Efficient and Thorough Oxidation of Bisphenol A via Non-Radical Pathways Activated by SOx2−-Modified Mn2O3

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of SO-Mn2O3

2.3. Catalytic Degradation and Quenching Experiments

2.3.1. Active Oxidizing Species Detection

2.3.2. Detection of •OH Radicals

2.3.3. Detection of Singlet Oxygen (1O2)

2.3.4. Detection of SO4•− Radicals

2.3.5. Detection of High-Valent Metal Ions

3. Results

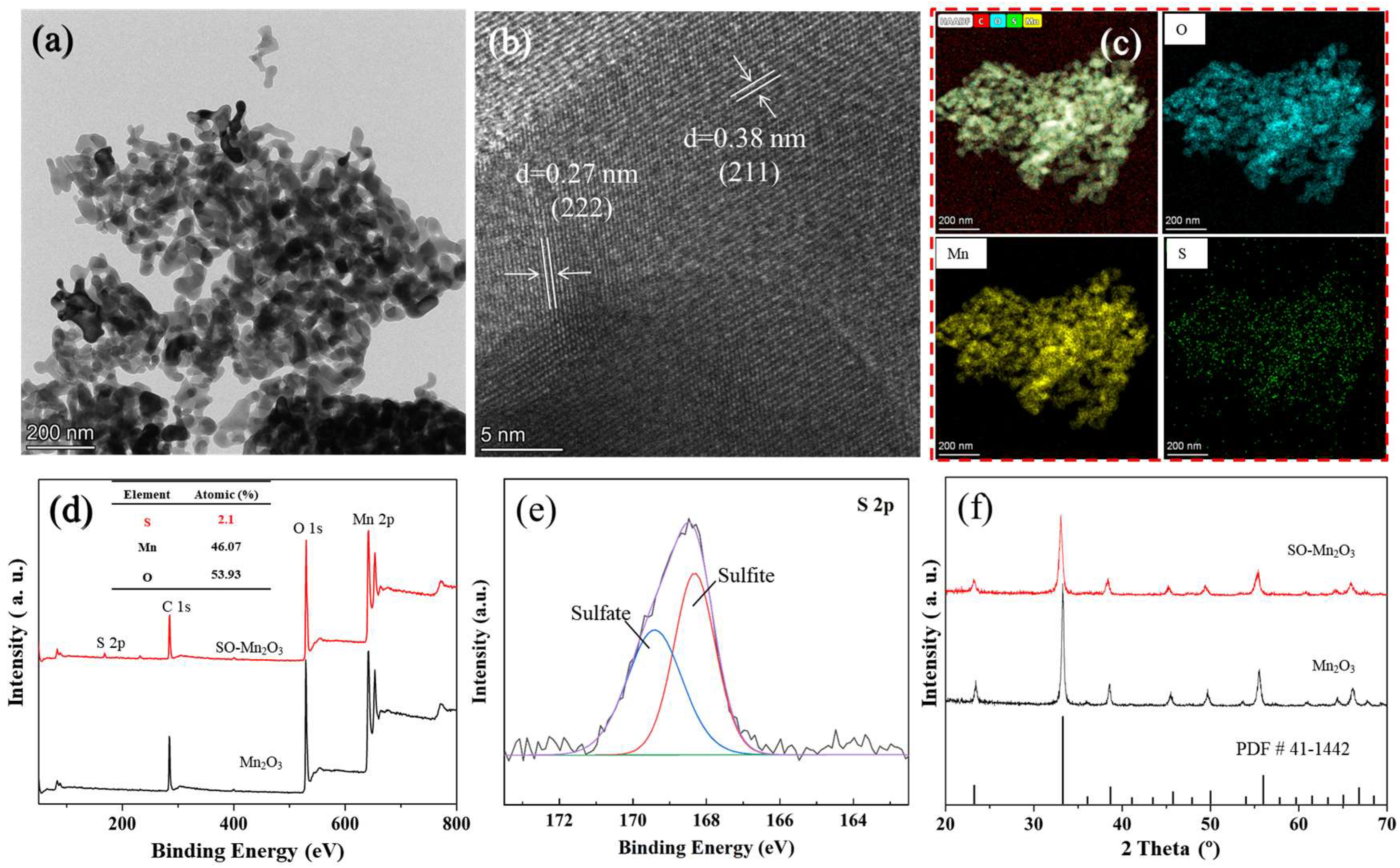

3.1. Structure and Chemical Composition of Mn2O3 and SO-Mn2O3

3.2. Catalytic Performance of Mn2O3 and SO-Mn2O3

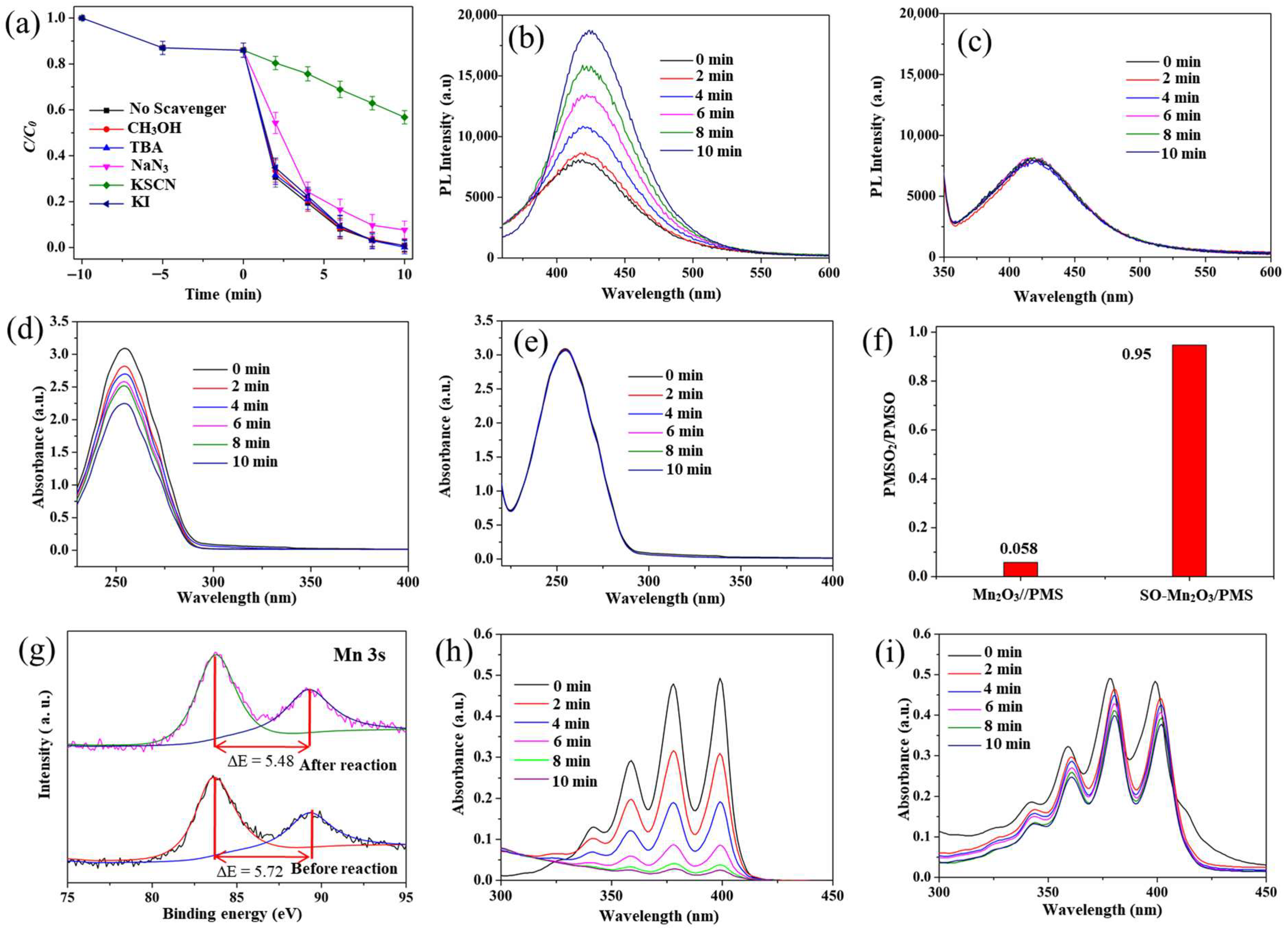

3.3. Catalytic Mechanism of the SO-Mn2O3/PMS System

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kovačič, A.; Modic, M.; Hojnik, N.; Štampar, M.; Gulin, M.R.; Nannou, C.; Koronaiou, L.A.; Heath, D.; Walsh, J.L.; Žegura, B.; et al. Heath, Degradation and toxicity of bisphenol A and S during cold atmospheric pressure plasma treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 454, 131478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Wang, Y.; Lv, K.; Zhu, C.; Guan, X.; Xie, B.; Zou, X.; Luo, X.; Zhou, Y. N-doped biochar-Fe/Mn as a superior peroxymonosulfate activator for enhanced bisphenol a degradation. Water Res. 2025, 278, 123399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, B.C.; Cates, E.L.; Kim, J.H. Challenges and prospects of advanced oxidation water treatment processes using catalytic nanomaterials. Nat. Nanotech. 2018, 13, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Cui, B.; Pei, F.; Li, Y.P.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, F.R.; Gao, Z.X.; Wang, S. Improving peroxymonosulfate activation mediated by oxygen vacancy-abundant BaTiO3/Co3O4 composites: The vital roles of BaTiO3. J. Solid State Chem. 2023, 323, 124049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; An, H.Z.; Feng, J.; Ren, Y.M.; Ma, J. Impact of crystal types of AgFeO2 nanoparticles on the peroxymonosulfate activation in the water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 4500–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Xie, X.; Hu, G.; Prabhakaran, V.; Saha, S.; Gonzalez-Lopez, L.; Phakatkar, A.H.; Hong, M.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R.; Ramani, V.; et al. Ta-TiOx nanoparticles as radical scavengers to improve the durability of Fe-N-C oxygen reduction catalysts. Nat. Energy 2022, 7, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Z.; Hou, S.; Wang, A.; Fang, J. Transformation of gemfibrozil by the interaction of chloride with sulfate radicals: Radical chemistry, transient intermediates and pathways. Water Res. 2022, 209, 117944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wu, J.; Ji, Y.; Kong, D. Transformation of bromide in thermo activated persulfate oxidation processes. Water Res. 2015, 78, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, E.T.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, J.; Park, H.D.; Lee, J. Identifying the nonradical mechanism in the peroxymonosulfate activation process: Singlet oxygenation versus mediated electron transfer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 7032–7042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Y.; Xu, X.; Gao, B.; Wang, S.; Duan, X. Single-atom catalysis in advanced oxidation processes for environmental remediation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 5281–5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, J.; Song, J.; Lang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Dai, J.; Wei, Y.; Long, M.; Shao, Z.; Zhou, B.; Alvarez, P.J.J.; et al. Single-atom MnN5 catalytic sites enable efficient peroxymonosulfate activation by forming highly reactive Mn(IV)-oxo species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 