Advances in Small Angle Neutron Scattering on Polysaccharide Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

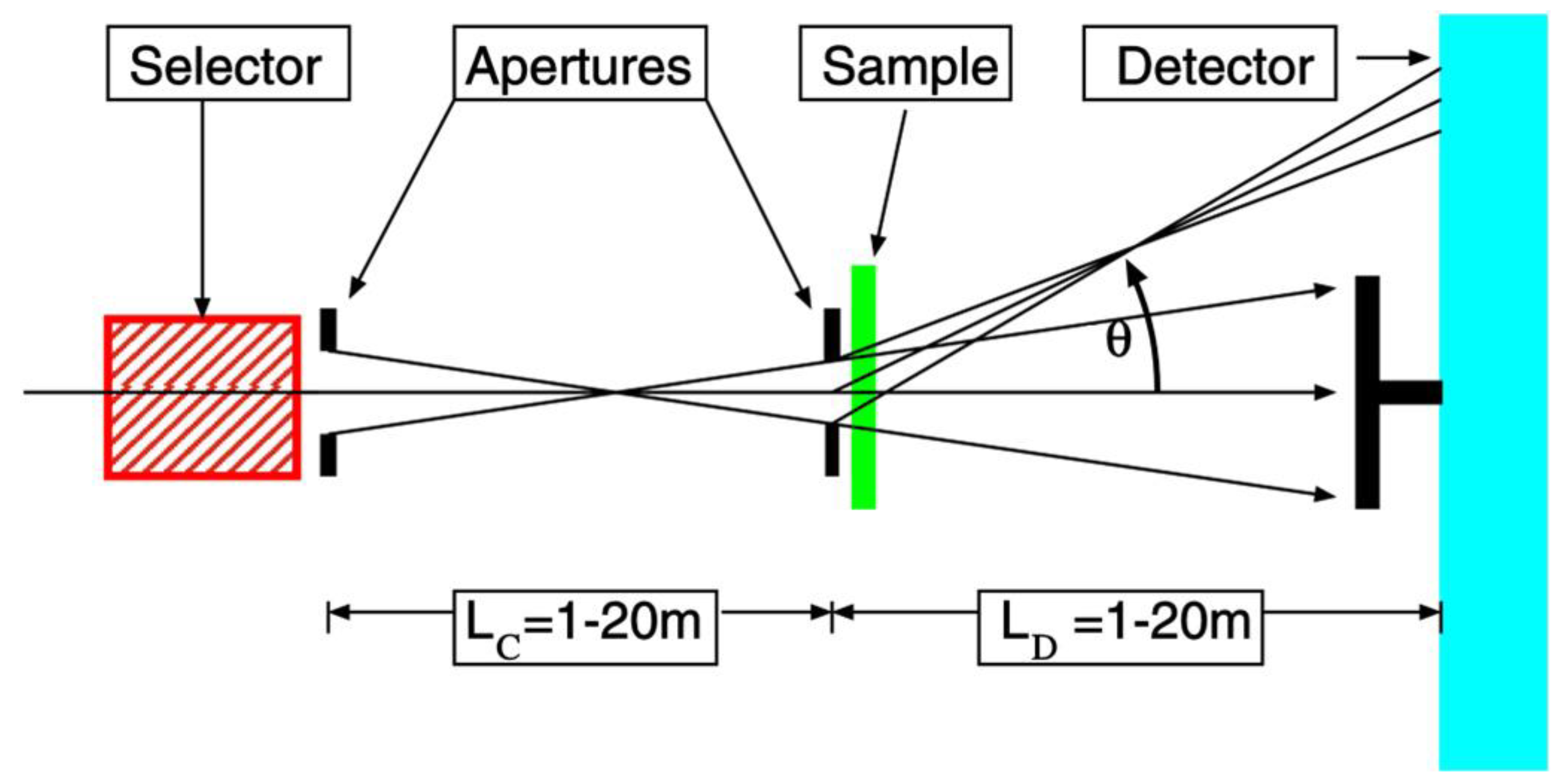

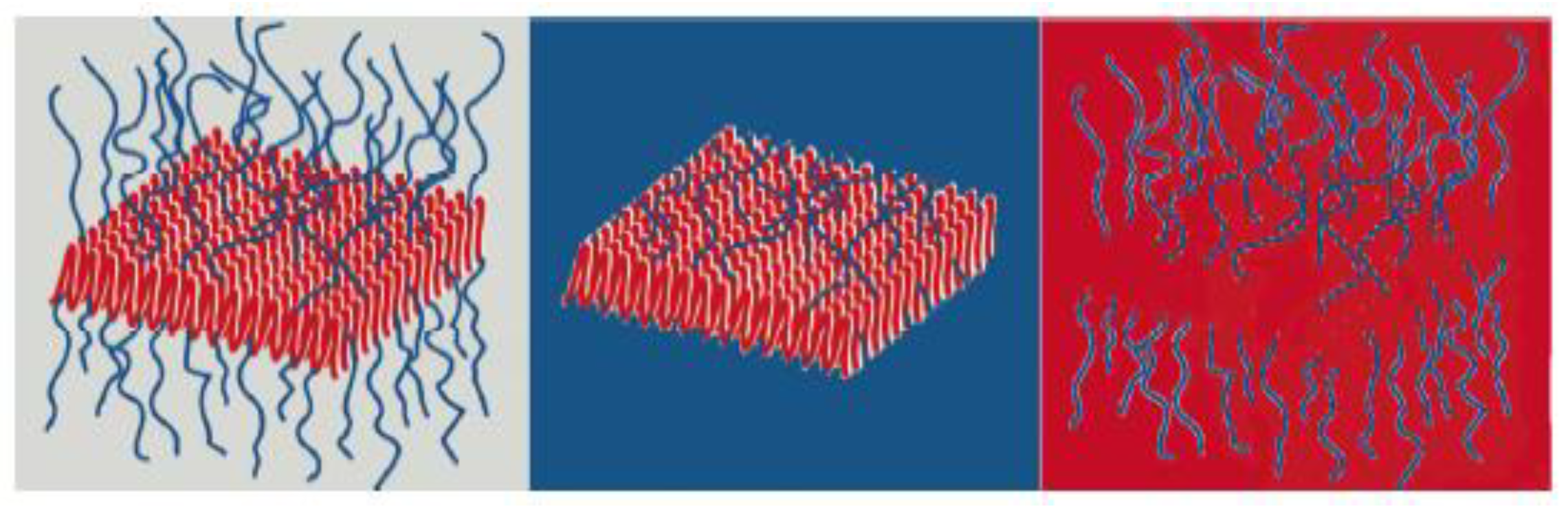

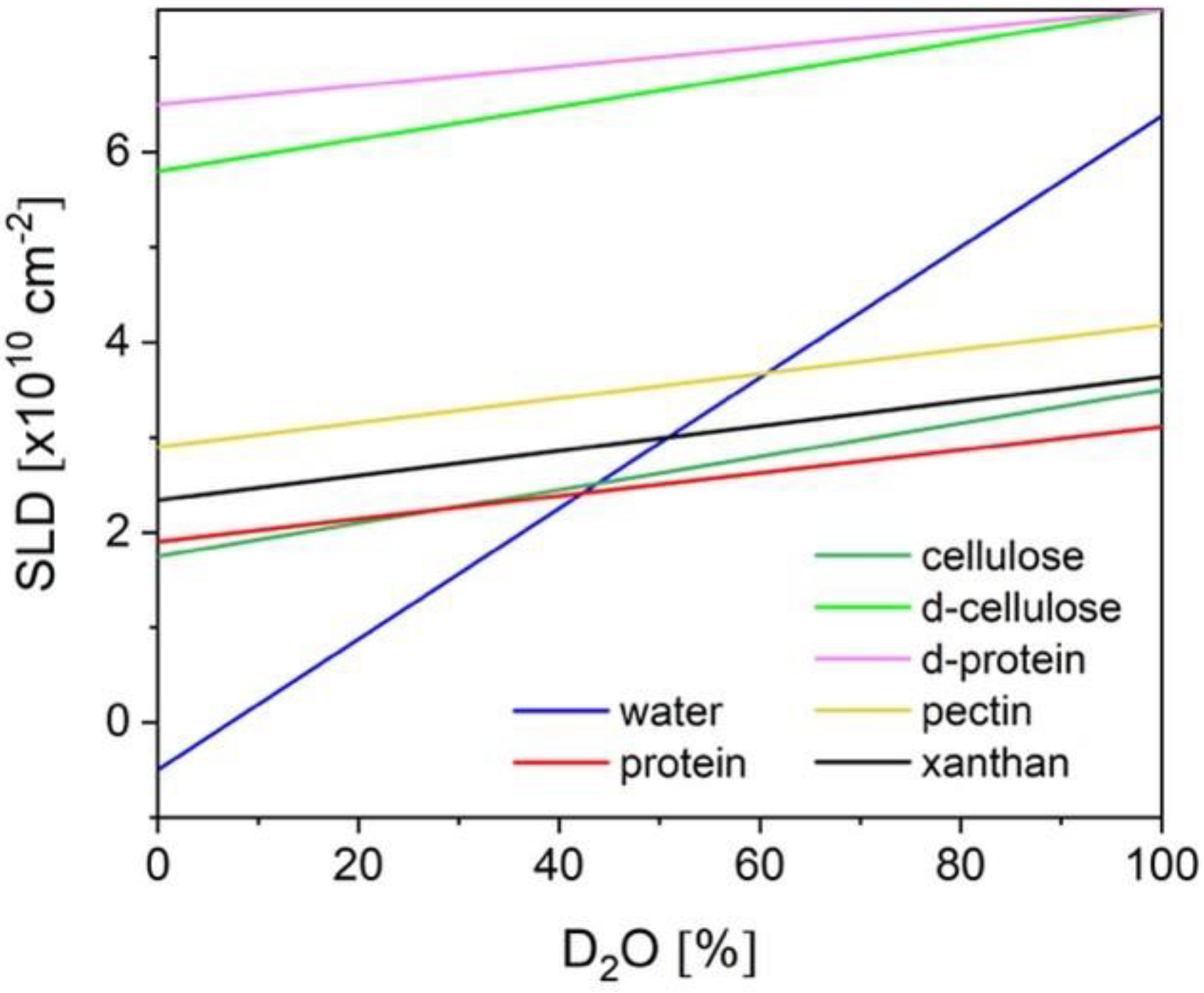

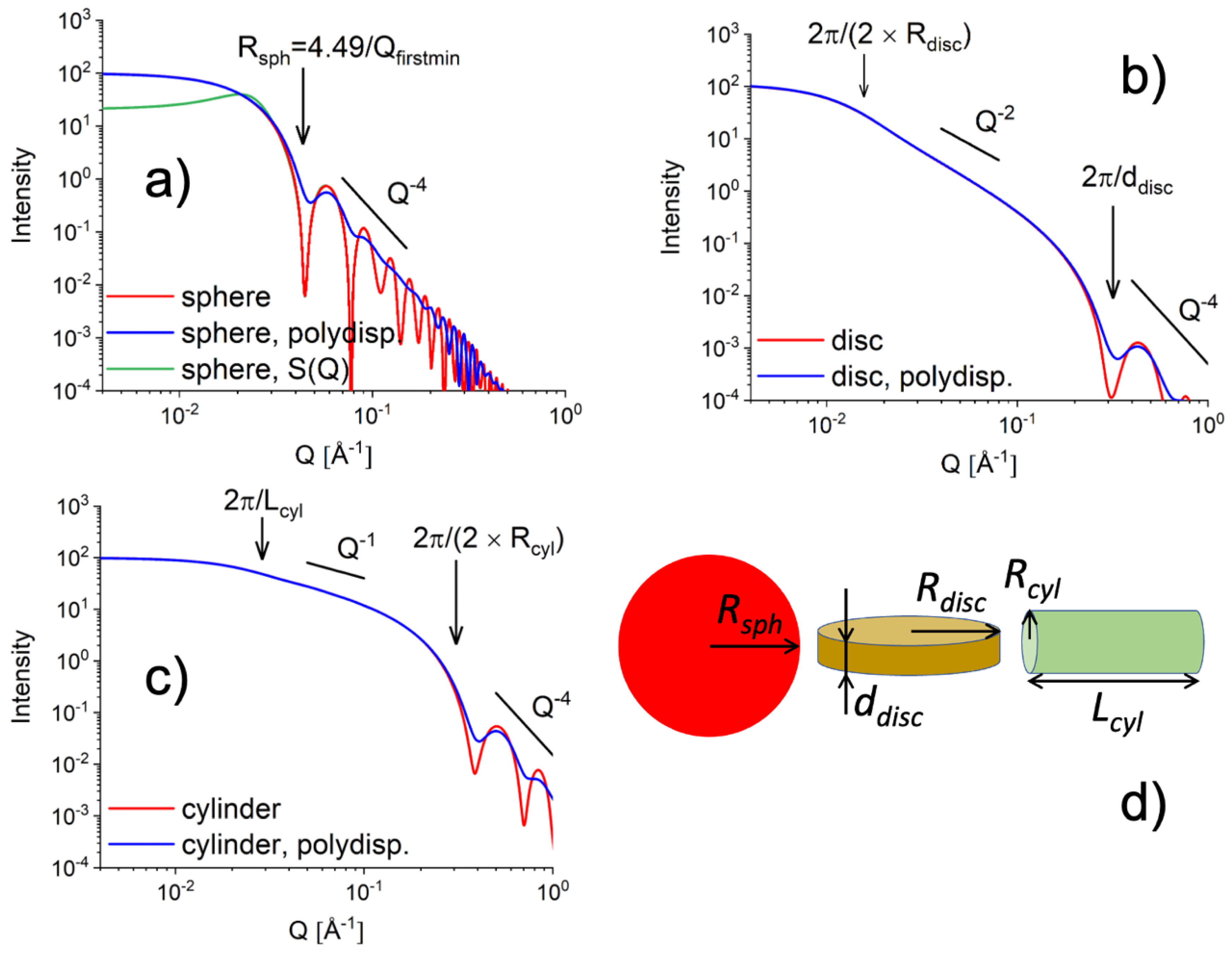

2. Small Angle Neutron Scattering: Fundamentals and Experimental Practices

3. Application of Small Angle Neutron Scattering on Nanostructured Polysaccharide Materials

3.1. Nano-Particulate Systems

3.2. Hydrogel and Nanocomposite Materials

3.3. Self-Assembly and Macromolecular Conformation

3.4. Nanostructured Plant and Food Materials

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Badiei, M.; Asim, N.; Mohammad, M.; Akhtaruzzaman, M.; Samsudin, N.A.; Amin, N.; Sopian, K. Chapter 7—Nanostructured Polysaccharide-Based Materials Obtained from Renewable Resources and Uses. In Innovation in Nano-Polysaccharides for Eco-Sustainability; Singh, P., Manzoor, K., Ikram, S., Annamalai, P.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 163–200. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128234396000155 (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Torpol, K.; Sriwattana, S.; Sangsuwan, J.; Wiriyacharee, P.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. Optimising chitosan–pectin hydrogel beads containing combined garlic and holy basil essential oils and their application as antimicrobial inhibitor. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 2064–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davachi, S.M.; Haramshahi, S.M.A.; Akhavirad, S.A.; Bahrami, N.; Hassanzadeh, S.; Ezzatpour, S.; Hassanzadeh, N.; Kebria, M.M.; Khanmohammadi, M.; Bagher, Z. Development of chitosan/hyaluronic acid hydrogel scaffolds via enzymatic reaction for cartilage tissue engineering. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 30, 103230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Jiao, Z.; Chen, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Xu, F.-J. Hybrids of Polysaccharides and Inorganic Nanoparticles: From Morphological Design to Diverse Biomedical Applications. Accounts Mater. Res. 2023, 4, 1068–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plucinski, A.; Lyu, Z.; Schmidt, B.V.K.J. Polysaccharide nanoparticles: From fabrication to applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 7030–7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, D.; Calandra, P.; Kiselev, M.A. Structural Characterization of Biomaterials by Means of Small Angle X-rays and Neutron Scattering (SAXS and SANS), and Light Scattering Experiments. Molecules 2020, 25, 5624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

