Physicochemical and Mechanical Properties of Non-Isocyanate Polyhydroxyurethanes (NIPHUs) from Epoxidized Soybean Oil: Candidates for Wound Dressing Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

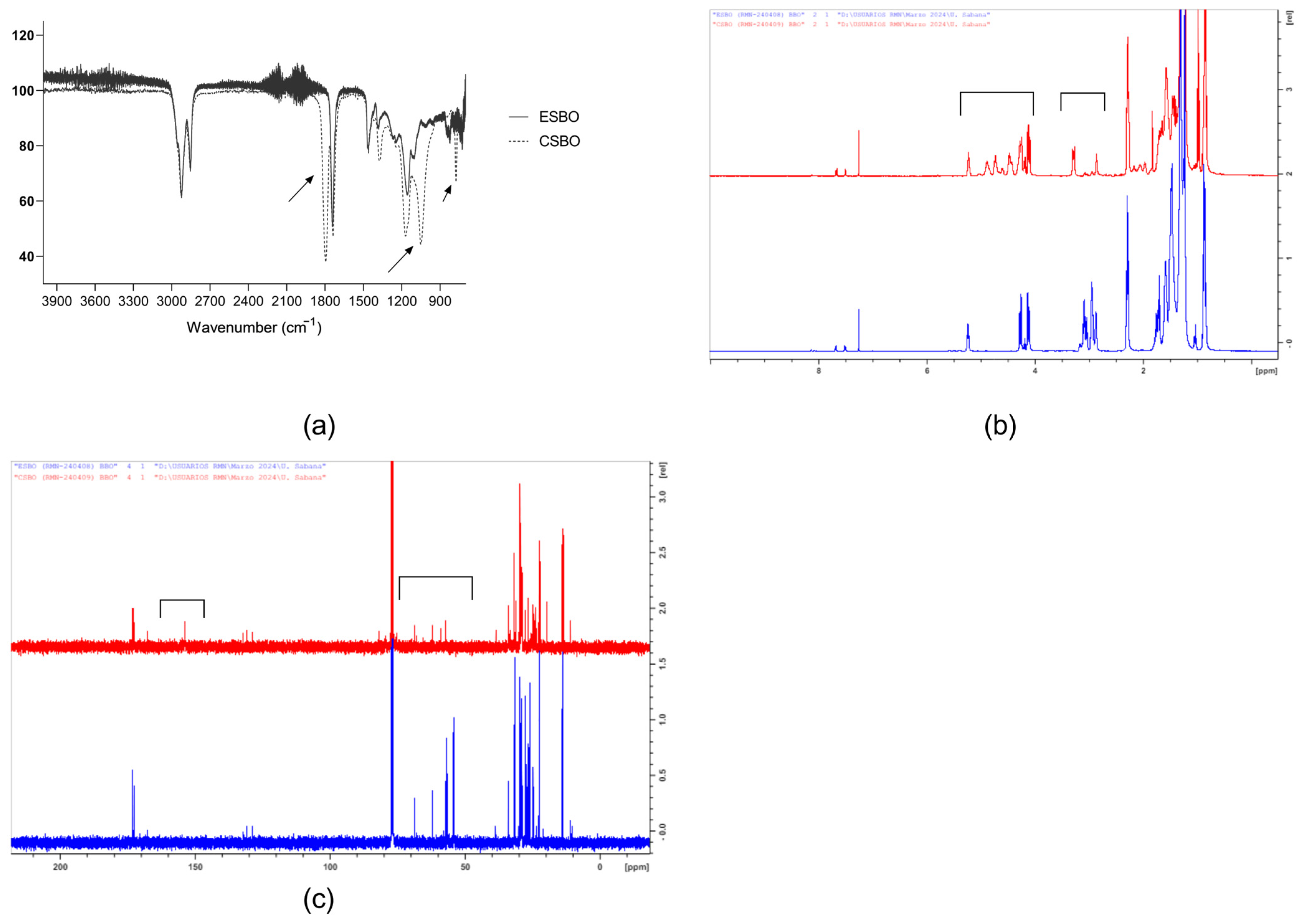

2.2. Soybean Oil Carbonatation

2.3. Synthesis of Non-Isocyanate Polyhydroxyurethanes (NIPHUs)

2.4. Characterization

2.5. Swelling

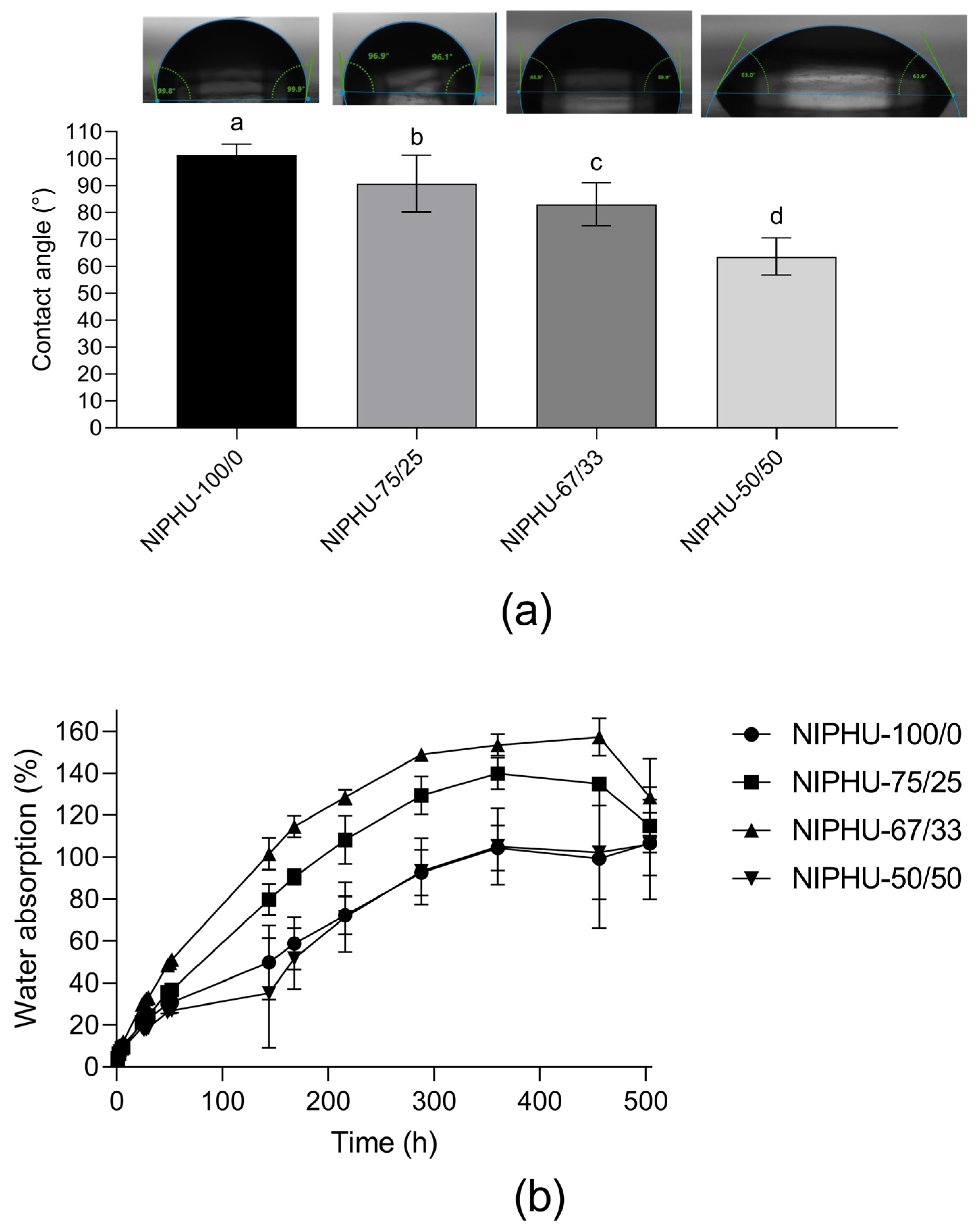

2.6. Contact Angle

2.7. Hydrolytic and Oxidative Degradation

2.8. Mechanical Test

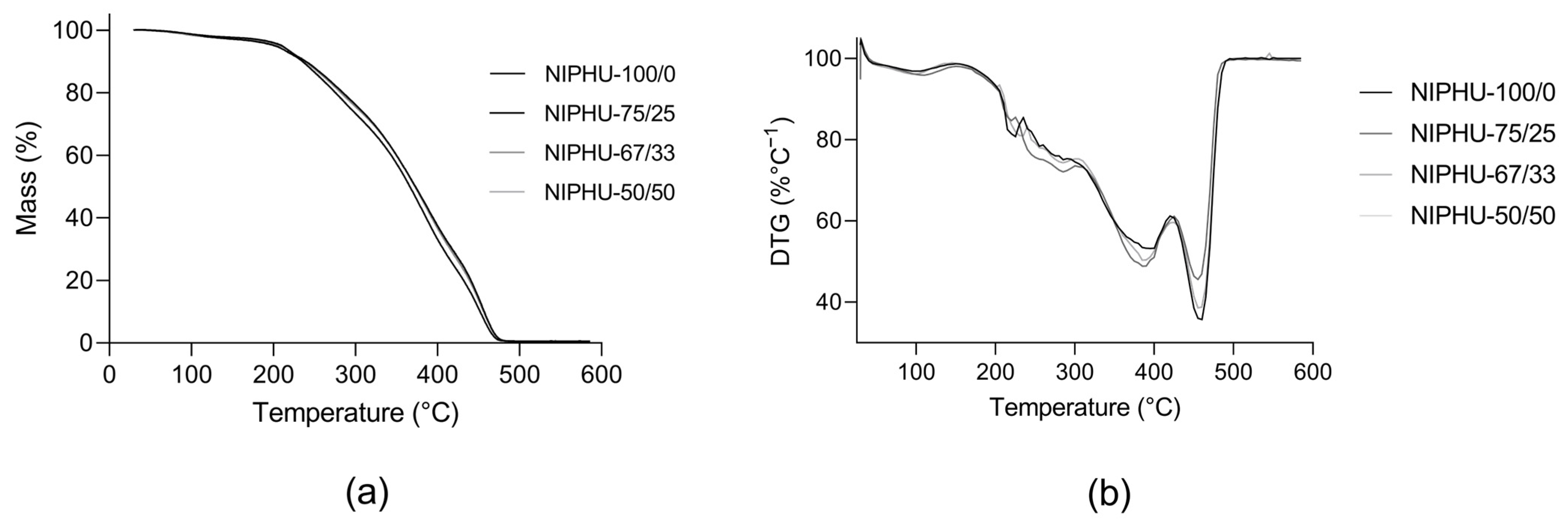

2.9. Thermal Characterization

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wendels, S.; Avérous, L. Biobased Polyurethanes for Biomedical Applications. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 1083–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostev, A.A.; Karpenko, A.A.; Laktionov, P.P. Polyurethanes in Cardiovascular Prosthetics. Polym. Bull. 2018, 75, 4311–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, C.; Malek, F.; Manseri, A.; Caillol, S.; Negrell, C. Reactive Jojoba and Castor Oils-Based Cyclic Carbonates for Biobased Polyhydroxyurethanes. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 113, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennen, S.; Grignard, B.; Thomassin, J.M.; Gilbert, B.; Vertruyen, B.; Jerome, C.; Detrembleur, C. Polyhydroxyurethane Hydrogels: Synthesis and Characterizations. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 84, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayon, I.; Szarlej, P.; Gnatowski, P.; Piłat, E.; Sienkiewicz, M.; Glinka, M.; Karczewski, J.; Kucińska-Lipka, J. Polyurethane Based Hybrid Ciprofloxacin-Releasing Wound Dressings Designed for Skin Engineering Purpose. Adv. Med. Sci. 2022, 67, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholami, H.; Yeganeh, H. Vegetable Oil-Based Polyurethanes as Antimicrobial Wound Dressings: In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 15, 045001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.M.; Huang, Y.F.; Dai, J.J.; Shi, X.A.; Zheng, Y.Q. A Sandwich Structure Composite Wound Dressing with Firmly Anchored Silver Nanoparticles for Severe Burn Wound Healing in a Porcine Model. Regen. Biomater. 