Vanadium is a vital resource for multiple sectors, including metallurgy, defense, energy, and the chemical sectors [

1,

2,

3]. This strategic resource plays an essential role in steel manufacturing, alloy materials [

4], and energy storage [

5]. It is the steel industry that utilizes nearly 85% of the world’s vanadium output. In steel manufacturing, vanadium combines with carbon to form second-phase particles, inhibiting austenite grain recrystallization and improving steel’s tempering stability. The introduction of a small amount of vanadium into molten steel can significantly enhance its tensile strength, hardness, fatigue resistance, and toughness [

6,

7,

8]. Vanadium–titanium magnetite is the most important vanadium-bearing resource worldwide [

9]. China possesses abundant vanadium–titanium magnetite resources, which account for about 50% of the national reserves. During the steelmaking process using vanadium–titanomagnetite as the feedstock, vanadium-containing molten iron is oxidized and blown to obtain vanadium slag (V

2O

5 ≥ 12%) as the feedstock for vanadium product manufacturing. Vanadium-bearing steel slag forms in steelmaking when vanadium–titanomagnetite serves as the ore source. There are two pathways through which vanadium partitions into the slag phase, originating from the generation of vanadium-bearing steel slag [

10,

11,

12]: one pathway involves the presence of vanadium as a trace element in the steel slag by blowing. When converting vanadium slag into vanadium-bearing hot metal, approximately 5–10% of the residual vanadium contained in the slag partitions into the semi-refined steel slag, and finally forms vanadium-bearing steel slag with lower grade (V

2O

5 ≈ 1–3%). The other method is to directly convert vanadium-containing hot metal into steel slag and generate vanadium-containing steel slag without converting vanadium slag [

13]. Currently, there is no industrial treatment method for vanadium-containing steel slag, which can only be stockpiled, leading to the waste of land resources and vanadium. Therefore, in response to the national policy requirements of resource conservation and environmental protection, the vanadium extraction from vanadium-bearing steel slag has gradually attracted increasing attention from scientific researchers. Currently, from vanadium-bearing steel slag, vanadium extraction is primarily achieved through two main approaches [

14]. Firstly, via the pyrometallurgical vanadium extraction method. The sintered slag containing vanadium is transferred into the ironmaking furnace for secondary treatment, and is then smelted to produce vanadium-containing hot metal, and the vanadium-enriched high-grade vanadium slag is obtained by oxidation and conversion. The production efficiency is high, but the vanadium recovery efficiency remains low. The second method is the wet vanadium extraction method, which primarily involves water or acid leaching following alkaline salt roasting or leaching in acidic media, following calcium-assisted roasting. This route features a short process flowsheet and enables high vanadium recovery efficiency, and is the main vanadium extraction method at present.

