The Role of Pluronic Copolymer on the Physicochemical Characteristics of ZnO-CeO2 Photocatalysts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of the Nanosized CeO2-ZnO Materials

2.2. Physicochemical Characterization of Prepared Nanosized CeO2-ZnO Materials

2.3. Photocatalytic Ability Tests

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Nanosized CeO2-ZnO Materials

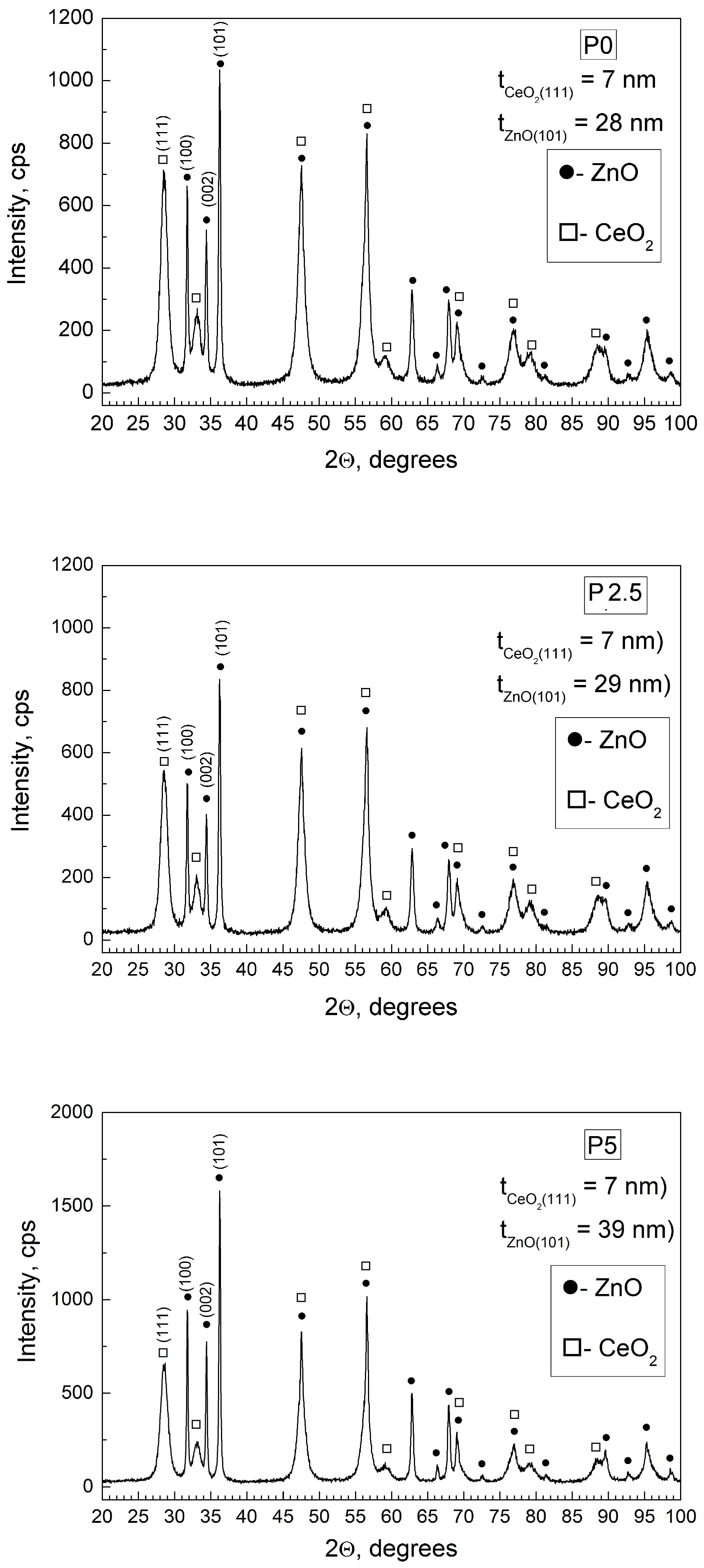

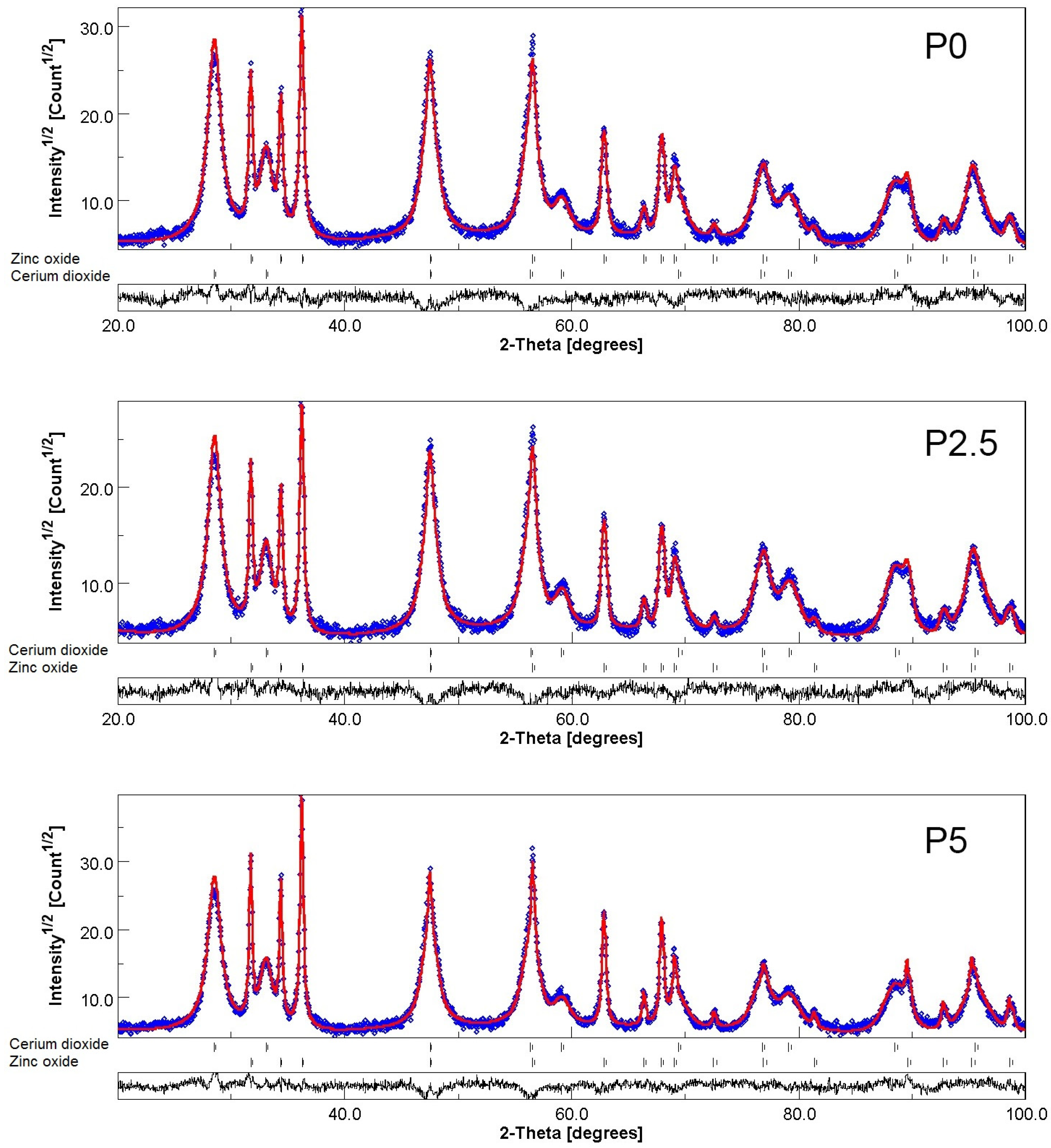

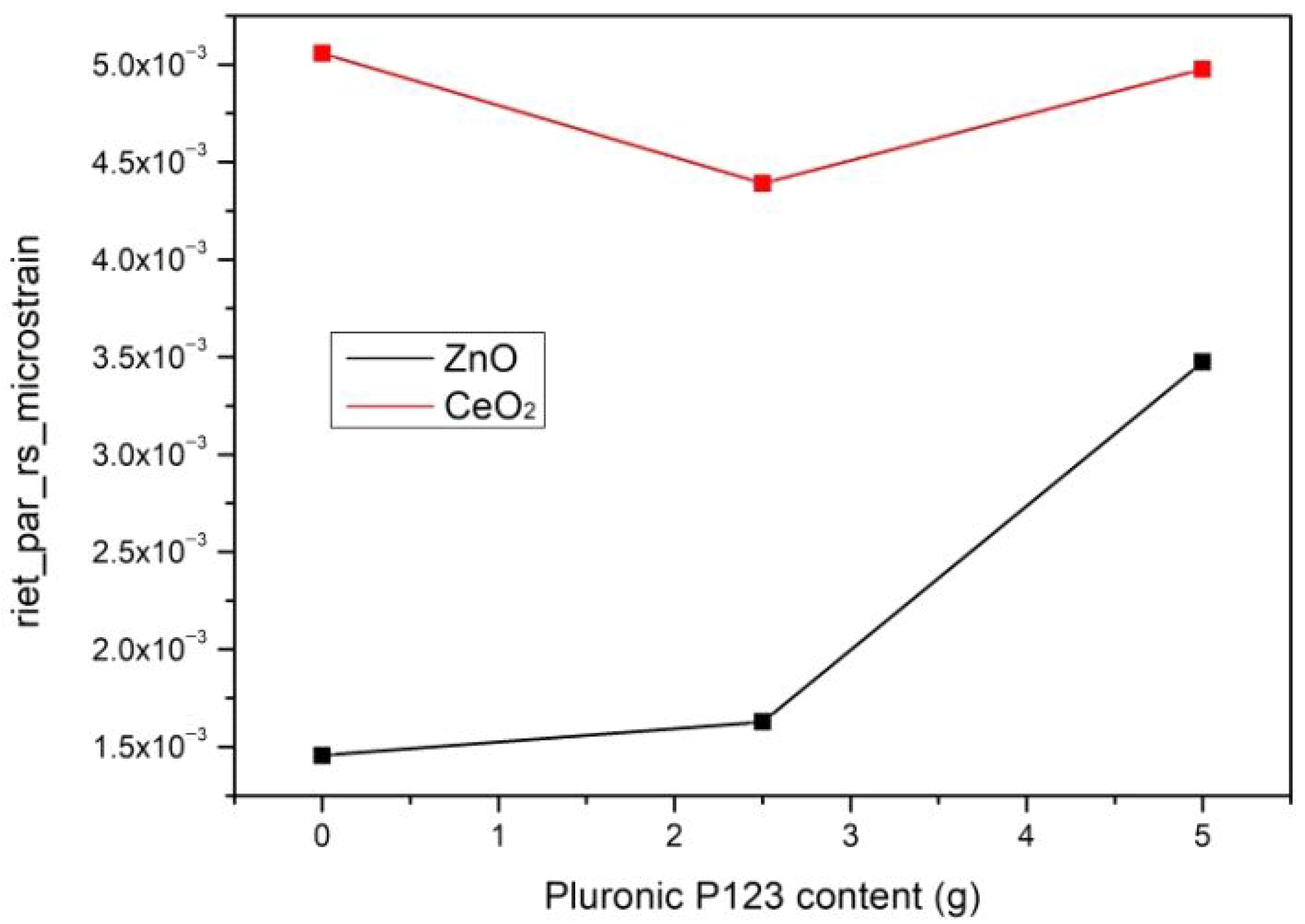

3.1.1. PXRD Study

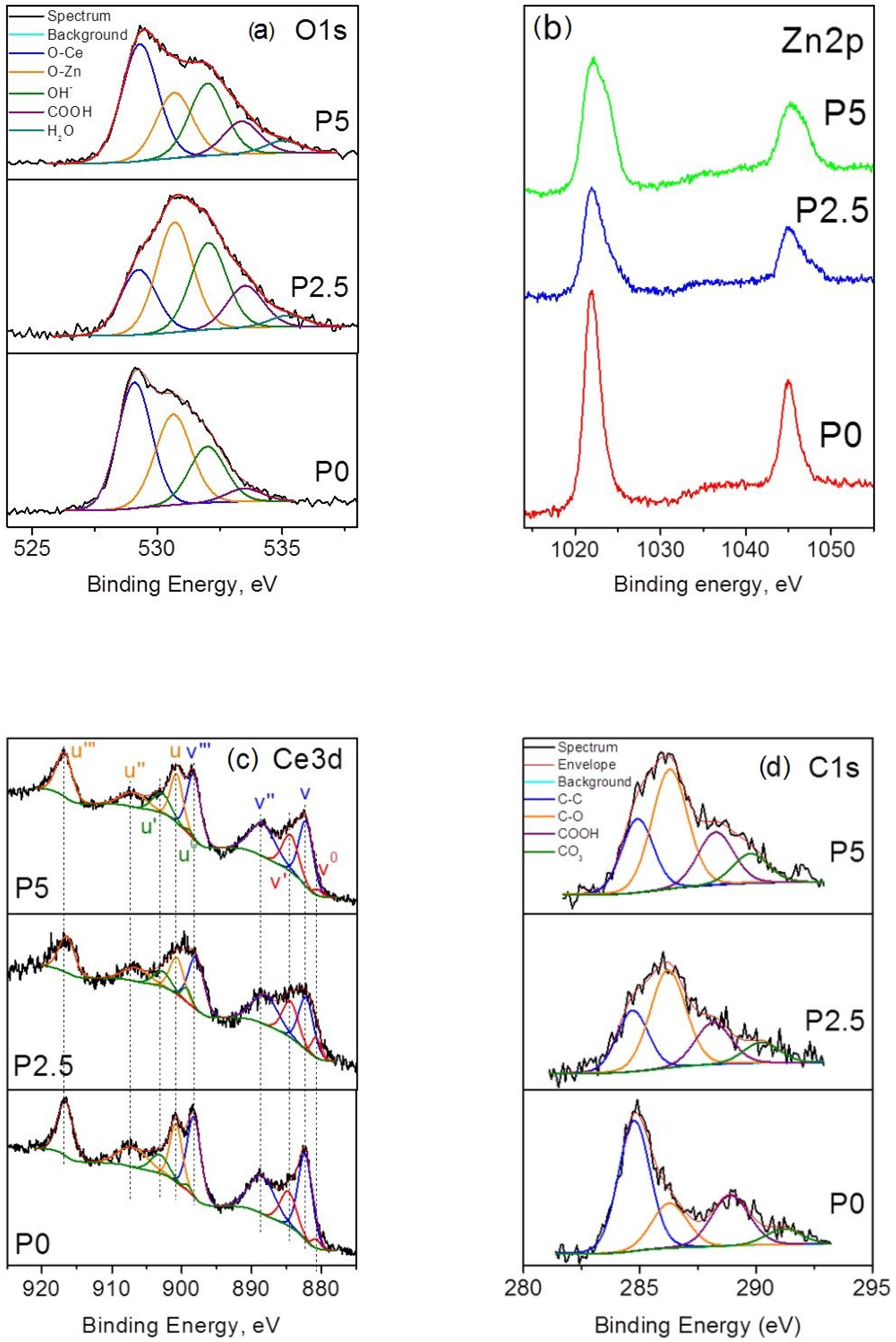

3.1.2. XPS Study

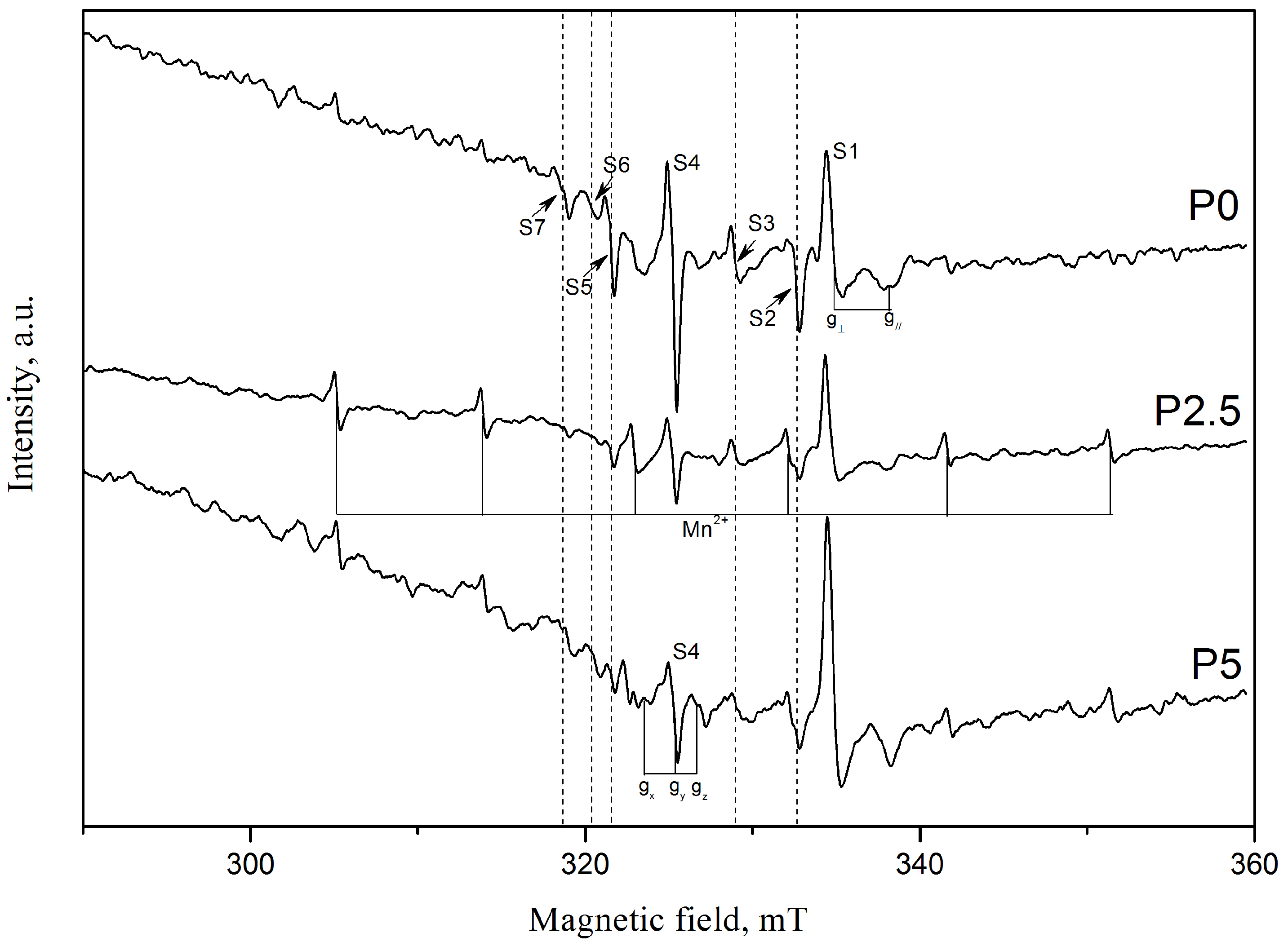

3.1.3. EPR Spectroscopy

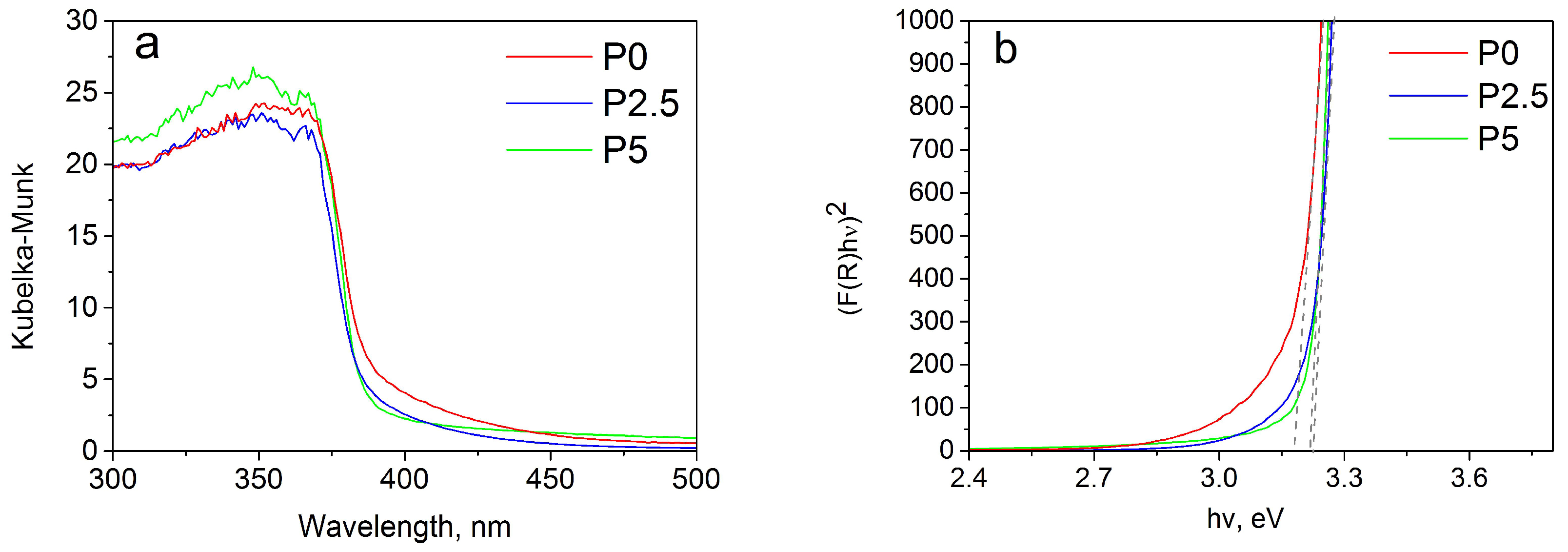

3.1.4. DRS Analyses

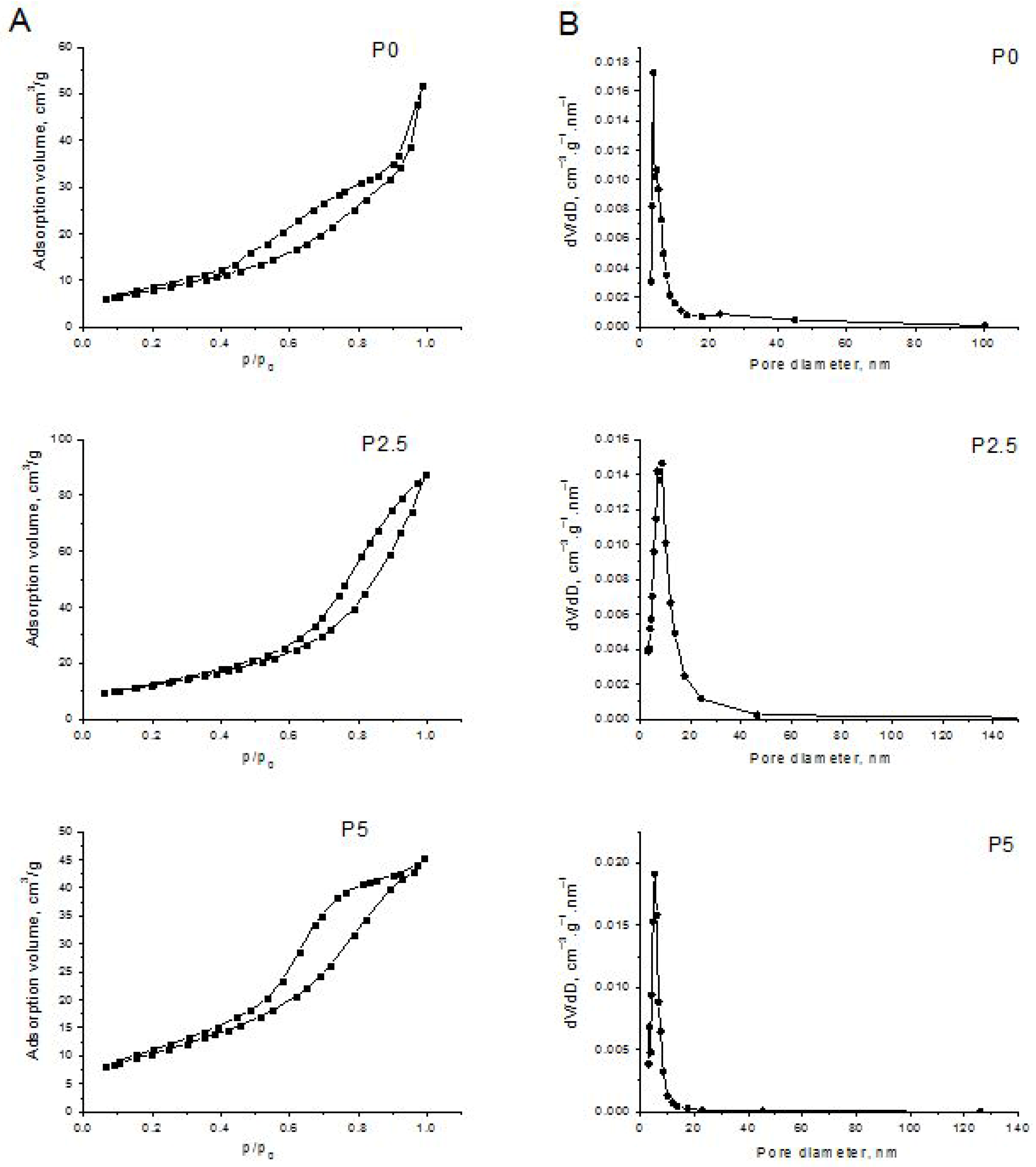

3.1.5. Textural Characteristics of the Prepared ZnO-CeO2 Samples

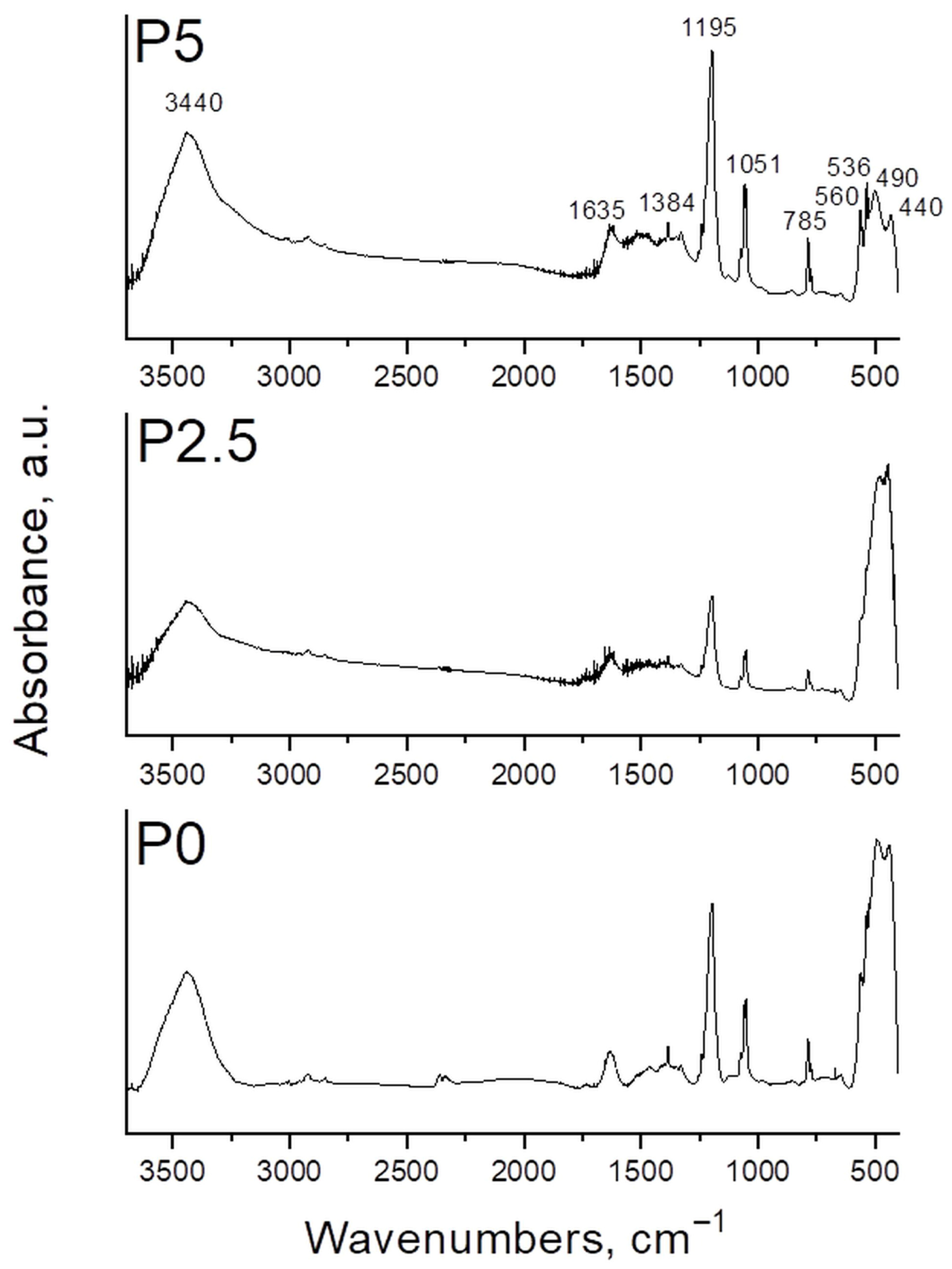

3.1.6. FT-IR Spectroscopy of the Synthesized ZnO-CeO2 Powders

3.1.7. TEM Analysis and EDS Mapping/Spectra of the Prepared ZnO-CeO2 Materials

3.2. Photocatalytic Activity of the Synthesized ZnO-CeO2 Nanomaterials

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Habibi, M.H.; Fakhrpor, M. Synthesis, Characterization and Application of Pure Ceria, Pure Zinc Oxide, Ceria Zinc Oxide Nano Composite: Synergetic Effect on Photo-Catalytic Degradation of Amido Black 10B in Water. Desalination Water Treat. 2017, 60, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.H.; Fakhrpor, M. Enhanced Photo-Catalytic Activity of CeO2-ZnO Nano-Structure for Degradation of Textile Dye Pollutants in Water. Desalination Water Treat. 