2021, 8, rbab037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurano, R.; Boffito, M.; Ciardelli, G.; Chiono, V. Wound Dressing Products: A Translational Investigation from the Bench to the Market. Eng. Regen. 2022, 3, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaz, M.; Maqsood, S.; Gull, N.; Tabish, T.A.; Zia, S.; Ullah, R.; Muhammad, S.; Arif, M. Polymer-Based Biomaterials for Chronic Wound Management: Promises and Challenges. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 598, 120270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, X.; Yu, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Wu, S. Electrospun Polyasparthydrazide Nanofibrous Hydrogel Loading with In-Situ Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles for Full-Thickness Skin Wound Healing Application. Mater. Des. 2024, 239, 112818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samatya Yılmaz, S.; Aytac, A. The Highly Absorbent Polyurethane/Polylactic Acid Blend Electrospun Tissue Scaffold for Dermal Wound Dressing. Polym. Bull. 2023, 80, 12787–12813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, M.A.C.M.; Munawar, K.; Ching, Y.C.; Illias, H.A.; Chuah, C.H. Bio-Based Poly(Hydroxy Urethane)s: Synthesis and Pre/Post-Functionalization. Chem. Asian J. 2021, 16, 1281–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carré, C.; Ecochard, Y.; Caillol, S.; Avérous, L. From the Synthesis of Biobased Cyclic Carbonate to Polyhydroxyurethanes: A Promising Route towards Renewable Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 3410–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubofu, E.B. Castor Oil as a Potential Renewable Resource for the Production of Functional Materials. Sustain. Chem. Process. 2016, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Huang, Z.; Huang, X.; Xu, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, D.; Shang, S. Preparation of Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes from Epoxy Soybean Oil: Dual Dynamic Networks to Realize Self-Healing and Reprocessing under Mild Conditions. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 6349–6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, H.; Yeganeh, H. Soybean Oil-Derived Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes Containing Azetidinium Groups as Antibacterial Wound Dressing Membranes. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 142, 110142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, A.F.; Echeverri, D.A.; Rios, L.A. Carbonation of Epoxidized Castor Oil: A New Bio-Based Building Block for the Chemical Industry. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2017, 92, 1104–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raden Siti Amirah, H.; Ahmad Faiza, M.; Samsuri, A. Synthesis and Characterization of Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane from Epoxidized Linoleic Acid—A Preliminary Study. Adv. Mat. Res. 2013, 812, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uscátegui, Y.L.; Díaz, L.E.; Valero, M.F. In Vitro and in Vivo Biocompatibility of Polyurethanes Synthesized with Castor Oil Polyols for Biomedical Devices. J. Mater. Res. 2019, 34, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, H.Y.; Jing, X.; Hagerty, B.S.; Chen, G.; Huang, A.; Turng, L.S. Post-Crosslinkable Biodegradable Thermoplastic Polyurethanes: Synthesis, and Thermal, Mechanical, and Degradation Properties. Mater. Des. 2017, 127, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weems, A.C.; Wacker, K.T.; Carrow, J.K.; Boyle, A.J.; Maitland, D.J. Shape Memory Polyurethanes with Oxidation-Induced Degradation: In Vivo and in Vitro Correlations for Endovascular Material Applications. Acta Biomater. 2017, 59, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D638-10; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Ahmad, Z.R.; Mahanwar, P.A. Synthesis and Properties of Foams from a Blend of Vegetable Oil Based Polyhydroxyurethane and Epoxy Resin. Cell. Polym. 2022, 41, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Deng, H.; Li, N.; Xie, F.; Shi, H.; Wu, M.; Zhang, C. Mechanically Strong Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane Thermosets from Cyclic Carbonate Linseed Oil. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 8355–8366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Zubir, S.; Mat Saad, N.; Harun, F.W.; Ali, E.S.; Ahmad, S. Incorporation of Palm Oil Polyol in Shape Memory Polyurethane: Implication for Development of Cardiovascular Stent. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2018, 29, 2926–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffa, J.M.; Mondragon, G.; Corcuera, M.A.; Eceiza, A.; Mucci, V.; Aranguren, M.I. Physical and Mechanical Properties of a Vegetable Oil Based Nanocomposite. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 98, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, P.; Chhabra, R.; Muke, S.; Narvekar, A.; Sathaye, S.; Jain, R.; Dandekar, P. Fabrication and Characterization of Starch-TPU Based Nanofibers for Wound Healing Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 119, 111316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; de Souza, F.M.; Gupta, R.K. Study of Soybean Oil-Based Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane Films via a Solvent and Catalyst-Free Approach. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 5862–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Chen, X.; Torkelson, J.M. Isocyanate-Free, Thermoplastic Polyhydroxyurethane Elastomers Designed for Cold Temperatures: Influence of PDMS Soft-Segment Chain Length and Hard-Segment Content. Polymer 2022, 256, 125251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasian, A.; Najafi, F.; Eftekhari, M.; Ardekani, M.R.S.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Khanavi, M. Polyurethane/Carboxymethylcellulose Nanofibers Containing Malva Sylvestris Extract for Healing Diabetic Wounds: Preparation, Characterization, in Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 114, 111039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornille, A.; Serres, J.; Michaud, G.; Simon, F.; Fouquay, S.; Boutevin, B.; Caillol, S. Syntheses of Epoxyurethane Polymers from Isocyanate Free Oligo-Polyhydroxyurethane. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 75, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uscategui, Y.L.; Diaz, L.E.; Gomez-Tejedor, J.A.; Valles-Lluch, A.; Vilarino-Feltrer, G.; Serrano, M.A.; Valero, M.F.; Uscátegui, Y.L.; Díaz, L.E.; Gómez-Tejedor, J.A.; et al. Candidate Polyurethanes Based on Castor Oil (Ricinus Communis), with Polycaprolactone Diol and Chitosan Additions, for Use in Biomedical Applications. Molecules 2019, 24, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ID Sample | BDA (% Molar) | CHM (% Molar) |

