Centrosymmetric Double-Q Skyrmion Crystals Under Uniaxial Distortion and Bond-Dependent Anisotropy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model and Method

3. Results

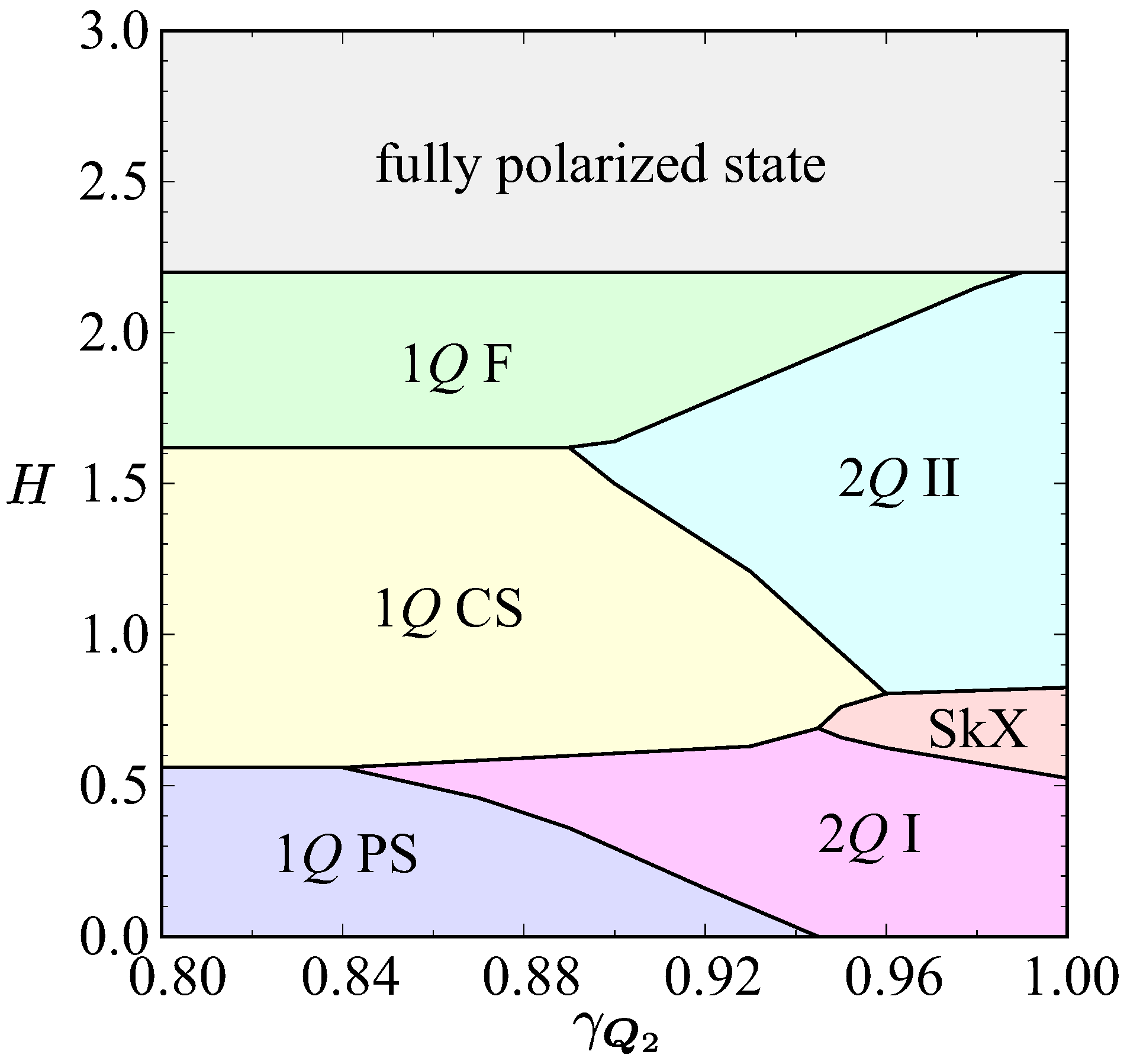

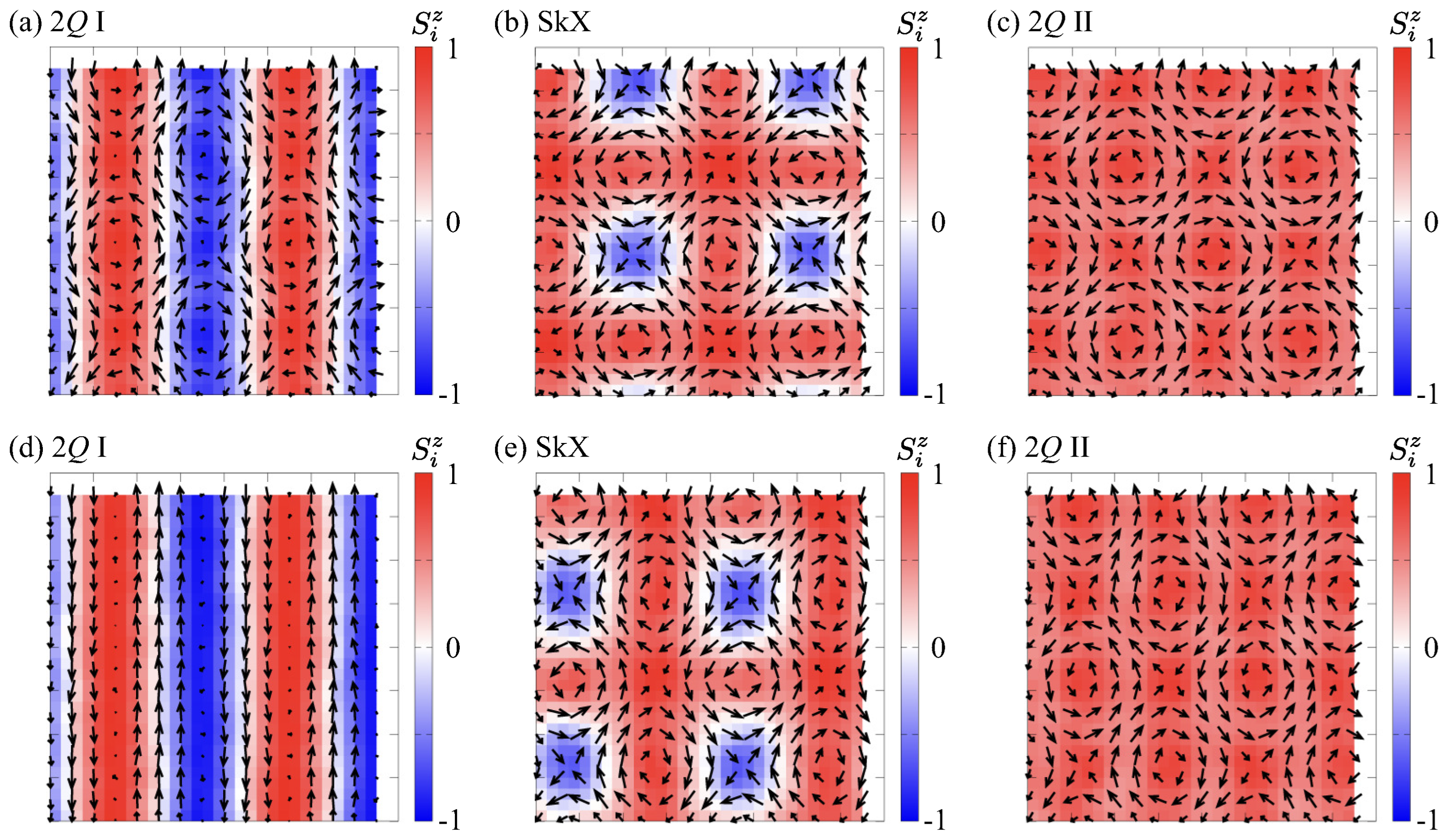

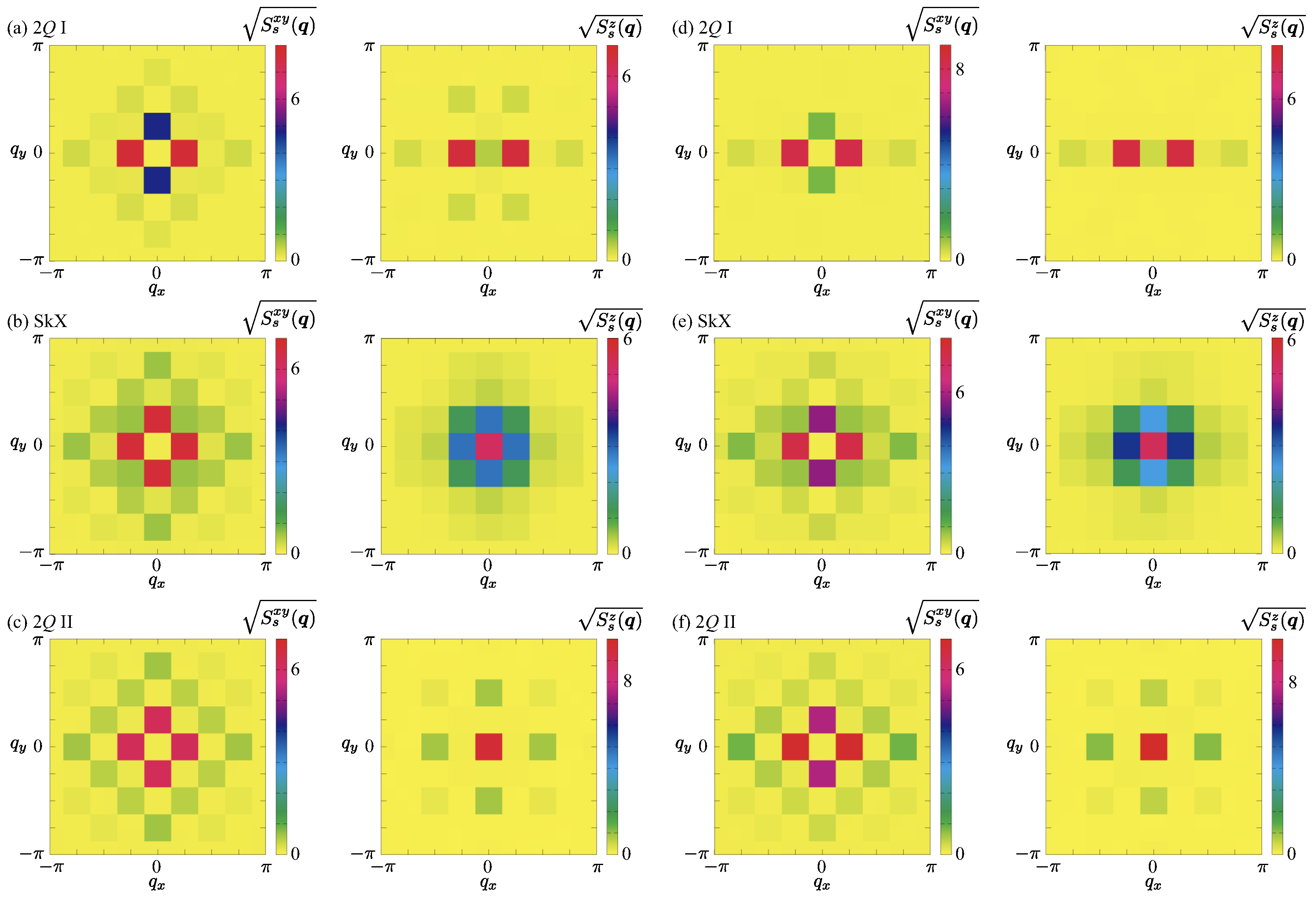

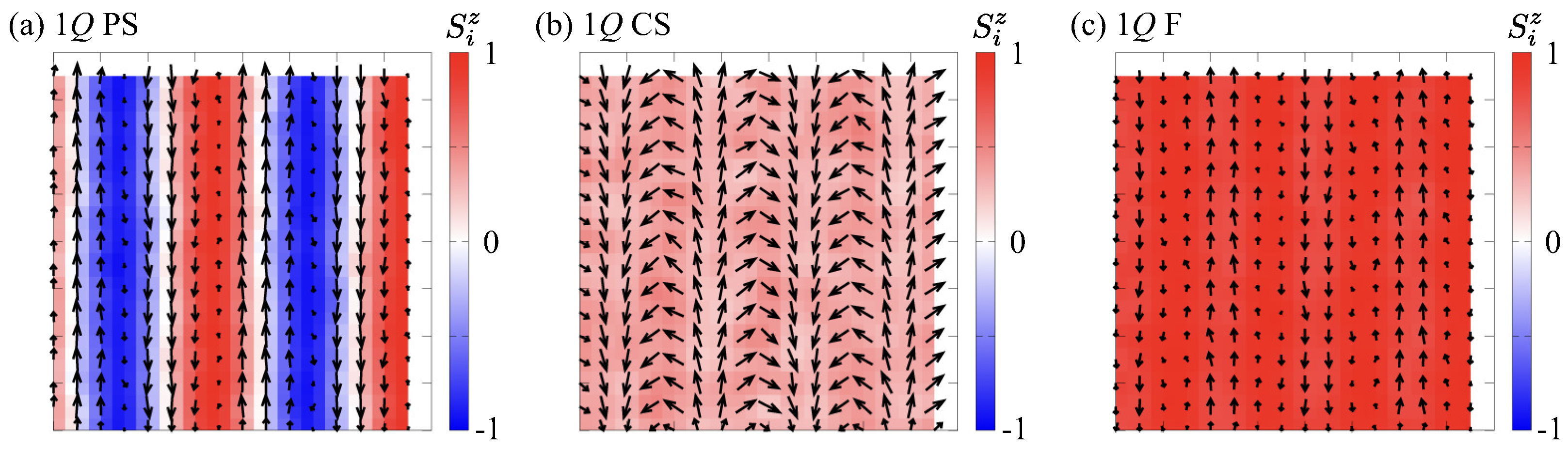

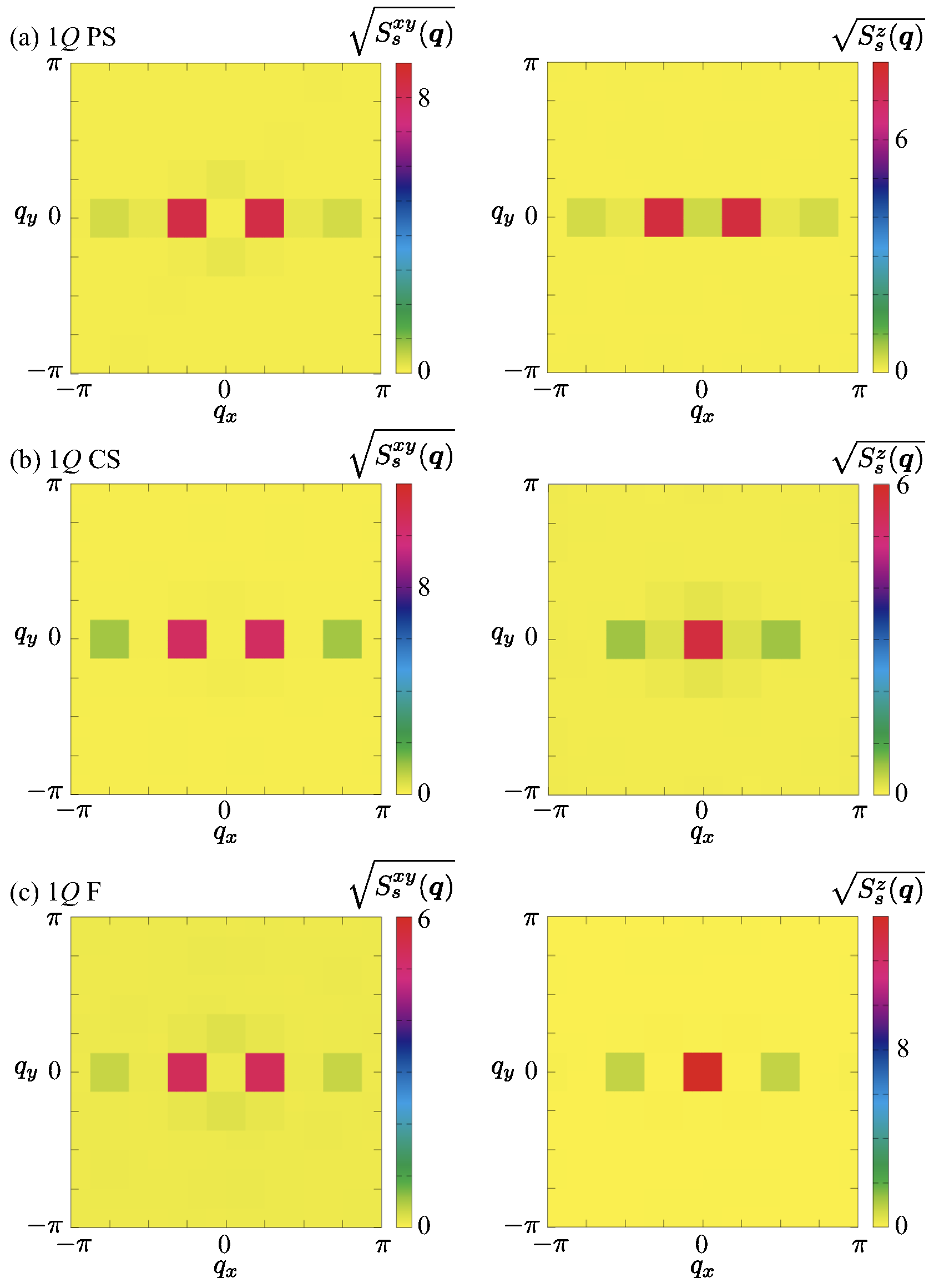

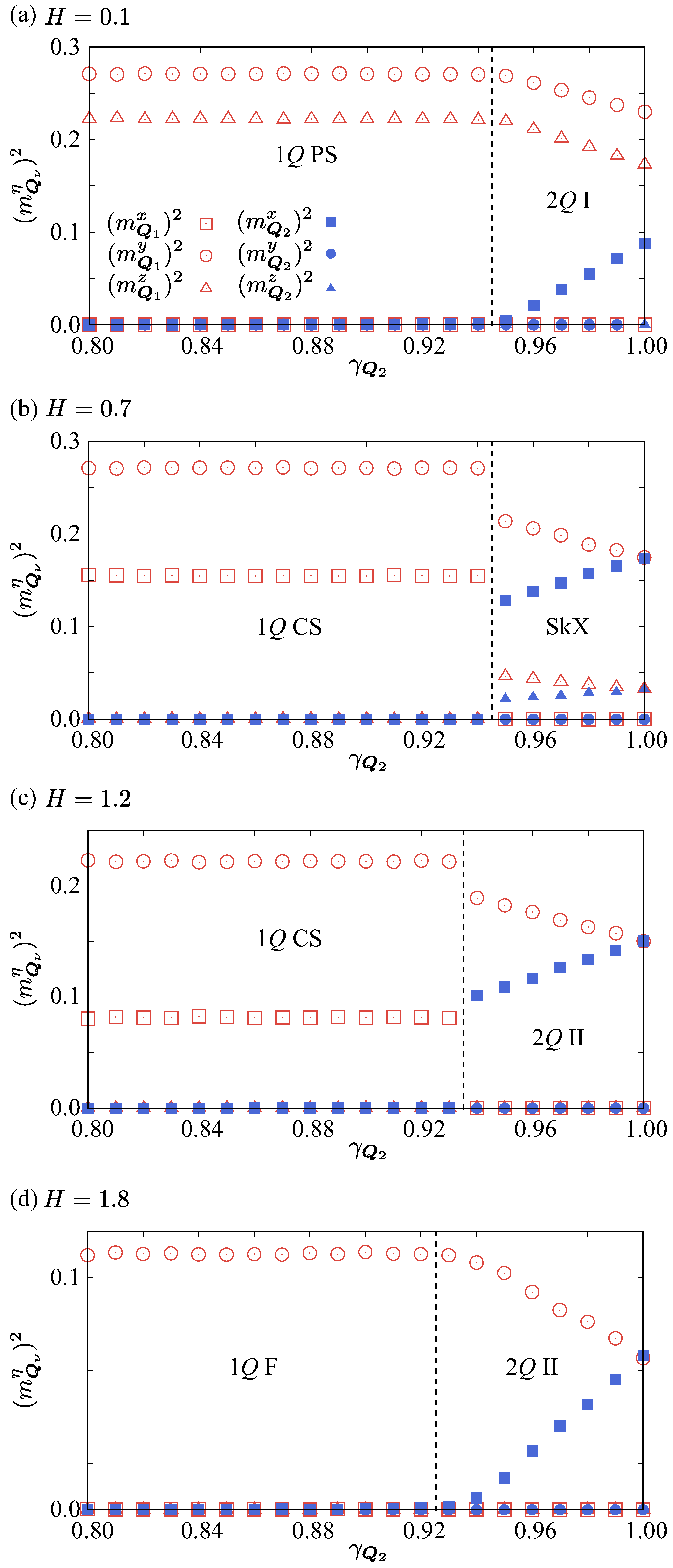

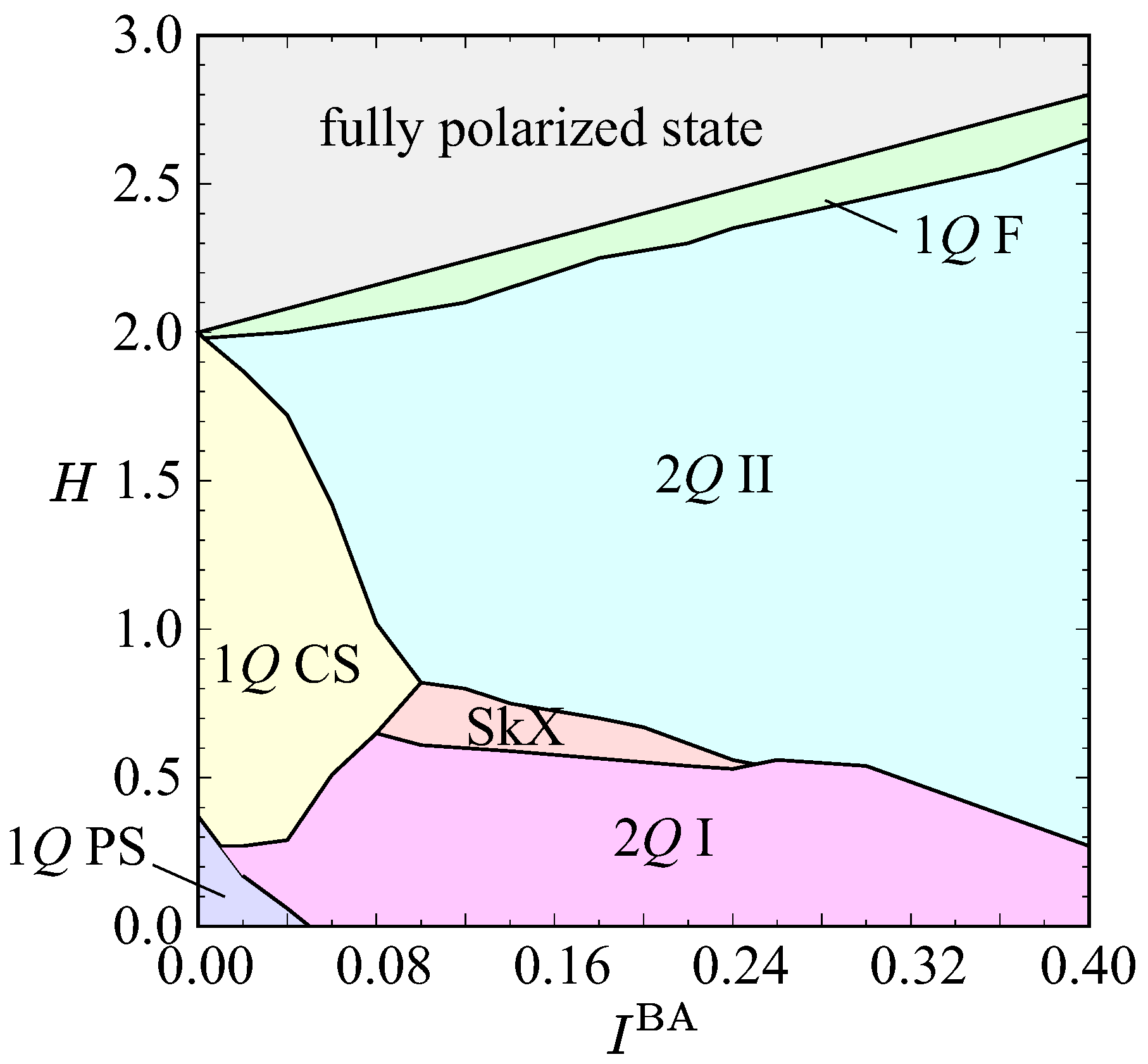

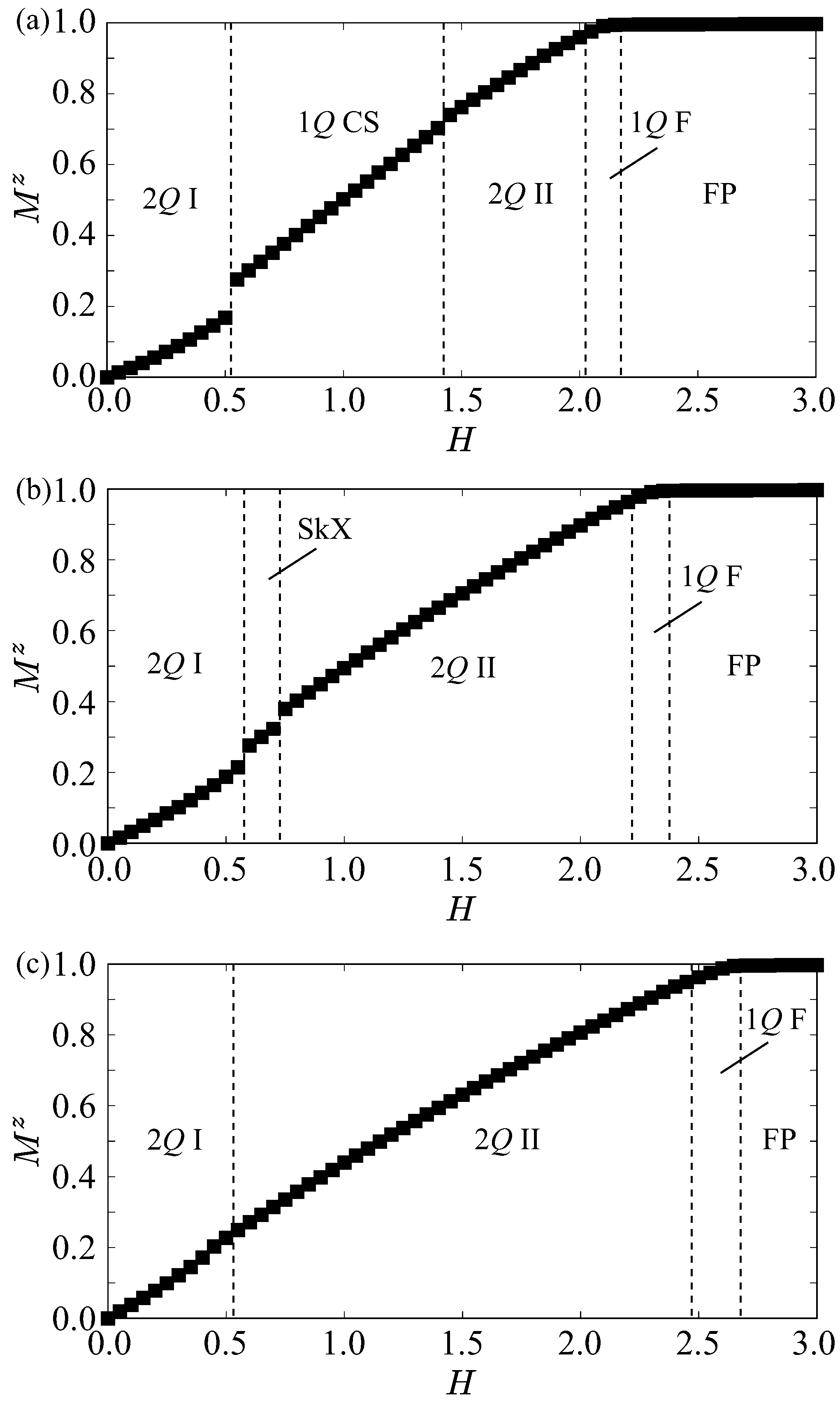

3.1. Effect of Uniaxial Distortion

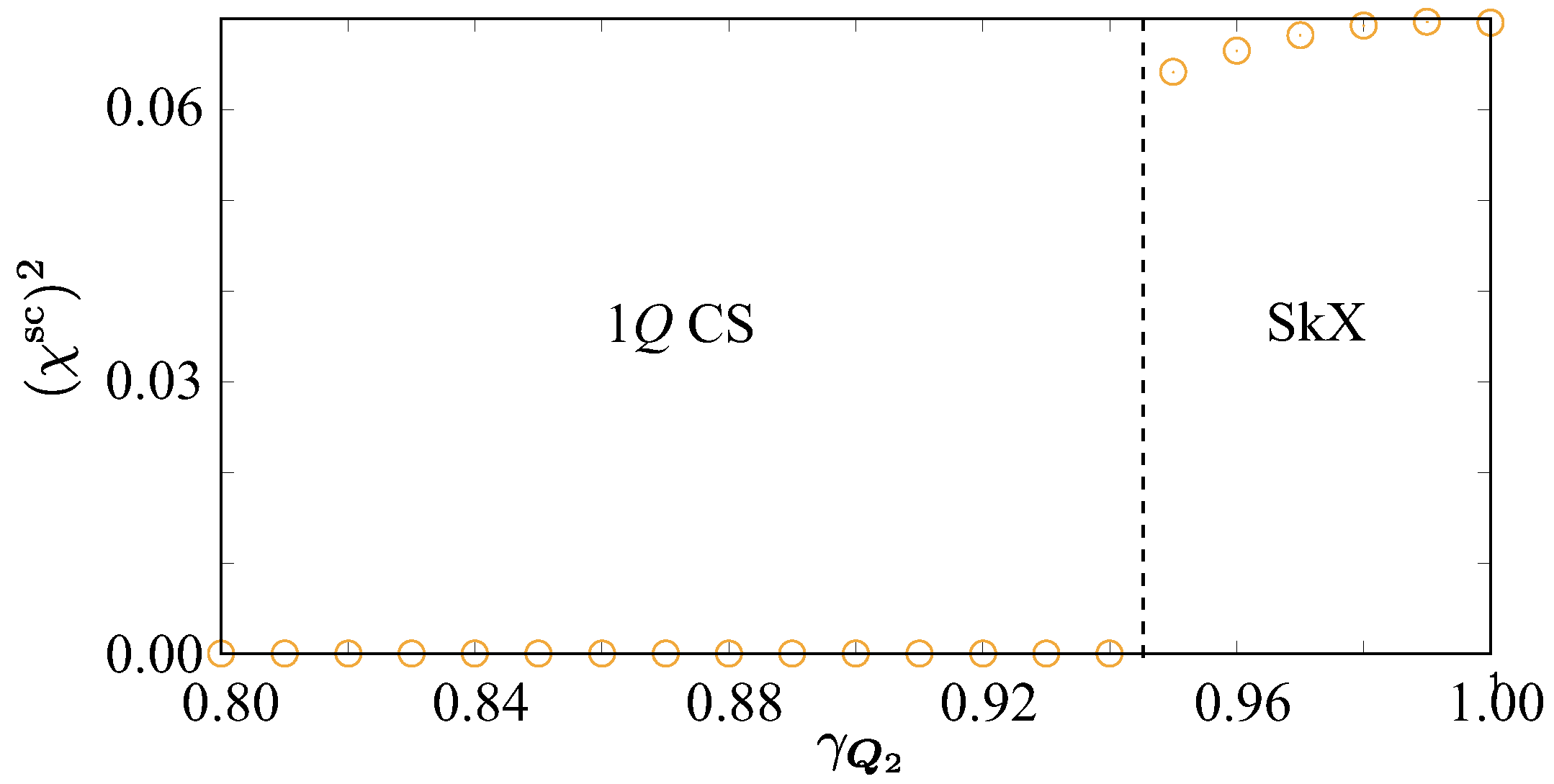

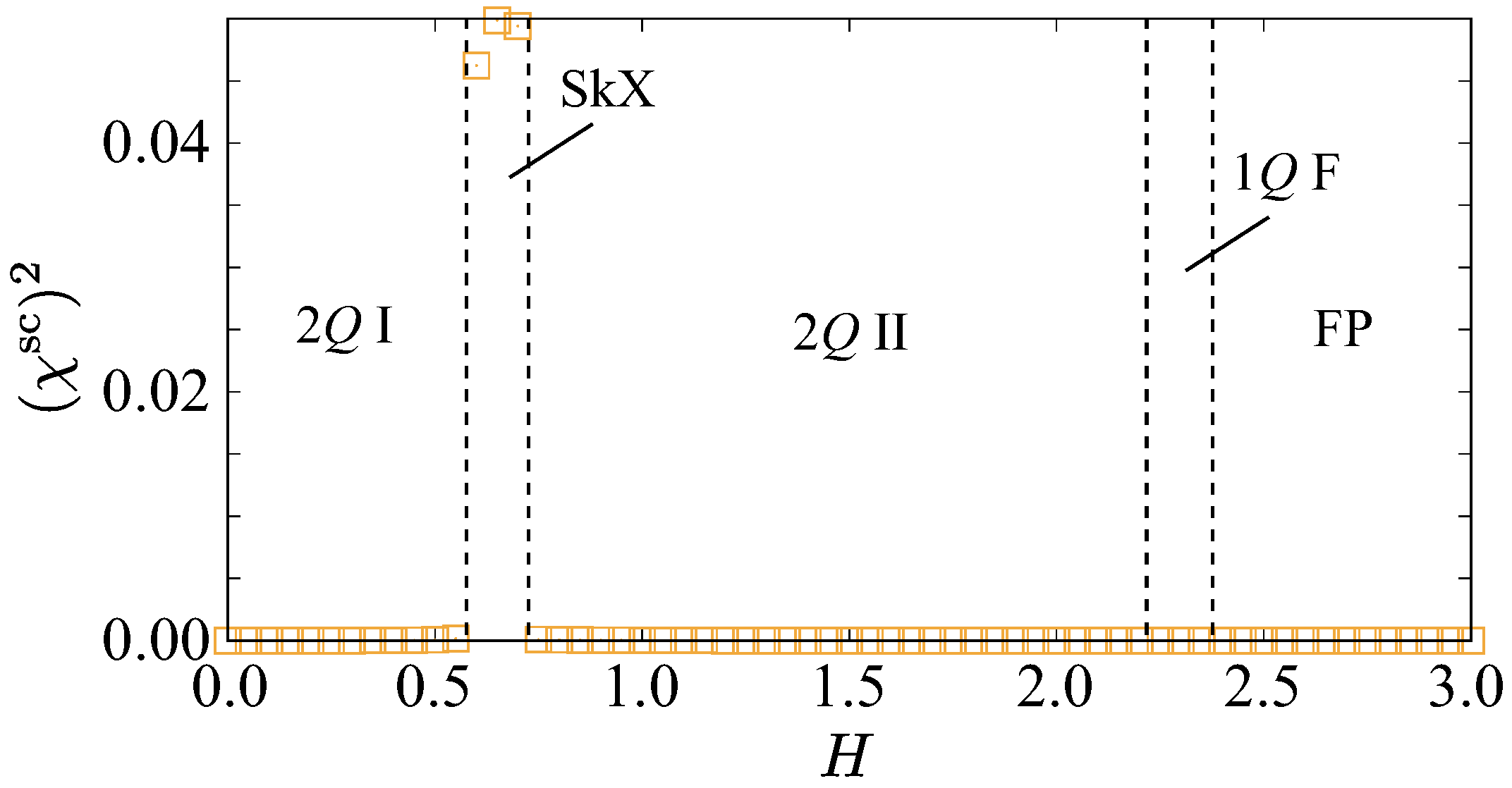

3.2. Effect of Bond-Dependent Anisotropy

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skyrme, T. A non-linear field theory. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1961, 260, 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Skyrme, T.H.R. A unified field theory of mesons and baryons. Nucl. Phys. 1962, 31, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.C.; Mermin, N.D. Crystalline liquids: The blue phases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1989, 61, 385–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, A.O.; Dragunov, I.E.; Rößler, U.K.; Bogdanov, A.N. Theory of skyrmion states in liquid crystals. Phys. Rev. E 2014, 90, 042502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afghah, S.; Selinger, J.V. Theory of helicoids and skyrmions in confined cholesteric liquid crystals. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 96, 012708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duzgun, A.; Selinger, J.V.; Saxena, A. Comparing skyrmions and merons in chiral liquid crystals and magnets. Phys. Rev. E 2018, 97, 062706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duzgun, A.; Nisoli, C. Skyrmion Spin Ice in Liquid Crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 047801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondhi, S.L.; Karlhede, A.; Kivelson, S.A.; Rezayi, E.H. Skyrmions and the crossover from the integer to fractional quantum Hall effect at small Zeeman energies. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 16419–16426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abolfath, M.; Palacios, J.J.; Fertig, H.A.; Girvin, S.M.; MacDonald, A.H. Critical comparison of classical field theory and microscopic wave functions for skyrmions in quantum Hall ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 56, 6795–6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.C.; He, S. Skyrmion excitations in quantum Hall systems. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 53, 1046–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Magnus force on skyrmions in ferromagnets and quantum Hall systems. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 53, 16573–16578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertig, H.A.; Brey, L.; Côté, R.; MacDonald, A.H.; Karlhede, A.; Sondhi, S.L. Hartree-Fock theory of Skyrmions in quantum Hall ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 55, 10671–10680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shkolnikov, Y.P.; Misra, S.; Bishop, N.C.; De Poortere, E.P.; Shayegan, M. Observation of Quantum Hall “Valley Skyrmions”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 066809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Das Sarma, S.; MacDonald, A.H. Collective modes and skyrmion excitations in graphene SU(4) quantum Hall ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 075423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.L. Spinor Bose Condensates in Optical Traps. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 742–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khawaja, U.; Stoof, H. Skyrmions in a ferromagnetic Bose-Einstein condensate. Nature 2001, 411, 918–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, U.A.; Stoof, H.T.C. Skyrmion physics in Bose-Einstein ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. A 2001, 64, 043612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruostekoski, J.; Anglin, J.R. Creating Vortex Rings and Three-Dimensional Skyrmions in Bose-Einstein Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 3934–3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battye, R.A.; Cooper, N.R.; Sutcliffe, P.M. Stable Skyrmions in Two-Component Bose-Einstein Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 080401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, C.M.; Ruostekoski, J. Energetically Stable Particlelike Skyrmions in a Trapped Bose-Einstein Condensate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 010403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbauer, S.; Binz, B.; Jonietz, F.; Pfleiderer, C.; Rosch, A.; Neubauer, A.; Georgii, R.; Böni, P. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science 2009, 323, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Z.; Onose, Y.; Kanazawa, N.; Park, J.H.; Han, J.H.; Matsui, Y.; Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Real-space observation of a two-dimensional skyrmion crystal. Nature 2010, 465, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.; Mühlbauer, S.; Neubauer, A.; Münzer, W.; Jonietz, F.; Georgii, R.; Pedersen, B.; Böni, P.; Rosch, A.; Pfleiderer, C. Skyrmion lattice domains in Fe1-xCoxSi. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2010, 200, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, A.; Pfleiderer, C.; Binz, B.; Rosch, A.; Ritz, R.; Niklowitz, P.G.; Böni, P. Topological Hall Effect in the A Phase of MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 186602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanov, A.N.; Yablonskii, D.A. Thermodynamically stable “vortices” in magnetically ordered crystals: The mixed state of magnets. Sov. Phys. JETP 1989, 68, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, A.; Hubert, A. Thermodynamically stable magnetic vortex states in magnetic crystals. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1994, 138, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rößler, U.K.; Bogdanov, A.N.; Pfleiderer, C. Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals. Nature 2006, 442, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokura, Y.; Kanazawa, N. Magnetic Skyrmion Materials. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fert, A.; Cros, V.; Sampaio, J. Skyrmions on the track. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, W. Skyrmion-electronics: An overview and outlook. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 2040–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finocchio, G.; Büttner, F.; Tomasello, R.; Carpentieri, M.; Kläui, M. Magnetic skyrmions: From fundamental to applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2016, 49, 423001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fert, A.; Reyren, N.; Cros, V. Magnetic skyrmions: Advances in physics and potential applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 17031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Song, K.M.; Park, T.E.; Xia, J.; Ezawa, M.; Liu, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, G.; Woo, S. Skyrmion-electronics: Writing, deleting, reading and processing magnetic skyrmions toward spintronic applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2020, 32, 143001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, A.N.; Panagopoulos, C. Physical foundations and basic properties of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2020, 2, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichhardt, C.; Reichhardt, C.J.O.; Milošević, M.V. Statics