3.1. Thermal Decomposition of FR-Containing Compounds

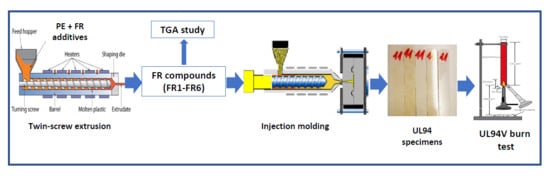

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) is a common technique to evaluate the thermal stability of various polymers giving information on weight loss, but no chemical information [

17,

18]. In our work, the thermal decomposition profiles of the pure components (additives, pure polymers) and of the FR-containing compounds were examined at a heating rate of 10 °C min

−1 under air and nitrogen atmospheres, and the relevant data correlated with the flammability properties (UL94 V results).

Starting with the pure polymers, all three grades exhibited a one-step decomposition (

Figure S2a) with the onset of the polyethylene backbone degradation in the range of (419–448) ± 3 °C (

Td,5%) under nitrogen (

Figure S2b). The maximum rate of weight loss was observed at 460 ± 8 °C and 466 ± 4 °C for LDPE-A and LDPE-T respectively, while for LLDPE at a higher value of 476 ± 1 °C. All the grades had negligible residue values, verifying the little char formation which characterizes polyolefins. When comparing the PE grades, LLDPE presented a higher thermal stability under nitrogen than LDPE-T, which in turn was found more stable than LDPE-A. The higher thermal stability of LLDPE when compared to the LDPE grades is in agreement with literature [

16,

19], and this ranking can be correlated with the branching degree and the number of the tertiary carbons that are the most reactive parts of the polymer molecule. LLDPE presents minimal branching when compared to the LDPE grades, and thus higher thermal stability.

On the other hand, the lower thermal stability of LDPE-A can be attributed to a larger number of tertiary carbons compared to LDPE-T. The same trend was observed in the Td values during the thermo-oxidative degradation (TGA under air), but for the onset of degradation (Td,5%), the temperatures were found to be similar, independent of the polyethylene type (410–417 °C). Furthermore, as anticipated, pure thermal degradation (under nitrogen) occurred at higher temperatures than thermo-oxidative degradation.

Turning to the pure FR additives, TGA analysis under nitrogen revealed that the

Td,5% varied between 243 and 380 °C, which is significantly lower than those of the pure polyethylene grades (

Figure S3). More specifically, the degradation of the alkoxy amine (triazine derivative, Flamestab NOR116), which is a nitrogen-based FR, was found to be a two-step process with maximum rates of weight loss at 290 and 437 °C, and with a residue of 4% at 800 °C, implying a low charring ability. PPM Triazine HF is also a nitrogen-based additive but it presents a higher residue (17.3% under N

2), showing its role as a charring source. The commercial mixture of the Triazine HF with ammonium polyphosphate (PPM Triazine 765) exhibits negligible char at 800 °C with more than two steps of thermal decomposition. The latter can be attributed to the used ratio of the CFA:APP in the commercial system. When the CFA content is high, the corresponding system has a superfluous charring source and a lack of acid source, so part of the CFA cannot be dehydrated into char and decomposes into gas products [

11].

Similarly, the two pentaerythritol derivatives (Charmor PP100 (polypentaerythritol) and Charmor DP40 (dipentaerythritol)) did not yield a significant amount of char (3.6%, 3.9%), and they presented mainly one step of thermal degradation with respective onsets of degradation at 243.1 °C and 303.8 °C. The pentaerythritol derivatives obviously decompose into gas phase products in the absence of an acid source. As far as ammonium polyphosphate (Exolit AP422) is concerned, its degradation profile presented a first weight loss peak at ca. 330 °C under N

2, attributed to the elimination of NH

3 and H

2O during the thermal decomposition of the polyphosphate. The second peak appearing at 641 °C is attributed to the release of phosphoric acid, polyphosphoric acid and metaphosphoric acid with the decomposition of APP [

11]. Finally, the char residue is high, i.e., 23.5% at 800 °C, because during the course of its decomposition, polyphosphoric acid itself is reverted to phosphoric acid and volatile gases, such as NH

3 and N

2, which cause the char to swell. NH

3 reacts with phosphoric acid, gathering in the swollen char layer to produce the corresponding salt, and this salt constitutes a block protecting the underlying material [

9].

ADK Stab FP 2200 exhibited the most promising TGA curve in terms of intumescence. It is a blend of phosphorus-nitrogen compounds and the thermal degradation occurs in two main steps, with the first Td at 292 °C and the second at 412 °C, corresponding potentially to the loss of water and small molecules such as NH3, further carbonization and the thermal degradation of char residue. The TGA curve is similar to the one of the alkoxy amine (Flamestab NOR116), but the char residue at 800 °C was found to be much higher, i.e., 51%. This char yield was in fact the highest value among all the examined FRs, implying that the pertinent system combines a carbon source, an acid source and a blowing agent, and presents high charring ability under the synergism of phosphorus and nitrogen compounds.