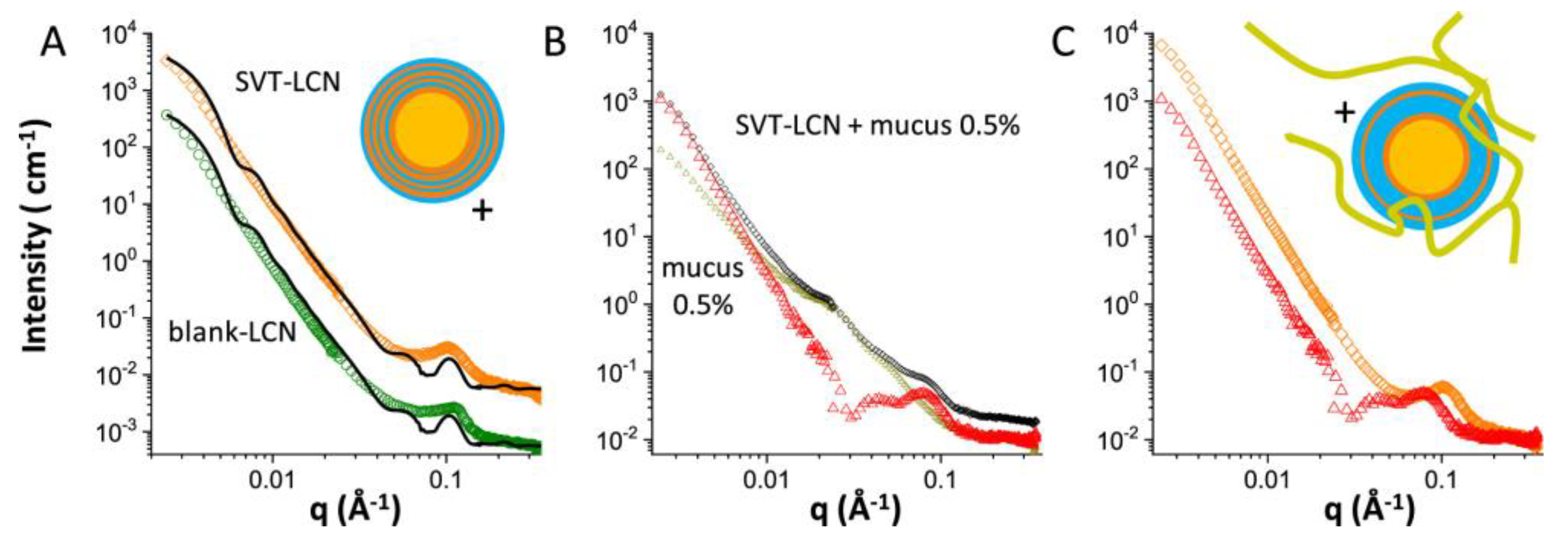

- Clementino, A.R.; Pellegrini, G.; Banella, S.; Colombo, G.; Cantù, L.; Sonvico, F.; Del Favero, E. Structure and Fate of Nanoparticles Designed for the Nasal Delivery of Poorly Soluble Drugs. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 3132–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Sanchez, P.; Assifaoui, A.; Cousin, F.; Moser, J.; Bonilla, M.R.; Ström, A. Impact of Glucose on the Nanostructure and Mechanical Properties of Calcium-Alginate Hydrogels. Gels 2022, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