4266–4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wen, X.; Lang, J.; Wei, Y.; Miao, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, B.; Long, M.; Alvarez, P.J.J.; Zhang, L. CoN1O2 single-atom catalyst for efficient peroxymonosulfate activation and selective cobalt(IV)=O generation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202303267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.N.; Klu, P.K.; Wang, C.H.; Zhang, W.X.; Luo, R.; Zhang, M.; Qi, J.W.; Sun, X.Y.; Wang, L.J.; Li, J.S. Metal-organic framework-derived hollow Co3O4/carbon as efficient catalyst for peroxymonosulfate activation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 363, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Qiu, X.; Jin, P.; Dzakpasu, M.; Wang, X.C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Ding, D.; Wang, W.; et al. MOF-templated synthesis of CoFe2O4 nanocrystals and its coupling with peroxymonosulfate for degradation of bisphenol A. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 353, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Cui, B.; Pei, F.; Li, Y.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, F.; Gao, Z.; Wang, S. Spontaneous polarization-driven charge migration in BaTiO3/Co3O4/C for enhanced catalytic performance. CrystEngComm 2023, 25, 4219–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.-Y.; Sun, R.; Huang, Z.; Han, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, W.; Hong, X.; et al. Crystallinity engineering for overcoming the activity-stability tradeoff of spinel oxide in Fenton-like catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2220608120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, J.; Pang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Sun, S.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, C. Oxidation of bisphenol A by nonradical activation of peroxymonosulfate in the presence of amorphous manganese dioxide. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 352, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Jiang, N.; Pang, S.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, T. Effective activation of peroxymonosulfate with natural manganesecontaining minerals through a nonradical pathway and the application for the removal of bisphenols. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 126152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Dai, Y.; Singewald, K.; Liu, C.; Saxena, S.; Zhang, H. Effects of MnO2 of different structures on activation of peroxymonosulfate for bisphenol A degradation under acidic conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 370, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yuan, N.; Qian, J.; Pan, B. Mn2O3 as an electron shuttle between peroxymonosulfate and organic pollutants: The dominant role of surface reactive Mn(IV) species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 4498–4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Tang, R.; Xiong, S.; Li, L.; Zhou, Z.; Su, L.; Gong, D.; Deng, Y. High-valent metal-oxo species in catalytic oxidations for environmental remediation and energy conversion. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 2024, 510, 215840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, T.; Tong, Z.; Peng, X.; Xu, X.; Liu, Z.; Kang, C.; Fu, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Z.; et al. ZIF-derived FeCoCH/C3N5 promotes the generation of high-valent metal-oxo species via interface-local coupled electric field: Dual role of nitrogen. App. Catal. B 2025, 379, 125709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Li, F.; Zhang, M.; Li, Q.; Yang, J. Highly efficient peroxymonosulfate activation by molten salt-assisted synthesis of magnetic Mn-Fe3O4 supported mesoporous biochar composites for SDz degradation. ACS ES&T Water 2024, 4, 4591–4603. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, W.; Pan, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Pu, L.; Ding, J.; Gao, G.; Pan, B. Peroxydisulfate activation and singlet oxygen generation by oxygen vacancy for degradation of contaminants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 2110–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Hu, K.; Duan, X.; Ren, Y.; Sun, H.; Wang, S. Sustainable redox processes induced by peroxymonosulfate and metal doping on amorphous manganese dioxide for nonradical degradation of water contaminants. Appl. Catal. B 2021, 286, 119903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.Z.; Zhang, H. Direct electron-transfer-based peroxymonosulfate activation by iron-doped manganese oxide (δ-MnO2) and the development of galvanic oxidation processes (GOPs). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 12610–12620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, M.-K.; Huang, G.; Mei, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Hua, T.; Zheng, L.; Yu, H. Interface-promoted direct oxidation of p-Arsanilic acid and removal of total arsenic by the coupling of peroxymonosulfate and Mn-Fe-mixed oxide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 7063–7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Bao, J.; Fu, X.; Lu, C.; Kim, S.H. Mesoporous sulfur-modified iron oxide as an effective Fenton-like catalyst for degradation of bisphenol A. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 184, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Chen, F.; Fan, X.; Cai, W.; Zhang, J. S-doped α-Fe2O3 as a highly active heterogeneous Fenton-like catalyst towards the degradation of acid orange 7 and phenol. Appl. Catal. B 2010, 96, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhu, W.H.; Liu, J.W.; Lin, P.; Zhang, J.F.; Huang, T.L.; Liu, K.Q. Mesoporous sulfur-doped CoFe2O4 as a new Fenton catalyst for the highly efficient pollutants removal. Appl. Catal. B 2021, 295, 120273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Huang, T.; Qin, L. Highly active S-modified ZnFe2O4 heterogeneous catalyst and its photo-Fenton behavior under UV–visible irradiation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 7219–7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, J.; Yao, T.; Gu, L.; Du, C.; Gao, Y.; et al. Substrate strain tunes operando geometric distortion and oxygen reduction activity of CuN2C2 single-atom sites. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tani, Y.; Miyata, N.; Ohashi, M.; Ohnuki, T.; Seyama, H.; Iwahori, K.; Soma, M. Interaction of inorganic arsenic with biogenic manganese oxide produced by a Mn-oxidizing fungus, strain KR21-2. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 6618–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Sun, S.; Du, X.; Qu, J.; Li, L.; Yu, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X.; Zheng, R.; Cairney, J.M.; et al. Boosting oxygen reduction activity of manganese oxide through strain effect caused by ion insertion. Small 2022, 18, 2105201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Qu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhan, S. Dynamic active-site induced by host-guest interactions boost the Fenton like reaction for organic wastewater treatment. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Lin, Y.; Guo, S.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Q.; Luo, Y.; Ou, X.; Ma, J.