Photocatalytic Properties of Sol–Gel Films Influenced by Aging Time for Cefuroxime Decomposition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

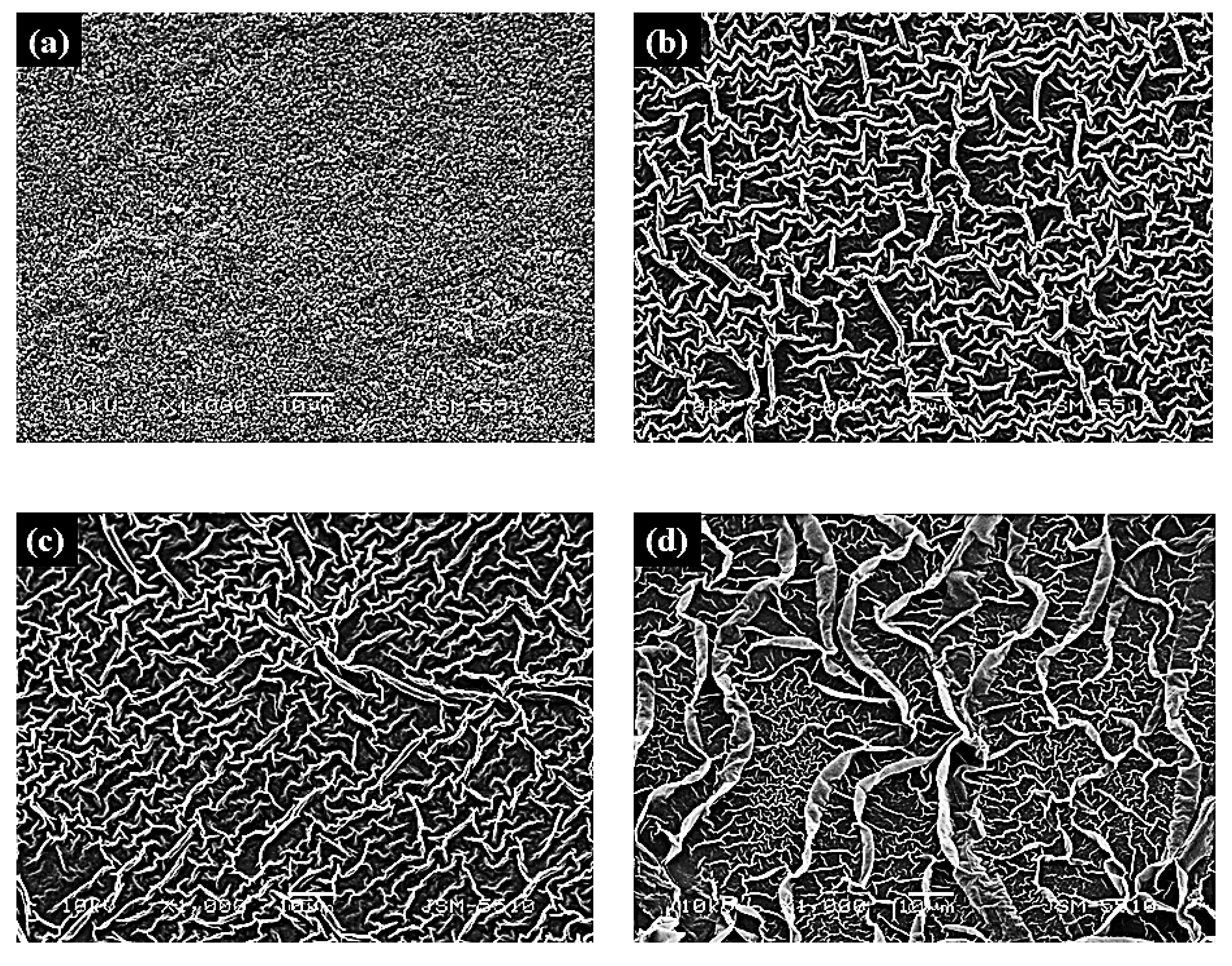

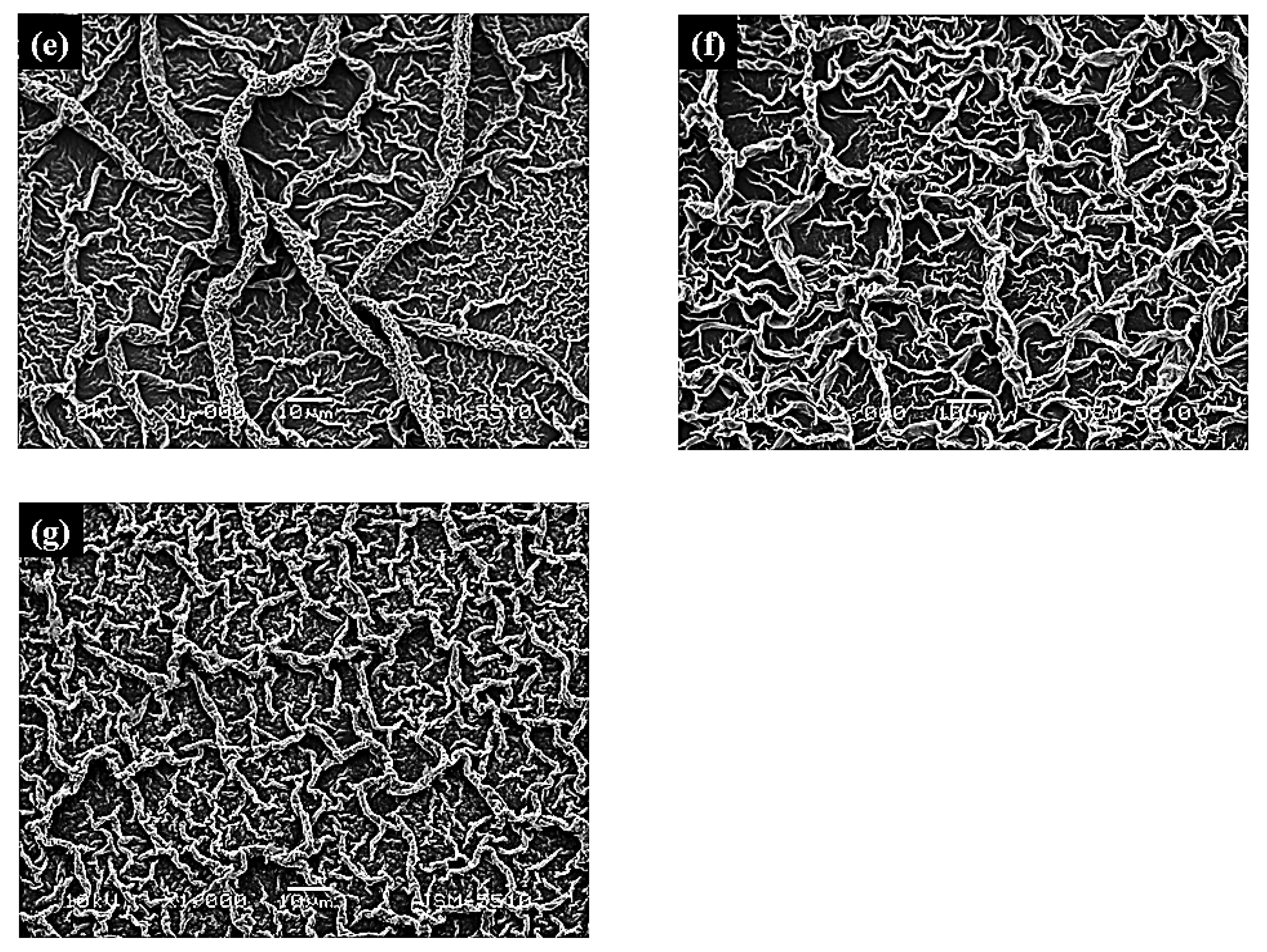

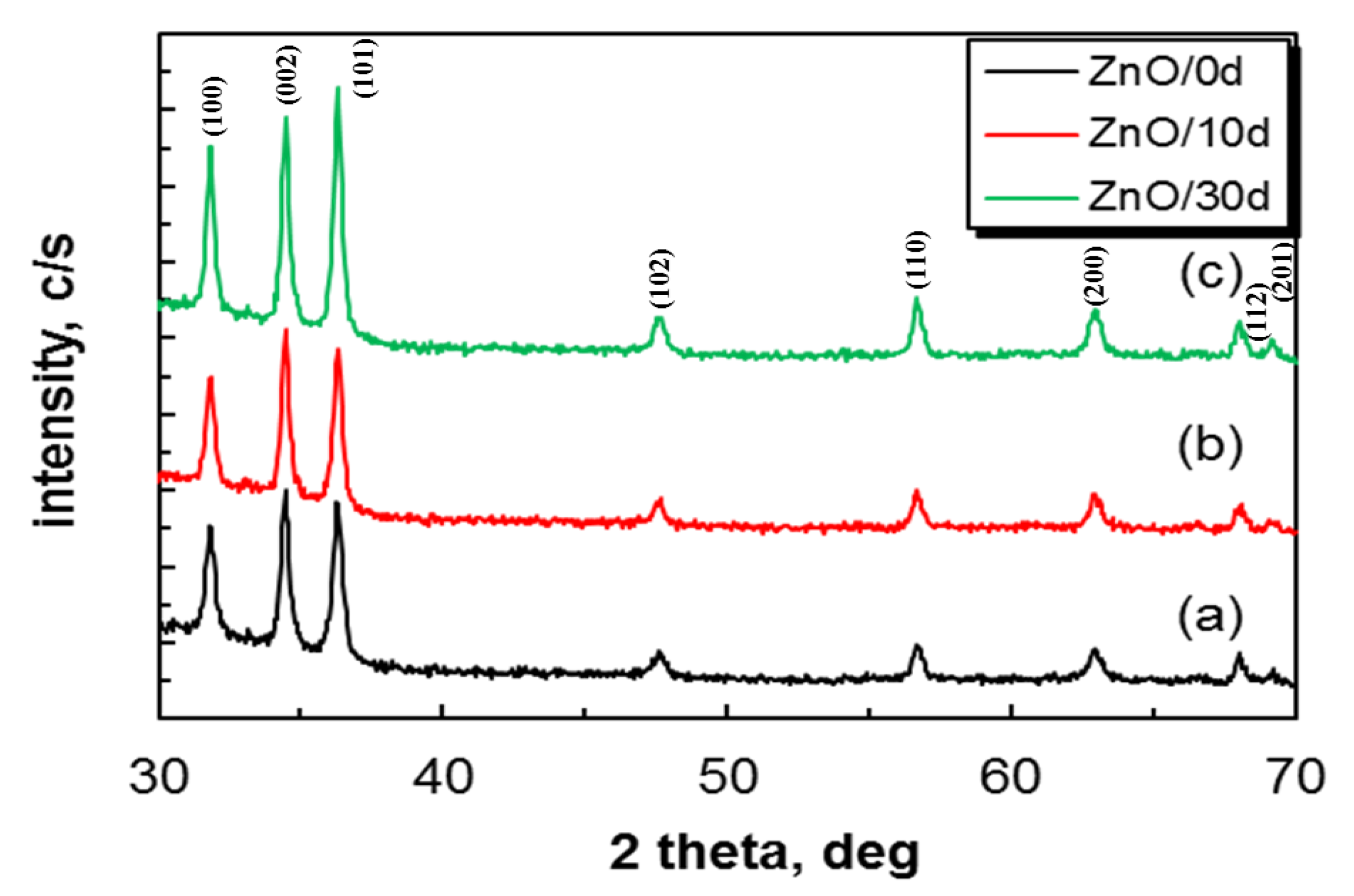

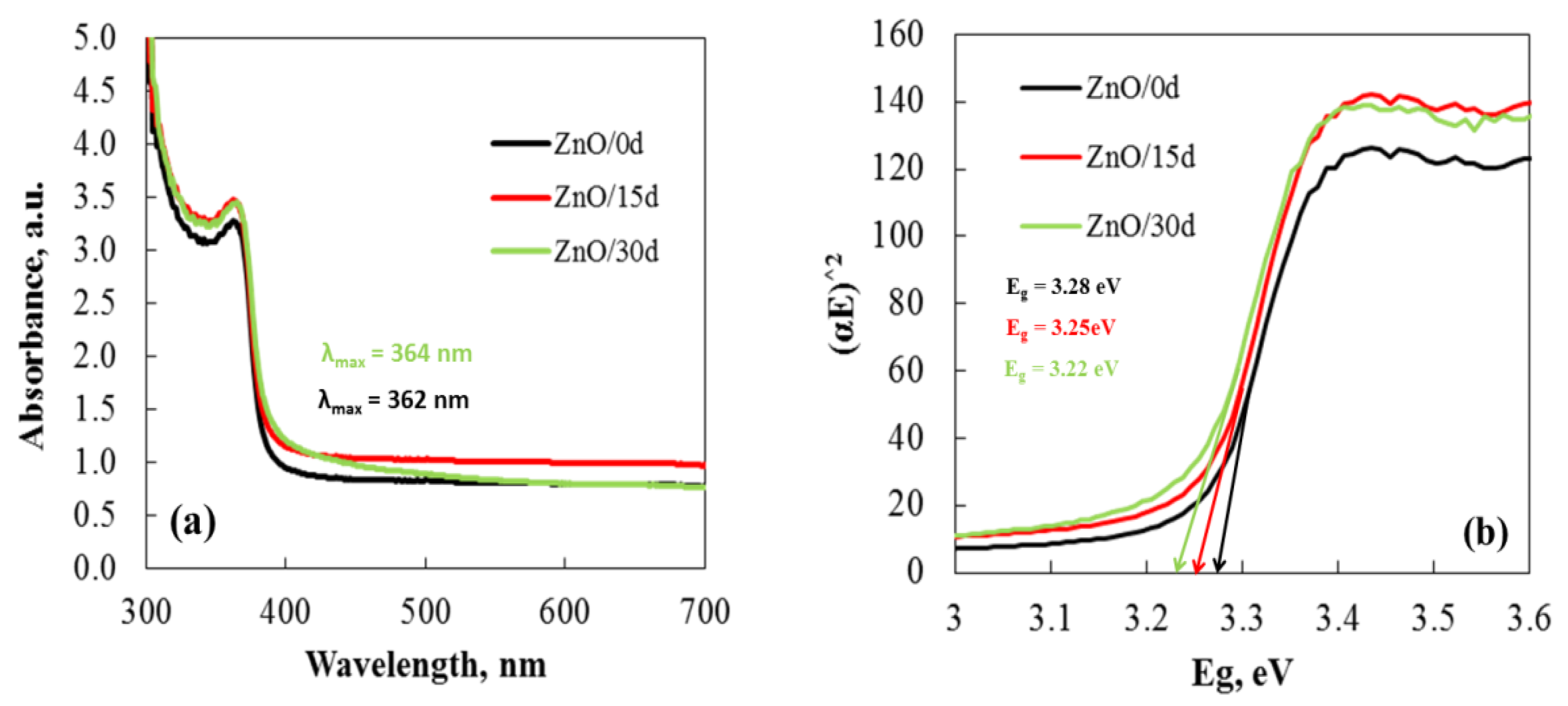

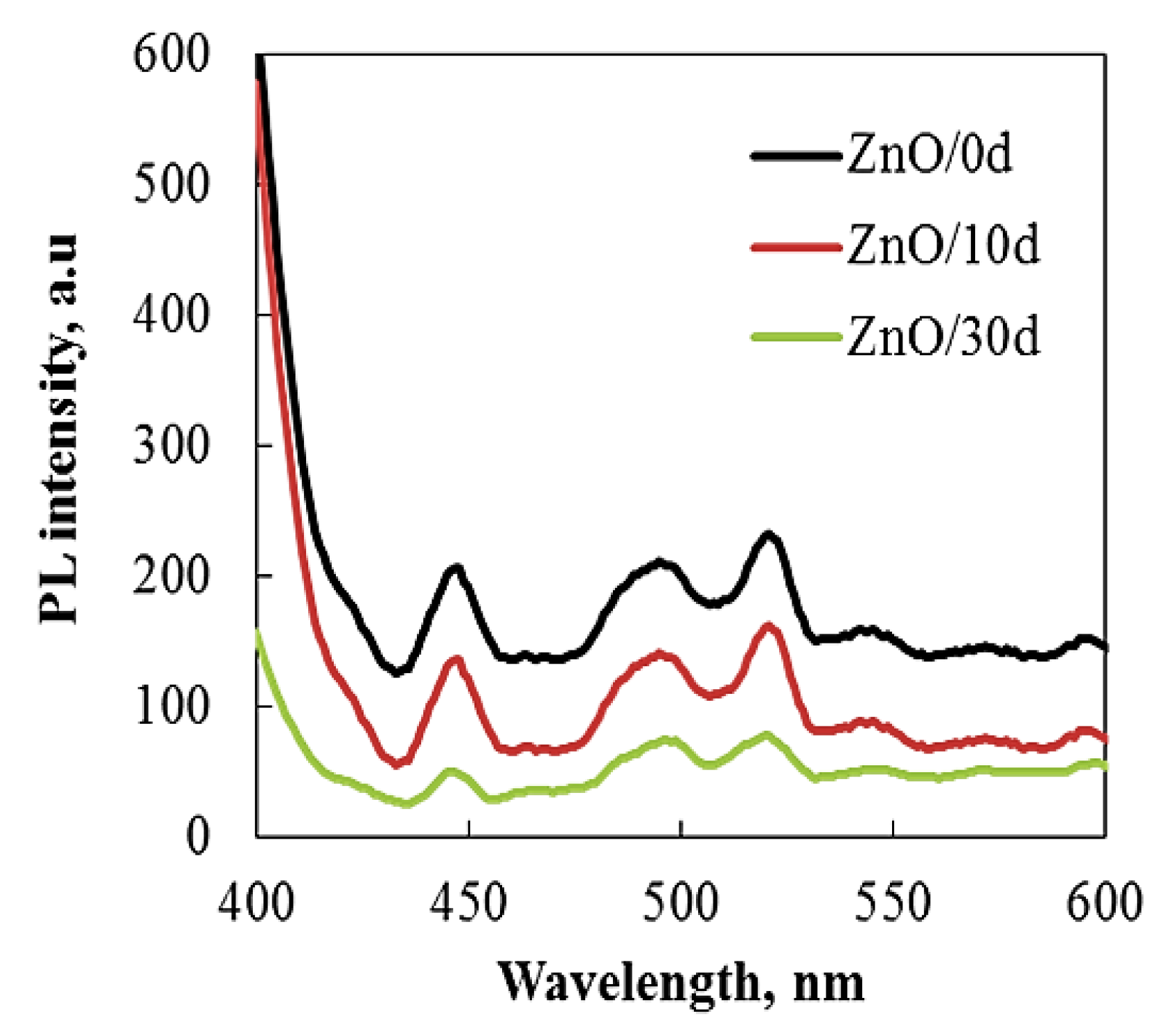

3.1. Structure Evaluation of Sol–Gel ZnO Films

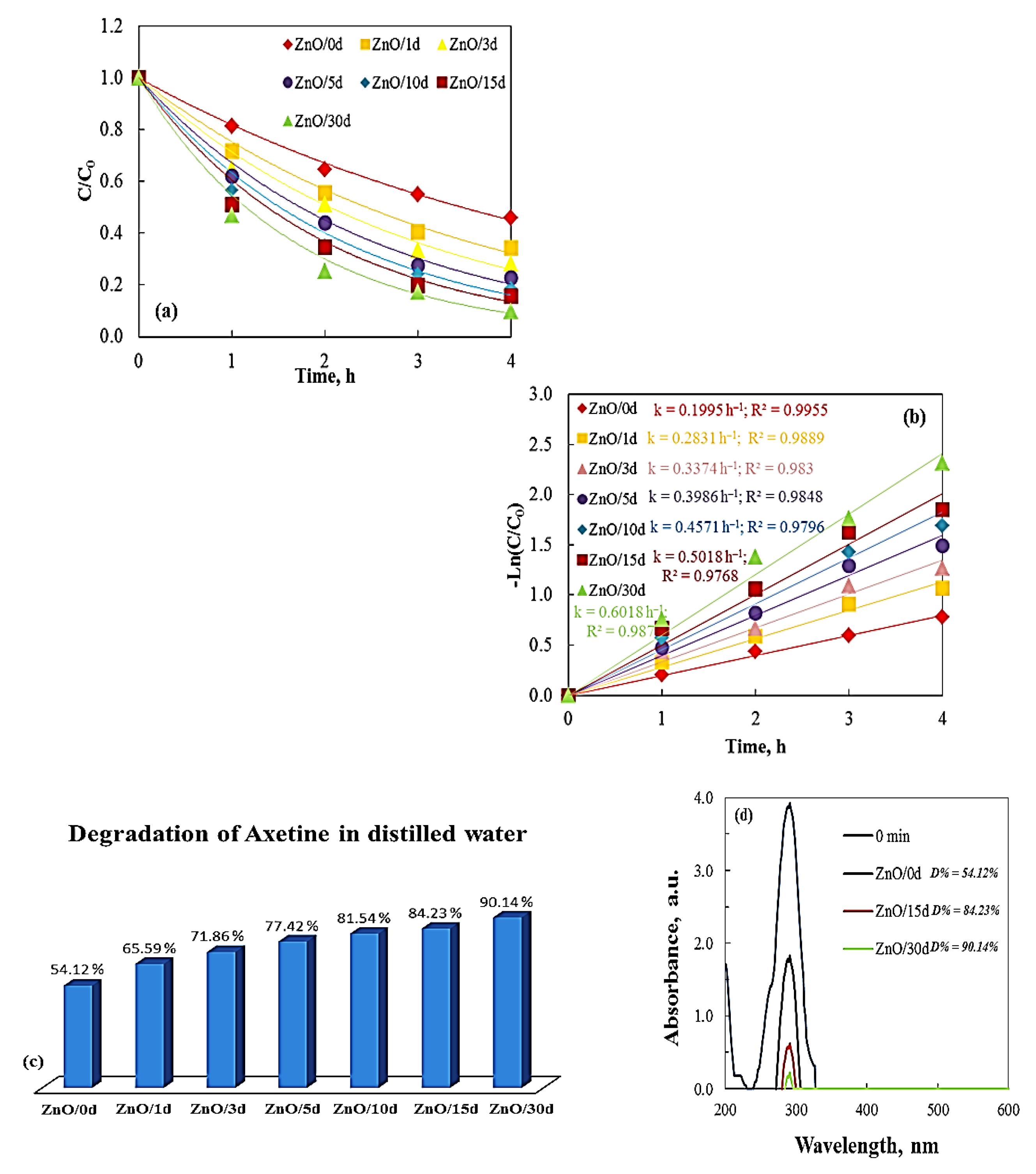