2017, 60, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.; Bhangaonkar, K.; Pinjari, D.V.; Mhaske, S.T. Ultrasound and Conventional Synthesis of CeO2/ZnO Nanocomposites and Their Application in the Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B Dye. J. Adv. Nanomater. 2017, 2, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, V.; Lad, P.; Thakkar, A.B.; Thakor, P.; Deshpande, M.P.; Pandya, S. CeO2-ZnO Nano Composites: Dual-Functionality for Enhanced Photocatalysis and Biomedical Applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 159, 111738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, S.; Sasibabu, V.; Jegadeesan, G.B.; Venkatachalam, P. Photocatalytic Degradation of Reactive Black Dye Using ZnO–CeO2 Nanocomposites. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 42713–42727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, S.; Khan, M.M.; Gracia, F.; Qin, J.; Gupta, V.K.; Arumainathan, S. Ce3+-Ion-Induced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Degradation and Electrochemical Activity of ZnO/CeO2 Nanocomposite. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, E.; Gonçalves, N.P.F.; Calza, P.; Paganini, M.C. Comparison of the Photocatalytic Activity of ZnO/CeO2 and ZnO/Yb2O3 Mixed Systems in the Phenol Removal from Water: A Mechanicistic Approach. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.G.I.; Nurfitria, R.; Anggraini, T.; Aini, Q.; Hanifah, I.R.; Nurfani, E.; Aflaha, R.; Triyana, K.; Taher, T.; Rianjanu, A. Hydrothermal Synthesis of CeO2/ZnO Heterojunctions for Effective Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2025, 322, 118630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, V.; Yadav, S.; Mittal, A.; Sharma, S.; Kumari, K.; Kumar, N. Hydrothermally Synthesized Nano-Carrots ZnO with CeO2 Heterojunctions and Their Photocatalytic Activity towards Different Organic Pollutants. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 5227–5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jiang, H.; Kuang, L.; Zhang, M. Synthesis of Highly Dispersed MnOx–CeO2 Nanospheres by Surfactant-Assisted Supercritical Anti-Solvent (SAS) Technique: The Important Role of the Surfactant. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2014, 92, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandan, M.; Dinesh, S.; Krishnakumar, N.; Balamurugan, K. Improved Photocatalytic Properties and Anti-Bacterial Activity of Size Reduced ZnO Nanoparticles via PEG-Assisted Precipitation Route. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 12517–12526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Chouchene, B.; Liu, M.; Moussa, H.; Schneider, R.; Moliere, M.; Liao, H.; Chen, Y.; Sun, L. Influence of Laminated Architectures of Heterostructured CeO2-ZnO and Fe2O3-ZnO Films on Photodegradation Performances. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 403, 126367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soli, J.; Kachbouri, S.; Elaloui, E.; Charnay, C. Role of Surfactant Type on Morphological, Textural, Optical, and Photocatalytic Properties of ZnO Nanoparticles Obtained by Modified Sol–Gel. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2021, 100, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Yuan, Z.; Cao, J. Hydrangea—Like Meso—/Macroporous ZnO—CeO2 Binary Oxide Materials: Synthesis, Photocatalysis and CO Oxidation. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 2010, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.; Mateos-Pedrero, C.; Magén, C.; Pacheco Tanaka, D.A.; Mendes, A. Simple Hydrothermal Synthesis Method for Tailoring the Physicochemical Properties of ZnO: Morphology, Surface Area and Polarity. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 31166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali Sarvestani, M.R.; Doroudi, Z. Removal of Reactive Black 5 from Waste Waters by Adsorption: A Comprehensive Review. J. Water Environ. Nanotechnol. 2020, 5, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.; Mishra, M.K.; Saha, J.; De, G. Design of Mesoporous Alumina–Ceria Films on Glass: Compositional Tuning Leads to Mesoscopic Transformations. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2015, 203, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Tripathy, N.; Khan, M.Y.; Bhat, K.S.; Ahn, M.; Hahn, Y.-B. Ammonium Ion Detection in Solution Using Vertically Grown ZnO Nanorod Based Field-Effect Transistor. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 54836–54840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Buzo, S.; Concepción, P.; Olloqui-Sariego, J.L.; Moliner, M.; Corma, A. Metalloenzyme-Inspired Ce-MOF Catalyst for Oxidative Halogenation Reactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 31021–31030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazirov, A.; Sokovnin, S.Y.; Ilves, V.G.; Bazhukova, I.N.; Pizurova, N.; Kuznetsov, M.V. Physicochemical characterization and antioxidant properties of cerium oxide nanoparticles. IOP Conf. Ser. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1115, 032094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, G. XPS Study of Cerium Conversion Coating on the Anodized 2024 Aluminum Alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2004, 364, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, C.; Kappis, K.; Papavasiliou, J.; Vakros, J.; Kuśmierz, M.; Gac, W.; Georgiou, Y.; Deligiannakis, Y.; Avgouropoulos, G. Copper-Promoted Ceria Catalysts for CO Oxidation Reaction. Catal. Today 2020, 355, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappis, K.; Papadopoulos, C.; Papavasiliou, J.; Vakros, J.; Georgiou, Y.; Deligiannakis, Y.; Avgouropoulos, G. Tuning the Catalytic Properties of Copper-Promoted Nanoceria via a Hydrothermal Method. Catalysts 2019, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lin, X.; Li, G.; Inomata, H. Solid Solubility and Transport Properties of Ce 1− x NdxO2−δ Nanocrystalline Solid Solutions by a Sol-Gel Route. J. Mater. Res. 2001, 16, 3207–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, J.; Martínez-Arias, A.; Conesa, J. Effect of Oxidized Rhodium on Oxygen Adsorption on Cerium Oxide. Vacuum 1992, 43, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.U.; Yildirim, I.D.; Aleinawi, M.H.; Buldu-Akturk, M.; Turhan, N.S.; Nadupalli, S.; Rostas, A.M.; Erdem, E. Multifrequency EPR Spectroscopy Study of Mn, Fe, and Cu Doped Nanocrystalline ZnO. Mater. Res. Bull. 2023, 160, 112117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aškrabić, S.; Dohčević-Mitrović, Z.D.; Araújo, V.D.; Ionita, G.; De Lima, M.M.; Cantarero, A. F-Centre Luminescence in Nanocrystalline CeO2. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2013, 46, 495306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, E.; Gionco, C.; Paganini, M.C.; Giamello, E. Photoactivity Properties of ZnO Doped with Cerium Ions: An EPR Study. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2017, 29, 444001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Klabunde, K.J. Superoxide (O2−) on the Surface of Heat-Treated Ceria. Intermediates in the Reversible Oxygen to Oxide Transformation. Inorg. Chem. 1992, 31, 1706–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, M.; Popa, A.; Toloman, D.; Dehelean, A.; Lung, I.; Katona, G. Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation Properties of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Synthesized by Using Plant Extracts. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2015, 39, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.P.; Gopal, N.O.; Wang, T.C.; Wong, M.-S.; Ke, S.C. EPR Investigation of TiO2 Nanoparticles with Temperature-Dependent Properties. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 5223–5229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micic, O.I.; Zhang, Y.; Cromack, K.R.; Trifunac, A.D.; Thurnauer, M.C. Trapped Holes on Titania Colloids Studied by Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 7277–7283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brückner, A.; Bentrup, U.; Zanthoff, H.; Maschmeyer, D. The Role of Different Ni Sites in Supported Nickel Catalysts for Butene Dimerization under Industry-like Conditions. J. Catal. 2009, 266, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanboon, S.; Amornpitoksuk, P.; Bangrak, P.; Sukolrat, A.; Muensit, N. The Dependence of Optical Properties on the Morphology and Defects of Nanocrystalline ZnO Powders and Their Antibacterial Activity. J. Ceram. Process. Res. 2010, 11, 547–551. [Google Scholar]

