Corrosion and Discharge Behavior of Mg-Y-Al-Zn Alloys as Anode Materials for Primary Mg-Air Batteries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Microstructure Characterization

2.3. Electrochemical Test

2.4. Immersion Test

2.5. Battery Tests

3. Results and Discussion

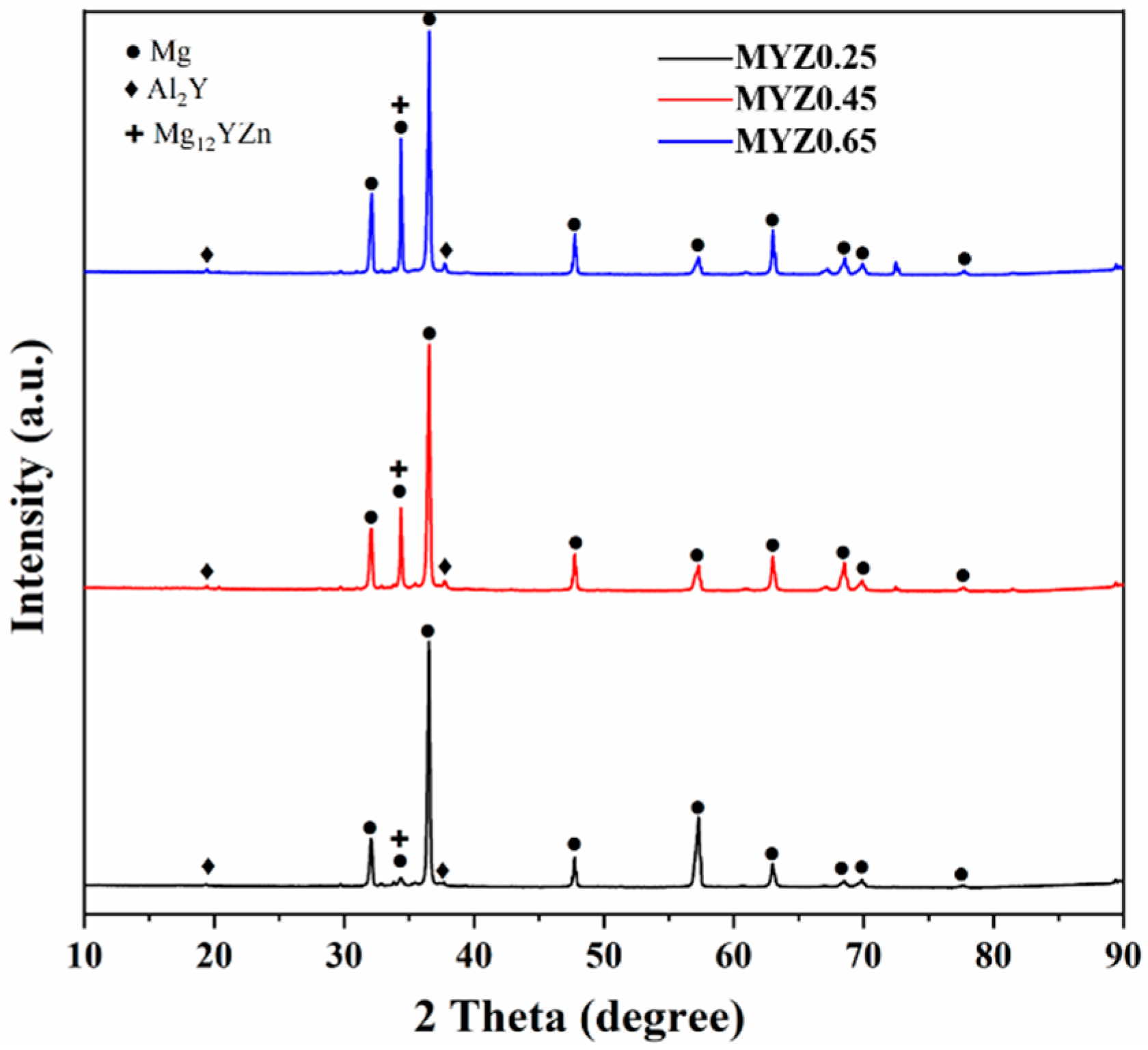

3.1. Microstructure

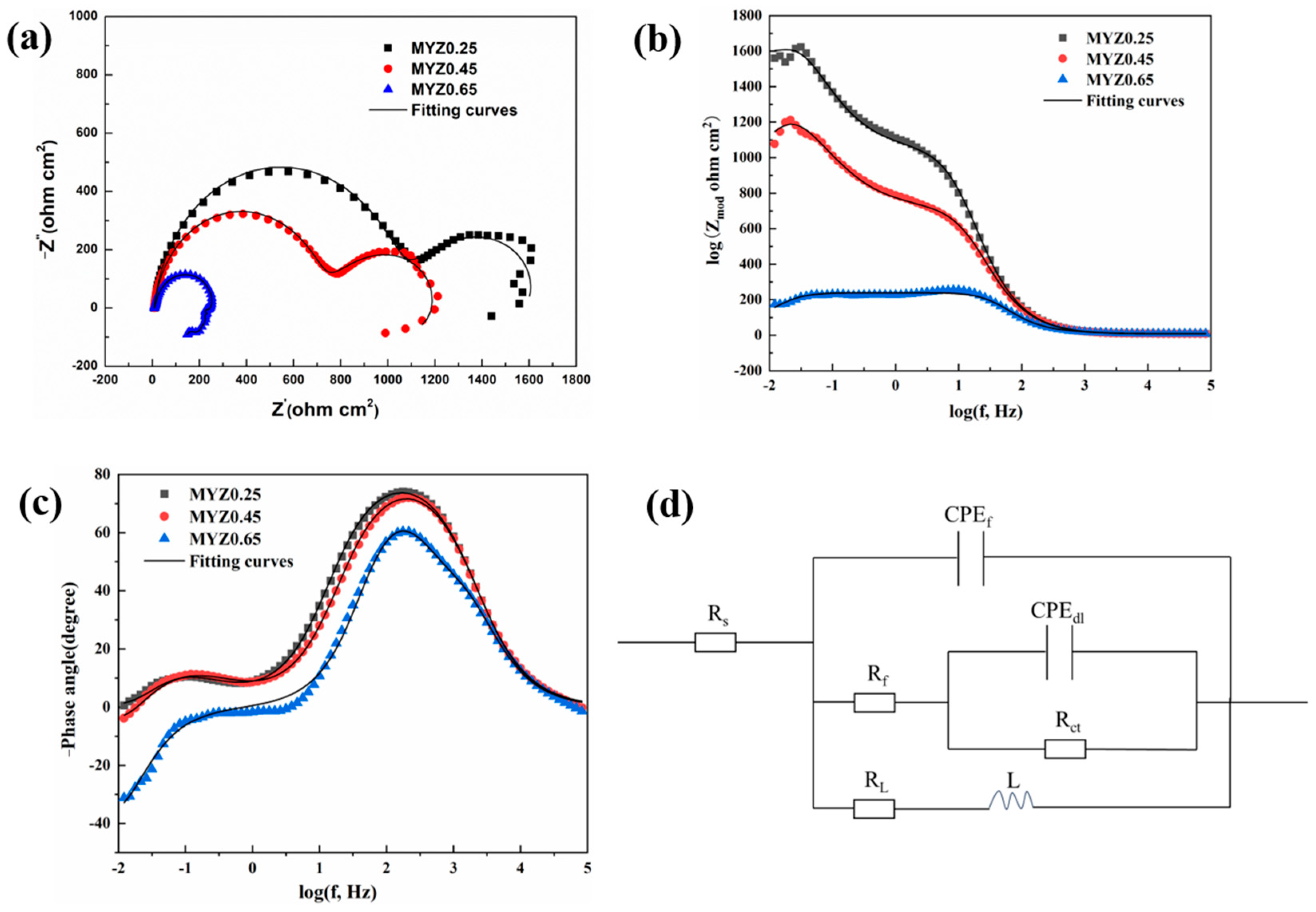

3.2. Electrochemical Impedance Spectra

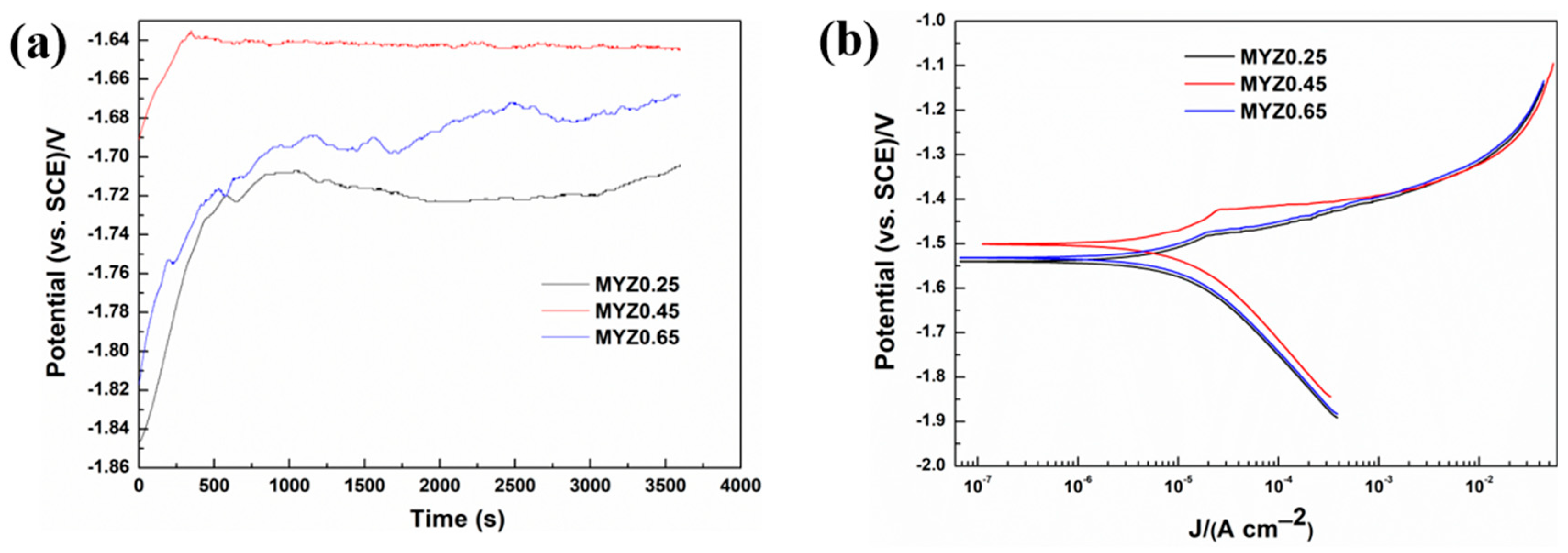