3.2. Photocatalytic Activity of Sol–Gel ZnO Films—Effect of Sol Aging Time

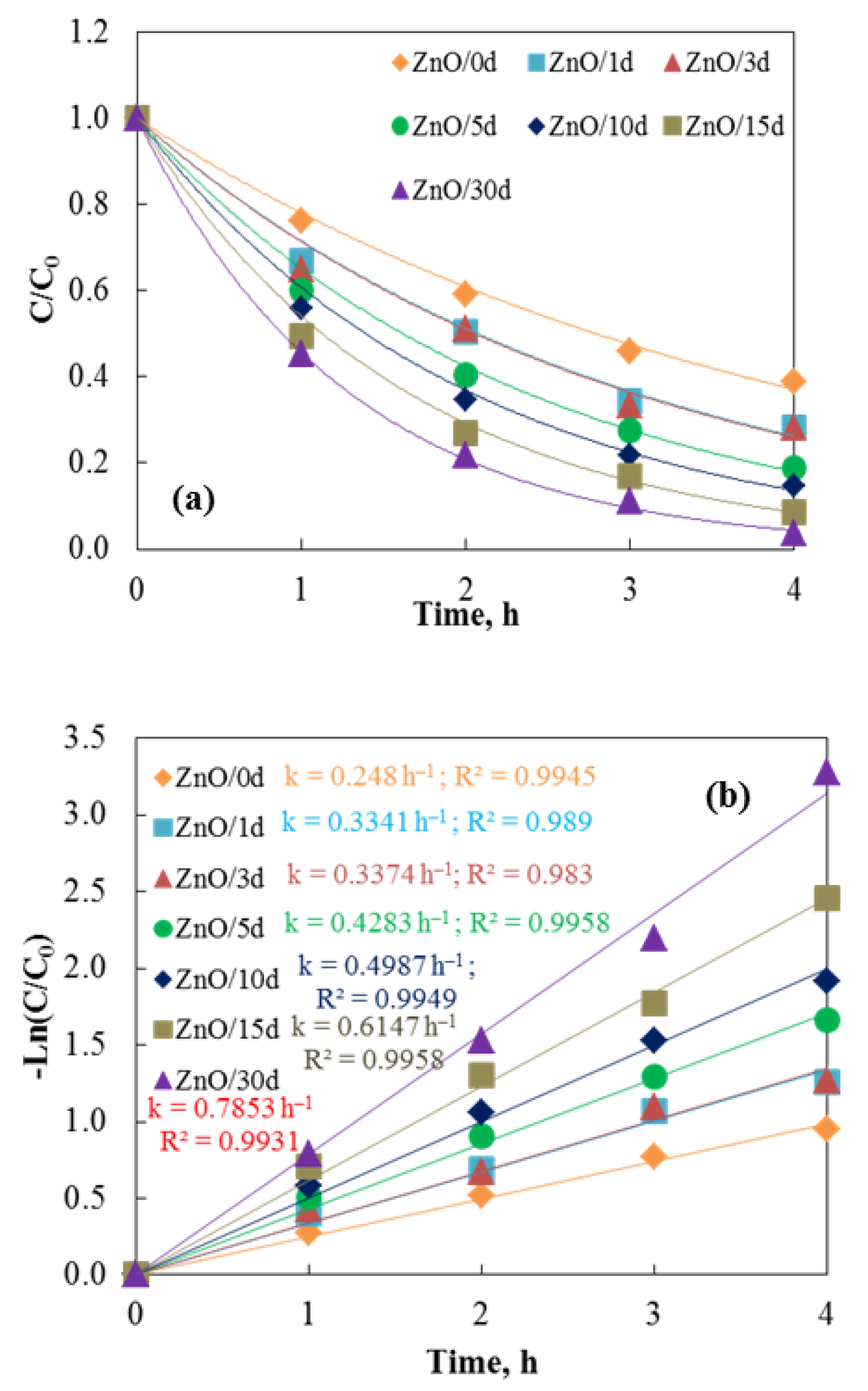

3.3. Photocatalytic Activity of Sol–Sel ZnO Films—Tap Water’s Impact

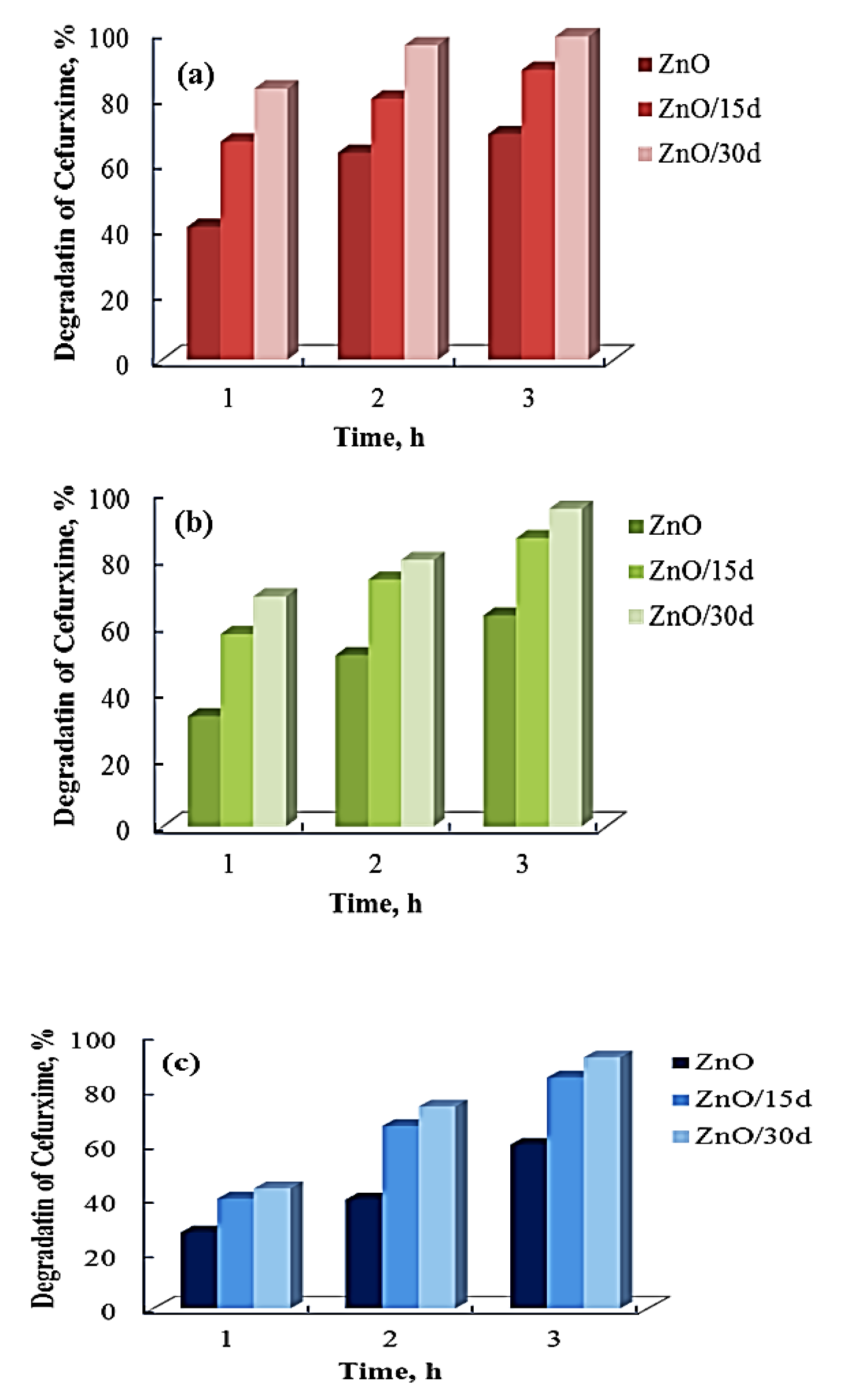

3.4. Photocatalytic Activity of Sol–Gel ZnO Films—Effect of Initial Concentration of Drug

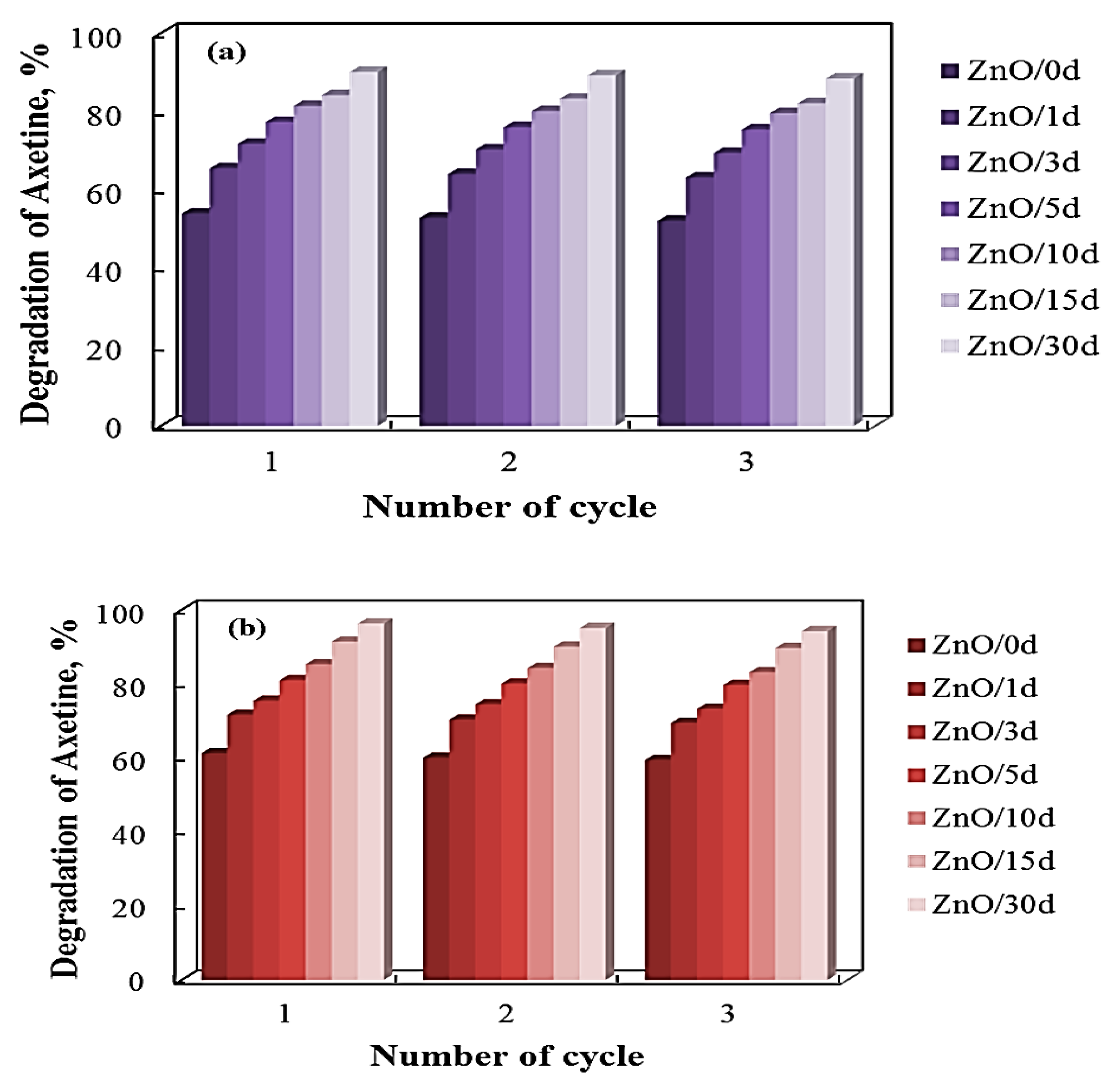

3.5. Photocatalytic Efficiency of Sol–Gel ZnO Films—Effect of Photostability