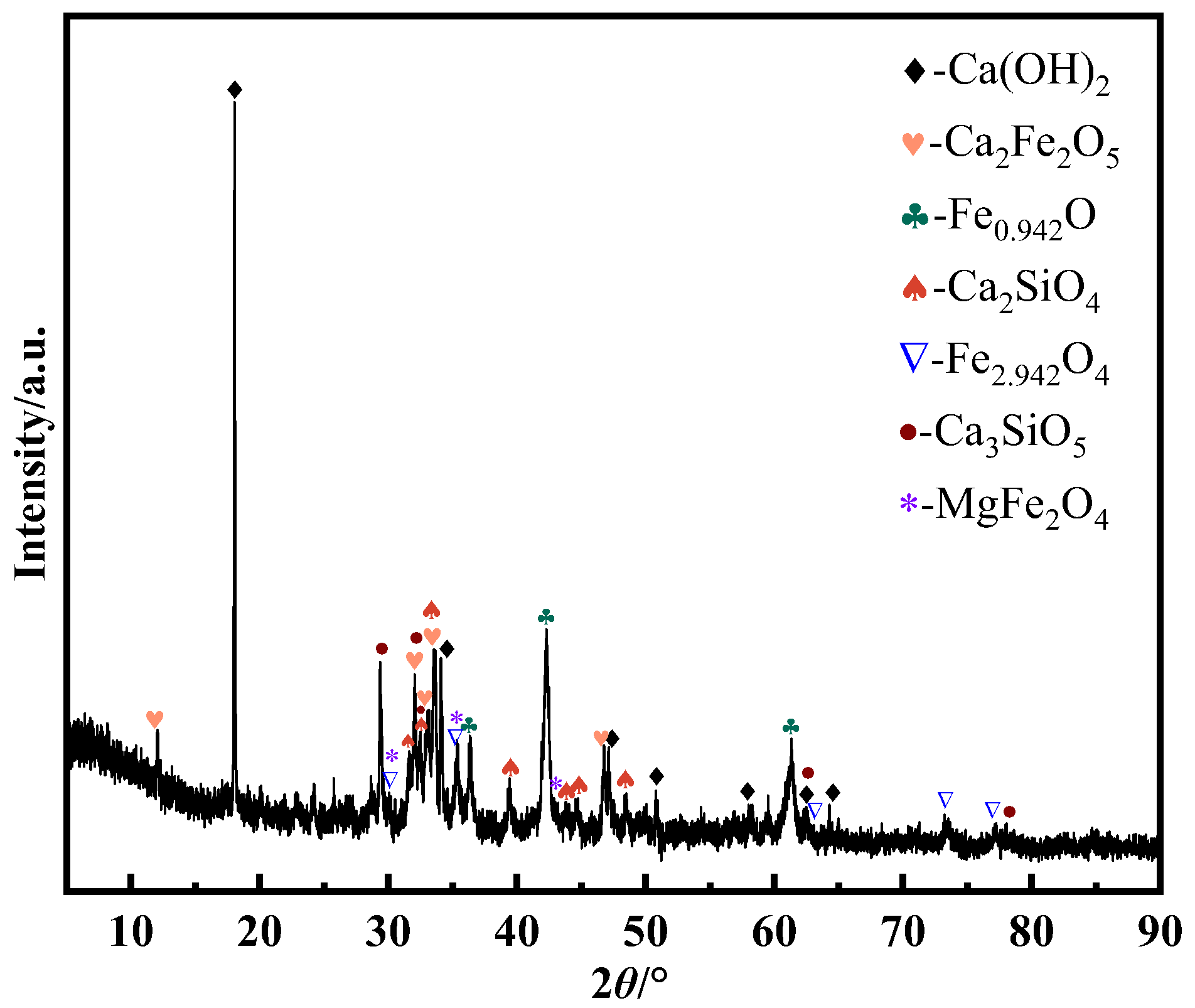

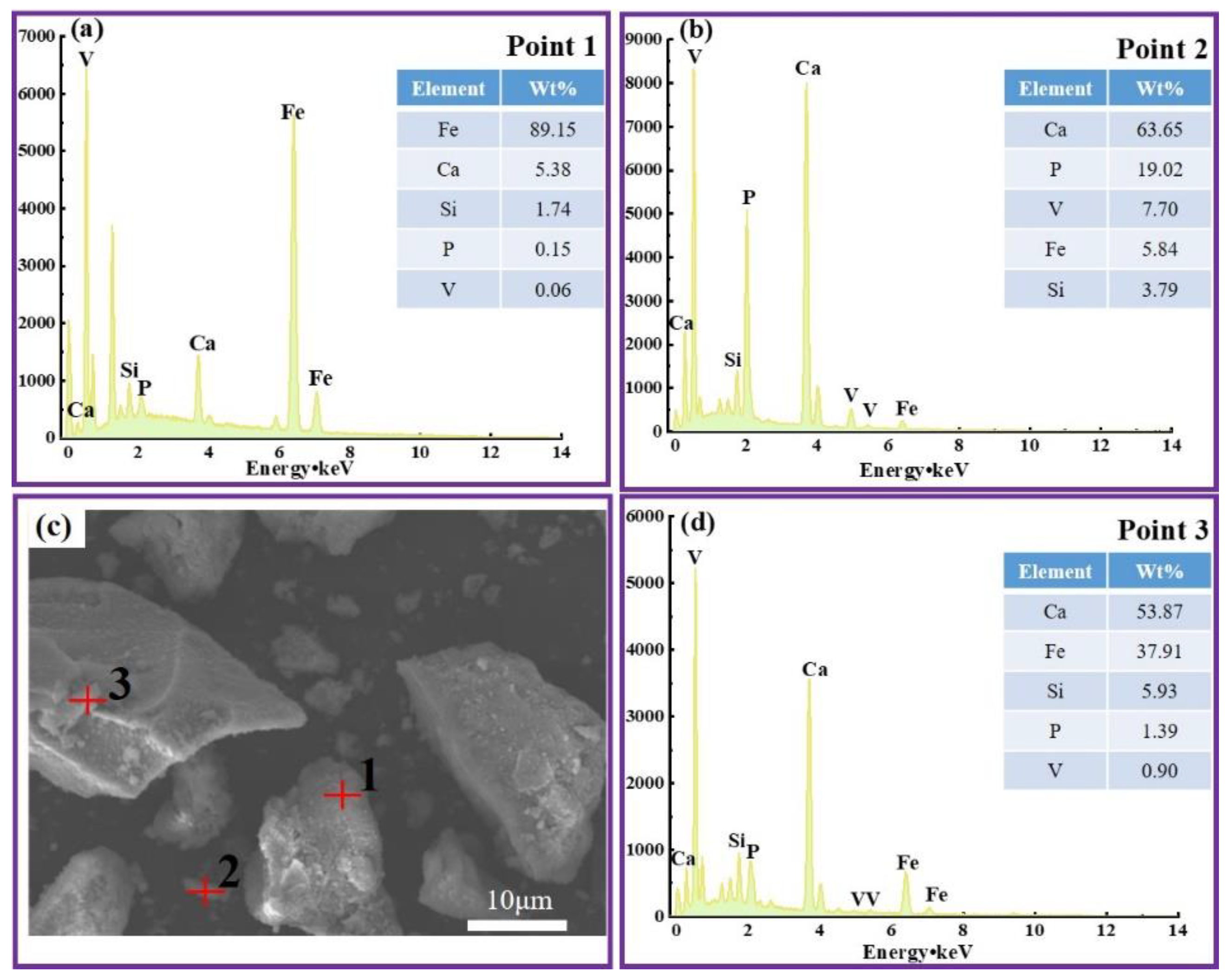

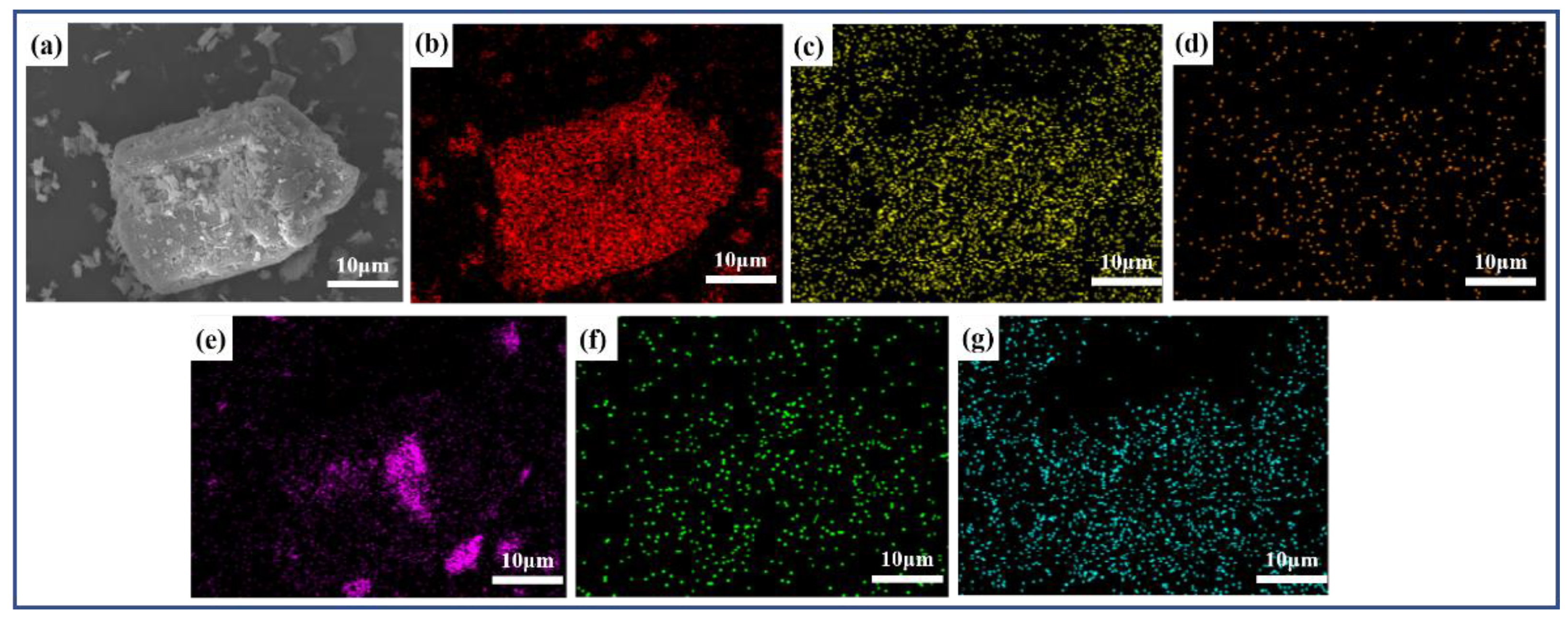

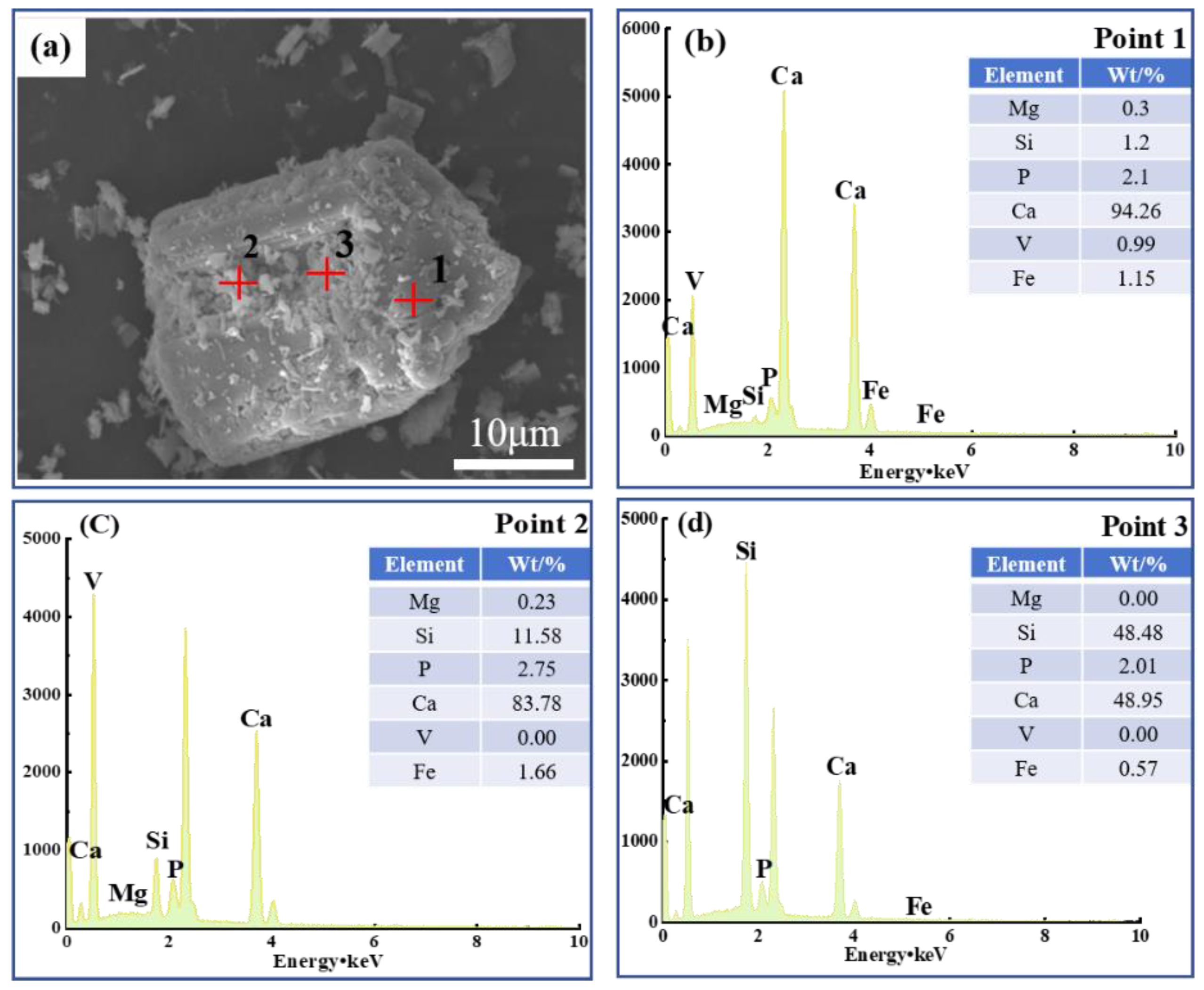

Vanadium predominantly occurs as a peridotite phase encapsulated by ferrovanadium spinel in vanadium-bearing steel slag [

15], both of which hinder the leaching of vanadium [

16,

17]. Generally, alkaline salts are employed for oxidative roasting, enabling the transfer of vanadium in the slag from the spinel phase into acid-soluble vanadate to achieve vanadium extraction. The conventional leaching route uses sodium salt roasting followed by water leaching. Rashchi’s group has proposed a sodium-roasting–acid leaching process [

18]. To obtain a roasting clinker under the same roasting conditions, leach in sulfuric acid solution to obtain vanadium sulfate leaching solution, and the rate of vanadium extraction can be up to 96%. In contrast, this method involves the consumption of a large amount of sodium salt and sulfuric acid per unit of vanadium product, owing to the low vanadium grade in steel slag. Deng et al. [

19] found that low-temperature roasting can avoid the wrapping and sintering phenomenon caused by particles in the high-temperature region. It found that the rate of vanadium leaching can be up to 87.74%. This occurred under 650 °C roasting, a 2 h holding time, a sodium-to-vanadium molar ratio of 0.6, and a Na

2S

2O

8 dosage of 5%. Although the vanadium leaching rate becomes more effective, its harmful gas (Cl

