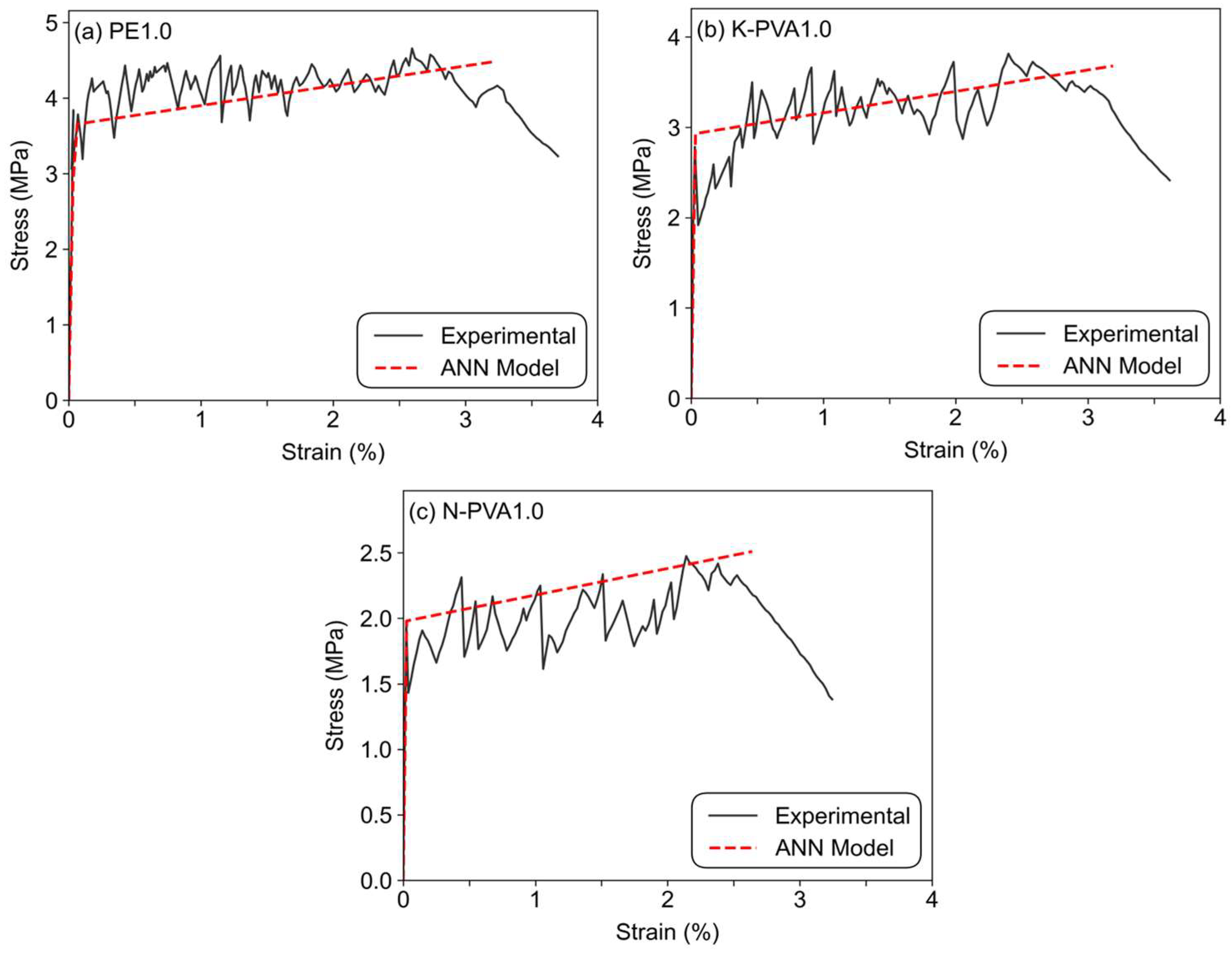

4.5. Experimental Validation and Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The compressive and flexural properties of ECCs were significantly affected by fiber type and fiber content. In specimens reinforced with PE fibers, compressive strength increased from 49.70 MPa at 1.3% fiber content to 54.30 MPa at 1.7%, while flexural strength improved from 10.76 MPa to 12.85 MPa. Both compressive and flexural strengths exhibited notable improvements, which can be attributed to the high tensile strength, high elastic modulus, and excellent dispersion of the PE fibers. For ECCs incorporating K-PVA fibers, the compressive strength at 1.5% content was 4.31% higher than that of 1.3%, but a further increase to 1.7% resulted in a reduction of approximately 5.35%. Meanwhile, the flexural strength exhibited a consistent upward trend, increasing from 5.63% to 8.78% as the fiber content rose. In contrast, ECCs with N-PVA fibers showed improved compressive strength at 1.3% and 1.5% content, but a marked decline at 1.7%, decreasing from 51.65 MPa to 45.57 MPa. The flexural strength showed only a slight increase, from 8.67 MPa to 9.17 MPa. Overall, PE fibers demonstrated the most pronounced enhancement in both compressive and flexural properties of ECCs, whereas the reinforcing effects of PVA fibers were relatively weaker, particularly at higher content, where excessive fiber addition led to performance degradation.