|---|---|---|

| NIPHU-100/0 | 100 | 0 |

| NIPHU-75/25 | 75 | 25 |

| NIPHU-67/33 | 67 | 33 |

| NIPHU-50/50 | 50 | 50 |

| NIPHU-33/67 | 33 | 67 |

| NIPHU-25/75 | 25 | 75 |

| NIPHU-0/100 | 0 | 100 |

| Sample | Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIPHU-100 | 0.009 ± 0.002 a | 0.97 ± 0.16 a | 81.13 ±18.82 a |

| NIPHU-75/25 | 0.006 ± 0.001 a,b | 1.13 ± 0.05 a | 145.89 ± 39.69 a,b |

| NIPHU-67/33 | 0.002 ± 0.001 b | 0.49 ± 0.22 a | 207.65 ± 31.05 b,c |

| NIPHU-50/50 | 0.003 ± 0.0005 b,c | 0.96 ± 0.07 a | 273.21 ± 17.62 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morales-González, M.; Valero, M.F.; Díaz, L.E. Physicochemical and Mechanical Properties of Non-Isocyanate Polyhydroxyurethanes (NIPHUs) from Epoxidized Soybean Oil: Candidates for Wound Dressing Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16111514

Morales-González M, Valero MF, Díaz LE. Physicochemical and Mechanical Properties of Non-Isocyanate Polyhydroxyurethanes (NIPHUs) from Epoxidized Soybean Oil: Candidates for Wound Dressing Applications. Polymers. 2024; 16(11):1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16111514

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorales-González, Maria, Manuel F. Valero, and Luis E. Díaz. 2024. "Physicochemical and Mechanical Properties of Non-Isocyanate Polyhydroxyurethanes (NIPHUs) from Epoxidized Soybean Oil: Candidates for Wound Dressing Applications" Polymers 16, no. 11: 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16111514

APA StyleMorales-González, M., Valero, M. F., & Díaz, L. E. (2024). Physicochemical and Mechanical Properties of Non-Isocyanate Polyhydroxyurethanes (NIPHUs) from Epoxidized Soybean Oil: Candidates for Wound Dressing Applications. Polymers, 16(11), 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16111514