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matheen, I.; Tajudeen, S.; Raza, A. Efficient photocatalytic degradation of cefuroxime and tetracycline antibiotics using a novel triazine based covalent organic framework grafted with Cu/CuO nanoparticles. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 181, 115262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, A.; Alneghery, L.; Al-Zharani, M.; Nasr, F.; Jawad, S.; Umer, M.; Sayyed, R.; Ilyas, N. An insight into the impacts of pharmaceutical pollutants on the ecosystem and the potential role of bioremediation in mitigating pharmaceutical pollutants. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 680, 125791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, N.; Leibovitz, E.; Dagan, R.; Leiberman, A. Acute otitis media-diagnosis and treatment in the era of antibiotic resistant organisms: Updated clinical practice guidelines. Int. J. Ped. Otorhin. 2005, 69, 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Zhou, B.; Lv, B. Antibacterial Therapeutic Agents Composed of Functional Biological Molecules. J. Chem. 2020, 2020, 6578579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Infection Association. The epidemiology, prevention, investigation and treatment of Lyme borreliosis in United Kingdom patients: A position statement by the British Infection Association. J. Infect. 2011, 62, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, C. Cephalosporin in the management of children with acute otitis media. Int. J. Health Sci. 2021, 5, 14104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snodgrass, A.; Motaparthi, K. 9-Systemic Antibacterial Agents. Comp. Dermatol. Drug Ther. 2021, 69–98.e13. [Google Scholar]