- (2)

- Tensile test results showed that both fiber type and content have a significant influence on the tensile performance of ECCs. As the PE fiber content increased from 1.3% to 1.7%, the first cracking strength and tensile strength increased by approximately 7.23% and 11.46%, respectively, demonstrating the most effective reinforcing performance. At a content of 1.7%, K-PVA fibers increased the first cracking strength and tensile strength by about 33.44% and 19.57%, respectively, indicating a favorable bridging effect. In contrast, at higher content, N-PVA fibers led to reductions in both first cracking strength and tensile strength due to poor fiber dispersion. This suggests that the reinforcing effect is constrained by fiber distribution and interfacial bonding capacity. Therefore, PE fibers demonstrated the most effective enhancement in tensile behavior, followed by K-PVA fibers, while N-PVA fibers showed relatively weaker reinforcement effects.

- (3)

- Fractographic analysis of fiber fracture surfaces revealed that the fiber type significantly affected the microscopic failure mechanisms and energy dissipation modes of ECCs materials. For ECCs specimens incorporating PE fibers, fiber pull-out from the matrix was the predominant feature, indicating relatively weak interfacial bonding between the fibers and the matrix. The energy dissipation was mainly dominated by the pull-out process, which contributed to improved matrix toughness. In the case of K-PVA fibers, surface modification enhanced the interfacial bonding strength. During tensile loading, they not only interacted effectively with the matrix and suppressed crack propagation, but also showed pronounced plastic deformation and splitting features. These features indicate a synergistic energy dissipation mechanism involving the coexistence of fiber pull-out and rupture. By contrast, N-PVA fibers showed poor dispersion and weak interfacial bonding, which limited their bridging capability at crack locations. As a result, the dominant energy dissipation mode was early-stage brittle fracture, offering limited effectiveness in crack suppression. In summary, the interfacial bonding strength between fibers and the matrix, the uniformity of fiber dispersion, and the deformation and failure characteristics of fibers under tensile loading are critical factors that govern the fracture mechanisms and toughness enhancement of ECCs materials.

- (4)

- The ANN prediction model developed based on both literature and experimental data was able to accurately predict the bilinear tensile constitutive behavior of ECCs. By inputting ten material-related parameters, the model effectively predicted first cracking strain, first cracking stress, ultimate strain, and ultimate stress, demonstrating a high level of prediction accuracy. Sensitivity analysis revealed that fiber content and fiber strength were the most influential factors affecting ECCs tensile performance, while other matrix components had relatively limited impact. In addition, the ANN model was experimentally validated and successfully predicted key parameters for the validation group. The results indicate that the ANN model can accurately predict the tensile behavior of ECCs materials, thereby providing a reference basis for material design and multi-parameter optimization. However, the model still presents certain limitations, including insufficient dataset size and the lack of incorporation of physical information. Future studies should aim to expand the dataset, explore a broader range of ML algorithms for comparative modeling, and integrate physical knowledge into the modeling process to further improve the accuracy and applicability of the predictions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kan, L.-L.; Wang, W.-S.; Liu, W.-D.; Wu, M. Development and characterization of fly ash based PVA fiber reinforced Engineered Geopolymer Composites incorporating metakaolin. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 108, 103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liang, L.; Jiang, F.; Tang, Z.; Sun, X.; Yu, J.; Li, V.C.; Yu, K. New opportunity: Materials genome strategy for engineered cementitious composites (ECC) design. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 159, 106009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.-T.; Weng, K.-F.; Zhu, J.-X.; Xiang, Y.; Dai, J.-G.; Li, V.C. Engineered/strain-hardening cementitious composites (ECC/SHCC) with an ultra-high compressive strength over 210 MPa. Compos. Commun. 2021, 26, 100775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Xu, S. A strain-hardening cementitious composites with the tensile capacity up to 8%. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 137, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.-Y.; Huang, B.-T.; Li, V.C.; Dai, J.-G. High-strength high-ductility Engineered/Strain-Hardening Cementitious Composites (ECC/SHCC) incorporating geopolymer fine aggregates. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 125, 104296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.C.; Wang, S.; Wu, C. Tensile strain-hardening behavior of polyvinyl alcohol engineered cementitious composite (PVA-ECC). Mater. J. 2001, 98, 483–492. [Google Scholar]

