Machine Learning for Photocatalytic Materials Design and Discovery

Abstract

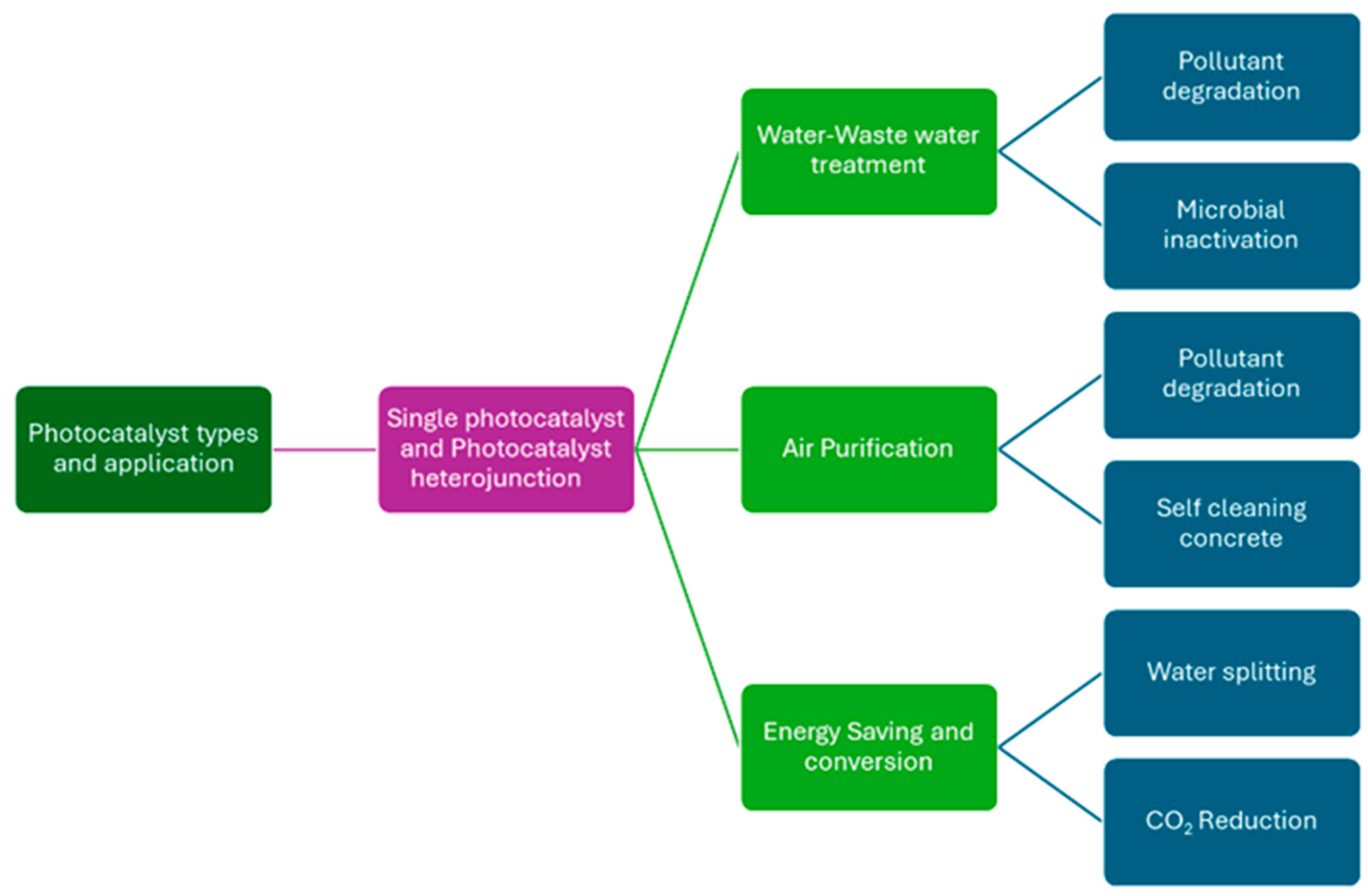

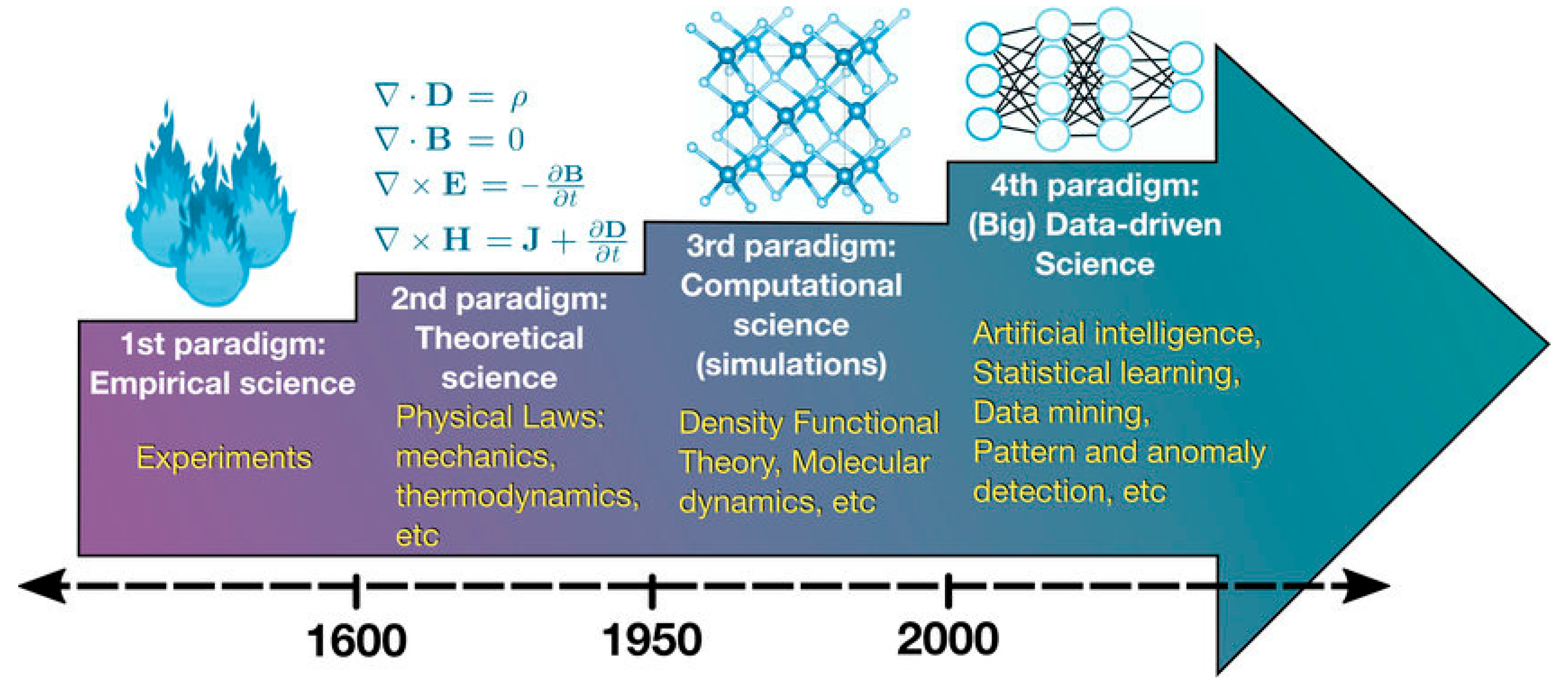

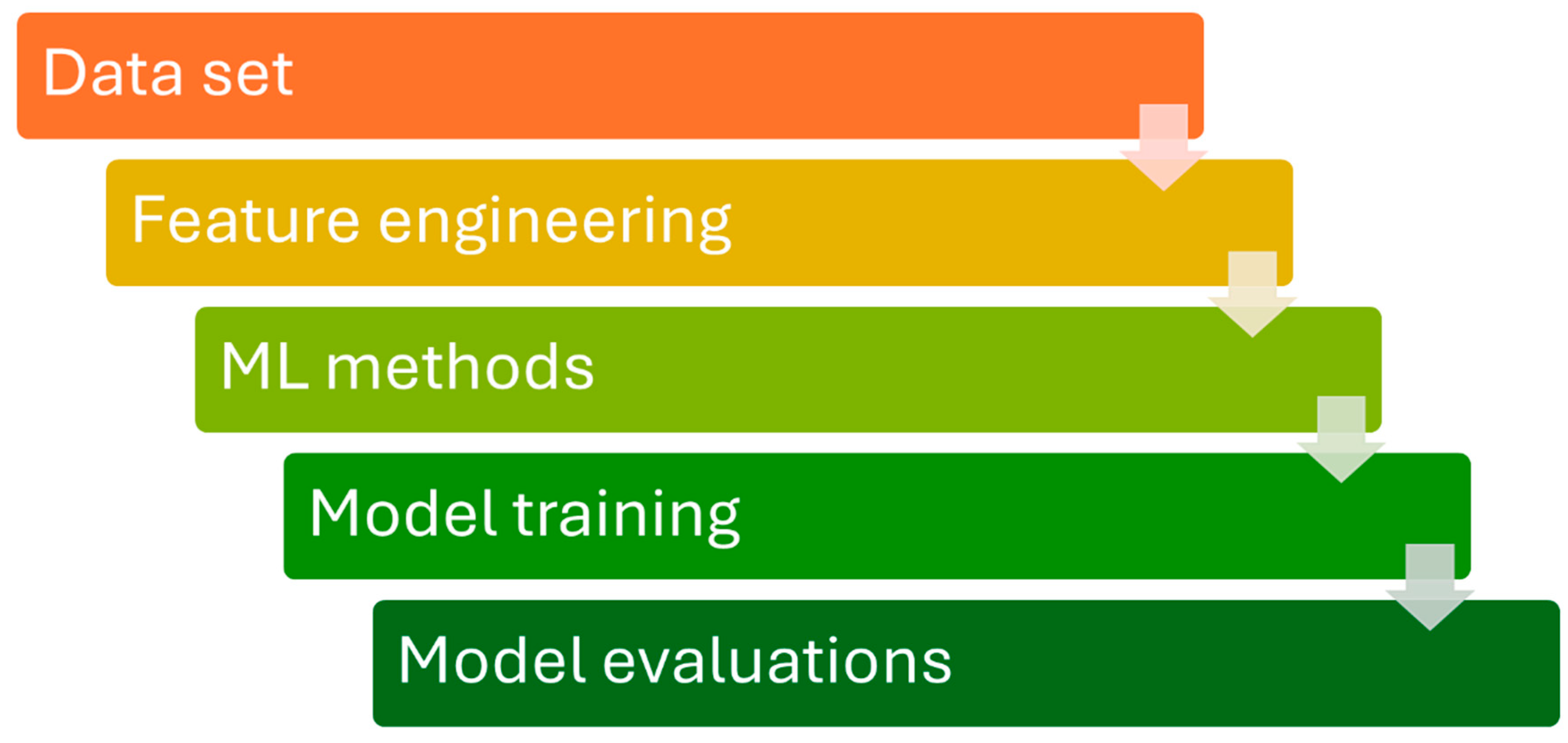

1. Introduction

2. ML-Enhanced Photocatalyst Design Principles and Descriptors

3. Overview of Materials Database

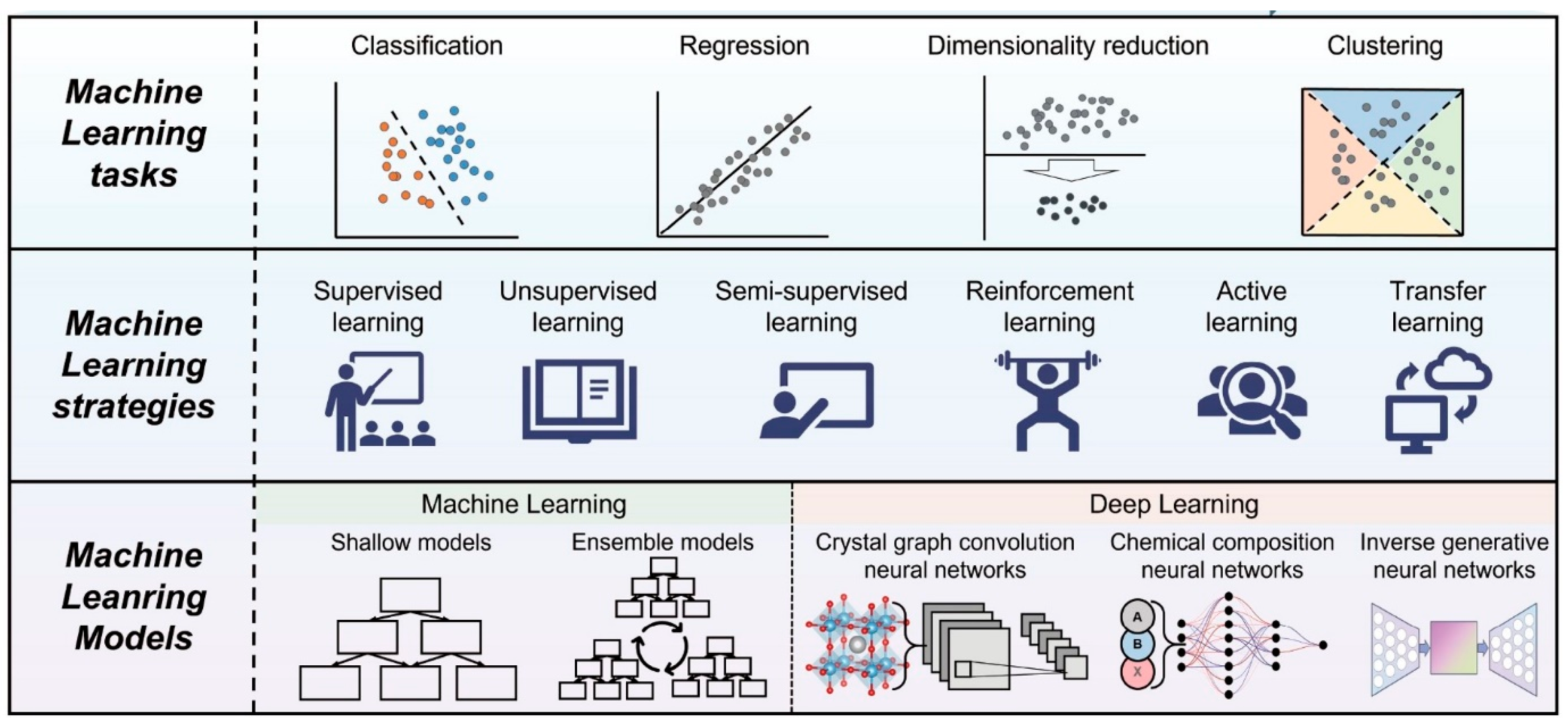

4. Advances in Machine Learning Methods for Photocatalyst Discovery

4.1. Ensemble Methods

4.2. Neural Networks (NNs)

4.3. Graph Neural Networks for Photocatalyst Modelling

4.4. Sparse Gaussian Process Regression for Modelling and Uncertainty

4.5. Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs)

5. Strategies for a Combination of ML Methods for Accelerated Photocatalyst Discovery

6. Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ninduwezuor-Ehiobu, N.; Tula, O.A.; Daraojimba, C.; Ofonagoro, K.A.; Ogunjobi, O.A.; Gidiagba, J.O.; Egbokhaebho, B.A.; Banso, A.A. Exploring innovative material integration in modern manufacturing for advancing U.S. competitiveness in sustainable global economy. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2023, 4, 140–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callister, W.D., Jr.; Rethwisch, D.G. Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-119-72177-2. [Google Scholar]

