Magnetic Template Anion Polyacrylamide–Polydopamine-Fe3O4 Combined with Ultraviolet/H2O2 for the Rapid Enrichment and Degradation of Diclofenac Sodium from Aqueous Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

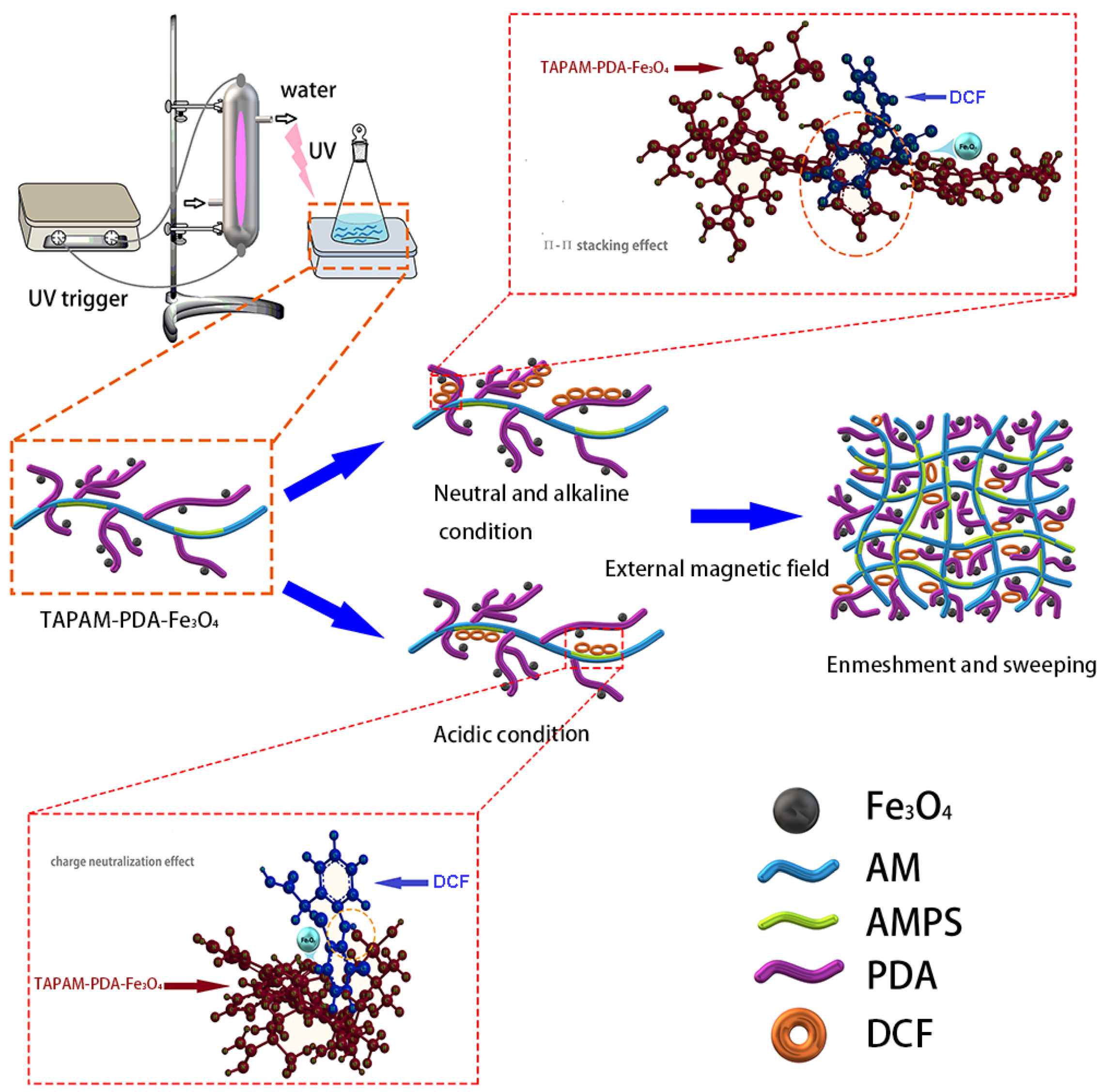

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. TAPAM-PDA-Fe3O4 Synthesis Optimization