- Abo Elwafa, O.; Galal, M.; Kohail, M.; Khalaf, M.A. Experimental investigation on engineered cementitious composites (ECC) with different types of fibers. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2024, 9, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, M.; Zhou, J.; Xu, M. Effect of fibre types on the tensile behaviour of engineered cementitious composites. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 775188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elmoaty, A.E.M.; Morsy, A.M.; Harraz, A.B. Effect of fiber type and volume fraction on fiber reinforced concrete and engineered cementitious composite mechanical properties. Buildings 2022, 12, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, L.S.; Zain, M.R.M.; Lian, O.C.; Saari, N.; Yahya, N.A. Compression and Flexural Behavior of ECC Containing PVA Fibers. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 2022, 30, 277–289. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Yu, J.; Dong, F.; Ye, J. Effect of polyethylene fiber content on physical and mechanical properties of engineered cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 251, 118917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Bai, R.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y. Tailoring of polyethylene fiber surface by coating silane coupling agent for strain hardening cementitious composite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 278, 122263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Qiu, W.; Yuan, Y.; Fan, Z.; Li, A. Study on the physicochemical properties of Chinese PVA fibers: Toward low-cost cement-based composites. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2639, 012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H. Utilization of Local Ingredients for the Production of High-Early-Strength Engineered Cementitious Composites. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2018, 8159869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Wang, W.; Meng, S.; Qiao, Z. Study on Mechanical Properties of Hybrid PVA Fibers Reinforced Cementitious Composites. Tongji Daxue Xuebao/J. Tongji Univ. 2015, 43, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Arain, M.F.; Wang, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H. Study on PVA fiber surface modification for strain-hardening cementitious composites (PVA-SHCC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 197, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.W.; Kamal, M.; Khan, F.A.; Gul, A.; Alam, M.; Shah, F.; Shahzada, K. Performance evaluation of the fresh and hardened properties of different PVA-ECC mixes: An experimental approach. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y. Effect of PVA fiber on mechanical properties of cementitious composite with and without nano-SiO2. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 229, 117068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Li, K.; Zhu, P.; Cheng, Z. Peridynamic study of ECC dynamic failure considering the influence of fiber–matrix interface. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2025, 136, 104783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Sun, M.; Zhang, Y. The Mechanical and Self-Sensing Properties of Carbon Fiber-and Polypropylene Fiber-Reinforced Engineered Cementitious Composites Utilizing Environmentally Friendly Glass Aggregate. Buildings 2024, 14, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbuz, E.; Erdem, S.; Zhang, M. Static and impact performance of engineered cementitious composites with hybrid graphite nano platelets modified PVA and shape memory alloy fibres. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 92, 109776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Baghdadi, H.M.; Kadhum, M.M. Effects of different fiber dosages of PVA and Glass fibers on the interfacial properties of lightweight concrete with engineered cementitious composite. Buildings 2024, 14, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Chen, Y.Z.; Zhu, J.Q.; Sun, T.; Shui, Z.H.; Ling, G.; Zhong, H.X.; Zheng, Y.R. Effect of Modified Polyvinyl Alcohol Fibers on the Mechanical Behavior of Engineered Cementitious Composites. Materials 2019, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Guo, L.; Chen, B.; Xu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Fei, C. Micromechanics theory guidelines and method exploration for surface treatment of PVA fibers used in high-ductility cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 196, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Uddin, M.N.; Yan, K.; Hossain, M.M.; Golder, M.S.H.; Hoque, M.A. Prediction of the mechanical performance of polyethylene fiber-based engineered cementitious composite (PE-ECC). Low-Carbon Mater. Green Constr. 2024, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, R.H.; Ahmed, H.U.; Fathullah, H.S.; Abdulrahman, A.S.; Abed, F. Tensile Strain Capacity Prediction of Engineered Cementitious Composites (ECC) Using Soft Computing Techniques. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2024, 138, 2925–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Fediuk, R.; Yu, J.; Nikolayevich, K.; Vatin, N.; Bazarov, D.; Yu, K. Performance prediction and analysis of engineered cementitious composites based on machine learning. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 18, 100459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, T.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, D.; Xu, F. Prediction of compressive and flexural strength of coal gangue-based geopolymer using machine learning method. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 44, 112076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Ding, W.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, L. An artificial neural network model on tensile behavior of hybrid steel-PVA fiber reinforced concrete containing fly ash and slag power. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2020, 14, 1299–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yang, J.; Jiang, P.; AlAteah, A.H.; Alsubeai, A.; Alfares, A.M.; Sufian, M. Predicting high-strength concrete’s compressive strength: A comparative study of artificial neural networks, adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system, and response surface methodology. Materials 2024, 17, 4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maio, U.; Gaetano, D.; Greco, F.; Lonetti, P.; Pranno, A. An adaptive cohesive interface model for fracture propagation analysis in heterogeneous media. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 325, 111330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shbeeb, N.I.; Barham, W.S.; Alyahya, W.A. Numerical Simulation of Engineering Cementitious Composite Beams Strengthened with Fiber-Reinforced Polymer and Steel Bars. Fibers 2024, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Chu, X.; Sun, X.Y.; Xu, K.; Deng, H.X.; Chen, J.; Wei, Z.; Lei, M. Machine learning in materials science. InfoMat 2019, 1, 338–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, S.; Li, C. Data-driven prediction on critical mechanical properties of engineered cementitious composites based on machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C618-25a; Standard Specification for Coal Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025.

