1. Introduction

In recent years, the escalating demand for mid- to large-scale energy storage in electric vehicles (EVs) and battery energy storage systems (BESS) necessitates Li-ion batteries (LIBs) that concurrently provide high energy and power densities [

1,

2]. Nevertheless, the conventional liquid electrolytes in LIBs depend on flammable organic solvents, leading to safety concerns such as leakage, fire hazards, and limited cycle life [

3,

4]. To enhance safety while preserving performance, extensive research has investigated inorganic solid electrolytes—including Na Super ionic Conductor (NASICON)-, perovskite-, garnet-, and sulfide-type materials—that demonstrate favorable electrochemical and thermal stability at ambient conditions [

5,

6,

7,

8].

Among the candidates for solid electrolytes, NASICON-type materials, characterized by the general formula AMe

2(PO

4)

3 (where A = Li

+, Na

+, K

+; Me = Ge

4+, Ti

4+, Zr

4+, etc.), crystallize within a rhombohedral framework. This structure is composed of corner-sharing PO

4 tetrahedra and MeO

6 octahedra, which facilitate robust structural integrity and interconnected Li-ion pathways, thereby enhancing rapid ion transport [

1,

2,

9,

10,

11]. LiTi

2(PO

4)

3 is a representative NASICON-type material with grain ionic conductivity of approximately 10

−4 S/cm. However, its total conductivity is often constrained (10

−8–10

−6 S/cm) owing to significant grain-boundary resistance [

1,

9,

12]. To address this limitation, aliovalent substitution in Li

1+XM

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3—where a trivalent transition metal (M

3+) substitutes for Ti

4+—has been utilized to augment Li content and improve conduction while maintaining charge balance [

13]. The Al

3+-substituted Li

1+XAl

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 electrolyte is the most extensively investigated variant, consistently demonstrating high ionic conductivities and reliable enhancement of Li

+ transport [

1,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

Various synthetic methodologies have been documented for the preparation of Li

1+XAl

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 and related Li

1+XM

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 compositions, including: (1) solid-state reaction [

13,

15,

16], (2) sol-gel synthesis [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], (3) other wet-chemical synthesis [

1,

16,

21,

22,

23,

24], and (4) melting and quenching [

16,

25,

26]. Despite the availability of numerous synthetic approaches within these categories, meticulous design of the synthesis procedure is imperative, as achieving a single-phase product while preventing the formation of impurity phases presents a significant challenge. Most Li

1+XM

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 compounds are prepared by solid-state methods, which necessitate high thermal treatment temperatures exceeding 1200 °C and extended holding durations. These methods have several drawbacks, including substantial energy consumption during production, potential contamination from impurities, irregular particle morphologies, broad particle size distribution, and loss of Li ions. Conversely, the sol-gel method offers numerous benefits for synthesizing multicomponent oxides and Li-based solid electrolytes, such as lower processing temperatures, precise compositional control, high purity, excellent homogeneity with narrow size distributions, morphological versatility, and potential for nanostructuring.

Despite extensive research on Al

3+ substitution, systematic investigations of Fe

3+ substitution in LiTi

2(PO

4)

3 are scarce. Fe

3+ and Al

3+ have the same number of valence electrons, but Fe possesses distinct ionic radii and electronic configurations, which can induce subtle modifications in the lattice parameters, distort the Ti–O framework, and alter the Li

+ diffusion pathways. These features suggest that Fe substitution may provide a unique means of tuning the ionic conductivity; however, only limited and fragmentary reports have explored this possibility [

27,

28,

29,

30]. Furthermore, very few studies have examined Fe-substituted Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 synthesized specifically using the sol-gel route, despite its advantages in achieving phase-pure and compositionally homogeneous products.

In this work, we aim to bridge this gap by synthesizing Li1+XFeXTi2-X(PO4)3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) using a sol-gel method and systematically evaluating the effects of Fe contents on the crystal structure, grain size, morphology, and ionic conductivity of the synthesized materials. Unlike prior studies that primarily focused on Al doping, this study emphasizes Fe doping as an underexplored but potentially promising strategy for enhancing Li+ transport in NASICON frameworks. Through complex impedance spectroscopy and structural characterization, we elucidated the correlation between Fe content, microstructural evolution, and ionic conductivity. These results provide new insights into the role of Fe3+ in tailoring NASICON-type electrolytes and highlight the sol-gel approach as a versatile synthesis method for designing next-generation solid electrolytes.

2. Experimental Procedures

In this study, we employed the sol-gel method to synthesize Li1+XFeXTi2-X(PO4)3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) solid electrolytes. Initially, an aqueous solution of the Ti source was prepared by diluting 6 mL of HNO3 (60%, Matsunoen Chemicals Ltd., Osaka, Japan) in 50 mL of deionized water to catalyze the reaction for dissolving 0.03 mol of TiO(C5H7O2)2 (TCI, Tokyo, Japan) powder. Acetylacetone (99%, Samchun Chemical, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea) was introduced as a chelating agent under stirring, maintaining a TiO(C5H7O2)2:acetylacetone molar ratio of 1:2. Concurrently, aqueous solutions of LiNO3 (99.0%, Kanto, Tokyo, Japan), Fe(NO3)3∙9H2O (99.0%, Fujifilm, Osaka, Japan), and NH4H2PO4 (99.0%, Junsei, Tokyo, Japan) were prepared in stoichiometric proportions and combined with the Ti solution under stirring to produce a homogeneous sol, which was aged at approximately 75 °C until gelation occurred. The resulting gel was cooled, oven-dried, and ground in an agate mortar to obtain a precursor powder.

The precursor was subjected to thermal treatment in an alumina crucible at 450 °C for 3 h, followed by regrinding to obtain the final powder. Pellets with a diameter of 13 mm were uniaxially pressed at a pressure of 350 MPa and subsequently sintered for 6 h at temperatures ranging from 800 to 1000 °C to achieve densification. The sintered densities of the resulting bodies at each temperature for Li1+XFeXTi2-X(PO4)3, synthesized with varying amounts of Fe, were determined using the apparent density.