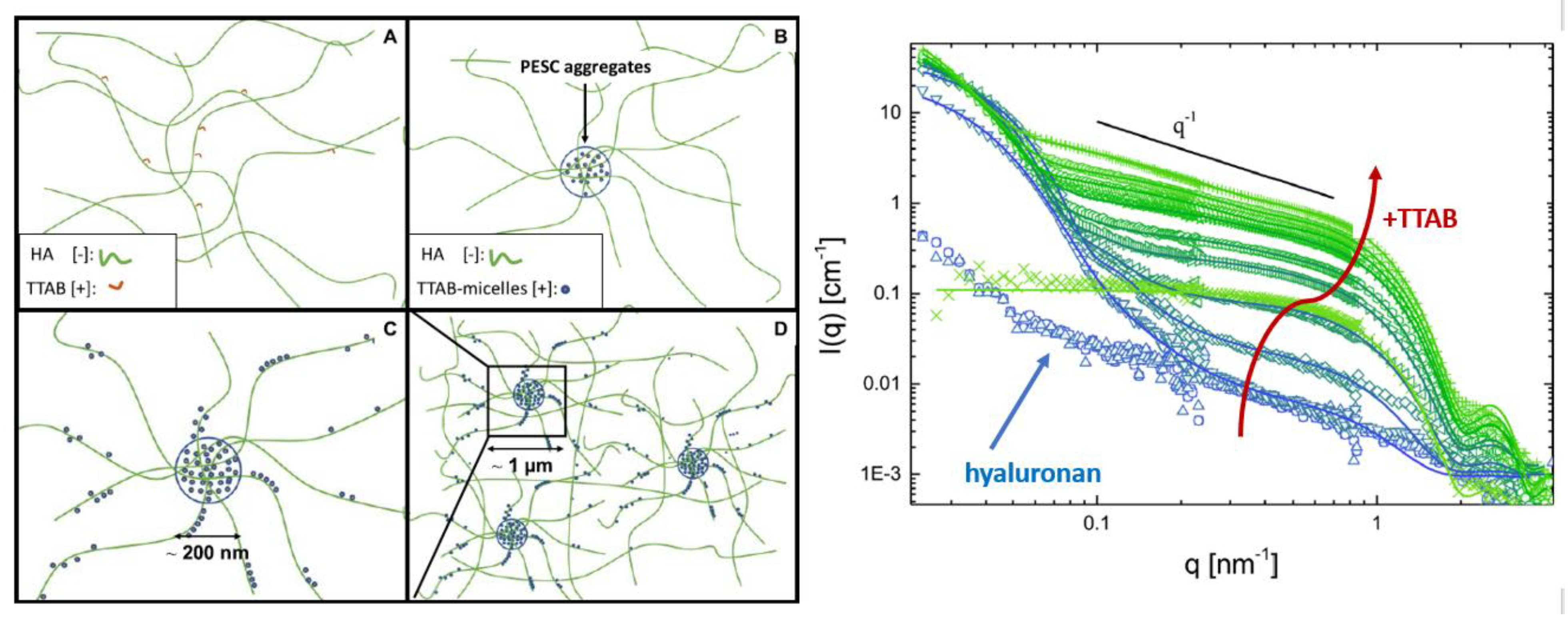

- Buchold, P.; Ram-On, M.; Talmon, Y.; Hoffmann, I.; Schweins, R.; Gradzielski, M. Uncommon Structures of Oppositely Charged Hyaluronan/Surfactant Assemblies under Physiological Conditions. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 3498–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glatter, O.; Kratky, O.K. Small Angle X-ray Scattering; Academic Press: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, L.A.S.; Svergun, D.I. Structure Analysis by Small-Angle X-ray and Neutron Scattering, 1st ed.; Taylor, G.W., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.J. Introduction to Small-Angle Neutron Scattering and Neutron Reflectometry. NIST Center for Neutron Research. 2008; pp. 1–24. Available online: https://ftp.ncnr.nist.gov/summerschool/ss10/pdf/SANS_NR_Intro.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Hollamby, M.J. Practical applications of small-angle neutron scattering. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 10566–10579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammouda, B. SANS from Polymers—Review of the Recent Literature. Polym. Rev. 2010, 50, 14–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.H. Small Angle Neutron Scattering Studies of the Structure and Interaction in Micellar and Microemulsion Systems. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1986, 37, 351–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffries, C.M.; Ilavsky, J.; Martel, A.; Hinrichs, S.; Meyer, A.; Pedersen, J.S.; Sokolova, A.V.; Svergun, D.I. Small-angle X-ray and neutron scattering. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2021, 1, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Raouf, M. (Ed.) Crude Oil Emulsions—Composition Stability and Characterization; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; ISBN 9789535102205. [Google Scholar]

- Sears, V.F. Neutron scattering lengths and cross sections. Neutron News 1992, 3, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuwanshi, V.S.; Su, J.; Garvey, C.J.; Holt, S.A.; Raverty, W.; Tabor, R.F.; Holden, P.J.; Gillon, M.; Batchelor, W.; Garnier, G. Bio-deuterated cellulose thin films for enhanced contrast in neutron reflectometry. Cellulose 2016, 24, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, I.; Cousin, F.; Huchon, C.; Boué, F.; Axelos, M.A. Spatial Structure and Composition of Polysaccharide−Protein Complexes from Small Angle Neutron Scattering. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 1346–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

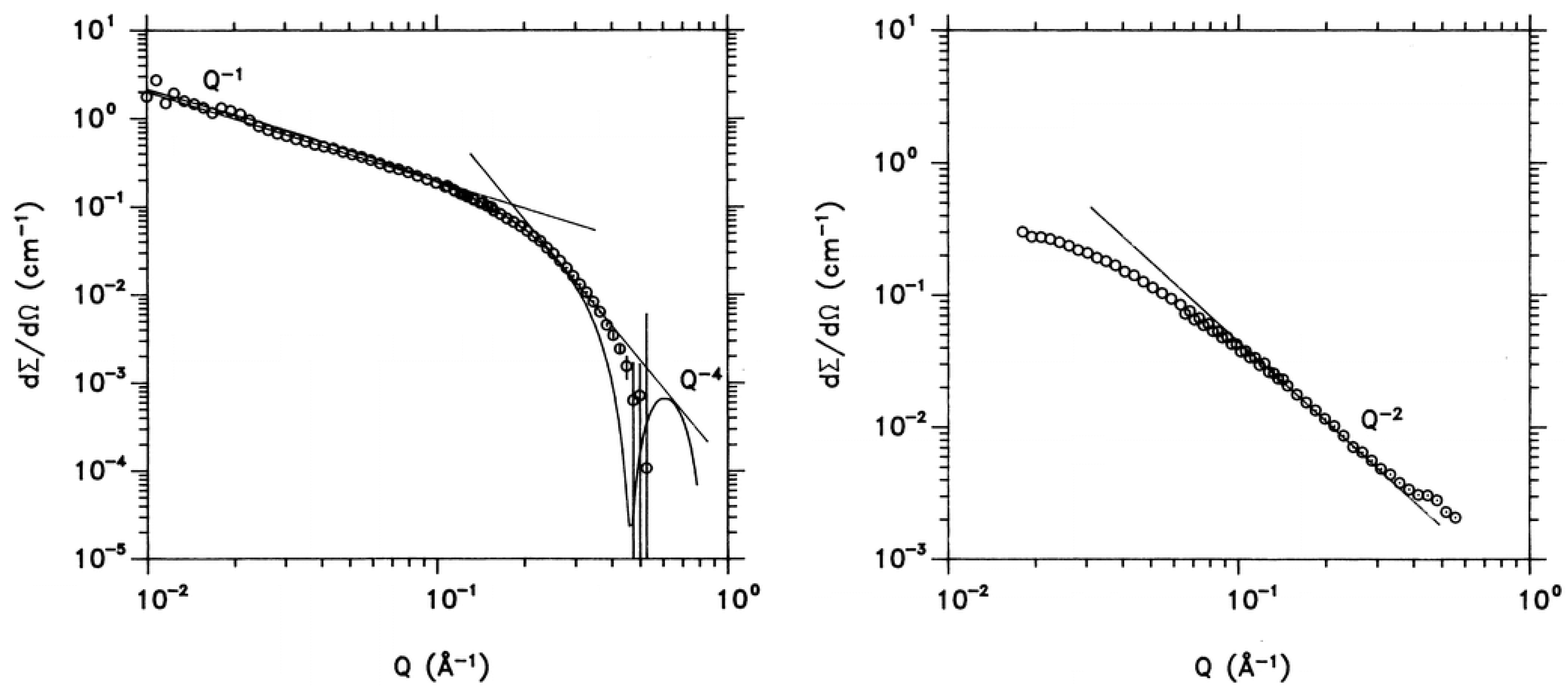

- Papagiannopoulos, A.; Sotiropoulos, K.; Radulescu, A. Scattering investigation of multiscale organization in aqueous solutions of native xanthan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 153, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, J.S. Analysis of small-angle scattering data from colloids and polymer solutions: Modeling and least-squares fitting. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 70, 171–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannopoulos, A.; Vlassi, E.; Radulescu, A. Reorganizations inside thermally stabilized protein/polysaccharide nanocarriers investigated by small angle neutron scattering. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 218, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cola, E.; Cantu’, L.; Brocca, P.; Rondelli, V.; Fadda, G.C.; Canelli, E.; Martelli, P.; Clementino, A.; Sonvico, F.; Bettini, R.; et al. Novel O/W nanoemulsions for nasal administration: Structural hints in the selection of performing vehicles with enhanced mucopenetration. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2019, 183, 110439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Schneck, E.; Noirez, L.; Rahn, S.; Davidovich, I.; Talmon, Y.; Gradzielski, M. Effect of Polymer Architecture on the Phase Behavior and Structure of Polyelectrolyte/Microemulsion Complexes (PEMECs). Macromolecules 2020, 53, 4055–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannopoulos, A.; Sklapani, A.; Len, A.; Radulescu, A.; Pavlova, E.; Slouf, M. Protein-induced transformation of unilamellar to multilamellar vesicles triggered by a polysaccharide. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 303, 120478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siewert, C.; Haas, H.; Nawroth, T.; Ziller, A.; Nogueira, S.; Schroer, M.; Blanchet, C.; Svergun, D.; Radulescu, A.; Bates, F.; et al. Investigation of charge ratio variation in mRNA—DEAE-dextran polyplex delivery systems. Biomaterials 2018, 192, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaudoin, C.; Grillo, I.; Cousin, F.; Gehrke, M.; Ouldali, M.; Arteni, A.-A.; Picton, L.; Rihouey, C.; Simelière, F.; Bochot, A.; et al. Hybrid systems combining liposomes and entangled hyaluronic acid chains: Influence of liposome surface and drug encapsulation on the microstructure. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 628, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Shoaib, T.; Rutland, M.W.; Beller, J.; Do, C.; Espinosa-Marzal, R.M. Insight into the assembly of lipid-hyaluronan complexes in osteoarthritic conditions. Biointerphases 2023, 18, 021005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, V.; da Silva, M.A.; Schmitt, J.; Muñoz-Garcia, J.C.; Gabrielli, V.; Scott, J.L.; Angulo, J.; Khimyak, Y.Z.; Edler, K.J. Surfactant controlled zwitterionic cellulose nanofibril dispersions. Soft Matter 2018, 14, 7793–7800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada, D.; Nishiyama, Y.; Röder, T.; Porcar, L.; Zahra, H.; Trogen, M.; Sixta, H.; Hummel, M. Process-dependent nanostructures of regenerated cellulose fibres revealed by small angle neutron scattering. Polymer 2021, 218, 123510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