- GB/T 14684-2022; Sand for Construction. National Standardization Administration Committee of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Huo, Y.; Sun, H.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y. Mechanical properties and its reliability prediction of engineered/strain-hardening cementitious composites (ECC/SHCC) with different moisture contents at negative temperatures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 134, 104812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JC/T 2461-2018; Standard Test Method for the Mechanical Properties of Ductile Fiber Reinforced Cementitious Composites. Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- GB/T 17671-2021; Test method of Cement Mortar Strength (ISO Method). State Administration for Market Regulation, Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Said, S.H.; Razak, H.A.; Othman, I. Strength and deformation characteristics of engineered cementitious composite slabs with different polymer fibres. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2015, 34, 1950–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.-Q.; Yu, J.-T.; Dai, J.-G.; Lu, Z.-D.; Shah, S.P. Development of ultra-high performance engineered cementitious composites using polyethylene (PE) fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 158, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Sui, L.; Zhu, Z. Optimal design of a low-cost high-performance hybrid fiber engineered cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 345, 128372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Su, L.; Tian, J. Advanced nuclear magnetic resonance technology analysis of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete for optimized pore structure and strength. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 467, 140383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Yao, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, F.; Li, J.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Sun, M.; Han, L. Study on the Correlation Between Mechanical Properties, Water Absorption, and Bulk Density of PVA Fiber-Reinforced Cement Matrix Composites. Buildings 2024, 14, 3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.-H.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, V.C. Fiber-bridging constitutive law of engineered cementitious composites. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2008, 6, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Li, V.C. Crack bridging in fiber reinforced cementitious composites with slip-hardening interfaces. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1997, 45, 763–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Ozbulut, O.E.; Sherif, M.M. Mechanical characterization of high-strength and ultra-high-performance engineered cementitious composites reinforced with polyvinyl alcohol and polyethylene fibers subjected to monotonic and cyclic loading. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 148, 105472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; He, R.; Chen, S.; Li, Y. Mechanical properties and impermeability of high performance cementitious composite reinforced with polyethylene fibers. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2013, 6, 239. [Google Scholar]