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, J.; et al. Site engineering of covalent organic frameworks for regulating peroxymonosulfate activation to generate singlet oxygen with 100% selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202310934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Kang, G.; Deng, Y. Construction of mesoporous S-doped Co3O4 with abundant oxygen vacancies as an efficient activator of PMS for organic dye degradation. CrystEngComm 2023, 25, 2767–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Miao, K.K.; Zhao, W.X.; Jiang, H.B.; Liu, L.L.; Hu, D.W.; Cui, B.; Li, Y.P.; Sun, Y. Novel nanoparticle-assembled tetrakaidekahedron Bi25FeO40 as efficient photo-Fenton catalysts for Rhodamine B degradation. Adv. Powder Technol. 2022, 33, 103579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, S.; Zhang, P.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, F. MnO2 framework forinstantaneous mineralization of carcinogenic airborne formaldehyde at roomtemperature. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 1057–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wu, B.; Yu, L.; Crocker, M.; Shi, C. Investigation into the catalytic roles of various oxygen species over different crystal phases of MnO2 for C6H6 and HCHO oxidation. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 6176–6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Gao, J.; Li, W.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Li, S. Phosphate-induced electronic tuning of MnO2: Unlocking enhanced activation and complete oxidation of propane. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. Energy 2025, 372, 125291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fu, D.; Xu, X.; Sheng, Y.; Xu, J.; Han, Y.-F. Application of operando spectroscopy on catalytic reactions. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2016, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, W.; Ma, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Lei, J.; Yamashita, H.; Zhang, J. A-site defect regulates d-band center in perovskite-type catalysts enhancing photo-assisted peroxymonosulfate activation for levofloxacin removal via high-valent iron-oxo species. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. Energy 2025, 371, 125273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Bai, X.; Ji, Y.T.; Shen, T. Reduced graphene oxide-supported hollow Co3O4@N-doped porous carbon as peroxymonosulfate activator for sulfamethoxazole degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 132951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, N.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Zhai, L.; Wang, J.; Luo, X.; Hu, D.; Pei, F.; Wang, Y.; Miao, K. Morphology effect on piezocatalytic performance of zinc oxide: Overlooked role of surface hydroxyl groups. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 182, 115620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, J. Synergistic enhancement in catalytic performance of superparamagnetic Fe3O4@bacilus subtilis as recyclable fenton-like catalyst. Catalysts 2017, 7, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Li, L.; Lian, X.; Wu, M.; Zheng, F.; Song, L.; Hu, G.; Niu, H. A mild reduction of Co-doped MnO2 to create abundant oxygen vacancies and active sites for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 11120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Su, Z.; Xu, Z.; Yang, W.; Peng, Y.; Li, J. Comparative study of α-, β-, γ- and δ-MnO2 on toluene oxidation: Oxygen vacancies and reaction intermediates. Appl. Catal. B 2020, 260, 118150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instruments | Functions | Model | Testing Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray powder diffractometer (XRD) | Phase compositions | D8 Advance, Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany Cu Kα radiation, λ = 0.15406 nm | Tube voltage: 40 kV, tube current: 40 mA, 2θ = 10~80°, step size: 0.020°, scanning speed: 5°/min |