Thermogravimetric and differential thermal analysis (TG-DTA, MAC Science 2000, Tokyo, Japan) was employed to assess weight loss and thermal decomposition changes of the obtained precursors under atmospheric conditions. Phase analysis was conducted using X-ray diffraction (XRD, X’Pert Pro, Panalytical, Cu-Kα, 40 KV, 30 mA, 4°/min, 2θ = 10–80°, Almelo, The Netherlands) to investigate the presence of crystalline and secondary phases of Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3, with Fe content determined by thermal treatment at different temperatures. The crystal structure of the materials was generally determined through Rietveld refinement of the XRD profile [

31,

32,

33]. This analysis was performed using the powder plug-in included in Rigaku’s SmartLab Studio II (ver. 4.6) software to evaluate crystal properties, such as lattice parameters, impurities, and crystallinity. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, MultiLab, ESCA 2000, Monochromator Al-Kα, VG Microtech, Uckfield, Sussex, UK) was utilized to verify elemental states and valences in the synthesized Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3. The fracture-surface morphology and densification of Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 as a function of sintering temperature were examined using a Field Emission-Scanning Electron Microscope (FE-SEM, Hitachi S-4800, Tokyo, Japan). Complex impedance was measured from room temperature to 300 °C with an LCR meter (HIOKI 3532-50, Hioki Electric Co., Ltd., Nagano, Japan) using a two-terminal AC method to determine total ionic conductivity and activation energy. Detailed synthesis and measurement methods for preparing Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 are available in the literature [

34].

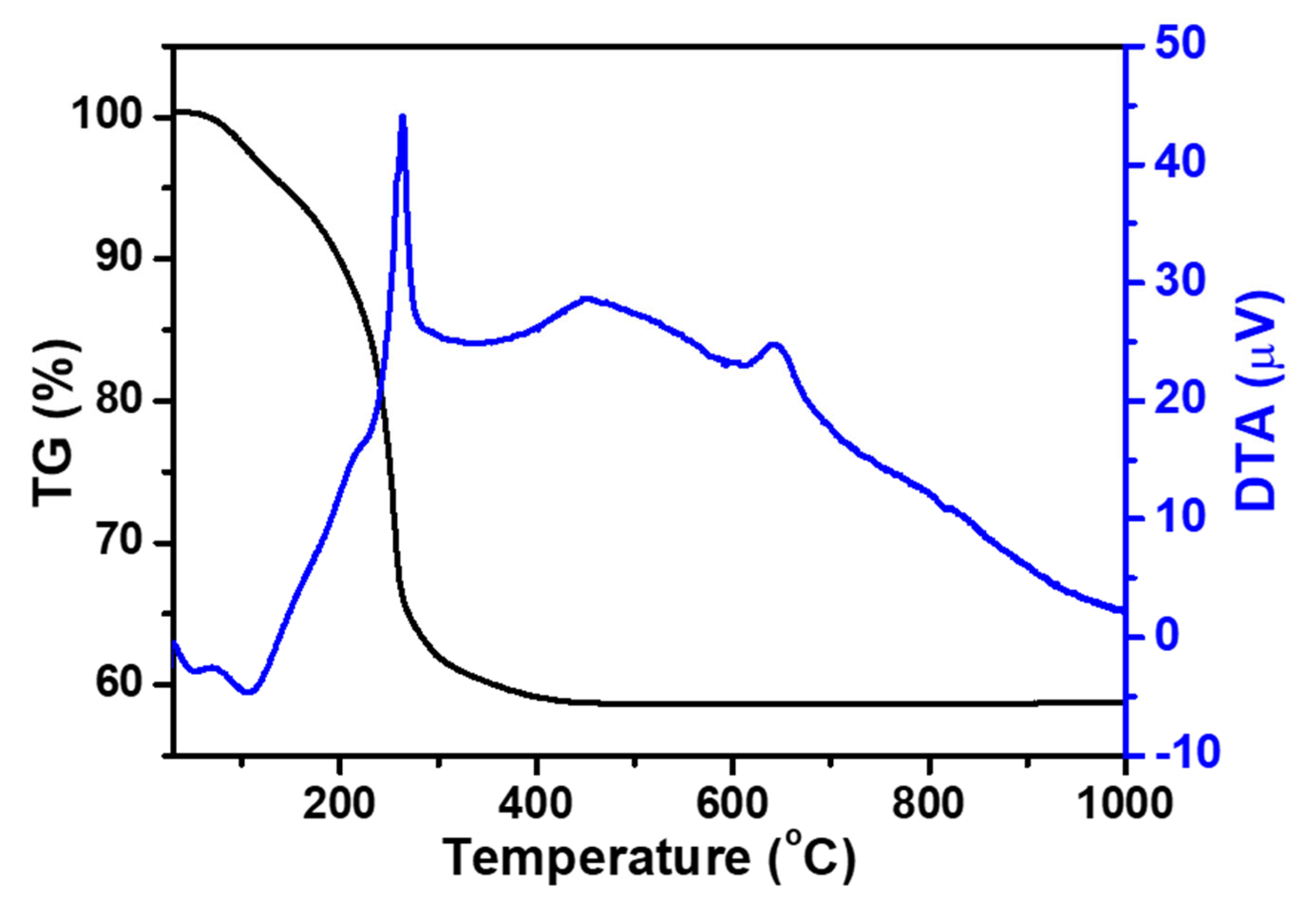

3. Results and Discussions

Thermal behavior analysis was conducted to identify a suitable pre-calcination temperature for the dry precursors synthesized via the sol-gel method with varying Fe contents. As reported in the authors’ previous study, all precursors with varying Fe contents exhibited similar thermal behavior, with approximately 40% weight loss attributed to organic matter decomposition and solvent evaporation occurring up to approximately 430 °C as the temperature increased [

34]. Although no significant weight change was observed, a small exothermic peak at approximately 630 °C indicated that the crystallization temperature for Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) was above 630 °C, as the synthesized amorphous precursor transitioned into a crystalline phase through crystallization. Therefore, the optimal pre-calcination temperature for each precursor was determined to be 450 °C. This decision was made to remove the organic components completely while preventing unwanted particle growth, phase segregation, or lithium loss, which could occur at higher temperatures. The choice of 450 °C facilitates morphological control and maintains the powder features synthesized via the sol-gel method, which is beneficial for final sintering or electrochemical applications. The representative results of the thermal behavior analysis of the sol-gel precursors Li

1.3Fe

0.3Ti

1.7(PO

4)

3 are shown in

Figure 1.