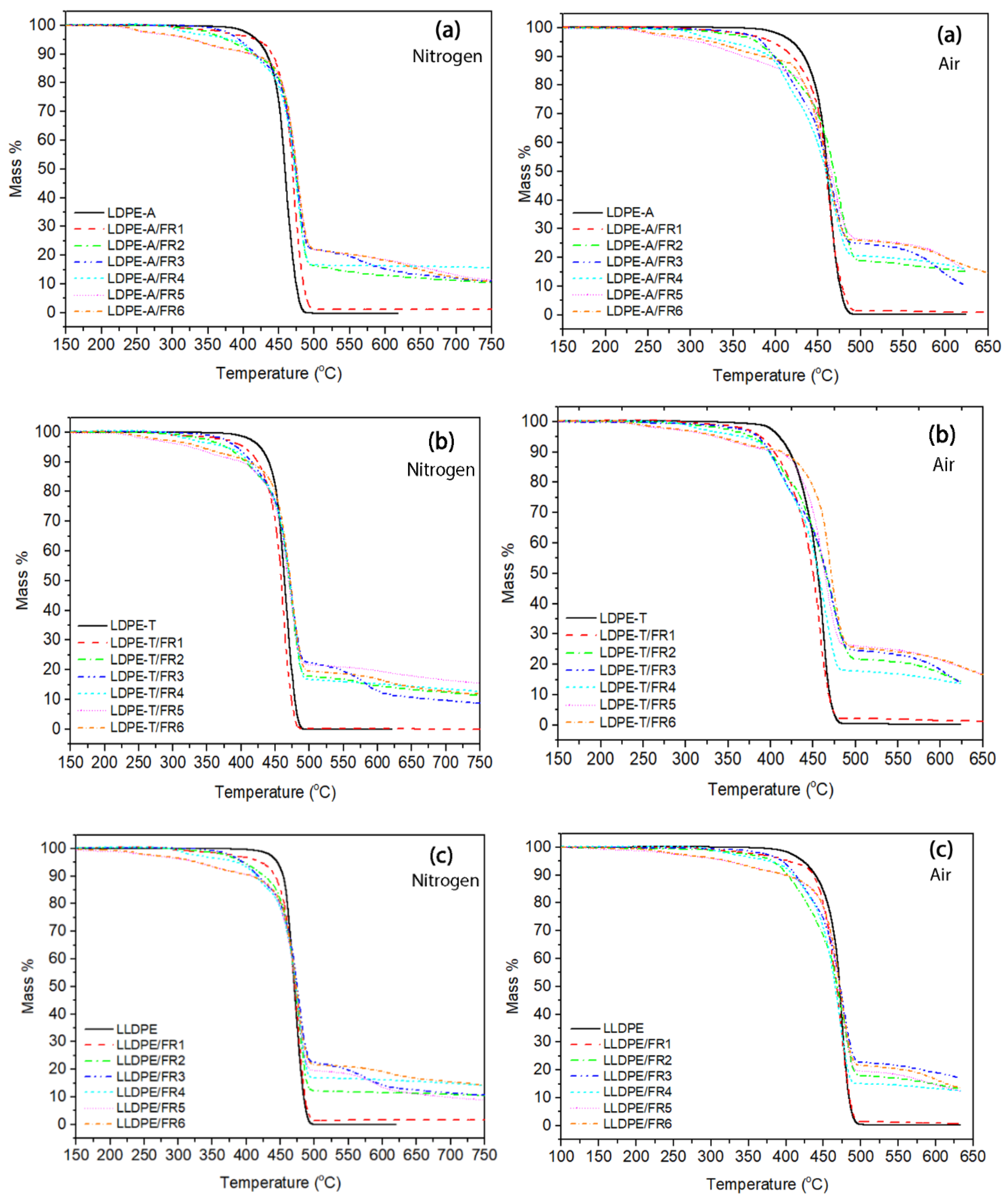

The presence of the FRs in the polymer matrix resulted in changes in the TGA curves compared to the reference polymers. As can be seen in

Figure 2, the thermal decomposition of the FR-containing compounds involved two or even more degradation steps, with the onset temperature lower compared to the onset of the pure grades; the

Td,5% value was lower in the range of 330–422 °C under nitrogen (vs. 419–448 °C for pure polymers), with the standard deviation of the mean (STDEV) ranging from 1–5 °C for the FR3 and FR4 compounds. This decrease is attributed to the lower stability of the bonds in the FR molecules (such as P–O and C–N) compared to the uniform C–C bonds in polyethylene, and thus the earlier degradation of the additives [

6,

20]. The lowest

Td,5% values were observed in the cases of FR5 and FR6, i.e., when the pentaerythritol derivatives and APP were used, and can be attributed to the formation of thermally unstable ester mixtures between the –P–OH group in the APP molecules and the –OH group in the CFA [

8].

When comparing the degradation temperatures at the maximum weight loss (

Td), the addition of FRs resulted in an increase in

Td, proving the formation of a protective char layer and improving thus the thermal stability of the grades. In the work of Makhlouf et al. [

20], an increase in the

Td by 30 °C was observed in the case of the effective LLDPE FR formulation. In the work of Xie and Qu [

21], the flame retarding mechanism of the expandable graphite/halogen-free FR system for LLDPE also gave rise to such an increase in the thermo-oxidative degradation temperature. In our work, as can be seen in

Figure S4 in the Supplementary Material, the

Td increase is kept at lower values: for the two LDPE grades,

Td reached 478 °C (STDEV: 1–3 °C) vs. 460 and 465 °C (ca.15 °C increase), while for the LLDPE compounds the increase was almost insignificant (up to 2 °C). The trend was found similar under thermo-oxidative degradation (

Figure S4b), with the difference that the temperatures (

Td,5%,

Td) were shifted to lower values under air, as was the case with the pure polymers.