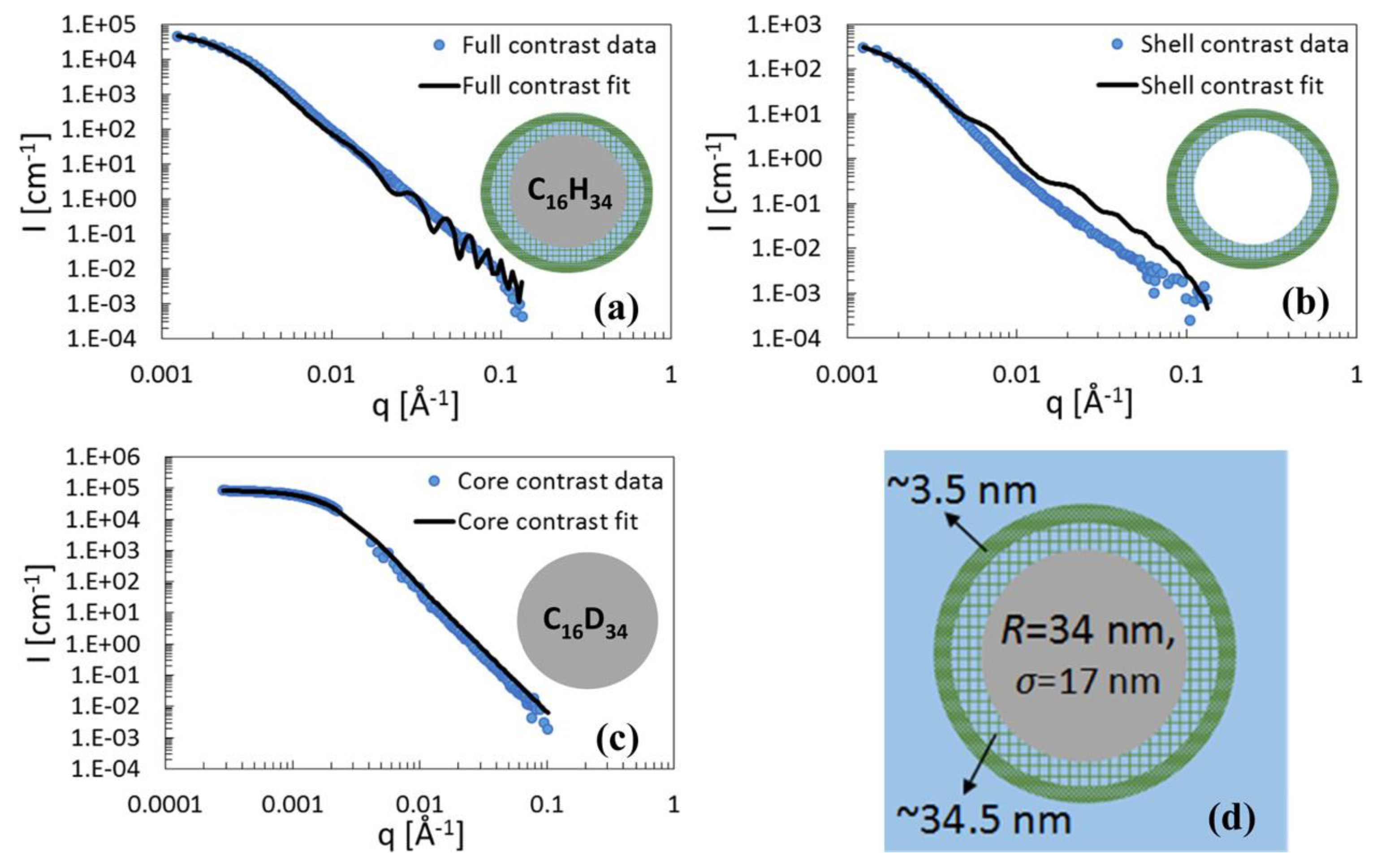

- Napso, S.; Rein, D.M.; Fu, Z.; Radulescu, A.; Cohen, Y. Structural Analysis of Cellulose-Coated Oil-in-Water Emulsions Fabricated from Molecular Solution. Langmuir 2018, 34, 8857–8865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladini, G.; Venuti, V.; Almásy, L.; Melone, L.; Crupi, V.; Majolino, D.; Pastori, N.; Fiorati, A.; Punta, C. Cross-linked cellulose nano-sponges: A small angle neutron scattering (SANS) study. Cellulose 2019, 26, 9005–9019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtenay, J.C.; Jin, Y.; Schmitt, J.; Hossain, K.M.Z.; Mahmoudi, N.; Edler, K.J.; Scott, J.L. Salt-Responsive Pickering Emulsions Stabilized by Functionalized Cellulose Nanofibrils. Langmuir 2021, 37, 6864–6873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.-W.; Lal, J.; Huang, Q. Microstructure of β-Lactoglobulin/Pectin Coacervates Studied by Small-Angle Neutron Scattering. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 111, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ways, T.M.M.; Filippov, S.K.; Maji, S.; Glassner, M.; Cegłowski, M.; Hoogenboom, R.; King, S.; Lau, W.M.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V. Mucus-penetrating nanoparticles based on chitosan grafted with various non-ionic polymers: Synthesis, structural characterisation and diffusion studies. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 626, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlachet, I.; Trousil, J.; Rak, D.; Knudsen, K.D.; Pavlova, E.; Nyström, B.; Sosnik, A. Chitosan-graft-poly(methyl methacrylate) amphiphilic nanoparticles: Self-association and physicochemical characterization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 212, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghita Puscaselu, R.; Lobiuc, A.; Dimian, M.; Covasa, M. Alginate: From Food Industry to Biomedical Applications and Management of Metabolic Disorders. Polymers 2020, 12, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depta, P.N.; Gurikov, P.; Schroeter, B.; Forgács, A.; Kalmár, J.; Paul, G.; Marchese, L.; Heinrich, S.; Dosta, M. DEM-Based Approach for the Modeling of Gelation and Its Application to Alginate. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 62, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