3.3. Potentiodynamic Polarization Curve

3.4. Immersion Test

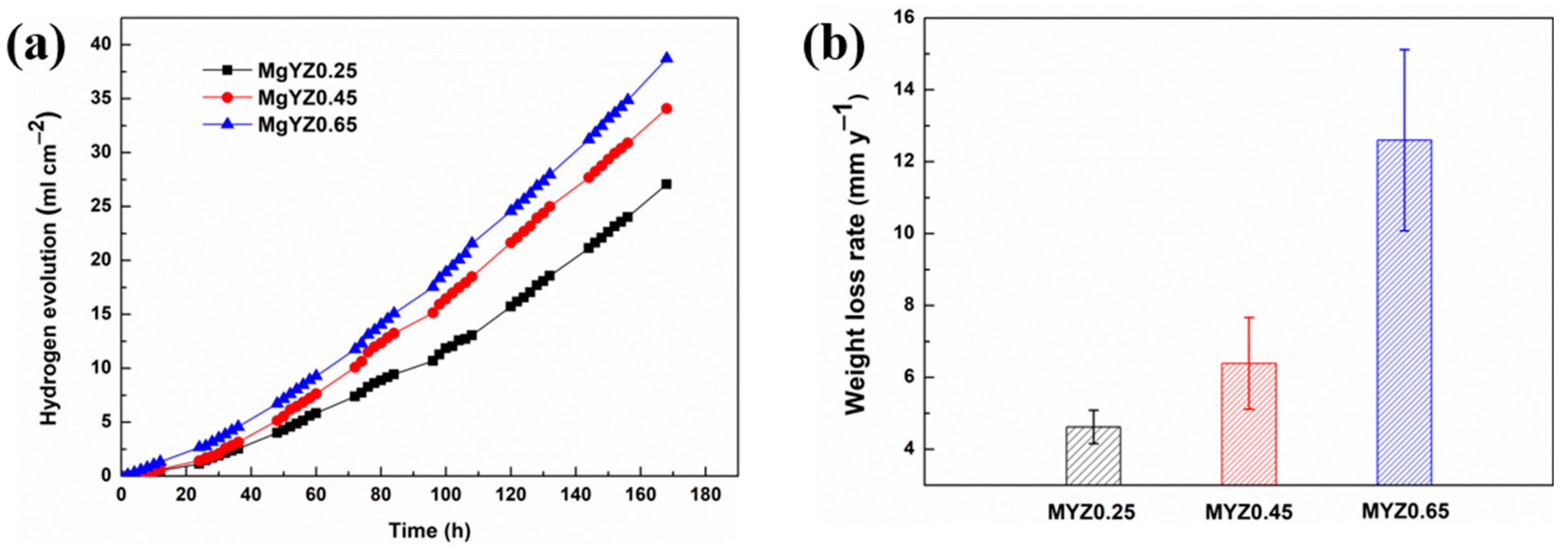

3.5. Galvanostatic Discharge Test

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EIS | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy |

| OCP | Open-Circuit Potential |

| SCE | Saturated Calomel Electrode |

| CPE | Constant Phase Element |

| NDE | Negative Difference Effect |

References

- Chen, X.R.; Liu, X.; Li, Q.H.; Zhang, M.X.; Liu, M.; Atrens, A. A comprehensive review of the development of magnesium anodes for primary batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 12367–12399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.B.; Li, H.; Zhao, C.C.; Wang, Z.H.; Liu, K.; Du, W.B. Effects of Ca addition on microstructure, electrochemical behavior and magnesium-air battery performance of Mg-2Zn−xCa alloys. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 904, 115944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.X.; Lu, X.P.; Yang, L.; Tie, D.; Zhang, T.; Wang, F.H. Regulating discharge performance of Mg anode in primary Mg-air battery by complexing agents. Electrochim. Acta 2021, 370, 137805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.G.; Li, W.P.; Huang, Y.X.; Wu, G.; Hu, M.C.; Li, G.Z.; Shi, Z.C. Wrought Mg-Al-Pb-RE alloy strips as the anodes for Mg-air batteries. J. Power Sources 2019, 436, 226855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.X.; Wang, J.J.; Song, Y.; Chen, Z.Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Z.; Han, X.P.; Hu, W.B. In Situ Interfacial Passivation in Aqueous Electrolyte for Mg-Air Batteries with High Anode Utilization and Specific Capacity. ChemSusChem 2023, 16, e202202207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaz, T.R.; Weber, C.R.; Pelegrini, T.; Knörnschild, G. The negative difference effect of magnesium and of the AZ91 alloy in chloride and stannate-containing solutions. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 2235–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.Q.; Lu, H.M.; Sun, Z.G.; Fan, L.; Zhu, X.Y.; Zhang, W. Electrochemical performance of Mg-3Al modified with Ga, In and Sn as anodes for Mg-air battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, A1181–A1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.L.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, M.S.; Qin, C.H.; Ren, F.Z.; Wang, G.X. Corrosion and discharge performance of a magnesium aluminum eutectic alloy as anode for magnesium-air batteries. Corros. Sci. 2020, 170, 108695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.N.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.H. Influence of cerium on passivity behavior of wrought AZ91 alloy. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 54, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Yan, R.; Liu, K.D.; Li, Y.; Chen, W.; Chen, K.; Gan, L.; Huang, J.; Ren, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. The semi-continuous (Mg, Al)2Ca second phase on Mg-Al-Ca-Mn alloys as an efficient anti-corrosion anode for Mg-air batteries. J. Alloy Compd. 2024, 990, 174387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Li, Y.; Cao, F.; Qiu, D.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Ying, T.; Ding, W.; Zeng, X. Towards development of a high-strength stainless Mg alloy with Al-assisted growth of passive film. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.C.; Tsai, C.Y.; Uan, J.Y. Electrochemical behaviour and corrosion performance of Mg-Li-Al-Zn anodes with high Al composition. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 2463–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, F.; Chen, X.; Wang, Q.; Wei, S.; Gao, W. Hypoeutectic Mg-Zn binary alloys as anode materials for magnesium-air batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 857, 157579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, R.; Feng, Y.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, J.; Deng, M. Discharge and corrosion behaviour of Mg-Li-Al-Ce-Y-Zn alloy as the anode for Mg-air battery. Corros. Sci. 2016, 112, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Yu, K.; Xiong, H.; Dai, Y.; Yang, S.; Qiao, X.; Teng, F.; Fan, S. Composition optimization and electrochemical properties of Mg-Al-Pb-(Zn) alloys as anodes for seawater activated battery. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 194, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, G.L.; Li, Y.D.; Zang, S.J.; Zhang, J.B.; Ma, Y.; Hao, Y. Microstructure, mechanical and corrosion properties of Mg–2Dy–xZn (x = 0, 0.1, 0.5 and 1 at.%) alloys. J. Magnes. Alloy 2014, 2, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.Y.; Kang, J.Y.; Yang, J.; Yim, C.D.; You, B.S. Limitations in the use of the potentiodynamic polarisation curves to investigate the effect of Zn on the corrosion behaviour of as-extruded Mg–Zn binary alloy. Corros. Sci. 2013, 75, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, A.; Huang, Y.D.; Mendis, C.L.; Dieringa, H.; Blawert, C.; Kainer, K.U.; Hort, N. Microstructure, Mechanical and Corrosion Properties of Mg-Gd-Zn Alloys. Mater. Sci. Forum 2013, 765, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, R.C.; Peng, C.Q.; Feng, Y. Influence of zinc on electrochemical discharge activity of Mg-6%Al-5%Pb anode. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. 2012, 19, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.P.; Zhang, S.Q.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, D.S. Quasicrystals in as-cast Mg-Zn-RE alloys. Scr. Metall. Mater. 1993, 28, 1513–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.D.; Xu, D.K.; Chen, X.B.; Han, E.H.; Dong, C. Effect of heat treatment on the corrosion resistance and mechanical properties of an as-forged Mg–Zn–Y–Zr alloy. Corros. Sci. 2015, 92, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, D.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, W.T. Deformation behavior of Mg–Zn–Y alloys reinforced by icosahedral quasicrystalline particles. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 2343–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Lim, H.K.; Kim, D.H. Effects of Zn/Y ratio on microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-Zn-Y alloys. Mater. Lett. 2005, 59, 3801–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zou, Q.; Le, Q.; Hou, J.; Guo, R.; Wang, H.; Hu, C.; Bao, L.; Wang, T.; Zhao, D.; et al. The quasicrystal of Mg–Zn–Y on discharge and electrochemical behaviors as the anode for Mg-air battery. J. Power Sources 2020, 451, 227807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhlin, L.L. Magnesium Alloys Containing Rare Earth Metals: Structure and Properties; CRC Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Shan, D.; Song, Y.; Han, E. Inffuence of yttrium element on the corrosion behaviors of Mg–Y binary magnesium alloy. J. Magnes. Alloys 2017, 5, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikokhatnyi, O.I.; Kumta, P.N. First-principles studies on alloying and simpliffed thermodynamic aqueous chemical stability of calcium-, zinc-, aluminum-, yttriumand iron-doped magnesium alloys. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 1698–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Schmutz, P.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Song, G.; Atrens, A. The inffuence of yttrium (Y) on the corrosion of Mg-Y binary alloys. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 3687–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudholz, A.D.; Gusieva, K.; Chen, X.B.; Muddle, B.C.; Gibson, M.A.; Birbilis, N. Electrochemical behaviour and corrosion of Mg–Y alloys. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 2277–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Liu, M.; Xu, Y.; Cao, D.; Feng, J.; Wu, R.; Zhang, M. The electrochemical behaviors of Mg–8Li–0.5Y and Mg–8Li–1Y alloys in sodium chloride solution. J. Power Sources 2013, 239, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Xu, Y.; Cao, D. The electrochemical behaviors of Mg, Mg-Li-Al-Ce and Mg-Li-Al-Ce-Y in sodium chloride solution. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 8809–8814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Meng, G.; Shao, Y.; Cui, Z.; Wang, F. Corrosion of hot extrusion AZ91 magnesium alloy. Part II: Effect of rare earth element neodymium (Nd) on the corrosion behavior of extruded alloy. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 2934–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Shan, D.; Chen, R.; Han, E.H. Corrosion characterization of Mg–8Li alloy in NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jüttner, K. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) of corrosion processes on inhomogeneous surfaces. Electrochim. Acta 1990, 35, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Atrens, A.; John, D.S.; Wu, X.; Nairn, J. The anodic dissolution of magnesium in chloride and sulphate solutions. Corros. Sci. 1997, 39, 1981–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.D.; Birbilis, N.; Scully, J.R. Accurate electrochemical measurement of magnesium corrosion rates: A combined impedance, mass-loss and hydrogen collection study. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 121, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfenov, E.V.; Kulyasova, O.B.; Mukaeva, V.R.; Mingo, B.; Farrakhov, R.G.; Cherneikina, Y.V.; Yerokhin, A.; Zheng, Y.F.; Valiev, R.Z. Influence of ultra-fine grain structure on corrosion behaviour of biodegradable Mg-1Ca alloy. Corros. Sci. 2020, 163, 108303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.S.; Kim, W. Enhancement of mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of Mg-Ca alloys through microstructural refinement by indirect extrusion. Corros. Sci. 2014, 82, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; Idris, M.H.; Abdul-Kadir, M.R.; Ourdjini, A.; Medraj, M.; Daroonparvar, M.; Hamzah, E. Mechanical and bio-corrosion properties of quaternary Mg-Ca-Mn-Zn alloys compared with binary Mg-Ca alloys. Mater. Des. 2014, 53, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Höche, D.; Lamaka, S.V.; Snihirova, D.; Zheludkevich, M.L. Mg-Ca binary alloys as anodes for primary Mg-air batteries. J. Power Sources 2018, 396, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, R.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Y. Electrochemical discharge performance of the Mg-Al-Pb-Ce-Y alloy as the anode for Mg-air batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 8658–8668. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Wang, R.; Peng, C.; Peng, B.; Feng, Y.; Hu, C. Discharge behaviour of Mg-Al-Pb and Mg-Al-Pb-In alloys as anodes for Mg-air battery. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 149, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, M.; di Gabriele, F.; Bonora, P.L.; Scantlebury, D. Corrosion behaviour of magnesium sacrificial anodes in tap water. Mater. Corros. 2003, 54, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, H.; Fang, H.; Dai, Y.; Li, L.; Xu, X.; Yan, Y.; Yu, K. Electrochemical performance of Mg-Al-Zn and Mg-Al-Zn-Ce alloys as anodes for Mg-air battery. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2018, 13, 11180–11192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Ren, F.; Volinsky, A.A. Electrochemical performance of Mg-air batteries based on AZ series magnesium alloys. Ionics 2019, 25, 2201–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, G.; Ren, F.; Zhu, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, J. Effect by adding Ce and In to Mg–6Al Alloy as anode on performance of Mg-air batteries. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 066315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xue, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Z. Effects of the combinative Ca, Sm and La additions on the electrochemical behaviors and discharge performance of the as-extruded AZ91 anodes for Mg-air batteries. J. Power Sources 2019, 414, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Y | Al | Zn | Fe | Si | Mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg-8Y-0.8Al-0.25Zn | 8.0674 | 0.8188 | 0.2493 | 0.0138 | 0.1314 | Bal. |