- Pakravan, H.; Jamshidi, M.; Latifi, M. The effect of hydrophilic (polyvinyl alcohol) fiber content on the flexural behavior of engineered cementitious composites (ECC). J. Text. Inst. 2018, 109, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Hong, Y.; Sun, J.; Qiu, Y. Influence of treatment duration on hydrophobic recovery of plasma-treated ultrahigh modulus polyethylene fiber surfaces. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 110, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Yin, R.; Yao, J.; Leung, C.K. Surface modification of polyethylene fiber by ozonation and its influence on the mechanical properties of Strain-Hardening Cementitious Composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 177, 107446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, D.-Y.; Guo, L.-P.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.-P.; Chen, B.; Li, D.-X.; Li, S.-C.; Mechtcherine, V. Micro-mechanical model for ultra-high strength and ultra-high ductility cementitious composites (UHS-UHDCC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 267, 120668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-D.; Guo, L.-P.; Chen, B.; Lyu, B.-C.; Fei, X.-P.; Bian, R.-S. Effect of PE fiber coated by polydopamine and nano-SiO2 on the strain hardening behavior of ultra-high-strength and high-ductility cementitious composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 136, 104852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthiwarapirak, P.; Matsumoto, T.; Kanda, T. Multiple cracking and fiber bridging characteristics of engineered cementitious composites under fatigue flexure. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2004, 16, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Guo, L.; Chen, B. An optimum polyvinyl alcohol fiber length for reinforced high ductility cementitious composites based on theoretical and experimental analyses. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 259, 119824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Guo, L.P.; Chen, B. Theoretical analysis on optimal fiber-matrix interfacial bonding and corresponding fiber rupture effect for high ductility cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 223, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, V. Research on production, performance and fibre dispersion of PVA engineering cementitious composites. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2009, 25, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baulin, A.; Cao, Y.; Chan, J.; Giesbrecht, B.; Heinrichs, A.; Katsaganis, S.; Kolybaba, D.; Krueger, S.; Leverington, B.; Li, T. Attenuation length and spectral response of Kuraray SCSF-78MJ scintillating fibres. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 2013, 715, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, S. PVA fiber/cement-based interface in silane coupler KH560 reinforced high performance concrete–Experimental and molecular dynamics study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 395, 132184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arain, M.F.; Wang, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H. Experimental and numerical study on tensile behavior of surface modified PVA fiber reinforced strain-hardening cementitious composites (PVA-SHCC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 217, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Lin, Z.; Li, V.C. Tensile stress-strain modeling of pseudostrain hardening cementitious composites. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2000, 12, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, C.; Li, K.; Zhang, P.; Cong, L.; Chen, D. An experimental and analytical study on a damage constitutive model of engineered cementitious composites under uniaxial tension. Materials 2022, 15, 6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Li, Q.; Teng, X.; Luo, D. Development of low-carbon sea sand engineered cementitious composites (LSECCs): Performance, cracking behavior and trilinear tensile constitutive model. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.C. Engineered Cementitious Composites (ECC): Bendable Concrete for Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Behrang, M.; Assareh, E.; Ghanbarzadeh, A.; Noghrehabadi, A. The potential of different artificial neural network (ANN) techniques in daily global solar radiation modeling based on meteorological data. Sol. Energy 2010, 84, 1468–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.Y.; Kim, H.; Lee, Y.-J.; Sim, S.-H. Prediction model for mechanical properties of lightweight aggregate concrete using artificial neural network. Materials 2019, 12, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ranade, R.; Zhang, Q.; Ni, W.; Li, V.C. Mechanical and thermal properties of green lightweight engineered cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 48, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepech, M.D.; Li, V.C. Water permeability of engineered cementitious composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2009, 31, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahmaran, M.; Lachemi, M.; Hossain, K.M.; Ranade, R.; Li, V.C. Influence of aggregate type and size on ductility and mechanical properties of engineered cementitious composites. ACI Mater. J. 2009, 106, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahmaran, M.; Özbay, E.; Yücel, H.E.; Lachemi, M.; Li, V.C. Frost resistance and microstructure of Engineered Cementitious Composites: Influence of fly ash and micro poly-vinyl-alcohol fiber. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ranade, R.; Ni, W.; Li, V.C. On the use of recycled tire rubber to develop low E-modulus ECC for durable concrete repairs. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 46, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, S.H.; Razak, H.A.; Othman, I. Flexural behavior of engineered cementitious composite (ECC) slabs with polyvinyl alcohol fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 75, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ranade, R.; Ni, W.; Li, V.C. Development of green engineered cementitious composites using iron ore tailings as aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 44, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Wu, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, J. Study on mechanical properties of cost-effective polyvinyl alcohol engineered cementitious composites (PVA-ECC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 78, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahmaran, M.; Lachemi, M.; Hossain, K.M.; Li, V.C. Internal curing of engineered cementitious composites for prevention of early age autogenous shrinkage cracking. Cem. Concr. Res. 2009, 39, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun-Felekoğlu, K.; Felekoğlu, B.; Ranade, R.; Lee, B.Y.; Li, V.C. The role of flaw size and fiber distribution on tensile ductility of PVA-ECC. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 56, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Qian, S.; Li, V.C. Influence of fly ash type on mechanical properties and self-healing behavior of Engineered Cementitious Composite (ECC). In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Fracture Mechanics of Concrete and Concrete Structures (FraMCoS-9), Berkeley, CA, USA, 29 May–1 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Clack, H.; Xia, T.; Bao, Y.; Wu, K.; Shi, H.; Li, V. Effect of TiO2 and fly ash on photocatalytic NOx abatement of engineered cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 236, 117559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yu, J.; Zhou, J.; Bao, Y.; Li, V.C. Effect of curing relative humidity on mechanical properties of engineered cementitious composites at multiple scales. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 284, 122834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Zhang, Y. Mechanical properties of a PVA fiber reinforced engineered cementitious composite. Proc. Int. Struct. Eng. Constr. 2014, 1, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.-H.; Yang, Y.; Li, V.C. Use of high volumes of fly ash to improve ECC mechanical properties and material greenness. ACI Mater. J. 2007, 104, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Qian, S.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Li, V.C. Tailoring engineered cementitious composites with local ingredients. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 101, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Abdalla, J.A.; Hawileh, R.A.; Zhang, X. Multiple-scaled investigations on mechanical properties of medium-early-strength PVA-ECC with recycled tire crumb rubber incorporated. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e04931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Jiang, B.; Gu, D.; Hu, J.; He, Q.; Xu, L.; Pan, J. Shear transfer mechanism of headed stud connectors in engineered cementitious composites (ECC): Experimental observation, numerical investigation and analytical model. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 99, 111565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Gao, Z.; Xia, M.; Guo, R. Study on bonding behavior of FRP grid-ECC composite layer and concrete with quantitative interface treatment. Eng. Struct. 2023, 294, 116768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, A.; Liu, Z.; Li, F.; Li, S. Experimental investigation of corrosion-damaged RC beams strengthened in flexure with FRP grid-reinforced ECC matrix composites. Eng. Struct. 2021, 244, 112779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lin, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, V.C. Mechanical performance of ECC with high-volume fly ash after sub-elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 99, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yin, S.; Hua, Y. Flexural behavior of BFRP reinforced seawater sea-sand concrete beams with textile reinforced ECC tension zone cover. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 278, 122372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Liang, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, X. Slender CFST columns strengthened with textile-reinforced engineered cementitious composites under axial compression. Eng. Struct. 2021, 241, 112483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Ren, Q.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, J.-N.; Wang, Q. Tensile and flexural behavior of polyvinyl alcohol engineered cementitious composites using steel slag aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 487, 142047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyati, M.D.; Huang, W.-H.; Hsu, H.-L.; Loekito, I.P. Improving properties of Engineered Cementitious Composite (ECC) using Bacillus subtilis immobilized in silica gel. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, R.; Li, Y.; Guan, X. Effect of crystalline admixtures on mechanical, self-healing and transport properties of engineered cementitious composite. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 124, 104256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, V.; Su, H.; Gu, C. Durability study on engineered cementitious composites (ECC) under sulfate and chloride environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 133, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, C.; Su, H.; Li, V.C. Influence of micro-cracking on the permeability of engineered cementitious composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 72, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahmaran, M.; Li, V.C. Influence of microcracking on water absorption and sorptivity of ECC. Mater. Struct. 2009, 42, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Sun, W.; Chen, L.; Chen, B.; Arkin, E.; Du, L.; Pathirage, M. Engineered Cementitious Composites using Chinese local ingredients: Material preparation and numerical investigation. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e00852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, V.C. Engineered cementitious composites with high-volume fly ash. ACI Mater. J.-Am. Concr. Inst. 2007, 104, 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Long, X.; Ye, M.; Jiang, H.; Liu, L.; Zhai, K. Experimental study of bond behavior between rebar and PVA-engineered cementitious composite (ECC) using pull-out tests. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 633404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, S.H.; Razak, H.A. The effect of synthetic polyethylene fiber on the strain hardening behavior of engineered cementitious composite (ECC). Mater. Des. 2015, 86, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, E.; Abdalla, J.; Hawileh, R. Mechanical performance of sustainable PE-ECC using GGBS and dune sands. Procedia Struct. Integrity 2025, 68, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, C.; Xu, M.; Jin, C. Experimental investigation of flexural and punching behavior for plain PE-ECC slabs with different fiber volume fractions and span-depth ratios. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 441, 137502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xiao, J.; Wu, Z. The effect of fiber content on the static and dynamic performance of PE-ECC. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Abdalla, J.A.; Yu, J.; Chen, Y.; Hawileh, R.A.; Mahmoudi, F. Use of polypropylene fibers to mitigate spalling in high strength PE-ECC under elevated temperature. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhuge, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y. Effect of mechanochemistry on graphene dispersion and its application in improving the mechanical properties of engineered cementitious composites. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, R.; Liu, L.; Huang, X.; Lin, J. Effects of Polyethylene Terephthalate Particle Size on the Performance of Engineered Cementitious Composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Ou, J. An economical ultra-high ductile engineered cementitious composite with large amount of coarse river sand. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 201, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Zhang, D.; Li, V.C. Material processing, microstructure, and composite properties of low carbon Engineered Cementitious Composites (ECC). Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 134, 104790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsiantis, S.B.; Kanellopoulos, D.; Pintelas, P.E. Data preprocessing for supervised leaning. Int. J. Comp. 2006, 1, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen, M.; Menhaj, M. Training multilayer networks with the Marquardt algorithm. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1994, 5, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, T.A.d.C.; Felix, E.F.; de Sousa, C.M.A.; Pedroso, G.O.M.; Motta, M.F.B.; Prado, L.P. Influence of the ANN Hyperparameters on the Forecast Accuracy of RAC’s Compressive Strength. Materials 2023, 16, 7683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.Q.; Awan, H.A.; Rasul, M.; Siddiqi, Z.A.; Pimanmas, A. Optimized artificial neural network model for accurate prediction of compressive strength of normal and high strength concrete. Clean. Mater. 2023, 10, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.; Salih Mohammed, A. Surrogate models to predict the long-term compressive strength of cement-based mortar modified with fly ash. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 4187–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constituents | Cement | Fly Ash |