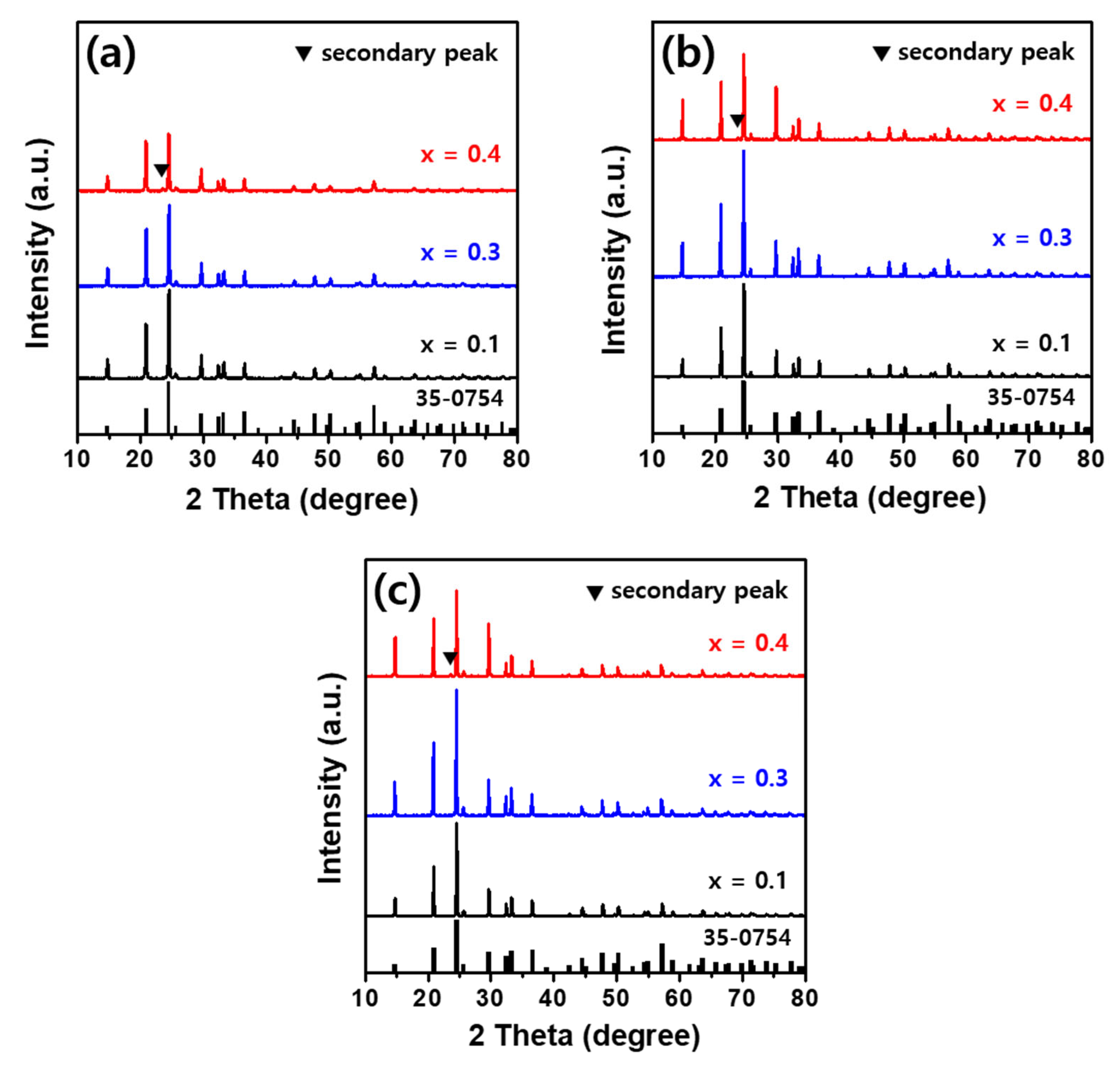

Figure 2 shows the crystalline phase results obtained through XRD measurements of Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) solid electrolyte powders, which were prepared by calcining precursors with varying Fe contents synthesized using the sol-gel method and thermal-treating them at sintering temperatures ranging from 800 to 1000 °C at 100 °C intervals for 6 h. The XRD patterns of Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 powders with varying Fe contents at different sintering temperatures revealed a rhombohedral crystal structure with a

group of the NASICON system corresponding to LiTi

2(PO

4)

3 (JCPDS 35-0754). As the sintering temperature and Fe content increased, the diffraction pattern peaks became sharper, and their intensities increased. This indicates that a high-quality crystalline phase of the Li-based solid electrolyte was obtained. Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 with an Fe content up to x = 0.3 exhibited a single-phase diffraction pattern with no secondary phase across all thermal-treatment temperatures. However, at all thermal treatment temperatures, Li

1.4Fe

0.4Ti

1.6(PO

4)

3 with an Fe content of x = 0.4 exhibited an additional diffraction peak of a very weak secondary phase at 2θ = 23.6°. This was attributed to the partial substitution of Fe

3+ (ionic radius = 0.645 Å), which has a slightly larger ionic radius than Ti

4+ (ionic radius = 0.605 Å). When the Fe content exceeds x = 0.4, this indicates the limit of the solid solubility, which likely leads to the formation of an FePO

4-like secondary phase (JCPDS 29-0715) [

27,

35,

36]. Additionally, secondary phases, such as those attributed to FePO

4, can result from Li volatilization during high-temperature sintering above 1000 °C. Partial substitution was structurally stable up to an Fe content of x = 0.3. When the Fe content is x = 0.4, the sample is thought to crystallize in a different crystal structure with lower symmetry, which was ascribed to monoclinic with a P2

1/n space group, as previously reported [

29].