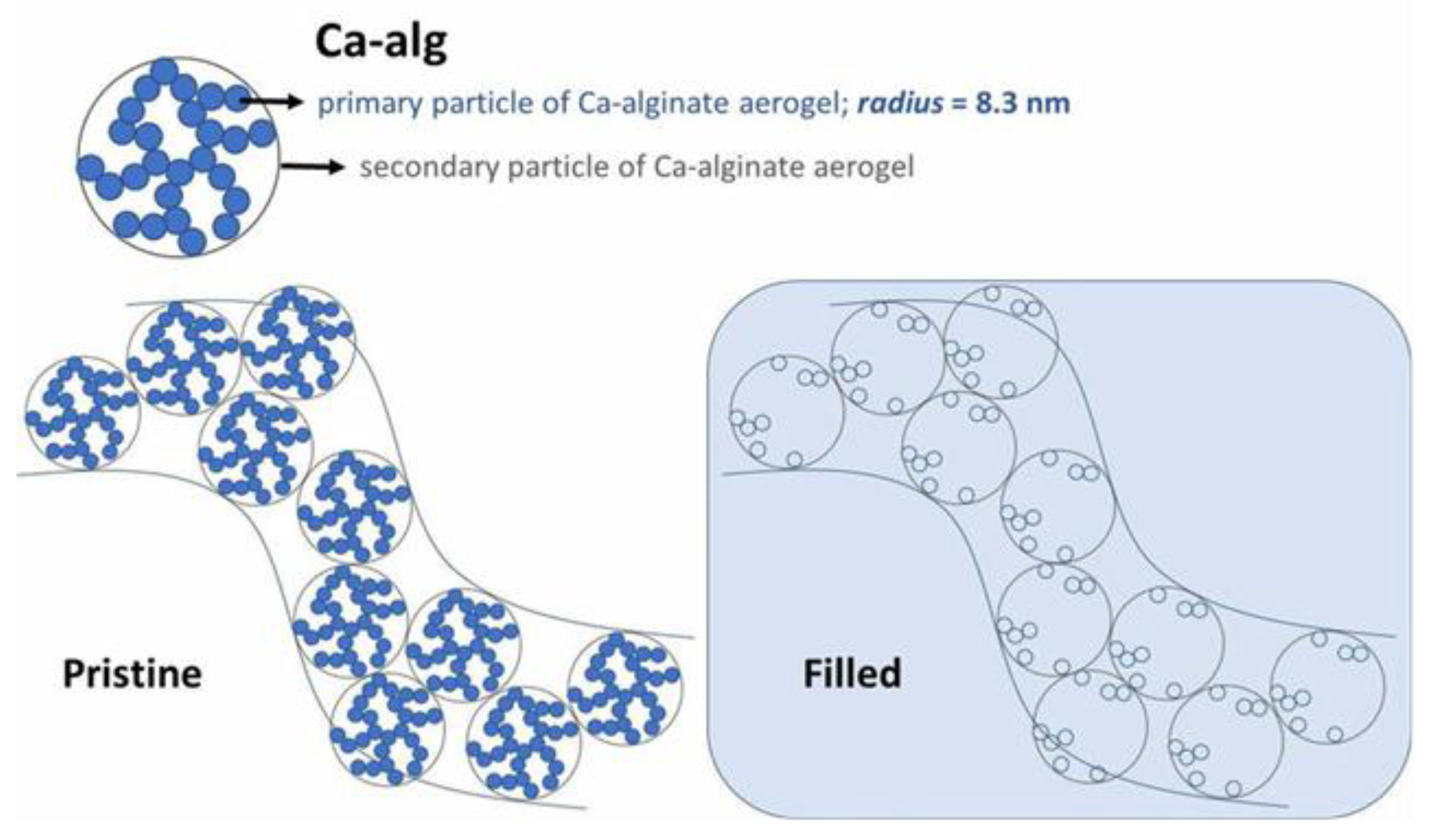

- Forgács, A.; Papp, V.; Paul, G.; Marchese, L.; Len, A.; Dudás, Z.; Fábián, I.; Gurikov, P.; Kalmár, J. Mechanism of Hydration and Hydration Induced Structural Changes of Calcium Alginate Aerogel. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 2997–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevopoulou, P.; Raptopoulos, G.; Len, A.; Dudás, Z.; Fábián, I.; Kalmár, J. Fundamental Skeletal Nanostructure of Nanoporous Polymer-Cross-Linked Alginate Aerogels and Its Relevance to Environmental Remediation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 10575–10583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, L.; Raghuwanshi, V.S.; Tanner, J.; Wu, C.-M.; Kleinerman, O.; Cohen, Y.; Garnier, G. Structure and swelling of cross-linked nanocellulose foams. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 568, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, D.; Zhang, X.; Mao, Y.; Hu, L.; Briber, R.M.; Wang, H. Cellulose Nanocomposites of Cellulose Nanofibers and Molecular Coils. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