|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 15.41 | 58.25 |

| Al2O3 | 4.43 | 26.45 |

| Fe2O3 | 4.91 | 2.50 |

| CaO | 61.54 | 5.60 |

| MgO | 0.72 | 0.93 |

| Na2O | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| K2O | 0.50 | 0.15 |

| TiO2 | 0.60 | 0.05 |

| Loss on ignition | 2.88 | 3.2 |

| Fiber Type | Diameter (μm) | Length (mm) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Density (g/cm3) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | 21.6 | 12 | 3120 | 0.97 | 126 |

| K-PVA | 31 | 12 | 1600 | 1.3 | 41 |

| N-PVA | 31 | 12 | 1450 | 1.3 | 37.5 |

| Mix ID | Cement (kg/m3) | Fly Ash (kg/m3) | Water (kg/m3) | River Sand (kg/m3) | Superplasticizer (kg/m3) | Fiber Type | Fiber Content (vol %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE1.3 | 555.3 | 666.4 | 329.9 | 439.8 | 8.6 | PE | 1.3 |

| PE1.5 | 555.3 | 666.4 | 329.9 | 439.8 | 8.6 | PE | 1.5 |

| PE1.7 | 555.3 | 666.4 | 329.9 | 439.8 | 8.6 | PE | 1.7 |

| K-PVA 1.3 | 555.3 | 666.4 | 329.9 | 439.8 | 8.6 | K-PVA | 1.3 |

| K-PVA 1.5 | 555.3 | 666.4 | 329.9 | 439.8 | 8.6 | K-PVA | 1.5 |

| K-PVA 1.7 | 555.3 | 666.4 | 329.9 | 439.8 | 8.6 | K-PVA | 1.7 |

| N-PVA 1.3 | 555.3 | 666.4 | 329.9 | 439.8 | 8.6 | N-PVA | 1.3 |

| N-PVA 1.5 | 555.3 | 666.4 | 329.9 | 439.8 | 8.6 | N-PVA | 1.5 |

| N-PVA 1.7 | 555.3 | 666.4 | 329.9 | 439.8 | 8.6 | N-PVA | 1.7 |

| Specimens Group | σcr/MPa | σp/MPa | εtu/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE1.3 | 4.15 ± 0.24 | 5.06 ± 0.28 | 3.36 ± 0.23 |

| PE1.5 | 4.3 ± 0.26 | 5.26 ± 0.32 | 3.39 ± 0.33 |

| PE1.7 | 4.45 ± 0.31 | 5.64 ± 0.36 | 3.55 ± 0.28 |

| K-PVA1.3 | 3.11 ± 0.30 | 4.19 ± 0.39 | 3.03 ± 0.32 |

| K-PVA1.5 | 3.72 ± 0.42 | 4.73 ± 0.38 | 3.19 ± 0.21 |

| K-PVA1.7 | 4.15 ± 0.31 | 5.01 ± 0.35 | 3.33 ± 0.32 |

| N-PVA1.3 | 2.11 ± 0.31 | 2.61 ± 0.25 | 2.56 ± 0.14 |

| N-PVA1.5 | 3.13 ± 0.37 | 3.57 ± 0.34 | 3.11 ± 0.50 |

| N-PVA1.7 | 2.21 ± 0.33 | 2.96 ± 0.23 | 2.96 ± 0.24 |

| Input Parameters | Unit | Range | Mean | Median | Mode | Standard Deviation | Sample Variance | Kurtosis | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement | kg/m3 | 190–1218 | 704 | 725.08 | 641.64 | 171.33 | 29,355.11 | 6.2 | 5.03 |

| Fly ash | kg/m3 | 109–1644.86 | 876.93 | 984.07 | 919.86 | 255.98 | 65,524.05 | 1.22 | 3.73 |

| Sand | kg/m3 | 129–1237.67 | 683.34 | 733.45 | 713.72 | 184.78 | 34,143.03 | 14.02 | 3.18 |

| Water | kg/m3 | 185–726.73 | 455.87 | 389.09 | 370.55 | 90.29 | 8151.98 | −1.15 | 0.69 |

| Superplasticizer | kg/m3 | 0–156.18 | 78.09 | 85.23 | 101.62 | 26.03 | 677.56 | 14.05 | 1.96 |

| Fiber Content | kg/m3 | 6.41–48 | 27.2 | 26.76 | 30.8 | 6.93 | 48.05 | 6.71 | 0.68 |

| Length of Fiber | mm | 8–13.0 | 10.5 | 9.69 | 9.06 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 10.01 | 7.41 |

| Diameter of Fiber | μm | 8–200 | 104 | 98.53 | 97.51 | 32 | 1024 | 6.44 | 3.44 |

| Nominal strength of Fiber | MPa | 626–3000 | 1813 | 1934.1 | 1857.02 | 395.67 | 156,552.11 | 14.74 | 7.46 |

| Elastic modulus of Fiber | GPa | 6–210 | 108 | 114.02 | 111.59 | 34 | 1156 | 9.98 | 2.54 |

| Sr. No. | Types of Fibers | No of Data Points | Reference and Experimental Test Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Polyvinyl alcohol Fiber (PVA) | 125 | [67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98] |

| 2 | Polyethylene Fiber (PE) | 42 | [4,37,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106] |

| 3 | Polypropylene Fiber (PP) | 1 | [107] |

| Hyperparameters | Range | The Optimal Value for Different Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Cracking Strain | First Cracking Stress | Ultimate Strain | Ultimate Stress | ||

| Hidden layer size | 1–100 | 11 | 44 | 78 | 44 |

| Set | Evaluation | First Cracking Strain | First Cracking Stress | Ultimate Strain | Ultimate Stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | RMSE | 0.147487 | 0.07286 | 0.111199 | 0.068835 |

| R2 | 0.833297 | 0.980921 | 0.982996 | 0.960416 | |

| R | 0.952742 | 0.991812 | 0.99483 | 0.995462 | |

| MAE | 0.105951 | 0.053928 | 0.082305 | 0.050887 | |

| Testing | RMSE | 0.145616 | 0.086989 | 0.125152 | 0.086209 |

| R2 | 0.829304 | 0.843067 | 0.921049 | 0.86507 | |

| R | 0.914375 | 0.947678 | 0.992706 | 0.955019 | |

| MAE | 0.107275 | 0.061997 | 0.088099 | 0.05698 |

| Set | Evaluation | First Cracking Strain | First Cracking Stress | Ultimate Strain | Ultimate Stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | RMSE | 0.029541 | 0.303779 | 0.419238 | 0.268921 |