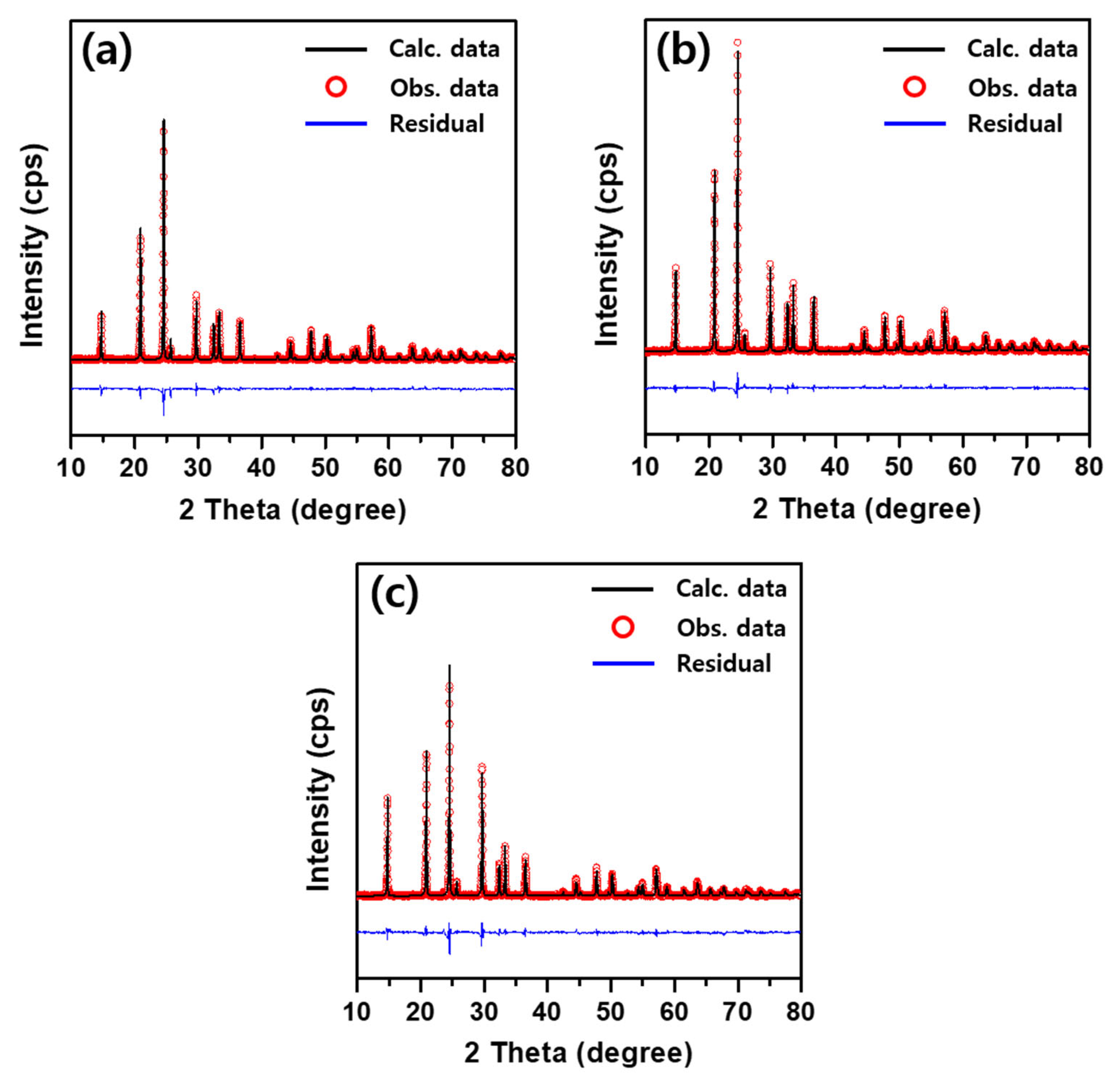

Rietveld refinement was also conducted to generate more detailed information related to the structure of Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3. The initial model crystal structure of Li

1.3Fe

0.3Ti

1.7(PO

4)

3 for the refinement method was obtained from a paper published by M. Pérez-Estébanez et al. [

29]. Using the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD 04-023-1708) were identified crystalline phases. Data from the measured powder XRD patterns were used to evaluate the cell lattice parameters of the samples. The process of reducing the difference between the measured diffraction pattern and calculated model was repeated using the least-squares method. In the Rietveld refinements, a pseudo-Voigt function, which is created by combining the Gaussian and Lorentz functions, was chosen to describe the line shape of the diffraction peaks.

Figure 3 shows the observed, calculated, and residual XRD patterns with Rietveld refinement results of the hand-milled Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) powders from a pellet sintered at 900 °C for 6 h. All Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 materials represented the pristine NASICON phase. Therefore, Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 was obtained as a highly pure, well-crystall. FePO

4 was commonly observed in the XRD patterns, even in trace amounts. It is well known that FePO

4 acts as a resistive component and is detrimental to ionic conductivity. The lattice parameters estimated by Rietveld refinement for Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4), as presented in

Table 1, are similar to those reported previously crystallographic data [

13,

29,

30]. The unit cell parameters increased as the Fe content in Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 increased, indicating unit cell expansion. This increase can be attributed to the larger ionic radius of Fe

3+ compared with that of Ti

4+. The final atomic coordinates and multiplicities of Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) are listed in

Table 2 [

37].

Table 3 summarizes the interatomic distances and R-factors obtained from the Rietveld refinements for Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) powders sintered at 900 °C for 6 h. The R-factors obtained from the refinement analysis consisted of the weighted profile R-factor (R

WP) and a reduced chi-square (

χ2), which indicated the degree of Rietveld agreement. The R

WP obtained in this work was lower than that reported in previous studies, indicating a better-fitting refinement result [

27,

28,

29,

30]. The small R

WP values of less than 1% finally obtained suggest the validity of the refinement hypothesis of this study, especially with regard to the position of Li ions within the structure. In the Rietveld refinement of Li

1.4Fe

0.4Ti

1.6(PO

4)

3, two distinct interatomic distances for P–O1 and P–O2 were observed. This bifurcation arises from the increased distortion of the PO

4 tetrahedra owing to the local charge and size mismatch effects as Fe

3+ replaces Ti

4+. The mixed valency and charge compensation mechanisms affect the electron density distribution and induce asymmetry in the P–O bonding environment. The increase in Fe content at x = 0.4 appears to disrupt the uniformity of the P–O bond lengths, leading to the static or dynamic distortion of the tetrahedral units, which is captured as two separate distances in Rietveld refinement. Simultaneously, the Li–O bond distance decreased. This contraction can be attributed to enhanced Li

+ localization near the negatively charged oxygen framework caused by Fe

3+ substitution. The increased Fe

3+ content results in more available interstitial Li-ions, which, in turn, intensifies the coulombic interactions and draws Li

+ closer to the oxygen atoms, promoting more compact Li–O polyhedra. Furthermore, the partial Fe

3+ occupancy at the Ti

4+ sites causes lattice shrinkage owing to stronger Fe–O bonding than Ti–O, contributing to a more compact local environment around the Li-ions.