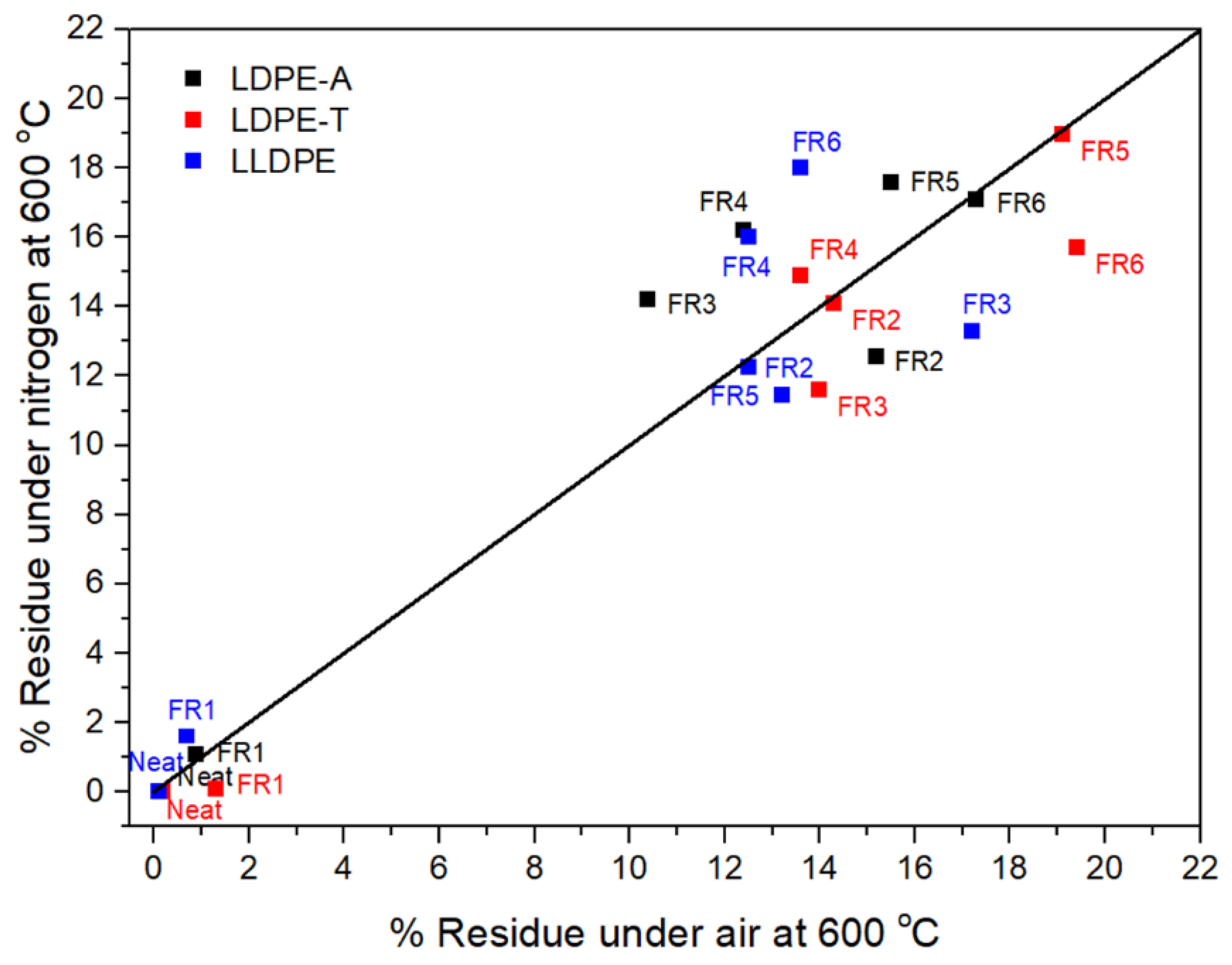

The residue in the TGA can also be correlated with the formation of a protective char layer during the polymer combustion [

1,

7,

8,

11,

20,

22,

23] (

Figure 3). FR1, which contained a nitrogen-based additive, failed to increase the char yield, so it is anticipated that the relevant formulation will not be efficient due to a lack of the acid source. On the other hand, the addition of the other FRs dramatically increased the residue under air and nitrogen atmospheres, reaching almost 19% under nitrogen at 800 °C, with the highest value observed for FR4 (16.2 ± 0.4%) for LDPE-A, FR5 (19%) for LDPE-T, and FR6 (18%) for LLDPE. It is important to emphasize that the low residue of the pure pentaerythritol derivatives (Charmor DP40 and PP100) was not observed in the FR5 and FR6 formulations, since along with the acid source, they can result in an effective intumescent system. However, it should be pointed out that in the literature, there is no direct correlation between the char residue and the UL94 V ranking; when the compound presents higher residue, it presents potentially better flammability properties, but it is not necessary that the highest amount of char gives V0 in UL94 ranking. This also has to do with the proper ratio of charring agent to acid source, so as to produce the optimum char layer morphology, e.g., tiny bubbles embedded on the surface of each large bubble, and a compact and continuous intumescent char [

1].

3.2. Kinetics of Thermal Decomposition

The Kissinger method was used to study the kinetics of the thermal decomposition of the FR polyolefin systems under air atmosphere. The Kissinger method (Equation (3)) relates the apparent activation energy of the solid reaction to the logarithm of the heating rate (

q) and the reciprocal of the absolute temperature at the maximum degradation rate (

Td) [

24,

25,

26]:

where

Td and α

d are the temperature and the conversion degree at the maximum degradation rate, respectively.

A plot of against produces a fitted straight line, and the apparent activation energy, Εa is calculated from the slope (). The advantage of the Kissinger model is that the activation energy can be calculated without any prior knowledge of the thermal degradation reaction mechanism, and Εa serves as an indicator of the material’s thermal stability: a high activation energy suggests a high thermal stability.

The relevant Kissinger correlation coefficients (R

2) and the calculated

Εas are presented in the

Supplementary Information Table S2, where it should be mentioned that in the multistep decomposition (under air) profiles, the

Td values used for the calculations corresponded to the highest values of the mass loss rate. For the pure grades, the fitting of the data to the Kissinger equation is satisfactory (R

2: 0.9823–0.9945), with

Ea values for the LDPE grades in the range of 303–319 kJ mol

−1, and for LLDPE slightly lower at 287 kJ mol

−1. Regarding the FR formulations of both the LDPE grades, the fitting was generally poor, probably because of the multistep character of the decomposition profiles. However, when comparing the data of the satisfactory fittings (R

2 > 0.95), it can be seen that the

Ea values in the LDPE FR-containing formulations are higher compared to those of the pure polymers, e.g., for LDPE-A/FR3 the

Ea was found to be 346 kJ mol

−1 and for LDPE-T/FR4 it was 388 kJ mol

−1. In the case of the LLDPE FR formulations, the Kissinger model better described the thermo-oxidative degradation kinetics because of the higher R

2 values (0.914–0.989); LLDPE presented smoother decomposition profiles than the LDPE FR compounds, being similar to those of the pure polymer grades. The general trend for LLDPE is that the FR grades presented higher

Ea values compared to the pure polymer, in the range of 308–348 kJ mol

−1, with FR3 presenting the highest

Ea value (348 kJ mol

−1).

An additional thermal degradation kinetics model, the Coats-Redfern model (Equations (4) and (5) [

24]), was examined using the data of thermal (under nitrogen) and thermo-oxidative (under air) decomposition at a heating rate of 10 °C min

−1. This method can deal with the main degradation region of the TGA curve of the material, and only requires the TGA data at one heating rate to calculate the related reaction order

n, reaction activation energy

Ea and the pre-exponential factor A:

Generally, the logarithmic term on the right part of the above equations is regarded as constant. The determination of the reaction order n can then be finished by linear fitting of the dependence of the left part of Equations (4) and (5) on –1/T. The n value at the best R

2 obtained is the real reaction order, and the apparent

Ea and the pre-exponential factor A can be calculated. The relevant values are presented in the

Tables S3 and S4 in the Supplementary Material. Regarding the pure polymers under nitrogen, the reaction order, n, was calculated close to 1, indicating a first-order degradation kinetics, with a simple degradation reaction mechanism.