- Mergenhagen, K.A.; Wattengel, B.A.; Skelly, M.K.; Clark, C.M.; Russo, T.A. Fact versus Fiction: A Review of the Evidence behind Alcohol and Antibiotic Interactions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, L.; Meric, S.; Kassinos, D.; Guida, M.; Russo, F.; Belgiorno, V. Degradation of diclofenac by TiO2 photocatalysis: UV absorbance kinetics and process evaluation through a set of toxicity bioassays. Water Res. 2009, 43, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreozzi, R.; Caprio, V.; Marotta, R.; Vogna, D. Paracetamol oxidation from aqueous solutions by means of ozonation and H2O2/UV system. Water Res. 2003, 37, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzarti, Z.; Saadi, H.; Abdelmoula, N.; Hammami, I.; Pedro, M.; Graça, F.; Alrasheedi, N.; Louhichi, B.; Seixas de Melo, J. Enhanced dielectric and photocatalytic properties of Li-doped ZnO nanoparticles for sustainable methylene blue degradation with reduced lithium environmental impact. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 47170–47184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resmi, V.; Soney, J.; Dhannia, T. Photocatalytic activity of ZnO nanoparticle and ZnO-TiO2 nanocomposite synthesized using egg-white mediated co-precipitation technique with microwave irradiation. Opt. Mater. 2025, 168, 117440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Misra, K.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Samanta, S. A brief review on transition metal ion doped ZnO nanoparticles and its optoelectronic applications. Mater. Proceed. 2021, 43, 3297–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrouni, A.; Moussa, M.; Fessi, N.; Palmisano, N.; Ceccato, R.; Rayes, A.; Parrino, F. Solar Photocatalytic Activity of Ba-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles: The Role of Surface Hydrophilicity. Nanomaterials 2023, 23, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakki, H.; Sillanpää, M. Comprehensive analysis of photocatalytic and photoreactor challenges in photocatalytic wastewater treatment: A case study with ZnO photocatalyst. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2024, 181, 108592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y. Current trends on In2O3 based heterojunction photocatalytic systems in photocatalytic application. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 137804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, D.; Caruso, R. Indium Oxides and Related Indium-based Photocatalysts for Water Treatment: Materials Studied, Photocatalytic Performance, and Special Highlights. Sol. RRL 2021, 5, 2100086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letifi, H.; Dridi, D.; Litaiem, Y.; Ammar, S.; Dimassi, W.; Chtourou, R. High Efficient and Cost Effective Titanium Doped Tin Dioxide Based Photocatalysts Synthesized via Co-precipitation Approach. Catalysts 2021, 11, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nipa, S.T.; Akter, R.; Raihan, A.; Rasul, S.; Som, U.; Ahmed, S.; Alam, J.; Khan, M.; Enzo, S.; Rahman, W. State-of-the-art biosynthesis of tin oxide nanoparticles by chemical precipitation method towards photocatalytic application. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 10871–10893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuan, D.; Ngo, H.; Thi, H.; Chu, T. Photodegradation of hazardous organic pollutants using titanium oxides -based photocatalytic: A review. Environ. Res. 2023, 229, 116000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoai, P.; Huong, N. Latest avenues on titanium oxide-based nanomaterials to mitigate the pollutants and antibacterial: Recent insights, challenges, and future perspectives. Chemosphere 2023, 324, 138372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, I.; Chawla, H.; Chandra, A.; Sagadevan, S.; Garg, S. Advances in the strategies for enhancing the photocatalytic activity of TiO2: Conversion from UV-light active to visible-light active photocatalyst. Inorg. Chem. Comm. 2022, 143, 109700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.; Chaudhri, A. Sol–Gel-Derived Cu-Doped ZnO Thin Films for Optoelectronic Applications. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 21877–21881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Shen, X.; Wang, A. Effect of aging time of ZnO sol on the structural and optical properties of ZnO thin films prepared by sol–gel method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 4543–4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, F. Structural and optical properties of ZnO thin films prepared by sol–gel method with different thickness. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 4031–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badoni, A.; Sharma, R.; Prakash, J. Titanium Dioxide Based Functional Materials for Antibacterial and Antiviral Applications. ACS Publ. 2024, 8, 257–280. [Google Scholar]

- Swathi, S.; Babu, E.; Yuvakkumar, R.; Ravi, G.; Chinnathambi, A.; Alharbi, S.; Velauthapillai, D. Branched and unbranched ZnO nanorods grown via chemical vapor deposition for photoelectrochemical water-splitting applications. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 9785–9790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, N.; Straube, B.; Marin-Ramirez, O.; Comedi, D. Low temperature chemical vapor deposition as a sustainable method to obtain c-oriented and highly UV luminescent ZnO thin films. Mater. Lett. 2023, 333, 133684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshoaibi, A. The Influence of Annealing Temperature on the Microstructure and Electrical Properties of Sputtered ZnO Thin Films. Inorganics 2024, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Ke, J.; Hao, J.; Yan, X.; Tian, Y. A new method for synthesis of ZnO flower-like nanostructures and their photocatalytic performance. Phys. Cond. Matter. 2022, 624, 413395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, B.; Kakhia, M.; Obaide, A. Morphological and Structural Studies of ZnO Nanotube Films Using Thermal Evaporation Technique. Plasmonics 2021, 16, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeid, S.; Leprince-Wang, Y. Advancements in ZnO-Based Photocatalysts for Water Treatment: A Comprehensive Review. Crystals 2024, 14, 611. [Google Scholar]