- Askari, N.; Jamalzadeh, M.; Askari, A.; Liu, N.; Samali, B.; Sillanpaa, M.; Sheppard, L.; Li, H.; Dewil, R. Unveiling the Photocatalytic Marvels: Recent Advances in Solar Heterojunctions for Environmental Remediation and Energy Harvesting. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 148, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, S.; Dewil, R.; Vanierschot, M.; Baeyens, J.; Deng, Y. Water Splitting by MnOx/Na2CO3 Reversible Redox Reactions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Pornrungroj, C.; Linley, S.; Reisner, E. Strategies to Improve Light Utilization in Solar Fuel Synthesis. Nat. Energy 2022, 7, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, P.; Mathew, S.; Clarizia, L.; Kumar, S.R.; Akande, A.; Hinder, S.; Breen, A.; Pillai, S.C. Theoretical and Experimental Investigation of Visible Light Responsive AgBiS2-TiO2 Heterojunctions for Enhanced Photocatalytic Applications. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 253, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shen, S.; Guo, L.; Mao, S.S. Semiconductor-Based Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6503–6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Schoonen, M.A.A. The Absolute Energy Positions of Conduction and Valence Bands of Selected Semiconducting Minerals. Am. Mineral. 2000, 85, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, A.; Miseki, Y. Heterogeneous Photocatalyst Materials for Water Splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, G.; Bian, T.; Zhou, C.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; Wu, L.-Z.; Tung, C.-H.; Smith, L.J.; O’Hare, D.; Zhang, T. Defect-Rich Ultrathin ZnAl-Layered Double Hydroxide Nanosheets for Efficient Photoreduction of CO2 to CO with Water. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 7824–7831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya, J.H.; Seitz, L.C.; Chakthranont, P.; Vojvodic, A.; Jaramillo, T.F.; Nørskov, J.K. Materials for Solar Fuels and Chemicals. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.A.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; Studt, F.; Rossmeisl, J.; Nørskov, J.K. How Copper Catalyzes the Electroreduction of Carbon Dioxide into Hydrocarbon Fuels. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 1311–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paumo, H.K.; Dalhatou, S.; Katata-Seru, L.M.; Kamdem, B.P.; Tijani, J.O.; Vishwanathan, V.; Kane, A.; Bahadur, I. TiO2 Assisted Photocatalysts for Degradation of Emerging Organic Pollutants in Water and Wastewater. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 331, 115458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaie, S.; Vatanpour, V.; Rasoulifard, M.H.; Koyuncu, I. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) Removal by Photocatalysts: A Review. Chemosphere 2022, 306, 135655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermoso, J.; Sánchez, B.; Suarez, S. 5—Air Purification Applications Using Photocatalysis. In Nanostructured Photocatalysts; Boukherroub, R., Ogale, S.B., Robertson, N., Eds.; Micro and Nano Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 99–128. ISBN 978-0-12-817836-2. [Google Scholar]