2, SO

2, etc.) emissions seriously pollute the environment [

20,

21], and this method is unsuited to roasting vanadium-bearing steel slag characterized by high calcium levels and low vanadium content. Calcium-containing additives possess sulfur-fixing properties; therefore, roasting with calcium salt could prevent the generation of toxic gases, thereby achieving green production [

22,

23]. Zhang et al. [

24] determined how roasting temperature and leaching conditions influence vanadium leaching rate during calcium roasting-based vanadium extraction. It is found that the vanadium leaching rate exceeds 83% within 30 min when the roasting clinker is placed in dilute sulfuric acid at 55 °C, with a pH value of 2.5. Because the calcium sulfate produced by it is relatively dense, it wraps the vanadium element and hinders the leaching of vanadium; thus, it cannot entirely substitute the conventional sodium salt roasting-based vanadium extraction process [

25]. To enhance the recovery rate of valuable metal elements, microwave-assisted heating leaching is mostly used at present [

26]. In metallurgy, microwave-assisted heating has found widespread application for its efficiency and cleanliness. When using microwave heating during the extraction process, mineral grains develop microcracks as a result of variations in local stress levels. This leads to improved reaction efficiency. Microwaves can contribute to molecular homogenization. Thus, this can lead to an enhanced leaching rate and reaction efficiency when using microwave-assisted leaching. Zhang et al. [

27] examined the extraction of indium from indium-bearing zinc ferrite through conventional and microwave-assisted treatment under identical conditions. Their results demonstrated that a 2.2-times-greater indium extraction rate is achieved using microwave-assisted treatment when compared to methods under conventional heating. Tian et al. [

28] conducted electric heating and microwave heating leaching experiments on converter vanadium slag (V

2O

5 > 15%). It is observed that in the same identical conditions, the rate of vanadium leaching using microwave heating can reach approximately 96%, which is significantly higher than the value achieved under conventional electric heating. Microwave-assisted leaching can promote spinel phase breakdown within converter vanadium slag, decrease grain size, and enhance the rate of vanadium leaching. However, microwave heating technology is mostly used to study converter vanadium slag.

