Sintering of Alumina-Reinforced Ceramics Using Low-Temperature Sintering Additive

Abstract

1. Introduction

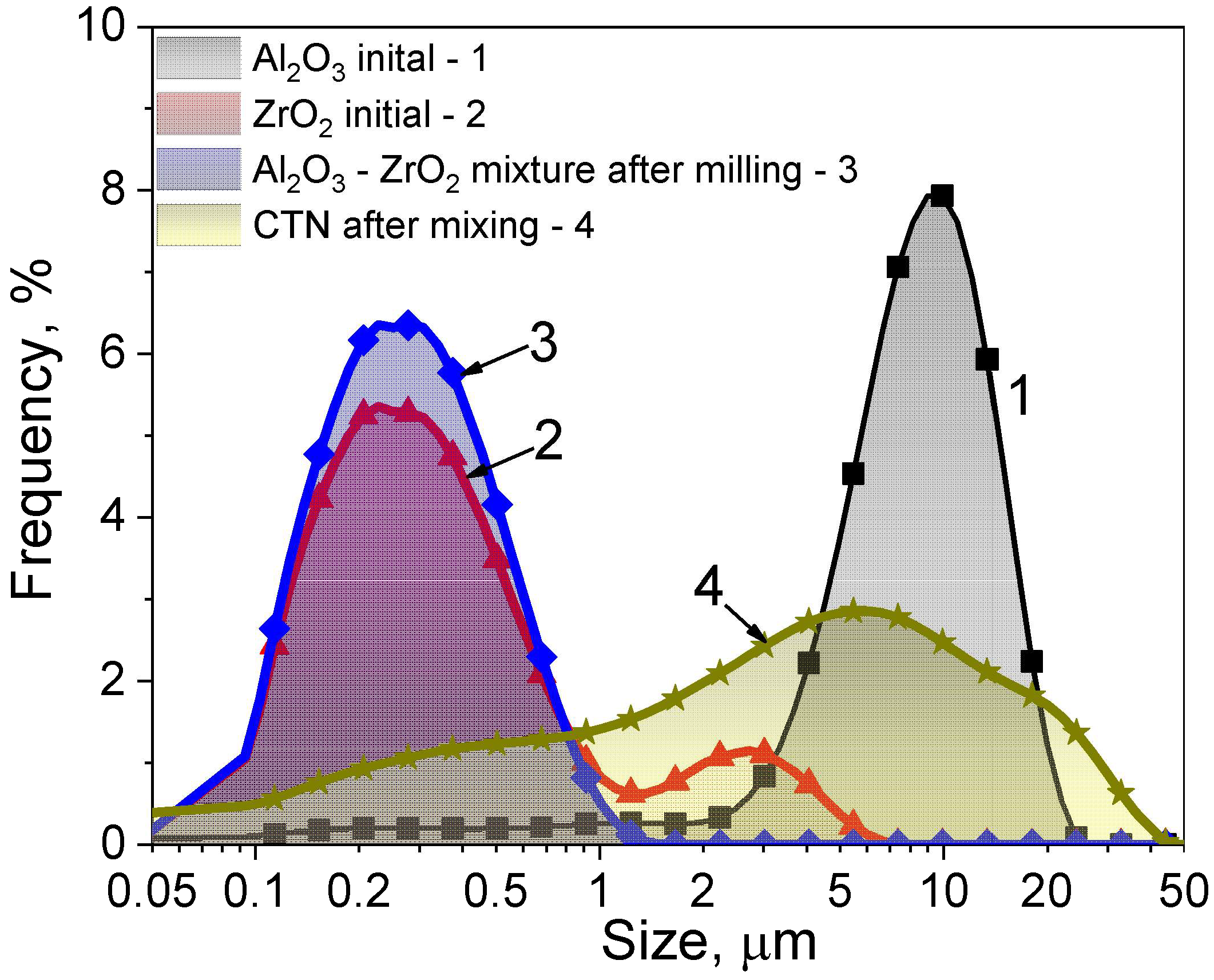

2. Materials and Methods

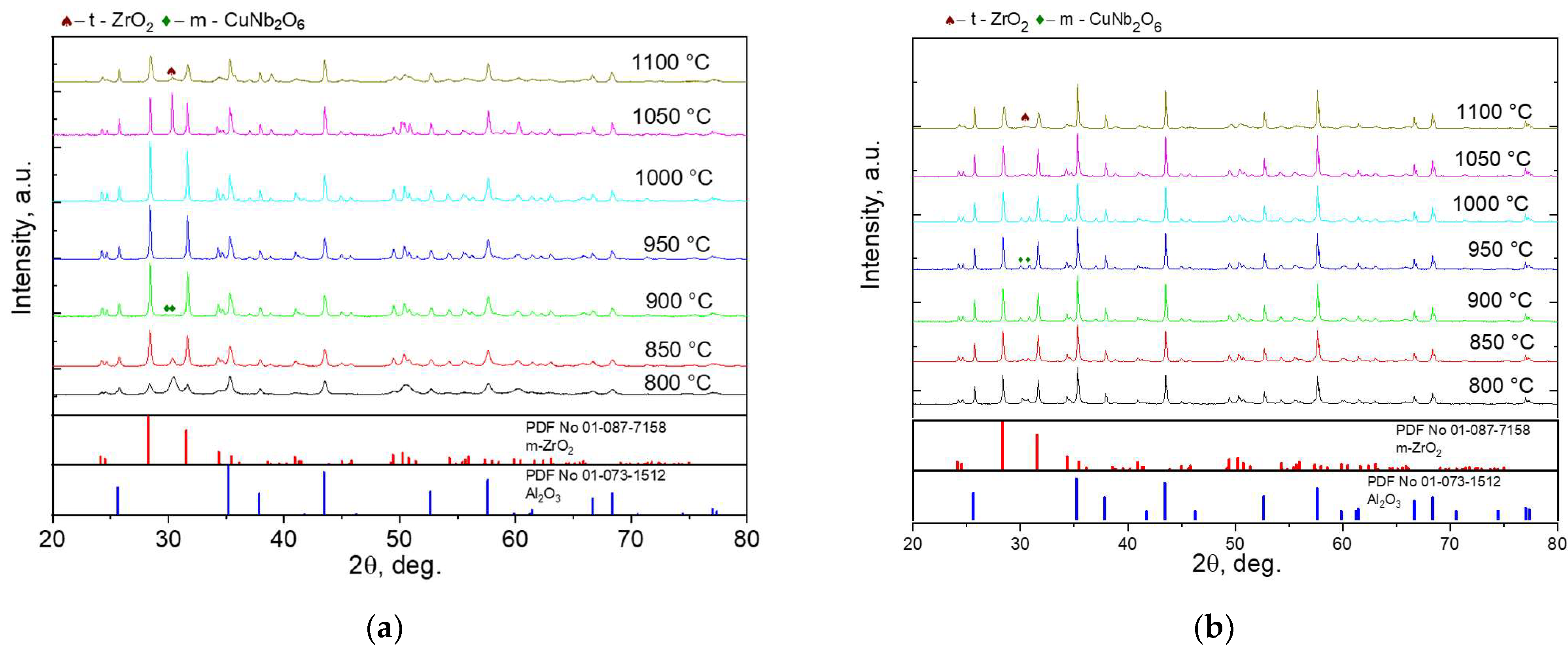

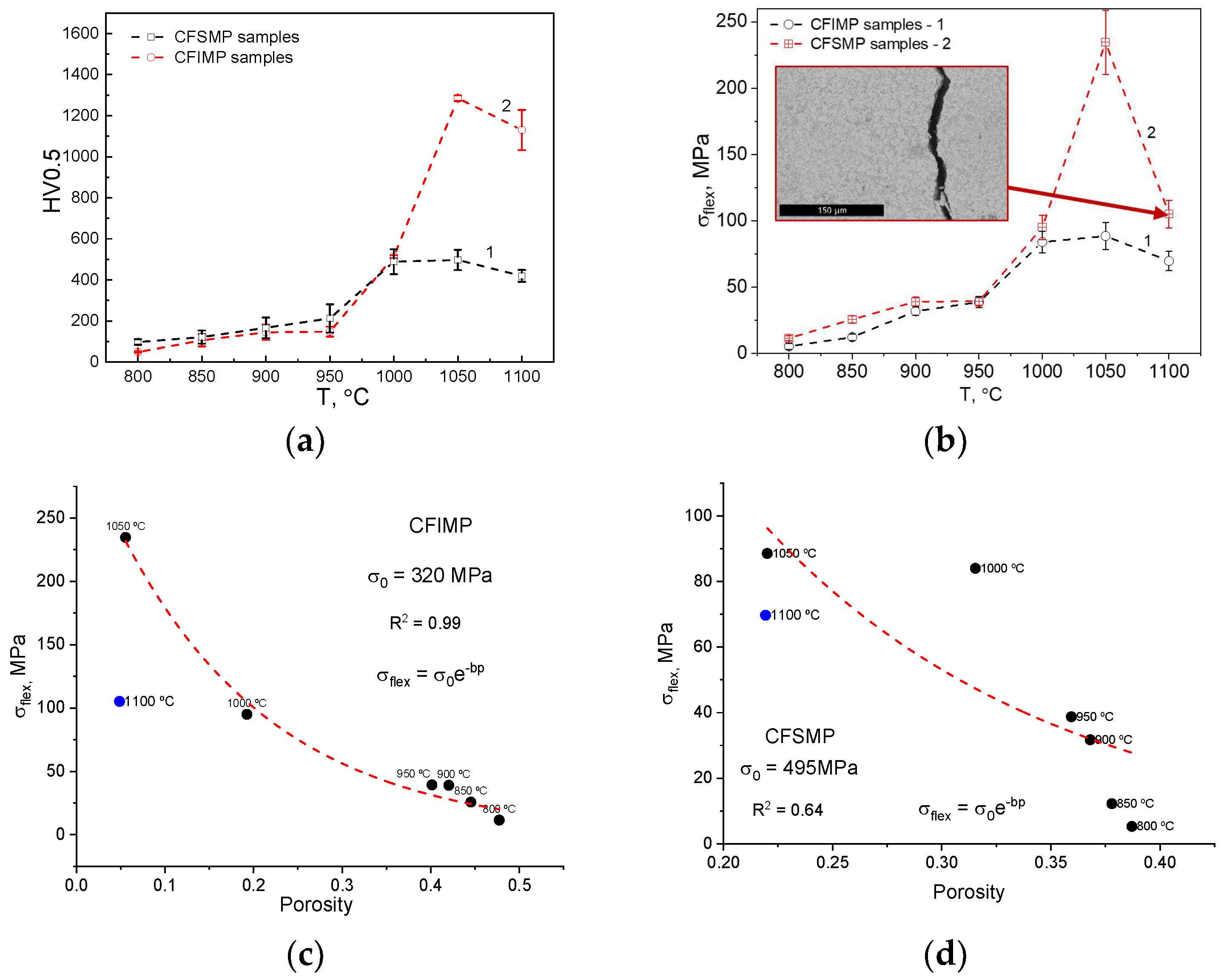

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ZTA | Zirconia toughened alumina |

| CTN | CuO-TiO2-Nb2O5 mixture |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| XRD | X-Ray diffraction |

| TGA | Thermal gravimetric analysis |

| Powder diffraction file | |

| FWHM | Full width at half maximum |

| HV | Hardness Vickers |

| CFSMP | Ceramics obtained from slightly milled powders |

| CFIMP | Ceramics obtained from intense milled powders |

References

- Mahajan, Y.R.; Johnson, R. Handbook of Advanced Ceramics and Composites: Defense, Security, Aerospace and Energy Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boch, P. Ceramic Materials: Processes, Properties and Applications; Nièpce, J.-C., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-905209-23-1. [Google Scholar]