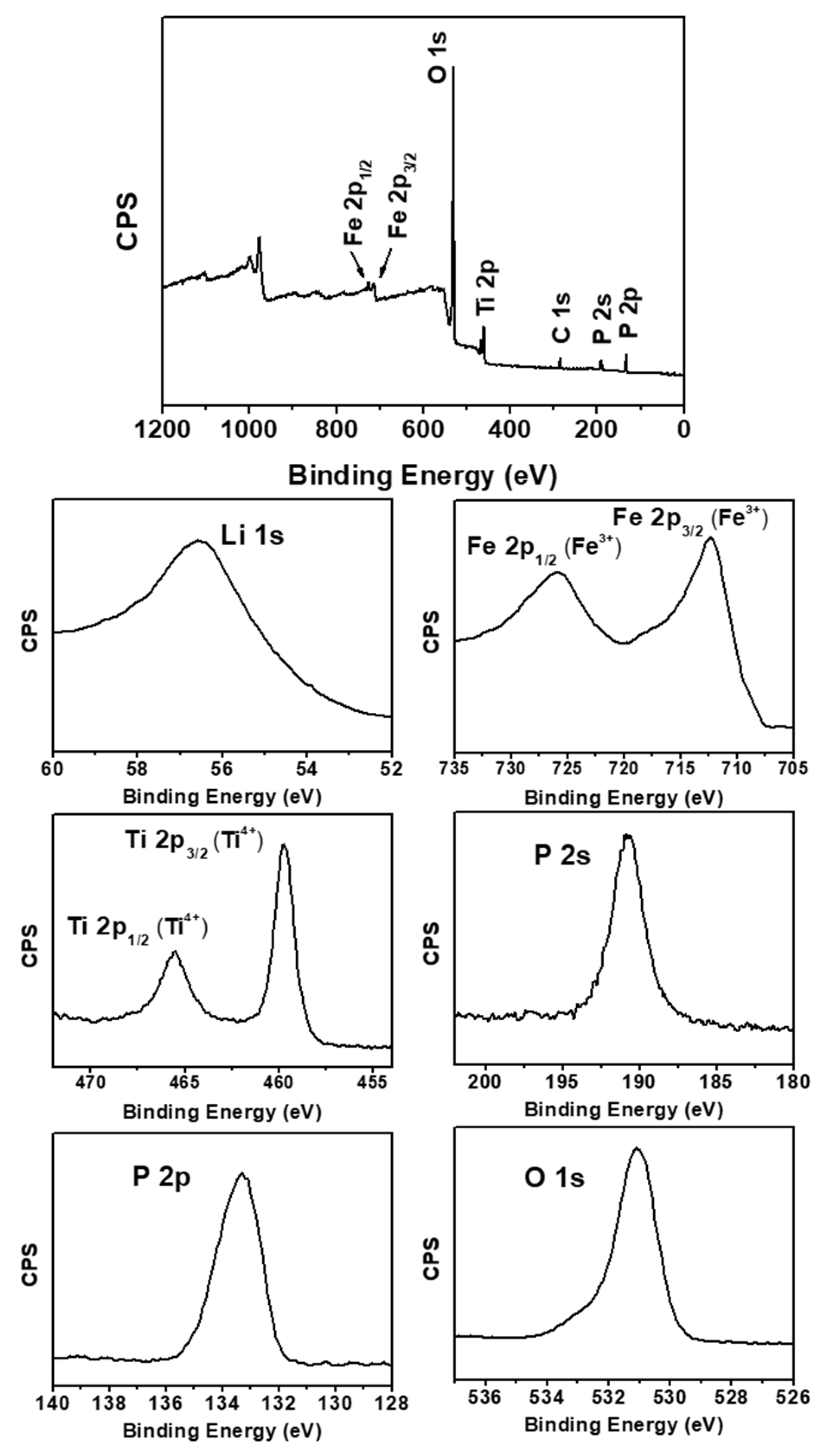

To evaluate the presence of constituent elements, as well as the binding energy of internal ion occupancy positions and oxidation state in the synthesized Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3, XPS analysis was performed on Li

1.3Fe

0.3Ti

1.7(PO

4)

3 sintered at 900 °C for 6 h, as illustrated in

Figure 4. The characteristic binding energy spectra corresponding to Li 1s, P 2s, P 2p, Ti 2p, O 1s, and Fe 2p, as indicated by the full range of binding energies, confirmed the qualitative presence of each element in the synthesized solid electrolyte. The XPS spectrum for Li 1s exhibited very low intensity, with the central peak having a binding energy of approximately 56.8 eV. The spectra for Ti and Fe displayed distinct binding energies separated by a spin-orbit doublet. For Ti, the binding energies were identified as 459.7 eV and 465.6 eV at Ti 2p

3/2 and Ti 2p

1/2, respectively, indicating an oxidation state characteristic of Ti

4+. Fe also demonstrated characteristic binding energies of Fe

3+ equivalent to 712.5 eV and 726 eV at Fe 2p

3/2 and Fe 2p

1/2, respectively. This suggests that the partial substitution of Fe at the Ti site facilitated the synthesis of a solid electrolyte comprising Ti

4+ and Fe

3+ without altering their valences. Additionally, a binding energy of approximately 133.5 eV was observed, corresponding to P

5+ in the form of (PO

4)