Ea values under nitrogen (363–537 kJ mol

−1) were generally found higher compared to those in air (218–413 kJ mol

−1), in agreement with the aforementioned shifting of the degradation temperatures,

Td,5%, and

Td, to lower values under air (

Figure S4 in Supplementary Material). However, when comparing the E

a values both of the pure and the flame retarded materials, under nitrogen and under air, it can be seen that the pure polymers display

Ea values significantly higher than those of the flame retarded materials. Such a result is different from the anticipated behavior, since the incorporation of FRs in the polymer matrix should increase the polymer’s thermal stability and thus an increase in the E

a value is expected. It can be herein suggested that the Coats-Redfern method may not be applicable in the case of intumescent flame retardants. That can be attributed to the multistep character of the flame retarded materials’ decomposition profiles [

27].

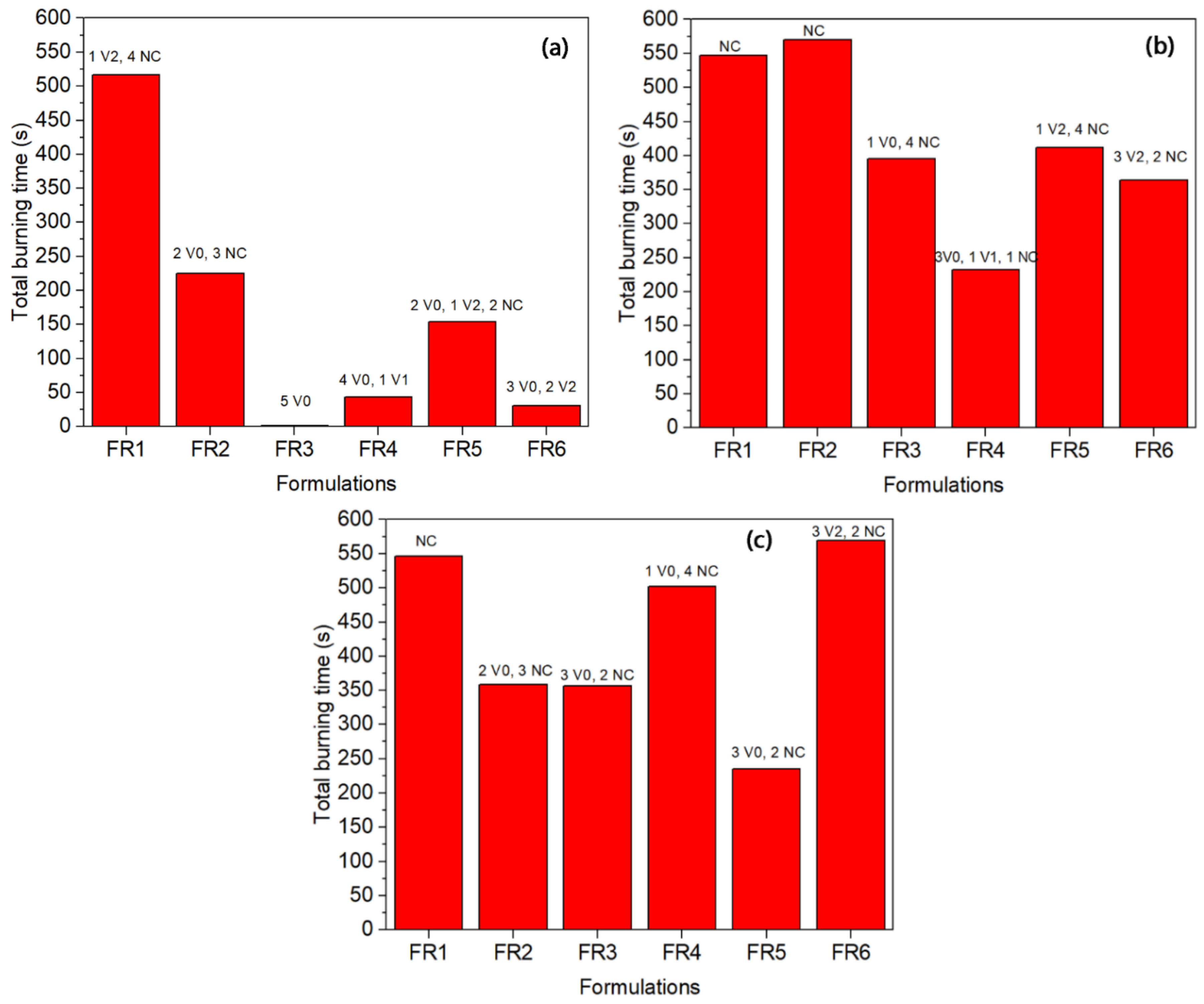

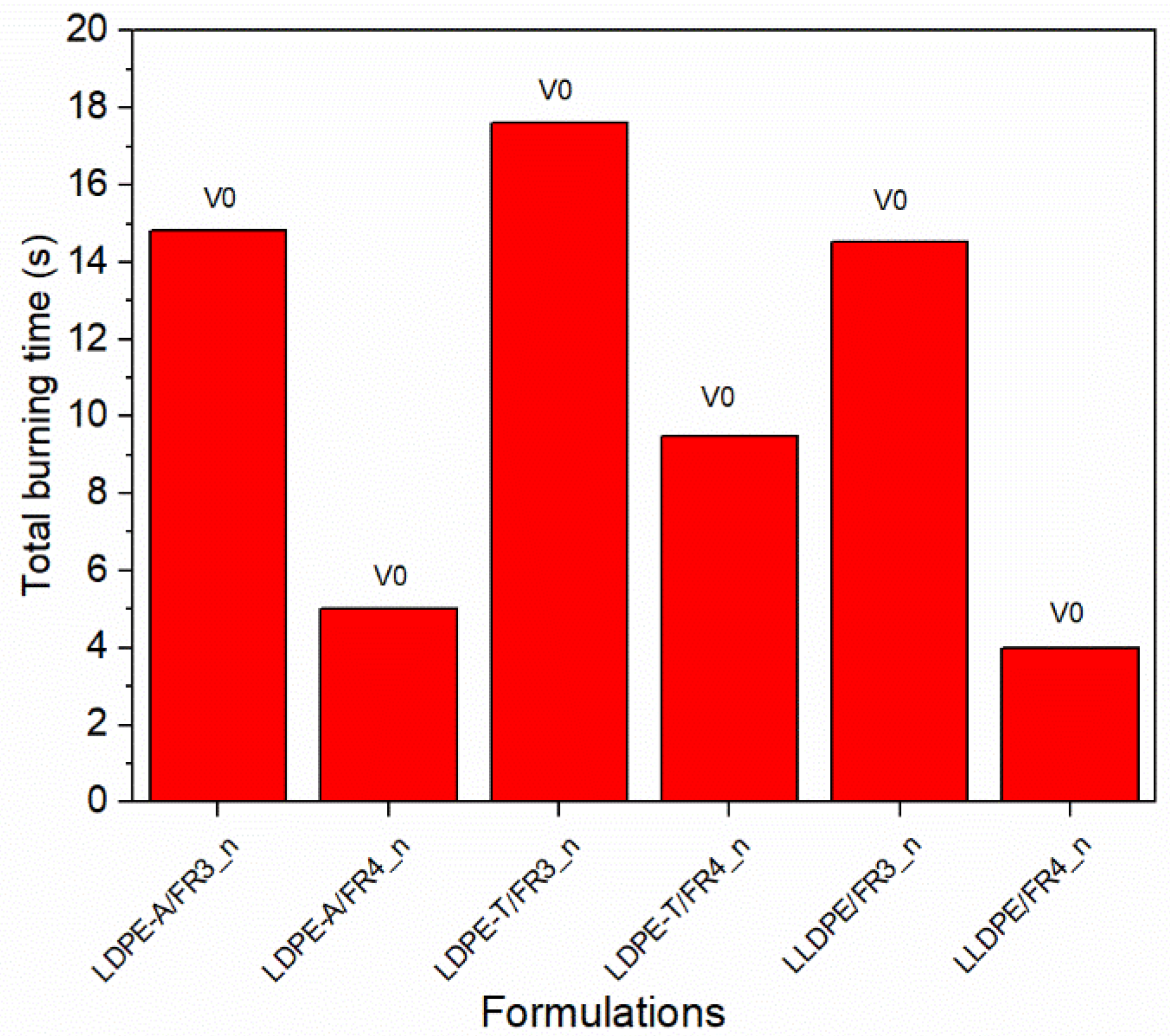

3.3. Flammability

UL 94 tests are widely used to evaluate the flame resistance of polymers. The results fall into three categories with burning ratings V0, V1, and V2, with V0 corresponding to the highest level of flame resistance. The results of the FR-containing polyethylene grades are given in

Figure 4. In all the grades, FR1 presented a low flame resistance since the total burning time was the longest and the samples failed in the UL 94 testing (NC: not classified). It is in agreement with the TGA results where the char yield was low (2%), and this proves that nitrogen-based compounds alone cannot achieve a V0 rating for polyethylene [

11]. In fact, the relevant nitrogen-based radical generator is mentioned to perform well when combined with triazine derivatives for polyolefin foams and films [

28].

In the case of LDPE-A (

Figure 4a), FR3 was proved significantly efficient reaching a UL 94 V0 rating and a low total burning time (1.4 s). FR3 is the mixture of the triazine derivative and APP in a 1:3 ratio of the charring agent to APP with a total loading of 35 wt.%; the mechanism of phosphorus-nitrogen synergism is considered to be provided by the ultimate formation of phosphorous oxynitride, which is a high-temperature resistant material [