| Mg-8Y-0.8Al-0.45Zn | 7.8636 | 0.7898 | 0.4303 | 0.0117 | 0.1182 | Bal. |

| Mg-8Y-0.8Al-0.65Zn | 8.1560 | 0.7770 | 0.6467 | 0.0153 | 0.1961 | Bal. |

| Element wt.% Point | Mg | Al | Y | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 3.42 | 32.12 | 64.36 | 0.1 |

| II | 86.06 | 0.39 | 13.07 | 0.49 |

| III | 66.78 | 2.47 | 25.14 | 5.61 |

| Mg Electrode | Rs Ω cm2 | Yf Ω−1 cm−2 sn | n | Rf Ω cm2 | Yct Ω−1 cm−2 sn | n | Rct Ω cm2 | L H | RL Ω cm2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYZ0.25 | 9.213 | 1.486 × 10−5 | 0.9388 | 1037 | 0.002547 | 0.7263 | 770.4 | 1.874 × 104 | 2054 |

| MYZ0.45 | 8.732 | 1.591 × 10−5 | 0.9377 | 705.8 | 0.002679 | 0.6862 | 624.8 | 1.306 × 104 | 649.6 |

| MYZ0.65 | 8.786 | 3.775 × 10−5 | 0.9184 | 9.17 | 1.621 × 10−5 | 1 | 221.3 | 2911 | 58.99 |

| Anode | Eocp (vs. SCE)/V | Ecorr (vs. SCE)/V | Jcorr/(μA·cm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MYZ0.25 | −1.717 | −1.540 | 12.56 |

| MYZ0.45 | −1.644 | −1.501 | 13.55 |

| MYZ0.65 | −1.676 | −1.451 | 45.18 |

| Anode | Electrolyte, wt.% | Cathode Catalyst | Current Density, mA·cm −2 | Average Voltage, V | Anodic Efficiency, % | Discharge Capacity, mA·h·g−1 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg | 3.5NaCl | MnO2 | 10 | 0.806 | 54.3 | 1204 | [44] |

| As-cast 3N5Mg | 3.5NaCl | MnO2 | 10 | 1.226 | 30 | [45] | |

| A3(T2) | 3.5NaCl | MnO2 | 10 | 1.087 | 46.8 | 1054 | [7] |

| A6(T2) | 3.5NaCl | MnO2 | 10 | 1.026 | 34.1 | 761 | [46] |

| As-cast AZ31 | 3.5NaCl | MnO2 | 10 | 1.195 | 32 | [45] | |

| AZ31(O) | 3.5NaCl | MnO2 | 10 | 0.819 | 53.6 | 1194 | [44] |

| AZ61-0.5Ce(O) | 3.5NaCl | MnO2 | 10 | 0.896 | 55.1 | 1377 | [44] |

| AZ91-1.5Ca | 3.5NaCl | MnO2 | 10 | 1.27 | 51.5 | 1155 | [47] |

| AZ91-1.5Sm(O) | 3.5NaCl | MnO2 | 10 | 1.29 | 50.8 | 1144 | [47] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dai, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Guo, S. Corrosion and Discharge Behavior of Mg-Y-Al-Zn Alloys as Anode Materials for Primary Mg-Air Batteries. Crystals 2025, 15, 1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121033

Dai J, Zhu H, Zhang Y, Wang C, Guo S. Corrosion and Discharge Behavior of Mg-Y-Al-Zn Alloys as Anode Materials for Primary Mg-Air Batteries. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121033

Chicago/Turabian StyleDai, Junhao, Hongjun Zhu, Yu Zhang, Chengwu Wang, and Shirui Guo. 2025. "Corrosion and Discharge Behavior of Mg-Y-Al-Zn Alloys as Anode Materials for Primary Mg-Air Batteries" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121033

APA StyleDai, J., Zhu, H., Zhang, Y., Wang, C., & Guo, S. (2025). Corrosion and Discharge Behavior of Mg-Y-Al-Zn Alloys as Anode Materials for Primary Mg-Air Batteries. Crystals, 15(12), 1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121033