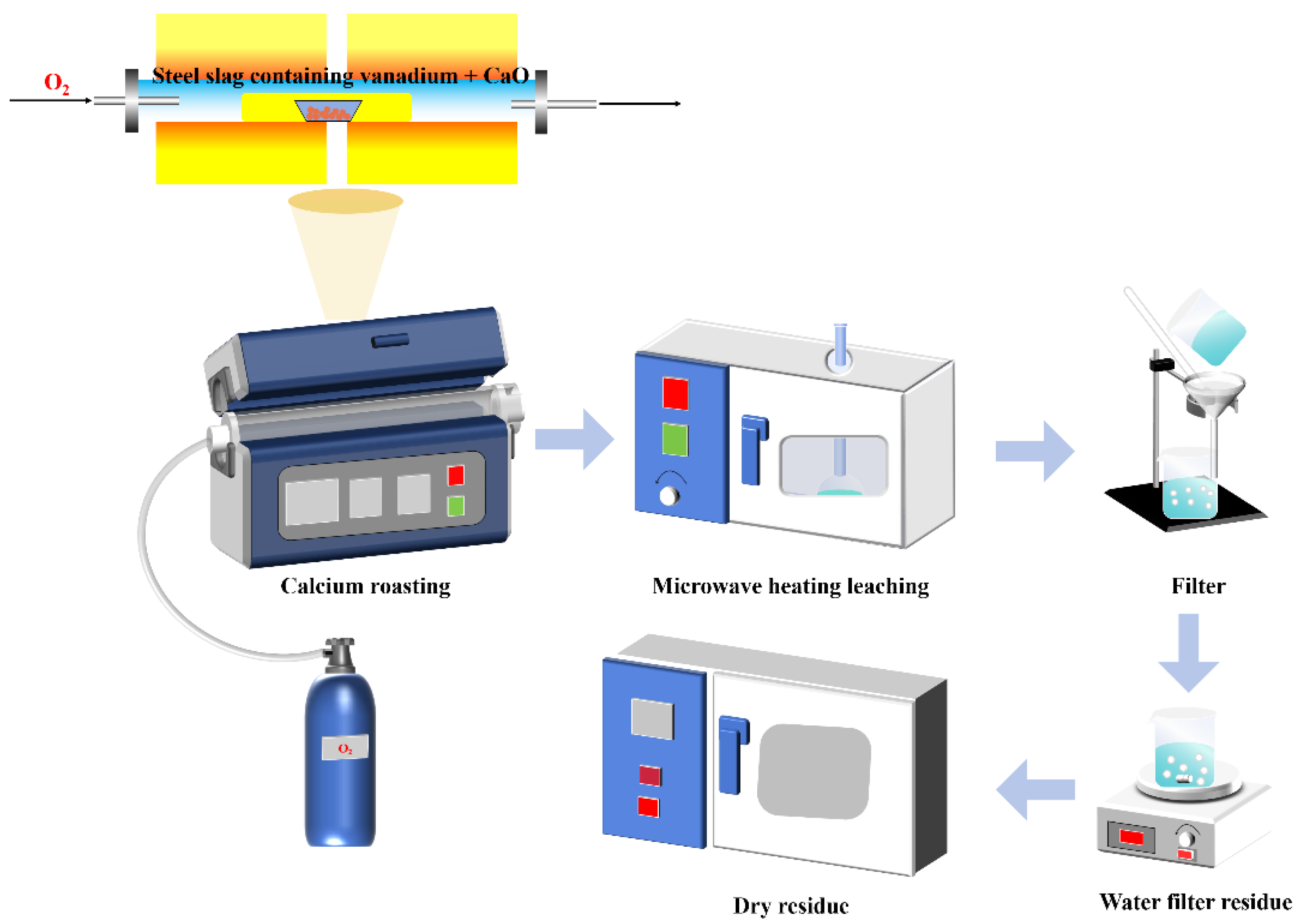

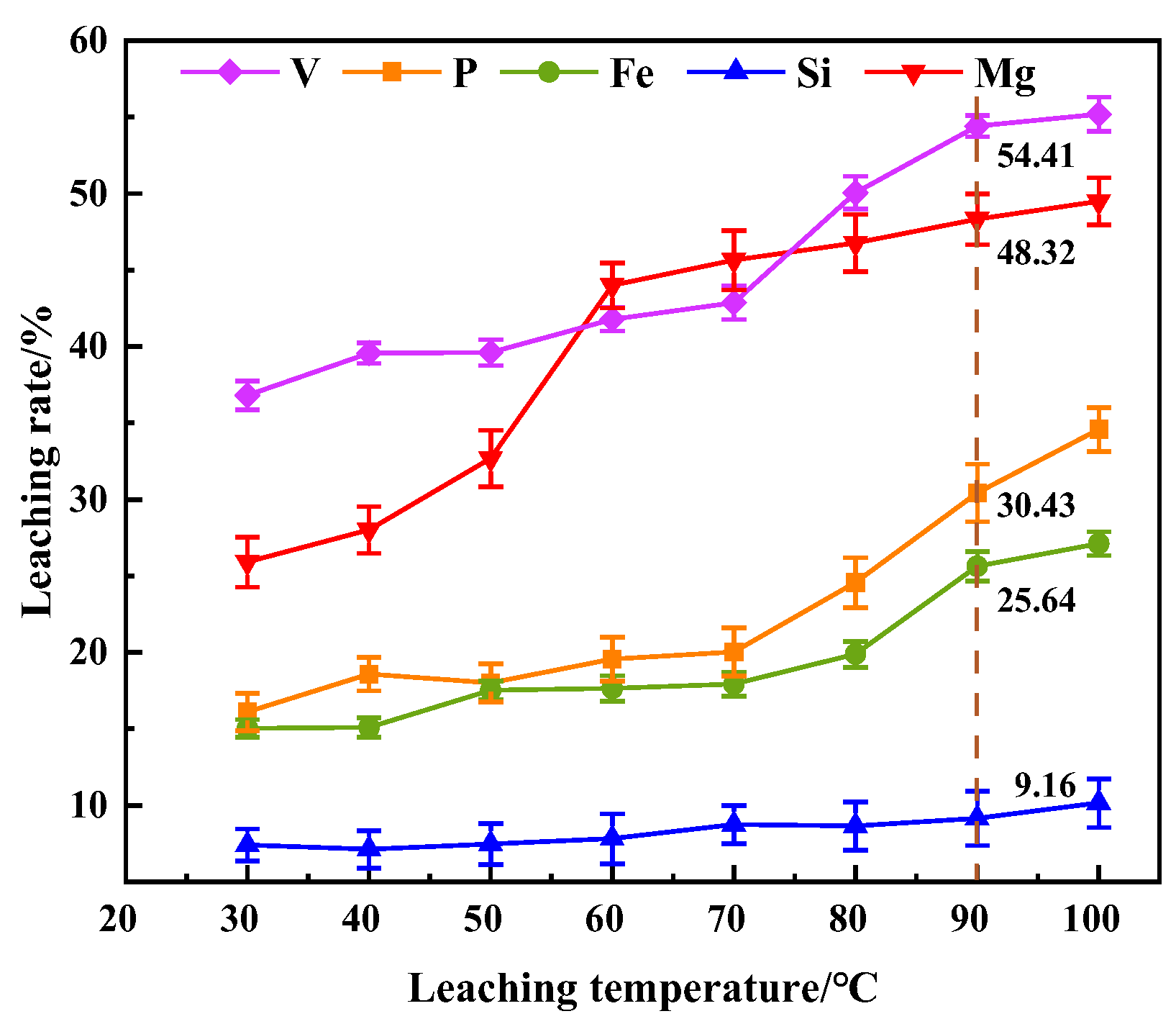

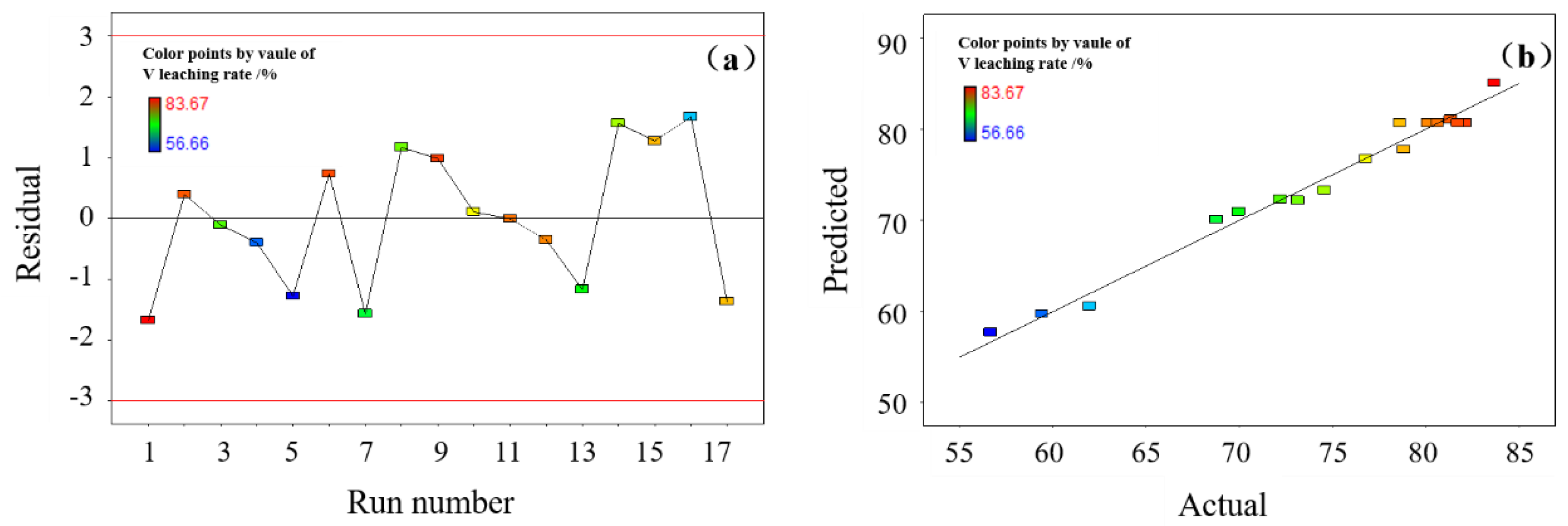

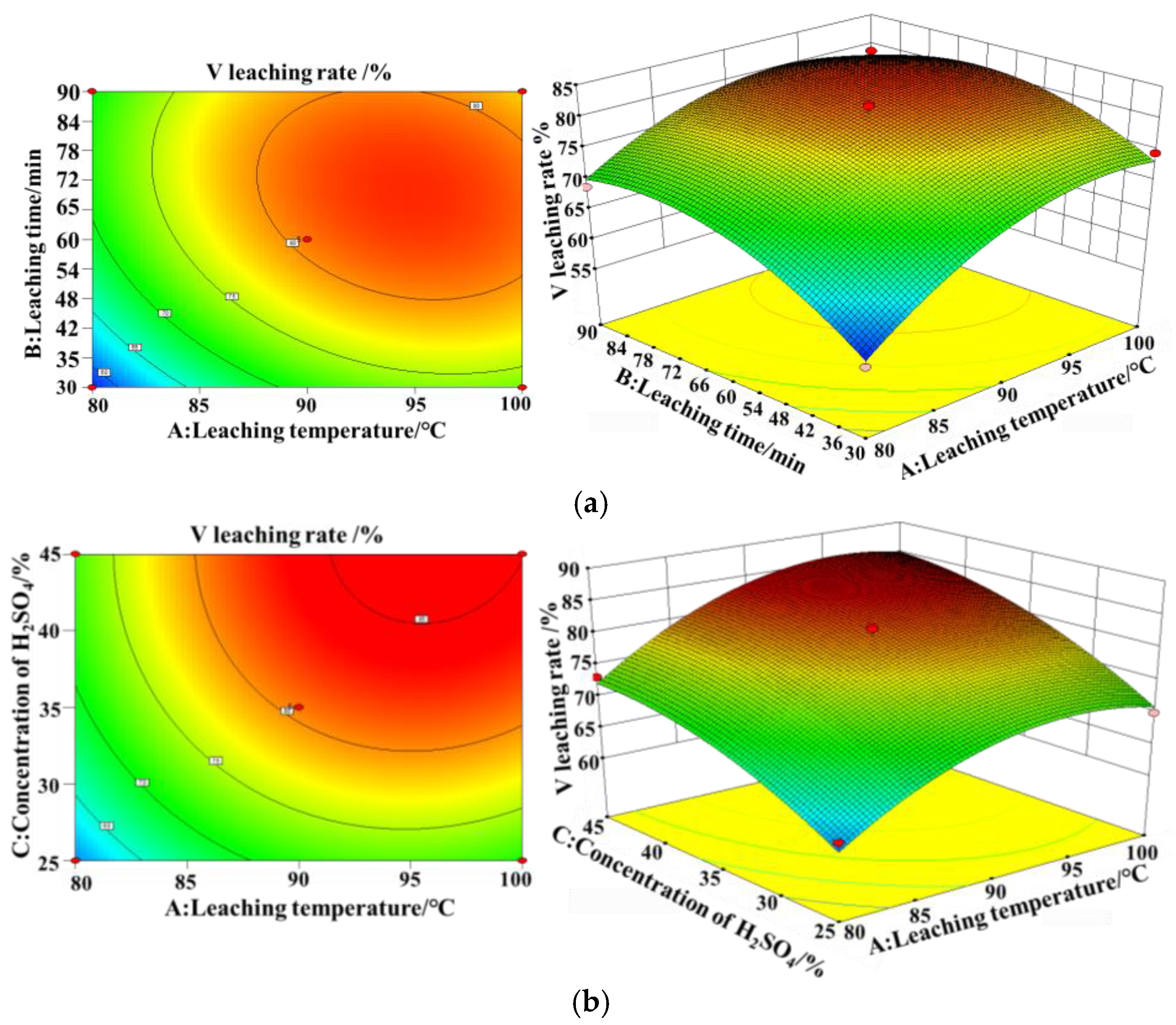

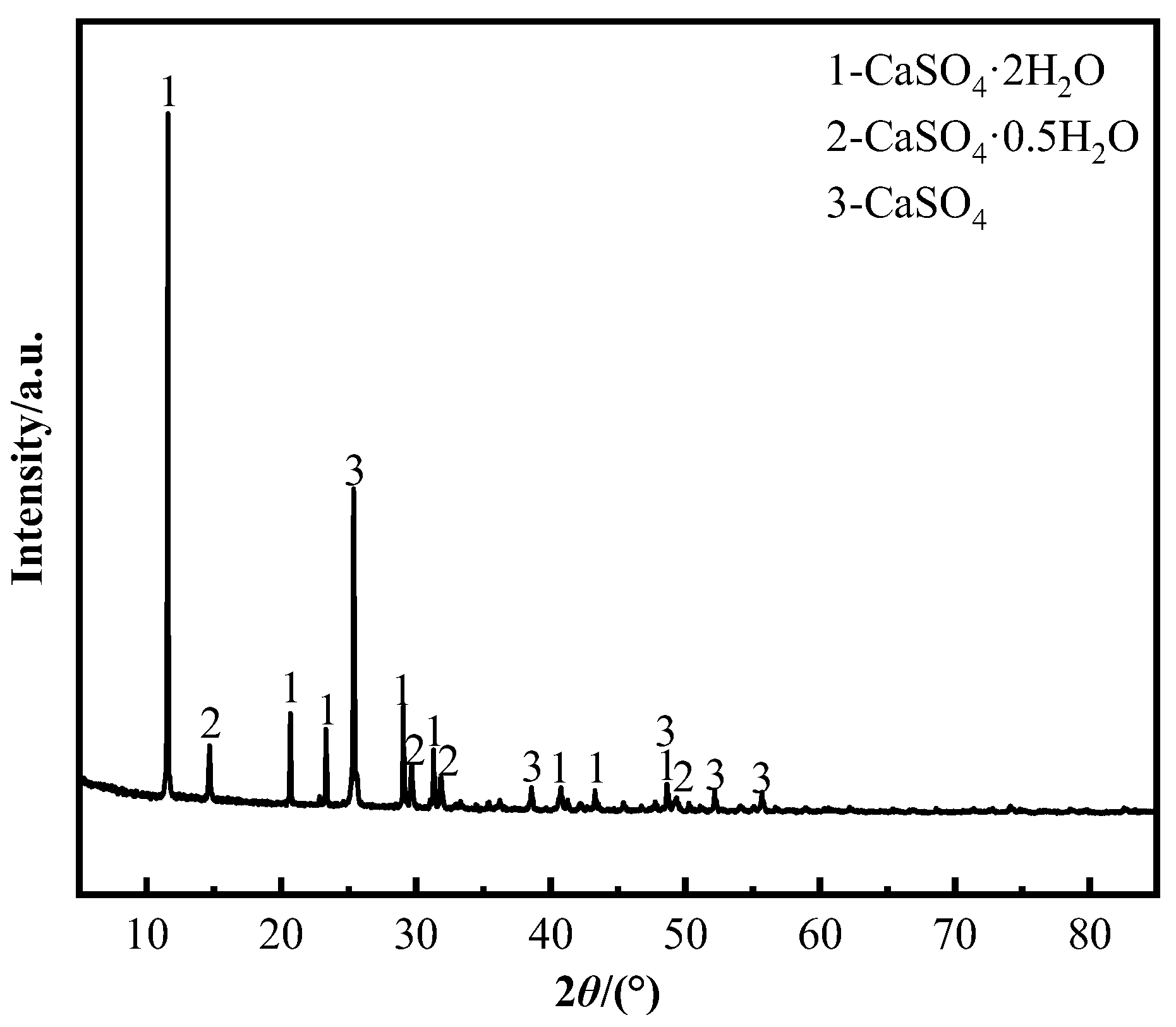

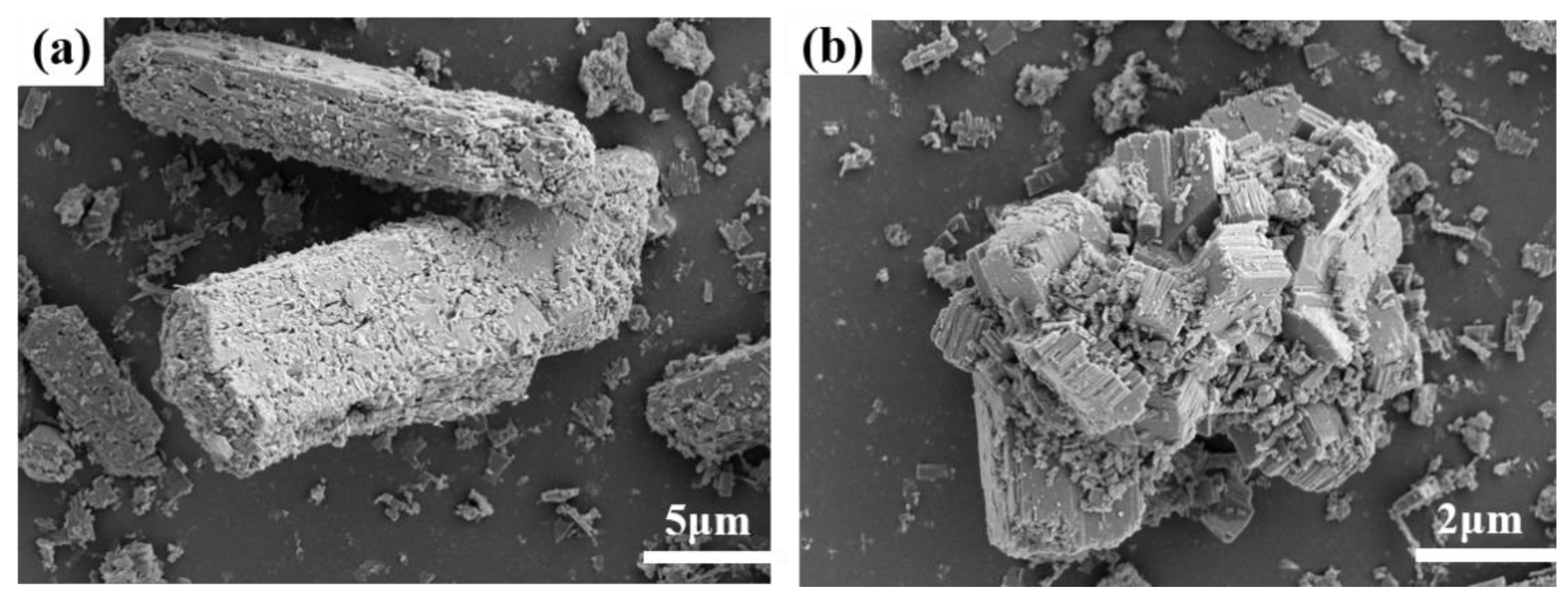