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.4. Enrichment Experiments

2.5. Degradation Experiments

2.6. Stability and Regeneration of TAPAM-PDA-Fe3O4

3. Results and Discussion

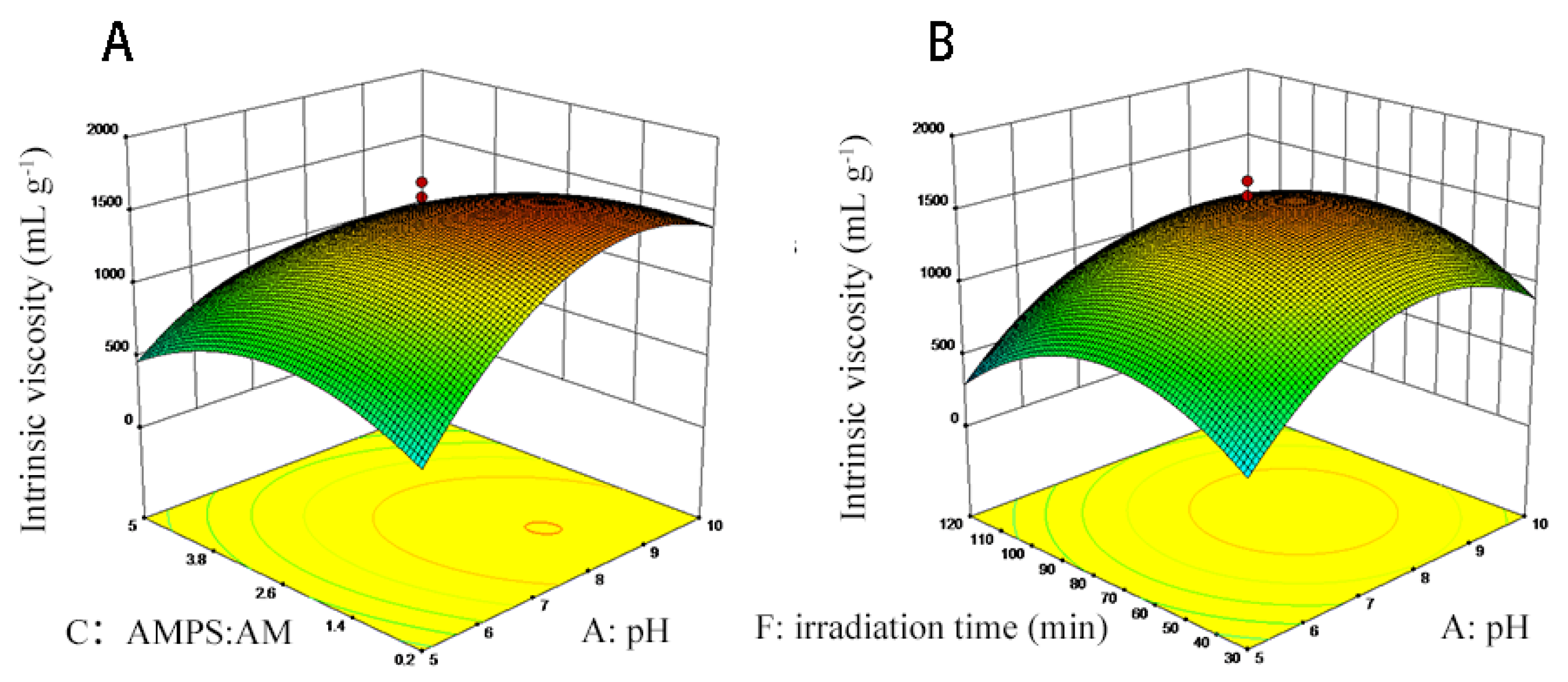

3.1. TAPAM-PDA-Fe3O4 Synthesis Optimization

3.2. Characterization of Magnetic Flocculant

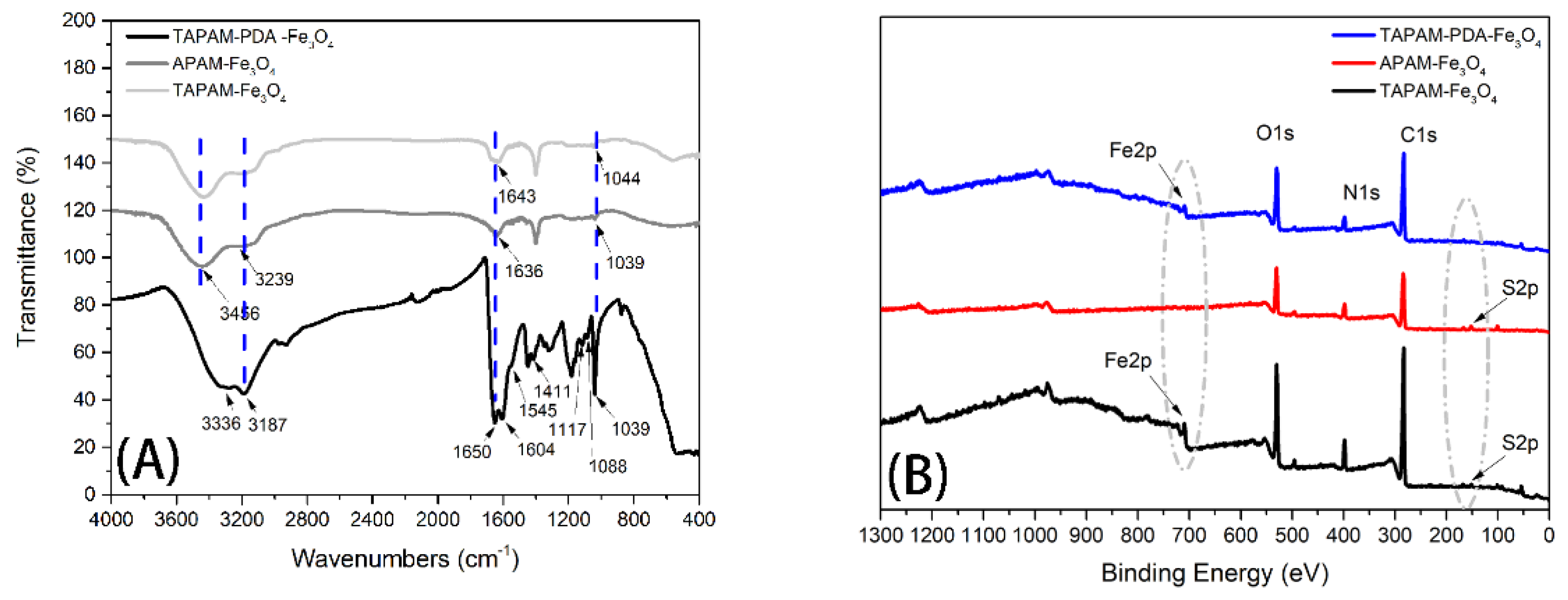

3.2.1. FT-IR and XPS Spectral Analysis

3.2.2. TGA-DSC Analysis

3.2.3. Morphological Analysis

3.2.4. XRD Patterns

3.2.5. Magnetic Properties

3.3. Enrichment Properties

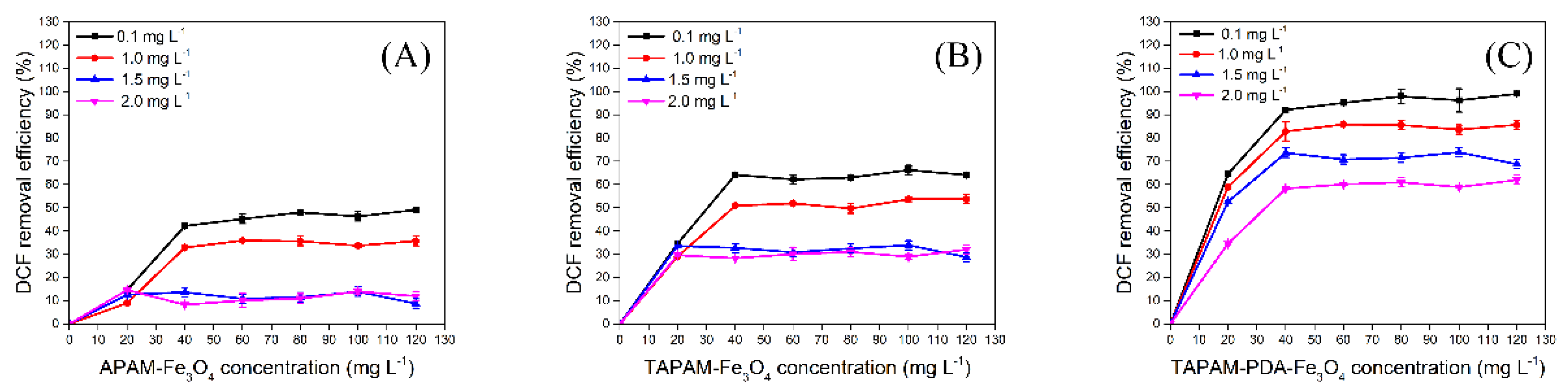

3.3.1. DCFS Initial Concentration Effect

3.3.2. DCFS Initial pH Effect

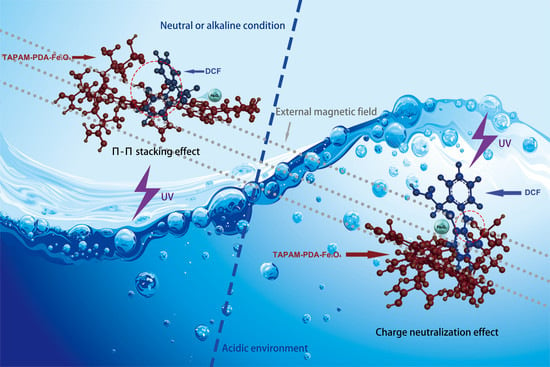

3.3.3. Enrichment Mechanism Analysis

3.3.4. DCFS Enrichment Kinetics Analysis

3.3.5. DCFS Enrichment Isotherms Analysis

3.4. Degradation Performance

3.5. Stability and Regeneration of TAPAM-PDA-Fe3O4

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fontes, M.K.; Gusso-Choueri, P.K.; Maranho, L.A.; Abessa, D.M.S.; Mazur, W.A.; de Campos, B.G.; Guimaraes, L.L.; de Toledo, M.S.; Lebre, D.; Marques, J.R.; et al. A tiered approach to assess effects of diclofenac sodium on the brown mussel Perna perna: A contribution to characterize the hazard. Water Res. 2018, 132, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villar-Navarro, E.; Baena-Nogueras, R.M.; Paniw, M.; Perales, J.A.; Lara-Martin, P.A. Removal of pharmaceuticals in urban wastewater: High rate algae pond (HRAP) based technologies as an alternative to activated sludge based processes. Water Res. 2018, 139, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banaschik, R.; Jablonowski, H.; Bednarski, P.J.; Kolb, J.F. Degradation and intermediates of diclofenac sodium as instructive example for decomposition of recalcitrant pharmaceuticals by hydroxyl radicals generated with pulsed corona plasma in water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 342, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, L.; Meric, S.; Kassinos, D.; Guida, M.; Russo, F.; Belgiorno, V. Degradation of diclofenac sodium by TiO2 photocatalysis: UV absorbance kinetics and process evaluation through a set of toxicity bioassays. Water Res. 2009, 43, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landry, K.A.; Sun, P.; Huang, C.H.; Boyer, T.H. Ion-exchange selectivity of diclofenac sodium, ibuprofen, ketoprofen, and naproxen in ureolyzed human urine. Water Res. 2015, 68, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Nie, E.; Xu, J.; Yan, S.; Cooper, W.J.; Song, W. Degradation of diclofenac sodium by advanced oxidation and reduction processes: Kinetic studies, degradation pathways and toxicity assessments. Water Res. 2013, 47, 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrez, I.; Carballa, M.; Verbeken, K.; Vanhaecke, L.; Ternes, T.; Boon, N.; Verstraete, W. Diclofenac sodium oxidation by biogenic manganese oxides. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3449–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Yuan, X.; Wang, H.; Wu, Z.; Jiang, L.; Leng, L.; Xi, K.; Cao, X.; Zeng, G. Highly efficient removal of diclofenac sodium sodium from medical wastewater by Mg/Al layered double hydroxide-poly(m-phenylenediamine) composite. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 366, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteagudo, J.M.; El-Taliawy, H.; Duran, A.; Caro, G.; Bester, K. Sono-activated persulfate oxidation of diclofenac sodium: Degradation, kinetics, pathway and contribution of the different radicals involved. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 357, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avetta, P.; Fabbri, D.; Minella, M.; Brigante, M.; Maurino, V.; Minero, C.; Pazzi, M.; Vione, D. Assessing the phototransformation of diclofenac sodium, clofibric acid and naproxen in surface waters: Model predictions and comparison with field data. Water Res. 2016, 105, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plakas, K.V.; Sklari, S.D.; Yiankakis, D.A.; Sideropoulos, G.T.; Zaspalis, V.T.; Karabelas, A.J. Removal of organic micropollutants from drinking water by a novel electro-Fenton filter: Pilot-scale studies. Water Res. 2016, 91, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Corte, S.; Sabbe, T.; Hennebel, T.; Vanhaecke, L.; De Gusseme, B.; Verstraete, W.; Boon, N. Doping of biogenic Pd catalysts with Au enables dechlorination of diclofenac sodium at environmental conditions. Water Res. 2012, 46, 2718–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Deng, S.; Huang, Q.; Nie, Y.; Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Yu, G. Regenerable granular carbon nanotubes/alumina hybrid adsorbents for diclofenac sodium sodium and carbamazepine removal from aqueous solution. Water Res. 2013, 47, 4139–4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.; Huang, H.; Jiang, R.; Wang, N.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.G.; Ouyang, X.K. Adsorption of diclofenac sodium sodium on bilayer amino-functionalized cellulose nanocrystals/chitosan composite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 369, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espina de Franco, M.A.; de Carvalho, C.B.; Bonetto, M.M.; Soares, R.d.P.; Feris, L.A. Diclofenac sodium removal from water by adsorption using activated carbon in batch mode and fixed-bed column: Isotherms, thermodynamic study and breakthrough curves modeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, X.; Hu, X.; An, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, C. Dual Polydopamine-Anion Polyacrylamide Polymer System for Improved Removal of Nickel Ions and Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solution. Sci. Adv. Mater. 