- Abyzov, A.M. Aluminum Oxide and Alumina Ceramics (Review). Part 1. Properties of Al2O3 and Commercial Production of Dispersed Al2O3. Refract. Ind. Ceram. 2019, 60, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Nissan, B.; Choi, A.H.; Cordingley, R. Alumina Ceramics. Bioceram. Their Clin. Appl. 2008, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenzhina, I.E.; Kozlovskiy, A.L.; Begentayev, M.; Tolenova, A.; Askerbekov, S. Influence of the Change of Phase Composition of (1 − x)ZrO2–xAl2O3 Ceramics on the Resistance to Hydrogen Embrittlement. Materials 2023, 16, 7072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lei, L.; Zhang, J. Preparation of Alumina Ceramics via a Two-Step Sintering Process. Materials 2025, 18, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostishin, V.G.; Mironovich, A.Y.; Timofeev, A.V.; Isaev, I.M.; Shakirzyanov, R.I.; Skorlupin, G.A.; Ril, A.I. Influence of the Deposition Interruption on the Texture Degree of Barium Hexaferrite BaFe12O19 Films. Superlattices Microstruct. 2021, 158, 107005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barinov, S.M.; Ponomarev, V.F.; Shevchenko, V.Y. Effect of Hot Isostatic Pressing on the Mechanical Properties of Aluminum Oxide Ceramics. Refract. Ind. Ceram. 1997, 38, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadyrzhanov, D.B.; Kaliyekperov, M.E.; Idinov, M.T.; Kozlovskiy, A.L. Study of the Structural, Morphological, Strength and Shielding Properties of CuBi2O4 Films Obtained by Electrochemical Synthesis. Materials 2023, 16, 7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlovskiy, A.L.; Borgekov, D.B.; Zdorovets, M.V.; Kenzhina, I.E.; Shlimas, D.I. Study of Radiation Damage Kinetics in Dispersed Nuclear Fuel on Zirconium Dioxide Doped with Cerium Dioxide. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Han, G.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; et al. Preparation of Excellent Performance ZTA Ceramics and Complex Shaped Components Using Digital Light Processing 3D Printing Technology. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 980, 173640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sktani, Z.D.I.; Arab, A.; Mohamed, J.J.; Ahmad, Z.A. Effects of Additives Additions and Sintering Techniques on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Zirconia Toughened Alumina (ZTA): A Review. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2022, 106, 105870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.; Yang, Y.; Sui, Y.; Jiang, Y. Influence of CeO2 Addition on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Zirconia-Toughened Alumina (ZTA) Composite Prepared by Spark Plasma Sintering. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 7510–7516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejab, N.A.; Ahmad, Z.A.; Ab Rahman, M.F.; Su, N.K. ZTA Hardness Enhancement via Hot Isostatic Press Sintering. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1082, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.; Mumu, H.T.; Al-Amin, M.; Zahangir Alam, M.; Gafur, M.A. Impacts of Inclusion of Additives on Physical, Microstructural, and Mechanical Properties of Alumina and Zirconia Toughened Alumina (ZTA) Ceramic Composite: A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 2892–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomban, P. Chemical Preparation Routes and Lowering the Sintering Temperature of Ceramics. Ceramics 2020, 3, 312–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, R.; Chen, I.W. Ceramics Science and Technology; Wiley VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2010; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garanin, Y.; Shakirzyanov, R.; Borgekov, D.; Kozlovskiy, A.; Volodina, N.; Shlimas, D.; Zdorovets, M. Study of Morphology, Phase Composition, Optical Properties, and Thermal Stability of Hydrothermal Zirconium Dioxide Synthesized at Low Temperatures. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayode Otitoju, T.; Ugochukwu Okoye, P.; Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Onyeka Okoye, M.; Li, S. Advanced Ceramic Components: Materials, Fabrication, and Applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 85, 34–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, D. Chemical Synthesis of Ceramic Materials. J. Mater. Chem. 1997, 7, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Li, S.; Zhu, T.; Xie, Z. An Oscillatory Pressure Sintering of Zirconia Powder: Rapid Densification with Limited Grain Growth. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 100, 2774–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotza, D.; García, D.E.; Castro, R.H.R. Obtaining Highly Dense YSZ Nanoceramics by Pressureless, Unassisted Sintering. Int. Mater. Rev. 2015, 60, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lóh, N.J.; Simão, L.; Faller, C.A.; De Noni, A.; Montedo, O.R.K. A Review of Two-Step Sintering for Ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 12556–12572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Anil Kumar, V.; Khanra, G.P. Reactive and Liquid-Phase Sintering Techniques. Intermet. Matrix Compos. Prop. Appl. 2018, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironovich, A.Y.; Kostishin, V.G.; Al-Khafaji, H.I.; Timofeev, A.V.; Savchenko, E.S.; Ril, A.I. Submicron Barium Hexaferrite Ceramics Manufactured by Low-Temperature Liquid-Phase Sintering of BaFe12O19 Nanoparticles. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 69, 1637–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, M.; Zhang, F.; Liu, F.; Chen, G.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y. Low-Temperature Sintering of Al2O3 Ceramics Doped with 4CuO-TiO2-2Nb2O5 Composite Oxide Sintering Aid. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 5504–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeno, K.; Kuraoka, Y.; Asakawa, T.; Fujimori, H. Sintering Mechanism of Low-Temperature Co-Fired Alumina Featuring Superior Thermal Conductivity. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 104, 2017–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakirzyanov, R.I.; Volodina, N.O.; Kadyrzhanov, K.K.; Kozlovskiy, A.L.; Shlimas, D.I.; Baimbetova, G.A.; Borgekov, D.B.; Zdorovets, M.V. Study of the Aid Effect of CuO-TiO2-Nb2O5 on the Dielectric and Structural Properties of Alumina Ceramics. Materials 2023, 16, 5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenzhina, I.E.; Kozlovskiy, A.L.; Volodina, N.O.; Shakirzyanov, R.I.; Garanin, Y.A.; Maznykh, S.A.; Makhanov, K.M.; Tolenova, A.U.; Begentayev, M.; Askerbekov, S.K.; et al. Low-Temperature Sintering of Zirconia-Based Ceramic Composites for Capacitor Applications. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 33428–33440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.M.; Yap, A.U.J.; Chandra, S.P.; Lim, C.T. Flexural Strength of Dental Composite Restoratives: Comparison of Biaxial and Three-Point Bending Test. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2004, 71B, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Han, S.; Feng, W.; Kong, Q.; Dong, Z.; Wang, C.; Lei, J.; Yi, Q. The Effect of Heat Treatment on the Anatase–Rutile Phase Transformation and Photocatalytic Activity of Sn-Doped TiO2 Nanomaterials. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 14249–14257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadatkhah, N.; Carillo Garcia, A.; Ackermann, S.; Leclerc, P.; Latifi, M.; Samih, S.; Patience, G.S.; Chaouki, J. Experimental Methods in Chemical Engineering: Thermogravimetric Analysis—TGA. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 98, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshkalam, M.; Faghihi-Sani, M.A.; Nojoomi, A. Effect of Zirconia Content and Powder Processing on Mechanical Properties of Gelcasted ZTA Composite. Trans. Indian Ceram. Soc. 2013, 72, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafur, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.; Sarker, M.S.R.; Alam, M.Z.; Gafur, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.; Sarker, M.S.R.; Alam, M.Z. Structural and Mechanical Properties of Alumina-Zirconia (ZTA) Composites with Unstabilized Zirconia Modulation. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2021, 12, 542–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, D.; Singh, F.; Das, R. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis by Williamson-Hall, Halder-Wagner and Size-Strain Plot Methods of CdSe Nanoparticles- a Comparative Study. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 239, 122021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlevaris, D.; Varriale, F.; Wahlström, J.; Menapace, C. Pin-on-Disc Tribological Characterization of Single Ingredients Used in a Brake Pad Friction Material. Friction 2024, 12, 2576–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X. Probabilistic Relation between Stress Intensity and Fracture Toughness in Ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 20558–20564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Gong, J. Effect of Porosity on the Microhardness Testing of Brittle Ceramics: A Case Study on the System of NiO–ZrO2. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 8751–8759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfahed, B.; Alayad, A. The Effect of Sintering Temperature on Vickers Microhardness and Flexural Strength of Translucent Multi-Layered Zirconia Dental Materials. Coatings 2023, 13, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternero, F.; Rosa, L.G.; Urban, P.; Montes, J.M.; Cuevas, F.G. Influence of the Total Porosity on the Properties of Sintered Materials—A Review. Metals 2021, 11, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Stevens, R. Zirconia-Toughened Alumina (ZTA) Ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. 1989, 24, 3421–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, R.N.; Subbarao, E.C. Monoclinic–Tetragonal Phase Transition in Zirconia: Mechanism, Pretransformation and Coexistence. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 1970, 26, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K.; Yoshida, H.; Ikuhara, Y. Review: Microstructure-Development Mechanism during Sintering in Polycrystalline Zirconia. Int. Mater. Rev. 2018, 63, 375–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burelli, M.; Maschio, S.; Lucchini, E. Strength and Toughness of Alumina--Zirconia Ceramics under Biaxial Stress. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 1997, 16, 661–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjaj, M.S.; Alamoudi, R.A.A.; Babeer, W.A.; Rizg, W.Y.; Basalah, A.A.; Alzahrani, S.J.; Yeslam, H.E. Flexural Strength, Flexural Modulus and Microhardness of Milled vs. Fused Deposition Modeling Printed Zirconia; Effect of Conventional vs. Speed Sintering. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetzler, S.; Hinzen, C.; Rues, S.; Schmitt, C.; Rammelsberg, P.; Zenthöfer, A. Biaxial Flexural Strength and Vickers Hardness of 3D-Printed and Milled 5Y Partially Stabilized Zirconia. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenthöfer, A.; Ilani, A.; Schmitt, C.; Rammelsberg, P.; Hetzler, S.; Rues, S. Biaxial Flexural Strength of 3D-Printed 3Y-TZP Zirconia Using a Novel Ceramic Printer. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulyk, V.; Vasyliv, B.; Duriagina, Z.; Lyutyy, P.; Vavrukh, V.; Kostryzhev, A. The Effect of Sintering Temperature on Phase-Related Peculiarities of the Microstructure, Flexural Strength, and Fracture Toughness of Fine-Grained ZrO2–Y2O3–Al2O3–CoO–CeO2–Fe2O3 Ceramics. Crystals 2024, 14, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Ts, °C | d1, mm | h1, mm | d2, mm | h2, mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFSMP | 800 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.57 ± 0.01 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.58 ± 0.01 |