- Vlaev, L.T. Adsorption and Catalysis; Baltika-2002: Burgas, Bulgaria, 2015; p. 86. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, A.; Yadav, L.S.R.; Bahkali, A.H.; Elgorban, A.M.; Abdul Hakeem, D.; Ganganagappa, N. Effect of CeO2-ZnO Nanocomposite for Photocatalytic and Antibacterial Activities. Crystals 2020, 10, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmandjou, M.; Zarinkamar, M.; Firoozabadi, T.P. Synthesis of Cerium Oxide (CeO2) Nanoparticles Using Simple CO-Precipitation Method. Rev. Mex. Física 2016, 62, 496–499. [Google Scholar]

- Spasov, S.; Arnaudov, M. Application of Spectroscopy in Organic Chemistry; Science and Art: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1978; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A.M.; Khan, W.; Ahamed, M.; Alhazaa, A.N. Microstructural Properties and Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance of Zn Doped CeO2 Nanocrystals. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, I.-T.; Hon, M.-H.; Teoh, L.G. The Preparation, Characterization and Photocatalytic Activity of Radical-Shaped CeO2/ZnO Microstructures. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 4019–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Lei, Z.; Xu, Z.; Chen, X.; Gong, B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, C. Flame Spray Pyrolysis Synthesized ZnO/CeO2 Nanocomposites for Enhanced CO2 Photocatalytic Reduction under UV–Vis Light Irradiation. J. CO2 Util. 2017, 18, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, R.; Agarwal, S.; Gupta, V.K.; Khan, M.M.; Gracia, F.; Mosquera, E.; Narayanan, V.; Stephen, A. Line Defect Ce3+ Induced Ag/CeO2/ZnO Nanostructure for Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018, 353, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, R.; Umar, A.; Mehta, S.K.; Kansal, S.K. CeO2ZnO Hexagonal Nanodisks: Efficient Material for the Degradation of Direct Blue 15 Dye and Its Simulated Dye Bath Effluent under Solar Light. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 620, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qin, J.; Xue, Y.; Yu, P.; Zhang, B.; Wang, L.; Liu, R. Effect of Aspect Ratio and Surface Defects on the Photocatalytic Activity of ZnO Nanorods. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wu, R.; Ji, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Sahar, S.; Zeb, A. Efficient CeO2/ZnO Heterojunction for Enhanced Heterogeneous Photocatalytic Application. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 171, 113553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Rp (%) | Rwp (%) | Rexp (%) | GOF (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0 | 0.09 | 11.72 | 9.82 | 1.42 |

| P2.5 | 0.10 | 12.43 | 10.89 | 1.30 |

| P5 | 0.09 | 11.49 | 9.18 | 1.36 |

| Phase | Sample | Quantity [wt.%] | Unit Cell Parameters | D [nm] | ε | Χ [%] I(002)/I(100) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a [Å] | b [Å] | c [Å] | V [Å3] | ||||||

| ZnO | P0 | 51.68 | 3.2525 | 3.2525 | 5.2108 | 47.74 | 50 | 1.46 × 10−3 | P0 Χ = 77.09 I = 0.72 |

| P2.5 | 51.47 | 3.2524 | 3.2524 | 5.2106 | 47.73 | 63 | 1.63 × 10−3 | ||

| P5 | 57.12 | 3.2521 | 3.2521 | 5.2102 | 47.72 | 78 | 3.48 × 10−3 | P2.5 Χ = 78.74 I = 0.79 | |

| CeO2 | P0 | 48.32 | 5.4106 | 5.4106 | 5.4106 | 158.39 | 12 | 5.06 × 10−3 | |

| P2.5 | 48.53 | 5.4087 | 5.4087 | 5.4087 | 158.25 | 12 | 4.39 × 10−3 | P5 Χ = 76.92 I = 0.81 | |

| P5 | 42.88 | 5.4093 | 5.4093 | 5.4093 | 158.28 | 12 | 4.98 × 10−3 | ||

| Samples | O, at.% | Ce, at.% | Zn, at.% | Ce3+/Ce4+ OL/OH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0 | 62.0 | 13.8 | 24.2 | 0.0392.7 |

| P2.5 | 55.6 | 11.0 | 33.4 | 0.0541.7 |

| P5 | 63.9 | 17.9 | 18.2 | 0.0271.8 |

| Element, Atomic % | P0 | P2.5 | P5 | Element, Wt.% | P0 | P2.5 | P5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 19.63 | 23.00 | 22.07 | C | 5.17 | 6.51 | 6.33 |

| O | 37.85 | 38.68 | 37.59 | O | 13.28 | 14.57 | 14.36 |

| Zn | 29.97 | 27.01 | 31.21 | Zn | 42.97 | 41.58 | 48.74 |

| Ce | 12.55 | 11.32 | 9.13 | Ce | 38.58 | 37.34 | 30.57 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