2019, 11, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhang, X.; Luan, Y.; Wang, R.; Liu, H.; Li, D.; Hu, L. Using gamma-Ray Polymerization-Induced Assemblies to Synthesize Polydopamine Nanocapsules. Polymers 2019, 11, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Kim, J.F.; Ignacz, G.; Pogany, P.; Lee, Y.M.; Szekely, G. Bio-Inspired Robust Membranes Nanoengineered from Interpenetrating Polymer Networks of Polybenzimidazole/Polydopamine. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.H.; Messersmith, P.B.; Lee, H. Polydopamine Surface Chemistry: A Decade of Discovery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 7523–7540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Xing, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Cai, K. Nanoscale Polydopamine (PDA) Meets pi-pi Interactions: An Interface-Directed Coassembly Approach for Mesoporous Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2016, 32, 12119–12128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iregui, A.; Irusta, L.; Martin, L.; Gonzalez, A. Analysis of the Process Parameters for Obtaining a Stable Electrospun Process in Different Composition Epoxy/Poly epsilon-Caprolactone Blends with Shape Memory Properties. Polymers 2019, 11, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szekely, G.; Henriques, B.; Gil, M.; Alvarez, C. Experimental design for the optimization and robustness testing of a liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method for the trace analysis of the potentially genotoxic 1,3-diisopropylurea. Drug Test. Anal. 2014, 6, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapur, M.; Gupta, R.; Mondal, M.K. Parametric Optimization of Cu (II) and Ni (II) Adsorption onto Coal Dust and Magnetized Sawdust Using Box-Behnken Design of Experiments. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2016, 35, 1597–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Qi, X.; Rosenholm, J.M.; Cai, K. Polydopamine Coatings in Confined Nanopore Space: Toward Improved Retention and Release of Hydrophilic Cargo. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 24512–24521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veisi, H.; Safarimehr, P.; Hemmati, S. Oxo-vanadium immobilized on polydopamine coated-magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4): A heterogeneous nanocatalyst for selective oxidation of sulfides and benzylic alcohols with H2O2. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2018, 88, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Ma, J.