28]. FR3 performance can be correlated with the TGA results, where it presented the highest onset of thermal degradation for the LDPE-A FR-containing compounds, with an increase in

Td by 16 °C and a char yield of almost 10 ± 1% at 800 °C under nitrogen. FR4 presented the next lower burning time (43.3 s), a performance which can again be correlated with the high char yield in the TGA (14 ± 1% at 800 °C) and an increase in

Td by almost 18 °C. The other formulations (FR2, FR5, FR6) presented poorer results in terms of UL 94 ranking; especially for FR2 it can be said that the commercial mixture of the triazine derivative with APP (PPM Triazine 765) was not as efficient as the FR3-containing grade, where the same mixture was prepared in a ratio CFA:APP = 1:3. The low FR efficiency of FR2 can also be correlated with the zero char yield of the additive alone in the TGA test. The performance of all the examined LDPE-T FRs was poorer than that of LDPE-A. Again, FR3 and FR4 can be considered to be the most promising, but they failed to obtain a safe UL 94 ranking. In the case of LLDPE, FR3 and FR5 presented lower burning times of 356 and 235 s respectively, but again they failed in presenting a safe UL 94 ranking.

When comparing the three different polyethylene grades, it is interesting to note that in general, all the FRs presented smaller burning times and higher reproducibility in the case of the LDPE-A compared to the LDPE-T and LLDPE. Inherently, LDPE-A is the least thermally stable polyethylene, as mentioned above, and was found to be more effectively flame retarded through the examined formulations. A possible reason for the poorer performance of the flame retardants in LDPE-T and LLDPE can be the less homogenous dispersion of the additives in the polymer matrix and/or the premature decomposition of the additives, e.g., of APP, due to internal shear during the extrusion and/or the injection step. Therefore, we performed SEM analysis on the fractured cross section surfaces of the UL 94 bars prior to and after the testing (