| Transmission electron microscope (TEM) | Microstructures | JEM-2100, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan | Operating voltage: 150 kV |

| Physical adsorption analyzer | Specific surface area | ASAP-2460, Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA | Carrier gas: N2 |

| X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) | Surface chemical composition | K-Alpha, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA | Calibrated via C 1s peak |

| Ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer | Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy | U-3900, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan | Test wavelength range: 200~800 nm |

| Fluorescence spectrophotometer | Fluorescence spectrum | RF-5301PC, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan | Excitation wavelength: 412 nm, slit width: 2 nm |

| High-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC) | The concentration of organic compounds | 1100, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA, Hypersil ODS C18 Columns, Column temperature: 40 °C | Detection wavelengths: 254 nm, mobile phase: acetonitrile and water (volume ratio 20:80), flow rate: 1 mL/min |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pei, F.; Dong, J.; Yan, X.; Xu, Y.; Yao, S. Efficient and Thorough Oxidation of Bisphenol A via Non-Radical Pathways Activated by SOx2−-Modified Mn2O3. Crystals 2025, 15, 922. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110922

Pei F, Dong J, Yan X, Xu Y, Yao S. Efficient and Thorough Oxidation of Bisphenol A via Non-Radical Pathways Activated by SOx2−-Modified Mn2O3. Crystals. 2025; 15(11):922. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110922

Chicago/Turabian StylePei, Fei, Jiajie Dong, Xin’e Yan, Youwen Xu, and Songyuan Yao. 2025. "Efficient and Thorough Oxidation of Bisphenol A via Non-Radical Pathways Activated by SOx2−-Modified Mn2O3" Crystals 15, no. 11: 922. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110922

APA StylePei, F., Dong, J., Yan, X., Xu, Y., & Yao, S. (2025). Efficient and Thorough Oxidation of Bisphenol A via Non-Radical Pathways Activated by SOx2−-Modified Mn2O3. Crystals, 15(11), 922. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110922