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Sun, Y.; Tang, X. Synthesis of anion polyacrylamide under UV initiation and its application in removing dioctyl phthalate from water through flocculation process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 123, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.L.; Hamaya, T.; Okada, T. Chemically modified poly(vinyl alcohol)-poly(2-acrylamido-2-methyl-1-propanesulfonic acid) as a novel proton-conducting fuel cell membrane. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 2413–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Zheng, H.; Sun, Q.; Zheng, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, R. A novel floating adsorbents system of acid orange 7 removal: Polymer grafting effect. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 227, 115677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Chen, B. Adsorption of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons by Graphene and Graphene Oxide Nanosheets. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 4817–4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.L.; Gao, B.Y.; Li, C.X.; Yue, Q.Y.; Liu, B. Synthesis and characterization of hydrophobically associating cationic polyacrylamide. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 161, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zheng, H.; Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B.; Djibrine, B.Z. Improvement of Sludge Dewaterability by Ultrasound-Initiated Cationic Polyacrylamide with Microblock Structure: The Role of Surface-Active Monomers. Materials 2017, 10, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.X.; Zhang, J.X.; Chen, F.; Liu, J.J.; Cai, K.Y. Mesoporous polydopamine nanoparticles with co-delivery function for overcoming multidrug resistance via synergistic chemo-photothermal therapy. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 8781–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Zheng, H.L.; Gao, B.Y.; Zhang, S.X.; Zhao, C.L.; Zhou, Y.H.; Xu, B.C. Fabricating an anionic polyacrylamide (APAM) with an anionic block structure for high turbidity water separation and purification. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 28918–28930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.Z.; Zheng, H.L.; Deng, X.R.; Xu, B.C.; Sun, Y.J.; Liu, Y.Z.; Liang, J.J. Formation of cationic hydrophobic micro-blocks in P(AM-DMC) by template assembly: Characterization and application in sludge dewatering. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 6114–6122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.F.; Zheng, H.L.; Wang, Y.J.; Sun, Y.J.; An, Y.Y.; Liu, H.X.; Liu, S. Modified magnetic chitosan microparticles as novel superior adsorbents with huge “force field” for capturing food dyes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 367, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber-Samandari, S.; Saber-Samandari, S.; Joneidi-Yekta, H.; Mohseni, M. Adsorption of anionic and cationic dyes from aqueous solution using gelatin-based magnetic nanocomposite beads comprising carboxylic acid functionalized carbon nanotube. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 308, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.C.; Zheng, C.F.; Zheng, H.L.; Wang, Y.L.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, C.L.; Zhang, S.X. Polymer-grafted magnetic microspheres for enhanced removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 47029–47037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyzas, G.Z.; Bikiaris, D.N.; Seredych, M.; Bandosz, T.J.; Deliyanni, E.A. Removal of dorzolamide from biomedical wastewaters with adsorption onto graphite oxide/poly(acrylic acid) grafted chitosan nanocomposite. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 152, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.S.; Lin, J.X.; Fang, F.; Zhang, M.T.; Hu, Z.R. A new absorbent by modifying walnut shell for the removal of anionic dye: Kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 163, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Liao, Q.; Deng, W.; Huang, Y.; Mao, J.; Zhang, B.; Wu, G. The preparation of amorphous TiO2 doped with cationic S and its application to the degradation of DCFs under visible light irradiation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 684, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgolo, S.; Moreira, I.S.; Piccirillo, C.; Castro, P.M.L.; Ventrella, G.; Cocozza, C.; Mascolo, G. Photocatalytic Degradation of Diclofenac by Hydroxyapatite-TiO2 Composite Material: Identification of Transformation Products and Assessment of Toxicity. Materials 2018, 11, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, X.; Zeng, H.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, M.; Guan, W. Enhancement of photoelectrocatalytic degradation of diclofenac with persulfate activated by Cu cathode. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 320, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, P. Preparation and characterization of palladium nano-crystallite decorated TiO2 nano-tubes photoelectrode and its enhanced photocatalytic efficiency for degradation of diclofenac. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 254, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, J.; Bartels, P.; Mau, U.; Witter, M.; Tuempling, W.V.; Hofmann, J.; Nietzschmann, E. Degradation of the drug diclofenac in water by sonolysis in presence of catalysts. Chemosphere 2008, 70, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Independent Variables | Code | Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| pH | X1 | 5 | 7.5 | 10 |