and dynamics of skyrmions interacting with disorder and nanostructures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2022, 94, 035005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everschor, K.; Garst, M.; Duine, R.A.; Rosch, A. Current-induced rotational torques in the skyrmion lattice phase of chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 064401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everschor, K.; Garst, M.; Binz, B.; Jonietz, F.; Mühlbauer, S.; Pfleiderer, C.; Rosch, A. Rotating skyrmion lattices by spin torques and field or temperature gradients. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 054432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, M. Spin-Wave Modes and Their Intense Excitation Effects in Skyrmion Crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 017601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatara, G.; Fukuyama, H. Phasons and excitations in skyrmion lattice. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2014, 83, 104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.Z.; Batista, C.D.; Saxena, A. Internal modes of a skyrmion in the ferromagnetic state of chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 024415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garst, M.; Waizner, J.; Grundler, D. Collective spin excitations of helices and magnetic skyrmions: Review and perspectives of magnonics in non-centrosymmetric magnets. J. Phys. D 2017, 50, 293002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhang, X.; Yu, G.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Benjamin Jungfleisch, M.; Pearson, J.E.; Cheng, X.; Heinonen, O.; Wang, K.L.; et al. Direct observation of the skyrmion Hall effect. Nat. Phys. 2017, 13, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litzius, K.; Lemesh, I.; Krüger, B.; Bassirian, P.; Caretta, L.; Richter, K.; Büttner, F.; Sato, K.; Tretiakov, O.A.; Förster, J.; et al. Skyrmion Hall effect revealed by direct time-resolved X-ray microscopy. Nat. Phys. 2017, 13, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.W.; Moon, K.W.; Kerber, N.; Nothhelfer, J.; Everschor-Sitte, K. Asymmetric skyrmion Hall effect in systems with a hybrid Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 224427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikov, A.G.; Stebliy, M.E.; Samardak, A.S.; Ognev, A.V. Skyrmionium–high velocity without the skyrmion Hall effect. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juge, R.; Je, S.G.; Chaves, D.d.S.; Buda-Prejbeanu, L.D.; Peña Garcia, J.; Nath, J.; Miron, I.M.; Rana, K.G.; Aballe, L.; Foerster, M.; et al. Current-Driven Skyrmion Dynamics and Drive-Dependent Skyrmion Hall Effect in an Ultrathin Film. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2019, 12, 044007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, B.; Mook, A.; Henk, J.; Mertig, I. Overcoming the speed limit in skyrmion racetrack devices by suppressing the skyrmion Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 020405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattouhi, M.; García-Sánchez, F.; Yanes, R.; Raposo, V.; Martínez, E.; Lopez-Diaz, L. Electric Field Control of the Skyrmion Hall Effect in Piezoelectric-Magnetic Devices. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2021, 16, 044035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.M. Quantum skyrmion Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 109, 155123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Saidi, W.; Sbiaa, R. Controlling skyrmion Hall effect dynamics in constricted ferromagnetic nanowires. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2025, 614, 172768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.D.; Onoda, S.; Nagaosa, N.; Han, J.H. Skyrmions and anomalous Hall effect in a Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya spiral magnet. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 054416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binz, B.; Vishwanath, A.; Aji, V. Theory of the Helical Spin Crystal: A Candidate for the Partially Ordered State of MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 207202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binz, B.; Vishwanath, A. Theory of helical spin crystals: Phases, textures, and properties. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 214408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Okubo, T.; Motome, Y. Phase shift in skyrmion crystals. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzyaloshinsky, I. A thermodynamic theory of “weak” ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1958, 4, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriya, T. Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 1960, 120, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, S.; von Bergmann, K.; Menzel, M.; Brede, J.; Kubetzka, A.; Wiesendanger, R.; Bihlmayer, G.; Blügel, S. Spontaneous atomic-scale magnetic skyrmion lattice in two dimensions. Nat. Phys. 2011, 7, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, T.; Chung, S.; Kawamura, H. Multiple-q States and the Skyrmion Lattice of the Triangular-Lattice Heisenberg Antiferromagnet under Magnetic Fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 017206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, A.O.; Mostovoy, M. Multiply periodic states and isolated skyrmions in an anisotropic frustrated magnet. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Lin, S.Z.; Kamiya, Y.; Batista, C.D. Vortices, skyrmions, and chirality waves in frustrated Mott insulators with a quenched periodic array of impurities. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 174420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. In-plane magnetic field-induced skyrmion crystal in frustrated magnets with easy-plane anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 224418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, H. Frustration-induced skyrmion crystals in centrosymmetric magnets. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2025, 37, 183004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butenko, A.B.; Leonov, A.A.; Rößler, U.K.; Bogdanov, A.N. Stabilization of skyrmion textures by uniaxial distortions in noncentrosymmetric cubic helimagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 052403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.N.; Butenko, A.B.; Bogdanov, A.N.; Monchesky, T.L. Chiral skyrmions in cubic helimagnet films: The role of uniaxial anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 094411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.Z.; Saxena, A.; Batista, C.D. Skyrmion fractionalization and merons in chiral magnets with easy-plane anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 224407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, A.O.; Monchesky, T.L.; Romming, N.; Kubetzka, A.; Bogdanov, A.N.; Wiesendanger, R. The properties of isolated chiral skyrmions in thin magnetic films. New J. Phys. 2016, 18, 065003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, D.; Stasinopoulos, I.; Tsurkan, V.; Krug von Nidda, H.A.; Fehér, T.; Leonov, A.; Kézsmárki, I.; Grundler, D.; Loidl, A. Skyrmion dynamics under uniaxial anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 014406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, A.O.; Kézsmárki, I. Skyrmion robustness in noncentrosymmetric magnets with axial symmetry: The role of anisotropy and tilted magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96, 214413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Motome, Y. Effect of magnetic anisotropy on skyrmions with a high topological number in itinerant magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 094420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, B.; Philipp, S.; Geirhos, K.; Mehlin, A.; Bordács, S.; Tsurkan, V.; Leonov, A.; Kézsmárki, I.; Poggio, M. Stability of Néel-type skyrmion lattice against oblique magnetic fields in GaV4S8 and GaV4Se8. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 102, 104407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Stabilization mechanisms of magnetic skyrmion crystal and multiple-Q states based on momentum-resolved spin interactions. Mater. Today Quantum 2024, 3, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, Y.; Yu, X.; White, J.; Rønnow, H.M.; Morikawa, D.; Taguchi, Y.; Tokura, Y. A new class of chiral materials hosting magnetic skyrmions beyond room temperature. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karube, K.; White, J.; Reynolds, N.; Gavilano, J.; Oike, H.; Kikkawa, A.; Kagawa, F.; Tokunaga, Y.; Rønnow, H.M.; Tokura, Y.; et al. Robust metastable skyrmions and their triangular–square lattice structural transition in a high-temperature chiral magnet. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karube, K.; White, J.S.; Morikawa, D.; Dewhurst, C.D.; Cubitt, R.; Kikkawa, A.; Yu, X.; Tokunaga, Y.; Arima, T.H.; Rønnow, H.M.; et al. Disordered skyrmion phase stabilized by magnetic frustration in a chiral magnet. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaar7043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karube, K.; White, J.S.; Ukleev, V.; Dewhurst, C.D.; Cubitt, R.; Kikkawa, A.; Tokunaga, Y.; Rønnow, H.M.; Tokura, Y.; Taguchi, Y. Metastable skyrmion lattices governed by magnetic disorder and anisotropy in β-Mn-type chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 102, 064408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.E.; Bleuel, M.; Beare, J.; Cory, D.G.; Heacock, B.; Huber, M.G.; Luke, G.M.; Pula, M.; Sarenac, D.; Sharma, S.; et al. Skyrmion alignment and pinning effects in the disordered multiphase skyrmion material Co8Zn8Mn4. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 094435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacon, A.; Heinen, L.; Halder, M.; Bauer, A.; Simeth, W.; Mühlbauer, S.; Berger, H.; Garst, M.; Rosch, A.; Pfleiderer, C. Observation of two independent skyrmion phases in a chiral magnetic material. Nat. Phys. 2018, 14, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, R.; Yamasaki, Y.; Yokouchi, T.; Ukleev, V.; Yokoyama, Y.; Nakao, H.; Arima, T.; Tokura, Y.; Seki, S. Particle-size dependent structural transformation of skyrmion lattice. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanh, N.D.; Nakajima, T.; Yu, X.; Gao, S.; Shibata, K.; Hirschberger, M.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; Peng, L.; et al. Nanometric square skyrmion lattice in a centrosymmetric tetragonal magnet. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanh, N.D.; Nakajima, T.; Hayami, S.; Gao, S.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; Takagi, R.; Motome, Y.; Tokura, Y.; et al. Zoology of Multiple-Q Spin Textures in a Centrosymmetric Tetragonal Magnet with Itinerant Electrons. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2105452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuyama, N.; Nomura, T.; Imajo, S.; Nomoto, T.; Arita, R.; Sudo, K.; Kimata, M.; Khanh, N.D.; Takagi, R.; Tokura, Y.; et al. Quantum oscillations in the centrosymmetric skyrmion-hosting magnet GdRu2Si2. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 107, 104421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, G.D.A.; Khalyavin, D.D.; Mayoh, D.A.; Bouaziz, J.; Hall, A.E.; Holt, S.J.R.; Orlandi, F.; Manuel, P.; Blügel, S.; Staunton, J.B.; et al. Double-Q ground state with topological charge stripes in the centrosymmetric skyrmion candidate GdRu2Si2. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 107, L180402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremeev, S.; Glazkova, D.; Poelchen, G.; Kraiker, A.; Ali, K.; Tarasov, A.V.; Schulz, S.; Kliemt, K.; Chulkov, E.V.; Stolyarov, V.; et al. Insight into the electronic structure of the centrosymmetric skyrmion magnet GdRu2Si2. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 6678–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Kinoshita, Y.; Ochi, M.; Nakachi, R.; Higashinaka, R.; Hayami, S.; Wan, Y.; Arai, Y.; Huh, S.; Hashimoto, M.; et al. Pseudogap and Fermi arc induced by Fermi surface nesting in a centrosymmetric skyrmion magnet. Science 2025, 388, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimochi, H.; Takagi, R.; Ju, J.; Khanh, N.; Saito, H.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; Itoh, S.; Tokura, Y.; Arima, T.; et al. Multistep topological transitions among meron and skyrmion crystals in a centrosymmetric magnet. Nat. Phys. 2024, 20, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Multiple skyrmion crystal phases by itinerant frustration in centrosymmetric tetragonal magnets. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2022, 91, 023705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Rectangular and square skyrmion crystals on a centrosymmetric square lattice with easy-axis anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 174437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Su, Y.; Lin, S.Z.; Batista, C.D. Meron, skyrmion, and vortex crystals in centrosymmetric tetragonal magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 104408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Helicity locking of a square skyrmion crystal in a centrosymmetric lattice system without vertical mirror symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 104428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utesov, O.I. Thermodynamically stable skyrmion lattice in a tetragonal frustrated antiferromagnet with dipolar interaction. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 064414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Skyrmion crystal and spiral phases in centrosymmetric bilayer magnets with staggered Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 014408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.Z. Skyrmion lattice in centrosymmetric magnets with local Dzyaloshinsky-Moriya interaction. Mater. Today Quantum 2024, 2, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, A.N.; Rößler, U.K. Chiral Symmetry Breaking in Magnetic Thin Films and Multilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 87, 037203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, K.; Iwasaki, J.; Kanazawa, N.; Aizawa, S.; Tanigaki, T.; Shirai, M.; Nakajima, T.; Kubota, M.; Kawasaki, M.; Park, H.; et al. Large anisotropic deformation of skyrmions in strained crystal. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015, 10, 589–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, Y.; Kamlah, M. Uniaxial strain modulation of the skyrmion phase transition in ferromagnetic thin films. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 024429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, S.A.; Sturla, M.B.; Rosales, H.D.; Cabra, D.C. From skyrmions to Z2 vortices in distorted chiral antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 220404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hog, S.; Kato, F.; Koibuchi, H.; Diep, H.T. Finsler geometry modeling and Monte Carlo study of skyrmion shape deformation by uniaxial stress. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 104, 024402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, T.; Xu, Y.; Gawryluk, D.J.; Ma, J.Z.; Shiroka, T.; Shi, M.; Pomjakushina, E. Anomalous Hall resistivity and possible topological Hall effect in the EuAl4 antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, L020405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Kawasaki, T.; Nakamura, A.; Munakata, K.; Nakao, A.; Hanashima, T.; Kiyanagi, R.; Ohhara, T.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; et al. Charge-Density-Wave Order and Multiple Magnetic Transitions in Divalent Europium Compound EuAl4. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2021, 90, 064704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, S.; Murao, H.; Tsutsui, S.; Nakao, H.; Nakamura, A.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; Ōnuki, Y. Lattice modulation and structural phase transition in the antiferromagnet EuAl4. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 88, 014602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gen, M.; Takagi, R.; Watanabe, Y.; Kitou, S.; Sagayama, H.; Matsuyama, N.; Kohama, Y.; Ikeda, A.; Ōnuki, Y.; Kurumaji, T.; et al. Rhombic skyrmion lattice coupled with orthorhombic structural distortion in EuAl4. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 107, L020410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsuji, S.; Nambu, Y.; Tonomura, H.; Sakai, O.; Jonas, S.; Broholm, C.; Tsunetsugu, H.; Qiu, Y.; Maeno, Y. Spin disorder on a triangular lattice. Science 2005, 309, 1697–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, P.; Moore, M.W.; Wilkinson, C.; Ziebeck, K.R.A. Neutron diffraction study of the incommensurate magnetic phase of Ni0.92Zn0.08Br2. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1981, 14, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnault, L.; Rossat-Mignod, J.; Adam, A.; Billerey, D.; Terrier, C. Inelastic neutron scattering investigation of the magnetic excitations in the helimagnetic state of NiBr2. J. Phys. 1982, 43, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, N.; Ronning, F.; Williams, D.; Scott, B.; Luo, Y.; Thompson, J.; Bauer, E. Investigation of the physical properties of the tetragonal CeMAl4Si2 (M= Rh, Ir, Pt) compounds. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2014, 27, 025601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunasekera, J.; Harriger, L.; Dahal, A.; Maurya, A.; Heitmann, T.; Disseler, S.M.; Thamizhavel, A.; Dhar, S.; Singh, D.J.; Singh, D.K. Electronic nature of the lock-in magnetic transition in CeXAl4Si2. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 155151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimori, A. A new type of antiferromagnetic structure in the rutile type crystal. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1959, 14, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, T.A. Some Effects of Anisotropy on Spiral Spin-Configurations with Application to Rare-Earth Metals. Phys. Rev. 1961, 124, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.J. Phenomenological Discussion of Magnetic Ordering in the Heavy Rare-Earth Metals. Phys. Rev. 1961, 124, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruderman, M.A.; Kittel, C. Indirect Exchange Coupling of Nuclear Magnetic Moments by Conduction Electrons. Phys. Rev. 1954, 96, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuya, T. A Theory of Metallic Ferro- and Antiferromagnetism on Zener’s Model. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1956, 16, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosida, K. Magnetic Properties of Cu-Mn Alloys. Phys. Rev. 1957, 106, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yambe, R.; Hayami, S. Effective spin model in momentum space: Toward a systematic understanding of multiple-Q instability by momentum-resolved anisotropic exchange interactions. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 174437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Motome, Y. Noncoplanar multiple-Q spin textures by itinerant frustration: Effects of single-ion anisotropy and bond-dependent anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 054422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberger, M.; Hayami, S.; Tokura, Y. Nanometric skyrmion lattice from anisotropic exchange interactions in a centrosymmetric host. New J. Phys. 2021, 23, 023039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, D.; Barone, P.; Picozzi, S. Spontaneous skyrmionic lattice from anisotropic symmetric exchange in a Ni-halide monolayer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yambe, R.; Hayami, S. Skyrmion crystals in centrosymmetric itinerant magnets without horizontal mirror plane. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, D.; Barone, P.; Picozzi, S. Interplay between Single-Ion and Two-Ion Anisotropies in Frustrated 2D Semiconductors and Tuning of Magnetic Structures Topology. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.; Hermanns, M.; Bauer, B.; Garst, M.; Trebst, S. Spin-orbit physics of j=12 Mott insulators on the triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 155135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousochatzakis, I.; Rössler, U.K.; van den Brink, J.; Daghofer, M. Kitaev anisotropy induces mesoscopic Z2 vortex crystals in frustrated hexagonal antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 104417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yu, R.; Wang, X. Semiclassical ground-state phase diagram and multi-Q phase of a spin-orbit-coupled model on triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 174424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chern, G.W.; Sizyuk, Y.; Price, C.; Perkins, N.B. Kitaev-Heisenberg model in a magnetic field: Order-by-disorder and commensurate-incommensurate transitions. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95, 144427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Orthorhombic distortion and rectangular skyrmion crystal in a centrosymmetric tetragonal host. J. Phys. Mater. 2023, 6, 014006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Kato, Y. Widely-sweeping magnetic field–temperature phase diagrams for skyrmion-hosting centrosymmetric tetragonal magnets. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2023, 571, 170547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Degeneracy Lifting of Néel, Bloch, and Anti-Skyrmion Crystals in Centrosymmetric Tetragonal Systems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2020, 89, 103702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okigami, K.; Hayami, S. Exploring topological spin order by inverse Hamiltonian design: A stabilization mechanism for square skyrmion crystals. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 110, L220405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hayami, S. Centrosymmetric Double-Q Skyrmion Crystals Under Uniaxial Distortion and Bond-Dependent Anisotropy. Crystals 2025, 15, 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110930

Hayami S. Centrosymmetric Double-Q Skyrmion Crystals Under Uniaxial Distortion and Bond-Dependent Anisotropy. Crystals. 2025; 15(11):930. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110930

Chicago/Turabian StyleHayami, Satoru. 2025. "Centrosymmetric Double-Q Skyrmion Crystals Under Uniaxial Distortion and Bond-Dependent Anisotropy" Crystals 15, no. 11: 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110930

APA StyleHayami, S. (2025). Centrosymmetric Double-Q Skyrmion Crystals Under Uniaxial Distortion and Bond-Dependent Anisotropy. Crystals, 15(11), 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110930