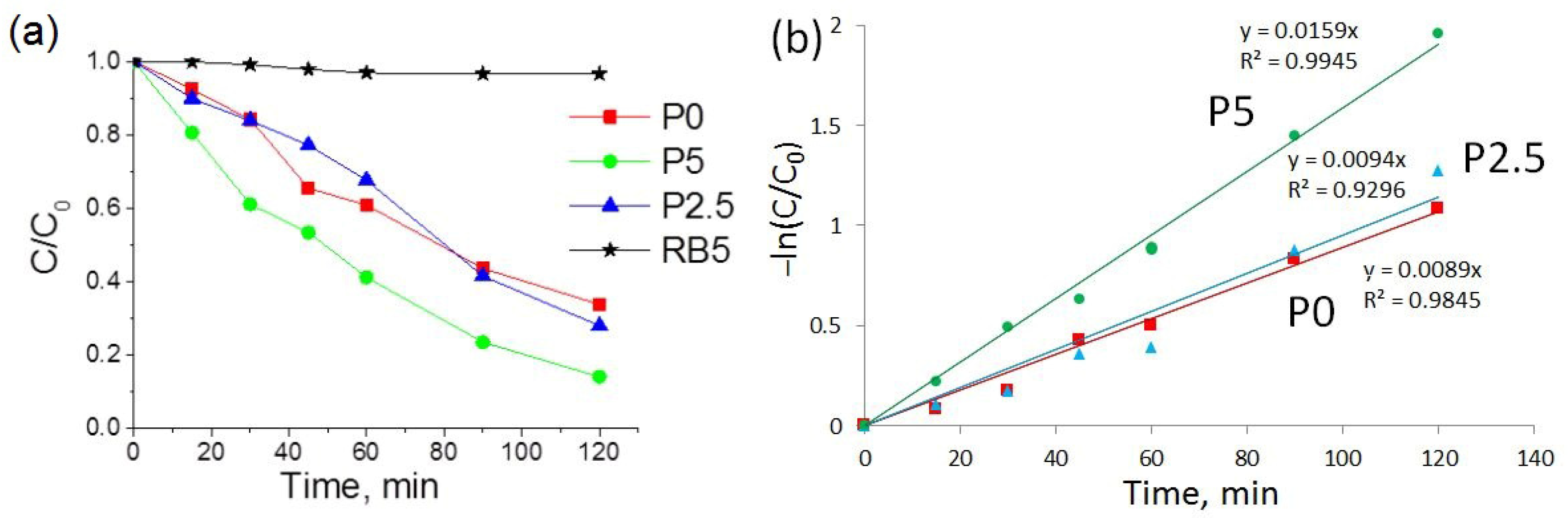

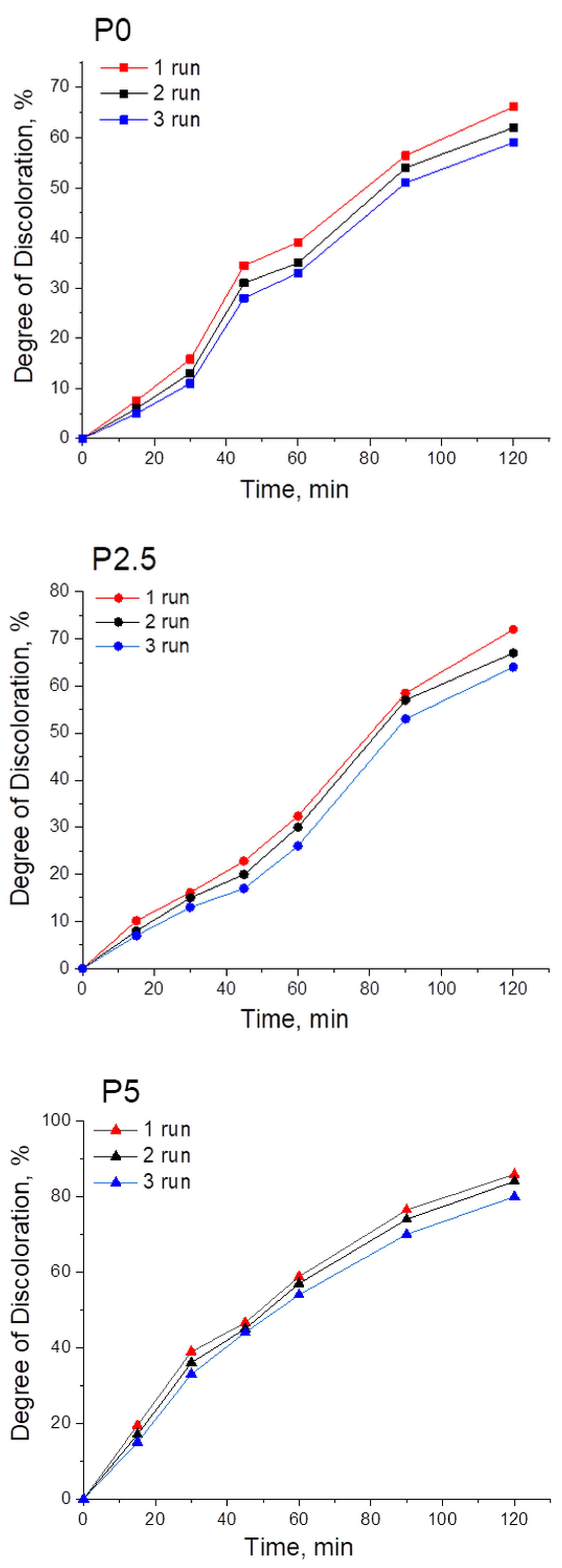

| Samples | Q (mg/g) | Degree of Discoloration (%) | kapp × 10−3 (min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P0 | 0.026 | 66 | 8.9 |

| P2.5 | 0.021 | 72 | 9.4 |

| P5 | 0.018 | 86 | 15.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaharieva, K.; Shipochka, M.; Stambolova, I.; Stoyanova, D.; Mladenova, R.; Markov, P.; Dimitrov, O.; Dimova, S.; Dimitrova, M. The Role of Pluronic Copolymer on the Physicochemical Characteristics of ZnO-CeO2 Photocatalysts. Crystals 2025, 15, 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121032

Zaharieva K, Shipochka M, Stambolova I, Stoyanova D, Mladenova R, Markov P, Dimitrov O, Dimova S, Dimitrova M. The Role of Pluronic Copolymer on the Physicochemical Characteristics of ZnO-CeO2 Photocatalysts. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121032

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaharieva, Katerina, Maria Shipochka, Irina Stambolova, Daniela Stoyanova, Ralitsa Mladenova, Pavel Markov, Ognian Dimitrov, Silvia Dimova, and Mariela Dimitrova. 2025. "The Role of Pluronic Copolymer on the Physicochemical Characteristics of ZnO-CeO2 Photocatalysts" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121032

APA StyleZaharieva, K., Shipochka, M., Stambolova, I., Stoyanova, D., Mladenova, R., Markov, P., Dimitrov, O., Dimova, S., & Dimitrova, M. (2025). The Role of Pluronic Copolymer on the Physicochemical Characteristics of ZnO-CeO2 Photocatalysts. Crystals, 15(12), 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121032