| 850 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.57 ± 0.01 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.56 ± 0.01 | |

| 900 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.72 ± 0.01 | 11.9 ± 0.05 | 1.71 ± 0.01 | |

| 950 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.58 ± 0.01 | 11.8 ± 0.05 | 1.56 ± 0.01 | |

| 1000 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.58 ± 0.01 | 11.5 ± 0.05 | 1.55 ± 0.01 | |

| 1050 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.41 ± 0.01 | 11 ± 0.05 | 1.34 ± 0.01 | |

| 1100 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.58 ± 0.01 | 11 ± 0.05 | 1.47 ± 0.01 | |

| CFIMP | 800 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.92 ± 0.01 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.88 ± 0.01 |

| 850 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.89 ± 0.01 | 11.8 ± 0.05 | 1.84 ± 0.01 | |

| 900 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.83 ± 0.01 | 11.7 ± 0.05 | 1.75 ± 0.01 | |

| 950 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.89 ± 0.01 | 11.4 ± 0.05 | 1.8 ± 0.01 | |

| 1000 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.86 ± 0.01 | 10.4 ± 0.05 | 1.6 ± 0.01 | |

| 1050 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.86 ± 0.01 | 9.7 ± 0.05 | 1.6 ± 0.01 | |

| 1100 | 12 ± 0.05 | 1.82 ± 0.01 | 9.75 ± 0.05 | 1.47 ± 0.01 |

| Sintering Temperature, °C | Peak | FWHM, ° | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFSMP | CFIMP | ||

| 800 °C | ZrO2 (11-1) | 0.16582 | 0.357048 |

| Al2O3 (104) | 0.07517 | 0.403192 | |

| 850 °C | ZrO2 (11-1) | 0.17217 | 0.227048 |

| Al2O3 (104) | 0.0821 | 0.365838 | |

| 900 °C | ZrO2 (11-1) | 0.16129 | 0.169464 |

| Al2O3 (104) | 0.06311 | 0.18524 | |

| 950 °C | ZrO2 (11-1) | 0.16457 | 0.157724 |

| Al2O3 (104) | 0.07062 | 0.18503 | |

| 1000 °C | ZrO2 (11-1) | 0.16988 | 0.138214 |

| Al2O3 (104) | 0.08117 | 0.12883 | |

| 1050 °C | ZrO2 (11-1) | 0.16332 | 0.133682 |

| Al2O3 (104) | 0.07132 | 0.090018 | |

| 1100 °C | ZrO2 (11-1) | 0.26553 | 0.22735 |

| Al2O3 (104) | 0.0733 | 0.12579 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garanin, Y.A.; Shakirzyanov, R.I.; Kaliyekperov, M.E. Sintering of Alumina-Reinforced Ceramics Using Low-Temperature Sintering Additive. Crystals 2025, 15, 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110949

Garanin YA, Shakirzyanov RI, Kaliyekperov ME. Sintering of Alumina-Reinforced Ceramics Using Low-Temperature Sintering Additive. Crystals. 2025; 15(11):949. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110949

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaranin, Yuriy Alexandrovich, Rafael Iosifovich Shakirzyanov, and Malik Erlanovich Kaliyekperov. 2025. "Sintering of Alumina-Reinforced Ceramics Using Low-Temperature Sintering Additive" Crystals 15, no. 11: 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110949

APA StyleGaranin, Y. A., Shakirzyanov, R. I., & Kaliyekperov, M. E. (2025). Sintering of Alumina-Reinforced Ceramics Using Low-Temperature Sintering Additive. Crystals, 15(11), 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110949