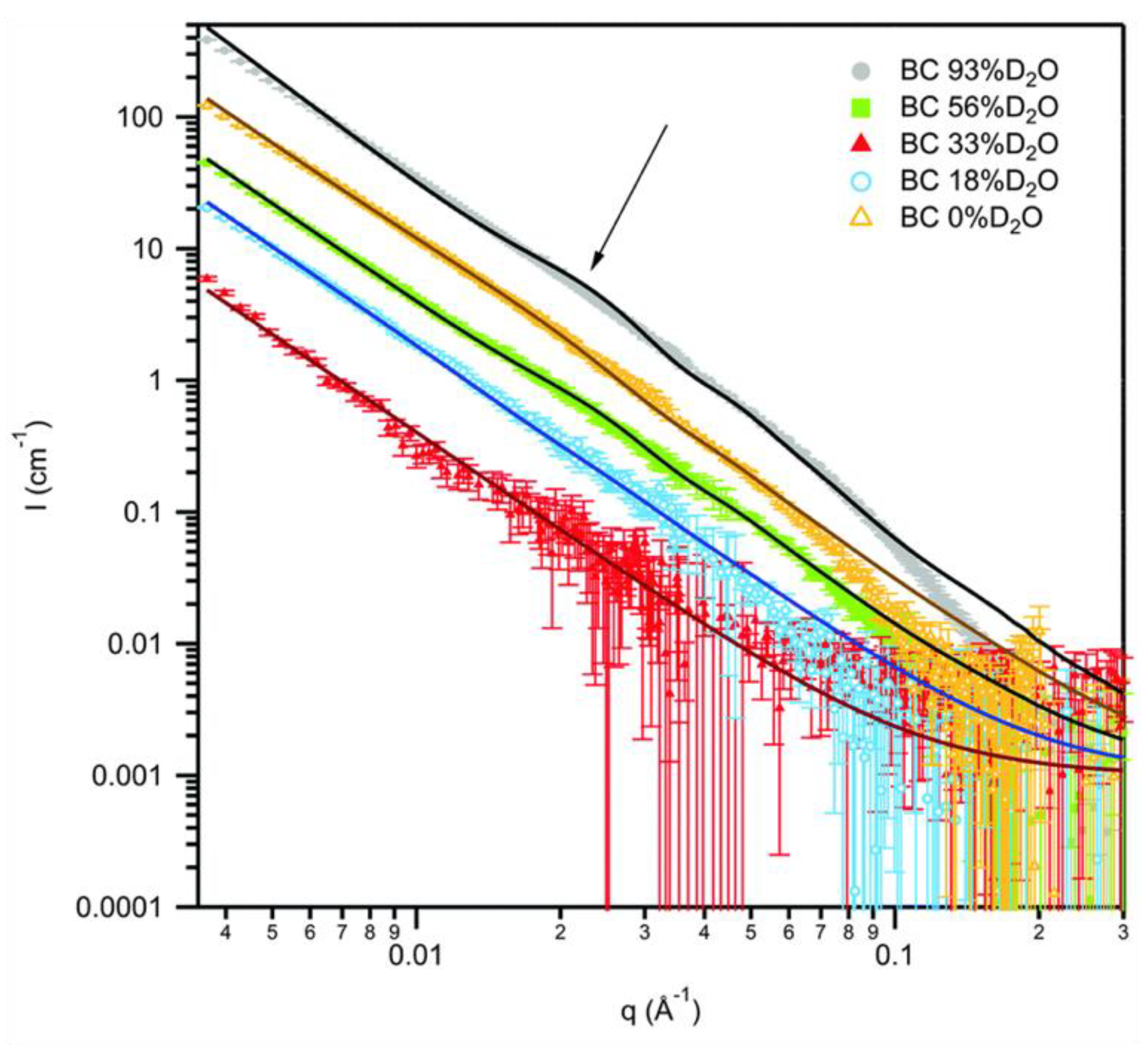

- Penttilä, P.A.; Imai, T.; Sugiyama, J.; Schweins, R. Biomimetic composites of deuterated bacterial cellulose and hemicelluloses studied with small-angle neutron scattering. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 104, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sanz, M.; Gidley, M.J.; Gilbert, E.P. Hierarchical architecture of bacterial cellulose and composite plant cell wall polysaccharide hydrogels using small angle neutron scattering. Soft Matter 2015, 12, 1534–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyslov, R.Y.; Kopitsa, G.P.; Gorshkova, Y.E.; Ezdakova, K.V.; Khripunov, A.K.; Migunova, A.V.; Tsvigun, N.V.; Korzhova, S.A.; Emel’Yanov, A.I.; Pozdnyakov, A.S. Novel biocompatible Cu2+-containing composite hydrogels based on bacterial cellulose and poly-1-vinyl-1,2,4-triazole. Smart Mater. Med. 2022, 3, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Huang, S.; Pingali, S.V.; Sawada, D.; Pu, Y.; Rodriguez, M.; Ragauskas, A.J.; Kim, S.H.; Evans, B.R.; Davison, B.H.; et al. Hemicellulose–Cellulose Composites Reveal Differences in Cellulose Organization after Dilute Acid Pretreatment. Biomacromolecules 2018, 20, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, J.; Calabrese, V.; da Silva, M.A.; Hossain, K.M.Z.; Li, P.; Mahmoudi, N.; Dalgliesh, R.M.; Washington, A.L.; Scott, J.L.; Edler, K.J. Surfactant induced gelation of TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibril dispersions probed using small angle neutron scattering. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 158, 034901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, V.; da Silva, M.A.; Porcar, L.; Bryant, S.J.; Hossain, K.M.Z.; Scott, J.L.; Edler, K.J. Filler size effect in an attractive fibrillated network: A structural and rheological perspective. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 3303–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gicquel, E.; Martin, C.; Gauthier, Q.; Engström, J.; Abbattista, C.; Carlmark, A.; Cranston, E.D.; Jean, B.; Bras, J. Tailoring Rheological Properties of Thermoresponsive Hydrogels through Block Copolymer Adsorption to Cellulose Nanocrystals. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 2545–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majcher, M.J.; Himbert, S.; Vito, F.; Campea, M.A.; Dave, R.; Jensen, G.V.; Rheinstadter, M.C.; Smeets, N.M.B.; Hoare, T. Investigating the Kinetics and Structure of Network Formation in Ultraviolet-Photopolymerizable Starch Nanogel Network Hydrogels via Very Small-Angle Neutron Scattering and Small-Amplitude Oscillatory Shear Rheology. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 7303–7317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.-W.; Hong, Y.-T.; Weigandt, K.M.; Kelley, E.G.; Kong, H.; Rogers, S.A. Strain shifts under stress-controlled oscillatory shearing in theoretical, experimental, and structural perspectives: Application to probing zero-shear viscosity. J. Rheol. 2019, 63, 863–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horkay, F.; Douglas, J.F. Evidence of Many-Body Interactions in the Virial Coefficients of Polyelectrolyte Gels. Gels 2022, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland, S.; Miquelard-Garnier, G.; Shibaev, A.V.; Aleshina, A.L.; Chennevière, A.; Matsarskaia, O.; Sollogoub, C.; Philippova, O.E.; Iliopoulos, I. Dual Transient Networks of Polymer and Micellar Chains: Structure and Viscoelastic Synergy. Polymers 2021, 13, 4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawronski, M.; Conrad, H.; Springer, T.; Stahmann, K.-P. Conformational Changes of the Polysaccharide Cinerean in Different Solvents from Scattering Methods. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 7820–7825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, M.; Yuasa, C.; Hara, K.; Hiramatsu, N.; Nakamura, A.; Hayakawa, Y.; Maeda, Y. Structural change of κ-carrageenan gel near sol-gel transition point. Phys. B Condens. Matter 1997, 241, 999–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischenko, N.; Denef, B.; Mortensen, K.; Reynaers, H. SANS contrast in iota-carrageenan gels and solutions in D2O. Phys. B Condens. Matter 1997, 234, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geonzon, L.C.; Hashimoto, K.; Oda, T.; Matsukawa, S.; Mayumi, K. Elaborating Spatiotemporal Hierarchical Structure of Carrageenan Gels and Their Mixtures during Sol–Gel Transition. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 8676–8687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillo, A.; Fabozzi, A.; Krauss, I.R.; Parrilli, E.; Biggs, C.I.; Gibson, M.I.; Lanzetta, R.; Appavou, M.-S.; Radulescu, A.; Tutino, M.L.; et al. Physicochemical Approach to Understanding the Structure, Conformation, and Activity of Mannan Polysaccharides. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 1445–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, H.; Leite, W.; Zhang, Q.; Bonnesen, P.V.; Labbé, J.L.; Weiss, K.L.; Pingali, S.V.; Hong, K.; Urban, V.S.; et al. Biosynthesis and characterization of deuterated chitosan in filamentous fungus and yeast. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 257, 117637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillo, I.; Morfin, I.; Combet, J. Chain conformation: A key parameter driving clustering or dispersion in polyelectrolyte—Colloid systems. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 561, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibaev, A.V.; Muravlev, D.A.; Skoi, V.V.; Rogachev, A.V.; Kuklin, A.I.; Filippova, O.E. Structure of Interpenetrating Networks of Xanthan Polysaccharide and Wormlike Surfactant Micelles. J. Surf. Investig. X-ray Synchrotron Neutron Tech. 2021, 15, 908–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Sorbo, G.R.; Clemens, D.; Schneck, E.; Hoffmann, I. Stimuli-responsive polyelectrolyte surfactant complexes for the reversible control of solution viscosity. Soft Matter 2022, 18, 2434–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Abdullahi, W.; Dalgliesh, R.; Crossman, M.; Griffiths, P.C. Charge Modification as a Mechanism for Tunable Properties in Polymer–Surfactant Complexes. Polymers 2021, 13, 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajalia, A.I.; Alexandridis, P.; Tsianou, M. Structure of Cellulose Ether Affected by Ionic Surfactant and Solvent: A Small-Angle Neutron Scattering Investigation. Langmuir 2023, 39, 11529–11544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhan, C.; Geng, L.; Chu, B.; Hsiao, B.S. Characterization of Nanocellulose Using Small-Angle Neutron, X-ray, and Dynamic Light Scattering Techniques. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zou, D.; Zhai, S.; Yan, Y.; Yang, H.; He, C.; Ke, Y.; Singh, S.; Cheng, G. Enhancing the interaction between cellulose and dilute aqueous ionic liquid solutions and its implication to ionic liquid recycling and reuse. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 277, 118848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Foston, M.B.; O’neill, H.; Urban, V.S.; Ragauskas, A.; Evans, B.R.; Davison, B.H.; Pingali, S.V. Structural Reorganization of Noncellulosic Polymers Observed in Situ during Dilute Acid Pretreatment by Small-Angle Neutron Scattering. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuwanshi, V.S.; Cohen, Y.; Garnier, G.; Garvey, C.J.; Garnier, G. Deuterated Bacterial Cellulose Dissolution in Ionic Liquids. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 6982–6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemansi; Gupta, R.; Aswal, V.K.; Saini, J.K. Sequential dilute acid and alkali deconstruction of sugarcane bagasse for improved hydrolysis: Insight from small angle neutron scattering (SANS). Renew. Energy 2020, 147, 2091–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhao, W.; Wang, S.; Yu, C.; Singh, S.; Simmons, B.; Cheng, G. Dimethyl sulfoxide assisted dissolution of cellulose in 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazoium acetate: Small angle neutron scattering and rheological studies. Cellulose 2019, 26, 2243–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, S.; Zhao, Y.; Putra, A. Hierarchical structure of microbial cellulose and marvelous water uptake, investigated by combining neutron scattering instruments at research reactor JRR-3, Tokai. Polymer 2019, 176, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuwanshi, V.S.; Cohen, Y.; Garnier, G.; Garvey, C.J.; Russell, R.A.; Darwish, T.; Garnier, G. Cellulose Dissolution in Ionic Liquid: Ion Binding Revealed by Neutron Scattering. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 7649–7655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gilbert, E.P.; Qiao, D.; Xie, F.; Wang, D.K.; Zhao, S.; Jiang, F. A further study on supramolecular structure changes of waxy maize starch subjected to alkaline treatment by extended-q small-angle neutron scattering. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 95, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.G.; Colby, R.H.; Cabral, J.T. Electrostatic and Hydrophobic Interactions in NaCMC Aqueous Solutions: Effect of Degree of Substitution. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 3165–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rie, J.; Schütz, C.; Gençer, A.; Lombardo, S.; Gasser, U.; Kumar, S.; Salazar-Alvarez, G.; Kang, K.; Thielemans, W. Anisotropic Diffusion and Phase Behavior of Cellulose Nanocrystal Suspensions. Langmuir 2019, 35, 2289–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; McMillan, M.F.; Davis, V.A.; Kitchens, C.L. Phase Behavior of Acetylated Cellulose Nanocrystals and Origins of the Cross-Hatch Birefringent Texture. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 3435–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Bleuel, M.; Lyu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Henderson, D.; Wang, H.; Briber, R.M. Phase Separation and Stack Alignment in Aqueous Cellulose Nanocrystal Suspension under Weak Magnetic Field. Langmuir 2018, 34, 8042–8051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharratt, W.N.; O’Connell, R.; Rogers, S.E.; Lopez, C.G.; Cabral, J.T. Conformation and Phase Behavior of Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose in the Presence of Mono- and Divalent Salts. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 1451–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penttilä, P.A.; Zitting, A.; Lourençon, T.; Altgen, M.; Schweins, R.; Rautkari, L. Water-accessibility of interfibrillar spaces in spruce wood cell walls. Cellulose 2021, 28, 11231–11245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitting, A.; Paajanen, A.; Rautkari, L.; Penttilä, P.A. Deswelling of microfibril bundles in drying wood studied by small-angle neutron scattering and molecular dynamics. Cellulose 2021, 28, 10765–10776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.H.; Altaner, C.M.; Forsyth, V.T.; Mossou, E.; Kennedy, C.J.; Martel, A.; Jarvis, M.C. Nanostructural deformation of high-stiffness spruce wood under tension. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Sanchez, P.; Martinez-Sanz, M.; Bonilla, M.; Sonni, F.; Gilbert, E.; Gidley, M. Nanostructure and poroviscoelasticity in cell wall materials from onion, carrot and apple: Roles of pectin. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 98, 105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sanz, M.; Mikkelsen, D.; Flanagan, B.; Gidley, M.J.; Gilbert, E.P. Multi-scale model for the hierarchical architecture of native cellulose hydrogels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 147, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Chen, S.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, H. Functionalized bacterial cellulose derivatives and nanocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 1043–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghvami-Panah, M.; Ameli, A. MXene/Cellulose composites as electromagnetic interference shields: Relationships between microstructural design and shielding performance. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 176, 107879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Wang, B.; Ni, Y. Chitosan-Nanocellulose Composites for Regenerative Medicine Applications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 4584–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, Y.; Nishiyama, Y.; Pingali, S.V.; O’neill, H.M.; Zhang, Q.; Berglund, L.A. Small Angle Neutron Scattering Shows Nanoscale PMMA Distribution in Transparent Wood Biocomposites. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 2883–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardyani, T.; Mohamed, A.; Abu Bakar, S.; Sagisaka, M.; Umetsu, Y.; Mamat, M.H.; Ahmad, M.K.; Khalil, H.A.; King, S.M.; Rogers, S.E.; et al. Electrochemical exfoliation of graphite in nanofibrillated kenaf cellulose (NFC)/surfactant mixture for the development of conductive paper. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 228, 115376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielbauer, B.I.; Jackson, A.J.; Maurer, S.; Waschatko, G.; Ghebremedhin, M.; Rogers, S.E.; Heenan, R.K.; Porcar, L.; Vilgis, T.A. Soybean oleosomes studied by small angle neutron scattering (SANS). J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 529, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Rajan, K.; Annamraju, A.; Chmely, S.C.; Pingali, S.V.; Carrier, D.J.; Labbé, N. A Sequential Autohydrolysis-Ionic Liquid Fractionation Process for High Quality Lignin Production. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 2293–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penttilä, P.A.; Altgen, M.; Awais, M.; Österberg, M.; Rautkari, L.; Schweins, R. Bundling of cellulose microfibrils in native and polyethylene glycol-containing wood cell walls revealed by small-angle neutron scattering. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, R.; Bhagia, S.; Keum, J.K.; Pingali, S.V.; Ragauskas, A.J.; Davison, B.H.; O’Neill, H. Structural Insights into Low and High Recalcitrance Natural Poplar Variants Using Neutron and X-ray Scattering. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 13838–13849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.H.; Martel, A.; Grillo, I.; Jarvis, M.C. Hemicellulose binding and the spacing of cellulose microfibrils in spruce wood. Cellulose 2020, 27, 4249–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, D.; Kalluri, U.C.; O’neill, H.; Urban, V.; Langan, P.; Davison, B.; Pingali, S.V. Tension wood structure and morphology conducive for better enzymatic digestion. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, J.; Ray, D.; Aswal, V.K.; Deshpande, A.P.; Varughese, S. Pectin self-assembly and its disruption by water: Insights into plant cell wall mechanics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 22691–22698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Sen, D.; Thakre, S.; Kumaraswamy, G. Characterizing Microvoids in Regenerated Cellulose Fibers Obtained from Viscose and Lyocell Processes. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 3987–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Atomic Nucleus | bcoh [× 10−13 cm] | bincoh [× 10−13 cm] | scoh [× 10−24 cm2] | sinc [× 10−24 cm2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H | −3.74 | 25.27 | 1.758 | 80.27 |