- Peiris, S.; de Silva, H.B.; Ranasinghe, K.N.; Bandara, S.V.; Perera, I.R. Recent Development and Future Prospects of TiO Photocatalysis. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2021, 68, 738–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanze, K.S.; Kamat, P.V.; Yang, P.; Bisquert, J. Progress in Perovskite Photocatalysis. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 2602–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, X.; Liang, J.; Yuan, X.; Jiang, L.; Yu, H.; Sun, H.; Zhu, Z.; Ye, S.; Tang, N.; et al. Fabrication and Regulation of Vacancy-Mediated Bismuth Oxyhalide towards Photocatalytic Application: Development Status and Tendency. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 443, 214033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusarov, S. Advances in Computational Methods for Modeling Photocatalytic Reactions: A Review of Recent Developments. Materials 2024, 17, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleder, G.R.; Padilha, A.C.M.; Acosta, C.M.; Costa, M.; Fazzio, A. From DFT to Machine Learning: Recent Approaches to Materials Science—A Review. J. Phys. Mater. 2019, 2, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wei, S.-H. Advances and Challenges in DFT-Based Energy Materials Design. Chin. Phys. B 2022, 31, 107105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Chu, X.; Sun, X.-Y.; Xu, K.; Deng, H.-X.; Chen, J.; Wei, Z.; Lei, M. Machine Learning in Materials Science. InfoMat 2019, 1, 338–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunala, S.; Zhai, S.; Wu, F.; Chen, Y.-H. Machine Learning in Photocatalysis: Accelerating Design, Understanding, and Environmental Applications. Sci. China Chem. 2025, 68, 3415–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Iqbal, M.A.; Haider, M.T.; Majeed, A.; Rehman, A.; Iqbal, M.A.; Haider, M.T.; Majeed, A. Artificial Intelligence-Guided Supervised Learning Models for Photocatalysis in Wastewater Treatment. AI 2025, 6, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, A.K. Chemical Hardness-Driven Interpretable Machine Learning Approach for Rapid Search of Photocatalysts. npj Comput. Mater. 2021, 7, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, D.; Xu, P.; Xue, W.; Lei, L.; Cheng, M.; Wang, R.; Liu, X.; Deng, R. Semiconductor-Based Photocatalysts for Photocatalytic and Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting: Will We Stop with Photocorrosion? J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 2286–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Tran, K.; Min, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Dinh, C.-T.; Luna, P.D.; Yu, Z.; Rasouli, A.S.; Brodersen, P.; et al. Accelerated Discovery of CO_2 Electrocatalysts Using Active Machine Learning. Nature 2020, 581, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Ke, Y.; Li, X. Machine Learning Integrated Photocatalysis: Progress and Challenges. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 5795–5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccuglia, P.; Elbert, K.C.; Adler, P.D.F.; Falk, C.; Wenny, M.B.; Mollo, A.; Zeller, M.; Friedler, S.A.; Schrier, J.; Norquist, A.J. Machine-Learning-Assisted Materials Discovery Using Failed Experiments. Nature 2016, 533, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.-M.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Shen, J.; Zhou, M.; Shen, L. High-Throughput Computation and Machine Learning Screening of van Der Waals Heterostructures for Z-Scheme Photocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 5649–5660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabagh Moeini, A.; Shariatmadar Tehrani, F.; Naeimi-Sadigh, A. Machine Learning-Enhanced Band Gaps Prediction for Low-Symmetry Double and Layered Perovskites. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.N.; Anand, R.; Zafari, M.; Ha, M.; Kim, K.S. Progress in Single/Multi Atoms and 2D-Nanomaterials for Electro/Photocatalytic Nitrogen Reduction: Experimental, Computational and Machine Leaning Developments. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2304106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbailò, L.; Fekete, Á.; Ghiringhelli, L.M.; Scheffler, M. The NOMAD Artificial-Intelligence Toolkit: Turning Materials-Science Data into Knowledge and Understanding. npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Ong, S.P.; Hautier, G.; Chen, W.; Richards, W.D.; Dacek, S.; Cholia, S.; Gunter, D.; Skinner, D.; Ceder, G. Commentary: The Materials Project: A Materials Genome Approach to Accelerating Materials Innovation. APL Mater. 2013, 1, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, K.; Thé, J.; Yu, H. Accurate Prediction of Band Gap of Materials Using Stacking Machine Learning Model. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2022, 201, 110899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilania, G.; Balachandran, P.V.; Gubernatis, J.E.; Lookman, T. Learning with Large Databases. In Data-Based Methods for Materials Design and Discovery: Basic Ideas and General Methods; Pilania, G., Balachandran, P.V., Gubernatis, J.E., Lookman, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 59–86. ISBN 978-3-031-02383-5. [Google Scholar]

- Takanabe, K. Photocatalytic Water Splitting: Quantitative Approaches toward Photocatalyst by Design. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 8006–8022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Chu, X.; Xu, K.; Li, H.; Wei, J. Machine Learning-Driven New Material Discovery. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 3115–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsson, T.J.; Hultqvist, A.; García-Fernández, A.; Anand, A.; Al-Ashouri, A.; Hagfeldt, A.; Crovetto, A.; Abate, A.; Ric-ciardulli, A.G.; Vijayan, A.; et al. An Open-Access Database and Analysis Tool for Perovskite Solar Cells Based on the FAIR Data Principles. Nat. Energy 2022, 7, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, Y.J.; Min, K. Extracting Chemical Information from Scientific Literature Using Text Mining: Building an Ionic Conductivity Database for Solid-State Electrolytes. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 18122–18127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannodi-Kanakkithodi, A.; Chan, M.K.Y. Data-Driven Design of Novel Halide Perovskite Alloys. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 1930–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Gong, X.G.; Yin, W.J. Crystal Structure Prediction by Combining Graph Network and Optimization Algorithm. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deekshith, A. Data Engineering for AI: Optimizing Data Quality and Accessibility for Machine Learning Models. Int. J. Manag. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 4, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B.; Wei, X.; Liu, C.; Ban, X.; Huang, H.; Wang, H.; Xue, W.; Wu, S.; Gao, M.; Shen, Q.; et al. Data Augmentation in Microscopic Images for Material Data Mining. npj Comput. Mater. 2020, 6, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damewood, J.; Karaguesian, J.; Lunger, J.R.; Tan, A.R.; Xie, M.; Peng, J.; Gómez-Bombarelli, R. Representations of Materials for Machine Learning. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2023, 53, 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Chen, D.; Jiang, Y.; Nie, Z.; Pan, F. Encoding the Atomic Structure for Machine Learning in Materials Science. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriani, S.A.; Astuti, Y.; Wulandari, I.R. Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) and k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) Algorithm Analysis Based on Feature Selection for Diamond Price Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Seminar on Machine Learning, Optimization, and Data Science (ISMODE), Jakarta, Indonesia, 29–30 January 2022; pp. 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, B.M.S.; Abdulazeez, A.M. A Review of Principal Component Analysis Algorithm for Dimensionality Reduction. J. Soft Comput. Data Min. 2021, 2, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Melo-Pinto, P. T-SNE: A Study on Reducing the Dimensionality of Hyperspectral Data for the Regression Problem of Estimating Oenological Parameters. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2023, 7, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebari, R.; Abdulazeez, A.; Zeebaree, D.; Zebari, D.; Saeed, J. A Comprehensive Review of Dimensionality Reduction Techniques for Feature Selection and Feature Extraction. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends 2020, 1, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chutatape, O. Automated Feature Extraction in Color Retinal Images by a Model Based Approach. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2004, 51, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischl, B.; Binder, M.; Lang, M.; Pielok, T.; Richter, J.; Coors, S.; Thomas, J.; Ullmann, T.; Becker, M.; Boulesteix, A.-L.; et al. Hyperparameter Optimization: Foundations, Algorithms, Best Practices, and Open Challenges. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2023, 13, e1484. Available online: https://wires.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/widm.1484 (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Zhu, H. Hyper-Parameter Optimization: A Review of Algorithms and Applications. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.05689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y.A.; Awwad, E.M.; Al-Razgan, M.; Maarouf, A. Hyperparameter Search for Machine Learning Algorithms for Optimizing the Computational Complexity. Processes 2023, 11, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Gradus, J.L.; Rosellini, A.J. Supervised Machine Learning: A Brief Primer. Behav. Ther. 2020, 51, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentleman, R.; Carey, V.J. Unsupervised Machine Learning. In Bioconductor Case Studies; Hahne, F., Huber, W., Gentleman, R., Falcon, S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 137–157. ISBN 978-0-387-77240-0. [Google Scholar]