3. The binding energy of 284.6 eV for C 1s of the C−C is likely the result of contamination during exposure to air.

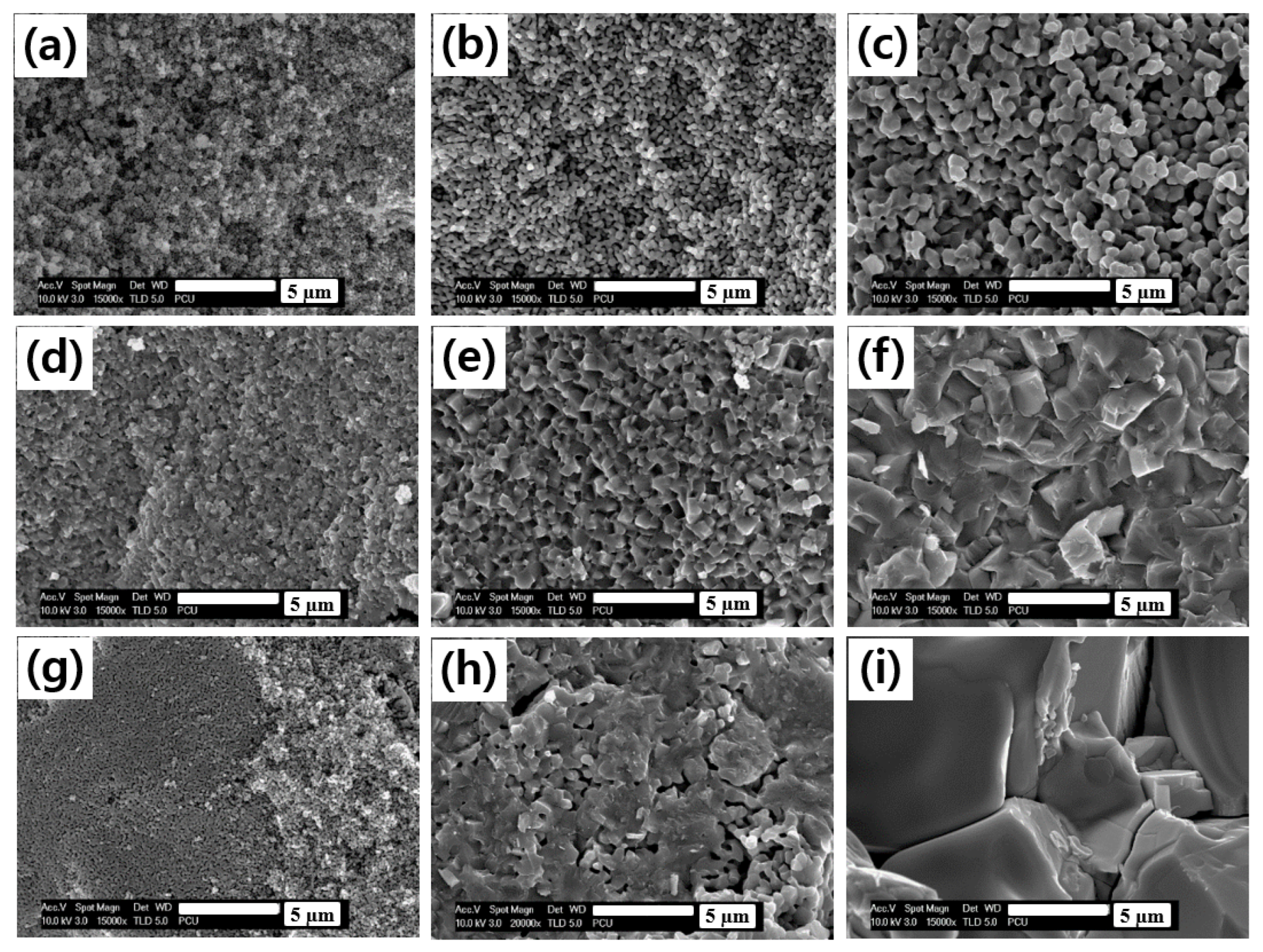

The production of dense sintered bodies is essential for obtaining solid electrolytes with excellent ion conductivity properties.

Figure 5 presents the FE-SEM fracture-surface micrographs of the sintered bodies of the Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) solid electrolyte, which were obtained by sintering each precursor prepared using the sol-gel method at each sintering temperature for 6 h.

Figure 5a–c displays the FE-SEM images of the fracture-surfaces of Li

1.1Fe

0.1Ti

1.9(PO

4)

3 at each sintering temperature. Overall, the small sub-µm-sized grains appeared loosely packed under all sintering temperature conditions. Although some neck formation owing to grain growth was observed as the sintering temperature increased, densification was minimal because many pores remained.

Figure 5d–f shows images of the fracture-surfaces of Li

1.3Fe

0.3Ti

1.7(PO

4)

3 at different sintering temperatures. With an increase in the Fe content, the grains exhibited both growth and densification, although small pores persisted between the grown grains. The grain morphology also changed from quasi-spherical to quasi-cube-like shapes. At 900 °C and 1000 °C, uniform grain sizes of approximately 1 μm and 2–3 μm, respectively, were observed in the fracture-surfaces of Li

1.3Fe

0.3Ti

1.7(PO

4)

3, indicating significant densification.

Figure 5g–i shows fracture-surfaces images of Li

1.4Fe

0.4Ti

1.6(PO

4)

3 at different sintering temperatures. At the lower sintering temperature of 800 °C, results similar to those of the solid electrolytes with varying Fe contents were observed, with increased densification correlating with rising sintering temperatures and resulting grain growth. Notably, the fracture-surface of the solid electrolyte sintered at 1000 °C exhibited rapidly coarsening grains ranging from 3 to 10 μm. However, a closer examination of these surfaces revealed intragranular fracture patterns rather than intergranular fractures, suggesting that rapid grain coarsening may negatively impact the densification process, resulting in poor sintering properties [

38]. The apparent density of the Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 solid electrolytes with low Fe content slightly increased with higher sintering temperatures; however, this still resulted in lower sintered densities than other compositions. In contrast, at Fe contents of x = 0.3 and 0.4, a denser morphology was observed along with grain growth at elevated sintering temperatures, indicating an increased sintered density. However, the solid electrolyte sintered at 1000 °C with an Fe content of x = 0.4 exhibited cracks due to rapid grain coarsening and poor sintering properties caused by uneven contact between grains, which may negatively impact Li

+ migration. The detailed results of the apparent sintered densities for each Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 are presented in

Table 4.

Figure 4.