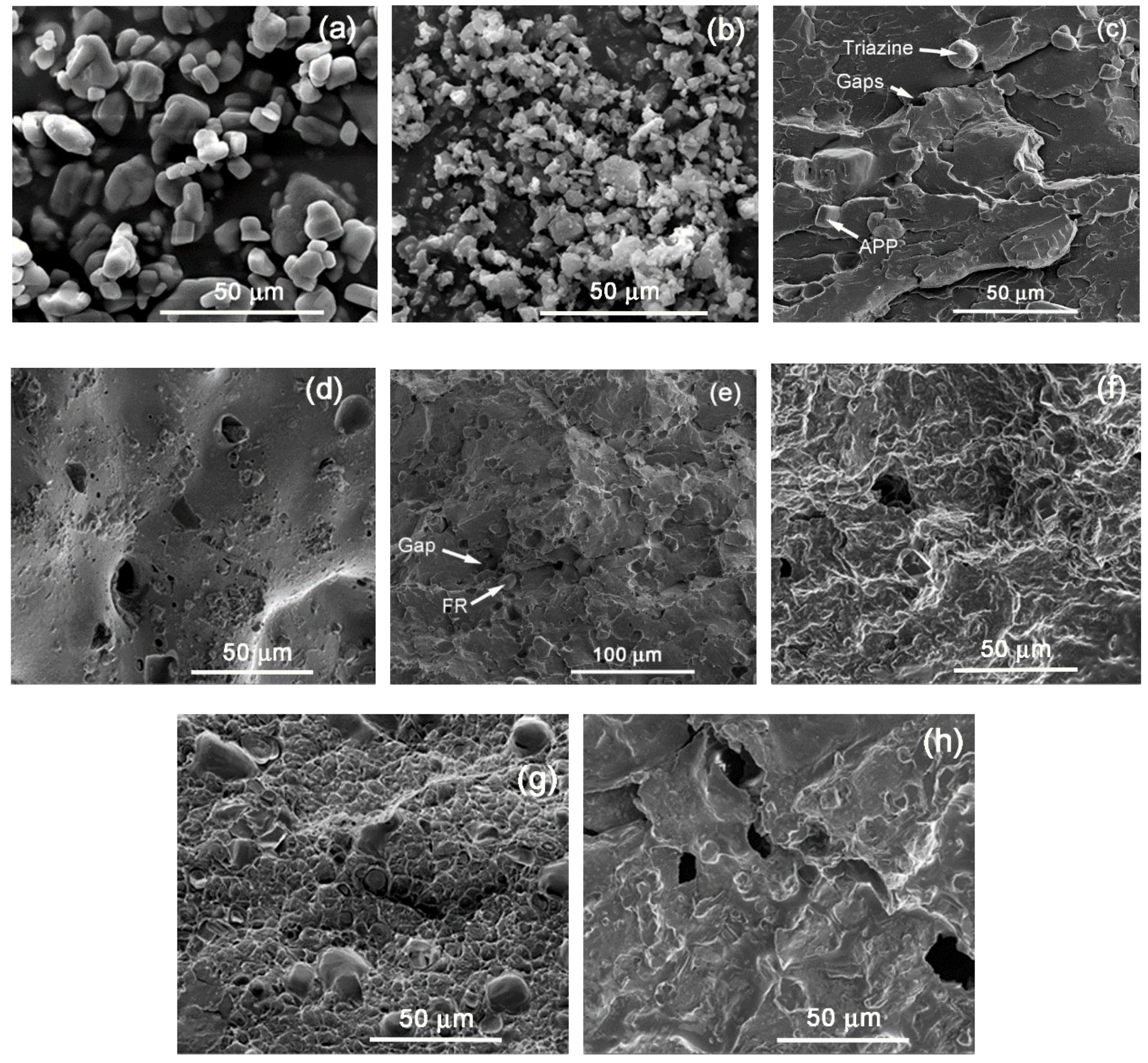

Figure 5).

Starting with the grade LDPE-A/FR3, which gave the safest V0 ranking result, it can be seen that the additives (APP, Triazine,

Figure 5a,b) were well dispersed in the polymer matrix with a small number of aggregates (

Figure 5c). The smooth surface of the commercial APP [

22] and the shape of Triazine HF can be distinguished in consistence with similar SEM images for APP systems in polyolefins [

23]. However, the additives’ incorporation induced some gaps/voids and cavitations, that are a sign of incompatibility and can have a negative impact on the mechanical properties [

22]. The gaps/voids can especially be attributed to the premature decomposition of the APP due to internal shear and the release of NH

3. The char (

Figure 5d) for LDPE-A/FR3 looks dense and coherent with an intense foamed structure. Despite the formation of some small holes, a nicely formed intumescent layer is observed which successfully prevented oxygen and heat exchange to penetrate deeper into the material, thus showing the best herein flame retardance performance [

20].

In LDPE-T/FR3 (

Figure 5e) and LLDPE/FR3 (

Figure 5g), the additives can also be seen in the polymer matrix, but the surface is less continuous and presents a higher extent of voids, potentially implying a more intense decomposition of APP which will physically impede the formation of a dense and compact protective layer [

1] in the subsequent burning test, resulting in formulation failure. The intense decomposition of APP can be correlated with the different melt viscosities and thus with internal shear with respect to the branching type and degree. The processing behavior of LDPE-A and LDPE-T will be different due to the long-chain branching [

12,

13,

14]: LDPE-T presents a higher melt viscosity, since the molecules are strongly entangled with each other due to the comb-like branching, and the shear thinning behavior is stronger at higher rates due to shear-induced partial disentanglement. On the other hand, the LDPE-A molecules with nearly spherical shapes are less entangled and have a lower viscosity. LLDPE has even more voids than LDPE-T, and this can again be attributed to an even higher internal shear. At the shear rates commonly applied during extrusion, LDPE presents increased shear thinning compared to the linear and entangled LLDPE molecules and therefore the melt viscosity of LDPE at higher shear rates is significantly lower than that of the linear resins [

12,

15].

After the UL 94 test, the chars of LDPE-T/FR3 (

Figure 5f) and LLDPE/FR3 (

Figure 5h) were also investigated by SEM. A different morphology was observed than in the case of LDPE-A/FR3: The char shows some foaming, nevertheless big gaps and/or holes were created which allowed oxygen to penetrate deeper into the material and therefore resulted in poor flame retardancy [

20]. This can be the consequence of poor or inhomogenous dispersion of the additives.