- Taha, K. Semi-Supervised and Un-Supervised Clustering: A Review and Experimental Evaluation. Inf. Syst. 2023, 114, 102178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, A.K.; Pillai, G.; Chakrabarty, S. Reinforcement Learning Algorithms: A Brief Survey. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 231, 120495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulac-Arnold, G.; Levine, N.; Mankowitz, D.J.; Li, J.; Paduraru, C.; Gowal, S.; Hester, T. Challenges of Real-World Reinforcement Learning: Definitions, Benchmarks and Analysis. Mach. Learn. 2021, 110, 2419–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.J. Transfer Learning. In Data Classification; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-429-10263-9. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, H. A Decade Survey of Transfer Learning (2010–2020). IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2020, 1, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, F.; Qi, Z.; Duan, K.; Xi, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xiong, H.; He, Q. A Comprehensive Survey on Transfer Learning. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannier, N.; Hudson, S.E.; Koedinger, K.R.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Golinkoff, R.M.; Munakata, Y.; Brownell, S.E. Active Learning: “Hands-on” Meets “Minds-On”. Science 2021, 374, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, I.S.; Gubaev, K.; Podryabinkin, E.V.; Shapeev, A.V. The MLIP Package: Moment Tensor Potentials with MPI and Active Learning. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2020, 2, 025002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.; Linder, F.; Mebane, W.R., Jr. Active Learning Approaches for Labeling Text: Review and Assessment of the Performance of Active Learning Approaches. Political Anal. 2020, 28, 532–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zounemat-Kermani, M.; Batelaan, O.; Fadaee, M.; Hinkelmann, R. Ensemble Machine Learning Paradigms in Hydrology: A Review. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syam, N.; Kaul, R. Random Forest, Bagging, and Boosting of Decision Trees. In Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Marketing and Sales: Essential Reference for Practitioners and Data Scientists; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2021; pp. 139–182. [Google Scholar]