XPS spectra of Li1.3Fe0.3Ti1.7(PO4)3 sintered at 900 °C for 6 h.

Figure 4.

XPS spectra of Li1.3Fe0.3Ti1.7(PO4)3 sintered at 900 °C for 6 h.

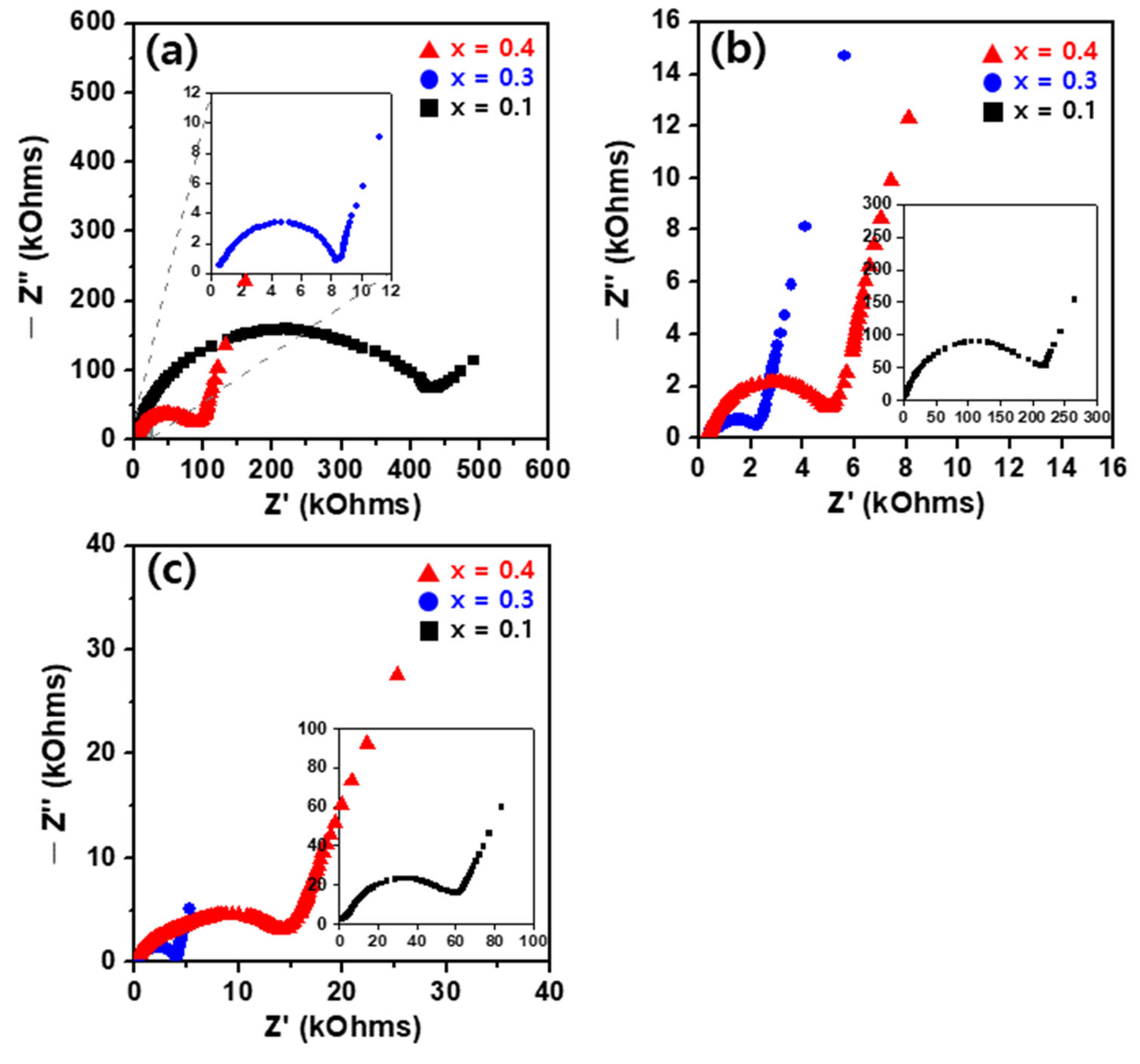

Figure 6 presents the Cole-Cole plot results of the AC complex impedance measured at room temperature for the Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) solid electrolytes, which were prepared at different sintering temperatures. The complex impedance generally exhibited semicircular patterns in the high-frequency range, indicative of the total impedance of the grains and grain boundaries, while straight lines in the low-frequency range suggested the blocking of Li-ions by the electrodes.

Figure 6a illustrates the impedance results for the Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) sintered at 800 °C. Li

1.1Fe

0.1Ti

1.9(PO

4)

3, characterized by a relatively low Fe content, demonstrated significantly larger impedance values owing to its less dense sintered structure. As the Fe content increased to x = 0.3, the impedance values decrease, attributed to the denser sintering nature. However, for Li

1.4Fe

0.4Ti

1.6(PO

4)

3 with an increased Fe content, the impedance values increased again, attributed to the high resistance component associated with the presence of a secondary phase, as indicated by the XRD results. As depicted in the Cole-Cole plots in

Figure 6b,c, the impedance measurements for the Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) sintered at 900 °C and 1000 °C also exhibit similar results. The densification and increased sintering density owing to grain growth resulted in relatively lower impedance values. However, as shown in

Figure 6c, the impedance of Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 sintered at 1000 °C shows a slight increase compared to that sintered at 900 °C. This may be attributed to the elevated impedance component owing to grain boundaries and intragranular cracks formed by the rapid coarsening of grains at higher sintering temperatures [

21,

39]. Additionally, despite similar sintered densities, the impedance characteristics of the solid electrolyte increased owing to factors such as Li volatilization and the formation of a secondary phase, leading to Li deficiency and decreased Li mobility, ultimately affecting the impedance.

Figure 5.

FE-SEM fracture-surface micrographs of the sintered bodies Li1+XFeXTi2-X(PO4)3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) after 6 h sintering at (a,d,g) 800 °C, (b,e,h) 900 °C, and (c,f,i) 1000 °C.

Figure 5.

FE-SEM fracture-surface micrographs of the sintered bodies Li1+XFeXTi2-X(PO4)3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) after 6 h sintering at (a,d,g) 800 °C, (b,e,h) 900 °C, and (c,f,i) 1000 °C.