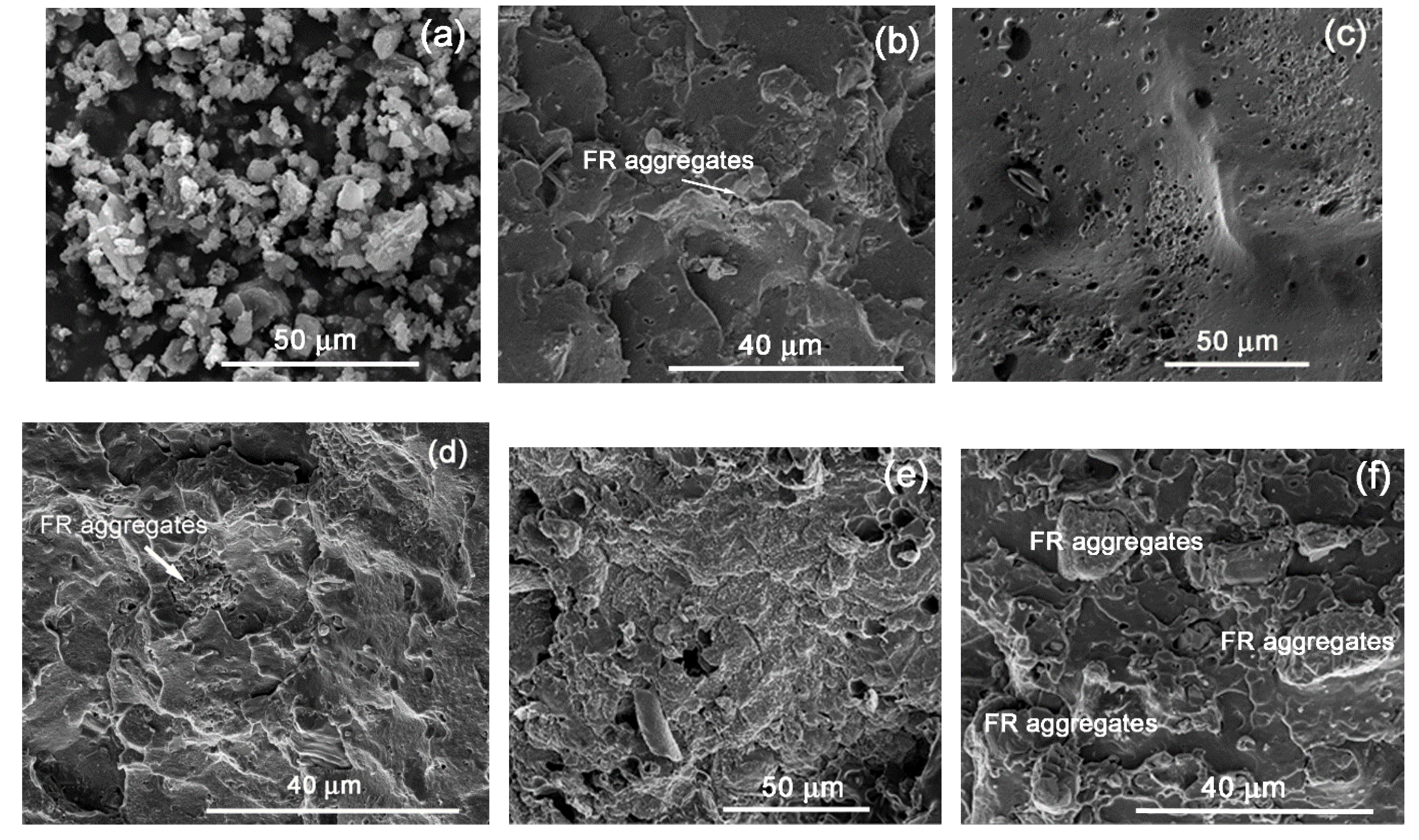

On the other hand, in the FR4-containing grades (

Figure 6), the voids are significantly less, but in all cases agglomeration of the additive particles is evident, which seems to be the main reason for the inconsistency in the FR results, even in the case of LDPE-A. However, the dispersion problems are more obvious in the case of LLDPE, probably due to the higher melt viscosity. The char quality for all the FR4 grades was also investigated by SEM. Accordingly, LDPE-A/FR4 (

Figure 6c) showed a surface similar to that of LDPE-A/FR3, but the swelling of the surface was weaker with numerous tiny holes. This resulted in a lower UL94 classification, nevertheless still four V0 classifications were achieved. On the contrary, in the cases of LDPE-T/FR4 (

Figure 6e) and LLDPE/FR4 (

Figure 6g), the char morphology was totally different: almost no swelling of the surface and a discontinuous char, resembling the initial morphology of the surfaces prior to the burn test.