| n1 (PDAC: AMPS) | X2 | 0.5 | 1.25 | 2 |

| n2 (AMPS: AM) | X3 | 0.2 | 2.6 | 5 |

| n3 (AM: DA) | X4 | 1 | 3.5 | 6 |

| n4 (DA: Fe3O4) | X5 | 1 | 3.5 | 6 |

| Irradiation time (min) | X6 | 30 | 75 | 120 |

| Pseudo First-Order Kinetic Model | Pseudo Second-Order Kinetic Model | Intraparticle Diffusion Kinetic Model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Concentration (mg L−1) | qmax,exp (mg g−1) | qe (mg g−1) | k1 × 102 (g mg−1 min−1) | R2 | qe (mg g−1) | k2 × 104 (g mg−1 min−1) | R2 | C (mg g−1) | kp | R2 |

| 600 | 561.7 | 197.5 | 0.91 | 0.9799 | 555.5 | 1.929 | 0.9991 | 351.9 | 11.57 | 0.8949 |

| 800 | 672.5 | 272.5 | 0.98 | 0.9887 | 666.6 | 1.364 | 0.9989 | 382.8 | 16.22 | 0.9021 |

| 1000 | 836.1 | 721.8 | 1.82 | 0.9426 | 909.1 | 0.5874 | 0.9986 | 317.4 | 30.04 | 0.8052 |

| Langmuir Isotherm Model | Freundlich Isotherm Model | D-R Isotherm Model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (K) | kL (L mg−1) | qmax (mg g−1) | RLa | R2 | kF | n | R2 | qd (mg g−1) | kd × 106 (mol2 kJ−2) | R2 |

| 298.15 | 0.02 | 144.9 | 0.048 | 0.965 | 7.15 | 1.81 | 0.994 | 124.7 | 1.74 | 0.748 |

| 308.15 | 0.044 | 366.3 | 0.022 | 0.946 | 50.4 | 2.51 | 0.997 | 361.6 | 1.22 | 0.862 |

| 318.15 | 0.025 | 266 | 0.038 | 0.935 | 20.5 | 1.98 | 0.998 | 261.8 | 1.9 | 0.806 |

| Processes | Water Matrix | Initial Concentration (mg L−1) | Degradation Conditions | Degradation Efficiency (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photocatalysis | Aqueous solution | 10 | S-TiO2: 0.2–0.8 g L−1 pH: 6.0–11.0 | 93.0 | [40] |

| Photocatalysis | Aqueous solution | 5 | TiO2: 4 g L−1 | 95.0 | [41] |

| Photoelectrocatalysis | Aqueous solution | 10 | Persulate: 1–10 mM pH: 5.6–10.0 | 86.3 | [42] |

| Photoelectrocatalysis | Aqueous solution | 5 | Pd/TNTs | 67.7 | [43] |

| Sonolysis | Aqueous solution | 50–100 | Ultrasonic frequency: 216–850 kHz | >90.0 | [44] |

| UV/H2O2/TAPAM-PDA-Fe3O4 | Aqueous solution | 0.1 | TAPAM-PDA-Fe3O4: 120 mg L−1 pH: 4.5 | >90.0 | This study |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Q.; Zheng, H.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, R.; Zhao, C.; Ding, W. Magnetic Template Anion Polyacrylamide–Polydopamine-Fe3O4 Combined with Ultraviolet/H2O2 for the Rapid Enrichment and Degradation of Diclofenac Sodium from Aqueous Environment. Polymers 2020, 12, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12010072

Sun Q, Zheng H, Hu X, Li J, Zhao R, Zhao C, Ding W. Magnetic Template Anion Polyacrylamide–Polydopamine-Fe3O4 Combined with Ultraviolet/H2O2 for the Rapid Enrichment and Degradation of Diclofenac Sodium from Aqueous Environment. Polymers. 2020; 12(1):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12010072

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Qiang, Huaili Zheng, Xuebin Hu, Jun Li, Rui Zhao, Chun Zhao, and Wei Ding. 2020. "Magnetic Template Anion Polyacrylamide–Polydopamine-Fe3O4 Combined with Ultraviolet/H2O2 for the Rapid Enrichment and Degradation of Diclofenac Sodium from Aqueous Environment" Polymers 12, no. 1: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12010072

APA StyleSun, Q., Zheng, H., Hu, X., Li, J., Zhao, R., Zhao, C., & Ding, W. (2020). Magnetic Template Anion Polyacrylamide–Polydopamine-Fe3O4 Combined with Ultraviolet/H2O2 for the Rapid Enrichment and Degradation of Diclofenac Sodium from Aqueous Environment. Polymers, 12(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12010072