- Yavaş, A.; Güler, S.; Erol, M. Growth of ZnO nanoflowers: Effects of anodization time and substrate roughness on structural, morphological, and wetting properties. J. Australas. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 56, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speaks, D.T. Effect of concentration, aging, and annealing on sol gel ZnO and Al-doped ZnO thin films. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Eng. 2020, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahroug, A.; Mahroug, I.; Berra, S.; Allali, D.; Hamrit, S.; Guelil, A.; Zoukel, A.; Ullah, S. Optical, luminescence, photocurrent and structural properties of sol-gel ZnO fibrous structure thin films for optoelectronic applications: A combined experimental and DFT study. Opt. Mater. 2023, 142, 114043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimifard, R.; Abdizadeh, H.; Golobostanfard, M.R. Controlling the extremely preferred orientation texturing of sol–gel derived ZnO thin films with sol and heat treatment parameters. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2020, 93, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmi, M.; Carturan, G. Precursors for sol-gel preparations. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1988, 100, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jin, Z.; Li, W.; Qiu, J. Preparation of ZnO porous thin films by sol–gel method using PEG template. Mater. Lett. 2005, 59, 3620–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullity, B.; Stock, S. Elements of X-Ray Diffraction, 2nd ed.; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2001; p. 388. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullin, K.; Gabdullin, M.; Zhumagulov, S.; Ismailova, G.; Gritsenko, L.; Kedruk, Y.; Mirzaeian, M. Stabilization of the Surface of ZnO Films and Elimination of the Aging Effect. Materials 2021, 14, 6535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folawewo, A.; Bala, M. Nanocomposite Zinc Oxide-Based Photocatalysts: Recent Developments in Their Use for the Treatment of Dye-Polluted Wastewater. Water 2022, 14, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathollahi, V.; Amini, M. Sol–gel preparation of highly oriented gallium-doped zinc oxide thin films. Mater. Lett. 2001, 50, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado-Guerra, S.; Olvera, M.; Maldonado, A.; Castaneda, L. Chemically sprayed ZnO: F thin films deposited from diluted solutions: Effect of the time of aging on physical characteristics. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2006, 90, 2346–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozati, S.; Moradi, S.; Golshahi, S.; Martins, R.; Fortunato, E. Electrical, structural and optical properties of fluorine-doped zinc oxide thin films: Effect of the solution aging time. Thin Solid. Films 2009, 518, 1279–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toubane, M.; Tala-Ighil, R.; Bensouici, F.; Bououdina, M.; Cai, W.; Liu, S.; Souier, M.; Iratni, A. Structural, optical and photocatalytic properties of ZnO nanorods: Effect of aging time and number of layers. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 9673–9685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchuweni, E.; Sathiaraj, T.; Nyakotyo, H. Synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide thin films for optoelectronic applications. Heliyon 2017, 3, e00285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankove, J. Optical processes in semiconducting thin films. Thin Solid. Films 1982, 80, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Basak, D.; Fujihara, S. Effect of substrate-induced strain on the structural, electrical, and optical properties of polycrystalline ZnO thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 96, 2689–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikant, V.; Clarke, D. Optical absorption edge of ZnO thin films: The effect of substrate. J. Appl. Phys. 1997, 81, 6357–6364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, T.; Santhoshkumar, M. Effect of thickness on structural, optical and electrical properties of nanostructured ZnO thin films by spray pyrolysis. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 4579–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taunk, P.; Das, R.; Bisen, D.; Tamrakar, R. Structural characterization and photoluminescence properties of zinc oxide nano particles synthesized by chemical route method. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2015, 8, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, B.; Jazmati, A.; Refaai, R. Oxygen effect on structural and optical properties of ZnO thin films deposited by rf magnetron sputtering. Mater. Res. 2016, 20, 0478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, B.; Zetoun, W.; Tello, A. Deposition of ZnO thin films with different powers using RF magnetron sputtering method: Structural, electrical and optical study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akazawa, H. Photoluminescence studies of transparent conductive ZnO films to identify their donor species. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 045202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprile, C.; Corma, A.; García, H. Enhancement of the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 through spatial structuring and particle size control: From subnanometric to submillimetric length scale. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, B.; Jeyadharmarajan, J.; Chinnaiyan, P. Novel organic assisted Ag-ZnO photocatalyst for atenolol and acetaminophen photocatalytic degradation under visible radiation: Performance and reaction mechanism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 39637–39647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Lu, X.; Xu, W.; Gong, Q.; Ding, J.; Dan, B.; Xie, P. Removal of acetaminophen in the Fe2+/persulfate system: Kinetic model and degradation pathways. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 358, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Alwared, A. Photocatalytic continuous degradation of pharmaceutical pollutants by zeolite/Fe3O4/CuS/CuWO4 nanocomposite under direct sunlight. Res. Eng. 2024, 24, 103234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafi, M.; Sapawe, N. Effect of initial concentration on the photocatalytic degradation of remazol brilliant blue dye using nickel catalyst. Mater. Today 2020, 31, 318–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Films | Crystallite a.u. | Microstraine, size | Characteristics of the Crystalline Lattice, Å | R Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO/0 d | 23 nm | 0.7 × 10−3 | a, b = 3.2389 Å c = 5.1924 Å | Rp = 5.46 Rwp = 7.17 Rexp = 0.03 |

| ZnO/10 d | 19 nm | 0.6 × 10−3 | a, b = 3.2424 Å c = 5.1972 Å | Rp = 5.53 Rwp = 7.32 Rexp = 0.03 |

| ZnO/30 d | 16 nm | 0.5 × 10−3 | a, b = 3.2442 Å c = 5.1993 Å | Rp = 5.57 Rwp = 7.39 Rexp = 0.14 |

| Films | Distilled Water k, h−1 D, % | Tap Water k, h−1 D, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO/0 d | 0.1995 | 54.12 | 0.248 | 61.29 |

| ZnO/1 d | 0.2831 | 65.59 | 0.3341 | 71.68 |

| ZnO/3 d | 0.3374 | 71.86 | 0.3374 | 75.45 |

| ZnO/5 d | 0.3986 | 77.42 | 0.4283 | 81.00 |

| ZnO/10 d | 0.4571 | 81.54 | 0.4987 | 85.30 |

| ZnO/15 d | 0.5018 | 84.23 | 0.6147 | 91.40 |

| ZnO/30 d | 0.6018 | 90.14 | 0.7853 | 96.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kaneva, N. Photocatalytic Properties of Sol–Gel Films Influenced by Aging Time for Cefuroxime Decomposition. Crystals 2026, 16, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010008

Kaneva N. Photocatalytic Properties of Sol–Gel Films Influenced by Aging Time for Cefuroxime Decomposition. Crystals. 2026; 16(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaneva, Nina. 2026. "Photocatalytic Properties of Sol–Gel Films Influenced by Aging Time for Cefuroxime Decomposition" Crystals 16, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010008

APA StyleKaneva, N. (2026). Photocatalytic Properties of Sol–Gel Films Influenced by Aging Time for Cefuroxime Decomposition. Crystals, 16(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010008