- Okafor, E.; Obada, D.O.; Dodoo-Arhin, D. Ensemble Learning Prediction of Transmittance at Different Wavenumbers in Natural Hydroxyapatite. Sci. Afr. 2020, 9, e00516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharramzadeh Goliaei, E. Photocatalytic Efficiency for CO2 Reduction of Co and Cluster Co2O2 Supported on G-C3N4: A Density Functional Theory and Machine Learning Study. Langmuir 2024, 40, 7871–7882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, H.; Wang, S.; Fan, Y. Machine Learning Predictions of Band Gap and Band Edge for (GaN)1−x(ZnO)x Solid Solution Using Crystal Structure Information. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 7986–7994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Sun, Z.; Lim, K.H.; Gani, T.Z.H.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Yin, H.; Liu, K.; Guo, H.; Du, T.; et al. Emerging Strategies for CO2 Photoreduction to CH4: From Experimental to Data-Driven Design. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2200389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Zhong, S.; Igou, T.; Gao, H.; Li, J.; Chen, Y. Development of Machine Learning Models to Enhance Element-Doped g-C3N4 Photocatalyst for Hydrogen Production through Splitting Water. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 34075–34089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Q.; Nie, H.; Si, H.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Shao, M.; Kang, Z. Highly Efficient Metal-Free Catalyst from Cellulose for Hydrogen Peroxide Photoproduction Instructed by Machine Learning and Transient Photovoltage Technology. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 4000–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabacı, B.; Bakır, R.; Orak, C.; Yüksel, A. Integrating Experimental and Machine Learning Approaches for Predictive Analysis of Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Using Cu/g-C3N4. Renew. Energy 2024, 237, 121737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, J.; He, C.; Zhang, W.; Bai, M. Transition Metals Anchored on Two-Dimensional p-BN Support with Center-Coordination Scaling Relationship Descriptor for Spontaneous Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Nitrogen Reduction. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 652, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Liang, P.; Chen, L. Prediction Model of Type and Band Gap for Photocatalytic g-GaN-Based van Der Waals Heterojunction of Density Functional Theory and Machine Learning Techniques. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 640, 158400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M.; Desai, R.; Mannodi-Kanakkithodi, A. Screening of Novel Halide Perovskites for Photocatalytic Water Splitting Using Multi-Fidelity Machine Learning. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 23177–23188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, F.; Yang, W.; Peng, S.; Zhou, J. A Survey of Convolutional Neural Networks: Analysis, Applications, and Prospects. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 6999–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Konde, A. Fundamentals of Neural Networks. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2021, 9, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, A.M.; Ibrahim, F.S. Comparative Study of Segmentation Techniques for Detection of Tumors Based on MRI Brain Images. Int. J. Biosci. Biochem. Bioinform. 2017, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okasha, N.M.; Mirrashid, M.; Naderpour, H.; Ciftcioglu, A.O.; Meddage, D.P.P.; Ezami, N. Machine Learning Approach to Predict the Mechanical Properties of Cementitious Materials Containing Carbon Nanotubes. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 19, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obada, D.O.; Okafor, E.; Abolade, S.A.; Ukpong, A.M.; Dodoo-Arhin, D.; Akande, A. Explainable Machine Learning for Predicting the Band Gaps of ABX_3 Perovskites. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2023, 161, 107427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, W.A.; Shadid, W.; Castelli, I.E. Machine-Learning Structural and Electronic Properties of Metal Halide Perovskites Using a Hierarchical Convolutional Neural Network. npj Comput. Mater. 2020, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Chen, M.; Fan, J.A. Deep Neural Networks for the Evaluation and Design of Photonic Devices. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 679–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketkar, N.; Moolayil, J. Convolutional Neural Networks. In Deep Learning with Python: Learn Best Practices of Deep Learning Models with PyTorch; Ketkar, N., Moolayil, J., Eds.; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 197–242. ISBN 978-1-4842-5364-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Cui, G.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Sun, M. Graph Neural Networks: A Review of Methods and Applications. AI Open 2020, 1, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q.; Lu, T.; Sheng, Y.; Li, L.; Lu, W.; Li, M. Machine Learning Aided Design of Perovskite Oxide Materials for Photocatalytic Water Splitting. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 60, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Bando, Y.; Wang, X. Unlocking the Potential: Machine Learning Applications in Electrocatalyst Design for Electrochemical Hydrogen Energy Transformation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 11390–11461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Qu, J.; Stevanović, V.; John, P.S.; Gorai, P. Predicting Energy and Stability of Known and Hypothetical Crystals Using Graph Neural Network. Patterns 2021, 2, 100361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z. Automated Graph Neural Networks Accelerate the Screening of Optoelectronic Properties of Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghshenas, Y.; Wong, W.P.; Sethu, V.; Amal, R.; Kumar, P.V.; Teoh, W.Y. Full Prediction of Band Potentials in Semiconductor Materials. Mater. Today Phys. 2024, 46, 101519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solout, M.V.; Ghasemi, J.B. Predicting Photodegradation Rate Constants of Water Pollutants on TiO2 Using Graph Neural Network and Combined Experimental-Graph Features. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hu, W.-J.; Xu, H.-K.; Xu, X.-F.; Chen, X.-Y.; Chen, Z.; Hu, W.-J.; Xu, H.-K.; Xu, X.-F.; Chen, X.-Y. Multi-Task Regression Model for Predicting Photocatalytic Performance of Inorganic Materials. Catalysts 2025, 15, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkhode, P.N.; Awatade, S.M.; Prakash, C.; Shelare, S.D.; Marghade, D.; Gajghate, S.S.; Noor, M.M.; Dennison, M.S. An Integrated AI-Driven Framework for Maximizing the Efficiency of Heterostructured Nanomaterials in Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Zhang, P.; Mehta, K.; Blanchard, A.; Lupo Pasini, M. Scalable Training of Graph Convolutional Neural Networks for Fast and Accurate Predictions of HOMO-LUMO Gap in Molecules. J. Cheminform. 2022, 14, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Su, A.; She, Y.-B.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Exploring Bayesian Optimization for Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2. Processes 2023, 11, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willow, S.Y.; Hajibabaei, A.; Ha, M.; Yang, D.C.; Myung, C.W.; Min, S.K.; Lee, G.; Kim, K.S. Sparse Gaussian Process Based Machine Learning First Principles Potentials for Materials Simulations: Application to Batteries, Solar Cells, Catalysts, and Macromolecular Systems. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2024, 5, 041307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Yasir, M.; Haq, H.U.; Guler, A.C.; Masar, M.; Khan, M.N.A.; Machovsky, M.; Sedlarik, V.; Kuritka, I. Machine Learning Approach for Photocatalysis: An Experimentally Validated Case Study of Photocatalytic Dye Degradation. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 386, 125683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, X. Machine Learning Band Gaps of Doped-TiO2 Photocatalysts from Structural and Morphological Parameters. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 15344–15352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahshoori, I.; Yazdanbakhsh, A.; Baghban, A. Machine Learning-Powered Estimation of Malachite Green Photocatalytic Degradation with NML-BiFeO3 Composites. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghshenas, Y.; Ping Wong, W.; Gunawan, D.; Khataee, A.; Keyikoğlu, R.; Razmjou, A.; Vijaya Kumar, P.; Ying Toe, C.; Masood, H.; Amal, R.; et al. Predicting the Rates of Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution over Cocatalyst-Deposited TiO2 Using Machine Learning with Active Photon Flux as a Unifying Feature. EES Catal. 2024, 2, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anstine, D.M.; Isayev, O. Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials and Long-Range Physics. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulichenko, M.; Nebgen, B.; Lubbers, N.; Smith, J.S.; Barros, K.; Allen, A.E.A.; Habib, A.; Shinkle, E.; Fedik, N.; Li, Y.W.; et al. Data Generation for Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials and Beyond. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 13681–13714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.; He, J.; Shi, X. Construction of High Accuracy Machine Learning Interatomic Potential for Surface/Interface of Nanomaterials—A Review. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2305758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayestehpour, O.; Zahn, S. Efficient Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Deep Eutectic Solvents with First-Principles Accuracy Using Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2023, 19, 8732–8742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, B.; Zhuang, X.; Rabczuk, T.; Shapeev, A.V. Atomistic Modeling of the Mechanical Properties: The Rise of Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials. Mater. Horiz. 2023, 10, 1956–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Dong, E.; Yang, H.; Xi, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, W. Atomic Potential Energy Uncertainty in Machine-Learning Interatomic Potentials and Thermal Transport in Solids with Atomic Diffusion. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, 014108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, O.; Maghsoodi, M.; Jang, S.S.; Snow, S.D. Unveiling Competitive Adsorption in TiO2 Photocatalysis through Machine-Learning-Accelerated Molecular Dynamics, DFT, and Experimental Methods. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 36215–36223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.-Y.; Zhuang, Y.-B.; Cheng, J. Band Alignment of CoO(100)–Water and CoO(111)–Water Interfaces Accelerated by Machine Learning Potentials. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 134110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauceda, H.E.; Chmiela, S.; Poltavsky, I.; Müller, K.-R.; Tkatchenko, A. Molecular Force Fields with Gradient-Domain Machine Learning: Construction and Application to Dynamics of Small Molecules with Coupled Cluster Forces. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 114102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaison, A.; Mohan, A.; Lee, Y.-C. Machine Learning-Enhanced Photocatalysis for Environmental Sustainability: Integration and Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2024, 161, 100880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhou, K.; He, X.; Zhang, L. Methods and Applications of Machine Learning in Computational Design of Optoelectronic Semiconductors. Sci. China Mater. 2024, 67, 1042–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, V.; Phan, R.C.-W.; Ngo, A.C.L.; Krishnasamy, G.; Chai, S.-P. Data-Driven Photocatalytic Degradation Activity Prediction with Gaussian Process. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 161, 848–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Description | Data Size | Link | Institution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFLOW | Computational database of materials | 3.5 m | http://aflowlib.org (accessed on 4 November 2025). | Duke University |