| R2 | 0.895024 | 0.974446 | 0.981169 | 0.958358 | |

| R | 0.946058 | 0.997910 | 0.990842 | 0.978966 | |

| MAE | 0.014254 | 0.155181 | 0.203787 | 0.149145 | |

| Testing | RMSE | 0.030421 | 0.364319 | 0.361831 | 0.261071 |

| R2 | 0.869930 | 0.872923 | 0.862853 | 0.953189 | |

| R | 0.954067 | 0.940166 | 0.930410 | 0.977799 | |

| MAE | 0.013107 | 0.153993 | 0.165250 | 0.140601 |

| Set | Evaluation | First Cracking Strain | First Cracking Stress | Ultimate Strain | Ultimate Stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | RMSE | 0.018795 | 0.122708 | 0.318833 | 0.234030 |

| R2 | 0.862550 | 0.955804 | 0.966598 | 0.944258 | |

| R | 0.928736 | 0.977652 | 0.983157 | 0.971729 | |

| MAE | 0.007827 | 0.057668 | 0.176567 | 0.127093 | |

| Testing | RMSE | 0.028040 | 0.190068 | 0.379368 | 0.270602 |

| R2 | 0.736408 | 0.863838 | 0.959584 | 0.892715 | |

| R | 0.827365 | 0.936994 | 0.998009 | 0.964249 | |

| MAE | 0.013500 | 0.122637 | 0.263594 | 0.200312 |

| Removed Parameter | First Cracking Strain | First Cracking Stress | Ultimate Strain | Ultimate Stress | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | Rank | RMSE | Rank | RMSE | Rank | RMSE | Rank | |

| Cement | 0.406527 | 4 | 0.56342655 | 5 | 1.5544125 | 3 | 2.3899116 | 2 |

| Fly ash | 0.3105703 | 7 | 0.4924256 | 8 | 0.822701 | 10 | 1.3638533 | 7 |

| Sand | 0.3031504 | 8 | 0.29378688 | 10 | 1.13849062 | 8 | 0.620447 | 10 |

| Water | 0.34189722 | 5 | 0.5503779 | 7 | 1.12819292 | 9 | 0.963163 | 9 |

| Superplasticizer | 0.24652216 | 9 | 0.5555797 | 6 | 1.14126928 | 7 | 1.8987614 | 4 |

| Fiber Content | 0.65544883 | 2 | 1.202515 | 1 | 1.479178 | 4 | 2.65946804 | 1 |

| Length of Fiber | 0.32420578 | 6 | 0.7622586 | 3 | 1.7101413 | 2 | 1.3609549 | 8 |

| Diameter of Fiber | 0.2130584 | 10 | 0.37593833 | 9 | 1.2635776 | 6 | 1.8278564 | 5 |

| Nominal strength of Fiber | 0.769809 | 1 | 1.1155825 | 2 | 1.8959366 | 1 | 1.5406901 | 6 |

| Elastic modulus of Fiber | 0.58451957 | 3 | 0.663625 | 4 | 1.39173594 | 5 | 2.2892183 | 3 |

| Specimens | First Cracking Strain/% | First Cracking Stress/MPa | Ultimate Strain/% | Ultimate Stress/MPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE1.0% | 0.036 | 3.84 | 3.24 | 4.66 |

| K-PVA1.0% | 0.028 | 2.78 | 3.02 | 3.82 |

| N-PVA1.0% | 0.023 | 1.98 | 2.53 | 2.36 |

| Specimens | First cracking Strain/% | First Cracking Stress/MPa | Ultimate Strain/% | Ultimate Stress/MPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE1.0% | 0.041 | 3.65 | 3.21 | 4.48 |

| K-PVA1.0% | 0.029 | 2.93 | 3.19 | 3.68 |

| N-PVA1.0% | 0.025 | 1.98 | 2.64 | 2.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Q.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xia, Z.; Xiong, K.; Yan, J. An Experimental Study on the Mechanical Properties and ANN-Based Prediction of a Tensile Constitutive Model of ECCs. Polymers 2025, 17, 3183. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233183

Zhao Q, Yang Z, Zhang X, Xia Z, Xiong K, Yan J. An Experimental Study on the Mechanical Properties and ANN-Based Prediction of a Tensile Constitutive Model of ECCs. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3183. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233183

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Qi, Zhangfeng Yang, Xiaofeng Zhang, Zhenmeng Xia, Kai Xiong, and Jin Yan. 2025. "An Experimental Study on the Mechanical Properties and ANN-Based Prediction of a Tensile Constitutive Model of ECCs" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3183. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233183

APA StyleZhao, Q., Yang, Z., Zhang, X., Xia, Z., Xiong, K., & Yan, J. (2025). An Experimental Study on the Mechanical Properties and ANN-Based Prediction of a Tensile Constitutive Model of ECCs. Polymers, 17(23), 3183. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233183