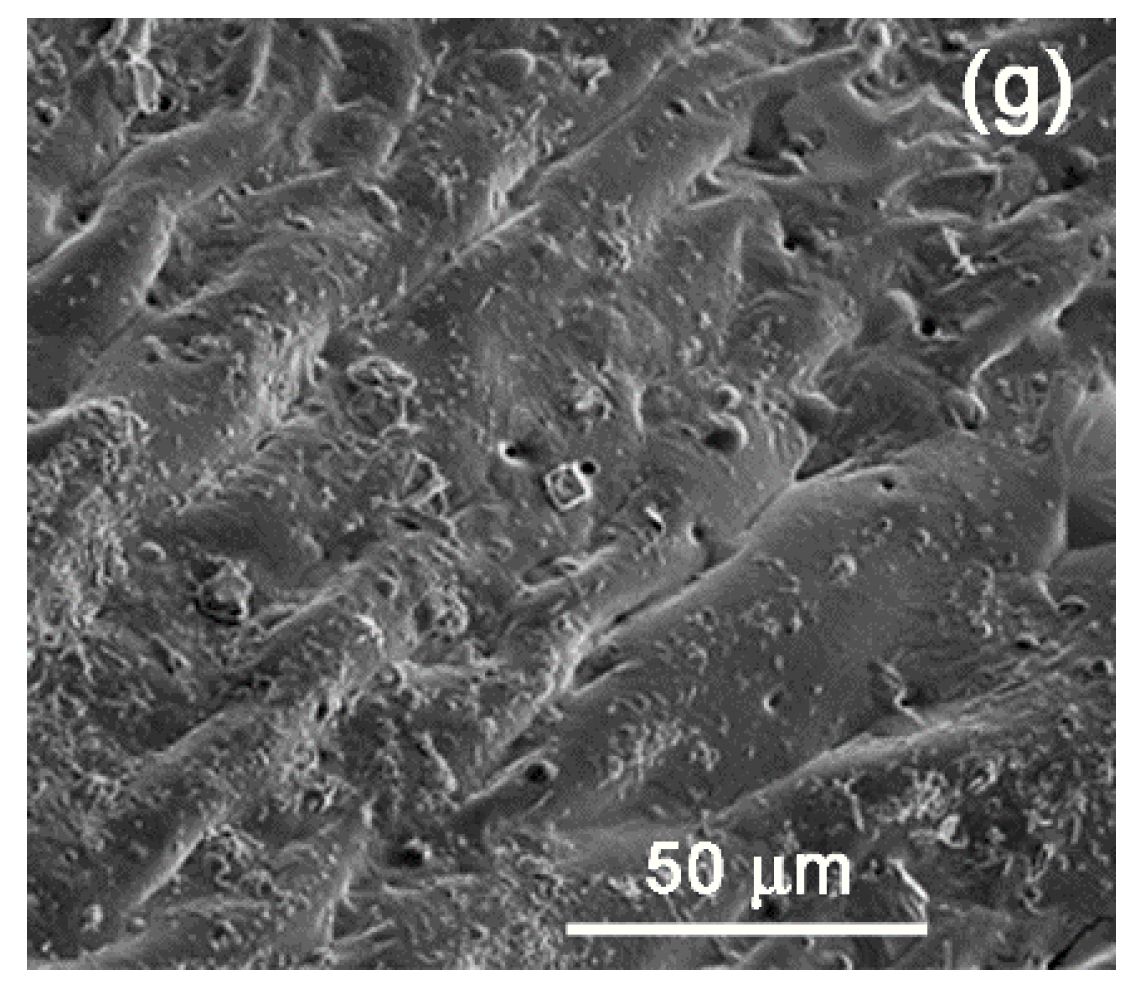

To address the dispersion problems and to obtain a more reliable flammability performance, especially for the LDPE-T and LLDPE grades, we tested six (6) additional FR formulations (

Table S5 in the Supplementary Information) based on the most promising ones (FR3 and FR4) using compression molding to manufacture the UL94 bars instead of injection molding, so as to dissipate the melt viscosity issues. The new compounds presented stable V0 classification with no dripping and total burning times ranging from 4.0 to 17.6 s (

Figure 7), revealing a reliable FR performance due to the higher UL94 bars’ homogeneity.

3.4. Mechanical and Rheological (MFR) Properties

Table 2 summarizes the rheological and mechanical properties of the three pure polyethylenes and of the most promising FR formulations (FR3 and FR4 compounds). The processability of the FR-containing grades can be roughly assessed based on the MFR values. Regarding the LDPE grades, the FR3 formulation did not greatly influence the MFR of the pure polymers, while FR4 induced a decrease by more than 50%, indicating higher melt viscosities. In the case of LLDPE, both formulations (FR3 and FR4) resulted in MFR decrease by more than 40%.

Regarding the mechanical properties, pure LLDPE has higher values of elongation at break than LDPE, because of the difference in branching [

19]. When adding the FRs, it can be generally said that the tensile and the impact strength were not significantly affected, despite the high loadings (FR3: 35 wt.%, FR4: 30 wt.%). More specifically, in LDPE-A, the tensile strength and the elongation at break decreased by 27–33% (FR3) and 23–34% (FR4), along with an increase of the Young’s modulus (E) by 27 and 15% respectively; the corresponding impact strength remained constant at ca. 20 kJ m

−2. The relevant changes can be considered to be lower than or comparable to the values mentioned in literature (>25% change for tensile strength) [

1,

21] for similar loadings of halogen-free flame retardants. Keeping in mind that LDPE-A/FR3 is the most promising formulation in terms of safe UL94 V0 ranking, it is concluded that it can also satisfy the requirements in terms of good mechanical properties.

The LDPE-T and LLDPE formulations presented changes in the tensile properties compared to the pure grades similar to those of LDPE-A, despite the poorer distribution and dispersion of the additives in the polymer matrix, as discussed above based on the SEM analysis. In fact, the most significant change was observed in the Young’s modulus of LDPE-T: E increased with ca.50% for the FR3 and FR4 compared to the pure grades, with FR4 showing the highest stiffness in both grades.

3.5. Melting Behavior

The melting behavior of the most promising FR formulations (FR3 and FR4 compounds) was examined in order to identify the effect of the flame retardants on the melting point and the crystallinity of the polyethylene grades (

Table 3).

Pure LDPE-T was found to crystallize earlier (at higher

Tc) than LDPE-A, presenting a higher mass fraction crystallinity and a higher melting point during the 2nd heating. The crystal density in LDPE-A was obviously lowered by the incorporation of chain imperfections into the crystal lattice and resulted in lower values of x

c [

12]. Autoclave resins tend to have better see-through clarity due to the smaller spherulites formed during the crystallization process [

12]. The crystals in LLDPE, which exhibits a higher density fraction with minimal branching, are thicker than those in LDPE [

15], and therefore the determined

Tm values were found at 122 °C, ca. 10 °C higher than those of the two LDPEs. The minimal branching of LLDPE also permits faster melt crystallization, so the

Tc value is increased (ca. 105 °C for LLDPE vs. 94 and 96 °C for LDPE-A and LDPE-T respectively).

In general, the incorporation of the flame retardants (FR3, FR4) at the specific loadings (30 and 35 wt.%) did not significantly change the thermal properties of the polyethylene grades, implying limited action of the additives as nucleating agents: A slight increase in the melting point by almost 2 °C was found for all three PE grades, while in the case of FR3, an increase in the mass fraction crystallinity was also observed without a significant change in the

Tc temperature for LDPE-A and LDPE-T. APP was found to act as an effective nucleating agent in the case of PP at loadings of 30% wt. [

29,

30], so its high content in FR3 (26.25 wt.%) may explain the higher attained crystallinity in all three the PE grades compared to FR4. Finally, in the case of the most easily crystallizing LLDPE, the nucleating role of the additives becomes more noticeable, since along with the increase in

xc (2nd heating), the melt crystallization upon cooling also occurred earlier, i.e., at a noticeable higher

Tc.