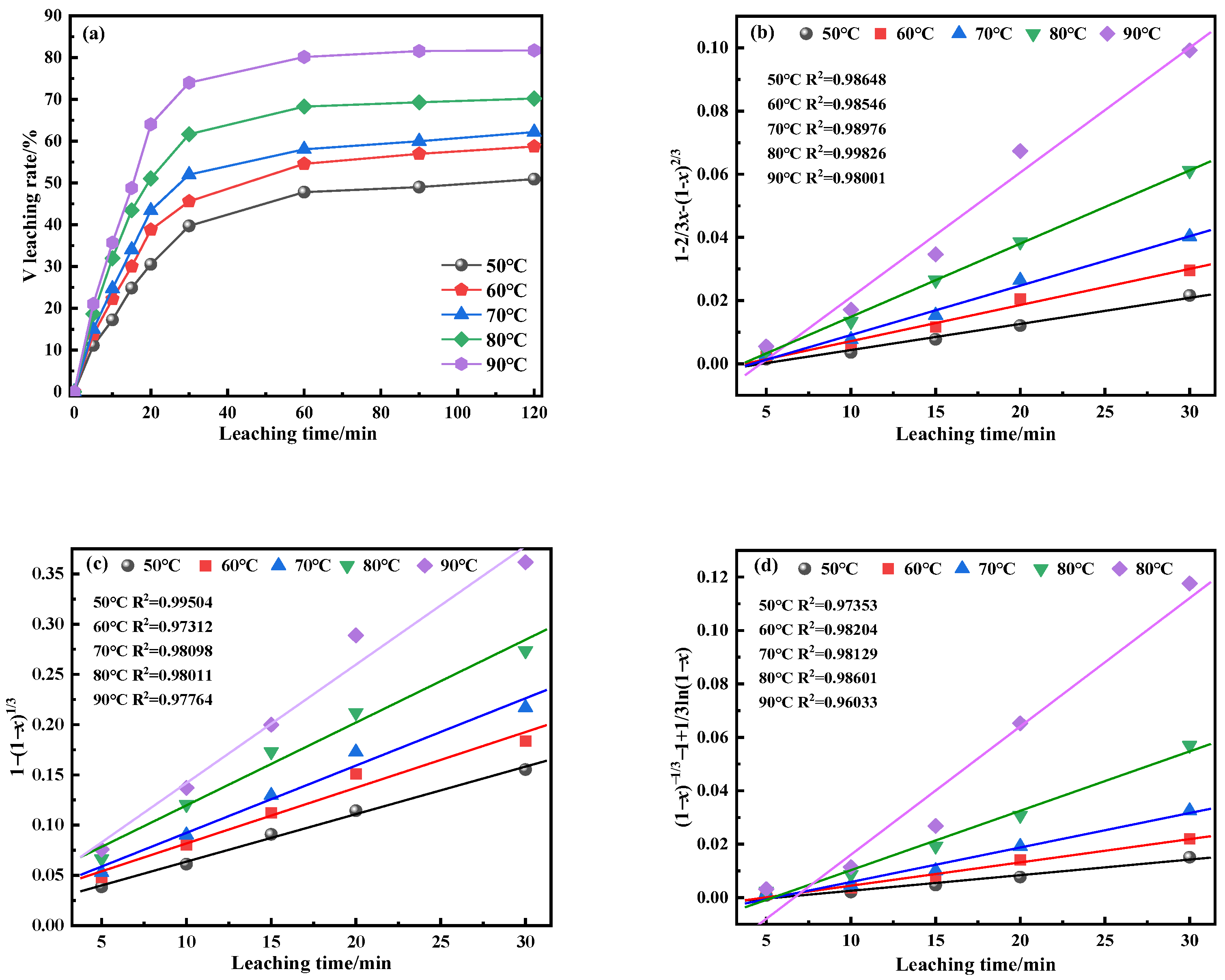

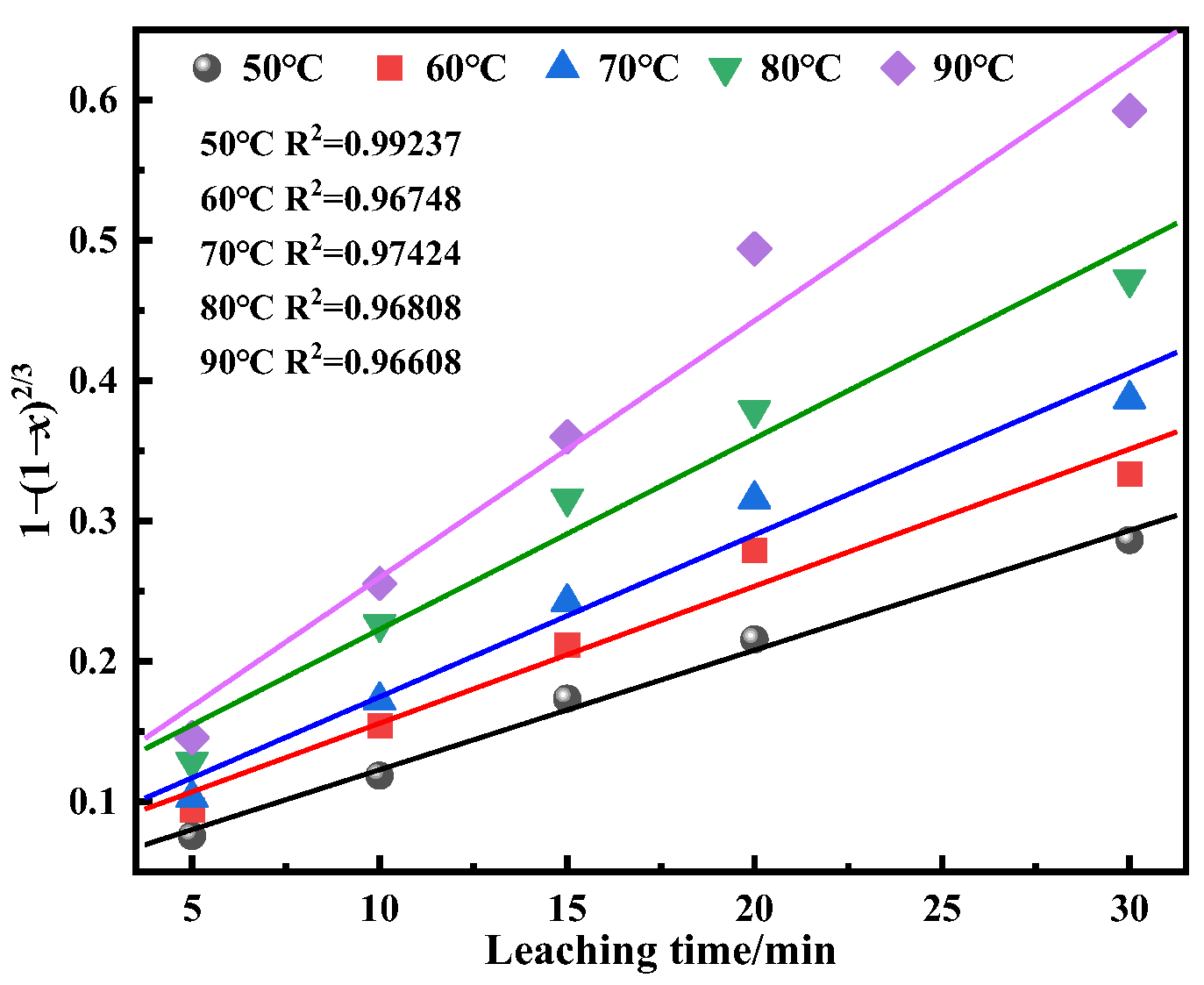

This study investigates a calcination roasting–microwave-assisted acid leaching process for efficient vanadium extraction. Single-factor experiments together with response surface methodology (RSM) are employed to investigate how key operating parameters affect the vanadium leaching rate under microwave-assisted conditions. The process variables are optimized to identify the conditions for maximizing vanadium recovery. Furthermore, the vanadium leaching kinetics of the microwave-assisted vanadium extraction process is analyzed to identify the rate-limiting step and the factors influencing vanadium dissolution behavior. The results offer theoretical understanding and practical guidance for improving vanadium leaching efficiency from steel slag.