Table 4.

Apparent density, room temperature total ion conductivity (σtot), and activation energy (Ea) for Li1+XFeXTi2-X(PO4)3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) sintered bodies for 6 h at 800~1000 °C.

Table 4.

Apparent density, room temperature total ion conductivity (σtot), and activation energy (Ea) for Li1+XFeXTi2-X(PO4)3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) sintered bodies for 6 h at 800~1000 °C.

Sintering Temperature

(°C) | Fe

Content

(mol) | Apparent

Density

(%) | σtot,303K

(S/cm) | Ea

(eV) |

|---|

| 800 | 0.1 | 48 | 1.11 × 10−6 | 0.46 |

| 0.3 | 69 | 4.62 × 10−5 | 0.41 |

| 0.4 | 60 | 9.13 × 10−6 | 0.46 |

| 900 | 0.1 | 55 | 1.24 × 10−5 | 0.46 |

| 0.3 | 90 | 1.51 × 10−4 | 0.37 |

| 0.4 | 88 | 7.69 × 10−5 | 0.38 |

| 1000 | 0.1 | 74 | 1.14 × 10−5 | 0.44 |

| 0.3 | 89 | 9.23 × 10−5 | 0.38 |

| 0.4 | 87 | 2.86 × 10−5 | 0.40 |

Figure 6.

Cole-Cole plots of room temperature complex impedance for Li1+XFeXTi2-X(PO4)3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) sintered for 6 h at (a) 800 °C, (b) 900 °C, and (c) 1000 °C.

Figure 6.

Cole-Cole plots of room temperature complex impedance for Li1+XFeXTi2-X(PO4)3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) sintered for 6 h at (a) 800 °C, (b) 900 °C, and (c) 1000 °C.

The total ionic conductivity, encompassing both grains and grain boundaries, was ascertained from impedance measurements conducted at room temperature,

where σ

tot represents the total ionic conductivity,

l denotes the thickness of the solid electrolyte,

Rtot is the measured impedance, and

S signifies the electrode area. The total ionic conductivity as a function of sintering temperature and Fe content is detailed in

Table 4. The maximum ionic conductivity of 1.51 × 10

−4 S/cm was achieved with Li

1.3Fe

0.3Ti

1.7(PO

4)

3 sintered at 900 °C. Although ionic conductivity generally increases with elevated Fe content and sintering temperature, the ionic conductivity of Li

1.4Fe

0.4Ti

1.6(PO

4)

3 sintered at 1000 °C decreased to 2.86 × 10

−5 S/cm. This reduction is attributed to the high resistance component of numerous grain boundaries and cracks resulting from rapid grain growth and uneven intergranular contact. As indicated in

Table 4, the apparent sintered densities of the Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 ranged from 48% to 90%, contingent on the Fe content and sintering temperature. Although these values fall below the 95% benchmark often cited for solid electrolytes, sintering aids were deliberately not employed, as secondary glassy phases can degrade ionic conductivity. Furthermore, advanced densification techniques were excluded to maintain a straightforward and reproducible fabrication process. Consequently, this study systematically evaluates the effects of Fe substitution on the structure, microstructure, and ionic conductivity under comparable processing conditions. As demonstrated by the Rietveld refinement results in

Table 3, the observed decrease in the Li–O interatomic distance with increasing Fe content (x = 0.4) in Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 direct impact on Li-ion conductivity. In NASICON-type structures, a three-dimensional framework facilitates interconnected pathways for Li

+ migration through interstitial sites and channels. While a reduction in the Li–O interatomic distance generally suggests stronger interactions and potential stabilization of Li

+ conduction paths, in the case of Li

1.4Fe

0.4Ti

1.6(PO

4)

3, it is associated with a decrease in ionic conductivity. This is likely due to the excessive strengthening of the Li–O bonds, which impedes the mobility of Li ions within the NASICON framework. A moderate decrease in the Li–O distance can lower the energy barrier for hopping by stabilizing the intermediate states along the conduction pathway, thereby enhancing ion mobility. Furthermore, Fe

3+ substitution increases the Li content, thereby increasing the Li

+ carrier concentration. Combined with structural shrinkage and tighter Li–O interactions, these changes can optimize the bottleneck size of the conduction channels, improving the conductivity of Li

+ across the framework. However, excess Li

+ may occupy interstitial or previously vacant sites, leading to congestion within the conduction pathways and obstruction of the percolation channels. Therefore, although a moderate shortening of the Li–O distance may enhance conductivity, as evidenced by our results, excessive contraction is believed to exacerbate the trapping of Li

+, resulting in decreased ionic conductivity. Although Al

3+ doping yields slightly higher conductivity owing to its smaller ionic radius and stable lattice incorporation, Fe

3+ substitution presents an attractive alternative, offering unique local distortion effects and cost benefits. Unlike Al

3+, Fe

3+ also introduces a more pronounced bonding asymmetry, which may further modulate the Li

+ migration pathways.

Figure 7 presents the Arrhenius plots illustrating the relationship between total ionic conductivity and measurement temperature for Li

1+XFe

XTi

2-X(PO

4)

3 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.4) solid electrolytes synthesized at different sintering temperatures. The activation energy was derived from the slope of the linear fit. The Arrhenius equation is as follows,

where

is the exponential factor,

Ea represents the activation energy,

k denotes the Boltzmann constant, and

T is the absolute temperature. As shown in

Table 4, lower activation energies are generally associated with increased Li-ion conductivity. The ion conductivity exhibited an upward trend with rising measurement temperature, and overall, Li

1.1Fe

0.1Ti

1.9(PO

4)

3 demonstrated a higher activation energy irrespective of the sintering temperature. Conversely, relatively low activation energies were observed at Fe contents of x = 0.3 and 0.4. The improved ionic conductivity is attributed to the facile movement of Li ions within the lattice, facilitated by the densification of the relatively enlarged grains [

22]. This suggests that a lower activation energy correlates with enhanced Li-ion conductivity. A notably low activation energy of 0.37 eV was recorded for Li

1.3Fe

0.3Ti

1.7(PO

4)

3 sintered at 900 °C, which exhibited the highest ionic conductivity.