| Materials Project | Computational database of materials | 154 k | https://materialsproject.org (accessed on 4 November 2025). | U.S. Department of Energy |

| OQMD | Computational database of materials | 1 m | http://oqmd.org (accessed on 4 November 2025). | Northwestern University |

| CSD | Database of organic and inorganic materials searched from previous journal publications | 504 k | http://crystallography.net (accessed on 4 November 2025). | University of Cambridge |

| NOMAD | Novel materials discovery project | 12 m | https://nomad-lab.eu/prod/rae/gui/search (accessed on 4 November 2025). | Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin |

| Materials Cloud | A platform for open computational science | 29 m | https://www.materialscloud.org (accessed on 4 November 2025). | École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne |

| CEP | Harvard clean energy project | 2 m | http://cleanenergy.harvard.edu (accessed on 4 November 2025). | Harvard University |

| OMDB | An electronic structure database for various organic and organometallic materials | 12.5 k | https://omdb.mathub.io (accessed on 4 November 2025). | KTH Royal Institute of Technology and Stockholm University |

| PubChem | An open chemistry database for small molecules | 115 m | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 4 November 2025). | National Institutes of Health (NIH) |

| NREL MatDB | Computational materials database for renewable energy applications | 20 k | https://materials.nrel.gov (accessed on 4 November 2025). | National Renewable Energy Laboratory |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Obada, D.O.; Akinpelu, S.B.; Abolade, S.A.; Kekung, M.O.; Okafor, E.; Kumar R, S.; Ukpong, A.M.; Akande, A. Machine Learning for Photocatalytic Materials Design and Discovery. Crystals 2025, 15, 1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121034

Obada DO, Akinpelu SB, Abolade SA, Kekung MO, Okafor E, Kumar R S, Ukpong AM, Akande A. Machine Learning for Photocatalytic Materials Design and Discovery. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121034

Chicago/Turabian StyleObada, David O., Shittu B. Akinpelu, Simeon A. Abolade, Mkpe O. Kekung, Emmanuel Okafor, Syam Kumar R, Aniekan M. Ukpong, and Akinlolu Akande. 2025. "Machine Learning for Photocatalytic Materials Design and Discovery" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121034

APA StyleObada, D. O., Akinpelu, S. B., Abolade, S. A., Kekung, M. O., Okafor, E., Kumar R, S., Ukpong, A. M., & Akande, A. (2025). Machine Learning for Photocatalytic Materials Design and Discovery. Crystals, 15(12), 1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121034