| 2H (D) | 6.67 | 4.04 | 5.592 | 2.05 |

| 12C | 6.65 | 0.0 | 5.550 | 0.00 |

| 14N | 9.37 | 2.00 | 11.01 | 0.50 |

| 16O | 5.80 | 0.00 | 4.232 | 0.00 |

| 31P | 5.13 | 0.20 | 3.307 | 0.005 |

| 32S | 2.80 | 0.00 | 0.988 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fanova, A.; Sotiropoulos, K.; Radulescu, A.; Papagiannopoulos, A. Advances in Small Angle Neutron Scattering on Polysaccharide Materials. Polymers 2024, 16, 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16040490

Fanova A, Sotiropoulos K, Radulescu A, Papagiannopoulos A. Advances in Small Angle Neutron Scattering on Polysaccharide Materials. Polymers. 2024; 16(4):490. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16040490

Chicago/Turabian StyleFanova, Anastasiia, Konstantinos Sotiropoulos, Aurel Radulescu, and Aristeidis Papagiannopoulos. 2024. "Advances in Small Angle Neutron Scattering on Polysaccharide Materials" Polymers 16, no. 4: 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16040490

APA StyleFanova, A., Sotiropoulos, K., Radulescu, A., & Papagiannopoulos, A. (2024). Advances in Small Angle Neutron Scattering on Polysaccharide Materials. Polymers, 16(4), 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16040490